Archived - Evaluation of the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health program 2014-15 to 2018-19

Prepared by

Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

March 2019

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Evaluation Purpose

- 2.0 Program Description

- 3.0 Evaluation Description

- 4.0 Findings

- 4.2 Effectiveness: Achievement of Outcomes

- 4.2.1 Access, Reach, and Use of Evidence-Based Resources

- 4.2.2 Usefulness of Evidence-Based Resources

- 4.2.3 Contribution to Policy and Decision Making

- 4.2.4 Addressing Emerging Issues and Knowledge Gaps

- 4.2.5 Fostering Collaboration with Public Health Partners

- 4.2.6 Fostering Collaboration among the NCCs

- 4.3 Efficiency

- 5.0 Conclusions

- 6.0 Recommendations

- Appendix A - NCCPH Program Logic Model

- Appendix B - National Collaborating Centre Profiles

- Appendix C - Evaluation Description

- Endnotes

List of Tables

- Table 1: NCCPH Program Planned Budget, 2014-15 to 2018-19 ($)

- Table 2: Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- Table 3: Other Knowledge, Synthesis, Translation and Exchange Initiatives in Public Health

- Table 4: Number of Visits to NCC Websites compared to Selected PHAC Web pages in 2017-18 (ranked from Highest to Lowest)

- Table 5: Distribution of NCCs Annual Budget

List of Acronyms

- CIHR

- Canadian Institute of Health Research

- CPHO

- Chief Public Health Officer

- NCCs

- National Collaborating Centres

- NCCAH

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health Canada

- NCCDH

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health Canada

- NCCEH

- National Collaborating Centre for Health Public Policy

- NCCID

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases

- NCCMT

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools

- NCCPH

- National Collaborating Centre for Public Health Canada

- NGOs

- Non-Governmental Organizations

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- SARS

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 593 KB, 56 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: 2019-06-24

Executive Summary

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCPH) program for the period of April 2014 to September 2018. The evaluation was conducted to fulfill the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and Treasury Board of Canada's 2016 Policy on Results. In the assessment of relevance, the evaluation examined the continued need for the program, understanding of the National Collaborating Centres' (NCCs') role, as well as alignment with government, PHAC, and public health priorities. In assessment of performance, the evaluation examined the achievement of expected outcomes, resource use, mechanisms for coordinating with PHAC, and efficiency related to the program model.

1. Program Description

The creation of the NCCPH program was announced in 2004, along with the PHAC and the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, as an integral part of the Government of Canada's overall national strategy to strengthen the public health system in Canada.

This program aims to make public health research more relevant and understandable for public health professionals and organizations, so that it can be used in the their day-to-day practices and in policy making (i.e., supporting science from policy to practice).

The NCCPH program distributes a total of $5.8M per year to six National Collaborating Centres (NCCs), located across Canada, that synthesize, translate, and share knowledge on a specific theme to make it useful and accessible to policy makers, program managers, and public health professionals.Footnote [a] Each Centre receives equal funding through a contribution agreement between PHAC and an external organization responsible for hosting the Centre. The six centres and their respective hosts are as follows:

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health (NCCAH), University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, British Columbia;

- National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH), British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver;

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCID), University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT), McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario;

- National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (NCCHPP), Institut national de la santé publique du Québec, Montréal, Québec; and,

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (NCCDH), St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

2. Key findings

Relevance

There is a continued need for knowledge translation services to make evidence-based information accessible and useful to public health professionals in support of decision making and policy making. In particular, there is a growing expectation that use of well-sourced and timely evidence will be the standard practice in public health decision making, but challenges remain in doing so (e.g., expanding volume and complexity of data, broadening of public health to include social determinants of health, ongoing resource constraints in the field). As well, in Canada's multijurisdictional public health system, there is an ongoing need to foster networks across jurisdictions in order to share information and best practices.

Although there are other organizations that provide knowledge synthesis, translation, and exchange services in public health, the evaluation found evidence that NCCs occupy a unique niche focused on translating evidence-based knowledge in a very practical manner to support public health professionals across the country. Moreover, NCCs differ from other organizations in that they are non-governmental, which gives them a greater ability to address needs on-the-ground. They are also national in scope, while other organizations tend to have a more provincial or local focus. Some key informants suggested, however, that there is a need to reassess the themes addressed by the Centres based on evolving public health priorities.

Since the last evaluation, there has been an evolution in the mandate of the NCCPH program, from focusing on strengthening public health capacity and targeting local level professionals, to supporting decision making and policy making at all levels of the public health system. Most, but not all, Centres have reflected this shift in program mandate in their collaborations. The intent of the NCCPH program clearly aligns with the Government of Canada and PHAC overall priorities of strengthening public health capacity and science leadership. However, despite NCCs being set up in a way that they can be more responsive to the direct needs of public health professionals, some questions were raised as to whether NCC work aligns well with public health sector priorities at the working level. These questions are partly due to a lack of awareness of how the NCCs develop their work plans, as they do collect input from a range of various sources to inform their development.

Achievement of Outcomes

The NCCs have produced a wide range of high quality knowledge translation products and activities, and are perceived as a credible go-to source on multiple public health issues. There are also many examples of NCC contributions to decision making and policy making in the public health field.

In many instances, the NCCs have responded to emerging needs, including identifying knowledge gaps. However, the current process for developing work plans makes it challenging for them to be nimble and address ad hoc issues as they arise.

The NCCs have undertaken many collaborations with external partners as part of their core business line. Those collaborations have allowed stakeholders to leverage each other's capacity to achieve results, as well as share information across regions and jurisdictions. In many cases, the NCCs have brought together stakeholders that governmental organizations would not have been able to convene in the same manner. Their ability to foster relationships was seen as a significant value-added service provided by the NCCs.

Collaboration happened regularly between two or three NCCs on a variety of initiatives. These collaborations were seen as productive, as each NCC had valuable expertise to contribute. However, the requirement for all six of them to collaborate on signature projects was seen as diverting limited resources that could be better used elsewhere.

Efficiency

Overall, the Centres were seen to be operating efficiently and using their limited resources in a prudent and innovative manner to deliver a significant number of outputs. However, their ability to deliver outputs has been curbed over time, as their funding from PHAC has declined from an annual allocation of $1.5M in the program's initial years, to a flat budget of about $974K per year for the current contribution agreement period (2015 to 2020).

Overall, the NCCPH program model has been seen as beneficial in helping the Centres operate efficiently, allowing them to access the services and expertise of their host organization, leverage their networks, and access funding to advance joint projects. The model of having Centres at arm's length from the Government of Canada has also given the NCCs the ability to remain apolitical and connected on-the-ground. However, while Centres are small in scale, they have to follow the procedures of both their host organization and their contribution agreement with PHAC. Current performance reporting requirements were seen as being cumbersome and time-consuming, especially considering the reduction of the program budget over time.

There was also limited interaction and communication between PHAC and the NCCs on priorities, making it challenging for the NCCs to align annual work plans with areas of interest to PHAC, in order to foster collaboration and avoid duplication. The designated executive lead initiative launched by PHAC in February 2018 has shown promise for creating closer collaborations between the NCCs and PHAC, but it is too early to assess the results.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Develop a collaborative two-way partnership between PHAC and the NCCs to promote greater awareness of each other's work and increase collaboration in areas of common interest.

Within PHAC, there has been a general lack of understanding of the role, mandate, and value of NCCs. Also, NCCs have expressed concerns that PHAC priorities are not communicated to them in a timely and systematic manner. This has caused a challenge for NCCs in aligning annual work plans to areas of interest for PHAC and in connecting with appropriate program areas. In light of this, PHAC should build on the initial efforts made by the executive lead initiative and engage more strategically and regularly with the NCCs, in order to leverage each other's knowledge, resources, and networks to advance common goals.

Recommendation 2

Explore opportunities, as part of the contribution agreement renewal, to ensure that each NCC remains relevant to emerging public health sector needs in terms of issues addressed, range of collaborations, and targeted audiences.

The NCCPH program mandate has evolved since the last evaluation, from focusing on strengthening public health capacity and targeting local level professionals, to supporting decision making at all levels of the public health system. Not all Centres have reflected this shift in the program mandate in their target audience and their collaborations, as they continue to focus on local practitioners. As well, NCCPH program topics may have been relevant when selected over 13 years ago, but there was a concern that those themes had never been revised since the program was created, and that knowledge translation efforts should look at other issues that are aligned with emerging global public health priorities. Given that the current funding cycle ends in 2020, PHAC should explore opportunities to ensure that the NCCs remain relevant, including clarifying directions given to them, in order to achieve the current program mandate and fulfill the evolving needs of the public health sector.

Recommendation 3

Explore options for maximizing resource allocation to the NCCs and allow them to use those resources more efficiently to fulfill their core mandate. This includes:

- Revisiting the requirement for all six NCCs to collaborate on signature projects;

- Providing the NCCs with the flexibility to adapt their work plans to address emerging issues, considering that addressing knowledge gaps is part of their core mandate; and

- Streamlining performance measurement requirements.

The reduction in funding allocation from PHAC to the NCCs has curbed their capacity to deliver outputs. In this context, PHAC should investigate opportunities to maximize resource allocation and manage expectations. More specifically, PHAC should revisit the requirement for all six NCCs to collaborate on signature projects, given that they are collaborating with each other through other means. PHAC should also provide NCCs more flexibility to address emerging issues as they arise, without having to make significant revisions to their work plans and without affecting accountability for results achieved during the year. PHAC should streamline performance measurement requirements, with a particular emphasis on providing useful data to inform ongoing program management and evaluation, while also keeping the NCCs' reporting burden in line with their current level of funding allocation.

Management Response and Action Plan

| Recommendations | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables | Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

| Recommendation 1: Develop a collaborative two-way partnership between PHAC and the NCCPH to promote greater awareness of each other's work and increase collaboration on areas of common interest. | Agree. The notion of "partnership" is now central to PHAC's business relationship with the NCCs. | 1. Formalize the mandate of the PHAC-NCC Executive Leads as key executive liaisons for each of the six NCCs, and with the objective to enable of enabling effective and strategic collaborations between PHAC and the NCCs. |

1.1 Establish PHAC-NCC Executive Lead (PEL) Terms of reference |

30 September 2019 | ||

2. Raise internal awareness of NCCs annual work, exchange on emerging public health issues arising from NCCs business domains, and foster new NCCs collaborations with PHAC programs and other public health stakeholders. |

2.1 A reviewed engagement plan for the NCCs, including the presentation of selected products/issues to PHAC staff and managers through various mechanisms (branch governance, PHACtually speaking special sessions, PHAC/HC broadcast news). |

30 September 2019

|

Vice-President, Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control Chief Science Officer | Existing resources | ||

2.2 The renewal of the contribution agreements for 2020 and beyond will identify a partnership relationship between the NCCs and PHAC and the principles under which the partnership relationship is preserved. |

30 September 2019 | |||||

| Recommendation 2: Explore opportunities, as part of the contribution agreement renewal, to ensure that each NCC remains relevant to emerging needs of the public health sector in terms of issues addressed, range of collaborations and targeted audiences. | Agree. | 1. Identify and review with PELs and NCCs key priority areas for public health knowledge mobilization. | 1.1 A section expressing areas of interest in knowledge mobilization is included in the next solicitation request to NCCs. | 30 June 2019 | ||

| 1.2 A planning meeting with NCCs leads and the CPHO Report Unit | 30 September 2019 | |||||

| 2. Work with CGC to refine renewal process and documentation for efficiency and efficacy, yet retain essential TBS requirements. | 2.1 Restructured / simplified solicitation process documentation | 30 June 2019 | ||||

| 3. NCCPH Program to review NCC annual work plans for their ability to address a broad range of actions (collaborations, networking, and gap identification) that reflect key priorities. | 3.1 The annual work plan review process / schedule is documented and updated to include consultations of relevant programs, PELs and PHAC regional directors. |

30 September 2019 |

Vice-President, Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control Chief Science Officer | Existing resources | ||

Recommendation 3: Explore options for maximizing resource allocations to the NCCPH and allow them to use those resources more efficiently to fulfill their core mandate. This includes:

|

Agree. | 1. In the way forward, NCCs will no longer be required to commit to a 'signature' project involving all six Centers. The program will continue to encourage the NCCs to collaborate among themselves, as they see fit, on big projects. |

1.1 Removal of NCCPH 'signature' projects from agreement requirements, as documented in the proposed agreements submitted for signatures |

30 June 2019 |

Vice President, Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control Chief Science Officer | Existing resources |

| 2. The current work planning cycle allows flexibility by the NCCs to propose and implement changes to their work plans based on emerging priorities. NCCPH Program will pro-actively discuss changes in the work plan and possible in-year additional funding to adapt to changes. | 2.1 Provision of a work planning flexibility in the Agreement, as documented in the proposed agreements submitted for signatures. | 30 June 2019 | ||||

| 3. NCCPH Program will review current program monitoring and practices to lessen the burden on NCCPH recipients, yet fulfill the Agency's obligations under the Financial Administration Act and CGC standard operating procedure (SOP). | 3.1 Updated NCC reporting requirements documentation | 30 September 2019 |

1.0 Evaluation Purpose

The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCPH) program for the period of April 2014 to September 2018. Thee valuation was conducted to fulfill the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and Treasury Board of Canada's 2016 Policy on Results.

2.0 Program Description

2.1 Program Context

Following the 2003 outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome(SARS), a review from the National Advisory Committee on SARS (the Naylor Report) identified challenges facing the public health system in Canada among multiple public health actors at the regional, local, provincial, and territorial levels. The Naylor Report recommended improvements to Canada's public health infrastructure by establishing an arms-length organization to support other levels of government in strengthening public health systems, while fostering an environment of collaboration among public health actors. One "core element" of the public health infrastructure described in the Naylor Report was a central resource for knowledge translation and evidence-based decision making, including the identification of research needs. Footnote [1]

In response to this need, the Government of Canada established the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and, at the same time, established the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network (PHN) and the NCCPH program. These three initiatives were components of the Government of Canada's efforts to strengthen the national public health system in Canada.

2.2 Program Profile

The National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) Footnote [b] were created to provide a national focal point for sharing knowledge in priority areas for public heath, while building on existing expertise in regions across Canada. In other words, the Centres aim to promote evidence-informed decision making through the following activities:

- 1. Synthesizing knowledge to support public health practice at all levels of the system;

- 2. Translating and disseminating knowledge to make it useful and accessible to public health policy makers, program managers, and practitioners;

- 3. Identifying critical knowledge gaps and stimulating work in priority areas; and

- 4. Developing links between public health researchers and practitioners to strengthen practice-based knowledge networks.

The NCCPH program established six collaborating Centres hosted at independent organizations across Canada, either a university or provincial public health organization, each specializing in a specific public health priority area. These six Centres are the following (see Appendix B for more details on each centre):

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health (NCCAH), University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, British Columbia;

- National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH), British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver, British Columbia;

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCID), University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba;

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT), McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario;

- National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (NCCHPP), Institut national de la santé publique du Québec, Montréal, Québec; and

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (NCCDH), St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

2.3 Previous Evaluations

The NCCPH program was previously evaluated in 2014, covering the period from 2008-09 to 2013-14. Footnote [2]

The previous evaluation found that the NCCPH program broadly aligns with Government of Canada and PHAC roles and priorities, and that there was a continued need for mechanisms to enhance evidence-based decision making in public health. However, there was a lack of clarity regarding alignment and complementarity with other organizations engaged in knowledge translation, synthesis, and exchange. The previous evaluation also found that the program had made progress towards increasing evidence use to inform public health practice, though progress varied across the Centres. It was shown that NCC knowledge products and activities were used by public health professionals to support evidence-based decision making, though the topic-specific design of Centres restricted their ability to respond to emerging public health issues.

The evaluation made recommendations related to clarifying the role of PHAC and the NCCs in knowledge translation and enhancing performance measurement. The program's Management Response and Action Plan was fully implemented.

2.4 Program Narrative

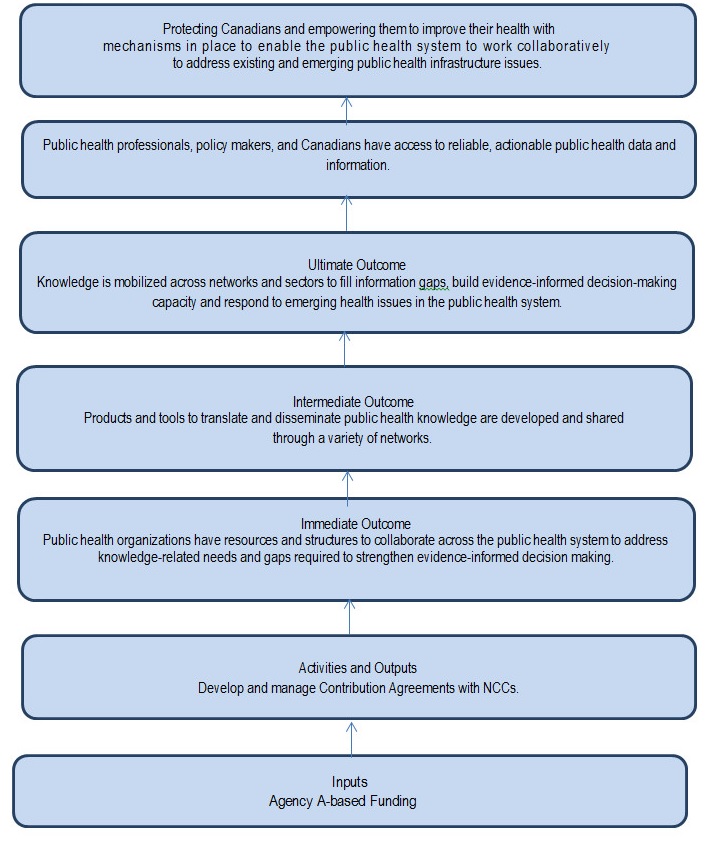

The objective of the NCCPH program is to promote the use of knowledge for evidence-informed decision making by public health professionals across Canada (i.e., supporting "science to policy to practice").Footnote [3] The NCCPH program is built on a theory of change that improved availability, access, and collaboration in regards to knowledge will enable better practices and decisions from public health professionals. This, in turn, is expected to lead to better public health outcomes.

The expected results of the NCCPH program are the following:

- Mechanisms are in place to enable public health partners to work collaboratively to address existing and emerging public health infrastructure issues;

- Public health organizations are engaged and participate in collaborative networks and processes; and

- Public health professionals and partners have access to reliable and actionable public health data and information. Footnote [4]

Achieving these results supports PHAC's goal of protecting Canadians and empowering them to improve health, with mechanisms in place to enable the public health system to address existing and emerging public health infrastructure issues. The link between the activities, outputs, and outcomes of the NCCPH contribution program is described in the program logic model (Appendix A).

2.5 Program Alignment and Resources

The program's financial data for fiscal years 2014-15 through 2018-19 are presented below (Table 1). The program distributes approximately $5.8 million each year to the six NCCs, with each Centre receiving about $974 thousand annually. The program's total expenditures were $31.6 million over five years.

| Year | Grants & Contributions | Operation & Maintenance | SalaryTable A footnote A | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-15 | $ 5,842,000 | $ 97,000 | $ 317,700 | $ 6,256,700 |

| 2015-16 | $ 5,842,000 | $ 97,000 | $ 339,680 | $ 6,278,680 |

| 2016-17 | $ 5,842,000 | $ 107,695 | $ 442,956 | $ 6,392,651 |

| 2017-18 | $ 5,842,000 | $ 71,900 | $448,492 | $ 6,362,392 |

| 2018-19 | $ 5,842,000 | $ 40,000 | $442,342 | $ 6,324,342 |

| Total | $ 29,210,000 | $ 413,595 | $1,991,170 | $ 31,614,765 |

Data Source: Estimated planned budget provided by the Chief Financial Officer Branch at PHAC.

|

||||

3.0 Evaluation Description

3.1 Evaluation Scope, Approach, and Design

The evaluation examined core issues of program relevance and performance, namely the following:

- 1. Continued need for the program;

- 2. Understanding of the role of the NCCs;

- 3. Duplication, overlap, and complementarity with other programs;

- 4. Alignment of NCC priorities with public health sector and PHAC priorities;

- 5. Effectiveness through achievement of expected outcomes, (i.e., the extent to which the NCCs collaborate with other public health partners, use and usefulness of knowledge products, impact on informing decision making); and

- 6. Economy and efficiency through assessment of resource use and efficiency of practices (i.e., use of available resources, mechanisms for alignment with PHAC, program models).

Specific questions on each of these issues were developed based on program considerations and these guided the evaluation process. A detailed description of the evaluation methodology is presented in Appendix C.

Data collection for the evaluation was comprised of the following:

- A review of program documentation, including financial and performance measurement data; and

- A total of 78 interviews, 32 of which were with external stakeholders (e.g., academia and experts, non-governmental organizations, provinces and territories, professional associations across Canada), 28 were with NCC staff, management, board members, and host organizations, and 18 were with PHAC representatives.

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may have implications for the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. Table 2 below outlines the limitations encountered during the implementation of the selected methods for this evaluation. Also noted are the mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings can be used with confidence to guide program planning and decision making. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

There was a lack of consistency in how some of the performance measurement data was reported between NCCs and over several years (e.g. web statistics and numbers of products). In addition, it was understood that the annual performance measurement questionnaire submitted by the NCCs did not include all outputs produced by the NCCs in a given year (e.g., NCCs may have not reported all their collaborations in a given year). |

It was difficult to report valid and reliable totals and trends over time at the level of the whole program and to make comparisons across the NCCs. Assessments of NCC outputs and collaboration may not be exhaustive. |

Performance measurement data was taken at face value. Aggregate numbers derived from performance data in this report have been interpreted with caution and are accompanied with proper caveats to help readers interpret their meaning. Where feasible, data from the performance measurement was triangulated with other sources of information. |

| The evaluation did not conduct a survey of public health professionals in Canada in order to measure their uptake and awareness of NCC products. | The evaluation, for the most part, did not include the viewpoints of public health stakeholders who had no knowledge of, or interaction with, the NCCs. Therefore, the evaluation does not fully assess where there are gaps in terms of knowledge and awareness of the NCCs and their work within the Canadian public health system. | Data collected from the interviewees was triangulated with other sources to assess the reach of the NCCs. As well, interviewees were asked to provide an opinion on the relevance of the NCCs, (e.g., gaps in reach, issues, and needs addressed). In addition, an analysis of NCC partnering was performed to show reach by region and type of organization (allowing gaps to be inferred). |

| The selection of key informants for this evaluation was based on suggestions provided by PHAC regional offices, the program secretariat and the NCCs. Key informants who completed an interview had previous knowledge of the NCCs. | Since the evaluation did not include the viewpoints of public health stakeholders who had no knowledge of, or interaction with, the NCCs, it is possible the key informants had bias toward the NCCs. | A vast number of individuals were invited to participate in the interviews and the sampling strategy was designed to ensure a representation of all regions of Canada and of a variety of public health stakeholder groups (frontline personnel, regional and national policy and program representatives, academics, etc.). Key informants generally had a balanced perspective on the NCCs raising both positive points and areas for improvement. Information collected from the key informants was validated with other sources of data where possible. |

4.0 Findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued Need for Knowledge Translation

There is a continued need to support efforts to make evidence-based information more useful and accessible to public health professionals, in order to support decision making and policy making. There is also an ongoing need to foster networks and collaboration across the public health system in order to share information and best practices.

Since its launch in 2004, the NCCPH program has aimed to address the need for knowledge mobilization in public health and facilitate the application of evidence and emerging research in policy development and practice implementation. In the context of this evaluation, findings from all lines of inquiry have indicated that there is a continued requirement for public health professionals to access and use well-sourced evidence in a collaborative manner to support decision making and policy development.

A review of recent literature indicates that, to achieve objectives of better population health, more widespread adoption of evidence-based strategies across the public health landscape, in innovative formats continues to be a necessity. Footnote [5] To support this, access to timely, reliable, and actionable information through cross-sector partnerships is a necessary priority for public health in the 21st Century. Footnote [6] Additionally, studies found that, despite many accomplishments in public health over the last 30 years, practitioners and policy makers alike must pay greater attention to evidence-based approaches to public health, as there are numerous direct and indirect benefits,including the following: Footnote [7]

- Optimal intervention strategies and greater equity in health levels across communities;

- A higher likelihood of successful programs and policies being implemented;

- Greater workforce productivity; and

- More efficient use of public and private resources.

In order to achieve these benefits, researchers noted that wide-scale dissemination of practical information on effective public health interventions must occur more consistently at all levels of government. Footnote [8]

Key informants, including NCC staff and external stakeholders, echoed findings from the literature and document reviews that there is both a growing expectation to implement evidence-based decision making and, more specifically, that there has been an evolution in practice related to its acceptance as the standard over the last five years. In light of this, the majority of internal and external key informants noted a need for ongoing support to address challenges in the capacity to use evidence-based information effectively. Challenges identified by key informants include the following:

- The sheer volume, breadth, complexity, speed of change, and variety (blogs, podcasts, webinars, and videos) of information continues to expand. External key informants noted that it is a significant challenge for public health professionals to sort through what is relevant and use it in a practical way; to "get the right information and data, make it scalable and transferable, and push it out to the right people at the right time.";

- Because responsibilities in Canada's health system are shared between different level of governments (i.e., federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal), there was a perception among some key informants that there is an ongoing need to overcome jurisdictional barriers by fostering networks and collaboration across the system to share information and best practices;

- The nature of public health is broadening. The traditional core of public health nurses and doctors has expanded to include many who are entering the field with no practical experience. For example, the growing focus on the social determinants of health has led to a wider field of experts (e.g., first responders, social workers, urban planners) entering the field of public health. Not all of them are equipped to use available health evidence to inform their decision making, and thus need additional support; and

- Public health professionals, especially at the local and regional level, often have limited capacity to stay up-to-date on the available literature and research, and to interpret and apply it to their local practice due to budget and time constraints. Assistance is therefore needed to make this information more readily accessible and relevant.

4.1.2 Understanding the Role of the NCCs

The role of the NCCs is fairly well understood by public health professionals outside of PHAC; however, internal key informants noted a general lack of understanding of the NCCs' role within PHAC.

The majority of external key informants were able to articulate the mission and vision of the NCCs. Many external key informants understood that the broader role of NCCs was to support the public health system by making related research more relevant, accessible, and understandable for practice and in policy making, and this was seen as well aligned with PHAC's fundamental responsibilities. A few external key informants noted that NCCPH had a role to play in sparking innovation and applying new methods and tools to address public health problems.

Based on interviews conducted with internal key informants, there appears to be a widespread lack of awareness within PHAC as to the ongoing role and mission of NCCs, and how they relate to the work PHAC undertakes. A majority of internal key informants noted a lack of clarity on whether it is the NCCs' mandate to support PHAC's work and on how PHAC could engage with the NCCs to advance areas of common interest. (See section 4.3.3 for more details).

Based on internal and external key informant interviews, it seems that this lack of clarity on the role of NCCs is, at least, partly explained by perceptions from both the NCCs and PHAC staff. On one hand, as explained by NCC key informants, the Centres typically do not see PHAC as part of their primary targeted audience. On the other hand, the majority of internal key informants have reported not knowing how to engage with the NCCs but also not being able to engage with the NCCs because they are perceived to be at arm's length from PHAC. Overall, it has been a challenge to find the right balance between supporting PHAC while also maintaining the independence of NCCs and their ability to develop work plans based on needs identified on-the-ground.

4.1.3 Adapting to an Evolving Program Mandate

The NCCPH mandate has evolved since the last evaluation. Its goal has shifted from strengthening public health capacity and targeting local level professionals to focusing on supporting decision making at all levels of the public health system. However, not all NCCs target all levels of the0020public health system and not all have adjusted the scope of their collaboration to reflect the shift in program mandate.

As noted by program authorities and in public documents, such as PHAC's Report on Plans and Priorities, for years previous to 2014-15, the NCCPH program mandate was to strengthen public health capacity, translate health knowledge, and promote and support the use of knowledge and evidence by public health professionals in Canada, in collaboration with provincial, territorial, and local governments, academia, public health professionals, and non-governmental organizations.

The program mandate statement shifted with the renewal of contribution agreements in April 2015. As noted in public documents, such as the 2015-16 PHAC Report on Plans and Priorities, the program mandate statement was expanded from a specific focus on strengthening public health capacity to promoting the use of knowledge for evidence-informed decision making by policy makers, program managers, and professionals.

The shift in program focus was also accompanied by a change in target audience and collaborators. The mandate statement prior to the contribution agreement renewal clearly outlined an objective to collaborate with local governments. However, the current mandate statement targets public health professionals in different roles across the public health system, from frontline practitioners to managers and policy makers.

Most NCCs have reflected this shift in program mandate in their target audience. As confirmed by most NCC key informants, the Centres' target audience is generally public health professionals across the system. However, the NCCEH tends to have a particular focus on public health inspectors, who represent a narrower group of Canadian public health professionals. The NCCAH is different from other NCCs since it is the only population-based NCC and has a commitment and responsibility to Indigenous individuals, families, and communities. However, according to NCC key informants, NCCAH's targeted audience includes Indigenous and non-Indigenous organizations, networks, practitioners, educators, and government organizations that have a vested interest in Indigenous health and wellness.

In practice, as further discussed in section 4.2.1, according to surveys and assessments conducted by the NCCs, users of their products are generally individuals or organizations working at the local and regional levels of the public health system.

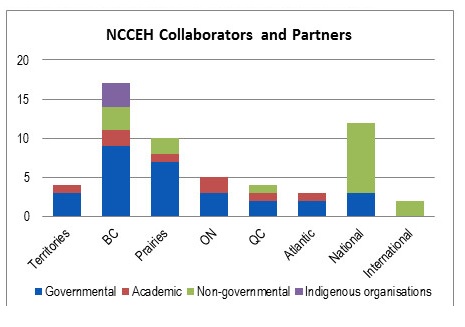

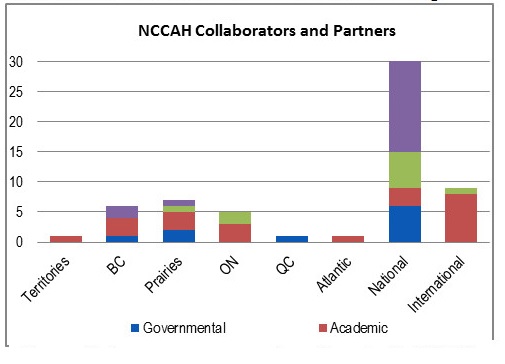

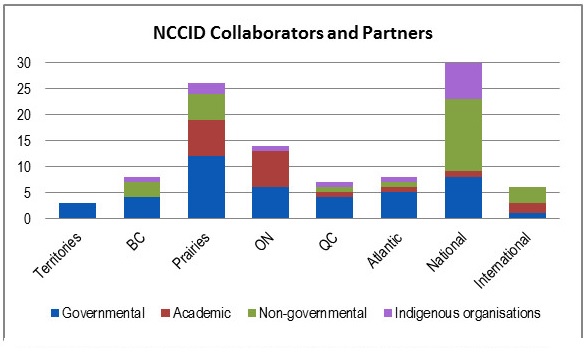

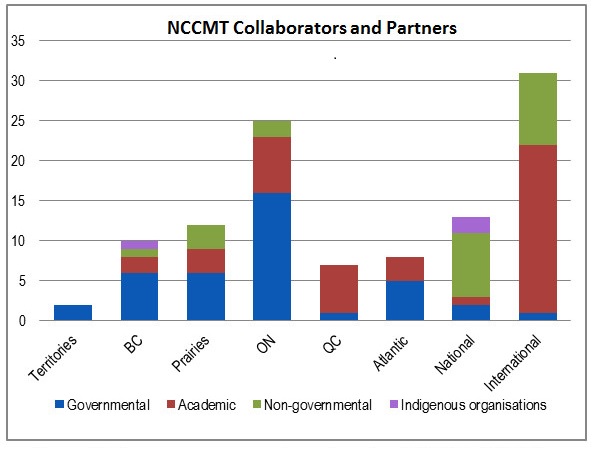

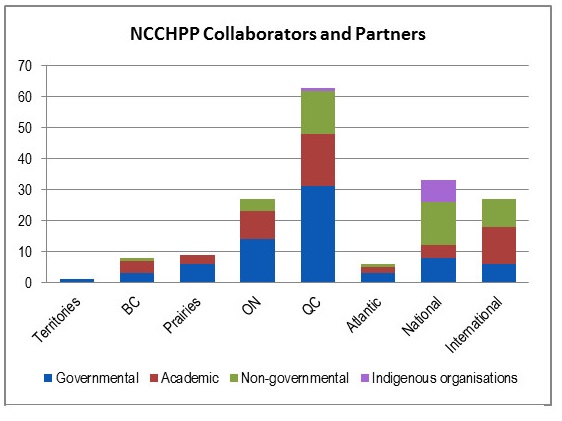

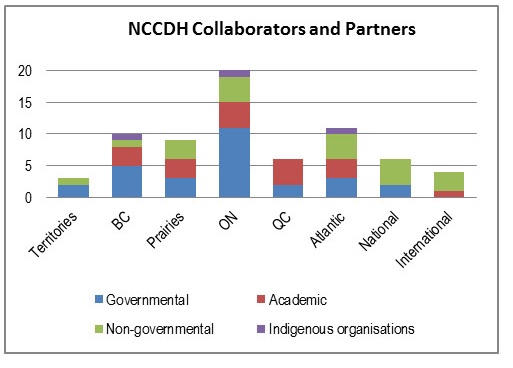

Furthermore, an assessment of collaborators and partners reported in the NCC performance data shows that not all NCCs have a national scope to their collaboration. Specifically, most of NCCEH, NCCHPP, and NCCMT reported collaborators and partners were located in the region where each of those centres are located, or were located outside of Canada in the case of NCCMT Footnote [c]. Other NCCs appear to have a more national scope when it comes to working with collaborators and partners (see section 4.2.1 and Appendix B for more details). Additionally, the same performance data shows that all NCCs reported having collaborators and partners mainly within provincial, territorial, or local governments. The only exception is NCCAH, which has a broader range of collaborators from the Government of Canada and national-level Indigenous organizations.

4.1.4 Overlap, Duplication, and Complementarity

There are other organizations involved in the field of knowledge synthesis, translation, and exchange, but evidence suggests that NCCs have found a unique niche focused on translating evidence-based knowledge into a very accessible and practical manner that supports public health professionals across Canada.

As indicated in the previous 2014 NCCPH Evaluation Report, there are number of other organizations and initiatives that support knowledge, synthesis, translation, and exchange activities in the public health area. This has not changed significantly in the last five years. Table 3 below presents an overview of some of the key players currently in the field Footnote [d].

The previous evaluation was not able to conclude on the extent to which knowledge, synthesis, translation, and exchange efforts that existed at that time complemented the NCCPH program. In the context of the current evaluation, most internal and external key informants noted that, despite any overlap, most NCCs have found their niche and target different audiences, or focus on different issues than organizations included in their field. Other external knowledge users noted that, even if there is some duplication, this can be a positive factor, as organizations can share knowledge and expertise and build on common areas of interest. In general, it was seen that that NCCs differ from other organizations in the sense that their focus is national, they are non-governmental, and their scope is to translate evidence-based information in a very practical way.

As shown in Table 3, the evaluation team did not find organizations dedicated to knowledge translation and synthesis on Indigenous health issues.

Many external key informants also noted that the NCCs complement others in the field and ensure a level of consistency across the country regarding access to the best public health evidence. Some examples of complementary activities include the following:

- NCCs share interest in research content with academia, but complement them by providing a platform to disseminate research findings in an accessible and relevant manner. As noted in the Evaluation of the CIHR Knowledge Translation Funding Program (2013) Footnote [9], additional effort towards partnerships and dissemination activities has received limited recognition within the university environment and more needs to be done to foster this.

- External knowledge users noted that provincial public health entities may have similar mandates to the NCCs, but they are provincial in scope and given finite resources. Working with the NCCs allows them to leverage common areas of interest, fill in gaps, and share collective talents and collaboration while avoiding redundancy, in order to achieve maximum possible impact across Canada.

| KSTE Initiative | Scope | Services/Activities/Tools Provided | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Reach | Disease Specific vs Broad Public Health | Knowledge Creation | Knowledge Translation | Networking/ Collaboration | Education/ Training | |

| Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange (CATIE) | National | AIDS/HIV | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) | National | Public Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Institute of Population and Public Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (IPPH- CIHR) | National | Public Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Pan-Canadian Public Health Network | National | Public Health | Yes | |||

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | International | All Health | Yes | |||

| Public Health Ontario | Provincial | Public Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Institut national de sante publique du Québec (INSPQ) | Provincial | Public Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| British Columbia Centre for Disease Control | Provincial | Communicable and chronic disease, preventable injury and environmental health risks | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional Health Authorities (approx. 73 across Canada almost half in Ontario) Footnote [10] | Local level | Public Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Wellesley Institute | Local (Greater Toronto Area) | Social Determinants of Health/Health Equity | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Data Source: Website review for each initiative; accessed October 2018. |

||||||

4.1.5 Alignment with Government and Public Health Priorities

The overall mandate of the program aligns with Government of Canada and PHAC overall priorities around strengthening public health capacity and science leadership. However, at the working level, it is not clear if the activities of the NCCs align well with PHAC and public health sector priorities. As well, some key informants noted a need to re-assess the themes addressed by the Centres based on evolving public health priorities.

Over the last five years, improving knowledge transfer and evidence-based decision making in the public health workforce and subsequently protecting the health of Canadians have been identified as priorities for the Government of Canada. As such, the NCCPH program's broad mandate in this area continues to align with priorities set forth in the following sources:

- PHAC's five-year strategic plan (Strategic Horizons 2013-2018)Footnote [11] includes the following two key priorities: (i) strengthening the formal mechanisms of the public health system through enhanced information sharing, partnerships, and guidelines, and (ii) fostering, promoting, and strategically managing surveillance, science, and research to support public health decisions and actions.

- The newly appointed Chief Science Advisor reported in her open letter to the Prime Minister on her first 100 days in office (January 2018)Footnote [12] that " the demonstration of the Government's commitment to science and to evidence-based decision making has sparked a collective enthusiasm that I intend to build upon to achieve two elements of my mandate: promote a dialogue among Government and academic scientists, and raise public awareness of scientific issues as they support informed decision making." More specifically, the letter also notes " the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge into the scientific evidence that guides Government decision making is critically important"; highlighting the ongoing importance of NCCAH in particular.

- One of the key expected outcomes of Canada's new Science Vision,Footnote [13] which was launched as part of Budget 2018, is support for evidence-based decision making that will ensure science is at the heart of all federal policy-making. Efforts to deliver on this outcome have been further informed by Canada's Fundamental Science Review 2017Footnote [14], which emphasized the need for research to inform evidence-based policy making across all government departments and agencies.

Findings on the level of alignment between NCC and PHAC priorities at the working level are mixed and uneven across the NCCs. As reported by both internal and NCC key informants, discussion is generally limited between PHAC and the NCCs on how to align their priorities. See section 4.3.3 for more details.

External key informants had mixed perspectives on whether or not the work of NCCs was well aligned with public health sector priorities. On one hand, a number of external key informants felt that the NCCs were well aligned with sector priorities, and were even responsible for pushing agendas forward in emerging areas. These areas include health equity considerations for public health inspectors (NCCDH and NCCEH), training in Indigenous child and youth health to reflect the Truth and Reconciliation call to action (NCCAH), online health impact assessment training modules (NCCHPP), and refugees and public health intervention strategies (NCCID), to name a few. See Section 4.2.4 for more detail on NCCs' work in these areas.

On the other hand, many other external key informants generally agreed that the work of the NCCs was useful, but raised questions on whether it was focusing on the right issues. Many external key informants commented on not knowing what input is considered in work plan development and not being consulted on it.

That being said, as part of their regular working process, the NCCs use different means to identify the knowledge needs of the public health sector. These mechanisms include conducting periodic environmental scans and targeted surveys, and obtaining feedback from various public health professionals through their advisory board and networks of collaborators. Other important mechanisms for the NCCs to stay abreast of emerging issues in public health are external requests for information and invitations to collaborate that they receive on a continuing basis. These serve as sources of information on stakeholder needs for NCCs to consider in their work planning. As reported by NCC key informants, this information is used to define priorities in their draft work plans and drive their activities.

Some internal and external key informants noted concerns about the program renewal along current themes and host organizations. They noted that NCCPH program topics may have been relevant when selected over 13 years ago, but identified a need to re-assess the themes addressed by the Centres based on evolving public health priorities.

New themes suggested by one or more external key informants included the following:

- Public Health Law and Economics;

- Chronic Disease (addressing commonalities between heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, dementia, or looking at healthy weight, obesity, and nutrition, etc.);

- Quality of Life, Wellbeing, and Community (addressing broader issues than just mental health); and

- Public Health and Technology (big data analytics, apps, artificial intelligence, etc.);

4.2 Effectiveness: Achievement of Outcomes

4.2.1 Access, Reach, and Use of Evidence-Based Resources

Evaluation evidence indicates that, overall, the six NCCs have successfully mobilized evidence-based information through a variety of channels, thus reaching professionals across Canada.

Products and activities generated by the NCCs

NCCs work together to promote the use of their scientific research and knowledge to strengthen public health practice, programs, and policies in Canada. To accomplish this, the Centres are expected to identify knowledge gaps, foster networks, and provide a range of evidence-based resources, including knowledge translation services. Footnote [15]

According to performance data provided by the NCCs, they developed a variety of knowledge translation products and activities each year, including peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed publications, such as blog posts, commentaries, position papers, fact sheets, guidance documents, evidence reviews, videos, podcasts, infographics, book chapters, articles, and reports. Footnote [16]

Overall, NCCs distributed consistent levels of knowledge translation products and activities during the period covered by the evaluation. From 2015-16 to 2017-18, they collectively produced a total of 250 to 450 knowledge translation products each year, with an average of 260 knowledge translation activities each year. They offered a wide range of knowledge translation activities designed to meet the unique needs of their target audience, including in-person workshops and programs, web-based training and webinars, conference presentations, and knowledge exchange events.

Reach of NCC products and activities

The evaluation examined the reach of NCC products and activities using web metrics and survey of users conducted by the NCCs. Readers should keep in mind that this data may not provide a complete assessment, since each Centre uses a variety of channels to distribute their products, including mailing lists, workshops, webinars, online courses, presentations, courses, national gatherings, etc.

Web metrics in Table 4 indicate that the NCCs have generated a relatively high level of online engagement with their products. In 2017-18, NCCMT and NCCAH in particular had levels of unique visitors two to three times higher than the highest ranking comparable web content from PHAC. NCCID's web content was visited nearly twice as often as PHAC's Infectious Disease web content.

| Websites | Unique Visitors | Average Time on Site |

|---|---|---|

| NCCMT | 195,687 | 5:30 |

| NCCAH | 127,142 | 2:59 |

| PHAC Vaccines and Immunization | 94,542 | 0:57 |

| PHAC Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequalities | 45,088 | 2:34 |

| NCCID | 44,636 | 2:27 |

| NCCDH | 44,598 | 1:44 |

| NCCEH | 40,264 | 2:00 |

| NCCHPP | 34,566 | 2:27 |

| PHAC Infectious Diseases | 25,393 | 1:01 |

| PHAC CPHO Report | 5,928 | 1:00 |

Data Source: Self-reported data from NCC (as shown in 2017-18 Performance Measurement Questionnaire) and PHAC web analytics |

||

An analysis of survey data reported in evaluations conducted by the NCCs show that, in general, frontline public health providers made up between 20 to 30% of knowledge users. Other types of knowledge users included public health program managers, community and non-governmental organizations, researchers and students, medical officers of health, and health care providers. While all NCCs reached public health professionals in general, some Centres reached more specialized audiences. The NCCAH, for example, most commonly reached community-based organizations and organizations serving Indigenous populations, while the largest group of knowledge users for NCCEH was public health inspectors.

Each Centre was able to demonstrate that their training and products reached users from across Canada. Based on survey data from the Centres, individuals from Ontario made up between 30-60% of knowledge users, followed by users from Quebec, who accounted for 10-15% of knowledge users. This is generally aligned with the distribution of the Canadian population. Footnote [17] Some Centres demonstrated a higher proportion than average of knowledge users in the region where they were located, relative to other Centres. This included NCCHPP where approximately 30% of users were from Quebec, NCCDH in Nova Scotia where users from their province were 10% compared to approximately 1-3% among other Centres, and NCCAH and NCCEH in British Columbia, where users from that province made up between 17-20% compared to under 10% in other regions. Since the evaluation did not conduct an assessment of the awareness of NCCs among public health professionals in Canada, it is not possible to determine whether those Centres have a higher concentration of users within their own region because users are more aware of the Centre located closer to them. In addition, two NCC key informants commented that regional distribution of their users reflects the geographic distribution of public health professionals, especially whose practice and expertise relates to the work of a given Centre across Canada. The evaluation team has not been able to confirm this statement since there were no statistics available on the number and distribution of public health professionals in Canada.

4.2.2 Usefulness of Evidence-Based Resources

In general, NCC products are perceived as a credible go-to source by knowledge users. They described these products as timely and relevant, and shared the view that they were useful to a broad public health audience.

When asked about the relevance and timeliness of NCC resources, most key informants, in both PHAC and external organizations, shared the opinion that NCCs produce highly credible work that is pertinent to their needs. Some knowledge users highlighted that this was particularly important where local or regional public health units operate in a situation of resource scarcity.

Survey evidence collected by the NCCs confirms that knowledge users have a positive view of the quality and relevance of their products. Surveys conducted by NCCAH, NCCMT, and NCCHPP showed that 80 to 100% of survey respondents had high levels of satisfaction with training and knowledge synthesis products, and had access to up-to-date information.

In particular, a few external knowledge users specifically noted that NCCAH was an excellent source for culturally-relevant knowledge products that reflect Indigenous cultural and historical realities. This is validated by survey responses from the NCCAH that indicate that over 90% of knowledge users found their products and services to be culturally relevant. One key informant noted that this Centre allows students in universities to have access to Indigenous knowledge as it pertains to public health issues, knowledge that may not otherwise be available.

While there was a general level of agreement that NCCs produced timely and relevant information products and services, a small proportion of knowledge users, mostly working within PHAC, noted a concern in regards to the ability of NCC products to meet local needs or the needs of specialized knowledge users. Specifically, a few external key informants noted that, due to the broad scope of issues addressed by NCCs, coupled with the fact that their work addresses public health issues from a national perspective, knowledge translation products are not always relevant to local and regional realities or the needs of specialized knowledge users. In general, these concerns were considered an acceptable limitation on the usefulness of the NCCs knowledge translation products, given an understanding of the Centres' mandate and resource levels.

4.2.3 Contribution to Policy and Decision Making

There are many examples of NCC products being used to inform and support policy and decision making.

Knowledge users in the field of public health across Canada, and within PHAC, described a variety of ways in which they referred to NCC knowledge products and activities. The most common way knowledge users reported using these products was by accessing training provided by the Centres for professional development, while educators working in academia and in community programming used NCC materials as resources to support learning for students or community members. As well, several internal and external knowledge users also indicated that they consulted NCC knowledge translation products to receive an overview of available evidence, which often informed their work. The NCCs also addressed requests from stakeholders at all levels of the public health system, such as requests for information and consultations on specific issues, for letters of support (e.g., for research funding proposals), to participate in peer reviews, to submit articles for publication, to partner on a project, or to present at an event. NCCs have also helped foster relationships to support knowledge exchange on key public health issues by leveraging their existing networks with key stakeholders on specific policy and practice issues, including frontline health and public health professionals, partners working within other provinces and territories, not-for-profit organizations (NGOs), and Indigenous organizations.

Furthermore, anecdotal evidence suggests a variety of ways in which NCC products have been used to support evidence-informed decision making by a broad range of knowledge users. Specific examples heard from key informants and validated with evidence from internal and public documents for each NCC include the following (See Appendix B for more detail):

- NCCEH: Following an incident at a Humboldt, Saskatchewan long-term care facility where three people died from carbon monoxide exposure, NCCEH conducted a review of ways to protect vulnerable groups from the dangers of carbon monoxide. The Centre collaborated with the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control to consult with experts for the development of a Carbon Monoxide Monitoring and Response Framework for Long-term Care Facilities, and the Framework was piloted in the Saskatoon Health Region. According to a few key informants working in the region, safety recommendations from the Centre's Carbon Monoxide Framework are now embedded in regulations for British Columbia and Saskatchewan.

- NCCAH: A model on Social Determinants and Indigenous Health developed by NCCAH has been adopted by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care into their guidelines on relationships with Indigenous communities.

- NCCID: Many primary care physicians serve patients that have symptoms of a viral infection but face real or perceived pressure to prescribe antibiotics for treatment, resulting in overuse and increased resistance. The NCCID has distributed non-prescription pads all over Canada to encourage physicians to "prescribe" non-medical strategies to manage viral symptoms. Key informants working with the Centre indicated that the initiative was highly effective at encouraging physicians to make decisions on promoting public health, and that many other provincial and local health units have adapted the pads for their own regions. Furthermore, the Centre is working with Nova Scotia to develop a similar tool for veterinarians.

- NCCMT: An emphasis from the NCCMT on developing tools to improve processes targeted at public health professionals has been supporting evidence-informed practice in local public health units. For example, after participation in the Centre's knowledge broker program, launched in 2014, members from the Region of Peel Public Health Unit implemented evidence-informed decision-making processes on how they conduct business. The unit introduced regular "applicability and transferability" meetings to help link evidence to program implementation. These meetings included frontline practitioners.

- NCCHPP: Several external knowledge users in the field of public health describe having used NCCHPP's health impact assessment on their processes to better understand the impacts on public health of a program or policy made at the local level.

- NCCDH: In Ontario, NCCDH's resources on the role of public health in addressing health equity were used as the framework in an initiative funded by a grant from Public Health Ontario to develop guidance on Health Equity indicators. This guide provides local public health units with a comprehensive set of evidence-based indicators to support their work to measure and address health inequality.

Further to those examples, NCCs have informed policy making by the Government of Canada in general: some NCCs have appeared before Senate and House of Commons Standing Committee hearings to provide information on issues such as mental health of Indigenous peoples (NCCAH), antimicrobial resistance (NCCID), the impacts of radon on health (NCCEH), and the impacts of extreme heat (NCCEH).

4.2.4 Addressing Emerging Issues and Knowledge Gaps

There are many examples of the contributions NCCs have made to address emerging public health issues. However, the current process for developing work plans and their limited resources make it challenging for them to be nimble. In addition, NCCs are only able to address emerging issues where there is already a great deal of existing data.

External key informants and performance data have identified many examples of NCC products and resources that address emerging public health issues, including:

- Work on public health aspects of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples (NCCAH, NCCDH and NCCHPP) and racism in public health (NCCDH, NCCAH);

- Guidance on risks posed by cannabis cultivation (NCCEH);

- Review and guidance on opioid overdose prevention (NCCHPP);

- Work on impacts of the built environment on public health (NCCDH, NCCEH, NCCHPP, NCCAH);

- Webinars on Point of Care HIV testing (NCCHPP and NCCID);

- Podcasts to answer questions from medical officers of health on the Zika virus (NCCID); and

- Knowledge resources on Ebola outbreaks, as a result of a request from PHAC (NCCMT).

The evaluation found numerous examples of how the NCCs have addressed emerging issues, and some external key informants praised the NCCs as being responsive 'go-to' sources of pertinent and timely information on hot-button issues. However, many others, both internal and external, were often not confident that NCCs had been nimble or actively contributed to providing information on emerging issues in a timely manner. In this regard, internal NCC staff explained that their annual work plan process is set over the months leading up to a new fiscal year and is difficult to change once established. A few external key informants noted that the NCCs' scope of action pertains to issues where there is already a great deal of data and research available, but NCC key informants reported being active in convening actors across the country on emerging issues where data and research is lacking.

4.2.5 Fostering Collaboration with Public Health Partners

The NCCs undertake collaborations with a range of partners as part of their core line of business. These collaborations aim to achieve greater results than participants could achieve alone and to build networks across the system. Overall, NCCs' ability to collaborate on different initiatives and to network with different partners across the public health system is seen as one of the most valued capabilities of the Centres.

Mechanisms for collaboration, purpose, and reach

Collaboration between the six NCCs and public health stakeholders is a core aspect of the NCCPH program and it is systematically recorded in NCC annual work plans. External key informants and NCC staff described collaborations as a strategic means of addressing knowledge needs related to specific issues. Collaborations enable the NCCs to broaden their reach beyond what they could achieve by acting alone.

As shown in the performance data and key informant interviews, the NCCs have each developed networks of partners over time, through a range of different mechanisms. Typically, NCC collaborations consist of the following type of activities:

- NCCs join with other stakeholders to undertake collaborative projects;

- All NCCs have collaborated with partners on helping to organize and present at conferences, such as the Canadian Public Health Association's annual national gathering, and different regional or profession-based gatherings;

- NCCs may act as a co-sponsor or collaborator for other groups, such as acting as a co-sponsor for researchers applying for CIHR funding, especially in terms of support for knowledge translation;

- NCCs have organized or supported different community of practice networks. In one case, the NCCDH's Health Equity Clicks online community was approximately 1,980 members and the Health Equity Collaboration Network has around 40 members. NCCs jointly collaborated to provide an organizational platform for the Rural, Remote and Northern Public Health Network; and

- NCC leads may participate on the advisory boards of other organizations or of other NCCs. At the time of the evaluation, NCCAH and NCCDH representatives sat on the Canadian Council for Social Determinants of Health.

NCCs are reporting to PHAC on the collaborators and partners they had over a given year as well as the names of the projects where these collaborations/partnerships occurred. An analysis of collaborations and partnership data reported for 2015-16 to 2017-18Footnote [e] show that approximately 570 individual collaborations were documented, giving an average of 95 collaborations per Centre over three years. The greatest level of reported collaboration was with governmental organizations at all levels of the public health system, with a focus on provincial and territorial governments or local governments. These were followed by academic groups, NGOs and Indigenous organizations. While most NCCs reported having most of their collaboration with governmental organizations, NCCMT reported having slightly more collaborators and partners from the academic domain than from governmental organizations. NCCAH also reported the highest number of collaborators from national-level Indigenous organizations and academic groups.

In terms of geographical distribution, the highest concentration was with national-level organizations; however some NCCs tended to focus more on their own geographic area. The data shows that NCCHPP and NCCEH reported having collaboration and partnerships mostly with organizations located in their own regions but reported national-level collaborations as their second highest area of focus. In contrast, data reported by other centres show that NCCDH highest concentration of collaborations was in Ontario, NCCAH had the most national-level collaborations and NCCMT was most active internationally. Of note, although the program scope is national, about 14% of NCC reported collaborations were with organizations located outside of Canada. For more details on the collaborative activities for each NCC, see the profiles in Appendix B.

There were many examples of collaboration between PHAC and the NCCs found in the performance data. The purpose of these activities varied widely and pertained to the following:

- The production of reports or resources, such as the NCCMT producing learning materials aligned with PHAC's core competencies;

- The organization of forums on specific topics with a range of different stakeholders, such as a meeting on National Indigenous Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections hosted by NCCAH, and a national roundtable on Antimicrobial Stewardship with NCCID;

- Extending each other's work, such as PHAC supporting NCCID to assist Manitoba's Southern Health Region in implementing an antimicrobial stewardship program;

- Getting advice from NCCs, such as NCCAH reviewing the Chief Public Health Officer's (CPHO) Annual Report on the State of Public Health in Canada;

- Developing training or participating in working groups, such as PHAC participating in an NCCHPP-led project on Population Mental Health and Wellness Promotion; and

- Using NCCs as a communications platform, such as NCCDH serving as the host for the Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health website.

As shown in performance data, the level of collaboration between PHAC and the NCCs varied across the Centres. NCCID, NCCAH and NCCDH have had ongoing collaborations and involvement with PHAC on common initiatives or to share knowledge. Of note, among all the Centres, NCCID reported the highest level of interaction with PHAC, but internal key informants often mentioned not knowing what value NCCID added to PHAC's activities. The level of reported involvement with PHAC is much lower for NCCMT and NCCHPP, and very limited for NCCEH. Consistently, both the NCCEH and internal key informants acknowledged that there is very little alignment between the work undertaken by this Centre and PHAC. Anecdotal evidence showed that NCCEH interacted more with Health Canada than PHAC on environmental public health issues (e.g., the management of crude oil spill incidents from a public health point of view).

Challenges that hampered collaboration between NCCs and PHAC were reported by key informants and are further discussed in section 4.3.3 of this report.

Benefits of collaborations

External key informants confirmed that collaborations and networks put in place by the NCCs have allowed partners to leverage each other's capacity to achieve results, to share information across regional, professional, and jurisdictional silos, and to bring a diversity of perspectives to a given issue. They explained that the collaborative and trustworthy nature of the NCCs encourages engagement from stakeholders and the development of long-term relationships, helps the NCCs better identify and validate knowledge gaps and needs, and facilitates the sharing of information.

In addition, key informants noted that the NCCs have brought together stakeholders that governmental organizations would not have been able to in the same way. This is particularly noteworthy for NCCAH, which has been successful in engaging with national Indigenous organizations. One reason given by key informants for this strength of the NCCs is that they are seen as entities that do not have a political agenda, and this allows them to be trusted by a wide variety of stakeholders to convene discussions and transfer information between jurisdictions more easily than PHAC could. One key example identified by key informants was the forum Towards TB Elimination in Northern Indigenous Communities, organized in January 2018 by NCCID, with the support of NCCAH, NCCHPP, and NCCDH. This forum brought together Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders from across seven provinces and territories to share experiences on addressing tuberculosis at the community level and discuss intersecting factors, such as the history of colonization policies and social inequities affecting population health.

While key informants generally agreed on the value achieved by NCC collaboration, some external key informants said that the NCCs could have been more strategic and systematic in their engagements to maximize information sharing and resource use for knowledge translation, as well as avoid duplication of effort. Suggestions included increasing their liaisons with existing networks of public health professionals and the three existing provincial public health organizations, as well as taking part in more regional and national conferences, with the idea that personal interactions with the NCCs will grow their audience. That being said, NCC key informants indicated that reductions to their funding allocation over time have reduced their capacity to participate in various events (see section 4.3.1 for further details on resources allocation).

4.2.6 Fostering Collaboration among the NCCs

Collaboration and coordination happen regularly between the NCCs on a variety of initiatives. While collaboration is seen as beneficial and productive when it occurs organically on projects where NCCs have expertise to contribute, the requirement for all six of them on to collaborate on signature projects is seen as diverting limited resources that could be more effectively spent elsewhere.

The contribution agreements require the NCCs to collaborate together on different initiatives. As reported in both interviews and program documents, the NCCs have put in place various mechanisms to foster collaboration among them, including the following:

- All NCCs communicate regularly via lead and manager committee meetings to share information on emerging issues and knowledge gaps in order to identify opportunities for collaboration. Work plan priorities are also discussed, as well as common language for reporting on collaborative initiatives; and

- The NCCs also convene communications committees to coordinate cross-promotion online and at conferences, as well as on evaluation. They co-fund a secretariat function to manage a cross-NCC website and serve as a single window for discussions with PHAC about the program.

In addition, some NCCs have adopted additional practices to promote information sharing and collaboration with other centres:

- Some NCC leads sit on the advisory boards of other Centres;

- Some share their draft work plans with other Centres to identify opportunities for collaboration, or avoid potential duplication or overlap in their activities; and

- Some Centres also proactively contact other NCCs to identify potential partners for particular projects.

As part of their coordinated approach, all six Centres contribute to an annual NCCPH Knowledge Translation Award and to the Knowledge Translation in Public Health Medicine webinar series, delivered in partnership with the Public Health Physicians of Canada, where each NCC provides content for webinars designed to meet knowledge gaps on specific topics and continuing education needs.

In addition to these initiatives, PHAC directed the NCCs in 2015 to undertake signature collaboration projects involving every Centre, in order to show the value that they could bring to a topic when working together. PHAC directed the NCCs to reserve 6% of their annual budget (funds and in-kind salaries for staff time) to contribute to these six-way collaborations. Since 2015, the following signature projects have been completed:

- Population Mental Health Promotion;

- Influenza; and

- Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting.

At the time of the evaluation, the NCCs were working on public health matters related to long-term public health responses to evacuation due to natural disasters in Canada.

The Population Mental Health Promotion signature project resulted in the publication of resources on population mental health promotion for children and youth. A forum was held in 2018, in partnership with PHAC, the Canadian Mental Health Association, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, and the Mental Health Commission of Canada, with a wide representation of stakeholders to clarify the roles of public health in addressing mental health issues.