Zika virus: For health professionals

Prior to May 2023, serology testing was recommended for individuals meeting testing criteria but outside of the acute phase of the disease. Based on data that has accumulated since Zika virus became more widespread, it has become apparent that IgM can persist for prolonged periods of time and that cross reactivity with other viruses makes interpretation difficult. As a result, the updated recommendations no longer recommend serology.

On this page

- What health professionals need to know about Zika virus

- Agent of disease

- Spectrum of clinical illness

- Testing

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Surveillance in Canada

- Zika virus cases in Canada

- How Canada monitors Zika virus

- Zika virus around the world

- Related information

- Tip sheets for print

- Posters to share

What health professionals need to know about Zika virus

Zika virus is a potentially neurotropic virus that is capable of entering the nervous system and targets neural progenitor cells. Zika virus is transmitted primarily as a mosquito-borne infection; it can also be transmitted sexually and through blood and tissue products.

Zika virus RNA has been found in the serum, saliva, urine, semen and vaginal secretions of infected individuals. Of all of these body fluids it is known to persist the longest in semen. Isolation of infectious Zika virus, as opposed to the detection of RNA, is the best indicator of transmission risk. A review of the currently published literature found that 69 days was the longest period after symptom onset at which replication-competent virus has been detected in semen by culture or cytopathic effect.

Exposure to Zika virus during fetal development increases the risk of severe health outcomes, such as congenital Zika syndrome. For this reason, travellers to Zika-affected countries or areas should wait before trying to conceive:

- Individuals who may become pregnant should wait 2 months after travel or after onset of illness due to Zika virus (whichever is longer) to allow sufficient time for a possible Zika virus infection to be cleared from all body fluids.

- Since Zika virus has been found in the semen of some infected individuals for a prolonged period of time, the partner of any individual trying to conceive should wait 3 months after travel or after onset of illness due to Zika virus (whichever is longer).

The 3-month recommendation takes into consideration the currently available data regarding how long infectious Zika virus can be found in semen. Returning travellers who have a pregnant partner should:

- always use a condom correctly, or

- avoid having sex for the duration of the pregnancy

To prevent potential sexual transmission in general it is recommended that all travellers returning from Zika-affected countries or areas always use condoms correctly, or avoid having sex:

- Partners of individuals who may become pregnant should take these precautions for 3 months after travel or after onset of illness due to Zika (whichever is longer),

- Individuals who may become pregnant should take these precautions for 2 months after travel or after onset of illness due to Zika (whichever is longer).

To help advise your patients who are planning to travel, you may want to inform travellers about mosquito bite prevention measures.

For additional detail, review The Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) Recommendations on the Prevention and Treatment of Zika Virus for Canadian health care professionals.

Agent of disease

Zika virus is a single stranded RNA flavivirus and a member of the Flaviviridae family.

There are at least 2 Zika virus lineages which are the:

- Asian lineage

- African lineage

The strains circulating in Pacific islands and the Americas likely evolved from a common ancestral strain in Southeast Asia.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is:

- the primary vector of Zika virus

- largely restricted to tropical and subtropical regions, though temperate populations may occur in isolated refuges

The Aedes albopictus mosquito has also been implicated as a vector, though its role in the 2015-16 outbreaks is uncertain. This species is widely present outside the tropics.

In the past few years, Aedes albopictus species have been found in Windsor, Ontario as a result of enhanced surveillance. A very small number of Aedes aegypti adults and larvae have also been detected in this area. It is not known whether populations of these species have been able to over-winter in Windsor or if they are being repeatedly introduced through cross border transportation between Canada and the U.S.. Studies are on-going to define the risk from the relatively recent introduction of these two mosquito species into this part of Ontario. In addition, a single egg of Aedes aegypti was detected during 2017 in southern Quebec during an enhanced surveillance study designed to detect these invasive Aedes mosquitoes. All of the Aedes mosquitoes from the Windsor area tested negative for Zika virus. The egg from the Quebec study was not tested, due to the small sample size, however mosquitoes become infected with Zika when they feed on a person already infected with the virus and very rarely from female mosquitoes to their eggs.

Currently, the mosquitoes that transmit Zika virus are not established in Canada due to the climate. So, there is a very low probability of mosquito transmission in Canada.

These two species of mosquito also transmit dengue and chikungunya viruses.

Zika virus is related to same taxonomic group of viruses (ie. flaviviruses) that cause:

- dengue

- West Nile virus

- St. Louis encephalitis

- Japanese encephalitis

Spectrum of clinical illness

Asymptomatic infections are common. Only 1 in 4 people infected with Zika virus are believed to develop symptoms.

The main symptoms of Zika virus infection include:

- retro-orbital pain

- low-grade fever (37.8 to 38.5 °C)

- general non-specific symptoms, such as:

- myalgia

- asthenia

- headaches

- transient arthritis or arthralgia with possible joint swelling

- mainly in the smaller joints of the hands and feet

- maculopapular rash often spreading from the face to the body

- conjunctival hyperaemia or bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis

The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days. The symptoms are usually mild and last for 2 to 7 days. Most people recover fully without severe complications and only require simple supportive care. Hospitalization rates are low.

Infection may go unrecognized or be misdiagnosed as:

- dengue

- chikungunya

- other viral infections causing fever and rash

Zika virus infection can lead to neurological syndromes and complications. Neurological conditions associated with Zika virus infection include:

- congenital Zika syndrome

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS)

- and less commonly:

- Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

- Acute transient polyneuritis

- (Meningo) encephalitis

- Myelitis

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- Encephalopathy

A small number of deaths associated with Zika virus infection have been reported in children and adults with comorbidities and weakened immune systems.

Congenital Zika syndrome

Congenital Zika syndrome is a distinct pattern of structural and functional defects that develop following congenital Zika infection and is characterized by the following 5 features:

- microcephaly, with partially collapsed skull

- abnormal brain development including:

- cerebral atrophy

- callosal hypoplasia

- diffuse subcortical calcification

- thin cerebral cortices and abnormal cortical development

- marked early hypertonia and symptoms of extrapyramidal involvement:

- seizures

- spasticity

- irritability

- club foot and arthrogryposis

- chorioretinal atrophy, focal pigmentary mottling and other ocular anomalies

Not all babies born with congenital Zika infection will have all of these problems. Infants with a normal head circumference at birth can still have brain abnormalities consistent with congenital Zika syndrome. Some who do not have microcephaly at birth may later experience slowed head growth and develop postnatal microcephaly. The full spectrum of poor outcomes caused by Zika virus infection during pregnancy remains unknown.

Birth defects were reported in similar proportions of fetuses and infants whose mothers did and did not report symptoms during pregnancy. Defects were reported among all trimesters, although there was a higher likelihood if the mother was infected during the first trimester.

Findings from the US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry (United States and United States Territories) found that approximately 1 in 20 fetuses or infants whose mothers had Zika virus infection during pregnancy had congenital anomalies.

When analysis was restricted to confirmed Zika virus infections in the first trimester, approximately 1 in 10 fetuses or infants had a possible Zika virus-associated congenital anomaly.

A study (based on data from the US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry) published in August 2018, found that of 1450 children 1 year of age or older who received follow-up care:

- 6% had at least one Zika-associated birth defect,

- 9% had at least one neurodevelopmental abnormality possibly associated with congenital Zika,

- 1% had both.

Since these data are based on children who received follow-up care (defined as clinical care at age >14 days and reported to the registry) the reported proportions may not be representative of the entire cohort of children born to mothers with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy. However this report does highlight the need for ongoing monitoring and evaluation of children born to mothers with evidence of Zika infection during pregnancy in order to facilitate early detection of possible disabilities and prompt referral to support and intervention services.

Babies with congenital Zika syndrome often experience significant developmental challenges, including difficulty sleeping, feeding, communicating and controlling muscular movement. They also often experience seizures and hearing and vision problems. It is important to note that babies affected by Zika virus may require specialized care during their lives.

Data on mortality associated congenital Zika virus infection is still not widely available, but some studies have shown increased mortality rates in the fetal and perinatal stages.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

The association between Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) and Zika virus infection was first established in a case-control study in French Polynesia. Studies of the 2013-14 outbreak in French Polynesia estimated that around 1 in 4000 people with Zika virus infection developed GBS as a complication. Over 20 countries have reported a temporal association between clinical symptoms of Zika virus infection and the onset of GBS. Furthermore, a correlation has been noted between the decline in Zika incidence and decreased GBS rates.

Several other infections can trigger GBS (e.g., Campylobacter jejuni, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis E). In a study comparing hospitalized patients with and without GBS the authors found that the odds of having recent Zika virus infection were more than 30 times higher in the patients with GBS. The authors controlled for other infections that can trigger GBS but did find that many of the patients also had antibody reactivity to dengue viruses. These findings were reported by the WHO as part of a systematic scientific literature review and led the WHO to conclude in 2016 that "the most likely explanation of available evidence from outbreaks of Zika virus infection and Guillain-Barré syndrome is that Zika virus infection is a trigger of GBS".

Testing

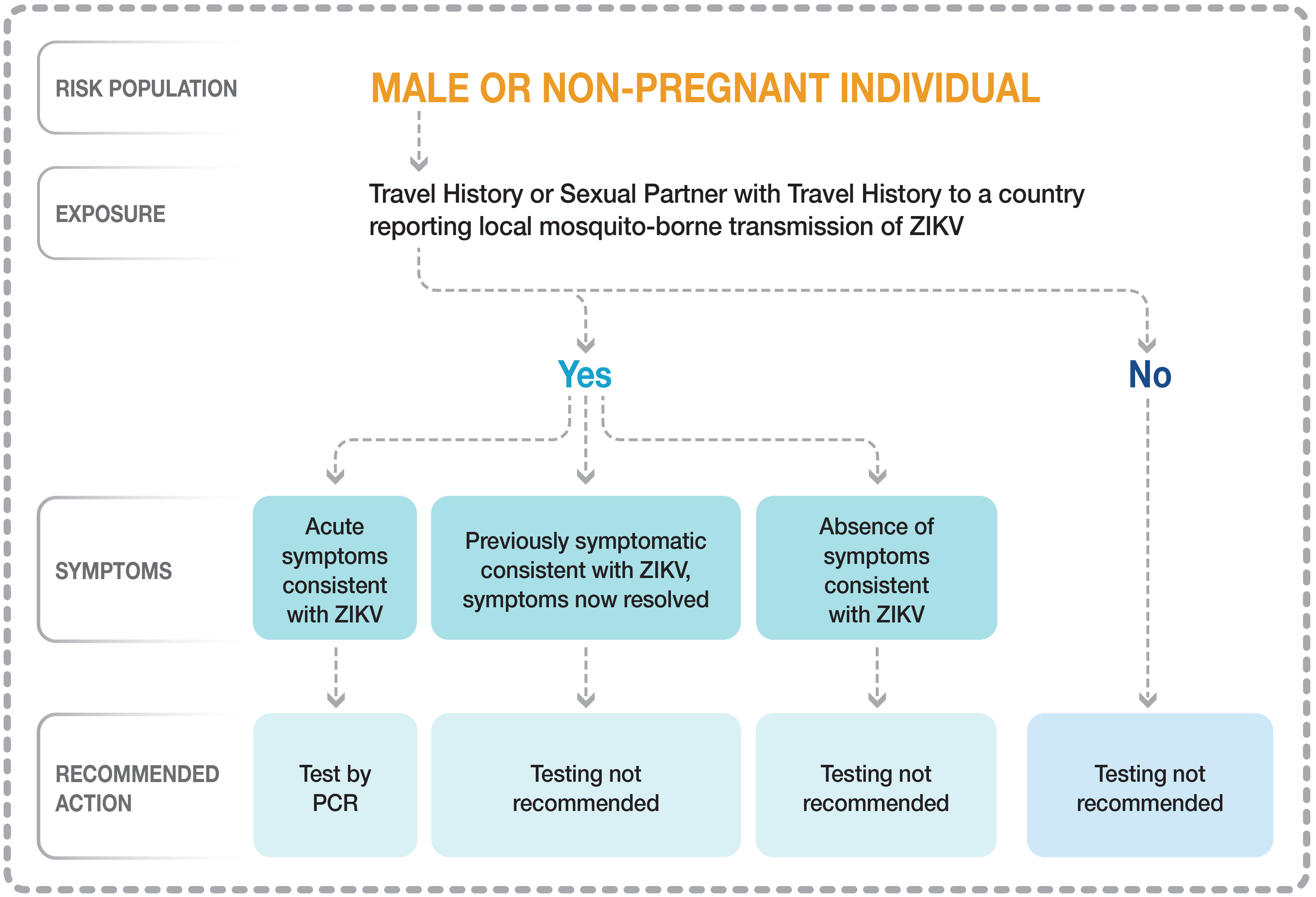

The decision to offer Zika testing to adults is described in the decision-tree for Zika virus laboratory testing.

Decisions to test should consider:

- travel history

- population at risk

- presence of symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection

- possible non-travel related exposures, for example, sexual transmission

The workup for potential Zika virus infection in pediatric patients, particularly infants born to individuals affected in pregnancy, can involve some additional non-laboratory testing.

Decision-tree for Zika virus laboratory testing

Figure 1 - Text description

This image is a decision-tree intended to help health care professionals make decisions related to Zika virus laboratory testing.

1. The first question relates to the risk population: is the patient male/non-pregnant individual or pregnant individual?

Male or non-pregnant individual

If the patient is male or a non-pregnant individual

2. Do they have a travel history or a sexual partner with a travel history to a place reporting local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus infection?

If the answer is "no," testing for Zika virus infection is not recommended. Zika virus infection is unlikely without travel or exposure history.

3. If the answer is "yes" for travel history for the male or non-pregnant individual, choose from 3 options:

- "The patient is experiencing acute symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection."

- "The patient was previously symptomatic consistent with Zika virus infection and the symptoms have now resolved."

- "The patient has had no symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection."

If the answer is "yes" for travel history for the male or non-pregnant individual and:

3.A that patient is experiencing acute symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection, PCR testing is recommended but serological testing is not recommended.

If the answer is "yes" for travel history for the male or non-pregnant individual and:

3.B the patient was previously symptomatic consistent with Zika virus infection and the symptoms have now resolved, testing is not recommended.

If the answer is "yes" for travel history for the male or non-pregnant individual and:

3.C if the patient has had no symptoms consistent with a Zika virus infection, testing is not routinely recommended.

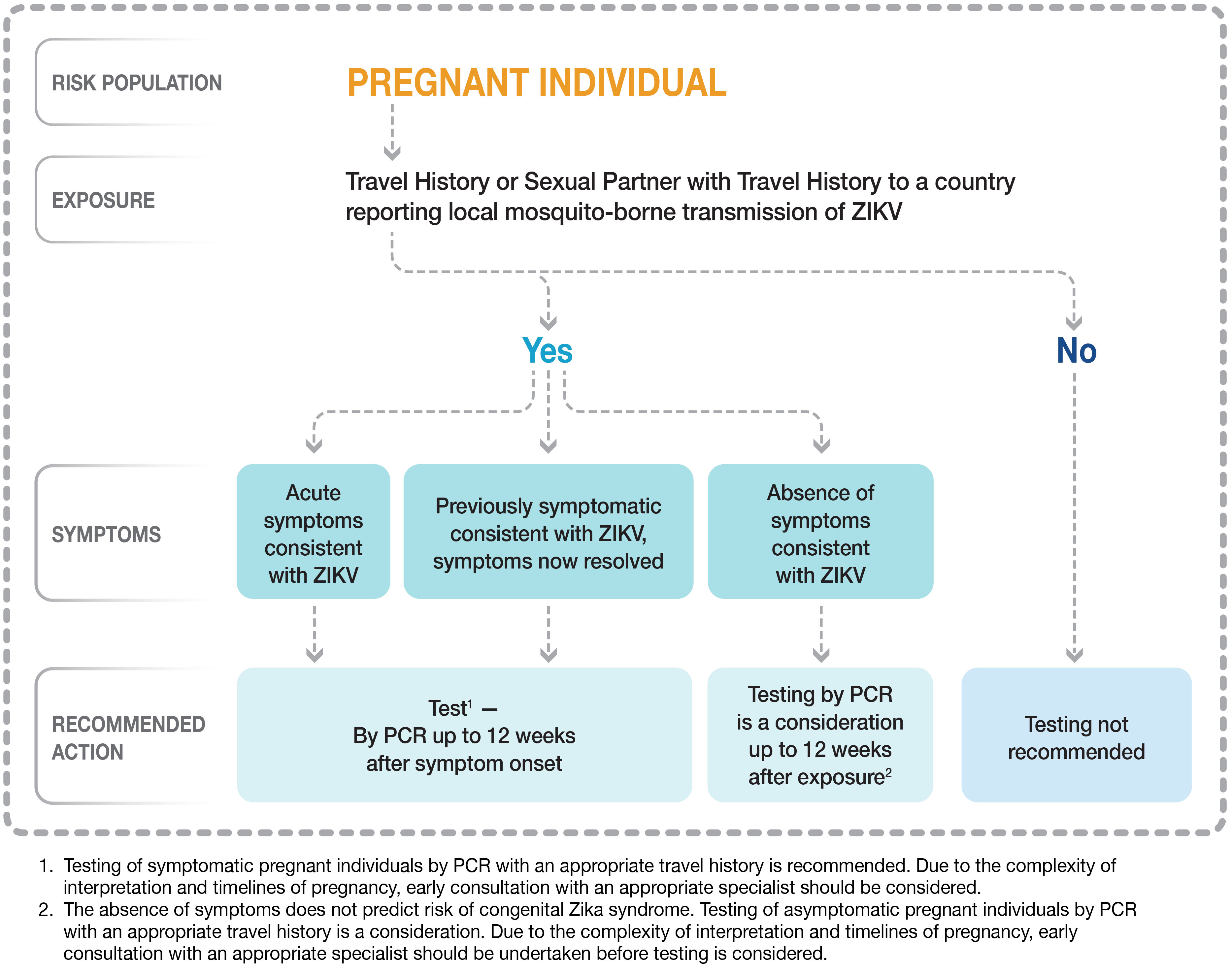

Decision-tree for Zika virus laboratory testing

Figure 2 - Text description

Individual who is pregnant

If the individual is pregnant

1. Do they have a travel history or a sexual partner with travel history to a place reporting local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus infection?

If the answer is "no", then testing for Zika virus infection is not recommended. Zika virus infection is unlikely without travel or exposure history.

2. If the answer is "yes" for travel history or a sexual partner with travel history to a place reporting local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus infection for the pregnant individual, choose from 3 options:

- "The patient is experiencing acute symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection."

- "The patient was previously symptomatic consistent with Zika virus infection and the symptoms have now resolved."

- "The patient has had no symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection."

If the patient is a pregnant individual and the answer is "yes" for travel history or a sexual partner with a travel history to a place reporting local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus infection and:

2.A the patient is experiencing acute symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection, PCR testing is recommended up to 12 weeks after symptom onset but serological testing is not recommended.

If the patient is a pregnant individual and the answer is "yes" for travel history or sexual partner with travel history to a place reporting local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus infection and:

2.B if the patient was previously symptomatic consistent with Zika virus infection and the symptoms have now resolved, PCR testing is recommended up to 12 weeks after symptom onset but serological testing is not recommended.

If the patient is a pregnant individual and the answer is "yes" for travel history or sexual partner with travel history to a place reporting local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus infection and:

2.C if the patient has had no symptoms consistent with a Zika virus infection, PCR testing is a consideration up to 12 weeks after the potential exposure but serological testing is not recommended.

The absence of symptoms does not predict risk of congenital Zika syndrome. Due to the complexity of interpretation and timelines of pregnancy, you should consult early with an infectious diseases specialist before testing is considered.

Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis is usually accomplished by testing serum or plasma to detect any of the following:

- viral genetic material (ribonucleic acid, RNA)

- virus-specific antibodies produced by the body

There are 2 testing methods available for detecting Zika virus infections: polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and serology testing. Serological testing is not recommended for Zika virus.

Polymerase chain reaction testing

This test directly detects the genetic material of Zika virus. A positive result confirms the patient has a Zika virus infection.

The PCR assay is most effective when testing clinical specimens such as:

- blood collected within 10 days of symptom onset

- urine collected within 14 days of symptom onset

The major limitation of this test is that Zika virus may only be present in these types of specimens for a short time after the start of an infection/symptom onset.

A positive PCR test for Zika virus signifies an acute infection.

A negative PCR test for Zika virus may mean:

- there was no infection

- the individual was infected but the virus was no longer present when the sample was collected

Serology testing

Prior to May 2023, serology testing was recommended for individuals meeting testing criteria but outside of the acute phase of the disease. Based on data that has accumulated since Zika virus became more widespread, it has become apparent that IgM can persist for prolonged periods of time and that cross reactivity with other viruses makes interpretation difficult. As a result, the updated recommendations no longer recommend serology.

Instead of testing for components of the virus, these tests are able to detect the presence of Zika virus antibodies. Antibodies become detectable approximately one week post symptom onset.

The major limitations of serology are that it:

- may take several days or weeks to perform and report back results

- is prone to cross-react with antibodies that target other similar flaviviruses related to Zika virus, including the dengue virus

Due to cross-reactivity with dengue virus and the potential for persistence of IgM antibodies, serological testing is not recommended for Zika virus.

An initial positive serological result may represent:

- an acute infection or previous exposure to Zika virus

- an acute infection or previous exposure to another flavivirus

- past vaccination for other viruses, such as yellow fever

Identifying and confirming Zika virus-specific antibodies in serum samples requires further testing and, in some cases, collecting additional samples. This is due to possible cross-reactivity of serologic tests with antibodies that relate to other similar flaviviruses such as dengue virus.

A negative serological test for Zika could mean:

- antibodies have yet to develop

- there was no infection, which may warrant the collection of additional samples

A negative serology test performed 1 to 2 months following return from travel would indicate that there was no infection, because antibodies usually develop within 4 weeks following exposure.

Treatment

Currently, there is no prophylaxis, vaccine or treatment for Zika virus infection. Treatment may be directed toward symptom relief, such as:

- rest

- fluids

- analgesics

- avoid acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs until dengue infection has been eliminated as a possibility

- antipyretics

Surveillance in Canada

Since the emergence of Zika virus in the America’s in 2015, the Public Health Agency of Canada has been conducting surveillance in order to inform public health actions. The outbreaks that occurred in 2016 have subsided and the incidence of Zika in Canada has dropped significantly. The Public Health Agency of Canada is now focusing on monitoring for indicators that the risk of Canadians acquiring Zika has changed (e.g., due to new outbreak activity or new research findings) and therefore is no longer updating Canadian case counts. Health professionals in Canada play a critical role in identifying cases of Zika virus infection. Health professionals who have questions should contact their local public health authorities for further details.

The National Microbiology Laboratory performs diagnostic testing to detect the virus and the presence of viral antibodies and offers testing support to provinces and territories. Some provincial laboratories also offer testing.

Zika virus cases in Canada

As of August 31, 2018, 569 travel-related cases and 4 sexually transmitted cases had been reported in Canada since cases started being detected in October 2015. Sexually transmitted cases are cases with no history of travel to an affected region within the two weeks prior to symptom onset. A total of 45 cases were reported amongst pregnant women in Canada and less than 5 cases of congenital Zika syndrome were reported during this time frame. Reporting peaked during the 2016 outbreak; a total of 19 cases were reported in 2015, 468 in 2016, 74 in 2017 and 14 in 2018 as of August 31, 2018.

Since pregnancy outcomes (including births, stillbirths, pregnancy loss and terminations) are not reported to public health authorities, pregnancy outcomes for Zika-infected individuals are not generally known. Surveillance activities have been focused on detecting the number of cases of congenital Zika syndrome (those with observable Zika-related anomalies).

There is ongoing low risk to Canadians travelling to countries or areas with reported mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus. However, there has been a decline in cases observed in most of the Caribbean and Central and South American countries in 2017 and 2018 and subsequently in Canadian case counts.

How Canada monitors Zika

The National Microbiology Laboratory is able to detect the virus and offers testing support to provinces and territories. Some provincial labs also conduct testing.

As part of their West Nile virus surveillance programs, several provinces and territories conduct mosquito surveillance activities.

Zika virus around the world

The virus was first identified in humans in the 1950s. From 1951 through 1981, evidence of human Zika virus infection was reported from African countries and in parts of Asia.

In 2007, the first major outbreak of Zika virus occurred in Micronesia (Yap Island) in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. This was the first time that Zika virus was detected outside of Africa and Asia.

Between 2013 and 2015, several significant outbreaks were noted on islands and archipelagos from the Pacific region. This included a large outbreak in French Polynesia.

In early 2015, Zika virus emerged in South America with widespread outbreaks reported in Brazil and Colombia. Outbreak activity associated with emergence of this disease in the Americas peaked in the Caribbean, Central and South America in 2016.

The World Health Organization monitors Zika case reports from around the world. To date, a number of countries, territories and areas have reported cases of congenital Zika syndrome and/or central nervous system malformations associated with Zika virus infection. Monitoring of pregnant women in other countries experiencing Zika virus outbreaks is ongoing.

Related information

- Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel

- Pan American Health Organization: Zika virus infection

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Zika virus

Tip sheets for print

- Zika virus: Counselling travellers (tip sheet)

- Zika virus: Information for health professionals (tip sheet)

Posters to share

- Advice for Canadians travelling to Zika–affected countries and areas (poster)

- Zika virus: Pregnant or planning a pregnancy and travel (handout)

- Mosquito bite prevention for travellers (poster)

- What males need to know about Zika virus (factsheet)

- Zika virus and sex (factsheet)