Horizontal Evaluation of the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada 2013-14 to 2017-18

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 626 KB, 55 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: 2019-06-28

Prepared by the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

March 2019

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Evaluation Purpose

- 2.0 Program Description

- 3.0 Evaluation Description

- 4.0 Findings

- 5.0 Conclusions

- 6.0 Recommendations

- Appendix 1 - Roles of Responsibility Centres

- Appendix 2 - Logic Model

- Appendix 3 - Evaluation description

- Appendix 4 - Global Targets for STBBI

- Appendix 5 - Variance between Budget Appropriations and Expenditures

List of Tables

- Table 1: Planned Spending, FI to Address HIV/AIDS, 2013-14 to 2017-18 ($)

- Table 2: Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- Table 3: Variance Between Overall FI Planned Spending vs Expenditure 2013-14 and 2017-18 ($)

List of Acronyms

- CATIE

- Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CAF

- HIV and Hepatitis C Community Action Fund

- CBR

- Community-Based Research

- CSC

- Correctional Service Canada

- CTN

- CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network

- EBP

- Employee Benefit Plans

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- FI

- Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS

- HC

- Health Canada

- HIV/AIDS

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- G&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- III

- Institute of Infection and Immunity

- MAC-FI

- Ministerial Advisory Council on the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS

- MSM

- Men who have sex with men

- NACHA

- National Aboriginal Council on HIV/AIDS

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- O&M

- Operations and Maintenance

- PMS

- Performance measurement strategy

- PrEP

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- PSPC

- Public Service and Procurement Canada

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- RCC

- Responsibility Centre Committee

- STBBI

- Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

- STI

- Sexually transmitted infections

- UNAIDS

- United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Executive Summary

This evaluation covered the activities of the Federal Initiative (FI) to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada for the period of 2013-14 to 2017-18. FI represents an annual investment ranging from $70 to $78 million. The evaluation was undertaken in fulfillment of the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016).

Program Description

The FI is a horizontal initiative involving four Government of Canada organizations: the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Correctional Services Canada (CSC). The FI is a key component of the Government of Canada's comprehensive approach to HIV/AIDS. Through these four federal partners, the FI provides funding for prevention and support programs targeting priority populations, as well as research, surveillance, public awareness, and evaluation.

The goals of the FI are to:

- prevent the acquisition and transmission of new infections;

- slow the progression of the disease and improve quality of life;

- reduce the social and economic impact of HIV/AIDS; and

- contribute to the global effort to reduce the spread of HIV and mitigate the impact of the disease.

FI activities aim to reach two distinct groups: priority populations who are at risk for, or living with, HIV, and target audiences of individuals and organizations that are involved in helping priority populations. Target audiences include public health practitioners, frontline health care professionals and providers, educators, researchers, academics and trainees, and laboratory networks. Other stakeholders in the program include other government organizations at all levels, community-based organizations, and global partners.

Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The scope of this evaluation covers the period from April 2013 to March 2018. Issues covered by this evaluation include an assessment of relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency. An outcome-based evaluation approach was used to assess the progress made toward the achievement of expected outcomes, as well as to determine if there were any unintended consequences and what lessons were learned.

Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, including:

- literature review;

- document review, including performance measurement data review;

- key informant interviews;

- case studies; and

- financial data review.

Conclusions - Relevance

There is a continued need for federal investments and activities, as HIV/AIDS remains a persistent public health issue that disproportionately affects priority populations. Prevention, diagnosis, care, and treatment are essential to manage and control HIV and other related sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI). The estimated HIV incidence rate in Canada has shown a slight increase from 2014; additional years of data are needed to determine whether this represents a true increase because of the wide plausible ranges around these estimates. Rates of related STBBI are also on the rise.

Success in HIV treatment has resulted in a worldwide momentum to eliminate new infections. To this end, Canada has endorsed the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization's (WHO) global health sector strategies to address HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections (STI), with the goal of eliminating STBBI as a health concern by 2030.

FI activities align well with the legislated mandate and authorities of each of its federal partners. Partners and external stakeholders understand FI roles and responsibilities well. External stakeholders see the Government of Canada as having an important role in national and international coordination, as well as in knowledge translation for HIV/STBBI prevention, care, treatment, support, and research.

Conclusions - Performance

FI activities conducted by all four partners have contributed to increased awareness and better practices to prevent the acquisition and transmission of HIV for both priority populations and target audiences. For example, priority populations were provided with direct interventions (e.g., in correctional institutions, on reserves) or community-based activities that increased their knowledge and awareness. Target audiences were also provided with webinars, guidelines, and other knowledge products that increased their knowledge and awareness.

Findings indicate that, while awareness and use of knowledge products developed by PHAC on HIV and other STBBI is high among practitioners working in the sexual health field, there are still gaps among primary care providers. Thus, there are opportunities to expand the reach of FI-developed knowledge products to additional networks, so that primary care providers (i.e., family and general practitioners) would be better able to increase their awareness and use of PHAC HIV and STBBI knowledge products. FI partners should also consider stakeholder information needs in areas of shared jurisdiction between federal and provincial responsibilities (e.g., the use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis [PrEP], testing availability) to address gaps in knowledge products.

Through the provision of services such as laboratory sciences and access to harm reduction materials in correctional institutions, FI activities have strengthened the capacity of target audiences and priority populations to prevent and control HIV. Community-based activities funded by the FI have also supported behaviour change among priority populations through adoption of healthier sexual and drug use behaviours, and by providing linkages to care and treatment.

However, data collected to date on PHAC-funded community-based activities indicates that some of the most at-risk populations for HIV and other STBBI (e.g., gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men) were not sufficiently reached over the last five years by the activities offered by community-based projects. Since 2017, through the implementation of the HIV and Hepatitis C Community Action Fund (CAF), PHAC has taken a step to address this challenge and has funded projects that demonstrate best potential for impact. As such, CAF has refocused funding priorities, priority populations, and eligible activities.Footnote 1

In addition, PHAC has also implemented a new Harm Reduction Fund aimed at reducing HIV and hepatitis C among people who share injection and inhalation drug-use equipment, thus supporting community-based intervention with the most at-risk populations.Footnote 2

Conclusions - Economy and Efficiency

Through the Responsibility Centre Committee (RCC), the FI has put in place an oversight and governance body that fosters information exchange and a high level of collaboration between partners. The FI has also put mechanisms in place that allow partners to collaborate with stakeholders. They have also established useful ways to ensure consultation with stakeholders on various files.

With high levels of collaboration between federal partners and the involvement of external stakeholders, the FI was able to put together a federal response that is seen by internal and external stakeholders as generally coherent. However, some stakeholders, including provincial representatives, identified gaps in the overall response. As such, they have called for additional coordinated action to address stigma and discrimination as it relates to HIV and other STBBI, and to increase access to testing technology.

The FI authorities have allowed partners to link HIV/AIDS programs with other related infection programs to maximize the effectiveness of activities and ensure an integrated response. Within this context, partners have worked over the last five years to increase integration of activities to address HIV with other related STBBI, and improve the response. While the majority of stakeholders have been supportive of this integration, and have welcomed the new Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action, they require more information on what actions FI partners will take to address disease-specific targets as part of this approach.

While the FI has successfully implemented a comprehensive internal performance measurement strategy (PMS) and FI partners have collected performance data over the years, the use of this data for decision making is limited, as a summary of the data has not been compiled in recent years. Identifying critical information would help guide a streamlining of information collected through the PMS and associated tools. This would help summarize performance data and maximize its use.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1 (for all FI partners)

Determine how federal investments will contribute to the goals outlined in the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action, including reducing STBBI-related stigma and discrimination, and aligning investments with those populations with the highest burden of STBBI. Communicate this to external stakeholders and Canadians.

The Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action sets out an overarching and comprehensive approach to support and contribute to achieving global STBBI targets. While integration of the federal HIV response with its response to STBBI is well supported, internal and external stakeholders are unsure which actions will be taken by federal partners within this framework. As such, stakeholders need more clarity on what actions the FI partners will take to achieve the disease-specific global targets. Additional information on addressing STBBI-related stigma and discrimination, as well as information on aligning investment to populations with the highest burden of STBBI is needed.

Recommendation 2 (specific to PHAC)

Explore partnerships and mechanisms to facilitate the dissemination and uptake of STBBI-related knowledge products.

Awareness and uptake of current HIV and related STBBI knowledge products by sexual health practitioners is high. Still, to increase the chances of accessing the undiagnosed, FI partners must work with other key stakeholders to achieve higher levels of awareness and uptake of HIV and related STBBI knowledge by all intended target audiences, including primary care practitioners. FI partners should also give further consideration to how they could better support uptake of knowledge products in areas of shared jurisdiction between federal and provincial responsibilities (e.g., guidance for the use of PrEP, access to testing technology), as there are gaps in these areas.

Recommendation 3 (for all FI partners)

Enhance the use of performance information by simplifying indicators within the current performance measurement strategy to allow for annual reporting of results.

The FI has successfully implemented a comprehensive internal performance measurement strategy and FI partners have been collecting performance data for years. While PHAC has managed to fulfill its reporting obligation on the FI through the Departmental Results Report, FI partners would like to see an internal annual report to monitor progress and facilitate decision making. Simplifying the indicators in the PMS and ensuring that each FI partner is able to collect required data would make preparing an annual report more feasible.

Management Response and Action Plan

Horizontal Evaluation of the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada

With the introduction of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action in June 2018, the Government of Canada has communicated its intention of integrating its HIV response with its response to other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI). Within this context, recommendations and action plans presented below apply not only to the Evaluation of the Federal Initiative to address HIV/AIDS in Canada, but also to the Evaluation of Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections Activities at the Public Health Agency of Canada, both of which were conducted at the same time.

| Recommendations | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables |

Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

| Recommendation 1: Determine how federal investments will contribute to the goals outlined in the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action, including reducing STBBI-related stigma and discrimination, and aligning investments with those populations with the highest burden of STBBI. Communicate this to external stakeholders and Canadians. | Management agrees with the recommendation | Develop and implement the Government of Canada's Action Plan on STBBI that will outline the actions that will be undertaken by FI partners and other Government of Canada departments to contribute to the goals of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework. | a) Federal Action Plan on STBBI | Release of Government of Canada's Action Plan on STBBI by June 2019 | Lead: Vice President of IDPC DG, CCDIC, PHAC With support and contribution of Federal Partners |

Utilize existing full-time equivalents (FTEs) and operations and maintenance (O&M) |

| b) Federal progress report | June 2021 | |||||

| Recommendation 2: Explore partnerships and mechanisms to facilitate the dissemination and uptake of STBBI-related knowledge products. | Management agrees with the recommendation | Develop a strategy that outlines options and recommendations to enhance and facilitate the uptake of STBBI-related knowledge products, including targeted activities for different stakeholder groups, such as primary care providers, and identify key stakeholders and partners who could support the development and mobilization of key products. | Knowledge mobilization strategy | December 2019 | Vice President of IDPC Director General of Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control | Utilize existing FTEs and O&M |

| Recommendation 3: Enhance the use of performance information by simplifying indicators within the current performance measurement strategy to allow for annual reporting of results. | Management agrees with the recommendation | Review the existing STBBI performance measurement strategy to align with Government of Canada's Action Plan on STBBI and the agreed upon FPT STBBI Indicators Framework. | a) STBBI Indicators Framework | March 2020 | Vice President of IDPC DG, CCDIC Other federal partners | Utilize existing FTEs and O&M |

| b) Revised STBBI Performance Measurement Strategy and Indicators | March 2021 |

1. Evaluation Purpose

This evaluation reviewed activities undertaken by the four departments and agencies (partners) funded under the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada (FI): the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Correctional Services Canada (CSC). The evaluation examined the relevance, performance, and efficiency of FI activities for the period from April 2013 to March 2018.

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016).

The evaluation also discusses the release of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action in June 2018, even if it falls outside of the period of this evaluation, as this Framework sets the future of the integrated STBBI program, which will include FI partners' activities on HIV.

2. Program Description

2.1 Program Context

The Government of Canada has proactively addressed the domestic AIDS epidemic for more than 30 years. A coordinated effort began in 1990 with the National AIDS Strategy, which was followed by the Canadian Strategy on HIV/AIDS in 1998.

The Government of Canada's continued commitment to address HIV was reaffirmed in 2004 with an announcement by the Minister of Health of a strengthened and expanded federal response, through the creation of the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada (FI), officially launched in January 2005.

Through the FI, PHAC, CIHR, ISC, and CSC collaborate with other Government of Canada departments, provincial and territorial governments, non-governmental organizations, researchers, public health and health care professionals, and priority populations disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS in five areas of federal action:

- program and policy interventions;

- knowledge development;

- communications and social marketing;

- coordination, planning, evaluation, and reporting; and

- global engagement.

Since HIV shares common risk factors and transmission routes as other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI), FI partners have progressively moved towards an integrated approach to address HIV and other STBBI.

2.2 Program Profile

The FI is a key component of the Government of Canada's comprehensive approach to HIV/AIDS. The FI provides funding for prevention and support programs targeting priority populations, as well as research, surveillance, public awareness, and evaluation.

The goals of the FI are to:

- prevent the acquisition and transmission of new infections;

- slow the progression of the disease and improve quality of life;

- reduce the social and economic impact of HIV/AIDS; and

- contribute to the global effort to reduce the spread of HIV and mitigate the impact of the disease.

FI activities aim to reach two distinct groups: priority populations who are at risk for, or living with, HIV, and target audiences of individuals and organizations that are involved in helping priority populations. Target audiences include public health practitioners, frontline health care professionals and providers, educators, researchers, academics and trainees, and laboratory networks.

2.3 Partners and Governance

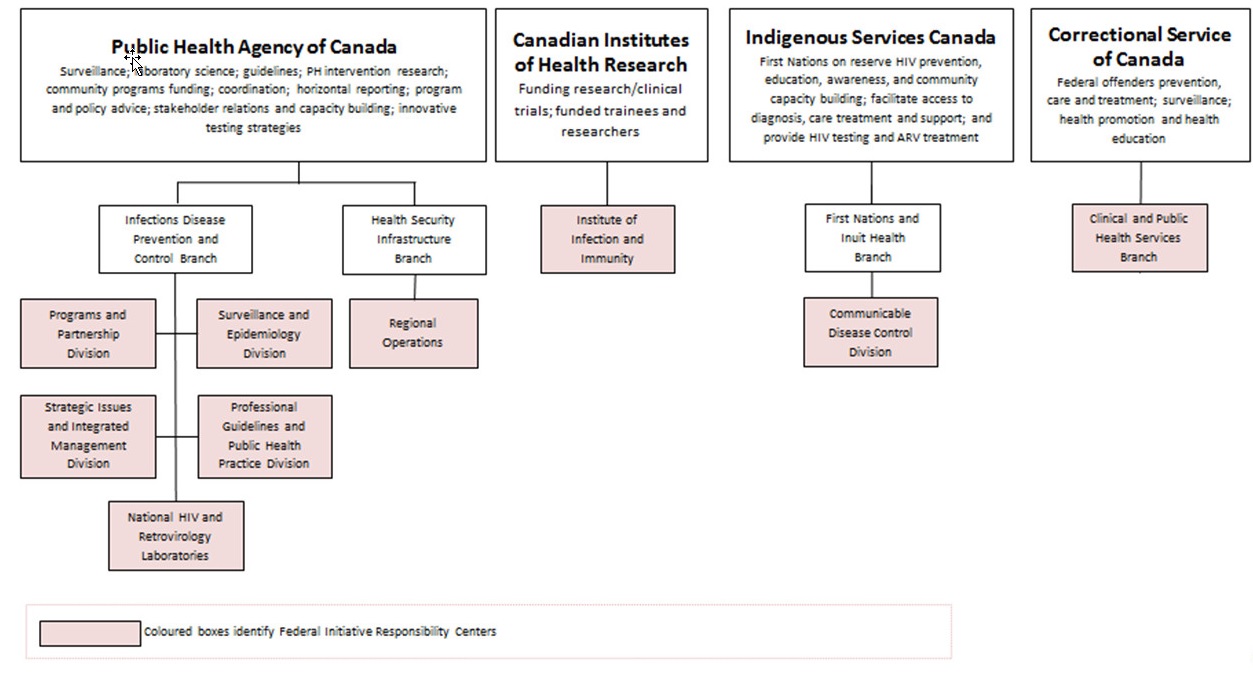

Roles and responsibilities for the FI are divided among the four FI partners, each with specific mandates and responsibilities.

- PHAC is the federal lead for issues related to STBBI, including HIV in Canada. It is responsible for laboratory science, surveillance, program development, knowledge exchange, public awareness, guidance for health professionals, and global collaboration and coordination;

- CIHR is the Government of Canada's agency for health research. It supports the creation of new scientific knowledge and enables its translation into improved health, more effective health services and products, and a strengthened Canadian health care system;

- ISC, through its First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), supports STBBI prevention, education and awareness, community capacity building, as well as facilitating access to quality HIV/AIDS diagnostics, care, treatment, and support to on-reserve First Nations and Inuit communities south of the 60th parallel. Prior to the creation of ISC in 2017, these roles and responsibilities were assumed by Health Canada (HC); and

- CSC, an agency of the Public Safety Portfolio, provides health services to offenders in federal institutions, including services related to the prevention, diagnosis, care, and treatment of HIV and other STBBI.

The four partners divide FI work by responsibility centres, each having distinct roles, responsibilities, and contributions towards FI goals. The Responsibility Centre Committee (RCC) is the governance body for the FI, chaired by a PHAC representative, and composed of the Director or Director General of the nine responsibility centres listed by the four FI partners. The RCC aims to promote policy and program coherence among the participating departments and agencies, and to ensure that evaluation and reporting requirements are met.

Figure 1 illustrates the FI's nine responsibility centres. A detailed description of responsibilities associated with each responsibility centre is available in Appendix 1.

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

This figure describes the structure and activities of the four federal responsibility centres which implement the Federal Initiative to address HIV/AIDS. The four federal organizations which deliver the federal initiative are the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), and Correctional Service Canada (CSC).

PHAC is responsible for surveillance, laboratory science, guidelines, public health intervention research, funding community programming, coordination of the federal initiative, horizontal reporting, program and policy advice, stakeholder relations and capacity building, and innovative testing strategies.

Within PHAC two branches house the six responsibility centres:

- The Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, which includes the Program and Partnerships Division; Surveillance and Epidemiology Division; Strategic Issues and Integrated Management Division; Professional Guidelines and Public Health Practice Division; and the National HIV and Retrovirology Laboratories. And;

- The Health Security Infrastructure Branch, which includes Regional Operations

The Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) are responsible for funding research and clinical trials, trainees, and researchers. Within CIHR there is one responsibility centre: the Institute of Infection and Immunity.

Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) is responsible for HIV prevention, education, awareness and community capacity building for First Nations living on-reserve. ISC also facilitates access to diagnosis, care, treatment, and support; and provides HIV testing and antiretroviral treatment for First Nations on reserve. The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch at ISC houses one responsibility centre: the Communicable Disease Control Division.

Correctional Services Canada is responsible for prevention, care, treatment, surveillance, health promotion, and health education related to HIV/AIDS within federal correctional institutions. Within CSC there is one responsibility centre: the Clinical and Public Health Services Branch.

2.4 Previous Evaluations

The FI was previously evaluated in 2014, covering the period from 2008-09 to 2012-13. The evaluation revealed a need for the following:

- Improving joint work planning and priority setting;

- Enhancing knowledge exchange and application by supporting knowledge translation activities and implementing promising practices.

- Strengthening activities that address barriers to prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and support.

- Enhancing internal information collection and use, including monitoring and adjusting for continuous improvement, and updating the logic model and performance measurement strategy to reflect the evolution of the FI.

2.5 Program Narrative

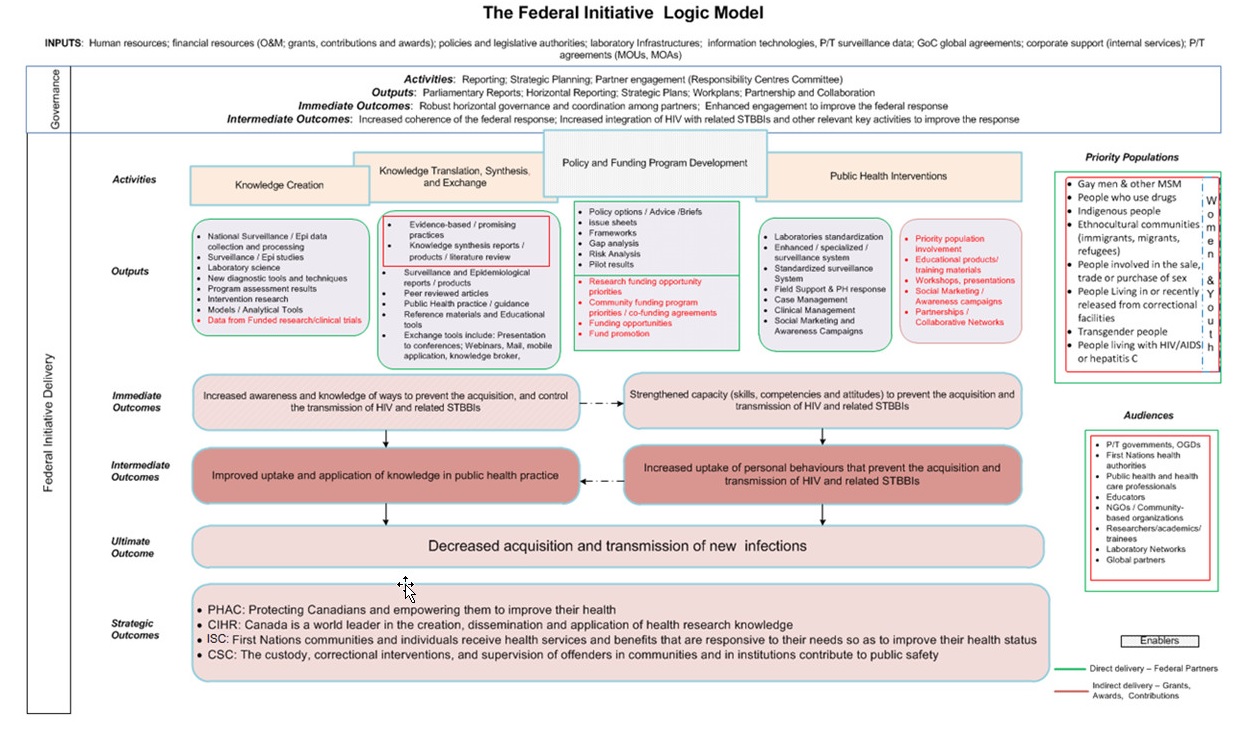

The FI aims to achieve two types of outcomes: delivery outcomes and governance outcomes.

FI delivery outcomes are the result of its four primary activities, which are as follows:

- Knowledge Creation;

- Knowledge Translation, Synthesis and Exchange;

- Policy and Funding Program Development; and

- Public Health Interventions.

Some of these activities are performed directly by the Government of Canada, while others are performed by organizations who receive grants and contributions funding. Through these activities, the FI seeks to achieve the following delivery outcomes:

- increased awareness and knowledge of ways to prevent the acquisition and transmission of HIV;

- strengthened capacity (skills, competencies, and attitudes) for priority populations and target audiences;

- improved uptake and application of knowledge in public health practices; and

- increased uptake of personal behaviours that prevent the transmission of HIV.

FI governance outcomes result from activities that encourage joint planning and engagement between the four FI partners, as well as collaboration with external stakeholders. Through these activities, the FI seeks to achieve the following governance outcomes:

- robust horizontal governance and coordination among partners;

- enhanced engagement to improve federal response;

- increased integration of HIV with associated STBBI, and other relevant key activities to improve the response; and

- increased coherence of the federal response.

Ultimately, all FI activities and outcomes aim to achieve decreased acquisition and transmission of new HIV infections.

The connection between the activity areas and all expected outcomes is depicted in the program logic model (see Appendix 2). The evaluation assessed the degree to which the defined delivery and governance outcomes have been achieved.

2.6 Program Resources

Table 1 presents the total FI planned spending by the four FI partners from 2013-14 to 2017-18. Overall, FI planned spending was $358 million over five years.

| Year | Grants and Contributions (G&Cs) | Operations and Maintenance (O&M)/Capital Footnote a | Salary Footnote b | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013-14 | 46,288,601 | 10,847,017 | 15,129,562 | 72,265,180 |

| 2014-15 | 45,103,056 | 10,416,493 | 14,660,086 | 70,179,635 |

| 2015-16 | 46,161,310 | 8,736,597 | 15,607,779 | 70,505,687 |

| 2016-17 | 46,411,662 | 10,467,038 | 15,721,300 | 72,600,000 |

| 2017-18 | 46,835,758 | 9,832,797 | 15,931,445 | 72,600,000 |

| Total | 230,800,387 | 50,299,942 | 77,050,172 | 358,150,501 |

Source: Financial data provided by the Chief Financial Officer Branch (CFOB).

|

||||

Source: Financial data provided by the Chief Financial Officer Branch (CFOB).

Notes: a O&M/Capital includes Public Service and Procurement Canada (PSPC) accommodation costs.

b Salary includes contributions made to employee benefit plans (EBP)

3.0 Evaluation Description

3.1 Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

The scope of this evaluation covers the period from April 2013 to March 2018. Issues covered by this evaluation are aligned with the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016) and include an assessment of relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency. The evaluation process was guided by consideration of the core issues, as well as specific questions developed in consultation with the program.

An outcome-based evaluation approach was used to conduct the evaluation and assess the progress made toward the achievement of expected outcomes, whether there were any unintended consequences, and what lessons were learned.

Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, including the following:

- literature review;

- document review, including performance measurement data review;

- key informant interviews;

- case studies; and

- financial data review.

More specific details on data collection and analysis methods are included in Appendix 3. Data was analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different methods listed above. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation was intended to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may have implications for the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. Table 2 outlines the limitations encountered during the implementation of the selected methods for this evaluation. Also noted are the mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings could be used with confidence to guide program planning and decision making.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

Limited primary data collection |

|

|

Key informant interviews are retrospective in nature. |

|

|

Limitations in performance data:

|

|

|

Some key performance indicators were updated or changed during the period under evaluation. |

|

|

4.0 Findings

4.1 Relevance

There is a continued need for federal investments, as HIV/AIDS remains a persistent public health issue that disproportionately affects priority populations. The evaluation found that FI activities are well aligned with the Government of Canada's commitment to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. Additionally, the work of the FI is well aligned with the legislated mandate of each of the federal partners.

Continued Need

At the end of 2016, it was estimated that there were 36.7 million people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide. Footnote 3 While the burden of HIV/AIDS in Canada is small when compared to developing countries, Canadian national HIV estimates at the end of 2016 indicated that HIV remains a persistent public health issue that disproportionately affects certain groups of people, including priority populations.

In 2016, the number of new HIV infections in Canada increased relative to 2014 levels. The estimated incidence rate in Canada was 6.0 per 100,000 population, compared to 5.5 per 100,000 population in 2014. Footnote 4 This incidence rate is the highest of the past five years. However, due to the wide plausible ranges around the estimates for the most recent periods, it is unclear if this represents a true increase in the underlying number of new infections. Part of the increase in cases could be explained by increased testing. This is due to the implementation of new provincial testing initiatives aimed at reaching undiagnosed populations. Footnote 5 As such, increased testing for HIV has led to an increase in new HIV diagnoses, which in turn may have influenced the modelled estimate of HIV incidence. Footnote 6 Additional years of data are needed to determine whether this represents a true increase in HIV incidence.Footnote 7

There was also a five percent increase in the prevalence of HIV from 2014, with 63,110 Canadians living with HIV at the end of 2016. Footnote 8 The increase in prevalence may be attributed to longer life expectancies due to effective treatment options, as well as an increased number of reported cases.

Certain populations are more likely to be infected with HIV than others. Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) represented more than half (52.5%) of all new HIV infections in 2016, despite representing approximately two to three percent of the Canadian adult male population. Indigenous people and people from countries where HIV is endemic also continue to be overrepresented in the HIV epidemic in Canada.Footnote 9

With rates increasing slightly over time, and certain populations more likely to be infected than others, it is clear that there is still a need for the Government of Canada to continue working on addressing HIV in Canada.

The evaluation also found that there was a continued need for HIV/AIDS-related research. While significant progress has been made in terms of treatment over the last 20 years, finding a cure remains a priority for people with lived experience. Furthermore, as HIV-positive people are living longer with the disease, there needs to be further study of aging with HIV, as well as understanding of the impact of various comorbidities.

In addition to a continued need to address HIV, the previous evaluation of the Federal Initiative found that there was an international movement over the last decade towards addressing HIV in a way that integrates other STBBI. Footnote 10 This movement is still underway, as these infections share common features, such as modes of transmission, at-risk populations, and risk behaviours. They also share social and structural risk factors, such as substance use, low levels of income, and limited social support. The movement to integrate can also be linked to a more generally integrated approach to disease that acknowledges the multiple biological and social factors that contribute to an excess burden from disease in some populations.Footnote 11

Within this context, PHAC led the development of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action in consultation with affected populations, federal, provincial, and territorial partners, Indigenous partners, and a broad range of stakeholders. This framework sets out an overarching and comprehensive approach to meet Canada's commitment on global STBBI targets, including HIV. The framework was officially endorsed in June 2018 by federal, provincial, and territorial ministers of health.Footnote 12

Alignment with Priorities

In 2015, the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) established global targets that, if reached, could end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. These targets also include the "90-90-90" targets, which state that, by 2020, 90% of all people living with HIV will know their status, 90% of those diagnosed will receive antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of those in treatment will have achieved viral suppression. Footnote 13 Achieving these targets will help eliminate HIV, because research shows that HIV-positive people who are on antiretroviral therapy, are engaged in care, and have an ongoing undetectable viral load do not transmit HIV to their sexual partners, and do not transmit HIV to their baby during pregnancy and delivery.Footnote 14

On World AIDS Day in 2015, the Minister of Health endorsed the UNAIDS and WHO joint targets and committed to work toward achieving them in Canada. Footnote 15 The first estimate for Canada was put forward using 2014 data. It was estimated that in Canada in 2014, 84% of all people living with HIV knew their status, 78% of those diagnosed were on antiretroviral treatment, and 89% of those in treatment had achieved viral suppression.Footnote 16

By 2016, Canada had made progress on all three of the 90-90-90 targets, with an estimated 86% of all people living with HIV knowing their status, 81% of those diagnosed in antiretroviral treatment, and 91% of those in treatment having achieved viral suppression. Footnote 17 Despite the progress made, there is still effort required to address HIV in Canada.

Alignment with Roles

The evaluation found that the work of the FI is well aligned with the legislated mandate of each of the federal partners. Documents reviewed, including those from program authorities, found that the Government of Canada is responsible for the following:

- public health laboratory science and services;

- surveillance;

- development of public health practice guidance;

- knowledge synthesis;

- program policy development;

- capacity building;

- awareness, education, and prevention for First Nations living on-reserve, Inuit, and federal inmates;

- creation of new knowledge through research funding;

- delivery of public health and health services to federal inmates; and

- support for community-based activities through grants and contributions funding.

Several external key informants interviewed viewed the Government of Canada as having an important role to play in national coordination and knowledge translation for HIV/AIDS prevention, care, treatment, support, and research. These roles were well communicated and well understood by external stakeholders. It was clear that there is some overlap between the Government of Canada's role and the role of other stakeholders, but this overlap was seen as complementary and not duplicative. For example, most key informants understood that the role of provinces is to support direct health care provision and treatment of HIV, hepatitis C, and other STBBI, whereas federal roles are related to prevention and health promotion. In some areas, provincial and territorial government roles overlapped with federal ones. For example, both provincial and territorial governments and the Government of Canada may develop strategies to achieve HIV/AIDS targets. Key informants indicated that this demonstrated complementarity rather than duplication, as strategic direction was aligned towards shared goals and reflected the distinct areas of responsibility and priorities relevant to a particular jurisdiction.

While the distinction between federal, and provincial and territorial roles was well understood, some thought that this distinction was artificial in light of the role of treatment as a prevention tool. Some key informants, including a few provincial representatives, expressed a need for the Government of Canada to promote preventive treatment, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PrEP has been shown to reduce the risk of contracting HIV by up to 92% among gay, bisexual, and other MSM, and heterosexual men and women who took the drug consistently, as compared to those who did not.Footnote 18

4.2 Performance - Achievement of Delivery Outcomes

Program Theory

The FI works toward decreasing the acquisition and transmission of new HIV infections. The first step to do so is increasing awareness and knowledge. When priority populations and target audiences are aware and informed of how infections are transmitted and acquired, they are better equipped to protect themselves and others. When priority populations and target audiences apply the knowledge they have gained, they will adopt behaviours to protect themselves and those who are at risk for HIV. These behavioural changes are what will ultimately lead to decreased rates of acquisition and transmission of HIV.

Each of the four FI partners conduct activities that contribute to the outcome areas of increased awareness and knowledge, knowledge use and application, strengthening capacity, and encouraging behaviour change. These activities vary based on the department and its mandate, and the needs of the populations it serves. Each department ultimately contributes towards decreasing the acquisition and transmission of new HIV infections.

4.2.1 Public Health Agency of Canada

PHAC activities have contributed to increased awareness and knowledge of ways to prevent the acquisition and transmission of HIV for both target audiences and priority populations. PHAC activities have also contributed to knowledge uptake and application in public health and sexual health practices. Still, there are opportunities to promote knowledge application further by extending the reach of FI-developed knowledge products.

Over the five years covered by the evaluation, PHAC conducted a variety of activities that have increased awareness and knowledge. For example, they collaborated with global partners to promote the use of its modelling tool to improve calculations of estimates of HIV incidence and prevalence, and of the proportion of undiagnosed cases. The tool was endorsed by the UNAIDS Reference Group and, as a result, will be incorporated in the UNAIDS Spectrum software for global HIV estimation used by other governments domestically and internationally, as well as by academia and researchers.Footnote 19

In addition, over the same period, PHAC published a variety of documents to inform target audiences. This included guidelines on HIV testing, routine surveillance reports, enhanced surveillance reports, and Epi Updates, as well as studies and presentations for conferences. In addition, over 18 HIV-related webinars were offered by PHAC between 2013-14 and 2017-18. Interview data indicated that PHAC's HIV-related knowledge products and webinars were informative and appreciated.

The results of a survey administered in 2016 demonstrate that, in addition to increasing target audiences' knowledge, PHAC also contributed to the uptake and application of HIV knowledge in public health practice. Footnote 20 It was found that, of the respondents who were aware of PHAC's HIV Screening and Testing Guide, over 80% reported incorporating recommendations from the guide into their practice. Survey data also revealed that, while the uptake of the Guide was high among people working in sexual health, it was low among primary care practitioners (i.e., family or general practitioners who do not have this specialization).

Community organizations funded by PHAC collected data that demonstrated increased awareness and knowledge from priority populations and target audiences who participated in the activities they offer. Between 75% and 89% of participants, depending on the year, reported increased knowledge following their participation in an offered activity. Furthermore, data collected on activities aimed at reducing stigma from service providers showed that these activities resulted in increased awareness and knowledge from participants, and contributed to them modifying their practices to better meet the needs of the priority populations with whom they interact.

The Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange (CATIE) is Canada's official knowledge broker for HIV and hepatitis C, and is funded in part by PHAC. CATIE connects health care and community-based service providers with science and good practices related to these STBBI. Footnote 21 Through CATIE, PHAC has contributed to increased knowledge and awareness among priority populations and target audiences. Interactions with CATIE have also led to target audiences using this knowledge in their practice. For example, a 2017 national survey of frontline workers, conducted by CATIE, showed that 96% of respondents reported that the knowledge broker's services and resources had increased their knowledge of HIV. Footnote 22 Moreover, 91% of respondents reported using information from the knowledge broker to educate or inform clients, health professionals, colleagues, and members of the public. Footnote 23 The same survey also identified that 77% of frontline service providers surveyed had used the knowledge broker's programs, services, tools, and resources to change work practices and implement or change their programming. Some specific examples of changes made include improved counselling, improved patient education, and improved communication with clients.

Information Gaps

Some stakeholders interviewed also expressed a need for PHAC to further support, within the limits of its role, the uptake and application of new knowledge (e.g., new testing technology, preventive technology such as PrEP), either by issuing guidance or supporting guidance issued by others. It was also stated that having federal guidance often provides stakeholders with the additional traction needed to apply new knowledge in their own practices.

The results of a 2018 survey also identified information needs related to gaps in awareness and knowledge among Canadians regarding HIV. For examples, only 26% of Canadians knew that an HIV-positive person on treatment who has achieved viral suppression cannot transmit the virus to others. The same survey's results also identified that 84% of Canadians are not aware or do not believe that a pill, such as PrEP, can help prevent HIV infection. The survey did not, however, look at awareness of PrEP among populations at risk.

Increasing Community Capacity and

Links to Care

In 2016, as several Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan were in need of better understanding of the extent of the HIV and hepatitis C epidemics in their communities, they enlisted the help of PHAC laboratories to find a culturally appropriate testing intervention.

The testing technology used was dried blood spot (DBS) testing, a method where blood is drawn with a pinprick from a person's finger and then applied to a specially designed card. Once dried, the card is simply mailed to the PHAC Laboratory where it is tested for blood-borne infections such as HIV and hepatitis C. DBS testing requires little training in order to be administered and is minimally invasive. Key informants reported that the technology was highly accepted by the population.

Data collected through document review and key informant interviews indicates that this initiative allowed communities to dramatically increase access to testing for their population. Footnote 24, Footnote 25 Key informants also stated that PHAC laboratories and local community health authorities worked together to ensure that appropriate linkages to care were in place for treatment upon confirmation of a positive test result.

PHAC Laboratories are currently working on expanding DBS testing to other communities.

The results of a 2018 survey also identified information needs related to gaps in awareness and knowledge among Canadians regarding HIV. For examples, only 26% of Canadians knew that an HIV-positive person on treatment who has achieved viral suppression cannot transmit the virus to others. The same survey's results also identified that 84% of Canadians are not aware or do not believe that a pill, such as PrEP, can help prevent HIV infection. The survey did not, however, look at awareness of PrEP among populations at risk.

There was evidence that PHAC activities have strengthened capacity for target audiences and priority populations and promoted changes in personal behaviour. There are opportunities to increase the overall effectiveness of PHAC's activities further by ensuring that they adequately reach the most affected priority populations.

Program documents show that, over the years, PHAC laboratories have helped build capacity for clinical laboratories in Canada and internationally. For example, in 2015, PHAC was re-accredited as a WHO specialized global drug resistance laboratory in the WHO/HIVResNet network. In this capacity, PHAC has developed a series of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)-based HIV drug resistant assays, which both reduce the cost of HIV drug resistant surveillance and significantly improve the sensitivity of an analysis. In addition, PHAC has developed a web-accessible NGS drug resistant analysis system referred to as HyDRA, suitable for handling the massive amounts of sequence data generated by NGS. Technology transfer was provided to several laboratories (in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Puerto Rico) and assistance was also extended to a WHO ResNet laboratory in Uganda. Footnote 26

Furthermore, PHAC laboratories provided quality assurance programs for markers, or physiological characteristics, of successful HIV care and treatment. These quality assurance programs were provided to over 40 laboratories across Canada and over 1,400 laboratories internationally, through the Quality Assessment and Standardization for Immunological Measures program. This has resulted in a demonstrable increase in the quality of HIV testing within Canada and around the world.Footnote 27

Linkages to testing and care are essential to the adoption of behaviours that prevent HIV acquisition and transmission. Year after year, community-based projects have reported large numbers of referrals to services. However, literature has shown that linkage to care alone is not enough; it is essential that HIV-positive individuals also remain in care. As such, it has been estimated that between 11 and 24% of HIV-positive Canadians stop attending follow-up HIV appointments, putting them at a heightened risk to develop serious complications. Footnote 28 This issue is especially prevalent among priority populations facing barriers, such as poor access to services, stigma and discrimination, poverty, food insecurity, homelessness, and mental health and addiction issues.Footnote 29

In addition to linking individuals to care, some funded community-based projects are also working on increasing priority populations' capacity to better manage their health. In 2015-16, performance data showed that 91% of participants in these projects had reported an increased ability to better manage their health. Performance data also showed that, depending on the year, 75% to 85% of community-based project participants reported a strong intention to adopt healthier behaviours related to sexual practices and drug use that they had learned about through the project.

While participants reported positive results from attending community-based programs, the evaluation found that the overall effectiveness of these programs may have been lower than the data suggests, due to a limited reach to the most at-risk populations. As such, gay, bisexual, and other MSM only accounted for 10% and 11% of the population reached by activities conducted in 2015-16 and 2016-17, although surveillance data indicates that this population accounted for over 52% of new HIV cases in 2016.

While Indigenous populations have accounted for 10% and 17% of the population reached over the last two years of the evaluation period, subject matter experts interviewed have indicated that it is not the Indigenous population at large that is at risk for HIV, but more precisely the portion of the Indigenous population who uses intravenous drugs. Surveillance data from 2016 indicated that, of the HIV cases attributed to injection drug use, 59% represented Indigenous people. The data, as was collected by community-based projects during this period, did not give a clear picture of how much of this sub-population was being reached.

It was, however, encouraging to note that a few external stakeholders had reported, with the recent implementation of the Community Action Fund, an increase in activities targeting gay, bisexual, and other MSM. In addition, recent investments made under the Harm Reduction Fund have also targeted people who use injection drugs.

4.2.2 Canadian Institutes of Health Research

CIHR's FI activities have supported HIV/AIDS-related knowledge creation. There is indication that knowledge produced is being used by others, thus influencing public health practices and health outcomes.

In accordance with its HIV/AIDS Research Initiative: Strategic Plan 2015-2020, CIHR has supported the production of HIV/AIDS research in key areas such as biomedical and clinical research, health services, population health research, and community-based research.

Canada has contributed significantly to the international body of HIV/AIDS research through peer-reviewed publication. A bibliometric analysis conducted as part of this evaluation found that Canada ranked fourth out of the top 10 countries on the specialization index in the field of HIV/AIDS between 2010 and 2017. The specialization index is a measure of the relative publication intensity of a country in the priority area of HIV/AIDS, as compared to the publication intensity across the world in the same research area. Two indicators used to estimate the scientific impact of publications on HIV/AIDS research are the Average Relative Citations (ARC) and the Average Relative Impact Factor (ARIF). ARC refers to the number of times a published paper was cited over the three-year period following its publication, whereas ARIF is an index that measures the scientific impact of the journals where the research is published. Between 2010 and 2017, Canada was ranked fifth out of the top 10 countries for ARC and sixth for ARIF.

To better support the use of research, CIHR has requested that grant recipients have a knowledge translation strategy included in their research. There are two approaches to knowledge translation for CIHR. Footnote 30 One is called "end of grant knowledge translation", and includes the typical dissemination and communication activities undertaken by most researchers, such as knowledge translation to their peers through conference presentations and publications in peer-reviewed journals. Footnote i The other is called "integrated knowledge translation", and consists of having researchers and research users collaborate to shape the research process by determining research questions, deciding on methodology, being involved in data collection and tools development, interpreting findings, and helping disseminate research results. It should be noted that several of the researchers interviewed highlighted that the second approach to knowledge translation has the additional benefit of making research more relevant to the needs of knowledge users.

In 2016-17, 73% of grant recipients reported that knowledge translation activities had led to effective knowledge translation and the creation of more effective health services and products, while 30% of grant recipients reported that their research activities led to information and guidance for patients or the public. These numbers increased to 83% and 41% respectively for 2017-18.Footnote 31

CIHR activities have been effective at supporting HIV research capacity, and were seen as having an impact on target audience and priority population capacity.

Through the Canadian HIV/AIDS Trials Network (CTN), CIHR has made a significant contribution to supporting a new generation of HIV researchers in Canada and facilitating a supportive network for them. In particular, the post-doctoral fellowships within the CTN have helped attract clinicians to the field of HIV research, many of whom have continued to work at the CTN and attain leadership positions there. From 1992 to fiscal year 2015-16, 139 peer-reviewed awards were allocated to 84 researchers. Between 2014-15 and 2017-18, an average of eight fellowships were awarded each year. Key informants working in junior research positions at the CTN described the supports available to help develop their career, including opportunities to be mentored by more experienced researchers and to apply for pilot study funding with a senior researcher, thus providing an opportunity to gain additional hands-on experience. Several of these researchers indicated that the CTN provided development opportunities that would not otherwise have been available.

Uptake of Knowledge by Policy Makers and Clinicians

CTN researchers have produced research on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), which provincial policy makers and clinicians have used to make informed decisions about its use. As such, the province of Ontario consulted with these CTN-supported researchers to help determine coverage for PrEP when updating the Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary. CTN-supported researchers also published clinical guidelines on the use of PrEP in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 2017.

Another key value of the CTN is its ability to foster collaboration between researchers working in various disciplines, as well as enabling connections with other relevant national and international networks. All CTN researchers interviewed indicated that the CTN had helped facilitate collaboration across disciplines in Canada, including social workers, clinicians, and community-based researchers.

CIHR has also contributed to capacity building through the CIHR HIV/AIDS Community-Based Research (CBR) Program, a component of the CIHR HIV/AIDS Research Initiative. Footnote 32 CBR supports partnerships between community leaders and researchers to carry out research and capacity-building initiatives relevant to communities engaged in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Footnote 33, Footnote 34 CIHR also has a CBR branch dedicated to Indigenous communities. CBR aims to involve community residents in the full research spectrum through conception, design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, conclusions, and communication of results. Key informants interviewed see CBR as influencing change in community health systems, programs, and policies. Program documents and external key informant interviews highlighted that not only are these studies generating new knowledge, but they have also increased the skills and capacity of communities participating in them. Several stakeholders expressed a desire for more of this type of research. The evaluation also found that it was not clear to all key informants interviewed if CBR research funds could be held by communities or only by academic organizations. Within this context, there are opportunities for CIHR to better communicate to communities about the CBR Program.

Below are examples of how CIHR HIV/AIDS research funding has supported community capacity and improved treatment options:

- A research grant that addressed prevention of HIV and other STBBI among young gay, bisexual, and other MSM, has resulted in the scaling up and rolling out of two projects. The first is GetCheckedOnline, a free and confidential online sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing service, and the second is Mpowerment, a program that helps young MSM living with HIV to engage in the HIV treatment cascade. The success of this grant was due to providing youth participants with an opportunity to contribute meaningful feedback directly to decision makers, based on their own experiences, preferences, and perceived gaps. By incorporating young men's feedback during the rollout and scale-up of both projects, care managers were now able to ensure that they had tailored sexual health services specifically to these end-users, thus increasing the odds of reaching their target audience. In addition, the online availability of STBBI testing across a province or territory may have had an important impact on broader health care practices (e.g., cost savings). Scale-up of GetCheckedOnline in two new health authorities has been well received, and Mpowerment has successfully scaled up in two new communities.Footnote 35

- A small team of Alberta researchers explored biomarkers and community management of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Discovery of these types of biomarkers represents a major advance in HIV research. This new knowledge has the potential to accelerate early diagnosis and treatment of HIV in newborns. As well, it was found that managing HIV in the community, relative to health facilities, may be more cost effective. Mothers and children who participated in this study benefitted from improved diagnostics and clinical care, relative to the norm in the public health system.Footnote 36

4.2.3 Indigenous Services Canada

ISC activities have contributed to increased awareness and knowledge to prevent the acquisition and transmission of HIV, for both target audiences and priority populations. ISC has also contributed to increased community capacity and knowledge application, which can facilitate behavioural change.

Program documents reviewed show that community funding has supported activities to increase knowledge of prevention, care, treatment, and sexual health. ISC's First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) has conducted a variety of HIV/AIDS work, including raising awareness and knowledge among First Nations people. This work was done through community health centres and nursing stations that provide culturally sensitive awareness sessions, print materials, presentations, and workshops. Funding in First Nations communities has supported training to increase knowledge in care, prevention, treatment, and sexual health.

FNIHB projects have also provided training to staff and volunteers to increase knowledge and skills. In addition, funded projects have carried out capacity-building activities to develop the skills of community health nurses. For example, community nurses in Québec have been receiving specialized training to provide them with the knowledge required to order HIV and other STBBI tests, which are typically ordered by physicians.

In 2016-17, 83% of First Nations communities reported that HIV testing was accessible on or near the reserve. Unfortunately, progress on this indicator cannot be compared over time, as data on it was not collected systematically.

While the above results can be seen as encouraging, evidence collected also shows that HIV/AIDS stigma and denial, and low access to services, remain problematic for several communities. As such, ISC has been working closely with non-governmental organizations to support communities that have decided to undergo a community readiness assessment. A community readiness assessment is a model for community change that integrates the community's culture, resources, and level of readiness to more effectively address issues such as HIV, hepatitis C, and drug use, among others. Community readiness assessments bring the community together, build cooperation, and increase internal capacity for prevention and intervention. Readiness is "the degree to which a community is prepared to take action on an issue". There is growing evidence that such assessments empower communities to better understand the problems they are facing in relation to HIV, as well as to take ownership of how they will address these problems moving forward.

Saskatchewan's Know Your Status (KYS) program was provided as an example of an initiative that followed a community readiness assessment. The KYS program is credited for providing awareness and knowledge of HIV to communities in a culturally appropriate manner, and for offering testing services and linkages to care. Over the years, KYS has expanded beyond testing to include treatment, harm reduction, food assistance, and mental health counselling to the 2,800-plus people living on reserve. Footnote 37 The health directors of one of the communities that implemented the KYS program reported that the program had resulted in increased undetectable viral loads among their HIV-positive members, and that HIV stigma within the community had decreased, as they could now see patients walking into the health clinic, "while holding their head up high".Footnote 38

The most recent estimates for all First Nations communities in Saskatchewan, which includes over 80 on-reserve communities, showed that, by the end of 2016, it was estimated that 77% of the individuals known to be diagnosed with HIV were on treatment, and 75% of those on treatment had achieved viral suppression. Footnote 39 This marks the first time such estimates were done for this specific population. Future estimates will help measure progress.

Populations in remote areas face more barriers accessing testing services than those in denser metropolitan areas. Footnote 40, Footnote 41 Interview data also revealed that stigma remains a challenge hindering testing and access care or support services. It was reported that individuals in remote communities are often put in situations where they have to disclose their condition to people they don't necessarily trust, in order to access services. Key informant interviewees noted that there are often histories of abuse and violence linking one person to another, which can result in people not accessing care. For example, it was reported that an HIV-positive woman did not use community transport for her follow-up medical appointments, resulting in interrupted treatment, because she did not want to face the driver of the transport, who had allegedly abused a member of her family, and she had no other means of transportation to access treatment.

It was also reported that, because of other factors linked to larger social determinants of health, many individuals do not have the capacity to remain on treatment or be fully compliant with it. Substance use, violence, poverty, low levels of education, and mental health issues, such as depression, low self-esteem, etc., were often cited as factors contributing to many individuals falling out of care or not being compliant with treatment (e.g., skipping doses, forgetting appointments, forgetting to refill prescriptions).

ISC is working with communities to improve conditions for other factors that negatively affect the individual's ability to manage their health and to remain in care. Key informants highlighted a need for communities to not only link people to care, but also provide them with services, such as mental health support, that help them manage their overall health.

4.2.4 Correctional Service Canada

CSC activities have contributed to increased awareness and knowledge of ways to prevent the acquisition and transmission of HIV among inmates. CSC's activities are also strengthening inmates' capacity to prevent and control HIV transmission, which in turn contributes to behavioural change.

Providing Knowledge and Capacity to Federal Inmates

As part of CSC's health promotion initiatives, the Peer Education Course (PEC) and Aboriginal Peer Education Course (APEC) provide inmates with knowledge and skills to lead healthier lives and prevent the acquisition and transmission of infectious diseases, including HIV, both while incarcerated and in the community.

The PEC and APEC courses themselves are well attended and well received by inmates. The courses also prepare select inmates to act as peer workers within their institution. Peer workers are well placed to share information in a way that resonates with other inmates, helping them make healthier choices.

Peer workers also provide valuable information to other health care workers in the institution. For example, they can report on trends they are seeing or hearing from others, and nurses can provide more relevant care as a result.

Internal key informants indicated that the PEC and APEC programs have played a key role in CSC achieving the 90-90-90 targets for federal inmates.

Through initiatives such as the Reception Awareness Program, health fairs, and the Peer Education Course (see box below), CSC contributes to increasing inmates' awareness and knowledge to prevent the acquisition and control the transmission of HIV and other infectious diseases.Footnote 42

Federal correctional facilities offer all inmates a health assessment on admission, and in 2016, 96% of newly admitted inmates accepted a voluntary HIV test to know their status. Inmates are also referred for, or can request, HIV testing any time during incarceration.Footnote 43

CSC contributes to behavioural changes by ensuring that inmates who are diagnosed are offered treatment. Harm reduction interventions (e.g., access to bleach, condoms, dental dams) are also available to inmates, as well as opioid substitution therapy. Harm reduction interventions have been shown to reduce the negative outcomes associated with dangerous behaviours, such as drug use, and to limit the risk of infectious disease, such as HIV.Footnote 44

During the evaluation, CSC was working on expanding its suite of harm reduction initiatives in accordance with recommendations from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes. In June 2018, CSC implemented a needle exchange program in two of its institutions and in January and February 2019, announced implementation in an additional three institutions. This phased approach will be followed as implementation continues at other institutions across Canada.

Within this context, CSC has already achieved the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets for its population. As of April 2017, among the 170 inmates diagnosed with HIV, 94% were on treatment, and 91% of those on treatment with known viral load results had suppressed viral loads. Footnote ii Footnote 45

Still, studies show that, when released, HIV-positive inmates are at an increased risk of not continuing in care. Footnote 46, Footnote 47 To help prevent this, CSC has been progressively working with non-governmental organizations to establish a network of linkages to care outside of the institution and is working on expanding this network, as interview data has shown that such linkages are not yet available in all regions. Some NGOs and provincial public health key informants stated that they would like to see CSC work more closely with NGOs to ensure continued care in the community after release. They also added that CSC could work more closely with provincial institutions to share best practices and lessons learned.

4.3 Efficiency and Economy

4.3.1 Achievement of Governance Outcomes

Program Theory

Because the responsibility for the achievement of the FI outcomes is shared between partners, robust horizontal governance, joint planning, and the delineation of authority are critical. In addition, other levels of government and non-governmental stakeholders largely make up the mechanisms through which FI outcomes are achieved. Thus, enhanced engagement with these stakeholders is also essential to the success of the FI. In return, successful governance among FI partners and enhanced engagement with stakeholders will support a coherent federal response. This is done through the adoption of shared directions and approaches by partners, stakeholders, and target audiences, both domestically and globally. This will also support the current priority and global trend to integrate HIV response with actions to prevent and control related STBBI, as they share common risk factors, priority populations, and transmission routes.

The evaluation found that FI governance has fostered a high level of information exchange and collaboration between federal partners. There is also evidence that FI partners collaborate with stakeholders and have mechanisms in place to ensure that stakeholders are consulted on various files.

The FI Responsibility Centre Committee (RCC) provides a platform for FI partners to exchange ideas, and fosters a high level of collaboration between the four federal partners who share responsibility for implementing the FI. The RCC is intended to provide a forum where participants can:

- identify and review annual priorities;

- share information and advance collaboration on cross-cutting activities and priorities that contribute to the achievement of FI outcomes;

- develop management responses to address evaluation recommendations, as well as other required reporting; and

- develop parliamentary reporting for the FI.

Evaluation evidence suggests that the RCC has been an effective platform for oversight of the FI, and has delivered on its outcome to improve coherence and coordination between federal partners.

Documents and feedback from internal key informants suggest that the RCC has been successful at bringing federal partners together to share information in open dialogue. Overall, most key informants with direct knowledge of the RCC suggested that the committee's greatest strength was improving communication and information flow between federal partners.

Internal key informants who had participated in RCC meetings noted that, over the years, the committee has improved its focus on acting strategically, which supports alignment between partners beyond the exchange of information.

Despite strong information sharing and joint planning, some key informants identified opportunities for improvement as they relate to the current governance model. For example, some internal key informants suggested participation in the RCC be expanded, given that the Government of Canada's response to HIV has expanded to integrate with the response to other STBBI, in the context of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action.

Key informants interviewed also identified examples of projects that exemplified strong collaboration between the FI partners and other stakeholders. This included collaboration between the four federal partners and other federal departments to prepare for presentations over multiple years of International AIDS conferences. Such collaboration has supported a coherent Canadian presence nationally and internationally.

Another example of strong collaboration, not only between FI partners, but also with provincial representatives and regional NGOs, was the Collective Impact Network in Manitoba. The NGO "Nine Circles" facilitated the creation of the Collective Impact Network that has brought together representatives from the province, PHAC, ISC, regional NGOs, Indigenous organizations, researchers, and health care professionals to collaborate on addressing HIV in Manitoba. It has supported activities including knowledge transfer and exchange, deliberative discussions, policy change, practice change, education, and research. Footnote 48

Advisory Committees

The FI also ensures proper stakeholder engagement through the use of advisory committees. Over the evaluation period, two committees provided advice to the Minster of Health to support PHAC activities, and a third committee provided advice to the Scientific Director of the CIHR Institute of Infection and Immunity.

Up until 2018, the Ministerial Advisory Council on the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS (MAC-FI) provided strategic advice to the Minister of Health and was comprised of subject matter experts with experience in STBBI and related factors. The National Aboriginal Council on HIV/AIDS (NACHA) provides Aboriginal-focused advice to PHAC and ISC, and is comprised of members with experience in HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, other STBBI, and the health of Indigenous people.

A review of committee records indicates that both committees have engaged membership and have provided advice to inform the Minister of Health. The two committees also shared information with each other and collaborated on various projects, including providing joint advice to the Minister after reviewing lessons learned from the response to HIV in Saskatchewan.

Discussions between PHAC, MAC-FI, and NACHA highlighted the need for more effective, relevant, and timely advice moving forward, in keeping with the Government of Canada's commitment to increase its engagement with Canadians and stakeholders. In light of this changing landscape, it was determined that MAC-FI would not be renewed beyond 2018, in favor of more regular engagement opportunities with people living with HIV and stakeholders by the Minister and government officials. Work is currently underway, in collaboration with NACHA and Indigenous partners, to identify a new model for Indigenous engagement, in keeping with efforts to move towards reconciliation.

For CIHR, advice from the CIHR HIV/AIDS Research Advisory Committee (CHARAC) is used to guide the implementation of the CIHR HIV/AIDS Research Initiative. Committee membership consists of researchers and other representatives from across the full spectrum of HIV/AIDS research and other relevant areas in Canada. CHARAC includes representatives from multiple Canadian community organizations and PHAC partners, and its membership reflects gender, geography, and matters related to priority populations, including gay men's health. The committee also includes dedicated representation of individuals with expertise in various areas related to HIV/AIDS, including virology and immunology, Indigenous health issues, mental health and addiction, sex and gender health, population health and health services, and policy research. Representation also includes experts in community-based research.

The CHARAC body was viewed as a highly effective advisory board by individuals working on CIHR-funded FI programming. In general, key informants viewed this advisory board's contributions as valuable, and it was seen as enhancing engagement with both experts and community representatives to improve the relevance of CIHR's work. Several key informants described openness from CIHR to CHARAC's suggestions, and described seeing their CHARAC discussions reflected in funding calls. They stated that CHARAC has helped advance community voices within CIHR's work. CHARAC was viewed positively by both researchers and community members working with CIHR-funded programs.

The federal HIV response is seen by internal and external stakeholders as being coherent overall. Still, some stakeholders, including provinces, identified that additional actions that often fall outside FI partners' respective mandates are needed to address stigma and discrimination related to HIV and other STBBI, and increase overall testing access.