Factors linked with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae

Download this article as a PDF (446 KB)

Download this article as a PDF (446 KB)Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: CCDR Volume 50–6, June 2024: Cancer Vaccines

Date published: June 2024

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 50-6, June 2024: Cancer Vaccines

Scoping Review

Thematic description of factors linked with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in humans

Jamie Goltz1,2, Carl Uhland2, Sydney Pearce1, Colleen Murphy2, Carolee Carson2, Jane Parmley1

Affiliations

1 Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON

2 Centre for Food-borne, Infectious Diseases and Vaccination Programs Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, Guelph, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Goltz J, Uhland C, Pearce S, Murphy C, Carson CA, Parmley EJ. Thematic description of factors linked with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in humans. Can Commun Dis Rep 2024;50(6):211–22. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v50i06a04

Keywords: ESBL, Enterobacteriaceae, risk factors, humans, knowledge synthesis

Abstract

Background: Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae are associated with serious antimicrobial-resistant infections in Canadians. Humans are exposed to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae through many interconnected pathways. To better protect Canadians, it is important to generate an understanding of which sources and activities contribute most to ESBL exposure and infection pathways in Canada.

Objective: The aims of this scoping review were to thematically describe factors potentially associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization, carriage and/or infection in humans from countries with a very high human development index and describe the study characteristics.

Methods: Four databases (PubMed, CAB Direct, Web of Science, EBSCOhost) were searched to retrieve potentially relevant studies. Articles were screened for inclusion, and factors were identified, grouped thematically and described.

Results: The review identified 381 relevant articles. Factors were grouped into 13 themes: antimicrobial use, animals, comorbidities and symptoms, community, demographics, diet and substance use, health care, household, occupation, prior ESBL colonization/carriage/infection, residential care, travel, and other. The most common themes reported were demographics, health care, antibiotic use and comorbidities and symptoms. Most articles reported factors in hospital settings (86%) and evaluated factors for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections (52%).

Conclusion: This scoping review provided valuable information about which factor themes have been well described (e.g., health care) and which have been explored less frequently (e.g., diet or animal contact). Themes identified spanned human, animal and environmental contexts and settings, supporting the need for a diversity of perspectives and a multisectoral approach to mitigating exposure to antimicrobial resistance.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a real and growing public health threat Footnote 1. Infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing bacteria are a major concern because beta-lactam antibiotics are commonly used to treat a variety of infections, and some classes, such as third-generation cephalosporins and monobactams are listed as critically important for use in human medicine by the World Health Organization Footnote 2Footnote 3. Further, infections with ESBL-producing bacteria are associated with increased likelihood of severe illness and mortality and can result in treatment failures, which can lead to increased hospital-stay duration and hospital costs Footnote 4Footnote 5.

In 2018, it was reported that approximately one in four bacterial infections in Canada were resistant to first-line antibiotics, which led directly to approximately 14,000 deaths Footnote 5. Additionally, AMR has been reported to lead to negative socio-economic outcomes, including increased healthcare costs, loss of productivity, increased inequality and decreased trust in the government and public health agencies Footnote 5Footnote 6. Therefore, AMR consequences are far-reaching and have widespread implications to humans, animals and society.

The primary producers of ESBLs are Enterobacteriaceae, notably Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, and these bacteria are being increasingly identified in Canada, and worldwide Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae are widely dispersed among populations Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11, including carriage or colonization within healthy individuals, and those with serious infections (e.g., urinary tract, bloodstream, pneumonia) Footnote 5Footnote 12Footnote 13.

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae have also been detected in companion animals, livestock, wildlife, water, soil, vegetables, meat and seafood, all of which can be possible sources of exposure for humans Footnote 11Footnote 14Footnote 15. Because of the variety of exposure pathways, a One Health approach that considers the interconnections between humans, animals, and their shared environments is required to cover the full scope of this growing public health threat Footnote 16Footnote 17.

Past systematic reviews have explored factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization and infections Footnote 13Footnote 18Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27; however, systematic reviews are intentionally narrow in scope, providing knowledge on specific research questions. This project aimed to describe the breadth of factors previously reported to be associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Canada or similar countries. This information could be used to inform various parallel projects within the Public Health Agency of Canada, such as the Integrated Assessment Model of Antimicrobial Resistance (iAM.AMR) project Footnote 15Footnote 28, and to help better understand Canadians' exposure to antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. Therefore, the objectives of this scoping review were 1) to thematically describe factors potentially associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization, carriage and/or infection in humans from countries with a very high human development index, and 2) to describe the study characteristics.

Methods

Below the methods are described in brief. For a full description of the methodology, refer to Goltz et al. Footnote 29.

Protocol registration

An a priori protocol of this scoping review is available online. This review followed the methodological framework described by Arksey and O'Malley Footnote 30, and the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for Scoping Reviews Footnote 31.

Search strategy

Search terms and databases searched are described in the protocol document. Four databases (PubMed, CAB Direct, Web of Science and EBSCOhost) were searched through the University of Guelph McLaughlin Library to retrieve potentially relevant articles. The search string for this review was adapted from Murphy et al. Footnote 32, with consultation from co-authors, in addition to a University of Guelph librarian. All databases were filtered to only include articles published in English. The initial search was completed in August 2020 and updated in August 2021.

Search results were uploaded into the EndNote X9.3.3 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, United States), deduplicated, and then uploaded to DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada), for additional deduplication, eligibility screening and data extraction.

Eligibility criteria

To meet the inclusion criteria, articles needed to be primary research, be from countries similar to Canada with a very high human development index Footnote 33, be written in English, and contain quantifying associations between factors and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization, carriage and/or infection in humans. No articles were excluded based on publication year, study population characteristics (e.g., age, sex or health status) or study setting (e.g., household or hospital). These inclusion criteria were selected because of the Canadian focus of this article, and therefore aimed to identify articles with Canadian and similar populations. Further, only English articles were included due to available language resources. Relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded but their reference lists were used to identify additional articles that were not captured by the search.

Selection of articles

The DistillerAI tool feature was used to screen titles/abstracts. The DistillerAI tool was trained by two reviewers using 226 articles. Once trained, all titles/abstracts were screened by the DistillerAI tool and a human reviewer. Title/abstract screening conflicts were resolved by a third human reviewer. Articles included based on title/abstract had the full text screened by two reviewers and conflicts were resolved through discussion by the two reviewers.

Data charting

Following full text review, relevant data were charted using DistillerSR by a single reviewer. Data extracted included: publication year, study design, country region (based on World Health Organization regions) Footnote 34, data collection method (primary, e.g., questionnaire or interview; secondary, e.g., database or medical charts), sample setting (e.g., hospital), outbreak episode, age of participants, microorganisms evaluated, type of colonization, carriage, or infection evaluated and factor themes (n=13). A factor was defined as a measured observation (e.g., penicillin use) that was investigated for its relationship with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae Footnote 32Footnote 35. Individual factors were grouped into 13 themes created through an iterative process informed by previous work Footnote 15. Themes were 1) antimicrobial use (i.e., antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal), 2) animals (i.e., contact with animals), 3) comorbidities and symptoms (i.e., conditions or presenting symptoms), 4) community (i.e., factors that occur in the community), 5) demographics, 6) food and consumption, 7) health care (i.e., factors that occur in a hospital setting or are related to receiving health care), 8) household (i.e., factors that occur at the home), 9) occupation (i.e., factors related to employment), 10) prior ESBL colonization/carriage/infection, 11) residential care (i.e., factors that occur in a residential setting such as a nursing home), 12) travel (i.e., factors related to international travel) and 13) other factors (i.e., factors that did not fall into a previously defined theme). If a factor belonged to more than one theme (e.g., patient took antibiotics while on vacation), it was recorded in all relevant themes (e.g., antimicrobial use and travel).

Results

Study screening and inclusion

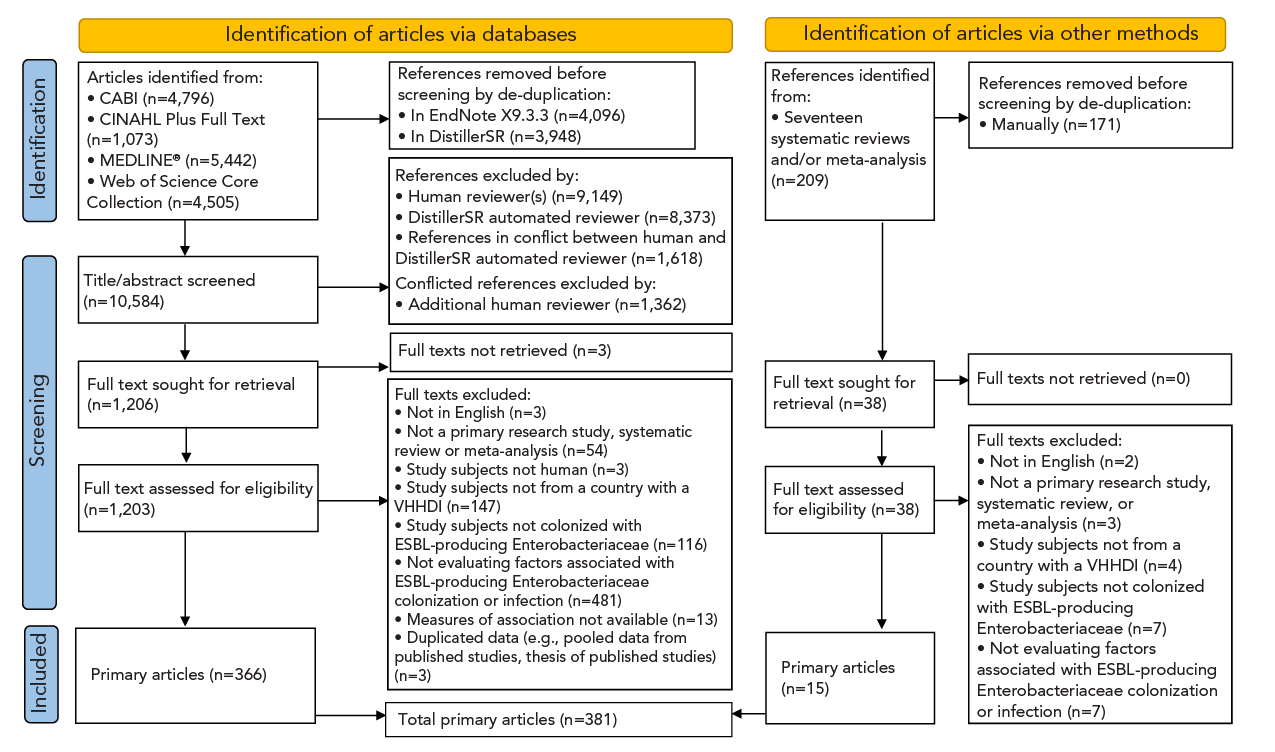

After deduplication, 10,584 eligible records were identified. Following screening (abstract/title, full text), 366 articles were included. Screening also identified 17 systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses and 15 additional articles were identified through review of their reference lists. Therefore, 381 articles were included in this review, published between 1991 and August 5, 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Text description

The figure shows a flow diagram illustrating the number of articles that were identified in the scientific literature that reported risk factors for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in humans. Initially, a total of 16,025 records were identified through online databases and reference lists of relevant systematic reviews. Following a meticulous de-duplication process, 10,584 unique articles remained. Subsequently, a rigorous screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 9,378 records, leaving 1,244 articles for full-text retrieval and further screening. Ultimately, 381 articles were deemed relevant and included in this scoping review.

Across the 381 included articles, factors were grouped into 13 themes: health care (n=325 articles), antimicrobial use (n=325), demographics (n=319), comorbidities and symptoms (n=307), residential care (n=76), travel (n=76), prior ESBL colonization/carriage/infection (n=44), food and consumption (n=44), household (n=29), occupation (n=29), animal (n=25), community (n=11) and other (n=146) (additional details available upon request). Each theme covered a wide range of risk factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (Table 1).

| Factor theme | Factor categories | Factor examples |

|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial use | Antibiotic, antiparasitic, antiviral, antifungal use | Penicillin use Amoxicillin-clavulanate use Fluconazole use |

| Status of antimicrobials | Mother given antibiotics before delivery Admitted on antibiotics Inadequate empirical antibiotic treatment |

|

| Animal | Animal contact | Cat owner Living with dogs Farm animal contact |

| Animal lifestyle | Pet given antibiotics ESBL in pigs Companion animal eats raw meat |

|

| Community | Community activities | Public swimming/bathing in freshwater or seawater Playing on a sports team Daycare attendance |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | History of a medical condition | AIDS Cancer Diabetes |

| Comorbidity scores | Charlson comorbidity index ICU chronic disease score Sequential organ failure assessment score |

|

| Symptoms | Blood pressure Fever Septic shock |

|

| Demographics | Demographic information | Age Ethnicity Language spoken |

| Health care | Healthcare setting | Admitted from home Admission to emergency department Prior ICU |

| Healthcare setting risks | ESBL-positive prior room occupant Hospital length of stay Hand disinfectant in the patient's room |

|

| Procedures or treatments | Chemotherapy Surgery Acid suppressor use |

|

| Household | Household members | Family member is a carrier (mother, father, sister) Children younger than 12 years old in the household Household member took antibiotics |

| Household setting risks | Shared use of towels Distance to nearest broiler farm |

|

| Residential care | Residential care stay | Nursing home residence Long-term care facility stay |

| Residential care setting risks | Use of shared bathroom Staff training in hand hygiene Existence of a preferential list of antibiotics |

|

| Food and consumption | Food and water type | Chicken consumption Seafood consumption Bottled water |

| Food and water source | Purchased from market/shop Own produce/local farmer Central water supply |

|

| Food and water handling | Sterilized feeding bottles Regular/sometimes hand washing before food preparation Dishcloth use longer than one day |

|

| Substance consumption | Alcohol Smoking Illicit drugs |

|

| Prior ESBL colonization/carriage/infection | Prior ESBL-producing organism | Prior ESBL colonization Prior ESBL infection |

| Occupation | Occupation type | Veterinarian Farmer Caregiver |

| Occupation setting risks | Average number of hours working on the pig farm per week Contact with patient's excretions Assistance in patient's wound care |

|

| Travel | Travel risks | Visited other country Health care abroad Accommodation type (e.g., camping, house, hotel, with locals) |

| Other | Acquisition/onset location | Community acquisition Acquired prior to admission Nosocomial onset |

| Time of acquisition | Season Year of sample |

|

| Details about bacteria | Resistant genes Polymicrobial information example |

|

Study characteristics

A summary description of the articles is reported in Table 2. Of the 381 articles included, 378 were observational study designs, and three were experimental. Most of the studies (n=235) were conducted in European Region countries, including six multinational studies (Table 2). Seven studies were conducted in Canada.

| Study characteristics | Number of articles | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Study design | ||

| Observational | 378 | 99 |

| Experimental | 3 | 1 |

| Country region | ||

| European RegionTable 2 footnote a | 235 | 62 |

| Western Pacific Region | 78 | 20 |

| Region of the Americas | 60 | 16 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 8 | 2 |

| Age group | ||

| Adults/young adults | 125 | 33 |

| Children | 40 | 11 |

| Neonates/newborns/infants | 19 | 5 |

| Multiple defined age groups (e.g., children and adults) | 15 | 4 |

| Elderly | 14 | 4 |

| Undefined | 168 | 44 |

| Setting where samples were obtainedTable 2 footnote b | ||

| Hospital | 328 | 86 |

| Non-hospital health care | 27 | 7 |

| Community | 22 | 6 |

| Residential care facilities | 16 | 4 |

| Outbreak | ||

| No | 363 | 95 |

| Yes | 18 | 5 |

| Factor data collection method | ||

| Secondary data (e.g., databases, medical charts) | 201 | 53 |

| Primary data (e.g., questionnaire, interview) | 76 | 20 |

| Multiple data collection methods (i.e., primary and secondary data) | 27 | 7 |

| Unclear | 77 | 20 |

| Microorganisms evaluated | ||

| EnterobacteriaceaeTable 2 footnote c | 154 | 40 |

| Escherichia coli | 78 | 20 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 42 | 11 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 4 | 1 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 2 | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 2 | 1 |

| Providencia stuartii | 1 | 1 |

| OtherTable 2 footnote d | 98 | 26 |

Over half (56%) of all articles reported data for specific age groups with the most common being adults/young adults (33%). Eighteen articles (5%) reported factors as part of an ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae outbreak (all in hospital settings). For most studies (53%), data were reported from secondary data sources (e.g., databases, medical charts), with 20% from primary data sources (e.g., questionnaires, interviews) and 7% from both primary and secondary data sources. For 20% of the studies, it was unclear how the data were obtained (Table 2).

Articles often reported factors for Enterobacteriaceae (40%), but many reported specific microorganisms including E. coli (20%), K. pneumoniae (11%), Enterobacter cloacae (1%), Klebsiella spp. (1%), Proteus mirabilis (1%), and Providencia stuartii (1%). Other articles sought to report different combinations of Enterobacteriaceae species (e.g., Klebsiella spp. and E. coli) (Table 2).

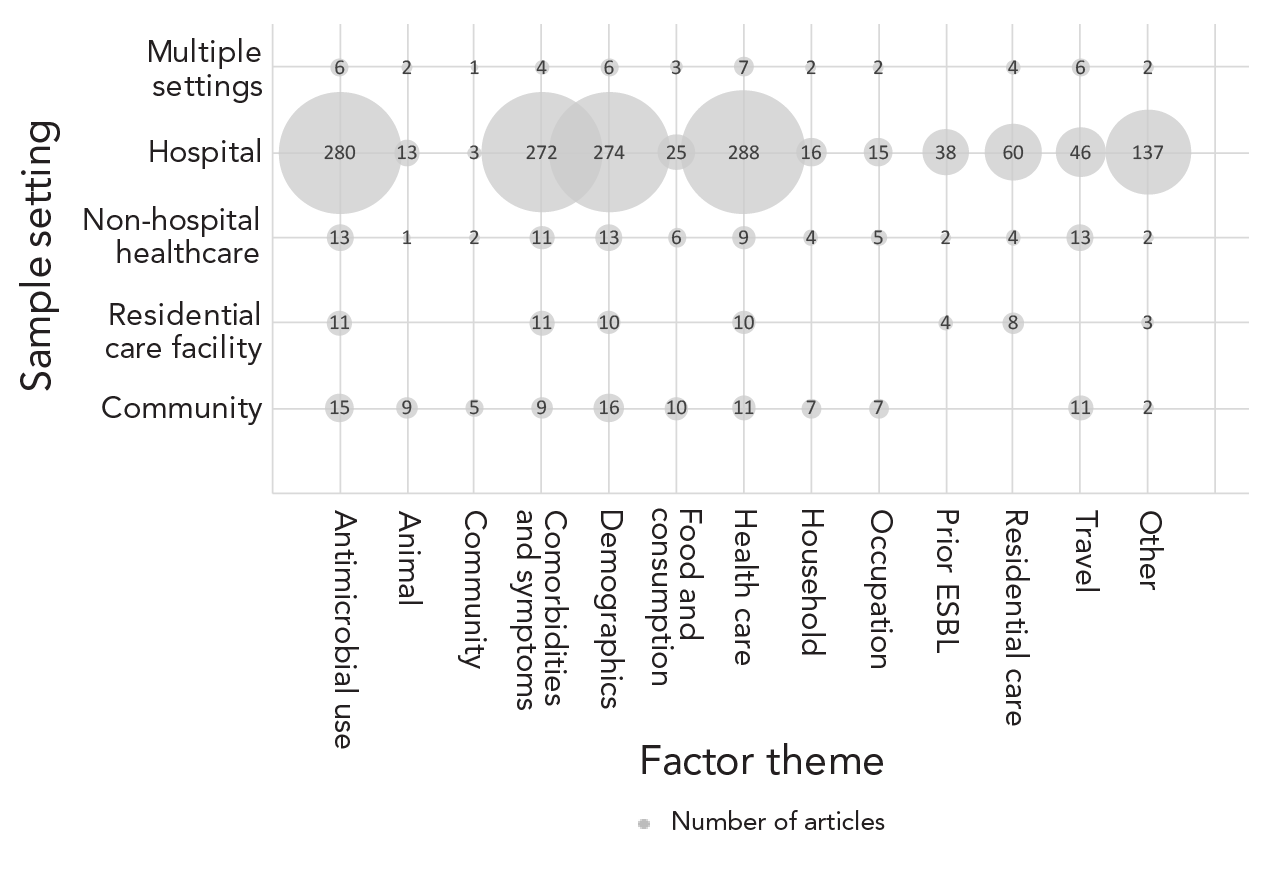

Most articles were performed in hospital settings (86%), followed by non-hospital healthcare settings (7%), community settings (6%), and residential care facilities (4%). Eleven of these articles were sampled from multiple of these different sample settings (Table 2). Overall, the highest number of articles identified for each factor theme were those that had performed their study in hospital settings, except for the community theme (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Text description

| Factor theme | Sample setting | Number of articles (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic use | Community | 15 |

| Antibiotic use | Residential care facility | 11 |

| Antibiotic use | Non-hospital healthcare | 13 |

| Antibiotic use | Hospital | 280 |

| Antibiotic use | Multiple settings | 6 |

| Animal | Community | 9 |

| Animal | Residential care facility | 0 |

| Animal | Non-hospital healthcare | 1 |

| Animal | Hospital | 13 |

| Animal | Multiple settings | 2 |

| Community | Community | 5 |

| Community | Residential care facility | 0 |

| Community | Non-hospital healthcare | 2 |

| Community | Hospital | 3 |

| Community | Multiple settings | 1 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Community | 9 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Residential care facility | 11 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Non-hospital healthcare | 11 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Hospital | 272 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Multiple settings | 4 |

| Demographics | Community | 16 |

| Demographics | Residential care facility | 10 |

| Demographics | Non-hospital healthcare | 13 |

| Demographics | Hospital | 274 |

| Demographics | Multiple settings | 6 |

| Food and consumption | Community | 10 |

| Food and consumption | Residential care facility | 0 |

| Food and consumption | Non-hospital healthcare | 6 |

| Food and consumption | Hospital | 25 |

| Food and consumption | Multiple settings | 3 |

| Health care | Community | 11 |

| Health care | Residential care facility | 10 |

| Health care | Non-hospital healthcare | 9 |

| Health care | Hospital | 288 |

| Health care | Multiple settings | 7 |

| Household | Community | 7 |

| Household | Residential care facility | 0 |

| Household | Non-hospital healthcare | 4 |

| Household | Hospital | 16 |

| Household | Multiple settings | 2 |

| Occupation | Community | 7 |

| Occupation | Residential care facility | 0 |

| Occupation | Non-hospital healthcare | 5 |

| Occupation | Hospital | 15 |

| Occupation | Multiple settings | 2 |

| Prior ESBL | Community | 0 |

| Prior ESBL | Residential care facility | 4 |

| Prior ESBL | Non-hospital healthcare | 2 |

| Prior ESBL | Hospital | 38 |

| Prior ESBL | Multiple settings | 0 |

| Residential care | Community | 0 |

| Residential care | Residential care facility | 8 |

| Residential care | Non-hospital healthcare | 4 |

| Residential care | Hospital | 60 |

| Residential care | Multiple settings | 4 |

| Travel | Community | 11 |

| Travel | Residential care facility | 0 |

| Travel | Non-hospital healthcare | 13 |

| Travel | Hospital | 46 |

| Travel | Multiple settings | 6 |

| Other | Community | 2 |

| Other | Residential care facility | 3 |

| Other | Non-hospital healthcare | 2 |

| Other | Hospital | 137 |

| Other | Multiple settings | 2 |

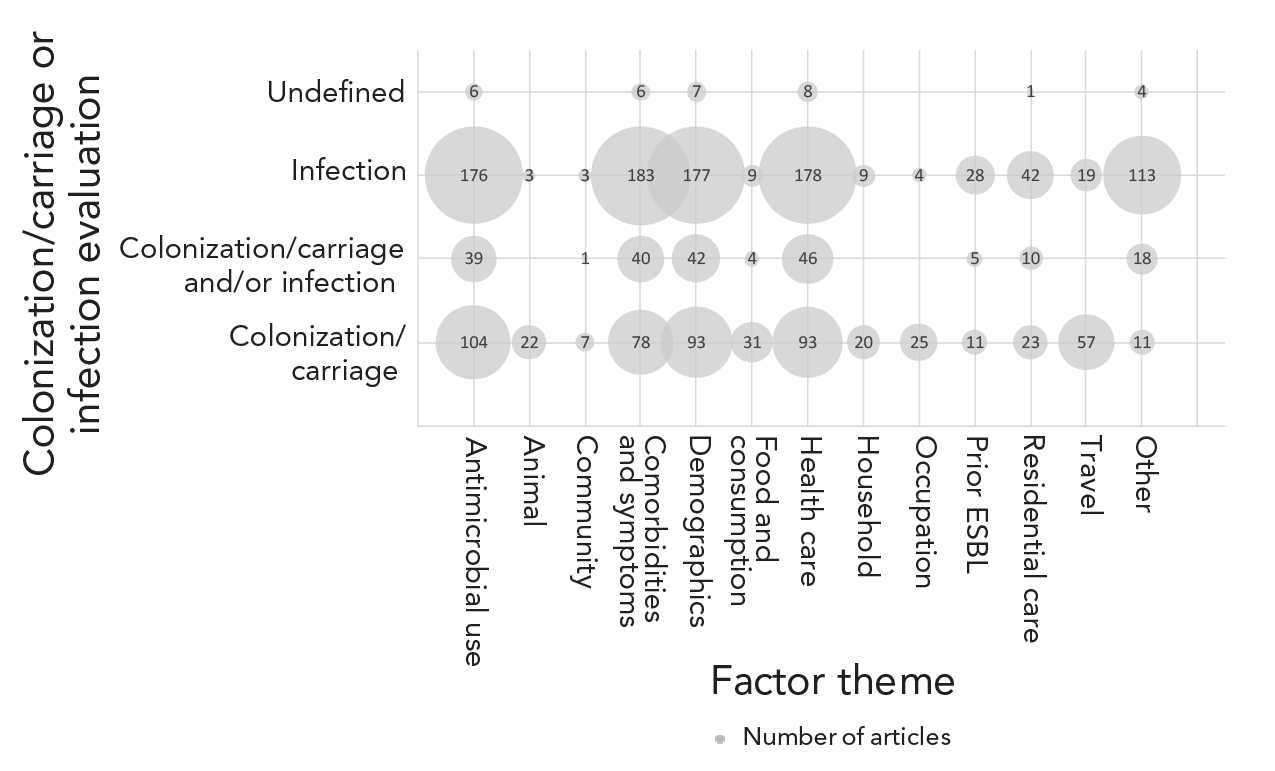

Articles reported factors for 1) infection (52%), 2) colonization/carriage (33%), and 3) colonization/carriage/infection (13%) (Table 3). Factors potentially associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections were reported in over half of the articles (52%) (mostly bloodstream infections or urinary tract infections). More articles identified factors for infection than colonization/carriage (Figure 3), especially for the factor themes antimicrobial use, demographics, comorbidities/symptoms and health care. Colonization/carriage was reported in a third of the articles (33%), with most focused on gastrointestinal carriage. Animal, community, food and consumption, household, occupation and travel themes were more frequently reported for colonization/carriage (Figure 3). For eight articles (2%) it was unclear whether the study was reporting colonization/carriage or infection.

| Colonization/carriage and/or infection details | Number of articlesTable 3 footnote a | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Infection | 198 | 52 |

| Bacteremia/bloodstream infection | 75 | 20 |

| Urinary tract infection | 52 | 14 |

| Non-specific cultures (e.g., general surveillance or database records) | 49 | 13 |

| Acute pyelonephritis | 5 | 1 |

| Acute bacterial prostatitis | 2 | 1 |

| Bacteremia/bloodstream infection and urinary tract infection | 1 | 1 |

| Bacteremia/bloodstream infection, urinary tract infection and catheter-associated infection | 1 | 1 |

| Bacteremic spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 1 | 1 |

| Catheter-associated urinary tract infection | 1 | 1 |

| Complicated cystitis | 1 | 1 |

| Foot infection | 1 | 1 |

| Genital tract infections | 1 | 1 |

| Peritonitis | 1 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 1 | 1 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 1 | 1 |

| Sternal wound infection | 1 | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection/acute pyelonephritis | 1 | 1 |

| Urosepsis | 1 | 1 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 1 | 1 |

| Colonization/carriage | 125 | 33 |

| Gastrointestinal (e.g., fecal, stool, rectal, peri-rectal) | 110 | 29 |

| Non-specific cultures (e.g., general surveillance or database records) | 5 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal and nasal | 2 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal and vaginal | 2 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal, vaginal and nasopharyngeal | 1 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal, nasal and navel | 1 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal, nasal, oropharyngeal and urine | 1 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal, nasal and throat | 1 | 1 |

| Skin | 1 | 1 |

| Urinary | 1 | 1 |

| Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 51 | 13 |

| Non-specific colonization/carriage and/or non-specific infection | 38 | 10 |

| Urinary colonization/carriage and/or urinary tract infection | 6 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal colonization/carriage and/or non-specific infection | 5 | 1 |

| Respiratory colonization/carriage and/or infection | 1 | 1 |

| Urinary colonization/carriage and/or urinary tract infection, cystitis and pyelonephritis | 1 | 1 |

| Unclear | 8 | 2 |

| Non-specific isolation | 7 | 2 |

| Urinary isolation | 1 | 1 |

Figure 3 - Text description

| Factor theme | Colonization/carriage or infection evaluated | Number of articles (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic use | Colonization/carriage | 104 |

| Antibiotic use | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 39 |

| Antibiotic use | Infection | 176 |

| Antibiotic use | Undefined | 6 |

| Animal | Colonization/carriage | 22 |

| Animal | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 0 |

| Animal | Infection | 3 |

| Animal | Undefined | 0 |

| Community | Colonization/carriage | 7 |

| Community | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 1 |

| Community | Infection | 3 |

| Community | Undefined | 0 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Colonization/carriage | 78 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 40 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Infection | 183 |

| Comorbidities and symptoms | Undefined | 6 |

| Demographics | Colonization/carriage | 93 |

| Demographics | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 42 |

| Demographics | Infection | 177 |

| Demographics | Undefined | 7 |

| Food and consumption | Colonization/carriage | 31 |

| Food and consumption | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 4 |

| Food and consumption | Infection | 9 |

| Food and consumption | Undefined | 0 |

| Health care | Colonization/carriage | 93 |

| Health care | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 46 |

| Health care | Infection | 178 |

| Health care | Undefined | 8 |

| Household | Colonization/carriage | 20 |

| Household | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 0 |

| Household | Infection | 9 |

| Household | Undefined | 0 |

| Occupation | Colonization/carriage | 25 |

| Occupation | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 0 |

| Occupation | Infection | 4 |

| Occupation | Undefined | 0 |

| Prior ESBL | Colonization/carriage | 11 |

| Prior ESBL | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 5 |

| Prior ESBL | Infection | 28 |

| Prior ESBL | Undefined | 0 |

| Residential care | Colonization/carriage | 23 |

| Residential care | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 10 |

| Residential care | Infection | 42 |

| Residential care | Undefined | 1 |

| Travel | Colonization/carriage | 57 |

| Travel | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 0 |

| Travel | Infection | 19 |

| Travel | Undefined | 0 |

| Other | Colonization/carriage | 11 |

| Other | Colonization/carriage and/or infection | 18 |

| Other | Infection | 113 |

| Other | Undefined | 4 |

Many comparison groups were reported (Table 4). The most common was an ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae culture compared with an ESBL-negative Enterobacteriaceae culture (n=171). Twenty articles reported two comparator groups (e.g., case-case-control studies).

| Positive outcome (e.g., cases) |

Negative outcome (e.g., controls) |

Number of articlesTable 4 footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| ESBL-positive for Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli urine culture) | ESBL-negative for the same explicitly defined Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., non-ESBL-producing E. coli urine culture)Table 4 footnote b | 171 | 45 |

| ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage positive (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli fecal sample) | Negative for same explicitly defined ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage (e.g., negative for ESBL-producing E. coli fecal sample)Table 4 footnote c | 119 | 31 |

| ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection positive (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli UTI) | Negative for same explicitly defined ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection (e.g., negative for ESBL-producing E. coli UTI)Table 4 footnote d | 34 | 9 |

| ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage and/or infection (e.g., ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage or infection) | Negative for same explicitly defined ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage and/or infection (e.g., negative for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage or infection)Table 4 footnote e | 32 | 8 |

| ESBL positive for Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae urine culture) | ESBL negative for a combination of explicitly defined Enterobacteriaceae and non-Enterobacteriaceae of the same culture (e.g., non-ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and non-ESBL-producing non-Enterobacteriaceae urine culture)Table 4 footnote f | 16 | 4 |

| ESBL positive for Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli urine culture) | ESBL negative for bacteria that was not explicitly defined of the same culture (e.g., non-ESBL-producing bacterial urine culture)Table 4 footnote g | 7 | 2 |

| Developed an ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection | Positive for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage | 6 | 2 |

| CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae | Different genotype producing Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., TEM or SHV-producing Enterobacteriaceae) | 5 | 1 |

| Positive for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli blood culture) | ESBL-negative with a different explicitly defined Enterobacteriaceae or non-Enterobacteriaceae bacteria culture (e.g., non-ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae or Pseudomonas spp. blood culture) | 5 | 1 |

| Positive for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae culture acquired in a specified setting (e.g., community-acquired E. coli UTI) | Positive for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae culture acquired in a different specified setting (e.g., hospital-acquired E. coli UTI) | 2 | 1 |

| Positive for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage in combination with an ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection | Positive for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization/carriage in combination with an infection not caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae | 2 | 1 |

| ESBL-positive for Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli urine) | ESBL-positive for Enterobacteriaceae from a different culture (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli blood) | 1 | 1 |

| ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae culture (e.g., ESBL-producing E. coli blood culture) | The same culture with any other bacteria than the compared ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae strain (i.e., cultures could be negative or positive for any bacteria blood culture except ESBL-producing E. coli) | 1 | 1 |

|

|||

Discussion

In this scoping review, we identified 381 articles reporting factors for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Most of the included articles were published in the last 10 years, likely corresponding to the urgency to understand the growing rates of human acquisition of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and the exponential growth of scientific publications generally Footnote 8Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39. It is noteworthy that most articles focused on factors related to antimicrobial use, comorbidities/symptoms, demographics and health care, and that only a small proportion of identified articles reported factors associated with animal contact, community, and food and consumption; mainly related to colonization/carriage of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Although there were fewer articles that reported these themes, they may provide important information as previous articles have suggested that animal contact, food consumption and household or community transmission may play a role in ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae exposure Footnote 11Footnote 17Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42. It is unclear whether the individual factors that were most frequently reported in these articles were in fact more often associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (i.e., had larger measures of association), whether they had been evaluated and reported more frequently than others, or whether studies evaluating these factors were better funded.

Study setting may be an explanation for the larger number of articles on antimicrobial use, comorbidities/symptoms, demographics and health care factors reported. Most articles were conducted in hospital settings and over half of the articles used secondary sources of information (e.g., medical records or databases). This setting and source combination may have been selected on account of the relative ease of accessibility to the data. Factors associated with resistant infections in hospitals are major concerns, and therefore are an important area of research. Although some factors reported from hospital settings may be connected to those in the community settings (e.g., taking medication), factors reported from hospital settings may not be representative of factors from community settings (e.g., populations, comorbidities, varying activities). Thus, the results from studies conducted in hospital settings are not generalizable to other settings.

This review identified studies where the subjects were sampled from countries with a very high human development index Footnote 33 as we were interested in factors relevant to the Canadian context. Most studies were conducted in the European Region (n=235), followed by the Western Pacific (n=78), the Americas (n=60) and the Eastern Mediterranean (n=8). Only seven studies were performed in Canada; however, a large body of literature was collected that can be used to understand the existing knowledge of factors associated with acquiring ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in similar populations. Although these countries have similarities, differences in policies and practices may limit the generalizability of the data specifically to Canada.

Several articles reported similar factors for Enterobacteriaceae infection, regardless of their AMR status, including comorbidities, demographics and health care Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 45. Factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization or infection may be related to bacterial traits rather than distinguishing between susceptible and resistant bacteria, which is important because interventions that target the pathogen, regardless of the resistance, are likely effective at reducing both resistant and susceptible strains. This highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate comparator (control group) for the intended research question and interpretation of findings. Many different outcome comparators were identified in our review. Each comparison combination provides different information that contributes to a better overall understanding of factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

This article reports the breadth of factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae reported in the literature. Many references frequently reported demographic factors (e.g., age and ethnicity) and groups that may be particularly vulnerable. While these factors cannot be modified, they can be used to identify particularly vulnerable groups for which interventions can be targeted. Other articles reported modifiable factors (e.g., food, travel, antimicrobial use), which can be targeted as interventions and potentially implemented immediately (e.g., food-related interventions), noting dependencies on feasibility and cost, whereas others may require more gradual, multi-pronged solutions (e.g., reducing comorbidities). A multidisciplinary approach to address feasible health-promoting strategies and the complex nature of AMR with multiple drivers is necessary.

Work is currently underway to better describe the factors identified in these articles. This will provide the number of factors reported per study and quantitative data reported for these factors (i.e., the strength and direction of association between the factor and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae). Further, factors from this review will be used to populate models within the iAM.AMR project Footnote 15Footnote 28 to improve our understanding of the pathways of human exposure to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. This information will help to inform which human characteristics, behaviours and actions impact the probability of becoming colonized or infected with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and to identify which factors to prioritize for interventions. This information will be valuable for understanding how to advise Canadians about mitigating their probability of acquiring resistant bacteria and reducing the negative health impacts associated with infection.

Limitations

Articles were identified from select online databases, omitting research from grey literature. This may have introduced a publishing bias, as findings that were not disseminated through peer-reviewed publications were not reviewed for inclusion (e.g., theses and dissertations, government reports) and articles with null, negative or inconclusive findings are less likely to be published Footnote 46. Language bias was a consideration as the review was constrained to English-language articles; however, the impact of this bias was likely negligible as approximately 98% of science publications are written in English Footnote 47Footnote 48.

Another limitation included single reviewer data extraction on account of resource limitations. Multiple individuals extracting study data reduces errors and misclassification bias Footnote 49. To mitigate these types of errors and to identify errors in data extraction, the authors were involved in both data collection development and analysis.

Lastly, the grouping of factors into themes evolved during data extraction. Grouping factors into themes was challenging because of differences in terminology used, the populations studied, and definitions applied. Combining data from different studies was onerous due to heterogeneity of the study data (e.g., same variable measured on different scales, missing data) Footnote 50. Terms, including carriage and colonization, were not standardized across studies and were used interchangeably; therefore, some data had to be combined (e.g., colonization and/or carriage) or captured as “unclear.”

Conclusion

This review synthesized evidence from a large collection of articles reporting factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization, carriage and/or infections in humans within very high human development index countries. Factors were reported in many different settings, age groups and organisms, and using different outcome comparison groups. This variability between studies highlighted the need for transparent or, where possible, harmonized reporting of methods to allow for appropriate interpretations and comparisons between the factors reported. Overall, studies conducted in hospital settings predominated and the most common factor themes reported were antimicrobial use, comorbidities/symptoms, demographics and health care. Articles reporting animal contact, food consumption/practices and activities in the community were not as numerous and thus limited information about these factors were identified. There is a need for more studies examining factors associated with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the community, which have been identified as being of concern Footnote 6Footnote 8.

This scoping review synthesized knowledge about potential sources and activities that affect the risk of human exposure to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Factor themes identified spanned human, animal and environmental contexts and settings support the need for a diversity of perspectives and a multisectoral approach to AMR. The results of this article will help guide recommendations to reduce the risk of acquiring ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae for Canadians, as well as other similar countries, while considering numerous sources of exposure in various settings. These results will also guide future research for activities and in settings that are understudied.

Authors' statement

- JG — Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing–review & editing

- CU — Formal analysis, writing–review & editing

- SP — Formal analysis, review & editing

- CM — Conceptualization, methodology, review & editing

- CAC — Conceptualization, methodology, review & editing

- EJP — Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, review & editing

Competing interests

JG, CU, SP, CM and CAC have no conflicts of interest to declare. EJP is (or has been in the last five years) engaged in research grants/contracts funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and the Canadian Safety and Security Program. She is currently President of the Board of Directors of the Centre for Coastal Health, member of the Board of Directors of the McEachran Institute, member of the Advisory Council for Research Directions: One Health, and a member of the Royal Society of Canada One Health Working Group. Prior to February 2019, she was employed by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Scott McEwen and Courtney Primeau for their guidance and input on this project. We would also like to thank Jacqueline Kreller-Vanderkooy (a librarian at the University of Guelph) for providing guidance during the development of the search string and search strategy for this project.

Funding

This work was supported by the following sources: the Department of Population Medicine at the University of Guelph, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarships (Master’s Program) and the University of Guelph Dean’s Tri-Council Top-up.