Evaluation of PHAC’s Community Action Program for Children (CAPC) and Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP) - 2015-16 to 2019-20

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.43 MB, 46 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: March 2021

Prepared by

The Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

March 2021

Table of contents

- Executive summaryid="exe1.0"

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Evaluation Scope and Methodology

- 2.0 Program Profile

- 3.0 Integration with Provinces and Territories

- 4.0 Program Reach and Benefits

- 5.0 Efficiency of Program Delivery

- 6.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A – Evaluation Scope and Methodology

- Appendix B – CAPC and CPNP Logic Model

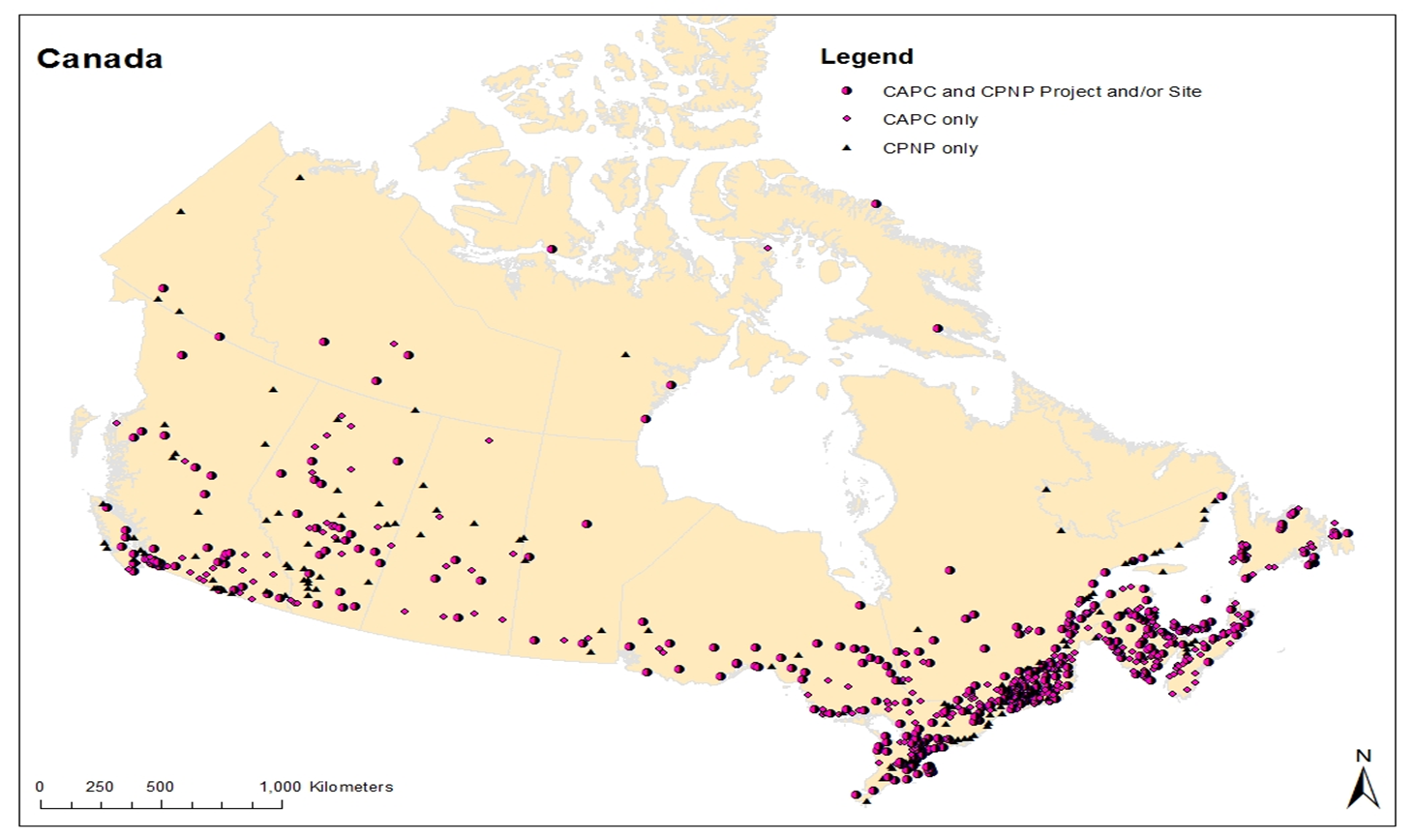

- Appendix C – CAPC and CPNP Projects across Canada

- Appendix D – CAPC and CPNP Roles and Responsibilities

- Appendix E – Salary and O&M Spending

List of Acronyms

- CAPC

- Community Action Program for Children

- CGC

- Centre for Grants and Contributions

- CPNP

- Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program

- DCY

- Division of Children and Youth

- ELCC

- Early Learning and Child Care

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- G&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- HPCDPB

- Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch

- JMC

- Joint Management Committee

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

Executive Summary

This report presents findings from the evaluation of the Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) Community Action Program for Children (CAPC) and the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP). The evaluation examined the CAPC and CPNP's activities from April 2015 to August 2020.

PHAC plays a long-standing role in supporting the health of young children and pregnant individuals, particularly for segments of the population that are considered to be at risk, as they face health inequities and other barriers to accessing health and social services. This role includes a range of health promotion activities led by PHAC's Division of Children and Youth, including:

- providing national policy guidance, information, and advice on the health of infants, young children and their families, as well as pregnant individuals;

- providing leadership within the federal government on key prenatal, child, and family-related health and wellness issues;

- funding community-based organizations that develop and deliver comprehensive intervention and prevention programs; and,

- encouraging partnerships within communities to strengthen capacity and to increase support around healthy pregnancies and early childhood development.

Between 2015-2016 and 2019-2020, PHAC spent approximately $82.5 million per year for these activities. Most program expenditures were associated with the grants and contributions provided to community organizations through the Community Action Program for Children (CAPC) and Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP) for community-level maternal and child health projects across Canada.

Key Findings

Integration with Provinces and Territories

The CAPC and CPNP complement provincial and territorial programs with minimal to no overlap or duplication. This complementarity has supported a wraparound approach to service provision across different jurisdictions, as well as greater opportunities for collaboration, referral and providing families with more holistic programming. However, the level of complementarity between the CAPC, CPNP, and provincial and territorial programs varies across Canada and was perceived by some internal and external key informants as contingent on the priorities of provincial and territorial governments, which may affect the number and types of programs offered and the level of collaboration and coordination across jurisdictions.

The Joint Management Committees (JMC) between PHAC and provincial and territorial governments play an important role in coordinating programming that is focused on reducing health inequities, and supporting prenatal health and early childhood development. Currently, not all JMCs are being used to their full potential due to various challenges including competing demands on member's time and changing government priorities. There are opportunities to enhance the role of the JMCs through strengthened communication between JMCs, as well as between the JMCs and the Division of Children and Youth to support broader coordination of priorities and policies.

Program Reach and Benefits

The majority of CAPC and CPNP projects are reaching the target populations measured by PHAC, and the majority of CAPC and CPNP projects and satellite sites are located in communities with socio-economic or school readiness vulnerabilities. Additionally, most participants experienced positive benefits from attending a CAPC or CPNP project including gaining knowledge and skills, and improving their health behaviours, health, and wellbeing. The type, frequency and duration of programming as well as the extent to which participants had a positive experience with a projectinfluenced the extent to which they achieved these results. CAPC and CPNP projects play an important role in addressing the ongoing and fundamental needs of their participants to support prenatal health and early childhood development.

However, key informants perceived the needs and challenges experienced by program participants as becoming increasingly complex, and CAPC and CPNP project staff may not always have the capacity and training to address adequately these complex needs, especially when they are outside the scope of program objectives. Moreover, results from the 2018 CAPC and CPNP participant surveys suggested that some participants do not identify with one or more target populations, and the findings from a recent environmental scan indicated that some projects and satellite sites might be located in communities that are not faced with socio-economic or school readiness vulnerabilities. Consequently, there are opportunities to explore the full range of target populations reached by the programs and to identify and address potential gaps in terms of program reach.

The COVID-19 pandemic was an additional factor that has amplified the challenges experienced by participants and limited the extent to which projects could provide the required support.

Several opportunities for PHAC to further inform and support CAPC and CPNP programming were identified in the evaluation. These include strengthening communication between the CAPC and CPNP and other programs situated within PHAC's Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch (HPCDPB), as well enhancing PHAC's leadership role in facilitating and coordinating the development and sharing of knowledge and capacity building resources across funded projects and with program stakeholders.

Efficiency of Program Delivery

CAPC and CPNP are managed under a centralized model with three branches involved in the administration and management of the programs. Recent efforts have been made through the development of a Program Charter and an integrated work plan to further clarify roles and responsibilities across these three branches to improve the efficient administration and management of the programs.

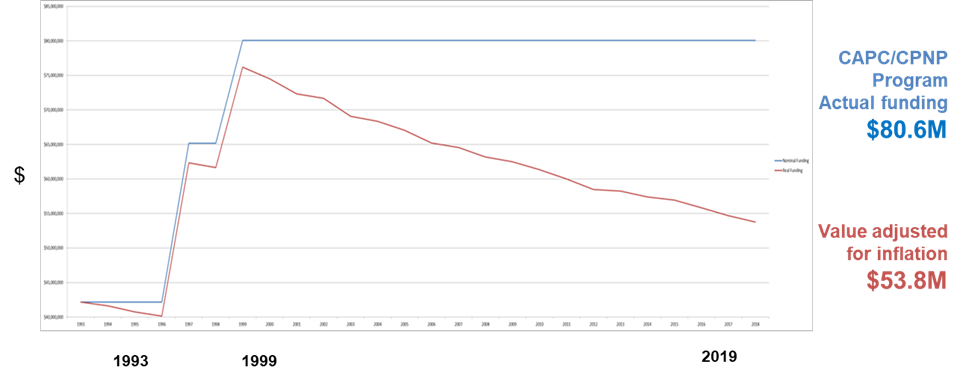

Some of the benefits of the current CAPC and CPNP delivery model noted in the evaluation were that it provides projects with the flexibility to tailor activities to meet the needs of their participants, and has allowed them to leverage additional funding and in-kind resources from other sources (e.g., provincial government). The evaluation also found that the ability of CAPC and CPNP projects to offer a full complement of activities and programs is being impacted due to twenty years of static funding, which has resulted in a situation where projects have 33% less purchasing power when adjusted for inflation. To address this issue, as well as constraints stemming from a closed solicitation process, it was suggested that PHAC explore alternative funding approaches while recognizing the longstanding integration of these programs in their communities, as well as contextual differences across the regions, provinces, and territories.

Recommendations

Findings discussed in this report led to the identification of three recommendations to help ensure that CAPC and CPNP continue to generate positive changes for program participants, meet participant and stakeholder needs, and support PHAC's objectives.

Recommendation 1:

1. In the context of the upcoming renewal of the CAPC and CPNP, the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch should review program objectives to ensure they continue to be relevant, and address the needs of target populations. As part of this review, it is recommended that the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch consider ways to strengthen and improve information sharing amongst stakeholders and partners, and better integrate this as a key activity for funded projects.

Over the past 25 years, the CAPC and CPNP programs have remained relatively stable. Evidence has shown that the needs of at-risk pregnant individuals, children and families are complex. Additionally, data suggests that the CAPC and CPNP may not always be reaching target populations. However, it is possible that the demographic characteristics and needs of at-risk pregnant individuals and families with young children have shifted in the last 25 years and no longer align with PHAC's original target populations and program objectives.

The objectives and reach of the CAPC and CPNP have been longstanding issues for these programs. In 2010, the evaluation of the CAPC recommended a review and identification of the program's core objectives, while the 2015 evaluation of the CAPC and CPNP recommended the exploration of opportunities to optimize program reach. As such, program renewal represents an opportune time to examine program objectives and consider the populations who would benefit most from the CAPC and CPNP. It is also an opportunity to clarify PHAC's role with respect to supporting prenatal nutrition and early childhood development. In undertaking this work, the program should leverage results from the recent environmental scan and other work conducted to understand the reach of the CAPC and CPNP, in order to find ways to optimize program reach and respond most effectively to the needs of target populations.

As part of the review of the CAPC and CPNP objectives, the HPCDP branch should build upon their knowledge development and exchange strategic plan and consider ways to strengthen and enhance PHAC's roles and responsibilities regarding resource development and information sharing. Findings from the evaluation show that CAPC and CPNP projects would benefit from enhanced knowledge sharing and resources, in that they would assist them in addressing the complex needs of participants.

Recommendation 2:

2. Based on the decision taken with respect to program objectives, the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch should examine alternative program delivery model(s) that would optimize program reach and best enable the achievement of the established program objectives.

Under the current program delivery model, CAPC and CPNP projects have demonstrated an ability to support participants in achieving positive changes. However, static funding and a closed solicitation process have limited the extent to which the programs and funded projects are able to reallocate funds in response to participants' needs. This may create situations of inequity regarding the types of organizations funded and families served. By considering alternative delivery models, PHAC may discover opportunities to continue to support prenatal health and early childhood development programming within community-based organizations, while offering the flexibility to respond to emerging needs of at-risk populations. Such considerations should also reflect the objectives and target populations of the two programs.

Recommendation 3:

3. The Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch should examine opportunities to strengthen communication and coordination with the Joint Management Committees on investments related to supporting the health of at-risk pregnant individuals, as well as young children and their families.

While the Joint Management Committees (JMC) are intended to facilitate stronger working relationships between PHAC and provincial and territorial governments, evaluation findings indicate that not all JMCs are currently used to their full potential. Opportunities remain to enhance the engagement of the JMCs in activities and decisions related to CAPC and CPNP programming. In particular, including the JMCs in discussions and decisions around the CAPC and CPNP objectives, identification of target populations and potential alternative delivery models may support broader coordination of priorities and policies between the jurisdictions in an effort to ensure continued complementarity of programming.

Management Response and Action Plan

| Recommendations | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables |

Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

Recommendation 1: In the context of the upcoming renewal of the CAPC and CPNP, the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch should review program objectives to ensure they continue to be relevant and address the needs of target populations. As part of this review, it is recommended that the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch consider ways to strengthen and improve information sharing amongst stakeholders and partners, and better integrate this as a key activity of funded projects. |

Agree | 1.1 The Program will conduct a review of program objectives that will include:

|

1.1 "What we Heard" Report of Recipient, JMC and Other Key Stakeholders Engagement Processes on Program Objectives and Current Target Population Needs | 1.1 October 1, 20210 |

Director General, Centre for Health Promotion |

1.1 Existing resources |

1.2 The Program will examine ways to strengthen and improve information-sharing and knowledge exchange through activities that will include:

|

1.2 New CAPC/CPNP Program Framework (s) including renewed objectives, priority populations, principles, and program performance measurement framework | 1.2 May 1, 2022 | 1.2 O&M $70,000 |

|||

Recommendation 2: Based on the decision taken with respect to program objectives, the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch should examine alternative program delivery model(s), that would optimize program reach and best enable the achievement of the established program objectives. |

Agree | 2.1 The Program will review and analyze alternative program delivery models that will include:

|

2.1 Internal Report to senior management providing advice on program delivery model options to strengthen and improve program delivery | 2.1 December 1, 2021 |

2.1 Director General, Centre for Health Promotion |

2.1 Existing resources |

2.2 The Program will engage JMCs regarding ways to strengthen communication and coordination that will include:

|

2.2 Solicitation documents that reflect the recommended program delivery model | 2.2 June 1, 2022 | 2.2 Director General for Centre of Grants and Contributions |

2.2 O&M $20,000 |

||

Recommendation 3: The Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch should examine opportunities to strengthen communication and coordination with the Joint Management Committees on investments related to supporting the health of vulnerable pregnant women, as well as young children and their families. |

Agree | 3.1 The Program will engage JMCs regarding ways to strengthen communication and coordination that will include:

|

3.1 Updated Terms of Reference 3.2 JMC Strategic Plan(s) |

3.1 January 31, 2022 3.2 April 1, 2022 |

3.1 Director General, Centre for Health Promotion 3.2 Director General Health Security and Infrastructure Branch |

3.1 Existing resources 3.2 O&M $20,000 |

1.0 Evaluation Scope and Methodology

This report presents findings from the evaluation of the Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) Community Action Program for Children (CAPC) and Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP). The evaluation examined the CAPC and CPNP's activities from April 2015 to August 2020. Areas examined include how the CAPC and CPNP fit within the broader context and work of the provinces and territories, program benefits and how they responded to the needs of participants, as well as the efficiency of program delivery. In the wake of the global pandemic, the evaluation also examined how COVID-19 affected the programming of funded CAPC and CPNP projects, and the needs of participants.

Data was collected from a review of literature, program documents, performance measurement data and financial information, as well as from a comparative analysis. Data was also collected during 50 key informant interviews with CAPC and CPNP management and staff, program stakeholders, partners, funding recipients and other organizations providing prenatal and early childhood programming. Data was analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different lines of evidence listed above, with the intention of increasing the reliability and credibility of evaluation findings and conclusions. See Appendix A for further details on the evaluation scope and methodology.

2.0 Program Profile

2.1 Inequities during pregnancy and early childhood

The period from pregnancy to early childhood (i.e., 0 to 6 years of age) is a critical stage for development as the brain undergoes significant changes that lay the foundation for future health and wellbeingFootnotenote 1. As such, health, social, economic and environmental inequities experienced during pregnancy and early childhood can have negative impacts that persist throughout the course of an individual's life. In 2018, approximately 1.4 million children aged five and under lived in CanadaFootnote 2, many of whom faced developmental risks because of inequities experienced while in utero or during early childhood. In particular, more than one quarter (28%) of Canadian children experienced difficulties in at least one area of development prior to beginning grade oneFootnote3. Areas of development include physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

Research shows that approximately one quarter of Canadian kindergarten children are at risk in at least one area of development prior to entering Grade 1Footnote 4. Such risk conditions can predict literacy and numeracy outcomes throughout childhood and are connected with adverse health and social outcomes in later life, such as chronic disease, poor mental health and lack of economic participationFootnote 5. These risk conditions are more prevalent among certain subpopulations including children who live in low-income neighbourhoods, who identify as Indigenous, who live in rural and remote areas, who live in neighbourhoods with a high proportion of foreign-born residents, or who live in neighbourhoods with lower overall educational attainmentFootnote 6. Additionally, low birth weight is a contributing factor to children being at risk in certain areas of development, as babies born with low birth weight are at higher risk of developing

physical, cognitive and behavioural problemsFootnote 7. Studies have demonstrated correlations between low birth weight and parents that live in low-income neighbourhoods or have lower educational attainmentFootnote 8.

Early investments in programming that supports prenatal health and early childhood development can help address long-term health, social, economic and environmental inequities and bring about the greatest return on investment. For instance, a recent Canadian study found a return on investment of $4.5 in adult social services in adulthood for every dollar invested in early childhood developmentFootnote9. Furthermore, at a societal level, interventions focused on supporting early childhood development have been linked to economic growth and prosperityFootnote10.

2.2 CAPC and CPNP

In recognition that investing in children, including during the prenatal and postnatal periods, is fundamental in reducing health inequities and poor health outcomes in the long term (e.g., chronic disease), the federal government implemented the CAPC in 1993 and the CPNP in 1995. Through contribution agreementsEndnotei, these programs provide funding to community-based organizations that develop and deliver comprehensive intervention and prevention programs. PHAC funds approximately 400 CAPC projects serving over 230,000 at-risk children parents, and caregivers, as well as approximately 240 CPNP projects serving over 45,000 pregnant or post-natal individuals, as well as other parents and caregiversEndnoteii. Funding is proportionately distributed geographically across Canada and decisions regarding which projects received funding were made based on protocol requirements and recommendations agreed upon by the federal, provincial and territorial governments, in order to ensure that projects address regional and local needs. While most contribution agreements are managed between PHAC and the funding recipient, the province of B.C. employs a coalition model for the CAPC whereby PHAC enters into contribution agreements with host agencies, who in turn enter into third party agreements with community-based organizations (i.e., coalition members) responsible for delivering CAPC projects.

CAPC provides funding to community groups that promote the healthy development of young children from birth to age six, who face challenges that put their health at risk. In particular, the program provides funding to address the needs of young children who are at risk including, but not limited to children living in low-income families, children living with teenage parents, children experiencing developmental delays, social, emotional or behavioural problems, as well as abused or neglected children. CAPC also supports on a priority basis off-reserve Indigenous children, racial minority and refugee children, children living in remote or isolated communities, and children in lone parent families. Projects funded through the CAPC offer programming tailored to local community needs (e.g., parenting programs, nutritional support and collective kitchens), resources, and referrals to support the adoption of positive health behaviours and building protective factors in areas such as early child development, nutrition and healthy eating, mental health and wellbeing, positive parenting, physical activity, child health and safety, and immunization. CAPC projects are delivered in communities of all sizes, with some projects serving multiple communities. In particular, approximately three quarters of projects (76%) serve urban communities, while almost a fifth of projects (19%) operate within rural areas. Very few projects are delivered in remote (4%) or isolated areas (2%)Endnoteiii. See Appendix C for a map that outlines the locations of the CAPC projects across Canada.

The CPNP provides funding to community groups to help to improve the health of pregnant individuals, as well as new parents and caregivers, and their babies, who face challenges that put their health at risk, such as: poverty, teen pregnancy, social and geographic isolation, substance use and family violence. CPNP-funded projects provide resources, programming and referrals that focus on the health and wellbeing of pregnant individuals and new parents in areas such as breastfeeding, nutrition, prenatal care, infant care, and mental health. CPNP projects may be delivered in multiple communities. The majority of projects (72%) are delivered in urban communities, while just under one quarter of CPNP projects (22%) are available in rural areas. Very few projects deliver activities in remote (3%) or isolated areas (3%). See Appendix C for a map that outlines the location of the CPNP projects across Canada.

In addition to funding community-based projects, the Division of Children and Youth undertakes various activities to address health inequities during pregnancy and early childhood at a national level including:

- providing policy guidance, information, and advice on the health of infants, young children and their families (e.g., breastfeeding, parenting, substance use during pregnancy);

- promoting the creation of partnerships within communities to strengthen capacity and to increase support around healthy pregnancies and early childhood development; and

- providing leadership within the federal government on key prenatal, child and family-related health and wellness issues and working with other federal departments to advance issues of common interest, such as child development.

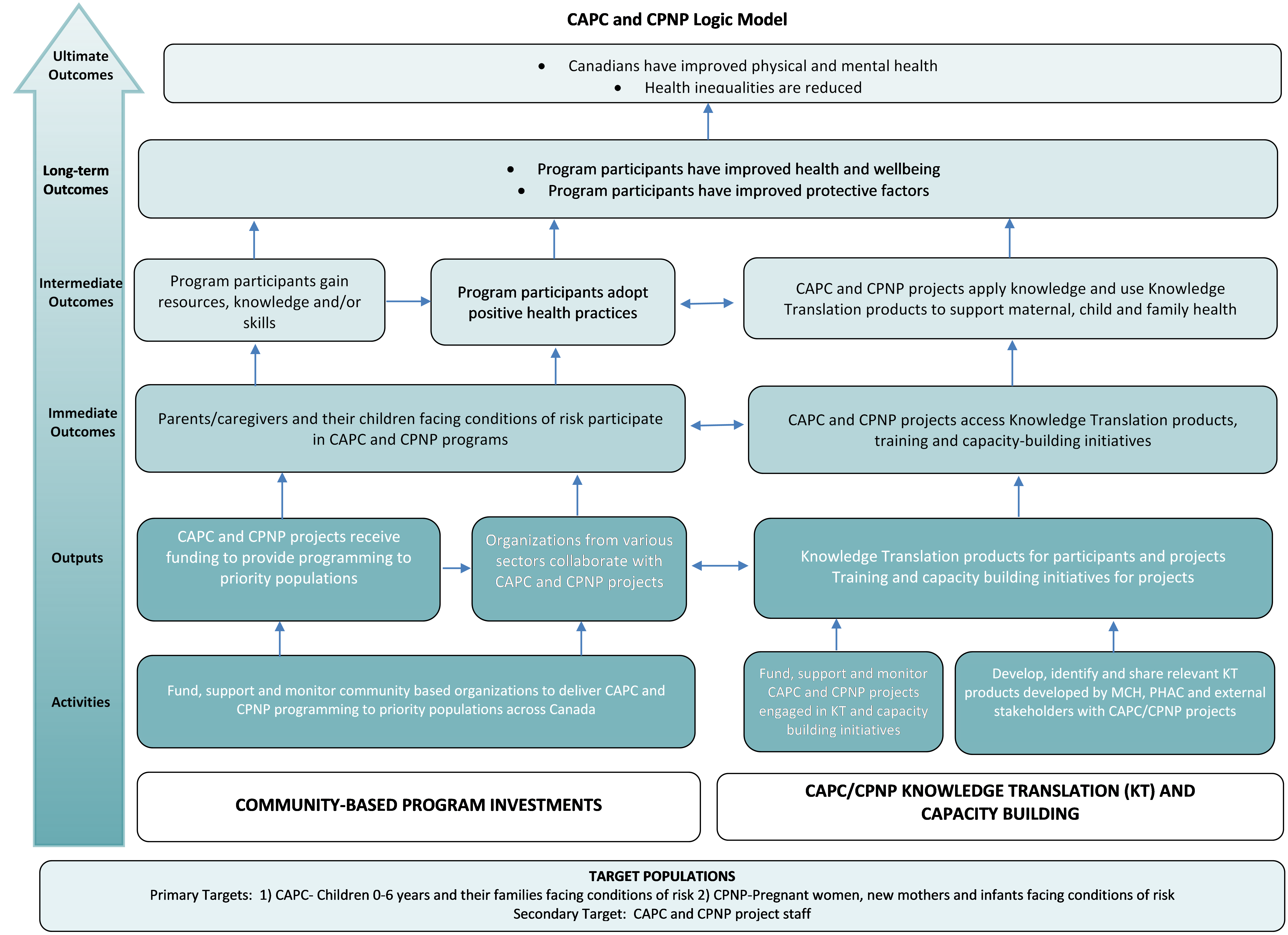

The activities of the CAPC and CPNP align with PHAC's mandate and role of supporting Canadians in the improvement of their mental and physical health, as well as the Government of Canada's role in promoting child wellbeing.

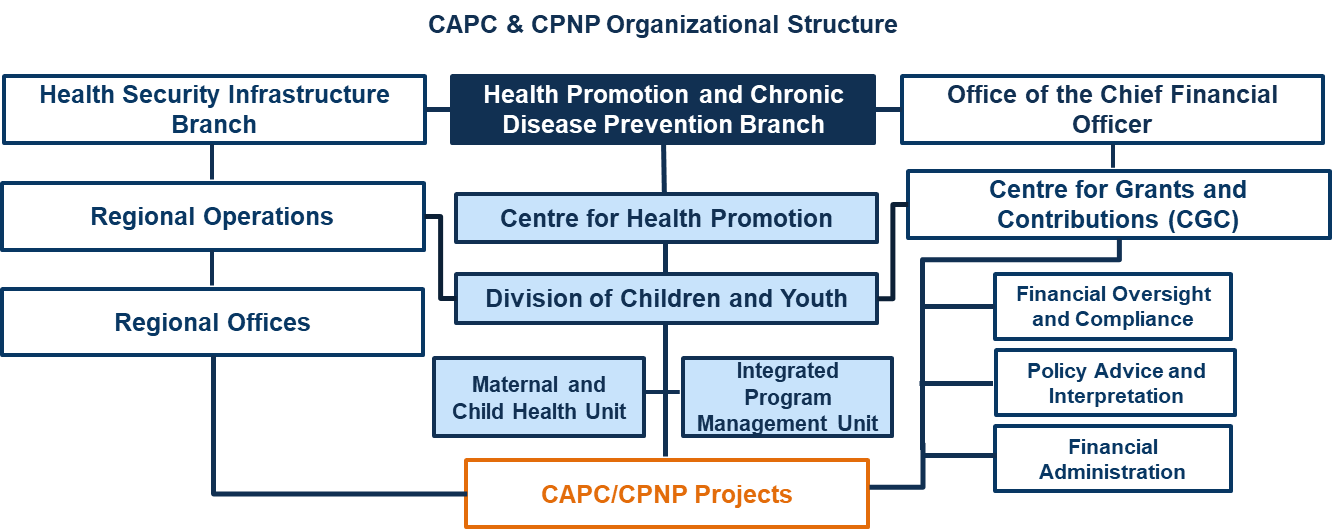

As illustrated in Figure 1, CAPC and CPNP activities are supported by PHAC's Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch (HPCDPB), Health Security and Infrastructure Branch (HSIB) and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) (see Appendix D for a description of their roles and responsibilities).

Figure 1: Organizational Structure of the CAPC and CPNP

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

Figure 1 presents an organizational structure of organizations with PHAC involved in carrying out the activities related to CAPC and CPNP projects. As illustrated, CAPC and CPNP activities are supported by PHAC's Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch (HPCDPB), Health Security and Infrastructure Branch (HSIB) and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO)

Within HSIB, Regional Operations and Regional Offices are involved. Within HPCDPB, under the Centre for Health Promotion's Division of Children and Youth there are two teams involved: Maternal and Child Health Unit and the Integrated Program Management Unit. Finally, under the OCFO, within the Centre for Grants and Contributions there are three teams involved: Financial Oversight and Compliance; Policy Advice and Interpretation; and Financial Administration.

2.3 Program Budget

Between 2015-2016 and 2019-2020, PHAC's annual budget for the CAPC and CPNP was approximately $81.8 million a year, as presented in Figure 2 below. The grants and contributions budget for the CAPC and CPNP remained stable throughout the evaluation period and there were minimal changes in the salary, and the operations and maintenance (O&M) budgets for both programs.

| Year | CAPC - G&Cs Budget |

CPNP – G&Cs Budget |

CAPC and CPNP – Salary Budget |

CAPC and CPNP – O&M Budget |

CAPC and CPNP –Total Budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2016 | $53,400,000 | $27,189,000 | $997,759 | $274,300 | $81,861,059 |

| 2016-2017 | $53,400,000 | $27,189,000 | $902,191 | $306,776 | $81,797,967 |

| 2017-2018 | $53,400,000 | $27,189,000 | $888,030 | $282,613 | $81,759,643 |

| 2018-2019 | $53,400,000 | $27,189,000 | $908,983 | $285,113 | $81,783,096 |

| 2019-2020 | $53,400,000 | $27,189,000 | $899,501 | $311,797 | $81,800,298 |

| Total | $267,000,000 | $135,945,000 | $4,596,464 | $1,460,599 | $409,002,063 |

Source: PHAC Office of the Chief Financial Officer |

|||||

3.0 Integration with Provinces and Territories

3.1 Complementary Programming

The CAPC and CPNP largely complement provincial and territorial programs with the latter focusing on the general population, while PHAC offers programming to Canadians that identify with specific socio-demographic characteristics.

In Canada, the constitutional responsibility for children is shared between multiple levels of government as "Canada's various Constitution Acts do not assign the subject of children to either level of government"Footnote11. In recognition of this shared responsibility, as well as international commitments such as the United Nations' Convention on the Rights of the ChildFootnote12, the CAPC and CPNP were developed and implemented in consultation and collaboration with provincial and territorial governments to facilitate complementarity between jurisdictions. Moreover, in some cases provincial programs were specifically designed to complement the CAPC and CPNP. In particular, many provincial or territorial programs providing supports or programming that tend to target the general population, or specifically children with disabilities, whereas the CAPC and CPNP target specific at-risk populations of pregnant individuals and young childrenEndnoteiv.

A review of provincial and territorial programs suggests that the CAPC and CPNP generally complement provincial or territorial programs with minimal to no overlap or duplication. Several internal and external key informants corroborated the findings from the review of provincial and territorial programs, stating that there was minimal overlap or duplication. According to some internal and external key informants, when provincial or territorial programs do target the same populations, it is often in communities where there are no CAPC or CPNP projects, to avoid duplication of services. For instance, the Government of Manitoba created the Healthy Baby program to provide prenatal support in areas without a CPNP project and ongoing services for parents and infants that graduate from the CPNP program to support continued post-natal care. It was further noted that complementarity between federal and provincial or territorial programs allows CAPC and CPNP projects to focus on addressing the needs of Canadians that identify with specific socio-demographic characteristics. Consequently, several internal and external key informants identified a role for both levels of government, with the CAPC and CPNP filling a gap in services by concentrating on providing services to segments of the population with specific needs that are often difficult to reach and that may benefit from tailored programming.

Several provinces and territories also offer complementary services for the same target populations as the CAPC and CPNP, which supports a wraparound approach to service provision. For instance, some projects in Alberta leverage services offered by the province (e.g., prenatal screening) to support their participants. Additionally, program documents and key informants indicated that when CAPC and CPNP projects are co-located with complementary provincial or territorial programs, there is less chance of duplication of services and greater opportunity for collaboration, referral, and providing families with more holistic programming.

The level of complementarity between the CAPC, CPNP, and provincial and territorial programs varies across Canada. Some internal and external key informants indicated that the level of complementarity was contingent on the priorities of provincial and territorial governments, which may affect the number and types of programs offered and the level of collaboration and coordination across jurisdictions.

3.2 Joint Management Committees

Joint Management Committees (JMCs) played an important role in facilitating the operation of CAPC and CPNP projects across Canada. However, not all JMCs are being used to their full potential, which limits information sharing and the coordination of programs between different levels of government.

According to internal program documents, to ensure that the CAPC and CPNP "complement and [do] not duplicate or reduce the responsibilities of other programs"Footnote13 and to facilitate the operation of funded projects across the country, Joint Management Committees (JMC) were implemented in each province and territory. The JMCs are composed of representatives from PHAC and from the respective provincial or territorial government. They may also include CAPC and CPNP funding recipients and stakeholders. Every JMC has a protocol agreement that outlines the purpose, priorities, management, evaluation, and funding commitments as agreed upon by each jurisdiction. These protocol agreements were last renewed in 1995 when they were amended to include the CPNP in addition to the CAPC.

Several external and some internal key informants highlighted the crucial role played by JMCs in supporting PHAC's efforts to determine whether CAPC and CPNP projects are located in communities with the greatest need for services. The mandate of these committees is to facilitate stronger links between jurisdictions, including information sharing, identifying needs, gaps, and other trends, and supporting access to data on healthy pregnancies and early childhood development. For instance, the Newfoundland and Labrador JMC meetings focused on information sharing including best practices, reviewing performance measurement information, and engaging with stakeholders with a focus on building capacity across the province.

However, not all JMCs are perceived as being used to their full potential, resulting in reduced occasions for strategic coordination and collaboration. In particular, key informants from two provinces noted that their respective JMC used to be very strong, but participation and collaboration by the members has significantly dropped in the last few years, which limited the quality and breadth of information sharing and program coordination. Additionally, a few internal key informants noted that the JMCs in the territories are less formal and meet as needed to share information about CAPC and CPNP. In B.C., the JMC is not currently active and CAPC and CPNP items are brought to the province's Office of the Early Years table for discussion. However, there are plans to re-establish the JMC in B.C. during the 2021-2022 fiscal year.

Varying activity levels among the JMCs were noted in the previous evaluation of the CAPC and CPNP, as well as the 2015 internal Audit of Maternal and Child Health ProgramsFootnote14, which recommended that the terms of reference for JMCs be updated to reflect their changing roles and responsibilities, in an effort to support active engagement across all committees. The terms of reference for the JMCs were updated in 2018. While the revised terms of reference may have provided clarification on the JMCs' mandate, there are additional factors that challenge the work and impact of these committees. According to some internal and external key informants, challenges with respect to the JMCs include, but are not limited to member turnover, increasing demands on member's time, changing government priorities, and a reduced focus on the renewal process.

Key informants indicated that there are opportunities to improve the work of the JMCs, and to enhance communication between the JMCs, as well as between the JMCs and PHAC's Division of Children and Youth (DCY), to support broader coordination of priorities and policies. Such opportunities were also noted in the previous CAPC and CPNP evaluation.

4.0 Program Reach and Benefits

4.1 Reaching Target Populations

The majority of CAPC and CPNP projects reached their target populations and CAPC and CPNP projects and satellite sites are primarily located in communities where there are socio-economic or school-readiness vulnerabilities.

In 2018, PHAC conducted a survey with parents and caregivers participating in CAPC projects, as well as participants in CPNP projects, with the intention of gaining a better understanding of the extent to which these programs reach target populations and help participants achieve positive results. Approximately 9,410 CAPC participants and 3,916 CPNP participants completed each program's respective survey.

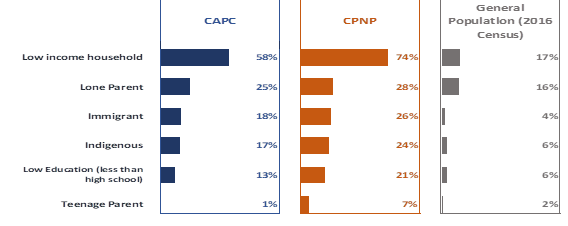

Findings from the surveys illustrate that PHAC is generally reaching its target populations, as the majority of participants identified with at least one of the socio-demographic characteristics measured by the survey to identify populations who may be at risk. In particular, more than half of CAPC and CPNP participants reported living at or below the low-income measure, while approximately one quarter identified as being a lone parent, as shown in Figure 5. Additionally, approximately one quarter of CPNP participants also identified as being an Indigenous person or having lived in Canada for less than ten years. While one of the key target populations of the CAPC and CPNP is teenage parents, only 1% of CAPC parents and caregivers and 7% of CPNP participants identified as a teenage parent. The proportion for CPNP is notably higher than the 2% of teenage parents and caregivers identified in the general population.

Overall, the proportion of CAPC and CPNP participants that identified with at least one of the socio-demographic characteristics measured significantly exceeded the proportion of the general Canadian population that identified with these characteristics, indicating that the CAPC and CPNP are reaching their target populations. Several external and some internal key informants also discussed the socio-demographic characteristics of CAPC and CPNP participants. In particular, they noted an increasing number of immigrant families seeking support from CAPC and CPNP projects in urban and rural communities across Canada. These assertions are supported by the survey findings, which indicate that 9.5% of CAPC parents and caregivers and 13.1% of CPNP participants in 2018 had lived in Canada for less than a year, compared to less than two percent in 2015.

Figure 3: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of CAPC and CPNP Participants, 2018, and the General Population, 2016 CensusEndnotev

Source: 2018 CAPC Participant Survey, 2018 CPNP Participant Survey, Statistics Canada 2016 Census

Figure 3 - Text Equivalent

Figure 3 presents socio-demographic characteristics of CAPC and CPNP participants (from 2018) and the general population (from the 2016 Census).

- Low income households represented 58% and 74% of CAPC and CPNP participants, respectively, while they represented 17% of the general population.

- Lone parents represented 25% and 28% of CAPC and CPNP participants, respectively, while they represented 16% of the general population.

- Immigrants represented 18% and 26% of CAPC and CPNP participants, respectively, while they represented 4% of the general population.

- Indigenous represented 17% and 24% of CAPC and CPNP participants, respectively, while they represented 6% of the general population.

- Low education (less than high school) represented 13% and 21% of CAPC and CPNP participants, respectively, while they represented 6% of the general population.

- Finally, teenage parents represented 1% and 7% of CAPC and CPNP participants, respectively, while they represented 2% of the general population.

An environmental scan was also completed in summer 2019 which provides an overview of socio-demographic trends with regards to CAPC and CPNP target populations in relation to project locations, in an effort to optimize reach and to identify where needs for the CAPC and CPNP continue to exist across Canada. In general, data from the environmental scan illustrated that CAPC and CPNP projects and satellite sites are primarily located (i.e., 81% of projects and satellite sites) in communities where there are socio-economic or school readiness vulnerabilitiesEndnotevi.

However, some projects may be providing services to individuals who do not identify with specific socio-demographic characteristics or may be located in communities without socio-economic or school readiness vulnerabilities.

While the majority of project participants in 2018 identified with at least one socio-demographic characteristic measured by the CAPC and CPNP survey, approximately 33% of CAPC and 19% of CPNP participants did not identify with any of the characteristics identified in the surveys. Consequently, some participants of CAPC or CPNP projects may identify with target populations not measured by the survey or may not be members of PHAC's target populationsEndnotevii. These proportions are similar to those reported in the findings from the 2015 participant surveys. The optimization of the reach of the CAPC and CPNP has been an ongoing issue for PHAC, and was noted as a recommendation in the previous evaluationEndnoteviii.

In addition, evidence suggests that approximately one in five CAPC and CPNP projects and satellite sites are located in communities where there are no socio-economic or school readiness vulnerabilities. However, the findings from the environmental scan do not reflect all risk factors that may negatively affect a healthy pregnancy and early childhood development and thus do not tell the whole story regarding the reach of the CAPC and CPNP. As such, further assessment may be required regarding the locations of CAPC and CPNP projects and satellite sites to determine whether there are other trends related to conditions of risk that require support from the CAPC or CPNP, or if there are pockets of vulnerability at the neighbourhood level, particularly in large urban communities.

PHAC is aware of the limitations of the environmental scan and will consider them when using its findings to inform the next renewal of CAPC and CPNP projects in 2023. This will be done with the goal of ensuring that all projects are reaching target populations and are located in communities with the most need. In particular, the findings will be considered along with other data sources to inform program decisions. Additionally, PHAC should address any potential gaps in program reach and work with funding recipients to ensure they are reaching Canadians who are most in need of the CAPC and CPNP. At the time of the evaluation, the findings from the environmental scan and their limitations were shared with CAPC and CPNP regional staff to inform and facilitate discussions around CAPC and CPNP renewals and reinvestments.

4.2 Program participation

CAPC and CPNP projects play a key role in helping participants connect with other programs and services, and offer a wide variety of programs and activities to address the needs of participants. The type, frequency, and duration of programming, as well as the extent to which participants had a positive experience can influence the extent to which they achieved positive results such as improved health and wellbeing.

CAPC and CPNP projects offer a wide variety of activities to address the needs of their participants. The activities provided usually include a combination of group sessions (e.g., classes), individual sessions (e.g., counseling, one-on-one support), and support services (e.g., referrals to health professionals). Almost all (95%) of the parents and caregivers that participated in a CAPC project were involved in at least one group session, whereas nearly two-thirds (62%) participated in individual sessions. Most participants in CPNP projects participated in group sessions (94%) and individual sessions (95%).

While group and individual sessions played a key role in CAPC and CPNP projects, many internal and external key informants emphasized referrals and connecting participants to other services as a significant strength of funded projects. It was noted that project staff played a key role in helping participants navigate a complex system of programs and services that can help participants address some of their challenges (e.g., housing, substance use). The ability for staff to assume this role was credited to the friendly, welcoming, and safe atmosphere provided by the projects, and the trusting relationships between staff and participants.

Evidence from the surveys found that participants who had a positive experience with a CAPC or CPNP project were more likely to report improvements in their skills and behaviours. Positive experiences were more likely to be noted by participants who had longer and more frequent exposure to funded projects, and by CAPC participants when they received individual support or counseling. Consequently, how CAPC and CPNP projects are delivered (e.g., frequency, type of programming) appears to be an important factor for achieving positive results.

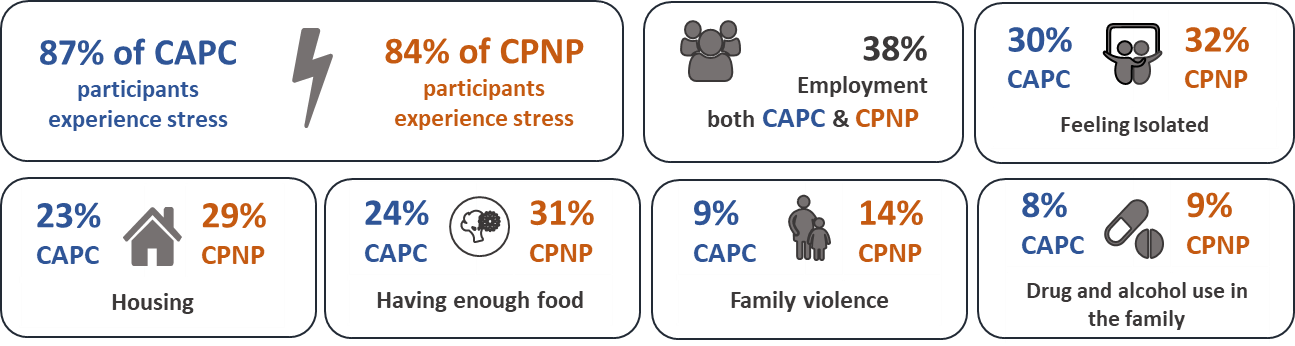

The type of challenges experienced by program participants was also shown to have an impact on the extent to which they experienced positive changes because of their involvement with a CAPC or CPNP project. When asked about challenges they experienced in the year prior to the survey, the majority of CAPC and CPNP participants indicated that stress was their greatest challenge (87% and 84% respectively), as illustrated in Figure 6. Additional challenges experienced by participants include employment, feeling isolated, having enough food, housing, family violence, as well as drug and alcohol use in the family. Internal and external key informants echoed these challenges and noted transportation as a significant challenge for CAPC and CPNP participants.

Figure 4: Challenges Experienced by CAPC and CPNP Participants, 2018

Source: 2018 CAPC Participant Survey and 2018 CPNP Participant Survey

Figure 4 - Text Equivalent

Figure 4 presents the challenges experienced by CAPC and CPNP participants, based on the 2018 CAPC Participant Survey and 2018 CPNP Participant Survey.

The majority of CAPC and CPNP participants indicated that stress was their greatest challenge (87% and 84% respectively). Additional challenges experienced by participants include employment (38% for both programs), feeling isolated (30% and 32% for CAPC and CPNP, respectively), having enough food (24% and 31% for CAPC and CPNP, respectively), housing (23% and 29% for CAPC and CPNP, respectively), family violence (9% and 14% for CAPC and CPNP, respectively), as well as drug and alcohol use in the family 8% and 9% for CAPC and CPNP, respectively).

4.3 Improving health and wellbeing

The CAPC and CPNP helped participants gain knowledge and skills, as well as improve health behaviours and overall health and wellbeing.

Findings from the 2018 CAPC and CPNP surveys demonstrate that the majority of participants (over 80%) reported that the programs had helped them gain knowledge and skills, adopt healthy behaviours, and improve their health and wellbeing. These findings align with the perceptions of many internal and external key informants who believed that most participants of CAPC and CPNP projects experienced positive changes.

Gaining Knowledge and Skills

The majority of parents and caregivers felt that participation in a CAPC project improved their parenting knowledge and skills (85%), including how children change as they learn and grow (89%), as well as how to keep their children healthy (85%) and safe (81%). When asked if they knew more about family violence because of the CAPC program, a little more than half of participants (59%) responded they did. Participants who identified as low income or lone parents reported greater gains in skills and knowledge, as did participants who received individual counselling from project staff. These results are comparable to those from the 2015 survey of CAPC participants.

When asked about the impacts of CAPC projects on their children's knowledge and skills, the majority of participants responded positively, stating that their children learned more about songs or rhymes (86%) and had more opportunities to play with books and toys (86%), as well as with other children (95%). Additionally, participants reported that their children experienced higher gains in skills and knowledge when they participated in group programs or classes.

CPNP participants reported highly positive results regarding the extent to which funded projects helped them increase their prenatal, postnatal, and parenting knowledge and skills. In particular, over 80% of participants noted that projects helped them improve their knowledge and skills in the areas of baby growth and development (94%), attachment and bonding (91%), safe sleep (91%), protection from injury (88%), breastfeeding (88%), post-partum depression (87%), as well as the effects of drinking alcohol and smoking while pregnant (83% and 81% respectively). Approximately three quarters of participants (74%) also noted that they knew more about family violence. The results of the 2018 CPNP participant survey are similar to those from 2015.

Health Behaviours

A significant proportion of CAPC participants reported adopting positive health behaviours because of their participation in a project. Such behaviours include, but are not limited to having more people to talk with when they need support (89%), more confidence in their parenting skills (86%), a better relationship with their children (86%), greater ability to handle challenges (80%), using new programs and services (79%), preparing healthier meals (78%) and a greater ability to cope with stress (74%). Improvements were particularly noted by participants who recently immigrated to Canada. These findings are relatively similar to those from the 2015 CAPC survey, with the exception of having a greater ability to cope with stress, which was higher in 2015 (78%).

The majority of CAPC participants also reported that their children engaged in positive health behaviours because of their involvement with a project. In particular, they noted that children were more comfortable in social settings (89%), spent more time playing games outside or doing other physical things (80%), were better able to express themselves (80%), and were more interested in being read stories or looking at books (77%). The extent to which CAPC participants reported positive changes among their children remained relatively stable between 2015 and 2018.

Most CPNP participants reported that they had adopted positive health behaviours because of their involvement with a project. Specifically, participants reported that they breastfed their baby (93%), had more people to talk with when they needed support (93%), had more confidence in their parenting skills (91%) and their ability to cope with childbirth (85%), were using new programs and services (84%), making healthier food choices (82%), and were better able to cope with stress (81%). About three quarters of participants (72%), reported that they limited their exposure to second-hand smoke and took prenatal or multivitamins more regularly.

While one quarter of CPNP participants (25%) reported smoking while pregnant, more than half (57%) of this group reduced their smoking, and almost a third quit smoking (31%). Of the participants that reduced or quit smoking, more than half (57%) credited this to the information and support received by the CPNP project. While the findings from the 2018 survey were similar to those from the 2015 survey, there were some differences. In 2018, more participants reported initiating breastfeeding (93% compared to 87% in 2015), while fewer participants felt that they were better able to cope with stress (78% in 2018 compared to 83% in 2015) or had more people to talk to when they needed support (86% in 2018 compared to 93% in 2015). Because of the limitations to comparing the data between 2015 and 2018, as well as the lack of qualitative data to contextualize these findings it is unknown why the proportions are lower in 2018. However, these data should be considered during the next survey of CPNP participants to examine possible trends and contextual factors that may help explain the data.

Health and Wellbeing

The majority of CAPC participants (86%) reported that their health and wellbeing had improved because of their participation in a project, with participants who identified as Indigenous reporting even greater improvements. Additionally, the majority of participants perceived that their mental health had improved (76%), as had the health and wellbeing of their children (90%). These findings are comparable with those from 2015, with the exception of improved mental health, which had decreased from 82% in 2015.

Almost all CPNP participants (94%) reported that their participation in a project had improved their health and wellbeing, with greater improvements reported by participants who identified as recent immigrants. Most CPNP participants noted that the project had a positive influence on their pregnancy (95%), and that their mental health had improved (83%). These findings are similar to those from 2015.

When asked questions about the health and wellbeing of their babies, CPNP participants who returned to the program following the birth of their baby reported that approximately 10% of babies were premature and 8% were born with low birth weight. Both of these proportions are slightly higher than the national average of 8% and 6.5% respectivelyFootnote15 Endnoteix. However, the proportion of babies born prematurely in 2018 was less than the proportion reported in 2015, which was 15%. The proportion of babies born with low birth weight were comparable in both surveys.

4.4 Responding to the Needs of Participants

Partnerships leveraged by projects at the community level, and the knowledge resources and capacity-building efforts supported by PHAC help projects address participant's needs.

Results from the 2018 CAPC and CPNP participant surveys suggest that the programs are addressing the needs of at-risk pregnant individuals, as well as young children and their families by helping them achieve positive changes. In particular, the majority of CAPC and CPNP participants (i.e., over 90%) reported that they had felt welcomed and accepted, that their personal and cultural beliefs were respected, that they had received valuable information for making decisions, and that staff had responded to their concerns and helped them to get the resources they needed. Additionally, several internal and external key informants, as well as data from the annual report tool noted that projects continue to play an important role in addressing the ongoing and fundamental needs of their participants to support prenatal health and early childhood development. Such needs include, but are not limited to, nutritional support, transportation, education and resources for parents and caregivers, as well as a safe space that is free from stigma where participants can connect with project staff, each other, and other programs that may help them address their needs and challenges.

The CAPC and CPNP were also able to address the needs of project participants by supporting the development of resources to support project staff and participants. According to some external key informants, these resources are integral to helping participants address their needs. According to program data, the majority of CAPC and CPNP projects (75% and 96% respectively) used at least one of the PHAC-funded resources to help address the needs of project participants. Examples of PHAC-funded resources include the 10 Valuable Tips for Successful Breastfeeding and the Sensible Guide to a Health Pregnancy. Additionally, PHAC funds five projects focused primarily on sharing information, developing training and building capacity. In 2017, these projects resulted in the development of 125 information resources, 178 education or training sessions (e.g., workshops, webinars), and five "on the job" training activities. Approximately 1,629 project staff engaged in the education and training sessions, while 1,199 project staff accessed the information resources and eight staff participated in the "on the job" training. Several external key informants noted that they had confidence in the knowledge products offered and funded by PHAC and that they were of high quality and useful for their CAPC or CPNP project.

Moreover, PHAC supported some information-sharing activities between CAPC and CPNP projects on a formal or semi-formal basis. For instance, PHAC funding is used to support the Alberta CAPC and CPNP Coalition and the Ontario Network of CAPC and CPNP projects, both of which offer opportunities for sharing information between projects in their respective province. Additionally, in Nova Scotia, there are annual meetings for CAPC and CPNP projects and in Saskatchewan, the PHAC regional office facilitates opportunities for projects across the province to come together at least once a year to share resources, learn from each other, and build connections between staff. While these exchanges provide great opportunities for projects to connect and build capacity, they are often limited to a number of projects and offer few opportunities for projects to share information outside of their province, territory, or region.

CAPC and CPNP projects are also successful in collaborating with a broad range of partners to help them meet the needs of target populations. According to program data, almost all projects (98%) engaged in a partnership with at least one organization in their community, while the majority of projects (88%) reported partnerships with more than four organizations. Health organizations such as community health centres or public health units were the most commonly reported CAPC and CPNP project partners (80% and 94% respectively). As noted by key informants, these partnerships allow CAPC and CPNP project staff to connect participants to services that could help address their risk conditions and challenges.

Several CAPC and CPNP participants identified with multiple socio-economic characteristics that may place them at risk, which may subsequently increase the complexity of the challenges they experience.

Survey findings suggest that 40% of CAPC participants and 56% of CPNP participants identified with two or more of the socio-economic characteristics measured by the participant surveys, which suggests that they are at an increased risk for experiencing challenges, such as stress, food insecurity, feeling isolated, housing, employment, family violence, and substance use. These proportions are higher than the 13% of children in the general population who are identified with two or more socio-economic status (SES) characteristicsFootnote16 that may place them at risk. The survey results align with the literatureFootnote17 and national data.Footnote18 The intersection of the various socio-demographic characteristics may compound the challenges experienced by CAPC and CPNP participants, placing them or their children at greater risk during pregnancy or early childhoodFootnote19. Program data, as well as many internal and external key informants corroborated the survey results, noting that the needs of participants as becoming increasingly complex over the last few years. Often urgent challenges/needs must be dealt with before projects can focus on achieving outcomes such as improving parenting skills, and promoting healthy practices. For instance, it can be difficult to focus on learning how to breastfeed, about proper nutrition, or how to help your child prepare for school when you are worried about housing, family violence, food security, etc. Additionally, because of the intersectionality between many of the risk conditions and challenges CAPC and CPNP participants experienced, several internal and some external key informants noted that project staff might not always have the skills and capacity to adequately address such complex needs, particularly when they are beyond the scope of traditional program objectives and activities.

Opportunities remain to enhance coordination and knowledge sharing with other PHAC programs, as well as between projects, stakeholders, and jurisdictions to provide projects with resources to help participants address their challenges.

To help build the capacity of project staff, several internal and external key informants identified opportunities to strengthen intradepartmental communication and coordination between the CAPC and CPNP, and other programs situated within PHAC's HPCDPB (e.g., Family and Gender-Based Violence Prevention, Mental Health Promotion). In particular, PHAC could provide funded projects with additional knowledge products so that they are better equipped to support participants in addressing their various needs and challenges. In addition to intradepartmental information sharing, several internal and external key informants perceived opportunities for PHAC to assume a greater leadership role in facilitating and coordinating the development of knowledge products and capacity-building resources across funded projects and with program stakeholders to ensure complementarity and expand reach. Key informants also recommended that PHAC provide and coordinate more opportunities to bring together program stakeholders and funded projects to inform the development of new resources that support innovative and promising practices to address challenges that negatively affect the health and well-being of target populations. Such coordination would help address the gap that remains following the end of the National Projects Fund, which provided funding to support short-term projects of national scope focused on knowledge development and exchange.

A similar need was highlighted in the previous evaluation of the CAPC and CPNP, which recommended that PHAC formalize and implement a strategic plan for knowledge development and exchange to ensure complementarity and the optimization of PHAC resources. In response, PHAC developed a three-year plan to coordinate knowledge development and sharing strategically. The plan focused on the period from 2017 to 2020, and included performance measures to assess progress as well as the utility of these activities. While PHAC has made advances in knowledge sharing (e.g., the development of a resource inventory for funded projects), opportunities exist to build upon this plan and consider ways to strengthen and enhance PHAC's roles and responsibilities regarding resource development and information sharing.

Resources must recognize and reflect the diversity among CAPC and CPNP participants.

Further to increasing the sharing of resources, some internal and external key informants emphasized that it is important these resources recognize the diversity of Canadian families including expanding the focus of the CAPC and CPNP projects beyond mothers. For instance, fathers are increasingly playing an important role in supporting partners during their pregnancy and the healthy development of their children. In 2017-2018, approximately 12% of CAPC parents and caregivers and 8% of CPNP participants were fathers. Additionally, some external key informants indicated observing more transgender individuals who are pregnant participating in CPNP projects, as well as more LGBTQ parents and grandparents attending CAPC and CPNP projects. It was further noted that resources should be culturally and linguistically appropriate.

In addition, some key informants noted that it would be helpful if resources were available in various languages, as approximately one quarter of projects (26%), provided programming in languages other than English and French. Several external key informants also proposed that PHAC offer its knowledge products in various digital formats (e.g., website, social media, videos), which is partially based on the positive response to and increased reach of the virtual programming and online social media presence of some CAPC and CPNP projects during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Opportunities to enhance knowledge sharing and information should be considered within the context of available resources, particularly given other key program responsibilities including administering over 500 contribution agreements, as well as providing policy guidance, information and advice.

COVID-19

The needs of CAPC and CPNP participants have been amplified throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and projects have been further challenged to address these needs.

Internal and external key informants indicated that the needs of CAPC and CPNP target populations were amplified throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. As many community services were closed or unable to offer in-person services, it became increasingly difficult for CAPC and CPNP projects to address the needs of at-risk pregnant individuals, as well as young children and their families. Many key informants noted that projects are doing their best to adapt by offering programs and information online (e.g., group sessions using Zoom or Facebook), one-on-one services when possible (e.g., phone call check-ins, socially distanced meetings in parks), as well as gift certificates, food baskets, and vouchers (e.g., for milk). These assertions were corroborated with data from the annual reporting tool.

Some external key informants noted that such project adaptations have resulted in unexpected positive outcomes including reaching more pregnant individuals and families with young children through their online programming. In particular, some projects have been able to reach individuals and families who may not have felt comfortable attending activities in person, who do not have access to childcare or transportation, who work during the day or who live in rural or remote areas. As a result, some projects will likely continue to offer online programming post-COVID-19, in addition to in-person activities. Projects have also been able to create new relationships with community organizations such as food banks, in order to provide food and other essentials to participants.

Despite these positive outcomes, the required changes to many CAPC and CPNP projects in response to the pandemic has also limited access to or the impacts of several projects. According to some external key informants, while projects have been able to increase their reach to certain groups of participants, online programming is unavailable for (potential) participants with unreliable or unaffordable internet. Additionally, it was noted that COVID-19 has limited the impacts and value of some projects as it has taken away group gatherings and limited the opportunities for participants to connect with one another. This latter challenge was specifically noted for projects primarily serving Indigenous participants.

4.5 Measuring Program Benefits

CAPC and CPNP activities, outputs, and short-term benefits are measured through a broad set of data collection instruments.

PHAC has a broad set of instruments to collect data regarding program activities and the impacts of funded CAPC and CPNP projects. In addition to the participant surveys, PHAC employs the Children's Programs Performance Measurement Tool (CPPMT), a survey held every two years that asks funding recipients to report on program activities, resources, as well as knowledge development and exchange. Funded projects are also required to use a reporting tool every year to collect data regarding their progress towards achieving objectives, training activities and requirements, as well as qualitative information regarding project benefits, challenges, and opportunities for improvement. Consequently, PHAC has accumulated comprehensive data to understand the activities, outputs, and short-term benefits of CAPC and CPNP projects, including participant experiences. Internal program documents illustrate that PHAC has used this data to inform program decisions. For instance, CPPMT data was used to demonstrate program results and challenges to PHAC senior management and to inform decision-making.

While there are challenges determining program outcomes and the attributable changes in participant outcomes, PHAC attempts to mitigate these challenges through the participant surveys and proxy measures.

While some internal and external key information felt certain the programs contributed to the positive changes they observed in participants, they noted that it is also difficult to accurately demonstrate that the positive changes could be attributed to the CAPC and CPNP. This is partly due to the different objectives and outcomes of each program, as well as the diversity of interventions across funded projects, particularly CAPC projects, as they must be flexible enough to involve a variety of activities targeting children of different ages and their families to address a wide range of local issues and differing needs of communities. The possibility of attributing positive changes to the CAPC and CPNP is further complicated by the fact that participants may receive support from other programs and services at the same time.

In addition to quantitative data collected through the participant surveys, the programs collect qualitative data that captures some of these complexities through participant stories and the annual reporting tool. The annual reporting tool is reviewed by the respective regional office primarily to ensure projects are progressing towards their planned objectives. There may be opportunities to further leverage the data from the annual reporting tool through systematic analyses at a regional and national level to gain greater insights regarding program impacts in each region and across Canada.

Several internal and external key informants perceived opportunities to improve the collection and demonstration of outcome level data including streamlining some of the instruments to reduce the reporting burden on funded projects. Additionally, it was suggested that PHAC could examine opportunities to conduct longitudinal studies that follow participants over time, and connect CAPC and CPNP projects with research teams that are able to engage in long-term data collection and analysis to demonstrate the long-term impacts of the programs. Currently program staff employ proxy measures (i.e., linking short-term outcomes with long-term outcomes based on the literature) in an effort to understand some of the possible long-term impacts of the CAPC and CPNP. Such opportunities will need to be examined within the context of available resources within PHAC and funded projects.

5.0 Efficiency of Program Delivery

5.1 Roles and Responsibilities

Efforts have been made to provide further clarification on roles and responsibilities across the three branches involved in the administration and management of the CAPC and CPNP with the development of a new Program Charter implemented fall 2020.

The recent Audit of the Management of Grants and Contributions at the Public Health Agency of Canada asserted that that the "Agency's existing tools for defining roles and responsibilities for managing grants and contributions under a centralized model had resulted in confusion and misalignment between accountabilities and responsibilities"Footnote20. Several internal key informants echoed these concerns and perceived having three branches involved with the CAPC and CPNP as limiting the efficiency of program delivery due to a lack of clarity regarding roles and responsibilities. At times this lack of clarity resulted in confusion and inconsistencies across the regions, as well as in CAPC and CPNP projects. While PHAC attempted to facilitate coordination and collaboration between the three branches through CAPC and CPNP governance structures, several internal key informants perceived ongoing disconnects between the branches. Moreover, some internal key informants noted that there is a perception of added confusion around roles and responsibilities and a lack of information sharing across branches because the CGC and Regional Operations do not report to the Vice-President of the HPCDPB, who is ultimately accountable for the CAPC and CPNP. To mitigate these challenges, the audit recommended collaboration between the CGC, Regional Operations, and the HPCDP to clarify and define responsibility and accountability structures for all parties involved in the management and administration of grants and contributions.

In response to the audit's recommendation and in an effort to mitigate additional challenges, the HPCDPB developed a DCY Program Charter in collaboration with the CGC and Regional Operations that outlines the roles and responsibilities of each branch as they relate to the delivery of the CAPC and CPNP. An integrated work plan was also developed to support the implementation of the Program Charter across the three branches. The Program Charter was finalized and approved in fall 2020; therefore, it is too early to assess its impacts on the efficiency of program activities. In addition to the Program Charter, some internal key informants noted that there has been recognition within PHAC that the various branches cannot work in silos, along with a concerted effort by the branches to increase communication and coordination in support of the delivery of CAPC and CPNP. These key informants are hopeful that the relationships between the three branches will continue to improve.

5.2 Program Resources

The G&Cs budget for the CAPC and CPNP remained stable between 2015-2016 and 2019-2020. However, in 2015-16 the DCY made the decision to transfer $700,000 in G&C funding from CPNP to CAPC on an ongoing basis to respond to increasing levels of program demand and need.

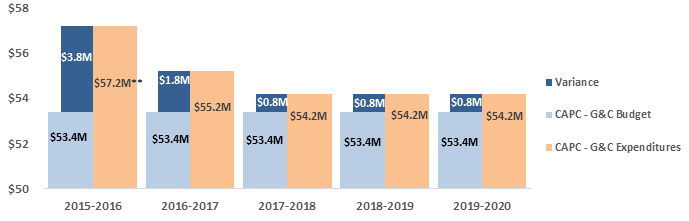

Between 2015-2016 and 2019-2020, PHAC spent approximately $82.5 million per year on activities related to the CAPC and CPNP including G&Cs, salaries and O&M. As presented in Figure 2, the majority of program expenditures were associated with the contributions provided to CAPC projects across Canada, with an annual average of approximately $54,987,718. CAPC expenditures for grants and contributions exceeded the program's budget for the evaluation period by a range of $3.8 million to $0.8 million, and an annual average of $1,587,718. However, the bulk of the overspending occurred in 2015-16 and 2016-17. In 2015-16 the overspending occurred as the result of a one-time spending increase for grants and contributions due to a surplus of funds within the HPCDPB. The increase in 2016-17 was due to a realignment of funds from CPNP. Additionally, throughout the period under evaluation PHAC spent more on G&Cs for the CAPC than what was budgeted because of a longstanding annual transfer of approximately $700,000.00 from the CPNP to the CAPC in the Atlantic Region. This transfer was implemented by the DCY in an effort to continue responding to the needs of target populations in the region. Consequently, the actual variance between the budget and expenditures for the CAPC is smaller than what is reported at an organizational level.

Figure 5: CAPC Grants and Contributions (G&C), Budget vs. Expenditures ($M)

Source: PHAC Office of the Chief Financial Officer

*Variance = actual-planned spending

** There was a one-time increase in spending in 2015-16 due to a surplus of grants and contributions funds within the HPCDPB, some of which were allocated to the CAPC and CPNP.

Figure 5 - Text Equivalent

Figure 5 presents financial information related to budgeted and actual expenditures for CAPC grants and contributions, as well as the variance.

- In 2015-16, $57.2 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $53.4 million, for a variance of -$3.8 million.

- In 2016-17, $55.2 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $53.4 million, for a variance of -$1.8 million.

- In 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20, $54.2 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $53.4 million, for a variance of -$0.8 million.

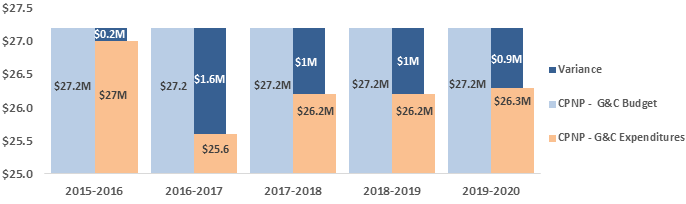

The average annual spending for CPNP projects was $26,254,390, as shown in Figure 3. G&Cs expenditures for the CPNP remained under budget for the period covered by this evaluation. This is partially attributed to the transfer of approximately $700,000 to the CAPC in order to offset the additional grants and contributions expenditures for that program. Additionally, program expenditures decreased in 2016-17 because a large CPNP project closed. The funds were transferred to 13 new CPNP projects the following year.

Figure 6: CPNP Grants and Contributions (G&C), Budget vs. Expenditures ($M)

Source: PHAC Office of the Chief Financial Officer

*Variance = actual-planned spending

Figure 6 - Text Equivalent

Figure 6 presents financial information related to budgeted and actual expenditures for CPNP grants and contributions, as well as the variance.

- In 2015-16, $27 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $27.2 million, for a variance of $0.2 million.

- In 2016-17, $25.6 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $27.2 million, for a variance of $1.6 million.

- In 2017-18 and 2018-19, $26.2 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $27.2 million, for a variance of $1 million.

- In 2019-20, $26.3 million was spent while the budgeted amount was $27.2 million, for a variance of $0.9 million.

On average, the CAPC and CPNP spent approximately 88% of its annual budget for salaries and O&M expenditures. The variance between the program budget and expenditures is primarily attributed to difficulties in staffing positions to support knowledge development and exchange, which is the focus of the O&M budget. See Appendix E for a detailed summary of the salary and O&M budget and expenditures for the CAPC and CPNP.

The CAPC and CPNP model provides a flexible platform for program delivery in order to meet the needs of target populations across Canada. Additionally, projects have been successful at leveraging funds and in-kind resources from other sources.

Internal program documents indicate that a key benefit of the CAPC and CPNP delivery model is the flexible platform it provides for addressing health promotion priorities, as project activities can be tailored to meet the needs of target populations. In addition, the current model offers opportunities to leverage partnerships with provincial and territorial governments and other sources for funding and in-kind resources.