An evaluation guide to support community-based interventions to prevent substance-related harms in youth: Based on the implementation of the Icelandic Prevention Model in Lanark County, Canada

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.42 MB, 50 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: June 2022

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Purpose

- 1. Prevention of substance-related harms and mental health promotion among youth

- 2. Evaluation of substance use related prevention initiatives

- Conclusion

- 3. Appendix: Practice profile guides based on the Five Guiding Principles and Ten Core Steps of the Icelandic Prevention Model

- 4. Toolbox

- References

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Tanya Halsall, who developed a report and provided content for this guide. In addition, we would like to thank Open Doors for Lanark Children and Youth and the Royal's Institute of Mental Health Research affiliated with the University of Ottawa, for supporting this work.

List of Abbreviations

- ICSRA

- Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis

- IPM

- Icelandic Prevention Model

- PYLC

- Planet Youth Lanark County

Introduction

The Public Health Agency of Canada prepared this guide to provide communities with practical information and tools to measure progress and evaluate initiatives designed to prevent substance-related harms among youth through collaborative community-wide strategies. This guide focuses on a specific model, the Icelandic Prevention Model (IPM) that is being implemented in Lanark County, Ontario, Canada. However, this guide can also support other communities to help evaluate the IPM or a similar approach.

This guide contains information and resources that are useful for communities that are considering taking an upstream prevention approach to reduce substance use behaviours by addressing risk and protective factors in youth. In addition, it is also helpful for communities that have already begun to invest in prevention of substance-related harms and would like to refine their strategy.

Purpose

We developed this guide with three main purposes:

- To inform strategies that supports positive youth development through holistic approaches.

- To provide information on how to use evaluation to measure progress.

- To outline the range of indicators that are useful to examine changes created by the initiative and to measure implementation of the overall strategy.

Who this guide is for

The primary audience for this guide is stakeholders and partners that work directly in preventing substance-related harms in youth. This includes:

- school communities

- parents and caregivers

- community organizations

- public health organizations

- social scientists and researchers

- community professional providers who work in areas such as:

- faith

- medicine

- mental health

- law enforcement

- sports and recreation

Along with youth, these groups are essential to planning, setting up and continuing efforts to prevent substance-related harms.

The secondary audience for this guide is wider, and includes stakeholders who work in direct or indirect ways to prevent substance-related harms among youth, including government officials.

In this guide

This guide contains four sections.

Section 1: Prevention of substance-related harms and mental health promotion among youth

- An overview of the Icelandic Prevention Model (IPM)

- How IPM and Planet Youth is currently being implemented in Lanark County

- How to get started in your own community

- Socioecological approaches which focus on changing the community environment to reduce the risk of youth becoming involved in harmful substance use behaviors

Section 2: Evaluation of substance use-related prevention initiatives

- General purpose and benefits of conducting an evaluation

- Methods and tools to support evaluation

- How to evaluate the IPM

- Current frameworks and indicator measurement strategies

- Risk and protective factors that influence youth involvement in substance use behaviors

- A practice profile tool that is tailored to monitor the implementation of the IPM and can be adapted to support communities to evaluate similar substance use-related prevention strategies

Section 3: Appendix: Practice profile guides based on the Five Guiding Principles and Ten Core Steps of the Icelandic Prevention Model

Section 4: Toolbox

- A list of online resources for more information on the concepts, tools and methods described in this document

- General definitions of concepts used in this guide

1. Prevention of substance-related harms and mental health promotion among youth

Increased concerns over substance use among youth have renewed interest for community-based prevention efforts to reduce associated risks and harms.Footnote 1 Adolescence is a critical stage because certain factors, such as peers and the media, can negatively influence healthy development that lead to life-long implications.Footnote 2 Adolescents are more likely than adults to engage in risk-taking behaviors, based on the stage of their brain development.Footnote 3

Youth are likely to experiment with substances, for example drugs, cannabis, and alcohol for a variety of reasons. These include the need for social inclusion, influence from pop culture and media, poor mental health and challenges coping with life stresses, or simply because they enjoy it. Some youth may experience no long-term effects or negative outcomes depending on the type of substance and frequency of use. Others may develop dependency or addiction that result in persistent, negative long-term health and social effects. Every individual is unique with their own needs to develop the skills necessary to navigate life, therefore it is important to ensure youth have access to supports that will meet them where they are at, at that point in life. Community-driven prevention programs designed for youth have been shown to reduce and, in some cases, delay substance use harms among youth, which has the potential for continued benefits into adulthood.Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6

A. The Icelandic Prevention Model

The Icelandic Prevention Model (IPM) has received international acclaim and attention for its collaborative approach to prevent substance use harms among youth. Developed by the Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis (ICSRA), it applies a community-driven approach to influence risk and protective factors associated with substance use. Studies of the IPM in Iceland show a population-level decline in youth substance use. Over a ten-year period, the studies show a 46% reduction in the number of youth getting drunk in the past 30 days and a 60% decline in the use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis.Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9 Since it originated, the ICSRA has expanded their work to over 30 countries worldwide under the organization name of "Planet Youth".

The IPM takes a program approach that considers the broader social surroundings affecting youth such as the home, school and peer environments, rather than focusing on changing individual behaviour. This is based in the concept that social environments need to be changed in order to influence youth behaviour. The approach aims to modify the social surroundings so that it is easier to learn healthy behaviours.

Highlight on the first Canadian community to implement the IPM: Lanark County

The first community to adopt the IPM in Canada was Lanark County, Ontario. Planet Youth Lanark County (PYLC) originated in 2017 when a community interest group in Lanark County mobilized to respond to concerns about risks associated with opioid use in the community. They identified the IPM as a possible approach to support the objective of protecting their children and youth from substance related harms. Eventually, this led to the formation of the PYLC Steering Committee in 2018 and a formal partnership with the ICSRA to support the first implementation of the IPM in Canada.

The PYLC Steering Committee has engaged key stakeholders to support the implementation of the IPM model in their community, including:

- United Way East Ontario

- Upper Canada District School Board

- Open Doors for Lanark Children & Youth

- Leeds, Grenville & Lanark District Health Unit

- The Royal's Institute of Mental Health Research

- Catholic District School Board of Eastern Ontario

In addition to being the first Canadian community to adopt the IPM, PYLC has also integrated two innovations to the traditional IPM model.

- Engaging community youth as a key stakeholder to co-create the community strategy.

- Examining positive mental health as a major outcome measure alongside youth substance use behaviour.

B. Features of the Icelandic Prevention Model approach

Survey

A key feature of the IPM is the administration of a population-wide survey that regularly captures youth perceptions of risk and protective factors.Footnote 10 Surveys are distributed to students in early secondary grade levels (ages 14-16) using a passive consent process whereby parents or caregivers must opt-out of having their children complete the survey. This process allows for high participation rates of typically over 80% of the targeted student population.

Survey items capture information on areas including:

- substance use behaviours

- mental health and wellbeing

- risk and protective factors in relation to individual, family, peer, school and community characteristics

Survey findings assist the community to identify issues and potential solutions. The data also supports development of a tailored prevention strategy that leverages existing community structures, to ensure that the prevention strategies are sustainable.

Community Based Steering Committee

Another important feature of the IPM approach includes the establishment of a community-based steering committee that can assume responsibility for implementation at the local level.

Responsibilities of this steering committee include:

- establishing funding supports

- coordinating community engagement

- coordinating partners to collect survey data

Community involvement in all stages of the IPM approach is necessary in order to ensure the success of prevention strategies. Members of the steering committee should reflect the community it intends to serve and be representative of a variety of community stakeholders, including:

- youth

- teachers

- elected officials

- parents and caregivers

- social scientists and researchers

- community professional providers (working in areas such as public health, medicine, mental health, sports and recreation, faith, and law enforcement)

The Five Guiding Principles of the Icelandic Prevention Model

The IPM applies five guiding principles and ten core steps to create sustainable community change.Footnote 7Footnote 10Footnote 11 These principles and steps outline the procedures that must be followed in order to maintain the integrity of the approach and to achieve maximum community benefits.

The Five Guiding Principles of the Icelandic Prevention ModelFootnote 11

- Guiding Principle 1: Apply a primary prevention approach

- Guiding Principle 2: Engage community action and public school involvement

- Guiding Principle 3: Engage stakeholders to make decisions using high-quality data

- Guiding Principle 4: Integrate researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and community members

- Guiding Principle 5: Align the scope of the solution with the nature of the problem

The Ten Core Steps of the Icelandic Prevention ModelFootnote 10

- Step 1: Local coalition identification, development, and capacity building

- Step 2: Local funding identification, development, and capacity building

- Step 3: Engage stakeholders and plan data collection

- Step 4: Data collection and processing; Evidence-based needs assessment of risk and protective factors

- Step 5: Targeted outreach based on needs assessment findings

- Step 6: Rapid and tailored dissemination of findings

- Step 7: Community-driven goal setting and strategy selection

- Step 8: Identification of policies and existing mechanisms to achieve outcomes, implement strategies

- Step 9: Immerse local children and youth to altered primary prevention environments, activities and messages

- Step 10: Repeat steps 1-9 annually

Typically, communities collaborate with ICSRA in order to implement the full IPM approach. However, it may not be feasible for some communities. In these cases, it is helpful to learn about similar frameworks and approaches to help inform a grassroots strategy that can use the Planet Youth model within their own context. The following sections will briefly review the frameworks applied within the IPM approach to help communities understand the underlying principles of this prevention strategy for youth.

C. Positive youth development framework and socioecological approaches

Positive youth development framework

Positive youth development is a framework that focuses on building individual strengths among youth that support successful navigation of life challenges.Footnote 12Footnote 13 The key features of the framework are:

- Youth are encouraged to establish and achieve their own goals.

- Youth development is assessed holistically with their environment.

- Youth are engaged to develop and improve the necessary resources, skills and competencies needed to make or influence their own decisions.

- Enabling environments should encourage and recognize youth in a manner that promotes their social and emotional competence to successfully navigate their lives.Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16

Socioecological Approaches

Socioecological model of health

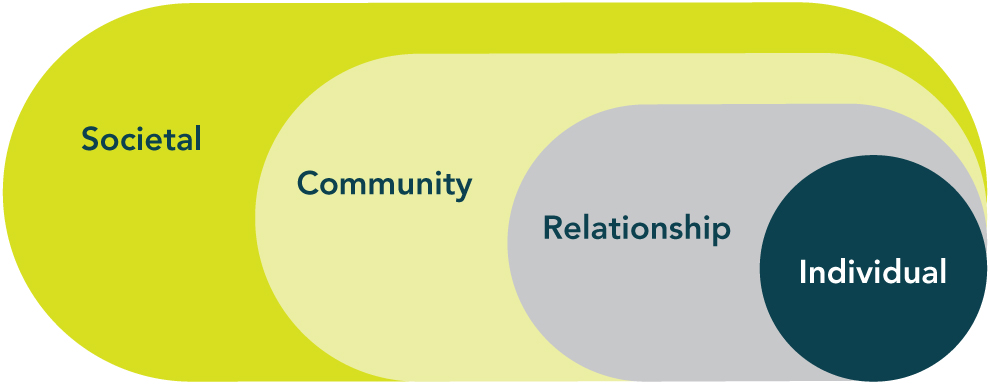

The socioecological model of health (Figure 1) is an established framework that describes the various factors that contribute to complex social and public health challenges, as well as appropriate and comprehensive strategies to promote population health.Footnote 17 The model considers the interplay between individual, relationship, community and societal level factors.

Figure 1. The socioecological model of healthFootnote 18

Figure 1 - Text Description

Figure 1 depicts a diagram of four nested circles that shows the four levels of the socioecological model of health: individual, relationship, community and societal levels.

Levels of the socioecological model

Individual level: the biological and innate personal characteristics of an individual that influence behaviours.

Relationship level: the interpersonal familial and social relationships (such as mentors and peers) that can influence individual behaviours.

Community level: the settings and their characteristics where social relationships can occur and influence individual behaviours; may be a formal (for example, schools and workplaces) or informal (for example, neighbourhoods) setting.

Societal level: the environment where broader societal factors (such as social norms and public policies) may influence behaviour and create or maintain socioeconomic inequities between groups.

The socioecological model of health has three core principles:Footnote 19

- There are multiple levels that influence risk and health behaviours.

- Interaction occurs between all these levels.

- Interventions to improve risk and health behaviours should account for these numerous levels of influence.

This model demonstrates that the risk and protective factors are not dependent on one level. Rather, they dynamically influence each other across various levels. The varying levels of influence are not intended to represent alternative courses of intervention (for example, focusing on individual factors instead of societal factors). Instead, the levels should be understood as dynamic and complementary.Footnote 20

Many risk and protective factors related to substance use reflect some of the well-recognized root causes of health inequalities, such as income and social status, social support networks, early child development and education.Footnote 21 Identifying the diverse risk and protective factors associated with substance use, and understanding how they can lead to increased risks, are important steps in developing effective prevention efforts.

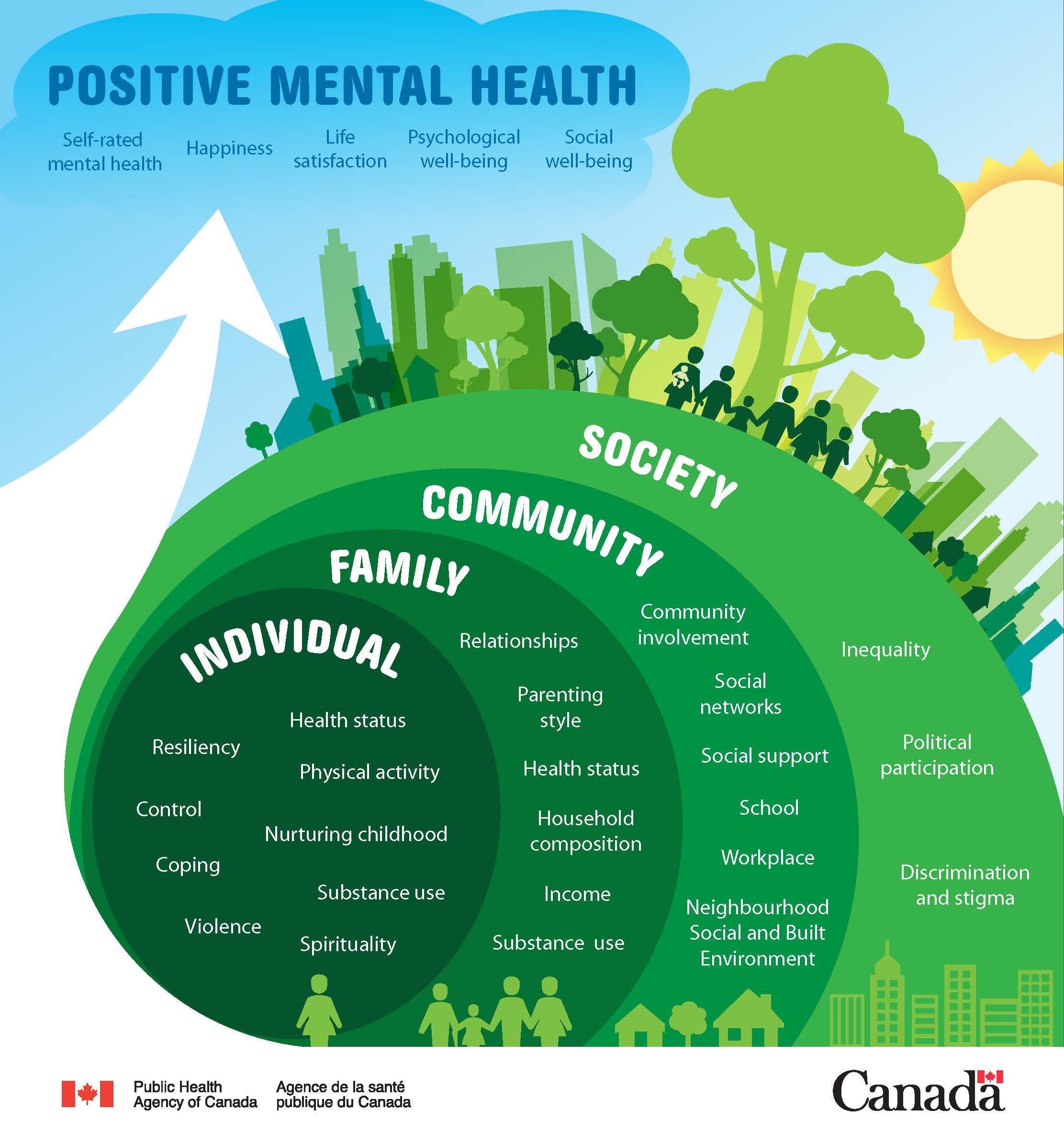

This model asserts that individuals' development and behaviours are profoundly shaped by influences that extend far beyond their personal traits and immediate situation. For example, influences include the people and places an individual interacts with on a daily basis. Characteristics of the broader environment (such as those relating to public policy, culture and prevailing attitudes) can affect individual outcomes and behaviours both directly and indirectly, which are also influenced by other people or settings.Footnote 22 Keeping in mind this socioecological perspective, an individual trait or experience (such as mental illness and early life adversity) does not necessarily lead to substance use with increased harms. As shown in Figure 2, protective factors such as an individual's resiliency, their relationships, and their community and societal environment can act as buffers against exposures to risks.

Figure 2. Public Health Agency of Canada's Positive mental health conceptual framework for surveillanceFootnote 23

Figure 2 - Text Description

Figure 2 depicts the conceptual framework that was developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada in consultation with Mental Health Commission of Canada experts. The framework integrates conceptual elements that are important for describing positive mental health in the population.

The selected indicators are presented in the form of a socioecological model representing the 4 domains (individual, family, community and society) in which these risk and protective factors exist. Each domain influences the positive mental health of the population and is considered a potential entry point for interventions that promote mental health.

Time is another concept emphasized within socioecological approaches that has important implications for the IPM. The influence of risk and protective factors on youth vary depending on the amount of time youth are exposed to those factors within a particular context and how youth are using their time within various contexts. Unstructured time with peers can be a risk factor for substance use among youth. However, constructive use of time can be a protective factor (for example, time spent in creative pursuits, sports or extra-curricular activities).Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26 The concept of time highlights the importance of considering individuals over their whole lifespan and supports reflection on how transitions and environmental shifts influence individuals as they age.

In Section 2, we will elaborate on how to develop indicators to measure risk and protective factors to support evaluation of substance use related prevention efforts, both through the IPM approach as well as through the application of other current frameworks and tools.

2. Evaluation of substance use related prevention initiatives

In order to support an effective evaluation of efforts to prevent substance-related harms, it is important to be familiar with the process of evaluation and current research and methods with respect to measurement.

In this section, we review:

- Important concepts of program evaluation

- Recent developments in the field that are related to the IPM approach

- Indicators that inform outcome evaluation in the IPM

A. Program evaluation

Program evaluation is a systematic process of gathering information about a program or initiative in order to better understand how it is functioning, determine if it is effective, and how it can be improved.Footnote 27Footnote 28

Program evaluations are useful to:

- identify which aspects of a program are working or need improvement

- understand whether the program is worthwhile, or has the resources needed to make the intended difference

- enhance confidence in the program and promote the work with community members, funders, and other organizations and services

Two Types of Evaluation: Outcome and Process

There are two major categories of evaluation that should be applied to any community-based prevention strategy: outcome evaluation and process evaluation.

Outcome evaluations examine what changes are being created by the program with respect to the overall goal.Footnote 29Footnote 30 As previously mentioned, the population-wide survey for youth is an integral component of the IPM. It serves as a built-in measure to support outcome evaluation as it is typically administered annually. This survey allows communities to understand the level of substance use among youth over time, as well as the influence of certain key variables on youths' perceptions.

Process evaluations collect information about the range of program activities (such as costs, timelines, staff expertise, participant characteristics and prevention activities) implemented to support the prevention strategy and how they are being accomplished.Footnote 31

Both outcome and process evaluation are instrumental to the success of the IPM because it allows communities to regularly evaluate and adapt their practices to ensure their prevention strategies remain effective and relevant to the targeted youth. If a partnership with ICSRA is not possible, communities need to determine how best to carry out these evaluations for their purposes in a way that optimizes their resources and capacities. Effective evaluation of prevention strategies require a working knowledge of current research, methods, and tools with respect to measurement. The following section of this guide will provide more information and tools to assist communities in evaluating the process and outcomes of their prevention strategies.

B. Indicators

Prior to implementing any prevention strategy, it is helpful to identify indicators that can be used to evaluate its process and outcomes. An indicator is a specific, observable and measurable characteristic or change that can be used to track progress toward the objectives (outcome indicators) or to monitor performance in completing program activities (process indicators).

Indicators should be defined using specific criteria rather than general terms and there should be a feasible way to measure them. For example, "a decrease in substance use" is harder to measure than "a percent decrease in number of alcohol drinks consumed over the past week". Likewise, "improved mental health" is harder to measure than "higher perception of self-confidence".

A helpful approach for developing indicators is to follow the SMART criteria:

- Specific: Does the indicator clearly describe what is intended to be measured?

- Measurable: Can the indicator be measured in a practical and consistent way?

- Attainable: Is it straightforward and achievable to collect data for the indicator?

- Realistic: Is it possible to measure this indicator, with the available resources and timeframe?

- Time-bound: Does the indicator include a specific timeframe?

Indicators can be either quantitative or qualitative, depending on what you are measuring.

Quantitative indicators are defined by a quantity, such as number, index, ratio or percentage.

Qualitative indicators depict a level of progress or change of a status. This type of indicator gives a sense of direction to the information collected, and are useful in determining how quickly a process or change is occurring. For example, they are used to measure a judgment or perception about an issue that cannot be captured using a numerical value.

Both quantitative and qualitative indicators can be captured using survey questions or through program monitoring, like attendance sheets, number of meetings and activities held, as well as web-based analytics.

C. Relevant indicators for substance use-related prevention initiatives

The population-wide youth survey is the main method used within the IPM approach to collect information on the outcome indicators for prevention strategies. The survey typically includes a number of questions that help monitor change in substance use behaviours, positive mental health, as well as the risk and protective factors that can influence these outcomes. Within the IPM approach, survey implementation is highly supported by the ICSRA. The IPM approach captures several categories of indicators that include important risk and protective factors associated with the likelihood of youth using substances.Footnote 32

General Types of Indicators Captured by the IPM Approach

- Demographics (for example, age and gender)

- Individual characteristics (for example, school attitudes and ability to self-regulate)

- Family context (for example, family income and parental relationships)

- School context (for example, school climate and funding)

- Peers context (for example, peer substance use behaviours and peer delinquency)

- Neighbourhood or community context (for example, levels of crime and access to recreation facilities)

- Time use (for example, sport participation and screen time)

- Factors related to accessing substances (for example, public policy)

Communities who are not involved in a partnership with the ICSRA may wish to examine other examples of surveys that capture a similar range of indicators, such as the Canadian Index of Child and Youth Wellbeing or the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC), to develop their own survey. The Canadian Index of Child and Youth Wellbeing is a framework designed with children and youth across Canada to capture indicators related with children's rights and well-being.Footnote 33 The HBSC study is an international research initiative that developed indicators based on the holistic perspective of health, similar to the positive youth development framework.Footnote 34 The partnership originated over 20 years ago and since then has expanded to become a large international network with a formalized terms of reference and standardized protocol.

However, some communities may not need to conduct their own surveys. Instead, they may be able to access data captured within school surveys or through national surveillance already being completed.Footnote 35Footnote 36 There are also several notable organizations working to support measurement activities within child and youth development, including the Students Commission of Canada, the COMPASS system research platform, and the Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. A review of current youth surveys being conducted within their community may turn up existing databases that can be leveraged for their purposes of evaluating prevention efforts.

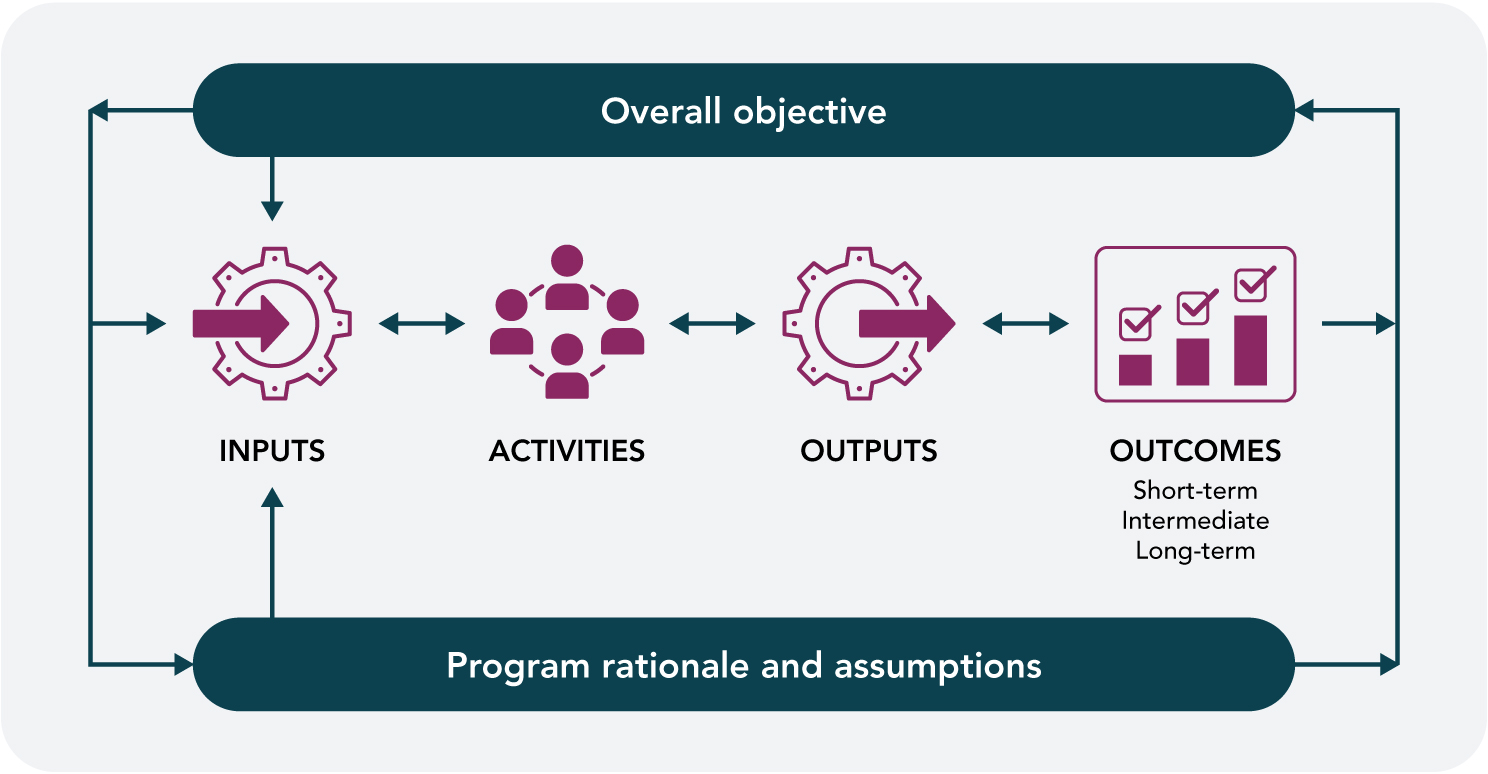

D. Logic models

A logic model is a visual representation of how a program works. It shows the reasoning behind how the program is presumed to create impact. The logic model also shows the important program elements, including the links between program investments, activities and resulting changes they are intended to generate. There are many tools and resources that are available online that can be used to support the development of a logic model (see Section 4 Toolbox for some helpful links).

Generally, logic models display all of the relevant elements of a program. However for practical purposes, only some of these elements will be evaluated. The priority elements for evaluation are typically decided on by determining the priorities of key stakeholders and by program reporting requirements.

Most logic models are simple visual templates that follow a chronological order and contain the following main categories (see Figure 3):

- Overall objective:

- This should align with the overall vision of the program or initiative.

- Often this includes the specified target population, a summary description of the combined program activities and the intended result.

- Program rationale and assumptions:

- This describes the underlying explanation for why the anticipated changes should be expected as a result of accomplishing the outlined activities.

- Activities:

- This category describes the type of work that is planned to carry out the program or initiative.

- Activities represent the processes, events and actions that must be completed to reach the program goals. This section is often included in the main program components.

- Inputs (resources invested):

- This category lists all necessary resources that should be invested in order for the program to function properly.

- This includes human resources, financial investments, professional expertise, specialized technology, administrative supports and office space, among others.

- Outputs:

- Outputs represent the measureable products that will be produced by completing the necessary activities.

- These are created through the program's activities and represent a measure of work being completed.

- Outputs should not be mistaken for a measurement of progress toward program goals. It is possible to accomplish a significant amount of work without achieving program targets.

- Examples of outputs depend on the type of program, but usually include services provided, meetings held, reports published and number of participants who have participated in programming.

- Outcomes (Short-Term, Intermediate and Long-Term outcomes):

- Outcomes describe the anticipated changes that provide evidence of the program making a difference in the community.

- Outcomes should be considered in terms of reasonable timelines for when they are expected to occur.

- They should also be placed within a logic model based on the order in which they are expected to occur.

- Often, outcomes are described using indicators, as discussed above in Section B.

Figure 3. Components of a logic modelFootnote 18

Figure 3 - Text Description

Figure 3 depicts a flow chart showing bi-directional arrows between the components of a logic model: the overall objective, program rationale and assumptions, inputs, activities, outputs and short-term, intermediate, and long-term outcomes.

E. Creating logic models for collaborative community-driven initiatives

Although logic models are useful evaluation tools, they can be challenging to apply to programs in complex environments with multiple organizations and stakeholders, such as strategies that follow the IPM approach. In addition, initial planning of the prevention strategies following the IPM approach may not yet know the practical direction that will be taken to achieve desired objectives. It is only after the first survey collection is completed that community partners may be able to identify shared goals and objectives. In these cases, logic models can be left open-ended until community strategies are identified and logic models can be re-evaluated at a later defined time.

Table 1 shows a hypothetical example of a logic model created for a generic IPM initiative. In this logic model, note that some of the components that can only be specified after the community strategy is chosen. The overall objective of the program is to reduce substance use behaviours in local youth (aged 14-16) through collaborative prevention to enhance youth developmental contexts. The program rationale and assumptions are that the intervention is based on socioecological approaches in which social environments are changed to reduce likelihood of substance use behaviours in youth.

| Inputs (resources that are being invested) | Activities | Outputs (created by the activities) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

F. Using practice profiles to conduct evaluation

Once specific program activities are put into action, process evaluation is needed to ensure the program is delivered as intended and that it achieves the desired outcome. This is possible by collecting information throughout the development and implementation stage that can help examine how program activities affect the overall impact of the program or initiative.Footnote 37

Information that can be collected for process evaluation includes:

- monitoring the progress of proposed timelines

- observing which, and how, activities are being completed

- characteristics of the target population and behaviour outcomes

Since the IPM represents a complex system-level initiative with components that are designed and re-evaluated in a cyclical manner, it is best to apply an evaluation framework that can take into consideration the involvement of multiple community partners.Footnote 38

The National Implementation Research Network developed a variety of tools that help examine complex collaborative efforts such as the IPM. Specifically, the practice profile tool was created to support the translation of innovative interventions into operations in order to support practitioners in carrying out their prescribed work.Footnote 39

Practice profiles have been found helpful to:

- describe complex interventions

- ensure the consistency of interventions when transferring them to new settings

- identify and evaluate the critical components needed within program intervention

- clarify what criteria is necessary in order to meet minimum standards to maintain the integrity of interventions

- allow evaluators to systematically track the extent in which critical components of an initiative are being implemented

Section 3 presents a modified version of the practice profiles to provide communities with a tool to support the evaluation of their prevention strategy based on the five guiding principles and ten core steps of the IPM.Footnote 40Footnote 41 The practice profiles aim to support communities to measure whether their interventions have been implemented as intended and if they achieve desired objectives. Community steering committees can also use these practice profiles to orient the community partners to the overall approach and guide the development of supports and infrastructure for prevention strategies.

The practice profiles include:

- Rationale for the critical component, which describes the importance of this component

- Description of the implementation practice, which outlines the characteristics of:

- Ideal implementation: a practice that has been tested and leads to the best results

- Acceptable variation: a practice which differs from the ideal implementation but still effective

- Unacceptable variation: a practice which is too far from the ideal implementation and may not be effective in delivering the program and its outcomes

- Knowledge, skills, and abilities that would ensure a successful implementation

- Elements of the evaluation, which describes methods to evaluate the implementation of this component

Practice profiles guides should be adapted to meet the needs of the community. While it is recommended that communities follow the process described in these practice profiles as closely as possible, we recognize it is not necessary or practical to collect all of the information described. For example, the information within "Evaluation methods" can be useful to guide the implementation evaluation. However, the specific details of the information collected will depend on the community's desired objectives and programs. The information provided in the practice profiles (Section 3) can be used to guide refinement of program monitoring within a community.

Conclusion

This guide presents evaluation tools and strategies for communities considering programs based on the Icelandic Prevention Model, an established approach for preventing substance-related harms among youth. Through collaborative community-based programs and application of this prevention approach, communities can support positive shifts in social environments that boost protective factors and influence healthy youth behaviours.

3. Appendix: Practice profile guides based on the Five Guiding Principles and Ten Core Steps of the Icelandic Prevention Model

The practice profiles are also available in table format in the PDF version of this guide.

In this section:

- Guiding Principle 1: Apply a primary prevention approach that is designed to enhance the social environment

- Guiding Principle 2: Emphasize community action and embrace public schools as the natural hub of neighborhood and area efforts to support child and adolescent health, learning, and life success

- Guiding Principle 3: Engage and empower community members to make practical decisions using local, high quality, accessible data and diagnostics

- Guiding Principle 4: Integrate researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and community members into a unified team dedicated to solving complex, real-world problems

- Guiding Principle 5: Match the scope of the solution to the scope of the problem, including emphasizing long-term intervention and efforts to marshal adequate community resources

- Core step 1: Local coalition identification, development, and capacity building

- Core step 2: Local funding identification, development, and capacity building

- Core step 3: Pre–data collection planning and community engagement

- Core step 4: Data collection and processing, including data-driven diagnostics

- Core step 5: Enhancing community participation and engagement

- Core step 6: Dissemination of findings

- Core step 7: Community goal-setting and other organized responses to the findings

- Core step 8: Policy and practice alignment

- Core step 9: Child and adolescent immersion in primary prevention environments, activities, and messages

- Core step 10: Repeat steps 1 to 9

Practice Profile: Critical components of the implementation of the Five Guiding Principles of the Icelandic Prevention Model

Guiding Principle 1: Apply a primary prevention approach that is designed to enhance the social environment

Rationale for critical component:

- Based on socioecological approaches, modifying the social environment reduces likelihood of substance use behaviours

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Implement prevention activities that target key risk and protective factors identified through the needs assessment

- Acceptable variation:

- The majority of key risk and protective factors are targeted in the design

- Unacceptable variation:

- Interventions focus on treatment or population already involved in substance use

- Intervention targets direct youth behaviour change

- Strategy is not informed by risk and protective factors element

Evaluation elements:

- Survey results (change in risk and protective factors targeted)

- Age group targeted by interventions

- Interventions reach a wide group (universal coverage)

- Community liaison credentials

Guiding Principle 2: Emphasize community action and embrace public schools as the natural hub of neighborhood and area efforts to support child and adolescent health, learning, and life success

Rationale for critical component:

- School environment is significant for youth development

- Schools are natural resources for community engagement

- Community-driven participatory approach

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Involve major school boards and support their engagement in the intervention

- Acceptable variation:

- Majority of schools participating in the initiative

- Majority of key partners attend regular meetings and endorse decisions

- Unacceptable variation:

- Insufficient participation from local schools

- Lack of buy-in from key community stakeholders

Evaluation elements:

- School engagement in intervention (high participation from main contact and from Steering Committee attendance)

- Steering Committee and Coalition meeting counts

- Strategy targets strengthened connections (connections between school and families, school and community, and community and families)

Guiding Principle 3: Engage and empower community members to make practical decisions using local, high quality, accessible data and diagnostics

Rationale for critical component:

- High-quality, current, comprehensive needs assessment to enhance community engagement

- Utilization-focused method enhances buy-in

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Ensure that over 85% of identified student population completes survey

- Ensure effective dissemination of survey findings

- Ensure that strategies align with key findings and recommendations

- Acceptable variation:

- 80-85% participation rate

- Significant coverage of key recommendations in strategy development

- Unacceptable variation:

- Below 80% participation

- Insufficient reach of survey findings

- Strategies aligned with less than 50% of identified key community issues

Evaluation elements:

- Percent of student population

- Number of student respondents as compared to the total student population

- Dissemination measurement

- Number of meetings

- Number of knowledge mobilization products

- Web-analytics

- Audience numbers by type

- Meeting attendance by stakeholders

- Key stakeholders identify that issues are relevant

- Satisfaction and engagement survey

- Participants rate issues as important, for example how important is it that the we decrease or increase specific risk or protective factors

- Coverage of key findings and recommendations

Guiding Principle 4: Integrate researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and community members into a unified team dedicated to solving complex, real-world problems

Rationale for critical component:

- Inter-disciplinary strategy enhances strategic planning, innovation and leveraging of skills

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal Implementation:

- Support partners to be involved in meaningful roles (relevant to their perspective and skill-set)

- Acceptable Variation:

- Majority of planning and decisions informed by inter-disciplinary perspectives

- Unacceptable Variation:

- Significant gaps in key stakeholder input to strategic planning

Evaluation elements:

- Participation rates by stakeholder in Steering Committee meetings (researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and community members)

- Interdisciplinary collaboration (relationships among researchers, policymakers, practitioners, community members)

Guiding Principle 5: Match the scope of the solution to the scope of the problem, including emphasizing long-term intervention and efforts to marshal adequate community resources

Rationale for critical component:

- Lack of dedicated time will lead to unrealistic expectations and potential loss of engagement momentum

- Insufficient resources will lead to challenges achieving desired outcomes and sustainability

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Ensure adherence to the design (strategy implementation is continuous over the time-frame)

- Attain long-term or permanent financial support

- Acceptable variation:

- Short-term funding acquired with plans to develop longer term support

- Unacceptable variation:

- Only short-term funding with no identification of long-term strategy

Evaluation elements:

- Strategies are implemented over long-term; monitoring time-frame

- Strategy implemented to community scale

- Sustainable financial supports

- Sustained community engagement (Implementation teams)

Practice Profile: Adaptation and Implementation of the Ten Core Steps of the Icelandic Prevention Model

Core step 1: Local coalition identification, development, and capacity building

Rationale for critical component:

- Community-based stakeholders must assume responsibility for implementation at the local level

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Establish a local coalition or steering committee with:

- Mixed local representation and professions, such as:

- Youth

- Elected officials

- Parents and caregivers

- Teachers and school administrators (faculty, principals, and superintendents)

- Social scientists and researchers able to work in an applied and community-engaged manner

- Community professional providers working in areas such as public health, medicine, mental health, sports and recreation, faith, law enforcement

- Mixed local representation and professions, such as:

- Local champions and local decision-makers

- One funded person (at minimum) with paid and protected time to build and maintain coalition capacity

- A community liaison with a strong background in community engagement, upstream prevention, and applied research

- Establish a local coalition or steering committee with:

- Acceptable variation:

- Over 75% of coalition characteristics met

- Unacceptable variation:

- Less than 75% of coalition characteristics met

Knowledge, skills and abilities:

- Governance

- Paid coordinator

- Stakeholder engagement

- Leverage existing partnerships

- Evaluation and performance measurement

- Coalition has influential status within the community

- Key insights from parents and caregivers, youth, and stakeholders working in education, health, government and research

Evaluation elements:

- Decisions are community-driven

- Recommended professional groups are represented

- Individual funded position has the specialized skills required

Core step 2: Local funding identification, development, and capacity building

Rationale for critical component:

- Funds are required in order to make system-level changes; longer-term cost savings will be generated

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Establish and distribute funding over a minimum of 5-year increments

- Redistribute existing community financial resources

- Develop long-term contracting and grants

- Create a permanent reorganization of existing institutional and organizational infrastructure

- Acceptable variation:

- Shorter time-frame funding with efforts to secure longer-term investment

- Infrastructure identified with plans for collaborative use

- Unacceptable variation:

- Only short-term funds secured

- No plan for sustainability

Knowledge, skills and abilities:

- Commitment from policy and philanthropy

- Fundraising capacity and stakeholder engagement

Evaluation elements:

- Financial tracking

Core step 3: Pre–data collection planning and community engagement

Rationale for critical component:

- Increases engagement and buy-in of local adults who will be responsible for implementation if they are involved in early decision-making

- Increases local understanding, trust of the research process and confidence in the findings

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Establish community coalition outreach with the population involved in strategy implementation

- Raise stakeholder awareness for strong knowledge of the initiative and how it works

- Acceptable variation:

- Reference group of local stakeholders are familiar with the process

- Unacceptable variation:

- Lack of awareness about the project overall

- Research process is unclear

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- Marketing and communication

- Partnership development

- Capacity-building

Evaluation elements:

- Web and social media analytics

- Number of data presentations or meetings (in-person and online)

- Attendance at presentations by stakeholder group

Core step 4: Data collection and processing, including data-driven diagnostics

Rationale for critical component:

- High-quality, current, comprehensive needs assessment to enhance community engagement

- Utilization-focused method enhances buy-in

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Coordinate annual data collection

- Over 85% participation rate

- Follow the 11 steps for planning and data collection in schools (see Kristjánsson, Sigfusson, Sigfúsdóttir, & Allegrante, 2013)Footnote 42

- Ensure that stakeholders recognize the need for a shared responsibility for action

- Acceptable variation:

- 80 to 85% participation rate

- Unacceptable variation:

- Below 80% participation

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- ICSRA partnership

- Alternative partnership for survey collection support

Evaluation elements:

- Participation rate

- Measurement of fidelity to the 11 steps for planning and data collection in schools

- Communications to schools to contextualize findings and emphasize shared responsibility among stakeholders

Core step 5: Enhancing community participation and engagement

Rationale for critical component:

- Changing the social environment requires the collaborative participation of a wide range of community members. Therefore, parents, caregivers, other professionals, and community members play a significant role in implementation.

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Establish outreach designed to maximize community participation and engagement

- Promote accessibility for community members

- Acceptable variation:

- Majority of relevant partners anticipate survey results and are consulted for potential opportunities to leverage outreach

- Unacceptable variation:

- Insufficient participation from relevant partners

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- Marketing and communication

- Stakeholder engagement

- Capacity-building

- Facilitation and training

Evaluation elements:

- Monitor supports provided for community participation, such as backfilling positions, providing meeting location, food, child care, and transportation assistance

Core step 6: Dissemination of findings

Rationale for critical component: Sharing results with the community will enhance community engagement and enable shared-decision making

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Prepare reports within 3 months post data collection. Ensure that the reports:

- use accessible language and visuals

- are targeted to key stakeholders and presenting data that is within their realm of control

- describe local-level information relative to other communities, including:

- rates of current substance use and trends

- levels of locally relevant risk and protective factors and relationships to substance use

- Ensure that meetings are accessible and employ social marketing

- Ensure that the local coalition owns all data, reports and communication products

- High participation in meetings and response to reports

- Prepare reports within 3 months post data collection. Ensure that the reports:

- Acceptable variation:

- Majority of relevant partners review and acknowledge findings

- Moderate to high participation in meetings and response to reports

- Unacceptable variation:

- Insufficient awareness of findings

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- Marketing and communication

- Partnership development

- Capacity-building, facilitation and training

Evaluation elements:

- Report is prepared within appropriate time frame

- Report has appropriate readability score

- Number of data presentations or meetings (in-person and online)

- Attendance at presentations by stakeholder group

- Web-analytics for social marketing

- Media exposure

- Engagement survey questions regarding accessibility

Core step 7: Community goal-setting and other organized responses to the findings

Rationale for critical component:

- Goals focused on reducing risk factors and strengthening protective factors for substance use initiation that are relevant to the community will enhance engagement and effectiveness

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Establish three to four widely supported community goals. The goals should:

- include specific strategies

- resonate among community members

- be associated with implementation strategies that are perceived as realistic

- Establish three to four widely supported community goals. The goals should:

- Acceptable variation:

- Majority of goals receive strong support from major stakeholders

- Unacceptable variation:

- Community stakeholders are not engaged in decision-making

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- Leverage existing partnerships

- Partnership development

Evaluation elements:

- Engagement survey (capture degree of consensus on goal priority within each community)

Core step 8: Policy and practice alignment

Rationale for critical component:

- Policy-makers and professionals must support community-identified goals to broaden and enhance impact

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Modify current policy and practice to align with the identified strategies

- Acceptable variation:

- Policy and practice that influence the identified strategies are adjusted to a significant extent

- Unacceptable variation:

- Policy and practice are in conflict with identified strategies

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- Implementation support

Evaluation elements:

- Monitor:

- Creation of new positions to support implementation

- Creation of new policies to support implementation

- Strengthening of existing activities

- Groundwork to support new activities

- Implementation of new activities

Core step 9: Child and adolescent immersion in primary prevention environments, activities, and messages

Rationale for critical component:

- Overall theory (from Guiding principle 1)

Description of implementation practice:

- Ideal implementation:

- Maximize youth exposure to a social environment that reduces the likelihood of substance use

- Acceptable variation:

- Strategies impact the majority of youth within the community environment

- Unacceptable variation:

- Only a subset of youth are impacted by strategy implementation

Knowledge, skills, and abilities:

- Implementation support

- Research and evaluation support

Evaluation elements:

- Enhanced youth mental health

- Decreased youth substance use

Core step 10: Repeat steps 1 to 9

- Reflect on the work that has been completed and repeat the steps again in a new cycle

4. Toolbox

Helpful links

- To learn more about evaluation and how to build logic models

- To learn more about indicators

- To learn more about implementation research and the practice profile:

- To learn more about positive youth development, prevention of substance-related harms, and socioecological approaches

- Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2018: Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Positive mental health surveillance indicator framework: Quick stats, youth (12 to 17 years of age), Canada, 2017 edition.

- Resources for preventing substance use and related harms among youth. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Adolescent Health. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- Search Institute

- To learn more about the Icelandic Prevention Model and Planet Youth

- Planet Youth

- Planet Youth Lanark County

- Lessons from Iceland: How one country turned around a teen drinking crisis. CBC Radio.

- 'A good news story': Lanark becomes first in Canada to adopt Icelandic model for reducing teen social harm. The Ottawa Citizen.

- Halsall, T., Lachance, L. & Kristjansson, A.L. (2020) Examining the implementation of the Icelandic model for primary prevention of substance use in a rural Canadian community: a study protocol. BMC Public Health, 20 (1235).

- Organizations supporting evaluation in the youth-serving sector:

Definitions

Community-based interventions:

Community-based health promotion interventions have been defined as initiatives that integrate the following criteria: they apply socioecological approaches, they are tailored to community needs and they engage community members within participatory strategies.Footnote 43

Community Coalitions:

Community Coalitions consist of individuals that represent diverse, multi-sectoral organizations in a community that work together to reach a common goal.Footnote 44

Socioecological approach:

Socioecological approaches examine the interactions of an individual within their community and lived environment.Footnote 45

Program theory:

A program theory is an explanation of how and why a program or intervention might contribute to the intended impacts. It should provide a logical description of the cause and effect relationships between a programs design and activities with related outcomes.

Risk and protective factors:

Protective factors are positive influences that can be associated with lower likelihood of problematic outcomes, behaviours, or experiences. Protective factors can also reduce the negative impact of risk factors on youth. Risk factors are negative influences that can be associated with higher likelihood of problematic outcomes, behaviours, or experiences.Footnote 46

References

- Footnote 1

-

Tam, T. (2018). The Chief Public Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2018: Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Footnote 2

-

Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B.,... & Kakuma, R. (2016). Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 387(10036), 2423-2478.

- Footnote 3

-

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P.,... & Herrman, H. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet, 392(10157), 1553-1598.

- Footnote 4

-

Kristjansson, A. L., James, J. E., Allegrante, J. P., Sigfusdottir, I. D., & Helgason, A. R. (2010). Adolescent substance use, parental monitoring, and leisure-time activities: 12-year outcomes of primary prevention in Iceland. Preventive Medicine, 51(2), 168-171.

- Footnote 5

-

Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., Kristjánsson, A. L., Thorlindsson, T., & Allegrante, J. P. (2008). Trends in prevalence of substance use among Icelandic adolescents, 1995–2006. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 3(1), 12.

- Footnote 6

-

Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., Kristjánsson, A. L., Gudmundsdottir, M. L., & Allegrante, J. P. (2011). Substance use prevention through school and community-based health promotion: a transdisciplinary approach from Iceland. Global Health Promotion, 18(3), 23-26.

- Footnote 7

-

Kristjansson, A. L., James, J. E., Allegrante, J. P., Sigfusdottir, I. D., & Helgason, A. R. (2010). Adolescent substance use, parental monitoring, and leisure-time activities: 12-year outcomes of primary prevention in Iceland. Preventive Medicine, 51(2), 168-171.

- Footnote 8

-

Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., Kristjánsson, A. L., Thorlindsson, T., & Allegrante, J. P. (2008). Trends in prevalence of substance use among Icelandic adolescents, 1995–2006. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 3(1), 12.

- Footnote 9

-

Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., Kristjánsson, A. L., Gudmundsdottir, M. L., & Allegrante, J. P. (2011). Substance use prevention through school and community-based health promotion: a transdisciplinary approach from Iceland. Global health promotion, 18(3), 23-26.

- Footnote 10

-

Kristjánsson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfúsdóttir, I. D. (2019). Implementing the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promotion Practice, 21 (1), 70-79.

- Footnote 11

-

Kristjánsson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfúsdóttir, I. D. (2019). Development and guiding principles of the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 62-69.

- Footnote 12

-

Pittman, K. (2001). Balancing the equation: Communities supporting youth, youth supporting communities. Community Youth Development Journal, 1(1), 19-24.

- Footnote 13

-

Pittman, K., Irby, M., Tolman, J., Yohalem, N., & Ferber, T. (2003). Preventing problems, promoting development, encouraging engagement: Competing priorities or inseparable goals? Based upon Pittman, K. & Irby, M. (1996). Preventing problems or promoting development? Washington, DC: The Forum for Youth Investment, Impact Strategies, Inc.

- Footnote 14

-

Catalano, R., Berglund, M., Ryan, J., Lonczak, H. & Hawkins, J. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 98-124.

- Footnote 15

-

Roth, J. L. & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). What exactly is a youth development program? Answers from research and practice. Applied Developmental Science, 7(2), 94-111.

- Footnote 16

-

Roth, J., Brooks-Gunn, J., Murray, L. & Foster, W. (1998). Promoting healthy adolescents: Synthesis of youth development program evaluations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(4), 423-459.

- Footnote 17

-

Richard, L., Gauvin, L., & Raine, K. (2011). Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 307-326.

- Footnote 18

-

World report on violence and health: summary. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002.

- Footnote 19

-

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard university press.

- Footnote 20

-

Moore, L., de Silva-Sanigorski, A., & Moore, S. N. (2013). A socio-ecological perspective on behavioural interventions to influence food choice in schools: Alternative, complementary or synergistic? Public Health Nutrition, 16(06), 1000-1005.

- Footnote 21

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2013). What Makes Canadians Healthy or Unhealthy?.

- Footnote 22

-

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Footnote 23

-

Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoorn, J., McRae, L., & Jayaraman, G. (2016). Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 36(1), 1-10.

- Footnote 24

-

Caldwell, L. L., & Darling, N. (1999). Leisure context, parental control, and resistance to peer pressure as predictors of adolescent partying and substance use: An ecological perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 31(1), 57-77.

- Footnote 25

-

Benson, P. L. (1997). All kids are our kids: What communities can do to raise caring and responsible children and adolescents. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

- Footnote 26

-

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170.

- Footnote 27

-

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Footnote 28

-

McDavid, J. C., & Hawthorn, L. R. (2006). Program evaluation and performance measurement: An introduction to practice. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

- Footnote 29

-

Chen, H. T. (1996). A comprehensive typology for program evaluation. Evaluation Practice, 17(2), 121-130.

- Footnote 30

-

Scriven, M. (1996). Types of evaluation and types of evaluator. Evaluation Practice, 17(2), 151-161.

- Footnote 31

-

Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Footnote 32

-

Kristjánsson, A. L., Sigfusson, J., Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., & Allegrante, J. P. (2013). Data collection procedures for school‐based surveys among adolescents: The Youth in Europe Study. Journal of School Health, 83(9), 662-667.

- Footnote 33

-

UNICEF (2019). Where Does Canada Stand? The Canadian Index of Child and Youth Well-being 2019 Baseline Report: UNICEF Canada.

- Footnote 34

-

Freeman, J. G. (2014). Health Behaviour in School-aged Children: Trends Report 1990-2010: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Footnote 35

-

Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention (2017). Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework: Quick Stats, youth (12 to 17 years of age), Canada, 2017 Edition. Health Promotion Chronic Disease Prevention Canada. 37(4), 131-2.

- Footnote 36

-

Boak, A., Elton-Marshall, T., Mann, R. E., & Hamilton, H. A. (2020). Drug use among Ontario students, 1977-2019: Detailed findings from the Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

- Footnote 37

-

Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 32.

- Footnote 38

-

Braithwaite, J., Churruca, K., Long, J. C., Ellis, L. A., & Herkes, J. (2018). When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Medicine, 16(63), 1-14.

- Footnote 39

-

National Implementation Research Network (2014). Practice profile.

- Footnote 40

-

Kristjánsson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfúsdóttir, I. D. (2019a). Development and guiding principles of the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 62-69.

- Footnote 41

-

Kristjánsson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfúsdóttir, I. D. (2019b). Implementing the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 70-79.

- Footnote 42

-

Kristjánsson, A. L., Sigfusson, J., Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., & Allegrante, J. P. (2013). Data collection procedures for school‐based surveys among adolescents: The Youth in Europe Study. Journal of School Health, 83(9), 662-667.

- Footnote 43

-

Baker, E. A., & Brownson, C. A. (1998). Defining characteristics of community-based health promotion programs. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 4(2), 1-9.

- Footnote 44

-

Kristjansson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2020). Implementing the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health promotion practice, 21(1), 70-79.

- Footnote 45

-

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.). Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793-828). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Footnote 46

-

Growing up Resilient. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.