Evaluation of the Autism Spectrum Disorder Program 2018-19 to 2021-22 (Public Health Agency of Canada)

Download in PDF format

(804 KB, 41 pages)

Organization: Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2023-07-28

Prepared by the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

March 2023

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Purpose of the evaluation

- Evaluation scope

- Program profile

- Context

- Key findings: Role

- Gaps and opportunities

- Key findings: Effectiveness

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix 1: Data collection and analysis methods

- Appendix 2: Program spending and internal challenges

- Appendix 3: Autism strategy and surveillance history

- Appendix 4: Other federal investments in ASD

- Appendix 5: ASD Strategic Fund: Project description and results

- Appendix 6: Autism monitoring data sources

- Endnotes

List of acronyms

- AIDE

- Autism and/or Intellectual Disability Knowledge Exchange Network

- ASD

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- CAHS

- Canadian Academy of Health Sciences

- CHP

- Centre for Health Promotion

- CHSCY

- Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth

- CSAR

- Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research

- CSD

- Canadian Survey on Disability

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- HPCDPB

- Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch

- NAS

- National Autism Strategy

- NASS

- National Autism Spectrum Disorder Surveillance System

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

Executive summary

There is no "one-size fits all" approach to describing autism and people on the spectrum. Both the person-first approach (e.g., "person with autism") and identity-first approach (e.g., "autistic person") are valid, and ultimately it is best to respect individual preference and use language that is the most comfortable to the person on the spectrum. PHAC does not recommend the use of one approach over another.

As part of the development of the National Autism Strategy, the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS) has adopted the identity-first approach, as a result of their broad consultation process. This evaluation report will follow the same line for consistency.

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that can include impairments in speech, non-verbal communication, and social interactions, combined with restricted and repetitive behaviours, interests, or activities. Each person with ASD is unique, and the term "spectrum" refers to the wide variety of strengths and challenges reflected among those with the disorder. In 2019, 2% of Canadian children and youth aged 1 to 17 years were diagnosed with autism, with males four times more likely than females to receive an ASD diagnosis.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is one of many organizations addressing ASD in Canada. Other key partners and stakeholders include local public health authorities, provincial and territorial (P/T) governments, other government departments, and national and community-based organizations. The development of a pan-Canadian strategy on ASD has been discussed for over 10 years, with various consultations taking place outside PHAC to determine the needs of autistic individuals and of their families. PHAC initiated the development of the National Autism Strategy (NAS) in 2019. PHAC's ASD program is led by the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch (HPCDPB) and includes the ASD initiative, as well as surveillance activities. PHAC's planned spending on ASD activities for the evaluation period was approximately $4.5 million per year.

This evaluation covered ASD program activities from 2018-19 to 2021-22, and used several lines of evidence, such as file and document review, web analytics, and interviews to assess PHAC's ASD role and the effectiveness of its activities.

What we found

To date, PHAC has undertaken activities to address ASD, including community-based funding and a knowledge exchange organization, as well as surveillance activities. These activities are largely well aligned with its federal public health role. Although PHAC used a social determinants of health approach to determine funding priorities for the ASD Strategic Fund, some projects did not strongly align with PHAC's mandate. For example, some projects had an employment focus, which might better fit under P/T and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) mandates. Important gaps remain and, although the majority of them fall under P/T jurisdictions, some gaps appear to align with the federal public health role in the areas of stakeholder engagement and collaboration, evaluating and disseminating promising practices, and enhancing surveillance.

Although community-based projects were short in duration, they made some notable advancements by increasing the knowledge and skills of program participants and, in some cases, helping autistic individuals develop coping strategies, and helping practitioners and caregivers improve support. Projects were promising, but the short-term nature of funding did not allow them to reach their full potential or ensure the sustainability and scalability of operations and activities. The Autism and/or Intellectual Disability Knowledge Exchange Network (AIDE) built an online portal, developed and shared multiple online resources, and established several networking hubs across Canada; however, there is limited evidence of uptake of these activities.

The guidelines on pediatric assessment of ASD were released in 2019, filling an important gap in progressing toward a more consistent approach to diagnosing ASD across Canada. PHAC has made important advancements in determining how many are diagnosed with ASD through national surveillance activities, including establishing reporting on indicators beyond prevalence, and expanding geographical coverage. The ongoing actions taken to address current data gaps (e.g., collecting data on all ages) will help build the evidence for informed decision making. Within PHAC, there are opportunities to strengthen internal decision making once ASD data become more complete.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Ensure that gaps related to areas of greatest needs that fall within the federal public health role are addressed by PHAC in the upcoming National Autism Strategy.

The evaluation found a few gaps in addressing ASD could be filled by PHAC, given its federal public health role; however, resources are scarce. Mindful of resource availability, PHAC should focus on aligning its work with the areas of greatest need within the National Autism Strategy, while strengthening its convenor role. This may include, but should not be limited to, clearly communicating actions that result from recent engagements, and clearly defining roles and expectations for all participants as part of the upcoming National Autism Strategy.

Recommendation 2: Enhance ASD Initiative design and performance measurement.

The short-term duration of funding did not allow community-based projects to meet their full potential. PHAC should explore the possibility of funding projects over a longer timeframe. This longer timeframe, as well as greater performance measurement requirements, would allow them to generate promising practices and, as a result, contribute to the knowledge base of 'what works' in ASD through strong impact measurement. In addition, funding priorities could be considered in collaboration with key partners and stakeholders, with a focus on autistic individuals and their families.

Strong performance measurement data is critical to understanding the achievement of goals, the impact of activities on the target population, and for continuous improvement. This was absent in some projects due to the duration (e.g., the ASD Strategic Fund) or lack of planning (e.g., AIDE). Strong performance measures should be defined, and their collection planned at the onset of funding to ensure that it is collected throughout the project duration.

Recommendation 3: Continue to strengthen national ASD surveillance efforts, with a focus on establishing internal ASD priorities and plans.

Current activities to enhance national ASD surveillance are a step in the right direction in ensuring that prevalence estimation is improved, that indicators beyond prevalence are captured, and that disaggregated data is available. That work needs to continue. As more comprehensive data becomes available, there will be more opportunities to use this data for decision making within PHAC. Both the Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research (CSAR) and the Centre for Health Promotion (CHP) need to determine their joint ASD priorities moving forward to ensure that their short- to medium-term priorities align in their respective work plans, and to ensure that surveillance informs decision making.

Purpose of the evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation was to examine the relevance and effectiveness of PHAC's ASD activities. Given that the program area is relatively new, PHAC's role in addressing ASD is part of the scope of this evaluation. In addition, attention was given to the achievement of results, including progress towards planned outcomes.

Evaluation scope

The scope of this evaluation covered ASD activities from 2018-19 to 2021-22. Multiple lines of evidence were used (See Appendix 1) to address the following questions:

- What should be PHAC's role as it relates to ASD? Is PHAC investing in areas that are consistent with a federal public health mandate to achieve maximum impact? Are there unmet needs?

- Are ASD program activities achieving their expected results?

- Have program participants gained resources, knowledge, and skills (short-term)? Have program participants improved health behaviours and improved protective factors or reduced risks (medium-term)?

- Have funded projects been able to demonstrate sustainability to better serve the needs of Canadians?

- Is surveillance data timely, complete, and useful for internal and external stakeholders?

- Are knowledge sharing and convening activities effective?

The achievements of the National Autism Strategy, as well as those of the second round of projects funded under the ASD Initiative are out of scope for this evaluation as they were in progress at the time of data collection.

Program profile

The overall objective of PHAC's ASD program is to address the complex and diverse needs of individuals with ASD and their families and caregivers. The program is composed of the ASD Initiative and related surveillance activities.

The ASD Initiative, created in 2018, includes the ASD Strategic Fund and the creation of AIDE Canada. Both components, as well as ASD-related policy work, which is led by the Centre for Health Promotion (CHP). ASD surveillance activities contribute to the overall ASD program and those activities fall under the Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research (CSAR). Both CHP and CSAR operate within PHAC's Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch (HPCDPB).

CHP key activities:

- manage the ASD Strategic Fund and AIDE Canada funding (i.e., the ASD Initiative);

- develop the National Autism Strategy;

- convene ASD partners and stakeholders; and

- oversee ASD-dedicated contents on PHAC website.

CSAR key activities:

- develop surveillance information and evidence on ASD; and

- manage the contribution agreement with the Canadian Paediatric Society on the development of pediatric ASD clinical assessment guidelines.

PHAC's total planned spending on autism spectrum disorder-related activities for the evaluation period (2018-19 to 2021-22) was approximately $15.8 million. See Appendix 2 for detailed budget and spending data.

As shown in Table 1 below, the first round of ASD Strategic Fund, in 2018, focused on supporting autistic Canadians, their families, and their caregivers by providing opportunities to gain resources, knowledge, and skills, and enhance economic inclusion to improve their wellbeing. This first round embraced a social determinants of health approach, which included matters, such as employment opportunities, that are not included in typical health promotion programming. The second round of funding in 2021 focused on mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on autistic Canadians.

| N/A | Targeted recipient groups | Area of focus or objective | Funding and duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASD Strategic Fund: Solicitation 1 | Organizations such as not-for-profit organizations; P/T, regional, and municipal governments or agencies (open solicitation) | Community-based projects that will support innovative program models, help reduce stigma, and support the integration of health, social, and educational programs to better serve the complex needs of autistic Canadians and their families | $4.2 million over 2 years (2018 to 2021) |

| ASD Strategic Fund: Solicitation 2 | Organizations such as not-for-profit organizations; P/T, regional, and municipal governments or agencies (open solicitation) | Community-based projects to address the impact of COVID-19 on autistic Canadians | $4.9 million over 2 years (2021 to 2023) |

| AIDE Canada | Pacific Autism Family Network (direct solicitation) | Creation of AIDE Canada, a network that provides access to online resources and local networking opportunities in six hubs for autistic Canadians and their families | $10.9 million over 5 years (2018 to 2022) |

Context

Understanding the environment and history of ASD is important when considering PHAC's role and activities in this area. The following section provides an overview of these elements as well as a statement on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ASD and PHAC's activities.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that can include impairments in speech, non-verbal communication, and social interactions, combined with restricted and repetitive behaviours, interests, or activities.Footnote 1 Each person with ASD is unique, and the term "spectrum" refers to the wide variation in strengths and challenges reflected among those with the disorder.Footnote 2 In 2019, 2% of Canadian children and youth aged 1 to 17 years were diagnosed with autism, with males four times more likely than females to receive an ASD diagnosis.Footnote 3

ASD can only be diagnosed by trained professionals, although this varies across each province and territory. For example, in New Brunswick, pediatricians and psychologists are the only ones that can provide a diagnosis, while in Ontario this can be carried out by family physicians, pediatricians, psychologists, or nurse practitioners.Footnote 4Footnote 5 There was no 'national level' guidance on how to diagnose and treat ASD until recently. In 2019, PHAC funded the development of Canadian Pediatric Association position statements on ASD diagnosis. However even that guidance is limited because it is focused on children. Research has shown that early diagnosis and access to interventions can lead to better long-term outcomes.Footnote 6

Over the last few decades, there have been improvements in the early detection and diagnosis of ASD among children, leading to an increase in detected cases, and thus in reported prevalence among children. Nonetheless, diagnostic capacity is unequal across P/Ts, leading to differences in ASD prevalence across the country. Canada still does not have national-level guidance for autistic adults and, therefore, diagnosis of adults is limited, and prevalence is unknown.Footnote 7

PHAC has been working to address ASD for a few years. Please see Appendix 3 for historical information on the development of the National Autism Strategy and national ASD surveillance.

Finally, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on autistic people is not known yet. However, activities carried out under PHAC's ASD program had to readjust their delivery to adopt an online format, and timelines had to be shifted in some cases as a result of internal staff temporarily joining PHAC's response efforts. Where applicable, this is acknowledged in the report.

Key findings: Role

To assess the relevance of the program, the evaluation examined alignment of PHAC's current ASD role with federal priorities and mandate. Gaps to address ASD were also determined with a focus on gaps that may fall under the federal public health role.

Alignment of PHAC's current ASD role with federal priorities and PHAC mandate

PHAC's current ASD activities are aligned with its federal public health role in that PHAC supports community-based projects and public health guidelines, provides policy leadership (e.g., national priority setting), conducts surveillance, supports and undertakes knowledge transfer and exchange initiatives, and collaborates and engages with stakeholders. PHAC's ASD work is well aligned with the current priorities of the Government of Canada. Although PHAC used a social determinants of health approach in determining community-based projects priorities, some projects did not strongly align with PHAC's mandate.

PHAC's mandate

Public health in Canada is a shared responsibility between the federal and P/T governments. PHAC has the mandate to promote, prevent, and control infectious and chronic diseases, address public health emergencies, and be the focal point for Canada's expertise internationally. As a science-based organization, PHAC applies scientific knowledge to its work and facilitates national approaches to public health policy and planning.Footnote 8 PHAC's areas for action in health promotion and disease prevention programming include program development, community capacity building, public education, inter-sectoral collaboration, and information synthesis and exchange.

PHAC's ASD mandate and priorities

Over the last five years, PHAC has had the mandate to undertake the following activities to address ASD:

- build a national-level surveillance system in collaboration with public health authorities, P/Ts, and other government departments (OGD), and analyze and report on national results. Collaboration with OGDs, such as Statistics Canada, takes place to supplement available data.

- enhance and complement existing ASD surveillance, modernize the underlying infrastructure, improve knowledge translation efforts, and provide additional capacity to analyze the resulting data.

- support community-based interventions to help autistic Canadians and their families, and support the creation of a new network. This network is responsible for developing and sharing information on ASD and offering local events using a hub approach.Footnote 9 The program authority that led to the creation of the ASD Strategic Fund acknowledged due to the complexity of ASD, investments that embrace a social determinants of health approach are necessary.

- play a strong policy and intersectoral collaboration role by enhancing dialogue between stakeholders and facilitating national approaches to address ASD. This has been done through the development of a National Autism Strategy (NAS) in collaboration with other jurisdictions, families, and stakeholders, as per the Minister of Health's mandate letters in 2019 and 2021.Footnote 10Footnote 11

Alignment between PHAC's role and ASD mandate and activities

Overall, PHAC has been carrying out its federal public health role related to ASD, which aligns with its broad mandate (e.g., stakeholder engagement, community-based funding and surveillance) in addition to addressing the specific commitments outlined in ASD policy and program authorities, and Government of Canada priority-setting documents.

With regards to surveillance, PHAC's ASD activities align with its role, as it led the development of a national autism surveillance system and continues to take a leadership role in developing new and enhancing existing data, such as the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY). However, when it comes to community-based funding, the linkage between PHAC's role and some of the areas covered by the ASD Strategic Fund might not be straightforward:

- Social inclusion through employability falls more appropriately under the mandate of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) although such projects were funded through the ASD Strategic Fund's first project cohort. This appears to be rectified – employment-related projects were removed from funding priorities in the second cohort as a result of ESDC's Disability Inclusion Action Plan. Convening mechanisms have been put in place between PHAC and ESDC (see section on engagement), and interviewees from both organizations do not see duplication in the current setting.

- Mental health and wellbeing-related projects were selected to serve areas (P/Ts or specific areas within P/Ts) with less accessible first line services. Although bridging service coverage is important, it is not clear to what extent this should be taken on by a federal public health organization.

To ensure that PHAC's funding efforts are well coordinated with the needs of autistic individuals and their families as well as funding allocated by others, there would be benefit in identifying funding priorities collaboratively with key partners and stakeholders.

PHAC's role in addressing ASD, and its role in general, is not well known by external stakeholders and the general public. This was noted as a result of interviews with external stakeholders and through an examination of requests received by PHAC, since 2018 (a hundred annually on average), from organizations and Canadians to address the lack of access to diagnosis and services across the country. According to interviewees, the development of the National Autism Strategy has raised expectations further and more clarification of roles and responsibilities for all players in addressing ASD may be needed.

OGDs play a role in addressing ASD. Their investments are described in Appendix 4.

Gaps and opportunities

The gaps that remain in addressing ASD in Canada are well documented. Many areas for action reside within P/Ts' mandates. A few gaps may be filled by PHAC, such as convening stakeholders, generating, or disseminating evidence on promising practices, enhancing ASD surveillance, and adopting Indigenous-specific approaches for NAS.

The numerous consultations undertaken on ASD over the past few years have resulted in key reports that highlight the gaps that remain to be addressed by a variety of partners and stakeholders. The PHAC-funded CAHS report as well as previous reports such as the Blueprint for a National Autism Spectrum Disorder Strategy and interviews identified several key gaps that fall outside of PHAC's mandate such as:

- delivery of diagnosis and services, which is a P/T responsibility.

- social and economic inclusion including housing, employment, financial stability, which are all P/T' and OGD' responsibilities.

- on-reserve services, which are carried out by other government departments especially Indigenous Services Canada.

Some other emerging themes listed in the CAHS report include diversity and intersectionality – to capture "how experiences of autism (and autistic identity) shape and are shaped by and through intersections with other social identities". The report invites all partners and stakeholders, including PHAC, to integrate these considerations in addressing ASD.Footnote 12

Of the gaps that remain (as noted in the above-noted reports and by interviewees), some appear to align with the federal public health role:

| Gaps | Potential alignment with PHAC's role |

|---|---|

| Limited convening mechanisms across a broad range of stakeholders for sharing updates, best practices, and better coordination of national efforts, as highlighted by several autism organizations and experts. | This is aligned with the broad PHAC mandate to "facilitate national approaches to public health policy and planning" and would be appropriate for ASD as PHAC does in other program areas. |

| Lack of support for documenting and disseminating robust evidence on implementation and impact of promising projects across Canada for encouraging uptake. Most P/Ts and NGOs not funded by PHAC are not aware of projects funded through the ASD Strategic Fund and their results. | PHAC has conducted similar activities through its Innovation Strategy and, to some extent, with some of its longer-term funding programs (e.g., HIV and Hepatitis C Community Action Fund).Footnote 13 |

| Ongoing national surveillance using health administrative data is not yet in place. | PHAC has started to lay the first building block to address this surveillance gap. For example, work is underway to develop a robust ASD case definition for prevalence and incidence estimation using health administrative data (see section on surveillance results). |

| Lack of awareness and uptake of diagnostic guidelines across the country and variability in diagnostic practices. The PHAC-funded guidelines for children were released by the Canadian Pediatric Society in 2019 but there is a limited understanding of uptake at this time.Footnote 14 | Although the delivery of diagnostics falls under P/Ts jurisdictions, PHAC might be well positioned to support 2019 guidelines dissemination and encourage uptake in collaboration with professional associations. |

| Lack of an Indigenous-specific strategy with culturally appropriate approach embedding Jordan's principle and involving Indigenous leadership. As a starting point, the CAHS advisory committee included two leaders and a researcher from Indigenous communities to ensure representation and inclusion from First Nations. | Indigenous Services Canada is better positioned to address the needs of First Nations living on-reserve and Inuit communities once the national strategy is established. However, as PHAC is leading NAS, it has committed to supporting Engagement Protocol Agreements with National Indigenous Organizations. |

| Some of the gaps identified in the CAHS report include improving autism acceptance and reducing autism-related stigma through autism education and training. | PHAC has undertaken such activities through other grants and contributions programs, such as the HIV and Hepatitis C Community Action Fund.Footnote 15 |

Key findings: Effectiveness

The ASD Program does not have its own stand-alone logic model; therefore, the evaluation used the following key documents to assess achievement of outcomes:

- ASD Initiative's ASD Strategic Fund: the Health Promotion Program's Performance Information Profile

- ASD Initiative's AIDE Canada project: outcomes as per the typical knowledge mobilization cycle

- Surveillance activities: surveillance elements as per the PHAC surveillance tool, and the outcomes identified in the Evidence for Chronic Diseases, Health Promotion and Injury Prevention Performance Information Profile

The achievements of PHAC's other ASD activities are described at the end of this section although they are not captured in any performance measurement framework.

ASD Initiative achievements

A variety of resources was added to the existing knowledge base via various community-based projects and the development of a new website to support autistic people and professionals serving them. Program participants acquired knowledge and skills either in coping with ASD or supporting clients with ASD. The short-term nature of the ASD Strategic Fund projects limited the ability to determine whether program participants improved their health behaviours. Regardless, some testimonies showed promise. Finally, the AIDE Canada project was successful in producing and gathering a variety of resources and it created knowledge hubs. There is, however, insufficient data to confirm whether outcomes were achieved.

ASD Strategic Fund: Results

The ASD Strategic Fund funded eight community-based projects in total during its first phase, from 2019-20 to 2020-21. All funded projects were successful in helping participants gain resources, knowledge, and skills (short-term outcomes); however, given the short-term nature of the projects, there was limited evidence that participants had improved their behaviours (medium-term outcome). See more details in Appendix 5.

- Among these funded projects, three of them were dedicated to improving skills and access to employment for autistic adults and reached 80 to 100% of targeted participants, although no precise targets were set beforehand. These projects provided support for employment opportunities through mentorship, training, and placements in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec, and in improved cultural awareness to support the employment of Indigenous youth in Saskatchewan. The funded projects have also worked with communities and employers to remove barriers to employment for these populations. At the end of the intervention, most responding participants confirmed that they had gained knowledge and skills to support their access to employment.

- Four projects focused on mental health and wellbeing and one project was geared towards caregiver support. They were all strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, as they were set to provide in-person services. Major adaptations, mostly toward virtual delivery, were required to support wellness through training on healthy relationships, emotional regulation, and mindfulness and regulation, or by offering dance classes and therapeutic support based on movement. Three projects have reached their targets, while the other two projects attracted fewer participants than originally anticipated (one-third and two-thirds, respectively). Through testimonies, participants indicated reduced anxiety after participating in these programs, while most caregivers increased their knowledge and skills.

- When available, data on medium-term outcomes revealed that the knowledge gained by participants could lead to beneficial behaviour changes. For example, participants enhanced their knowledge about consent and sexual readiness, which could lead to healthier relationships. They also reported gaining more coping strategies or improved mental health literacy, which could result in decreased anxiety. In addition, caregivers felt more confident to support autistic people in adopting coping strategies. For employment-related projects, potential employers felt more equipped to hire autistic people, and potential autistic employees were more ready for employment through training or mentoring. Finally, eight projects were successful in assisting some autistic participants in gaining employment.

ASD Strategic Fund: Challenges

Despite these achievements, the funding duration of projects was seen as problematic according to recipients and expert interviewees while a few challenges were identified in the area of performance measurement.

- Within the two-year timeframe, projects had to develop building blocks like contacting potential partners, consulting where appropriate, building trust with communities, developing learning resources, recruiting participants, and implementing the intervention. As explained by recipients, capitalizing on those elements to achieve potential behavioural changes, or other long-term outcomes, would take longer to achieve. This issue was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic that significantly reduced the ability to deliver in-person interventions and delayed participant enrollment, with most interventions switching to an online model.

- Post-project data collection among participants would be required to appropriately measure medium- and long-term outcomes. This is not currently possible after project completion. In addition, the few projects that attempted to collect follow-up data after the project timeframe were not able to reach enough former participants to collect reliable data.

- Although performance measurement requirements were included in application documents, some projects would have benefited from more support in planning their data collection activities and budgeting them appropriately beforehand. The limited capacity of community-based organizations to collect and analyze performance data is an important limitation to documenting project achievements.

AIDE Canada: Results

The AIDE Canada project aimed to create a single window for reliable, bilingual, up-to-date, and evidence-based information for autistic Canadians, their caregivers, and their families (Learn and Borrow tabs). AIDE Canada also gathered and developed a web page on services available across Canada (Locate tab), and it offered networking opportunities to support autistic individuals across the country with the creation of hubs in various locations.

As noted above, the project successfully developed and shared a variety of online resources; however, the evaluation was not able to assess whether its target population was able to gain knowledge and skills as a result of accessing those resources. Further, mixed evidence was found on the quality and use of AIDE's online resources. Regarding access to the online platform, web analytics data tracked by AIDE Canada was satisfactory, although inconsistencies were found in reported results. The Borrow and Learn tabs generated the most interest, with approximately 81,000 views in total, while the Locate tab was less visited with over 7,000 views.

With regards to the hubs, the pandemic delayed the activation of the hubs as well as networking events that were planned in Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal. Even though delays were experienced, some hubs (Ontario, Maritime, Northern, and Prairies) organized webinars and/or shared resources, which were viewed 935, 695, 330, and 2,650, times respectively.

AIDE Canada: Challenges

AIDE Canada's performance was affected by a few issues such as the translation of materials and the collection of performance data. More precisely, the following challenges were found:

- The translation of material on the AIDE online platform – the two platform reviews, as well interview results found an imbalance between resources in English and French. Respectively, only 5% of resources in early 2020 and 16% of resources in March 2021 found in the Learn section had a French translation available. The Learn section is now more balanced, with 93% of resources available in French as of November 2022. Nonetheless, these changes might be too recent to be noticed as potential users interviewed mentioned resources in French are lacking.

- Collecting and reporting on results – limited evidence was found on the quality and use of the AIDE online resources and hubs. The evaluation was not able to find evidence on the performance of AIDE Canada's six hubs beyond what activities were undertaken.

- The lack of reliable data about the use of online resources – a limited sample of participants from an AIDE review found the information appropriate and the Locate function useful, while service providers appreciated the 'live chat' function.Footnote 16Footnote 17Footnote 18 Those involved with AIDE interviewed for this evaluation highlighted the value of the platform for sharing knowledge while those not involved with AIDE saw more limited value in the resources developed by AIDE. They mentioned that the platform appeared to duplicate other websites, had an unfriendly search function, and there was limited mention of PHAC-funded projects. P/T interviewees, on the other hand, were mostly unaware of AIDE, except one interviewee who found the platform to be well organized.

Project sustainability

Projects were required to demonstrate the potential for sustainability in their proposal. The evaluation found that some strategies have been adopted to attract additional funding or partnerships to maintain employment-related projects. Other projects have been able to share tools and resources broadly by using strategies like online platforms and "train the trainer" approaches. Nonetheless, without being able to achieve and document medium- and long-term outcomes within the two-year funding window, recipients confirmed experiencing challenges in attracting additional funding and thus maintaining activities.

Organizations were required to demonstrate the potential for sustainability beyond PHAC funding in their proposals. The ASD Strategic Fund's definition of sustainability included the following aspects: sustaining awareness of the issue addressed in the project among decision makers and the community; sustaining programs by maintaining certain activities among one or more organizations participating in the program; sustaining partnerships by maintaining working relationships with partners and stakeholders; and sustaining impact by improving infrastructure or changing policy within organizations, for example.Footnote 19

A few projects successfully took action to ensure their sustainability beyond PHAC funding.

- Employment-related projects have developed partnerships with the private sector to sustain their activities or have received requests to share experiences in order to replicate activities. They have built business strategies with multiple partners, extended the length of employment of participants, deployed employment support specialists funded by partners to enhance placement, and developed marketing strategies aimed at potential employers.

- Other projects have used several sustainability strategies, such as developing online courses to reach their target populations at lower cost, working with partners to maintain some implementation sites, and adopting a "train the trainer" strategy. Some partners are committed to maintaining some activities beyond PHAC funding.

- The Pacific Autism Family Network, recipient of the AIDE Canada funding, undertakes ongoing fundraising activities to fund the organization and maintain some resources developed through the AIDE project. A plan to establish sustainability is currently under consideration.

Similar to measuring medium- and long-term outcomes, developing sustainability mechanisms (e.g., implementing fees) could be realistically achieved in a longer time frame than the two-year funding offered by PHAC, as noted by recipient and expert interviewees. Moreover, in the absence of robust demonstration of return on investment over a two-year period, projects are struggling to attract additional funding to sustain their activities, especially when not related to employment, as they are not partnering with the private sector. In all cases, funded projects do not appear to have reached their full potential.

Surveillance data timeliness and completeness

Canada's first estimate of ASD prevalence was released in the 2018 NASS report. However, the NASS has some limitations. CSAR has since conducted analyses using data from population-based surveys like the CHSCY and CSD and continues to evaluate the viability of health administrative data sources to complement existing survey data.

Timeliness

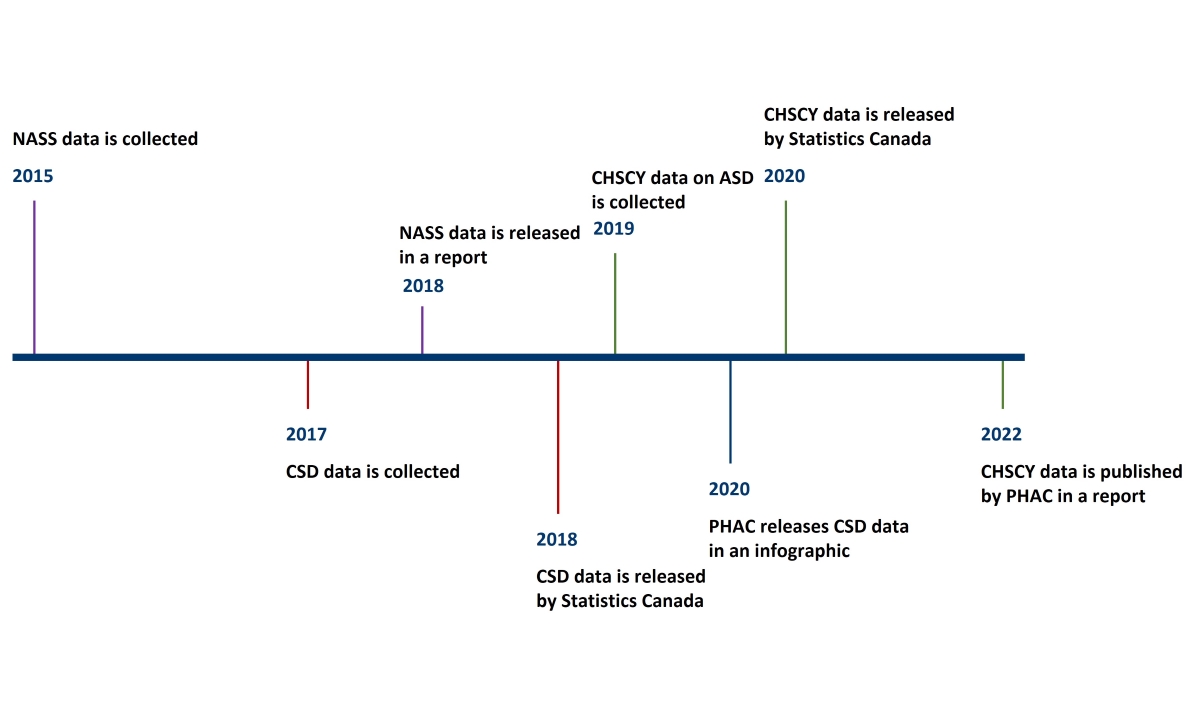

As illustrated in Figure 1 below, over the past four years, a few ASD-related data sets have been released. The most recent data available on ASD in Canada is the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY), which was collected in 2019 and released publicly by Statistics Canada in July 2020. Based on data from this survey, an ASD-focused report was developed and published by PHAC in February 2022.

Figure 1: Text description

This image provides a brief timeline of the release of ASD-related data sets from 2015 until 2022. The purple lines represent NASS data, the red lines represent CSD data, the green lines represent CHSCY data and the blue line is PHAC.

The timeline contains the following dates and descriptions:

- 2015: NASS data is collected

- 2017: CSD data is collected

- 2018: NASS data is released in a report and CSD data is released by Statistics Canada

- 2019: CHSCY data on ASD is collected

- 2020: PHAC releases CSD data in an infographic and CHSCY data is released by Statistics Canada

- 2022: CHSCY data is published by PHAC in a report.

Regular and ongoing data collection is crucial according to some internal and external interviewees. For CHSCY, external interviewees who were aware of the survey would like ASD data to be timelier as it covers all P/Ts. Nonetheless, internal interviewees consider that the frequency of ASD data collection via CHSCY is appropriate, given the depth of data collected through this general survey (see "Completeness" below).

Other countries also have partial surveillance systems with similar data delivery timing. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established a multi-source surveillance network for ASD using education and other government-administered program data sources and mostly performs prevalence projection. Estimates are available online for up to 2018, serving as an important reference in Canada.Footnote 20 In England, the National Health Service publishes figures about referrals, but not prevalence estimates.Footnote 21 The Australian Statistics Bureau provides prevalence through the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, and its most recent figures are from 2018 and were published in 2019.Footnote 22 Finally, France collects prevalence data through the National Health Data System and its most recent data was collected in 2017 and released in 2020.Footnote 23

Completeness

NASS data constitute PHAC's first attempt to measure ASD prevalence in Canada. P/T coverage in the 2018 NASS report was, however, limited to six provinces (British Columbia, all Atlantic provinces, and Quebec) and one territory (Yukon), and covered 40% of children aged 5 to 17, with other age groups excluded. Disaggregated prevalence data is available by participating jurisdictions, age, and sex-at-birth only.Footnote 24

CHSCY data complement ASD prevalence data with well-being and mental health data, co-occurring long-term health conditions, functional difficulties, and special education needs to inform public health actions. Currently, PHAC is using CHSCY data to build its evidence base and to inform, the development of the autism strategy, given that it is more up-to-date, geographically inclusive, and comprehensive than 2018 NASS report data. Although CHSCY can be used as a standalone source for ASD prevalence, it has some limitations:

- prevalence for the territories could not be reported due to small sample size

- the survey only covers children living in private dwellings

- cases are self-reported

- disaggregated data is only publicly available for sex-at-birth, age, geography and household income

A few interviewees mentioned it would be useful to have access to the other disaggregated data reported on by PHAC, even when informed that no statistical differences were found across categories.

Finally, the CSD offers a complementary data source; however, ASD cases are underestimated by design as respondents were asked to identify up to two medical conditions that cause them the most difficulty. Therefore, an individual with ASD may not identify autism as their primary or secondary condition.Footnote 25

See Appendix 6 for more details about the strengths and limitations of these data sources.

Toward national autism surveillance system data enhancement

As identified in the current program authority (as of 2021) as well as the HPCDPB Evidence Strategy for 2019 to 2022, PHAC aims to expand ASD surveillance to all P/Ts, individuals of all ages, and to provide data that will allow comparison by age groups, other socio-demographic characteristics, geographical regions, and over time.Footnote 26 Enhancement of the information technology infrastructure to support such data collection and dissemination is also part of this work.Footnote 27

Access and use of surveillance data

Stakeholders have accessed surveillance products, but more could be done to promote these products as they become available. The NASS data seem to be well known by external stakeholders; however, data limitations have been a barrier to its use, at least among P/T interviewees. Awareness of ASD-specific data from CHSCY and CSD is more limited. To date, within PHAC, national autism surveillance data has been used mainly for briefing and funding requests. There appears to be a good ad-hoc working relationship between the policy and surveillance functions, although there may be benefits to further integrating their work.

Access

PHAC has made efforts to make its surveillance products accessible over the past few years. PHAC advertised and distributed surveillance products on its website, through partner websites and networks, and in journal publications where and when relevant. Further, CSAR, in collaboration with CHP, updated the surveillance landing page on the PHAC website in April 2022.

Despite these dissemination efforts, web analytics and interviews results highlight that these resources are not reaching their target audiences to their fullest potential:

- ASD-specific CHSCY and CSD publications on PHAC web pages have generated limited visits, about 1,000 per year.

- NASS publications, available longer than CHSCY and CSD products, performed better in English. All French publications had very limited visits.

- Most external interviewees were aware of NASS data, while only a few external interviewees were aware of CHSCY data, and none mentioned CSD as a data source except a few experts. According to internal interviewees, the specific nature of PHAC's website and limited communication efforts, when compared to other products, might have limited the visibility and access of these products.

Challenges associated with dissemination and access are outlined under the Challenges sub-section below.

Use

The use of surveillance data has not been systematically measured; however, interviewees were able to provide examples of use. For instance, P/T interviewees use their own surveillance data for planning, funding requests, or cross-jurisdiction comparisons where available. P/Ts and OGDs mentioned rarely using national data. Some P/Ts look at health systems data (e.g., referrals, assessments) rather than prevalence. Finally, funding recipients use overall prevalence rates for funding requests, and experts use data for teaching.

Within PHAC, surveillance data was used mainly for briefings to the Parliamentary Secretary, the Minister of Health and the PHAC President, as well as for funding requests. CHP integrated data as it became available, such as NASS overall prevalence from its release in early 2018 to mid 2018, and then the prevalence disaggregated by gender was used for the rest of the scoping period. The CHSCY ASD-specific report was released in 2022 and, as such, it is too early to assess its use at this time.

While limited at the beginning of the scoping period, internal interviewees mentioned that interactions between the surveillance and policy teams have increased in recent years, and that discussions take place on an ad-hoc basis, such as informal information sharing on new surveillance products and inclusion of the surveillance team in P/T and recipient meetings. The two teams collaborated in 2021 to develop the "Support for Autism and Development of a National Strategy; and Diabetes Prevention, Research, Surveillance, and Development of a National Framework" proposal. Other joint work has occurred on more minor projects, such as updating the PHAC ASD web pages. However, there is no formal bilateral convening mechanisms, nor joint planning between the policy and surveillance teams, which limits the opportunity to make sure that both functions benefit from each other's work in a fully integrated way.

Challenges

A few issues have been identified as challenges with regards to the quality of surveillance data and the dissemination of surveillance products:

- Data collection methods for NASS vary across jurisdictions, which may affect difference in prevalence estimates across the country. Although PHAC relies on P/Ts' methodological choices, external stakeholders encourage PHAC to work toward convergence in methods. Other factors, beyond PHAC's range of action, may also affect difference in prevalence estimates such as: different diagnostic tools are used despite existing guidelines, varying diagnostic capacities with services not being offered or being more costly in small jurisdictions or rural or remote areas, and, families' migration across P/Ts to access services.Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30 As noted earlier in the report, surveillance activities have recently been undertaken at PHAC to address these challenges.

- External interviewees and the CAHS report highlighted the need to expand data collection to other populations such as children less than five years of age and adults and disaggregating data by age group, ethnicity, Indigenous status, and level of ASD severity, and to document developmental trajectories. The CHSCY report released in 2022 does include data on children less than five, disaggregated data by age group, and ethnicity including Indigenous status – stakeholders may not be aware of this report. The limited opportunities to disaggregate surveillance data is a common issue with other PHAC surveillance systems at the Agency.Footnote 31

- The ASD surveillance products did not benefit from a more thorough dissemination effort given PHAC's focus on COVID-19 communication activities.

Other areas

PHAC's other activity areas include knowledge transfer, guidelines and policy. The evaluation assessed the progress made by these activities. Knowledge-sharing and stakeholder engagement activities, although still at their infancy, appear to perform well. The PHAC website has been updated twice and includes recent updates on progress toward the National Autism Strategy (NAS), which generated positive and well-balanced traffic. Several convening mechanisms have recently been put in place with OGDs, P/Ts, and recipients, and the release of PHAC-funded diagnostic guidelines have filled an important gap.

Knowledge transfer

Beyond sharing leanings and evidence from community-based funding activities and surveillance, general information on ASD was shared on the PHAC website. To improve the dissemination of ASD information, PHAC updated its website twice over the scoping period, in 2018 and 2022. In the second update, language was adapted for an autistic audience and news items have been posted more frequently since then to update stakeholders and the general public on NAS and other ASD-related developments.

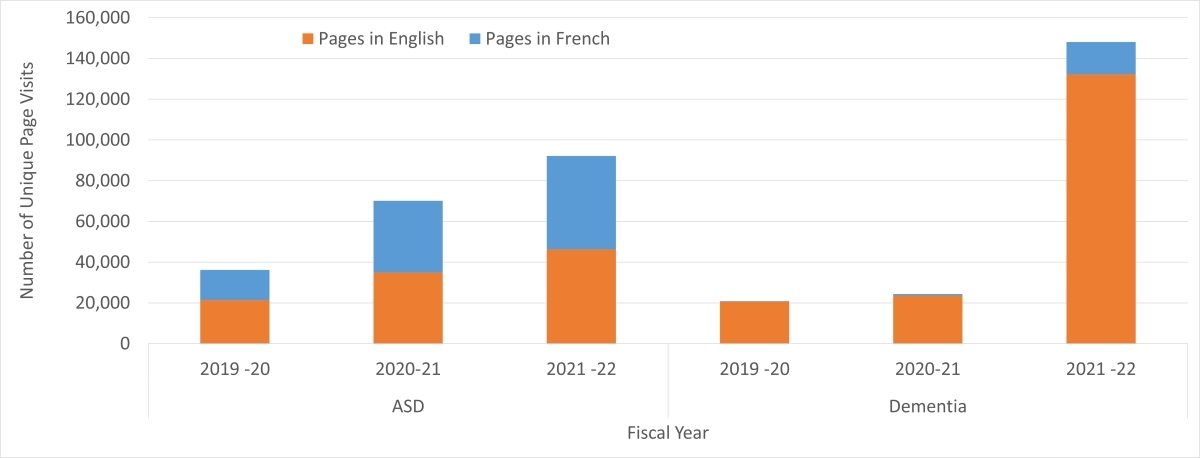

Figure 2: Text description

This figure shows a stacked bar graph displaying page views on the Government of Canada website between 2019-20 to 2021-22. It compares views of ASD-related pages (3 bars on the left) with views of Dementia-related pages (3 bars on the right). The top of each stacked bar (each year) shows the percentage of pages in French (blue) and the bottom shows the percentage in English (orange).

The number of views for ASD are as follows:

2019-20:

- Total number of unique web page visits- 36,132. 59% of those visits were on the English pages and 41% were on the French pages.

2020-21:

- Total number of unique web page visits- 70,153. 50% of those visits were on the English pages and 50% were on the French pages.

2021-22:

- Total number of unique web page visits- 92,154. 50% of those visits were on the English pages and 50% were on the French pages.

The number of views for Dementia pages are as follows:

2019-20:

- Total number of unique web page visits- 20,874. 99% of those visits were in English and 1% were on the French pages.

2020-21:

- Total number of unique web page visits- 24,310. 97% of those visits were on the English pages and 3% were on the French pages.

2021-22:

- Total number of unique web page visits- 148,127. 89% of those visits were on the English pages and 11% were on the French pages.

As shown in Figure 2, views of the ASD-dedicated pages on the PHAC website have been increasing since 2019. Dementia is a neurological condition which, unlike ASD, benefitted from the deployment of a significant communication strategy in 2019-20 at PHAC. In comparison to ASD, traffic on pages dedicated to dementia increased significantly in 2021-22 and surpassed ASD following this deployment.

Thus, traffic trends on the ASD-related pages show a strong interest from ASD stakeholders and Canadians, even though limited communication campaigns were undertaken. Moreover, within Canada, ASD pages in French account for half of all traffic over the period, which is beyond linguistic representation. The traffic on the dementia pages is much more focused on English contents, with 89% in 2021-22.

Guidelines

PHAC-funded guidelines on ASD pediatric assessments were released in 2019 by the Canadian Pediatric Society, thus filling an important gap toward more consistent diagnosis across Canada.Footnote 32 Although diagnostic practices and capacities vary across the country, the increasing trend for online access to these guidelines is encouraging.

Other comparable countries have released their ASD guidelines earlier than Canada and most of them include guidelines for adults. For example, the United States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention refers to the American Psychiatric Association guidelines, published in 2013.Footnote 33 Autism - Australian Healthcare Associates released Australia's First National Guideline in 2018Footnote 34. Finally, France's Haute Autorité de Santé released guidelines for children and youth in 2018, and the United Kingdom National Institute for Health Care Excellence released guidelines for those under 19 and for adults in early 2010, which were updated in 2017 and 2021 respectively.Footnote 35Footnote 36

Policy

Most policy activities have been focused on NAS and were put in place after the release of the 2019 Mandate Letter to the Minister of Health, requesting the development of the NAS.Footnote 37

- In 2020, PHAC established an interdepartmental committee on autism to adopt consistent approaches between ESDC, the Canada Revenue Agency, Finance Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and, more recently, Public Safety Canada. The committee has been meeting on a regular basis since February 2020.Footnote 38 Monthly calls on ASD have been taking place between senior managers from PHAC and ESDC, and an interdepartmental working group supported the conference held in November 2022 to consult stakeholders on NAS. At the same time, ESDC is leading the Interdepartmental Committee on Disability Issues to support the development of Canada's Disability Inclusion Action Plan.

- In spring 2021, PHAC initiated an FPT working group on autism, as described by internal and P/T interviews. By the fall of 2022, four meetings were held. Before that, interactions with P/Ts took place upon request.

- In January 2020, PHAC convened a meeting of funding recipients to share updates on their respective work and find potential synergies. Recipients highlighted that this meeting helped them get to know each other better and initiate collaborations.

Some NGOs and experts, as well as the Blueprint and CAHS reports highlighted the need to develop broader collaboration and stakeholder engagement mechanisms across the country in order to set common goals. None of the existing tables are currently filling this gap.

Other recent policy activities that fall within the NAS umbrella include funding the Canadian Academy of Health Science to undertake a broad consultation process to inform the NAS and convening a virtual national conference in November 2022 to bring together P/Ts and stakeholders, as well as autistic individuals and their caregivers.Footnote 39 A consultation process was also held with Indigenous communities to co-develop an Indigenous-specific ASD strategy. All external interviewees found that the PHAC-funded CAHS report engagement process that occurred in May 2022 was rigorous and well executed, with thorough consultations, and clear and complete deliverables.

Conclusions

To date, PHAC has undertaken activities to address ASD mainly through funding community-based funding and a knowledge exchange organization, as well as surveillance activities. These activities are largely well aligned with its federal public health role. Although PHAC used a social determinants of health approach to determine funding priorities for the ASD Strategic Fund, some projects did not strongly align with PHAC's mandate. For example, some projects had an employment focus, which might better fit under P/T and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) mandates. Important gaps remain and, although the majority of them fall under P/T jurisdictions, some gaps appear to align with the federal public health role in the areas of stakeholder engagement and collaboration, evaluating and disseminating promising practices, and enhancing surveillance.

Although community-based projects were short in duration, they made some advancements by increasing the knowledge and skills of program participants and, in some cases, helping autistic individuals develop coping strategies, and helping practitioners and caregivers improve support. Projects were promising but the short-term nature of funding did not allow them to reach their full potential or ensure the sustainability and scalability of operations and activities. The Autism and/or Intellectual Disability Knowledge Exchange Network (AIDE) built an online portal, and established a few networking hubs across Canada; however, there is limited evidence on the uptake of these activities.

The guidelines on pediatric assessment of ASD were released in 2019, filling an important gap in progressing toward a more consistent approach to diagnosing ASD across Canada. With regards to knowing how many are diagnosed with ASD, PHAC has made important advancements in national surveillance, including establishing reporting on indicators beyond prevalence, and expanding geographical coverage. The ongoing actions taken to address current data gaps (e.g., collecting data on all ages) will help build the evidence base required for informed decision making. Within PHAC, there are opportunities to strengthen internal decision-making once ASD data become more complete.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Ensure that gaps related to areas of greatest needs that fall within the federal public health role are addressed by PHAC in the upcoming National Autism Strategy.

The evaluation found that a few gaps in addressing ASD could be filled by PHAC given its federal public health role; however, resources are scarce. Mindful of resource availability, PHAC should focus on aligning its work with the areas of greatest need within the National Autism Strategy, while strengthening its convenor role.

This may include, but should not be limited to, clearly communicating actions that result from recent engagements, and clearly defining roles and expectations for all participants as part of the upcoming National Autism Strategy.

Recommendation 2: Enhance ASD Initiative design and performance measurement.

The short-term duration of funding did not allow community-based projects to meet their full potential. PHAC should explore the possibility of funding projects over a longer timeframe. This longer timeframe, as well as additional performance measurement requirements, would allow funded projects the opportunity to generate promising practices and then contribute to the knowledge base of 'what works' in ASD through strong impact measurement. In addition, funding priorities could be considered in collaboration with key partners and stakeholders with a focus on autistic individuals and their families.

Strong performance measurement data is critical to understanding the achievement of goals, the impact of activities on the target population, and for continuous improvement. This was absent in some projects due to the duration (e.g., the ASD Strategic Fund) or lack of planning (e.g., AIDE Canada). Strong performance measures should be defined and their collection planned at the onset of funding to ensure that it is collected throughout the project duration.

Recommendation 3: Continue to strengthen national ASD surveillance efforts with a focus on establishing internal ASD priorities and plans.

Current activities to enhance national ASD surveillance are a step in the right direction in ensuring that prevalence estimation is improved, that indicators beyond prevalence are captured, and that disaggregated data is available. That work needs to continue. As more comprehensive data becomes available, there will be more opportunities to use this data for decision making within PHAC. Both CSAR and CHP need to determine their joint ASD priorities moving forward to ensure that their short- to medium-term priorities align in their respective work plans, and to ensure that surveillance informs decision making.

Management Response and Action Plan

Recommendation 1

Ensure that gaps related to areas of greatest needs that fall within the federal public health role are addressed by PHAC in the upcoming National Autism Strategy.

Management response

Management agrees with the recommendation. The National Autism Strategy will focus on key priority areas identified in collaboration with federal partners, provinces, territories, Indigenous Peoples, and other stakeholders to address the areas of greatest need for Autistic people living in Canada, their families and their caregivers.

| Action plan for management – measures to be taken to address recommendation | Deliverable products – tangible items that will address action plan | Expected Completion Date – when deliverable products are expected to be available | Accountability – persons who have the responsibility for implementing | Resources – finances and staff needed to implement action plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Program will develop a National Autism Strategy that is informed by the discussions, collaboration and knowledge-sharing that took place at the National Autism Conference (November 15-16, 2022); along with the findings of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences' engagement activities and scientific review; and PHAC's engagement with federal partners, provinces, territories, Indigenous Peoples, families and other stakeholders. | Document to obtain policy approval of scope for a national autism strategy | October 2023 | Director General (DG), Centre for Health Promotion Vice President (VP), Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch (HPCDPB) |

$900K annually to support O&M for 7 FTEs to staff the National Autism Secretariat. Budget 2021 funding sunset in March 2023. Costs being absorbed through internal re-allocation. |

| Proposal to obtain funding for elements to be included in a National Autism Strategy | November 2023 | Director General (DG), Centre for Health Promotion VP, HPCDPB |

Additional funding of up to $75M over five years to be sought through Fall Economic Statement or Budget. | |

| Release of a National Autism Strategy | December 2023 | Director General (DG), Centre for Health Promotion VP, HPCDPB |

$900K annually to support O&M for 7 FTEs to staff the National Autism Secretariat. Budget 2021 funding sunset in March 2023. Costs being absorbed through internal re-allocation. |

Recommendation 2

Enhance ASD Initiative design and performance measurement.

Management response

Management agrees with the recommendation. Should renewed funding be identified for the ASD Initiative (i.e., ASD Strategic Fund, AIDE Canada Network), program design will be updated to include funding for projects over a longer timeframe, with strengthened performance measures to support better knowledge development, mobilization and transfer.

| Action plan for management – measures to be taken to address recommendation | Deliverable products – tangible items that will address action plan | Expected Completion Date – when deliverable products are expected to be available | Accountability – persons who have the responsibility for implementing | Resources – finances and staff needed to implement action plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The proposed scope of the National Autism Strategy will include renewal of the ASD Initiative to support action in areas aligned with PHAC's mandate and role. | Document to obtain policy approval of scope for a national autism strategy that includes renewal of PHAC's ASD Initiative |

October 2023 |

DG, Centre for Health Promotion VP, HPCDPB |

$900K annually to support O&M for 7 FTEs to staff the National Autism Secretariat. Budget 2021 funding sunset in March 2023. Costs being absorbed through internal re-allocation. |

| Proposal to obtain funding for elements to be included in a National Autism Strategy, including renewal of PHAC's ASD Initiative | November 2023 | DG, Centre for Health Promotion VP, HPCDPB |

Additional funding of $17.5M (part of the $75M request for additional resources) over five years to be sought through Fall Economic Statement or Budget. | |

| Solicitation documents for a renewed ASD Initiative that reflect strengthened program design and performance measures. | April 2024 | DG, Centre for Health Promotion VP, HPCDPB |

$900K annually to support O&M for 7 FTEs to staff the National Autism Secretariat. Budget 2021 funding sunset in March 2023. Costs being absorbed through internal re-allocation. |

Recommendation 3

Continue to strengthen national ASD surveillance efforts, with a focus on establishing internal ASD priorities and plans.

Management response

Management agrees with the recommendation.

CSAR will continue to enhance the national surveillance of ASD, with a focus on collecting data on autistic individuals of all ages, reporting on indicators beyond prevalence (i.e., demographics, diversity and equity, co-occurring conditions, diagnostic pathways and health care services, wider health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic) and including all provinces and territories. This work will involve CSAR and CHP's establishment of joint short- and medium-term priorities and plans to ensure surveillance informs decision making and vice versa. As current funding comes to an end in 2022-23, should there be an absence of additional funding, CSAR will continue to commit limited resources to advance these activities, including dedicated FTEs to lead these projects.

| Action plan for management – measures to be taken to address recommendation | Deliverable products – tangible items that will address action plan | Expected Completion Date – when deliverable products are expected to be available | Accountability – persons who have the responsibility for implementing | Resources – finances and staff needed to implement action plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PHAC's enhanced autism surveillance commitment will continue to involve two main approaches:

This work will be achieved by establishing internal priorities with our CHP colleagues as well as working closely with researchers, stakeholders, federal partners, Indigenous partners, provincial and territorial partners. |

Using the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (2019 and 2023), develop an analytic plan in preparation for the continued reporting on autism. Using the Canadian Survey on Disability (2017 and 2023), develop an analytic plan to explore potential topics related to autism. |

March 2024 | Executive Director, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research (CSAR) | Existing resources |

| Develop a summary report of the developmental work to assess the feasibility to expand the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System to include autism. | April 2024 | Executive Director, CSAR | Existing resources | |

| Develop a joint CHP-CSAR workplan that leverages existing networks and collaborations with external partners. | August 2023 | Executive Director, CSAR | Existing resources |

Appendix 1: Data collection and analysis methods

The scope of the evaluation included PHAC activities related to Autism Spectrum Disorder from April 2018 to March 2022. The evaluation was designed to address the intended outcomes of PHAC's ASD activities and provide insight on the evaluation questions.

The evaluation team collected data using various sources and methods, including:

File and Document Review

Program staff at CHP and CSAR provided documents for evaluators for review. In total, the evaluation team screened approximately 250 documents and reviewed 50 of them in detail. Information on the effectiveness of projects funded in 2021 was not available for this evaluation.

Web Analytics

ASD web analytics data was available from August 2019 to August 2022. The data measures the number of visits to ASD-related pages on PHAC's website. Each page was counted once per session, which is the time between accessing and leaving the website. Data prior to August 2019 is not stored on Health Canada or PHAC servers. Visits from outside of Canada are excluded from the results presented in the report.

Interviews

Evaluators conducted interviews with 32 individuals. This included seven interviewees internal to PHAC, nine P/Ts, seven recipients and nine other external stakeholders (OGDs and non-governmental organizations or experts). The evaluators used NVIVO qualitative analysis software to identify emerging themes from interviews.

Financial and Human Resources Data

PHAC's Chief Financial Officer and Corporate Management Branch provided financial data on planned and actual program expenditures for the evaluation period. Human resources data was also collected to document complement throughout the time period of April 2018 to March 2022.

Academic and Grey Literature

A focused review of academic and grey literature was conducted to inform evaluation findings.

Performance Measurement Data

PHAC provided performance measurement data, which the evaluation team analyzed to identify key trends and assess outcomes.

The evaluation team used triangulation to analyze data collected by these various methods in order to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions. Still, most evaluations face constraints that may affect the validity and reliability of findings.

The table below outlines the limitations encountered during evaluation, and the mitigation strategies that were put in place.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews are retrospective in nature, providing only a recent perspective on past events. | This can affect the validity of assessments of activities or results that may have changed over time. | Triangulation with other lines of evidence substantiated or provided further information on data captured in interviews. Document review also provided corporate knowledge. |

| Some interviewees were not available for interviews due to extended leave post-funding. | Some potential interviewees were unable to contribute their insight. The evaluation could be missing important views and perspectives. | Contacted other potential interviewees from the same category to ensure that there was representation from the range of stakeholders and partners that collaborates with PHAC. |

| PHAC performance measurement data was limited to a small number of indicators. | Assessment of progress towards outcomes that do not have associated performance measurement indicators can be more challenging. | Triangulation of other lines of evidence was used to provide further information where there were gaps in performance measurement |

| Financial data structure is not linked to outputs or outcomes. | There is a limited ability to assess efficiency quantitatively. | Used qualitative lines of evidence, including interviews and document reviews. |

| There was limited data related to medium- and long-term outcomes due to funding timing. | Assessment of progress towards related outcomes is challenging. | The evaluation focused on other outcome areas and used triangulation of other lines of evidence to the extent possible. |

The evaluation applied an SGBA+ lens to its assessment of the ASD program. Although official languages were not specifically examined, they were not found to be an issue for the program's activities, although the results of product page views demonstrated variations between both official languages. Furthermore, an examination of the Sustainable Development Goals was not applicable for this evaluation.

In conducting the evaluation, a single window was identified from the Centre for Health Promotion and the Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, with whom the Office of Audit and Evaluation worked closely throughout the evaluation. The scope for this evaluation was shared secretarially with the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee (PMEC) in June 2022 to help guide the evaluation questions. The final report and Management Response and Action Plan developed by HPCDPB were also presented to this committee in March 2023.

Appendix 2: Program spending and internal challenges

Program spending

PHAC's planned spending on ASD-related activities for the evaluation period was approximately $15.8 million. Note that surveillance activities only started to receive an ASD-specific budget in 2021-22 and, therefore, the budget figures do not reflect actual commitments. In terms of expenditures, for the period of 2018-19 to 2021-22, the overall variance between planned and actual spending was around 6%. The variance fluctuated over several years, with 19% of the planned budget spent in 2018-19 and 120% in 2020-21. The variances in 2018-19 and 2019-20 were related to implementation delays and funding being carried over from one fiscal year to another.

| Fiscal year | Planned spending | Actual spending | Variance | % of planned budget spent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $1,773,296 | $340,771 | $-1,432,525 | 19% |

| 2019-20 | $5,543,946 | $5,486,606 | $-57,339 | 99% |

| 2020-21 | $4,660,946 | $5,598,641 | $937,695 | 120% |

| 2021-22 | $3,858,856 | $3,422,165 | $-436,690 | 89% |

| Total CHP | $15,837,042 | $14,848,183 | $-988,859 | 94% |

| Source: Chief Financial Officer and Corporate Management Branch | ||||

Challenges hindering results

Beyond funding and other program activities, the following internal challenges might affect overall program results:

- Human resources turnover in recent years was high, especially during the pandemic (75% in 2020-21), which is something that has been experienced by other PHAC program areas. Before 2018, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) program staff were undertaking the preparatory work to build the ASD program. In 2018, an ASD-specific team was created. Internal interviewees indicated that the team has been affected by high turnover and assignments during the pandemic and has been rebuilt since then. This has led to delays in requesting funding to advance the NAS. Recipients and experts have also noticed that turnover was an issue when interacting with PHAC. Recent efforts have been made to build or rebuild relationships with stakeholders.

- As a result of staffing changes and fluctuations, program historical knowledge is limited, and new staff have difficulty accessing relevant information and files to build upon the work done by former staff. The current team is making efforts to change these practices.

The COVID-19 experience has taught some lessons in terms of preparedness across PHAC. To face more uncertain and demanding times, it is important to have program documentation and corporate knowledge organization beforehand in order to ensure continuity, even in case of high staff turnover or understaffing. Having processes in place to monitor that commitments and requirements are fulfilled, regardless of program team composition, is crucial to ensure proper file management.

Appendix 3: Autism strategy and surveillance history

Building a National Autism Strategy

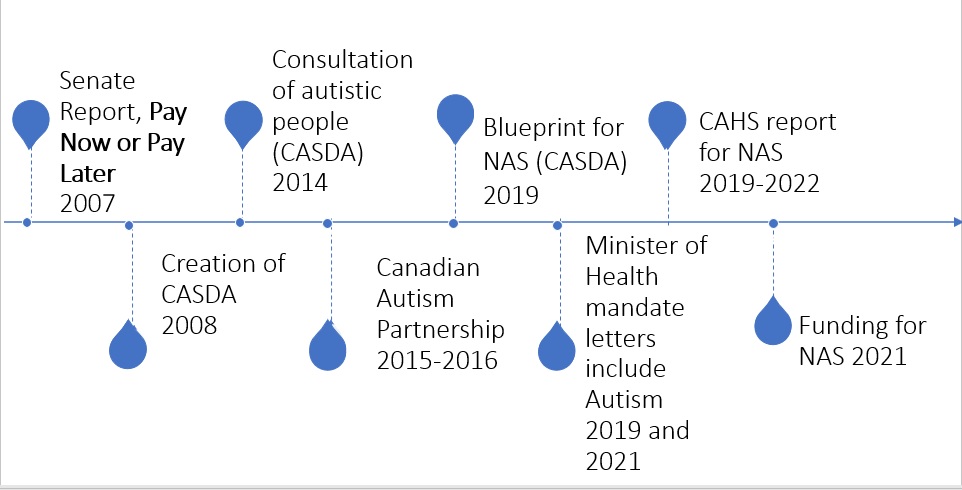

The National Autism Strategy has been in the making for almost ten years, as shown in the timeline below. Stemming from the Senate Committee's report "Pay Now or Pay Later: Autism Families in Crisis", the Autism Alliance of Canada, previously called the Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorder Alliance, conducted a needs assessment and consultations, which served as key sources of information for the development of the 2019 "Blueprint for a National Autism Spectrum Disorder Strategy". The strategy was developed to inform the federal government of national ASD needs and proposed areas of actions.Footnote 40

Following the release of the Blueprint, the federal government identified the development of a national ASD strategy as a key priority via the Minister of Health's mandate letter. PHAC initiated work in 2020 by providing funding to the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS) to lead an evidence-based national engagement process to inform the development of NAS.

Figure 3: Text description

This image provides a brief timeline of the development of the National Autism Strategy. The timeline contains the following dates and descriptions:

The timeline contains the following dates and descriptions:

- 2007: Senate report, Pay Now or Pay Later

- 2008: CASDA Creation

- 2014: Consultation of autistic people (CASDA)

- 2015-2016: Canadian Autism Partnership

- 2019: Blueprint for NAS (CASDA)

- 2019 and 2021: Minister of Health (MoH) mandate letter include Autism

- 2019-2022: CAHS report for NAS

- 2021: Funding for NAS

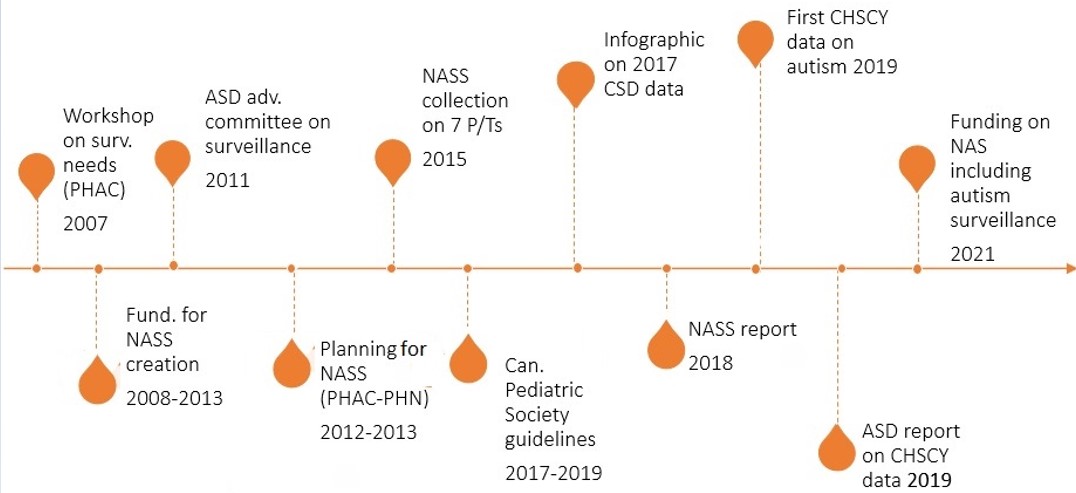

Building the ASD surveillance system

PHAC has been working on an ASD surveillance system since 2007 when it conducted a workshop with clinicians and researchers to assess the need for an ASD surveillance system, as shown in the timeline below. Shortly after, in 2008, initial funding was allocated to PHAC to develop the surveillance system, which would be focused on children and youth autism rates. PHAC collaborated with partners and stakeholders over the next few years to build the NASS.