Low-income and Immigration: An Overview and Future Directions for Research

By Eden Crossman

March 2013

The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Citizenship and Immigration Canada or the Government of Canada.

Ci4-126/2014E-PDF

978-1-100-24810-3

Reference number: R21-2012

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Issue

- Measures of low-income

- Factors influencing low-income among immigrants

- Summary and future directions for research

- References

Executive summary

Recent trends indicate that the gap between the low-income rates for immigrants and those born in Canada has increased substantially since 1980. Rising low-income rates among more recent immigrants relative to both the Canadian-born and immigrants who have been in Canada longer are cause for concern because low-income potentially impacts the ability of immigrant individuals and families to participate economically, socially, culturally, and with dignity in their communities. While the latest research results point to improvements in immigrant economic outcomes relative to the Canadian-born, there remain immigrants who have not seen an increase in relative economic performance, and who live in chronic low-income. This is potentially one of the most serious social and labour market challenges that Canada is facing. The objective of this report is to provide an overview of the low-income situation of immigrants in Canada with the goal of highlighting aspects of this issue in need of additional research. This report is organized into four parts. Part one considers the policy importance of the issue of low-income and immigration. Part two provides a description of low-income measures and touches upon differences to reflect on when using these indicators to evaluate immigrant economic outcomes. This is followed in part three by an examination, based on a review of the research literature, of the factors that contribute to the low-income situations of immigrants in Canada. Finally, part four provides a brief summary, along with research and data considerations for the investigation of low-income and immigration going forward.

There are a number of low-income lines used to inform policy development in the area of immigrant economic integration. Low-income measures such as Statistics Canada’s Low-Income Cut Off (LICO) and Low-Income Measure (LIM), and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada’s Market Basket Measure (MBM) can be used to identify the low-income population, while measures of chronic low-income and low-income intensity are often used in studying trends in the depth and duration of low-income spells among immigrants. It is meaningful to understand if a situation of low-income is transitory or persistent, as policy solutions may be very different. The existing low-income measures are designed to identify low-income individuals from different angles. Given the many dimensions of low-income, it may not be possible to find one measure that provides a complete picture; rather, it is argued in several studies reviewed that it is most useful to develop or adopt multiple measures of low-income. Although the use of LICO has been prevalent to date in studies looking at immigrants and low-income, the growing obsoleteness of this measure (with increasing number of years from a 1992 base year), along with recent data developments imply a likelihood of a move towards more prevalent use of LIM-based measures (which are derived from the distribution of incomes in the underlying population in each year) going forward.

Low-income is widely accepted as an indicator of access to economic resources among members of society and is therefore often used as a key indicator of immigrant integration and well-being. This study reviews the factors contributing to the earnings outcomes among recent immigrants (low-income among immigrants has closely tracked earnings trends, since earnings are the most significant component of family income, which is used to calculate low-income rates), focusing on the relationship between the characteristics of immigrants, or the socio-economic attributes that immigrants bring with them (including immigration category, year of landing and years in Canada, age, education, gender, source country, family type, province of residence, occupation, etc.), and the opportunities and barriers presented by the host society, be they economic, social, or institutional. Only through comparisons can factors be brought to light that explain why some groups end up more or less affected by low-income. Overall, the causes of low-income amongst immigrants are multifarious. For working age immigrants, for example, a shift in their characteristics and the cyclical nature of the economy may lead to additional barriers to the labour market, while for senior immigrants, their family size, family type, and motivations for immigration may generate different income levels.

In reviewing the recent literature on the low-income situation of immigrants in Canada and in examining different measures of low-income, this report concludes with the identification of potential new research possibilities. Specifically, a gap in research is revealed on the low-income situation of immigrants post-2006, the time of the last Canadian Census of population. There are two key reasons why the post-2006 time period is of particular policy importance with respect to understanding the low-income situation of immigrants in Canada today. First, many immigration policy changes have taken place since 2002, starting with the implementation of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), and it is important to understand how these changes have influenced the income situation of recent immigrants. Second, labour market conditions throughout Canada (and many areas of the world) since 2006 have changed considerably (for example, the Canadian economy underwent a recent recession, from October 2008 to October 2009). In light of the recent changes in immigration policies and both domestic and global economic downturn and recovery, research is needed that looks at the low-income situation of recent immigrants in this new landscape.

To this end, data are needed that will contribute to the current understanding of the low-income situation of immigrants in all admission categories, including economic immigrants, and particularly among family class immigrants and refugees. The past has seen a fairly steady use of several Statistics Canada’s surveys to examine the low-income situation of immigrants and other Canadians, mainly the Census, the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID), and to a lesser extent, the Longitudinal Administrative Database (LAD)-Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) (LAD-IMDB Database). Recent developments with regards to these traditionally used surveys have important implications (reviewed in this report) for the continued study of immigrants in low-income going forward. A recently Redesigned IMDB that now includes family formation (among other additions) is likely to become the key information source to examine the labour market transitions of immigrants, including into and out of low-income situations. In light of policy focused on improving the economic outcomes of immigrants, research and data development in the areas of low-income – incidence and causes – is a priority.

Introduction

Research findings suggest a worrisome problem of low-income among recent immigrants to Canada (see, for example, Picot, Lu, and Hou, 2009; Fleury, 2007; Picot, Hou, and Coulombe, 2007; Picot and Sweetman, 2005; Palameta, 2004; and Picot and Hou, 2003). Recent immigrants consistently show up as one of the non-elderly groups most likely to experience low-income.Footnote 1 Incidence of low-income is much higher among recent immigrants than among the Canadian-born and recent trends show increasing low-income rates among recent immigrants (though low-income rates for immigrants who have been in Canada for longer periods of time are lower).Footnote 2 Moreover, while low-income rates among recent immigrants have trended upwards, there has been declining low-income rates among the Canadian-born.Footnote 3 As a result, rather than converging, the gap between low-income rates for immigrants and those born in Canada has increased considerably.

According to Canadian Census data, the gap between the low-income rates for immigrants and those born in Canada has increased substantially over the past three decades. In 1980, recent immigrants had a low-income rate of 25% -- 1.4 times that of Canadian-born population; by 2000 they were 2.5 times higher, at 35.8%.Footnote 4 Results from the 2006 Census show that immigrants who arrived in Canada in 2004 were more than three times as likely as most Canadians to have low-incomes. Fully 34.1% of these newcomers fell into the low-income category of the Census, as compared to a rate of 9.7% for all Canadians.Footnote 5 Picot and Hou (2003) argue that the rise cannot be attributed to poorer economic conditions in 2000, compared to earlier business cycle peaks; the unemployment rate in 2000 was 6.8% and was lower than that observed in 1990 (8.1%) or 1980 (7.5%). It thus appears there has been a structural rise in the low-income rate of recent immigrants.

While the latest research results point to improvements in immigrant economic outcomes relative to the Canadian-born (see, for example, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Evaluation Division, 2010; Kustec and Xue, 2009), there remain immigrants who have not seen an increase in relative economic performance, and who live in chronic low-income.Footnote 6 This is potentially one of the most serious social and labour market challenges that Canada is facing. The objective of this report is to provide an overview of the low-income situation of immigrants in Canada with the goal of highlighting aspects of this issue in need of additional research. This report is organized into four parts. Part one considers the policy importance of the issue of low-income and immigration. Part two provides a description of low-income measures and touches upon differences to reflect on when using these indicators to evaluate immigrant economic outcomes. This is followed in part three by an examination, based on a review of the research literature, of the factors that contribute to the low-income situations of immigrants in Canada. Finally, part four provides a brief summary, along with research and data considerations for the investigation of low-income and immigration going forward.

Issue

Low-income potentially impacts on immigrant individuals and families’ ability to participate economically, socially, culturally, and with dignity in their communities. Low-income is widely accepted as a measure of access to economic resources among members of society, and thus is often used as a key indicator of immigrant integration and well-being. For instance, if groups of immigrants are over represented among those with low-income, it can imply serious consequences for their process of integration. Low-income is commonly used in the research as a proxy indicator for level of poverty (see information box Low-income, poverty, and well-being for details), and many social scientists acknowledge that living in poverty restricts not only the physical security of people’s lives, it also has a detrimental impact on their psychological and social well-being and on their ability to participate in life’s activities.Footnote 7 Camarota (1999) argues that widespread low-income makes it much more difficult to engage in the kind of give-and-take that is an integral part of the democratic process.Footnote 8 He argues that social science research indicates that the distribution of income has an impact on how people view one another, and with more low-income comes less trust and greater suspicion of others. As a result, he continues, great disparities in income cannot help but create greater social distance between members of a community and this in turn is likely to have a negative impact on political and social harmony.

From a fiscal point of view, there are also reasons to care about the low-income situation of immigrants. According to Camarota (1999), the main reason for concern about immigration's impact on the incidence of low-income is the effect on the poor already in the country, both native-born and immigrant. By this argument, if immigration increases the number of people who are in need of assistance, then this can only raise the cost of assistance efforts. Alternatively, the argument continues, if overall government expenditures on programs for those with low-income are kept constant, each recipient's benefit must be reduced so that all can be covered. Therefore, it is reasoned that if one is concerned about the poor already present, increasing the number of people in or near low-income through immigration is counter-productive in light of goals aimed at reducing low-income in society. The same study by Camarota next points out that because of their very low-incomes and the progressive nature of most taxes, individuals in low-income pay very little in taxes. Moreover, this argument continues, they also tend to use a great deal of services provided by the government, and as a result are generally a net drain on public coffers. If immigration increases the size of the low-income population, then this is very likely to have a negative effect on the tax base, particularly where most immigrants settle.

The arguments made by Camarota are concluded with the point that in any discussion of low-income resulting from immigration, it is important to remember that immigration is a discretionary policy of the federal government. The federal government determines the size, growth, and characteristics of the foreign-born population by setting the level of immigration. In other words, while the government can do things to ameliorate low-income caused by such factors as changes in family structures or the economy, these are complex social phenomena and are not the direct result of a specific federal policy. In contrast, the low-income that results from immigration is avoidable in a way that is not the case for low-income caused by domestic conditions.

Low-income, poverty, and well-being

Low-income measures are not measures of poverty or well-being. Rather, they reflect a methodology by which is identified those who are substantially worse off than the average in terms of income. Being significantly worse off than the average does not necessarily mean that one is poor.Footnote 9 Low-income measures (which are based on family income, including government transfer payments and investment and pension income, as well as employment earnings, and provide a picture of the economic resources available to families) exclude non-economic aspects of human welfare. When an income cut-off is developed, below which a household is considered to be in low-income, society is divided in two groups—those with incomes below the line (the poor) and those whose incomes takes them above the line (the non-poor).Footnote 10 The major factor behind the income approach is the readily available information about income and income distributions. Sarlo (1996) argues that while income is acknowledged as an imperfect indicator of well-being for individual cases, in the aggregate it is a reasonably good proxy for the consumption choices available to households. This being the case, while low-income measures are commonly used as poverty lines, they have no officially recognized status as poverty lines in Canada.Footnote 11

In contrast to low-income measures, poverty takes into account many non-economic aspects of human welfare. According to the United Nations (1995), poverty takes various forms, including "lack of income and productive resources to ensure sustainable livelihoods; hunger and malnutrition; ill health; limited or lack of access to education and other basic services; increased morbidity and mortality from illness; homelessness and inadequate housing; unsafe environments and social discrimination and exclusion. It is also characterised by lack of participation in decision making and in civil, social and cultural life. It occurs in all countries: as mass poverty in many developing countries, pockets of poverty amid wealth in developed countries, loss of livelihoods as a result of economic recession, sudden poverty as a result of disaster or conflict, the poverty of low-wage workers, and the utter destitution of people who fall outside family support systems, social institutions and safety nets.” This being the case, Statistics Canada (2012) argues that defining poverty is not straightforward, as the underlying difficulty is that poverty is a question of social consensus, defined for a given point in time and in the context of a given country. As a result, decisions of what defines poverty are subjective and ultimately arbitrary.

As low-income is an indicator of the extent to which some Canadians are less well-off than others based solely on income, it is also not an overall measure of well-being. Well-being involves a multi-dimensional array of social, economic and environmental factors. The way they connect and interact has a large effect on our well-being.Footnote 12 Well-being is generally evaluated by taking into account a broad spectrum of factors, such as housing quality, income, employment, social support networks, educational attainment, governance, health, life satisfaction, safety, and work-life balance (see, for examples, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Better Life Index, the Canadian Index of Well-being, and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada’s Well-Being Indicators). This being the case, low-income, as a measure of equality, is a key component used in the analysis of economic well-being.Footnote 13

Measures of low-income

In order to establish the low-income situation of a population, several indicators have been developed for Canada. The most common of these measures include Statistics Canada’s Low-income Cut-off (LICO), the Low-income Measure (LIM), and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada’s Market Basket Measure (MBM). Each of these measures uniquely establishes thresholds and as a result report different incidences of low-income. According to Murphy, Zhang, and Dionne (2012), the primary purpose of Statistics Canada’s low-income lines are to provide some indication of the extent, nature, and evolution of persons with low-income who may be said to be at-risk of poverty.

Low-income status is determined using family or household income. As a family concept, low-income provides a better welfare perspective on a family or household economic resource position than individual income.Footnote 14 Since family members normally support each other financially it makes sense to look at families as economic units rather than considering each member of a family in isolation from the other members (See information box Family definitions used in low-income measures for details). As a result, low-income rates are based on family or household incomes (e.g., income from all group members is added together). If this total falls under the low-income line, all members are considered to be living in low-income, regardless of how much each person earns. Low-income measures account for family or household size in order to reflect the fact that a family or household’s needs increase as the number of its members increases.

As with all outcome measures, it is important to be aware of the inherent advantages as well as the disadvantages of the indicator. As mentioned, a key advantage of low-income measures is that they provide a better welfare perspective on an immigrant family’s economic resource position than individual earnings. Another advantage of low-income status over employment earnings as an outcome measure is that the low-income rate includes those who are unemployed and out of the labour market.Footnote 15 Further, low-income also takes into account sources of income other than earnings, such as social transfer benefits.Footnote 16 However, there are two problems common to all low-income measures worth mentioning. First, in using a low-income measure, all those identified as in low-income may not be poor.Footnote 17 Wealth (e.g., assets, home ownership, housing subsidies, etc.) is not taken into account when it comes to measuring low-income; this may matter more for some segments of the population (e.g., immigrants versus Canadian-born). If standard income-based calculations of low-income were refined to include consumption and assets, the rates of low-income could be much lower than those estimated using the standard measures. Examples include the self-employed with negative income, and recipients of capital gains or household transfers but who have little earned income. Second, low-income measures may not identify all those who are really in a low-income situation.Footnote 18 As an example, those who have to spend a lot on health care may end up with very little income for food, shelter, and clothing.

Statistics Canada’s family definitions

Census Family refers to married couples (with or without children of either or both spouses), couples living common-law (with or without children of either or both partners) or lone-parents of any marital status, with at least one child living in the same dwelling. A couple may be of opposite or same sex. 'Children' in a Census family include grandchildren living with their grandparent(s) but with no parents present.

Economic Family refers to a group of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling and are related to each other by blood, marriage, common-law or adoption. A couple may be of opposite or same sex. All census family persons are economic family persons. But the reverse is not true. Therefore, the concept of economic family may refer to a larger group of persons than does the census family concept.

Household refers to a person or a group of persons (other than foreign residents) who occupy the same dwelling and do not have a usual place of residence elsewhere in Canada. It may consist of a family group (Census family) with or without other persons, of two or more families sharing a dwelling, of a group of unrelated persons, or of one person living alone.

The economic family concept requires only that family members be related by blood, marriage, common-law or adoption. By contrast, the census family concept requires that family members be a male or female (male) spouse, a male or female (male) common-law partner, a male or female lone parent, or a child with a parent present. The concept of economic family may therefore refer to a larger group of persons than does the census family concept. For example, a widowed mother living with her married son and daughter-in-law would be treated as a non-family person under the definition of a census family. That same person would, however, be counted as a member of an economic family along with her son and daughter-in-law. Two or more related census families living together also constitute one economic family as, for example, a man and his wife living with their married son and daughter-in-law. Two or more brothers or sisters living together, apart from their parents, will form an economic family, but not a census family, since they do not meet the requirements for the latter. All census family persons are economic family persons. In contrast, Census families are strictly ‘two generations only’ families. As a result, the census family definition does not capture immigrants living in multi-generational, extended family, or multi-family homes.

Family structure refers to the combination of relatives that comprise a family. Classification of family structure considers the presence or absence of: legally married spouses or common law partners; children; and, in the case of economic families, other relatives. Statistics Canada uses the concept of major income earner to classify families (e.g., in a family, the major income earner is the person with the highest income before tax).

Source: Statistics Canada, 2007.

Low-Income Cut-Offs (LICOs)

Statistics Canada’s Low-income Cut-Offs (LICOs) are the most widely available measures of low-income in Canada, with the lengthiest historical series (data is available going back to the 1960s). The LICOs are income thresholds below which a family will likely devote a larger share of its income on the necessities of food, shelter and clothing than the average family.Footnote 19 The approach is essentially to estimate an income threshold at which families are expected to spend 20 percentage points more than the average family on food, shelter, and clothing.Footnote 20 An individual is considered to be in low-income if his/her total family income is below the LICO, and a family is in low-income if its total income is below the LICO.

The LICO is based on the economic family. The LICO varies by family size and the population of the area of residence. There are seven categories of family size from one person to seven or more persons, and five community sizes ranging from rural areas to cities with 500,000 or more residents.Footnote 21 The result is a set of 35 cut-offs; this variability is intended to capture differences in the cost of living between rural and urban areas. These LICOs were derived from an expenditure survey (1992 Family Expenditure Survey) and then compared to an income survey (Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics, SLID). The cut-offs are updated annually by Statistics Canada using the Consumer Price Index.

LICO is categorized as a relative measureFootnote 22, because LICOs are estimated based on average expenditures for basic needs. However, in practice, the LICO has become an absolute measure, that is, a pre-determined threshold income value below which a family can be said to be living in low-income. LICOs have been developed to identify low-income using both before and after tax income situations. Before-tax LICOs are based on total income including government transfer payments, but before deductions from federal and provincial / territorial income tax. After-tax LICOs are based on income after the payment of federal and provincial / territorial income taxes, but not other types of taxes that affect disposable income (e.g., sales tax, property tax, etc.). The use of before-tax LICOs (rather than after-tax LICOs) over states incidence of low-income, the reasons beingFootnote 23: 1) before-tax rates only partly reflect the entire redistributive impact of Canada's tax/transfer system because they include the effect of transfers but not the effect of income taxes; and 2) since the purchase of necessities is made with after-tax dollars, it is logical to use people's after-tax income to draw conclusions about their overall economic well-being. According to Murphy, Zhang, and Dionne (2012), the number of people falling below these cut-offs has been consistently lower on an after-tax basis than on a before-tax basis – a “progressive” tax rate system compresses the distribution of income and therefore, some families in low-income before taking taxes into account are relatively better off and not in low-income on an after-tax basis.Footnote 24

There are a few limitations worth noting with regards to using and understanding the results of low-income analyses based on LICOs. First, LICO does not account for provincial differences in costs of living. The national LICO (within family size and size of urban region) is applied to the provinces and regions. For example, for a family of four, the same LICO is applied to families living in large urban areas in Ontario and Quebec (e.g., Montreal and Toronto). Thus, LICOs do not take into consideration differences in living costs between the same-sized communities in different provinces, and there may be cost of living differences between these cities that are not accounted for in the LICOs (e.g., the cost of living in Montreal may be much lower than that in Toronto or Vancouver). This could introduce a bias for any comparison of levels of low-income among provinces.Footnote 25 This is a very important factor in low-income analysis of immigrants, given that most immigrants tend to settle in large urban cities.Footnote 26

Second, the LICOs may be becoming less relevant with time. The current LICOs are based on the relationship between the incomes and the consumption patterns of Canadian households as observed in 1992. While the annual Consumer Price Index is used to update the cut-offs, that is to take inflation into account, this does not reflect any changes that might occur over time in the average spending on necessities.Footnote 27 Thus the actual consumption base becomes less relevant with each passing year (and will continue to become less relevant in the absence of a rebasing of the measure).Footnote 28 It is generally thought useful to re-define consumption patterns on necessities over time (e.g., consider the impact on consumption patterns of Canadians from the recent oil boom and changes to cost of transportation, the recent housing boom, as well as health and personal care items).Footnote 29

Third, it has also been argued that LICO is not transparent to the public (it has been criticized for not being ‘simple’),Footnote 30 as there are numerous arbitrary choices (e.g., what is included and excluded with respect to food, shelter, and clothing, the regression model specification and assumptions, and income inclusions exclusions).Footnote 31 Fourth, LICOs are insensitive to the gaps (intensity) and trends of low-income, and as a result, Myles and Picot (2000) argue that researchers using the LICOs should be aware of the sensitivity of their results to the choice of cut-off levels. Fifth, the LICOs are not internationally comparable, as the LICO is Canadian-specific. Despite some concerns, the LICOs are commonly used to establish low-income rates and to help identify the low-income population. This being the case, there has been recent suggestion that the LICO be dispensed with, given that it is obsolete on a number of grounds.Footnote 32

Low-Income Measure (LIM)

Largely intended for the purpose of making international comparisons, Statistics Canada’s Low-Income Measure (LIM) is the most commonly used low-income line.Footnote 33 Statistics Canada has been producing the LIM since 1991 (although the time series has been extended back in time).Footnote 34 With LIM, a person is considered in low-income if their income is less than half of the population median income adjusted for household size (“adjusted” indicates that household needs are taken into account).Footnote 35 The median is calculated over the population of individuals, with each person in the population represented by its adjusted household income.Footnote 36 The LIM is then defined as 50% of the median of the adjusted household income observed at the person level.Footnote 37 A person with an adjusted household income below this level is considered to live in low-income.

The LIM is based on the household unit of sharing. While previously the economic family was the accounting unit in which individuals pooled income to enjoy economies of scale, the household has now replaced the economic family in the LIM. According to The Canberra Group (2001), the rationale for this change is twofold. Firstly, housing costs such as mortgage interest or rent and utilities are likely shared among individuals living in a dwelling, regardless if they are part of a different economic family (e.g., “household” allows a wider pooling of resources than the economic family).Footnote 38 Secondly, the household is the international standard when analysing income distribution.

LIM is a relative measure, with outcomes benchmarked, or compared to the population at a given point in time (e.g., 50% of median adjusted family income – that is, derived from the distribution of incomes in the underlying population in each year) (low-income depends on your income and that of others). The LIM is calculated three ways -- with market income, before-tax income, and after-tax income -- using the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID). LIMs vary with family size and are the same in all parts of the country. This means they do not reflect the different costs of living across the country. They also do not require updating using an inflation index because they are calculated using an annual survey of household income, the SLID. However, while the LIM is a Canada-wide line, geographic variations can be easily introduced with local LIMs.Footnote 39

There are two limitations worth noting with regards to using and understanding the results of low-income analyses based on the LIM. First, the LIM makes no direct connection with what would be deemed necessary for covering basic needs, since it refers strictly to the distance between a person’s income and the median.Footnote 40 Second, LIM thresholds change every year, meaning that setting goals is challenging. Many researchers fix the LIM for a period of time in order to provide a constant threshold over the period of analysis.Footnote 41 As well, given it is difficult to show annual progress towards a target because it changes every year (e.g., LIM is a relative measure), one could look at a moving average of the median income (e.g., three or five years).

Market Basket Measure (MBM)

The Market Basket Measure (MBM) was developed by Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) to represent a standard of living that is a compromise between subsistence and social inclusion that reflects differences in living costs across the country.Footnote 42 The beginning of the MBM time series is 2000. The MBM is based on the cost of a specific basket of goods and services representing a modest, basic standard of living.Footnote 43 The measure is sensitive to differences in the cost of the basket in different parts of Canada.Footnote 44 The basket includes food, clothing and footwear, shelter, transportation, and other goods and services such as expenditures on personal care, basic telephone service, school supplies, and modest levels of reading material, recreation and entertainment.Footnote 45 The MBM calculations involve a number of adjustments to family income, including deductions for child care costs, child support payments, payroll taxes and contributions, certain out of pocket expenses for health care and the cost of prescribed aids for persons with disabilities. The end result is income that approximates disposable income, rather than the less complex definitions of total income or income after income taxes that are used in other low-income measures.Footnote 46 The great advantage of the MBM is that it links the established low-income thresholds to actual living conditions and thus, in a way, to what is necessary to live decently in a given society.Footnote 47

The MBM is based on the economic family. A person in low-income is someone whose disposable family income falls below the cost of the goods and services in the Market Basket in their community or community size.Footnote 48 The thresholds are produced for a reference family of two adults aged 25 to 49 years and two children (aged 9 and 13). It provides thresholds for a finer geographic level than the LICO, allowing, for example, different costs for rural areas in the different provinces. An equivalence scale determines income thresholds for other family sizes. The equivalence scale is the square root of the economic family size.

MBM is an absolute measure, that is, a pre-determined threshold income value below which a family can be said to be living in low-income. Statistics Canada collects prices from a variety of sources to calculate the MBM. The Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) provides the income amounts that are used to estimate MBM rates.Footnote 49 Because the income concept used for MBM is the income available to purchase the goods and services that are contained in the MBM basket, there are no before and after-tax MBM low-income lines, as there are with both LICO and LIM. Rather, the general approach is to begin with total income and to subtract income taxes and other non-discretionary expenses from that amount (including Canada Pension Plan/Quebec Pension Plan contributions, Employment Insurance contributions, registered pension plans contributions, annual union and professional dues, support payments paid, work-related child care expenses, direct medical expenses, and public health insurance premiums).Footnote 50 This extends the traditional after-tax income concept, which takes income taxes into account but does not consider any other expenses.Footnote 51

There are a few limitations worth noting with regards to using and understanding the results of low-income analyses based on the MBM. First, data limitations imply that one has to make certain assumptions in calculating the costs of the MBM basket. For example, the cost of the basket in rural areas is the same as in the smallest urban centre(s) surveyed within a province.Footnote 52 Second, the food basket (based on the 2008 National Nutritious Food Basket) has been argued to contain more raw foods and foods less generally consumed among the low-income population.Footnote 53 There has also been some sentiment the food basket does not adequately reflect food choices of some visible minority, immigrant, and Aboriginal Canadians.Footnote 54 Third, arbitrary choice may have important implications. For example, Michaud, Cotton, and Bishop (2004) argue that the age of the used car and the frequency of replacement of that car in the MBM calculations have an effect on the amount of the private transportation component. For example, if a six year-old car were purchased every six years, instead of a five-year-old car every five years, the cost of private transportation would be reduced by $900.Footnote 55 Despite some limitations, the MBM provides an absolute measure of low-income that is an attempt to measure a standard of living that is a compromise between subsistence and social inclusion that reflects differences in living costs across the country.Footnote 56

How the measures compare

A natural question is how the measures compare. As described by Zhang, Murphy, and Michaud (2011), the three lines measure low-income differently. Under LICO, low-income incidence means the proportion of the population who are likely to spend a high proportion of income on necessities. In comparison, under LIM, low-income incidence means the proportion of the population whose income is below half of the median of the distribution, while under MBM it means the proportion of the population whose disposable income is below their local cost of the MBM basket. The three lines each have strengths and weaknesses, well summarized by Zhang, Murphy, and Michaud (2011). In terms of strengths, these authors argue that LICO has the longest history, LIM is simple and internationally comparable, and the MBM is intuitive and considers regional variations. In terms of weaknesses, the authors suggest that LICO is becoming less relevant, LIM can be counterintuitive sometimes, and the MBM contains many judgements and arbitrary choices. Although the three measures differ from one another, Statistics Canada (2012b) argues that they give a generally consistent picture of low-income status over time. The same Statistics Canada report goes on to argue that none of the measures is better than the others, as each contributes its own perspective and its own strengths to the study of low-income, so that cumulatively, the three provide a better understanding of the phenomenon of low-income as a whole.Footnote 57

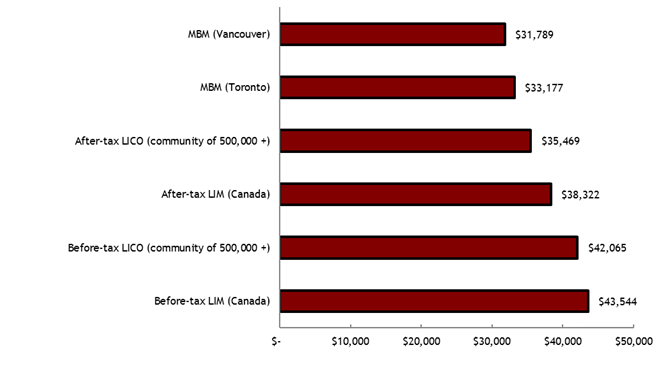

Illustrated in the chart below (Figure 1) are five different measures of low-income for a family of four in Canada in 2010. Where available, the low-income lines included are for a large city. According to the chart, although the various low-income measures are based on different foundations, the different low-income lines give somewhat similar results. The lowest low-income line is the MBM, set at $31,789 for Vancouver and $33,177 for Toronto, in 2010. The highest low-income line is in the amount of $43,544, using the before-tax LIM for Canada in 2010. The remaining low-income lines are within a few thousand dollars of one another.

Figure 1: The different measures of low-income - Selected low-income lines for a family of four, 2010

Text version: Figure 1: The different measures of low-income - Selected low-income lines for a family of four, 2010

| Measures | Low-income line |

|---|---|

| Before-tax LIM (Canada) | $43,544 |

| Before-tax LICO (community of 500,000 +) | $42,065 |

| After-tax LIM (Canada) | $38,322 |

| After-tax LICO (community of 500,000 +) | $35,469 |

| MBM (Toronto) | $33,177 |

| MBM (Vancouver) | $31,789 |

Source: Statistics Canada (2012), "Low Income Lines, 2010-2011", Income Research Paper Series.

A comprehensive study by Zhang (2010) examines and compares the sensitivity of different low-income lines (LICO, LIM, a fixed LIM, and MBM).Footnote 58 The study finds the low-income lines acted similarly in the long-run (and were sensitive to business cycle indicators such as the unemployment rate), but, in the short-run, often provided different results. The author argues that these finding suggests that a single line or index can be misleading in some circumstances. To demonstrate, the study examines different low-income lines across several disadvantaged groups of individuals and finds, as one example, that a fixed LIM is not as inclusive as MBM, or as capable as MBM in capturing individuals from families headed by recent immigrants, although the groups as a whole contributed more to low-income incidence under a fixed LIM than under MBM. Examining the capability of different lines in capturing low-income individuals, the author finds that for individuals being captured in MBM, there was good chance that other low-income lines failed to identify them as being in low-income, while for those who were above MBM, there was little chance they would be counted as low-income persons by other lines. However, among individuals who were above the fixed LIM line, there was still a non-trivial chance for them to be captured by other lines. Thus, it appeared that the MBM line would capture more individuals than the fixed LIM line, suggesting to the author that a fixed LIM line needs to be re-based periodically to maintain its relevance. The author also argues the results suggest that future development of the LIM lines needs to take regional variations in costs of living into consideration.

Applying the measures (low-income rate, low-income gap, and duration of low-income)

The LICO, LIM, and MBM are used to identify the low-income population in Canada and allow for the analysis of important trends and composition of Canadians at the low end of the income spectrum. Statistics Canada (2012b) explains the application of the different low-income measures, including the calculation of low-income rates and low-income gaps. First, to determine whether a person is in low-income, the appropriate low-income line (LICO or LIM, before or after tax, or MBM,) is compared to the income of the person‘s family (or household) and if their income is below the cut-off, the individual is considered to be in low-income. It is advised that persons in low-income be interpreted as persons who are part of low-income families (or households), including persons living alone whose income is below the cut-off. Low-income rates (often referred to as incidence of low-income), compare the number of persons or families considered to have low-income in a particular category, to all the persons or families in the same category. For example, the low-income rate for immigrants (or subgroup of immigrants, for example, based on age, sex, etc.) can be calculated as the number of immigrants (or subgroup of immigrants) in low-income divided by the total immigrant (or subgroup) population. Second, the same Statistics Canada report suggests that after having determined that an individual is in low-income, the depth of low-income can be analysed by using the amount that the person‘s family (or household) income falls short of the relevant low-income cut-off. As an example, an individual living in a family (or household) with an income of $15,000 and a low-income cut-off of $20,000 is said to have a low-income gap of $5,000; in percentage terms this gap is 25%. The average gap for a given population, whether expressed in dollar or percentage terms, is then the average of these values as calculated for each person.Footnote 59

It is also meaningful to consider the differences between those that have low-income for short spells (perhaps as very recent or recent immigrants) versus those who have long term, or chronic low-income, as the policy considerations may be different.Footnote 60 Policy analysts are more concerned with persistent or chronic low-income spells than all low-income spells, many of which are quite short.Footnote 61 Sawhill (1988) points out that estimates of low-income are extremely sensitive to accounting periods. Far more people experience short periods of temporary low-income, Sawhill argues, than are consistently in low-income over longer periods of time. As such, low-income rates using short accounting periods, such as one month, or in the case of immigrants even one year, will be much higher and more volatile than rates for longer periods. Duration of low-income might be particularly relevant when looking at the immigrant integration experience. For example, it may be of particular policy relevance to know which immigrants are in low-income, at what point in time after coming to Canada, and for how long they remain in low-income.

Researchers have developed statistical techniques by which to examine the duration and depth of low-income. For example, Picot, Hou, and Coulombe (2007) develop a Chronic Low-income Measure, which is used to assess the duration of low-income spells and is effective in examining trends of low-income rates (rather than measures of low-income at a point in time). These authors estimate an immigrant cohorts’ probability of entering and exiting a low-income spell, the association between cohort characteristics and the entry and exit rates, and the duration of low-income spells among selected immigrant and comparison cohorts between 1992 and 2004. Given an absence of a standard low-income measure in the data set being used (the LAD-IMDB Database)Footnote 62, the study defines low-income status based on 50% of median adult-equivalent adjusted family income.Footnote 63 The median adjusted family income is calculated on a constant dollar basis (the consumer price index adjusted to the 2003 value) in each of the years covered by the study (1992 to 2004), and the average of these values is used in determining the low-income cut-off in all years (e.g., a fixed LIM based measure). The study finds that the probability of entering low-income was quite high during the first year in Canada, ranging from 35% to 45% among cohorts entering through the 1990s and early 2000s. But by the second year in Canada, this probability had fallen to around 10% and remained low thereafter. Many of these low-income spells were found to be quite short. Approximately one-third exited the first low-income spell after one year, and a slightly higher percentage remained in low-income after three years. To get at repeated spells of low-income, the authors then take a longer-term perspective using their measure of ‘chronic low-income,’ that is, identifying immigrants who were in a low-income state for at least four of their first five years in Canada. Under this definition, 19% of immigrants entering through the 1990s found themselves in chronic low-income (about 2.5 times higher than the rate observed for non-immigrants); and, when chronic low-income was defined over a 10- rather than 5-year time span (in low-income at least 7 of the first 10 years in Canada), about 17% of entering immigrants found themselves to be in chronic low-income over this longer period. Among the conclusions made by the researchers is the finding that if immigrant families are not exposed to low-income immediately after their landing, they may escape it altogether.

Also in an effort to understand the transitory or persistent nature of low-income situations, a study by Ren and Xu (2011) examines low-income outcomes and duration using the Survey of Low-income Dynamics (SLID),Footnote 64 taking into account all three low-income measures (LICO, LIM, and MBM). The study (using logit regression models) is able to disentangle the determinants for transitory low-income from those for persistent low-income: student status and recent immigration are found more likely to be the key determinants for transitory low-income (an individual being in low-income for 1 to 3 years of the 6 years of panel data), while family composition (unattached individuals and lone parents), activity limitation, and less than high school education are more likely the key determinants for both transitory and persistent low-income (an individual being in low-income for 4 to 6 years). These observations are found quite robust under all three of the low-income thresholds across the two panels.

Low-income intensity is a measure of low-income that incorporates information from both the low-income rate (the proportion of the population below the low-income cut-off) and the low-income gap (the “depth” of low-income). Picot, Morissette, and Myles (2003) describe the low-income gap as the difference between the low-income cut-off and the average family income (among low-income families), divided by the low-income cut-off; the gap represents the “depth” of low-income expressed as a proportion the low-income cut-off. The authors explain that a gap of 0.32 means that the average family income of low-income families was 32% below the low-income cut-off. An increase in the gap, for example, from 0.32 to 0.34, implies an increase in the “depth” of low-income.Footnote 65 Myles and Picot (2000) observe that the low-income intensity measure can detect changes in income levels of low-income families. Moreover, in the study the measure captures impacts of social transfers to families by comparing the gap changes during the pre-transfer and post-transfer periods. According to Picot, Morissette, and Myles (2003), low-income intensity, which incorporates changes in both the low-income rate and the low-income gap, is very cyclical in nature.

Evident from this discussion is that a key consideration with respect to the immigrant population is deciding at what point in time low-income measurements are examined. A considerable amount of research shows there are consistent and observable patterns of immigrant labour market outcomes. There is an entry effect – with immigrants facing a penalty in initial employment earnings upon arrival in Canada – likely a result of being unfamiliar with the Canadian labour market. There is an integration effect -- an immigrant’s outcomes tend to improve the longer that person has been in Canada – as they gain ‘local’ experience. And there is a cohort effect -- different outcomes can result from differences in individual and labour market characteristics – for instance, unemployment may be high at the time of landing, affecting an immigrant’s labour market integration. As a result, consideration must be given as to when to evaluate the low-income situation of immigrants. After how many years in Canada should certain outcomes be achieved? One year? Five years? The answer likely depends on the specific policy-research question at hand.

Another key consideration with respect to the immigrant population is deciding an appropriate reference group by which to evaluate low-income trends over time. Picot, Lu, and Hou (2009) recommend that trend analysis be focused on low-income trends among immigrants relative to that of the Canadian-born. The reasoning being that any fluctuation in the rates associated with the business cycle is likely to affect the trends for the Canadian-born as well as for immigrants. Therefore, these authors argue, the comparison with the Canadian-born provides a rough control for business cycle effects. Again, however, the answer likely depends on the specific policy-research question at hand.

Factors influencing low-income among immigrants

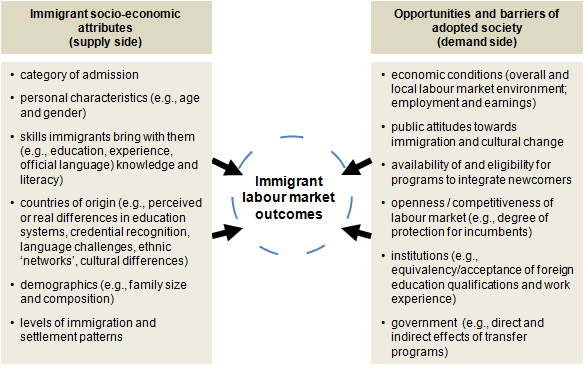

Low-income is widely accepted as an indicator of access to economic resources among members of society, and is therefore often used as a key indicator of immigrant integration and well-being. Central to the concept of low-income is the importance of socio-economic characteristics and conditions on differences seen among various populations. In other words, an analysis of immigrants in low-income necessarily requires offering “reasons why” things are different among various immigrant groups and the Canadian-born. Figure 2 below depicts the factors contributing to immigrant labour market outcomes (earnings). It is acknowledged in the research literature that low-income among immigrants has closely tracked earnings trends, since earnings are the most significant component of family income, which is used to calculate low-income rates.Footnote 66 In fact, Picot and Hou (2003) argue that explanations of declining entry level earnings among immigrants will no doubt explain to a considerable extent the rise in low-income. Noël (2012) argues that finding a job remains by far the best way of getting out of low-income, although the quality of one’s job is of importance to a person’s earnings trajectory: part time or precarious jobs may keep people in a situation of low-income.

As illustrated in Figure 2, understanding labour market outcomes among recent immigrants requires considering the relationship between the characteristics of immigrants, or the socio-economic attributes that immigrants bring with them (including immigration category, year of landing and years in Canada, age, education, gender, source country, family type, province of residence, occupation, etc.), and the opportunities and barriers presented by the adopted society, be they economic, social, or institutional. Overall, the causes of low-income amongst immigrants are multifarious. For working age immigrants, for example, the shift of their characteristics and the cyclical nature of the economy may lead to additional barriers to the labour market, while for senior immigrants, their family size, family type, and motivations for immigration may generate different income levels. This section presents a number of these important socio-economic factors, including research findings on how they impact the low-income situation of immigrants.

Figure 2: Factors influencing labour market outcomes among immigrants

Text version: Figure 2: Factors influencing labour market outcomes among immigrants

Immigrant socio-economic attributes (supply side)

- category of admission

- personal characteristics (e.g., age and gender)

- skills immigrants bring with them (e.g., education, experience, official language) knowledge and literacy)

- countries of origin (e.g., perceived or real differences in education systems, credential recognition, language challenges, ethnic ‘networks’, cultural differences)

- demographics (e.g., family size and composition)

- levels of immigration and settlement patterns

Opportunities and barriers of adopted society (demand side)

- economic conditions (overall and local labour market environment; employment and earnings)

- public attitudes towards immigration and cultural change

- availability of and eligibility for programs to integrate newcomers

- openness / competitiveness of labour market (e.g., degree of protection for incumbents)

- institutions (e.g., equivalency/acceptance of foreign education qualifications and work experience)

- government (e.g., direct and indirect effects of transfer programs)

Source: Thompson, 2004.

To gain a complete picture of immigrants’ low-income situation, immigrants’ wealth, foreign income and remittances back to their source countries would also need to be considered. This being the case, such information is generally not available, nor included in the calculation of income used to measure low-income status. Immigrants’ unreported foreign assets (e.g. unsold houses in source countries, savings in off-shore accounts, remittances received from relatives in source countries, etc.) and remittances to family members still living in source countries, may skew analysis in this regard. It is important to consider the absence of wealth from the above diagram. Wealth can be defined as the difference between an individual’s or a household’s total assets and total debts or liabilities (also referred to as net worth).Footnote 67 Dalgliesh (2008) argues that for immigrants, wealth plays a key role in the settlement and integration process since, for example, wealth may provide a financial cushion during an initial job search, and may be used later on as collateral to start a new business. Wealth also plays a key role in accessing credit, while savings may be used to pursue higher education, to start up a small business, and for retirement.Footnote 68 Hence, wealth offers an important cushion in the face of economic constraints and during periods of weak labour market outcomes. The literature on immigrant economic outcomes in Canada would be greatly enriched by strengthened understandings of immigrant savings, consumption, asset accumulation and investment.Footnote 69 Dalgliesh (2008) suggests that the level of asset holdings among immigrants may also provide a more comprehensive picture of household wealth, particularly because assets such as homes and businesses can be converted into liquid assets for consumption during retirement. Even so, Dalgliesh (2008) argues that the two most important factors contributing to the wealth accumulation of immigrants are labour market performance and relative earnings. For this reason, and because wealth is not accounted for in the measurement of low-income, the section that follows is focused on the factors that contribute to immigrant labour market outcomes and how these relate to their low-income situation.

Immigrant socio-economic attributes

Essential to the analysis of low-income is the importance of socio-economic characteristics and conditions on the differences seen among the different populations being investigated, in this case, Canadian-born individuals and various groups of immigrants. Theoretically, there are numerous factors associated with the immigrant population that would work against relatively higher low-income rates among immigrants in comparison to the Canadian-born. Spigelman (1998) describes a few of these factors: first, many recent immigrants gain entry through the points system, which admits persons with skills and resources deemed in demand by Canadian businesses; second, immigrants are more likely than Canadian-born people to have a university degree; third, the labour force participation of working-age immigrants is close to that of Canadian-born persons and a larger share of working-age persons in the population, combined with participation rates similar to those of the Canadian-born population, suggest a larger-than-average share of workers in the labour force; and fourth, immigrant families are less likely to be headed by a lone parent, and lone-parent families have significantly higher low-income rates. That being the case, it was shown at the outset of this report that immigrants in fact have higher low-income rates than those born in Canada, and this gap has become larger with time. What are the factors contributing to the fact that research to date suggests this group is increasingly susceptible to low-income? Of the socio-economic attributes of immigrants, the most important contributing to their economic outcomes are the following:

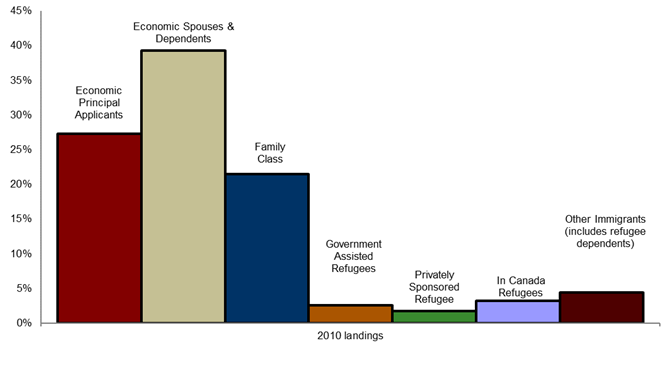

Immigrant category of admission

Canada’s immigration program covers three broad objectives, which correspond to three broad classes (see Figure 3). First, the economic class serves to foster the development of a strong, viable economy in all regions of the country. Second, the family class serves to facilitate the reunion in Canada of Canadian residents with close family members from abroad. Third, the refugee class serves to fulfill Canada's legal obligations with respect to refugees and to uphold its humanitarian tradition. Even so, within each of these broad categories, there are different categories and programs. For example, among the economic immigrants, there are skilled workers, provincial nominees, various business immigration categories and live-in caregivers. Further, within each of these categories there are principal applicants – those who are selected -- and their spouses and dependents. Family class includes close family members sponsored by a Canadian citizen or resident, including spouses, fiancés, dependent children, and parents and grandparents. Refugees also come to Canada in different ways. Persons resettled from abroad come either with government assistance (GAR) or private sponsorship (PSR), and there are also persons who successfully claim refugee status in Canada (landed in Canada). It can be expected that immigrants in different categories will “behave” differently and their behaviour must be assessed in the light of the policies under which they were admitted.

The different motivations for immigration, as represented by the different immigration categories, have significant effects on income outcomes. The expectation is for economic immigrants and their dependents to outperform other categories in the labour market.Footnote 70 It is also expected that family class immigrants, who are supported by established family sponsors, will not depend on social assistance.Footnote 71 It is not surprising, however, when refugees remain dependent on public support for extended periods following their arrival. In fact, refugees have a relatively high reliance on income support upon arrival (e.g., Government Assisted Refugees are provided income support under the Resettlement Assistance Program), but over time report a growing proportion of their income from employment earnings. In other words, deterioration in the national low-income rate of immigrants reveals little about the appropriate policy response to be taken or whether there is even a need to respond.Footnote 72 The outcome may reflect a change in mix across the immigrant categories, changing domestic labour market conditions or changing attributes of immigrants, or some combination of all these factors.Footnote 73

Figure 3: Immigrants come to Canada within distinct landing categories

Text version: Figure 3: Immigrants come to Canada within distinct landing categories

| Landing categories | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Economic Principal Applicants | 27% |

| Economic Spouses & Dependents | 39% |

| Family Class | 21% |

| Government Assisted Refugees | 3% |

| Privately Sponsored Refugee | 2% |

| In Canada Refugees | 3% |

| Other Immigrants (includes refugee dependents) | 4% |

Source: Citizenship and Immigration, Facts and Figures, RDM, 2010.

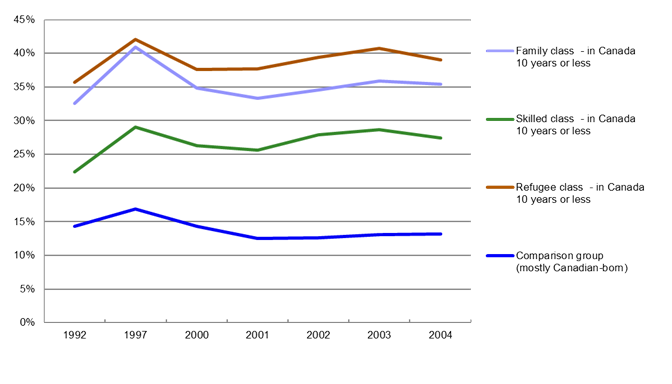

To date, the primary source of information regarding the low-income situation of immigrants has been Canadian Census data. As a result, there has been very limited information available with regards to the low-income situation of immigrants with respect to category of admission.Footnote 74 One study stands out as unique in this area: Picot, Hou, and Coulombe (2007) used the Longitudinal Administrative Database (LAD) and the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) for the years 1992 to 2004 to look at low-income rates of immigrants by category of admission (this study was described earlier in greater detail). Results from this study are reproduced in Figure 4 below, which depicts low-income rates of recent immigrants (who have been in Canada for ten years or less) by category of admission (family, refugee, and economic (excluding business class)) for the 1992 to 2004 tax years. The comparison group is made up of mostly the Canadian-born.Footnote 75 As shown, low-income rates were consistently lowest among those immigrants in the economic category (27.4% in the 2004 tax year), followed by those landing as family class immigrants (35.4% in the 2004 tax year), while highest among refugees (39.0% in the 2004 tax year).

Figure 4: Low-income ratesFootnote 76 of immigrants (aged 20 years and older) by category of admission, 1992-2004 tax years

Text version: Figure 4: Low-income rates of immigrants (aged 20 years and older) by category of admission, 1992-2004 tax years

| Year | Family class - in Canada 10 years or less |

Skilled class - in Canada 10 years or less |

Refugee class - in Canada 10 years or less |

Comparison group (mostly Canadian-born) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 33% | 22% | 36% | 14% |

| 1997 | 41% | 29% | 42% | 17% |

| 2000 | 35% | 26% | 38% | 14% |

| 2001 | 33% | 26% | 38% | 13% |

| 2002 | 35% | 28% | 39% | 13% |

| 2003 | 36% | 29% | 41% | 13% |

| 2004 | 35% | 27% | 39% | 13% |

Source: Picot, Hou, and Coulombe (2007), Longitudinal Administrative Database (LAD) and Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB).

The study by Picot, Hou, and Coulombe (2007) examines changes to the probability of entering and exiting low-income, as well as the prevalence of chronic low-income among entering immigrant cohorts. The results of the study show that refugees are more likely to enter and less likely to exit low-income than other immigrants, while recently-landed skilled immigrants have become more likely to enter low-income than family class immigrants, although equally as likely to exit. The authors argue this is most probably because the family class immigrants often enter an already economically established family. Moreover, the findings indicate that over the 1990s the share of skilled economic immigrants in chronic low-income rose from 16% to 50% and the share of university educated immigrants in chronic low-income rose from 12% to 36%.

Category of admission can inform the policy perspective with regards to rising low-income trends among immigrants. For example, a rising number of skilled worker immigrants, a high proportion who intended to work as information technology professionals (53% of all skilled worker principal applicants to Canada in 2003)Footnote 77 combined with the downturn in the information technology sector has been argued to help explain worsening low-income rates among skilled workers despite the strength of the overall economy over the period 2000 to 2003.Footnote 78 As evident, this information provides a crucial perspective when considering the situation from a policy angle.

Years since migration

Research consistently shows that low-income rates for immigrants who have been in Canada for longer periods of time are significantly lower than for those in Canada more recently (see, for example, Statistics Canada, 2008; Picot and Hou, 2003).Footnote 79 Immigrants and refugees often need some time to settle in their new country, and as a result, years since migration generally corresponds to improved economic and social outcomes. Based on 2006 Census data, Table 1 presents the after-tax low-income status (both LICO and LIM) of immigrants by number of years since immigration, for Canada, in 2005. As shown, low-income rates for immigrants who have been in Canada for longer periods of time are lower and declines are evident for additional years an immigrant has lived in Canada. For example, looking at persons with family income below LICO, immigrants who arrived in Canada between 2001 and 2004 had an after-tax low-income rate of 27.4% in 2005. This was almost three times higher than the corresponding rate of 9.5% for people born in Canada. However, this gap closes with additional time an immigrant has lived in Canada. Immigrants who had been in Canada for between 5 and 10 years (those who immigrated between 1996 and 2000) had a low-income rate of 20.6% in 2005, while for those with 10 to 15 years of residence (those who immigrated between 1991 and 1995), it dropped to 17.5%. Trends are similar for low-income status of immigrants based on the after-tax LIM. As will be seen, it is worth mentioning that immigrants who have been established in Canada for longer periods tend to be older.

Table 1: After tax low income status of immigrants by number of years since immigration, Canada, 2005

| Immigration status | Total number of persons | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) % | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian-born persons | 24,651,925 | 2,343,940 | 9.5% | 2,697,195 | 10.9% |

| Immigrantstable note * | 6,166,770 | 1,025,185 | 16.6% | 988,115 | 16.0% |

| Immigration period | Total number of persons | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) % | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrated before 1981 | 2,393,355 | 187,350 | 7.8% | 175,200 | 7.3% |

| Immigrated between 1981 and 1985 | 360,450 | 44,450 | 12.3% | 42,650 | 11.8% |

| Immigrated between 1986 and 1990 | 640,440 | 92,220 | 14.4% | 88,495 | 13.8% |

| Immigrated between 1991 and 1995 | 822,220 | 143,740 | 17.5% | 138,705 | 16.9% |

| Immigration period between 1996 and 2000 | 843,035 | 173,855 | 20.6% | 168,765 | 20.0% |

| Immigrated between 2001 and 2004 | 824,670 | 226,200 | 27.4% | 217,440 | 26.4% |

Source: Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population, CIC Custom Table and author's calculations.

Research findings consistently provide evidence supportive of this trend. Using data from the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) for the period 1993 to 2001, Palameta (2004) finds that recent immigrants (landed in Canada within the past 1 to 6 years) are two to three times more likely to experience low-income status (based on after-tax LICO) relative to the Canadian-born. Moreover, the study finds that recent immigrants, regardless of gender, level of education, family type, or province of residence are also more likely to experience low-income repeatedly relative to the Canadian-born.Footnote 80 In this study, immigrants who had been in Canada 7 to 16 years (mid-term immigrants) and those who had been in Canada for at least 17 years (early immigrants) were found no more likely than non-immigrants to experience low-income, and the author suggests the results imply that after a period of adjustment, immigrants generally integrate well into Canada’s economy.

Using data from the 1993 to 1998 panel of the SLID, Morissette and Zhang (2001) study the persistence of low-income status (based on after-tax LICO) for different groups at risk of low-income. They find that at least 20% of immigrants who arrived in Canada since 1976 experienced low-income for four years or more compared with 7% of the Canadian-born population. In contrast, for immigrants who arrived prior to 1976, only 6% experienced low-income for four years or more. While this study does not carry out an econometric analysis to control for years of residence in Canada (and as a result the findings are not necessarily representative of true cohort differences), these observations do imply considerable variation across immigrant groups in terms of low-income status over time.

Overall, examining the low-income situation of immigrants necessarily must account for years since migration. Differences in low-income trends between recent and established immigrants suggest different policy response. For example, recent immigrants may have low-income for short spells upon arrival as they settle into their new country, a year or maybe two, while others may have long term or chronic low-income, and the policy considerations may need to be very different. As pointed to earlier, a study based on the 1999 to 2004 and 2002 to 2007 panels of the SLID, by Ren and Xu (2011), finds that recent immigration (and student status) is more likely to be the key determinant for transitory low-income (versus family composition (unattached individuals and lone-parents), activity limitation, and less than high school education which are more likely the key determinants for both transitory and persistent low-income). This being the case, also using the SLID (for 2002 to 2004), Fleury (2007) finds that recent immigrants (those who immigrated to Canada between 1990 and 2004) are more vulnerable to low-income in both the short and the long term (based on after-tax LICO). However, as for other Canadians, low-income among recent immigrants is found in this study to be a very dynamic phenomenon; the time spent in low-income for working-aged adults is very similar whether they are recent immigrants or not. Again, information on years spent in Canada is crucial when considering policy response to the situation of immigrants in low-income.

Personal characteristics (e.g., age and gender)

Low-income status is very much a life-cycle phenomenon.Footnote 81 As a result, age is a crucial factor in studying both the immigrant and the Canadian-born low-income situation. In addition to this, age at the time of an immigrant’s arrival matters greatly for economic outcomes: research consistently shows that the younger an immigrant is when landing in Canada, the better are his or her long-term labour market outcomes relative to those immigrating at a later age, and the closer to the Canadian-born experience.Footnote 82 The younger an immigrant is when landing in Canada, the more time the immigrant has to gain human capital skills specific to the Canadian labour market. Simply put, the earlier in life immigrants arrive, the more their education and work experience will resemble that of their Canadian-born counterparts and the easier it will be to learn an official language. Conversely, the older an immigrant is at landing, the more likely they are to have accumulated human capital through foreign work experience and likely the more difficulty he or she will have in terms of integrating into the labour market.

Among all immigrants, it is children and young adults who are more likely, relative to those aged 45 years and over, to live in a low-income situation. Based on 2006 Census data, Table 2 presents the after-tax low-income status (both LICO and LIM) of immigrants by number of years since immigration and age, for Canada, in 2005. As shown, looking at persons with family income below LICO, 33% of immigrants under age 15 years lived in a low-income situation in 2005, as did 26.7% of those aged 15 through 24 years. For immigrants aged 25 to 44 years, those of prime working ages, 19.5% were in a low-income situation in 2005. Immigrant children under the age of 15 years were more than three times as likely as their Canadian-born counterparts (11.7%) to be classified as being in a low-income situation in 2005. In contrast, low-income rates were much lower among the older immigrant population during the same year, at 13.2% for those immigrants aged 45 through 64 years and 8.7% for those aged 65 years and over (corresponding rates for similar aged Canadian-born persons were 8.9% and 5.7%, respectively).Footnote 83 By years spent in Canada, after-tax low-income rates were highest in 2005 among the most recent immigrant cohort (those who immigrated between 2001 and 2004) and who were youngest, with an incidence of low-income of 30.8% for those under age 15 years, and 31.8% for those aged 15 to 24 years; this compares with 25.7% among those aged 25 to 44 years, 25.8% among those aged 45 to 64 years, and 20.1% among those aged 65 years and older. In contrast, after-tax low-income rates were lowest in 2005 among the more established immigrant cohorts. For example, among those who immigrated between 1991 and 1995, those who were under age 15 years had an incidence of low income of 19.2% in 2005, and those aged 15 to 24 years had an incidence of low-income of 20.5%; this compares with 16.8% among those aged 25 to 44 years, 17.3% among those aged 45 to 64 years and 15.3% among those aged 65 years and older. Trends are similar for low-income status of immigrants based on the after-tax LIM.

Table 2: After tax low income status of immigrants by number of years since immigration and age, Canada, 2005

Table 2A: Canadian-born persons

| Age | Number of persons | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) % | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total - Canadian-born persons | 24,651,925 | 2,343,940 | 9.5% | 2,697,195 | 10.9% |

| Under 15 | 5,182,635 | 605,780 | 11.7% | 705,155 | 13.6% |

| 15 to 24 | 3,577,980 | 428,160 | 12.0% | 483,145 | 13.5% |

| 25 to 44 | 6,654,865 | 574,045 | 8.6% | 656,895 | 9.9% |

| 45 to 64 | 6,438,070 | 575,445 | 8.9% | 677,490 | 10.5% |

| 65 and over | 2,798,375 | 160,510 | 5.7% | 174,510 | 6.2% |

Table 2B: Immigrantstable note *

| Age | Number of persons | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) % | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total - Immigrants | 6,166,770 | 1,025,185 | 16.6% | 988,115 | 16.0% |

| Under 15 | 345,405 | 113,965 | 33.0% | 110,925 | 32.1% |

| 15 to 24 | 547,525 | 145,990 | 26.7% | 148,000 | 27.0% |

| 25 to 44 | 1,972,225 | 384,465 | 19.5% | 365,830 | 18.5% |

| 45 to 64 | 2,095,825 | 275,765 | 13.2% | 277,455 | 13.2% |

| 65 and over | 1,205,800 | 105,000 | 8.7% | 85,900 | 7.1% |

Table 2C: Immigrated before 1981

| Age | Number of persons | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) | Persons with family income below LICO (after tax) % | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) | Persons with family income below LIM (after tax) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total - Immigrated before 1981 | 2,393,355 | 187,350 | 7.8% | 175,200 | 7.3% |

| Under 15 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 15 to 24 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 25 to 44 | 323,905 | 28,335 | 8.7% | 28,760 | 8.9% |

| 45 to 64 | 1,123,460 | 99,110 | 8.8% | 102,405 | 9.1% |

| 65 and over | 945,995 | 59,905 | 6.3% | 44,040 | 4.7% |

Table 2D: Immigrated between 1981 and 1985