Vision 2030: Moving data to public health action

Download in PDF format

(7,111 KB, 54 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date Published: February 2025

Related links

Table of contents

- Land acknowledgement

- Foreword

- Executive summary

- Section 1. Background

- Section 2. A vision for public health surveillance

- Section 3. Opportunities for action

- Opportunity 1: Develop governance frameworks

- Opportunity 2: Enhance surveillance systems by integrating social determinants of health

- Opportunity 3: Foster collaboration and build trust with communities

- Opportunity 4: Create the conditions to implement First Nations, Inuit, and Métis health data sovereignty

- Opportunity 5: Enhance the capacity to conduct surveillance in a manner that values, strengthens, and incorporates First Nations, Inuit, and Métis knowledge and skills in public health assessment and response

- Opportunity 6: Invest in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis health information systems, infrastructure, and indicators

- Opportunity 7: Support workforce development

- Opportunity 8: Promote interoperability through data standards

- Opportunity 9: Review mechanisms for data sharing and linkage

- Opportunity 10: Modernize data infrastructure

- Working toward 2030

- Appendix 1: Methodology

- Appendix 2: Challenges

- Challenge 1: Purpose and governance of surveillance

- Challenge 2: Partnerships, collaboration, and engagement

- Challenge 3: Build respectful partnerships with First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people, communities, and organizations

- Challenge 4: Workforce competencies, training, and resources

- Challenge 5: Data quality, access, and use

- Challenge 6: Strategic use of technology, tools, platforms, and methods

- Abbreviations and acronyms

- Glossary

- Acknowledgements

- References

Land acknowledgement

We respectfully acknowledge that the lands on which we developed this report are traditional First Nations, Inuit, and Métis territories. We acknowledge the diverse colonial histories and cultures of the First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people upon whose traditional lands we reside and work. We strive for respectful partnerships with Indigenous Peoples as we search for collective healing, truth, and reconciliation. Specifically, this report was developed in Toronto, on the traditional territories of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation; in Winnipeg, on the traditional territories of the Anishinaabe (Ojibway), Ininew (Cree), Anishininew (Ojibway-Cree), Dené, and Dakota peoples, and the National Homeland of the Red River Métis; in Montréal, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Mohawk (Kanien'kehá:ka) Nation; and in Ottawa, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishnaabe people. Additionally, this report was shaped through consultations held across the ancestral lands traditionally occupied and used by many Indigenous Nations. We invite readers to pause and reflect upon the history of these lands, and to honour the ongoing connections that Indigenous Peoples have with these traditional and treaty territories.

Foreword

With great optimism and respect for the strong foundations already in place, we are pleased to share a vision for public health surveillance in Canada by 2030. This vision reflects input from approximately 1,800 participants across the country, guidance provided by an expert roundtable, as well as input from many professionals working at the Public Health Agency of Canada and partner organizations. In the context of other efforts aimed at improving public health in Canada, this vision aims to provide a shared understanding of the goals and challenges of public health surveillance and to highlight initiatives led by partners across Canada that are moving surveillance toward the vision.

We heard clearly in our consultations the importance of public health surveillance and its associated public health action being rooted in science and considering the specific needs and circumstances of communities and populations. We also heard that public health surveillance should do its utmost to embrace new technologies and tools for cross-sectoral collaboration, continue to leverage scientific knowledge and evidence for public health decision-making, support efforts to address inequities in the social determinants of health (including the impacts of racism and systemic discrimination), and value and incorporate Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing into surveillance practice to ensure that public health surveillance accurately reflects and supports the diverse health stories and contexts of the peoples it is meant to serve. In this regard, we heard the importance of conceptualizing surveillance as a deliberate act of caretaking rather than merely a technical process. Viewed in this way, surveillance can be an essential support for communities across the country to understand and shape their own health journeys, build from existing strengths, and inform meaningful public health action.

Central to Vision 2030 is a surveillance 'system of systems'—a coordinated collection of surveillance systems and programs that provide information about the same population for the purpose of informing public health action. This 'system of systems' is intended to be agile, resilient, adaptable, and informed by those that use and are impacted by public health information to ensure that the data being collected are accurate and representative. This vision acknowledges that partners at all levels—including federal, provincial, territorial, Indigenous partners, local, and non-government organizations—can make progress toward improved public health surveillance in Canada, and most importantly, contribute to our shared goal of protecting and promoting the health of peoples residing in Canada.

We extend our deepest gratitude to all those who contributed to the development of this vision, including those who participated in the in-person and virtual consultations, as well as members of the public who completed the online survey. Your perspectives and experiences have enriched this vision with essential evidence and insights gained through working at the heart of public health surveillance across the country. We look forward to continuing to work together toward the directions outlined in this vision, and to build from the many successes and innovations that already exist at all levels of the public health system in Canada.

Dr. Theresa Tam, Chief Public Health Officer of Canada;

Heather Jeffrey, President, Public Health Agency of Canada;

Dr. Sarah Viehbeck, Chief Science Officer and Vice-President of Data, Surveillance & Foresight Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada;

Dr. David Buckeridge, Executive Scientific Director, Data, Surveillance & Foresight Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada

Executive summary

Public health surveillance involves the collection, analysis, interpretation, and sharing of health-related data to support public health decisions and actions. This essential function enables public health organizations to safeguard the health and safety of people residing in Canada by detecting emerging threats, guiding appropriate responses, and informing prevention strategies. In Canada, public health surveillance systems are operated at every level of government, with varying degrees of coordination across the numerous diseases, conditions, and risk factors being monitored to inform public health action. In recent years, public health in Canada has been challenged by crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, opioid toxicity, and climate change, highlighting the importance of a shared vision for public health surveillance to align efforts and better prepare for future threats. With broad input from public health partners across the country and members of the public, the Public Health Agency of Canada has developed a collaborative vision for public health surveillance in Canada by 2030. This report is intended for public health professionals and policymakers involved in public health surveillance, as well as their collaborating partners. It may also be of value to readers interested in understanding the challenges and opportunities in public health surveillance in Canada.

Vision 2030 sees an adaptable and collaborative public health surveillance 'system of systems' able to provide timely insights for actions that improve health and reduce inequities for all people in Canada. It describes the desired states and the characteristics of a high-functioning public health surveillance 'system of systems', including clear purpose and governance, inclusive partnerships, a well-supported workforce, integrated health information, and operational efficiency. This report also highlights several existing initiatives by public health partners to address persistent challenges communicated by public health practitioners across the country. These opportunities for action are meant to reflect concrete areas where improvement would address challenges that have been observed, and the identified opportunities are accompanied by illustrative examples of actions already underway. To this end, the vision identified opportunities for: governance structures that enable authorized access to high-quality, timely surveillance data; strengthening relationships between public health surveillance partners and the communities they serve; supporting Indigenous data sovereignty and the development of culturally relevant and resourced health systems; creating a well-equipped workforce; and, modernizing data and data-sharing infrastructure. Through progress on these opportunities for action, advances can be made toward a resilient public health surveillance 'system of systems' capable of informing public health action in the context of the evolving public health needs of people residing in Canada.

Vision 2030 invites everyone involved in public health surveillance in Canada to consider the directions outlined in this report, including the opportunities for action, considering their own context, priorities and resources. Together, all actors in the 'system of systems' can work towards a healthier and more equitable future for everyone in Canada.

Learn more:

Section 1. Background

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) defines public health surveillance as "the ongoing collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of health data for the purpose of planning, implementing, and evaluating interventions to protect and improve the health of populations" Footnote 1. Surveillance is an essential public health function Footnote 2 and one of PHAC's four science priorities enhancing the ability to act on health threats and generating observational evidence to inform strategies and programs. Strong surveillance systems help to anticipate challenges, support equity-informed solutions, and guide public health decision-making that impacts millions of people, in addition to enabling rigorous research. They support not only responses to public health emergencies, but also provide the information that allows long-term strategic planning in public health to fulfill its mission of protecting the health of people and promoting well-being across Canada. This data-driven planning ensures that public health efforts are not only reactive but also proactive, helping to build a healthier future for everyone.

Reflecting on the term 'surveillance'

In discussing the future of public health surveillance, it is important to recognize the varied interpretations of the term 'surveillance'. While many public health professionals understand it as an essential public health function that informs public health action, for some, the term has negative connotations, suggesting intrusive or involuntary monitoring or even 'mass surveillance' programs that infringe on privacy rights Footnote 3 Footnote 4. Historically, 'surveillance' was linked to injustices against First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people, often under the guise of public health objectives Footnote 3 Footnote 4. Recognizing this history, some public health professionals use alternative terms. For example, a recent report on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis population health used "assessment of and response to [well-being]" to emphasize the close connection between knowledge generation and its application in Indigenous paradigms Footnote 3. Similarly, the term 'public health assessment' was used in the Vision 2030 consultations with the general public Footnote 5, recognizing that there is limited public awareness of the technical meaning of 'surveillance' in public health. In the absence of a more widely accepted term, 'public health surveillance' was used throughout the report due to its widespread use in the published literature and by public health organizations globally. However, it is recognized that readers of this report may wish to use different terms in the context of the communities they serve.

Public health surveillance in Canada

Canada does not have a single, unified public health surveillance system. Instead, local, provincial, territorial, federal, Indigenous, and non-governmental public health organizations operate numerous independent surveillance systems with varying degrees of connectivity between them in keeping with factors such as their respective objectives, legislation, data availability, and the context in which data is collected. Some of these systems, like notifiable disease reporting to the federal government, have been in place for a century, beginning in 1924 Footnote 6.

Established in 2004 after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, PHAC leads national surveillance with support from many partners at other levels of government and other organizations, such as the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 9 Footnote 10. PHAC also operates the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML)—Canada's only Containment Level 4 laboratory for human health—to advance infectious disease surveillance and provide reference laboratory services to identify or confirm diseases other laboratories may not be able to detect or diagnose. Many other federal departments also perform health surveillance activities; for example, Statistics Canada conducts health surveys, Health Canada regulates and monitors post-market safety of specific products and controlled substances, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency contributes to food safety and animal health.

Provinces and territories are responsible for most healthcare delivery and front-line public health services, and generally are stewards of health-related data. Provincial and territorial public health authorities set public health standards and reporting requirements within their respective jurisdictions, and operate surveillance systems and public health laboratories. Provincial and territorial governments enable national-level reporting by providing data for over half of PHAC's surveillance systems (as of March 2024).

Local and regional public health authorities are the backbone of the public health systems in Canada, delivering services such as immunizations and leading the investigation and reporting of infectious diseases and adverse events following immunization. They also contribute to routine surveillance of issues like water quality, environmental hazards, child and maternal health, addiction, and non-communicable disease and injury prevention. There are many other public health surveillance partners in Canada beyond local health authorities and federal, provincial, and territorial (FPT) governments. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis organizations, such as the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) and Qanuippitaa? National Inuit Health Survey, play a crucial role in defining, collecting, and contextualizing data to improve Indigenous health. Collaborations with academia, the private sector, community organizations, and local healthcare systems are essential for advancing the science underpinning surveillance by developing innovative and culturally relevant methods and tools, as well as producing knowledge to inform public health action.

Canada upholds its commitments under the International Health Regulations through ongoing surveillance activities Footnote 11. Through PHAC and other organizations, Canada shares information, best practices, and resources to support the monitoring of issues including infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, injuries, vaccine coverage and safety, and climate change impacts, in collaboration with partners like the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Surveillance has evolved

Public health surveillance systems in Canada have long been a cornerstone of the country's ability to monitor and respond to health threats. Public health surveillance has evolved significantly in the past decades, transforming how surveillance is conducted, what is measured, and how data are analyzed and communicated Footnote 12. This also includes efforts in advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples to own, control, access and possess information about their peoples, such as the FNIGC principles of OCAP®(Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession) Footnote 13. Public health surveillance in Canada will continue to change in response to the constantly shifting public health landscape. The scope of surveillance has expanded to include concerns such as mental health, substance use, and climate change impacts with a growing focus on the interconnectedness of health dimensions, the different experiences of health outcomes across population groups, and the impact of intersecting social and other determinants of health. This evolution in focus has driven a shift from surveillance of single-topics or diseases to more linked and interconnected systems better able to capture the cross-cutting issue of health inequities. Access to information with unprecedented speed and volume has increased expectations for transparency and timeliness among partners and the public. This change has led to efforts to shift information dissemination from dense technical reports toward more streamlined, interactive visualizations (such as those available on Health Infobase Footnote 14) and health messages that are accessible to both technical audiences and the public.

Technological advances have also changed how surveillance is conducted. Improved access and linkage of electronic health records and health administrative databases allow for enhanced analysis of factors unavailable from existing syndromic and chronic disease surveillance, improving insight and understanding of national trends. Genomic sequencing has become a standard practice in infectious disease monitoring, offering valuable insights into pathogen evolution, transmission dynamics, antimicrobial resistance, and informing vaccine development and targeted public health interventions. The 'big data' from social media, personal 'smart' devices, and other sources may now be analyzed using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, offering new opportunities for early detection and response to emerging health threats. New global frameworks and technologies are transforming international data sharing and real-time global analysis to enhance global health and biosecurity Footnote 15.

Recent developments in public health surveillance in Canada

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted the creation of new surveillance systems to monitor cases, outbreaks, and vaccine-related data, requiring extensive collaboration among federal, provincial, territorial, and Indigenous (FPTI) public health partners. Initiatives like VaccineConnect aimed to centralize vaccine supply chain and safety data Footnote 16. These systems faced challenges such as issues with technical infrastructure and data sharing agreements that led to difficulties in sharing vaccine data with domestic and international partners Footnote 17 Footnote 18. Some surveillance methodologies were the subject of rapid innovation and widespread adoption; for example, by early 2024 the Pan-Canadian Wastewater Monitoring Network had expanded to cover most of the sewer-connected population, collecting not only data on SARS-CoV-2 but also additional viral pathogens including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza, and mpox, with substance use markers and antimicrobial resistance also being monitored Footnote 19. Another example is serological surveillance, which was implemented rapidly in a pan-Canadian context for SARS-Cov-2 by the Canadian Immunity Task Force (CITF) with the support of blood operators and provincial labs, who analyzed residual blood samples and provided seroprevalence results to the CITF for further analysis and communication with public health decision makers Footnote 20. The pandemic also spurred disaggregated data collection to support an equity-informed view of surveillance. Efforts were made to gather and use information on the social determinants of health, particularly on race, ethnicity and Indigenous identity (as proxies for assessing potential experiences and impacts of racialization and structural racism), as part of the pandemic response. While this represents long desired progress, more work is needed to standardize and fully integrate data on the social and other determinants of health into public health surveillance and decision-making Footnote 21 Footnote 22 Footnote 23 Footnote 24.

Approach to developing Vision 2030

In early 2023, PHAC launched Vision 2030, an initiative to develop a shared picture of public health surveillance in Canada by the year 2030 and identify opportunities to address longstanding issues to move public health surveillance toward this vision Footnote 1 Footnote 5. An extensive consultation process was carried out between September 2023 and March 2024, which included meetings with a Surveillance Expert Round Table (SERT), domestic and international public health professionals and experts, academics, partners in governmental and non-governmental organizations, Indigenous Peoples and communities, and members of the public (see Appendix 1: Methodology for more details).

The objectives of Vision 2030 were to:

- summarize the key challenges that must be addressed to improve public health surveillance;

- articulate a vision statement and desired states for public health surveillance by 2030;

- describe the characteristics of a high-functioning public health surveillance 'system of systems'; and,

- identify opportunities for action, based on science, evidence, and real-world examples, that will help public health surveillance partners align efforts to move toward this vision.

Through these objectives, Vision 2030 sought to develop a common understanding of the goals and challenges of public health surveillance to help align efforts across the decentralized public health surveillance systems in Canada and support continued relevance and responsiveness to public health threats. This vision aims to address longstanding challenges while also looking beyond the day-to-day obstacles to conceptualize public health surveillance in a way that incorporates new kinds of evidence, ways of thinking, and modes of governance into this foundational element of public health practice. It is intended to offer guidance to all partners in public health surveillance, from coast-to-coast-to-coast, from the local to national level, within and outside government, and is inclusive of people residing in remote/rural areas to dense urban centres in Canada.

Section 2. A vision for public health surveillance

The vision for public health surveillance in Canada by 2030 is an adaptable and collaborative public health surveillance 'system of systems' able to provide timely insights for actions that improve health and reduce inequities for all people in Canada. This vision includes a future where surveillance programs in Canada have the data that they need to achieve a comprehensive understanding of population health and can appropriately monitor health trends, guide action, and prepare for potential threats. Central to this vision is the concept of a coordinated 'system of systems' with "independently operated sub-systems networked together for a common goal" Footnote 25. This approach acknowledges the need for individual surveillance programs to control their own systems and data while aligning the governance, technical, and operational aspects of systems across organizations to enable sharing of data and insights where appropriate to inform action. It emphasizes the need to overcome technical, human, and organizational barriers to enable effective collaboration across the diverse and necessarily independent entities that conduct surveillance in Canada.

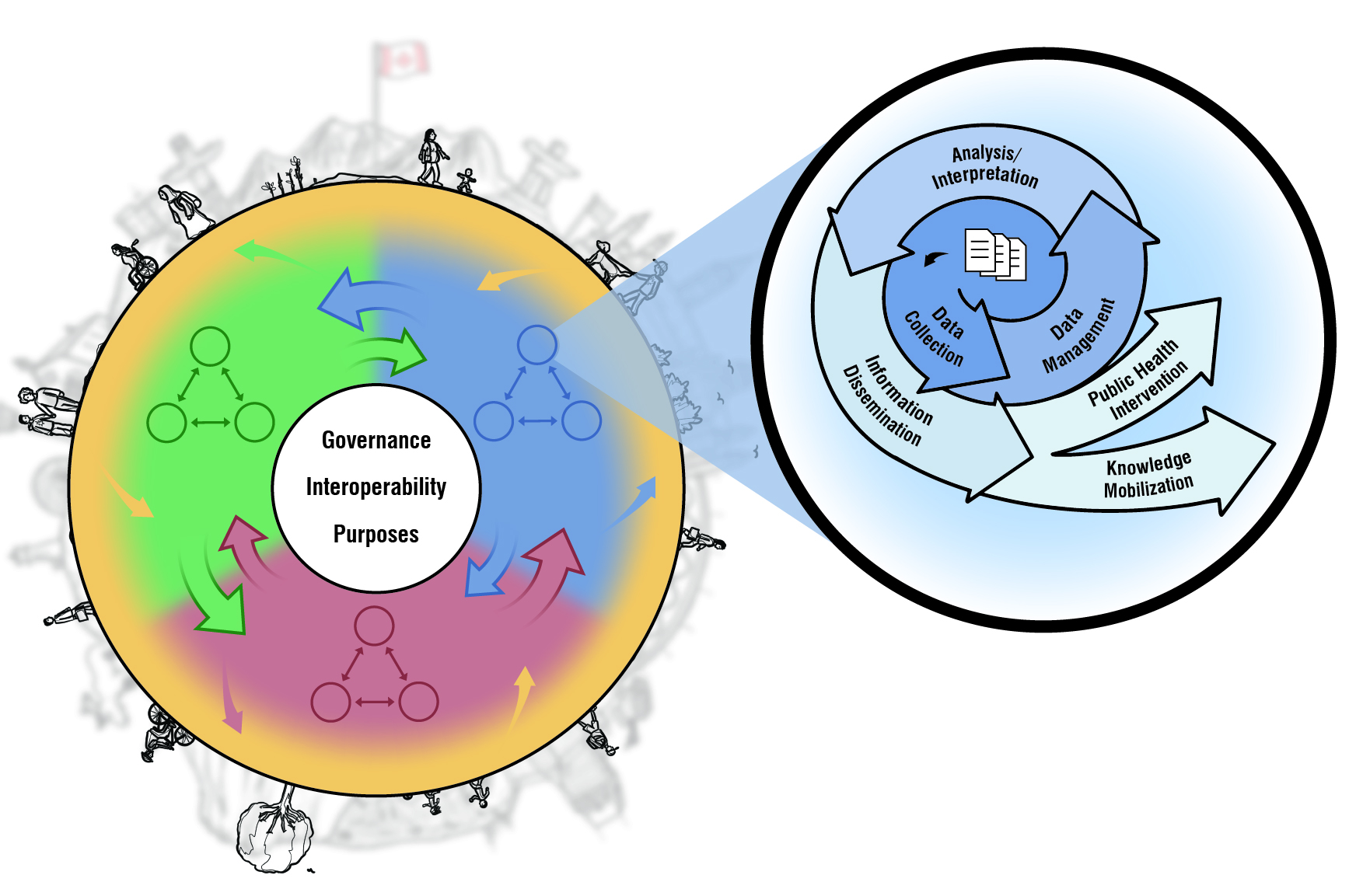

Text equivalent

This diagram aims to demonstrate how independently operated surveillance systems and programs could exchange data and information within and between levels of government and other partners, under a unified governance, to provide timely insights for actions that improve health and reduce inequities for all people in Canada.

Starting on the left, the inner white circle lists governance, interoperability and purposes as the core of 'system of systems'. The red, blue and green areas represent different levels of government and other partners that conduct public health surveillance in Canada, such as federal, provincial, territorial, Indigenous, local/regional, and non-governmental organizations. The yellow ring symbolizes the communities and people from whom data are collected and to whom information is returned.

Each solid-coloured circle within the red, blue and green shaded areas represents an independently operated surveillance system which involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, followed by the sharing of health-related information to support public health decisions and actions, as illustrated in the zoom-in diagram on the right. These same-sized circles signify the common data standards and processes.

The arrows demonstrate the data and information flow between systems, and how they lead to public health intervention and knowledge mobilization to support all people in Canada where the data were originally collected from.

Desired states

Across the consultations, several themes emerged that reflect dimensions which public health professionals saw as integral to understanding, and ultimately giving effect, to this vision. In other words, these desired states reflect aspirational conditions that participants saw as integral to Vision 2030:

- Unified purpose and governance: A public health surveillance 'system of systems' has a clear purpose for each system and the collection of systems is supported by robust and widely understood governance so that all partners have clear roles and authorized access to high-quality surveillance data to inform public health action.

- Inclusive partnerships: Equity-deserving groups and Indigenous rights-holders, are active partners in the development, management, maintenance, and use of information and evidence generated by public health surveillance systems to meet the diverse needs of these groups and to build trust.

- Well-supported workforce: The public health workforce is equipped to meet evolving public health demands including the ability to establish inclusive partnerships, the ability to interface between different technical systems and cultural paradigms, and apply appropriate methods and technologies to data and information to understand and advance health equity.

- Integrated health information: Health information is securely shared between surveillance systems in a coordinated, interoperable, and reciprocal manner so that surveillance platforms and partners can integrate and analyze sufficiently granular data to generate actionable insights about public health.

- Operational efficiency: Efficient surveillance processes maximize the appropriate use of data infrastructure and technologies to enable timely, high-quality data management and analysis while limiting the need for repetitive human tasks.

Characteristics

As the desired states present the conditions that the vision aims to achieve, characteristics refer to the defining qualities or attributes that shape the overall 'system of systems' in public health surveillance. With good governance, interoperability and purposes at the core of 'system of systems', these characteristics highlight how individual systems function independently and interoperate across multiple levels of government to build an effective, equity-informed, and trust-based public health surveillance system in Canada (Figure 1). To realize this vision, six key characteristics have been identified (Figure 2).

Text equivalent

System of Systems Characteristics

Agile: Adapt swiftly to emerging public health issues by routinely assessing system effectiveness to improve performance and fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement.

Collaborative: Design and operate public health surveillance systems collaboratively by engaging multidisciplinary partners, aligning goals, leveraging expertise, communicating the purpose and use of data and information, and fostering shared values.

Connected: Develop surveillance systems to be interoperable so that data, tools, methods, and information can be shared securely and rapidly across connected systems.

Coordinated: Organize people, expertise, information and training across jurisdictions and organizations to work together toward shared objectives.

Equitable: Embed equity throughout surveillance systems by fostering representation, promoting the routine production and access to disaggregated data, routinely accounting for determinants of health, incorporating culturally sensitive practices.

High quality: Use diverse, reliable data sources, and employ appropriate methods to generate and interpret data to accurately reflect the impacts of public health issues on population groups

Section 3. Opportunities for action

Many innovative surveillance examples were identified through consultations and other sources, and through a consensus-building process, SERT members highlighted from these examples ten actionable opportunities for making progress against persistent challenges in public health surveillance. These highlighted examples do not fully represent the existing strengths and ongoing innovations in Canadian public health surveillance (see Appendix 1: Methodology for more details), but rather illustrate feasible and impactful ways to make progress toward Vision 2030. These opportunities also address the identified challenges (see Appendix 2: Challenges) and generate continued momentum to realize this collaborative vision for public health surveillance in Canada. The relationships between opportunities and challenges are generally not one-to-one (as illustrated in the infographic). Most opportunities could address more than one challenge, highlighting the interconnectedness of the challenges and the potential actions to address them.

To demonstrate the concrete actions associated with each opportunity, relevant context is provided and recent pioneering work by partners across the country in advancing these areas is showcased.

Opportunity 1: Develop governance frameworks

Develop and share governance frameworks, including example data sharing agreements, which can be adapted by surveillance programs to clearly describe roles and alignment with public health goals.

Effective public health surveillance relies on coordination among public health practitioners, healthcare providers, and other partners. Governance structures should begin with a clear purpose and specific goals and define roles and responsibilities of all surveillance partners. Embedding equity as a core purpose in public health surveillance creates opportunities for more inclusive decision-making and better representation, and strengthen approaches to protecting and improving health. Early engagement of key stakeholders in the development of standardized governance frameworks can make it easier to reduce fragmentation, address redundancies, and build buy-in. These benefits of early engagement will support movement towards a surveillance 'system of systems', which will improve how various systems interact with the goal of protecting the health of the people and communities they serve.

Example

The opioid toxicity crisis helped call attention to the need for national standards in death investigations Footnote 26 Footnote 27, as thorough and timely data regarding substance-related deaths are crucial for informing interventions to reduce mortality Footnote 26. The Chief Coroners, Chief Medical Examiners, and Public Health Collaborative provide collaborative governance uniting provincial and territorial coroners and medical examiners, PHAC, and Statistics Canada to advance priority public health issues. This group develops data standards for mortality data on topics such as toxic drug deaths and suicides, and establishes common protocols and agreements with Statistics Canada to enhance data infrastructure systems that meet public health information needs. This governance model could be used to address other priorities such as violence- and climate-related fatalities Footnote 26 Footnote 28 Footnote 29.

Opportunity 2: Enhance surveillance systems by integrating social determinants of health

Adapt and develop public health surveillance systems to routinely collect, incorporate, and analyze data on social determinants of health to deepen the understanding of health inequities across specific populations and enable targeted actions that expand access to opportunities and create environments supportive of health for all.

By prioritizing equity-focused data collection and inclusive decision-making (bringing the right voices to the table) surveillance systems can become more effective and responsive in addressing health disparities. Building these systems with equity at their core is essential for impactful and meaningful public health action. Traditionally, public health surveillance has focused on biomedical risk factors, but there is an increasing understanding and focus on how social and other determinants (e.g., structural, ecological, commercial, digital), as well as their intersections, exert a powerful influence on health outcomes. An example of the influence of social and economic factors is the mortality gaps observed during the COVID-19 pandemic Footnote 22. By linking epidemiological data to relevant variables relating to social and other determinants of health Footnote 30 and incorporating these considerations into routine surveillance, public health practitioners and community leaders can better understand the root causes of health inequities through an intersectional lens, enabling more tailored interventions. These initiatives frequently require data linkage and collaboration across levels of government, organizations and communities.

Example

CIHI is leading the development of national standards to measure health inequities, a step toward a more consistent approach to the collection and use of these data Footnote 31. In May 2020, CIHI introduced an interim standard for race-based and Indigenous identity data to address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racialized communities; this standard has been updated multiple times to meet evolving needs Footnote 21. Meanwhile, the Canada Health Infoway Social Determinants of Health Working Group is developing standards for recording social determinants of health data in digital health systems Footnote 32. Additionally, provincial, territorial, and local public health organizations are increasingly integrating social and other determinants of health into their surveillance systems and decision-making Footnote 23 Footnote 33 Footnote 34 Footnote 35 Footnote 36, thereby marking progress in addressing health inequities, particularly those related to race and ethnicity Footnote 24.

Opportunity 3: Foster collaboration and build trust with communities

Build trust with community leaders and organizations as the foundation of meaningful partnerships for public health surveillance.

Addressing health disparities requires reliable disaggregated data collection from populations that are often underrepresented in traditional public health surveillance. Through trust-based partnerships, systems can collaboratively collect, analyze, and interpret public health surveillance data that accurately reflect and contextualize the experiences of underrepresented populations, equity-deserving groups, and Indigenous rights-holders. Engaging directly with the communities served by public health programs can facilitate the appropriate collection and use of disaggregated data and the implementation of tailored public health interventions, while being mindful of the language used to convey the purpose and benefits of surveillance in different cultural contexts Footnote 37.

Example

The Black Health Plan for Ontario, developed by Ontario Health, the Wellesley Institute, and the Black Health Alliance, is a community-led initiative addressing health inequities in Black communities Footnote 38. The plan prioritizes race-based data collection, analysis, and dissemination, along with developing indicators specific to Black populations Footnote 38. Central to the plan is a data governance framework created by the Black Health Equity Working Group, which stresses data sovereignty and self-determination for Black populations, ensuring data serves the needs of the community without stigmatizing Footnote 38. The Québec government supports an integrated approach to address antimicrobial use and resistance through an inter-ministerial collaborative action plan Footnote 39 Footnote 40. The effort focuses on both human and animal health, and involves developing a public-private partnership with relevant communities such as veterinarians and feed mill owners Footnote 39. A recent study assessing the feasibility of such antimicrobial use monitoring system highlights the importance of engaging multisectoral partners to build trust to support the implementation Footnote 39.

Opportunity 4: Create the conditions to implement First Nations, Inuit, and Métis health data sovereignty

Create the conditions to implement First Nations, Inuit, and Métis health data sovereignty by working together with Indigenous health monitoring experts to advance effective health information systems.

Indigenous Peoples have unique health challenges and strengths that are best supported through Indigenous-led initiatives and solutions. Surveillance systems should uphold Indigenous data sovereignty and governance, the principle that Indigenous Peoples are owners of their own data and are best placed to make decisions and interpretations regarding its use. Collaborating with Indigenous communities to develop tools and approaches to data access and sharing based on existing Indigenous-specific frameworks is a much-needed step toward enhancing public health capacity in a manner that respects Indigenous rights and values. These frameworks, such as the FNIGC principles of OCAP® Footnote 13, the Manitoba Métis Federation principles of OCAS (Ownership, Control, Access, and Stewardship) Footnote 41, and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Footnote 42, provide guidance for data governance structures that honour community autonomy in decision-making processes.

Example

The First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia, the first of its kind in the country, is founded on tripartite agreements with the provincial and federal governments. These agreements include provisions for data sharing and linkage, moving toward the goal of sovereignty and stewardship over First Nations data for surveillance and research Footnote 43. The Métis National Council hosts the national Métis Health Policy Forum annually since 2024 Footnote 44. These events focus on the Métis Nation's current health priorities and bring together a diverse group of Métis people, including youth and Elders, policymakers, and individuals working in the health sector. This platform offers opportunities to spotlight Métis-specific priorities and encourages collaborations among individuals with shared interest and vision to make advancements on these priorities Footnote 44. The Qanuippitaa? National Inuit Health Survey is an Inuit-owned and Inuit-led national program that is informed by Inuit knowledge, and it includes Inuit from all ages, communities across Inuit regions and other urban centres Footnote 45. As a sub-committee of the National Inuit Committee on Health, the Qanuippitaa? National Inuit Health Survey Working Group supports the structure of Inuit governance Footnote 45. PHAC's Tracks surveillance system, designed to monitor Human Immunodeficiency Virus, hepatitis C, and associated risks, was implemented by First Nations Health Services Organizations in Alberta and Saskatchewan, prioritizing First Nations data sovereignty and involving Indigenous communities in all phases from design, to collection, to knowledge translation Footnote 46. The Mamow Ahyamowen partnership, involving 11 First Nations organizations in Northern Ontario, collaborates with ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) under a data-sharing agreement with the Chiefs of Ontario to better understand Indigenous health and mortality Footnote 47 Footnote 48 Footnote 49.

Opportunity 5: Enhance the capacity to conduct surveillance in a manner that values, strengthens, and incorporates First Nations, Inuit, and Métis knowledge and skills in public health assessment and responseFootnote a

Enhance the capacity for public health surveillance by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities in a manner that recognizes and builds on their existing strengths while in turn expanding First Nations, Inuit, and Métis expertise in public health assessment and response throughout the public health surveillance ecosystem.

Despite the many existing strengths present in communities across the country, the continued development of human resources, local infrastructure and capacity in the public health workforce remains critical for addressing health challenges identified as priorities by Indigenous populations. Recognizing these existing strengths in Indigenous public health assessment and response and integrating this knowledge and capacity into public health surveillance systems across Canada will pave the way to better and more culturally-relevant public health practices in the broader public health 'system of systems' in Canada. At the same time, sharing traditional knowledge and enhancing cultural safety in this manner can build greater awareness and competency within the broader public health workforce to enable more effective and culturally competent engagement with First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people engaged in improving the health of their respective communities.

Example

The First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission, created in 1994, has been providing services and training to a wide clientele (including health professionals and practitioners, health and social services directors, and community coordinators) to inform and raise awareness regarding the health of First Nations people Footnote 50. This includes lectures offered to the future physicians at the medical schools that are associated with Québec First Nations and Inuit Faculties of Medicine Program: Laval University, the University of Montréal, McGill University and the University of Sherbrooke Footnote 51. Academic institutions are vital in incorporating Indigenous perspectives into public health practice, with several institutions offering specialized Master of Public Health programs Footnote 52 Footnote 53 Footnote 54. An example of an academic initiative is the Indigenous Reconciliation Initiatives at the University of Alberta's School of Public Health Footnote 55. Through the appointment of Indigenous adjuncts and the establishment of an Elders and Knowledge Keepers program, this initiative supports Indigenous and Northern students in pursuing public health education, while weaving Indigenous knowledge, talent, and training into research and community engagement.

Opportunity 6: Invest in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis health information systems, infrastructure, and indicators

Solidify commitment to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis streams of public health assessment and response to well-being, including the development of distinctions-based health information systems, infrastructure, and indicators.

Collecting comparable data for key indicators (e.g., mortality) from both Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people sets the foundation to accommodate additional indicators that are tailored to Indigenous perspectives and allows monitoring progress towards the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: calls to Action 18 to 24 on health Footnote 56. A critical need is to expand methods for data collection on First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people living in urban and related homelands that generate population-representative health information and advancement of local First Nations, Inuit, Métis community priorities and interests in the domain of health and beyond. Such infrastructure can go beyond a focus on deficits and disparities to support the development of indicators capturing aspects of Indigenous well-being related to culture, spirituality, and interconnectedness Footnote 57 Footnote 58. Strengths-based indicators emphasizing well-being, community belonging, and connections with land and waters help create more tailored, effective, and culturally appropriate public health responses for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis populations and all people residing in Canada Footnote 57 Footnote 59.

Example

FNIGC has done foundational work in gathering national health data regarding First Nations people according to OCAP® principles, exemplified by initiatives such as the First Nations Regional Health Survey and First Nations Oral Health Survey Footnote 60. The First Nations Population Health and Wellness Agenda, released in 2021 as a partnership between the First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia and Ministry of Health, developed an Indigenous indicators framework to monitor the health of Indigenous Peoples in the province over the next decade Footnote 61 Footnote 62. The 22 indicators emphasize community health and self-determination (e.g., ecological wellness and connection to the land), supportive systems and determinants of health (e.g., food security, housing, Indigenous physicians), and various markers of physical, mental, and spiritual health. The Our Health Counts studies focused on addressing health data gaps in First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people residing in urban and related homelands Footnote 63. The Our Health Counts methodology engaged Indigenous Peoples in 'by community, for community' population health assessment and response, and set a strong foundation for collecting comprehensive and disaggregated Indigenous-specific health data Footnote 63.

Opportunity 7: Support workforce development

Support public health workforce development to improve access to training opportunities including in rural and remote communities and populations, and support a modernized, skilled and diversified public health surveillance workforce.

A well-trained workforce is vital to conduct surveillance in the rapidly evolving public health landscape. Expanding training opportunities and professional development for public health professionals is essential to ensure they are equipped with up-to-date skills in areas such as epidemiology, information management, complex systems, investigations, data visualization, and data science, while also emphasizing health challenges beyond infectious diseases. In addition to quantitative skills, socio-cultural competencies that enable effective interactions with diverse populations and communities are critical for developing and operating surveillance systems that respond to the needs of communities.

Additional training may also help reduce regional disparities and enhance capacity in northern, rural, remote, and sentinel sites. Pathways for equity-deserving groups, by way of designated scholarships, internships and priority hiring as examples, can improve cultural responsiveness and lead to better representation of the populations served. Increasing the representation of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis experts across the spectrum of health information leadership roles from governance to technical infrastructure development would help to improve engagement with Indigenous populations and address Indigenous-focused priorities. Incorporating transdisciplinary expertise, boosting training resources, and enhancing organizational agility can help surveillance systems adapt to changing public health needs and adopt new technologies to improve operational efficiency.

Example

The National Collaborating Centres for Public Health are leading a refresh of the Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada which can help to inform future public health curriculum development, job descriptions, training opportunities, and areas for professional development Footnote 64. Collaborative initiatives like Artificial Intelligence for Public Health (AI4PH) and AI4PH Summer Institute are important in preparing the public health workforce for the technological advancements and associated impacts on equity of machine learning and AI Footnote 65. New training initiatives, such as the Canadian One Health Training Program at the University of Guelph, supported by academic, governmental, and non-governmental partners, will integrate systems-level thinking on the connection between human and animal health into undergraduate education Footnote 66. Training materials developed and informed by partners through one institution can be shared more broadly to benefit the entire public health community and reduce duplication of efforts; for instance, in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, PHAC and Health Canada launched three courses to train public health professionals and volunteers as contact tracers Footnote 67 Footnote 68.

Opportunity 8: Promote interoperability through data standards

Enhance interoperability among surveillance data systems, devices, and programs across jurisdictions and local partners by establishing collaboratively developed data standards.

Common data standards are essential for interoperability. These standards facilitate collecting, sharing and integrating diverse data sources, allowing a common understanding of risk factors and health status across a 'system of systems' and enabling coordinated public health interventions. Many organizations may need support to adopt standards. As an adjunct to adoption of standards, tools and broker services can accept data 'as is' and automatically convert them to standard formats, streamlining data collection as an intermediary step before full adoption.

Example

The Pan-Canadian Health Data Charter Footnote 69, signifies a strong commitment to modernizing health data systems. This initiative promotes transparency and common standards for the secure transfer of health data to allow people in Canada to access their health information more easily. Many health organizations such as Infoway, CIHI and PHAC are working together to complete and implement frameworks like the Pan-Canadian Health Data Content Framework and the Canadian Core Data for Interoperability Footnote 70, critical steps towards the realization of the Shared Pan-Canadian Interoperability Roadmap Footnote 71. The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network, spanning eight provinces, has also developed standards for electronic medical record data, facilitating primary care research and the creation of common definitions for longitudinal chronic disease surveillance Footnote 72 Footnote 73. The Government of British Columbia is developing a Gender, Sex, Sexual Orientation Health Information Standard to support efforts to make healthcare more inclusive and equitable Footnote 74.

Opportunity 9: Review mechanisms for data sharing and linkage

Review and revise existing mechanisms for data sharing and linkage, both legal (e.g., legislation and multilateral agreements) and technological (e.g., protocols for automated data exchange), to encourage agile and responsible use of granular data to address health inequities.

Public health organizations are data stewards, and they must protect data from misuse while also ensuring its responsible application for the public good at a range of scales and contexts. Health data can be highly impactful when linked with other data, such as sociodemographic information, neighbourhood characteristics, and environmental data, to identify health disparities, which help to inform equitable and effective public health interventions. Other data linkages, such as between public health case data, laboratory data, health outcome data, and genomic data, can help public health authorities to manage infectious disease outbreaks in real-time Footnote 75. As the amount of data linkage increases, risks to privacy increase and strategies that do not centralize data for analysis may be more appropriate and feasible. In a federated model, each partner maintains control of their data while advancing interoperability by allowing remote access to their data through negotiated governance Footnote 76. Federated data approaches offer a promising solution to overcoming the legal and technological barriers to sharing and linking datasets, while also respecting Indigenous data sovereignty and ownership.

Example

The Public Health Data Steering Committee (approved by the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network), comprising FPTI partners, is developing a modernized approach to succeed the current Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement (MLISA), aiming to enhance public health data sharing by addressing existing gaps. Additionally, as part of the Working Together to Improve Health Care for Canadians Plan, PHAC is collaborating with participating provinces and territories on a proof-of-concept to demonstrate the feasibility of a federated data approach to improve timely access to immunization records, support seamless data sharing between jurisdictions, and enhances public health vaccination coverage analysis.

Moreover, the advances in linked healthcare databases across provinces and territories were crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling faster, more detailed tracking of cases, testing, outcomes, and vaccine-related outcomes. For instance, healthcare data from ICES in Ontario significantly contributed to vaccine effectiveness research Footnote 77 Footnote 78 Footnote 79 Footnote 80. Public health organizations also progressed in openly sharing pandemic-related data with the public, an approach that also allowed other public health bodies to reuse this data. For example, for tracking COVID-19 outbreaks across Canada, PHAC used publicly available data posted to the web as an interim solution until formal data sharing agreements were established as part of the Canadian COVID-19 Outbreak Surveillance System Footnote 81.

Opportunity 10: Modernize data infrastructure

Continue to modernize, maintain, and upgrade data infrastructure (e.g., innovative technology with proper updates and maintenance) to transform surveillance processes across public health partners.

Outdated information technology (IT) systems limit data exchange and interoperability, making modernization in these systems to support storage, analysis and sharing essential for effective public health surveillance. The rapid advancement of AI tools presents opportunities to streamline workflows, reduce repetitive tasks, and enhance information processing while limiting demands on overextended public health staff. However, it may not be possible to incorporate AI and other innovations into outdated IT systems and existing policies may hinder the adoption and deployment of AI tools. Embracing modern surveillance methodologies, such as digital epidemiology and machine learning, can unlock new insights from complex data, driving more informed public health actions. Nevertheless, caution must be observed as large datasets and AI systems may reflect historical and societal biases and replicate these biases in their outputs Footnote 82 Footnote 83.

Example

An example of a transformation of public health surveillance infrastructure is the elimination of the fax machine in healthcare, a goal set by various provinces Footnote 84 Footnote 85 Footnote 86. Fax machines are an outdated and unreliable technology that hindered the sharing of basic public health data during the COVID-19 pandemic Footnote 87. Technology is also changing routine surveillance workflows; for example, PHAC has used machine learning-based natural language processing to assist with automating a variety of routine tasks, such as scanning the scientific literature for drug-disease interactions and extracting information for systematic reviews of immunization Footnote 88 Footnote 89.

The public health institutions in Canada have made significant progress in recent years in adopting emerging surveillance methodologies like wastewater testing, sero-surveillance, and genomic surveillance. These methodologies leverage and scale modern data infrastructure. The Canadian COVID-19 Genomics Network consortium, including partners like Genome Canada and NML, created the Canadian VirusSeq Data Portal to facilitate the sharing of SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequences in a standardized, reusable way Footnote 90. Wastewater testing is also being applied in an increasing number of contexts, such as detecting tuberculosis in Iqaluit Footnote 91, monitoring antimicrobial resistance Footnote 92, and measuring fentanyl consumption Footnote 93.

Working toward 2030

This vision reflects the combined insights and contributions of the public and professionals working across the country and at all levels of the public health system in Canada. In presenting a vision with desired states and characteristics, this report invites all actors in public health surveillance to reflect on how they could be partners in the surveillance 'system of systems' that is integral to the collective approach of Vision 2030. Local public health authorities, with their core surveillance work and close community ties, play a key role in setting priorities, designing thoughtful data collection processes, leading innovation in surveillance practices, and sharing information in ways that respect communities and drive local action. Provincial and territorial governments provide a comprehensive view of population health by overseeing health policies, services, and surveillance and emergency response within their regions, while collaborating with federal and local partners. First Nations people, Inuit, and Métis people, and equity-deserving groups offer vital leadership in shaping health data systems that reflect their unique rights, interests, and circumstances, promoting self-determination and community well-being through culturally relevant practices. Academics, with their interdisciplinary and international collaborations and methodological innovations, can contribute cutting-edge research and fresh perspectives, working alongside public health practitioners to translate insights into real-world applications. For its part, the federal government oversees national health surveillance and the development of national frameworks and standards. It also serves as a convener to coordinate responses to public health emergencies, developing federal health policies, promoting health initiatives, and supporting collaboration across provinces, territories, and Indigenous rights-holders and partners, and international partners to facilitate the timely flow of actionable information across this cohesive 'system of systems'.

Vision 2030 sees public health surveillance partners in Canada advancing together toward a resilient 'system of systems' that is adaptable, collaborative, and equitable. By learning from each other, scaling existing strengths, and fostering the innovation already happening, public health surveillance can continue to provide timely, comprehensive insights to enhance decision-making, reduce health inequities, and improve health outcomes for all people in Canada. The 'system of systems' framework can provide a useful guide, particularly with the aim to address complex challenges such as climate change, antimicrobial resistance, and the deep interconnections between human, animal, and environmental health (i.e., One Health). Recognizing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, the 'system of systems' adopts an integrated and collective approach to solving public health issues, encourages cross-sectoral collaboration and helps to break down the barriers that have traditionally separated domains, systems, and paradigms. Recognizing that both language and action matter, progress toward this vision can support a reimagining of public health surveillance as an act of caretaking that is continually occurring across the country, focused on many important issues, scales, and timeframes. The combined efforts of partners across the country can move public health surveillance toward this vision together and ensure Canada is better prepared for current and future public health challenges, contributing to a healthier, more equitable society for all.

Appendix 1: Methodology

Summary

Consultations took place from September 2023 to March 2024 and involved 1,740 participants from across Canada. In total, 29 in-person, virtual, and academic meetings were held featuring 813 participants, with a further 927 participants answering a public engagement survey. Data generated from the engagements were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA). In this approach, researchers are actively involved in knowledge production by interpreting patterns of meaning in the data, creating relationships between codes, and organizing such relationships into themes. Two independent analysts with training in qualitative methods (hereafter referred to as "coders") worked independently to code the data using a mix of inductive (bottom-up) and deductive (top-down) content analysis and met on a weekly basis to reach consensus on areas of deviation. Candidate themes and sub-themes emerged from groupings of codes, which were discussed with a larger analytical team on a weekly or biweekly basis for discussion and validation.

Companion reports

Four companion reports were published to inform the development of Vision 2030:

- The National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools conducted a rapid review of published papers on recent innovations in public health surveillance entitled Rapid Review: What are the latest innovations in public health surveillance methods? (PDF, 616 KB)

- The National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health created a report summarizing the state of knowledge regarding public health surveillance in the Indigenous context entitled Considerations, implications, and best practices for public health surveillance in Indigenous communities (PDF, 15.6 MB)

- The Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research hosted a one-day, invitation-only Best Brains Exchange meeting in November 2023, bringing together domestic and international policymakers, researchers, implementation experts, and other key partners for a virtual discussion concerning the future of public health surveillance in Canada. The companion report entitled Best Brains Exchange what we heard report: A vision for the future of public health surveillance in Canada by 2030 provides a high-level summary of the topics discussed in this session

- The National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCIH) and the National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (NCCDH) worked in collaboration with PHAC to host a series of in-person and virtual engagements across Canada with public health personnel and other partners, from October 2023 to January 2024, to hear their challenges and aspirations for public health surveillance. The companion report entitled Public Health Surveillance 2030 Report on Regional Consultations (PDF, 963 KB) summarizes the themes from these discussions

Approach to engagement

To identify key informants to engage in the vision development process, an initial scan of public health agencies, authorities, organizations and health-related institutions was conducted. Invitation lists were created with input from the National Collaborating Centre for Public Health's Advisory Committee, PHAC Regional Offices, and local public health authorities and agencies, to ensure representativeness across geography, levels, and topics. The approach to partner engagement was both iterative and consistent, to ensure that questions asked in different consultations were similar enough to obtain comparable data. Engagement activities were also guided by a discussion guide, which laid out key themes that the Vision 2030 report was developed to address.

Questions used to guide discussions across engagements focused on the following themes:

- Vision: Describe the goals, desired outcomes, and/or idealistic state for a world-class public health surveillance 'system of systems' in Canada

- Priorities: Better understand specific areas, issues, or health conditions that are identified as having an importance or urgency for public health surveillance and intervention

- Successes: Identify achievements or positive outcomes resulting from surveillance activities that can be used to build upon and strengthen the practice of public health surveillance

- Challenges: Gain a better understanding of the obstacles, barriers and evidence gaps encountered in the practice of public health surveillance or the pan-Canadian public health 'system of systems' that limit the potential to improve the practice of public health surveillance and population health

- Opportunities: Learn from various partners about promising initiatives, solutions, or prospects to address challenges experienced within public health surveillance

Internal engagement

Within PHAC, scheduled virtual meetings were held with various governance tables that convened senior leadership including the Strategic Surveillance Management Committee, Strategic Science Committee, Vice-President Policy Committee and Executive Committee, to seek feedback on the development of this vision. Virtual meetings were also scheduled with PHAC personnels who were members of PHAC's Surveillance Community of Practice. These engagement activities took place between September 2023 and February 2024. Data were collected through transcription of recorded sessions, notetaking during discussions, messages sent via Microsoft Teams, responses submitted on Slido, and post-event surveys where applicable.

External engagement

Between September 2023 to January 2024, a mix of in-person and virtual meetings across Canada convened a range of public health partners, such as public health practitioners, academics, and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis groups. Planning and execution of engagements were completed in partnership with NCCID and NCCDH. Other engagements included an International Best Brains Exchange that was co-hosted with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in November 2023, and validation with an external panel of surveillance experts, referred to as the Surveillance Expert Round Table (SERT).

To capture a broad range of perspectives across Canada, PHAC launched a public engagement survey between November 20, 2023, and March 1, 2024. Hosted on the Consulting with Canadians webpage, the survey sought feedback from public health and health-related professionals (e.g., public health practitioners, healthcare providers, and academics), First Nations, Inuit, and Métis groups, and the general public on the future of public health surveillance in Canada. The survey was also available to PHAC employees if they were unable to participate in the planned internal engagement activities. Two survey streams were developed, with the first tailored to technical public health partners (e.g., epidemiologists, healthcare practitioners, health promoters, etc.), and the second to the public or people with less specialized knowledge/training. A public and technical discussion guide was developed to support participants as they completed the survey.

Analysis

Two coders conducted RTA of data collected from the internal and external engagement activities and responses to the online questionnaire. RTA is a type of thematic analysis whereby researchers are actively involved in knowledge production by interpreting patterns of meaning in the data, creating relationships between codes, and organizing such relationships into themes Footnote 94.

The analysis was organized around the primary research question of "What does an improved future state of public health surveillance in Canada look like?" An initial framework of categories was developed based on the discussion paper about public health surveillance Footnote 1 and was later modified (see Table 1). Parent and child codes were created within these categories and regularly updated, as the analysis progressed with patterns of meaning interpreted to create themes and sub-themes.

| Initial Categories | Final Categories |

|---|---|

|

|

Using NVivo (Version 14), coders independently analyzed the datasets and generated codes using both inductive (bottom-up) and deductive (top-down) content analysis. Data was coded into the initial categories, after which codes were added into these categories and modified as more data are analyzed. On a weekly basis, coders met to discuss significant deviations in coding approaches, identify groupings of codes and interpret relationships to determine candidate themes and sub-themes, and modify existing themes and sub-themes as needed. Further, both coders organized their relevant codes into each candidate theme and sub-theme according to the deductive categories of Challenges, Successes, Solutions, and Concepts, where themes/sub-themes/codes were updated on a weekly basis. Over the analysis period, themes and sub-themes were reviewed with other project team members to discuss interpretations, validate them, and assess if adjustments were needed.

Expert validation via modified Delphi method

Preliminary findings from analysis such as draft themes and components of the vision (e.g., characteristics of the surveillance 'system of systems', potential opportunities for action) were subject to external validation primarily by SERT members using two rounds of a modified Delphi method, an approach where input from key actors and experts in surveillance are relied on to reach group consensus. Informal validation and feedback were also sought from PHAC colleagues with relevant expertise.

Round 1 included a draft of items including the challenges, vision statement, desired states, characteristics, and opportunities for action in the form of a worksheet for SERT members and Canadian Public Health Association 2024 conference attendees to provide feedback on through descriptive text. Round 2 included a similar draft of items for SERT members to review with a request to reach a consensus, and prioritize opportunities for action based on a ranking process considering feasibility and potential impact.

Appendix 2: Challenges

Six challenges emerged from the qualitative analysis of the engagement process, each capturing a distinct facet of the ideas, desires, and frustrations shared during the consultations. Additionally, three concepts—equity, sustainability, and trust—cut across all these challenges. Health equity focuses on addressing disparities in health outcomes by identifying populations disproportionately impacted by adverse health outcomes and formulating tailored interventions, turning the issue of data sharing and linkage into an ethical imperative. Sustainability emphasizes designing public health improvements with long-term viability, including resilient infrastructure, stable funding, and adaptable governance, ensuring the system remains effective amid changing resources and global threats. Trust, foundational to public health, requires transparency and community engagement to foster confidence in data sharing. In polarized environments, prioritizing accountability and clear communication is crucial to prevent misuse of information and to build and maintain public trust throughout the surveillance process.

Challenge 1: Purpose and governance of surveillance

Public health surveillance should have clearly defined function and purpose, with transparent, sustainable, and well-funded decision-making processes to build trust and ensure continuity. The first challenge is that surveillance systems lack robust governance structures, clear objectives, and defined roles and responsibilities; equity considerations should be central within governance frameworks and in the design and evaluation of surveillance systems.

What is the purpose of a given surveillance system? Is this system meeting its public health objectives? Governance plays a key role in answering these questions—who is at the table and making decisions regarding what information is needed, how it could be collected, and its intended use. A clear definition of purpose aids in system design and evaluation, giving organizations the ability to measure progress, adapt to changing needs, and phase out obsolete systems. Participants emphasized that engaging with priority populations of surveillance should be fundamental in defining the purpose of these systems and evaluating their success. A shared understanding between practitioners and the communities providing information is crucial, particularly for the collection of potentially sensitive data related to social determinants of health to support disaggregated and equity-informed analyses Footnote 23. Collecting data without clear health goals in mind risks stigmatizing or imposing on the communities providing the information. Local public health authorities' community engagement was highlighted as vital for priority setting, which can inform decisions at provincial and federal levels to ensure surveillance efforts remain relevant and effective.

"People are looking for more disaggregated data related to social determinants of health. We don't do a good job at collecting the information at the individual level."

The purpose of individual systems is closely tied to the broader challenge of unclear roles and responsibilities among various partners in the surveillance 'system of systems' in Canada. Given provincial and territorial jurisdiction over health, PHAC has struggled from the beginning to clearly define its function within the broader surveillance system Footnote 17 Footnote 95 Footnote 96 Footnote 97. Data reporting to federal agencies like PHAC by local, provincial, and territorial governments is voluntary, relying on a mix of formal and informal agreements. Public health organizations often express frustration regarding the unclear purpose of data requests and fielding repeated requests for the same information from different organizations (e.g., PHAC, CIHI, Statistics Canada, hospitals). This lack of clarity leads to frustration, redundancy, inefficiency, and data fragmentation, hindering coverage of critical health conditions and sub-populations. Some participants suggested that the federal government could better support other levels of government by administering national surveys and providing cleaned, value-added datasets aggregated from the provinces and territories.

"Better delineation of federal and provincial responsibilities. I find that there is duplication of surveillance efforts between the provinces and the federal agencies."

Challenge 2: Partnerships, collaboration, and engagement

Relationships between partners within public health surveillance should be based on trust, meaningful engagement, intersectionality, feedback loops, information sharing, and sustainable investments. The second challenge is that collaboration between communities and public health providers is insufficient to support effective and responsive surveillance efforts.

Effective knowledge mobilization relies on mutual communication among all partners. Traditionally, public health surveillance follows a hierarchical flow from the local level up toward the national level. Participants suggested an alternative 'network of relationships' model, where information flows in all directions as needed. This extends to 'closing the loop' by returning information to the communities where data were collected for a full-cycle community involvement, as accessible local-level information is key to effective knowledge mobilization. In addition to building long-term relationships with community and advocacy groups, partnerships with academia and research bodies are valuable to translate research into public health practice and strengthen community bonds. Participants described PHAC as being well-positioned to play a convening role to strengthen national connections among public health partners.

Community partnerships are key in creating an environment where an individual feels safe, respected and valued, which is essential for collecting sensitive information related to the social determinants of health, accurately and ethically. Often, people with the closest connections and deepest knowledge regarding the health of individuals and communities are clinical, non-profit, and other local organizations; building trust and establishing secure data exchange mechanisms are crucial for making progress on health equity goals.

Clear, transparent communication is essential to combat misinformation Footnote 98. Some issues with communication during the COVID-19 pandemic included delayed communication, inconsistent messaging and terminology, a lack of clarity regarding uncertainty and the limits of current knowledge, a lack of transparency about the evidence used for decision-making, and insufficient engagement with diverse communities Footnote 99. While public datasets and dashboards for epidemiological and vaccine-related data improved transparency, they sometimes lacked the granularity needed for local decision-making Footnote 100 Footnote 101. Participants emphasized that communication should be an integral part of public health surveillance programs to address these issues in future crises.