How to integrate intersectionality theory in quantitative health equity analysis? A rapid review and checklist of promising practices

Download the report (PDF)

(PDF format, 70 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2022-06-13

Download the checklist (PDF)

(PDF format, 3 pages)

Download the checklist (Word)

(Docx format, 3 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2022-06-13

Highlights

Highlights from the "How to integrate intersectionality theory in quantitative health equity analysis? A rapid review and checklist of promising practices" technical report.

On this page

Overview

The burden of diseases and health conditions isn't shared equally among all Canadians. Some people are more likely to get sick or die because of their social and economic conditions. We call these "health inequalities".

There are many ways to measure health inequalities. One main approach is to compare groups of people, based on one single factor. For example, we can calculate health inequalities by gender. To do so, we could compare the health of men compared to women.

Yet, this type of analysis is not perfect. When we only look at one factor, two things can happen. One, we can miss other important personal characteristics, like age or ethnicity. These other factors can also influence health. Two, when we only focus on one factor, we can miss out on understanding how it relates to other factors.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Black feminist scholars in the US explored this topic. One of these scholars was Kimberlé Crenshaw. She wrote about the experiences of Black women. Black women experience the world in a different way than Black men or white women. This is because Black women face discrimination based on their gender and their race.

Crenshaw coined the term "intersectionality". Intersectionality refers to how sources of discrimination overlap and reinforce each other. It also refers to the reality that we all have many identities that intersect to make us who we are.

In public health, we can apply intersectionality theory to better understand health inequalities. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is eager to do this. But first, PHAC needed to develop a road map of how to do so. This information is crucial for future reporting by the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative or "HIRI". HIRI aims to track and report on health inequalities in Canada. It does so to inform health and social policy, to ensure health and well-being for all.

This report helps fill the gap in evidence. It summarizes a literature review. This review explored how to apply intersectionality in data analyses of health inequalities.

Method

PHAC performed a rapid literature review. We looked at 34 studies that explored health inequalities. Each of these studies aimed to integrate intersectionality theory.

Reading these articles, we analyzed how they applied the theory. To do so, we used an existing framework. We used the Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA) framework. This framework identified the eight guiding principles of intersectionality theory:

- Intersecting categories

- Multi-level analysis

- Power

- Equity

- Social justice

- Time and space

- Diverse knowledges

- Reflexivity

We looked at out each of the studies to see how they integrated the eight principles. Then, we synthesized our findings.

Key findings

We identified over 35 promising practices of ways to integrate intersectionality theory. These practices include steps to take when designing an analysis. For example, it is important to:

- Engage with the communities that experience the inequalities that are being studied

- Review both qualitative and quantitative background evidence.

The promising practices also include steps to take at the data analysis phase:

- Exploring inequalities across time

- Analyzing determinants that could be addressed through interventions.

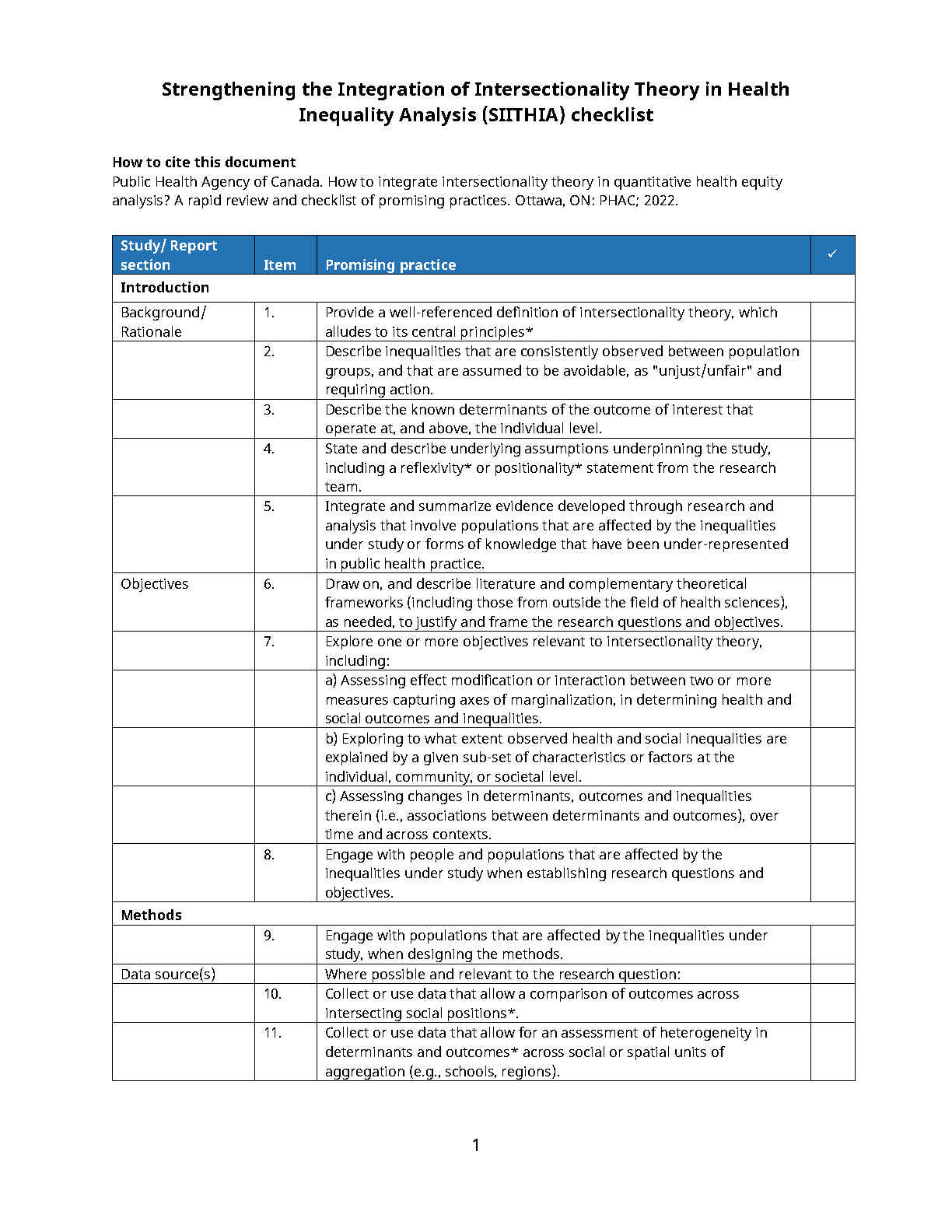

These are but a few examples. We present the full list of promising practices using a checklist format. We call this new checklist the "Strengthening the Integration of Intersectionality Theory in Health Inequality Analysis" (SIITHIA) checklist. The checklist is in Section 3.5 of the report.

Conclusion

Integrating intersectionality theory will be helpful for public health. It will help us study how sources of discrimination overlap and reinforce each other. In turn, this can help us better understand how health inequalities come to be.

The SIITHIA checklist is a tool to help guide the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative. It is also a tool for health researchers and surveillance initiatives. The checklist should empower future studies to meaningfully integrate intersectionality theory into practice.

Table of contents

- Index of figures

- Index of tables

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Methods

- 3.0 Results

- 4.0 Discussion

- 5.0 Conclusion

- Recommended reading

- Glossary

- 6.0 References

- 7.0 Supplementary material

- 8.0 Acknowledgements and Authors

Index of figures

- Figure 1: Flowchart of study screening and selection

- Figure 2: Social stratification (exposure) measures used across the 34 reviewed studies

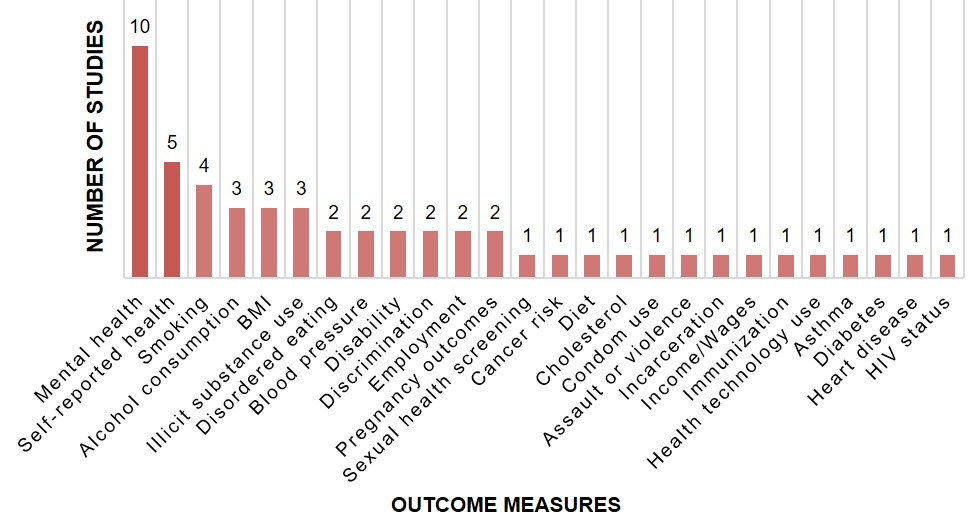

- Figure 3: Outcome (dependent) measures used across the 34 reviewed studies

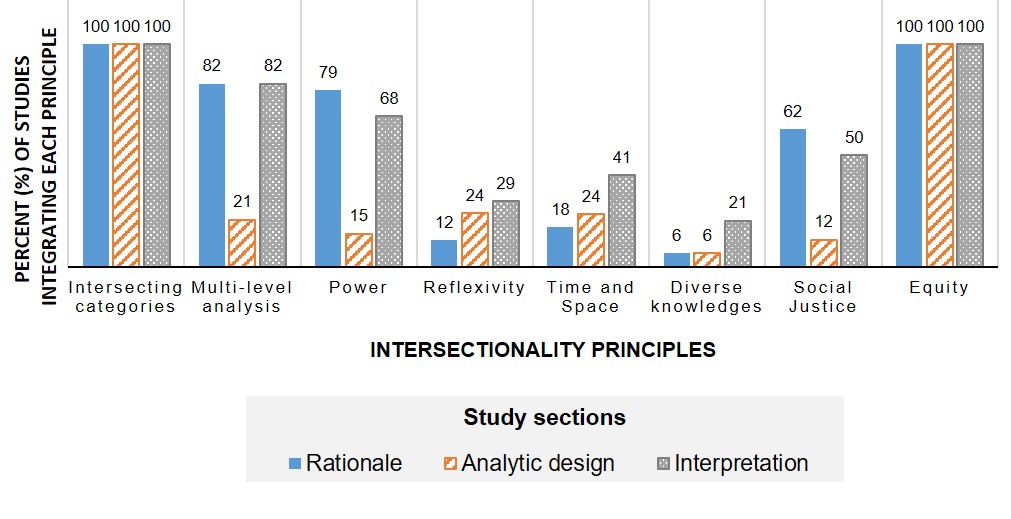

- Figure 4: Integration of intersectionality principles, by study sub-sections (n=34 studies)

Index of tables

- Table 1: Rapid literature search terms

- Table 2: Data elements extracted from retained articles

- Table 3: Intersectionality principle definitions and deductive analysis employed

- Table 4: Promising practices for integrating intersectionality theory in the rationale for quantitative health equity analysis

- Table 5: Promising practices for integrating intersectionality theory in the analytic design of quantitative health equity analysis

- Table 6: Promising practices for integrating intersectionality theory in the interpretation phase of quantitative health equity analysis

- Table 7: Strengthening the Integration of Intersectionality Theory in Health Inequality Analysis (SIITHIA) checklist

Executive Summary

Background

Emerging from Black feminist scholarship in the late 1980s, intersectionality theory can be applied as an analytic framework to better understand, describe and respond to health inequalities in a way that addresses fundamental determinants of health, and promotes social justice and health equity. As such, integrating intersectionality theory into health inequalities surveillance activities has been identified as one of many priority topics, theories and methods for the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative and Canadian health inequality surveillance more broadly. However, a summary of promising practices to operationalize this theory into practice, particularly in its integration at all stages of quantitative analysis, from problem identification, to methodological design and findings interpretation, is currently missing from the literature. This rapid literature review aimed to fill this knowledge gap.

Objective

The overall aim of this review was to identify promising practices to meaningfully integrate intersectionality theory in quantitative analyses of health inequalities between population sub-groups. Specifically, we aimed to identify how studies that have applied this theoretical framework integrated its central principles into each step of the analyses, from problem identification and rationale setting, to methodological design and the interpretation of results. Herein, we do not posit that the identified attempts at incorporating intersectionality theory’s principles can or should be defined as standard or "best" practices. Rather, they represent promising directions that could continue to be explored, in tandem, in future analyses that aim to meaningfully integrate intersectionality theory in health inequality analysis.

Purpose and intended audience

The primary purpose of this technical report is to guide future enhanced intersectionality-informed quantitative data analysis of health inequalities between population sub-groups, for the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting (HIR) Initiative. This report is therefore intended for a technical audience of public health professionals and other health system actors with epidemiology and biostatistics training, who have completed initial readings on, and have a basic familiarity with intersectionality theory. A reading list and Glossary section are provided to define key tenets of intersectionality theory and relevant terminology. Readers who are less familiar with intersectionality theory are recommended to complete these readings and a review of this report’s glossary section before reading the rest of this report.

Methods

We performed a rapid literature review of works that were explicitly designed to integrate intersectionality theory in their quantitative analysis of health inequalities. Articles were identified through a search of Scopus and Medline databases. To guide our review’s assessment of how intersectionality theory was integrated throughout these studies, we drew on the Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA) framework’s eight "guiding principles" of intersectionality theory. Defined in detail in the text, these include intersecting categories, multi-level analysis, power, equity, social justice, time and space, diverse knowledges and reflexivity (see Glossary for definitions). Information from relevant publications was extracted. We performed a narrative synthesis of how each of the eight principles could be integrated when monitoring health inequalities using quantitative data sources.

Results

We identified over 35 promising practices of ways to integrate the core principles of intersectionality theory in quantitative analyses of health inequalities, at every step of research or surveillance design, from conceptualization to reporting. The application of stratified or interaction-based analyses is not sufficient to meaningfully integrate this theory into practice. A summary of the promising practices to more meaningfully integrate intersectionality theory is presented using a checklist format. The "Strengthening the Integration of Intersectionality Theory in Health Inequality Analysis" (SIITHIA) checklist prototype is proposed (Results Section 3.5). This tool can guide future Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative analyses, as well as research, evaluation and surveillance methodologies, so that they may overcome previously identified limitations in quantitative intersectionality-informed analyses of health inequalities.

1. Introduction

In 2018, the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting (HIR) Initiative published its Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait report Footnote 1, which provided a comprehensive baseline description of the state of health inequalities in Canada. The report describes the various population sub-groups that bear a disproportionate burden of adverse health and social outcomes in Canada. Drawing on the Social Determinants of Health Framework Footnote 2, the report highlights how these health inequalities are determined by systems and structures that represent "fundamental" determinants of health Footnote 3 and how these systems or structures are often intersecting. Indeed, scholars have described health determining "systems of domination" such as racism, sexism, and colonialism as "co-constitutive" (i.e., essential to each other’s existence) and mutually reinforcing Footnote 4, Footnote 5, for the ways in which they intersect or "interlock" to mutually reinforce inequitable distributions of health promoting resources and power within societies. However, the 2018 HIR Initiative report Footnote 1 acknowledged that it:

"did not attempt to disentangle the multiple intersections between and among different social positions and/or different determinants of health, although it is acknowledged that health inequalities are driven by a complex system of social factors (i.e. structural and intermediary determinants of health) that remain to be fully explored and understood."

Several theoretical traditions have explored the connectedness of structural determinants of health. Among them is the domain of intersectionality theory. As such, intersectionality theory was identified as one of many priority topics, theories and methods to explore in future HIR Initiative reporting.

1.1 What is intersectionality theory?

Broadly, intersectionality theory is an analytic framework and research paradigm that stresses a need to consider the ways in which connected systems and structures of power operate across time, place, and societal levels, to construct intersecting social locations and identities (e.g., along axes such as race, gender, class, and sexual orientation, among others) (see Box 1 through processes of privilege and oppression Footnote 6, Footnote 7. Intersectional feminist theorizing can be traced back to the unique challenges faced by African American women in the United States (US) who face systems of oppression that operate at different levels and are frequently interlocking Footnote 4. Intersectionality theory was developed as a theoretical paradigm to move beyond analyzing individual categories of difference Footnote 8, Footnote 9. Early formulations of intersectionality theory in the late 1970s, led by the Combahee River Collective—a collective of Black lesbian feminists committed to "struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression"— Footnote 10, responded to how various forms of discrimination, including racism, classism and heterosexism shaped Black women’s lives simultaneously, contributing to multiple social inequalities Footnote 9, Footnote 11. Critical race theorist and legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw and sociologist Patricia Hill-Collins are credited as pioneering more contemporary understandings of this theoretical perspective, and have articulated how multiple forms of oppression interlock and result in patterns and processes distinct from singular forms of discrimination. Importantly, these scholars emphasized how embedded systems of power and oppression, result in patterns of domination, privilege and continued inequality Footnote 12–Footnote 14. Intersectionality theory seeks to address the convergence of these systems of power whereby multiple marginalization (effected along axes such as race, sex, gender, class, sexual orientation, dis/ability), at individual and structural levels, require analysis and policy solutions that can address how intersections of these categories create and maintain inequality Footnote 11, Footnote 15.

Box 1: Key intersectionality-related terms and concepts

The Glossary section of this report provides definitions of several key terms and concepts that pertain to the topic of intersectionality theory.

Throughout the text, the term "identity" will be used to refer to markers of the sub-groups defined along categories of difference. For example, Black identity is a sub-group marker the constructed category of difference of race Footnote 5.

Below, this report gives a brief overview of key historical references, theorists, concepts, and applications of intersectionality theory. Important theoretical conversations are on-going on how best to apply this theory across scientific domains and contexts. It was beyond the scope of this report to provide an in-depth history of this theoretical framework and these debates. These have been published elsewhere (e.g. see: Hancock, AM. Intersectionality. An Intellectual History. Oxford University Press, 2016).

1.2 How has intersectionality theory been applied in health research?

Intersectionality theory has been applied across a wide range of disciplines, including, more recently, in quantitative public health and epidemiologic research. Within the Federal Government of Canada, it forms the theoretical underpinning of the "Plus" of Gender Based Analysis PLUS (GBA PLUS) Footnote 16.

A recent systematic review of the application of intersectionality theory in quantitative research studies Footnote 17 found that a majority of published studies integrating this theory use what Leslie McCall Footnote 18 and others have described as an "inter-categorical" analysis approach. This approach presumes that complex relationships of inequality exist among social groups within and across identities, and seeks to focus analysis on these relationships Footnote 18. Operationally, inter-categorical analysis makes use of multiple categorical measures (or so-called "categories of difference"; see Glossary for definition) to study the experience of groups, defined according to multiple axes of identity Footnote 18, Footnote 19. For example, an inter-categorical analysis may seek to explore the prevalence of certain health condition (e.g. diabetes) across income quintiles and gender, to explore how the relationship between income and diabetes risk differs for men and women.

Inter-categorical analyses are often defined in contrast to two other approaches. More common in qualitative research methodologies such as ethnographic research, one is an "anti-categorical" approach, which rejects the notion that categories of difference are immutable (i.e, unchanging across time, place, or context) Footnote 18. An anti-categorical analysis is interested in questioning boundaries of constructed categories (e.g., studies that interrogate the "completeness" of binary gender categories such as "men" and "women"). The other type is an "intra-categorical" approach, which explores the experiences of a single sub-population/group (e.g., Arab people in the US) and explores within-group differences along one or more intersectional locations (e.g., class, gender, sexual orientation), such as the study of outcomes among "Arab American, middleclass, heterosexual [women]" Footnote 18). Both of the latter two approaches are common in qualitative research studies Footnote 17, and can be used in quantitative analyses as well.

In the domain of quantitative intersectionality-informed health inequality research, common types of statistical analyses include stratified descriptive or regression-based analysis, as well as regression-based effect measure modification or interaction analysis, multi-level modeling, structural equation modeling, as well as decision or classification tree, mediation, decomposition, latent class and cluster analysis, and multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) analysis (see Glossary for definition) Footnote 17.

However, the application of intersectionality theory in quantitative health inequality analyses has faced criticism. First, scholars have critiqued extant studies’ limited engagement with the central principles of intersectionality theory Footnote 17, Footnote 20, Footnote 21. Some studies omit a definition of the theory altogether Footnote 17, or focus primarily on differences in outcomes across multiple social identities, without a more in-depth analysis of structural discrimination through policies and institutional practices Footnote 22 or a focus on social justice Footnote 21 that are core to the theory’s understanding of power and oppression Footnote 12–Footnote 14, Footnote 21. Meaningful engagement with the theory has been identified as "essential in order to maintain the critical and transformative edge of intersectionality" Footnote 19.

Second, the focus of inter-categorical analyses on differences between groups can obscure within-group heterogeneity and reproduce binary constructs that negate the fluid and dynamic nature of group membership and intersections Footnote 23. Third, many studies describe inequalities without exploring the mechanisms that explain the observed differences and that could be addressed through health or social policy intervention. Methods such as mediation or decomposition analyses can help fill these knowledge gaps Footnote 23. Bauer et al. distinguish these as "descriptive" and "analytic" intersectionality approaches, respectively Footnote 17, Footnote 24, and note that many studies lack a clear central research question to guide their analytic approach. Fourth, many studies explore differences in outcomes across sex/gender, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) measures, without considering other intersectional categories Footnote 23. Fifth, studies of health inequality often examine inequalities on either or both an absolute/additive and relative/multiplicative scale (e.g., prevalence differences and ratios, respectively) Footnote 25. Not all studies measuring inequalities on a multiplicative scale, however, explore the differences in the effects of social positions across intersecting identities (e.g., interaction or effect measure modification) on an additive scale. The additive scale has been identified as most relevant for public health application Footnote 17, since departure from additivity highlights instances when disease burden depends on the extent to which two or more factors occur together in the same individuals (see Box 2) Footnote 26.

Box 2: The importance of additive-scale effect modification for public health

Additive interaction (or departure from additivity) is present when the attributable risk of any given outcome or disease in those exposed to a risk factor, A, varies as a function of another risk factor, B. For example, if a risk factor A is tobacco smoking, and a risk factor B is diabetes, if the attributable risk of a disease such as lung cancer is higher among those who smoke and have diabetes, e.g. 20 cases/100,000 population, and lower among those who smoke but do not have diabetes, e.g. 5 cases/100,000 population, this information is important to guide public health interventions. Namely, it may be that targeting a tobacco cessation program to those who have diabetes could lead to a greater reduction in the number of incident cases of lung cancer. Further details on additive interaction or effect modification have been published Footnote 27.

1.3 Aims and purpose of this report

In sum, interest in this theory is growing, but guidance on the ways to integrate the theory systematically and rigorously into quantitative public health and epidemiologic study, is limited. Indeed, in their recent systematic review of intersectionality-informed quantitative studies, Bauer et al. Footnote 17 highlight the overall need for reporting guidelines and recommendations for future intersectionality-informed research.

Aiming to help fill this gap in the literature, the objective of this review was to identify promising practices to integrate intersectionality theory in quantitative analyses of health inequalities between population sub-groups. Specifically, we aimed to identify how studies that have applied this theoretical framework integrated its central tenets and principles into each step of the analysis, from problem identification and rationale setting, to methodological design, and the interpretation of results. To do so, we performed a rapid literature review of works that were designed explicitly to integrate intersectionality theory in their analysis of health inequalities between population sub-groups. To guide our review’s assessment of how intersectionality theory was integrated throughout these studies, we drew on the eight guiding principles underpinning Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA) framework Footnote 16. The IBPA framework provides a summary of the eight guiding principles of intersectionality theory. Defined in detail below, these include intersecting categories, multi-level analysis, power, reflexivity, time and space, diverse knowledges, social justice, and equity (see Glossary and Methods section 2.6b for definitions). We assessed how each of the eight principles could be integrated into quantitative analyses of health inequalities.

2. Methods

2.1 Positionality statement

In the field of intersectionality-informed research, it is customary for researchers to provide a written reflection on the social positions and operating contexts of the authorship team, its location within systems or structures of power, as well as their underlying scholarly or analytic assumptions, before launching into the details of their work. These details are referred to as "positionality statements" or "reflexivity statements" Footnote 28. This reflexive exercise can help practitioners acknowledge and deconstruct underlying assumptions or practices that, often unintentionally, reinforce structures of power or oppression Footnote 16. To ensure that this report is aligned with the fundamental principles of intersectionality theory, namely the principle of reflexivity, we (the authors) will begin by stating a few words about the positionality of our team and the broader context in which this work was conducted:

We (the authors) are working within Canada’s national public health agency (the Public Health Agency of Canada), as analytic leads for the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting (HIR) Initiative. We come from diverse disciplinary backgrounds (epidemiology, public health, sociology, psychiatry, occupational health, environmental science). We also come from diverse economic, racial, ethnic, gender and sexual orientation backgrounds. However, none of our team members identify as Indigenous. We respectfully acknowledge that each of us contributed to this report from traditional, unceded First Nation territories. Specifically, this report was developed in Montreal, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Mohawk (Kanien’kehá:ka) Nation; and in Toronto, on the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation; and in Ottawa, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishnaabe people.

The HIR Initiative’s mandate is to monitor and report on health inequalities in Canada in order to guide health equity-informed health and social policy Footnote 1 . The Initiative is motivated by an understanding that health inequalities cannot be addressed without intervention on the broad social, economic, and political factors that generate and reinforce societal hierarchies and inform the social and material conditions in which individuals are born, grow, live, work and age Footnote 1 . This understanding of the fundamental determinants of health is aligned with several of the key principles of Intersectionality theory, namely of equity and social justice.

The HIR Initiative is informed by an empirical positivist tradition of quantitative epidemiologic surveillance Footnote 29 and social epidemiological understandings of population health Footnote 30 and the Social Determinants of Health framework Footnote 2. The methodology of this review was informed by those paradigms. Namely, since this review was designed to inform future analyses led by the HIR Initiative, we aimed to identify promising practices of applying intersectionality theory within quantitative, epidemiological analyses of health inequalities between population sub-groups. Although the application of purely qualitative methods has been outside the scope of past HIR Initiative data analyses, we acknowledge the importance of qualitative and mixed methods analyses for population and public health research and practice.

Further, as employees of Canada’s federal government, we are aware of our position within an institution of power and privilege that, due to the ways that systemic racism is "at the core of many institutions" Footnote 31 has and continues to perpetuate harms towards several groups and communities, in ways that hamper health equity goals Footnote 32–Footnote 36. Given our position within this institution, we wanted to ensure that the methods we employed in this review do not contribute to the previously-documented co-optation of intersectionality theory Footnote 37—a radical, anti-oppressive, grassroots-born theoretical paradigm—for further oppression or domination. Our work is aligned with the Federal Anti-Racism Strategy’s guiding values of justice, equity, human rights, diversity, inclusion, decolonization, integrity, anti-oppression and reconciliation Footnote 38. As such, we designed the review’s analysis and data extraction methods so as to be as thorough as possible in our identification of meaningful promising practices that could be employed at every step of study design, including those occurring before and after the step of data analysis.

This review was designed and conducted within a broader social and political moment in Canadian history. Namely, it was conducted in 2021, in the second year of the global COVID-19 pandemic, and following the murder of George Floyd and the resulting worldwide recognition of ongoing police brutality perpetuated against Black populations in the United States and other countries, including Canada. It was also a year that brought into focus the enduring legacy of colonialism and systemic racism in Canada Footnote 39, namely through the death of Joyce Echaquan Footnote 40 and the discovery of mass graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation territory Footnote 41, and at other residential schools across the country. These deaths brought attention to the violence and on-going trauma of colonialism and Canada’s residential school system, as previously detailed in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports Footnote 42. In Canadian society, including the federal public service, there has been an increasing recognition of ongoing violence, systemic racism, and discrimination against racialized and Indigenous populations and more established evidence of the unequal health and socioeconomic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This present report follows several reports developed by Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer, Dr. Theresa Tam, which focused on stigma and health equity during the COVID-19 pandemic Footnote 43, Footnote 44. These reports emphasize the importance social justice and equity for health promotion, and the need for transformative action to address structures of power—all of which is aligned with the central tenets of intersectionality theory.

This context has highlighted the need, within public health institutions such as PHAC, to draw on theoretical frameworks, such as intersectionality theory, that openly engage with topics such as racism, colonialism and other systems of oppression. This review is therefore shaped and informed by this broader historical and contemporary context.

Lastly, given that this report was produced in the second year of the global COVID-19 pandemic and our team faced several concurrent priorities, we did not have the time nor the human resources to conduct a full systematic review. A rapid review design was therefore employed.

2.2 Design

A rapid review design was selected to achieve this study’s objectives. Rapid reviews are increasingly recognized as a useful design for literature synthesis, particularly to inform and guide policy action in governmental contexts Footnote 45. While following similar rigorous methodological steps to a systematic review, a rapid review focuses on a non-systematic approach to finding evidence, which allows for the review to be completed in a shorter timeframe. Using a non-systematic study identification approach, rapid reviews risk overlooking relevant studies Footnote 46. However, evidence suggests that overall, general conclusions and take-home messages tend to be similar between rapid reviews and systematic reviews that are completed within three to six months Footnote 47.

2.3 Eligibility criteria

This rapid review aimed to identify studies with the following characteristics: 1) they were explicitly guided by intersectionality theory, and 2) applied a quantitative design or a mixed-methods design with a quantitative analysis element. Further, since this review was designed to identify promising practices to integrate intersectionality theory in quantitative analyses of health inequalities between population sub-groups, studies of interest were required to 3) have conducted an analysis of a health-related outcome—the outcome topic area was kept intentionally broad to capture a larger body of relevant studies—at the intersections of 4) two or more exposure measures, that capture "categories of difference" (see Glossary for definitions) (e.g., age, race, gender, etc.), i.e. applying a so-called "inter-categorical intersectional analysis" approach that compared outcomes between groups (the exclusion of intra- or anti-categorical analyses is discussed below). Further, 5) their target population and sampling design were sufficiently broad to allow for findings that could be generalizable to a large population and therefore meaningful for population health. They could come from any country, setting, or time frame, but 6) were required to be written in English or French due to the linguistic abilities of the authors of this report.

As such, studies were excluded if they 1) did not explicitly integrate intersectionality theory in any element of study design. More specifically, papers describing the importance of intersectionality theory without a practical application or integration of the theory in study design were excluded. Studies that introduced the concept of intersectionality and utilized the theory to develop their study objectives and design, despite providing no fulsome definition of the theory were not excluded since we assumed that certain journal audiences may be familiar with the theory and not to require a definition. Studies were excluded if they 2) did not explore health-related inequalities between two or more groups (i.e., that they used a so-called "inter-categorical" approach; see Glossary for definitions). We used this practical criterion rather excluding studies based on labels of "anti-" or "intra-categorical" analysis, insofar as previous reviews have identified challenges at applying McCall’s Footnote 18 typologies in quantitative analyses Footnote 17. For example, depending on its objectives and scope, an analysis of the intersections between race and sexual orientation within a sub-sample of women could be considered as an intra- or inter-categorical approach. Since we aimed to identify promising practices to integrate intersectionality when studying health inequalities between groups, we excluded studies that did not include any form of inequality estimation. We also excluded studies that 3) focused solely on outcomes pertaining to clinical practice; or 4) were purely qualitative in design. Lastly, we excluded (5) commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts and registered research protocols, as these did not present sufficient information to assess how intersectionality theory was integrated from methods design, to analysis, and results interpretation.

2.4 Search strategy

Studies were identified using Scopus and Medline databases (via Pubmed, Ovid Medline, and Global Health Ebsco). Search strings were constructed based on three themes: (1) intersectionality-related constructs or concepts; (2) public health and health equity; and (3) quantitative or mixed-methods analysis, as depicted in Table 1 (detailed search strings are described in Supplemental File Section 7.1 Search strategy). According to the rapid review framework’s Footnote 48 intention of rapidly identifying the most relevant set of articles to answer the study question Footnote 48, we applied a restrictive search strategy, such that articles were required to mention the terms "intersectionality" or "intersectional" in their title or abstract (Table 1). Lastly, a snowball search approach was also used to identify applied studies of intersectionality integration in quantitative analysis that were referenced in other papers but that were not found using the initial search strategy.

| Theme | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1) Intersectionality-related constructs and concepts | Intersectionality, intersectional |

| 2) Public health & Health Equity | Health status disparities, health status indicators, health determinants, social determinants of health, minority health, underserved, public health, population health, health equity, health inequalities, health inequities, epidemiology, social determinants of health, marginalization, marginalized, marginalisation, marginalised, oppressed, discrimination, stigmatized, stigmatization, stigmatisation, stigmatised, social identit*, social position*, vulnerability, vulnerable, race, racialized, race-based, ethnicity, ethnocultural group*, ethnocultural concentration, LGBTQ2, LGBT, LGBTQ, sexual orientation, sexual minority, gender-based, socioeconomic status, indigenous people*, indigeneity, rural, urban, immigrant*, abilit*, disabilit*, age |

| 3) Quantitative or mixed-methods analysis | Quantitative, mixed, empirical research, evaluation studies, statistic, |

| * Indicates "truncation" or "wildcard" search term | |

2.5 Study identification

Initial title and abstract screening was conducted using Rayyan software Footnote 49. First, one reviewer (AES) screened all titles and abstracts of studies identified through the search strategy. A second independent reviewer (DC) screened 20% of identified studies to verify compatibility with AES’s review. There was 92% agreement between the two independent reviewers for this subset of articles. The two reviewers met to discuss any disagreements and reach consensus. The retained studies were kept for full-text review. A similar review process was completed for the full-text review stage. One reviewer (AES) screened all full texts. As second independent reviewer (DC) screened the full texts of 20% of retained articles. There was 86% agreement between the two independent reviewers for this subset of articles. The two reviewers met to discuss any disagreements and reach consensus. At this penultimate stage, a third reviewer (AB) reviewed the full texts of all (100%) retained eligible articles to validate whether all studies identified met inclusion criteria. All disagreements were discussed with the primary reviewer (AES) to reach consensus on the final set of articles included in the review.

2.6 Data extraction and analysis

a) Data elements

Data elements extracted from the articles included in the review fell into three themes: (1) general information about the study rationale, questions, and theory; (2) data on study design and methods; and (3) data on concrete examples of the integration of intersectionality theory principles in the rationale, analytic design, and interpretation sections of the studies, respectively (Table 2).

| Theme | Data element |

|---|---|

| Study rationale, objectives and theory |

|

| Study design and methods |

|

| Integration of intersectionality theory principles throughout the study |

|

b) Analysis of the integration of intersectionality theory

In a recent systematic review Footnote 17, researchers explored how intersectionality theory was applied in quantitative data analyses by assessing whether papers 1) included a definition of the theory, 2) cited its foundational authors, 3) cited seminal "quantitative intersectionality methods papers" (based on a pre-specified list), and whether 4) measures of "social position" or categories of difference (see Glossary for definitions) that were used in the studies were tied back to the concept of social power, and 5) outcomes were estimated and reported for all social position intersections under study. In their discussion of their findings, the authors of the latter review Footnote 17 highlighted gaps in existing studies, and identified the need for guidance on the ways to integrate the theory more systematically and rigorously into quantitative public health and epidemiologic analysis.

Thus, to build on the latter review, this rapid review took a different methodological approach. Namely, to be able to guide a more systematic application of the theory into future analyses, this review sought to explore how intersectionality-informed studies integrated 1) every major tenet of intersectionality theory, 2) at each step of analysis (from problem identification and rationale setting to methodological design, and the interpretation of results).

To do so, we first needed to select a conceptual framework that enabled the identification of each of the major central tenets of intersectionality theory. For this, we drew on the eight "Guiding Principles" of the Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA) framework. The IBPA framework was designed as a tool to "illuminate how policy constructs individuals’ and groups’ relative power and privileges vis-à-vis their socio-economic-political status, health and well-being" Footnote 50. The IBPA framework has two components: 1) a compendium of guiding principles, and 2) a list of overarching questions to guide analysis. Importantly for the purposes of this review, the IBPA framework’s set of eight guiding principles of intersectionality-based policy analysis are designed to "advance the central tenets of intersectionality" Footnote 16. Discussed in detail below, the eight principles are:

- Intersecting categories

- Multi-level analysis

- Power

- Reflexivity

- Time and space

- Diverse knowledges

- Social justice

- Equity

To assess how intersectionality theory was integrated throughout the selected studies in this review, we used the eight guiding principles of the IBPA framework as an analytic lens to ensure that we captured each of the central tenets of intersectionality theory. Specifically, we used a deductive thematic analysis approach Footnote 51, Footnote 52, wherein each study was analyzed to identify how they engaged with each of the eight pre-specified principles in their rationale, analytic design, and interpretations. As noted in previous reviews Footnote 21, applied alone, the identified practices and methods below should not be interpreted as inherently "intersectionality-informed" or sufficient for a study to be described as "intersectional". Rather, the objective of this review’s analysis was to identify promising practices that, when applied in tandem, could enable analysts to more meaningfully integrate each of the key tenets of intersectionality theory into to their work.

Table 3 summarizes the definitions of eight intersectionality principles that were examined, as well as how thematic analyses were performed to assess the integration of each principle in each study. Information on whether the principle was integrated (yes/no) and how it was integrated, was extracted. A complementary quantitative analysis was performed, wherein per study section, a score of 1 was attributed if the principle was integrated, and 0 if it was not. Scores ranged from 0 to 8 per study section (rationale, analytic design, interpretation). It should be noted that since the goal of this review was to identify promising practices to integrate intersectionality theory, overall, the categorization of methods across guiding principle categories was not done conservatively; some approaches or methods were attributed to more than one principle (e.g. both "space and time" and "multi-level analysis"). Due to time limitations, no quality assessment was performed on the reviewed works.

| Intersectionality principle | Meaning | Deductive analysis strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Intersecting categories | Refers to how "intersectionality conceptualizes social categoriesFootnote * as interacting with and co-constituting one another to create unique social locationsFootnote * that vary according to time and place. It is these intersections and their effects that are of concern in an intersectionality analysis" (p.35 in Footnote 16). |

Integration of this principle was assessed by exploring how studies operationalized multiple social stratification measures (i.e. "categories of difference" or "social categories"), such as race, Indigeneity, gender, etc., and considered their potential intersection or interaction. Note: we did not explicitly assess whether or how authors explored the co-constitution of social categories. |

| Multi-level analysis | Refers to the importance of "understanding the effects between and across various levels in society, including macro (global and national-level institutions and policies), meso or intermediate (provincial and regional-level institutions and policies) and micro levels (community-level, grassroots institutions and policies as well as the individual or ‘self’)" (p.35 in Footnote 16). |

We assessed the integration of this principle by identifying whether and how studies considered conceptually and analytically, multi-level determinants of health, including social processes, power structures, and policy, and their associations from the individual- to structural- or systems-levels. |

| Power | Captures the notions that "subject positions and categories (e.g.,, ‘race’) are constructed and shaped by processes and systems of power (e.g., racialization and racism); […] these processes operate together to shape experiences of privilege and penalty between and among groups" (p.35 in Footnote 16). |

Integration of this principle was assessed by seeking to identify whether and how studies considered, conceptually or analytically, how systems of powerFootnote * operate, intersect, are reproduced, or how they can be resisted. Particular attention was paid to identifying how studies move beyond an additive conceptualization of oppression or marginalization (e.g., to simply identify the most vulnerable groups), towards an analysis of the fundamental systems or structures that create and enable inequalities. |

| Reflexivity | Reflexivity refers to "practices that bring critical self-awareness, role-awareness, interrogation of power and privilege, and the questioning of assumptions and ‘truths’" (p.36 in Footnote 16). |

We explored whether and how studies demonstrated reflexive practices, namely if and how researchers acknowledged their own positions, their experiences of privilege, their underlying methodological assumptions or theoretical perspectives, and how the latter may be shaped by broader systems of power and social position experiences. |

| Time and space | Refers to the notion that "experiences and understandings of time and space are highly dependent upon when and where people live and interact in addition to their epistemological framesFootnote *, or ways of knowing, and the cultural frames of meaning they use to make sense of the world. […] Privileges and disadvantages, including intersecting identities and the processes that determine their value, change over time and place" (p.36 in Footnote 16). |

We assessed whether or how studies integrated, conceptually and analytically, notions of temporal or spatial variation of socio-political contexts, experiences, risks, or outcomes. |

| Diverse knowledges | Refers to intersectionality’s concern "with epistemologiesFootnote * (theories of knowledge) and power, and in particular, with the relationship between power and knowledge production. Including the perspectives and worldviews of people who are typically marginalized or excluded in the production of knowledge can work towards disrupting forces of power that are activated through the production of knowledge" (p. 37 in Footnote 16) |

The integration of the principle implies the acknowledgement and consideration of perspectives of diverse voices and communities. We assessed the integration of this principle by exploring whether works acknowledged knowledge produced through qualitative and quantitative research designs, whether populations who were affected by the inequalities under study were engaged in any component of the study design. |

| Social justice | Refers to the intersectionality’s concern for addressing inequities at their source, specifically by "transforming the way resources and relationships are produced and distributed so that all can live dignified lives in a way that is ecologically sustainable" (p. 38 in Footnote 16) |

We assessed whether and how studies integrated concepts of fairness, justice, advocacy, and the need for policy or systems change. |

| Equity | Refers to the preoccupation with fairness: "inequities exist where differences are unfair or unjust" (p.38 in Footnote 16). |

We assessed if and how studies conceptualized, measured, and described unjust and avoidable inequalities ("inequities" or "disparities") between population groups at the intersection of multiple positions and systems of power. |

|

||

We intentionally analyzed potential integration of the theory’s principles in each article section separately, rather than considering the application of the theory in the article as a whole. This was done for two reasons. First, we hypothesized that some studies might integrate principles of intersectionality theory in their rationale or interpretation sections, while failing to integrate those same principles in the analytic design (or vice versa) Footnote 23. Second, we hypothesized that within a study, the ways in which principles are integrated in each phase of the study may vary, and therefore provide insight into concrete ways to operationalize intersectionality principles from study conceptualization to completion. Applying such knowledge in future research and surveillance endeavors could be beneficial to avoid making the same mistakes and oversights as previous studies that have been criticized by scholars as failing to meaningfully incorporate all of the dimensions of intersectionality theory Footnote 19, Footnote 21, Footnote 24. Superficial applications of the theory can be appropriative if they neglect to acknowledge how transformative social change is required to address the intersecting systems of oppression that shape social and health inequalities Footnote 19, Footnote 21, Footnote 24.

3. Results

3.1 Description of studies

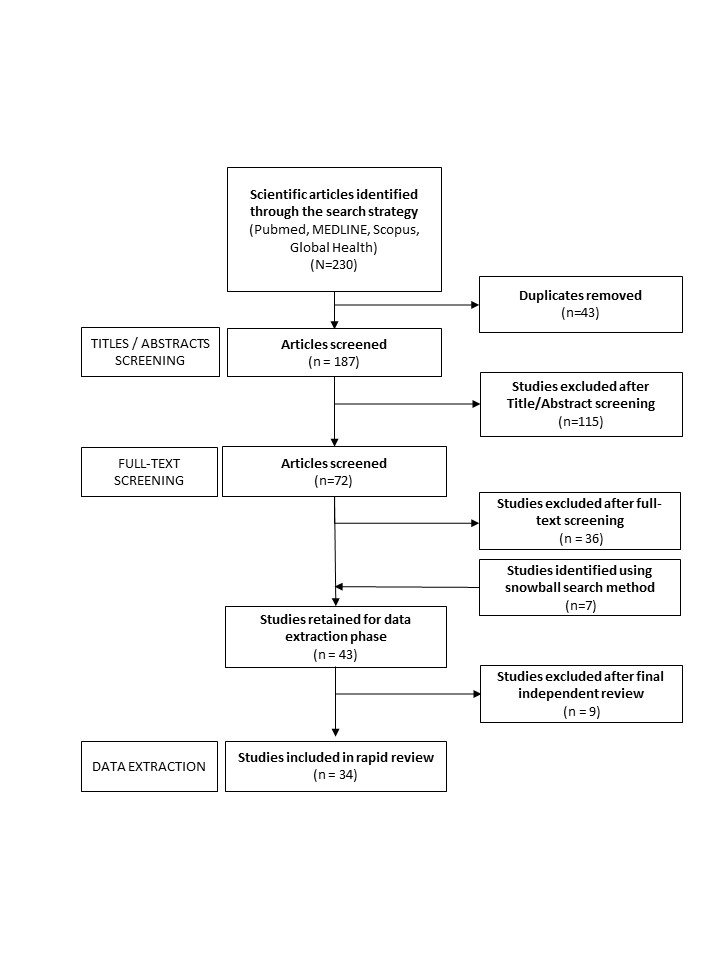

A total of 230 articles were identified using the search strategy described above. Of these, 34 met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1) (extracted results can be found in the Supplemental Material’s Section 7.2 Results: Data extraction). The main reasons for exclusion were: use of purely qualitative study design, use of one social stratifying measure rather than multiple, and a brief mention of intersectionality theory without an explicit aim of integrating the theory in the study.

a) Design and setting

Most studies (24 out of 34, 71%) used data from and were performed in the United States (US). Three studies were based in Canada (8%), including one study Footnote 53 that used data from both Canada and the US. Six papers (18%) used data gathered in Europe, including three in Sweden, one in Germany, one in Norway, and one that studied outcomes across 27 European countries. Only two of the included studies originated outside of Europe and North America. These used data gathered in India and Brazil, respectively.

Several studies explored outcomes in specific settings and contexts, namely schools (n=4, 12%) and health-related environments (n=3, 9%) such as long-term care facilities, maternity clinics, or sexual health centers. Almost half of the studies (n=14, 41%) studied outcomes in population sub-groups, such as individuals who inject drugs, pregnant individuals, mothers, students, sexual minority groups, individuals living with HIV or who consume alcohol). The other studies either explored outcomes in the general population as a whole, or age-specific general population sub-groups (youth, the elderly).

Out of 34 reviewed studies, a majority (n=31, 91%) used a cross-sectional observational design, while 3 (9%) used a longitudinal design. Of the latter, two studies used a mixed-methods design, integrating both qualitative and quantitative sources of dataFootnote 41,Footnote 42.

Figure 1 - Text description

Description: First, 230 articles were identified through PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus and Global Health databases. Of these, 43 were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 187 articles were screened for relevance. Of these 115 did not meet the review’s eligibility criteria, and therefore 72 articles remained. We reviewed the full text of these 72 articles to perform a more complete eligibility verification. Of these 72 studies, 36 articles were excluded. Reviewing the references of the studies, 7 additional relevant articles were identified. This provided 43 articles for final verification by an independent reviewer. At this stage, 9 studies were removed, because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. Thus, a final 34 studies were included in the review.

b) Conceptual framing and definitions

All studies provide some theoretical background of intersectionality. However, six studies (18%) do not explicitly articulate a definition of intersectionality theory. These were nonetheless included in the review, as they utilized the theory to develop their study objectives and design.

Of the 28 (82%) studies that did provide an explicit definition, five (15%)Footnote 41-Footnote 45 define the concept of "intersectionality" as referring to intersecting or interacting social identities or positions, which need to be analyzed concurrently rather than independently to capture the experiences of marginalized populations. The latter studies do not mention how intersecting social identities and experiences are related to or shaped by interlocking systems of power, oppression and privilege and/or by macro-, institutional or structural level factors. The remaining 23 studies (68% of all articles reviewed) provide a definition of intersectionality theory that integrates notions of interlocking systems of oppression, and how individual experiences are shaped by multi-level factors.

Almost all studies (n=33, 97%) reference key authors and seminal works of intersectionality theory, such as Kimberly W. Crenshaw—who first coined the term intersectionality in 1989 Footnote 12—Patricia H. Collins Footnote 13, Footnote 14, the Combahee River Collective Footnote 10 and Deborah K. King Footnote 56. Only one study did not reference any of the latter authors Footnote 57, but referenced instead other important contributors to intersectionality theory, such as Lisa Bowleg Footnote 6, Footnote 58 and Olena Hankivsky Footnote 16, Footnote 59–Footnote 61.

In addition to intersectionality theory, 18 of the reviewed studies (53%) introduced an additional framework or theory in their rationale, in combination with intersectionality theory. Several studies referenced health-specific theories related to systematic inequalities: four studies referenced Nancy Krieger’s Ecosocial theory Footnote 62; and two made reference to Link and Phelan’s Fundamental cause theory Footnote 63. Other frameworks or theories were referenced, many of which emerged from fields outside of health science research. Each appeared in only one of the studies, respectively. These included Chavis and Lee’s (1987) environmental justice theory and approach Footnote 64, Marmot and Bell (2012)’s proportionate universalism theory Footnote 65, the Identity Pathology framework Footnote 66, Feminist theory Footnote 67, Structural vulnerability theory Footnote 68, Syndemic theory Footnote 69, Discrimination theory Footnote 70, the Minority Stress Model Footnote 71, the Social Determinants of Health framework Footnote 2, and the Social Ecological model Footnote 72. Emerging out of fields of health research, including social epidemiology, many of the latter theories were utilized as a complement to intersectionality theory and its key principles, namely to provide additional theoretical background on the particular associations between the exposures and health outcomes under study.

c) Exposure and outcome measures

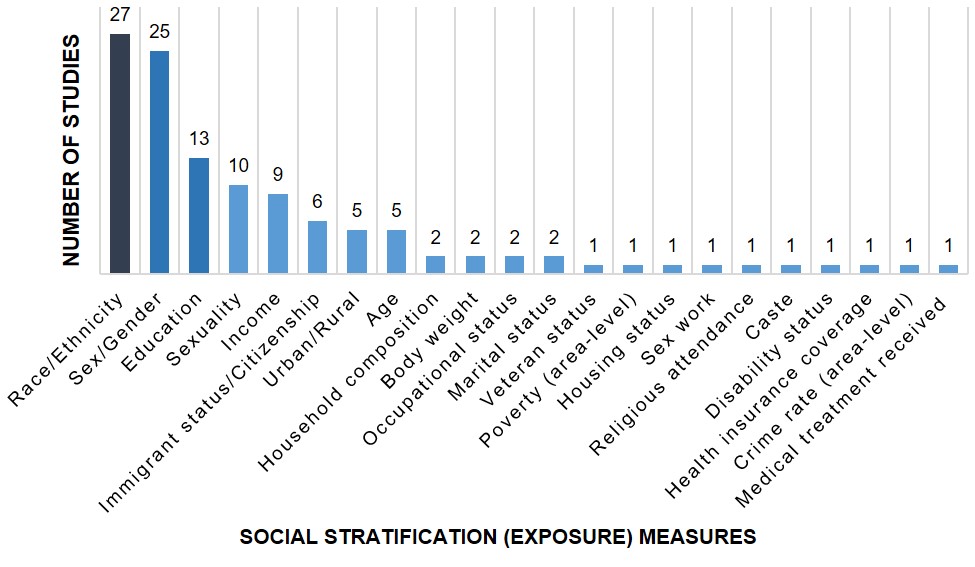

All studies included a minimum of two exposure measures, with the average study including 4 exposure measures. The most common social stratification measures used were those for race/ethnicity (79% of articles), followed by sex/gender (74%), educational attainment (38%), measures of sexual orientation and sexuality (29%), income (26%), immigration or citizenship status (18%), area of residence (urban/rural settings) (15%) and age (15%) (Figure 2). The three Canadian studies explored exposure measures of race/ethnicityFootnote 40,Footnote 60,Footnote 61, sexual or gender minority status Footnote 53, sexual orientation, partnership (marital) status, age, education, income, area of residence (urban, rural, suburban) Footnote 73, gender, and immigrant status Footnote 74.

The outcome (dependent) measures studied were varied. They included mental and physical health outcomes, health-related behaviours, as well as social conditions or experiences such as experience of discrimination, violence, incarceration, income level, or employment status or satisfaction. The most common outcome measures used were those pertaining to affective or mental health (29% of articles), self-reported health (15%) and smoking (12%) (Figure 3). The outcomes of interest in the three Canadian studies were: prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and asthma, as well as self-rated health Footnote 74; condom-less sex, substance use, suicidality, anxiety, and depression Footnote 73; and psychological distress Footnote 24.

Figure 2 - Text description

Description: This figure presents the social stratification or "exposure" measures that were used in the 34 studies. The horizontal axis describes the exposure measures, while the vertical axis describes the number of studies (n). Overall, 27 studies used exposure measures of race or ethnicity; 25 used measures of sex or gender; 13 studies used measures of educational attainment; 10 studies used measures of sexuality or sexual orientation; 9 studies used measures of income; 6 studies used measures of immigration status or citizenship. Five studies used, respectively, measures of urban residence and age. Two studies used, respectively, measures of household composition, body weight, occupational status, and marital status. Lastly, only one study used, respectively, measures of veteran status, poverty, housing status, sex worker status, caste, disability, health insurance coverage, area-level crime rate, and use of medical treatment.

| Social stratification (exposure) measure | Number of studies (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | 27 | 79 |

| Sex/Gender | 25 | 74 |

| Education | 13 | 38 |

| Sexuality | 10 | 29 |

| Income | 9 | 26 |

| Immigrant status/Citizenship | 6 | 18 |

| Urban/Rural | 5 | 15 |

| Age | 5 | 15 |

| Household composition | 2 | 6 |

| Body weight | 2 | 6 |

| Occupational status | 2 | 6 |

| Marital status | 2 | 6 |

| Veteran status | 1 | 3 |

| Poverty (area-level) | 1 | 3 |

| Housing status | 1 | 3 |

| Sex work | 1 | 3 |

| Religious attendance | 1 | 3 |

| Caste | 1 | 3 |

| Disability status | 1 | 3 |

| Health insurance coverage | 1 | 3 |

| Crime rate (area-level) | 1 | 3 |

| Medical treatment received | 1 | 3 |

Figure 3 - Text description

Description: This figure presents the dependent or "outcome" measures that were used in the 34 studies. The horizontal axis describes the outcome measures, while the vertical axis describes the number of studies (n). Overall, 10 studies used measures of mental health; 5 studies used measures of self-reported health; 4 studies used measures of smoking. Three studies used, respectively, measures of alcohol consumption, body mass index (BMI), or illicit substance use. Two studies used, respectively, measures of disordered eating, blood pressure, disability, discrimination, employment status, or pregnancy outcomes. Lastly, one study used, respectively, measures of cancer risk, diet, cholesterol levels, condom use, experiences of assault or violence, incarceration, income or wages, immunization status, health technology use, asthma, diabetes, heart disease or human immunodeficiency virus or "HIV" infection status.

| Dependent (Outcome) measures | Number of studies (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health | 10 | 29 |

| Self-reported health | 5 | 15 |

| Smoking | 4 | 12 |

| Alcohol consumption | 3 | 9 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 3 | 9 |

| Illicit substance use | 3 | 9 |

| Disordered eating | 2 | 6 |

| Blood pressure | 2 | 6 |

| Disability | 2 | 6 |

| Discrimination | 2 | 6 |

| Employment | 2 | 6 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | 2 | 6 |

| Sexual health screening | 1 | 3 |

| Cancer risk | 1 | 3 |

| Diet | 1 | 3 |

| Cholesterol | 1 | 3 |

| Condom use | 1 | 3 |

| Assault or violence | 1 | 3 |

| Incarceration | 1 | 3 |

| Income/Wages | 1 | 3 |

| Immunization | 1 | 3 |

| Health technology use | 1 | 3 |

| Asthma | 1 | 3 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 3 |

| Heart disease | 1 | 3 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status | 1 | 3 |

d) Scope of policy recommendations

Twenty two of the articles (64%) discussed the implications of their research for policy, and made policy recommendations. The most commonly recommended policy interventions were to improve access to culturally-safe and appropriate health care Footnote 54, Footnote 55, Footnote 75–Footnote 79 and to implement anti-discrimination policies, programs or interventions Footnote 24, Footnote 53, Footnote 73–Footnote 75.Additional policy directions included the implementation of anti-stigma initiatives Footnote 24, Footnote 75, Footnote 80, Footnote 81, namely through educational activities. Four studies recommended that existing public health programs be culturally adapted and targeted towards specific sub-populations that faced higher disease or outcome burdenFootnote 42,Footnote 67-Footnote 69. This is aligned with the two works that recommended a Proportional Universalism approach for public health intervention Footnote 80, Footnote 83. Other studies broadly recommended Intersectoral collaboration Footnote 84 and structural-level interventions Footnote 85, Footnote 86. Lastly, five studies made specific recommendations to address inequalities in social determinants of health, including improving financial security Footnote 84, working conditionsFootnote 44,Footnote 72, child care support Footnote 85, and pollution regulation Footnote 87. All studies also made recommendations regarding the direction of future analyses and research pertaining to the subject of study.

3.2 Integration of intersectionality in study rationale

Herein, the "rationale" section of articles refers to their Introduction or Background sections, including content on: background literature review (including the introduction of conceptual framework and theories) and research objectives and hypotheses.

On average, five of the eight principles were integrated in the rationale sections of the studies reviewed. Studies typically included between three to seven principles, with no study integrating all eight. One study Footnote 87 incorporated seven principles, while most incorporated 5 principles (mode=5).

The two most commonly integrated principles in the rationale of the 34 articles reviewed were principles of "intersecting categories" (100% of articles) and of "equity" (100% of articles) (Figure 4). This elevated coverage is likely due to the eligibility criteria applied for this review, which necessitated that included articles explore "joint or intersecting measures of social position or process" and "inequalities between two or more groups". In descending order, the other most commonly integrated principles in this section of the articles were elements of "multi-level analyses" (82% of articles), "power" (79% of articles), "social justice" (62% of articles), "time and space" (18% of articles), and "reflexivity" (12 % of articles). Two articles (<10%) integrated principles of "diverse knowledges" ( Figure 4).

A narrative summary of how these principles were integrated in the rationale sections is presented here, with a review of promising practices summarized in Table 4 below.

Figure 4 - Text description

Description: This figure presents the level of integration of each of the 8 principles of intersectionality theory in the three main sections of the 34 articles. The three main sections of the articles were the rationale, analytic design, and interpretation sections. The horizontal axis describes the 8 principles of intersectionality. These were: intersecting categories, multi-level analysis, power, reflexivity, time and space, diverse knowledges, social justice, and equity. The vertical axis describes the proportion of studies that integrated each principle.

For the principle of intersecting categories, 100% of studies integrated it in their rationale, analytic design, and interpretation sections, respectively. For the principle of multi-level analysis, 82 of studies integrated it in their rationale and interpretation sections, respectively, while 21% integrated in their analytic design. For the principle of power, 79% of studies integrated it in their rationale, 15% integrated it in their analytic design, 68% integrated it in their interpretation sections. For the principle of reflexivity, 12% of studies integrated it in their rationale, 24% integrated it in their analytic design, 29% integrated it in their interpretation sections. For the principle of time and space, 18% of studies integrated it in their rationale, 24% integrated it in their analytic design, 41% integrated it in their interpretation sections. For the principle of diverse knowledges, 6% of studies integrated it in their rationale and analytic design, respectively, and 21% integrated it in their interpretation sections. For the principle of social justice, 62% of studies integrated it in their rationale, 12% integrated it in their analytic design, and 50% integrated it in their interpretation sections. For the equity, 100% of studies integrated it in their rationale, analytic design, and interpretation sections, respectively.

| Key principles of intersectionality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intersecting Categories | Multi-level Analysis | Power | Reflexivity | Time and Space | Diverse Knowledges | Social Justice | Equity | |

| Article sections | Percent (%) of studies integrating each principle | |||||||

| Rationale | 100 | 82 | 79 | 12 | 18 | 6 | 62 | 100 |

| Analytic design | 100 | 21 | 15 | 24 | 24 | 6 | 12 | 100 |

| Intepretation | 100 | 82 | 68 | 29 | 41 | 21 | 50 | 100 |

a) Intersecting categories

Background literature review

In their background literature review, two studies Footnote 53, Footnote 88 described the differences between intra- and inter-categorical intersectionality analysis. They refer to these concepts to explain the importance of the use of multiple categorical measures to study the experience of groups at each of the intersections of various social positions, thereby integrating the principle of intersecting categories.

Objectives

A majority of studies (n=25, 74%), integrated this principle in their study questions and objectives. Though formulations varied, the objectives were generally to explore differences in experiences between groups or explore effect measure modification between two or more social stratification measures. For example, studies aimed to:

- Assess outcomes across groups, as defined by two or more social identities or positions;

- Assess how two or more social identities jointly influence a health or social outcome;

- Assess the potential effect modification of a certain social identity or position, on the association between another social stratification measure and an outcome.

The epidemiologic concept of effect measure modification was particularly common across the reviewed studies, although it was not always described using that terminology. For example, three studiesFootnote 44,Footnote 62,Footnote 74 framed their objectives using alternative wording such as:

- To explore whether the combined effect of social identities and positions is different (larger, smaller) than the sum of the individual effects of each identity on the outcome of interest;

- To explore how social positions or identities interact to influence inequalities in outcomes across sub-groups.

b) Multi-level analysis

Background literature review

The 28 studies that integrated the principle of multi-level analysis in the literature summary of their rationale, did so by referring to the multi-level factors (e.g., from the individual, to community and society level) that shape health and health inequalities (e.g., Footnote 79) and by introducing the notion of structures and systems of power that operate above the individual-level, to shape individual-level experiences, identities, and positions when defining intersectionality theory (e.g., Footnote 80). As mentioned above, five studies also integrated complementary theoretical frameworks (e.g., Footnote 89), such as Ecosocial theory or social-ecological models, which posit that individual-level experiences are shaped by multi-level determinants.

Objectives

In five studies (14%), objectives were framed as aiming to achieve a better understanding of how individual-level experiences are shaped by contextual- or structural-level determinants, thus integrating the principle of multi-level analysis. For instance, one study Footnote 90 considered individual-level social position makers such as race, class, and gender, as well as context characteristics of schools (e.g., school poverty status, measured in relation to the incomes of students’ household) and neighborhoods (e.g., neighbourhood poverty status), in determining the outcome of adolescent cigarette use. The objective was framed as follows:

- To examine how individual-level social positions and identities interact with contextual characteristics to produce variation in an outcome across a population

Two studies Footnote 87, Footnote 91 aimed to study the characteristics of neighborhoods and their independent relationships with health outcomes. Formulations of study objectives included:

-

A. To assess potential interaction between area (neighbourhood) level characteristics and their association with population health and health inequalities; and

B. To identify areas that are particularly vulnerable to experiencing the health outcome;

- To assess the extent to which contextual measures explain differences in outcomes across groups above and beyond individual-level measures.

c) Power

Background literature review

The seven studies that did not integrate the principle of power in their rationale section were those that introduced intersectionality theory solely by presenting how individual experiences are shaped by the intersections of various social identities or positions without reference to interlocking systems of power, oppression or privilege shaping those individual-level experiences. The remaining studies referred to the role that systems of power, oppression and privilege play in shaping health or social outcomes.

Objectives

At least two studies integrated the principle of power when introducing their study objectives Footnote 77, Footnote 84. For example, one study Footnote 84 aimed to:

- Examine health inequalities across social stratification measures that capture groups’ relative affluence, social standing and power (e.g., gender, income level);

- Better understand the health inequalities between groups with relatively more power (dominant groups) and those with relatively less power (subordinate groups), by performing a decomposition analysis that determines the relative contribution of various social and economic measures to the observed inequality.

d) Reflexivity

Background literature review

As mentioned in Section 3.1b, all of the studies acknowledged the underlying intersectional theoretical framing of their study, and provide some theoretical background on intersectionality. In addition to this, one study integrated the principle of reflexivity in their background literature review by acknowledging how all analyses are underpinned by underlying assumptions and values, even if these are not made visible Footnote 86. The study noted the importance of the reflexive practice of referencing underlying theories to note underlying assumptions Footnote 86. In another study, authors’ described their theoretical positionality at the outset of the work. They note how their proposed research is "position[ed] within intersectionality, environmental justice and the social determinants of health" literatures Footnote 87. The incorporation of critical theoretical frameworks, that emerged from multidisciplinary backgrounds, including but not limited to intersectionality theory, has been identified as an important future direction for quantitative health research Footnote 8.

Objectives

Two studies were identified as having integrated the principle of reflexivity when they described their research questions and hypotheses. In one study, authors specified that they aimed to identify subpopulations that face the highest disease burden Footnote 73. Referring to Hankivsky’s theorizing Footnote 61, the authors note that "intersectionality suggests that the significance of any given factor, or set of factors should not be predetermined but rather inductively revealed through the research process (Hankivsky, 2012)" (p.510-511 in Footnote 61). Guided by this underlying assumption, the authors explain that they did not aim to test a specific hypothesis as to which particular sub-group studied may experience greatest outcome burden, according to "multiple axes of sexual identity, relationship status, age, education, income, ethnicity, and living environment" (p.510 in Footnote 60).

Similarly, in another study Footnote 82, authors acknowledged how standard epidemiologic analyses of health inequalities based on comparisons between sub-groups and a standard reference category may "reinforce notions of a default, or standard, identity". They give the example of comparing non-white groups to white populations, and how this can "reinforce the culturally-laden value judgments such as the idea that White (or other privileged groups) are the norm to whom others should be compared" (p.2619 in Footnote 64) (see Box 3). Reflecting on these underlying methodological assumptions, the authors specified that their objective was to compare sub-group populations’ outcomes to a sample average.

Box 3: The use of reference groups in past HIRI reporting

Past HIRI data analysis and reporting Footnote 1 has been mindful of the potential risks of centering white or dominant group experiences by using these groups as reference groups for health inequality analyses. However, driven by a similar principle of reflexivity, HIRI chose to use reference groups (rather than population averages, for example). Chosen reference categories were based on understandings and assumptions of which groups tend to experience greater access to health promoting social and economic resources. Comparisons in relation to these dominant groups were interpreted as indications of unfair and potentially avoidable gaps in health promotion and prevention across populations.

e) Space and time

Background literature review

Five studies were identified as having integrated the principle of space and time in their background literature reviews. These studies summarized existing literature’s understanding of the determinants of spatial and temporal changes in health outcomes and health inequalities. Integrating notions that privileges or disadvantages can change over time Footnote 16, two studies discussed how experiences and determinants of health can vary or accumulate throughout the lifecourse, to shape health risks Footnote 76, Footnote 83. The lifecourse perspective requires a consideration of temporal concepts such as calendar time, birth cohorts, and age. Another study highlighted the role of historical and spatial secular shifts in exposures (e.g., levels of immunization), and how these variations in contexts shape population health and health inequalities Footnote 77.

Touching on the concept of space, one study described how systems of oppression can operate differently across local contexts Footnote 92. Another study described the role of neighbourhood-level exposures in shaping individual-level health risks Footnote 87.

Objectives

Three studies were identified as having integrated the principles of space and time when setting their research objectivesFootnote 41,Footnote 63,Footnote 64. These studies aimed to investigate spatial and/or temporal variations in health outcomes and health inequalities through time. For example, objectives specified in these studies, included:

- To assess trends in the prevalence or distribution of social identities or outcomes across space and time;

- To assess changes in the association between identified social identities and outcomes over time and across areas;

- To assess whether or how determinants interact to change outcomes over time.

f) Diverse knowledges

Objectives

Two studies (6% of articles reviewed) were identified as having integrated the principle of diverse knowledges when setting their study’s objectives. Both of these studies aimed to apply a mixed-methods design to explore the first-person perspectives and perceived experiences of specific populations, namely people who inject drugs Footnote 81 and pregnant Latina individuals Footnote 54, based on their other social positions, identities or contexts. For example, Morris et al. Footnote 54 aimed to explore the birth experiences of women, across categories of ethnicity and the region of giving birth. However, neither study indicated whether vulnerable populations were engaged in the definition of the research questions, study design, development of data collection instruments, analysis, interpretation of data, and knowledge mobilization.

g) Social justice

Background literature review