Recommendations on screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae for non-pregnant adults/adolescents

Preamble

The National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (NAC-STBBI) is an External Advisory Body that provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with ongoing scientific and public health advice and recommendations for the development of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) guidance, in support of its mandate to prevent and control infectious diseases in Canada.

PHAC acknowledges that the advice and recommendations in this statement are based upon the best available scientific knowledge/evidence at the time of writing and is disseminating this document for information purposes to primary care providers and public health professionals. The NAC-STBBI Statement may also assist policy-makers or serve as the basis for adaptation by other guideline developers. The NAC-STBBI members and liaison members conduct themselves within the context of PHAC's Policy on Conflict of Interest, including the yearly declaration of interests and affiliations.

The recommendations in this statement do not supersede any provincial/territorial legislative, regulatory, policy and practice requirements or professional guidelines that govern the practice of health professionals in their respective jurisdictions, whose recommendations may differ due to local epidemiology or context. The recommendations in this statement may not reflect all the situations arising in professional practice and are not intended as a substitute for clinical judgment in consideration of individual circumstances and available resources.

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Background/Introduction

- 2.0 Methods

- 3.0 Recommendations

- 3.1 Recommendation 1: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for non-pregnant adults and adolescents

- 3.2 Recommendation 2: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for adults and adolescents with multiple partners or a new partner

- 3.3 Recommendation 3: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for high prevalence groups and communities

- 3.4 Summary of the evidence

- 4.0 Dissemination, implementation, monitoring and evaluation

- 5.0 Research priorities/Research implications

- List of abbreviations

- Acknowledgement

- Appendices

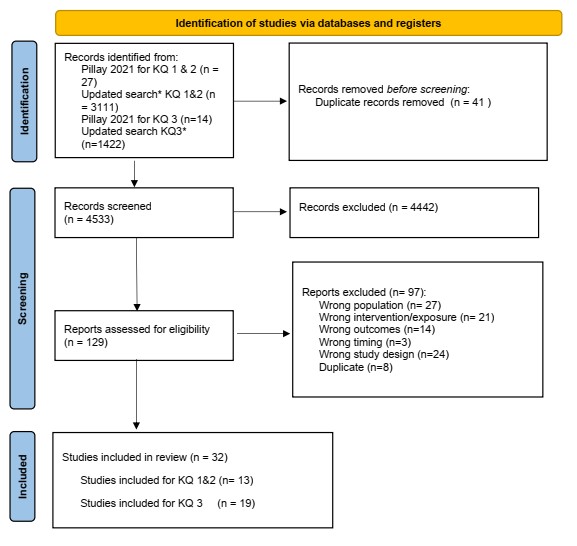

- Appendix 1: Flow diagram of study selection on CT/NG screening since 2019

- Appendix 2: Summary of evidence-to-decision framework judgments

- Appendix 3: Characteristics of included studies on CT/NG screening and summary of findings

- Table 3.1: Key Question 1 - Effectiveness of CT/NG screening vs. no screening among non-pregnant adults

- Table 3.2: Key Question 2 - Comparative effectiveness of a screening intervention compared to another screening intervention for CT/NG

- Table 3.3: Key Question 3 - Relative importance that people place on the potential outcomes from screening for CT/NG

- Table 3.4: Cost Effectiveness of screening interventions and health utility studies

- Table 3.5: Evidence profile

- References

Executive summary

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections are two of the most frequently reported bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STI) in Canada, with rates increasing steadily over the last decade. In 2021, CT infections had an estimated rate of 273.2 cases per 100,000 population, which was highest among females 15 to 29 years old, and males 20 to 29 years old. NG infections had a reported rate of 84.2 cases per 100,000 population, of which rates were highest among females 15 to 29 years old and males 20 to 39 years old. Given the high rates of asymptomatic infection, the increasing rates of CT and NG infections are more difficult to control. When not treated, CT and NG infections can lead to serious complications beyond the impact of the infection itself.

Rationale for the guidelines

In 2021, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) updated their CT/NG screening recommendations for adults and adolescents. This, along with the sustained high CT and NG infection rates, provided an opportunity for the NAC-STBBI and PHAC to review and adopt, or adapt as appropriate, the new CTFPHC recommendation.

Objectives

The objectives of this work are:

- to assess new evidence for CT and NG screening in non-pregnant, sexually active individuals

- to update, as required, the existing CT and NG screening recommendations while considering the following recommendations from the CTFPHC:

- increasing the screening age from <25 years to <30 years, regardless of the presence of risk factors for infection other than age;

- using an opportunistic approach to screening

Methods

A working group comprised of NAC-STBBI members was formed to undertake this work. The guideline was developed following the methods outlined in the 2014 WHO handbook for STI experts, clinicians, researchers, and program managers. The GRADE-ADOLOPMENT method was applied in addition to the GRADE (the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) methodology to determine the certainty of evidence and strength of the recommendations. Using the ECRI TRUST (Transparency and Rigor Using Standards of Trustworthiness) as an indicator of trustworthiness, the CTFPHC guideline obtained a score of "5" on all assessed domains, indicating the highest adherence to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) Standards for Trustworthy Guidelines. Following a review of the key questions from the original CTFPHC systematic review, the key questions were approved with some modifications to the PICO (population, interventions, comparator, outcomes) elements, and consequently, the eligibility criteria for our guideline question "should any screening vs. no screening/ usual care/ any other screening be used for non-pregnant people?" was amended. The population eligibility criterion was expanded to include sexually active individuals less than 30 years and opportunistic screening was added as an intervention of interest. The updated search was conducted with the date range of October 1, 2019, to May 19, 2023, using the same search criteria as the CTFPHC systematic review. The studies included in the original systematic review were also screened against the new eligibility criteria. Furthermore, an environmental scan was performed and found 17 guidelines on CT and NG screening published between 2015 and 2023; of those, 9 were international and 8 were Canadian. The Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the identified guidelines. As well, PROGRESS-Plus (Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status and Social capital - personal characteristics associated with discrimination features of relationships and time-dependent relationships) equity factors were identified in the guidelines to assess the range of social determinants and factors that contribute to health equity.

Conflicts of interest were managed according to PHAC guidelines. At the beginning of each NAC-STBBI WG meeting, the members disclosed their interests, if any. After analysing each declaration of interest, it was concluded that no conflicts were identified by the working group and NAC-STBBI members that would prevent them from participating in the discussion and voting on the committee's recommendations.

Summary recommendations

This statement provides three screening recommendations for non-pregnant adults and adolescents. Screening is a process aimed at detecting a condition in an asymptomatic person. CT and NG screening recommendations are aimed at non-pregnant adults and adolescents, for adults and adolescents with multiple partners or a new partner, and for high prevalence groups and communities. Table 1 shows the summarized recommendations.

Table 1: Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for sexually active, non-pregnant adults and adolescents

The NAC-STBBI suggests universal annual screeningTable 1 Footnote a for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in all sexually active persons under the age of 30 years

(conditional recommendation; very low-certainty evidence).

Recommendation 2: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for sexually active adults and adolescents with new or multiple partners

The NAC-STBBI suggests screeningTable 1 Footnote a every three (3) to six (6) months for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in all persons with multiple sexual partners or a new partner since last tested.

(conditional recommendation; very low-certainty evidence).

Recommendation 3: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for high prevalence groups and communities

The NAC-STBBI suggests that "opt-out" screeningTable 1 Footnote a for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections be considered as frequently as every three (3) monthsTable 1 Footnote b in populations or communitiesTable 1 Footnote c experiencing high prevalence of CT and NG infections (and other STBBI), such as:

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men;

- People living with HIV;

- People who are or have been incarcerated;

- People who use substances or access addiction services;

- Some Indigenous communities

(conditional recommendation; very low-certainty evidence)

1.0 Background/Introduction

This statement focuses on CT and NG screening for asymptomatic sexually active non-pregnant adults and adolescents. In 2021, the CTFPHC updated their CT and NG screening recommendations for adults and adolescents. This provided an opportunity to the NAC-STBBI and PHAC to review and adopt, or adapt as appropriate, the new CTFPHC recommendation.

1.1 Public Health importance

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) are an important sexual and reproductive health problem globally. In 2021, CT and NG infections were the two most frequently reported bacterial STI in Canada. Over the past decade, reported rates of CT and NG infections have increased steadily. Between 2011 and 2019, rates of CT infections increased by 26% and rates of NG infections by 171% Footnote 1. An exception to this trend was seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected the demand for and access to services related to sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections across the country, including testing Footnote 2. In 2021, CT infections had an estimated rate of 273.2 cases per 100,000 population, which was highest among females 15 to 29 years old, and males 20 to 29 years old. NG infections had a reported rate of 84.2 cases per 100,000 population of which rates were highest among females 15 to 29 years old and males 20 to 39 years old. The increasing rates of CT and NG infections are more difficult to control because many individuals who are infected are asymptomatic. When CT and NG infections are not treated, they can lead to serious complications beyond the impact of the infection itself, such as chronic pelvic pain, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, ectopic pregnancy, epididymo-orchitis and reactive arthritis Footnote 3.

1.2 Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections

The goals of CT and NG screening among sexually active young adults are to detect and treat asymptomatic infections and reduce transmission Footnote 4. However, despite considerable prevention and screening interventions, rates of CT and NG infections continue to rise due to low testing rates Footnote 4, the lack of health-care access for marginalized Canadians and changing sexual behaviours Footnote 2Footnote 5. Evidence-based interventions to screen and treat CT and NG infections are needed to contain the STI epidemic and decrease the associated complications and the ensuing health care costs Footnote 6Footnote 7.

Many countries are assessing their CT and NG screening programs to ensure the design, implementation and evaluation are based on the best available evidence. As an example, the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) in the United Kingdom reported that they are changing the focus of their program on preventing adverse outcomes of untreated CT infection in females rather than trying to reduce prevalence Footnote 8. They have not found any clear evidence that widespread screening tests reduce CT transmission, prevalence and its associated complications. Australia, on the other hand, recommends screening based on epidemiology and high rates of infection Footnote 9. They recommend universal screening of males and females between the ages of 15 and 29 years for CT and NG as these infections are the most notified infectious disease among this age range. When revising a screening program, the possibility of spontaneous clearance of CT and NG infections should also be taken into consideration. The possibility for infections to clear spontaneously could indicate that some asymptomatic infections may not require treatment and that treatment of all infections after a one-time NAAT may be unnecessary Footnote 10Footnote 11.

Screening programs should only be implemented if the benefits exceed the harms, and resource use is justifiable Footnote 12. Benefits of screening include helping to stop the spread of infection Footnote 13, the prevention of serious complications such as PID and epididymitis Footnote 14Footnote 15 and maintaining a good sexual and reproductive health Footnote 16. One study showed that adolescents and young adults would accept screening despite their concerns of stigmatization and anxiety Footnote 17.

A critical component of an STI control program is screening Footnote 18. The main rationale for CT and NG screening is to detect asymptomatic infections in women before they cause PID or other reproductive complications Footnote 19. There are several types of approaches to screening, such as universal, opportunistic, targeted and systematic. The CTFPHC recommends opportunistic screening of sexually active individuals younger than 30 years who are not known to belong to a high-risk group, annually, for CT and NG infections at primary care visits, using a self or clinician-collected sample Footnote 12. Grennan et al. endorses CTFPHC's new screening guideline and adds that the benefits will not only increase the number of cases diagnosed, but it will decrease transmission, and possibly reduce the likelihood of being a risk factor for HIV acquisition Footnote 18Footnote 20.

1.3 Purpose/Rationale

At the October 2019 face-to-face meeting, the NAC-STBBI identified the review of CT and NG screening guidelines as one of a number of priority topics. Work was anticipated to begin following the completion of projects already in progress; however, plans were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and several projects were forced to be put on hold, delaying the start of this work. In 2021, the CTFPHC updated their chlamydia and gonorrhea screening recommendations Footnote 12 for adults and adolescents. This provided an opportunity to the NAC-STBBI and PHAC to review and adopt, or adapt, the new CTFPHC recommendation.

The updated CTFPHC screening recommendations differed from the 2010 CT and NG screening recommendations in two key areas. Firstly, the CTFPHC recommends increasing the screening age for CT and NG infections in sexually active individuals, from <25 years to <30 years, regardless of the presence of risk factors for infection other than age Footnote 12. PHAC previously recommended that all sexually active individuals <25 years of age be screened for CT and NG infections and that sexually active individuals ≥25 years and older be screened in the presence of risk factors for infection Footnote 21. Secondly, the CTFPHC recommends opportunistic screening. The guideline explains that in Canada, "STI screening is most commonly offered opportunistically by clinicians in a variety of primary care settings (e.g., family practice, sexual health clinics, school health centres) during visits that may or may not be for sexual health-related concerns" Footnote 12. In order to determine whether to adopt the CTFPHC recommendation, the NAC-STBBI Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Screening Working Group (WG) needed to undertake a review of the evidence that informed these new aspects to their recommendation based on the guideline question, "should any screening vs. no screening/ usual care/ any other screening be used for non-pregnant people? "

As part of this review, the NAC-STBBI WG decided to update CTFPHC's systematic review (SR) "Screening for CT or NG in primary health care on effectiveness and patient preferences" Footnote 22 to inform the NAC-STBBI guideline on screening for CT and NG infections in sexually active populations with no known risk factors for infection other than age.

1.4 Objectives

The objectives of these guidelines are:

- to assess new evidence for CT and NG screening in non-pregnant, sexually active individuals

- to update, as required, the existing CT and NG screening recommendations while considering the following recommendations from the CTFPHC:

- increasing the screening age from <25 years to <30 years, regardless of the presence of risk factors for infection other than age;

- using an opportunistic approach to screening.

1.5 Target audience

This document is intended to be used by primary care providers (i.e., nurses, physicians), provincial/territorial sexual health programs, local public health agencies, sexual health clinics, professionals' associations, and researchers.

2.0 Methods

The CT and NG screening recommendations were developed following the methods outlined in the 2014 edition Footnote 23 of the WHO handbook for guideline development. The evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Footnote 24 approach to determine the certainty of evidence and strength of the recommendations. The GRADE-ADOLOPMENT method Footnote 25 was applied to the project's update of the CTFPHC systematic review in addition to the GRADE methodology used for the original CTFPHC systematic review. "Adolopment" combines adaptation and development, emphasizing that it's not just about using existing guidelines but also tailoring them to local needs.

2.1 Working group

The NAC-STBBI established a working group (WG) for guideline development comprising three members of the NAC-STBBI and supported by a research team from the PHAC STBBI Guidance for Health Professionals Section (PHAC team). The NAC-STBBI WG consisted of STI experts, clinicians, researchers, and programme managers (see Acknowledgements for member lists). At the onset of this project, the NAC-STBBI WG identified and agreed on the key PICO (population, interventions, comparator, outcomes) questions that formed the basis for the SR and the recommendations. Following this meeting, the NAC-STBBI WG members prioritized outcomes according to clinical relevance and importance. The NAC-STBBI WG participated in meetings and teleconferences to prioritize the questions to be addressed, discussed the evidence reviews and finalized the recommendations. The first draft recommendation was presented to the NAC-STBBI advisory group committee meeting for discussion. Final recommendations were prepared incorporating suggestions provided at the NAC-STBBI meeting. The final recommendations and documents were sent to members before the committee meeting. Voting was convened and consensus was received at the NAC-STBBI teleconference on September 26, 2024.

The NAC-STBBI WG independently conducted a SR update of available studies, including primary studies and systematic reviews on CT and NG screening, and scanned previously published screening guidelines using Google, the websites of international organizations, provincial/territorial organizations, and the systematic review in 2021 by CTFPHC Footnote 12. The PHAC team included studies on CT and NG screening, patient values and preferences, equity, feasibility, acceptability, cost and cost-effectiveness analyses and used the GRADE and GRADE Adolopment for assessing the certainty of evidence and updating the evidence of CTFPHC systematic review/guidelines Footnote 24Footnote 25. Using the ECRI TRUST Footnote 26 (Transparency and Rigor Using Standards of Trustworthiness) as an indicator of trustworthiness, the CTFPHC guideline obtained a score of "5" on all assessed domains. This means that it has the highest adherence to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) Standards for Trustworthy Guidelines Footnote 26. Following a review of the key questions from the original CTFPHC systematic review, the key questions were approved with some modifications to the PICO elements, and consequently, the eligibility criteria. The population eligibility criteria was expanded to include sexually active individuals less than 30 years and opportunistic screening was added as an intervention of interest. The updated search was conducted with the date range of October 1, 2019, to May 19, 2023, using the same search criteria as the CTFPHC systematic review. The studies included in the original systematic review Footnote 22 were also screened against the new eligibility criteria. Furthermore, an environmental scan was executed and found 17 health authorities with a total of 20 guidelines on CT and NG screening published between 2015 and 2023; of those 9 were international Footnote 9Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36 and 8 were Canadian Footnote 12Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44. The Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument Footnote 45 was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the identified guidelines. As well, PROGRESS-Plus equity factors were identified in the guidelines to assess the range of social determinants and factors that contribute to health equity Footnote 46. Research implications were also developed by the NAC-STBBI WG to describe practical applications of the findings. This statement has been approved by PHAC Executive. The approved statement will also be submitted as a manuscript to a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

2.2 Questions and outcomes

In November 2021 the NAC-STBBI WG approved the following research questions/key questions (KQ):

- KQ1: What is the effectiveness of screening compared with no screening for CT or NG infections in non-pregnant sexually active individuals (as of October 2019)?

- KQ2: What is the comparative effectiveness of different screening approaches for CT or NG infections in non-pregnant sexually active individuals (as of October 2019)?

- KQ3: What is the relative importance that people place on the potential outcomes from screening for CT or NG infections (as of October 2019)?

The NAC-STBBI WG identified the key PICO questions that formed the basis for the SR and the recommendations as follows:

- Population: non-pregnant, sexually active individuals ≥12 years old with no known risk factors (aside from age) for CT or NG infections

- Interventions: For KQ 1 and KQ 2, the intervention of interest was screening intervention(s) compared to no screening intervention, or one or more types of screening intervention(s) compared to different screening intervention(s). The exposure of interest for KQ 3 was experience with any screening program for CT or NG infections; experience with infections or outcomes of interest; and exposure to scenarios about the screening process and possible outcomes of screening.

- Comparator: The comparator for KQ 1 was no screening intervention or usual care and the comparator for KQ 2 was a different screening intervention(s). All outcomes for KQ 3 were only in relation to the primary outcomes for KQs 1 and 2. We focused on utilities/health state valuations or other utility data; non-utility, quantitative information on the relative importance of benefits and harms; and qualitative information indicating relative importance between benefits and harms.

- Outcomes: KQ 1 and KQ 2 outcomes included CT/NG infection transmission; cervicitis; pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); ectopic pregnancy; chronic pelvic pain (≥6 months duration); infertility: inability to conceive with unprotected sex for 12 months or longer; negative psychosocial impact from a screening procedure or based on results of a positive diagnostic screening test or presumptive diagnosis; and individual and population level adverse events from antibiotics. Outcomes for KQ 3 focused on utilities/health state valuations or other utility data; non-utility, quantitative information on the relative importance of benefits and harms; and qualitative information indicating relative importance between benefits and harms.

- Study designs: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and non-randomized experimental studies were included. Uncontrolled observational studies or descriptive (e.g., qualitative, surveys) studies, where participants had experience of screening, were included for evidence on the harm of negative psychosocial impact due to no or very low-quality evidence from the other design categories on this outcome.

2.3 Review of the evidence

A hierarchical approach was used to search for evidence to update the CTFPHC SR Footnote 22. The updated search was performed by a librarian using the same search terms as the CTFPHC search and executed from October 1, 2019 – May 19, 2023. Studies published in English and French were included. It was not possible to search the same databases as the CTFPHC due to a lack of access to the Conference Proceedings Citation Index–Science edition, CINHAL or the Wiley Cochrane Library. However, the Cochrane search was able to be updated via Cochrane CENTRAL on the Ovid platform. The PHAC team also searched for SR, then primary studies when no SR was available. The grey literature search included searching sources identified in the CTFPHC SR, as well as additional sources identified by the NAC-STBBI WG and Secretariat. Sources searched included trial registries, conference abstracts, reports and CT/NG screening guidelines from international, provincial and territorial public health organization websites. Eleven studies were identified for full-text screening in the grey literature search. Reference lists of all included studies and relevant SR that were identified in the updated search were searched by hand for any missed studies. None were identified. Two members of the PHAC Team screened studies, extracted and analyzed the data, and assessed the quality/certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach Footnote 24. Refer to Appendix 1 for the flow diagram of study selection.

The certainty of the evidence was assessed at four levels: Footnote 24Footnote 47

- High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

- Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

- Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

- Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Details of evidence from different sources/types and evidence to decision (EtD) judgments are available in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3. In addition to the 41 records identified from Pillay 2021 Footnote 22, 4533 records were located from databases. Following the title and abstract screening phase, 4442 records were excluded, and 41 duplicate records were removed, and 129 records were sought for retrieval. All records were assessed for eligibility and 97 records were excluded (Appendix 1). A total of 32 records were included in the review, including original articles on screening types, patient values, preferences and feasibility and the impact on health equity of CT and NG screening. The excluded studies contained the incorrect population, intervention/exposure, outcome, study timing and study design. Five systematic reviews were identified and included Footnote 4Footnote 48Footnote 49Footnote 50Footnote 51.

2.4 Making recommendations

Between June to September 2024, the NAC-STBBI WG developed the recommendations in seven meetings. The three members were present and reviewed the evidence to decision table presented by the PHAC team. They also reviewed the available national, provincial (Alberta, Québec) epidemiological data Footnote 52Footnote 53 and additional references from their experiences and practice. During the formulation of the recommendations, the NAC-STBBI WG considered and discussed both the desirable and undesirable outcomes of screening interventions, the values and preferences, feasibility, equity, resources, cost and cost effectiveness of the interventions. They also discussed the implementation of the recommendations and research gaps. The discussion was facilitated by a methodologist with the goal of reaching consensus across the NAC-STBBI WG.

The draft recommendations, the evidence and the working group's rationale for the recommendations were presented to the NAC-STBBI on June 27, 2024. With the committee's input, final recommendations were compiled by the NAC-STBBI WG and sent to the NAC-STBBI on September 5, 2024, for their review. Consensus was obtained to approve the recommendations at a NAC-STBBI committee meeting on September 26, 2024. PHAC approval was provided by the Vice-President of the Infectious Diseases and Vaccination Programs Branch on October 24, 2024. The recommendations were subsequently added to PHAC's Chlamydia and LGV (lymphogranuloma venereum) guide and Gonorrhea guide, within the STBBI Guides for Health Professionals.

According to the GRADE approach, the certainty of evidence was rated as very low certainty, and the strength of the recommendations was rated as conditional. The conditional recommendations are worded as "the NAC-STBBI guideline suggests....". The implications of conditional recommendations are:

- For patients: "The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences.".

- For clinicians: "Different choices will be appropriate for individual patients; clinicians must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with his or her values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping individuals to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences."

- For policy-makers: "Policymaking will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures should assess if decision-making is appropriate."

- For researchers: "The recommendation is likely to be strengthened (for future updates or adaptation) by additional research. An evaluation of the conditions and criteria (and the related judgments, research evidence, and additional considerations) that determined the conditional (rather than strong) recommendation will help identify possible research gaps."

2.5 Management of conflicts of interest

Members of the NAC-STBBI are required to identify affiliations and conflicts of interest on an annual basis. The Secretariat reviews member affiliations to ensure there are no conflicts of interest. Committee members are also asked to identify any new affiliations at the start of every meeting and teleconference. No conflicts were identified by the working group and NAC-STBBI members that would prevent them from participating in the discussion and voting on the committee's recommendation.

3.0 Recommendations

Screening is a process aimed at detecting a condition in an asymptomatic person. Recommendations developed by the NAC-STBBI are made at the population level. It is important to note that they may not apply to specific individuals within those groups, particularly as it relates to groups or communities who may have higher rates of CT and NG when compared to the general public. It is always essential to consider the context of the risk behaviours and epidemiological factors outlined in the recommendation.

3.1 Recommendation 1: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for non-pregnant adults and adolescents

The NAC-STBBI suggests universal annual screening* for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in all sexually active persons under the age of 30 years.

(conditional recommendation; very low certainty evidence).

3.2 Recommendation 2: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for adults and adolescents with multiple partners or a new partner

The NAC-STBBI suggests screening* every three (3) to six (6) months for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in all persons with multiple sexual partners or a new partner since last tested.

(conditional recommendation; very low certainty evidence).

3.3 Recommendation 3: Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae screening for high prevalence groups and communities

The NAC-STBBI suggests that "opt-out" screening* for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections be considered as frequently as every three (3) months** in populations or communities*** experiencing high prevalence of CT and NG infections (and other STBBI), such as:

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men;

- People living with HIV;

- People who are or have been incarcerated;

- People who use substances or access addiction services;

- Some Indigenous communities

(conditional recommendation; very low certainty evidence).

Considerations:

* Options to increase screening uptake should be explored. They include:

- Opportunistic screening (offering screening when an individual accesses health services and has not undergone recent STBBI testing)

- Increasing accessibility and normalizing testing through strategies such as outreach testing and opt-out screening

- Facilitating sample collection through strategies such as non-invasive collection specimens, including self-sampling

**Consider aligning screening with other health services ("opportunistic screening") such as HIV or addiction care.

* ** Consider local epidemiology, travel history and individual patient risk factors when determining which groups/communities to target

Factors associated with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeaeinfections Footnote 54Footnote 55Footnote 56

Behaviours/Activities

- Sexual activity involving contact with oral, genital or anal mucosa Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59

- Multiple sexual partners Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59Footnote 60

- Sexual contact with a person infected by CT or NG ("known case") or other STBBI Footnote 59Footnote 60

- Substance use, including chemsex Footnote 59Footnote 60

Epidemiological/Biological

- Previous CT, NG or other STBBI Footnote 58Footnote 59

- HIV infection Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59Footnote 60

- High prevalence in geographical area Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59Footnote 60

- High prevalence in population groups Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59Footnote 60

- Housing instability/street involvement Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 61Footnote 62

3.4 Summary of the evidence

The certainty of evidence for the screening of CT and NG infections in asymptomatic non-pregnant individuals was very low. The review retrieved 32 articles which included five randomised controlled trials (RCT) Footnote 4Footnote 48Footnote 49Footnote 50Footnote 51, five cohort studies Footnote 63Footnote 64Footnote 65Footnote 66Footnote 67, seven qualitative studies Footnote 17Footnote 68Footnote 69Footnote 70Footnote 71Footnote 72Footnote 73, five cross-sectional studies Footnote 13Footnote 74Footnote 75Footnote 76Footnote 77, four cost-effectiveness studies Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 78Footnote 79, a prospective delayed start pragmatic study Footnote 7, a controlled pre-post quasi-experimental study Footnote 5, a randomized pre-post study Footnote 80, a retrospective service evaluation Footnote 16, a mixed-method study Footnote 81, and a health utility study Footnote 82. The studies included in the retrieved systematic reviews were assessed for any missing eligible articles that could be included in the evidence review. In addition, the environmental scan retrieved 11 guidelines Footnote 9Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 83 from 9 international organizations and 9 guidelines Footnote 12Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44 from 8 Canadian public health organizations on CT or NG screening. These guidelines varied mostly on the types of screening used (opportunistic, universal, or risk-based screening). Almost all guidelines recommend screening individuals <25 years of age Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 83, while only two organizations recommend screening individuals <30 years of age Footnote 9Footnote 12.

Due to the very low quality of certainty and lack of evidence for CT or NG frequency of screening for adults and adolescents with multiple partners or a new partner, the working group decided to include indirect clinical evidence from the NAC-STBBI syphilis screening guidelines Footnote 84. The syphilis screening guidelines included a systematic review as part of the evidence synthesis Footnote 85 that indicated higher rates of syphilis detection when screening every 3 months versus 6 or 12 months in HIV-positive men or MSM.

Benefits of Screening

The benefits of screening for CT infection were assessed in three RCTs and a controlled cohort study comparing universal screening to usual care. The authors found little evidence that universal screening impacted CT positivity rates Footnote 4, prevalence rates Footnote 48, and incidence of PID Footnote 4Footnote 48Footnote 63Footnote 83. Notably, the results on positivity rates were not consistent. A prospective delayed start pragmatic study and a pre-post quasi-experimental study assessing clinic-based universal screening found that rates of CT infections significantly decreased in primary care (pediatrics clinic and family clinic), and in one of two emergency departments included in the study Footnote 5Footnote 7.

Three studies comparing home-based screening to clinic-based screening on CT infection transmission found that home-based screening where an asymptomatic individual orders a self-sample test kit from a website, collects their sample and sends it to a laboratory for processing; is beneficial to increase access to services. A RCT found that clinic-based opportunistic screening detected slightly higher rates of CT infection than home-based screening Footnote 51. However, a retrospective cohort study and a pre – post study reported that non-invasive self-sampling (urine sample or vaginal swab) resulted in a higher CT detection rate, suggesting that at-home screening is at least as effective as clinic-based screening, while also being an accessible alternative to in-clinic screening Footnote 16Footnote 65. In contrast, two studies found that NG infection rates increased following the implementation of clinic-based universal screening in the family clinic, while decreasing in the pediatric clinic and one of two emergency departments Footnote 5Footnote 7.

Harms of Screening

Three studies found little evidence of negative psychosocial impact from screening efforts. A cohort study assessing universal screening to no screening found that irrespective of the test result, women were afraid of the possibility of receiving a positive test Footnote 66. However, women who received a positive test had less concern about their test, their future health and their partner's reaction compared to women who reported on how they thought they would feel if they received a positive test Footnote 66. A randomized pre - post study comparing CT home-based screening to no screening found that the invitation to participate in screening resulted in higher anxiety scores in females compared to males Footnote 80. Screening did not impact overall well-being, as anxiety decreased following the submission of the test among males, while decreasing in females following a negative test result Footnote 80. Similar findings were reported in a randomized controlled trial investigating screening for CT and NG, where males were more likely to complete screening at home, compared to in-clinic, with no difference in positivity rates Footnote 50.

Patients Preference and Values

Patients' preferences and values on CT screening were assessed in seven qualitative studies. These studies assessed no screening or compared universal screening to no screening. In one study, the majority of participants reported that they would get tested for CT and they would encourage others to get tested Footnote 69. The negative emotions that arose from screening were related to embarrassment with sexual health issues, the association that STIs have with sexual promiscuity Footnote 17Footnote 68Footnote 70, perceptions of public stigma Footnote 66Footnote 68Footnote 72, concern for their future reproductive health Footnote 70, anxiety regarding notifying their partners Footnote 70, and anonymity Footnote 17. Despite these potential barriers to testing, participants reported recognizing the need to balance the harms of screening with the benefits Footnote 66Footnote 67.

Qualitative studies assessing perceived barriers to CT and NG screening found that fear and aversion Footnote 75, social stigmas Footnote 72Footnote 75, negative consequences Footnote 72Footnote 75, confidentiality Footnote 72, and the reputation of the clinic represented significant barriers to being tested, which could increase the risk of spreading infection to others Footnote 72Footnote 75.

Cross-sectional data suggests that both positive and negative beliefs influence the decision to seek regular CT testing. Positive beliefs, such as the reassurance of not being infected, increase the intention to seek CT testing; meanwhile, negative beliefs (getting testing is embarrassing) reduce intentions to seek testing Footnote 74. Females were significantly more likely to hold positive beliefs than males Footnote 13.

A RCT feasibility study and a retrospective cohort study comparing home-based to clinic-based CT screening found that a higher percentage of individuals who self-tested at home and returned their samples compared to those who were subject to clinic-based opportunistic screening Footnote 51Footnote 65. An exception to this finding was among females under 20 years old, who returned more samples in the opportunistic group than the postal group Footnote 51. A service evaluation study did not find that online self-sampling for CT increased the number of individuals screened Footnote 16. Similarly, a controlled trial with randomized stepped wedge implementation did not support a registered based CT screening program as the participation rate declined over screening rounds Footnote 4.

A RCT and a retrospective cohort study found that home-based chlamydia screening did not vary in opt-out rate compared to usual-care and opportunistic screening Footnote 51. Findings on self-sampling were mixed where a higher proportion of males used self-sampling compared to usual-care or opportunistic screening Footnote 65; however, females were more likely to take part in self-sampling than males when comparing universal self-sampling to usual care Footnote 4. Furthermore, participation rates were higher among the older age groups Footnote 4. Qualitative findings related to acceptability of CT and NG screening found a very high rate of acceptance, with the idea of offering universal screening to adolescents using a tablet-based CT and NG screening tool in a private room. Adolescents felt it would address concerns about bringing up CT and NG screening with clinicians, while parents or guardians felt that using tablets may increase participation to screening but were concerned about the lack of personal interaction with a health care provider Footnote 73.

4.0 Dissemination, implementation, monitoring and evaluation

4.1 Dissemination

This statement can be accessed in English and in French on Canada.ca. The recommendations contained in this statement have been incorporated within PHAC's Chlamydia Guide and Gonorrhea Guide.

4.2 Implementation

Our current Canadian health care system is overburdened and under-resourced. New strategies and approaches for screening are needed to ensure equitable access to the system. To implement these screening recommendations, clinicians are advised to offer universal annual screening in all sexually active persons under the age of 30 years. For individuals over or equal 30 years of age, a risk assessment should be conducted in all sexually active individuals, since those who are at high risk for CT or NG infection may not always self-identify or be easily identified by clinicians.

CT and NG infections are often associated with social stigma, shame and embarrassment, which could prevent an individual from seeking screening and treatment Footnote 8Footnote 12. Routinizing STI testing has been suggested as a way to help destigmatize STI testing by disassociating it from singling out individuals because of their reported or assumed risk behaviours Footnote 9. Making screening part of routine care helps to reduce stigma and normalize conversations around sexual health.

Individuals with a negative experience with the health care system may be reluctant to seek care. Alternate strategies and approaches may be needed to enhance trust and improve comfort with accessing health services. These strategies may vary across provinces/territories, local communities or population groups. A "one style fits all" strategy is unlikely to be successful.

Options to increase screening uptake should be explored. Opportunistic screening is a type of screening that capitalizes on existing health care interactions and relations by offering screening when an individual accesses health services and has not undergone recent STBBI testing Footnote 86. Outreach testing (testing in a community-based setting, such as a community agency or on the street) and opt-out programs (universally offering testing unless the person declines) are two strategies that have shown to increase accessibility and normalize testing. Opt-out screening has demonstrated greater success in identifying cases compared to opt-in programs (offering testing to those who agree) Footnote 76Footnote 87. Other strategies to facilitate sample collection are the utilization of self-collection kits, non-invasive collection specimens and home-based screening. Increased availability of point of care tests (POCT), self-tests and rapid tests offer new ways to test the public and may improve acceptability and uptake Footnote 12Footnote 19Footnote 88.

Routine LGV genotyping of asymptomatic CT infections is not recommended. Consider LGV genotyping when an asymptomatic rectal chlamydia infection is diagnosed in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM) with risk factors for LGV (recommendation will be updated in the future). This recommendation is made at the national level and challenges with implementation will vary across the country. Health care providers should consult local/provincial public health guidance for specific recommendations based on the epidemiology of their jurisdiction.

Although the optimal screening interval is unknown, the NAC-STBBI recommendations of annual screening for general risk individuals less than 30 years of age, three (3) to six (6) months in all persons with multiple sexual partners or a new partner, and every three (3) months in populations or communities experiencing high prevalence of CT or NG infections may be the most cost-effective.

STI testing requires informed consent. Health care providers must inform individuals of the benefits and risks of taking or refusing an STI test. They must also address privacy and confidentiality in the event that they need to report a positive test result to the local public health office and potential partner notification.

4.3 Monitoring and evaluation

PHAC and NAC-STBBI continue to monitor the changes in the epidemiology of high prevalence populations/behaviours. Likewise, the publication of new evidence is monitored in order to respond to the latest developments. These screening recommendations will be revised if new evidence becomes available in the coming years, or if the epidemiological situation changes to justify subsequent updates to the recommendations.

4.4 Limitations

There was variation in the certainty of evidence and the applicability of studies. Much of the evidence used to inform the development of these recommendations were based on studies conducted in various age ranges. Studies specifically examining CT and NG screening in the less than 25 years versus the less than 30 years were lacking.

The NAC-STBBI WG did not have a patient representative; therefore, patient perspectives were acquired through the evidence. Studies were included if they used proxies (parents) or others (e.g. healthcare providers) to provide an estimate from the patient's perspective.

We restricted inclusion to English and French language studies; however, we did not identify non-English language studies in our searches or unpublished studies that met inclusion criteria.

Methodological limitations of the low-certainty trials included issues with blinding and the authors did not mention any information related to the use of an appropriate analysis method that adjusted for all the critically important confounding domains. Also, the interventions of some studies did not always directly match the research questions and the total number of participants did not always meet the optimum sample size. Meta-analysis was not performed due to a relatively small number of studies and heterogeneity in populations, settings, comparisons, and outcomes.

5.0 Research priorities/Research implications

During the literature search, no studies were identified that compared screening for CT and NG in the less than 25 years of age contrasted with the less than 30 years of age. There was also limited evidence on the comparison of different screening programs, such as opportunistic screening, universal screening, self-sampling and targeted screening and whether the interventions are cost-effective. Screening strategies such as opt-in and opt-out screening have shown to increase uptake in syphilis testing. The applicability of these two strategies should be researched when screening for CT and NG to assess their performance at increasing detection rates. In addition, further research comparing different screening intervals would be informative.

CT and NG infections have increased gradually over the past few years. Ongoing review and monitoring of the most recent Canadian surveillance data is integral to ensure individuals/ populations with high infection prevalence are identified quickly.

Despite implementing a range of interventions to control CT and NG infections, there lacks high certainty evidence that population prevalence can be reduced by screening programmes or opportunistic testing. There is also a lack of high-quality empirical evidence for the benefits of testing for the prevention of PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility and epididymitis. The focus of future research studies should be targeted to the serious outcomes of untreated CT and NG infections.

There are still knowledge gaps in the natural history of CT and NG infections. NG is considered a serious public health threat, since it has been increasingly developing resistance to antimicrobial drugs recommended as treatment Footnote 89. Further research into the potential harms of overdiagnosis of infection that may clear spontaneously and the overuse of antimicrobials, which may contribute to Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is crucial.

Regarding testing for CT and NG, the Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing (NAAT) screening test is extremely sensitive in detecting both viable and non-viable infectious organisms and may result in a positive test of non-viable organisms that have no role in further transmission. Further research is needed into NAAT screening tests that detect viable organisms only, considering that current increased screening and treatment may be leading to increased development of antimicrobial resistance Footnote 89.

STBBI research is mainly focused on specific population groups such as people living with HIV and gbMSM. Studies focused on the general population are lacking and present a significant gap in evidence. Attempting to generalize evidence from these groups to apply to the general population is not always practical, given significant differences in population groups. Traditionally, gbMSM populations have experienced higher rates of STBBI infections, resulting in a higher frequency of STBBI screening among this population.

Addressing the research gaps listed above would be beneficial to inform whether to update or reaffirm the CT and NG screening recommendations in the future.

List of abbreviations

- AGREE II

- Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II

- AMR

- Antimicrobial Resistance

- CT

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- CTFPHC

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care

- EtD

- Evidence to decision

- gbMSM

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men

- GRADE

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- ICER

- Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- KQ

- Key Question

- NAC-STBBI

- National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections

- NAAT

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing

- NG

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PROGRESS-Plus

- Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status and Social capital - personal characteristics associated with discrimination features of relationships and time-dependent relationships

- QALY

- Quality adjusted life years

- RCT

- Randomized control trial

- SR

- Systematic review

- STBBI

- Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

- STI

- Sexually transmitted infections

- WG

- Working group

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Acknowledgement

Contributors to PHAC Chlamydia and Gonorrhea screening guidelines for non-pregnant adults/adolescents:

- NAC-STBBI Chlamydia and Gonorrhea screening working group:

- J Gratrix, P Smycek, A-C Labbé

- NAC-STBBI members:

- I Gemmill (chair), T Grennan (vice-chair), J Bullard, W Fisher, J Gratrix, T Hatchette, AC Labbé, T Lau, G Ogilvie, M Steben, P Smyzcek, M. Yudin

- NAC-STBBI Ex-Officio:

- I Martin

- NAC-STBBI Secretariat (PHAC):

- H Begum, D Basque, H Sullivan, M Haavaldsrud and S Gadient

- Health Canada library

- For evidence search

Appendices

Appendix 1: Flow diagram of study selection on CT/NG screening since 2019

Figure 1 - Text description

Figure 1: The figure is a flow diagram outlining the steps for study selection. The diagram begins with the identification phase where 4533 records from databases and 41 records from Pillay's systematic review 2021 (20) were identified and 41 duplicate records were removed. It is followed by the screening phase where 4533 records were screened, 4442 records were excluded, 129 records were sought for retrieval. All records were assessed for eligibility, and 97 records were excluded. The diagram concludes with the included phase where 32 records were included in the review including original articles on screening approaches, patient values, preferences and feasibility and the impact on health equity of chlamydia and gonorrhea screening.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Appendix 2: Summary of evidence-to-decision framework judgments

| Factor | Judgement |

|---|---|

Problem |

The problem is a priority |

Desirable effects |

Desirable anticipated effects are moderate |

Undesirable effects |

Undesirable anticipated effects are small |

Certainty of evidence |

Certainty of evidence is considered very low |

Values |

Possibly important uncertainty or variability |

Balance of effects |

Favours the intervention |

Resources required |

Don't know |

Certainty of evidence of required resources |

Very low |

Cost effectiveness |

Probably favours the intervention |

Equity |

Equity impact is probably increased |

Acceptability |

The acceptability is probably yes |

Feasibility |

The feasibility is probably yes |

Type of recommendation |

Conditional recommendation for the intervention |

Appendix 3: Characteristics of included studies on CT/NG screening and summary of findings.

Table 3.1: Key Question 1 - Effectiveness of CT/NG screening vs. no screening among non-pregnant adults

Author, year |

Design; Intensity; Sample Size | Screening rate; Baseline CT/NG | Sex and Age | Setting of intervention; Screening approach | Outcome assessed; ROB | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | ||||||

Hocking et al., 2018 Footnote 48 Australia CT |

Cluster-randomized controlled trial; 3 annual screens offered, 10-15 month follow-up; IG: 3107 |

24% ≥ 1 times over 3 years; 10% |

M and F 16-29 years |

IG: Primary care clinic IG: Opportunistic screening |

Incidence of PID Prevalence in each cluster measured by positive CT test. Uptake of CT testing and re-testing rates; Unclear (performance and attrition bias) |

The prevalence of CT decreased similarly in the control and intervention group. These findings, in conjunction with evidence about the feasibility of sustained uptake of opportunistic testing in primary care, indicate that sizeable reductions in chlamydia prevalence might not be achievable. |

Oakeshott, 2010 Footnote 49 England CT |

Randomized control trial One screen (IG), one deferred screening (CG), 1 year follow-up IG: 1259 |

IG: 100% IG: 5.4% |

Female only 16-27 years |

IG: Outreach sites. Self vaginal swab. IG: Universal screening |

Incidence of PID; Low |

Although some evidence suggests that screening for chlamydia reduces rates of pelvic inflammatory disease, especially in females with chlamydia infection at baseline, the effectiveness of a single chlamydia test in preventing pelvic inflammatory disease over 12 months may have been overestimated. |

van den Broek, 2012 Footnote 4 Netherland CT |

Control trial with randomized stepped wedge implementation 1 yearly screen over 3 years; 317304 |

16% (first round) First invitation: 4.3% |

M & F 16-29 years |

IG: Home-based screening IG: Universal & Risk-based |

Odds of CT positivity Rates of PID Participation rate Odds of participation; Unclear for performance and detection biases and incomplete outcome data (prevalence); high for incomplete outcome data (positivity) |

There was no statistical evidence of an impact on chlamydia positivity rates or estimated population prevalence from the Chlamydia Screening Implementation programme after three years at the participation levels obtained. |

| Observational studies (non-RCTs, Cohort, case-control, Cross-sectional) | ||||||

Sufrin et al., 2012 Footnote 63 USA CT & NG |

Retrospective controlled cohort; One screen G1: 5633 |

100%; did not report |

Female only 14-49 years |

Medical clinic Unknown if universal or risk-based |

Risk of PID; Unclear (selection bias with some adjustment) |

The risk of PID in females receiving IUDs was low. These results support IUD insertion protocols in which clinicians test females for N gonorrhea and C trachomatis based on risk factors and perform the test on the day of insertion. |

Campbell et al., 2006 Footnote 80 England CT |

Randomized pre - post; 1 screen; 842 |

Not reported |

M & F; |

IG: Home-based screening Universal screening |

Negative psychosocial impact Feasibility; Health Equity; General-risk, under-deprived areas over-represented in non-responders, but not for ethnicity |

Postal screening for chlamydia does not appear to have a negative impact on overall psychological well-being and can lead to a decrease in anxiety levels among respondents. |

Fielder et al., 2013 Footnote 64 USA CT & NG |

Longitudinal cohort; 1 screen 483 |

64% (310/483); NG: 0.32% |

Female only ≥18 years |

University Health Clinic; |

CT/NG Infection transmission Negative psychosocial impact Feasibility/screening rates Acceptability Barriers to testing; General risk, 1% had STI |

STI testing using self-collected vaginal swabs was acceptable to the majority of college females and could increase the uptake of testing among sexually active college females |

Reed et al., 2021 Footnote 73 USA CT & NG |

Prospective delayed start pragmatic study; One-time screening; IG1: post intervention (Main ED) CG1: 21229 (Main ED) |

IG1: 100% CG1 |

M & F 14-21 years |

IG: Emergency departments IG: Universal screening |

Positivity rates of CT/NG Proportion of patients tested for CT/GC; Moderate (confounding bias, measurement bias) |

A universally offered screening intervention increased the proportion of adolescents who were tested at both EDs and the detection rates for CT/GC at the main ED, but patient acceptance of screening was low. |

Tomcho et al., 2021 Footnote 5 USA CT & NG |

Controlled pre-post quasi-experimental (no randomization); 1 screen;

|

Preintervention period

|

M & F; 14 to 18 years |

Pediatric clinic & Family Medicine clinic; IG: Universal |

CT/NG Infection transmission Feasibility and screening rates; Low |

Universal testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea in primary care pediatrics and family medicine is a feasible approach to improve testing rates. |

Walker et al., 2013 Footnote 66 Australia CT |

1116 |

Not reported; 4.90% |

Female only; 16-25 years |

General practice, sexual health and family planning clinic; Universal |

Negative psychosocial impact Feasibility/screening rates Acceptability Barriers to testing; General-risk, 4.9% prevalence at baseline; more educated and sexually active than general population. |

The participants in the study were pleased to have been tested and supported a screening program. Females who tested positive were less concerned about having a positive result than females who tested negative. |

Table 3.2: Key Question 2 - Comparative effectiveness of a screening intervention compared to another screening intervention for CT/NG

Author, year |

Design; Intensity; Sample Size | Screening rate; Baseline CT/NG | Sex and Age | Setting of intervention; Screening approach | Outcome assessed | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Control Trial | ||||||

Reagan, 2012 Footnote 50 USA CT & NG |

Randomized control trial one screen, no follow-up. IG: 100 |

IG: 48% CT: 3.3% (1 case in home-based, 3 cases in clinic-based) |

Male only 18-45 years |

IG: Home-based screening. IG: Universal screening. |

CT/NG infection rate Unclear for performance, and detection bias. |

Home-based screening for CT and GC among males is more acceptable than clinic-based screening and resulted in higher rates of screening completion. A combination of homebased method and traditional STD screening options showed improved STD screening rates in men. |

Senok, 2005 Footnote 51 Scotland CT |

Randomized control trial (feasibility study) 1 screen IG1: 124 |

IG1: 48% IG1: 5% |

Female only 16-30 years |

IG1: Postal screening IG1: Postal screening |

Rates of returned tests Incidence of positive CT test; Unclear for sequence generation, performance and detection biases. |

This feasibility study established that opportunities exist in general practice to conduct clinical trials of differing approaches to screening. Uptake of screening was 48% of the target population with a postal approach and 21% over four months with an opportunistic approach. |

| Observational studies (non-RCTs, Cohort, case-control, Cross-sectional) | ||||||

Gasmelsid et al., 2021 Footnote 16 England CT |

Retrospective service evaluation; 1 screen 39 629 |

100%; 10.9% |

M & F Range not reported |

IG: Home-based IG: Universal |

CT Infection transmission Acceptability Barriers to testing Health equity; Moderate (missing data bias, confounding bias) |

No difference was found in the age nor level of deprivation, demonstrating that online services are an accessible way to screen for sexually transmitted infections without overburdening established services. |

Söderqvist et al., 2020 Footnote 65 Sweden CT |

Retrospective cohort study; 1 screen 567 773 (refers to number of tests, not participants) |

100%; Not reported |

M & F ≥ 15 years |

IG: Home-based IG: Universal |

CT Infection transmission Feasibility/Screening rates Health Equity; Moderate (confounding bias, selection bias, classification bias) |

Self-sampling has increased substantially in recent years, especially among females. This service is at least as beneficial as clinic-based screening for detection of CT, and self-sampling reaches males more than clinic-based testing. |

Table 3.3: Key Question 3 - Relative importance that people place on the potential outcomes from screening for CT/NG

Author, year |

Design; Sample Size | Setting of study; Screening approach | Sex; Age | Outcome assessed; ROB | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Balfe et al., 2010 Footnote 17 Republic of Ireland CT |

Qualitative Study; 35 |

General practice & Family planning clinic; No screening |

Female only; 18-25 years |

Patient preference and values in deciding to accept CT screening; General-risk |

Respondents were worried that their identities would become stigmatised if they accepted screening. Younger respondents and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds had the greatest stigma-related concerns. |

Barth et al., 2002 Footnote 72 USA STI |

Qualitative Study; 41 |

University campus; No screening |

M & F 18-22 years |

Patient preference and values in deciding to seek STI screening; General-risk (29% with 0 and 25% with >5 previous sexual partners) |

Social stigma and negative consequences appear to represent significant barriers to college students' being tested, which could increase the risk of spreading information to others. |

Booth et al., 2013 Footnote 13 United Kingdom CT |

Cross-sectional Study; 128 |

College and vocational college; No screening |

M & F 16-24 years |

Beliefs about CT testing/screening; High-risk (71% resided in deprived areas) |

This study indicates that raising awareness of chlamydia as a serious sexual health problem may not be the best way to increase the uptake of testing in a high-risk population. Promoting chlamydia testing as potentially providing reassurance may be an alternative. |

Booth et al., 2015 Footnote 74 USA CT |

Cross-sectional Study; 278 |

College and vocational college; No screening |

M & F 16-21 years |

Beliefs about intentions to test for CT; High-risk (75% from deprived areas) |

The behavioural, normative and control beliefs most strongly correlated with intentions to test regularly for chlamydia were beliefs about stopping the spread of infection, partners' behaviour and the availability of testing. These beliefs represent potential targets for interventions to increase chlamydia testing among young people living in deprived areas. |

Chacko et al., 2008 Footnote 75 USA CT & NG |

Prospective cross-sectional Study; 192 |

Community-based reproductive health clinic; No screening |

Female only; 16-21 years |

Pros and Cons of CT/NG screening; high-risk (52% ever had STI, 18% symptomatic) |

A variety of pros and cons to seeking CT and NG screening were identified at a community-based clinic. Providers in clinical settings can utilize this information when encouraging patients to seek regular STI screening by elucidating and emphasizing those pros and cons that have the most influence on a young woman's decision-making to seek screening. |

Reed et al., 2017 Footnote 73 USA CT & NG |

Qualitative study design; G1: Adolescents 80 |

Pediatric emergency department; Universal screening |

M & F G1: 14-21 years |

Acceptability of screening Patient preference; High-risk (many have poor access to healthcare, 30% tested CTPos in past from ad hoc testing approach) |

Universally offered gonorrhea and chlamydia screening in a pediatric ED was acceptable to the adolescents and parents or guardians in this study. |

Theunissen et al., 2015 Footnote 69 Netherlands CT |

Qualitative study design; G1: Tested for CT 23 |

G1: STI clinic No screening |

M & F 16-25 years |

The role of stigma on CT testing; both general- and high- risk (70% of tested were CT-positive); Unclear |

Young people perceive public stigma and anticipate self-stigma and shame in relation to CT testing, disclosure and encouraging others to test. |

Duncan et al., 2001 Footnote 70 Scotland CT |

Qualitative study design 17 |

Family planning and genitourinary medicine clinic; No screening |

Female only 18-29 years |

Psychosocial impact of diagnosis of CT on screening; High-risk due to setting & referrals (all had CT infection; 24% attributed symptoms to an infection; many not with long-term partner); Unclear |

Females are concerned about perceived stigma of STIs, their future reproductive health, and anxiety about notifying partners following the diagnosis of chlamydia. |

Mills et al., 2006 Footnote 68 England CT |

Qualitative study design 45 |

General practice clinic; Universal |

M & F 18-22 years |

Experience of individuals screened for CT; General-risk population although 50% participants chosen because CT diagnosis; Unclear |

Four main themes emerged: initial discomfort with screening arising from an unease with sexual health issues; anxiety; females's concern about being stigmatised for having been infected with chlamydia; and recognising the need to balance the harms of screening with the benefits. |

Nielsen et al., 2017 Footnote 71 Sweden CT |

Qualitative study design 15 |

Youth Health clinic; No screening |

M & F 18-22 years |

Processes involved in re-testing for CT; High-risk (all screened 2+ times over 6 months); participants 56% CT-positive; 44% CT-negative (not purposively chosen) |

Our main findings were that the fear of social stigma related to infecting a peer was a major driver of the re-testing process. |

Jackson et al., 2021 Footnote 81 United Kingdom All STIs |

Mixed Methods Qualitative arm: 43 |

Community setting; No screening |

M & F 16-24 years |

Patient preferences Negative psychosocial impact Accessibility Health Equity; Low |

The findings show that comprehensive testing and a perceived 'non-judgemental' attitude are particularly important to young people, as well as convenience. |

Reingold et al., 2023 Footnote 76 USA CT & NG |

Cross-sectional (survey) G1: Risk-based screening 406 |

Health clinic; Risk-based screening & universal screening |

M & F; 14-24 years |

Negative psychosocial impact Patient preferences; High risk |

Most participants (93%) preferred opt-out gonorrhea and chlamydia testing compared with risk-based testing (6%), and opt-out testing was associated with less sexually transmitted infection–related stigma ( P < 0.05). |

Table 3.4: Cost Effectiveness of screening interventions and health utility studies

Author, year |

Design; Intensity; Sample Size | Setting of study; Screening approach | Sex; Age | Outcome assessed; ROB | Indicator of cost effectiveness | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kuppermann et al., 2007 Footnote 77 USA |

Cross-sectional; No screening. Females seeking healthcare for PID symptoms. 1493 |

Clinical setting; No screening |

Female only; 31-54 years |

Time trade-off (how many years of their remaining lives they would be willing to give up to live without the experienced symptoms); Fair |

N/A |

Noncancerous pelvic problems are associated with serious decrements in health-related quality of life and sexual functioning and low rates of treatment satisfaction. |

Smith et al., 2008 Footnote 67 USA |

Cohort Study G1: History of PID 206 |

Clinical setting; No screening |

Female only; ≥ 18 years |

Visual analogue scale and time trade-off for health states associated with PID; Good (Fair for PID and ectopic pregnancy). Response of eligible participants NR. |

N/A |

PID has substantial impact on utility. In addition, some PID-related health states are valued less by females who have experienced PID, which could affect cost-effectiveness analyses of PID treatments when examined from the societal versus patient perspective. |

Trent et al., 2011 Footnote 82 USA |

Health Utility Assessment G1: Parents 255 |

Academic medical clinic & health department school-based health clinic; No screening |

G1: M & F G1: ≥18 years |

Time trade-off Visual analogue scale Patient preferences and values; Good (fair for PID and ectopic pregnancy). Response of eligible participants NR. |

N/A |

The findings demonstrate that adolescents assign more disutility (lower valuations) than parents for HRQL and three of five of the TTO assessments for PID-related health states. |

Stoecker et al., 2022 Footnote 78 USA CT |

Cost-effectiveness study, synthetic cohort IG: Risk-based 29 600 |

Community venues; Risk-based |

M & F 15-24 years |

Incidence of PID, chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy, infertility) Health Equity; N/A |

QALY Cost effectiveness ratio |

The Check It program (a bundled seek, test, and treat chlamydia prevention program for young Black men) is cost-effective under base case assumptions. Communities where Chlamydia trachomatis rates have not declined could consider implementing a similar program. |

Rönn et al., 2023 Footnote 79 USA CT |

Cost-effectiveness modelling Scenario 1: More constrained priors on reporting and screening |

N/A |

M & F 15–18 years |

Cost-effectiveness |

QALY ICER |

Sustained high student participation in school-based screening programs and broad coverage of schools within a target community are likely needed to maximize program benefits in terms of reduced burden of chlamydia in the adolescent population. |

Wang et al., 2021 Footnote 15 Florida, USA CT, epididymitis & PID |

Cost-effectiveness analysis IG: School-based screening 5388 |

IG: School IG: Universal school-based |

M & F 14-19 years |

Positivity rates Cost-effectiveness |

QALY ICER |

The cost/QALY gained could be <$50,000/QALY if student participation rate was >7%. The TeenHC chlamydia screening has the potential to be cost-effective. |

Wang et al., 2021 Footnote 14 Michigan, USA CT, epididymitis & PID |

Cost-effectiveness analysis IG: School-based screening Not applicable |

IG: School IG: Universal school-based |

Not applicable |

Estimated prevented cases Cost-effectiveness |

QALY |

We found favorable cost-effectiveness ratios for Michigan's school-wide STD screening program in Detroit. School-based STD screening programs of this type warrant careful considerations by policy-makers and program planners. |

Table 3.5: Evidence profile | Key Guideline Question: Should [Any screening1] vs. [No screening/usual care/any screening2 be used for [non-pregnant people]?

| Outcomes by organisms (CT, NG and CT+NG) and screening type | Findings |

|---|---|

Chlamydia: Universal screening compared to no screening or usual care |

n/a |

Chlamydia infection transmission (1 RCT (van den Broek et al., 2012)) |

A registered based yearly program found Chlamydia positivity in the intervention blocks at the first invitation was the same as in the control block/Usual care (4.3%) and 0.2% lower at the third invitation than in the control block/Usual care which was not statistically significant (odds ratio 0.96, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.10). |

Certainty of evidence |

⨁⨁◯◯Footnote 1 Low Risk of bias, Indirectness |

Chlamydia and Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (3 RCTs) Oakeshott, 2010; (van den Broek et al., 2012; Hocking et al. 2018) |

Universal screening compared to usual care in primary care did not significantly reduce prevalence of chlamydia in adolescents and young adults. Screening for chlamydia reduces rates of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); however, the effectiveness of a chlamydia test in preventing PID over 12 months may be overestimated. |

Certainty of evidence |

⨁◯◯◯Footnote 1,Footnote 2 Very low Risk of bias, Indirectness |

Benefits: Gonorrhea Screening - nil |

n/a |