Rotating shift work associated with obesity in men from northeastern Ontario

Anne Grundy, PhD (1,2); Michelle Cotterchio, PhD (3,4); Victoria A. Kirsh, PhD (4); Victoria Nadalin, MA (3); Nancy Lightfoot, PhD (5); Nancy Kreiger, PhD (4,6)

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.37.8.02

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references:

1. Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CRCHUM), Montréal, Quebec, Canada

2. Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Quebec, Canada

3. Prevention and Cancer Control, Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

4. Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

5. School of Rural and Northern Health, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada

6. Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: Anne Grundy, Université de Montréal Hospital Research Centre, 850 Saint-Denis Street, 2nd Floor, Montréal, QC H2X 0A9; Tel: 514-890-8000 ext. 15921; Email: anne.grundy@umontreal.ca

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Abstract

Introduction: While some studies have suggested associations between shift work and obesity, few have been population-based or considered multiple shift schedules. Since obesity is linked with several chronic health conditions, understanding which types of shift work influence obesity is important and additional work with more detailed exposure assessment of shift work is warranted.

Methods: Using multivariate polytomous logistic regression, we investigated the associations between shift work (evening/night, rotating and other shift schedules) and overweight and obesity as measured by body mass index cross-sectionally among 1561 men. These men had previously participated as population controls in a prostate cancer case-control study conducted in northeastern Ontario from 1995 to 1999. We obtained information on work history (including shift work), height and weight from the existing self-reported questionnaire data.

Results: We observed an association for ever (vs. never) having been employed in rotating shift work for both the overweight (OR [odds ratio] = 1.34; 95% CI [confidence interval]: 1.05–1.73) and obese (OR = 1.57; 95% CI: 1.12–2.21) groups. We also observed nonsignificant associations for ever (vs. never) having been employed in permanent evening/night shifts. In addition, we found a significant trend of increased risk for both overweight and obesity with increasing duration of rotating shift work.

Conclusion: Both the positive association between rotating shift work and obesity and the suggested positive association for permanent evening/night shift work in this study are consistent with previous findings. Future population-based research that is able to build on our results while examining additional shift work characteristics will further clarify whether some shift patterns have a greater impact on obesity than others.

Keywords: shift work, obesity, men, population-based research

Highlights

- We examined the relationship between having worked at a job that included night shift work (evening/night, rotating or other shift schedules) and overweight and obesity in men living in northeastern Ontario.

- Men who had ever been employed in rotating shift work were more likely to be overweight or obese, and similar findings were suggested for men who had ever been employed in jobs involving evening/night shift work.

- We observed a significant trend of increasing risk of overweight and obesity with increasing duration of rotating shift work.

- Since obesity is linked with several chronic health conditions, understanding which types of shift work are specifically associated with obesity is important to the development of workplace policies that are best for workers’ health.

Introduction

Shift work has been identified as a risk factor for a number of chronic health conditions in which obesity is thought to play a role.Footnote 1-6 Specifically, increased risk of cardiovascular disease,Footnote 1 type II diabetes,Footnote 2 Footnote 3 metabolic syndromeFootnote 4 Footnote 5 and cancerFootnote 6 have been noted among shift workers.

Cross-sectional,Footnote 4 Footnote 7-17 cohortFootnote 18 and longitudinalFootnote 24 studies have evaluated links between shift work and obesity. Some found an increased risk of obesityFootnote 4 Footnote 7 Footnote 13-15 Footnote 17-20 Footnote 23 Footnote 26 or weight gainFootnote 9 among shift workers, while others found no association,Footnote 8-12 Footnote 16 Footnote 24 Footnote 25 results which appeared to be independent of study design. Most previous studies of shift work and obesity have been conducted in specific workplace settings, primarily restricted to individuals employed in single industries,Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 10-15 Footnote 17 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 Footnote 23 Footnote 24 Footnote 26 Footnote 27 with only a few population-based studies, especially among men.Footnote 4 Footnote 18 As a result, assessment of shift work exposure has been limited, with most studies examining only one specific shift schedule or pattern.Footnote 4 Footnote 8-17 Footnote 19-28

Furthermore, while most studies used day-only workers as a referent group,Footnote 4 Footnote 7-15 Footnote 19-23 Footnote 25 Footnote 27 others simply compared the effects of different shift schedules to one another without a truly “unexposed” group.Footnote 16 Footnote 24 Footnote 26 A need for studies with a more detailed assessment of shift work (e.g. type of shifts worked and cumulative number of years in shift work jobs) has been identified.Footnote 28 This population-based study of over 1500 men in northeastern Ontario, Canada, improves upon previous work in several ways. Specifically, it uses a detailed assessment of shift work including jobs across multiple industries with both rotating and permanent shift patterns to evaluate the relationship between shift work history and obesity among men.

Methods

Study sample

We conducted an analysis of data provided by controls who had previously participated in a prostate cancer case-control study. The original study was conducted in northeastern Ontario from 1995 to 1999Footnote 29 Footnote 30 and examined associations of occupational and other factors with prostate cancer risk. Study controls were men aged 45 to 84 years, with no history of prostate cancer, randomly selected from residential telephone listings in northeastern Ontario.Footnote 29 Footnote 30 Controls were asked to complete a mailed questionnaire, which collected information concerning a number of personal characteristics, and served as the data source for this analysis. As previously described, the response rate for controls in this study was 47.5%,Footnote 29 with a total of 1622 men available for this analysis. Ethics approval for the original study was provided by the Laurentian Hospital Research Ethics Board and approval for this new analysis was provided by the Health Sciences North Research Institute Ethics Board and the Laurentian University Research Ethics Board.

Shift work assessment

An occupational history was included in the study questionnaire. The men were asked to report all of the jobs they had held over their lifetime. Participants reported the age at which they started and ended each job, in order to calculate duration of employment for each job. Men also reported the type of work schedule (i.e. day-only, evening/night shifts, rotating shifts or other) for each job listed to characterize the history of their shift work. Shift work was characterized as ever having worked in evening/night, rotating or other types of shift work individually (“ever shift workers”). We estimated lifetime duration of rotating shift work by adding the number of years spent in rotating shifts across all jobs, with duration of work in part-time jobs divided in half.

Obesity assessment

Obesity was assessed using body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), with participants asked to self-report their height and weight five years prior to completion of the questionnaire, as well as their height in their early thirties and weight in their early thirties and fifties. BMI five years prior to study participation was estimated, as these data were originally collected for a prostate cancer case-control study,Footnote 29 in which BMI prior to cancer development among case-patients was of interest to researchers. In order to ensure data from controls was comparable to case-patients, we also assessed BMI five years prior to study participation for all controls and the controls were used in the current analysis. As such, BMIs for the time frame five years prior to study participation were used to characterize obesity in this study. Men with a BMI of less than 25 were categorized as normal weight; a BMI of 25 to less than 30 was characterized as overweight and a BMI greater than or equal to 30 as obese.Footnote 31

To reduce missing BMI data, if height five years prior to the study was missing, height in early thirties was used, if available. For men whose weight five years prior to the study was missing, weight in early fifties was used for men aged 50 to 59. (Men of other age groups whose weight was missing were excluded as there was no acceptable substitute. Men had to be at least 45 years of age to enrol in the study, and as such their weight in their early thirties was not an acceptable substitute for weight five years prior to the study.) This alternative BMI calculation was used for a total of 51 (11%) normal weight individuals, 104 (12%) overweight individuals and 34 (14%) obese participants. Sixty-one men were missing height or weight information and could not have their BMI classified.

Assessment of potential confounders

Potential confounders of the shift work–obesity relationship were age, marital status, socioeconomic status, physical activity, total energy intake (diet) and smoking status.Footnote 28 We used education and family income to capture aspects of socioeconomic status. We used general activity and occupational activity variables to characterize physical activity. For general physical activity, men reported the number of times per month they engaged in at least 20 minutes of both strenuous and moderate-intensity physical activity during four lifetime periods (teens, thirties, fifties, and five years before the study). Participants reported strenuous and moderate-intensity physical activity in separate questions, with examples of each type of activity provided. We created a physical activity index by summing the number of times men reported engaging in moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities across each of the four lifetime periods. We then created quartiles of the physical activity index, with higher values representing individuals who were more active over their lifetime.

To assess occupational physical activity, men were asked to report the usual type of activity undertaken in their job using one of four categories (sitting, light, moderate or strenuous activity), again during four lifetime periods (early twenties, early thirties, early fifties and five years prior to the study). We categorized occupational activity by the number of age periods during which men reported engaging in moderate or strenuous occupational activity: none, one, two, three or four time periods. We assessed diet two years prior to study participation using information collected in the full dietary history included in the study questionnaire, from which total energy intake was estimated in a previous analysis.Footnote 30 Total energy intake was characterized both continuously and in quartiles. We defined smoking status by history of ever having smoked filtered or nonfiltered cigarettes; men were characterized as never, former or current smokers.

Statistical analysis

We described characteristics of men classified as normal, overweight and obese using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. We also stratified descriptive characteristics by history of ever having been employed in shift work. To characterize the type of work being done by individuals in this population employed in jobs involving shift work, we described the work environment for each job reported for each of day, evening/night, rotating and other types of shift work.

We estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between shift work and overweight and obesity using multivariate polytomous logistic regression, using the normal weight group as a referent.Footnote 32 The association between ever having engaged in shift work and obesity was explored using three characterizations of ever shift work in separate statistical models. Specifically, we examined ever having performed permanent evening/night shifts, rotating shifts or other types of shift. We were only able to examine the impact of duration of shift work on rotating shift workers, since there was insufficient statistical power for the permanent evening/night shift workers. We categorized duration of shift work in three groups (> 0–14 years, 15–29 years and ≥ 30 years) to distinguish short-, medium- and long-term shift workers. These categories have been previously used in associations between shift work and cancer.Footnote 33-36

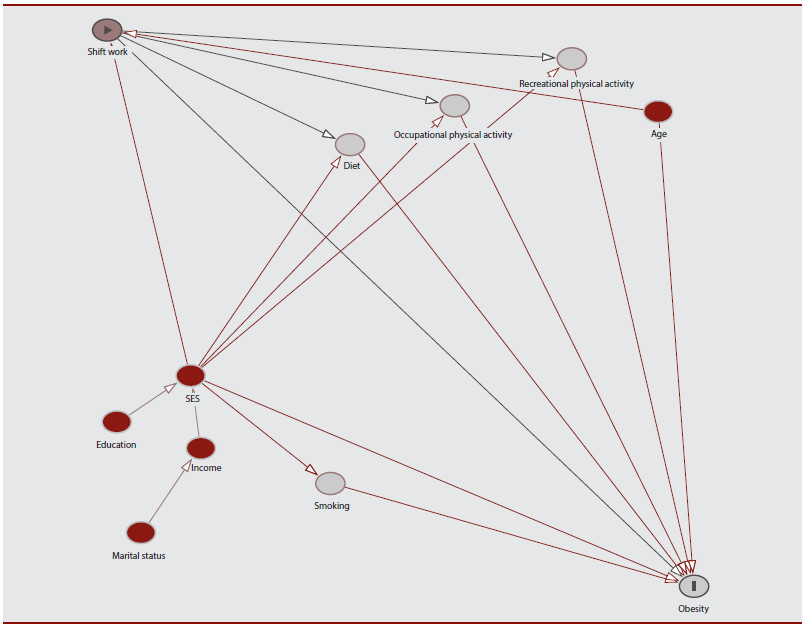

We selected confounders using a directed acyclic graph. Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) are causal diagrams that illustrate the direction of relationships between variables of interest and other unknown confounders. They have been suggested as an alternative to traditional epidemiological methods of confounder identificationFootnote 37 as they explicitly display and facilitate the causal-inference process.Footnote 38 Specifically, in contrast to statistically driven methods of model building, DAGs focus on the theoretical causal relationships between variables when identifying potential confounders.Footnote 37 They are used in epidemiology to identify a confounder set (minimally sufficient set) that will control for potential confounding between an exposure and an outcome, given the hypothesized causal relationships.Footnote 37 We used DAGitty softwareFootnote 39 Footnote * to create a DAG and identify a minimally sufficient adjustment set for the association between shift work and overweight and obesity. The DAG is shown in Figure 1; we identified a minimally sufficient adjustment set that included age and socioeconomic status, the latter as determined by education and family income, and adjusted all multivariate models for these variables. We conducted all analyses using SAS, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Figure 1 - Directed acyclic graph for the association between shift work and obesity using DAGittyFigure 1 - Footnote a

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

Figure 1 presents the directed acyclic graph illustrating the direction of relationships between shift work and variables linked to obesity. The authors identified a minimally sufficient adjustment set that included age and socioeconomic status, the latter as determined by education and family income, and adjusted all multivariate models for these variables.

Results

The proportion of men with a history of ever having been employed in any type of shift work (“ever shift workers”) who had a post-secondary or post-graduate education was lower than among those who had never been employed in any type of shift work (“never shift workers”). Similarly, a greater proportion of “ever” than “never” shift workers were also in the bottom two family income categories; were current or former smokers; and had been employed in occupations that involved moderate or strenuous physical activity during three or four lifetime periods (Table 1).

| Obesity statusTable 1 - Footnote b | Shift work history | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 457) | Overweight (n = 855) | Obese (n = 249) | Never shift workers (n = 543) | Ever shift workersTable 1 - Footnote c (n = 1079) | ||||||

| n/Mean | %/SD | n/Mean | %/SD | n/Mean | %/SD | n/Mean | %/SD | n/Mean | %/SD | |

| Age | 69.6 | 7.4 | 68.7 | 7.1 | 67.1 | 6.9 | 67.9 | 7.8 | 68.6 | 7.4 |

| Marital statusTable 1 - Footnote d | ||||||||||

| Single | 12 | 3% | 15 | 2% | 6 | 2% | 15 | 3% | 22 | 2% |

| Married/common-law | 384 | 84% | 724 | 85% | 211 | 85% | 449 | 83% | 915 | 85% |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 60 | 13% | 115 | 13% | 31 | 12% | 79 | 15% | 139 | 13% |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Elementary or less | 141 | 31% | 286 | 34% | 87 | 35% | 148 | 27% | 382 | 35% |

| High school | 200 | 44% | 405 | 48% | 121 | 49% | 224 | 41% | 523 | 48% |

| Post-secondary | 86 | 19% | 134 | 16% | 38 | 15% | 131 | 24% | 142 | 13% |

| Post-graduate | 27 | 6% | 25 | 3% | 3 | 1% | 31 | 6% | 28 | 3% |

| Family income | ||||||||||

| < $20 000 | 59 | 13% | 96 | 11% | 24 | 10% | 55 | 10% | 130 | 12% |

| $20 000–$39 999 | 147 | 32% | 278 | 33% | 81 | 33% | 155 | 29% | 362 | 34% |

| $40 000–$59 999 | 126 | 28% | 250 | 30% | 68 | 27% | 144 | 27% | 311 | 29% |

| $60 000–$79 999 | 45 | 10% | 90 | 11% | 26 | 10% | 71 | 13% | 102 | 9% |

| $80 000–$99 999 | 15 | 3% | 27 | 3% | 11 | 4% | 29 | 5% | 26 | 2% |

| ≥ $100 000 | 14 | 3% | 27 | 3% | 11 | 4% | 29 | 5% | 30 | 3% |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Never smoker | 117 | 26% | 197 | 23% | 54 | 23% | 152 | 28% | 239 | 22% |

| Former smoker | 258 | 56% | 532 | 62% | 158 | 63% | 316 | 58% | 659 | 61% |

| Current smoker | 80 | 18% | 117 | 14% | 34 | 14% | 68 | 12% | 169 | 16% |

| Physical Activity IndexTable 1 - Footnote e | ||||||||||

| < 56 | 113 | 25% | 177 | 21% | 63 | 25% | 150 | 28% | 235 | 22% |

| 56–89 | 100 | 22% | 226 | 26% | 70 | 28% | 130 | 24% | 283 | 26% |

| 90–121 | 117 | 26% | 232 | 27% | 52 | 21% | 129 | 24% | 280 | 26% |

| ≥ 122 | 127 | 28% | 220 | 26% | 64 | 26% | 134 | 25% | 281 | 26% |

| Overall occupational activityTable 1 - Footnote f | ||||||||||

| Category 4 | 38 | 8% | 79 | 9% | 19 | 8% | 54 | 10% | 84 | 8% |

| Category 3 | 158 | 35% | 344 | 40% | 100 | 40% | 162 | 30% | 448 | 42% |

| Category 2 | 84 | 19% | 179 | 21% | 58 | 23% | 87 | 16% | 253 | 23% |

| Category 1 | 59 | 13% | 90 | 11% | 30 | 12% | 59 | 11% | 125 | 12% |

| None | 118 | 26% | 163 | 19% | 42 | 17% | 181 | 33% | 169 | 16% |

| Total energy consumption (kJ/wk)—continuous | ||||||||||

| 53 941 | 17 357 | 54 356 | 19 111 | 57 966 | 20 659 | 54 427 | 18 617 | 55 030 | 19 195 | |

| Total energy consumption (kJ/wk)—categorical | ||||||||||

| ≤ 44 706 | 138 | 30% | 243 | 28% | 56 | 22% | 144 | 27% | 306 | 28% |

| 44 707–54 784 | 101 | 22% | 209 | 24% | 68 | 27% | 129 | 24% | 262 | 24% |

| 54 785–66 330 | 93 | 20% | 193 | 23% | 50 | 20% | 102 | 19% | 138 | 22% |

| ≥ 66 331 | 96 | 21% | 152 | 18% | 59 | 24% | 106 | 20% | 209 | 19% |

| Unknown | 29 | 6% | 58 | 7% | 16 | 6% | 62 | 11% | 64 | 6% |

|

||||||||||

When comparing across the categories of obesity status, a greater proportion of normal weight individuals reported having obtained a post-secondary or post-graduate education (25%) compared to overweight (19%) or obese (16%) men. Furthermore, a greater proportion of men in the overweight or obese categories reported having held jobs involving moderate or strenuous physical activity in three or four lifetime periods (overweight, 49%; obese, 48%) compared to normal weight individuals (43%). Conversely, while the proportion of men in the top two quartiles of recreational activity was similar for normal (54%) and overweight (53%) men, the proportion was slightly lower among individuals who were obese (47%). There were no major differences in total energy consumption, with 41% of individuals in the normal and overweight groups in the top two consumption quartiles compared to 44% of men in the obese group (Table 1).

The frequencies of different shift types across ten categories of work environment are shown in Table 2. Evening/night work was the least commonly reported shift schedule; restaurant/hotel work was reported by the highest proportion (11%) of men for this shift type. Rotating shift patterns were more common; for this shift type, mine (63%), factory/plant floor (49%), and laboratory work (26%) had the highest proportion of rotating shifts. Other shift schedules were most common in restaurant/hotel (37%) or vehicle work (22%).

| Shift type | Work environment | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mine (n = 790) | Factory/plant floor (n = 1426) | Laboratory (n = 73) | Vehicle (n = 730) | Restaurant/hotel (n = 107) | Warehouse floor (n = 179) | Outdoors (n = 1425) | Construction site (n = 433) | Office (n = 1370) | Other (n = 1623) | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Day | 137 | 17 | 624 | 44 | 53 | 73 | 394 | 54 | 35 | 33 | 132 | 74 | 1019 | 86 | 373 | 86 | 1177 | 86 | 1108 | 68 |

| Evening/ night | 19 | 2 | 38 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 29 | 2 | 50 | 3 |

| Rotating | 495 | 63 | 693 | 49 | 19 | 26 | 146 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 31 | 17 | 148 | 10 | 39 | 9 | 70 | 5 | 235 | 14 |

| Other | 121 | 15 | 71 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 163 | 22 | 40 | 37 | 9 | 5 | 234 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 94 | 7 | 222 | 14 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Following the exclusion of 61 men for missing BMI information, a total of 1561 men were included in the multivariate analysis. Rotating shift work was associated with both overweight (OR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.05–1.73) and obesity (OR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.12–2.21). In addition, although not statistically significant, odds ratios for both overweight (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 0.70–1.79) and obese (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 0.71–2.39) relative to normal weight individuals were elevated for evening/night shift work (Table 3). There was no association between other shift work patterns and obesity. While odds ratios were generally higher in the obese compared to the overweight group, tests for trend across categories were not significant (data not shown).

| Type of shift workTable 3 - Footnote c | Normal (n = 457) | Overweight (n = 855) |

Obese (n = 249) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ORTable 3 - Footnote d (95% CI) | n | % | ORTable 3 - Footnote b (95% CI) | ORTable 3 - Footnote e(95% CI) | n | % | ORTable 3 - Footnote b (95% CI) | ORTable 3 - Footnote e (95% CI) | |

| Evening/night shift work | 30 | 7 | 1.00 (ref) | 67 | 8 | 1.21 (0.77–1.89) | 1.12 (0.70–1.79) | 22 | 9 | 1.38 (0.78–2.45) | 1.31 (0.71–2.39) |

| Rotating shift work | 178 | 39 | 1.00 (ref) | 410 | 48 | 1.44 (1.15–1.82) | 1.34 (1.05–1.73) | 135 | 53 | 1.77 (1.30–2.42) | 1.57 (1.12–2.21) |

| Other shift work | 136 | 30 | 1.00 (ref) | 252 | 29 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | 71 | 29 | 0.94 (0.67–1.32) | 0.97 (0.67–1.41) |

|

|||||||||||

Duration of employment in rotating shift work was characterized according to one of four categories: none, > 0 to 14 years, 15 to 29 years and 30 or more years. We observed a significant association between 30 or more years of rotating shift work and being obese (OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.16–2.96). Odds ratios with obesity were elevated for > 0 to 14 and 15 to 29 years of rotating shift work and for all three duration categories and overweight (Table 4). For both the overweight (p = .03) and obese (p = .008) groups, we observed a significant trend across shift work duration categories.

| Duration of rotating shift work (years) | Normal (n = 457) | Overweight (n = 855) | Obese (n = 249) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | OR (95% CI)Table 4 - Footnote b | OR (95% CI)Table 4 - Footnote c | n | % | OR (95% CI)Table 4 - Footnote b | OR (95% CI)Table 4 - Footnote c | |

| None | 279 | 61 | 447 | 52 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 117 | 47 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| >0–14 | 74 | 16 | 172 | 20 | 1.45 (1.06–1.98) | 1.29 (0.93–1.80) | 53 | 21 | 1.71 (1.13–2.58) | 1.50 (0.96–2.35) |

| 15–29 | 42 | 9 | 87 | 10 | 1.29 (0.87–1.92) | 1.27 (0.83–1.96) | 27 | 11 | 1.53 (0.90–2.60) | 1.29 (0.72–2.29) |

| ≥ 30 | 62 | 14 | 149 | 17 | 1.50 (1.08–2.09) | 1.42 (0.99–2.03) | 52 | 21 | 2.00 (1.31–3.07) | 1.86 (1.16–2.96) |

| p-trend | .008 | .03 | < .001 | .008 | ||||||

|

||||||||||

We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding all men whose BMI was calculated using either their height in their early thirties or weight during their fifties (n = 189 individuals). These findings were very similar to those seen in the full dataset (data not shown) both for ever shift work and for duration of shift work for both evening/night and rotating shift types.

Discussion

In this study of over 1500 men, we found evidence that rotating shift work is associated with an increased risk of being overweight or obese. Permanent evening/night shift work was also associated with an increased risk, although these results were not statistically significant. Previous studies of shift work and obesity have primarily been conducted in the context of single workplaces or industries, and few have directly compared the impact of permanent and rotating shift patterns within a single study population, as was done here. Most existing studies of shift work and obesity have focussed on rotating shift patterns and, similar to our results, demonstrated significant positive associations between shift work and obesity,Footnote 7 Footnote 17 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 Footnote 22 Footnote 27 although some studies have not supported this pattern.Footnote 10 Footnote 21 Furthermore, few studies have specifically considered the effects of permanent night work. One cross-sectional study linked permanent late-night shift work with weight gain among nurses and security personnel,Footnote 9 while permanent night shifts were associated with a higher prevalence of obesity among both poultry plant workersFootnote 14 and women working in a semiconductor manufacturing factory.Footnote 15

We observed a trend of increasing risk of both overweight and obesity with increasing duration of rotating shift work. While odds ratios were elevated for all shift work durations, the association was strongest and statistically significant for 30 or more years of rotating shift work and obesity. Few earlier studies have considered duration of shift work in evaluating relationships with obesity. Among women participating in the Million Women Study, a trend of increasing obesity by duration of shift work was observed.Footnote 18 Duration of shift work was also identified as a predictor of BMI among oil and gas workersFootnote 8 and waist-hip ratio among female hospital nurses and male factory workers.Footnote 16 In a study using a categorical definition of duration similar to ours, a positive relationship with waist-hip ratio was seen for 2 to 5 years and 5 or more years of shift work, and for BMI after 5 years among male shift workers.Footnote 22 However, not all studies have shown positive associations with obesity, as another cross-sectional study of men aged 35 to 60 years found no impact of shift work duration.Footnote 7 As in our analysis, these existing studies examined the influence of shift work duration on obesity cross-sectionallyFootnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 16 Footnote 18 Footnote 22 and were unable to definitively establish a temporal relationship between shift work and obesity.

Associations between duration of shift work and obesity are of interest as obesity is a potential intermediate between shift work and other health outcomes such as cancer. Specifically, several studies examining relationships between shift work and breast cancer in women have observed an elevated breast cancer risk among long-term shift workers.Footnote 1 Footnote 40 Footnote 41 Earlier analysis of the prostate cancer case-control study that is the data source for this analysis found an association between 7 or fewer years of rotating shift work and prostate cancer risk, but no associations for longer durations,Footnote 42 while a 2012 Canadian study demonstrated an elevated risk of prostate cancer for each of three durations of shift work: less than 5 years, 5 to 10 years and 10 or more years.Footnote 43 In addition, recent results from Spain demonstrated nonsignificant increased risks of prostate cancer among both permanent and rotating night workers who had worked these shifts for 28 or more years.Footnote 44 No studies specifically examining relationships between shift work, obesity and cancer risk in a longitudinal context have been conducted.

Several mechanisms through which shift work exposure could be associated with obesity have been suggested, mainly revolving around circadian disruption. For example, metabolic efficiency is different depending on the time of day at which food is consumed and thus, differences in meal timing among individuals working at night could be a mechanism through which shift work influences obesity.Footnote 45 Sleep disturbances may also influence metabolism, and several studies have demonstrated that sleep durations are generally shorter among individuals working at night.Footnote 2 Footnote 18 Footnote 46 Footnote 47 While total energy intake was available in this study, the timing of meals and information concerning sleep patterns (such as duration) was not, thus the impact of these mechanisms could not be evaluated.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the population-based design allowing multiple patterns of shift work to be captured within a single population. Compared to previous studies conducted in single industries or workplaces that examined only one type of shift pattern,Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 10-15 Footnote 17 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 Footnote 23 Footnote 24 Footnote 26 Footnote 27 this analysis demonstrated that relationships with obesity were stronger for rotating shift work patterns than permanent evening/night shift patterns. This analysis also considered the influence of several potential confounders of shift work–obesity relationships, an improvement over previous studies for which lack of appropriate consideration of possible confounders was identified as a limitation in a 2011 review.Footnote 28 Finally, this study used a lifetime occupational history to characterize shift work, a more comprehensive method of exposure assessment than many previous studies in which only an individual’s current job or employment history with one company were considered.Footnote 7-11 Footnote 13-17 Footnote 19-25 Footnote 27

Despite these strengths, certain limitations of our study exist. Although the use of a population-based dataset allowed for a broader range of shift patterns (permanent evening/nights and rotating) to be captured within a single study than in most previous work,Footnote 7-27 detailed information concerning shift characteristics (such as specific rotation patterns, the number of consecutive nights, forward vs. backward rotation pattern) was not available. Furthermore, for our analysis, evening and night shifts were considered together, as were all types of rotating shift patterns that could include either evening or night shifts. The importance of information concerning specific features of shift work in exposure assessment was emphasized by a 2009 IARC Working Group,Footnote 48 and more work that incorporates these shift work characteristics when examining relationships with obesity is needed in the future. If different shift types produce different levels of circadian disruption then the combining of shift types, as was done in our analysis, could produce residual confounding.

Long work hours have also been associated with risk of obesity;Footnote 49 however, data concerning this issue was not available in our study. In addition, although approximately 1500 men were included in this study, the proportion exposed to evening/night shift work in each obesity group was relatively small (< 10%). Because of this small sample size, and particularly as we could not consider duration of this type of shift work, this study may have had limited power to detect real associations between permanent evening/night shift work and obesity. Future studies including a greater number of permanent evening/night shift workers will be better able to examine these relationships. In addition, there may be residual confounding by work environment if specific characteristics of certain work environments other than shift work are the true risk factors for obesity. However, given that the results of our study showing that rotating shift work increases the risk of obesity are consistent with previous work conducted in several different workplaces,Footnote 7 Footnote 17 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 Footnote 22 Footnote 27 it seems more likely that the observed shift work–obesity relationship is real.

The use of self-reported heights and weights to assess BMI presents a risk of outcome misclassification, as overestimates of height and underestimates of weight in self-reported data can lead to underestimates of BMI.Footnote 50 BMI misclassification could have reduced the precision of estimates of associations between shift work and overweight and obesity, as truly overweight or obese participants could have been included in the normal weight group. However, the proportion of men classified as overweight or obese in our study (70.7%) is similar to proportion of overweight and obese men aged 45 years and over from northeastern Ontario health units (68.0%) measured by Statistics Canada in 2000.Footnote 51

Self-report was also used for measures of diet, as well as for general and occupational physical activity, such that all three of these measures could be affected to some extent by misclassification. However, given that these measures were used descriptively in the study population but were not included in multivariate models assessing shift work–obesity associations, any misclassification is unlikely to have influenced the observed relationships.

The relatively low response rate for controls in this data set (47.5%) also presents a possible selection bias, specifically if study participation was related to both shift work history and obesity status. However, the proportion of men with a history of shift work in our study (33%) is similar to the proportion of Canadians reported to be employed in shift work in the 2005 Statistics Canada Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics,Footnote 52 which could suggest shift work was not a major determinant of study participation. While one might suspect that the true proportion of shift workers in northeastern Ontario is higher than the national average, such that shift workers are underrepresented in our study population, given that study participation did not appear to be associated with obesity status, any association between shift work and study participation is unlikely to produce a true selection bias.

Finally, as this study was conducted among men who were almost exclusively Caucasian,Footnote 30 these results may not be generalizable to other population subgroups, such as women or men of other ethnicities.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a positive association between rotating shift work and overweight and obesity and suggested a relationship for evening/night shift work. We also observed associations between increasing duration of rotating shift work and obesity, with the strongest associations for long-term rotating shift work. While a number of studies previous to this have supported a relationship between shift work and obesity,Footnote 4 Footnote 7 Footnote 13 Footnote 17-20 Footnote 26 Footnote 27 additional population-based research like ours will further clarify whether some shift patterns have a greater influence on obesity than others. As shift work is a necessary component of many occupations, understanding which shift patterns are related to health outcomes such as obesity is necessary for the development of policies on the optimal organization of shifts for workers’ health.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the original prostate cancer case-control study was provided by research grants from the National Health Research and Development Program (Project No. 6606-5574-502), The Northern Cancer Research Foundation and The Canadian Union of the Mine, Mill & Smelter Workers—Local 598. Anne Grundy was supported during this work by a postdoctoral fellowship from Cancer Care Ontario.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

NL was the principal investigator of the Men’s Health Study, the prostate cancer case-control study from which data for this analysis was drawn. Design of the shift work analysis, statistical analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript writing was performed by AG, with feedback from MC, VK, VN, NL and NK.

Footnotes

- Footnote *

-

www.dagitty.net

References

- Footnote 1

-

Wang X-S, Armstrong MEG, Cairns BJ, Key TJ, Travis RC. Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61(2):78-89.

- Footnote 2

-

Pan A, Schernhammer ES, Sun Q, Hu FB. Rotating night shift work and risk of type 2 diabetes: two prospective cohort studies in women. PLoS Med. 2011;8(12):e1001141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001141.

- Footnote 3

-

Morikawa Y, Nakagawa H, Miura K, et al. Shift work and the risk of diabetes mellitus among Japanese male factory workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31(3):179-83.

- Footnote 4

-

Karlsson B, Knutsson A, Lindahl B. Is there an association between shift work and having a metabolic syndrome? Results from a population based study of 27 485 people. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(11):747-52.

- Footnote 5

-

De Bacquer D, Van Risseghem M, Clays E, Kittel F, De Backer G, Braeckman L. Rotating shift work and the metabolic syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):848-54.

- Footnote 6

-

Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(12):1065-6.

- Footnote 7

-

Di Lorenzo L, De Pergola G, Zocchetti C, et al. Effect of shift work on body mass index: results of a study performed in 319 glucose-tolerant men working in a Southern Italian industry. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(11):1353-8.

- Footnote 8

-

Parkes KR. Shift work and age as interactive predictors of body mass index among offshore workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28(1):64-71.

- Footnote 9

-

Geliebter A, Gluck ME, Tanowitz M, Aronoff NJ, Zammit GK. Work-shift period and weight change. Nutrition. 2000 Jan;16(1):27-9.

- Footnote 10

-

Nakamura K, Shimai S, Kikuchi S, et al. Shift work and risk factors for coronary heart disease in Japanese blue-collar workers: serum lipids and anthropometric characteristics. Occup Med (Lond). 1997;47(3):142-6.

- Footnote 11

-

Ghiasvand M, Heshmat R, Golpira R, et al. Shift working and risk of lipid disorders: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2006;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-5-9.

- Footnote 12

-

Karlsson BH, Knutsson AK, Lindahl BO, Alfredsson LS. Metabolic disturbances in male workers with rotating three-shift work. Results of the WOLF study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76(6):424-30.

- Footnote 13

-

Ishizaki M, Morikawa Y, Nakagawa H, et al. The influence of work characteristics on body mass index and waist to hip ratio in Japanese employees. Ind Health. 2004;42(1):41-9.

- Footnote 14

-

Macagnan J, Pattussi MP, Canuto R, Henn RL, Fassa AG, Olinto MT. Impact of nightshift work on overweight and abdominal obesity among workers of a poultry processing plant in southern Brazil. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(3):336-43.

- Footnote 15

-

Chen JD, Lin YC, Hsiao ST. Obesity and high blood pressure of 12-hour night shift female clean-room workers. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27(2):334-44.

- Footnote 16

-

Ha M, Park JP. Shiftwork and metabolic risk factors of cardiovascular disease. J Occup Health. 2005;47:89-95.

- Footnote 17

-

Manenschijn L, van Kruysbergen RGPM, de Jong FH, Koper JW, van Rossum EFC. Shift work at young age is associated with elevated long-term cortisol levels and body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(11):E1862-E1865.

- Footnote 18

-

Wang X-S, Travis RC, Reeves G, et al. Characteristics of the Million Women Study participants who have and have not worked at night. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38(6):590-9.

- Footnote 19

-

Suwazono Y, Dochi M, Sakata K, et al. A longitudinal study on the effect of shift work on weight gain in male Japanese workers. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(8):1887-93.

- Footnote 20

-

Morikawa Y, Nakagawa H, Miura K, et al. Effect of shift work on body mass index and metabolic parameters. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007;33(1):45-50.

- Footnote 21

-

van Amelsvoort LG, Schouten EG, Kok FJ. Impact of one year of shift work on cardiovascular disease risk factors. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(7):699-706.

- Footnote 22

-

van Amelsvoort L, Schouten EG, Kok FJ. Duration of shiftwork related to body mass index and waist to hip ratio. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(9):973-8.

- Footnote 23

-

Sakata K, Suwazono Y, Harada H, Okubo Y, Kobayashi E, Nogawa K. The relationship between shift work and the onset of hypertension in male Japanese workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(9):1002-6.

- Footnote 24

-

Yamada Y, Kameda M, Noborisaka Y. Excessive fatigue and weight gain in cleanroom workers after changing from an 8-hour to a 12-hour shift. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2001;27(5):318-26.

- Footnote 25

-

Watari M, Uetani M, Suwazono Y, Kobayashi E, Kinouchi N, Nogawa K. A longitudinal study of the influence of smoking on the onset of obesity at a telecommunications company in Japan. Prev Med (Baltim). 2006;43(2):107-12.

- Footnote 26

-

Biggi N, Consonni D, Galluzzo V, Sogliani M, Costa G. Metabolic syndrome in permanent night workers. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25(2):443-54.

- Footnote 27

-

Kubo T, Oyama I, Nakamura T, et al. Retrospective cohort study of the risk of obesity among shift workers: findings from the Industry-based Shift Workers’ Health study, Japan. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(5):327-31.

- Footnote 28

-

van Drongelen A, Boot CRL, Merkus SL, Smid T, van der Beek AJ. The effects of shift work on body weight change - a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(4):263-75.

- Footnote 29

-

Lightfoot N, Conlon M, Kreiger N, Sass-Kortsak A, Purdham J, Darlington G. Medical history, sexual, and maturational factors and prostate cancer risk. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(9):655-62.

- Footnote 30

-

Darlington GA, Kreiger N, Lightfoot N, Purdham J, Sass-Kortsak A. Prostate cancer risk and diet, recreational physical activity and cigarette smoking. Chronic Dis Can. 2007;27(4):145-53.

- Footnote 31

-

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation, Geneva, 3-5 Jun 1997. Geneva; 1998. 252 p.

- Footnote 32

-

Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Special topics. In: Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. Toronto (ON): John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2000. p. 260-352.

- Footnote 33

-

Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women participating in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(20):1563-8.

- Footnote 34

-

Lie J-AS, Kjuus H, Zienolddiny S, Haugen A, Stevens RG, Kjærheim K. Night work and breast cancer risk among Norwegian nurses: assessment by different exposure metrics. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(11):1272-9.

- Footnote 35

-

Hansen J, Lassen CF. Nested case-control study of night shift work and breast cancer risk among women in the Danish military. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(8):551-6. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100240.

- Footnote 36

-

Grundy A, Richardson H, Burstyn I, et al. Increased risk of breast cancer associated with long-term shift work in Canada. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70(12):831-8.

- Footnote 37

-

Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37-48.

- Footnote 38

-

Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology beyond the basics. 3rd ed. Burlington (MA): Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2014. p. 162-163.

- Footnote 39

-

Textor J, Hardt J, Knüppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology. 2011;22(5):745.

- Footnote 40

-

Erren TC, Pape HG, Reiter RJ, Piekarski C. Chronodisruption and cancer. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95(5):367-82.

- Footnote 41

-

Wang F, Yeung KL, Chan WC, et al. A meta-analysis on dose-response relationship between night shift work and the risk of breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2724-32.

- Footnote 42

-

Conlon M, Lightfoot N, Kreiger N. Rotating shift work and risk of prostate cancer. Epidemiology. 2007;18(1):182-3.

- Footnote 43

-

Parent M-É, El-Zein M, Rousseau M-C, Pintos J, Siemiatycki J. Night work and the risk of cancer among men. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(9):751-9.

- Footnote 44

-

Papantoniou K, Castaño-Vinyals G, Espinosa A, et al. Night shift work, chronotype and prostate cancer risk in the MCC-Spain case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(5):1147-57.

- Footnote 45

-

Antunes LC, Levandovski R, Dantas G, Caumo W, Hidalgo MP. Obesity and shift work: chronobiological aspects. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(1):155-68.

- Footnote 46

-

Grundy A, Sanchez M, Richardson H, et al. Light intensity exposure, sleep duration, physical activity, and biomarkers of melatonin among rotating shift nurses. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(7):1443-61.

- Footnote 47

-

Grundy A, Tranmer J, Richardson H, Graham CH, Aronson KJ. The influence of light at night exposure on melatonin levels among Canadian rotating shift nurses. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(11):2404-12.

- Footnote 48

-

Stevens RG, Hansen J, Costa G, et al. Considerations of circadian impact for defining “shift work” in cancer studies: IARC Working Group Report. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(2):154-62.

- Footnote 49

-

Luckhaupt SE, Cohen MA, Li J, Calvert GM. Prevalence of obesity among U.S. workers and associations with occupational factors. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3):237-48.

- Footnote 50

-

Shields M, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M. Estimates of obesity based on self-report versus direct measures. Health Rep. 2008;19(2):61-76.

- Footnote 51

-

Statistics Canada. CANSIM database: Table 105-0007: Body mass index (BMI), by age group and sex, household population aged 18 and over excluding pregnant women, Canada, provinces, territories, health regions (January 2000 boundaries) and peer groups, every 2 years [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; [cited 2014 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim

- Footnote 52

-

Williams C. Work-life balance of shift workers. Perspect Labour Income. 2008;75(5):5-16.