2023 Settlement Outcomes Report: Part 3 – Place-based Programming in Regional Immigration

Download: Part 3: Place-Based Programming in Regional Immigration (PDF, 2.3 MB)

On this page

- Introduction

- Recruitment and retention of newcomers

- Settlement outcomes of PBI newcomers

- Community contributions

- Conclusion

- Annex: Approaches to supporting RNIP newcomer integration

- Data sources

- Endnotes

Introduction

For most of Canadian history, the federal government played a primary role in the selection of immigrants. Over the last few decades however, this approach evolved with the provinces and territories taking more responsibility in the selection of immigrants. Agreements with different provinces in the late 1990s eventually led to the creation of the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP). The PNP is a jointly administered immigration program which provides provinces and territories with an opportunity to leverage immigration to address their specific economic development needs. The PNP paved the way for more involvement at the regional and community level in the selection and integration of economic immigrants using a place-based approach to immigration.

Place-based immigration (PBI) initiatives are designed to attract immigrants to settle in communities across Canada in order to spread the economic benefits of immigration. The Atlantic Immigration Program (formerly pilot) and the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot were established with these goals. They are delivered jointly by IRCC and the respective provincial/community partners. The design of these initiatives have distinct settlement components that seek to leverage settlement services and supports to aid with the integration and retention of newcomers. As a result, this part of Settlement Outcomes Report is focused on these two initiatives at similar points of maturity (i.e. as pilots).

IRCC’s Regional Immigration Programs (with flagship settlement components)

Text version

The diagram describes the design of the AIP and RNIP Pilot.

AIP Key Objectives: Create a pathway for skilled foreign workers and international graduates (from a Canadian institution) who want to work and live in the Atlantic provinces. Help employers hire qualified candidates for jobs they haven’t been able to fill locally.

AIP Timeline: Established in 2017 as a pilot. Became a permanent program in 2022.

AIP Pilot Locations: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador

AIP Settlement Elements: Required Settlement Plans (New!). Employer Provision of Settlement Supports (New!). Intercultural Competency Training for Employers (New!). Regular IRCC-funded Settlement Services.

RNIP Key Objectives: Create a pathway for skilled foreign workers who want to work in one of the 11 participating communities in northern Ontario and western Canada. Spread economic benefits of immigration to smaller communities in Canada.

RNIP Timeline: Established in 2019 as a pilot. Pilot extended in 2022, and 7 communities expanded their geographic boundaries.

RNIP Pilot Locations: North Bay (Ont.); Sudbury (Ont.); Timmins (Ont.); Sault Ste. Marie (Ont.); Thunder Bay (Ont.); Brandon (Man.); Altona/Rhineland (Man.); Moose Jaw (Sask.); Claresholm (Alta.); West Kootenay (BC); North Okanagan Shuswap (BC);

RNIP Settlement Elements: Required volunteer-matching with established members of community (New!). Provision of settlement supports from employers and economic development organizations (New!). Regular IRCC-funded Settlement Services.

Note that this is not an evaluation of the pilots. Rather, this part of the report focuses on the settlement outcomes of newcomers in the pilot and the role of local actors in the settlement journey of pilot participants. It also includes a brief exploration of retention outcomes as it relates to settlement and integration.

A place-based approach to immigration

Increasingly, researchers are looking at how the unique geographic, demographic and social dynamics of a place influence newcomer outcomes.Footnote 1 Adopting a place-based lens allows for a better understanding of newcomer settlement experiences in different parts of Canada. It also provides an entry-point to better understanding the impact of IRCC’s national Settlement Program at the regional and community levels. More specifically, small and rural communitiesFootnote 2 outside of census metropolitan areas (CMAs)Footnote 3 and northern communitiesFootnote 4 have very unique contexts that merit distinct focus. The AIP and RNIP were designed to do exactly that – i.e. focus on the unique needs of specific communities and the newcomers arriving in those destinations.

The Atlantic Immigration Pilot (AIP) was initially established in 2017 as a response to persistent labour market shortages in the Atlantic provinces. In the years leading to the pilot from 2012 to 2018, Atlantic Canada’s labour force declined by 2.4% (i.e. 31,000 people).Footnote 5 Multiple factors contributed to that decline, including outmigration, an aging population, and lower immigrant retention. As a result, the AIP was designed as a five-year pilot in Atlantic Canada to test a new approach for attracting and retaining skilled immigrants and international graduates. The pilot involved a new partnership delivery approach that focused on collaboration between IRCC, the Atlantic provincial governments, the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, settlement service providers and employers. For example, employers worked with federally- and provincially-funded settlement service providers to facilitate access to settlement services. As a result of early pilot successes (discussed later in this report), the permanent Atlantic Immigration Program was launched in 2022.

The Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot (RNIP) became another avenue to test new approaches in regional immigration. While the AIP focused on the Atlantic provinces, other small, rural and northern communities around Canada faced similar economic and demographic challenges. Across Canada, rural populations are growing fifteen times slower compared to urban areas.Footnote 6 Similarly, northern communities across Canada face labour shortages in sectors including: healthcare, hospitality, retail, manufacturing, and transportation.Footnote 7 This creates challenges for the future of these communities. The RNIP was established in 2019 to complement other immigration pathways, recognizing the particular needs and realities of northern and rural Canada. The pilot operates in 11 communities across Northern Ontario and Western Canada (five provinces in total). The pilot is community-driven meaning that the participating communities (represented by local Economic Development Organizations) set their priority sectors/occupations and establish the criteria to assess immigrant candidates based on local needs. They are also responsible for championing the benefits of immigration, matching newcomers with members of the community, and connecting newcomers to services.Footnote 8

Recruitment and retention of newcomers

Immigration is decidedly a useful mechanism to support the economic and demographic challenges facing the Atlantic provinces as well as other small, rural, and northern communities across Canada. Despite their important economic contributions to Canada and other attractive aspects, rural and smaller communities have traditionally struggled to attract and retain immigrants. Large urban centres attract immigrants for many reasons including: lifestyle, access to job opportunities, and the presence of existing cultural networks. Additionally, newcomers may know less about rural and smaller communities. As such, regional pilots, like AIP and RNIP were designed to recruit and retain skilled immigrants. This section explores how well PBI pathways have achieved those recruitment and retention goals.

In 2021, a greater share of the immigrant population lived in a large urban centre (i.e. CMA) compared to the Canadian-born population.

Text version

This bar graph shows that 92% of the immigrant population lived in a large urban centre in 2021, compared to 68% of the Canadian-born population.

Recruitment of newcomers through PBI initiatives

A flagship feature of these initiatives is the involvement of local actors in the selection of immigrants. Unlike other immigration programs where individuals apply directly to IRCC to immigrate to Canada, these initiatives are community/employer-driven meaning that local actors are involved in recruiting and selecting newcomers, as a first step. Specifically, these initiatives aim to attract and select newcomers from identified occupations to fill labour shortages. Since its creation, the AIP has brought over 18,450 new permanent residents to Atlantic Canada.Footnote 9 In fact, the pilot is a key driver contributing to the Atlantic provinces welcoming its highest shares of recent immigrants compared to previous census years.Footnote 10 Moreover, the 2020 evaluation of the AIP also found that the pilot was effective at recruiting newcomers to fill relevant job vacancies in the region (i.e. in sales and service, construction trades, transportation and health care).Footnote 11

International students and the Atlantic Immigration Pilot

Recruiting international students was an important aspect of the AIP. In the year prior to the pandemic (2019), New Brunswick increased annual transitions of International Students to Permanent Residents by 91% compared to 6% for all of Canada.

Source: IRCC Permanent Resident Database

Conversely, the RNIP was launched in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, which contributed to lower than expected numbers of arrivals in the first year of the pilot. Still, by the end of December 2022, 1,745 newcomers had landed through the pilot.Footnote 12 RNIP employers focused on recruiting temporary residents (i.e. applicants already in-Canada) to fill job vacancies in sectors such as accommodation and food services, health care and social assistance, retail trade, manufacturing and transportation. Initially, communities were given three years to issue recommendations under RNIP. However, the pilot was amended in September 2022 to extend their participation to August 2024. This amendment also included boundary expansions for seven of the eleven communities to allow more employers to benefit from the pilot. A forthcoming evaluation of the RNIP at the end of the pilot period will assess the effectiveness of the recruitment and selection approaches taken by the communities.

Importantly, recruitment and selection are only the beginning of a newcomers’ journey. These initiatives must ultimately work to retain newcomers in order to successfully address the issues outlined earlier (i.e. demographic and economic challenges).

Retention of newcomers from the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program

Prior to the implementation of the AIP, the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) was the main pathway to bring newcomers to Atlantic provinces. PNP retention rates before the launch of the AIP show that the Atlantic region had significantly lower retention than other provinces, an issue the AIP was developed to address. Three years into the pilot, it had achieved that goal. The one-year retention rate of skilled workers and skilled trades categories had risen substantially in all Atlantic provinces. This trend was first reported in IRCC’s 2020 Evaluation of the Atlantic Immigration Pilot but also observed in the recent 2021 Statistics Canada IMDB data.Footnote 13

Notably, the evaluation found that retention rates have decreased since that first year. Despite the drop, all Atlantic provinces saw a drastic increase in both their 1 and 2-year retention rates compared to previous years—with Prince Edward Island seeing the biggest increase. The AIP Evaluation provided more insight into this finding through a newcomer survey. The top reasons survey respondents indicated that they wanted to stay in their province were: they liked their community, they felt that the cost of living was affordable, they liked their job, and they had family or friends in the community/province. This suggests that the AIP was relatively successful at recruiting newcomers who wanted to live in the Atlantic provinces, as well as retaining them.

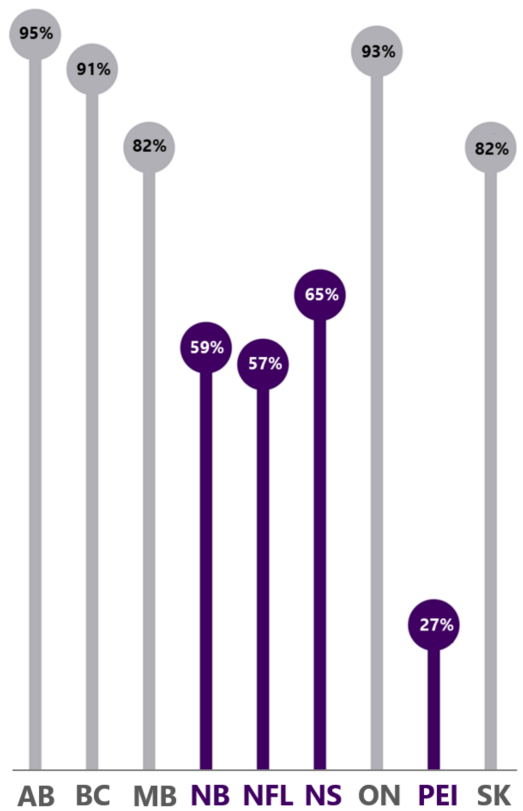

Before the AIP (2002-2014), the Atlantic provinces had the lowest retention rates of PNP principal applicants.

Source: IRCC (2018) Evaluation of the Provincial Nominee Program

Text version

This lollipop column chart shows that the Atlantic provinces had the lowest retention rates of PNP principal applicants across Canadian provinces. Alberta had 95% retention. BC had 91% retention. MB had 82% retention. NB had 59% retention. NFL had 57%. NS had 65% retention. ON had 93% retention. PEI had 27% retention. SK had 82% retention.

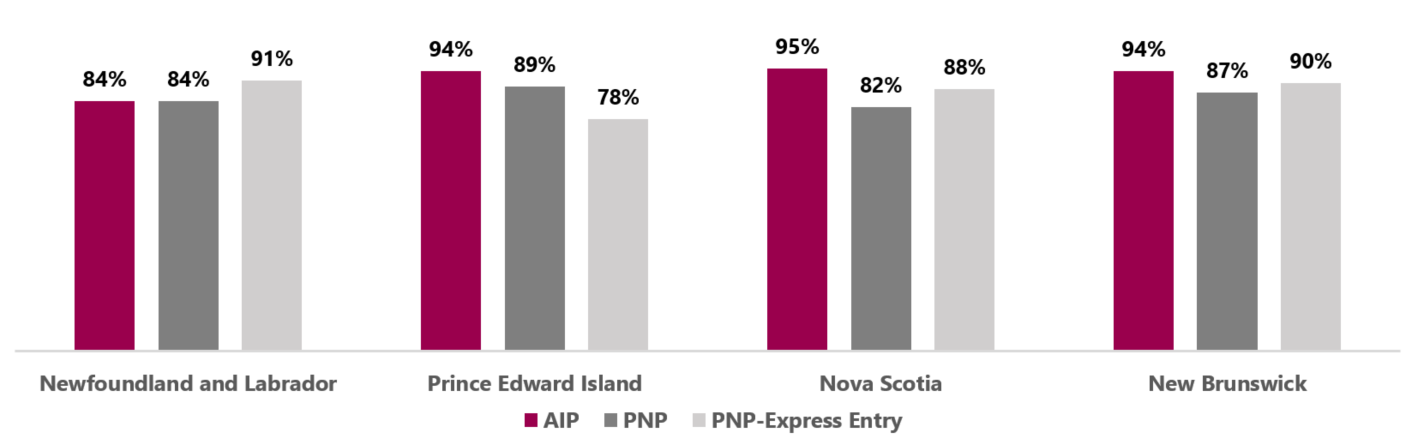

By the end of the pilot, AIP newcomers had the highest first-year retention compared to other economic streams in the Atlantic provinces (except for Newfoundland and Labrador).

-

Text version

This grouped column chart shows that AIP retention was higher in the Atlantic provinces compared to PNP and PNP-Express Entry.

Newfoundland and Labrador: AIP retention was 84%. PNP retention was 84%. PNP-Express Entry was 91%.

Prince Edward Island: AIP retention was 94%. PNP retention was 89%. PNP-Express Entry retention was 78%.

Nova Scotia: AIP retention was 95%. PNP retention was 82%. PNP-Express Entry retention was 88%.

New Brunswick: AIP retention was 94%. PNP retention was 87%. PNP-Express Entry retention was 90%.

Retention of newcomers from the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot

Prior to the 2019 launch of the RNIP, small and rural communities were also facing challenges attracting and retaining newcomers. According to census data, immigration to small centres and rural areas was declining in the years preceding the RNIP and before the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, northern communities were also facing challenges attracting and retaining newcomers. For example, North Bay (a northern Ontario community) had relatively little immigration despite an aging population and workforce.Footnote 14

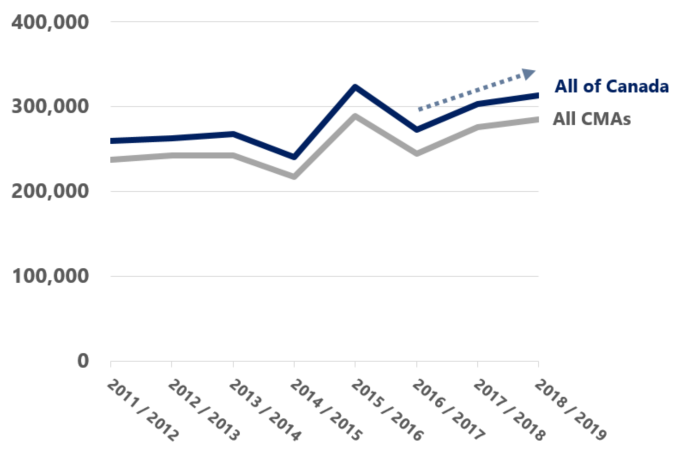

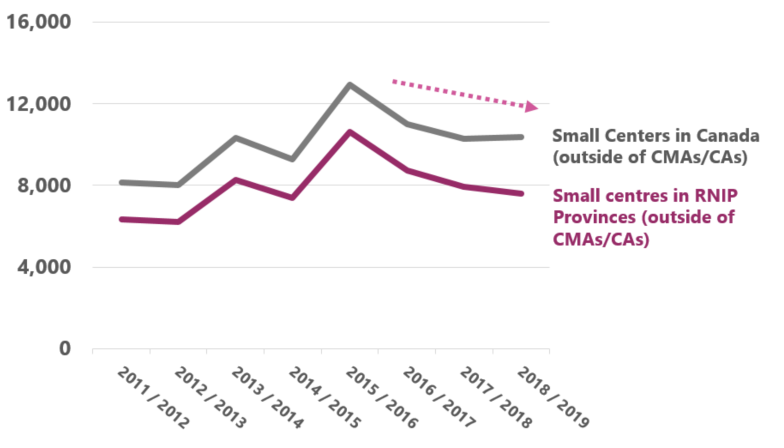

In the years prior to RNIP, immigration as a whole was increasing, including in large urban centres (CMAs). However, at the same time, immigration to rural areas and small centres was decreasing.

Immigrants in Canada and large urban centers (CMAs)

Components of population change by census metropolitan area and census agglomeration, 2016 boundaries

-

Text version

This line chart shows that immigration to Canada and large urban centres was increasing, especially between 2016/17 and 2018/19. The series displayed are: All of Canada, and All CMAs.

Immigrants in small centres (outside CMAs/CAs) and RNIP provinces

Components of population change by census metropolitan area and census agglomeration, 2016 boundaries

-

Text version

This line chart shows that immigration to small centres in Canada (outside of CMAs/CAs) and immigration to small centres in RNIP Provinces (outside of CMAs/CAs) was decreasing, especially between 2016/17 and 2018/19. The series displayed are: small centres in Canada (outside of CMAs/CAs) and immigration to small centres in RNIP Provinces (outside of CMAs/CAs).

Early insights into the pilot present promising retention results. In a 2022 departmental survey of RNIP newcomers (three years since the launch of the pilot) the vast majority of the 276 survey respondents indicated they were still living in their RNIP community and had no plans to leave.

The top reasons RNIP Survey respondents indicated that they stayed in their community were similar to AIP Survey respondents: they liked living in a smaller/rural community, they liked their job and they felt welcomed in their community. These results were further substantiated with RNIP focus group participants who indicated the reasons they chose to apply to the pilot was because they preferred smaller communities for affordability and lifestyle reasons. Among the respondents who left or planned to leave their RNIP community, the top reason for leaving was related to accessing services that could not be found in their community (e.g. a specialized doctor, or higher education). A recent study on smaller centres in southern Ontario also found that newcomers chose to stay in their communities for lifestyle and affordability reasons, but may leave in the future so that their children can access universities in large centres.Footnote 15

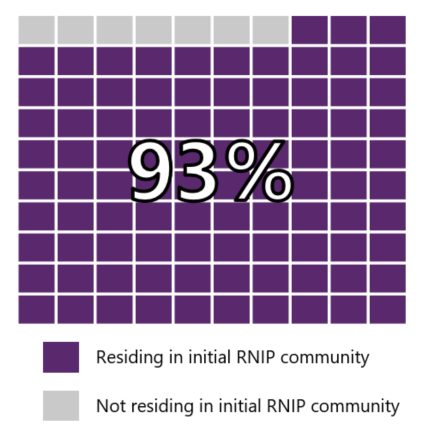

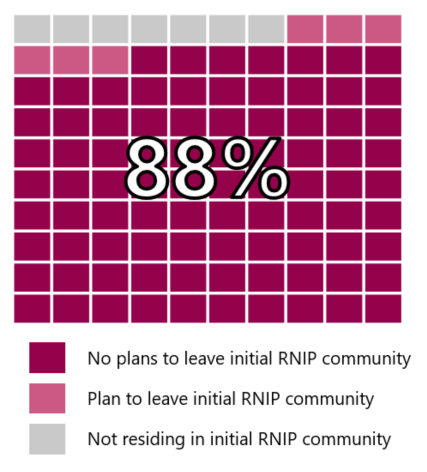

93% of RNIP survey respondents stayed in their RNIP community and 88% had no plans to leave.

Retention of RNIP survey respondents

-

Text version

This waffle chart shows that 93% of RNIP survey respondents were still residing in their initial RNIP community.

Future plans of RNIP survey respondents

-

Text version

This waffle chart shows that 88% of RNIP survey respondents had no plans to leave their initial RNIP community.

Source: IRCC (2022) Survey of RNIP Newcomers

Note: There are different ways to assess retention. For this survey, retention was assessed at specific point in time (October 2022). Spouses were included in this analysis, however even after removing spouses, the results stayed the same with 93% of PA respondents staying in their community.

Evidence also shows that pre-admission work experience in a newcomer’s province/territory is an important factor that influences immigrant retention.Footnote 16 So the fact that the majority of RNIP newcomers were former temporary residents (sometimes from within the community) may also explain these early retention results. However, the impacts of the pandemic could also be contributing factor. Travel restrictions, physical distancing requirements, economic challenges, and uncertainty associated with the pandemic could have dissuaded newcomers from moving away. A more detailed evaluation of the RNIP will provide longer-term insight into the retention outcomes of RNIP newcomers. However, these early results combined with the AIP evaluation results provide promising indication that newcomers from PBI pathways may have strong retention outcomes.

Retention, however, is the end result of many factors that contribute to a newcomers’ decision to stay or leave a community. Undoubtedly, one of those contributing factors is how well their needs are met during their settlement journey.

Settlement outcomes of PBI newcomers

The first Settlement Outcomes Highlights Report (PDF, 4.11 MB) identified that the “starting line” is different for each newcomer, and that specificity in settlement service programming may improve settlement outcomes. By extension, the settlement supports offered through the AIP and RNIP were designed to support newcomers in rural and smaller communities – primarily by making certain aspects of settlement programming mandatory and also by incorporating other local actors. Unlike other immigration pathways, PBI initiatives have settlement requirements for employers and partners to fulfill. For the AIP, a major feature of the pilot was the employer-driven approach and the mandatory settlement plans. Employers worked directly with federally and provincially-funded SPOs to support the settlement and retention of AIP newcomers and their families. Specifically, employers committed to fulfilling settlement-related obligations including ensuring that newcomers had settlement plans administered by service providers. These plans identified needs such as: understanding life in Canada, receiving employment supports, building language skills, accessing community services, and more. Employers also committed to creating welcoming workplaces.

The RNIP similarly has flagship settlement requirements associated with its design. The 11 participating communities represented by their local Economic Development Organizations (EDOs) work in collaboration with employers, municipalities, service providers, and other stakeholders to support the settlement needs of RNIP newcomers and their families. Specifically, the EDOs committed to work with these partners to: promote the benefits of immigration to community members and employers, ensure that newcomers have access to settlement services, and are offered to be matched with a volunteer for general orientation and support. However, the implementation and reporting of these commitments have been notably inconsistent. With that said, the following section makes use of the information and data available to assess the settlement outcomes of AIP and RNIP newcomers, and explore how the pilots’ designs may have contributed to those outcomes.

IRCC-funded settlement service usage

A network of 550 organizations across Canada are funded by IRCC to deliver settlement services to newcomers in various formats. As with other immigrants, AIP and RNIP newcomers could access these organizations’ services. In fact, both AIP and RNIP participants used settlement services at comparable rates to other economic immigrants in their area (e.g. PNP, Express Entry).Footnote 17 Also similar to other newcomers from traditional pathways, Information and Orientation Services was also the top service accessed by both AIP and RNIP participants.

Given the stronger emphasis on settlement supports embedded within these PBI initiatives, one might expect uptake to be higher for AIP and RNIP newcomers than other economic pathways. There are a few potential reasons that might explain why their uptake rates are not higher. First, this may simply be a result of pilot participants’ lack of awareness of the settlement services they could access. According to the RNIP Newcomer Survey, 27% of respondents were not aware of settlement services. Similarly, the AIP evaluation found that 21% of surveyed principal applicants were not aware that they could access settlement services.

That said, it could also be that these newcomers from PBI pathways were not looking for services because their major needs were already addressed. Unlike other economic pathways, AIP and RNIP principal applicants already have a job offer, and a commitment from their employers to support their settlement. Furthermore many were already living in Canada as temporary residents.

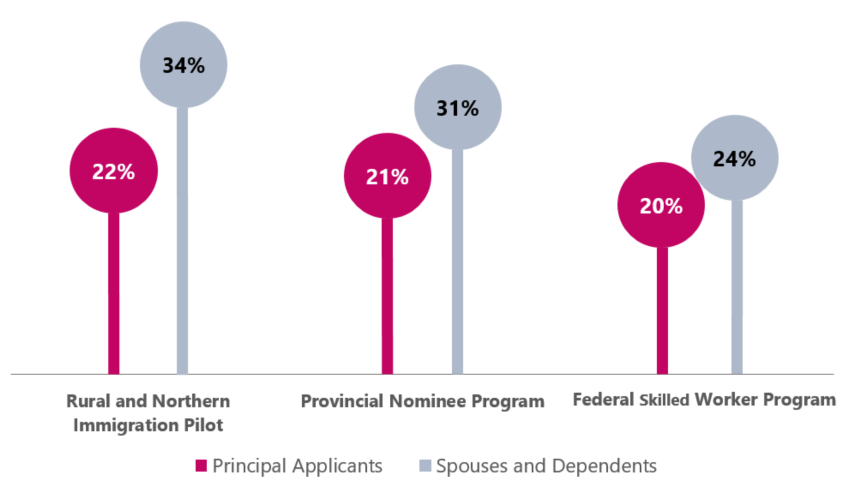

Service uptake of RNIP clients was comparable to other economic programs in the region.

Source: IRCC Permanent Residence Database and iCARE

Service Data Range: October 2019 – February 2023

Admission data range: October 2019 to January 2023

-

Text version

This lollipop column chart shows that service uptake of RNIP clients (both Principal Applicants and Spouses & Dependents) was comparable to PNP and the Federal Skilled Worker Program.

Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot: 22% uptake for Principal Applicants. 34% uptake for Spouses and Dependents.

Provincial Nominee Program: 21% uptake for Principal Applicants. 31% uptake for Spouses and Dependents.

Federal Skilled Worker Program: 20% uptake for Principal Applicants. 24% uptake for Spouses and Dependents.

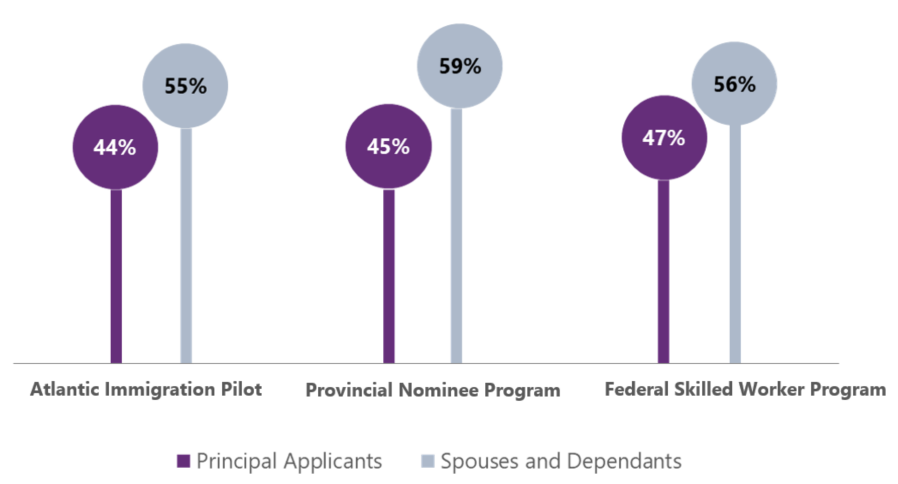

Service uptake of AIP newcomers was comparable to other economic programs in the region.

Source: IRCC (2020) Evaluation of the Atlantic Immigration Pilot

Service Data Range: March 2017 to June 2020

Admission data range: March 2017 to December 2019

-

Text version

This lollipop column chart shows that service uptake of AIP clients (both Principal Applicants and Spouses & Dependents) was comparable to PNP and the Federal Skilled Worker Program.

Atlantic Immigration Pilot: 44% uptake for Principal Applicants. 55% uptake for Spouses and Dependents.

Provincial Nominee Program: 45% uptake for Principal Applicants. 59% uptake for Spouses and Dependents.

Federal Skilled Worker Program: 47% uptake for Principal Applicants. 56% uptake for Spouses and Dependents.

On the other hand, another reason for the relatively similar uptake rates could be the unintended impact of these initiatives on the overall availability of services. To be clear, IRCC-funded providers serve all eligible newcomers in their area regardless of their immigration pathway. Therefore a change in landing patterns (with more newcomers arriving in different areas) and the additional emphasis on settlement services in these communities might have positively impacted newcomers arriving through other pathways.

In fact, the AIP evaluation found that settlement service usage for all economic immigrants in the Atlantic region was higher than historical averages. Service providers in the Atlantic region expanded their services geographically to account for these new landing patterns. Prior to the inflows of immigrants through the AIP, service providers in the region were offering settlement services in a limited number of locations mostly in larger centres. Following greater inflows to communities that would not normally receive immigrants, more service providers opened satellite offices. For example, between 2018 and 2019 the Association for New Canadians in Newfoundland established satellite offices in five immigrant growth areas in order to serve more newcomers.Footnote 18 The Rural Settlement Network in New Brunswick and the PEI Community Navigators initiative are other examples of how the settlement offerings expanded to serve newcomers in smaller and rural centres across the region.

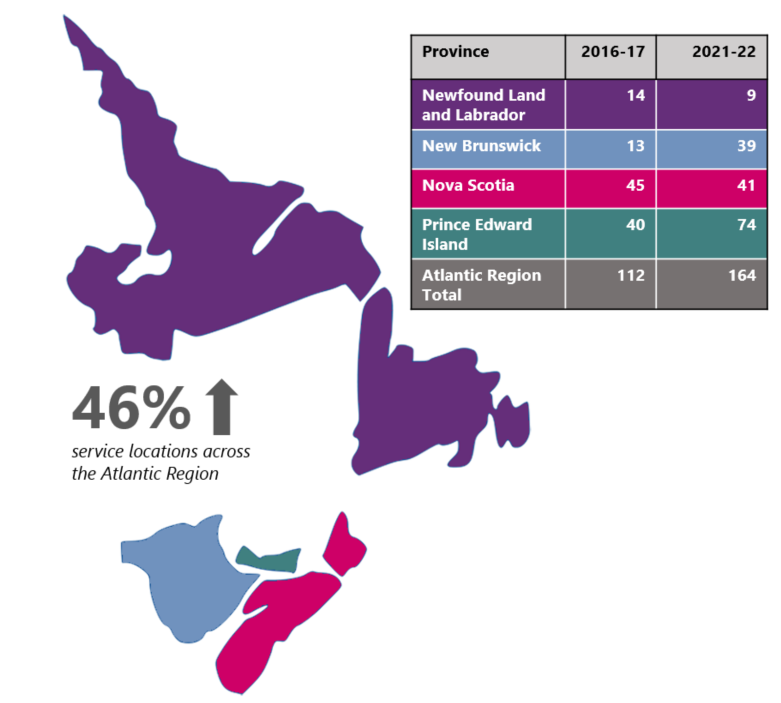

There was a 46% increase in the number of service locations in the Atlantic region by the end of the AIP, compared to a 12% increase nationally.

-

Text version

The diagram and chart show that service locations in the Atlantic region increased by 46% overall.

New Brunswick: In 2016-17 there were 13 locations. In 2021-22 there were 39 locations.

Nova Scotia: In 2016-17 there were 45 locations. In 2021-22 there were 41 locations.

Prince Edward Island: In 2016-17 there were 40 locations. In 2021-22 there were 74 locations.

Atlantic Region Total: In 2016-17 there were 112 locations. In 2021-22 there were 164 locations.

In fact, there is a trend of considerably higher settlement service usage in the Atlantic region. The inflows of immigration to the area, the emphasis on settlement, and service expansion from IRCC programming may have contributed to this uptick across all immigration categories

Total settlement clients in the Atlantic region increased by more than 50% in the last 5 years.

-

Text version

The line chart shows subsequent increases of settlement clients in the Atlantic region. The series displayed represent each Atlantic province: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland & Labrador. There is an uptick in 2016-17 during the launch of AIP (14,601 total clients). There is another a moderate downtick in 2019-20 at the outset of COVID-19 pandemic (22,089 total clients). There is another final uptick in 2021-22 when the AIP became permanent (22,565 total clients).

Finally, another reason for the comparably similar uptake rates between newcomers arriving through PBI pathways and other economic pathways, could be because AIP and RNIP newcomers were leveraging other supports available to them. The abovementioned analysis on service uptake is focused on IRCC-funded settlement service providers because that is how the Settlement Program is traditionally measured. However, the RNIP and AIP were testing new ways of delivering settlement services explored further in the following section.

Flagship settlement service offerings

To begin, both RNIP and AIP newcomers could access settlement services from non-traditional providers. Settlement service provision by communities/employers is a new feature in these pilots. For AIP, employers were the top service providers indicated by survey respondents in the AIP Evaluation. For RNIP, most survey respondents received services from a combination of providers that typically included employers and SPOs. In fact, RNIP focus group participants noted that one of the reasons they did not access some IRCC-funded settlement services was because they felt sufficiently supported by their employers.

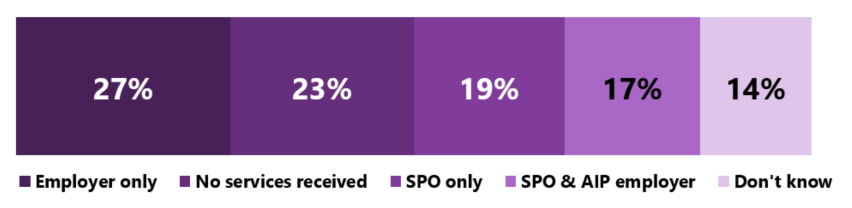

The top provider of services for AIP survey respondents was their employer.

-

Text version

This stacked bar chart shows that employers were the most popular service provider indicated by AIP Survey respondents. 27% indicated they only received supports from employer. 23% indicated they received no services. 19% indicated they received SPO only services. 17% indicated they received supports from a SPO and AIP employer. 14% indicated they didn’t know if they received services.

Most RNIP survey respondents received supports from a combination of providers.

-

Text version

This stacked bar chart shows that RNIP survey respondents received supports from a combination of providers. 43 % indicated they received supports from a combination of providers. 23% indicated they received no services. 17% indicated they received SPO only services. 12% indicated they received employer only supports. 5% indicated they received EDO only supports.

However, the top services that these newcomers accessed from employers were somewhat different than traditional service providers. While Information and Orientation was a top service for both employers and SPOs, there were other notable differences – namely employers focused on housing and transportation supports while SPOs focused on community connections and language supports. These results were consistent across employer and newcomer surveys in both the AIP evaluation and recent RNIP Surveys. This may indicate that the supports offered by employers complement or enhance the services offered by traditional settlement service providers.

Top services provided by employers and SPOs differed for RNIP and AIP newcomers.

-

Text version

This diagram shows the top services provided by different providers.

Top Employer Services: Housing supports, Transportation assistance, Information & Orientation

Top SPO Services: Information & Orientation, Community Connections, Language assessment/ Training

Beyond the provision of services by employers, these pilots had other flagship settlement features. For AIP, newcomers were required to receive a mandatory settlement plan. According to the AIP Evaluation, a large majority of surveyed newcomers found the plans to be helpful in identifying family needs, recommending useful information, connecting them with settlement services, and supporting their settlement in Canada. However, interviews and focus groups on the topic revealed the settlement plans were seen as a formality and not useful for some. This was especially true for newcomers who had previous experience living in Canada as temporary residents.

Finally, RNIP also had a volunteer matching initiative that paired RNIP newcomers with established members of the community or workplace for orientation and support. All communities were expected to offer connections between newcomers and volunteers, but it was the newcomers’ decision to accept this invitation. About half (55%) of RNIP Survey respondents indicated that they were offered to be matched with a volunteer by a SPO, EDO, or employer. RNIP focus group participants noted that they declined a volunteer match because they were already members of the community (former temporary residents) while others were not aware of this offering. Focus group participants strongly suggested that volunteer matching would have been helpful for newcomers who did not previously live in the community.

Overall, settlement service usage of RNIP and AIP newcomers is comparable to other economic categories with the exception of some noteworthy features (e.g. complementary services from employers, volunteer matching). However, service usage is only important insofar as newcomers achieve their expected outcomes.

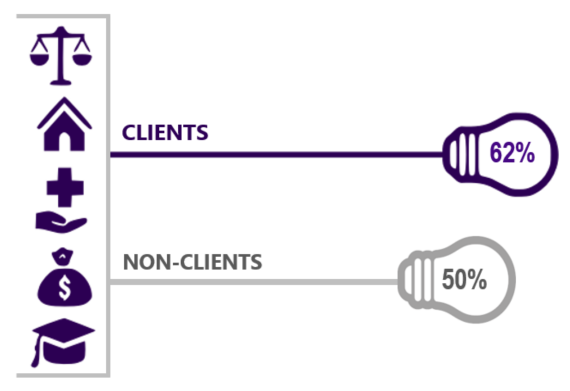

Settlement Program outcomes

Settlement program outcomes are measured using the annual Newcomer Outcomes Survey (NOS). This survey supports comparisons of the self-reported outcomes of newcomers who used settlement services (clients) to those who did not (non-clients). To better understand settlement outcomes using a place-based approach, the first step is to assess self-reported outcomes of any newcomer who landed in a PBI destination (i.e. Atlantic provinces, or the 11 RNIP communities). This analysis focuses on the “knowledge of life in Canada” outcomes for two reasons. First, Information and Orientation services was the top service accessed by both AIP and RNIP newcomers. Secondly, and perhaps more broadly, this knowledge enables newcomers to make informed decisions along their settlement journey. Focusing on this outcome of interest, the data show that more Settlement Program clients reported improved knowledge compared to non-clients in both the RNIP communities and the Atlantic provinces. This suggests that IRCC-funded services helped clients in these destinations improve their knowledge of life in Canada.

More settlement clients in the Atlantic region reported improved knowledge than non-clients.

Admission Data Range: 2013-2020

-

Text version

This lollipop bar chart shows that 62% of Atlantic clients increased their knowledge whereas 50% of Atlantic non-clients increased their knowledge.

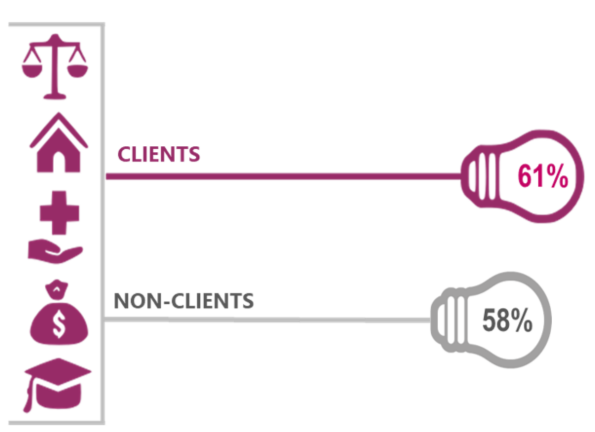

More settlement clients in the RNIP communities reported improved knowledge than non-clients.

Admission Data Range: 2013-2020

-

Text version

This lollipop bar chart shows that 61% of clients in RNIP communities increased their knowledge whereas 58% of non-clients in RNIP communities increased their knowledge.

To be clear, this is assessing all clients and non-clients who lived in these destinations regardless of their pathway. This is an important first step to determine if the emphasis on providing extra settlement supports in the PBI initiatives is supported by better outcomes – which they appear to be. The next step is to compare the self-reported outcomes of newcomers who entered through PBI pathways to a comparable group such as newcomers from the Provincial Nominee Program. Unfortunately, it is too early to do this comparative analysis for RNIP newcomers, but it can be done for the AIP.Footnote 19

Given the extra emphasis of wrap-around settlement supports in these initiatives, it would be reasonable to expect that knowledge outcomes would be greater for AIP clients compared to PNP clients. However, for the Atlantic region, the opposite is true. More PNP clients had knowledge gains than non-clients – suggesting that IRCC-funded settlement services may have contributed to better outcomes for PNP clients but not AIP. In fact, the results were relatively similar for AIP clients and non-clients, with the latter having marginally better gains.

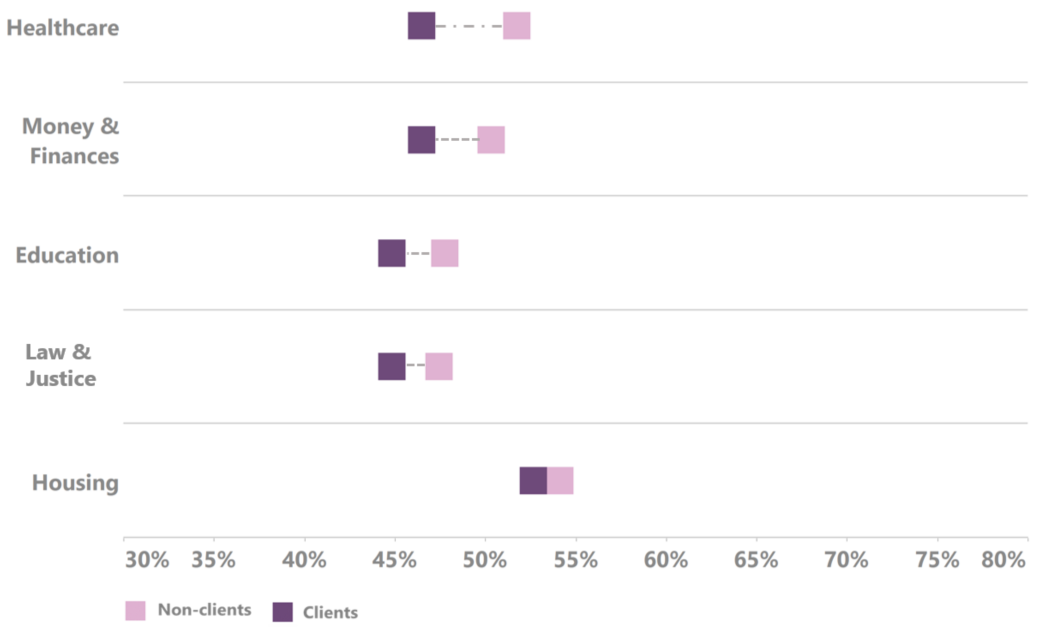

Slightly more AIP non-clients improved their knowledge of life in Canada compared to AIP clients. Conversely, considerably more PNP clients improved their knowledge than PNP non-clients.

% of Atlantic Immigration Pilot clients vs non-clients that improved their outcomes

Admission data range: 2017- 2020

-

Text version

This dumbbell chart shows that slightly more AIP non-clients improved their knowledge of healthcare, money & finances, education, law &justice, and housing compared to AIP clients. The difference between clients and non-clients are small, with a range between 1 and 5%.

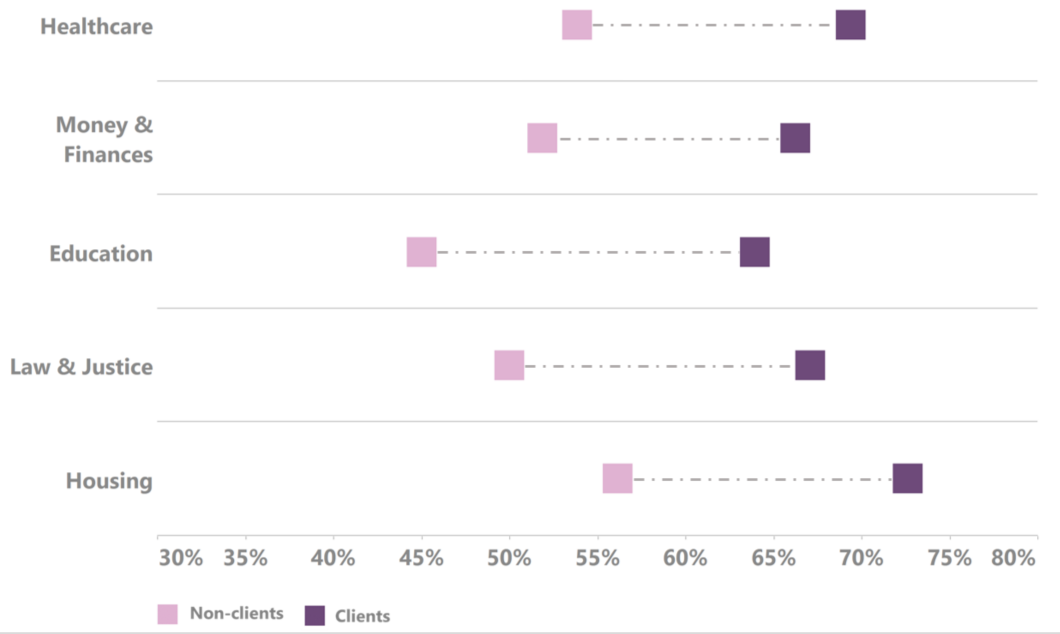

% of Provincial Nominee Program clients vs non-clients that improved their outcomes

Admission data range: 2017- 2020

-

Text version

This dumbbell chart shows that considerably more Atlantic PNP clients improved their knowledge of healthcare, money & finances, education, law &justice, and housing compared to Atlantic PNP non-clients. The difference between client and non-client are large, with a range of 14-19%.

There are different possible reasons for these results that merit further exploration. First, the typical assessment of clients vs non-clients assumes that non-clients do not access comparable settlement services. For AIP, this assumption does not hold true. AIP newcomers were offered settlement supports from different providers – including employers which are not captured in the data. It is very possible that the non-clients in this assessment are AIP newcomers who accessed comparable settlement supports from their employers. In fact, the AIP Evaluation found that the employer was the top cited settlement service provider. Therefore the client and non-client results are potentially very similar because both are receiving comparable settlement services. This result as well as this potential reasoning merits further exploration.

Unfortunately, it is too early to compare the knowledge outcomes of RNIP clients to other comparable settlement clients.Footnote 20 A future report or evaluation may examine those results once the data become available. That said, it’s increasingly clear that IRCC-funded settlement services are only part of the story in supporting newcomers to settle and integrate through place-based initiatives. Local partners and the broader community also play a significant role.

Community contributions

Settlement and integration is sometimes referred to as a “two-way street.” This means that the process of settling and integrating is not simply the responsibility of the newcomer but also the responsibility of the destined community to grow and evolve as it absorbs new members from diverse backgrounds.Footnote 21 This is especially true for PBI initiatives, where newcomers are arriving in destinations that have historically not attracted nor retained newcomers. As such, this final section focuses on how communities are welcoming and supporting immigrants arriving through PBI pathways, and the impact that it might have on the newcomers’ journeys.

Community initiatives

Both the AIP and RNIP pilots required local actors to play a stronger role in newcomer settlement, integration and retention. The provision of services by employers and local Economic Development Organizations (EDOs) is an example of how the communities are actively involved in supporting newcomers. In addition, the mandatory settlement plans in the AIP, and the volunteer-matching initiative in the RNIP also demonstrate the additional measures these communities have implemented to help support newcomers. Finally, RNIP recommendation committees are formed by community stakeholders and serve as a coordination and/or mobilization tool.

Beyond the settlement supports that are being offered, there are other community-level initiatives that are worth noting. These initiatives focus on creating welcoming and inclusive environments for immigrants. For example, the West Kootenay and North Okanagan Shuswap local RNIP organizations have published a series of success stories aimed at highlighting the benefits of immigration and diversity. The Pembina Valley Local Immigration Partnership, that covers the Altona area, has also published a guide and toolkit to increase community cultural competency. Some RNIP and AIP employers have also received referrals or participated in diversity and intercultural competency training. It is also worth noting that Local Immigration Partnerships and Welcoming Francophone Communities exist in several of these communities. They work on improving the successful integration of immigrants by convening partners from across key sectors in a city or region. Ultimately this is snapshot of some initiatives, but there are many more aimed at creating welcoming and inclusive environments for newcomers.

Experiences of discrimination

The abovementioned community initiatives are particularly important as a way to address potential discrimination that newcomers may face. The literature points to discrimination as a potential barrier to newcomers’ settlement and integration in small and rural communities.Footnote 22 In fact, one of the reasons newcomers choose to settle in large urban centers is because of the presence of existing ethnic communities which may reduce their concerns around experiencing discrimination or hardship.Footnote 23 The lack of ethnic or racial diversity in smaller or rural communities can be a strong deterrent for newcomers. Some may dismiss concerns in favour of the perceived benefits of settling in those communities (e.g. employment opportunities, affordable housing) while others may be dissuaded from immigrating to a small or rural community altogether.Footnote 24 To better understand these different experiences, in 2022 IRCC conducted an online survey of newcomers to Canada about their experiences of discrimination in their city or town. Overall, a majority of the 27,307 respondents said they lived in a welcoming city or town and reported a strong sense of belonging. However, when looking more specifically at their experiences of discrimination, approximately 60% of respondents across Canada experienced some form of discrimination.Footnote 25 Newcomers who resided in an RNIP or AIP destination reported similar experiences and similar forms of discrimination.

Based on the literature, it might be anticipated that more newcomers in smaller communities would report experiences of discrimination. However, these results paint a different picture. Newcomers in Canada, including in larger centres, are having similar experiences to newcomers in PBI destinations. Notably, these findings are not pathway specific – meaning that all newcomers were surveyed regardless of the program they used to immigrate to Canada. To focus specifically on the experiences of discrimination for newcomers arriving through PBI pathways, the recent RNIP Newcomer Survey of 276 respondents can provide more insight.Footnote 26

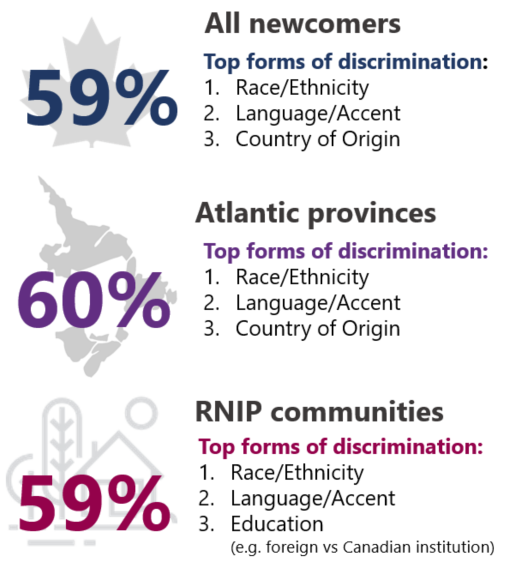

6/10 of newcomers across immigration pathways experienced discrimination, including in RNIP and AIP destinations.

-

Text version

This diagram shows that 59% of all newcomers experienced discrimination, 60% of newcomers in the Atlantic provinces experienced discrimination and 59% of newcomers in RNIP communities experienced discrimination. The top forms of discrimination for all newcomers were: 1 – Race/Ethnicity; 2 – Language/accent; 3 – Country of Origin. The top forms of discrimination for newcomers in Atlantic provinces were: 1 – Race/Ethnicity; 2 – Language/accent; 3 – Country of Origin. The top forms of discrimination for newcomers in RNIP communities were: 1 – Race/Ethnicity; 2 – Language/accent; 3 – Education (e.g. foreign vs Canadian institutions).

Comparatively, fewer RNIP respondents (30%) had experienced discrimination. However, their experiences should not be overlooked as RNIP focus group participants reported experiencing overt incidences of racism while at work, shopping, or while using settlement services.

That being said, preliminary findings show similar experiences of discrimination (especially the top forms of discrimination – race/ethnicity, language/accent) between PBI destinations and newcomers across Canada. However, more research may be needed to better understand these findings.

Fewer newcomers immigrating through the RNIP pathway experienced discrimination.

-

Text version

This diagram shows that 3/10 RNIP newcomer respondents experienced discrimination. The top forms of discrimination indicated by RNIP newcomer respondents were: 1 – Race/Ethnicity; 2 – Language/accent; 3 – Immigration Status.

Exploring experiences of discrimination in Northern Ontario

A recent research series by the Northern Policy Institute examined racism and discrimination in Northern Ontario RNIP communities. The series focused on: Greater Sudbury, North Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, Thunder Bay, and Timmins. The research takes a place-based approach by focusing each report on a community. While each report had unique findings relevant to the community, the majority of the respondents across the series indicated that their communities were welcoming. However, an area of concern included individual prejudice experienced by visible minorities and Indigenous peoples. Notably, the experiences of white community members differed from visible minorities and Indigenous people, where the treatment of the latter was relatively more negative.

Sense of belonging

Sense of belonging is recognized as an important determinant of newcomers’ successful settlement and integration, as well as an indicator of well-being, social cohesion, and social capital.Footnote 27 Whether a newcomer feels socially connected to their new community is partly dependent on their community’s efforts to welcome them (i.e. the two-way street). This is particularly relevant for small, rural and northern communities which are eager to foster a welcoming environment to attract and retain immigrants.

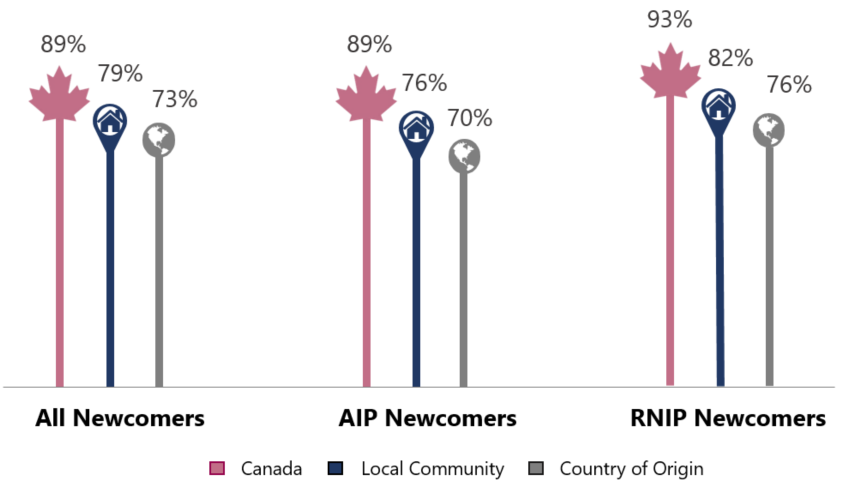

Despite previously discussed experiences of discrimination (that should not be overlooked), newcomers arriving through PBI pathways report a strong sense of belonging to Canada. Analysis of departmental surveys show that the vast majority of respondents coming from AIP and RNIP pathways report a strong sense of belonging to Canada and their local community.

This finding is consistent with previous research on immigrants’ sense of belonging across Canada. The literature points to several predictors of national belonging including: a younger age at immigration, more years of residence in Canada, and speaking English or French at home.Footnote 28 These are factors that are consistent with the newcomers recruited through AIP and RNIP (e.g. many former temporary residents, relatively younger than other economic categories). That being said, the actions of the community to make newcomers feel welcomed should not be ignored. For example, RNIP focus group participants described receiving a warm welcome individuals in community centers, recreational activities, churches, schools, and at work.

Notably, when comparing the sense of belonging of newcomers who accessed services and supports with those who did not – there is a difference. Respondents to the Survey of RNIP Newcomers who indicated they were matched with a volunteer mentor reported a stronger sense of belonging to their local community (88%) than those who did not get matched with a volunteer (75%). This was supported by focus group findings that highlighted the benefits of volunteers. Similarly, AIP settlement clients reported a slightly stronger sense of belonging. This stronger sense of belonging is more pronounced for clients arriving as PRs (80%) compared to their non-client PR counterparts (72%). This suggests that efforts to provide services and community-level supports for those who are newly arriving in a community makes a difference in helping them feel welcome.

Newcomers from PBI pathways report a strong sense of belonging to Canada and their local communities, similar to newcomers from other pathways.

-

Text version

This lollipop column chart shows that newcomers’ sense of belonging in RNIP and AIP is comparable to that of other newcomers.

All newcomers: 89% indicated a strong sense of belonging to Canada. 79% indicated a strong sense of belonging to their local community. 73% indicated a strong sense of belonging to their country of origin.

AIP newcomers: 89% indicated a strong sense of belonging to Canada. 76% indicated a strong sense of belonging to their local community. 70% indicated a strong sense of belonging to their country of origin.

RNIP Newcomers 93% indicated a strong sense of belonging to Canada. 82% indicated a strong sense of belonging to their local community. 76% indicated a strong sense of belonging to their country of origin.

Conclusion

Adopting a place-based approach to understanding regional immigration takes advantage of the unique efforts and aspects of each community. This is especially relevant when assessing regional immigration initiatives such as AIP and RNIP which are inherently place-based. Both pilots tested new ways to deliver settlement supports that draw on the distinct challenges and opportunities in their respective provinces and communities. Lessons learned from the AIP have already informed the permanent program, as well as the iterative design of the RNIP. The settlement implications examined in this report can be applied more broadly to help improve the Settlement Program.

Both RNIP and AIP demonstrated early positive results in the retention of newcomers in destinations that have typically struggled to attract and retain immigrants. Multiple factors could have contributed to this result including pre-admission work experience, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the support from multiple community actors. In fact, AIP and RNIP newcomers had access to a complement of services, supports, and providers. While uptake of traditional settlement services was comparably average for these populations, employers evidently played an important role in providing supports (e.g. housing, transportation) that complemented traditional offerings. Furthermore, settlement clients in the Atlantic region reported stronger knowledge gains than non-clients; however, these gains disappeared when focusing specifically on newcomers coming from the AIP pathway. This finding may be explained by accounting for how employer supports delivered through the AIP may have helped to improve non-client outcomes. Beyond employers, other local actors in the community have also made efforts to ensure that newcomers feel supported and welcomed. This is particularly important because newcomers in these destinations have reported similar forms of discrimination as newcomers across Canada (e.g. discrimination based on race/ethnicity, language/accent). Despite these challenging experiences, RNIP and AIP newcomers have also reported a very strong sense of belonging. This may be a result of the supports and services offered in the community (e.g. settlement services, volunteer matching) alongside other contributing factors.

In addition to these findings, some areas for future research were also identified. The following topics merit further investigation in a future study or evaluation:

- In-depth comparisons between the 11 RNIP communities, and between the Atlantic provinces (e.g. different approaches to pilot/program implementation)

- Assessment of longer term retention in RNIP communities

- Follow-up study to understand why AIP settlement clients and non-clients have similar settlement outcomes on “Knowledge of Life in Canada”

- Comparing settlement outcomes between RNIP and AIP newcomers who were former temporary residents vs those without pre-admission work experience in Canada

Furthermore there were some areas outside of the scope of this report including: immigrant selection, pilot administration, resource intensity, and program integrity. These are topics that are better explored in future evaluations. This is particularly relevant for the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot which will be formally evaluated at the end of the pilot period.

Ultimately, as regional immigration initiatives continue to evolve and adapt, these findings alongside future research will support efforts to better leverage local actors in newcomer settlement and integration.

Annex: Approaches to supporting RNIP newcomer integration

The 11 participating communities in the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot implemented the pilot differently (leveraging different local actors) depending on their context. The communities, (represented by the local Economic Development Organizations) committed to:

- Promote and champion the benefits of immigration to community partners including employers and residents, in order to foster a welcoming community and workplaces

- Support the retention of newcomers, in particular, helping them settle into the community by matching newcomers with established members of the community

- Facilitate the integration of newcomers by connecting them with available settlement services and facilitating newcomer access to key social services, including housing, education, transportation and health care

The following table provides a snapshot of how the communities differed in their implementation of these commitments.

-

Text version

This infographic shows the number of participating RNIP communities that delivered supporting activities under each of the community commitments.

Champion the Benefits of Immigration:

9/11 communities required employers to participate in diversity/intercultural competency training

9/11 communities conducted public awareness campaigns about immigration

Match Newcomers with Volunteers:

8/11 communities relied on the SPO to match newcomers with volunteers

5/11 communities relied on the employers to match principal applicants with on-the-job mentors

Connect Newcomers to Services:

8/11 communities provided welcome packages

6/11 communities coordinated airport pickups (either through the EDO or employer)

6/11 communities referred candidates to a local SPO for an individualized Settlement Plan

Data sources

This following contains information about primary data sources used in the report – i.e. data collected directly by IRCC. Many other sources of information were used in the development of this report. Secondary data sources (i.e. data collected or analysis done by other parties) are referenced directly in the report.

-

IRCC Permanent Resident Database

The IRCC Permanent Resident Database is based on the Global Case Management System (GCMS). GCMS is IRCC’s single, integrated and worldwide system used internally to process applications for citizenship and immigration services.

This report uses GCMS information about newcomers to Canada:

- who were admitted as permanent residents between 2013 and 2020, or

- who used settlement services in 2020-21 and 2021-22.

The data were extracted between December 2022 and June 2023.

-

iCARE

The Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE) is a data entry system that collects key characteristics of services used by clients of the Settlement and Resettlement Programs, including Pre-Arrival. The data is entered by Service Provider Organizations (SPOs) and they are required to report monthly as per their Contribution Agreement with IRCC. iCARE has been used to collect Settlement Program data since 2013 and Resettlement Program data since 2014.

This report uses iCARE information about settlement services used in 2020-21 and 2021-22.

The data were extracted between December 2022 and June 2023.

-

Grants and Contributions System (GCS)

The Grants and Contributions System (GCS) is an online tool that allows Service Provider Organizations (SPOs) to submit applications for funding, as well as manage Grants or Contribution Agreements.

This report uses GCS information about Contribution Agreement funding and reporting for 2020-21 and 2021-22.

The data were extracted March 2023.

-

SAP

SAP is the Department’s financial management system used to support the preparation of financial statements and other reporting.

This report uses SAP information about settlement program expenditures in 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22.

The data were extracted March 2023.

-

Newcomer Outcomes Survey (NOS)

The Newcomer Outcomes Survey (NOS) is an annual survey of newcomers to Canada that collects settlement outcomes information from both clients and non-clients of IRCC’s Settlement Program. Each year, the survey is sent to all newcomers who became permanent residents in specific years. Two years of survey data are combined to provide a response set from newcomers across eight admission years.

This report uses NOS responses to the 2020 and 2021 survey waves about the settlement experiences of newcomers who became permanent residents between 2013 and 2020.

The data were extracted March 2022.

-

ARPIO / APRCP

SPOs delivering direct settlement services provide an Annual Report on Project Implementation & Outcomes (ARPIO) and Local Immigration Partnerships/Réseaux d’immigration francophone provide an Annual Project Report on Community Partnerships (APRCP). The reports provide an equitable opportunity to hear from SPOs across the country on similar issues. Note that the ARPIO was formerly called the APPR – Annual Project Performance Report.

This report uses ARPIO and APRCP reports about Contribution Agreements funded for 2017-18, 2018-19, 2020-21 and 2021-22.

The data were extracted after the end of the reporting cycles.

-

2020 Remote Service Delivery Survey

IRCC conducted a Remote Service Delivery Survey of Service Provider Organizations (SPOs) in November 2020 to better understand what the delivery of direct settlement services looked like in the COVID-19 context for SPOs receiving IRCC funding.

This report uses survey information about the impact of the transition from in-person to remote service delivery.

The data were extracted January 2021.

-

2022 Digital Case Study Client Survey

IRCC conducted an online survey of client experiences using online settlement services in August 2022, to better understand which settlement services were working well, and what needed improvement.

This report uses survey information about client experiences using settlement services prior to August 2022.

The data were extracted April 2023.

-

2022 Digital Case Study Client Focus Groups

IRCC conducted focus groups with clients who had accessed settlement services, to better understand what types of settlement services should be offered online, for which clients, and how to ensure that online services work well for clients.

This report uses focus group information about newcomer client views and experiences regarding online settlement services.

The focus groups were held May 2022.

-

2022 Digital Case Study Service Provider Focus Groups

IRCC conducted focus groups with staff from Service Provider Organizations (SPOs), to better understand in what contexts Settlement Program services should be offered online, for which clients, and how online services can be offered in a responsive, effective, and efficient way.

This report uses focus group information about views and experiences on the delivery of online settlement services.

The focus groups were held May 2022.

-

2022 RNIP Newcomer Survey

IRCC conducted an online survey of newcomers’ experiences participating in the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot in October 2022, to better understand how the pilot is working, and what needs improvement.

This report uses survey information about RNIP newcomers’ use of services and supports, experiences of discrimination, sense of belonging, and desire to stay in the RNIP communities where they settled.

The data were extracted February 2023.

-

2022 RNIP Employer Survey

IRCC conducted an online survey of employers participating in the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot in August 2022, to better understand how the pilot is working for employers, and what needs improvement.

This report uses survey information about the settlement supports provided by RNIP employers to support their candidates.

The data were extracted December 2022.

-

2022 RNIP Client Focus Groups

IRCC conducted focus groups with newcomers who had responded to the RNIP Newcomer Survey, and expressed a willingness to participate in focus group discussion, to contextualize survey responses and obtain further insights into RNIP newcomers’ experiences using settlement supports.

This report uses focus group information about experiences with volunteer matching, use of settlement services, and experiences within the community.

The focus groups were held February 2023.

-

2022 IRCC Survey: Newcomers’ experiences of discrimination in their city or town

IRCC conducted an online survey of newcomers in February 2022 to better understand experiences of discrimination in their city or town. The results of the survey will help IRCC inform its services and awareness campaigns going forward, and to meet the needs of newcomers to Canada.

This report uses survey information about experiences of discrimination in newcomers’ city or town, including the type of discrimination experienced.

The data were extracted April 2023.