West Nile virus surveillance system: One Health approach

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 48-5, May 2022: Vector-Borne Infections–Part 1: Ticks & Mosquitoes

Date published: May 2022

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 48-5, May 2022: Vector-Borne Infections–Part 1: Ticks & Mosquitoes

Overview

An overview of the National West Nile Virus Surveillance System in Canada: A One Health approach

Dobrila Todoric1, Linda Vrbova1, Maria Elizabeth Mitri1, Salima Gasmi1, Angelica Stewart1, Sandra Connors1, Hui Zheng1, Annie-Claude Bourgeois1, Michael Drebot2, Julie Paré3, Marnie Zimmer4, Peter Buck1

Affiliations

1 Centre for Food-borne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

2 Zoonotic Diseases and Special Pathogens, National Microbiology Laboratory Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, MB

3 Animal Health Epidemiology and Surveillance, Science Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Saint-Hyacinthe, QC

4 Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative—National Office, Saskatoon, SK

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Todoric D, Vrbova L, Mitri ME, Gasmi S, Stewart A, Connors S, Zheng H, Bourgeois A-C, Drebot M, Paré J, Zimmer M, Buck P. An overview of the National West Nile Virus Surveillance System in Canada: A One Health approach. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022;48(5):181–7. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v48i05a01

Keywords: West Nile virus, surveillance, epidemiology, Canada, One Health

Abstract

National West Nile virus (WNV) surveillance was established in partnership with the federal, provincial and territorial governments starting in 2000, with the aim to monitor the emergence and subsequent spread of WNV disease in Canada. As the disease emerged, national WNV surveillance continued to focus on early detection of WNV disease outbreaks in different parts of the country. In Canada, the WNV transmission season occurs from May to November. During the season, the system adopts a One Health approach to collect, integrate, analyze and disseminate national surveillance data on human, mosquito, bird and other animal cases. Weekly and annual reports are available to the public, provincial/territorial health authorities, and other federal partners to provide an ongoing national overview of WNV infections in Canada. While national surveillance allows a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction comparison of data, it also helps to guide appropriate disease prevention strategies such as education and awareness campaigns at the national level. This paper aims to describe both the establishment and the current structure of national WNV surveillance in Canada.

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV) was first isolated in 1937 from the blood of a febrile patient in the West Nile district of UgandaFootnote 1. Since its first discovery, it has spread through Africa, the Middle East, Asia, southern Europe, Oceania and, more recently, the Western HemisphereFootnote 2. In North America, the virus was first detected in New York City in late August of 1999Footnote 3 during an outbreak of meningoencephalitis. This outbreak was the first recognized introduction of WNV into North America.

West Nile virus belongs to a family of viruses called Flaviviridae. The virus is typically maintained in a mosquito-bird enzootic transmission cycle and is transmitted to humans and other mammals by the bite of an infected female mosquito. West Nile virus is primarily transmitted by the Culex species of mosquitoes in Canada, with principal vectors being Culex pipiens and Culex tarsalisFootnote 1. The Culex mosquitoes that are implicated in this cycle feed exclusively on avian blood and are referred to as amplification vectors, while the Aedes and Ochleratus mosquitoes and other Culex species that transmit WNV to humans, horses and non-avian vertebrates have more general feeding habits and are referred as bridge vectorsFootnote 4. Humans and other mammals are considered dead-end hosts as they are unable to transmit the disease due to insufficient viremia. Although WNV is primarily a mosquito-borne disease, transmission of WNV to humans via blood transfusion and tissue and organ transplantation has also been reported on rare occasionsFootnote 5.

In human WNV infections, 70% to 80% of people remain asymptomaticFootnote 1. Symptomatic individuals may experience a range of signs and symptoms including fever; however, fewer than 1% will develop severe neurological manifestations, including meningitis and encephalitisFootnote 1. The overall case fatality rate in patients that develop neurological manifestations is 4% to 14%, with a higher rate in older populationsFootnote 1. Currently, there is no WNV vaccine for humans, and prevention of transmission depends on the use of personal protective measures and sustained vector control.

The objective of this article is to describe the establishment and structure of national WNV surveillance in CanadaFootnote 6. This is a system that has adopted a One Health approach in connecting partners as well as integrating surveillance data, given the interconnectedness of human health with that of animals and the environment. The description covers the four main system components: human surveillance; mosquito surveillance; dead bird surveillance; and animal surveillance.

National West Nile Virus Surveillance in Canada

Establishment of the surveillance system

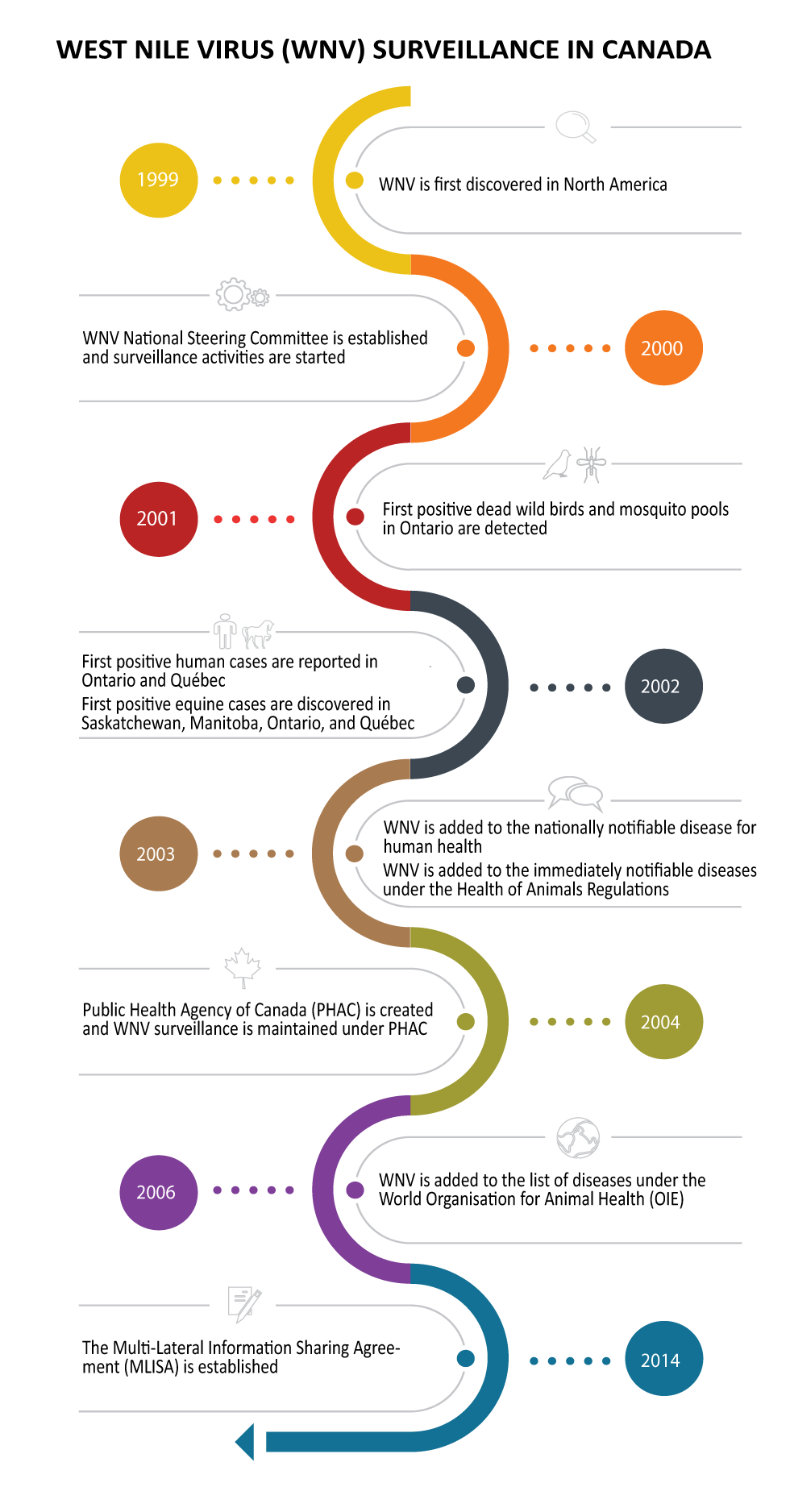

Following the incursion of WNV in and around New York City, and given its close geographic proximity to Canada, the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control, Health Canada and the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health created a National Steering Committee (NSC) in late winter 2000. The principal mandate of the NSC was to develop pan-Canadian surveillance guidelines that could assist with detection and response to the virus in Canada. The committee was composed of representatives from other government and non-government departments: the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC) and provincial/territorial human and animal health partners. The NSC agreed to develop a surveillance system to track and monitor WNV across Canada that closely followed a template employed by the United StatesFootnote 7 that set out the guidelines on criteria for disease surveillance, prevention, education and vector controlFootnote 8. In September 2004, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) was established in response to growing concerns regarding Canada's public health systemFootnote 9; in December 2006, the NSC was confirmed as a legal entity by the Public Health Agency of Canada Act. As such, the WNV surveillance system, previously under Health Canada, moved to PHAC.

Dead bird surveillance in Canada started in 2000 and was conducted from the Atlantic provinces to Saskatchewan; no evidence of WNV activity was detected that year. West Nile virus was first reported in Canada in the municipality of Windsor, Ontario, in August 2001Footnote 10; the virus was detected in the wild bird population. Dead corvids, including species such as ravens, jays and crows, are known to be reliable indicators of WNV activity in a given geographical areaFootnote 10. Subsequently, 12 health units across southern Ontario reported 128 WNV-infected wild birds during the 2001 transmission season. The movement of WNV from the United States to Canada has been linked to the migration of birdsFootnote 10. Likewise, it has been suggested that the westward movement of WNV across Canada is largely associated with the flight routes of migratory birdsFootnote 11. Dispersion of the virus in Canada in 2001 was correlated with some of the notable flyways of migratory birds which include the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central and Pacific flywaysFootnote 11.

During 2000 and 2001, parts of Atlantic Canada, Ontario and Québec surveyed adult and larval mosquito populations to determine the presence/absence of mosquito populations in selected rural and peri-urban locationsFootnote 12. On August 31, 2001, Ontario isolated WNV from Culex pipiens/restuans mosquito poolsFootnote 12. Mosquito pool surveillance started in 2002, with an aim to obtain baseline information on the number of mosquito species present and their relative abundance in a given area.

The first human cases of WNV in Canada were detected in Québec and Ontario in August 2002. Also, during that same year, the first cases of WNV infections in equine populations were reported in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Québec.

Evolution of the surveillance system

In June 2003, WNV became a nationally-notifiable human disease. Since 2003, WNV human infection has been a reportable disease in the provinces and territories. As a result, when a probable or confirmed case is diagnosed by a laboratory, it must be reported to the local public health authority in the respective jurisdiction; however, reporting at the national level is maintained only on a voluntary basis.

The WNV surveillance system quickly evolved into a multi-species surveillance system focusing on human, dead bird, mosquito and animal data (Figure 1). Initially, dead bird surveillance proved to be an efficient early predictor of where human cases could occur. Dead bird surveillance was particularly useful in the detection of new areas with WNV activity as the virus was introduced into and spread across Canada; however, this type of surveillance became less useful as the virus became established. As such, many jurisdictions eventually turned their efforts to mosquito pool testing, which provides a more specific indication of spatial and temporal risk for human infection.

Figure 1: National West Nile Virus Surveillance System timeline in Canada

Text description: Figure 1

This figure shows the National West Nile Virus (WNV) Surveillance System timeline in Canada. The timeline has eight milestones, as the following:

Heading in yellow 1999 following with:

- WNV is first discovered in North America

Heading in orange 2000 following with:

- WNV National Steering Committee is established and surveillance activities are started

Heading in red 2001 following with:

- First positive dead wild birds and mosquito pools in Ontario are detected

Heading in dark gray 2002 following with:

- First positive human cases are reported in Ontario and Québec

- First positive equine cases are discovered in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Québec

Heading in brown 2003 following with:

- WNV is added to the nationally notifiable disease for human health

- WNV is added to the immediately notifiable diseases under the Health of Animals Regulations

Heading in green 2004 following with:

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is created and WNV surveillance is maintained under PHAC

Heading in purple 2006 following with:

- WNV is added to the list of diseases under the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)

Heading in blue 2014 following with:

- The Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement (MLISA) is established

A multi-species surveillance system for WNV was important since the interaction of bird populations and mosquitoes is integral to the dynamics of WNV transmission and infection. Furthermore, different vectors have specific transmission efficiencies that might trigger localized outbreaks of WNVFootnote 13. Over the years, the surveillance system has undergone reviews and updates, including on elements such as the national case definitionFootnote 14 and reporting practices. Considering the complexity of the WNV transmission cycle, a One Health approachFootnote 15 was implemented to enhance understanding of species involved and develop an effective and sensitive surveillance system. Over time, the system and its purpose evolved to the following objectives that guide the national WNV surveillance system:

- To track WNV disease and describe national trends and burden of disease in humans

- To monitor changes in WNV carrying mosquito populations and other non-human vertebrate hosts each week in advance of epidemic activity affecting humans

- To provide timely information (e.g. weekly surveillance reports) on WNV across all provinces/territories that informs the development of public health messaging to prevent human infections

Work carried out at the local-level (i.e. public health units), regional-level and national-level complies with global regulations such as meeting the 2005 International Health Regulations obligationsFootnote 16.

The WNV surveillance system comprises four components: 1) human surveillance; 2) mosquito surveillance; 3) dead bird surveillance; and 4) animal surveillance.

Human surveillance

Human surveillance of WNV is a passive case-based system. Human cases are reported voluntarily (i.e. no legal obligation) to PHAC by provincial or territorial public health authorities. Canadian Blood Services/Héma-Québec participate in the surveillance system via provincial health authorities, by testing for WNV in donations collected from Canadian blood donorsFootnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19. At the national-level, human case data are reported to PHAC during the WNV season, from June to November; however, at the provincial and regional levels, data are collected on a year-round basis.

Key variables collected include age, sex, disease onset date, case classification (probable and confirmed) and clinical status (asymptomatic, non-neurological and neurological). Health authorities at the provincial-level perform laboratory testing related to the WNV infections.

Mosquito surveillance

The aim of mosquito surveillance is to help detect proximal risk of WNV in a specific region, so proactive measures can be taken. West Nile virus risk varies across Canada; as a result, the mosquito pool surveillance is conducted in some jurisdictions and not others. During 2001, WNV activity in mosquitoes was detected in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec and Nova Scotia, and intensified surveillance was put in place for mosquito pool testingFootnote 12. Over the years, the amount of mosquito surveillance has fluctuated and currently, four provincial partners—Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Québec—conduct active mosquito surveillance. Mosquito pool testing for WNV occurs from June to November and data are shared by provincial partners on a weekly basis.

Mosquitoes are trapped by using a variety of techniques. The trapping is carried out weekly at fixed and mobile (changed based on current season) sites that represent the most likely WNV mosquito vector habitat in that specific communityFootnote 20. Some of the traps used are to sample host-seeking mosquitoes. The most commonly used traps are based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) miniature light trap that use carbon dioxide (CO2) as an additional attractantFootnote 20. The main advantage of the CDC miniature light trap is that it attracts a wide range of mosquito species. Another common trap is the gravid trap that specifically targets gravid females—mosquitoes carrying mature eggs. The advantage of gravid traps is that they attract female mosquitoes who already took a blood meal, increasing the prospect of detecting WNV in the specific region where the sampling is occurringFootnote 20. In addition to the CDC miniature light traps and gravid traps, there are several other traps that can be used such as the CDC resting trap, which uses aspirators, and host-baited trapsFootnote 20.

Dead bird surveillance

Dead bird surveillance consists of testing dead wild birds for WNV in jurisdictions across Canada. The information obtained from this passive surveillance serves as an early indicator of viral activity in the natural reservoir host of this virus, and thus the potential to spread to mosquitoes, humans and other animalsFootnote 21.

In 2000, the CWHCFootnote 21, formerly known as Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre, started dead bird surveillance and post mortem testing on birds across Canada. Since 2009, approximately 300 birds are tested each year for WNVFootnote 21; however, the annual amount of wild bird testing is influenced by the severity of the WNV season. The CWHC tests dead birds for WNV from late April until the first hard frost.

Animal surveillance

Under the Health of Animals Regulations, WNV has been an immediately notifiable disease in animals since 2003. All veterinary laboratories in Canada are required to report suspect or confirmed WNV cases in all animal species to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. In horses, the case definition is based on clinical signs and laboratory diagnostic resultsFootnote 22. West Nile virus surveillance assists with export certification, meeting international reporting obligations to the World Animal Health Organisation and informing public health on possible risk areas. Furthermore, among domestic animals, horses are susceptible to encephalitis related to WNV infection and can therefore serve as indicators of viral activity in rural communitiesFootnote 7 and provide national insight on the epidemiology of WNV in CanadaFootnote 23. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency shares surveillance data with PHAC's Canadian WNV surveillance system on a weekly basis during the WNV seasonFootnote 22. It includes mostly equine cases of WNV, but occasionally other mammals (alpacas, sheep and goats), domestic birds and poultry, and some zoo animals. Because testing is owner-requested and funded, wildlife cases are mostly unavailable. Equine WNV surveillance data, which is the most consistently reported, is leveraged to help address gaps in environmental surveillance for geographical regions where mosquito and bird surveillance are not currently in placeFootnote 7Footnote 23 and can provide complementary coverage in areas where no human cases have been diagnosed. Since horses can be vaccinated against WNV and the frequency of vaccination is variable, the surveillance numbers are likely an underreporting of actual infections.

Evolution of laboratory diagnostics for West Nile virus surveillance

Laboratory diagnostics are out of the scope of this paper; however, it is important to mention that currently there are several laboratory diagnostic procedures available for documenting WNV cases. Laboratory diagnostics can be divided into the following three categories: virus isolation/culture; serological assays for detecting viral specific antibodies; and WNV antigen detection/nucleic acid sequence-based amplificationFootnote 7. The advancement from immunohistochemistry-immunofluorescence assay to nucleic acid sequence-based amplification is a notable evolution in the laboratory methodology for the detection of WNV in various field collected specimens (e.g. bird tissues) from the early years of WNV surveillance. Polymerase chain reaction-based testing continues to be the procedure of choice for detection of WNV-positive mosquito pools. These advancements allowed for the technical transfer of molecular procedures to testing sites outside of the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Further refinements and availability of commercial IgM enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) tests for screening human sera for WNV antibodies was a major contributor to higher throughput screening of samples from suspect cases of virus infection.

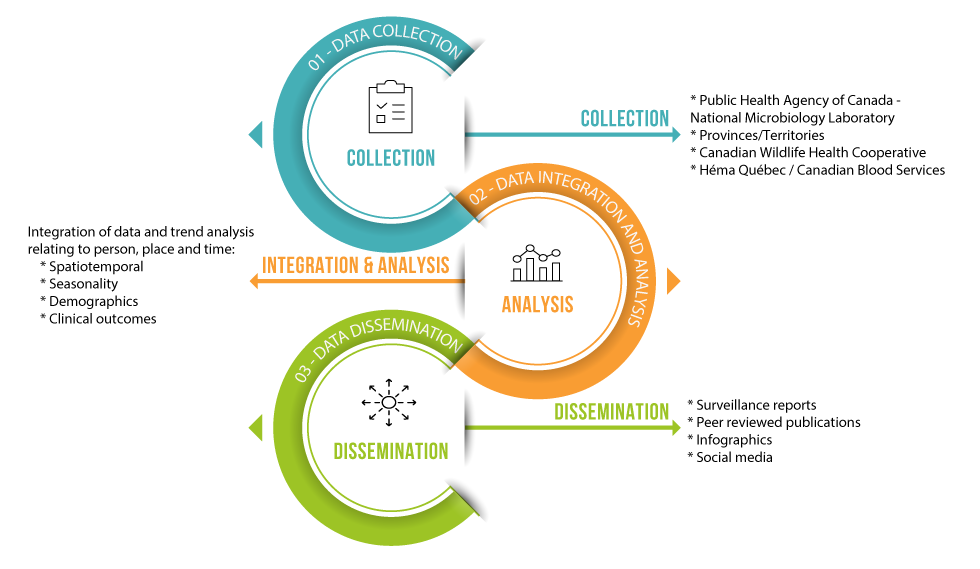

Collaboration to knowledge translation

To coordinate surveillance at the national-level, collaboration is needed between various federal/provincial/territorial partners and non-governmental organizations. During the WNV surveillance season, data on human cases, animal cases and positive mosquito pools are submitted directly to PHAC by participating provincial/territorial governments on a weekly basis. Data reported to PHAC between 2002 and present day are stored in a database before being analyzed and disseminated through various channels (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Flow of information for the National West Nile Virus Surveillance System

Text description: Figure 2

This figure shows the flow of information for the National West Nile Virus Surveillance System. The chart has three elements flowing from text in blue 01 – Data Collection to text in orange 02 – Data Integration and Analysis to text in green 03 – Data Dissemination.

Each element contains the following:

Main text in blue 01 – Data Collection pointing with an arrow to Collection, which leads to the following:

- Public Health Agency of Canada – National Microbiology Laboratory

- Provinces/Territories

- Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative

- Héma Québec/Canadian Blood Services

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Main text in orange 02 – Data Integration and Analysis pointing with an arrow to Integration and Analysis, which leads to the following:

Integration of data and trend analysis relating to person, place and time:

- Spatiotemporal

- Seasonality

- Demographics

- Clinical outcomes

Main text in green 03 – Data Dissemination pointing with an arrow to Dissemination, which leads to the following:

- Surveillance reports

- Peer reviewed publications

- Infographics

- Social media

Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement

In 2014, the federal/provincial/territorial Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement (MLISA)Footnote 24 was completed to address some of the information sharing challenges between provincial/territorial public health data contributors and surveillance programs at the national level. The Agency worked closely with the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network's National Surveillance Information Task Group to develop this agreement. While continuing to respect the existing legislation within jurisdictions, MLISA outlines when, what, and how infectious disease and emerging public health event information will be shared between and among jurisdictionsFootnote 24. The WNV surveillance system complies with the regulations in the main clauses of the MLISA. These clauses include regulations ensuring that a review period is provided to key partners and stakeholders, as well as custodians of the data, to comment on various surveillance products and publications before being released into the public domain.

Knowledge translation and public awareness campaigns

Data from WNV surveillance inform policy decisions and awareness campaigns that contribute to the reduction of WNV disease in Canada. Some of these efforts include public health messaging through various social media platforms, and digital signage on Service Canada/Passport Centre screens. In addition, weekly surveillance reports and annual surveillance reports are posted on the Government of Canada websiteFootnote 25 for public access along with periodic publications in the Canada Communicable Disease Report or other scientific peer-reviewed journals.

In First Nations communities, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch regional staff advise Chiefs, councils and federal departments on emerging needs for WNV public health control measures. First Nations residents obtain information about specific WNV activity in their community through their assigned Environmental Public Health Officers, Community Health Centre and/or Nursing Stations. This includes information on surveillance activities and case counts.

Along with local and provincial/territorial information that is released to the public, information on WNV prevention (including handling of dead wild birds) and WNV risk, symptoms and treatment is publicly available on www.canada.ca. The Agency also provides information to health professionals on WNV clinical assessment, diagnosis and prognosis.

Future opportunities

When establishing the WNV surveillance system in Canada, a One Health approach evolved to respond to the inherent complexities of this emerging disease and its transmission dynamics. The integrated surveillance approach provides a template for surveillance systems on other mosquito-borne diseases such as Bunyaviruses, including the California serogroup (Jamestown Canyon and Snowshoe hare virus) and Cache valley virusesFootnote 26 in Canada. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of having effective surveillance systems in place to deal with emerging diseases.

Conclusion

The Canadian WNV surveillance system is based on a collaboration of federal/provincial/territorial partners involved in public and animal health. This integrated surveillance initiative is an example of One Health—a collaborative approach that engages an array of partners for the collection and analysis of information on WNV activity in humans, mosquitoes, wild birds and horses. The goal of the system is to reduce the risk of WNV infection in the human population and contribute to increased awareness of preventative measures. The WNV surveillance system meets the 2005 International Health Regulations obligations. The Public Health Agency of Canada, in collaboration with key partners, will continue to adapt and respond to the evolving nature of WNV and other mosquito-borne diseases.

Authors' statement

DT — Co-conceived manuscript idea, acquired information, researched and drafted the manuscript

MM, ACB, HZ — Co-conceived manuscript idea, participated in information acquisition and edited the manuscript

SG — Validated references and edited the manuscript

AS — Contributed to the manuscript draft, validated information and reviewed

SC — Created figures and validated information

MD — Contributed to the manuscript, validated information and reviewed

JP — Contributed to the manuscript, validated information and reviewed

MZ — Validated information and reviewed

LV, PB — Validated information, reviewed and edited the manuscript

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgments

The Public Health Agency of Canada would like to acknowledge participating federal, provincial and territorial governments and other stakeholders for their significant and ongoing efforts to support the West Nile virus Surveillance system in Canada by regularly providing human, mosquitoes, wild birds and equine surveillance data and giving their guidance.

Funding

None.