Community-based outbreak of Legionella pneumophila in Montréal Québec in 2019

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 46–7/8: Mandatory childhood immunization programs

Date published: July 2, 2020

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 46–7/8, July 2, 2020: Mandatory childhood immunization programs

Outbreak report

Mixed community and nosocomial outbreak of Legionella pneumophila in Montréal, Québec, 2019

Geneviève Cadieux1, Julie Brodeur1, Félix Lamothe1, Cindy Lalancette2, Pierre A Pilon1, David Kaiser1, Éric Litvak1

Affiliations

1 Direction régionale de santé publique de Montréal, Montréal, QC

2 Laboratoire de santé publique du Québec, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, QC

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Cadieux G, Brodeur J, Lamothe F, Lalancette C, Pilon PA, Kaiser D, Litvak E. Mixed community and nosocomial outbreak of Legionella pneumophila in Montréal, Québec, 2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2020;46(7/8):219–26. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v46i78a01

Keywords: Legionella, Legionella pneumophila, Legionellosis, Legionnaires’ disease, disease outbreaks, communicable disease control, public health, water microbiology, water quality

Abstract

Objectives: To describe the investigation of a community-based outbreak of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, with retirement home and acute care hospital sub-clusters in Montréal, QC, and the key challenges encountered.

Methods: There were 14 cases of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 infection with an onset date between June 7 and August 21, 2019. The environmental investigation included sampling of water cooling towers (WCTs) and other potential sources. Sequence-based typing of clinical and environmental isolates was performed. Public health interventions included WCT decontamination orders and communication with clinicians.

Results: Eleven (79%) of the 14 cases were immunosuppressed or immunocompromised. Most (13; 93%) were diagnosed using a urinary antigen test, and five (36%) had a culture. Two sub-clusters were identified: three cases in a retirement home and four cases on an acute care hospital floor. Typing results suggested that the same L. pneumophila serogroup 1 may have caused the community outbreak and the two sub-clusters. A matching environmental source was not identified.

Conclusion: Whereas typing of clinical isolates suggested a common environmental source, our investigation failed to identify this source. Future outbreak investigations could benefit from more clinical isolates for typing, local registries of water aerosolization sources other than WCTs, and ongoing access to all WCT routine monitoring results and L. pneumophila isolates for typing.

Introduction

Legionella sp. infection became reportable in the province of Québec (QC) in 1987. Legionellosis incidence has been increasing since 2006Footnote 1. In 2012, a Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 outbreak in Québec linked to a water cooling tower (WCT) resulted in 183 cases and 13 deathsFootnote 1Footnote 2. Following this outbreak, the province introduced regulation that requires all WCTs to be registered with the Régie du bâtiment du Québec (RBQ)Footnote 3 and undergo routine maintenance and monthly monitoring for L. pneumophilaFootnote 1. WCT sampling must be performed according to provincial guidelinesFootnote 4, and results must be submitted monthly to the RBQ. The regulation requires WCT owners to take mitigation actions when results are between 10,000 and 999,999 colony-forming units (CFU)/L.

Furthermore, since July 2014, routine L. pneumophila monitoring results of 1,000,000 CFU/L or more must be reported to public health, and the reporting laboratory must keep the isolate for three months to facilitate public health investigation. The regulation also enables public health to issue decontamination orders to WCT ownersFootnote 1Footnote 5. Preliminary data on a sample of over 300 WCTs suggest that the concentration of L. pneumophila in WCTs has decreased since the regulation was introduced in 2014Footnote 6.

However, although the number of legionellosis cases reported annually ranged from 11 to 19 between 2007 and 2014, the number increased thereafter, to 63 in 2018 and 55 in 2019. In 2018, three spatiotemporal clusters were identified, the largest involving nine cases. Despite extensive investigations, the source of these clusters was never identified. That year, 83 occurrences of L. pneumophila at levels of 1,000,000 CFU/L or more involving 70 WCTs were reported to the Montréal public health department (Direction régionale de santé publique de Montréal, or DRSP), of a total of approximately 1,300 registered WCTs in Montréal. Since routine monitoring of WCTs was implemented in 2014, neither a cluster nor a sporadic case of legionellosis has been successfully matched to a WCT in Montréal.

The objective of this report is to describe the investigation of a mixed community and nosocomial outbreak of legionellosis, in spring/summer 2019, in Montréal. Some of the 14 people infected included patients on an acute care hospital ward for immunocompromised and immunosuppressed patients with very limited outdoor exposure. The report highlights the continuing challenges public health faces in identifying and controlling sources of Legionella outbreaks in large, densely populated urban areas where there are multiple possible sources of Legionella, in spite of a provincial WCT registry and legally mandated monthly routine monitoring for L. pneumophila.

Methods

Spatiotemporal cluster detection

A spatiotemporal cluster of three community-acquired cases of legionellosis reported within a period of 27 days was first detected on July 10, 2019, through SaTScan routine daily automated spatiotemporal cluster analysis of local reportable disease data. Manual review of this cluster identified a fourth case reported within a 28-day window; all four cases were infected with L. pneumophila serogroup 1.

Case investigation

The provincial legionellosis case definition requires the presence of a compatible clinical presentation and laboratory confirmation of infection from an appropriate clinical specimen (typically a urinary antigen test or sputum culture)Footnote 3. All cases reported to the DRSP are investigated using a standard provincial questionnaireFootnote 3; data are collected on risk factors (including diabetes, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, disease or drug-related compromised immunity, cancer, chemotherapy or radiation in the last six months, smoking, alcohol use); clinical presentation; diagnostic test results; complications; and potential exposures during the incubation period (including travel, health care, spa/pool, decorative fountains, drinking water fountains, grocery stores, greenhouses, water parks, drinking water supply issues, issues with plumbing, equipment that produce aerosols, water heater temperature, dental treatments, occupational and potential workplace exposures). For cases associated with a spatiotemporal cluster or outbreak, detailed information is collected on all sites visited during the incubation periodFootnote 3. Public health investigators routinely ask treating physicians to consider also ordering a sputum culture for Legionella for cases with a positive urinary antigen test.

A confirmed outbreak case was defined as one that met the provincial legionellosis case definitionFootnote 3; had a culture positive for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 with a sequence type consistent with the other outbreak cases; and had resided or worked within 3 km of the cluster’s epicentre during their incubation period. A probable outbreak case met the provincial case definition for legionellosisFootnote 3; had only a positive urinary L. pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen test; and had resided or worked within 3 km of the cluster’s epicentre during their incubation period. The usual incubation period of 2–10 days was extended up to 21 days for immunocompromised and immunosuppressed patients; the incubation period for the first four cases that launched the cluster investigation was May 24 to June 28, 2019.

During the case investigation, two sub-clusters were identified: three cases in a retirement home and four nosocomial cases in an acute care hospital. The residents of the retirement home lived on different floors and in different towers. The nosocomial cases had been hospitalized on the same floor for the entire incubation period (more than 21 days).

Environmental investigation

The WCT with L. pneumophila serogroup 1 levels of 1,000,000 CFU/L or higher nearest to the epicenter during the incubation period was about 8 km away, so it was more likely that a closer WCT with a lower L. pneumophila concentration could be the source. The approximate geographic centre of the four cases was identified, and a 4 km radius was drawn around the centre (as a precaution, 1 km was added to the 3 km radius recommended by provincial guidance)Footnote 3. Wind speed and direction during the incubation period was also analyzed. On July 11, DRSP requested monthly L. pneumophila testing results from May through July for all 59 WCTs (38 sites) within this zone from RBQFootnote 3. Manual review of these results identified two WCTs with L. pneumophila serogroup 1 concentration below 1,000,000 CFU/L, 16 with missing results and none showing “interfering flora” (which could hide L. pneumophila).

After a fifth case of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 within the same geographic area was reported on July 12, DRSP issued a public health order to the RBQ to obtain water samples for retesting of the 18 WCTs with abnormal or missing results. The RBQ follows the provincial guideline for WCT samplingFootnote 4; the sampling procedure is the same for routine monthly monitoring as for outbreaks: a single 1 L water sample is obtained from a representative site after letting the water run for at least 30 seconds to purge stagnant water.

As more cluster cases were reported, the epicentre and the 4 km radius zone around it were adjusted slightly. DRSP requested the RBQ updated results of routine L. pneumophila monitoring for all WCTs located within the zone from on July 19 and 31 and August 12. On August 26, because a source had not yet been identified, DRSP requested that all available isolates from WCTs located within 12 km of the epicentre and with monthly Legionella monitoring results of 1,000,000 CFU/L or more at any time during the cases’ incubation period be sent to the laboratory for sequence-based typing.

Concurrently, based on provincial guidanceFootnote 3 and the scientific literatureFootnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11, DRSP accessed available databases of built water features and construction sites impeding road circulation as well as satellite images to identify other potential sources of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 aerosolization within a 2 km radius of the epicentre. During a field visit on August 7, water and/or biofilm specimens were collected from a high-pressure paint-stripping device and a water hose used for compacting the ground at a nearby excavation site. Water samples from a golf course irrigation system (i.e. sprinklers in three separate areas closest to the cases) were obtained on August 15.

Separate environmental investigations were also performed for the two sub-clusters of cases at the retirement home and acute care hospital. DRSP reviewed the heated pool and spa maintenance logs and hot water reservoir temperatures at the retirement home. Water samples from the hot water reservoir, heated pool, spa and outdoor decorative fountain and drinking water from the separate apartments of two residents who had become infected were collected on July 25.

The acute care hospital infection prevention and control team investigated potential sources on the affected floor. Water/biofilm samples were collected from sinks, taps and showerheads on July 24 and August 13 and from an ice machine, refrigerator, floor-cleaning machine and outdoor garden hose on August 13.

Laboratory analyses of clinical and environmental specimens

The diagnosing hospital performed the initial analysis of clinical specimens; these specimens or isolates were then forwarded to the provincial public health laboratory for confirmation and typing. On clinical specimens, routine confirmation methods included a locally-developed real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting ssrA, mip and wzm genes; on clinical isolates, confirmation was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-ToF, Bruker, IVD 3,2) and serogroup 1 was identified by agglutination test slide with L. pneumophila serogroup 1 antisera (Denka Seiket, Japan). Genotyping was performed by sequence-based typing according to the European Working Group for Legionella Infection (EWGLI) protocolFootnote 12Footnote 13.

The Centre d’expertise en analyses environnementales du Québec (CEAEQ) conducted the culture and quantitative real-time PCR (L. pneumophila serogroup 1) analyses of WCT water samples obtained following the public health order. Analyses of environmental samples other than WCTs were performed by different commercial laboratories accredited by the CSA Group (L. pneumophila qPCR) and the CEAEQ (Legionella culture). All L. pneumophila serogroup 1 environmental isolates were forwarded to the provincial public health laboratory for typing.

Interventions

As a precaution, a decontamination order, effective immediately, was issued to all owners/managers of the WCTs that tested positive for L. pneumophila (any quantifiable result). The environmental health team from the DRSP followed up with each WCT owner/manager to make sure that decontamination was completed as soon as possible. Decontamination effectiveness was verified through repeat WCT sampling 2 to 7 days later, as per the provincial protocolFootnote 4. A public health alert was sent to Montréal clinicians to remind them to test for legionellosis in at-risk patients presenting with pneumonia and to order a sputum culture for Legionella to facilitate public health investigation. The outbreak was declared over on October 18, 45 days after the last case was reported to public health.

Results

Epidemiologic investigation

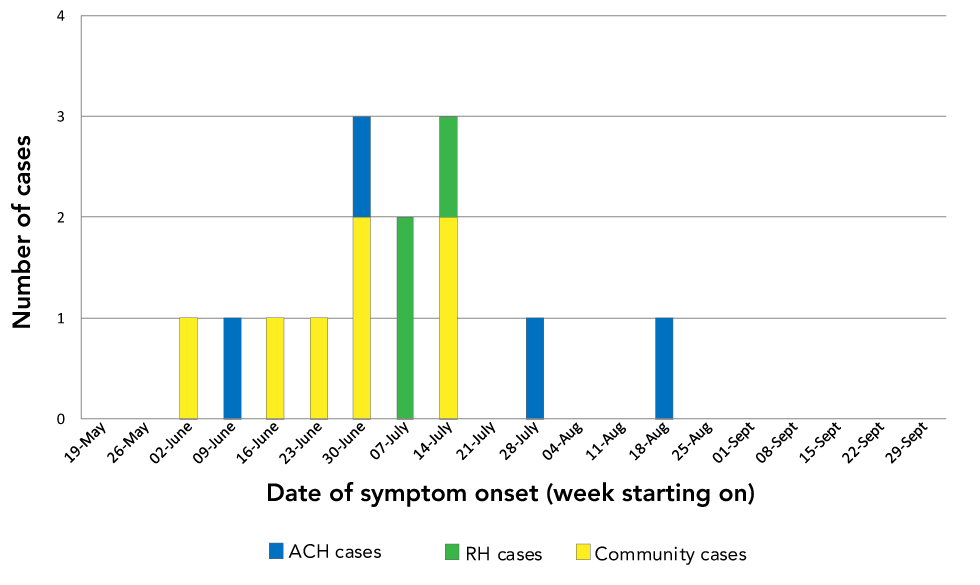

The outbreak comprised 14 cases of L. pneumophila serogroup 1, with illness onset between June 7 and August 21, 2019 (Figure 1 and Table 1). Among the 14 cases, ten were male, median age was 68 years, 11 were immunosuppressed or immunocompromised, four required admission to an intensive care unit, two were intubated and one died. Six cases lived in private homes and three in the same retirement home (in different towers and on different floors); four were hospitalized on the same hospital floor for the duration of their incubation period and one lived in an independent living facility for persons undergoing cancer treatment near the acute care hospital.

Figure 1: Epidemic curve for the legionellosis outbreak in Montréal, 2019

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Epidemic curve for the legionellosis outbreak in Montréal, 2019

| Week | Community cases | ACH cases | RH cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-05-19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-05-26 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-06-02 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-06-09 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2019-06-16 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-06-23 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-06-30 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 2019-07-07 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2019-07-14 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2019-07-21 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-07-28 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2019-08-04 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-08-11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-08-18 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2019-08-25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-09-01 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-09-08 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-09-15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-09-22 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019-09-29 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case ID | Date reported | Date of illness onset | Sex | Age group (years) | Risk factors | Urinary antigen test | Sputum/BAL culture | Complications | Exposure setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2019-06-13 | 2019-06-07 | F | 85–89 | Chronic lung disease; immunosuppression; cancer; cigarette smoking | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Private home |

| 2 | 2019-07-03 | 2019-06-26 | M | 25–29 | Immunosuppression; cancer | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Private home |

| 3 | 2019-07-05 | 2019-06-30 | M | 65–69 | Diabetes; chronic renal disease; cigarette smoking; alcohol consumption above lower-risk drinking guidelines | Positive | Positive | Hospitalized; ICU stay; intubated | Private home |

| 4 | 2019-07-09 | 2019-06-18 | M | 65–69 | Diabetes; immunosuppression; chronic renal disease; cigarette smoking | Positive | ND | Hospitalized; ICU stay | Private home |

| 5 | 2019-07-12 | 2019-07-10 | F | 75–79 | Diabetes; cardiovascular disease; chronic renal disease; immunosuppression; cancer; alcohol consumption above lower-risk drinking guidelines | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Retirement home |

| 6 | 2019-07-15 | 2019-07-02 | F | 30–34 | Immunosuppression; cigarette smoking | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Private home |

| 7 | 2019-07-19 | 2019-07-14 | F | 80–84 | Cardiovascular disease; chronic renal disease | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Private home |

| 8 | 2019-07-19 | 2019-07-10 | M | 75–79 | Diabetes; cardiovascular disease; cigarette smoking | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Retirement home |

| 9Footnote a of Table 1 | 2019-07-22 | 2019-07-01 | M | 55–59 | Immunosuppression; cigarette smoking | Positive | Positive | Hospitalized | Acute care hospital |

| 10 | 2019-07-22 | 2019-07-15 | M | 60–64 | Diabetes; cardiovascular disease; chronic renal disease; immunosuppression | ND (anuric) | Positive | Hospitalized; ICU stay; intubated | Acute care hospital |

| 11 | 2019-07-22 | 2019-07-20 | M | 60–64 | Immunosuppression; cancer | Positive | Positive | Hospitalized; ICU stay; death | Cancer care home |

| 12 | 2019-07-24 | 2019-07-16 | M | 70–74 | Diabetes; cardiovascular disease; immunosuppression; cigarette smoking | Positive | Positive | Hospitalized | Retirement home |

| 13 | 2019-08-12 | 2019-08-03 | M | 75–79 | Diabetes; chronic lung disease; cardiovascular disease; immunosuppression; cigarette smoking | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Acute care hospital |

| 14 | 2019-09-03 | 2019-08-21 | M | 50–54 | Immunosuppression | Positive | ND | Hospitalized | Acute care hospital |

Thirteen cases were initially diagnosed through a positive urinary antigen test; positive sputum cultures were subsequently obtained for four of them (Table 1). One anuric patient was initially diagnosed through a sputum culture.

At 63.8 years (standard deviation: 17.6; median: 68 years), outbreak cases tended to be younger than other 2019 Montréal cases of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 infection whose mean age was 69.1 years (standard deviation: 11.7; median: 65 years). A larger proportion had comorbidities including compromised immunity or immunosuppression (see Table 2). A detailed review of findings from case investigations did not identify any common exposures between cases other than place of residence.

| Characteristics | Cases linked to this outbreak (N=14) |

Other cases in Montréal in 2019 (N=41) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 25–34 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| 35–44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 45–54 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

| 55–64 | 3 | 21 | 16 | 39 |

| 65–74 | 3 | 21 | 10 | 24 |

| 75–84 | 4 | 29 | 5 | 12 |

| Older than or 85 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 17 |

| Comorbidities (self-reported) | ||||

| Diabetes | 7 | 50 | 12 | 29 |

| Chronic lung disease | 3 | 21 | 6 | 15 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 | 43 | 21 | 51 |

| Chronic renal disease | 5 | 36 | 5 | 12 |

| Immunosuppression | 11 | 79 | 6 | 15 |

| Other risk factors (self-reported) | ||||

| Smoking | 8 | 57 | 27 | 66 |

| Alcohol consumption above low-risk drinking guidelinesFootnote a of Table 2 | 2 | 14 | 8 | 20 |

| Diagnostic test | ||||

| Positive urinary antigen test | 13 | 93 | 40 | 98 |

| Positive sputum or BAL culture | 5 | 36 | 5 | 12 |

| Severity | ||||

| Hospitalization | 14 | 100 | 41 | 100 |

| ICU admission | 4 | 29 | 11 | 27 |

| Intubation | 2 | 14 | 6 | 15 |

| Death | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

Environmental investigation

A total of 18 WCTs with abnormal or missing monthly monitoring results were initially sampled by order of the DRSP on July 13–18. Samples were first analyzed for L. pneumophila by qPCR, and if positive, by culture (Table 3). A positive quantifiable culture result was only obtained for one WCT (WCT-A). Review of updated monthly monitoring results on August 12 identified three WCTs with abnormal culture results in July; the isolates from two WCTs were still available (WCT-B and WCT-C), but the third had already been discarded. A resampling order was issued, but the sample tested negative. Twelve other WCTs located 4 to 12 km from the epicentre had routine L. pneumophila monitoring results of 1,000,000 CFU/L or more during the combined incubation period of our cases. The provincial public health laboratory conducted typing of all 15 quantifiable L. pneumophila serogroup 1 culture isolates.

| WCT | Distance to epicentre (km) | Legionella culture result (CFU/L)Footnote a of Table 3 | Sequence-based typing results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flaA | flaA | flaA | flaA | flaA | flaA | flaA | |||

| A | 1.2 | 10,000 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B | 1.5 | 10,000 | NA | 14 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 2 |

| C | 3.5 | 2,000,000 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA |

| D | 7.1 | 2,000,000 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| E | 7.3 | 1,000,000 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 13 | 9 |

| F | 7.8 | 2,100,000 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA |

| G | 7.9 | 3,900,000 | 1 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | NA |

| H | 8.1 | 3,880,000 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 13 | 9 |

| I | 8.3 | 6,600,000 | NAFootnote b of Table 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| J | 8.5 | 2,000,000 | NAFootnote c of Table 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| K | 8.8 | 7,400,000 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L | 9.7 | 5,600,000 | NAFootnote d of Table 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| M | 9.7 | 2,000,000 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 13 | 9 |

| N | 10.3 | 1,000,000 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| O | 11.5 | 4,880,000 | NAFootnote e of Table 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Samples from all other potential outdoor community sources tested negative for L. pneumophila by qPCR. Samples from the retirement home (hot water reservoir, heated pool, spa, outdoor decorative fountain and drinking water) were all negative for L. pneumophila by qPCR. All hospital samples taken on July 24 (15 samples) and August 13–14 (19 samples) either tested negative (25 samples) or had L. pneumophila levels below the limit of quantification (9 samples) by qPCR.

Sequence-based typing of clinical and environmental specimens

In total, five clinical isolates were available for typing (Table 4); all sequenced alleles matched, suggesting a common source. Four cases had six or seven sequenced alleles, and all sequenced alleles matched each other; two cases from the acute care hospital, one from the retirement home, the other from the community. Only two alleles from the cancer care home case could be sequenced; both matched all other cases. The sequence type for the only fully typed case (Table 4, Case ID 12) was a new type, ST2858, in the EWGLI database. Typing results from the WCTs were not a match to the clinical isolates (Table 3).

| Case ID | Exposure setting | Sequence-based typing results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flaA | pilE | asd | mip | mompS | proA | neuA | ||

| 3 | Private home | NA | 9 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 15 |

| 10 | Acute care hospital | NA | 9 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 15 |

| 9 | Acute care hospital (same floor) | 12 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 20 | NA |

| 11 | Cancer care home | 12 | NA | NA | NA | 3 | NA | NA |

| 12 | Retirement home | 12 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 15 |

Discussion

We investigated a spatiotemporal cluster of 14 L. pneumophila serogroup 1 cases reported over a 12-week period from June to August 2019, in Montréal. The outbreak was initially detected through routine daily automated geospatial cluster analysis of reportable disease data. Our epidemiologic investigation identified that outbreak cases tended to be younger, have more comorbidities including compromised immunity or suppression, as compared to non-outbreak cases. No common exposure was identified other than place of residence. Two sub-clusters were identified: three cases resided in the same retirement home and four had been hospitalized on the same acute care hospital floor for their entire incubation period. Typing was performed for five cases; results suggested a common source for all cases. The outbreak was declared over in mid-October, but an environmental source was never identified.

The outbreak investigation benefited from access to monthly L. pneumophila monitoring results for all WCTs in the provincial registry and rapid sampling WCT sampling and decontamination (through public health orders). Whereas the outbreak was eventually controlled, our extensive environmental investigations did not identify a source. One potential explanation is that a WCT may harbour multiple L. pneumophila serogroups concurrentlyFootnote 15Footnote 16 that may change rapidly over timeFootnote 11 (e.g. between the case’s exposure and the sampling of the WCT).

It is not uncommon to fail to identify the source of a L. pneumophila outbreak. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) did not find a source for 11 of 17 L. pneumophila serogroup 1 outbreaks associated with environmental or undetermined exposures to water in 2013–2014Footnote 17. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the source was identified in less than 50% of Legionella outbreaksFootnote 18Footnote 19. Recent research suggests that sequence-based typing is insufficient to discriminate between some L. pneumophila serogroup 1Footnote 15Footnote 20; therefore, it is possible that our outbreak cases were not infected with the same L. pneumophila serogroup 1; however, this issue has not been reported for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 ST2858.

There were several key challenges in attempting to identify the source of this outbreak. Clinical isolates (i.e. sputum cultures) were available for only a quarter of all cases, thereby limiting our ability to assess which were linked to the outbreak and muddying the search for a common source. The unavailability of environmental isolates from WCTs with L. pneumophila monitoring results below 1,000,000 CFU/L, because laboratories are not legally mandated to retain them, also hampered our investigation. Those WCTs had to be resampled, often a few weeks after the initial positive result, sometimes after corrective action, thereby decreasing the probability of re-isolating the same L. pneumophila that had been present during the cases’ incubation period. There is evidence of Legionella outbreaks associated with WCT concentrations of L. pneumophila below 1,000,000 CFU/L: a systematic review of all Legionella outbreaks attributed to WCTs in 2001–2012 found Legionella concentrations below 1,000,000 CFU/L in 4/19 outbreaksFootnote 21. A 2017 legionellosis outbreak in the Mauricie-et-Centre-du-Québec health region was genetically linked to a WCT that showed “interfering flora” on routine Legionella monitoring and had a Legionella concentration of 630,000 CFU/L on resamplingFootnote 1. Given that 11 of the 14 patients in our outbreak were immunocompromised or immunosuppressed, it is possible that the source was a WCT with L. pneumophila serogroup 1 levels below 1,000,000 CFU/L.

Another important challenge was the lack of comprehensive databases on potential sources of water aerosolization other than WCTs, for example, decorative water features on public and private properties, public and private construction sites and large-scale irrigation systems. As a result, we could have overlooked a potential source. Also, whereas the RBQ estimates that nearly all WCTs in QC are registered, WCTs on federal buildings are monitored for L. pneumophila by a federal agency and results are not reported to the RBQ.

Finally, the provincial sampling protocol involves collecting a single 1 L water sample per WCT, under both routine and outbreak conditions. In contrast, the CDC recommends obtaining five 1 L water samples and three biofilm swabs (from specific areas) per WCT as part of an outbreak investigationFootnote 22. Following the CDC’s WCT sampling protocol would have likely increased the probability of detecting L. pneumophila serogroup 1 in sampled WCTs, thereby increasing the probability of identifying the source of our outbreak.

Conclusion

This report describes a community-based outbreak of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 with retirement home and acute care hospital sub-clusters. Whereas typing of clinical isolates suggested a common environmental source, our investigation failed to identify it. Future outbreak investigations could benefit from the availability of more clinical isolates for typing, perhaps adding NAAT to culture (e.g. when antibiotics have already been started); local registries of water features other than WCTs (e.g. fountains) that could potentially aerosolize L. pneumophila; ongoing access to all routine WCT monitoring results, rather than public health only being notified of results above a threshold; and access to all recent L. pneumophila isolates obtained through routine WCT monitoring (regardless of concentration) for typing. Research is needed to update and summarize L. pneumophila environmental sources that have been linked to cases or outbreaks, as well as to identify L. pneumophila thresholds for action that account for the possibility that immunocompromised or immunosuppressed persons may be infected by lower concentrations of bacteria.

Authors’ statement

- GC co-led the epidemiologic investigation and is the primary author of the manuscript

- JB and FL led the environmental investigation, contributed to writing the sections on the environmental investigation and provided feedback on the manuscript

- CL oversaw the analyses conducted at the provincial public health laboratory and provided feedback on the manuscript

- PAP co-led the epidemiologic investigation and provided feedback on the manuscript

- DK oversaw the environmental investigation and provided feedback on the manuscript

- EL oversaw the epidemiologic investigation and provided feedback on the manuscript

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the teams at the Direction régionale de santé publique de Montréal’s Prévention et contrôle des maladies infectieuses (PCMI) and Environnement urbain et saines habitudes de vie (EUSHV), and Activités courantes et vigie sanitaire (ACVS) who contributed to this outbreak investigation. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Laboratoire de santé publique du Québec (LSPQ), the Centre d’expertise en analyses environnementales du Québec (CEAEQ), the Régie du bâtiment du Québec (RBQ), the hospital infection prevention and control team, and the retirement home administrators involved in this outbreak investigation.

Funding

All authors received salary support from their respective organizations to complete this work.