Federal Framework on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Recognition, collaboration and support

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 2.1 MB, 94 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2019-01-22

Related Topics

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Minister's message

- Executive summary

- Part I: Context and background

- Organizational roles and responsibilities

- Informing the Framework

- Part II: The Federal Framework on PTSD

- The Framework at a glance

- Scope and purpose of the Framework

- Vision

- Guiding principles

- Priority areas

- Priority Area 1: Improved tracking of the rate of PTSD and its associated economic and social costs

- Priority Area 2: Promotion of guidelines and sharing of best practices related to the diagnosis, treatment and management of PTSD

- Priority Area 3: Creation and distribution of educational materials related to PTSD to increase national awareness and enhance diagnosis, treatment and management

- Priority Area 4: Strengthened collaboration and linkages among partners and stakeholders

- Part III: Moving forward

- Conclusion

- Part IV: Appendices

- Appendix A – Federal Framework on PTSD Act and observations from the Senate Committee

- Appendix B – Other populations affected by PTSD

- Appendix C – Current PTSD initiatives in Canada

Abbreviations

- CAF

- Canadian Armed Forces

- CCG

- Canadian Coast Guard

- CFNU

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Union

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CIMVHR

- Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research

- CIPSRT

- Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment

- CISM

- Critical Incident Stress Management

- CSIS

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- DFO

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- EAP

- Employee assistance programs

- EAS

- Employee Assistance Services

- LGBTQ2

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Two-Spirit

- MHCC

- Mental Health Commission of Canada

- MHFA

- Mental Health First Aid

- OSI

- Operational stress injury

- OSISS

- Operational Stress Injury Social Support

- OTSSC

- Operational Trauma and Stress Support Centres

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PSC

- Public Safety Canada

- PTSD

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- PTSI

- Posttraumatic Stress Injuries

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- VAC

- Veterans Affairs Canada

Acknowledgements

The Federal Framework on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)Footnote a was developed in recognition of those who live with PTSD, their families and support networks and those who are at risk of developing PTSD.

We are deeply grateful for the impassioned involvement of the many partners and stakeholders who informed the development of the Framework through: the National Conference on PTSD in April 2019; our official governance structure; and, the many conversations that have taken place since the Federal Framework on PTSD Act received Royal Assent in June of 2018. These partners and stakeholders include federal government departments, non-governmental organizations, provincial and territorial groups and governments, Indigenous organizations and other experts reflecting the diversity of Canada's geographical and social communities.

Many who contributed to the Framework have experienced PTSD firsthand. We acknowledge their lived and professional expertise and are grateful for their candour in sharing their insights.

Finally, we acknowledge that symptoms of PTSD are not always recognized by individuals, family members, co-workers, support networks, health care providers, or employers. Stigma and other barriers to timely diagnosis, care and treatment remain. The Framework, which would not have been possible without our partners and stakeholders, will help us work together to address these challenges.

If you or someone you know needs mental health support, you are not alone. Please visit the Government of Canada Mental Health Support web page for more information.

Minister's message

I am privileged to share Canada's first Federal Framework on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Many Canadians may develop PTSD during their lifetimes in the wake of exposure to trauma. The Framework recognizes that a great number face increased risks because of the unique nature and demands of their occupation.

The release of the Framework marks an important milestone in our efforts to better recognize, collaborate with and support those impacted by PTSD. The content was informed by a national conference on PTSD held in April 2019, and further developed with the direct involvement of a diverse group of stakeholders and partners, including those with lived experience. We heard many inspiring stories of courage and healing. At the same time, we heard about significant gaps and lack of access to PTSD supports across Canada. We are hopeful that many of the relationships we have built during the development of the Framework will continue to grow as we move forward to address these gaps.

While important advances have been made in a relatively short period, our work must continue. The call to action from our partners and stakeholders was evident: we must end the stigma, improve our understanding of PTSD, promote evidence-based practices for its treatment and management, increase awareness and learn from each other by working collaboratively.

As we move forward, the Framework can guide our collective efforts. It encourages us to work together to advance our knowledge of PTSD, while building on many important initiatives and investments that are already in place.

Through the actions outlined in the Framework, we hope to make a meaningful difference in the lives of those affected by PTSD. I sincerely thank all those who contributed to the Framework's development and have helped us get to this point. I am confident that with the help of our partners and stakeholders, we can achieve the vision set out in this document, "A Canada where people living with PTSD, those close to them, and those at risk of developing PTSD, are recognized and supported along their path toward healing, resilience, and thriving."

The Honourable Patty Hajdu, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Health

Quotes

"The Government of Canada is providing national leadership to help address the mental health needs of Canadians who are impacted by PTSD and post-traumatic stress injuries (PTSI). Public safety personnel put their lives on the line every day, which can put them at risk of developing PTSI. That is why last April we released a national action plan on PTSI for all public safety personnel across Canada. I am pleased to see the Federal Framework on PTSD building on this work and the work of others."

The Honourable Bill Blair

Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness

"While we have come a long way in our understanding of the invisible wounds that Canada's Veterans may be struggling with, we know more must be done. With this Framework, our government pledges to support effective programs and treatment for all these brave Canadians. I congratulate everyone who contributed to the creation of this Federal Framework, and I thank all the brave Canadians it will serve for their sacrifices."

The Honourable Lawrence MacAulay

Minister of Veterans Affairs

"Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can have a profound impact on those faced with it and on their families, friends and colleagues. The Department of National Defence proudly supports the Federal Framework on PTSD. Through education, early intervention and world-class treatment we will make sure the women and men of the Canadian Armed Forces receive the highest standard of health care and support."

The Honourable Harjit Sajjan

Minister of National Defence

Executive summary

The Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Act became law on June 21, 2018, after receiving all-party support in Parliament. The Act underscores the diversity of occupational groups at higher risk of developing PTSD and the need for a coordinated approach to support those affected. As such, the Act called for the development of a comprehensive federal framework, informed by a national conference. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) was mandated to lead this work.

The National Conference on PTSD was held on April 9-10th, 2019, in Ottawa. Over 200 conference participants representing a wide-range of partners and stakeholders, including individuals with lived-experience, provided meaningful and productive dialogue on issues pertaining to:

- improved tracking of the rate of PTSD and its associated economic and social costs;

- the promotion of guidelines and sharing of best practices related to the diagnosis, treatment and management of PTSD; and,

- the creation and distribution of educational materials related to PTSD to increase national awareness and enhance diagnosis, treatment and management.

While the National Conference was the main consultation mechanism, engagement with partners and stakeholders continued throughout the development of the Framework. The entirety of engagement activities, as well as the requirements stated in the legislation, provided the foundation for the Framework.

Part I provides background and context, defining PTSD and providing information on occupations and populations at higher risk of developing PTSD. It describes key organizational roles and responsibilities for PTSD in Canada and summarizes the engagement that took place to inform this Framework, including highlights from the National Conference.

Part II, the heart of the Framework, sets out the scope, purpose, vision and guiding principles, including the importance of complementing existing initiatives and leveraging partnerships in addressing PTSD. This section also provides information on the drivers and considerations for each of the priority areas set out in the legislation, as well as federal actions setting the path to progress in each of them. Finally, an additional priority area highlighting the importance of collaboration among partners and stakeholders, which was not specifically articulated in the Act, is included in this section.

Part III outlines next steps in implementation, including the role of the PTSD Secretariat at PHAC. It reiterates the need for collaboration with all partners and stakeholders in advancing the priority areas, and encourages all parties to build on the vision and guiding principles of the Framework in advancing their own initiatives in the area of PTSD. It concludes by stating that the Framework is intended to encourage continuous open dialogue and that as we learn more about PTSD, the actions under this Framework will undoubtedly continue to evolve.

Additional information is provided in the Appendices. This section includes an overview of a number of non-occupation related populations at increased risk of developing PTSD, a high level synopsis of current PTSD initiatives in Canada, and a Glossary outlining definitions related to PTSD and trauma developed by the Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT) in collaboration with a number of experts.

As mandated by the Act, PHAC will complete a review of the effectiveness of the Framework within five years from the date of this Framework's publication.

Part I: Context and background

Introduction

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has an enormous impact on individuals, families, caregivers, and workplaces. All Canadians can be at risk for PTSD following exposure to trauma, but some populations are at greater risk because of the type of job they do. That is why in June 2018, the Government of Canada enacted the Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Act (the Act), which called for the development of a Federal Framework on PTSD (the Framework). The Act, as well as the Observations provided by the Senate Standing Committee on National Security and Defence at the time of enactment, are included as Appendix A.

The Act specified three priority areas for the Framework:

- Improved tracking of the incidence rate and associated economic and social costs of PTSD;

- The establishment of guidelines regarding:

- the diagnosis, treatment and management of PTSD, and

- the sharing throughout Canada of best practices related to the treatment and management of PTSD; and

- The creation and distribution of standardized educational materials related to PTSD for use by Canadian public health care providers that are designed to increase national awareness about the disorder and enhance its diagnosis, treatment and management.

This Framework addresses occupation-related PTSD and builds on existing federal initiatives, such as Supporting Canada's Public Safety Personnel: An Action Plan on Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries, which focuses on supporting the mental health of public safety personnel, and the recently created Centre of Excellence on PTSD and Related Mental Health Conditions, funded by Veterans Affairs Canada.

The Framework acknowledges that people can be affected by PTSD outside of the occupational setting and broad applicability will be considered in the implementation of federal actions.

What is PTSD?

PTSD is a mental disorder that may occur after a traumatic event where there is exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.Endnote 1 Potentially traumatic events include war/combat, major accidents, natural- or human-caused disasters, and interpersonal violence. PTSD can affect any person regardless of age, culture, occupation, sex, or gender.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a diagnosis of PTSD requires that the trauma be experienced throughEndnote 1:

- Direct personal exposure.

- Witnessing of trauma to others.

- Indirect exposure: learning that the traumatic event occurred to a family member or close associate.

- Firsthand repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of a traumatic event(s).

Most people recover in a relatively short period following a traumatic event; however some people experience symptoms that worsen and persist over months or years. In some cases, the onset of symptoms may not appear until months or years after the experience. At present, we do not fully understand the biological, psychological, social, and environmental reasons for why individuals can react very differently to the same traumatic event.

A diagnosis of PTSD requires that symptoms be present for more than one month and cause significant distress or impairment in function. Symptoms of PTSD includeEndnote 1:

- Recurring, involuntary, intrusive, and distressing memories, nightmares, and/or flashbacks.

- Avoidance or attempts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, feelings, or reminders of the event.

- Persistent negative changes in thoughts or mood (e.g., negative emotions, diminished interest in activities, inability to experience positive emotions, feelings of detachment).

- Changes in arousal or reactivity (e.g., irritable behaviour, angry outbursts, reckless or self-destructive behaviour, hyper-vigilance, exaggerated startle response, trouble concentrating, or disturbed sleep).

PTSD often occurs with other mental health conditions such as depression and substance use disorders; chronic diseases and conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and chronic pain;Endnote 2,Endnote 3 and, suicidal thoughts and behaviours.Endnote 4,Endnote 5

The terms posttraumatic stress injury (PTSI) and operational stress injury (OSI) are increasingly used to describe mental health conditions related to traumatic events. On occasion, PTSI and OSI have been used interchangeably. By definition, a PTSI does not necessarily involve an injury following exposure to a traumatic event while serving in a professional capacity, whereas an OSI implies the injury was sustained as a result of operational duty. These non-clinical terms capture the full range of mental injuries that can occur following a traumatic event and include PTSD, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, or substance use disorders. PTSI and OSI are used in an intentional effort to reduce stigma associated with other language (e.g., mental disorder or mental health problems).Endnote 6

Although the Framework focuses on PTSD as a clinically diagnosed mental health condition, the Government of Canada acknowledges that many different mental health conditions can result from exposure to traumatic events.

Can PTSD be prevented?

Currently, the only way we know of to prevent PTSD is to avoid exposure to traumatic events. Although mental health education and resiliency training can be beneficial, there is no evidence that these programs prevent the development of PTSD. The same is true of pre- or post- trauma debriefings.Endnote 7,Endnote 8

We do know that mental health education to increase knowledge and coping skills can alert people to early signs and symptoms of conditions such as PTSD, and may lead to early treatment-seeking behaviours. Timely evidence-based treatment of PTSD will help decrease the risk of long-term negative outcomes. This is especially important in cases where trauma exposures are more frequent due to the nature of an occupation.Endnote 9

Following exposure to a potentially traumatic event, many people experience distressing symptoms such as poor sleep, nightmares, and increased anxiety. However, the majority will recover from these symptoms spontaneously. Time, self-care and social support help, but some will go on to develop PTSD. Some evidence suggests that the severity of a traumatic event, lack of social support, or a history of adverse childhood experiences or previous mental health conditions can add to the risk of developing PTSD.Endnote 10,Endnote 11,Endnote 12

Who is affected by PTSD?

About three quarters of Canadians are exposed to one or more events within their lifetime that could cause psychological trauma.Endnote 13

A study using nationally representative data collected in 2002, based on self-reported symptoms, indicated that lifetime prevalence of PTSD in Canada was 9.2% and current (past month) prevalence was 2.4%.Endnote 13

The Canadian Community Health Survey – Mental Health, a nationally-representative survey in which participants were asked if they had a current diagnosis of PTSD, indicated prevalence rates of 1.0% in 2002 and 1.7% in 2012. An increase over time was observed among females — 1.2% in 2002 and 2.4% in 2012. The rates for males remained stable over time.Endnote 14

PHAC conducted a systematic review on the prevalence of PTSD in Canadian studies and found that data on PTSD is limited and updated statistics are needed. Reported rates of PTSD can vary across surveys because questions about PTSD are asked in different ways. The timeframe of questions can be shorter (e.g., past month) or longer (e.g., lifetime), with longer timeframes leading to higher rates. Some questionnaires collect data based on PTSD symptoms while others ask if an individual has been diagnosed with PTSD.Endnote 15

Many individuals with PTSD will not seek treatment because of stigma, lack of awareness, or other barriers. Also, individuals may be reluctant to share detailed mental health information. As a result, questions about a PTSD diagnosis may lead to different estimates than those based on symptom assessments, and both methods likely underestimate the true prevalence.

Sex, gender, and other factors can influence risk and vulnerability, access to health services, and socioeconomic consequences at different points in the life cycle. These factors intersect and can result in unique challenges that further complicate PTSD assessments and require additional research.

PTSD in men and women

- PTSD appears to be twice as common in women as in men.Endnote 16

- Men and women present symptoms of PTSD differentlyEndnote 17,Endnote 18:

- Women are more likely to report symptoms of numbing and avoidance, as well as concurrent mood and/or anxiety disorders.

- Men are more likely to report symptoms of irritability and impulsiveness, as well as concurrent substance use disorders.

- The uneven distribution of men and women in certain professions leads to research challenges. For example, over 90% of Canadian nurses are womenEndnote 19,Endnote 20 and over 95% of Canadian firefighters are men.Endnote 21

*Information about other gender identity and expressions is provided in Appendix B.

Below are some available data, evidence, and considerations for specific populations in Canada that are at increased risk for developing PTSD. This information is not intended to exclude any occupational group or population. Research and evidence about PTSD continues to evolve and it is possible that there are additional groups or occupations at higher risk.

Canadian Armed Forces Serving Members and Veterans

Canadian Armed Forces Serving Members

There are two broad categories of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) membership: 1) Regular CAF members, who make a full-time commitment and often have dedicated their career to military service; and 2) Reserve Forces who generally work part-time in addition to pursuing their regular career or education. Both types of members can be enrolled in the Navy, Army, or Air Force.

Military-related PTSD can result from exposure to traumatic events experienced during training, deployment-related combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations, or as a result of non-deployment trauma (e.g., military police).Endnote 22 PTSD rates among serving military personnel and Veterans increase proportionately to their exposure to traumatic and disturbing events such as participating in combat roles, and events that transgress deeply held moral and ethical standards. (See text box on the concept of moral injury).Endnote 23 Among serving military personnel and Veterans, exposure to non-military related potentially traumatic factors, such as adverse childhood experiences, are also thought to play a role in susceptibility to PTSD in later life.Endnote 24

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) has reliable estimates of mental disorders in serving CAF members based on collaborative work with Statistics Canada and other related studies. According to a 2014 report, the number of active CAF Regular Forces members who reported symptoms of PTSD nearly doubled from 2002 to 2013 (from 2.8% to 5.3%).Endnote 25 In 2013, 16.5% of active CAF members had evidence of one or more of six mental disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder, PTSD, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). Traumatic events experienced during deployment may be associated with a higher risk for mental disorders and suicide.Endnote 26

What is Moral Injury?

Moral Injury is an evolving concept that continues to be discussed among experts. It usually refers to a type of psychological trauma characterized by intense guilt, shame, and spiritual crisis. It can result from experiencing a significant violation of deeply held moral beliefs, ethical standards, or spiritual beliefs, experiencing a significant betrayal, or witnessing trusted individuals committing atrocities. Moral Injury has also been described as an injury to identity, core being, spirit, and sense of self that results in fractured relationships.Endnote 6

Canadian Armed Forces Veterans (Former CAF Members)

Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) has reliable estimates of the prevalence of self-reported PTSD diagnoses in Veterans based on collaborative work with Statistics Canada. The prevalence of PTSD in Regular Force Veterans released from service during 1998-2012 and surveyed in 2013 was 13.1%. The rate was significantly higher than the general population, even after accounting for age and sex.Endnote 27 The prevalence of self-reported PTSD in Reserve Force Veterans deployed on operational duties with the Regular Force was 7.5%, which was also higher than the general population. Similar results were seen in Regular Force Veterans released during 1998-2015 and surveyed in 2016, where 16.4% reported PTSD.Endnote 28 In international studies, PTSD is usually higher in Veterans than among active serving members.Endnote 23 This may reflect in part the stresses that Veterans face when they leave the military and transition to civilian life or by differences in survey methods.Endnote 27

Public safety personnel

Public safety personnel include frontline personnel who ensure the safety and security of Canadians across all jurisdictions such as police, firefighters (career and volunteer), paramedics, correctional employees, border services personnel, operational and intelligence personnel, search and rescue personnel, Indigenous emergency managers, and public safety communications personnel (e.g., 911 operators, dispatchers). Given the broad range of occupations within the public safety community, it is important to recognize their distinct contexts and considerations related to experiences of trauma.

Public safety personnel may be at increased risk of PTSD because their jobs routinely expose them to a range of traumatic events.Endnote 29 They respond to crimes, accidents, and disasters and may witness or experience serious injuries, threats to life or death, as well as long-term exposure to disturbing material or communications. Feelings of guilt and shame may also contribute to the development of PTSD symptoms, particularly in situations where they were unable to help, identified with the victim or were overwhelmed by the event.Endnote 30

In a study conducted in 2016 and 2017, 44.5% of participating public safety personnel reported clinically significant symptoms consistent with one or more mental disorders. An estimated 23.2% showed symptoms of PTSD.Endnote 31

Health care providers

Nurses, physicians, psychologists, social workers, and other health care providers witness trauma, pain, suffering, and/or death on a regular basis in their work to care for the health of individuals, families, and communities.Endnote 32 Research about PTSD in health care providers in Canada is limited; however, available studies indicate that PTSD rates among health care providers are higher than in the general population.Endnote 33 For example, a report released in 2015 by the Manitoba Nurses Union indicated that one in four participating nurses reported PTSD symptoms. The same document indicated that 43% of new nurses experience high levels of psychological distress because of their work.Endnote 19,Endnote 20

Health care providers may also be called to care for individuals who remind them of loved ones, which can result in feeling guilt and shame if they are unable to help.Note de fin de document 19,Endnote 34 They may experience higher rates of compassion fatigue and/or burnout when caring for, empathizing with, and emotionally investing in, people who are suffering.Endnote 35 In addition, violence toward health care providers, such as nurses, is a serious concern and likely functions as a contributing factor to the development of PTSD.Endnote 19,Endnote 20,Endnote 36

Other occupations

There are other occupational roles or professions that also face an increased risk for developing PTSD. For example:

- Jurors may experience vicarious trauma as a result of exposure to traumatic content in the context of legal trials related to violent crimes.Endnote 37

- Journalists are exposed to potentially traumatic events when they arrive early on the scene and/or report about the circumstances of the event. Journalists (especially war correspondents) may also face an increased risk of personal physical harm.Endnote 38

Indigenous People who work in high-stress occupations and additional considerationsFootnote b

First Nations, Inuit and Métis individuals working in high-stress occupations (such as public safety personnel and health care providers) face unique challenges.

These frontline workersFootnote c are an integral part of Indigenous communities. Consequently, communities often have high expectations towards these workers. As a result, it may be difficult for frontline workers to set and maintain personal and work-life boundaries. In some cases, they may be the only one providing a specialized service in their community, and may have to intervene in a professional capacity during traumas and critical incidents involving family members or friends. They may also take on multiple roles in their community (e.g., as both a frontline worker and as a decision maker or leader determining how to respond organizationally or politically to a family or community crisis).Endnote 39 As a result, they may experience many different impacts from a singular trauma, which can lead to feelings of helplessness, numbness, avoidance and a reduction in empathy.Endnote 32

In addition, First Nation, Inuit and Métis frontline workers often serve communities that experience higher rates of poverty, mental health conditions, crime, or victimization.Endnote 40 Other challenges they may face include lack of resources and unsupportive human and organizational infrastructures. These challenges may worsen their own histories of trauma and put them at greater risk of experiencing mental health conditions, including PTSD.Endnote 41 The lack of resources and infrastructure also means there is often limited support to help frontline workers deal with the cumulative impact of stress and trauma, leading to potential long-term negative effects on their mental health and wellbeing.Endnote 42 All of these factors are magnified for workers in remote communities, who may also be confronted with isolation and extreme environmental conditions.Endnote 41

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples working in high-stress occupations outside Indigenous communities (e.g., in an urban center like Toronto or while serving in the Canadian Armed Forces) may also have their own personal history of trauma, which can increase their risk of developing mental health conditions, including PTSD.Endnote 43

Finally, non-Indigenous frontline workers serving Indigenous communities may also experience challenges. For example, many Indigenous communities employ or receive nursing services by non-Indigenous nurses. These nurses may find themselves ill-equipped to manage the layers of trauma with the scarcity of human and practical resources available to them which can affect their wellbeing and mental health.Endnote 44

Unique factors that impact PTSD in Indigenous Peoples

Historical and current trauma among First Nations, Inuit and Métis is significant and well documented by initiatives such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.Endnote 45,Endnote 46 Past colonization policies have resulted in intergenerational, social and community trauma, which continue to impact the health and wellness of Indigenous Peoples and communities.Endnote 47

First Nations, Inuit and Métis have distinct histories, contexts, world views and knowledge systems that need to be considered to understand and treat PTSD within those populations, whether in an occupational setting or not.

Other populations

Many people are at increased risk for PTSD as a result of experiences outside of an occupational setting such as survivors of sexual or interpersonal violence, refugees, LGBTQ2 populations, Indigenous Peoples, people experiencing homelessness, as well as survivors of major accidents or disasters. Each of these populations face a unique set of circumstances, complexities, and challenges that impact the diagnosis, treatment, and management of PTSD. Appendix B provides a high-level overview of PTSD from experiences outside of occupational settings.

Organizational roles and responsibilities

To address PTSD in Canada, we require the knowledge, expertise, and involvement of organizations from multiple sectors and disciplines. These include federal, provincial/territorial, regional and local governments, the research and academic community, pan-Canadian health organizations, non-government organizations, employers, and community organizations.

In addition to these organizations, health care providers are central to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of PTSD. The experiences and expertise of people with lived experience – the individuals living with PTSD and their families and peers – inform our efforts and compel us to action.

This section outlines some of the current roles and responsibilities of governments, employers, and other stakeholders.

Government of Canada

The Government of Canada fosters connections, provides information, supports research and innovation, and undertakes activities to promote and protect the physical and mental health of Canadians. The Government of Canada is a leader, partner, funder, and convenor on issues of importance to Canadians, including PTSD.

The Government of Canada provides or funds some direct health care services (including mental health services) to groups under federal jurisdiction. These groups include serving members of the CAF, First Nations living on reserve and Inuit living in the North, and federal inmates.

The federal government also funds and administers supplementary and occupational health care benefits (including coverage for mental health services) for members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Veterans, First Nations and Inuit populations, as well as refugees, asylum claimants and other specific, vulnerable foreign nationals. Many people within these populations are at higher risk of developing PTSD.

The federal government is Canada's largest employer and has prioritized workplace mental health by adopting procedures and measures, as well as championing initiatives that promote positive mental health in the workplace.

Provincial and territorial governments

Provincial and territorial governments provide leadership, policy direction, and programs that support the health of their residents, and the delivery of services under their jurisdiction. This includes health care and other social services, including mental health supports, such as hospital services, crisis intervention, treatment, and follow-up. Provinces and Territories also have workers compensation boards, which have responsibilities related to health and labour issues.

All provinces and territories have mental health strategies, which focus on upstream approaches (i.e., promote positive mental health, resiliency, and wellness across the lifespan), mental health services, stigma reduction, and treatment. These strategies recognize the impacts of trauma (including intergenerational and historical trauma) on mental health and as a risk factor for substance-related harms and suicide.

Most provinces and territories have recognized the impact that certain occupations can have on an individual's mental health and have implemented corresponding presumptive legislation for workers' compensation claims. (See text box.) The intention is to allow for early intervention, which should help to mitigate aggravation or recurrence of mental health challenges such as PTSD.

Presumptive Legislation

Presumptive Legislation Presumptive legislation facilitates workers' compensation coverage by presuming, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, that the injury or illness is work related. Presumptive legislation may be limited to PTSD and a narrow group of occupations (e.g., police, firefighter, paramedic) and/or may be more broadly applicable to mental illnesses beyond PTSD and to a broader scope of occupations, or all occupations.

Employers

All employers including federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal governments, as well as non-governmental organizations and private sector companies have a responsibility to ensure the health and safety of their employees. Employers must think ahead and act proactively to minimize or protect against psychological injuries and promote psychological wellbeing. Wherever possible, these efforts should be based on peer-reviewed research and the best available practices as indicated by scientist-practitioners with appropriate mental health expertise and experience.

In occupations where there is a higher risk of employees developing PTSD, some employers have implemented specific mental health initiatives. The CAF developed the Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) training program to promote early awareness of distress, encourage care-seeking, normalize mental health challenges, and provide evidence-based skills to manage the demands of service and daily life. The CAF recently adapted the most recent version of the R2MR program to create an edition appropriate for delivery to public safety personnel and this training is being made available across Canada through the collaborative efforts of Public Safety Canada, the CAF, and the Canadian Institute of Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT).

Many workplaces (including the federal government) have established employee assistance programs (EAP) to assist employees with personal problems and/or work-related issues that may impact their job performance as well as their physical/mental health, and emotional wellbeing. EAPs usually offer free and confidential assessments, short-term counselling, referrals, and follow-up services for employees and their families.

Stakeholder and community groups

Across Canada, multiple stakeholders and communities are mobilizing to address the challenges of PTSD and related mental health conditions. These stakeholder organizations (often led by individuals with lived experience) operate at both the national and regional level. They can provide services and peer support, as well as leadership and expertise to strengthen research, innovation, knowledge exchange and awareness, and to develop tools and resources for Canadians, employers, and health care providers. Many stakeholder organizations work closely and collaboratively with governments to inform policy, and advocate on behalf of people experiencing PTSD.

Informing the Framework

The implementation of the Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Act and the resulting Federal Framework on PTSD was coordinated by PHAC in collaboration with multiple partners and stakeholders.

PHAC engaged with more than fifteen federal government departments to foster connections and share initiatives related to PTSD and other occupation-related mental health conditions. PHAC also consulted with stakeholder groups who fell within the scope of the Act and other experts in the field of PTSD and mental health.

In October 2018, an early stakeholder consultation was held on the margins of the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research (CIMVHR) Forum. This consultation was attended by members of the CIPSRT Public Safety Steering Committee, members of the CIMVHR Technical Advisory Committee, and key federal departments.

As specified in the Act, in April 2019, a National Conference on PTSD took place in Ottawa, Ontario. This conference was the main engagement mechanism to obtain a variety of perspectives for the development of the Framework. The conference brought together 200 diverse participants and encouraged collaboration and knowledge sharing across sectors and disciplines. Participants included: representatives of occupational groups at higher risk for PTSD, people living with PTSD and their support networks, researchers/academics, health care providers, representatives of populations at higher risk for PTSD, Indigenous groups, federal and provincial government representatives, workers' compensation board representatives, and Pan-Canadian health organizations.

To ensure the Indigenous context and considerations were well reflected in the Framework, PHAC continued to engage with Indigenous organizations through a First Nations Reference Group on PTSD, the Métis Nation Health Committee, and the National Inuit Committee on Health.

Key themes from the National Conference on PTSD

- Health care benefits and access to care and resources vary across the country and across different occupational groups – Some occupational groups have access to a variety of educational tools and services, but others struggle to receive basic supports. These disparities were particularly salient for individuals in rural and remote communities, as well as those in volunteer positions, and in certain medical professions, such as nurses. For example: a nurse living in a remote location may experience a very different path to treatment than a nurse located in an urban centre; volunteer firefighters may not be eligible for the same health benefits as their paid counterparts; and, services and benefits offered to municipal police services may not be analogous to those offered federally to the RCMP.

- There is a need to achieve parity between physical and mental health – There is general knowledge of PTSD, but stigma remains an ongoing barrier to care and treatment. Participants shared that some individuals fear that seeking help will hinder their careers. Others shared that while workplace policies may be in place to support individuals with PTSD, longstanding occupational cultures and organizational leadership continue to reinforce the perception that mental health conditions such as PTSD are a sign of weakness. Participants also noted the importance of continued research, including in the field of identifying biological markers for PTSD.

- A number of resources exist, but there is a need for comprehensive ways to share evidence-based best practices – Participants reported that the amount of information on PTSD can be overwhelming and there may be opportunities to use or build on successful initiatives; however, knowing what is truly of value to help persons living with PTSD in their recovery can be extremely difficult. Participants expressed the need for standardized evidence-based resources that can be adapted (e.g., based on the community, culture, sex or gender). Indigenous participants expressed the need for studies that involve individuals of Indigenous ancestry and that use culturally appropriate methodologies. Participants also noted the need for consistent language and terminology around PTSD.

- PTSD has impacts beyond the individual. There is a need to consider how families, children and the diagnosed individual's support networks are affected – On several occasions participants shared that spouses, children, family members and other support networks of those who experience PTSD are significantly affected by a loved one's PTSD. Individuals in the immediate social circle of a person with PTSD can be important assets in recovery; however, the same individuals will also require effective supports to best assist the person living with PTSD, as well as to maintain their own mental health and wellbeing.

- There is a need for quality and timely data, as well as qualitative input and insight from individuals with lived experience to inform policies and programs – Participants and experts agreed that the current available data on PTSD has significant gaps and is, at times, outdated. They commented on the power of sharing personal stories in helping those who are struggling, and in informing policies and programs. Participants also emphasized the importance of sharing personal stories in a safe and sensitive way.

- There is a need to improve organizational capacity to respond to and support employees at higher risk of developing PTSD– More proactive and early intervention initiatives are required to help employees recognize PTSD symptoms, seek treatment when needed, and strengthen their support networks and resilience (e.g., including peer support, return-to-work strategies, and training that promotes healthy coping). Finally, participants emphasized the importance of trauma-informed approaches as a means of reducing stigma, supporting employees, and shifting organizational culture so that all staff are aware and able to integrate knowledge of trauma into practice.

Part II: The Federal Framework on PTSD

Federal Framework on PTSD – at a glance

Scope

The focus of the Framework is on occupation-related PTSD. The Framework also acknowledges people affected by non-occupation-related PTSD and broad applicability will be considered in the implementation of federal actions.

Purpose

Strengthen knowledge creation, knowledge exchange and collaboration across the federal government, and with partners and stakeholders, to inform practical, evidence-based public health actions, programs and policies, to reduce stigma and improve recognition of the symptoms and impacts of PTSD.

Vision

A Canada where people living with PTSD, those close to them, and those at risk of developing PTSD, are recognized and supported along their path toward healing, resilience, and thriving.

Guiding principles

- Complement current initiatives and leverage partnerships.

- Advance compassionate, non-judgemental and strengths-based approaches.

- Base initiatives on evidence of what works or shows promise of working.

- Understand and respond to equity, diversity and inclusion.

- Apply a public health approach.

Priority areas

Data and tracking

- Explore strategies to support national surveillance activities and examine the feasibility of using health administrative data and enhanced data linkages to capture and report on PTSD.

- Continue supporting data collection on PTSD.

Guidelines and best practices

- Work with partners and engage experts to compile existing guidance on PTSD and identify where gaps may exist.

- Continue to support research to bridge PTSD-related information gaps, inform effective guidance for health care providers, and advance evidence-based decision making.

Educational materials

- Work with partners and engage health care providers to identify current PTSD educational materials, understand the educational gaps, and seek advice on best practices for the dissemination, adaptation, and uptake of educational materials.

Strengthened collaboration

- Work with partners and stakeholders to identify the best mechanism(s) to increase collaboration among key departments, partners and stakeholders, as well as for ongoing sharing of information, including uptake of common and culturally appropriate terminology, definitions, and safe language about PTSD and trauma.

Scope and purpose of the Framework

The Federal Framework on PTSD establishes the Government of Canada's vision, guiding principles, and actions to address occupation-related PTSD, as they relate to the three legislated areas of priority.

The purpose of the Framework is to strengthen knowledge creation, knowledge exchange and collaboration across the federal government, and with partners and stakeholders, to inform practical, evidence-based public health actions, programs and policies, to reduce stigma and improve recognition of the symptoms and impacts of PTSD.

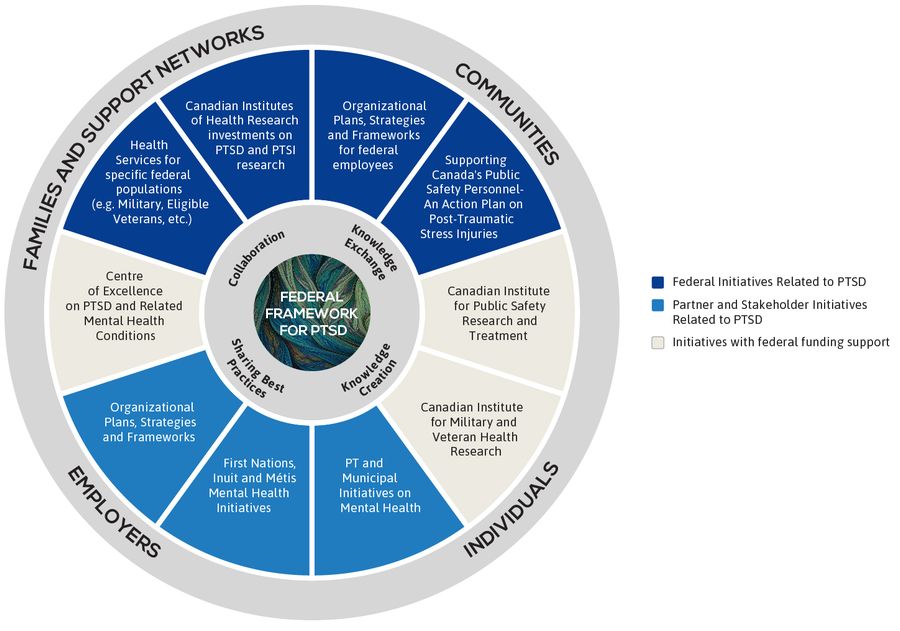

Appendix C lists PTSD initiatives currently underway in Canada, including federal initiatives to support high-risk populations. The following graphic illustrates how the various ongoing initiatives can connect to the Framework to help those impacted by PTSD.

Figure 1. Linking other existing initiatives to the Federal Framework on PSTD

Figure 1 - Text Description

The image is a circle with inner and outer rings, showing the Federal Framework on PTSD at the centre, surrounded following four key words describing its purpose: collaboration, knowledge creation, knowledge exchange, and sharing best practices.

The middle ring shows how various, ongoing initiatives can connect to the Federal Framework to help those impacted by PTSD. There are three types of initiatives described with examples provided under each type of initiative.

The first set shows federal initiatives related to PTSD (appearing in dark blue) including:

- Health services for specific populations (e.g. military, eligible Veterans, etc.);

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research investments in PTSD and PTSI research;

- Organizational plans, strategies and frameworks for federal employees; and

- An Action Plan on Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries in support of Canada's Public Safety personnel.

The next set shows initiatives that have received federal funding (appearing in beige) including:

- The Centre of Excellence on PTSD and Related Mental Health Conditions;

- The Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment; and

- The Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research.

Finally, the last set shows partner and stakeholder initiatives related to PTSD (appearing in light blue) including:

- Organizational plans, strategies and frameworks;

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis mental health initiatives; and

- Provincial, territorial and municipal initiatives on mental health.

The outermost ring shows the types of groups who are impacted by PTSD and could benefit from these initiatives including: families and support networks, communities, employers, and individuals.

Vision

A Canada where people living with PTSD, those close to them, and those at risk of developing PTSD, are recognized and supported along their path toward healing, resilience, and thriving.

Guiding principles

The following principles are intended to guide the actions outlined in the Framework, as well as other efforts by the Government of Canada to address PTSD.

- Complement current initiatives and leverage partnerships. Improve coordination, collaboration, and linkages across government and among non-governmental organizations, Indigenous organizations and communities, the private sector, provinces and territories, research organizations, communities, practitioners, and those with lived experience.

- Advance compassionate, non-judgemental, strengths-based and trauma-informed approaches. Engage with people who have lived experience of PTSD. Be aware of how stigma, discrimination and racism increase risks and create barriers to treatment. Apply trauma-informed approaches: understand the impact of trauma; create emotionally, culturally, and physically safe environments; foster opportunities for choice, control and collaboration; provide a strengths-based approach to support coping and resilience.

- Base initiatives on evidence of what works or shows promise of working. Recognize the importance of research in generating evidence and knowledge about PTSD. Ensure high-quality information is available, and apply research results to new and existing interventions, treatment, policies, programs, and training across Canada.

- Understand and respond to equity, diversity and inclusion. Ensure that approaches to education, treatment, and reintegration into society and the workplace are adaptable and individualized to occupational settings and realities. Consider culture, including Indigenous cultures, community, sex, gender, and other identity factors, such as race and ethnicity. Apply culturally safe approaches that ensure people can draw strength from their identity, culture, spirituality, and community in an environment that is free from racism and discrimination.

- Apply a public health approach. PTSD is a public health issue. Focus on the population or community and emphasize protective factors such as mental wellness, social cohesion, culturally appropriate and safe programs and services (particularly at the community level) to build safe and healthy environments, resilience, and coping skills.

Priority areas

The Federal Framework on PTSD Act outlines three priority areas to be addressed in the Framework. These areas formed the basis of consultations with partners and stakeholders and were discussed in depth during the National Conference on PTSD.

Based on consultations, an additional priority area was added to focus on strengthening collaboration and linkages among partners and stakeholders.

This section provides an overview of these priority areas and their drivers, considerations, and the federal actions needed to advance them.

Priority Area 1: Improved tracking of the rate of PTSD and its associated economic and social costs

Data on PTSD in Canada is limited. To better inform policies and programs and to improve our understanding of PTSD and its risk factors, there is a need for high-quality, ongoing, and timely data collection, surveillance, and research, as well as insights from individuals with lived experience. Nationally representative data can identify how many Canadians are living with PTSD and the associated risk factors. Routine collection of data can also measure trends over time, and inform policy and program interventions. A variety of PTSD data collection tools are available but the approaches differ and this process is further hampered because the diagnosis of PTSD is complex, and health care providers may not always recognize or properly assess symptoms. In addition, many individuals do not realize they may have PTSD or seek care.

The Act calls for improved tracking of the incidence (the number of new cases of PTSD over a period of time); however, stakeholders, researchers, and policy-makers have recommended that first and foremost, we need an understanding of the prevalence of PTSD (the number of new and existing cases).

Research and data collection on certain sub-populations is taking place, but further effort should focus on Canadian population-level data. Population-level data establishes a prevalence estimate for the general population that serves as a point of comparison for estimates in sub-populations, including those at increased risk of PTSD.

The Act also calls for improved tracking of the associated economic and social costs of PTSD so we can fully understand impacts on individuals living with PTSD, their families, and their communities. These costs can include those related to lost wages, treatment, lost productivity, substance-related harms and/or mental health conditions, homelessness, etc. In order to generate accurate estimates of economic and social costs, we first need a clearer picture of PTSD prevalence in Canada.

Advancements in data collection, insights into existing data-related initiatives, and a deeper understanding of the social and economic costs of PTSD will provide a more complete picture of PTSD in Canada and therein better inform the development of policies, tools, and interventions.

Data on PTSD in Canada is limited and requires updating.

Recognizing the importance of data in understanding PTSD and its impacts, and in informing policies and programs, the Government of Canada will:

- Explore strategies to support national surveillance activities to measure the rate of PTSD and its associated costs and examine the feasibility of using health administrative data and enhanced data linkages to capture and report on PTSD. This work will be led by PHAC in collaboration with other partners and stakeholders.

- Continue supporting data collection to better understand PTSD and related mental health conditions, through ongoing investments and initiatives.

Priority Area 2: Promotion of guidelines and sharing of best practices related to the diagnosis, treatment and management of PTSD

Diagnosing, treating, and managing PTSD is complex. What leads to PTSD in one person may be completely different for another person. People who experience PTSD symptoms may experience other concurrent mental health conditions (e.g., anxiety disorders or substance use disorders), which can hamper recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. Other factors such as individual differences, personal preferences, health provider expertise, resource availability, and the ability to access resources and services may also affect recognition, diagnosis, and treatment.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to treat and manage PTSD. Treatment plans need to be individualized based on a person's clinical presentation and personal experience, and should recognize cultural, occupational, sexual and/or gender-based differences. Relevant social determinants of health, trauma-informed care, and reintegration practices must also be at the centre of any treatment plan to ensure physical, cultural and emotional safety.

A number of clinical practice guidelines provide practical, evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment, and management of PTSD. (See text box.) Guidelines require regular updating as research evolves, which require time and specific expertise. The development, review, and updating of clinical practice guidelines is the responsibility of guideline groups, health authorities or health care providers, along with their associations, accreditors, and regulators.

Examples of Clinical Practice Guidelines on PTSD

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS): PTSD Prevention and Treatment Guidelines: Methodology and Recommendations (March, 2019; US)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): Post-traumatic stress disorder – NICE guideline (December, 2018; UK)

- US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (VA/DoD): Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of PTSD and Acute Stress Disorder (2017; US)

- American Psychological Association (APA): Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD (February, 2017; US)

- Anxiety Disorders Association of Canada: Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders (2014; Canada)"

Guidance and best practices also exist to guide service delivery and models of care for specific populations, but gaps remain, and awareness of these tools is sometimes lacking.

There are also emerging and innovative interventions, such as peer support programs, meditation, internet-based therapies, couples-based trauma treatment, and land-based activities, which provide options that may help in the healing process based on individual needs and pace of recovery. Current dialogue on emerging treatments also includes the possible use of cannabis to manage symptoms of PTSD. For Indigenous Peoples, traditional ceremonial practices enacted in cultural settings can promote healing and wellness. Emerging and innovative interventions may not be included in clinical practice guidelines and are currently considered as adjuncts to first-line evidence-based treatments. Additional and systematic research into emerging and innovative interventions is required to build the evidence base and to ensure their safety, efficacy, and effectiveness.

With more research, we can better determine which policies, programs, and treatments will make the most difference for the mental wellness and resilience of a greater number of Canadians impacted by PTSD.

Knowledge transfer and the sharing of best practices around innovative interventions should be undertaken in a timely way to benefit those living with PTSD and their support networks.

Evidence-based guidelines and best practices are essential to ensure the best care and support of those affected by PTSD.

Recognizing that many resources already exist, but awareness of these tools is sometimes lacking, and recognizing that research is essential in the advancement of guidance development, the Government of Canada will:

- Through PHAC, work with partners and engage experts to compile existing guidance on PTSD, and identify where guidance gaps may exist.

- Support research, including applied research, through existing investments, to bridge PTSD-related information gaps, inform effective guidance for health care providers and advance evidence-based decision making for policy and program makers across all levels of government and key partners and stakeholder organizations.

Priority Area 3: Creation and distribution of educational materials related to PTSD to increase national awareness and enhance diagnosis, treatment and management

Canadian health care providers are often the first line of contact for people experiencing symptoms of PTSD. Health care providers play an important and influential role in helping those affected find appropriate treatments and supports. To be effective, health care providers need to be well informed and knowledgeable about PTSD and how it impacts different populations. Educational tools and resources exist, but there is limited understanding of the quality and availability of tools and resources for health care providers.

The Act specifically identified the need for educational materials for "public health care providers"; however, partners and stakeholders also stressed the need for tools and resources for individuals experiencing symptoms of PTSD, their support networks, and for employers and workplaces.

Individuals experiencing symptoms of PTSD need tools and resources that are accessible, clear, concise, and that encourage them to seek help. There is no single mechanism to share these materials–instead, a breadth of educational tools and resources are available across Canada in a variety of formats. For example, general information on the signs, symptoms, causes, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of PTSD can be found on non-governmental organization (NGO) websites, including the Canadian Mental Health Association, the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, and the Canadian Psychological Association.

The PTSD Coach Canada mobile app provided by VAC is available to people who may be seeking additional information and resources on PTSD. It features information and self-help tools based on research. The app, which is available to all Canadians, can be used as an education and symptom management tool, prior to, or as part of in-person care provided by a health care provider.

Family members and support networks of people experiencing PTSD, especially spouses, are often the first to recognize early warning signs and encourage their loved one to seek support. Families and support networks need specialized tools and resources that can help them recognize symptoms and cope with the impact of PTSD on their own lives.

This is especially true for children of people living with PTSD, who may be affected in multiple ways and may not understand what is happening to their parent or family member. Symptoms of PTSD, and the stress of coping with them, can impact a parent's ability to meet their child(ren)'s basic physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual needs, and their need for social and intellectual development. Educational materials for families and support networks need to emphasize coping strategies and point to available resources for support.

VAC publications on PTSD and the Family and the "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and the Family for Parents with Young Children" PDF publication are good examples.

Employers and workplaces have a crucial role in raising awareness about PTSD, preventing psychological injury, promoting psychological wellbeing and providing support to employees with PTSD. Workplace educational tools exist, such as the Road to Mental Readiness and The Working Mind programs. This content has already been adapted for some workplaces, but given diverse cultures and contexts, may need to be further adapted for applicability to specific audiences.

Trauma-informed policies in the workplace also promote resilience, encourage employees to seek early intervention, and reduce stigma toward mental health issues in the workplace.

Providing high quality, compassionate, action-oriented information on PTSD can empower people with PTSD, their family and support networks, and employers/workplaces to recognize the symptoms and impacts of PTSD, and encourage them to seek support and treatment.

Recognizing the importance of education in raising awareness, reducing stigma, and enhancing PTSD diagnosis, treatment, and management, the Government of Canada will:

- Through PHAC, work with partners and engage with health care providers to identify current PTSD educational materials, understand information and educational gaps, and seek advice on best practices for their dissemination, adaptation, and uptake.

Priority Area 4: Strengthened collaboration and linkages among partners and stakeholders

A number of PTSD-related initiatives are currently underway in Canada, including federal initiatives to support high-risk populations, such as Supporting Canada's Public Safety Personnel: An Action Plan on Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries, and the recently created Centre of Excellence on PTSD and Related Mental Health Conditions, funded by VAC.

A concerted and coordinated effort is needed to ensure awareness of new and existing PTSD initiatives and to engage partners and stakeholders, including people with lived experience. Working collectively allows for meaningful linkages and informed action across the Government of Canada, as well as with provinces and territories, Indigenous governments and organizations and communities, non-governmental organizations, researchers, practitioners, occupational communities and individuals. Connecting our efforts helps prevent duplication and ensures that we build on new approaches or resources as they are developed.

Strengthening connections and working collaboratively also involves an exploration of terminology. Language is important, not only in establishing a common understanding, but also in reducing stigma. There are many terms that are used interchangeably to capture the range of symptoms and health concerns associated with exposure to trauma and a common language can help build consistency among stakeholders and partners.

The Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT), in collaboration with a number of experts, has developed a Glossary outlining definitions related to PTSD and trauma. A version of the Glossary was disseminated at the National Conference on PTSD to ensure a common understanding among participants as they provided their insights and perspectives. Recognizing that language changes over time, the Glossary is intended to be a living document that will be updated regularly to reflect contemporary consensus on language. The most current version of the Glossary is included in Appendix D.

Collaboration is essential to minimize duplication and maximize the impact of our efforts to address PTSD.

In recognition of the complexity of PTSD, the diversity of those affected, the many partners and stakeholders involved in managing PTSD and the wide range of initiatives underway, the Government of Canada will:

- Work via PHAC with partners and stakeholders to identify the best mechanism(s) for increased collaboration among key federal departments, partners, and stakeholders, as well as for ongoing sharing of information, including uptake of common and culturally appropriate terminology, definitions, and safe language related to PTSD and trauma.

Part III: Moving forward

PTSD Secretariat

The PTSD Secretariat was established within PHAC to lead the implementation of the Federal Framework on PTSD Act. Since that time, the Secretariat has worked with partners and stakeholders together to inform the development of the Framework in a variety of ways, including the National Conference on PTSD in April 2019.

Given the numerous players, initiatives, and far-reaching impacts of PTSD in Canada, as well as the need for coordination of actions outlined in this Framework, the PTSD Secretariat will continue to exist at PHAC. The PTSD Secretariat will provide leadership and bring partners and stakeholders together to continue to foster connections, as well as to identify existing and possible collaborations to further support the progressing and evolving efforts to address PTSD.

The PTSD Secretariat will work with partners and stakeholders to leverage existing mechanisms, resources, and efforts to avoid duplication.

Reporting to Parliament

As mandated by the Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Act, PHAC will complete a review of the effectiveness of the Framework five years after the publication of the Framework. This review, which must be laid before each house of Parliament, will include a progress update on the priority areas and actions outlined in the Framework, and highlight any new initiatives and their results.

Conclusion

PTSD has a long history of being under-recognized, misunderstood and misdiagnosed. PTSD affects a significant number of Canadians; nevertheless, getting on a path to recovery can be extremely complex for these reasons. People living with PTSD are certainly impacted by the disorder, but so are their loved ones, colleagues, and support networks, all of whom also need to be supported as part of managing the disorder.

Achieving the vision set out in the Framework will require collaboration from multiple partners and stakeholders, including people with lived experience, their families and support networks, employers, researchers, health care providers, community organizations, and all levels of government. We encourage all partners and stakeholders to build on the vision and guiding principles of the Framework to advance initiatives in the area of PTSD.

The Framework is intended to encourage continuous open dialogue. The actions identified herein will undoubtedly continue to evolve as we learn more about PTSD through ongoing efforts across the Government of Canada and by the many partners and stakeholders.

Part IV: Appendices

Appendix A – Federal Framework on PTSD Act and Observations from the Senate Committee

Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Act

S.C. 2018, c. 13

Assented to 2018-06-21

An Act respecting a federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder

Preamble

Whereas post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition that is characterized by persistent emotional distress occurring as a result of physical injury or severe psychological shock and typically involves disturbance of sleep and constant vivid recall of the traumatic experience, with dulled responses to others and to the outside world;

Whereas there is a clear need for persons who have served as first responders, firefighters, military personnel, corrections officers and members of the RCMP to receive direct and timely access to PTSD support;

Whereas, while not-for-profit organizations and governmental resources to address mental health issues, including PTSD, exist at the federal and provincial levels, there is no coordinated national strategy that would expand the scope of support to ensure long-term solutions;

And whereas many Canadians, in particular persons who have served as first responders, firefighters, military personnel, corrections officers and members of the RCMP, suffer from PTSD and would greatly benefit from the development and implementation of a federal framework on PTSD that provides for best practices, research, education, awareness and treatment;

Now, therefore, Her Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts as follows:

Short Title

1 This Act may be cited as the Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Act.

Interpretation

Definitions

2 The following definitions apply in this Act.

Agency means the Public Health Agency of Canada. (Agence)

federal framework means a framework to address the challenges of recognizing the symptoms and providing timely diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. (cadre fédéral)

Minister means the Minister of Health. (ministre)

Federal Framework on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Conference

3 The Minister must, no later than 12 months after the day on which this Act comes into force, convene a conference with the Minister of National Defence, the Minister of Veterans Affairs, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, provincial and territorial government representatives responsible for health and stakeholders, including representatives of the medical community and patients' groups, for the purpose of developing a comprehensive federal framework in relation to

- improved tracking of the incidence rate and associated economic and social costs of post-traumatic stress disorder;

- the establishment of guidelines regarding

- the diagnosis, treatment and management of post-traumatic stress disorder, and

- the sharing throughout Canada of best practices related to the treatment and management of post-traumatic stress disorder; and

- the creation and distribution of standardized educational materials related to post-traumatic stress disorder, for use by Canadian public health care providers, that are designed to increase national awareness about the disorder and enhance its diagnosis, treatment and management.

Preparation and tabling of report

- 4 (1) The Minister must prepare a report setting out the federal framework and cause a copy of the report to be laid before each House of Parliament within 18 months after the day on which this Act comes into force.

Publication of report

(2) The Minister must publish the report on the Agency's website within 30 days after the day on which it is laid before a House of Parliament.

Review and Report

Review

5 The Agency must

- complete a review of the effectiveness of the federal framework no later than five years after the day on which the report referred to in section 4 is published; and

- cause a report on its findings to be laid before each House of Parliament within the next 10 sitting days after the review is completed.

Monday, June 11, 2018

The Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence has the honour to present its

Eighteenth Report

Your committee, to which was referred Bill C-211, An Act respecting a federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder, has, in obedience to the order of reference of Thursday, May 3, 2018, examined the said bill and now reports the same without amendment but with certain observations, which are appended to this report.

Respectfully submitted,

GWEN BONIFACE

Chair

Observations

to the Eighteenth Report Report of the Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence (Bill C-211)

- The bill's sponsor, Todd Doherty, MP (Cariboo—Prince George), told your committee that the exclusion of various occupations from the preamble to the bill was an accidental oversight and that he had intended to be as inclusive as possible. Your committee shares Mr. Doherty's view that the conference and federal framework should be as inclusive as possible.

- Your committee would like to ensure that health care providers and individuals in other high-stress occupations be asked to participate in developing the federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder that is proposed in the bill. Your committee wishes to emphasize that the words "in particular" in the fourth paragraph of the bill's preamble indicate that the conference and the federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder should include not only first responders, firefighters, military personnel, corrections officers and members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but also a wide range of occupations whose members are affected by post-traumatic stress and related problems, including nurses, psychologists and other health care providers and first responders.

- Your committee shares the concern expressed by officials from the Canadian Psychological Association regarding clause 3(b)(i) that addresses the development of guidelines. This clause states that the conference aiming to establish a federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder focus, among other topics, on "the establishment of guidelines regarding the diagnosis, treatment and management of post-traumatic stress disorder." Representatives of the Canadian Psychological Association stated that developing guidelines in this regard is the responsibility of health professionals and their associations, accreditors and regulators, not the government. Your committee therefore suggests that the conference on the federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder promote the establishment and dissemination of guidelines, rather than developing them as such, as recommended by the Canadian Psychological Association.

- Your committee would like to ensure that the full range of mental health conditions obtained from high-stress occupations are considered in the development of the federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder that is proposed in the bill. Your committee therefore advises that the conference on the federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder consider the use of the term "operational stress injury." This term includes post-traumatic stress disorder, but also includes conditions like occupation-linked depression, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorder and the full range of substance disorders that people may face as a result of being in a high-stress work environment.

- Your committee is concerned that the current wording of Bill C-211 could imply that the national framework on post-traumatic stress disorder should only focus on cases that manifest as a direct consequence of the demands of their occupation. However, many cases of work-related cases of post-traumatic stress disorder are directly linked to cases of sexual misconduct and harassment. Your committee therefore suggests that the conference on the federal framework on post-traumatic stress disorder include these cases in its development of the national framework.

Appendix B – Other populations affected by PTSD

Survivors of physical, sexual and/or psychological violence