Relaying the burden of diphtheria in Canada with hospital data

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 47 No. 10, October 2021: Influenza Vaccine

Date published: October 2021

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 47 No. 10, October 2021: Influenza Vaccine

Surveillance

Describing the burden of diphtheria in Canada from 2006 to 2017, using hospital administrative data and reportable disease data

Dolly Lin1, Brigitte Ho Mi Fane2, Susan G Squires2, Catherine Dickson2

Affiliations

1 School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON

2 Centre for Immunization and Respiratory Infectious Diseases, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Lin D, Ho Mi Fane B, Squires SG, Dickson C. Describing the burden of diphtheria in Canada from 2006 to 2017, using hospital administrative data and reportable disease data. Can Commun Dis Rep 2021;47(10):414–21. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i10a03

Keywords: discharge data, notifiable disease, Discharge Abstract Database, DAD, Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, CNDSS, surveillance, incidence rate, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, vaccine-preventable disease, VPD

Abstract

Background: Canada has maintained a low incidence of toxigenic diphtheria since the 1990s, supported by continued commitment to publicly funded vaccination programs.

Objective: To determine whether hospitalization data, complemented with notifiable disease data, can describe the toxigenic respiratory and cutaneous diphtheria burden in Canada, and to assess if Canada is meeting its diphtheria vaccine–preventable disease-reduction target of zero annual cases of locally transmitted respiratory diphtheria.

Methods: Diphtheria-related hospital discharge data from 2006 to 2017 were extracted from the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), and diphtheria case counts for the same period were retrieved from the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS), for descriptive analyses. As data from the province of Québec are not included in the DAD, CNDSS cases from Québec were excluded.

Results: A total of 233 diphtheria-related hospitalizations were recorded in the DAD. Of these, diphtheria was the most responsible diagnosis in 23. Half the patients were male (52%), and 57% were 60 years and older. Central region (Ontario) accounted for the most discharge records (61%), followed by Prairie region (Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan; 23%). Cutaneous diphtheria accounted for 43% of records, and respiratory diphtheria accounted for 3%, with the remainder being other diphtheria complications or site unspecified. Two records with diphtheria as the most responsible diagnosis resulted in inpatient deaths. Eighteen cases of diphtheria were reported through CNDSS. Cases occurred in all age groups, with the largest proportions among those aged 20 to 59 years (39%) and those aged 19 years and younger (33%). Cases were only reported in the Prairie (89%) and West Coast (British Columbia; 11%) regions.

Conclusion: Hospital administrative data are consistent with the low incidence of diphtheria reported in CNDSS, and a low burden of respiratory diphtheria in Canada. Although Canada appears to be on track to meet its disease-reduction target, information on endemic transmission is not available.

Introduction

Diphtheria is a now-rare vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) associated with a wide range of clinical illnesses, depending on the infection site and the toxigenicity of the bacteria. Classic respiratory diphtheria describes toxin-mediated pseudomembranous respiratory disease associated with inflammation in the throat, high fatality rates and severe complications affecting the heart and nervous systemFootnote 1. Case series from Canada, consistent with global surveillance, have found that the disease burden is increasingly attributed to cutaneous, non-pseudomembranous respiratory and systemic disease from toxigenic and non-toxigenic strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and C. ulceransFootnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8. In addition to disease burden, other toxigenic Corynebacteria (C. ulcerans or C. pseudotuberculosis) and non-toxigenic C. diphtheriae may serve to maintain a reservoir for toxigenic respiratory diphtheriaFootnote 2Footnote 4Footnote 8.

Countries with diphtheria vaccine coverage similar to Canada's report sporadic toxigenic respiratory diphtheria mostly associated with travel to endemic countriesFootnote 2Footnote 5Footnote 9Footnote 10. The last known fatal case of diphtheria in Canada, described in a case report published in 2021, occurred in a traveller who was not up to date with relevant vaccinesFootnote 10.

Canada has maintained a low incidence of toxigenic diphtheria, both respiratory and cutaneous, since the 1990s, with 0–5 cases of toxigenic respiratory or cutaneous diphtheria reported annually from 1991 to 2017Footnote 11. The low burden of diphtheria is likely sustained by universal immunization programming; 76% of Canadian two-year-olds and 81% of seven-year-olds were fully immunized for diphtheria toxoid in 2017Footnote 12. Consistent with its commitment to World Health Organization disease elimination goals, Canada's VPD-reduction targets aim to achieve zero annual cases of respiratory diphtheria resulting from exposure in Canada by 2025Footnote 13. However, infection site and travel history are not reportable with current nationally notifiable disease data. This makes it difficult to determine if Canada has achieved its target for reducing the number of cases of respiratory diphtheria.

This study aims to determine whether hospital administrative data, with information on site of infection, can add to the data in the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS) in order to better understand the burden of toxigenic respiratory and cutaneous diphtheria in Canada. Doing so could more effectively enable us to assess if Canada is meeting its diphtheria VPD-reduction target.

Methods

Data sources

Hospitalizations

Hospital discharge records for all patients admitted for diphtheria to any Canadian acute care hospital, between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2017, were extracted in January 2020 from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) patient-specific Discharge Abstract Database (DAD). These dates were selected to cover the period from when all provinces and territories had fully implemented International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10-CA) codes up to 2017, to correspond with the time period for which reportable disease data are currently available. The DAD records approximately 75% of all acute care hospital discharges in Canada as data from Québec are not includedFootnote 14.

Diphtheria hospitalizations were defined as those with ICD-10-CA discharge diagnoses corresponding to diphtheria (A36.0, A36.1, A36.2, A36.3, A36.8 or A36.9). All levels of diagnoses were used in this study, including most responsible diagnosis (the diagnosis that contributes the most to the length of hospital stay) and other diagnoses (secondary diagnoses, pre-admission or post-admission comorbidities). Respiratory diphtheria was identified by codes A36.0 through A36.2, and diphtheria not otherwise specified A36.9 concurrently with an upper respiratory disease code (J00–J06, J30–J39). Cutaneous diphtheria was identified by code A36.3. Other diphtheria complications were identified by code A36.8; complications include diphtheric cardiomyopathy, radiculomyelitis, polyneuritis, tubulo-interstitial nephropathy, cystitis, conjunctivitis and other diphtheritic complications.

The ICD-10-CA codes were assigned by trained medical coders based on hospital discharge notes and do not differentiate between toxigenic and non-toxigenic disease.

Health card numbers were used to identify repeat hospitalization events.

National case counts

The CNDSS collects nationally notifiable disease reports from provincial and territorial public health authorities, which obtain data from local and regional public health authoritiesFootnote 15. Confirmed cases of diphtheria from 2006 to 2017 were extracted from the CNDSS database in December 2019Footnote 11, with cases from Québec excluded.

Before 2008, the national diphtheria case definition was limited to the isolation of the species C. diphtheriae from an appropriate clinical specimenFootnote 16. In May 2008, the national case definition was revised to limit laboratory confirmation to toxigenic C. diphtheriae or other Corynebacterium species (C. ulcerans or C. pseudotuberculosis) isolated from an appropriate clinical specimen, which now includes wounds and other cutaneous sitesFootnote 17Footnote 18. See Appendix A for the two versions of the confirmed case definitions.

Record level data from the DAD and the CNDSS do not include information on results of case investigation to identify the source of exposure.

Analysis

Records were aggregated by year of admission in the DAD and year of reporting in the CNDSS. We conducted descriptive analyses of hospitalization records and case reports by year, age group, sex and region. Data were grouped by region: West Coast (British Columbia), Prairie (Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan), Central (Ontario), Atlantic (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island) and Northern (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut). Due to low counts, age groups in years were limited to 0 to 19, 20 to 59 and 60 and older.

We obtained denominators for rate calculations from census and intercensal projections published by Statistics Canada, excluding the population of QuébecFootnote 19. Average annual crude hospitalization rate and average annual crude case incidence rate were used to compare diphtheria-related hospitalization and cases by age, sex and region. We used annual hospitalization rate and case incidence rate to compare rates by data source over time. Discharge status (discharged alive or dead) and admittance to a special care unit (such as a high dependency unit, intensive care unit or critical care unit) were used to describe the severity of the disease for discharges where diphtheria was the most responsible diagnosis. Readmissions were defined as hospitalizations that occurred more than once for the same patient from 2006 to 2017. Analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. Small numbers are more susceptible to change and so corresponding rates should be interpreted with caution.

Results

Case distribution

A total of 233 diphtheria hospitalizations for 230 individual patients were recorded in the DAD from 2006 to 2017. Approximately half of the records were male (52%), and 57% were patients 60 years old and older. During the study period, Central region (which excludes Québec) represented 61% (n=141) of all discharge records, followed by Prairie region (23%, n=54), West Coast (8%, n=19), and Atlantic (7%, n=16) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Diphtheria-related hospitalizations | CNDSS (n=18) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All diagnoses (n=233) | Most responsible diagnosis (n=23) | |||||||||

| n | % | Average annual crude hospitalization rate per 100,000 population | n | % | Average annual crude hospitalization rate per 100,000 population | n | % | Average annual crude incidence rate per 100,000 population | ||

| Median age (range) | 64 (<1–97) | 47 (1–92) | 16.5 (<1–42)Table 1 Footnote a | |||||||

| Age groups in years | 0–19 | 18 | 8 | 0.019 | –Table 1 Footnote b | –Table 1 Footnote b | 6 | 33 | 0.006 | |

| 20–59 | 82 | 35 | 0.035 | 11 | 48 | 0.005 | 7 | 39 | 0.003 | |

| ≥60 | 133 | 57 | 0.157 | 9 | 39 | 0.010 | 5 | 28 | 0.006 | |

| Sex | Female | 112 | 48 | 0.054 | 11 | 48 | 0.010 | 7 | 39 | 0.005 |

| Male | 121 | 52 | 0.059 | 12 | 52 | 0.011 | 11 | 61 | 0.003 | |

| Region | West Coast | 19 | 8 | 0.035 | –Table 1 Footnote b | –Table 1 Footnote b | 2 | 11 | 0.004 | |

| Prairie | 54 | 23 | 0.073 | 7 | 30 | 0.009 | 16 | 89 | 0.022 | |

| Central | 141 | 61 | 0.089 | 12 | 52 | 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Atlantic | 16 | 7 | 0.056 | –Table 1 Footnote b | –Table 1 Footnote b | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Northern | –Table 1 Footnote b | –Table 1 Footnote b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Diphtheria type | Respiratory | 8 | 3 | N/A | –Table 1 Footnote b | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Cutaneous | 100 | 43 | N/A | 5 | 22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Other (with complications) | 76 | 33 | N/A | 6 | 26 | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Unspecified | 49 | 21 | N/A | 9 | 39 | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

The annual number of hospitalizations were between 13 and 31, with an average of 19 records (Table 1).

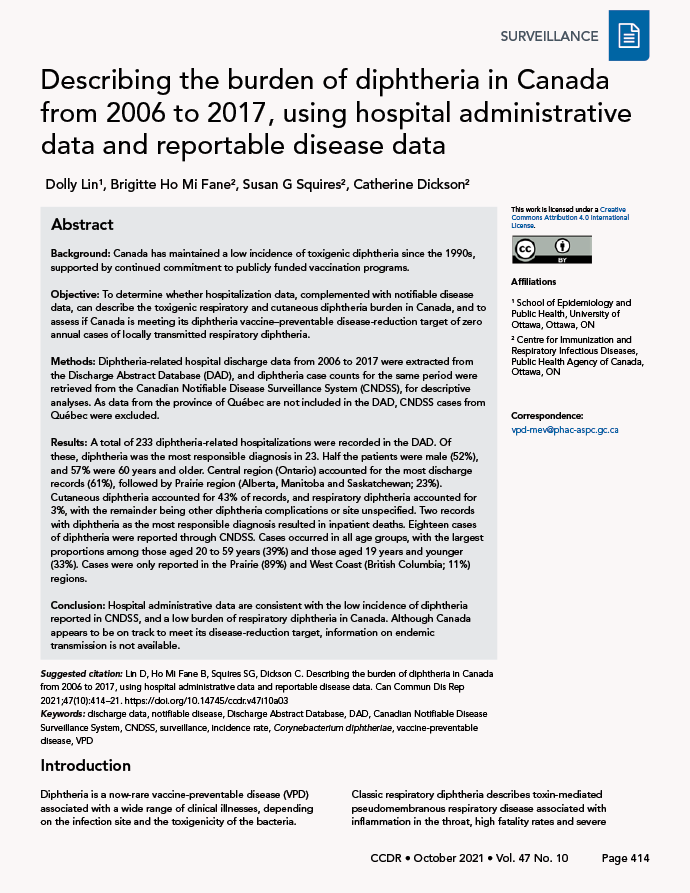

Cutaneous diphtheria accounted for the largest proportion of hospitalization records (43%; annual average of eight hospitalizations), followed by other diphtheria with complications (33%; annual average of six hospitalizations) and unspecified diphtheria (21%; annual average of four hospitalizations). None of the other diphtheria or unspecified diphtheria was concurrent with an upper respiratory disease code. Respiratory diphtheria accounted for 3% of all diphtheria-related hospitalizations, with an annual average of one hospitalization (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Distribution of diphtheria hospitalizations for all levels of diagnosis, by site of infection and year, 2006–2017

Text description: Figure 1

| Diphtheria | Respiratory diphtheria | Cutaneous diphtheria | Other diphtheria, complications | Unspecified diphtheria | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 0% | 40% | 35% | 25% | 100% |

| 2007 | 0% | 40% | 20% | 40% | 100% |

| 2008 | 6% | 39% | 50% | 6% | 100% |

| 2009 | 0% | 30% | 39% | 30% | 100% |

| 2010 | 0% | 48% | 29% | 23% | 100% |

| 2011 | 0% | 60% | 27% | 13% | 100% |

| 2012 | 0% | 50% | 30% | 20% | 100% |

| 2013 | 14% | 27% | 41% | 18% | 100% |

| 2014 | 15% | 46% | 8% | 31% | 100% |

| 2015 | 0% | 47% | 37% | 16% | 100% |

| 2016 | 0% | 56% | 33% | 11% | 100% |

| 2017 | 14% | 36% | 36% | 14% | 100% |

Three patients had two diphtheria-related discharge records during the study period. Of these three patients, two had a diagnosis of cutaneous diphtheria and one of unspecified diphtheria; the diagnostic codes for each of these cases did not change their classification of diphtheria type between hospital discharges.

Between 2006 and 2017, 18 cases of diphtheria were reported through CNDSS, and 61% were male (Table 1). The annual number of cases were between 0–4, with an average of 1.5. The highest proportion of CNDSS cases occurred among 20 to 59-year-olds (39%) followed by those aged 19 years and younger (33%). While the lowest proportion of cases occurred among CNDSS cases aged 60 years and older (28%), this group represented the highest (57%) and second highest (39%) of diphtheria-related hospitalizations for all diagnosis and most responsible diagnosis respectively. In contrast with hospitalization data, cases occurred mostly in the Prairie region, with 89% of all cases reported from 2006 to 2017. The remaining cases (11%) were reported in the West Coast region.

Indicators of severity

Of the 233 diphtheria-related hospitalizations, 23 (10%) had diphtheria as the most responsible diagnosis. Of the 23 hospitalization records, unspecified diphtheria and other diphtheria accounted for the majority (65%, n=15) (Table 1). All respiratory and cutaneous diphtheria hospitalizations were reported in adults aged 20 years and older.

The median length of stay in an acute care facility was three days (range: 1–24 days) for hospitalizations with respiratory diphtheria and six days (range: 2–39 days) for hospitalizations with cutaneous diphtheria as the most responsible diagnosis (Table 2). Of the 23 hospitalizations with diphtheria as the most responsible diagnosis, five were admitted to special care units and two resulted in inpatient deaths. Both fatalities were in adults with a diagnosis of either diphtheria with complications or unspecified diphtheria.

| Characteristics (number of cases) | Median length of hospital stay in days | Number of special care unit admissions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Range | |||

| Age group in years | 0–19 (n=3) | 3 | 3–5 | –Table 2 Footnote a |

| 20–59 (n=11) | 3 | 1–24 | –Table 2 Footnote a | |

| >60 (n=9) | 14 | 5–39 | –Table 2 Footnote a | |

| Overall (n=23) | 6 | 1–39 | 5 | |

| Diphtheria type | Respiratory diphtheriaTable 2 Footnote a | 3 | 1–24 | –Table 2 Footnote a |

| Cutaneous diphtheria (n=5) | 6 | 2–39 | 0 | |

| Other (with complications) (n=6) | 5.5 | 1–35 | –Table 2 Footnote a | |

| Diphtheria unspecified (n=9) | 8 | 2–37 | –Table 2 Footnote a | |

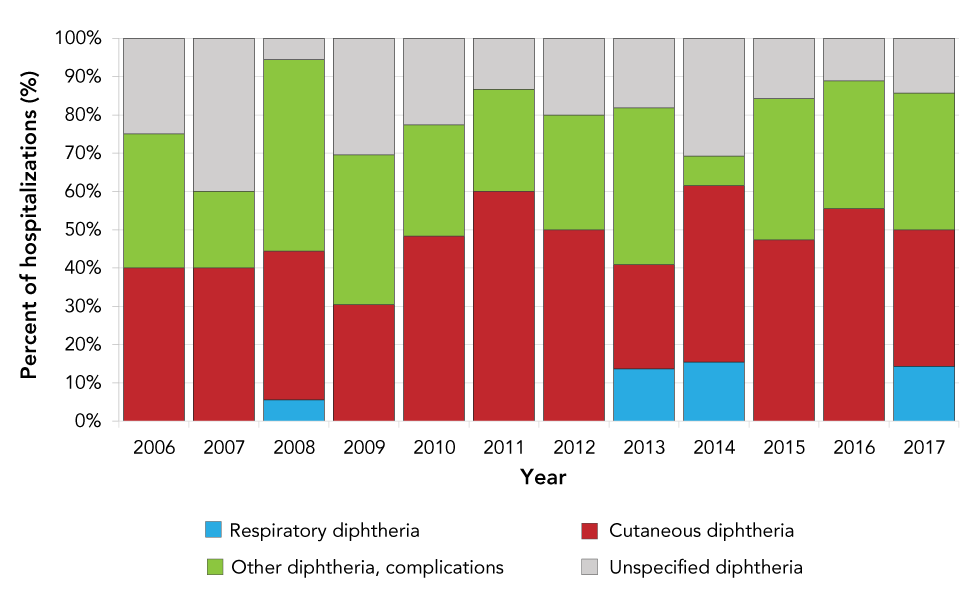

From 2006 to 2017, the number of hospitalizations with diphtheria as the most responsible diagnosis was within the same range (annual average of 1.9 cases, range 0–4) as the number of diphtheria cases reported through CNDSS, although age distribution and region differed. Breaking down hospitalization records by diphtheria type, the number of respiratory diphtheria hospitalizations for all levels of diagnosis (0–3 hospitalizations per year) and most responsible diagnosis (0–1 hospitalization per year) do not differ substantially. This results in average incidence rate of less than 0.01 hospitalizations per 100,000 population for respiratory diphtheria. The average incidence rate for reported diphtheria cases in CNDSS during the same period was less than 0.01 cases per 100,000 population (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Diphtheria-related hospitalization rates for all levels of diagnosis (A) and most responsible diagnosis (B) reported in the DAD, and incidence rate of diphtheria cases in the CNDSS (C), by year, 2006–2017

Text description: Figure 2

| Year | Any diphtheria—all diagnoses | Respiratory diphtheria—all diagnoses | Cutaneous diphtheria—all diagnoses | Any diphthteria—MRD | Respiratory diphtheria—MRD | Cutaneous diphtheria—MRD | CNDSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2007 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| 2008 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 |

| 2009 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 2010 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 2011 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 2012 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 2015 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 2016 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2017 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Discussion

With this study, we attempted to describe the burden of toxigenic respiratory and cutaneous diphtheria in Canada. We also tried, using a combination of hospital administrative and notifiable disease data, to examine whether we are meeting Canada's diphtheria VPD target. Overall, rates of diphtheria remained consistently low in Canada, at less than 0.06 per 100,000 per year. The DAD recorded 233 diphtheria-related hospitalizations. Of these, 23 had diphtheria as the most responsible diagnosis. Half the patients were male (52%), and most (57%) were 60 years old and older. Central region accounted for the most discharge records (61%), followed by the Prairie region (23%). Cutaneous diphtheria accounted for 43% of records, and respiratory diphtheria accounted for 3%, with the remainder being other diphtheria with complications or site unspecified. Eighteen cases of toxigenic diphtheria were reported through CNDSS over the same period. Cases occurred in all age groups, with the largest proportions among 20 to 59-year-olds (39%) and those aged 19 years old and younger (33%). Cases were only reported in the Prairie (89%) and West Coast (11%) regions.

The number of diphtheria-related hospitalizations is much higher than the number of cases reported through CNDSS, and the age and geographic distribution also differ. This suggests that these datasets do not necessarily capture the same individuals, although a comparison of the geographic breakdown of cases suggests that up to 50% of CNDSS cases may be represented in DAD cases with diphtheria as most responsible diagnosis. For context, Savage et al. found health administrative data in Ontario to have 69% to 86% sensitivity and 0.3% to 41.3% positive predictive value for hepatitis A, enteric fever and malariaFootnote 20. The DAD counts diphtheria cases based on clinical information in the medical chart and can include nonreportable non-toxigenic disease requiring hospitalization or diagnosed prior to or during hospitalizationFootnote 6Footnote 7. In contrast, the CNDSS focuses on toxigenic Corynebacterium species with confirmed toxin production by specialized assays in order to capture possible diphtheria toxoid VPDs. As a result, DAD hospitalizations may be less specific for toxigenic diphtheria and capture more individuals with non-toxigenic diphtheria, such as the elderly and people with comorbiditiesFootnote 14Footnote 18. This is supported by the overrepresentation of those aged over 60, those with cutaneous diphtheria and other diphtheria complications (myocarditis, neuritis) classified as conditions not most responsible for hospitalization (secondary diagnoses, pre-admission or post-admission comorbidities), without concurrent respiratory diagnostic codes (75.5%; Table 1). The much higher diphtheria case counts recorded in the DAD than in the CNDSS suggest that this system is picking up on non-toxigenic cases in addition to the toxigenic cases the CNDSS captures.

Most diphtheria cases recorded in the DAD and the CNDSS are adults (67%–92%; see Table 1), which is consistent with high national childhood immunization coverage. Further investigation with individual-level immunization data for cases could examine whether waning immunity in adults is a concernFootnote 21Footnote 22.

Geographic distribution differed between hospitalization and reportable disease data: all regions (except Northern) reported at least one hospitalization with a most responsible diagnosis of diphtheria, but the Prairie and West Coast regions accounted for all diphtheria cases in the CNDSS. There may also be differences in how the ICD-10-CA codes for diphtheria are applied between provinces or between institutionsFootnote 23. The National Microbiology Laboratory documented that the majority of C. diphtheriae and C. ulcerans isolates received from 2006 to 2019 for toxigenicity testing were from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and ManitobaFootnote 4, consistent with CNDSS case reports. Somewhat surprising was the high proportion of diphtheria-related hospitalizations reported in Ontario, despite the very small number of isolates sent from Ontario to the National Microbiology Laboratory for toxigenicity testingFootnote 4. Colleagues from Public Health Ontario confirmed that, to their knowledge, their laboratory conducted most, if not all, diphtheria testing in the province and that they had not received the number of samples positive for C. diphtheriae and C. ulcerans that the hospital discharge data from Ontario suggest (Personal communication, J.V. Kus and S.E. Wilson, January and March 2021). This discrepancy suggests that the DAD may be overcounting cases. It is possible that a past history of diphtheria infection or a case being worked up with a differential diagnosis that included diphtheria, even if cultures turned out to be negative, might have still been coded as diphtheria in the DAD.

This study is the first to describe health administrative data for diphtheria in Canada. Given that the CNDSS does not differentiate between respiratory and cutaneous diphtheria, examining patterns in hospitalizations with diphtheria ICD-10-CA codes over time in the DAD is useful for describing the severity of disease and frequency at which respiratory diphtheria cases are seen in hospital, even if it cannot identify the respiratory cases that are toxigenic. The inclusion of the DAD in this analysis also characterizes the burden of non-toxigenic disease, providing a broader picture than what the CNDSS reports.

Strengths and limitations

This study was limited by several factors. Firstly, the small counts of diphtheria limited the ability to conduct analyses adjusting for all of age, sex, geographic distributions and time, concurrently. Secondly, the DAD and the CNDSS use different case definitions, leading to different estimates of the burden of disease. Third, the representativeness of this study on the national burden of diphtheria could be improved by including data from Québec. During the study period, from 2006 to 2017, one case was reported from Québec through CNDSS. The case was a cutaneous diphtheria caused by C. ulceransFootnote 9.

Our study was also limited by the lack of individual-level linkage between datasets. As a result, we could not apply diphtheria source attribution or quantification of disease burden through capture–recaptureFootnote 20.

Surveillance of diphtheria by both the DAD and the CNDSS show temporally stable low rates, robust to changes in CNDSS case definition in 2008–2009, changes in DAD ICD-10-CA coding system in 2001–2005, and changes in laboratory detection methods for CorynebacteriaeFootnote 4Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 23. Zero to one hospitalization per year were reported with a most responsible diagnosis of respiratory diphtheria, which suggests that Canada is on track to meet the VPD target of zero annual cases of respiratory diphtheria resulting from exposure in Canada. However, as neither the CNDSS nor the DAD capture exposure data, further work is needed to capture information on site of exposure in order to fully demonstrate that Canada is meeting its disease-reduction target for diphtheria. While cases attributed to travel have not been thoroughly studied, many countries without endemic diphtheria report sporadic cases associated with travel to endemic countriesFootnote 3Footnote 5Footnote 8. We would expect similar patterns in Canada despite reports of small localized clusters of cutaneous diphtheria in vulnerable populations with comorbidities such as hepatitis C infection, diabetes, alcoholism, intravenous drug use, poverty and housing insecurityFootnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8.

Conclusion

A brief investigation of hospital administrative and notifiable disease data confirms stable low incidence of diphtheria reported in CNDSS and low burden of respiratory diphtheria in Canada. Although this study indicates that Canada is on track to meet its disease-reduction target of zero annual cases of respiratory diphtheria as a result of exposure in Canada, information on endemic transmission of diphtheria cases is limited.

Further study of recent C. diphtheriae strains as well as enhancing reporting to include travel history and site of infection could improve our understanding of the current situation in Canada and provide a better tool to ensure that Canada is meeting its VPD-reduction targets by 2025.

Authors' statement

DL — Conceptualization, writing–original draft, writing–review & editing

BHMF — Formal analysis, writing–review & editing

SGS — Conceptualization, writing–review & editing

CD — Conceptualization, writing–review & editing

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank KA Bernard, SE Wilson, JV Kus and T Harris for their valuable feedback and assistance with data interpretation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Appendix A

National case definition for diphtheria prior to May 2008Footnote 11

Confirmed case

Laboratory confirmation of infection:

- Isolation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae from an appropriate clinical specimen

OR

- Histopathologic diagnosis of diphtheria

OR

Epidemiologic link (contact within two weeks prior to onset of symptoms) to a laboratory-confirmed case PLUS at least one of the following:

- Upper respiratory tract infection (nasopharyngitis, laryngitis or tonsillitis) with or without an adherent nasal, tonsillar, pharyngeal and/or laryngeal membrane, plus at least one of the following:

- Gradually increasing stridor

- Cardiac (myocarditis) and/or neurologic involvement (motor and/or sensory palsies) 1–6 weeks after onset

- Death, with no known cause

- Systemic manifestations compatible with diphtheria in a person with an upper respiratory tract infection or infection at another sit

National case definition for diphtheria as of May 2008Footnote 12

Confirmed case

Clinical illness (see "Clinical evidence" section) or systemic manifestations compatible with diphtheria in a person with an upper respiratory tract infection or infection at another site (e.g. wound, cutaneous) PLUS at least one of the following:

- Laboratory confirmation of infection:

- Isolation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae with confirmation of toxin from an appropriate clinical specimen, including the exudative membrane

OR - Isolation of other toxigenic Corynebacterium species (C. ulcerans or C. pseudotuberculosis) from an appropriate clinical specimen, including the exudative membrane

OR - Histopathologic diagnosis of diphtheria

- Isolation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae with confirmation of toxin from an appropriate clinical specimen, including the exudative membrane

OR

- Epidemiologic link (contact within two weeks prior to onset of symptoms) to a laboratory-confirmed case

Laboratory comments

Isolation of Corynebacterium species capable of producing diphtheria toxin (C. diphtheriae, C. ulcerans or C. pseudotuberculosis) should be tested using the modified Elek assay OR assay for the presence of the diphtheria tox gene, which, if detected, should be tested for expression of diphtheria toxin using the modified Elek assay.

Clinical evidence

Clinical illness is characterized as an upper respiratory tract infection (nasopharyngitis, laryngitis or tonsillitis) with or without an adherent nasal, tonsillar, pharyngeal and/or laryngeal membrane, plus at least one of the following:

- Gradually increasing stridor

- Cardiac (myocarditis) and/or neurologic involvement (motor and/or sensory palsies) one to six weeks after onset

- Death, with no known cause