The health of young people in Canada: Focus on mental health

Download in PDF format

(38.7 MB, 241 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2025-06-23

Cat.: HP15-13/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-74692-0

Pub.: 240653

Findings from the 2022 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Study

Foreword

We are pleased to present the 2022 National Report, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC): The Health of Young People in Canada: A Focus on Mental Health.

The 2022 National Report focuses on mental health, building on a similar theme from the 2010 National Report, and examines other important social determinants of youth health including physical activity, bullying, teen dating violence, substance use, social media use, healthy eating, and COVID-19. Additionally, for the first time, the 2022 HBSC report explores the experiences of transgender and gender-diverse youth, marking a pivotal step in recognizing, understanding, and addressing the diverse needs of all young people in Canada, regardless of gender identity. These findings are particularly revealing, as the health and health behaviour experiences of these “TGD” youth are consistently worse than others, no matter which indicator of health status is examined.

More positively, we were encouraged by the finding that strong relationships continue to matter to youth. Students who report strong relationships with their parents, families, friends, and within their schools are much more likely to report better mental health and higher levels of well-being. The report also identifies that – regardless of socioeconomic background – it is possible for young people in adverse conditions to thrive if they are fortunate enough to have the right supports and relationships in their lives. On the other hand, the findings also identified some important concerns. We continue to observe that cisgender girls in Canada report experiencing significant health problems in multiple domains. Developmentally, as young people transition to grades 9 and 10 many different negative health outcomes start to emerge, especially those related to mental health. The report also provides insights into the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, with many HBSC survey participants reporting negative effects on their relationships with others and their school and health experiences.

The 2022 HBSC National Report is consistent with the Public Health Agency of Canada’s mission to promote and protect the health of Canadians through leadership, partnership, innovation, and action in public health. Canadian HBSC findings improve our understanding of young people's health and serve as a vital source of information and evidence for researchers, stakeholders, and those who work in the school setting.

We would like to extend our gratitude to the over 26,000 students from more than 300 schools across Canada who shared their lived experiences and provided their reflections and insights on the findings. These youth perspectives continue to be an invaluable contribution to our work. We are also grateful to teachers and school administrators for their collaboration and support in carrying out this survey. Together, we can support a healthier future for young people in Canada.

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by: Wendy Craig (Queen’s University, Department of Psychology), Valerie F. Pagnotta (Brock University, Department of Health Sciences), Stephanie Wadge (Brock University, Department of Health Sciences), Matthew King (Queen’s University, Department of Psychology), and William Pickett (Brock University, Department of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, Department of Public Health Sciences).

This report presents findings from the 9th cycle of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey in Canada. We would like to acknowledge the collaborative efforts of the 50 participating research teams from Europe and North America and the ongoing support of the International Coordinating Centre in Scotland, as well as the International Databank Coordinating Centre in Norway.

The administration of the HBSC survey and the presentation of findings in this report are made possible by funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada through the Youth Policy and Partnerships Unit in the Division of Children and Youth. Special appreciation is given to Dr. Suzy Wong, Senior Policy Analyst; Deepika Sriram, Acting Senior Policy Analyst; Jennifer Anderson, Manager; as well as reviewers within the Government of Canada for providing invaluable insight and contributions throughout the planning and the completion of this report.

The Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health (JCSH) collaborated with the HBSC team to provide active support in the data collection phase of the study and to identify priority issues in the development of the survey instruments and for reporting. Leadership in our collaboration was provided by Susan Hornby, Senior Advisor the JCSH Secretariat, and the JCSH School Health Coordinators’ Committee.

We would like to acknowledge Larissa Lobo and Jayne Morrish, for their work in bringing together our National Youth Advisory Council and to thank the young people who made up the Council. Our Council provided advice and input throughout the process from input on questions to interpreting the data, and providing lived experiences based on the results and who so candidly shared with us their thoughts and experiences. Salony Sharma contributed to the youth engagement component of the Canadian national survey, including being the designer of the school reports generated as part of the HBSC Canada dissemination efforts.

The HBSC team was responsible for collecting and analyzing the data under the supervision and organization of Matthew King. Zoe Saine, Christina Luzius-Vanin, Ella Blondin and Rebecca Stroud Stasel were responsible for contacting school jurisdictions and schools and coordinating the administration of the survey.

Data entry, coding, questionnaire handling, and the related tracking and documentation were carried out by Mahma Ahmed, Reem Atallah, Dayna Bastien, Arielle Ventura Baguio, Riley Bonar, J Burns, Kadance Byron, Sophie Craig, Sophia Coppolino, Jade Deluca-Ahooja , Mackenzie Gribbon, Joshua Williams Haberer, Andrew Hall, Kareen Hewitt, Mazin Hussain, Yuhan Jiang, Jade Leonard, Nicole Li, John-Angus Maclean Davison, Lachlan Maclean Davison, Sofia Mancini, Logan McLellan, Olivia Merulla, Lucy Morrow, Julia Noble, Efkan Oguz, Sydney Orsak, Bridgette Paisley, Hope Rutledge, Kyran Sachdeva, Kerlas Samaan, Emily Sowa, Hailey Swain, Madison Taylor, Jacob Turnbull, Luning Wang, Haichaoyang Yan, and Lilly Zepp.

Diane Yocum was responsible for carrying out and overseeing the many administrative tasks required in the questionnaire development process and collecting the data. Grace Moffat carried out a similar role for the research team in the completion of this report.

Cameron Hines was responsible for preparing and editing the data files and figures and the text in the report. Brock Ostrom graphically designed the report. Chantal Caron was responsible for translating the English version of the report into French.

We would like to thank all of the co-investigators who have contributed to the development of the measures, the methodology, as well as the conceptual direction of the report: Dr. Colleen Davison and Dr. Ian Janssen of Queen’s University; Dr. Gina Martin, Athabasca University; Dr. Frank Elgar, McGill University; Dr. Kathy Georgiades, McMaster University; Dr. Scott Leatherdale, University of Waterloo; Dr. Michael McIsaac, University of Prince Edward Island; Dr. Nour Hammami, Trent University; Dr. Theodore Christou, Ontario Tech University; and Dr. Elizabeth Saewyc, University of British Columbia.

Most importantly, we wish to thank all the students who were willing to share their experiences with us, as well as the school principals, teachers, school jurisdictions, and parents, for making this survey happen.

Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Mental health

- Chapter 3: Home and family

- Chapter 4: Friends

- Chapter 5: School

- Chapter 6: Community

- Chapter 7: Physical activity, screen time and sleep

- Chapter 8: Healthy eating

- Chapter 9: Healthy weights

- Chapter 10: Injury and concussions

- Chapter 11: Bullying and teen dating violence

- Chapter 12: Spiritual health

- Chapter 13: Substance use

- Chapter 14: Sexual health

- Chapter 15: Social media use

- Chapter 16: Covid-19 pandemic

- Chapter 17: Youth perspective and priorities

- Chapter 18: Key messages and themes

Chapter 1: Introduction

Purpose

Conducted every four years using a common research protocol that is developed by its International Assembly of Principal Investigators, the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study examines the health and health behaviours of youth aged 11-15 across 50+ countries. As a cross-national research study, the survey aims to understand young people’s health through their social and environmental contexts. By gathering various health indicators in relation to their home life, school life, community setting, peer relationships, and health risk or health-promoting behaviours, the health of our youth can be analyzed and compared at internationalReference 1 and nationalReference 2 levels. In 1990, Canada became a member country and has participated in each cycle of the survey since, allowing for comparisons over time. Through the HBSC study, a robust body of literature and reports has been developed and used to inform both policy and practice in the country.

Canadian HBSC objectives

In Canada, the HBSC study is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and conducted by Queen’s University, with collaborative support from other university-based researchers from across Canada. The questionnaire and sampling approach used for Canadian students is governed by the international HBSC study protocol, which includes the requirement to ask a large series of items contained in the mandatory international HBSC questionnaire.Reference 1Reference 2 Additional items used in Canada are developed through a broad-based consultation model with PHAC, provincial and territorial Ministries of Health and Education through the Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health (JCSH), a diverse panel of Canadian youth, and the Canadian HBSC research team.

The primary objectivesReference 3 of the HBSC are to:

- Initiate and sustain national and international research on health and well-being, health behaviour, the social determinants of health, and the social context of health in adolescents.

- Disseminate findings to relevant audiences, including researchers, policymakers, health promotion practitioners, teachers, parents, and adolescents.

- Inform and support the development of health promotion programs and interventions with adolescents (referred to as “school-aged children”, internationally).

- Contribute to a global network that generates new evidence related to adolescent health and well-being.

Methods

Selection of schools:

- Nine provinces and two territories participated in the 2022 cycle of the HBSC study. New Brunswick and Nunavut were unable to participate in this cycle.

Selection of students:

- The number of classes in specific schools was estimated based on the grades in the school, the number of teachers, the total enrolment, and the enrolment by grade, while accounting for known variations in class structure.

- Classes had an approximately equal chance of being selected.

- All classes in grades 6 through 10 in selected schools were invited to participate.

- Students within the selected classrooms, following consent, were asked to complete the survey questionnaire.

Survey administration:

- Data were collected in 2022 and 2023, during the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years.

- Participating students completed questionnaires in school during one 45 to 70 minute class.

- Schools could choose to have students complete the questionnaire using an online web-based methodology or with paper booklets. Fifty-four percent of the questionnaires in the dataset were completed using the online methodology.

- In Yukon, data collection was carried out under the supervision of the Yukon Bureau of Statistics. Onsite data collection was carried out by research personnel going into the schools.

The Canadian HBSC Youth Advisor Panel was consulted in the development of the questionnaire, and their thoughtful feedback is reflected in the report content as well as their illustrative thoughts provided in every chapter.

Sex and Gender Considerations:

In the 2022 cycle of the HBSC study, youth were asked to identify what sex they were assigned at birth according to the following categories: “Female” or “Male.” Additionally, youth were asked to self-identify their gender identity according to the following categories: “Girl”, “Boy”, “I identify myself neither boy nor girl” or “Other/s (please specify).” Youth whose gender identity aligned with the sex they were assigned at birth were categorized as cisgender boys (sex assigned at birth=male and gender identity=boy) or cisgender girls (sex assigned at birth=female and gender identity=girl). Youth whose sex assigned at birth did not align with their gender identity, and those who selected “I identify myself neither boy nor girl” or “Other/s (please specify)” as their gender identity, were categorized as transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth. All TGD youth were grouped together in a separate category of adolescents, to ensure sufficient sample sizes for analyses that stratified by gender identity.

| Gender | Measure | Grade | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Cisgender boys | n | 2,931 | 2,663 | 2,704 | 2,395 | 1,812 | 12,505 |

| % | 48.0 | 48.4 | 49.4 | 47.2 | 47.8 | 48.2% | |

| Cisgender girls | n | 2,841 | 2,487 | 2,436 | 2,372 | 1,747 | 11,883 |

| % | 46.5 | 45.2 | 44.5 | 46.7 | 46.1 | 45.8% | |

| Transgender & gender-diverse (TGD) youth | n | 333 | 355 | 329 | 310 | 228 | 1,555 |

| % | 5.5 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.0% | |

| Total | n | 6,105 | 5,505 | 5,469 | 5,077 | 3,787 | 25,943 |

| n = Total population | |||||||

| Province or Territory | Schools | Students | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | nTable 1.2 Footnote * | |

British Columbia |

2.5 |

8 |

3.8 |

1,007 |

Alberta |

6.0 |

19 |

8.3 |

2,180 |

Saskatchewan |

6.3 |

20 |

6.9 |

1,815 |

Manitoba |

39.1 |

124 |

43.5 |

11,465 |

Ontario |

9.1 |

29 |

8.3 |

2,201 |

Quebec |

7.3 |

23 |

2.9 |

772 |

Newfoundland and Labrador |

7.9 |

25 |

8.1 |

2,142 |

Nova Scotia |

1.3 |

4 |

1.7 |

456 |

Prince Edward Island |

5.0 |

16 |

7.5 |

1,985 |

Northwest Territories |

8.8 |

28 |

4.5 |

1,193 |

Yukon |

6.6 |

21 |

4.3 |

1,144 |

TOTAL |

100% |

317 |

100% |

26,360 |

n = Total population

|

||||

The focus of this report

Following the 2010 HBSC national report, which focused on mental health, it was evident that further understanding the mental health of Canadian young people was critical. In consultation with PHAC, the JCSH, and the HBSC Youth Advisor Panel, it was determined that the 2022 national report would also focus on mental health. This topic will be explored through standard, internationally accepted indicators of mental health status, both positive and negative. Each of these indicators had been subjected to extensive validation efforts in Canada and internationally. Four of these indicators were chosen for more in-depth analyses throughout the report, including factors associated with positive mental health status (Life Satisfaction, World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) Well-being index), and negative mental health status (Loneliness, Health Complaints).

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured by asking youth to rate their lives on the Cantril ladderReference 4 from zero to ten. Zero, the lowest position on the ladder, represented “the worst possible life for you” and ten, the highest position on the ladder, represented “the best possible life for you.”

WHO-5 Well-being Index

The WHO-5 Well-being indexReference 5Reference 6 is comprised of five questions, with response options ranging from 0 (“at no time”) to 5 (“all of the time”). Responses to these five questions were then totaled and multiplied by four (scores could range from 0-100) to determine the overall WHO-5 Well-being Score. Based on precedent,Reference 5Reference 6 scores in the range of 0 to 50 are categorized as “poor well-being”.

Table 1.3. WHO-5 Well-being items:

- I have felt cheerful and in good spirits.

- All of the time= 5

- Most of the time=4

- More than half the time=3

- Less than half of the time=2

- Some of the time=1

- At no time=0

- I have felt calm and relaxed.

- All of the time= 5

- Most of the time=4

- More than half the time=3

- Less than half of the time=2

- Some of the time=1

- At no time=0

- I have felt active and energetic.

- All of the time= 5

- Most of the time=4

- More than half the time=3

- Less than half of the time=2

- Some of the time=1

- At no time=0

- I woke up feeling fresh and rested.

- All of the time= 5

- Most of the time=4

- More than half the time=3

- Less than half of the time=2

- Some of the time=1

- At no time=0

- My daily life has been filled with things that interest me.

- All of the time= 5

- Most of the time=4

- More than half the time=3

- Less than half of the time=2

- Some of the time=1

- At no time=0

Loneliness

Students were asked how frequently they had felt lonely in the last 12 months. Frequency of loneliness was measured as occurring “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “most of the time,” and “always.”

Health complaints

Students were asked to rate how often in the last six months they had experienced each of the following subjective health complaints: “headache,” “stomach-ache,” “backache,” “feeling low,” “irritability or bad temper,” “feeling nervous,” “difficulties in getting to sleep,” and “feeling dizzy.” Frequency responses included “about every day,” “more than once a week,” “about every week,” “about every month,” and “rarely or never.”

Statistical analysis

Nationally representative estimates (e.g., proportions) were calculated using survey weights, in order to reflect the actual enrolments of students within each grade (from grades 6 to 10) and province or territory. Across the report, data are most often presented within two grade groupings (grades 6 to 8 and grades 9 and 10). The dataset is weighted such that each provincial/territorial sample has each of the single grades contribute to the grade groupings proportionate to the actual known student enrolment in those grades. All reported estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) accounted for classroom-level clustering.

In this report, we present prevalence levels of key health indicators, overall and within groups defined (for example) by grade level and gender. In doing so, we present differences between groups in terms of absolute differences in prevalence, expressed in terms of “percentage points”. For example, if the prevalence of a health behaviour is 15% in cisgender girls and 10% in cisgender boys, the absolute difference is 5% in terms of prevalence or percentage points (15% minus 10%). This could also be described as a 5 percentage point increase in cisgender girls relative to cisgender boys, or a 5 percentage point decrease in cisgender boys relative to cisgender girls. An alternative expression of these differences could be in terms of “relative difference”. For example, the 15% vs. 10% increase described above could be described in relative terms as a 150% increase in prevalence for cisgender girls relative to cisgender boys, or a 1.5-fold increase in prevalence in cisgender girls vs. cisgender boys. However, to be aligned with past national reports and to be consistent throughout the report, we have chosen to describe differences in absolute and not relative terms.

Some analyses of prevalence estimates are also presented over time. In these analyses, estimates are stratified by up to nine survey cycles (1990 to 2022), grade level (6 to 8, 9 and 10) and gender. Because sex assigned at birth was only asked in the 2022 survey, these trends analyses are limited to the students who self-identified as “boys” (cisgender and transgender) and “girls” (cisgender and transgender) to ensure comparability between cycles.

In addition, in some analyses, prevalence estimates are presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each group. In making comparisons, the statistical significance of group differences can be inferred by whether or not the CIs overlap, where a lack of overlap implies significance at the 5% level of statistical significance (p<0.05). Throughout the report, where statistical significance is achieved using this method, we comment upon the importance of the observed differences. Where there is clear overlap in the CIs, we interpret this pattern as indicating no difference between the groups. This represents a very conservative method of inferring statistical significance from confidence intervals.

The theme of this report is on the mental health of young people in Canada. A special focus of many of the chapters was therefore on how the four standard indicators of mental health status correlated with other relevant HBSC indicators presented in the chapter. These analyses considered potential determinants of mental health, as well as the consequences of mental health status. This analysis was also “intersectional”Reference 7 in design, meaning here that analyses were repeated within socio-demographic “social locations” defined by combinations of grade level (6 to 8, 9 and 10), gender identity (cisgender boys, cisgender girls, transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth) and socio-economic status (more well off vs. less well off, as measured by the HBSC relative material wealth item, which asks students to report how “well off” they perceive themselves to be compared to their peers). Pearson’s correlation statistics were used to explore the correlations, with resulting values categorized into four groups: 0 to 0.19 (very weak), 0.2 to 0.39 (weak), 0.4 to 0.59 (moderate), and 0.6 and higher (strong). Variables included in these correlational analyses were left in their original (continuous, scaled ordinal) as opposed to reclassified, categorical forms. Correlations that were not statistically significant (p<.05) were denoted as ‘NS’ within analyses.

Chapter 2: Mental health

According to the World Health Organization, “mental health is a state of well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community.”Reference 8 Mental health “underpins our individual and collective abilities to make decisions, build relationships, and shape the world that we live in”Reference 8 and it is “a basic human right”Reference 8 which is “crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development.”Reference 8

In recent years, the mental health of young people in Canada has become a public health priority as indicators of poor mental health have been on the rise.Reference 9 Nearly 25% of hospitalizations for children and youth aged five to 24 were for a mental health concern in 2020.Reference 9 Of these mental health related hospitalizations, 58% were for females and 42% were for males.Reference 9 Mental health consultations,Reference 10 diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders,Reference 10 the rates of prescribing mood and anxiety medications to young people,Reference 9 and incidence of anorexia nervosa,Reference 11 have all increased. Reasons for these increases are complex but research suggests an interplay of factors including, but not limited to, the COVID-19 pandemic,Reference 12Reference 13Reference 14 the climate crisis,Reference 15Reference 16 discrimination,Reference 17Reference 18 and problematic social media use.Reference 19Reference 20

Youth often perceive their own mental health differently than their parents do, with many young people rating it less positively than their parents.Reference 21 Parents may not always be aware of the mental health difficulties that their children are experiencingReference 22 and it is important to learn directly from young people about their own perceptions of their mental health experiences.

Description of items

In the HBSC survey, mental health is measured through various questions and scales. With respect to negative indicators suggestive of mental illness, some describe the frequency and intensity of feelings of being sad or hopeless, lonely, and nervous. Youth were also asked to indicate how frequently in the last six months they had experienced subjective health complaints (e.g., headache, stomach-ache, difficulties in falling asleep), as a further indicator of psychosomatic symptoms consistent with poor mental health. In terms of positive mental health, youth reported on their mental health through the WHO-5 Well-being Index.Reference 23Reference 24 This index has a range of values from 0-100, and a score between 51-100 quantifies higher relative well-being. Other indicators of positive mental health include measures of self confidence and life satisfaction.

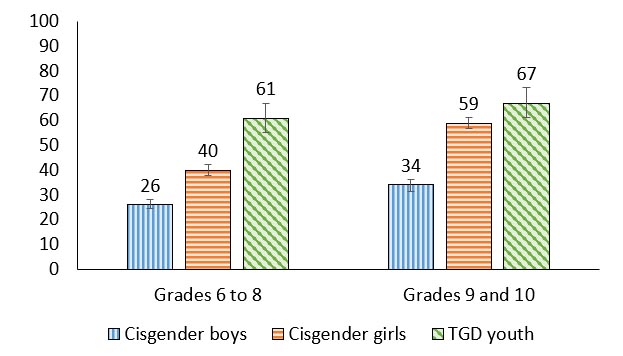

Felt sad or hopeless

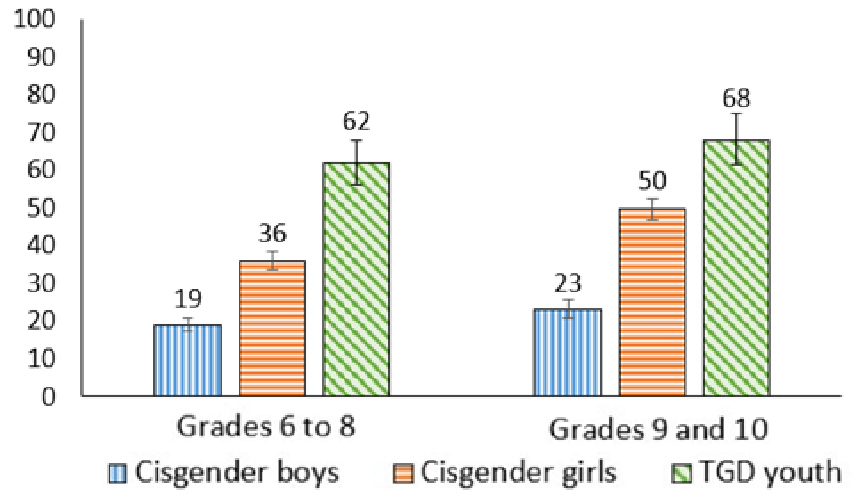

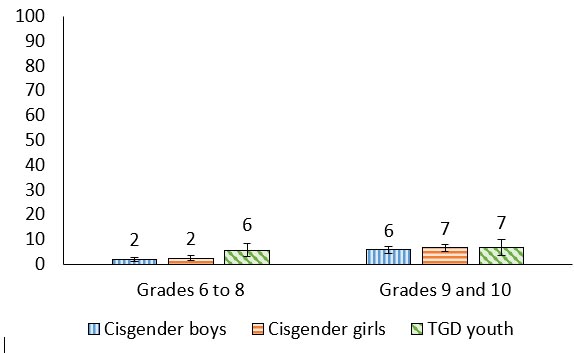

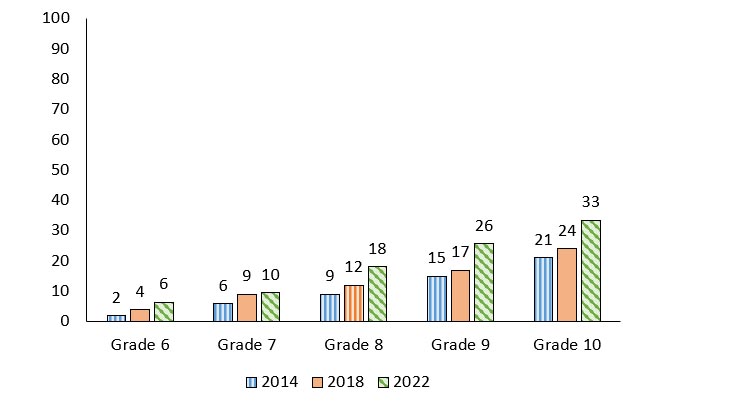

Figure 2.1. Students who reported that during the past 12 months they felt so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that they stopped doing some usual activities, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 2.1: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 19 (17.3, 20.8) | 36 (33.8, 38.7) | 62 (56.2, 67.9) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 23 (21.0, 25.6) | 50 (46.9, 52.5) | 68 (61.6, 75.3) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- In each gender group, the proportion of young people feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more was higher among grades 9 and 10 youth compared to those in grades 6 to 8.

- This difference was highest among cisgender girls, with 50% of cisgender girls in grades 9 and 10 reporting feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more compared to 36% of cisgender girls in grades 6 to 8; a 14 percentage point difference.

- The highest prevalence levels of feeling sad and hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more were reported by TGD youth, regardless of grade.

“I think that boys report higher positive mental health because of societal expectations, boys are expected to just get over it.”

Trends in feeling sad or hopeless among boys

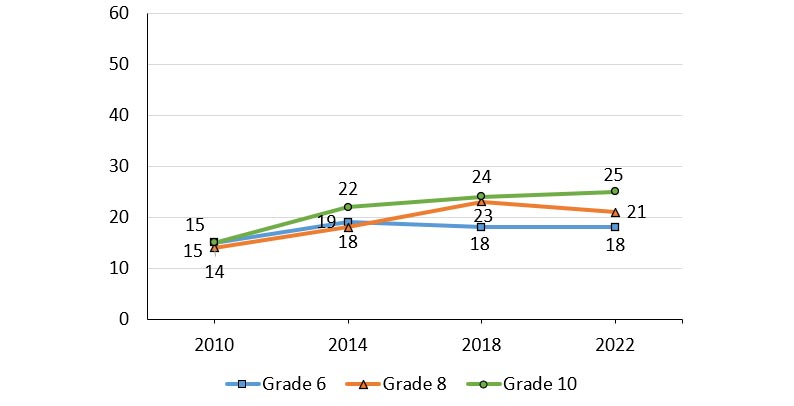

Figure 2.2. Boys who reported that during the past 12 months they felt so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that they stopped doing some usual activities, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “boys” in all cycles.

Figure 2.2: Text description

| Grade level | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 15 | 19 | 18 | 18 |

| Grade 8 | 14 | 18 | 23 | 21 |

| Grade 10 | 15 | 22 | 24 | 25 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||

- In general, the proportion of boys who reported feeling sad or hopeless has increased over time. For example, 25% of boys in grade 10 reported this measure in 2022 compared to 15% in 2010.

- When the three grade levels are compared, boys in grade 10 consistently reported the highest prevalence of feeling sad or hopeless.

Trends in feeling sad or hopeless among girls

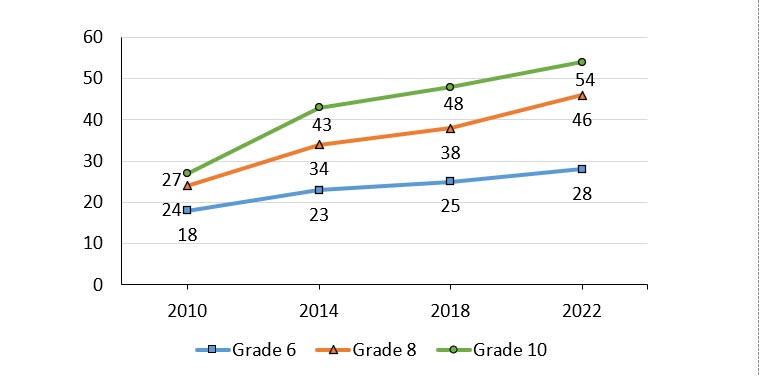

Figure 2.3. Girls who reported that during the past 12 months they felt so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that they stopped doing some usual activities, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “girls” in all cycles.

Figure 2.3: Text description

| Grade level | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 18 | 23 | 25 | 28 |

| Grade 8 | 24 | 34 | 38 | 46 |

| Grade 10 | 27 | 43 | 48 | 54 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||

- In general, the proportion of girls who reported feeling sad or hopeless has increased over time. For example, 54% of girls in grade 10 reported this measure in 2022 compared to 27% in 2010.

- Girls in grade 10 consistently reported higher proportions of feeling sad or hopeless compared to girls in grades 6 and 8.

- Girls, when compared to boys, have consistently reported higher proportions of feeling sad or hopeless in all survey cycles from 2010 to 2022.

Felt lonely

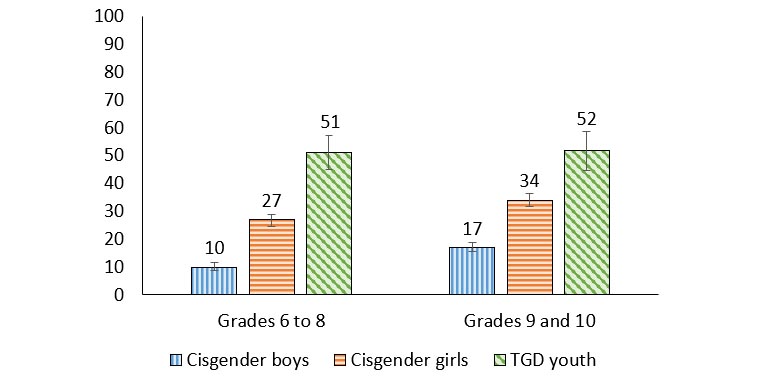

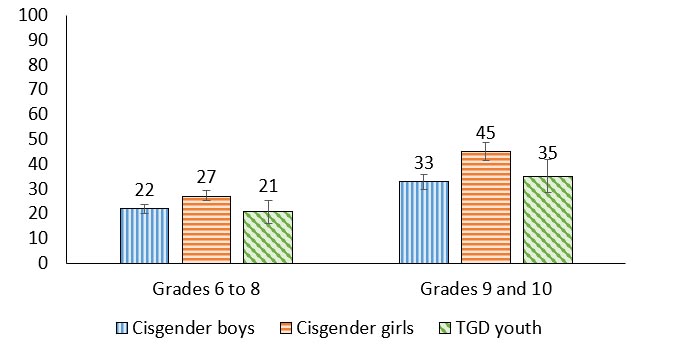

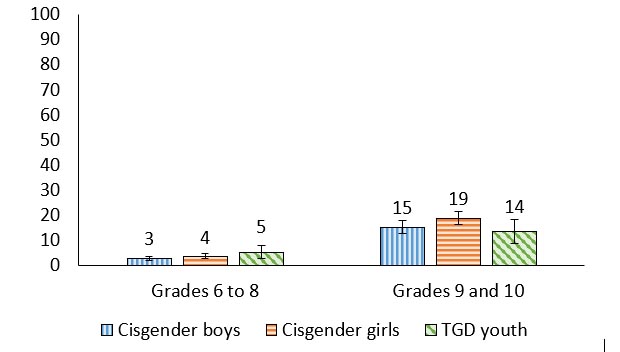

Figure 2.4. Students who reported they felt lonely most of the time or always, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 2.4: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 10 (9.0, 11.5) | 27 (24.5, 28.9) | 51 (44.9, 57.1) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 17 (15.5, 19.0) | 34 (31.7, 36.4) | 52 (44.7, 58.6) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- In cisgender boys and cisgender girls, the proportion of young people feeling lonely most of the time or always was 7 percentage points higher among grade 9 and 10 youth compared to those in grades 6 to 8.

- The highest prevalence of feeling lonely most or all of the time was among TGD youth (51% in grades 6 to 8 and 52% in grades 9 and 10). The fact that a majority of TGD youth experience these negative feelings even in the early grades was of concern.

Felt nervous

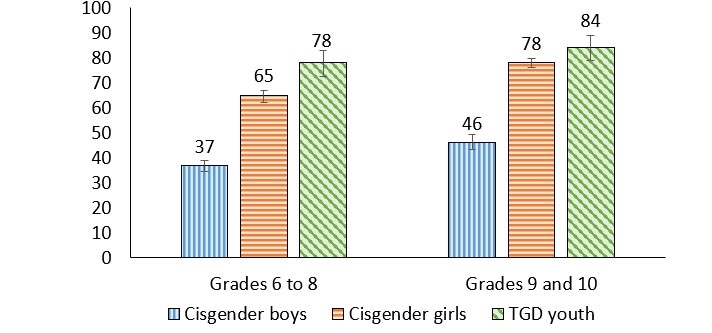

Figure 2.5. Students who reported that they felt nervous at least once a week in the last six months, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 2.5: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 37 (34.5, 38.8) | 65 (62.2, 67.0) | 78 (72.7, 82.8) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 46 (43.2, 49.2) | 78 (76.0, 79.9) | 84 (79.2, 88.9) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- The proportion of cisgender youth feeling nervous at least once a week was higher among grade 9 and 10 youth compared to those in grades 6 to 8.

- This difference in feeling nervous was highest among cisgender girls in grades 9 and 10 (78% vs. 65%, a 13 percentage point difference), followed by cisgender boys (46% versus 37%, a 9 percentage point difference).

- In grades 6 to 8, TGD youth reported feeling nervous more than cisgender youth (78% of TGD youth vs. 65% of cisgender girls vs. 37% of cisgender boys).

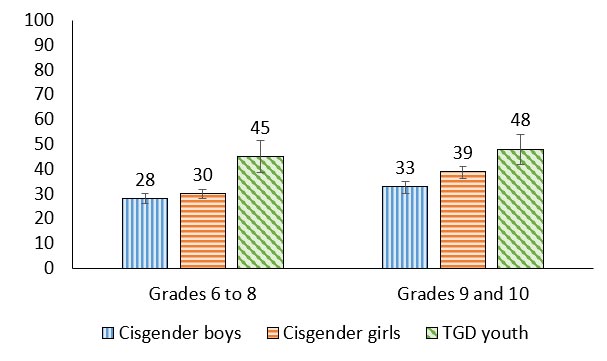

Health complaints

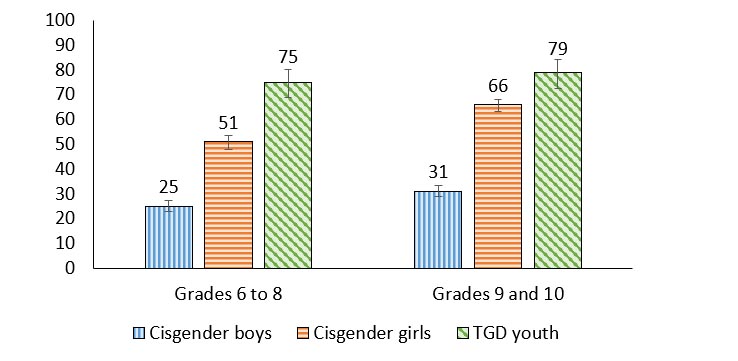

Figure 2.6. Students who reported 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than weekly, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 2.6: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 25 (22.8, 27.2) | 51 (48.0, 53.5) | 75 (69.0, 80.4) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 31 (28.8, 33.4) | 66 (63.4, 68.2) | 79 (72.6, 84.3) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- In general, the proportion of young people who reported 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than weekly (a standard indicator of negative mental health status) was higher among grade 9 and 10 youth compared to those in grades 6 to 8.

- This difference in health complaints was highest among cisgender girls, with 66% of cisgender girls in grades 9 and 10 reporting health complaints compared to 51% in grades 6 to 8, a 15 percentage point difference.

- Regardless of grade, TGD youth reported 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than cisgender youth.

“People are starting to become more comfortable opening up with their health in high school, especially in my school we have presentations about mental health and it’s okay to talk about it.”

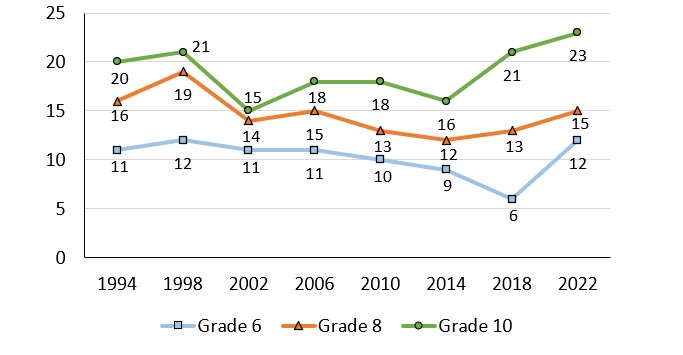

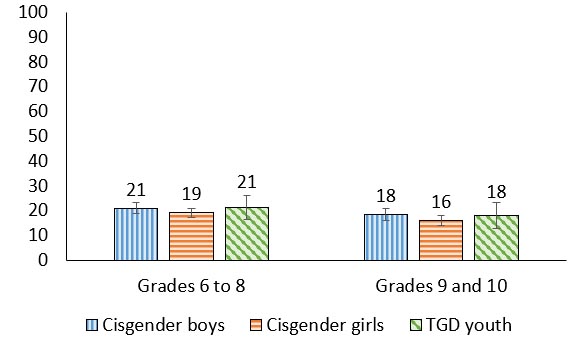

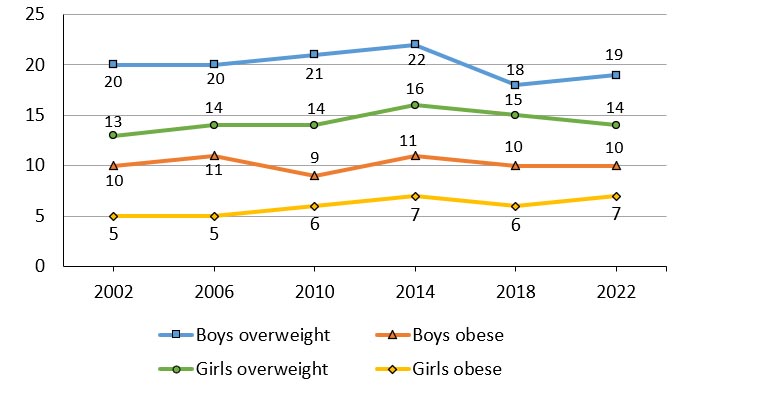

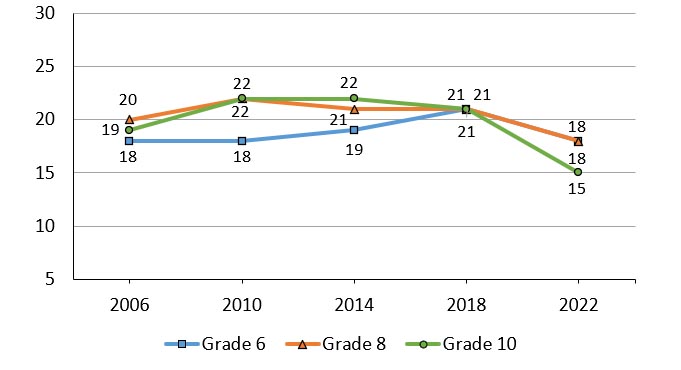

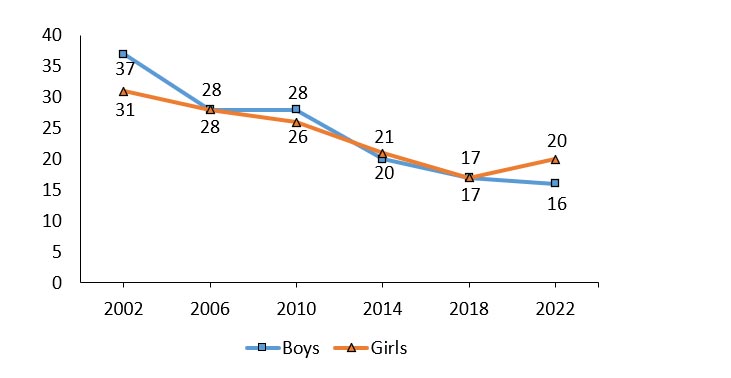

Trends in health complaints among boys

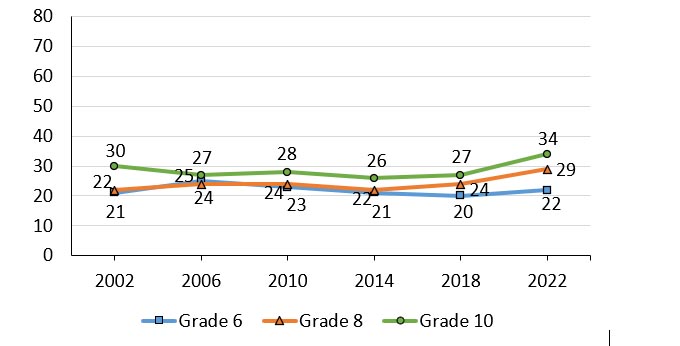

Figure 2.7. Boys who reported 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than weekly, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “boys” in all cycles.

Figure 2.7: Text description

| Grade level | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 21 | 25 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 22 |

| Grade 8 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 24 | 29 |

| Grade 10 | 30 | 27 | 28 | 26 | 27 | 34 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||||

- The proportion of boys reporting 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than weekly was fairly stable over time. For example, among boys in grade 10, this proportion declined from 30% in 2002 to 26% in 2014, then increased to a high of 34% in 2022.

- 29% of boys in grade 8 and 34% of boys in grade 10 reported 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints in 2022, the highest proportions ever reported amongst these groups.

- Trends among boys in grade 6 were less pronounced.

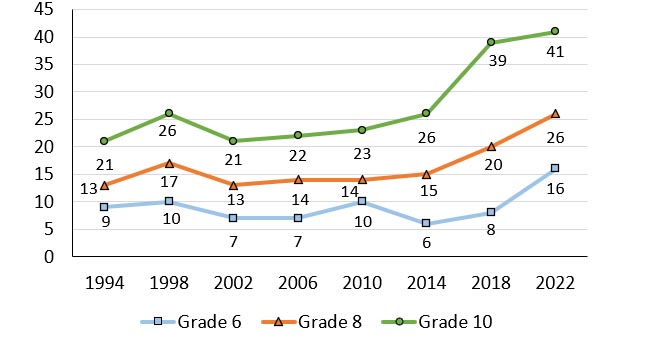

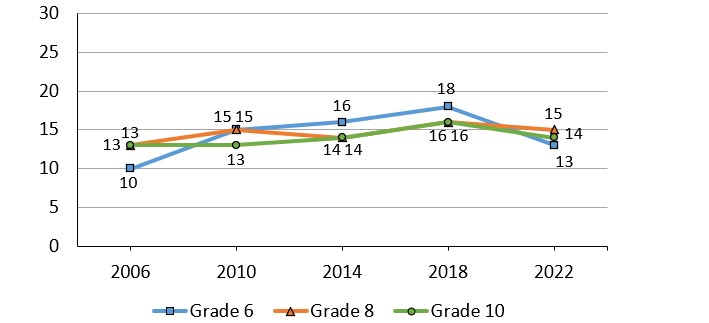

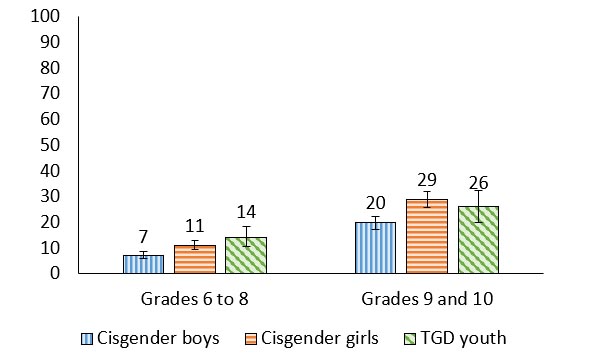

Trends in health complaints among girls

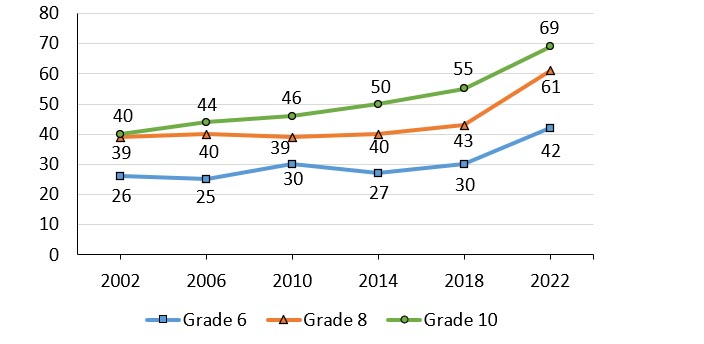

Figure 2.8. Girls who reported 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than weekly, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “girls” in all cycles.

Figure 2.8: Text description

| Grade level | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 26 | 25 | 30 | 27 | 30 | 42 |

| Grade 8 | 39 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 43 | 61 |

| Grade 10 | 40 | 44 | 46 | 50 | 55 | 69 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||||

- From 2002 to 2022, the proportion of girls reporting 2 or more of 8 subjective health complaints more than weekly has increased. For example, among girls in grade 6, in this proportion increased from a low of 26% in 2002 to a high of 42% in 2022, a 16 percentage point difference. A similar trend was observed in girls in grade 8, increasing from a low of 39% in 2002 to a high of 61% in 2022. Grade 10 girls had the largest increase (29%), from a low of 40% in 2002 to a high of 69% in 2022.

- Overall, girls reported higher proportions of subjective health complaints compared to boys from 2002 to 2022.

Self confidence

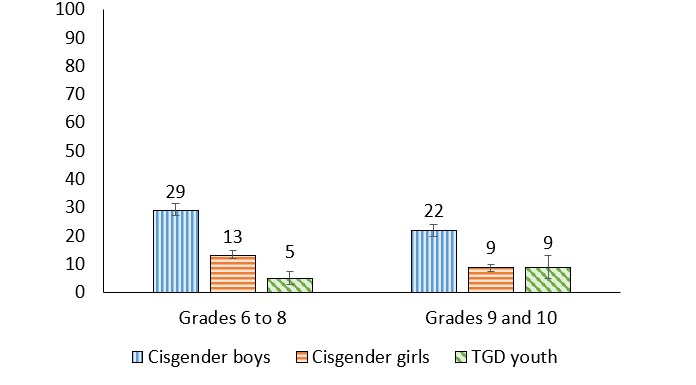

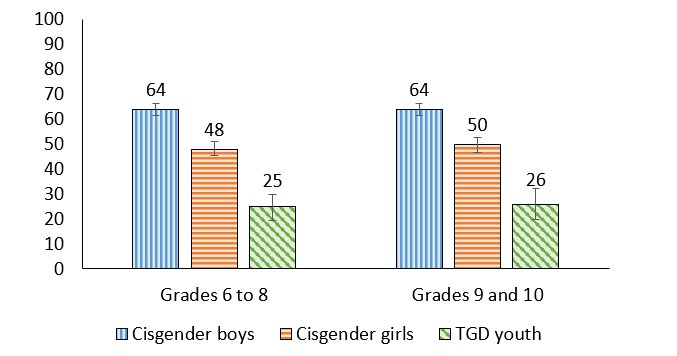

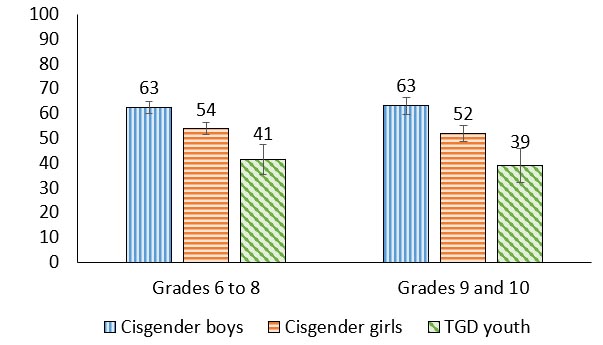

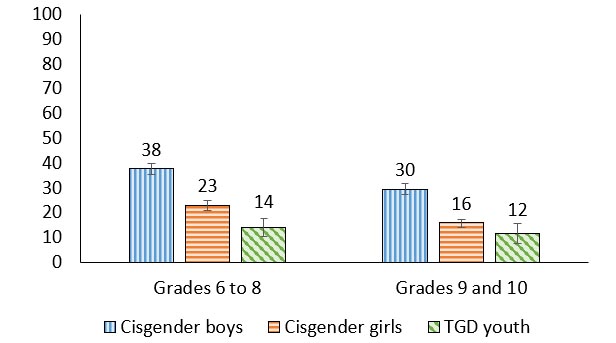

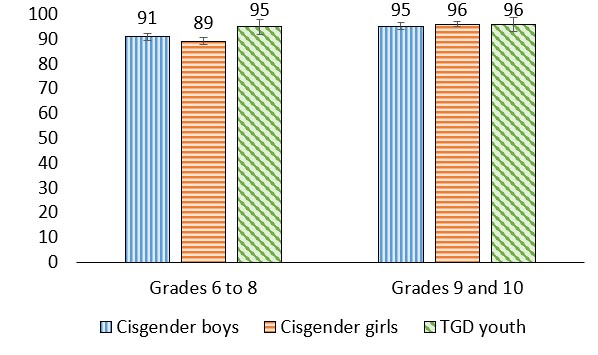

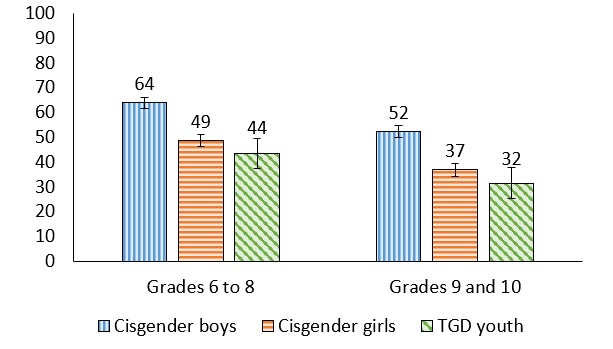

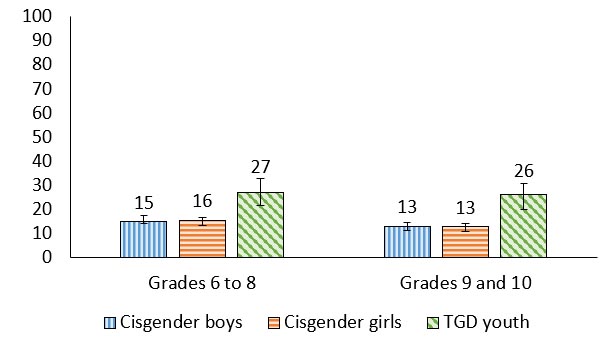

Figure 2.9. Students who strongly agreed that they had confidence in themselves, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 2.9: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 29 (27.3, 31.3) | 13 (11.9, 14.9) | 5 (2.7, 7.3) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 22 (19.8, 24.0) | 9 (7.4, 9.8) | 9 (4.8, 13.0) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Cisgender boys reported the highest levels of confidence in themselves.

- In grades 6 to 8, 5% of TGD youth reported that they had confidence in themselves, a proportion that was 8 percentage points lower than cisgender girls, and 24 percentage points lower than cisgender boys.

- In grades 9 and 10, 9% of TGD youth reported having confidence in themselves, a proportion that was similar to cisgender girls, and 13percentage points lower than cisgender boys.

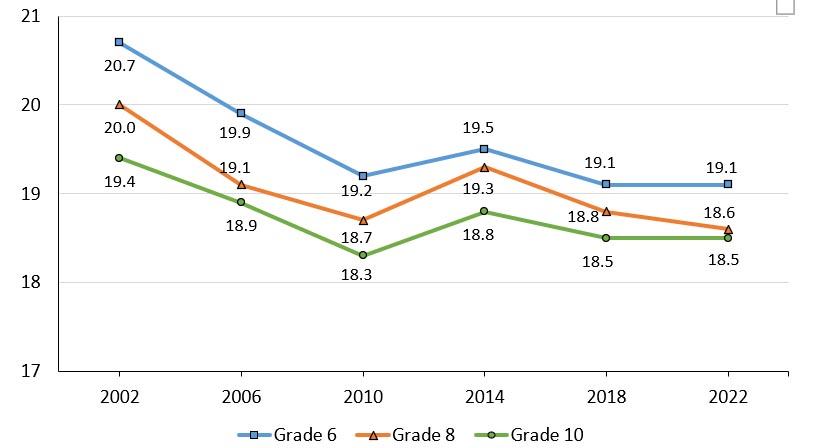

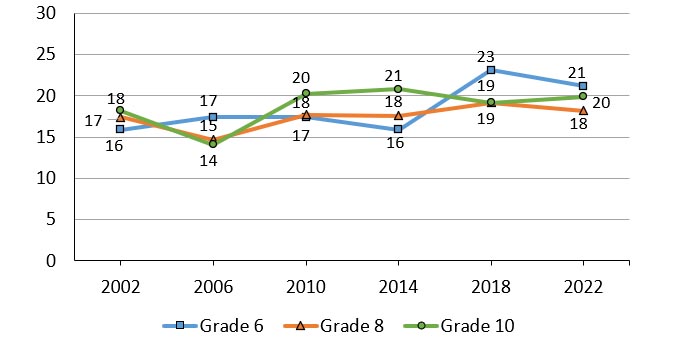

Trends in self confidence among boys

Figure 2.10. Boys who strongly agreed that they had confidence in themselves, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “boys” in all cycles.

Figure 2.10: Text description

| Grade level | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 51 | 47 | 50 | 47 | 39 | 37 |

| Grade 8 | 32 | 31 | 34 | 35 | 26 | 24 |

| Grade 10 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 22 | 19 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||||

- Over time, the proportion of boys reporting that they strongly agree they have confidence in themselves has declined. For example, in 2002, 51% of grade 6 boys reported that they strongly agreed they had confidence in themselves compared to 37% of boys in 2022.

- Grade 10 boys have consistently reported the lowest proportions of self confidence. 23% of grade 10 boys reported self confidence in 2002 which increased to 26% in 2010 and has steadily declined since, with 19% reporting this measure in 2022.

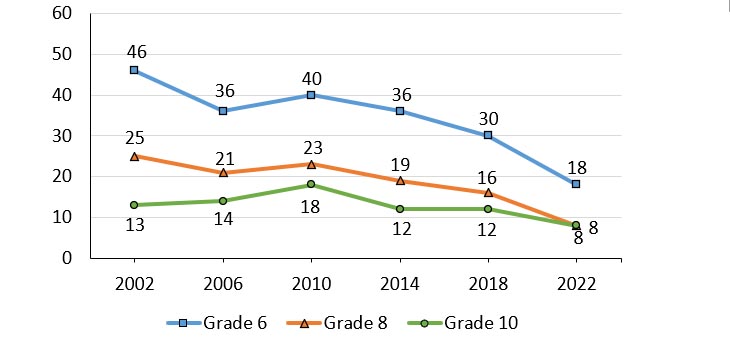

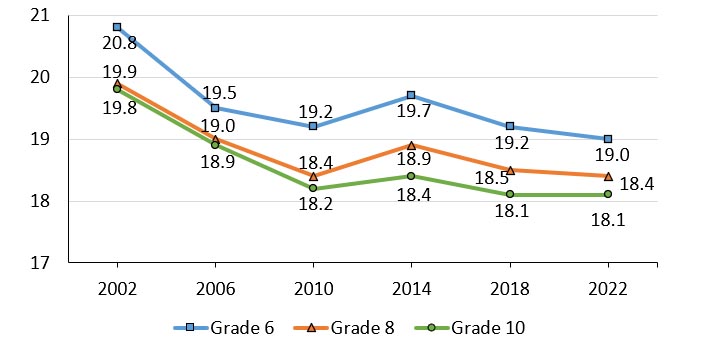

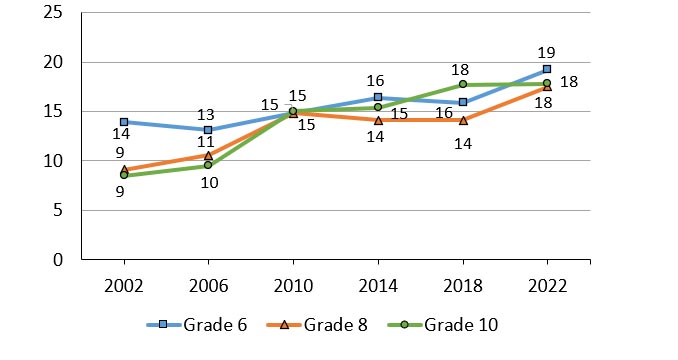

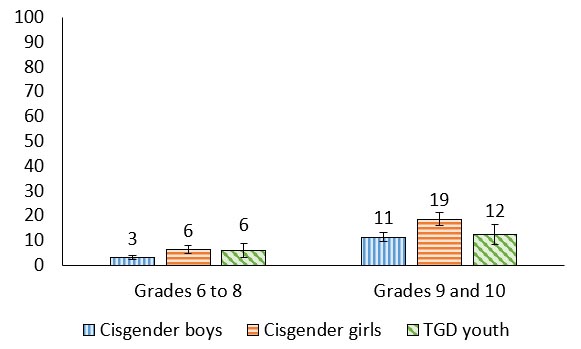

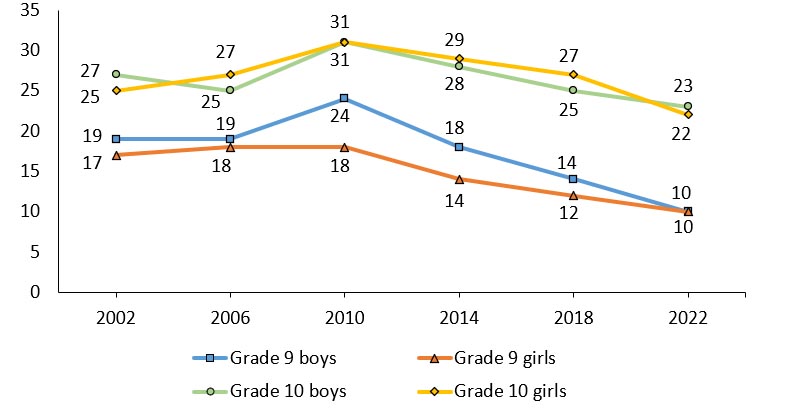

Trends in self confidence among girls

Figure 2.11. Girls who strongly agreed that they had confidence in themselves, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “girls” in all cycles.

Figure 2.11: Text description

| Grade level | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 46 | 36 | 40 | 36 | 30 | 18 |

| Grade 8 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 19 | 16 | 8 |

| Grade 10 | 13 | 14 | 18 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||||

- Over time, the proportion of girls reporting that they strongly agree they have confidence in themselves has declined. For example, in 2002, 46% of grade 6 girls reported that they strongly agreed they had confidence in themselves compared to 18% of girls in 2022.

- Generally, more girls in grade 8 reported that they had self confidence when compared to girls in grade 10. However, in 2022, an equal proportion (8%) reported that they strongly agreed they have confidence in themselves.

- Overall, girls reported lower proportions of self confidence compared to boys from 2002 to 2022.

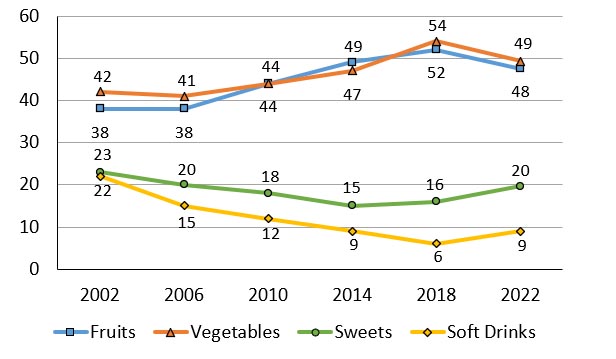

Life satisfaction

Figure 2.12. Students reporting high life satisfaction (9 or greater) on a scale of 0 to 10, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 2.12: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 30 (27.9, 32.5) | 24 (21.6, 25.7) | 9 (5.5, 11.5) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 20 (17.6, 21.6) | 11 (9.1, 12.5) | 4 (1.4, 6.7) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- In general, TGD youth reported the lowest levels of high life satisfaction, and cisgender boys reported the highest levels.

- In grades 6 to 8, 9% of TGD youth reported high life satisfaction, a proportion that was 15 percentage points lower compared with cisgender girls, and 21 percentage points lower than cisgender boys.

- In grades 9 and 10, 4% of TGD youth reported high life satisfaction, a proportion that was 7 percentage points lower than cisgender girls, and 16 percentage points lower than cisgender boys.

- High life satisfaction was reported less often in grades 9 and 10 compared with grades 6 to 8 among cisgender boys (30% vs. 20%, 10 percentage points lower), and cisgender girls (24% vs. 11%, 13 percentage points lower).

“The disparities between girls, boys, and TGD youth was something I expected based on my own experiences. TGD youth often have a harder time fitting in with their peers who are cisgender while girls often have many expectations placed upon them that may be restricting or damaging to their mental health.”

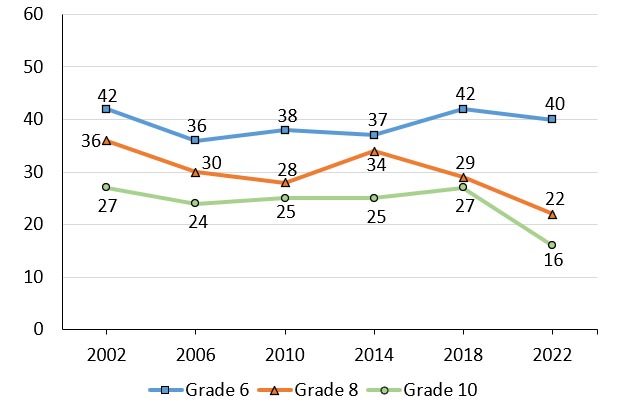

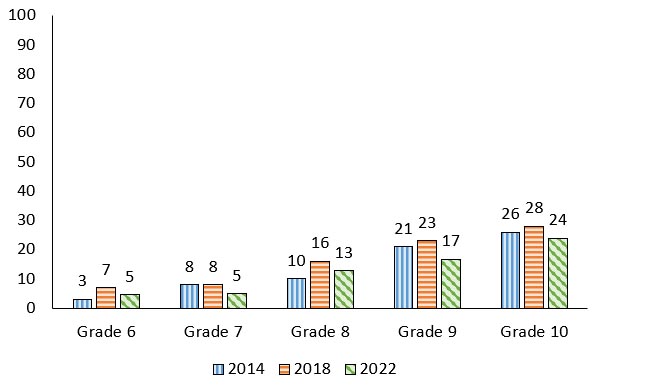

Trends in life satisfaction among boys

Figure 2.13. Boys reporting high life satisfaction (9 or greater) on a scale of 0 to 10, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “boys” in all cycles.

Figure 2.13: Text description

| Grade level | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 42 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 42 | 40 |

| Grade 8 | 36 | 30 | 28 | 34 | 29 | 22 |

| Grade 10 | 27 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 27 | 16 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||||

|

Trends in life satisfaction among girls

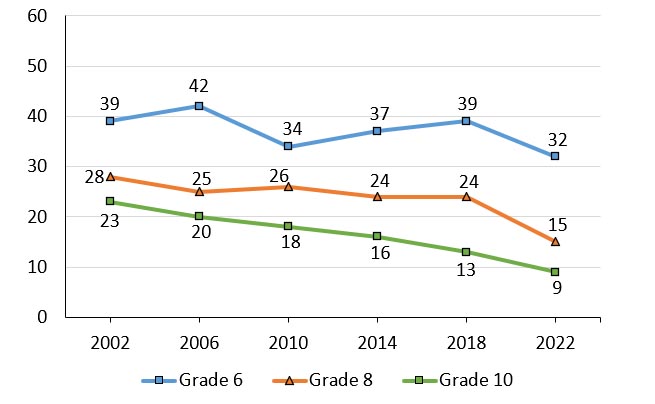

Figure 2.14. Girls reporting high life satisfaction (9 or greater) on a scale of 0 to 10, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “girls” in all cycles.

Figure 2.14: Text description

| Grade level | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 39 | 42 | 34 | 37 | 39 | 32 |

| Grade 8 | 28 | 25 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 14 |

| Grade 10 | 23 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 9 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

||||||

- Among girls in grades 8 and 10, over time, the proportion of girls reporting high levels of life satisfaction declined. For example, among girls in grade 10, the proportion declined by 14 percentage points from a high of 23% in 2002 to a low of 9% in 2022. A similar trend was observed in girls in grade 8, declining from 28% in 2002 to 15% in 2022, a 13 percentage point reduction.

- Among girls in grade 6, there was a steady increase in the proportion of girls reporting high life satisfaction between 2010 and 2018. In 2022, 32% of grade 6 girls reported high life satisfaction, the lowest proportion reported over the survey cycles.

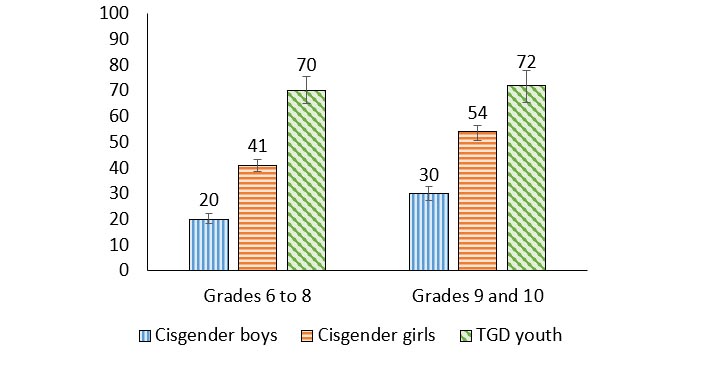

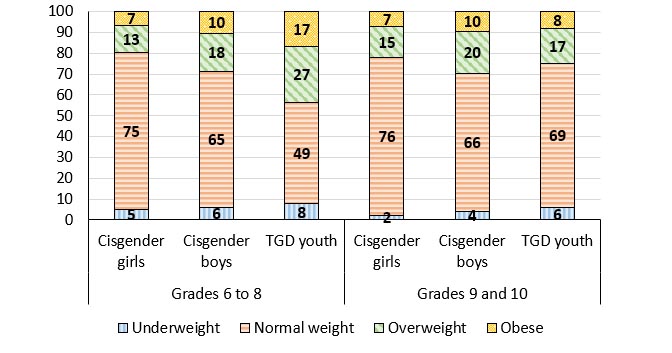

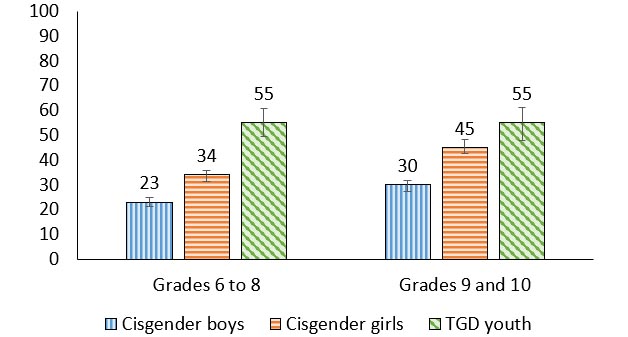

WHO-5 Well-being Index

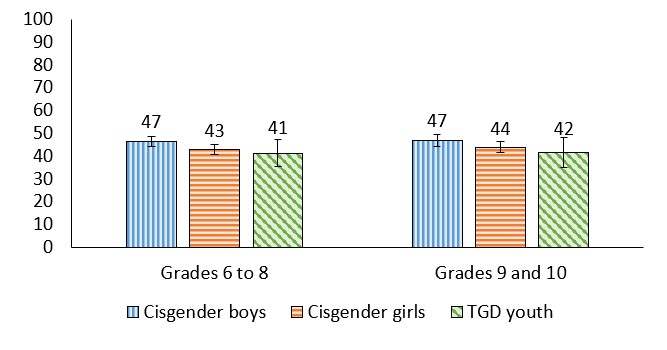

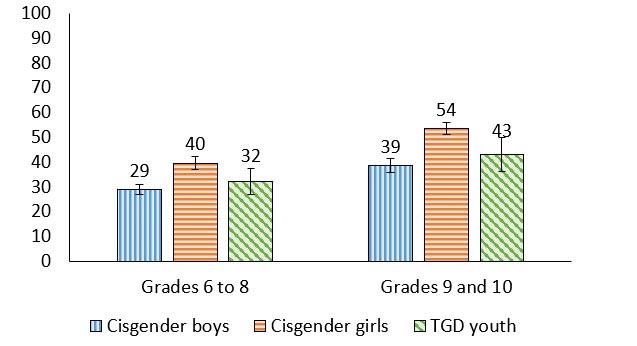

Figure 2.15. Students with poor well-being according to the WHO-5 Well-being Index

Figure 2.15: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 20 (18.5, 22.2) | 41 (38.4, 43.3) | 70 (65.0, 75.4) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 30 (27.4, 32.6) | 54 (50.8, 56.3) | 72 (65.4, 78.0) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Poor well-being was reported most commonly among TGD youth, followed by cisgender girls, then cisgender boys.

- Among grade 9 and 10 youth, 72% of TGD youth reported poor well-being, a proportion that was 18 percentage points higher than cisgender girls, and 42 percentage points higher than cisgender boys.

- A similar gender pattern was reported by grade 6 to 8 youth, with 70% of TGD youth reporting poor well-being compared to 41% of cisgender girls and 20% of cisgender boys.

Summary of findings

Encouraging findings

- Compared with cisgender girls and TGD youth, cisgender boys reported relatively high levels of positive mental health outcomes and relatively low levels of negative mental health outcomes.

Areas of concern

- Overall, TGD youth reported worse mental health outcomes when compared to their cisgender peers.

- Cisgender girls reported worse mental health outcomes than cisgender boys.

- Cisgender boys and cisgender girls who are in grades 9 and 10 reported poorer mental health than their younger counterparts.

- In general, over time, girls and boys are reporting worse mental health outcomes.

Chapter 3: Home and family

In childhood, families typically assume the primary responsibility for their children’s health by creating and fostering the caregiving environment in addition to providing the child with the resources they need to thrive.Reference 25 It is often the family context, and relationships found within it, that introduce young people to both resources and stress which has implications for health both immediately and later in life.Reference 26 Family has the potential to influence psychological, physiological, behavioural, and social pathways that intersect with health across the life course,Reference 27 deeming it an important facet in understanding young people’s lives and health trajectories. Furthermore, parents’ health promoting behaviours such as encouraging and participating in physical activity and healthy eating,Reference 28 communicating about sexual health,Reference 29 in addition to monitoring and demonstrating healthy screen timeReference 28 influence young people’s behaviours. Finally, parental support and involvement is associated with positive mental health experiences.Reference 30Reference 31

Description of items

In the HBSC survey, students are asked to report on who they live with all or most of the time. Students were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with the statements “my parent(s)/guardian(s) understand me,” “I have a happy home life” and “there are times I would like to leave home” on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Students were also asked specific questions relating to their parents. To gauge students’ ease of communication with their mother and father, youth were asked to report whether it was “very easy,” “easy,” “difficult,” or “very difficult,” to talk to them about things that really bother them. For students who are not in contact with one or both of their parents they had the option to select “don’t have or see this person.” Finally, the family support scale was used to assess family and home health. To compute this scale in its continuous form, responses to each item are added together to form a range of values from four (lower support) to 28 (higher support).

Table 3.1. Family support scale items:

- My family really tries to help me.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

- I get the emotional help and support I need from my family.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

- My family is willing to help me make decisions.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

- I can talk about my problems with my family.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

Family structure

Figure 3.1. Family Structure (%)

Figure 3.1: Text description

| Family structure | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Living with both parents | 75.1 |

| Living with mother and partner | 3.4 |

| Living with father and partner | 1.1 |

| Living with mother only | 14.1 |

| Living with father only | 3.2 |

| Other | 3.1 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|

- Approximately 75% of students in grades 6 to 10 reported living with both parents.

- 14% live with only their mother and 11% live in a different family structure.

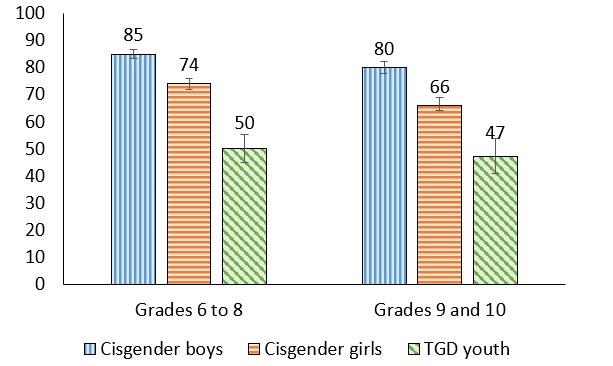

Happy home life

Figure 3.2. Students who reported that they had a happy home life, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 3.2: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 20 (18.0, 21.6) | 28 (25.5, 29.7) | 47 (41.3, 53.1) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 23 (34.3, 36.8) | 34 (20.9, 25.9) | 59 (52.2, 65.4) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Cisgender boys reported the highest percentages of having a happy home life (85% of cisgender boys in grades 6 to 8; 80% of cisgender boys in grades 9 and 10).

- TGD youth had the lowest percentages of having a happy home life (50% of TGD youth in grades 6 to 8; 47% of TGD youth in grades 9 and 10).

- In general, the prevalence of reporting a happy home life was higher in grades 6 to 8 youth compared to those in grades 9 and 10, with the greatest difference amongst cisgender girls (74% in grades 6 to 8; 66% in grades 9 and 10).

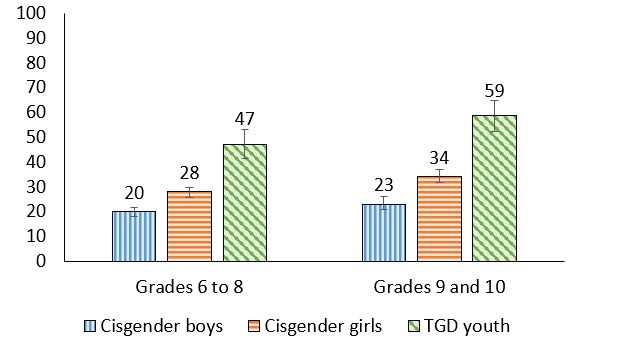

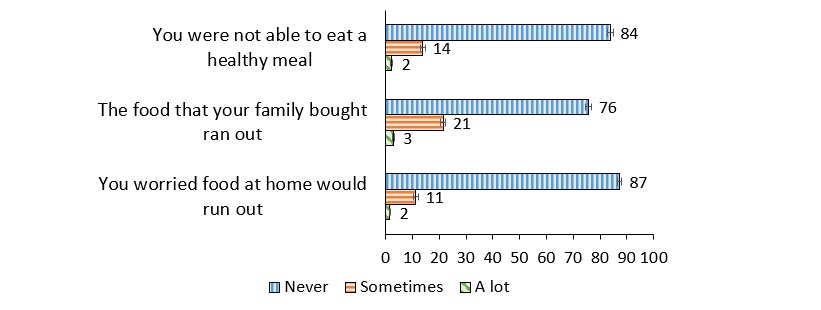

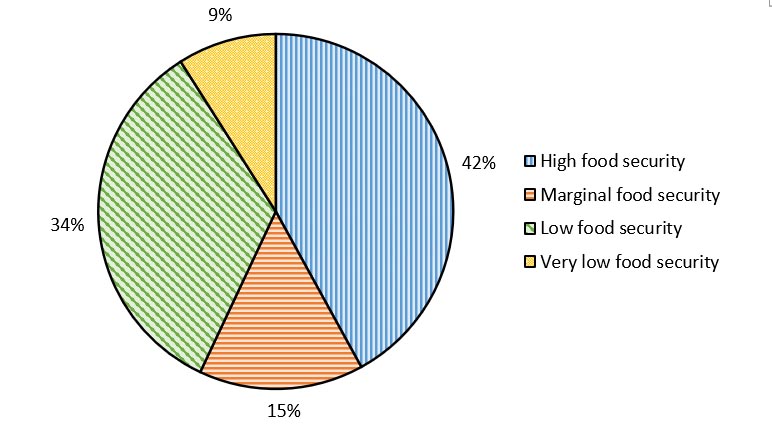

Want to leave home

Figure 3.3. Students who reported that there were times they would like to leave home, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 3.3: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 20 (18.0, 21.6) | 28 (25.5, 29.7) | 47 (41.3, 53.1) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 23 (34.3, 36.8) | 34 (20.9, 25.9) | 59 (52.2, 65.4) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Cisgender boys were least likely to report wanting to leave home (20% of cisgender boys in grades 6 to 8; 23% of cisgender boys in grades 9 and 10)

- TGD youth were most likely to report wanting to leave home (47% of TGD youth in grades 6 to 8; 59% of TGD youth in grades 9 and 10).

- Cisgender girls in grades 9 and 10 (34%) reported wanting to leave home more than cisgender girls in grades 6 to 8 (28%).

Communication with mother

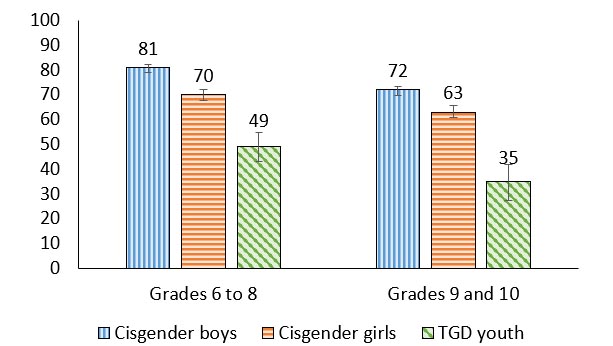

Figure 3.4. Students who reported that their mother was easy or very easy to talk to, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 3.4: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

Grades 6 to 8 |

81 (79.1, 82.4) |

70 (67.7, 72.1) |

49 (43.2, 54.8) |

Grades 9 to 10 |

72 (69.7, 73.5) |

63 (60.7, 65.5) |

35 (27.3, 41.9) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Among young people with a mother, between 35% and 81% of students felt that their mother was easy or very easy to talk to; this difference in percentages varies widely between groups.

- Ease of communication with their mother was lower in grades 9 and 10 compared to grades 6 to 8 for youth of all genders; 9 percentage points less for cisgender boys, 7 percentage points less for cisgender girls and 14 percentage points less for TGD youth.

- Regardless of grade, more cisgender boys reported ease of communication with their mother than cisgender girls and TGD youth.

Communication with father

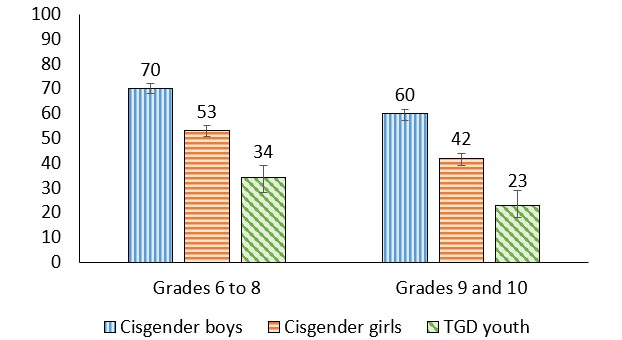

Figure 3.5. Students who reported that their father was easy or very easy to talk to, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 3.5: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 70 (67.9, 72.1) | 53 (50.6, 55.3) | 34 (28.1, 39.0) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 60 (57.2, 61.7) | 42 (39.1, 43.9) | 23 (17.9, 28.8) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Among young people with a father, between 23% and 70% of students felt that their father was easy or very easy to talk to, a difference in percentage points that is very large.

- For cisgender girls and cisgender boys, the percentage of youth reporting that their father was easy to talk to decreased by grade.

- 70% of cisgender boys in grades 6 to 8 reported their father was easy to talk to compared to 60% in grades 9 and 10. Similarly, 53% of cisgender girls in grades 6 to 8 reported that it was easy to talk to their father compared to 42% in grades 9 and 10.

- Regardless of grade, more cisgender boys reported ease of communication with their father than cisgender girls and TGD youth.

Trends in feeling understood by parents among boys

Figure 3.6. Boys who reported that they were understood by their parents, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “boys” in all survey cycles.

Figure 3.6: Text description

| Grade level | 1990 | 1994 | 1998 | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 66 | 78 | 76 | 91 | 90 | 90 | 87 | 87 | 84 |

| Grade 8 | 56 | 62 | 64 | 83 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 73 |

| Grade 10 | 51 | 50 | 53 | 72 | 66 | 72 | 71 | 75 | 65 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

|||||||||

- Between 1990 and 2002, increasing proportions of boys in grades 6, 8 and 10 reported feeling understood by their parents. Beyond 2002, a gradual decline in these reports of feeling understood by parents were reported for each of the three grade levels of boys.

- Overall, in 2022, fewer boys in grades 6, 8, and 10 reported feeling understood by their parents than in the previous five cycles of the HBSC survey (2002-2018).

- In general, the proportion of boys that reported feeling understood by their parents decreased with grade. For example, in 2022, 84% of grade 6 boys reported feeling understood by their parents compared to 73% of grade 8 boys and 65% of grade 10 boys.

Trends in feeling understood by parents among girls

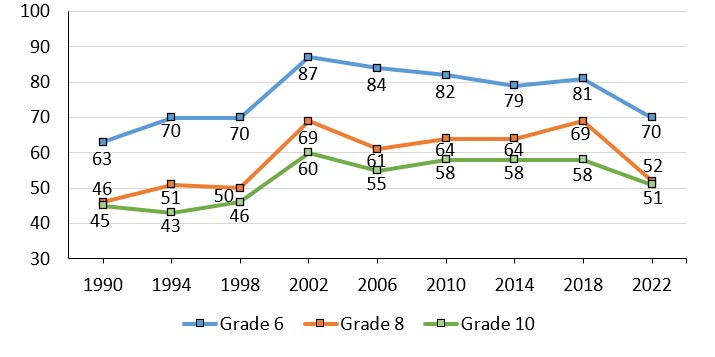

Figure 3.7. Girls who reported that they were understood by their parents, by grade and year of survey (%)

Note: When considering the above trends, estimates are provided for young people identifying as “girls” in all cycles.

Figure 3.7: Text description

| Grade level | 1990 | 1994 | 1998 | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 63 | 70 | 70 | 87 | 84 | 82 | 79 | 81 | 70 |

| Grade 8 | 46 | 51 | 50 | 69 | 61 | 64 | 64 | 69 | 52 |

| Grade 10 | 45 | 43 | 46 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 51 |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada |

|||||||||

- Between 1990 and 2002, increasing proportions of girls in grades 6, 8 and 10 reported feeling understood by their parents. Beyond 2002, a gradual decline in these reports of feeling understood by parents were reported for each of the three grade levels of girls.

- Overall, in 2022, fewer girls in grades 6, 8, and 10 reported feeling understood by their parents than in the previous five cycles of the HBSC survey (2002-2018).

- In 2022, the proportion of girls in grades 6, 8, and 10 that reported they were understood by their parents significantly declined when compared to 2018. Among girls in grade 6 there was an 11 percentage point reduction (81% in 2018 to 70% in 2022), girls in grade 8 had an 17 percentage point reduction (69% in 2018 to 52% in 2022), and a 7 percentage point reduction (58% in 2018 to 51% in 2022) was reported amongst grade 10 girls.

- Typically, the proportion of girls that felt understood by their parents decreased with grade. However, in 2022, approximately the same proportion of grade 8 and grade 10 girls reported feeling understood by their parents.

- Compared to boys, a consistently lower proportion of girls reported that they were understood by their parents.

“This increase in cisgender girls reporting feeling less understood in grade 8 was a common theme amongst my classmates. Most youths as new teenagers start to participate in behaviours like drinking, social media use, and using makeup. These behaviors can be seen as problematic in different family structures and parents causing more conflict resulting in cisgender girls feeling less understood by their parents.”

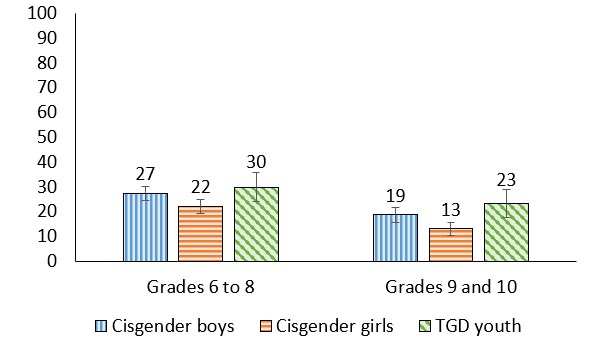

Family support

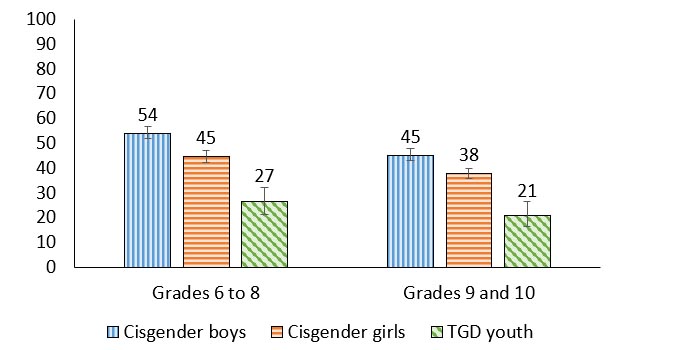

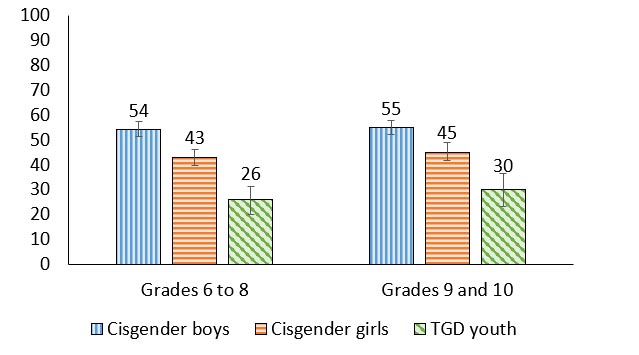

Figure 3.8 Students reporting high family support, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 3.8: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 54 (52.0, 56.9) | 45 (42.2, 47.2) | 27 (21.1, 32.0) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 45 (42.9, 47.7) | 38 (35.6, 39.7) | 21 (16.5, 26.5) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- In general, TGD youth had the lowest proportion reporting high family support, and cisgender boys had the highest proportion.

- In grades 6 to 8, 27% of TGD youth reported high family support, a proportion that was 18 percentage points lower than cisgender girls and 27 percentage points lower than cisgender boys. This gendered pattern of decline was also seen amongst grades 9 and 10 students.

- The proportion of youth reporting high family support was lower in grades 9 and 10 compared to grades 6 to 8 among cisgender boys (45% vs 54%), and cisgender girls (38% vs 45%).

Happy home life and mental health

| Gender | Grade | Affluence | Positive indicators | Negative indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | WHO-5 Well-being | Lonely | Health complaints | |||

| Cisgender boys | 6 to 8 |

Less |

.61 |

.61 |

-.48 |

-.44 |

More |

.51 |

.51 |

-.40 |

-.31 |

||

9 and 10 |

Less |

.52 |

.47 |

-.34 |

-.37 |

|

More |

.46 |

.46 |

-.33 |

-.28 |

||

| Cisgender girls | 6 to 8 |

Less |

.72 |

.67 |

-.60 |

-.53 |

More |

.56 |

.51 |

-.38 |

-.36 |

||

9 and 10 |

Less |

.54 |

.52 |

-.50 |

-.51 |

|

More |

.53 |

.44 |

-.37 |

-.38 |

||

| TGD youth | 6 to 8 | Both affluence groups | .58 | .42 | -.42 | -.40 |

| 9 and 10 | .48 | .50 | -.27 | -.35 | ||

| Both grade groups | Less | .64 | .40 | -.38 | -.38 | |

| More | .49 | .47 | -.33 | -.37 | ||

| Overall | .57 | .53 | -.44 | -.42 | ||

- Overall, reporting a happy home life was consistently associated with the mental health indicators. Having a happy home life was positively associated with life satisfaction and well-being, and negatively associated with loneliness and health complaints, for students in all grades, of all genders, and for all levels of affluence.

- Happy home life was more strongly related to the positive mental health indicators, compared to the negative mental health indicators.

- Broadly, for cisgender boys and cisgender girls who are less affluent in grades 6 to 8 there is a stronger relationship between happy home life and the positive mental health indicators, relative to their older and more affluent peers.

- Among TGD youth who are less affluent, happy home life was most strongly correlated with life satisfaction.

Family support and mental health

| Gender | Grade | Affluence | Positive indicators | Negative indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | WHO-5 Well-being | Lonely | Health complaints | |||

| Cisgender boys | 6 to 8 | Less | .38 | .35 | -.36 | -.41 |

| More | .28 | .25 | -.24 | -.22 | ||

| 9 and 10 | Less | .45 | .41 | -.24 | -.38 | |

| More | .24 | .27 | -.23 | -.24 | ||

| Cisgender girls | 6 to 8 | Less | .56 | .43 | -.45 | -.35 |

| More | .43 | .39 | -.36 | -.35 | ||

| 9 and 10 | Less | .45 | .54 | -.38 | -.29 | |

| More | .41 | .31 | -.32 | -.31 | ||

| TGD youth | 6 to 8 | Both affluence groups | .46 | .42 | -.24 | -.37 |

| 9 and 10 | .38 | .37 | -.23 | -.38 | ||

| Both grade groups | Less | .39 | .46 | -.18 | -.43 | |

| More | .43 | .40 | -.25 | -.37 | ||

| Overall | .39 | .36 | -.33 | -.34 | ||

- Overall, family support was consistently associated with the mental health indicators. Family support was positively associated with life satisfaction and well-being and negatively associated with loneliness and health complaints, for students in all grades, of all genders, and for all levels of affluence.

- Family support was more strongly related to the positive mental health indicators, compared to the negative mental health indicators.

- For cisgender girls, family support was moderately positively associated with life satisfaction. For less affluent cisgender girls, family support was moderately positively associated with well-being.

- For cisgender boys, except those in grades 9 and 10 who are less affluent, family support had a weak correlation with the positive mental health indicators.

- Among TGD youth, those who are younger and more affluent had stronger associations between family support and the positive mental health indicators compared to the negative mental health indicators.

Summary of findings

Encouraging findings

- Cisgender boys reported relatively high levels of positive home and family measures and relatively low levels of negative home and family measures.

- 80-85% of cisgender boys reported having a happy home life.

- Reporting a happy home life was strongly correlated with life satisfaction and well-being for some youth, especially those who are younger. Additionally, having a happy home life was moderately correlated with many of the mental health indicators for most students.

Areas of concern

- TGD youth reported significantly worse home and family measures than their cisgender counterparts.

- 47%-59% of TGD youth reported wanting to leave home.

- When compared to 2018, boys and girls reported feeling less understood by their parents in 2022. This finding is especially prominent among grade 8 girls.

- Broadly, as youth get older, they reported smaller proportions of home and family measures that are indicative of positive health outcomes, including family support and happy home life.

"More gender diverse youth want to leave home because their parents don’t accept them or make them feel wanted."

Chapter 4: Friends

Relationships with friends are important throughout the school-aged years and become increasingly significant throughout adolescence. As children develop, their friendships evolve from being play-focused to offering the opportunity for increased closeness and intimacy.Reference 32 For many young people, their connection to friends exists in both their physical environments, such as school, and within virtual spaces such as social media.Reference 32

Friends have a direct influence on adolescents’ behaviours.Reference 33Reference 34 Friends that have a higher involvement in risk behaviours, including binge drinkingReference 35 and substance use,Reference 36 have a higher probability of negatively influencing their peers while friends that participate in more protective behaviours have a higher probability of positively influencing their peers.Reference 34 With respect to mental health, supportive peer relationships act as a protective factor with positive social connections predicting lower rates of depressionReference 37 and anxiety,Reference 38 in addition to buffering the negative effects of stress.Reference 39

Description of items

In the HBSC survey, relationships with friends are measured through various questions and scales. First, the friend support scale is used to assess how supportive students feel their friends are. To compute this scale in its continuous form, responses to each item are added together to form a range of values from four (lower support) to 28 (higher support). Questions regarding communication with friends are assessed based on ease of communication and frequency of communicating online throughout the day. Additionally, the students in grades 9 and 10 were asked to report on the positive and risky peer group activities that their friends participated in. The risky peer group activities in Table 4.3 (smoke cigarettes, get drunk at least once a week, have used drugs to get high, and vape) were added together to form a scale with values ranging from four (lowest level) to 20 (highest level).

Table 4.1 Friend support scale items:

- My friends really try to help me.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

- I can count on my friends when things go wrong.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

- I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

- I can talk about my problems with my friends.

- 1=Very strongly disagree

- 7=Very strongly agree

Positive peer group attributes

| Item | Grades 9 and 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth | |

| Do well at school | 58 | 63 | 53 |

| Participate in organized sports activities with others | 43 | 41 | 23 |

| Participate in cultural activities other than sports | 17 | 16 | 17 |

| Get along well with their parents | 64 | 53 | 29 |

- The most prevalent positive attribute reported by cisgender boys was that their friends get along well with their parents (64%).

- 63% of cisgender girls and 53% of TGD youth reported that their friends do well at school.

- The least prevalent positive peer group attribute among all students was participation in cultural activities other than sports. 16% of cisgender girls and 17% of cisgender boys and TGD youth reported that their friends participate in such cultural activities.

- TGD youth, compared to cisgender youth, had the smallest proportions of their friends doing well in school, participating in organized sports, and getting along well with their parents.

Risky peer group activities

| Item | Grades 9 and 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth | |

| Smoke cigarettes | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Get drunk at least once a week | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Have used drugs to get high | 10 | 13 | 14 |

| Vaping | 12 | 19 | 14 |

- For cisgender boys and cisgender girls, vaping was the most prevalent risky peer group activity. 19% of cisgender girls and 12% of cisgender boys reported that their friend group engaged in vaping.

- For TGD youth, using drugs to get high and vaping were the most prevalent risky peer group activity. 14% of TGD youth reported that their group of friends engaged in using drugs to get high, with similar proportions reporting engagement in vaping.

- Relative to cisgender girls and TGD youth, cisgender boys had the lowest proportion of their friends participating in smoking cigarettes (3%), using drugs to get high (10%), and vaping (12%).

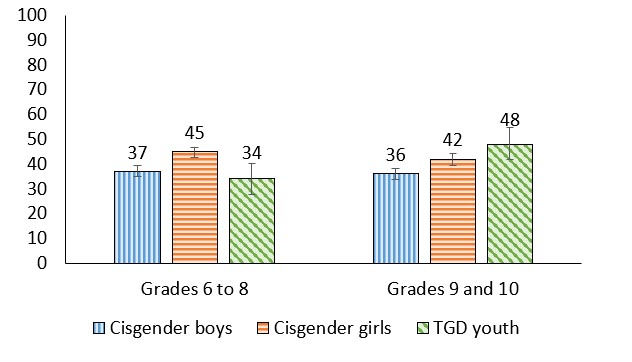

Friend support

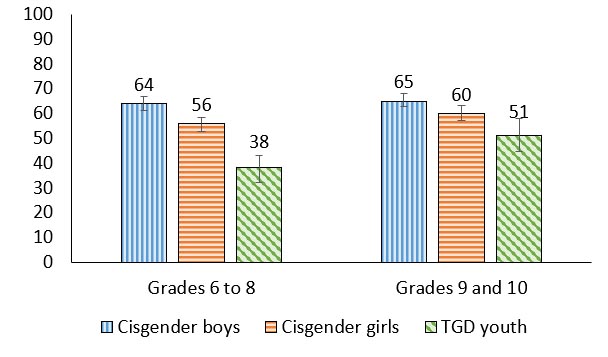

Figure 4.1. Students reporting high friend support, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 4.1: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 37 (35.0, 39.3) | 45 (42.5, 46.8) | 34 (27.5, 40.3) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 36 (33.7, 38.1) | 42 (39.5, 44.0) | 48 (41.8, 54.6) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- In grades 6 to 8, 45% of cisgender girls reported high friend support, a proportion that was 8 percentage points higher than cisgender boys and 11 percentage points higher than TGD youth.

- In grades 9 and 10, 36% of cisgender boys reported high friend support, a proportion that was 6 percentage points lower than cisgender girls and 12 percentage points lower than TGD youth.

“As a gender queer youth, there is not a lot of support for me, I stick with my friends who also fit in this category. We are a tight-knit group. If you are out, like looking at clothing appearance, then you are pressured to dress a certain way or questioned. It’s hard to deal with that and be normal.”

Online communication with close friends

Figure 4.2. Students who reported they have online contact with close friend(s) almost all the time throughout the day, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 4.2: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 42 (39.8, 44.3) | 54 (51.4, 56.2) | 45 (38.4, 50.9) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 57 (54.5, 60.0) | 73 (70.4, 74.8) | 61 (54.7, 67.5) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- The proportion of cisgender boys and cisgender girls reporting they have online contact with close friend(s) almost all the time throughout the day was higher in grades 9 and 10 compared to grades 6 to 8.

- The proportion increase by grade in online contact with close friend(s) was most prominent among cisgender girls, from 54% reporting online contact almost all the time in grades 6 to 8 to 73% of cisgender girls in grades 9 and 10, a 19 percentage point increase.

- In grades 6 to 8, 42% of cisgender boys reported they have online contact with close friend(s) almost all the time throughout the day, a proportion that was 12 percentage points lower than cisgender girls.

- In grades 9 and 10, 73% of cisgender girls reported they have online contact with close friend(s) almost all the time throughout the day, a proportion that was 16 percentage points higher than cisgender boys and 12 percentage points higher than TGD youth.

“A good amount of time, my friends are with me at school, but we still talk online. On the weekend I might talk to them more online because I can’t see them in person.”

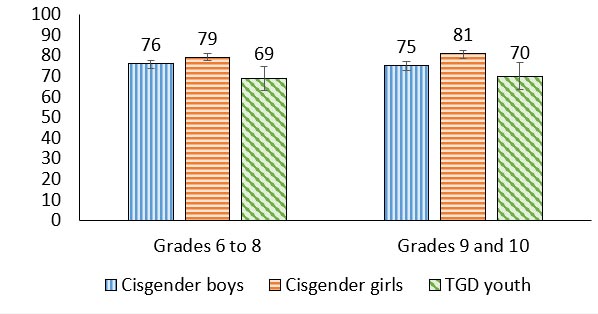

Ease of communication with best friend

Figure 4.3. Students who reported they find it easy to talk to their best friend about things that really bother them, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 4.3: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 76 (73.8, 77.7) | 79 (77.5, 81.3) | 69 (63.1, 74.6) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 75 (73.0, 77.2) | 81 (78.5, 82.5) | 70 (63.5, 76.7) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Across all grade groups, cisgender girls most frequently reported that it was easy to talk to their best friend about things that really bothered them, compared to cisgender boys and TGD youth.

- In grades 6 to 8, 79% of cisgender girls reported it was easy to talk to their best friend about things that really bothered them, a proportion that was 10 percentage points higher than TGD youth.

- In grades 9 and 10, 81% of cisgender girls reported that it was easy to talk to their best friend about things that really bothered them, a proportion that was 6 percentage points higher than cisgender boys and 11 percentage points higher than TGD youth.

Risky peer behaviours and mental health

| Gender | Grade | Affluence | Positive indicators | Negative indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | WHO-5 Well-being | Lonely | Health complaints | |||

| Cisgender boys | 9 and 10 | Less | -.30 | -.26 | .39 | .47 |

| More | -.13 | -.07 | .13 | .12 | ||

| Cisgender girls | 9 and 10 | Less | -.22 | -.24 | .33 | .47 |

| More | -.24 | -.20 | .28 | .33 | ||

| TGD youth | 9 and 10 | Both affluence groups | NS | -.17 | NS | .19 |

| Less | NS | NS | NS | .25 | ||

| More | NS | -.16 | NS | .13 | ||

| Overall | -.21 | -.18 | .24 | .28 | ||

- Overall, risky peer behaviours were negatively correlated with life satisfaction and well-being, and positively correlated with loneliness and health complaints, for all students.

- For cisgender girls and cisgender boys who are less affluent, risky peer behaviours were most strongly correlated with health complaints.

- Cisgender girls had the strongest correlations between risky peer behaviours and the mental health indicators compared to cisgender boys and TGD youth.

Friend support and mental health

| Gender | Grade | Affluence | Positive indicators | Negative indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | WHO-5 Well-being | Lonely | Health complaints | |||

| Cisgender boys | 6 to 8 | Less | .12 | .18 | -.10 | -.16 |

| More | .23 | .27 | -.22 | -.15 | ||

| 9 and 10 | Less | NS | NS | -.16 | -.19 | |

| More | .16 | .23 | -.12 | -.10 | ||

| Cisgender girls | 6 to 8 | Less | .33 | .24 | -.35 | -.20 |

| More | .27 | .27 | -.31 | -.22 | ||

| 9 and 10 | Less | .18 | .27 | -.32 | -.16 | |

| More | .18 | .20 | -.24 | -.13 | ||

| TGD youth | 6 to 8 | .12 | .21 | -.10 | NS | |

| 9 and 10 | NS | .16 | -.19 | NS | ||

| Less | NS | .16 | NS | .15 | ||

| More | .12 | .19 | -.13 | NS | ||

| Overall | .20 | .21 | -.20 | -.12 | ||

- Overall, friend support was positively associated with increased life satisfaction and well-being, and negatively associated with loneliness and health complaints for most youth. Such correlations were strongest for cisgender girls.

“If you don’t identify as a girl or boy you are automatically outcasted by people at school.”

Summary of findings

Encouraging findings

|

Areas of concern

- 3%-19% of students reported that their friends participate in risky peer group activities (i.e. smoke cigarettes, get drunk at least once a week, use drugs to get high, vape). This is especially concerning for cisgender girls and cisgender boys who are less affluent, as risky peer behaviours were moderately positively correlated with health complaints for this group of young people.

Chapter 5: School

School climate encompasses academic, community, safety, and institutional environments that contribute to students’ experiences at school.Reference 40 School climates influence all aspects of student health, including mental health. For example, positive relationships with peers and teachers have been associated with increases in psychosocial well-being, and positive perceptions regarding school safety have been associated with decreases in engagement in risk behaviours.Reference 41

When students are at school, they can interact with peers, staff and teachers while also learning valuable life skills. When students get along with their teachers, they report fewer depressive symptomsReference 42 and when teachers have better well-being themselves, students have better well-being and lower psychological distress.Reference 43 Teachers also act as advocates for their students in the classroomReference 44Reference 45 indicating they have the potential to facilitate or impede students having their health needs met in the school environment.Reference 46

Description of items

In the HBSC survey, students were asked to report on various indicators describing their school environment, including questions relating to their teachers, classmates, schoolwork, and their overall enjoyment. The school climate scale is a composite measure of four items related to student’s perceptions of their school environments. To compute this scale in its continuous form, responses to each item are added together to form a range of values from four (lower school climate) to 20 (higher school climate). Perceptions of having caring teachers were evaluated by asking students how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement “I feel that my teachers care about me as a person” on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree).

Table 5.1. School climate scale items:

- How do you feel about school at present?

- 1= I don’t like it at all

- 2= I don’t like it very much

- 3=I like it a bit

- 4=I like it a lot

- Our school is a nice place to be.

- 1= Strongly disagree

- 2= Disagree

- 3= Neither agree nor disagree

- 4= Agree

- 5= Strongly agree

- I feel I belong at this school.

- 1= Strongly disagree

- 2= Disagree

- 3= Neither agree nor disagree

- 4= Agree

- 5= Strongly agree

- The rules in this school are fair.

- 1= Strongly disagree

- 2= Disagree

- 3= Neither agree nor disagree

- 4= Agree

- 5= Strongly agree

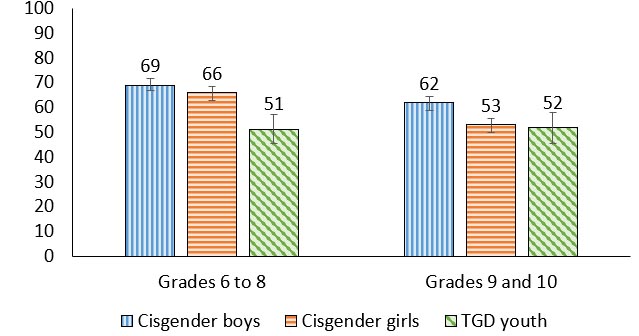

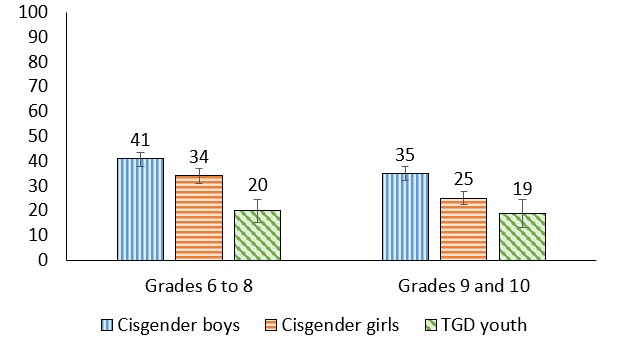

Caring teachers

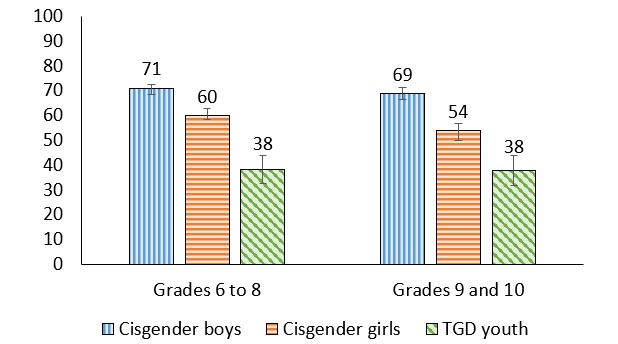

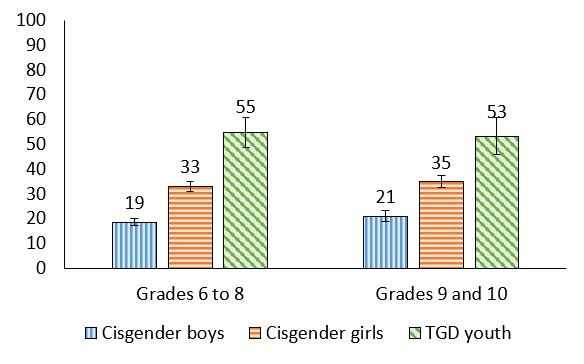

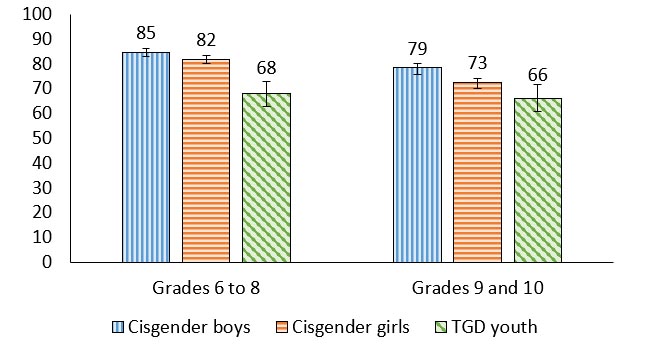

Figure 5.1. Students who reported that they felt that their teachers cared about them as persons, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 5.1: Text description

| Grade level | Cisgender boys | Cisgender girls | TGD youth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | 69 (66.9, 71.7) | 66 (62.8, 68.4) | 51 (45.3, 57.0) |

| Grades 9 to 10 | 62 (59.0, 64.3) | 53 (49.8, 55.4) | 52 (45.3, 57.8) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

|||

- Overall, more than half of youth reported that they felt their teachers cared about them.

- For cisgender girls and cisgender boys, the percentage of youth reporting that they felt their teachers cared about them decreased with increasing grade level.

- The proportion of TGD youth who reported that they felt that their teachers cared about them was lower than cisgender boys and cisgender girls in grades 6 to 8

- 62% of cisgender boys in grades 9 and 10 reported that they felt their teachers cared about them, which was 9 percentage points higher than cisgender girls and 10 percentage points higher than TGD youth.

“To people who work in schools - Checking in on your students is important! School is basically a second home whether we want to or not, and it's the staff's job and priority to make that place comfortable and safe for the students. If school caused less distress on students, whether that's by adjusting lessons to their needs or lending an ear to them, it could bring down some of the stats found in the mental health chapter. A positive environment generates a positive mindset/mental health. Also, safe spaces for TGD youth is super beneficial to them!”

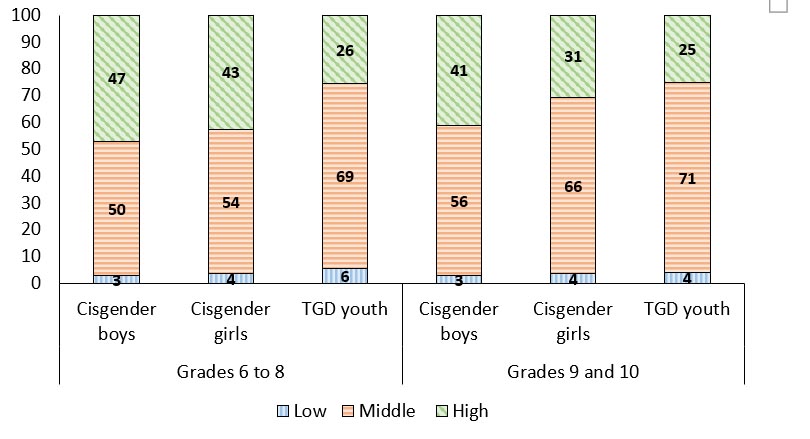

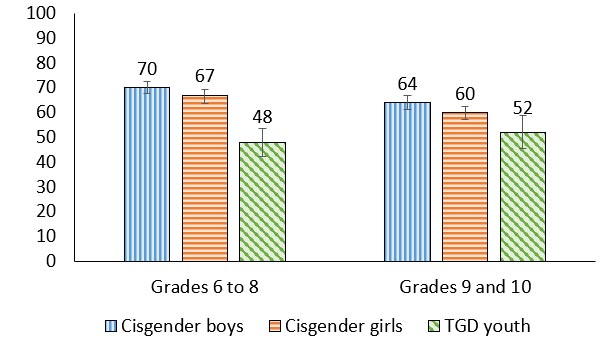

Teacher support

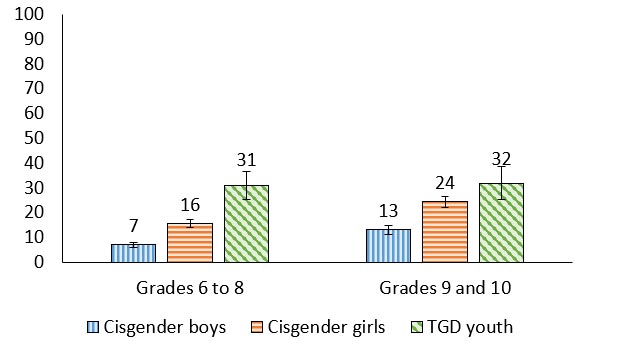

Figure 5.2. Students reporting different levels of perceived teacher support, by grade and gender (%)

Figure 5.2: Text description

| Grade level | Gender | Low | Middle | High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grades 6 to 8 | Cisgender Boys | 3 | 50 | 47 |

| Cisgender Girls | 4 | 54 | 43 | |

| TGD Youth | 6 | 69 | 26 | |

| Grades 9 to 10 | Cisgender Boys | 3 | 56 | 41 |

| Cisgender Girls | 4 | 66 | 31 | |

| TGD Youth | 4 | 71 | 25 | |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2022 |

||||

- Regardless of grade, TGD youth were least likely to report high teacher support (26% of TGD youth in grades 6 to 8; 25% of TGD youth in grades 9 and 10) compared to cisgender boys and cisgender girls.

- Cisgender boys were most likely to report high teacher support (47% of cisgender boys in grades 6 to 8; 41% of cisgender boys in grades 9 and 10) compared to cisgender girls and TGD youth.

- The proportion of cisgender boys and cisgender girls who reported high teacher support decreased in the older grade levels. 41% of cisgender boys in grades 9 to 10 reported high levels of teacher support compared to 47% in grades 6 to 8. Similarly, 31% of cisgender girls in grade 9 to 10 reported high levels of teacher support compared to 43% in grade 6 to 8.

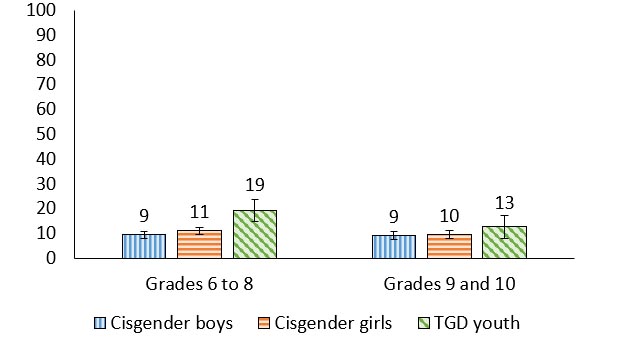

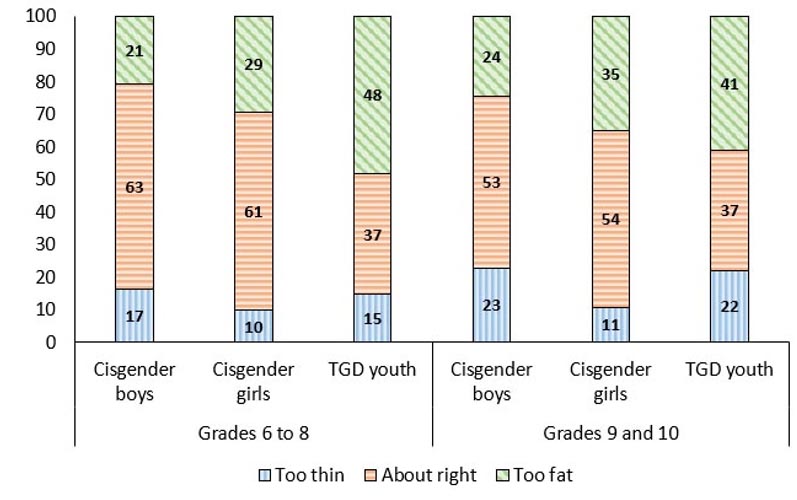

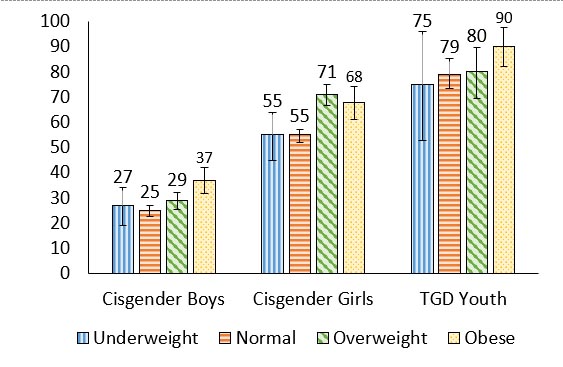

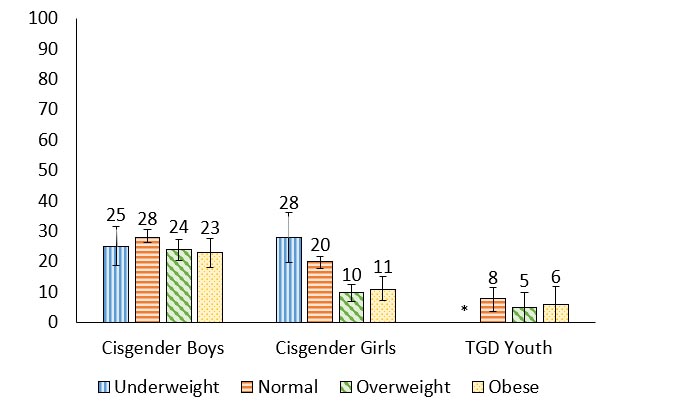

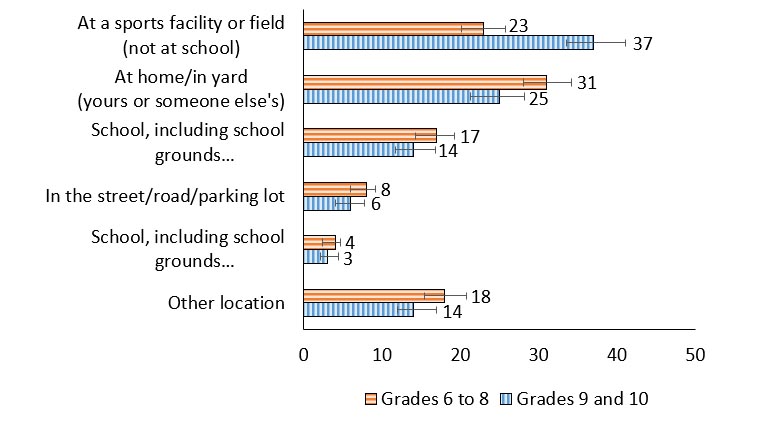

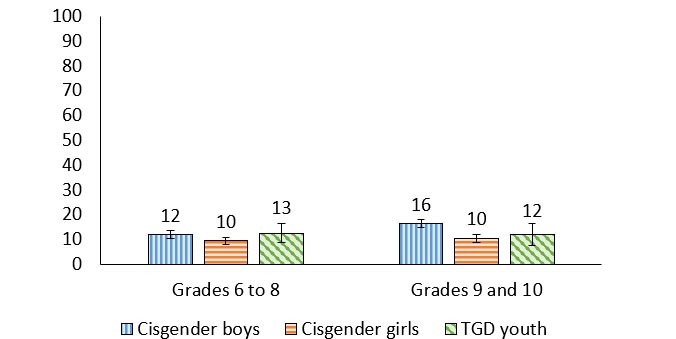

- Overall, 3% to 6% of students reported low levels of teacher support.