Canadian travellers and migrants from Brazil

Download this article as a PDF (517 KB - 5 pages)

Download this article as a PDF (517 KB - 5 pages) Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 42-8: Current travel risks

Date published: August 4, 2016

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 42-8, August 4, 2016: Current travel risks

Rapid communication

Illness in Canadian travellers and migrants from Brazil: CanTravNet surveillance data, 2013–2016

Boggild AK1,2*, Geduld J3, Libman M4, Yansouni CP4, McCarthy AE5, Hajek J6, Ghesquiere W7, Vincelette J8, Kuhn S9, Plourde PJ10, Freedman DO11, Kain KC1,12

Affiliations

1 Tropical Disease Unit, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University Health Network and the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

2 Public Health Ontario Laboratories, Public Health Ontario, Toronto, ON

3 Office of Border and Travel Health, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

4 The JD MacLean Centre for Tropical Diseases, McGill University, Montréal, QC

5 Tropical Medicine and International Health Clinic, Division of Infectious Diseases, Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON

6 Division of Infectious Diseases, Vancouver General Hospital, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC

7 Infectious Diseases, Vancouver Island Health Authority, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Victoria, BC

8 Hôpital Saint-Luc du CHUM, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC

9 Section of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine, Alberta Children's Hospital and the University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

10 Travel Health and Tropical Medicine Services, Population and Public Health Program, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, Winnipeg, MB

11 Center for Geographic Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama

12 Sandra A. Rotman Centre for Global Health, Toronto, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Boggild AK, Geduld J, Libman M, Yansouni CP, McCarthy AE, Hajek J, et al. Illness in Canadian travellers and migrants from Brazil: CanTravNet surveillance data, 2013–2016. Can Comm Dis Rep 2016;42:153-7. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v42i08a01

Abstract

Background: In light of the 2016 summer Olympic games it is anticipated that Canadian practitioners will require information about common illnesses that may affect travellers returning from Brazil.

Objective: To identify the demographic and travel correlates of illness among recent Canadian travellers and migrants from Brazil attending a network of travel health clinics across Canada.

Methods: Data was analyzed on returned Canadian travellers and migrants presenting to a CanTravNet site for care of an illness between June 2013 and June 2016.

Results: During the study period, 7,707 ill travellers and migrants presented to a CanTravNet site and 89 (0.01%) acquired their illness in Brazil. Tourists were most well represented (n=45, 50.6%), followed by those travelling to "visit friends and relatives" (n=14, 15.7%). The median age was 37 years (range <1-78 years), 49 travellers were men (55.1%) and 40 were women (44.9%). Of the 40 women, 26 (65%) were of childbearing age. Nine percent (n=8) of travellers were diagnosed with arboviruses including dengue (n=6), chikungunya (n=1) and Zika virus (n=1), while another 14.6% (n=13) presented for care of non-specific viral syndrome (n=7), non-specific febrile illness (n=1), peripheral neuropathy (n=1) and non-specific rash (n=4), which are four syndromes that may be indicative of Zika virus infection. Ill returned travellers to Brazil were more likely to present for care of arboviral or Zika-like illness than other ill returned travellers to South America (23.6 per 100 travellers versus 10.5 per 100 travellers, respectively [p=0.0024]).

Interpretation: An epidemiologic approach to illness among returned Canadian travellers to Brazil can inform Canadian practitioners encountering both prospective and returned travellers to the Olympic games. Analysis showed that vector-borne illnesses such as dengue are common and even in this small group of travellers, both chikungunya and Zika virus were represented. It is extremely important to educate travellers about mosquito-avoidance measures in advance of travel to Brazil.

Introduction

During the past three years, Zika virus and chikungunya have emerged in the AmericasFootnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3 and dengue continues to be transmitted at high rates throughout the Caribbean, Central America and South AmericaFootnote 4. Brazil, in particular, has suffered severe health and economic consequences due to the emergence of these viruses in both urban and rural settingsFootnote 5. High rates of Zika virus in the Pernambuco state of Brazil heralded the recognition of a devastating new congenital neurologic syndromeFootnote 6.

In light of the ongoing Zika crisis, much attention has been directed at the 2016 Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro, set to begin in August. Debate around the risks to athletes, their entourages and to Canadians from infectious diseases among travellers returning to Canada, has been fierceFootnote 7Footnote 8. There is a lack of information about the health conditions associated with travel to Brazil for Canadians. In order to fill this knowledge gap, the authors conducted a Canada-specific traveller-level surveillance summary of illness among returned Canadian travellers and migrants to Brazil who presented for care at CanTravNet sites over a three-year period.

Methods

Data source: Seven Canadian sites that practice post-travel medicine in large urban centres from five provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec), belong to the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network and constitute a national surveillance group called CanTravNetFootnote 9. Demographic and travel-related data were collected using the data platform of the GeoSentinel Surveillance NetworkFootnote 10. The GeoSentinel data-collection protocol is reviewed cyclically by the institutional review board (IRB) officer at the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is classified as public health surveillance, not human-subjects research requiring submission to and approval from IRBs. Final diagnoses include specific etiologies (e.g., Zika virus) and syndromes (e.g., rash). All CanTravNet sites contribute microbiologically-confirmed data where available, based on the best available reference diagnostics.

Definitions and classifications: Seven travel purpose designations were used, including tourism, business, missionary/volunteer research/aid work, visiting friends and relatives (VFR), migration, education and planned medical careFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11.

Inclusion criteria: Demographic, clinical and travel-related data on Canadians encountered after completion of their travel to Brazil and seen in any of six CanTravNet sites from June 1, 2013 to June 1, 2016 were extracted and analyzed. Only patients with probable or confirmed final diagnoses were included.

Analysis: Extracted data were managed in a Microsoft Access database. Travellers were organized by purpose of travel, demographics and travel metrics including pre-travel encounter and diagnoses. Women of childbearing age were defined as those between 15 and 49 years of age. Differences between groups of travellers were compared using Fisher's exact test. All statistical computations were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

During the study period, 7,707 ill travellers and migrants presented to a CanTravNet site and of those, 89 (0.01%) acquired their illness in Brazil. Those travelling for tourism were the most well represented (n=45, 50.6%), followed by those travelling for VFR (n=14, 15.7%), business (n=13, 14.6%), migration (n=6, 6.7%), missionary/volunteer/aid work (n=6, 6.7%), education (n=3, 3.4%) or planned medical care (n=2, 2.2%). Median age was 37 years (range <1-78 years), 49 travellers were male (55.1%) and 40 were female (44.9%). Six travellers (6.7%) were under the age of 18 years. Top countries of birth were Canada (n=50, 56.2%) and Brazil (n=21, 23.6%). Median trip duration was 16 days (range 3-304 days). Almost one-third of travellers (n=28, 31.5%) had received a pre-travel consultation.

Almost 98% of ill returned travellers and migrants in this analysis were managed as outpatients (n=87). The most common presenting symptoms were dermatologic (n=43, 48.3%), followed by gastrointestinal (n=37, 41.6%) and fever (n=21, 23.6%). Cutaneous larva migrans (n=8, 9.0%), severe arthropod bites (n=8, 9.0%) and post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (n=10, 11.2%) were the most common dermatologic and gastrointestinal diagnoses respectively (Table 1). Presumably fecal-orally acquired illnesses such as typhoid fever, acute diarrhea, amoebiasis, giardiasis, campylobacteriosis and shigellosis occurred in 10% (n=9) of ill returned travellers. Respiratory illnesses, including influenza, influenza-like illness, lobar pneumonia and upper respiratory tract infections, occurred in 7.9% (n=7) of ill returned travellers.

| Diagnosis | All travellers n=89 |

Short-duration travellersTable 1 - Note 2 (trip duration ≤2 weeks) n=26 |

Mid-duration travellersTable 1 - Note 2 (trip duration 2-4 weeks) n=24 |

Long-duration travellersTable 1 - Note 2 (trip duration ≥1 month) n=24 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Systemic febrile illness | ||||||||

| Non-specific viral syndrome and mononucleosis-like illness | 7 | 7.9 | 2 | 7.7 | 4 | 16.7 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Dengue fever | 6 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12.5 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Influenza and influenza-like Illness | 4 | 4.5 | 3 | 11.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Enteric fever due to Salmonella typhi | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Lobar pneumonia | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chikungunya fever | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zika virus | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Zika-like syndromeTable 1 - Note 3 | 13 | 14.6 | 2 | 7.7 | 6 | 25.0 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Viral meningitis | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal illness | ||||||||

| Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome | 10 | 11.2 | 1 | 3.8 | 3 | 12.5 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Strongyloidiasis | 4 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Acute diarrhea | 3 | 3.4 | 2 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Chronic diarrhea | 2 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Amoebiasis due to Entamoeba histolytica | 2 | 2.2 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Giardiasis | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shigellosis | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Campylobacteriosis | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatologic illness | ||||||||

| Cutaneous larva migrans | 8 | 9.0 | 2 | 7.7 | 4 | 16.7 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Arthropod bite | 8 | 9.0 | 4 | 15.4 | 3 | 12.5 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Skin and soft-tissue infectionTable 1 - Note 4 | 6 | 6.7 | 2 | 7.7 | 1 | 4.2 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Rash, unknown etiology | 4 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8.3 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Animal BiteTable 1 - Note 5 | 2 | 2.2 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Cutaneous leishmaniasis | 2 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

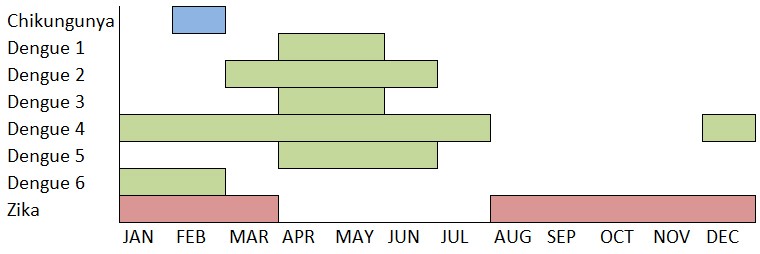

Febrile conditions including arboviral infections occurred in nine percent (n=8) of travellers, who were diagnosed with either dengue (n=6), chikungunya (n=1), or Zika virus (n=1). All eight travellers (100%) with chikunguyna, dengue or Zika had itineraries entailing travel to Brazil during the months of January to June, while only two of these eight travellers (25%) travelled to Brazil during the months of July to December (Figure 1). Non-specific viral syndrome (n=7), non-specific rash (n=4), non-specific febrile syndrome (n=1) and peripheral neuropathy (n=1), four syndromes possibly indicative of Zika virus infection, were also well represented (Table 1).

Figure 1: Eight cases of arboviral infection from Brazil by month of travel, CanTravNet 2013-2016.

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Eight cases of arboviral infection from Brazil by month of travel, CanTravNet 2013-2016.

Figure 1 is a chart showing eight cases of arboviral infections from Brazil. The Y-axis includes Chikungunya at the top, followed by Dengue fever numbered one through six, and Zika virus at the bottom. The X-axis shows the twelve months of the year, beginning with January and ending by December. Chikungunya is indicated by a blue colour, all of the numbered types of dengue are indicated by green, and Zika virus is indicated by red.

According to the chart, in the month of January, there were two cases of Dengue (Dengue 4 and Dengue 6) as well as one case of Zika virus.

In February, there was one case of chikungunya, two cases of Dengue (Dengue 4 and Dengue 6), and one case of Zika virus, making February the only month to include reports of all three arboviral infections.

In March, two cases of Dengue (Dengue 2 and Dengue 4) were reported, as well as one case of Zika.

For April and May, there were five Dengue cases (Dengue 1 through Dengue 5). The months of April and May had the highest total number of cases, but only with cases of Dengue. There were no reports of Zika or Chikungunya during this time.

In June, the number of Dengue cases fell to three (Dengue 2, 4 and 5).

From August to November, there were no cases of Dengue or Chikungunya reported. However, each of these months included one instance of Zika virus.

Finally, December included one case of Dengue 4, and one of Zika virus.

Note: Most cases of arboviral infection were acquired December to June rather than June to September, when the 2016 Olympics will be held.

Of 40 female travellers to Brazil, 26 (65%) were of childbearing age. Just over one-third of women of childbearing age had undergone pre-travel consultation (n=9, 34.6%). Rates of arboviral infection among women of childbearing age appeared to be similar to those in other travellers: 2/26 (7.7%) versus 6/63 (9.5%), respectively (p=1.00). Rates of non-specific rash, however, appeared to be greater in women of childbearing age than in other travellers: 3/26 (11.5%) versus 1/63 (1.6%), respectively, though this difference was not significant (p =0.07). Women of childbearing age appeared to be more likely to receive a diagnosis that could be compatible with a Zika-like illness, including peripheral neuropathy, viral syndrome, non-specific febrile syndrome and rash, compared to other travellers: 6/26 (23.1%) versus 7/63 (11.1%), respectively, though this difference was not significant (p=0.189).

Compared to other ill returned travellers and migrants to South America (n=401), those who acquired illness in Brazil were more likely to be diagnosed with dengue, chikungunya, or Zika: 8/89 (9.0%) versus 13/401 (3.2%) (p =0.0362) (Table 2). In addition, ill returned travellers to Brazil were more likely than other ill travellers to South America to acquire a Zika-like illness: 13/89 (14.6%) versus 29/401 (7.2%) (p =0.0347) (Table 2).

| Diagnosis or diagnostic bundle | Ill returned travellers and migrants from Brazil (n=89) | Ill returned travellers and migrants from other countries of South America (n=401) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Number per 100 travellers | n | Number per 100 travellers | ||

| A. Arboviral infection (Dengue, CHK or Zika virus)Table 2 - Note 1 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 3.2 | p=0.0362 |

| B. Zika-like illnessTable 2 - Note 2 | 13 | 14.6 | 29 | 7.2 | p=0.0347 |

| Total A + B | 21 | 23.6 | 42 | 10.5 | p=0.0024 |

Discussion

This analysis of surveillance data elucidates travel and demographic details for a subset of ill returned Canadian travellers and migrants who acquired their disease in Brazil this can inform Canadian practitioners encountering prospective and returned travellers to the 2016 Olympic games. These data highlight the recent and ongoing emergence of arboviral infections such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika in travellers to the Americas and the high rate of arthropod bite acquisition in travellers to Brazil.

Vector-borne viral disease occurred in 9% of ill travellers to Brazil and arthropod bites in another 10%

Vector-borne diseases, including dengue, chikungunya and Zika, were well represented among this group of ill travellers to Brazil and such illnesses appeared to have been associated predominantly with travel during the months of January to June, rather than the latter of half of the year during which time the Olympic games will be held. Compared to ill returned travellers and migrants to other countries of South America, those who travelled to Brazil were two- to three-times more likely to acquire arboviral or Zika-like illness. Due to a lack of vaccine availability or chemoprophylaxis at this time, prevention of arboviruses such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika rests on the use of mosquito avoidances measures such as screened accommodations, insecticide-treated clothing and DEET- or picaridin-based insect repellantsFootnote 12Footnote 13. Sexual transmission of Zika virus can be reduced through use of condoms and abstinenceFootnote 6Footnote 14.

Zika-like illness occurred in nearly 15% of ill travellers to Brazil

Phylogenetic studies have convincingly dated the introduction of Zika virus to Brazil in 2013Footnote 15, however, specific Zika virus diagnostic testing has only recently become availableFootnote 14. A full 15% of ill travellers to Brazil in this analysis received a diagnosis that could signal the presence of Zika virus, including non-specific viral or febrile syndrome, non-specific rash and peripheral neuropathy. Those presenting early in the study period prior to recognition of Zika transmission in the Americas would not have been tested for Zika virus. In addition, due to the prolonged turnaround time for Zika testingFootnote 14, many of those travellers with a recent Zika-like diagnosis may receive confirmatory Zika test results in the future. Of more concern is the finding of a Zika-like syndrome in almost one-quarter of women of childbearing age. Given the frequency and severity of the newly recognized congenital Zika syndromeFootnote 6Footnote 14, women who are pregnant are advised to avoid travel to the OlympicsFootnote 14Footnote 16 and those planning to conceive should consider deferring travelFootnote 14.

Limitations

Analysis of CanTravNet data has several limitationsFootnote 9. This analysis pertains only to the sample of ill returned travellers who presented to a CanTravNet site following travel to Brazil, thus, our conclusions may lack generalizability to other Canadian travellers and to those visiting other countries. The appearance of over-representation of arboviral and Zika-like illness among women of childbearing age may simply reflect referral bias following the emergence of Zika in the Americas. Our database may under-represent those who acquired short-duration illnesses on long-duration travel as these individuals may have convalesced while abroad and did not seek care upon return. Our data cannot estimate incidence rates or destination-specific numerical risks for particular diagnosesFootnote 17. As the Winnipeg site was new to CanTravNet in 2016, returning travellers to Manitoba are not represented. Data on pre-travel medical consultation was missing for 31.5% of ill returned travellers. Finally, due to the nature of our network, pediatric cases are under-represented, thus, our data may not be generalizable to the travelling pediatric population in Canada.

Conclusion

CanTravNet surveillance data can be used to better inform health professionals preparing prospective travellers to Brazil and the post-travel diagnostic approach to ill travellers and migrants returning to Canada from Brazil. These data underscore the emergent nature of both chikungunya and Zika in travellers to Brazil and reiterate that dengue continues to be a commonly travel-acquired arboviral infection in those with South American itineraries. The frequency of both arboviral infection and severe arthropod bites among this group of travellers to Brazil highlights the need for aggressive precautions against mosquito bites particularly during the daytime. Reinforcement of the range and type of mosquito avoidance measures available to travellers to Brazil should figure prominently into pre-travel discussions.

Contributions

AKB conceived the study, contributed to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and was primarily responsible for writing the manuscript. JG contributed to study conception, data interpretation, critical appraisal and revision of the manuscript. JV contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation, and to critical appraisal and revision of the manuscript. ML, CY, AEM, JH, WG, SK and KCK contributed to data collection and interpretation and to critical appraisal and revision of the manuscript. DOF and PJP contributed to data interpretation and critical appraisal and revision of the manuscript. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

CanTravNet is the Public Health Agency of Canada's corresponding network for tropical and travel medicine that has been funded through the Office of Border and Travel Health Division of PHAC. It has been created by grouping the Canadian sites of GeoSentinel: The Global Surveillance Network of the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) which is supported by Cooperative Agreement U50/CCU412347 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the ISTM. The funding source of GeoSentinel had no role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation or drafting the manuscript. The funding source of CanTravNet contributed to study design and critical appraisal of the manuscript, but did not have access to raw data.