Rabies prevention and control in Weeneebayko Area Health Authority

Download this article as a PDF (205 KB - 5 pages)

Download this article as a PDF (205 KB - 5 pages) Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 42-6: Rabies

Date published: June 2, 2016

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 42-6, June 2, 2016: Rabies

Implementation science

Northern innovation in rabies prevention and control: The Weeneebayko Area Health Authority (WAHA) dog population management pilot project

Lidstone-Jones C1*, Gagnon R1

Affiliation

1 Weeneebayko Area Health Authority, Moose Factory, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Lidstone-Jones C, Gagnon R. Northern innovation in rabies prevention and control: The Weeneebayko Area Health Authority (WAHA) dogs population management pilot project. Can Comm Dis Rep 2016;42:130-4. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v42i06a04

Abstract

Background: Remote northern communities in Ontario face unique challenges in rabies prevention and control. With large, free-roaming dog populations at high risk of exposure to rabies from wildlife, and a lack of regular access to veterinary services and vaccinations, these communities run a higher risk of human exposure to rabies than southern regions of the province.

Objective: To provide the baseline data on a novel approach to controlling the dog population in the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority (WAHA) in northern Ontario, implemented as part of a sustainable, humane and cost-effective pilot project to manage dog population numbers and improve public safety.

Intervention: In 2015, WAHA launched a large-scale two-year regional project that involved microchipping all dogs in the region to quantify and monitor population levels, vaccinating them with canine core vaccinations (including rabies) and piloting the use of an injectable ganodotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist contraceptive implant in female dogs. The Project’s objectives included control of dog population numbers, reducing aggressive behaviours in community dogs, reducing the risk of rabies in communities, improving the health of community dogs and educating community members about the importance of dog population control.

Outcomes: In 2015, 513 dogs were microchipped and vaccinated as part of the WAHA Project: 211 females and 301 males. Seventy-six intact, free-roaming females were given the contraceptive implant, 113 females were identified as previously spayed and only 22 females were either too young or too small (toy breeds) to receive an implant.

Conclusion: While the final outcomes of the WAHA Project are still pending, preliminary findings, including dog population demographics and observed dynamics, support the feasibility of contraceptive implants in female dogs as a primary intervention to quickly and cost-effectively reduce dog population numbers in remote northern regions and reduce the risk of rabies transmission.

Introduction

The need to advance rabies prevention and control programs in remote northern Ontario communities came to the fore in the spring of 2013, when a puppy on the Kashechewan First Nations reserve was diagnosed with the Arctic fox strain of rabies, which is endemic in the region.

Kashechewan is a fly-in community located on Ontario’s James Bay coastline, served by the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority (WAHA).

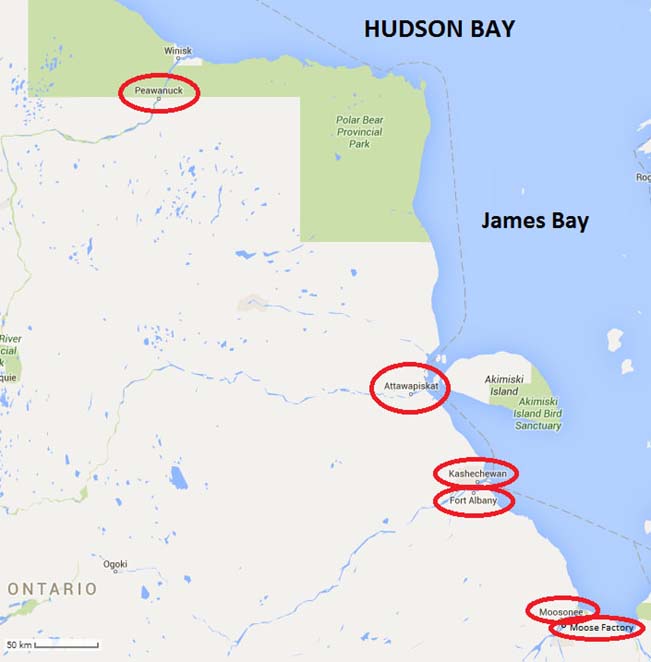

WAHA oversees medical services and facilities for four communities of Ontario’s James Bay and Hudson Bay coastal regions, including Moosonee, Moose Factory, Fort Albany and Attawapiskat, and provides clinical support to the Kashechewan and Peawanuck Health Canada Nursing Stations. Prior to the incident with the puppy, WAHA had identified the need to address dog overpopulation and reduce zoonotic disease risks as a priority in its integrated model of public health service delivery.

In 2013, a routine response to the identification of the rabid puppy in Kashechewan proved extremely difficult. This was due to a lack of veterinary resources and rabies vaccinations, coupled with the absence of sustainable dog population management strategies. It was further complicated by lack of access to reliable information on the size of the dog population at risk. Additional challenges included reliably identifying, confining and monitoring dog contacts of the rabid puppy in Kashechewan, as well as ensuring that all other community dogs were vaccinated to prevent any further spread of the disease.

These challenges served to bring together a number of key government and animal health partners to collaborate on an innovative regional solution. The WAHA Dog Population Management Pilot Project (WAHA Project) came into being as a partnership between WAHA, each of the individual communities of the region, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Health Canada, the Porcupine Health Unit and Dogs With No Names, a pioneer organization in the use of alternative approaches to canine contraception in Canada. WAHA’s region spans the entire western coastline of James Bay, as well as a portion of the Hudson Bay coast as far as Peawanuck (Winisk), with communities scattered along the coastline, as shown in Figure 1 below, and a human population of approximately 11,860.

Figure 1: Map of Ontario’s Hudson Bay and James Bay coastal region, with communities served by Weeneebayko Area Health Authority indicated with red circles

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Map of Ontario’s Hudson Bay and James Bay coastal region, with communities served by Weeneebayko Area Health Authority indicated with red circles

This is a map of the West coast of Ontario’s Hudson Bay which shows the communities which are served by the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority. The map shows approximately 500km of coastline with six communities highlighted. The most Northern community is Peawanuck about 40 km inland from the coast. In the middle of the coastline is Attawapiskat – opposite Akimiski Island and further south the communities of Kashechewan and Fort Albany very close to one another. At the Southern most tip of the map are the two neighbouring communities of Moosonee and Moose Factory.

In planning an intervention designed to address the particular challenges faced by remote northern communities, it was clear that an integral component of rabies prevention programs was a sustainable means of controlling dog population numbers. Initial estimates of a total dog population of about 1,330 in the WAHA region were generated by Health Canada nurses in each community in 2013, based on their observations and input from community members.

Prior to 2015, the six remote communities in the WAHA Project had varying access to only occasional surgical spay/neuter fly-in programs over the years which were delivered by various veterinary clinics and/or organizations. However, the lack of a consistent regional approach, with little or no information sharing between groups or individuals providing veterinary assistance to the region, poor survival rates of surgically spayed/neutered dogs within the communities and extreme costs associated with conducting animal surgeries in the region had resulted in limited success for controlling dog populations overall.

Surgical sterilization of free-roaming dogs in this region poses several significant challenges, many of which are insurmountable. Transportation of surgical and anaesthetic equipment to and within the region is logistically difficult and expensive and not all communities have facilities for an effective surgical spay/neuter clinic setup. The communities are only connected by ice roads which are open for two to three months over the winter, so movement between most communities is limited to air travel for most of the year. In addition, the northern climate poses its own challenges: shaved abdominal areas and recuperation from anaesthetic agents involved in spaying/neutering procedures result in high post-operative morbidity and mortality rates in free-roaming dogs at sub-zero temperatures in the winter and can be highly uncomfortable in the summer months due to mosquitoes and other biting insects.

Dogs With No Names’ previous experience on other First Nations communities in Alberta and Labrador had found that there is commonly a 2:1 ratio of males to females among free-roaming community dogs. This appears to occur for two reasons: decreased survival of pregnant and lactating females (due to higher energy requirements for survival) and active discrimination against ownership/care of female dogs due to challenges in dealing with litters and/or heat cycle problems. The average lifespan of female dogs in this setting is estimated to be only three years (Personal communication. Dr. Judith Samson-French, DVM, April 04, 2014).

Because of the limited number of available free-roaming female dogs, those that go into heat tend to create chaos in the community, with packs of male dogs trying to breed them all at once. This engenders aggression between dogs and redirected aggression toward people, posing a serious safety issue for communities.

As a result, the most (cost-)effective solution to both overpopulation and the aggressive pack behaviours associated with free-roaming dogs in northern communities is to prevent heat cycles in female dogs by sterilization (either surgical or using contraceptive implants). This prevents both problematic pack behaviours and breeding. Male dogs can also be sterilized to reduce population numbers, but targeting females is more practical and effective. Furthermore, a recent study examining the effect of both surgical and chemical sterilization on behaviours of free-roaming male dogs in Chile found that while surgical castration resulted in no reduction in aggression or sexual activity, chemical sterilization actually led to an increase in dog-directed aggression of male dogs and produced no change in sexual activity Footnote 1.

A number of studies have examined the measurement and control of dog populations in regions where canine rabies is endemic, such as India and the Philippines Footnote 2Footnote 3. Despite significant environmental differences likely to have an impact on canine population demographics in northern regions (e.g., the northern climate with harsh winters), an important lesson learned from previous studies in other parts of the world is the importance of understanding the population dynamics of dogs in a specific setting (including life expectancy at birth and early life mortality rates) to the effective management of free-ranging dogs Footnote 4. An understanding of dog population dynamics is clearly integral to both guiding the development of interventions in northern remote communities and assessing their effectiveness.

However, there is little in the way of published scientific information or guidelines about effective strategies available for a northern Ontario context, where large free-roaming dog populations are not themselves the rabies reservoir species, but pose a significant risk because they regularly come into contact with wildlife reservoir species in the region.

After extensive consultation and careful consideration, the WAHA Project was designed around five objectives:

- Humanely stabilizing dog populations on and around First Nations communities to manageable and sustainable levels;

- Reducing aggression in dogs and the resulting risk of injury to community members;

- Reducing the risk of rabies and other disease transmission from owned and/or free-roaming dogs to community members;

- Improving the overall health of community dogs; and

- Educating community members about the importance of dog control and the impacts on public health for the whole community.

Following the initial round of field operations in 2015, this article presents the initial WAHA Project findings with respect to the baseline dog population numbers and basic canine demographic information for the region and represents the first published information about northern Ontario dog populations in the Hudson and James Bay coastal region.

Intervention

The population control approach chosen for the WAHA Project involved the use of 9.4 mg Suprelorin® (deslorelin acetate), a non-surgical GnRH contraceptive implant. Brought in from Australia through Health Canada’s Emergency Drug Release program, the implant temporarily suppresses the female reproductive endocrine system and prevents production of pituitary and gonadal hormones for 12 to 18 months at a time. The effects of the implant are similar to those seen following a spay surgery, but are reversed after the deslorelin content of implant is depleted. However, given the expected short lifespan of most female free-roaming dogs in the north, the duration of the implant’s effectiveness would sterilize a female dog for most of its lifespan, particularly if administered for two years in a row.

As the WAHA communities are all remote, the influx of additional dogs from other regions is limited. Thus, use of injectable contraceptives for two consecutive years aims to stabilize and reduce dog populations by the third year of the program to the point where surgical sterilization interventions on older female dogs with proven survival rates are more effective due to fewer dogs requiring surgery.

The use of a non-surgical contraceptive implant in female dogs presents unique advantages including expediency, minimal handling of dogs, the potential for year-round use, marginal cost and no post-operative complications. The Suprelorin® implants used in the WAHA Project have been widely used as a contraceptive in many zoo and wildlife species and shown to be effective in reproductively active female dogs in the past Footnote 5.

In the weeks leading up to the arrival of the WAHA Project field team in each community in 2015, a public outreach and education campaign was launched, using direct mail to community members, posters in the community, Facebook postings and radio and television announcements. A two-pronged approach was used to gain access to dogs, beginning with community members bringing dogs to a centrally located “processing station”, followed by “door‑to‑door” and “street-by-street” mobile approaches for the remainder of the dogs in the community, with the team working out of a vehicle to capture free-roaming dogs. Written permission and informed consent for the handling of each dog was obtained from nearby house occupants for owned dogs and from the Chief and Council for unowned free-roaming dogs. Effectiveness of the public education campaigns year over year will be assessed by comparing the proportion of community residents willing to bring their dogs in to the centrally located “processing station” rather than requiring the Project field team to go door‑to‑door in 2016.

Each free-roaming dog encountered in the community was restrained safely and fed canned food containing a dewormer. A local anaesthetic (0.5 mL CarbocaineTM) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue between the dog’s shoulder blades, followed by administration of rabies and distemper, adenovirus-2, parvovirus and parainfluenza (DA2PP) vaccinations in the dog’s hindquarters, while the local anaesthetic was allowed to take effect. Following vaccination, a microchip was injected between the shoulder blades with a 14-gauge needle. If the dog was female, a Suprelorin® 9.4 mg contraceptive implant was also injected between the shoulder blades. Successful microchip insertion was confirmed with a microchip reader. The entire procedure from start to finish, once the dog was caught, required no more than five minutes per dog.

Full information on each dog handled by the Project team was entered into a microchip-based community dog registry. To assist with ease of visual identification of free-roaming community dogs already handled by the Project, all microchipped and vaccinated dogs had a highly visible rabies tag attached to a collar, which also allowed for estimation of the number of dogs in each community that were not handled in 2015.

The 2016, field operations will begin with scanning each dog presented or captured for a microchip to determine its identity, reproductive and vaccination status. Each dog previously handled in 2015 will be followed up again in 2016 and revaccinated for rabies with a three-year rabies vaccine which will significantly reduce the risk of rabies transmission in the region. Any new dogs in 2016, and those not already previously handled by the field team in 2015, will also be microchipped, vaccinated and (if female) implanted in the second year of the Project.

The reduction of the number of female dogs going through heat cycles (as a result of receiving a contraceptive implant) is expected to reduce the amount of aggressive pack behaviour in male dogs within the communities. The effectiveness of this strategy in reducing aggression and improving public safety will be assessed on the basis of reports generated by Nishnawbe-Aski Police Services (NAPS) for each of the First Nations communities, summarizing the number of dog-related calls (e.g., aggressive packs, dog attacks, dog fights, etc.) received by NAPS on an annual basis from 2014 to 2017.

Outcomes

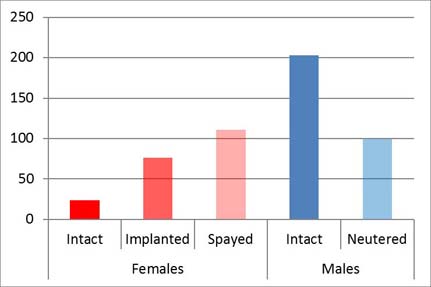

Of approximately 850 dogs determined to actually be in the region in June and July of 2015 by the field team, 513 (60%) were handled, microchipped and vaccinated, creating microchip-based dog registries for each of the communities. The results of the 2015 intervention for the region as a whole are shown in Figure 2 below. Of the 513 dogs handled, 211 (approximately 40%) were female, while 301 (approximately 60%) were male. Of the 211 females, 113 (54%) had been previously spayed and 98 (46%) were intact. Seventy-six (76%) of these intact females were given a contraceptive implant. The remaining 22 intact females were either too young (less than eight weeks old) or too small (e.g., toy breeds kept indoors permanently) to receive an implant. Most female dogs were under three years of age, while most males were under six years of age. All 513 dogs handled in 2015 were vaccinated against rabies and no cases of rabies were identified in any community dogs since 2013.

Figure 2: Number of dogs handled in Weeneebayko Area Health Authority communities, 2015

For each dog handled, a dog registry and medical record was created and linked to its microchip number, including information on breed type, gender, age, reproductive status, body condition score, approximate weight, any known history and vaccines/dewormers administered. All dog information collected was provided to each community in both electronic and hard copy format, with back-up copies of data stored by WAHA. Community dog density maps were also generated, indicating lot numbers and areas where dogs reside, to inform and facilitate both WAHA Project and community interventions in 2016 and beyond. Each community was also provided with a microchip reader, enabling them to scan, identify and determine the rabies vaccination status of all microchipped dogs whenever needed.

Discussion

The WAHA Project successfully reached 60% of the dog population in the Weeneebayko region in 2015. Rabies and (distemper, adenovirus-2, parvovirus and parainfluenza) DA2PP vaccines were administered to all dogs and almost 80% of intact female dogs received the injectable contraceptive with a 12-month duration.

Data collected by the WAHA Project in 2015 also found significant differences in dog populations between individual communities in the region, reflecting their degree of access to spay/neuter services prior to 2015. A majority of the dogs found to be previously sterilized (72% of spayed females and 51% of neutered males) were found in the southernmost communities, which have had greater access to spay/neuter clinics. These communities also tend to have higher numbers of small breed indoor dogs (e.g., Chihuahuas, Pomeranians, etc.) that do not contribute to the dog overpopulation and public safety issues. It is important to note, however, that communities which had some sterilized animals resulting from occasional access to spay/neuter services (provided only on an ad hoc basis and without coordination or longer-term planning), were not generally found to have fewer dog overpopulation issues than communities that had never had access to spay/neuter services. This appears to be due to a number of factors, including the fact that spay/neuter clinics generally do not proactively go out to systematically capture all free-roaming dogs, but rather depend on community members bringing dogs to a central location for surgery; and no prioritization of female spay surgeries over male neuters.

This perspective was further supported by one WAHA community which constitutes a notable exception in the region. This community had already implemented a consistent approach to unowned roaming dogs over three years, including repeated spay/neuter clinics targeting female dogs and the capture of dogs and removal of puppies from dens on the outskirts of the community for adoption out of the region. All female dogs in this community were found to be spayed and only a handful of males had not been neutered. Anecdotal information initially provided by local NAPS officers in this community indicated a significant decrease in dog-related calls to police, temporally associated with the successful sterilization of the majority of female dogs in the community.

The logistical challenges of conducting any dog population control project in any remote and isolated region are significant and require substantial resources to enable qualified personnel to travel to the region and ship all necessary equipment. The use of injectable contraceptives in female dogs as a population-stabilizing mechanism reduces the amount of veterinary equipment requiring shipping to a bare minimum, which is a definite strength of this approach. In addition, injectable contraceptives do not require veterinary follow-up in the same way that spay/neuter surgeries often do. In consulting with its communities prior to deciding on an approach for the WAHA Project, the Project team found that medical staff in most communities often reported concerns about the aftermath of spay/neuter clinics and community nursing stations are often asked to deal with veterinary post-operative complications such as surgical site infections in dogs, which they are neither equipped nor trained to treat. This, in turn, also contributes to the reluctance of some dog owners to have their dogs undergo surgery.

While the temporary nature of injectable contraceptives may be perceived as a weakness of this approach, the authors would argue that this is only true if all that is being considered is a single intervention, rather than a multi-year coordinated plan, as is the case with the WAHA Project. Administering implants to female dogs for two years in a row provides for infertility in the female dogs for up to three years, which currently covers most of the lifespan of intact female dogs in the region. Female dogs that survive more than three years in the north are better candidates for surgical spay interventions. Following the second year of contraceptive implant use in the region in 2016, next steps for the WAHA Project will include overall data analysis of dog population dynamics over the two years of the Project. The final data from the Project will inform the consideration of cost-effective options for a potential coordinated surgical spay/neuter plan and/or ongoing contraceptive implant use in female dogs in WAHA communities in the future.

The baseline 2015 findings of the WAHA Project support the feasibility of the use of contraceptive implants as an innovative primary intervention to prevent reproductive cycles in female dogs in remote northern regions where regular access to veterinary services is not available. Unless most female dogs in the community can be spayed at one time, ongoing reproduction in the background will ensure that there is a continual growth in population over the longer term, despite spay/neuter efforts. While final outcomes are still pending, data collected by the Project in 2015 has also indicated that unless the overall population is under control, spayed/neutered animals do not remain in the community for long. This, coupled with the time/cost limitations in making spay/neutering accessible in the region, extreme weather conditions, as well as lack of access to veterinary care to deal with post-operative complications such as surgical site infections all support the use of contraceptive implants as a better approach than surgical spay/neuter in the region as a primary intervention. Contraceptive use should later be followed by surgical spay/neuter approaches in a two to three-year timeframe, once background population growth has slowed considerably, or stopped.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Catherine Filejski of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care for providing ongoing leadership, consultation and support to the Project, as well as helpful comments on the manuscript and Dr. Judith Samson-French for her invaluable field team leadership and expertise in canine contraceptive implant use and administration.

Funding

Funding for the veterinary aspects of the WAHA Dog Population Management Pilot Project was generously provided by PetSmart Charities of Canada.

Conflict of interest

None.