The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2014 – Public health in a changing climate

Public Health in a Changing Climate

Highlights

- The impacts of changing climate are already evident in Canada and projected to continue.

- Climate change can exacerbate many existing health concerns and present new risks to the health of Canadians.

- Adaptive capacity in Canada is generally high but is unevenly distributed between and within regions and populations.

- Public health action is needed to reduce vulnerability and risks.

- Some adaptation is taking place in Canada, both in response to and in anticipation of the impacts of climate change.

The global climate is changing and Canada, like many other countries, is vulnerable.Footnote 152-154 Changes in climate are expected to increase risks to health in many ways, including through more extreme weather events and the associated impacts on community infrastructure, decreased air quality and diseases transmitted by insects, food and water.Footnote 152-155 Although efforts are underway to protect the health of Canadians, continued action will be needed as climate changes.Footnote 153,Footnote 154,Footnote 156

This section includes:

- a brief overview of how the climate is changing;

- a discussion on how changes in climate are influencing the health of Canadians; and

- a consideration of broad public health measures that can be taken to prepare for and adapt to climate change.

A changing climate

In simplest terms, the difference between weather and climate is a measure of time. Weather refers to the atmospheric conditions — the sunshine, cloud cover, winds, rain, snow and excessive heat—of a specific place over a short period of time. Climate refers to the average atmospheric conditions that occur over long periods of time. In other words, a changing climate refers to changes in long-term averages of daily weather (e.g. precipitation, temperature, humidity, sunshine, wind velocity and other measures of weather).Footnote 152,Footnote 155

The global climate has changed considerably over the past century, and notably so over the last 30 years.Footnote 157-159 This is evidenced by changes in average climate conditions and in climate variability as well as extreme climate events across the globe.Footnote 154,Footnote 157,Footnote 159

Many of the changes observed globally include warming of the oceans and surface temperatures, melting ice and snow in seas and lakes, rising sea levels and coastal erosion.Footnote 157,Footnote 159,Footnote 160 In turn, research indicates that these environmental changes are altering precipitation patterns and increasing the potential for more severe and frequent extreme weather conditions (i.e. periods of excessive warmth or cold, wetness or dryness) resulting in hazardous events such as heat waves, ice storms, droughts, floods, hurricanes, wildfires, landslides and avalanches.Footnote 154,Footnote 157,Footnote 159 The story does not end here: climate models project continued changes in climate conditions across the globe.Footnote 159,Footnote 161

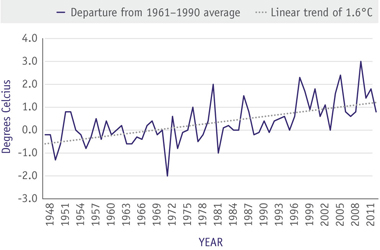

Figure 3 Annual national temperature departures and long-term trend, Canada, 1948 to 2013Footnote 162

Text Equivalent - Figure 3

Annual temperatures have fluctuated from year to year over the period 1948–2013. The annual temperatures have warmed by 1.6°C over the past 66 years.

Canada is no exception to these changes.Footnote 153-155 The annual average temperatures across Canada have increased by 1.6 degrees Celsius over the past 66 years (see Figure 3).Footnote 162 The impacts of environmental change are particularly visible in Canada's North: winters are shorter and summers are warmer resulting in changes to ice conditions affecting hunting and fishing, the distribution and migratory behaviour of some wildlife species are being altered and more frequent forest fires.Footnote 153-155,Footnote 160,Footnote 163-167

Climate risks to health: now and in the future

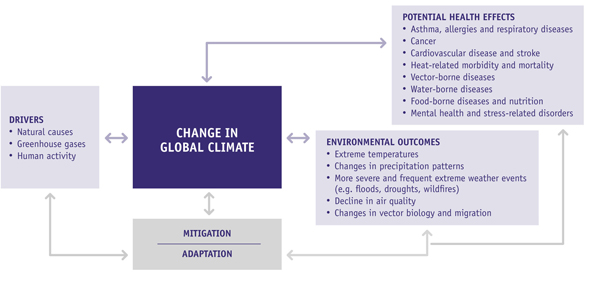

Changes in climate can potentially have widespread direct and indirect effects on people's physical, social and mental health and well-being.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168-170 In particular, climate change can influence extreme heat-related morbidity and mortality; health conditions such as asthma and allergies, respiratory diseases, cancer and cardiovascular diseases and stroke associated with decreased air quality; infectious diseases related to changes in vector biology and migration and water and food contamination; and mental health and stress-related disorders (see Figure 4).Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168 Extreme weather events can also impact critical community infrastructure, in turn, adversely affecting overall health and well-being.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168 The burden of these health issues is anticipated to increase as the changes in climate advance in the absence of further adaptations.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168

Figure 4 Pathways by which changes in climate can increase risks to healthFootnote 155,Footnote 168

Adapted from Portier, C.J. et al. (2010).

Text Equivalent - Figure 4

Illustrates pathways by which changes in climate can influence health and well-being. A number of identified drivers (e.g. natural causes, greenhouse gases and human activities) affect global climate resulting in changing environment outcomes such as extreme temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, more severe and frequent extreme weather events, decline in air quality and changes in vector biology and migration. Changes in climate can increase potential risks to human health. Some potential health effects include respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, heat-related morbidity and mortality, vector-, water-, and food-borne diseases, and mental health and stress-related disorders. Mitigation and adaptation strategies are needed to reduce the associated impacts on health and well-being.

Any climatic effect on health can be more severe when sensitivities and vulnerabilities are present. The very young and the very old as well as those with underlying health conditions may experience greater climate-related health risks than the general population.Footnote 154,Footnote 155 Broader determinants of health such as age, socioeconomic conditions, housing and community infrastructure, geographic location and access to support and social services can contribute to increased sensitivities and vulnerabilities.Footnote 124,Footnote 155,Footnote 171 Ensuring that basic needs are met will be important for people and communities to adapt to changes in the environment.

The following brief overview describes some of the potential health effects of increased temperatures, changes in precipitation and extreme weather events. These sections are not comprehensive assessments of the risks from climate change on health. Rather, they are meant to encourage broad discussions about some of the health issues that may potentially warrant further public health consideration.

Heat-related morbidity and mortality

Projected increases in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events such as heat waves, ice storms, floods, wildfires, landslides, avalanches and hurricanes may increase the risk of weather-related illnesses, injuries, disability and death.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155 The impact on health will vary based on the severity of the extreme weather event and the level of preparedness of communities and individuals. Given the unpredictability of such events, emergency management and response efforts and critical infrastructures play a role in the degree that these events can affect health.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 172

Extreme heat events are posing a growing public health risk in Canada.Footnote 152,Footnote 155,Footnote 173-176 Over-exposure to extreme heat can place excessive stress on the body. Such stress can lead to skin rashes, heat cramps, loss of consciousness and heat exhaustion. It can also cause heat stroke that may result in severe and long-lasting health consequences and death. Heat can also exacerbate pre-existing chronic respiratory, cerebral and cardiovascular conditions and affect mental health and well-being.Footnote 155,Footnote 168,Footnote 174,Footnote 176-180 Canadian and international research indicates that daily mortality rates can increase when temperatures rise above 25 degrees Celsius.Footnote 174,Footnote 181,Footnote 182

A range of factors can influence vulnerability to heat-related health risks.Footnote 152,Footnote 154 Age, housing and access to cool spaces and air conditioning, social isolation, neighbourhood characteristics, and the use of certain medications can increase risks associated with extreme heat.Footnote 174,Footnote 180,Footnote 183 Extreme heat is of greater concern to seniors, infants and children, and those with underlying health issues.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 174,Footnote 180

As the number of Canadians living in urban centres increases, heat-related health risks may increase even more.Footnote 174 The urban built environment has the potential to exacerbate the effects of heat.Footnote 174 For example, high concentrations of non-reflective surfaces such as buildings, roadways and parking lots can generate, absorb and slowly release heat resulting in urban centres being several degrees warmer than surrounding areas. Expanding parks and green spaces and increasing the density of trees in and around cities can help to reduce this effect.Footnote 174,Footnote 184

Health conditions influenced by poor air quality

Air pollution episodes in Canada are projected to get longer and more severe with climate change.Footnote 185 Certain aspects of air quality — in particular ground-level ozone concentrations and airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5) — can impact health.Footnote 185-187 In addition, pollen (due to altered growing seasons), mould (from flooding), dust (because of droughts) and smoke (from wildfires and wood smoke) resulting from changes in climate can also impact health.Footnote 155,Footnote 168,Footnote 188-190 Air pollution can exacerbate health concerns if also combined with extreme heat.Footnote 191

Broadly, exposure to poor outdoor air quality has been associated with a number of adverse health concerns including allergies, respiratory (e.g. asthma, lung damage) and cardiovascular diseases (cardiac dysrhythmias) and cancer.Footnote 192-198 Negative health effects can increase as air quality decreases. Studies have shown that it can exacerbate pre-existing health conditions and contribute to increased rates of emergency room visits, hospital admissions and premature death.Footnote 185-187,Footnote 192,Footnote 193,Footnote 196,Footnote 199 Reaction to air pollution differs with each person. Those most sensitive to health risks associated with poor air quality include children, pregnant women, seniors, people living with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and those living in highly populated areas that are more likely to experience episodes of elevated poor air quality.Footnote 154,Footnote 185-187,Footnote 196

Vector-borne diseases

Recent studies on vector-borne diseases show that climate trends can influence disease transmission by shifting the geographic range and seasonality of vectors, increasing reproduction rates and shortening the incubation period of pathogens.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 200-202 Changing climate conditions may also heighten the risk of exposure to vector-borne diseases as habitats expand and become better able to support the vectors.Footnote 200-203 As a result, Canada may experience the emergence of diseases that are currently rare (see the textbox "Lyme disease: an emerging infectious disease in Canada").Footnote 203-210

Lyme disease: an emerging infectious disease in Canada

Climate change has contributed to the emergence of Lyme disease in northeastern United States and in most southern areas of Canada including parts of British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and can potentially affect the spread of the disease into new geographic regions.Footnote 207-209,Footnote 211 Lyme disease can cause skin rash, arthritis, nervous system disorders and in extreme cases, debilitation and death.Footnote 212 It is caused by a bacterium transmitted by infected ticks (most commonly black-legged, or deer tick, Ixodes scapularis). Warmer temperatures can accelerate tick life cycles, create more favourable conditions for survival and for finding hosts, and increase the risk that new tick populations will become established in new parts of Canada.Footnote 205,Footnote 206,Footnote 208-210,Footnote 213

West Nile virus (WNv), a mosquito-borne illness, is another good example of the relationship between climate and disease migration. First documented in Canadian birds in 2001, WNv has since spread rapidly and is now found in most of the country.Footnote 155,Footnote 214,Footnote 215 The first human case of WNv was reported in 2002. Since then, more than 5,454 cases of human WNv disease have been reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada with cases concentrated in a number of urban and semi-urban areas of southern Quebec and southern Ontario, rural and semi-urban areas of British Columbia and in rural populations in the Prairies.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 204,Footnote 215,Footnote 216 Changes in climate can shorten the life cycle of the mosquito, accelerate its rate of reproduction, expand its geographic range and lengthen the overall transmission season.Footnote 213,Footnote 216-218 While most of those infected have no symptoms or mild flu-like symptoms from which they fully recover, WNv can cause severe illness, including meningitis and encephalitis and its long-term effects are not fully understood.Footnote 219,Footnote 220

Food- and water-borne diseases

The potential effects of climate trends on food- and water-borne illnesses, nutrition and food security, while mostly indirect, can nonetheless, significantly impact health.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168,Footnote 221,Footnote 222 Food-borne illnesses tend to peak during warmer summer months, illustrating a strong seasonal pattern. This can, in part, be attributed to changes in food consumption and preparation practices that can increase risk of food spoilage and food-borne diseases. However, some of this seasonal increase can be associated with increased temperature. Warmer weather can allow bacteria to grow more readily in food and can favour flies and other pests that affect food safety. The occurrence of Salmonella, Campylobacter and E. coli infections in Canada has been linked to increased temperature. Research in Australia and the United Kingdom has found similar findings.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 222-229

Food security can also be influenced by changes in climate.Footnote 154,Footnote 221,Footnote 230 Extreme weather events such as flooding, drought and wildfires can affect food systems by impacting crop production, food availability, markets and related costs. Changes in rainfall can lead to drought or flooding, or warmer or cooler temperatures can affect the length of the growing season.Footnote 154,Footnote 221,Footnote 231-233 Being food insecure can lead to poor nutrition and thus an increased risk of unhealthy weight and having chronic health conditions and mental illness.Footnote 234 This is of particular concern for remote and northern communities in Canada.Footnote 153-155,Footnote 164,Footnote 235-239 Changes in climate can affect the distribution and availability (through fishing and hunting) of some of the traditional food sources that contribute to the diet of most northern Canadians. Unpredictable ice and weather conditions can restrict access to some foods. Changes in distribution and availability also affect aspects of Aboriginal peoples' cultural and social identity.Footnote 153-155,Footnote 165-167,Footnote 240-243 The availability of safe drinking water and the risk of water-borne infections is a particular concern in remote and northern communities.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 167,Footnote 244

Extreme weather and climate conditions have also been linked to a number of reported water-borne disease outbreaks in Canada.Footnote 155,Footnote 245-247 Frequent and intense rainfall can increase the risk of water contamination. Extreme rainfall can also threaten fisheries through contamination with metals, chemicals and other toxicants that are released into the environment.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168 Most commonly, storm water run-off flushes contaminants into waterways and shallow groundwater sources.Footnote 155,Footnote 245,Footnote 248 If combined with poor water management systems or aging or compromised water utility infrastructures (e.g. treatment facilities, distribution systems), the risk of exposure to water-borne diseases may increase.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 245,Footnote 248 The public health implications of drinking-water contamination in Walkerton, Ontario, in 2000 is a good illustration. Heavy rainfall, combined with ineffective drinking-water management systems and operating practices, resulted in more than 2,300 cases of illness and 7 deaths after drinking water became contaminated with E. coli O157:H7 and Campylobacter jejuni.Footnote 249

Conversely, drought-caused decreases in water levels can concentrate contaminants in water.Footnote 155,Footnote 168,Footnote 188,Footnote 250,Footnote 251 Similarly, higher temperatures can affect the growth and survival of bacteria, overwhelming water treatment plants, particularly older water systems.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155 Droughts can also increase demand and pressure on water supplies.Footnote 154,Footnote 155 For good health, Canadians require access to safe, secure drinking water supplies.

Mental health and stress-related disorders

Changes in climate and the subsequent disruption to the social, economic and environmental determinants of health can influence an individual's mental health and well-being. Extreme weather events can lead to geographic displacement of populations, damage or loss of property and injury and/or death of loved ones.Footnote 152-155,Footnote 252-257 These circumstances can, in turn, lead to acute traumatic stress and chronic mental illness, such as anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, sleep difficulties, social avoidance, irritability and drug or alcohol abuse.Footnote 155,Footnote 168,Footnote 252,Footnote 256-259 People already vulnerable to poor mental health, mental illness and stress-related disorders may be at an increased risk of exacerbated effects.Footnote 154,Footnote 155

Mental health in rural and remote northern communities and the influence of changes in climate is of particular concern.Footnote 169,Footnote 255,Footnote 260-262 The Inuit Mental Health Adaptation to Climate Change (IMHACC) project, a community-based initiative that examined the relationship between climate change and mental health and well-being in five communities in Nunatsiavut, Labrador, found that disruption in land-based activities due to changes in weather, snowfall and ice stability, and wildlife and vegetation patterns are affecting the way of life, cultural identity and social connectedness of Inuit communities.Footnote 263 These societal changes are negatively influencing Inuit people's mental health.Footnote 260-264

The severity of mental health impacts following extreme weather events can depend on the level of coping and the availability of support services during and after the event.Footnote 155,Footnote 168,Footnote 255 Rural and remote northern communities tend to have limited resources and insufficient support services.Footnote 155

Other indirect exposures and health effects

Significant indirect impacts on health as a result of climate change can occur through the effects on physical infrastructures (e.g. roads, storm water and flood control systems, houses and buildings) within communities.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 265 Changes in climate, particularly severe and frequent extreme weather events, can undermine or compromise systems and infrastructures and thus increase risks to health and safety.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 168 Infrastructure in northern communities is also particularly vulnerable to changes in temperature and precipitation patterns.Footnote 164,Footnote 266 Existing chronic health conditions can also be potentially exacerbated when critical infrastructure has been weakened or overloaded.Footnote 155,Footnote 168

Moving forward: addressing climate change health risks and vulnerabilities

As changes in climate have become more evident, so has the need for public health to anticipate, manage and respond to the effects these changes pose.Footnote 155,Footnote 156 However, addressing these health impacts is challenging. The issues are broad and complex.Footnote 154-156 Public health must strive to prevent and adapt to current as well as anticipated and unforeseen threats and identify the most vulnerable populations.Footnote 154

Responses to climate change can draw upon existing, core, long-standing public health functions such as research, education and awareness, surveillance and monitoring, and emergency planning. Protecting Canadians from climate change will, to a great extent, not entail the development of new programs. Rather, it will require modifying and strengthening existing public health policies and practices to make them more effective and to target particularly vulnerable populations.Footnote 152,Footnote 155 Responding to the public health challenges posed by changes in climate also requires a multijurisdictional, multidisciplinary and integrated response. Strengthening existing relationships and fostering new partnerships among all levels of government, academia, non-governmental organizations, communities and individuals should be the focus.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 267

The broad strategies discussed below—by no means a comprehensive list—illustrate the range of different possible adaptation strategies.

Mitigation and adaptation

Strategies for mitigating and adapting to changes in climate can help protect the environment and minimize or avoid certain adverse health effects now and for future generations.Footnote 152-156 Mitigation refers primarily to actions taken to slow, stabilize or reverse the effects of climate change by reducing greenhouse gases.Footnote 268 Adaptation refers to the actions taken to anticipate, prepare and lessen those effects of climate change that cannot be prevented through mitigation. While mitigation efforts will primarily occur in other sectors, public health has a definite role to play in informing Canadians about research on health-related impacts and implementing effective adaptation measures to reduce risks to health.Footnote 152-156

Building capacity as an adaptation to climate change

The capacity of individuals and communities to cope and adapt to current and anticipated changes in climate can significantly influence the degree to which these changes will impact their health.Footnote 155,Footnote 156 Adaptive capacity in Canada is generally high but can be unevenly distributed.Footnote 154,Footnote 155 A number of factors affect how people and communities understand, experience and respond to climate change, in some cases increasing risks and susceptibility to health impacts.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 269 Broader determinants of health, such as age, income, housing conditions, and community factors such as population density, level of economic development, income level and distribution, local environmental conditions and the quality and availability of health services all influence vulnerability to changes in climate.Footnote 152,Footnote 153,Footnote 155,Footnote 270-272

Factors that influence (both positively and negatively) community resilience to climate change need to be considered.Footnote 269 Community-based research initiatives can support innovation and inform strategic planning and capacity building efforts and be an important source of knowledge.Footnote 273,Footnote 274 The EnRiCH project (Enhancing Resilience and Capacity for Health), led by the University of Ottawa, is an example of a recent project that examined community resilience and developed, tested and evaluated community mobilization interventions to enhance resilience in at-risk communities.Footnote 275,Footnote 276 An important factor that can enable communities to be resilient in the face of extreme weather events and deteriorating community infrastructure is strong neighbourhood connectivity and cohesion.Footnote 269,Footnote 274 Similarly, Australia developed a strategic framework that identified social cohesion as valuable in guiding local climate change planning and action.Footnote 170,Footnote 277

Vulnerability to climate-related health risks can be reduced through prevention and adaptation.Footnote 154,Footnote 269 Encouraging public participation at all levels (e.g. local, regional and national) helps communities prepare for and respond to the health risks of climate change.Footnote 278 Health Canada's Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program for Northern First Nations and Inuit Communities supports the development of community projects across Canada's North that focus on climate-influenced health issues.Footnote 169,Footnote 243,Footnote 279 The program is unique in recognizing that the adaptive capacity of communities varies and that they experience different challenges. It encourages communities to become more engaged by integrating local knowledge with science-based knowledge to develop promising local adaptation strategies that address vulnerabilities.Footnote 243,Footnote 279-281 From 2008 to 2011, the program funded 36 community-based projects and developed a variety of communication materials (e.g. on drinking water, food security and safety, and land, water and ice safety) to support decision making on health-related issues.Footnote 243,Footnote 279-281 Through these measures, communities have also increased their knowledge and understanding of the health effects of climate change. This knowledge enables communities to find ways to address vulnerabilities at a community level, mitigate risks, adapt to the challenges and protect health.Footnote 279-281

More research into how populations and communities are vulnerable to changes in climate is needed to inform decision making.Footnote 155,Footnote 270,Footnote 271,Footnote 282 Vulnerability assessments can foster a better understanding of risks posed by climate change and inform the development and implementation of effective adaptation measures.Footnote 269,Footnote 278,Footnote 282,Footnote 283 Assessments need to be ongoing to address current and future risks and barriers to adaptation.Footnote 282,Footnote 283

Continuing investment in research

Health research is both valuable and important. More research into climate change can foster a greater understanding of how these changes influence the health of Canadians.Footnote 154 For example, the Public Health Agency of Canada's Preventative Public Health Systems and Adaptation to a Changing Climate Program (2011-2016) was initiated to conduct research and enhance surveillance methods, engage public health stakeholders and inform decision making on climate change adaptation.Footnote 284 Such research can help to answer specific questions or address existing knowledge gaps and shed more light on potential climate-related health risks. As well, contributing more knowledge to climate change discussions can help develop more appropriately targeted and evidence-based public health adaptation initiatives. Research can help identify more effective strategies and tools to protect those Canadians who are more vulnerable to exposures and risks. Research is also needed to enhance response capacity to handle the challenges that climate change is expected to place on public health in the future.Footnote 152,Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 284

Increasing education and awareness

Public communication and education initiatives play an important role in establishing healthy behaviours and choices.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 285 A more informed public, aware of the steps that can be taken to reduce risks and protect health, can also bring about changes in the environmental conditions that affect their health.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 285 For example, a health promotion approach to reducing sources of air pollution would encourage and support the use of more environmentally friendly means of transportation (e.g. walking, biking and using public transit), while promoting a more active and healthy lifestyle.Footnote 286

Ways to educate and raise awareness about climate-related health risks include broad public messaging on environmental health issues and targeted campaigns that focus on a specific sector (or target audience) and a particular health issue. Approaches that raise awareness of potential health risks and also provide specific advice on how Canadians can best protect themselves are also beneficial.Footnote 285,Footnote 287 Such approaches, which encourage people to play an active role in their own health and safety by being prepared could include public health messaging on health, safety tips, health marketing materials and educational toolkits for public health professionals' use.Footnote 288,Footnote 289 It can also be useful to consider different communication strategies and outlets, such as new technologies and social media, in order to disseminate messaging more effectively.Footnote 154,Footnote 285

Health promotional materials have been created to inform Canadians about reducing their exposure to the WNv.Footnote 290-292 Efforts have also targeted those at an increased risk of exposure such as active seniors and those who spend more time outdoors.Footnote 292 The province of Alberta utilized a series of marketing strategies including informational radio interviews called Let's Go Outdoors, insertions in newspapers and magazines targeted to high risk areas and a general public awareness campaign Fight the Bite.Footnote 292 As part of the WNv public education campaign, First Nations and Inuit Health regional staff provided consultations to First Nations residents and community and healthcare workers to educate about WNv and the steps to take against it.Footnote 293 Other provinces/territories and regions across the country have used similar strategies.Footnote 155

The Public Health Agency of Canada has developed a comprehensive action plan to educate and raise awareness of both the general public and healthcare professionals on Lyme disease to mitigate the risks to Canadians posed by the disease. The Action Plan on Lyme Disease will feature a series of communication activities including advertising campaigns, outreach materials, media engagement such as interviews, conference presentations and webinars, and social media activities.Footnote 211

Developing approaches to communication that are effective at getting people to adopt health-promoting behaviours is a central challenge.Footnote 154,Footnote 285,Footnote 294,Footnote 295 Research indicates that, despite public health messaging, people may not be acting on the information and making choices or changes to reduce health risks.Footnote 154,Footnote 294-296 For example, heat-health communication campaigns aim to increase knowledge of the potential risks to health from extreme heat and to influence individuals to adopt protective behaviours.Footnote 287 A review found that people had poor perception of heat-health risks and were confused by existing heat-health messages, and that messaging did not target the appropriate audiences.Footnote 294,Footnote 296 Effective public outreach initiatives need to be delivered during periods of high risk (e.g. before and during the warmer months and during extreme heat events) and through a variety of communication outlets such as media (mass/broadcast and targeted), interpersonal networks and community events (see the textbox "Air Quality Health Index").Footnote 174

Air Quality Health Index

The Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) is a health risk scale that describes conditions hourly and provides twice daily Environment Canada forecasts on the mixture of pollutants in the air.Footnote 297-299 Included are messages on how to reduce the short term associated risks as well as health advice targeted to specific vulnerable groups — children, seniors and people with cardiovascular and respiratory disease — as well as the general population. The goal of the index is to support Canadians in making informed decisions that can reduce associated risks to health from exposure to poor air quality.Footnote 155,Footnote 297,Footnote 298,Footnote 300

People can disassociate air quality health risks from their own situation, either by underestimating their own exposure or assuming the risks apply to other people who are more vulnerable.Footnote 155,Footnote 294 Most Canadians know that air quality advisories are provided in their area. However, this information initially had a limited impact in attracting attention and prompting actions to reduce personal exposure, even during poor air quality events.Footnote 155,Footnote 297,Footnote 300 In response, a number of social marketing initiatives were undertaken to make the AQHI as effective as possible at reaching sensitive populations. Media partnerships, particularly with The Weather Network, were also formed to increase the reach of AQHI through television, print, radio, automated telephone and the Internet.Footnote 155,Footnote 297,Footnote 298,Footnote 300 Partnerships were also developed with other government agencies and non-governmental organizations who work directly with sensitive populations.Footnote 300

An early evaluation of the AQHI showed an increased awareness of risks and use of information and products among at-risk groups. A later evaluation, in 2010, noted further opportunities to broaden the use of information and products.Footnote 297,Footnote 300,Footnote 301 Outreach efforts with non-governmental health organizations have led to broad support by the Canadian health community with positive signs with respect to public awareness.Footnote 302

To increase the effectiveness of communication campaigns, collaboration is needed to deliver consistent, audience-appropriate and easily understood messages. Communication materials should target vulnerable populations and their caregivers and proactive action strategies should consider differences in perceptions, knowledge and abilities. The effectiveness of public communication and education initiatives can be improved by engaging the community to identify risks, develop and share best practices, and tailor activities and products to the needs of specific regions, communities and populations.Footnote 174,Footnote 287,Footnote 294,Footnote 295

There is also a need to improve awareness and knowledge of the risks to health caused by climate change. Adaptation measures among public health and emergency management professionals and the general public can help in developing effective communication materials whose aim is to reduce health risks associated with climate change. Developed through Health Canada's Heat Resiliency Initiative, the report Communicating the Health Risks of Extreme Heat Events: Toolkit for Public Health and Emergency Management Officials identifies communication strategies, based on leading research and practice, to influence behaviours through health promotion campaigns.Footnote 287

Building and sustaining healthy environments

Improving the potential of communities to promote health in the face of climate change will be an ongoing challenge. More is needed to make Canada's infrastructure more resilient, particularly in relation to extreme weather events.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 303 The state and age of roads, sanitation facilities, wastewater treatment systems, flood control structures and building standards and codes are integral to the protection of health.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 303 Recent impacts of extreme weather events like the 2013 Southern Alberta floods demonstrated the need to develop new infrastructure designs that can better withstand more intense weather events.Footnote 304,Footnote 305 Initiatives to help support rebuilding aging infrastructure, such as the 2014 New Building Canada Plan are also important.Footnote 306 As current infrastructure is upgraded and replaced, it is important to consider new and updated design values, revised codes and building standards, and new approaches to incorporating climate change considerations into planning designs.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 307

In addition, it is important to consider the opportunities and limitations of various aspects of infrastructure in urban and rural areas in Canada in terms of their capacity to adapt to climate change.Footnote 153-155 About 82% of Canadians live in urban areas and this population is growing.Footnote 15,Footnote 308 While urban areas tend to be wealthier and have more access to services (e.g. healthcare, social services and education), they also tend to depend more on critical infrastructures (e.g. energy, transportation and water) and experience more severe heat stress and poorer air quality.Footnote 153,Footnote 309 The impact of extreme weather can also be exacerbated in highly populated areas. Also, with increased urbanization and population pressures, Canadians are moving into more marginal land, such as coastlines and floodplains. New construction and urban plans and designs should take into account protection from weather-related natural hazards, as these settlement patterns could increase health risks.Footnote 154,Footnote 155,Footnote 310-314

Likewise, smaller, remote and rural communities can experience challenges, particularly due to limited support services, resources and infrastructure, resulting in residents being less protected.Footnote 153,Footnote 315 Infrastructure in northern communities is particularly vulnerable to changing ice conditions and can present additional challenges to the design, development and management of infrastructure in the North.Footnote 154,Footnote 167,Footnote 266,Footnote 272 Access to tools that enable these communities to adapt infrastructure to these changing conditions is necessary.Footnote 266,Footnote 272,Footnote 316 The Northern Infrastructure Standardization Initiative, led by the Standards Council of Canada (SCC) with support from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, is one measure taken to address this issue.Footnote 317 The initiative supports adapting northern infrastructure to a changing climate by changing critical codes and standards to address the effects of climate change on new infrastructure as well as maintaining and repairing existing infrastructure. The SCC aims to identify gaps and needs in existing codes and standards to support infrastructure and ensure it reflects the unique circumstances of this region in light of changes in climate.Footnote 266,Footnote 316

As mentioned, strategic and smart land-use planning is essential.Footnote 155,Footnote 318 The design of cities and roadways, and the location of places of work and home and other aspects of land use all affect the health of Canadians.Footnote 154,Footnote 309,Footnote 319 For example, planning can influence how much Canadians need to use motor vehicles to get around, which also influences transportation's role as one of the major sources of air pollution.Footnote 309,Footnote 320 Neighbourhood designs that include high-quality pedestrian environments and a mix of land uses (e.g. planting trees, increasing green spaces, patterns of subdivisions, housing and buildings, etc.) can improve health by promoting active forms of transportation, reducing air pollution and associated respiratory ailments and lowering the risk of motor vehicle-related accidents.Footnote 309,Footnote 318-324

While these measures are not direct public health functions, there is still a role for public health to play. Public health officials can inform and educate the public about health risks, advocate for changes that promote and improve health and work together with land-use and building planners, community and regional officials to encourage the adoption of health-promoting changes in urban planning and community infrastructure.Footnote 318

Surveillance and monitoring

Research data and analysis gathered from public health surveillance systems and tools can support a number of public health functions.Footnote 325 In the case of infectious diseases, it can help to identify changes in disease trends, including patterns associated with changes in climate (see the textbox "The Rothamsted trap").Footnote 213,Footnote 326 It can also be used as a reporting function to identify vulnerable or affected individuals and communities in order to implement response and disease control measures to reduce further exposure to health risks.Footnote 325 During the WNv season, the Public Health Agency of Canada, together with other national, provincial and territorial public health authorities, produces a weekly WNv MONITOR report and map. This report summarizes the activity of the virus across Canada. Information in these reports can be used by provincial and municipal health authorities to ensure Canadians know how to reduce their exposure to risk.Footnote 327,Footnote 328 As well, research gathered through surveillance initiatives can provide a clearer picture of health concerns to facilitate informed decision making and appropriate public health action. This ensures efforts are targeted and resources appropriately allocated where they are most needed.Footnote 325 Research data informs and supports the development of policies and strategic plans such as the Public Health Agency of Canada's Action Plan on Lyme disease.Footnote 211 All of these measures are important in preventing and controlling infectious diseases.Footnote 329

The Rothamsted trap

In collaboration with Brock University and the Public Health Agency of Canada, Niagara Region Public Health constructed a Rothamsted trap to capture insects that may serve as carriers of infectious diseases.Footnote 213,Footnote 326,Footnote 330 The trap, measuring 40-feet high, acts like a vacuum, collecting around 300 insects per day from May to October.Footnote 331 The trap was modelled after the work of Rothamsted Research, an agricultural research centre in the United Kingdom that first developed the traps.Footnote 331 Although in service in Europe for a number of years, this Rothamsted trap is the first to be used in Canada.Footnote 213,Footnote 326,Footnote 330 As part of the Pilot Infectious Disease Impact and Response System program, this is an initiative in vector identification and disease surveillance. It can help researchers detect new/exotic disease vectors before human disease cases are reported. It can also support current vector-borne disease strategies and public health responses.Footnote 213,Footnote 326,Footnote 330

Early warning systems have been developed as a precautionary measure to detect a number of climate-related health risks including air quality concerns (see the textbox "Air Quality Health Index"), wildfires, extreme heat and ultraviolet radiation.Footnote 155,Footnote 191,Footnote 287,Footnote 332 These forecasting tools can help in mobilizing public health action by issuing public advisories and alerts to mitigate health risks before impending dangerous health conditions occur. These systems also support broader surveillance and information sharing initiatives.Footnote 155,Footnote 175,Footnote 191,Footnote 287,Footnote 332-335

Several communities in Canada, as well as in Australia, Europe and the United States, have developed heat-health action plans and warning systems such as Heat Alert and Response Systems (HARS).Footnote 174,Footnote 333-337 HARS are developed to reduce heat-related morbidity and mortality during extreme heat by alerting the public, including vulnerable populations, about the risks and providing individuals with information and other resources to help them protect themselves during an extreme heat event.Footnote 174,Footnote 338 Since 2008, Health Canada has worked with federal, provincial and municipal partners to implement a Heat Resiliency Initiative which supports the development of HARS. This initiative also aims to strengthen the capacity of communities, healthcare professionals and individuals to manage heat-related health risks.Footnote 339 Evaluations of the few existing HARS demonstrates that these systems can help to protect people from illness and death associated with extreme heat events particularly when based on knowledge of community- and region-specific weather conditions that result in increased heat-related health concerns.Footnote 174,Footnote 334,Footnote 338 Future efforts may consider public risk perceptions in relation to changing behaviours to protect health; choosing alternative communication strategies that increase awareness and change behaviours; conducting vulnerability assessments to identify and target interventions; monitoring HARS activities and evaluating them at the end of the heat season; and implementing long-term preventative actions that reduce heat exposure and negative health outcomes.Footnote 154,Footnote 174,Footnote 338,Footnote 340

Emergency planning

The potential for more frequent and severe extreme weather events necessitates effective emergency management measures. Indeed, planning for the unexpected is a key challenge posed by climate change.Footnote 155,Footnote 341 Climate-related emergencies can escalate quickly in scope and severity, cross provincial and regional boundaries, take on international dimensions and significantly impact health.Footnote 154,Footnote 155 Extreme weather events can overwhelm the capacity of communities and local governments to respond—particularly if they are unprepared. It is important to consider how extreme weather events can compromise critical infrastructure and emergency services, limit access to support services and resources and challenge efforts by emergency management personnel to manage exposure and reduce impact.Footnote 269,Footnote 341

Comprehensive risk management measures that (pre-impact) reduce, prevent, prepare for and mitigate emergencies, and help in the (post-impact) response and recovery can reduce health risks and protect health, lessen the impact on critical public services and preserve infrastructure and the environment.Footnote 269,Footnote 341-344 Proactive planning can also bring to light gaps or areas of deficiencies and limited resources, and identify more vulnerable population groups, to redirect or enhance efforts and resources where needed.Footnote 155 As well, the use of risk assessments and evaluations can help to reduce vulnerability and mitigate potential impacts. All of these community emergency management measures can help to increase community resilience.Footnote 269,Footnote 341

Continuing efforts

Canadians remain vulnerable to the effects of climate change and its impacts on the health. Public health has considerable experience in reducing risks to health from environmental change; this experience can be drawn upon to meet the challenges posed by climate change. Long standing, core public health functions can provide a strong basis for protecting Canadians from climate-related health risks. Efforts made now can significantly reduce vulnerability to the health impacts of future changes in climate.

Public health can:

- continue research to better understand how changes in climate affect health particularly that of vulnerable Canadians;

- increase awareness among public health professionals and the general public about the health risks of a changing climate;

- be proactive and consider short- and long-term climate changes;

- find ways to adapt to reduce the impacts on health;

- optimize ongoing assessments and share best practices and lessons learned to develop more effective public health adaptation programs; and

- support multijurisdictional, multidisciplinary collaborative approaches to tackle the challenges of climate change in Canada.

Page details

- Date modified: