Archived - HIV screening and testing in Canada—Part 2

Download this article as a PDF (337 KB - 5 pages)

Download this article as a PDF (337 KB - 5 pages) Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 43-12: Can we eliminate HIV?

Date published: December 7, 2017

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 43-12, December 7, 2017: Can we eliminate HIV?

Survey

Assessing uptake of national HIV screening and testing guidance—Part 2: Knowledge, comfort and practice

GP Traversy1, T Austin1, J Yau1, K Timmerman1

Affiliation

1 Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Traversy GP, Austin T, Yau J, Timmerman K. Assessing uptake of national HIV screening and testing guidance—Part 2: Knowledge, comfort and practice. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2017;43(12):267-71. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v43i12a04

Abstract

Background: The Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) HIV Screening and Testing Guide (the Guide) provides guidance to health care providers regarding who, when and how often to screen for HIV. HIV screening and testing is important in meeting the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS' (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 targets towards HIV elimination.

Objective: To determine health care providers' levels of knowledge about and comfort with aspects of HIV testing, and to determine whether their HIV testing practices are consistent with the recommendations in the Guide.

Methods: An open, anonymous online survey that included questions on knowledge, comfort and HIV testing practices was developed with stakeholders, validated and pre-tested. It was then disseminated to a convenience sample of health care providers across Canada between June and August 2016.

Results: A total of 1,075 participants representing all Canadian provinces and territories responded to the survey, with the majority being nurses (54%) and physicians (12%). Overall, knowledge related to HIV testing was substantial, but 37% of respondents underestimated the percentage of people living with HIV in Canada who are unaware of their HIV status and only 32% of respondents knew that HIV patients are frequently symptomatic during the acute infection. Most participants were comfortable with HIV testing and approximately 50% reported offering HIV testing regularly.

Conclusions: Although overall knowledge and practice were consistent with PHAC's HIV Screening and Testing Guide, some health care providers may underestimate the magnitude of undiagnosed HIV cases in Canada and may misinterpret the symptoms of acute HIV infection. While the amplitude of these results need to be interpreted in light of the convenience sample, addressing these knowledge gaps may facilitate earlier diagnosis of HIV among those who are unaware of their HIV status.

Introduction

With appropriate care and treatment, HIV can be a chronic but manageable condition; however, according to 2014 estimates, just over one in five people living with HIV in Canada are unaware of their infectionFootnote 1 Footnote 2. This means they are not receiving the care that they need and may be transmitting HIV to others.

HIV screening and testing practices are important, not only for ensuring that people living with HIV are linked to appropriate care and treatment but also for reaching the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 targets for HIV elimination by 2020. This includes having 90% of individuals living with HIV aware of their infection, 90% of people who are diagnosed on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90% of those who receive ART virally suppressedFootnote 3.

To complement existing efforts to support health care providers involved in HIV testing, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) released the HIV Screening and Testing Guide (the Guide) in 2013Footnote 1. The Guide is one of several products available to health care providers that provides evidence-based recommendations regarding who, when and how often to screen for HIV, as well as general information about testing and counselling procedures. Specifically, it recommends that health care providers discuss HIV testing as part of periodic routine medical care as a way to destigmatize and normalize testing and detect cases among the low risk population.

While some studies have been carried out in Canada to determine patterns of HIV testing practices by physicians and other health care providers, it is unclear the extent to which health care providers' clinical practices align with PHAC's screening recommendations and how comfortable they are with following these recommendationsFootnote 4 Footnote 5 Footnote 6. To date, PHAC has not conducted an evaluation of guidance uptake with respect to health care providers' knowledge of HIV testing recommendations in the Guide.

This article describes the results of Part 2 of a larger study assessing the uptake of the Guide. The objective of Part 1 was to evaluate the awareness, use and usefulness of the GuideFootnote 7. The objective of Part 2 was to assess health care providers' knowledge, comfort and clinical practices related to HIV testing. The overall study is part of the work underway to inform potential updates of the Guide to support HIV screening and testing practices in Canada.

Methods

Information related to health care providers' knowledge, comfort and clinical practices were collected over a three-month period (June–August 2016) as part of a larger, anonymous online survey. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys was followed where applicable for the reporting of methodology and resultsFootnote 8. The study was approved by the Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada Research Ethics Board.

Survey design

The survey was designed in consultation with evaluation, infectious disease and HIV content experts. The questions were developed based on previous PHAC surveys with similar objectives and from previous literature on survey designFootnote 6 Footnote 9 Footnote 10 Footnote 11 Footnote 12. The survey and study protocol were externally peer-reviewed for face validity by an infectious disease physician and an expert in evaluation. Pilot testing of the questionnaire was then conducted with a panel of infectious disease experts prior to full-scale dissemination.

Provider knowledge was assessed in two ways. First, participants had to answer eight true/false statements about HIV and HIV testing. Second, participants had to indicate who should be offered HIV testing among five patient groups: individuals requesting an HIV test; individuals presenting with symptoms and signs of a weakened immune system; individuals who are sexually active and have never been tested; individuals who share drug-using equipment with a partner who is or may be HIV-positive; and pregnant women, or those planning a pregnancy, and their partners.

Provider comfort with aspects of HIV testing was assessed using the open-ended question, "How comfortable are you in discussing HIV overall with your patients, including risk factors; pre- and post-test counselling; providing test results; and complying with reporting requirements?" Responses were coded on a 5-point scale (very comfortable, comfortable, somewhat comfortable, not very comfortable, and not at all comfortable) independently by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

To assess whether provider clinical practices were consistent with the Guide's recommendations, participants were asked to indicate to what percentage of patients they offer HIV tests as part of routine care and how often they discussed six topics (i.e., HIV testing, HIV test window period, privacy/confidentiality, methods for risk reduction, positive results' reporting requirements and referrals to HIV support services if test results are positive) when performing pre- and post-test counselling for HIV. Participants were also asked to indicate whether a number of statements on the routine offer of care or counselling apply to them. Further details on these variables, as well as the full survey, are available upon request.

Recruitment and administration

Participants were recruited through online newsletters/listservs, the Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange's (CATIE) website and email invitations distributed by contacts of other Government of Canada departments and regional offices. A link to the survey was also sent to 23 associations for health care providers (e.g., physicians, nurses, social workers and community-based service providers). While only three of the professional associations agreed to disseminate the survey (Pacific AIDS Network, Canadian Public Health Association and Canadian AIDS Society), others may have disseminated the survey to their members without informing the research team. Individuals who received the survey via e-mail or newsletter may have also further disseminated the survey among their colleagues and networks; therefore, a participation rate cannot be calculated.

The survey was hosted on the Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence Web Data online surveying tool and was available in English and French. Respondents were provided information related to privacy and data management/storage, length of the survey, purpose of the study and contact information for the principle investigator, prior to providing informed consent to participate. Moreover, all questions (other than the consent and screening questions) were voluntary. Participation was not incentivized. Participants' responses were included if they were 18 years of age or older, currently practicing and represented health care providers/professionals.

Data management and analysis

Survey responses were collected in a secure electronic database and then downloaded to a password-protected Microsoft Excel file. Responses were anonymous with no personal identifiers collected (e.g., names, addresses, email addresses or IP addresses). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the sample and responses to the survey questions. Analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel.

Results

A total of 1,075 health care providers from the 13 provinces/territories participated in the survey (Table 1). Respondents included in the survey were nurses (53.9%), physicians (11.9%) and community health workers (8.9%); however, other health care providers were included, such as nurse practitioners (7.8%), social workers (4.9%), counsellors (3.6%) and midwives (0.7%). Many of the respondents worked in the area of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and public health (43.1%); in large urban population centres (53.2%); and had more than 20 years of experience (38.3%).

| Demographics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Province/territory of practice (n=1,069) | ||

| Ontario | 375 | 35.1 |

| British Columbia | 152 | 14.2 |

| Quebec | 149 | 13.9 |

| Saskatchewan | 107 | 10 |

| Manitoba | 91 | 8.5 |

| Alberta | 79 | 7.4 |

| New Brunswick | 30 | 2.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 29 | 2.7 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 22 | 2.1 |

| Northwest Territories | 14 | 1.3 |

| Prince Edward Island | 11 | 1.1 |

| Yukon | 7 | 0.7 |

| Nunavut | 3 | 0.3 |

| Type of provider (n=1,071) | ||

| Nurse | 577 | 53.9 |

| Physician | 127 | 11.9 |

| Community health worker | 95 | 8.9 |

| Nurse practitioner | 84 | 7.8 |

| Social worker | 52 | 4.9 |

| Counsellor | 39 | 3.6 |

| Midwife | 8 | 0.7 |

| Medical resident | 0 | 0 |

| Other health care provider | 89 | 8.3 |

| Area of practice (n=1,055) | ||

| STI/Public Health | 455 | 43.1 |

| Family/General practice | 173 | 16.4 |

| Specialist | 114 | 10.8 |

| Emergency/Urgent care | 27 | 2.6 |

| Other (please specify) | 286 | 27.1 |

| Setting (n=1,061) | ||

| Large urban population centre (100,000+) | 564 | 53.2 |

| Medium population centre (between 30,000 and 99,999) | 181 | 17.1 |

| Small population centre (between 1,000 and 29,999) | 234 | 22.1 |

| Rural area (<1,000) | 62 | 5.8 |

| Geographically isolated/remote (not accessible by road or only by a dirt/winter road) | 20 | 1.9 |

| Years of practice (n=1,061) | ||

| > 20 years | 409 | 38.3 |

| 15 – 19 years | 141 | 13.2 |

| 10 – 14 years | 149 | 13.9 |

| 5 – 9 years | 177 | 16.6 |

| < 5 years | 193 | 18.1 |

Knowledge related to HIV testing

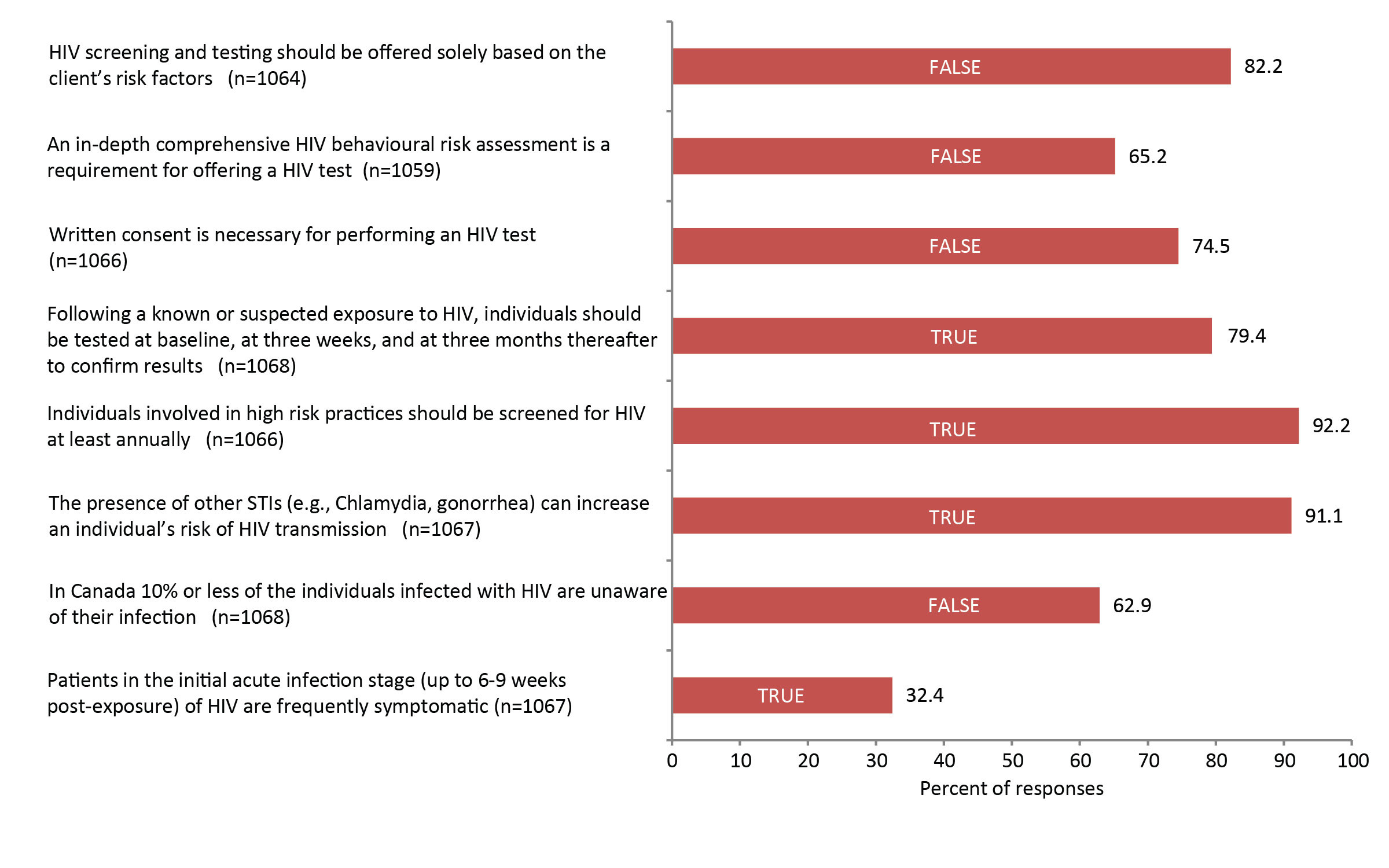

For the true/false questions, over 90% of participants knew that the presence of other sexually transmitted illnesses can increase an individual's risk of HIV transmission and that individuals involved in high risk practices should be screened for HIV at least annually (Figure 1). Approximately 75–80% knew that following a known exposure, baseline and follow-up testing was needed, that written consent was not needed for testing and that risk factors were not needed to provide a test. Only about one-third of respondents (32.4%) knew that patients are frequently symptomatic during acute infection and more than one-third of respondents (37.1%) estimated the rate of undiagnosed HIV in Canada was 10% or less when the actual rate of undiagnosed HIV is estimated at 21% Footnote 2. In the patient profile question, over 91% of respondents correctly indicated that all five patient groups listed should be offered an HIV test (data not shown).

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents who answered the true/false questions correctly (n= 1,059 - 1,068)

Abbreviations: n, number; STIs, sexually transmitted infections

Legend: The correct answer to each question is indicated on the bar chart

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

| Percentage of respondents (n=1059-1068) who answered true/false questions correctly | Number who answered correctly | Percent of responses | Answer to each question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients in the initial acute infection stage (up to 6-9 weeks post-exposure) of HIV are frequently symptomatic (n=1067) | 346 | 32.4 | True |

| In Canada 10% or less of the individuals infected with HIV are unaware of their infection (n=1068) | 672 | 62.9 | False |

| The presence of other STIs (e.g., Chlamydia, gonorrhea) can increase an individual's risk of HIV transmission (n=1067) | 973 | 91.1 | True |

| Individuals involved in high risk practices should be screened for HIV at least annually (n=1066) | 983 | 92.2 | True |

| Following a known or suspected exposure to HIV, individuals should be tested at baseline, at three weeks, and at three months thereafter to confirm results (n=1068) | 848 | 79.4 | True |

| Written consent is necessary for performing an HIV test (n=1066) | 794 | 74.5 | False |

| An in-depth comprehensive HIV behavioural risk assessment is a requirement for offering a HIV test (n=1059) | 691 | 65.2 | False |

| HIV screening and testing should be offered solely based on the client's risk factors (n=1064) | 875 | 82.2 | False |

Comfort with aspects of HIV testing

When asked how comfortable they were discussing HIV with their patients (including risk factors; pre and post-test counselling; providing test results; and complying with reporting requirements), a little over half (55.9%) of respondents indicated that they were very comfortable with the elements of HIV testing. Only 6.0% of the sample was either not very comfortable or not at all comfortable with HIV testing (Table 2).

| Level of comfort with discussing HIV with patients | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Very/extremely comfortable | 529 | 55.9 |

| Comfortable | 187 | 19.8 |

| Somewhat comfortable | 119 | 12.6 |

| Not very comfortable | 31 | 3.3 |

| Not at all comfortable | 24 | 2.5 |

| Not applicable | 57 | 6 |

|

Abbreviation: n, number Note: Level of comfort with discussing HIV with patients, including risk factors, pre- and post-test counselling, providing test results, and complying with reporting requirements |

||

Clinical practises related to HIV testing

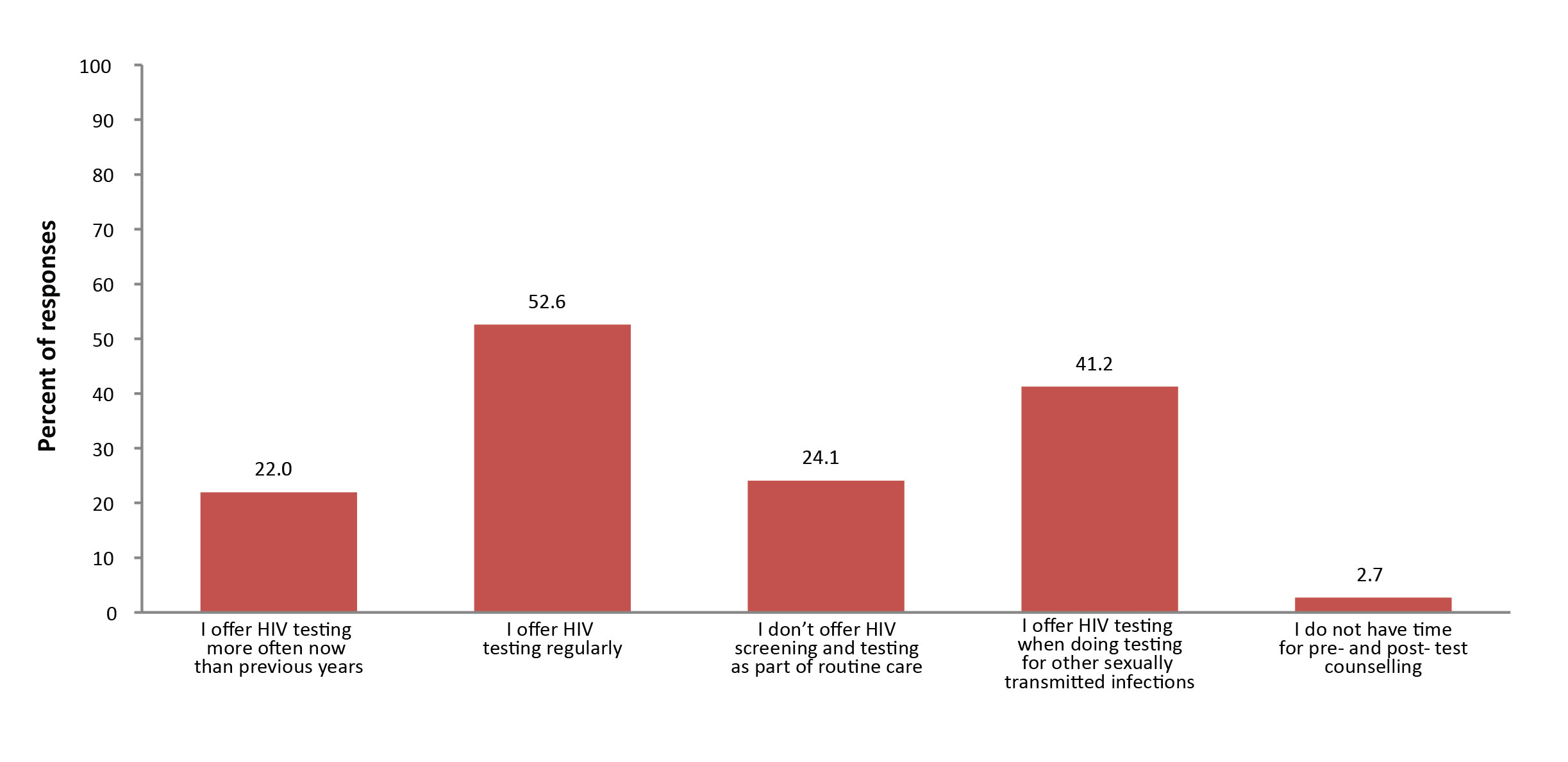

Over half of respondents (52.6%) reported offering HIV testing and 41.2% indicated that they offer HIV testing when testing for other STIs (Figure 2). In contrast, almost one-quarter of participants (24.1%) reported they offer routine testing to less than 25% or none of their patients.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents who indicated that the above statements apply to them (n=1,075)

Abbreviation: n, number

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

| Which of the following apply to you with respect to your HIV screening and testing activities? Please indicate all that apply | Number of respondents indicating a yes | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| I offer HIV testing more often now than in previous years | 236 | 22.0 |

| I offer HIV testing regularly | 565 | 52.6 |

| I don't offer HIV screening and testing as part of routine care | 259 | 24.1 |

| I offer HIV testing when doing testing for other sexually transmitted infections | 443 | 41.2 |

| I do not have time for pre- and post- test counselling | 29 | 2.7 |

When asked how often they offer HIV tests as part of routine care, 48.6% reported offering this 75-100% of the time (Table 3).

| To what percentage of patients do you offer HIV tests as part of routine care? (e.g., annual check-ups, physicals) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 75–100% | 302 | 48.6 |

| 50–75% | 100 | 16.1 |

| 25–50% | 57 | 9.2 |

| Less than 25% | 83 | 13.4 |

| I do not offer routine HIV testing to any of my patients | 79 | 12.7 |

|

Abbreviation: n, number |

||

Discussion

Overall, the results of this national survey suggest that health care providers have good knowledge about HIV testing and are comfortable with testing; however, there are a few knowledge gaps. The two gaps in knowledge—underestimating the percentage of people living with HIV who are unaware of their HIV status and lack of awareness that HIV patients are frequently symptomatic during acute infection—along with half of participants reporting they did not offer HIV screening and testing as part of routine care, may result in missed opportunities for early diagnosis of HIV. A lack of perceived risk has been previously identified as a key barrier to HIV testingFootnote 11.

The strengths of the current study include the geographically representative sample, with respondents from all provinces and territories, and the diverse range of health care providers. Moreover, the survey was comprehensive, covering a number of areas that could be used to update the Guide.

The limitations include the use of a convenience sample, which means the responses of the sample may not be representative of all health care providers in Canada who offer HIV testing. Some of our avenues of dissemination may have been more likely to target health care providers in the area of sexual health who would be more knowledge about and comfortable with HIV testing than other health care providers. In addition, the use of self-reported measures of clinical practice with respect to HIV testing practices could have introduced recall bias into the study.

Conclusion

HIV testing is the first step towards initiation of HIV treatment to improve the lives of people living with HIV and their sexual partners and reach the UNAIDS' 90-90-90 targets. The results of this survey could be used to inform future iterations of the Guide and other knowledge translation initiatives to improve provider awareness and comfort with testing as part of the overall effort to work towards HIV elimination in Canada.

Authors' statement

GT—conceptualization, methodology, data collection and curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration

TA—methodology, data collection and curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing

JY—methodology, data collection and curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing

KT—conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration

Conflict of interest

None.

Contributors

The authors would like to thank the following individuals, in no particular order, for their contribution to this manuscript:

Kelsey Young—formal analysis

Shalane Ha—methodology, writing—reviewing and editing

Jun Wu—methodology, writing—reviewing and editing, project administration

Margaret Gale-Rowe—methodology, writing—reviewing and editing, project administration

Makenzie Weekes—writing—reviewing and editing

Priya Prabhakar—writing—reviewing and editing

Militza Zencovich—methodology

Kanchana Amaratunga—methodology

Courtney Smith—formal analysis

Mandip Maheru—methodology

Ulrick Auguste—methodology

Katie Freer—methodology

Dena Schanzer—methodology, formal analysis

Mary Lysyk—methodology

Katherine Dinner—methodology

Simon Foley—conceptualization, methodology

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the input provided by the various contributors throughout the various stages of the project on the survey design, Research Ethics Board submissions, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Thank you to the team at the Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence for their help in setting up the survey tool, and to the Health Canada Research Ethics Board. The authors would also like to thank the Expert Working Group of the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections for the help with pilot testing the survey, and the various organizations that helped disseminate the survey.

Funding

The authors have no sources of external funding to declare. This research was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.