Asymptomatic household cluster of COVID-19 in Northern Canada

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 47-2: HIV Testing in Canada in the Past Decade 2009–2019

Date published: February 2021

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 47-2, February 2021: HIV Testing in Canada in the Past Decade 2009–2019

Rapid communication

Familial cluster of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases in a First Nation community in Northern Saskatchewan, Canada

Shree Lamichhane1, Sabyasachi Gupta1, Grace Akinjobi1, Nnamdi Ndubuka1,2

Affiliations

1 Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority, Prince Albert, SK

2 School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Lamichhane SR, Gupta S, Akinjobi G, Ndubuka N. Familial cluster of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases in a First Nation community in Northern Saskatchewan, Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep 2021;47(2):94–6. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i02a01

Keywords: COVID-19, asymptomatic, First Nation, Canada, familial cluster, transmission

Introduction

A novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2), causing a cluster of respiratory infections, initially appeared in Wuhan, China in December 2019. The outbreak spread rapidly around the world and, as of December 7, 2020, a total of 67,440,864 cases have been confirmed in 191 countries, resulting in 1,541,661 deaths. A wide range of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptoms has been reported, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe that may appear 2–14 days after exposure to the virus. Lately, it has been observed that the asymptomatic or presymptomatic cases make up what may be a large portion of all COVID-19 infections. If these cases cannot be identified and appropriately isolated for medical intervention, this could limit the effectiveness of transmission prevention measures.

We are reporting a familial cluster of COVID-19 cases that started with a paucisymptomatic case and led to two asymptomatic cases. In our familial cluster, five out of nine cases (55%) were found to be presymptomatic at the time of testing, while two cases (22%) remained asymptomatic throughout the course of the infection.

Current situation

Since the pandemic started, the province of Saskatchewan, Canada has reported 11,475 COVID-19 cases. Of these cases, 910 were from Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority (NITHA) First Nations communities in the Northern Saskatchewan (http://www.nitha.com/). Given that the asymptomatic and presymptomatic persons are potential source of COVID-19 infectionFootnote 1Footnote 2, we are reporting a First Nations familial cluster from the Northern Saskatchewan where the infection started with a paucisymptomatic case and led to two asymptomatic cases. Increasingly, it is recognized that Indigenous determinants of health, such as overcrowding, poverty, impact of Indian residential school history, younger demographics, weak public health infrastructure, limited access to quality health services and higher rate of co-morbidities, can worsen disease outbreaksFootnote 3. Specifically, crowded housing conditions may result in ineffective physical distancing and inadequate infection control measures with increased likelihood of COVID-19 transmission. There is also an increased risk of poor mental health, hospitalizations and severe outcomes among those First Nationals individuals with immunocompromised and chronic disease conditionsFootnote 4. As many First Nation communities are now being affected by COVID-19 outbreaks, this report also provides data necessary for the development and application of public health strategies within other First Nation communities.

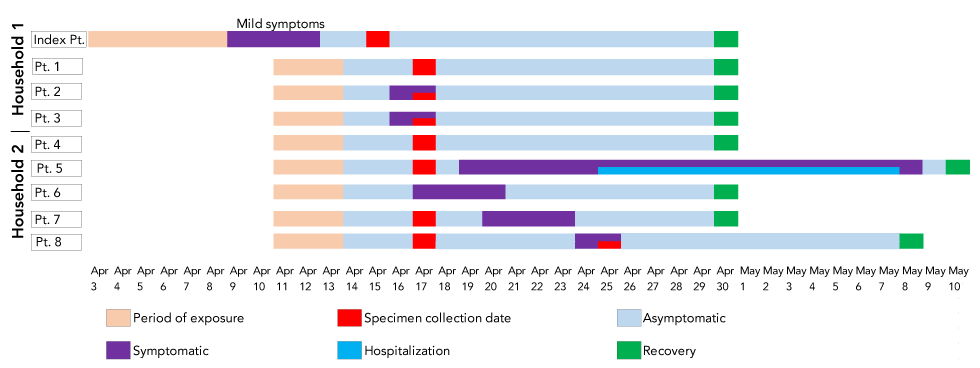

Our index patient (20–29 years age group) acquired the infection from a close contact who returned to the community from an area of high transmission out-of-province and subsequently developed a mild symptom (rhinitis), which resolved within a few days. The index patient attended a family dinner two days later where further transmission appears to have occurred. After contact tracing, eight more cases were identified; three from the index's household and five from another household visited by the index patient (Figure 1). The exact timing of transmission exposure could not be ascertained because the persons with whom the index patient was in contact were living in overcrowded settings, and exposure was ongoing. No other possible exposures were identified that could link to these COVID-19 infection. All the COVID-19-positive patients and their close contacts were isolated in accordance with the provincial standards.

Figure 1: Timeline of exposure to index and household cases in familial cluster

Text description: Figure 1

The figure shows confirmed COVID-19 positive cases and timeline of events from exposure to recovery in two households. Cases were reported to Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority (NITHA) between April 15, 2020 and April 28, 2020. The index case had mild symptoms while individual was in a family dinner with a group of people during the Easter long weekend. The Easter dinner was the implicating event which resulted to significant transmission to household and close contacts. Five out of eight close contacts (63%) that became a case were asymtomatic at testing. Patient 1 and patient 4 were asymtomatic throughout and patient 5 was hospitalized. All cases except patient 5 and 8 had recovered after 14 days of isolation. Patient 8 developed symptoms on day 12 of isolation and the isolation period was extended.

Patient 2 (10–19 years age group) and Patient 3 (30–39 years age group) from Household 1 developed very mild symptoms (loss of taste and smell) for two days; however, Patient 1 (40–49 years age group) did not developed any symptoms. From Household 2, Patient 6 became ill with a sore throat. Patient 5 (30–39 years age group, with a pre-existing chronic medical condition) reported the loss of taste and smell, followed by cough, shortness of breath and diarrhea. As the patient's condition worsened, this patient was hospitalized and recovered within two weeks. Patient 7 (an infant) became ill with a fever and cough; however, the patient's condition improved without medical intervention. Patient 8 (20–29 years age group), who initially tested negative for COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction testing, developed symptoms (wheeze and fever) at 12 days following exposure and was found to be COVID-19-positive on re-testing. Overall, three patients from Household 2 were found to be asymptomatic at time of testing; of them, one (Patient 4, 5–9 years age group) did not develop any symptoms throughout the isolation period.

In our familial cluster, five out of nine cases (55%) were presymptomatic at time of testing while two cases (22%) did not develop any symptoms throughout approximately two weeks of follow-up. Our index patient had only mild symptoms and was unaware of heightened COVID-19 risk status, which added to uncertainty and delayed the early detection and isolation. Despite these concerns, six out of nine cases developed only mild symptoms and recovered with minimal medical attention, highlighting the possibility of containment of COVID-19 cases outside the hospital with appropriate guidance and oversight. As rural communities can face different challenges around COVID-19 depending on where they located, each community and community members should assess their unique susceptibility and social vulnerability to COVID-19 and respond according to the public health measures. Relevant measures to prevent the COVID-19 community spread in these vulnerable communities would include avoiding non-essential travels outside the community and limiting interactions between different households.

Conclusion

Early detection and isolation of symptomatic COVID-19 patients with effective contact tracing investigations are an important disease containment strategy. As asymptomatic and presymptomatic transmission are biologically plausibleFootnote 1Footnote 2, such transmission could limit the effectiveness of control measuresFootnote 2Footnote 5Footnote 6. This case summary highlights the importance of early detection, contact tracing, testing of all close contacts-regardless of the presence of symptoms-and preventive 14 days self-isolation of people returning to communities from high transmission areas to prevent asymptomatic spread in remote communities. It also highlights the need for low threshold for testing individuals with very mild symptoms in the 14 days post-return from high transmission areas. Transmissibility by asymptomatic or presymptomatic patients in the setting of crowded living conditions, such as those often seen in remote, northern and Indigenous communities, can contribute to higher transmission rates.

Authors' statement

- SRL — Literature review, writing–draft

- SG — Data analysis, writing–draft

- GA — Writing-review and editing

- NN — Conception, design, data interpretation, critical review

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority and partner communities for their hard work and contribution to this article.

Funding

None.

The content and view expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, Zimmer T, Thiel V, Janke C, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Drosten C, Vollmar P, Zwirglmaier K, Zange S, Wölfel R, Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar;382(10):970-1. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2001468

- Footnote 2

-

Zhang J, Tian S, Lou J, Chen Y. Familial cluster of COVID-19 infection from an asymptomatic. Crit Care 2020 Mar;24(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2817-7

- Footnote 3

-

Richardson KL, Driedger MS, Pizzi NJ, Wu J, Moghadas SM. Indigenous populations health protection: a Canadian perspective. BMC Public Health 2012 Dec;12(1):1098. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1098

- Footnote 4

-

Schiavo R, May Leung M, Brown M. Communicating risk and promoting disease mitigation measures in epidemics and emerging disease settings. Pathog Glob Health 2014 Mar;108(2):76-94. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000127

- Footnote 5

-

Wei WE, Li Z, Chiew CJ, Yong SE, Toh MP, Lee VJ. Presymptomatic Transmission of SARS-CoV-2-Singapore, January 23-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):411-5. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6914e1.htm

- Footnote 6

-

Tian S, Hu N, Lou J, Chen K, Kang X, Xiang Z, Chen H, Wang D, Liu N, Liu D, Chen G, Zhang Y, Li D, Li J, Lian H, Niu S, Zhang L, Zhang J. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Infect. 2020;80(4):401-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.018