Youth self-report of child maltreatment in representative surveys: a systematic review

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Jessica LaurinFootnote *, MA; Caroline WallaceFootnote *, BSc; Jasminka Draca, BHSc; Sarah Aterman, BAH; Lil Tonmyr, PhD

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.2.01

This evidence synthesis has been peer reviewed.

Author references:

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Endnote *

-

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence: Lil Tonmyr, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Ave, 7th floor, Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 613-240-6334; Email: Lil.Tonmyr@canada.ca

Abstract

Introduction: This systematic review identified population-representative youth surveys containing questions on self-reported child maltreatment. Data quality and ethical issues pertinent to maltreatment data collection were also examined.

Methods: A search was conducted of relevant online databases for articles published from January 2000 through March 2016 reporting on population-representative data measuring child maltreatment. Inclusion criteria were established a priori; two reviewers independently assessed articles to ensure that the criteria were met and to verify the accuracy of extracted information.

Results: A total of 73 articles reporting on 71 surveys met the inclusion criteria. A variety of strategies to ensure accurate information and to mitigate survey participants' distress were reported.

Conclusion: The extent to which efforts have been undertaken to measure the prevalence of child maltreatment reflects its perceived importance across the world. Data on child maltreatment can be effectively collected from youth, although our knowledge of best practices related to ethics and data quality is incomplete.

Keywords: abuse, neglect, violence, data quality, ethics, adolescence, teenager, systematic review

Highlights

- Data on child maltreatment can be collected responsibly and ethically from youth in a way that protects their health and well-being.

- Youth rarely expressed concerns about answering child maltreatment questions on self-report surveys.

- No nationally representative self-report survey focussed on Canadian youth that includes child maltreatment variables was identified from our database search.

- Few reliable and valid self-reported measures of child maltreatment currently exist.

Introduction

The consequences of child maltreatment—a public health issue that poses unique challenges to quantify and study—extend well beyond the immediate harm inflicted. For example, a history of child maltreatment has been shown to interfere with adolescent development and to raise the risk of some of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality.Footnote 1 These include alcohol-related injury, drug use, self-harming behaviour, suicide and exposure to violence.Footnote 2,Footnote 3,Footnote 4,Footnote 5

A growing body of research is aimed at estimating the extent of child maltreatment, and understanding the dynamics and mechanics of its association with health outcomes.Footnote 6 Population-representative surveys provide the opportunity to quantify child maltreatment prevalence and to assess its risk in relation to other health-related and social conditions. Of course, in surveys that address a broad range of health-related content, space limitations and competing interests challenge the inclusion of child maltreatment measures. However, the potential contribution of such surveys in improving our understanding of the prevalence, risk factors and impact of child maltreatment is becoming increasingly appreciated—both in Canada and elsewhere.Footnote 7 Population-based data from other countries provide the basis for international comparisons, from which the influence of cultural, social and policy practices on any differences observed can be considered.Footnote 8,Footnote 9

The ethical aspects of child maltreatment survey research are crucial. The sensitive nature of the subject matter and the consequential risk of emotional distress to respondents call for measures to protect confidentiality, administer questions with appropriate sensitivity, obtain informed consent, and potentially provide follow-up interventions.Footnote 10 Procedures to address such matters should be clearly delineated, and included as an elemental component of any survey or research report.

Quality of data is an important consideration and should be evaluated in any survey-based research on child maltreatment. Various factors influence the quality of information a respondent provides, such as age and developmental stage. Surveying young people about experiences of child maltreatment has the advantage of being relatively recent to the exposure, so recall bias is likely lower than it would be in a survey of adults. The reliability of self-reported information from adolescents is greater than that from younger children, by virtue of their more advanced cognitive development.Footnote 11 Specifically, research suggests that children under the age of 10 years may not be reliable respondents for a survey on experiences of maltreatment.Footnote 12 Other potential impediments to the disclosure of accurate information include distress, discomfort and embarrassment generated by the memory of events.Footnote 13,Footnote 14,Footnote 15,Footnote 16

A review article published in 2000 addressed methodological and ethical considerations in asking children about their exposure to physical and sexual abuse.Footnote 17 The authors identified 14 self-report studies that garnered information directly from children; the approaches used to elicit information varied greatly.Footnote 17 While the review provides much worthwhile information, it was limited to surveys conducted before 1999; the surveys focussed on physical and sexual abuse and were not representative of the general population. The authors noted considerable variation in data collection methods, wording and number of maltreatment questions as well as consent procedures. Consequently, the estimates of physical and sexual abuse varied considerably.

This systematic review is aimed at increasing our understanding of child maltreatment data captured in self-reported surveys with youth. The specific objectives are to (1) identify representative surveys that have collected data from youth on child maltreatment and factors influencing prevalence (thus not clinical samples); (2) examine the quality of methods used to measure child maltreatment; and (3) assess practices and procedures undertaken to address ethical issues.

Methods

This systematic review was done according to the PRISMA guidelines.Footnote 18 (Protocol is available upon request from the corresponding author).

Identification (search strategy)

A search for peer-reviewed articles published from January 2000 through March 2016 was conducted in the following online databases: Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, Global Health, Social Policy and Practice, ERIC, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and ProQuest Public Health. Search terms used included: youth, adolescent, young adult, child, abuse, maltreatment, violence, neglect, assault, rape, representative, national, and school surveys. The complete search strings employed are available upon request from the corresponding author. In addition, the reference lists of included articles were examined to identify additional articles for potential inclusion as well as discussions with experts.

The following were the criteria for inclusion of articles in the review:

- published in English;

- primary study (i.e. not review or editorial);

- data collected after 1999;

- data sources limited to school or representative population-based surveys (the latter defined as those which were described that way by the authors of the articles and/or had been sampled and weighted in order to accurately reflect the members of the entire population);

- cross-sectional design;

- age range of respondents was 10 to 18 years (core age group); in some cases, age ranged up to 24 years;

- victim's age at time of exposure to maltreatment was under 18 years;

- reported perpetrator of maltreatment was a parent or other caregiver (except for sexual abuse, for which the perpetrator could be anyone, however articles were still not included if they focused on peer or online victimization);

- analysis was conducted using the entire sample of the specified age group (ages 10 to 18).

It should be noted that we limited the inclusion to cross-sectional studies to ensure the inclusion of the largest numbers of surveys. In addition, since the primary purpose of this article is not to determine associations but instead the feasibility of collecting child maltreatment data from youth to estimate prevalence, cross-sectional studies are appropriate. The benefit of including longitudinal studies would be limited, considering that child maltreatment questions are rarely asked in the first wave of a longitudinal study but rather in the later waves where attrition may be an issue.Footnote 19,Footnote 20

Screening/eligibility (selection process)

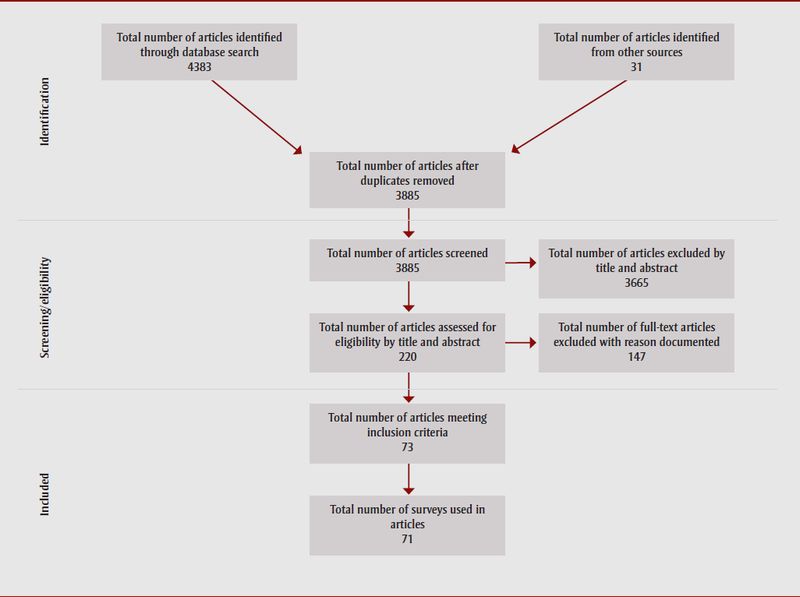

Figure 1 shows the process of selecting the articles included in this study. The database search identified 4383 articles; expert consultation and search of reference lists identified another 31 articles. Removing duplicates yielded 3885 articles, and screening by titles and abstracts led to 220 articles to be fully assessed. To these articles, the inclusion criteria noted above were applied by two reviewers independently (J.L., L.T.). The percentage agreement between the coder pairs was 97.9% for titles and abstracts. Articles were excluded when the articles addressed adults' retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment, substance abuse, non-representative samples, newspaper articles, conference abstracts, commentaries, and letters to the editor. Each reviewer also catalogued the reported prevalence of maltreatment by type. Although specific definitions of child maltreatment varied somewhat among the articles, they were conceptually similar enough that the Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) classifications could be applied such as emotional maltreatment (EM), neglect (NG), exposure to intimate partner violence (EIPV), physical and sexual abuse (PA and SA)Footnote 21 (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow of information through the different phases of the review

Figure 1: Flow of information through the different phases of the review - Text Description

This figure shows the process of selecting the articles included in this study. The database search identified 4383 articles; expert consultation and search of reference lists identified another 31 articles. Removing duplicates yielded 3885 articles, and screening by titles and abstracts led to 220 articles to be fully assessed. Of these, 73 met the inclusion criteria, representing 71 surveys.

| Types of maltreatment | Forms of child maltreatment | Questions used to measure child maltreatment |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | Kissing, caressing, fondling and oral sex | How many times has another person touched, grabbed, pinched or brushed against you in a sexual way (which you did not want)?Footnote 22 |

| Students were asked by their parents to touch the latter's sex organs, or if their own sex organs have been touched by their parents.Footnote 23 | ||

| Episodes of unwanted oral sex.Footnote 4 | ||

| Attempted rape and rape | Attempts intercourse, completed intercourse and attempts at anal intercourse.Footnote 24 | |

| We define [rape] as someone either having sexual intercourse with you or penetrating your body with a finger or object when you did not want them to, either whether by threatening you, by using force or when you were so small that you didn't know what was happening.Footnote 25 | ||

| Somebody tried to undress you in order to have sex with you, had vaginal intercourse [against your will].Footnote 26 | ||

| Exposure to pornography, masturbation, flashing | Did anyone show you pornographic material?Footnote 27 | |

| Somebody exposed himself/herself indecently to you [against your will].Footnote 26 | ||

| Did anyone make you look at their private parts by using force or surprise, or by "flashing" you?Footnote 12 | ||

| Verbal sexual abuse | How many times have you had unwanted sexual comments or jokes directed at you?Footnote 22 | |

| Did anyone hurt your feelings by saying or writing something sexual about your body?Footnote 12 | ||

| Online victimization | Did anyone on the Internet ever ask you sexual questions about (himself/herself/yourself) or try to get you to talk online about sex when you did not want to talk about those things?Footnote 28 | |

| Nude photograph(s)/video(s) being uploaded on the Internet against your will.Footnote 29 | ||

| Commercial sex | Have you ever experienced that the person/s you met [online] gave you money or a gift in order to have sex with you?Footnote 26 | |

| To be engaged in transactional sex.Footnote 30 | ||

| Self-defined | Have you ever been sexually abused?Footnote 1 | |

| Physical abuse | Corporal punishment/physical punishment | Your parents spank you on the bottom with their bare hands, hit you on the bottom with something like a belt, ruler, a tick, sweeper or some other hard object, slap you on the hand, arm or leg, pinch you or shake/push you?Footnote 31 |

| Severe physical punishment resulting in bruises or other forms of injuries.Footnote 32 | ||

| Acts traditionally seen as forms of corporal punishment: hair pulling, whipping, smacking.Footnote 33 | ||

| Slapped/hit with hand or hard object, punched, beaten | Physical maltreatment and severe physical maltreatment like slapping, hitting [...] and [...] beating.Footnote 34 | |

| Being beaten [...] by a family member.Footnote 35 | ||

| Thrown, pushed, knocked down, shaken, kicked | Has any adult ever [...] thrown something at you? (followed by question to specify the caregiver).Footnote 36 | |

| Being thrown across the room or against the wall, car, floor or other hard surface by an adult in charge, so that [you] were hurt pretty badly.Footnote 4 | ||

| Burned, scalded, choked, head held under water, tied up | "Severe physical maltreatment such as [...] burning."Footnote 34 | |

| Being grabbed around the neck or choked by an adult in charge.Footnote 4 | ||

| Your parents grab you around the neck and choke you, burn or scald you on purpose.Footnote 31 | ||

| Used weapon against | Has any adult [...]threatened you with a weapon, such as a knife, stick, a gun?Footnote 36 | |

| Attacked or threatened with a gun, knife, other weapon or other object?Footnote 4 | ||

| Self-defined | Having experienced physical violence or having experienced severe physical violence.Footnote 15 | |

| Emotional maltreatment | Verbal abuse, belittling | An adult made child scared or feel really bad by name calling, saying mean things.Footnote 1,Footnote 13 |

| Did you get scared or feel really bad because grown-ups in your life called you names, said mean things to you?Footnote 37 | ||

| Terrorized, threatened | Threatening to use a gun or knife.Footnote 38 | |

| Your parents threaten to spank or hit you but did not actually do it.Footnote 23 | ||

| Inadequate nurturing/affection | Not talking to the child.Footnote 39 | |

| Did you get scared or feel really bad because grown-ups in your life [...] say they didn't want you?Footnote 37 | ||

| Isolated/confinement | Isolated, confined in a dark room.Footnote 32 | |

| Neglect | Supervisory | Having inadequate supervision and being required to do age-inappropriate chores.Footnote 40 |

| Physical | When someone is neglected it means that the grown-up in their life did not take care of them the way they should [...] [by] make[ing] sure they have a safe place to stay.Footnote 37 | |

| Not receiving adequate food or clothing.Footnote 40 | ||

| Medical | When someone is neglected it means that the grown-up in their life did not take care of them the way they should [...] [by] taking them to the doctor when they are sick.Footnote 37 | |

| Exposure to intimate partner violence | Physical abuse | The young person witnessed his/her parents physically abusing each other.Footnote 41 |

| Adolescent observed parents punched, hit or beat up one another, choked one another, hit one another with an object. | ||

| Emotional maltreatment | Asked whether if they had ever [...] witnessed severe arguments between their parents.Footnote 2 | |

| Adolescent observed parents [...] threatening one another with gun, knife or other weapon.Footnote 4 |

We modified a coding key previously used in assessing adults' retrospective exposure to childhood maltreatment.Footnote 6 Reliability and validity of the maltreatment measures were noted when reported. Documentation of procedures related to ethics focused on any steps taken to protect confidentiality, offer respondents support, or ease their distress during/following the survey (see Table 2). Information related to survey administration and measures to evaluate data quality were collected from the articles. As well, external sources (e.g. articles or websites) cited in the articles were consulted for information regarding validity and reliability of child maltreatment measures; in some cases, these sources also provided insights into how maltreatment was conceptualized for a survey, or clarified survey procedures. When information in an article included in the review was inconsistent with that provided in an external source, the former took precedence; if information in articles selected for review and pertaining to the same survey conflicted, the article more closely addressing the objectives of the study was used.

As a final step, to verify that the selected articles met the inclusion criteria and to ensure the accuracy of all extracted information, the articles were assessed by two additional reviewers (C.W., S.A., or J.D.); any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

| Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Approaches to increase comfort | Assent: Participants who are legally too young to give informed consent, express willingness to participate in research, since they are old enough to understand the purpose of the research. |

| Consent: Voluntary agreement of an individual, or his or her authorized representative, who has legal capacity to give consent. | |

| Active consent: Parent or legal guardian is required to sign and return a form if they approve their child's participation. | |

| Passive consent: Parent or legal guardian is required to notify the school or researchers if they refuse to allow their child's participation in the research. | |

| Confidentiality: Measures undertaken to protect secrecy after the data were collected. | |

| Privacy: Measures taken to ensure respondent privacy during data collection. | |

| Anonymity: No identifying information was collected. | |

| Safe settings: The presence of reassuring figures such as teachers and nurses, and also environmental features to maximize the participant's comfort. | |

| Voluntary: The choice of participating in the study was left to the participant. | |

| Withdraw: Participants were notified they could terminate the survey at any time during data collection. | |

| Approaches to increase response rate | Incentive: Material reward offered to participate in the study. |

| Time to complete questionnaire: Time needed to finish survey was recorded. | |

| Call-backs: Participants unavailable at the time of data collection were contacted later and given a chance to participate. | |

Results

From the 3885 articles identified in the online search, 220 were screened in according to the abstract and title. Of these, 73 met the inclusion criteria, representing 71 surveys. Table 3 describes the characteristics of each sample, survey methodology, measures of child maltreatment, reliability and validity, response rates and any steps taken to enhance the response rate, approaches and protocols designed to comfort or reduce the distress of participants, and types of child maltreatment. Schools were most often the place of data collection. Most data were collected via self-administered questionnaire, data were also provided by face-to-face and telephone interviews independent of location. Eleven measures were used and often modified from the original iteration. The Juvenile Victimisation Questionnaire (JVQ) was used most often (eight times), followed by different versions of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (six times) and the International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect child abuse screening tool—Child (ICAST-CH) (four times). Thirty-seven articles did not provide any information on the specific measures used. In addition, few articles provided information regarding the reliability and validity of measures used. Respondents' response rates ranged from 40.4% to 99.9%. The majority of articles mentioned approaches taken to comfort respondents, although specific information on procedures to reduce distress was scarce.

| Country | References | Survey name and year | Method of data collection | Sample characteristics | Child maltreatment measures and reliability and/or validity | Response rate | Approaches | Procedures to deal with participant distress | Child maltreatment types | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to increase response rate | to increase comfort | SA | PA | EM | NG | EIPV | |||||||||||||||||

| Incentive | Time to complete questionnaire | Call-back | Assent | Consent | Confidentiality | Privacy | Anonymity | Safe settings | Voluntary | Withdraw | |||||||||||||

| Brazil |

Horta et al., 2014Footnote 42 Malta et al., 2014Footnote 43 |

National Adolescent School-based Health Survey [PENSE], 2012 | Self-administered questionnaire | 109 104 students, grade 9 | Table 3 footnote — | Student: 83% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Canada |

Saewyc & Tonkin, 2008Footnote 1 Tonkin et al., 2004Footnote 44 Tonkin, 2005Footnote 45 Saewyc et al., 2006Footnote 46 |

British Columbia Adolescent Health Survey (BC AHS), 2003 | Self-administered questionnaire | ≈ 30 500 students grade 7–12 | Table 3 footnote — | School: 76.3% | Table 3 footnote — | < 45 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services; gave sensitivity training to interviewers. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

Saewyc & Chen, 2013Footnote 22 Saewyc &Green, 2009Footnote 47 |

BC AHS, 2008 | Self-administered questionnaire | 29 315 students age 12–19 | Table 3 footnote — |

School: 84.7% Student: 66% |

Table 3 footnote — | < 45 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y/P | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services; gave sensitivity training to interviewers. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Cyr et al., 2013Footnote 37 | Quebec, 2009 | Telephone interview | 1400 youths age 12–17 | JVQ (adolescent version) | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 23 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| China | Lau et al., 2005Footnote 48 | Survey of Drug Use Among Students, 2000 | Self-administered questionnaire | 93 060 students age 12–19 | Table 3 footnote — | Student: 87.3% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chan et al., 2013Footnote 29 | 2009-2010 | Self-administered questionnaire | 18 341 students age 15–17 in 6 Chinese cities | JVQ α 0.97 (modified SA) |

Student: 95.8% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Provided respondents with information of support services; gave sensitivity training to interviewers. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Chan, 2011Footnote 34 | 2004 | Face-to-face interview | 1094 Chinese children age 12–17 |

CTS

CTSPC

|

Student: 70.0% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y/P | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

|

Leung et al., 2008Footnote 31 Wong et al., 2009Footnote 23 Tang, 1994 in Tang, 2006Footnote 49 |

2005 | Self-administered questionnaire | 6593 students age 12–16 | CTSPC α 0.70–0.86 |

School: 89.0% Student: 99.7% | Table 3 footnote — | 30 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | |

| Croatia | Aberle et al., 2007Footnote 32 | 2005 | Self-administered questionnaire | 2140 students age 14 and 18 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 45 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A |

| Ajdukovic et al., 2013Footnote 50 | 2011 | Self-administered questionnaire | 3175 students age 11, 13 and 16 | ICAST-CH modified SA: α 0.68 |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 45 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote •,Table 3 footnote a | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information and telephone numbers of appropriate support services. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | |

| Denmark | Ellonen et al., 2011Footnote 33 | Danish Youth Health Survey, 2008 | Self-administered questionnaire | 3943 students age 15–16 | Danish CTS | School: 35.0% Student: 82.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Helweg-Larsen & Larsen, 2006Footnote 24 Helweg-Larsen et al., 2011Footnote 51 Frederiksen et al., 2008Footnote 52 |

2002 | Self-administered questionnaire | 6203 students age 15–16 | Table 3 footnote — | School: 56.0% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Van Gastel et al., 2013Footnote 53 | Public Health Service School, 2007 | Self-administered questionnaire | 10 324 students age 11–16 | Table 3 footnote — | School: 71.0% Student: 84.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Finland | Ellonen et al., 2011Footnote 33 | The Finnish Child Victim Survey, 2008 | Self-administered questionnaire | 5762 students age 15–16 | Finnish CTS | School: 88.0% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Lepistö et al., 2010Footnote 38 Sariola & Uutela, 1992Footnote 54 |

2007 | Self-administered questionnaire | 1393 students age 14–17 | Table 3 footnote — | Student: 78.0% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Ghana | Ohene et al., 2015Footnote 55 WHO, 2017Footnote 56 |

Ghana Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS), 2012 | Self-administered questionnaire | 1984 senior school students | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Germany | Bussmann, 2004Footnote 39 | 2002 | Face-to-face interview | 2000 youths age 12–18 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Greece | Fotiou et al., 2014Footnote 57 | Greek Nationwide School Survey on Substance Use, 2011 | Self-administered questionnaire | 24 006 students age 15–19 | N/A | School: 91.0% Student: 86.4% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A |

| Haiti | Flynn-O'Brien et al., 2016Footnote 58 | Violence Against Children Survey, 2012 | Face-to-face interview | 2916 youths age 13–24 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of appropriate support services; alerted appropriate authorities. | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Iceland | Asgeirsdottir et al., 2011Footnote 2 | 2004 | Self-administered questionnaire | 9085 students age 16–19 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| India | Patel & Andrew, 2001Footnote 59 | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), 2000 | Self-administered questionnaire | 811 students grade 11 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 90 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Iran | Mahram et al., 2013Footnote 60 | 2011 | Self-administered questionnaire | 1028 students age 9–13 | α 0.83–0.98 | Table 3 footnote — | Gift | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A |

| Kenya | Seedat et al., 2004Footnote 35 | 2000 | Self-administered questionnaire | 901 students grade 10 | LEQAV | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 45–60 min | Table 3 footnote — | P | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Okech, 2012Footnote 61 | 2009-2010 | Self-administered questionnaire | 430 students age 10–16 | My Worst Experiences Scale | Student: 71.6% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Y | P | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Mexico | Borges et al., 2008Footnote 25 | Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey, 2005 | Face-to-face interview | 3005 youths age 12–17 | Table 3 footnote — | Youth: 71% | Table 3 footnote — | 150 min | Table 3 footnote — | Y | P | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Pineda-Lucatero et al., 2009Footnote 27 | 2002 | Self-administered questionnaire | 1067 students age 11–20 | Table 3 footnote — | Student: 89.1% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y,P,T,S | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Alerted appropriate authorities. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Frias & Erviti, 2014Footnote 62 | National Survey on Exclusion, Intolerance and Violence in Public High School Level Education, 2007 | Self-administered questionnaire | 13 440 students age 15–18 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Malaysia | Ahmad et al., 2014Footnote 63 | Malaysia Global School-Based Student Health Survey-2012 | Self-administered questionnaire | 25 174 students age 12–17 | N/A | Student: 99.1% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A |

| Ahmed et al., 2015Footnote 64 | 2011 | Self-administered questionnaire | 3509 students age 10–12 | ICAST-CH: Child Exposure to Domestic Violence Scale | Student: 88.9% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | S/P | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Netherlands | Klein et al., 2013Footnote 65 | Questionnaire on experience and events in high school students in Curaçao | Self-administered questionnaire | 545 students age 11–17 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 45 min | N/A | N/A | P | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A |

| New Zealand | Denny et al., 2011Footnote 66 Fleming et al., 2007Footnote 67 Adolescent Health Research Group, 2008Footnote 68 |

Youth'01 and Youth'07 | Self-administered questionnaire | 2001: 9699 students age 13–17

2007: 9107 students age 13–18 |

Table 3 footnote — | School: 2001: 86.0% 2007: 84.0% Student: 2001: 64.0% 2007: 62.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | S/P/Y | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Peru | Fry et al., 2016Footnote 69 | National Survey on Social Relations, 2013 | Face-to-face interview | 1498 youths age 12–17 | Table 3 footnote — | Youth: 99.9% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Alerted appropriate authorities; gave sensitivity training to interviewers; provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Saudi Arabia | Al-Quaiz & Raheel, 2009Footnote 70 | 2008 | Self-administered questionnaire | 419 female students age 11–21 | Table 3 footnote — | Student 80.0–90.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | 15 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Al-Eissa et al., 2016Footnote 71 ISPCAN, no dateFootnote 72 |

2012 | Self-administered questionnaire | 16 939 students age 15–19 | ICAST-CH α 0.69–0.86 |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Y | P | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Gave sensitivity training to interviewers; provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Sri Lanka | Rajindrajith et al., 2014Footnote 73 | N/A | Self-administered questionnaire | 1792 youths age 13–18 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A |

| South Africa | Seedat et al., 2004Footnote 35 | 2000 | Self-administered questionnaire | 1140 students grade 10 | LEQAV | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | 45–60 min | Table 3 footnote — | P | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

| Andersson & Ho-Foster, 2008Footnote 74 | 2002 | Self-administered questionnaire | 126 696 male students age 10–19 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Pettifor et al., 2005Footnote 30 | National Household Survey, 2003 | Face-to-face interview | 11 904 youths age 15–24 | Table 3 footnote — | Youth: 77.2% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Waller et al., 2014Footnote 75 Young Carers Project South Africa, 2016Footnote 76 |

Teen Talk 2010-2011 | Self-administered questionnaire | 3515 youths age 10–17 | UNICEF Scales for Sub-Saharan Africa: Child Exposure to Community Violence Checklist | Youth: 97.2% | Refreshment | 40–60 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote •,Table 3 footnote a | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Alerted appropriate authorities. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Swaziland | Breiding et al., 2013Footnote 36 | 2007 | Face-to-face interview | 1292 females age 13–24 | Table 3 footnote — | Youth: 96.3% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Provided respondents with information of support services; gave sensitivity training to interviewers. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sweden | Priebe & Svedin, 2012Footnote 26 Mossige et al., 2007Footnote 77 |

2009 | Self-administered questionnaire | 3432 students age 18 | Table 3 footnote — | School: 60.5% | School compensated | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Taiwan | Yen et al., 2008Footnote 78 | Project for Health of Adolescents, 2003 | Self-administered questionnaire | 1684 students age 13–18 | Abuse Assessment Screen Questionnaire | Student: 81.0% | Gift | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Y | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Turkey | Sofuglu et al., 2014Footnote 79 | 2012 | Self-administered questionnaire | 7540 students age 11, 13 and 16 | ICAST-CH EM: α 0.86; PA: 0.86; NG: 0.81 |

Student: 85.3% | Table 3 footnote — | 45 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • |

| UK | Jackson et al., 2016Footnote 80 | N/A | Self-administered questionnaire | 730 students age 13-16 | Modified JVQ α 0.51 JVQ correlated to TSC r = 0.29–0.37, p < 0.01 |

School: 22.0% Student: 52.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Alerted appropriate authorities; followed up with respondents who disclosed sensitive information. | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Radford et al., 2013Footnote 81 | 2009 | Self-administered questionnaire | 2275 youths age 11–17 | Modified JVQ | Youth: 64% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote •,Table 3 footnote a | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Provided respondents with information of support services; alerted appropriate authorities. |

Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| United States | Finkelhor, Ormrod et al., 2005Footnote 12 | Developmental Victimization Survey, 2002-2003 | Telephone interview | 1000 youths age 10–17 | JVQ | Youth: 79.5% | 10 $ | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Followed up with respondents who disclosed threatening situations. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • |

| Finkelhor et al., 2011Footnote 82 Finkelhor et al., 2009Footnote 28 Mitchell et al., 2011Footnote 83 Finkelhor et al., 2005Footnote 84 Hamby et al., 2013Footnote 85 |

National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV), 2008 | Telephone interview | 2095 youths age 10–17 | JVQ CM: α 0.39; SA: α 0.35–0.51 Test-retest CM: К 0.52; 91% agreement (3–4 weeks after); EIPV: К 1.0; 100% agreement (3–4 weeks after) JVQ correlated to TSC CM: r = 0.14–0.35, p < 0.01; SA: r = 0.11–0.34, p < 0.01 |

Youth: 54% | 20 $ | 45 min | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Followed up with respondents who disclosed threatening situations; gave sensitivity training to interviewers; alerted appropriate authorities. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Finkelhor et al., 2013Footnote 13 Hamby et al., 2005Footnote 86 Finkelhor et al., 2014Footnote 87 |

NatSCEV II, 2011 | Telephone interview | N not provided youths age 14–17 |

Validity: JVQ compared with other CM data |

Youth: 40.4% | 20 $ | 55 min | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Followed up with respondents who disclosed threatening situations; provided respondents with information of support services. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Finkelhor et al., 2015Footnote 88, Finkelhor et al., 2015Footnote 89 |

National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence, 2014 | Telephone interview | N not provided youths age 14–17 1949 youths age 10–17 |

JVQ | Varied by recruitment 15.1%–67.0% Youth: 14.2%–67.0% |

5 $, 20 $ |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P/Y | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Followed up with respondents who disclosed threatening situations. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| McLaughlin et al., 2012Footnote 40, Strauss, 1979Footnote 90 McLaughlin et al., 2013Footnote 91 McChesney et al., 2015Footnote 92 Merikangas et al., 2009Footnote 93 |

National Comorbidity Survey – Adolescent Supplement, 2001-2004 | Face-to-face interview | 6483 youths age 13–17 | CTS (modified), Composite International Diagnostic Interview (modified) and Child Welfare Questionnaire | School: 86.8% Student: 82.6% | 50 $ | ≈ 2h30 | Table 3 footnote — | Y | P | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Begle et al., 2011Footnote 4 Danielson et al., 2010Footnote 94 Hawkins et al., 2010Footnote 95 McCauley et al., 2010Footnote 96 McCart et al., 2011Footnote 97 Andrews et al., 2015Footnote 98 |

National Survey of Adolescents Replication, 2005 | Telephone interview | 3614 youths age 12–17 | SA: α 0.99; PA: α 0.72; EIPV: α 0.64Footnote 73 |

Youth: 52.2% | 10 $ | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Y | P | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Provided respondents with information of support services; followed up with respondents who disclosed threatening situations; alerted appropriate authorities. | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | |

| Haley et al., 2010Footnote 99 Oregon Teen Survey, 2005Footnote 270 |

Oregon Healthy Teen Survey, 2005 | Self-administered questionnaire | 16 289 students age 13–17 | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Alriksson-Schmidt et al., 2010Footnote 101 Eaton et al., 2006Footnote 102 |

National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 2005 | Self-administered questionnaire | 7181 female students age 15–18 | Table 3 footnote — | Student: 52.2% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Basile et al., 2006Footnote 3 Brener et al., 2004Footnote 103 |

YRBS, 2003 | Self-administered questionnaire | 13 080 grade 9–12 students | Table 3 footnote — | School: 67.0–100.0% Student: 60.0–94.0% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Howard & Wang, 2005Footnote 104 | YRBS, 2001 | Self-administered questionnaire | 13 601 students age 14–18 | Table 3 footnote — | School: 75.0% Student: 83.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Lippe et al., 2008Footnote 105 | YRBS, 2007 | Self-administered questionnaire | Samoa: 3625 Northern Mariana Islands: 2292 Marshall Islands: 1522 Guam: 1716 Palau: 732 students age 14–18 |

Table 3 footnote — | School: 100.0% Student: 78.0%–90.0% |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | P | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Peleg-Oren et al., 2013Footnote 106 | Florida YRBS, 2005 | Self-administered questionnaire | 4564 students grade 9–12 | Table 3 footnote — | School x Student: 66.0% | Table 3 footnote — | 50 min | Table 3 footnote — | Y | P | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Namibia, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe | Brown et al., 2009Footnote 107 WHO, 2017Footnote 56 |

GSHS, 2003-2004 | Self-administered questionnaire | 22 656 students age 13–15 | Table 3 footnote — | School: 90.0–100.0% Student: 75.0–99.0% | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| European Union | Kassis et al., 2013Footnote 41 Kassis & Puhe, 2009Footnote 108 |

Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Spain, 2009 | Self-administered questionnaire | 5149 students age 13–15 | Family Violence Inventory EIPV: α 0.88; EIPV (EM): α 0.85; PA: α 0.83 |

Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | Table 3 footnote — | N/A | S/P/Y | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | Table 3 footnote • | Provided respondents with information of support services. | N/A | Table 3 footnote • | N/A | N/A | Table 3 footnote • |

|

Abbreviations: CM, child maltreatment; CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale; CTSPC, Parent Child Conflict Tactics Scale; EIPV, exposure to intimate partner violence; EM, emotional maltreatment; ICAST-CH, ISPCAN child abuse screening tool-child; ISPCAN, International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect; JVQ, Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire; LEQAV, Life Event Questionnaire – adolescent version; NG, neglect; P, parent; PA, physical abuse; S, school; SA, sexual abuse; T, teacher; TSC, Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children; Y, youth. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The most commonly mentioned procedures in place for reducing or dealing with participant distress were as follows: (1) providing respondents with information and telephone numbers of appropriate support services; (2) following up with respondents who disclosed threatening situations; (3) giving focused, sensitivity training to interviewers; (4) alerting appropriate authorities when intervention was deemed necessary. Of course, disclosure to participants of the possibility of alerting authorities could negatively influence participation.

Of the maltreatment types, sexual abuse was captured most frequently in the survey questions (see Table 3). The majority of maltreatment measures specified behaviours, rather than being self-defined; sexual abuse was stipulated with the most detail. Child maltreatment prevalence estimates varied by measure and were not always reported. The heterogeneity of measures and variation in time periods covered precluded meaningful comparisons of prevalence estimates. Summary estimates for lifetime prevalence ranged from 0.3% to 44.3% for sexual abuse, 4.2% to 58.3% for physical abuse, 3.1% to 78.3% for emotional maltreatment, 0.9% to 38.3% for neglect, and 0.6% to 30.9% for exposure to intimate partner violence.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review reflect the extensive effort that has been made to measure child maltreatment at the population level and thus the perceived importance of this problem across the world. The review identified a variety of strategies employed to enhance data accuracy and mitigate participants' distress. Our findings were similar to those found in the review from 2000.Footnote 17 However, both our findings and theirs demonstrate that information on child maltreatment can be collected, albeit the issue of inconsistent definitions remains.

Identifying surveys and factors influencing prevalence estimates

Prevalence estimates of child maltreatment varied widely among the studies examined. In assessing findings across surveys, it is important to consider factors intrinsic to self-reporting that can compromise comparability.Footnote 24 Barriers include self-blame, cognitive development and age, stigma, fear of retaliation by the perpetrator, and failure to recognize behaviour as abusive.Footnote 16 Regarding the latter, differing perceptions of what constitutes discipline versus abuse can contribute to inconsistencies in response.Footnote 8 In some cultures, the use of physical punishment is commonplace and even legally accepted,Footnote 31,Footnote 39 while in others it is considered to be abuse.Footnote 109 In some studies, behaviours related to sexual abuse were not assessed because the topic was deemed too culturally sensitive.Footnote 50,Footnote 60

Variations in prevalence estimates of child maltreatment across studies might also be attributable to differences in measures. For example, with the objective of encouraging disclosure of sexual abuse, some surveys stipulate specific behaviours,Footnote 3 while others use more generally-worded questions.Footnote 101 Some measures of maltreatment are dichotomous (yes-no), in contrast to others that ask for details on severity and frequency.

Dissimilarities in conceptual scope can also influence prevalence estimates. For example, some but not all surveys explicitly include online victimization as a component of sexual abuse. Finally, the particular vocabulary used to describe specific behaviours may also impact comparability. For example, the expression, "forced sex without consent," might be interpreted more broadly than "rape," and thus be more apt to elicit a positive response (and increase apparent prevalence). Neglect was measured in only a few surveys—perhaps reflecting the challenges inherent to capturing it in population surveys. In some communities, relatively lower estimates of neglect were attributable to close social networks and living arrangements.Footnote 65 Efforts to improve the collection of data on neglect in population-based surveys and from young respondents are currently under way.Footnote 110,Footnote 111

Quality of data

The majority of the articles examined provided no detailed information on the reliability or validity of measures used within surveys. Statements such as "the reliability of the scale has been well-documented," or indicating that validity had been determined by the authors, were common but not fully informative. Unfortunately, only three articles reported validity.Footnote 80,Footnote 84,Footnote 87 In terms of reliability, internal consistency assessed by Cronbach alpha was documented most often followed by inter-rater reliability assessed as percentage agreement.

Internal consistency may have limited use given that some maltreatment behaviours may not be related. For example, some forms of neglect may not relate to other forms of neglect nor with other types of child maltreatment. Due to these complexities of internal consistency, this measure must be interpreted with caution.Footnote 84,Footnote 112 In general, surveying youth yields data that are only minimally affected by recall bias.Footnote 113 Of course, validity may still be compromised by social desirability bias, due to the delicate nature of maltreatment questions. However, research revealed few difficulties arising from the sensitivity of the questions.Footnote 24,Footnote 53,Footnote 61 The different developmental stage of the reviewed measures may partially explain why few psychometric properties of child maltreatment measures were reported. Newer measures were often adjusted for cultural and language adaptations; continued testing should lead to improvements in data accuracy.

Data quality and response rate are also affected by technical aspects of data collection and the setting in which it takes place. Most of the studies reviewed were based on surveys conducted within schools—where all students were responding to the same survey at the same time—and thus obtained high response rates. However, willingness to participate was not universal among schools, for reasons unrelated to child maltreatment questions.Footnote 33,Footnote 53,Footnote 57 Research suggests that among students, maximizing privacy and guaranteeing anonymity are effective in ensuring high response rates.Footnote 45 The importance of privacy was also underscored in a study in which younger participants (age 10 years) found responding to a survey more upsetting in the presence of the caregiver than when they were alone.Footnote 114

The means by which consent for survey participation is obtained can also affect the response rate; the requirement for consent from parents may discourage participation, especially among youth who have experienced child maltreatment.Footnote 47,Footnote 51,Footnote 115 Parental passive consent was used in multiple surveys to increase response rate and avoid sampling bias potentially related to active parental consent.Footnote 65,Footnote 80,Footnote 106 In one study, researchers designed and used a modified consent procedure in case any of the participants were being maltreated by a primary caregiver.Footnote 58

Ethical considerations

Eliciting information about experience with child maltreatment is a delicate matter; the manner in which questions are worded is an important consideration. Even a survey's name can potentially evoke anxiety and may lead to unwillingness to participate (e.g. stronger emotions may be triggered by reference to a survey on "child maltreatment" than to one on "child health"). Similarly, the language used in questions about experience with child maltreatment can affect the respondent. Sensitivity to the potential for adverse reactions is critical, as is a clear statement assuring the anonymity and confidentiality of the survey. However, the review found that some researchers included a confidentiality breach procedure in the consent form if a youth was in need of protection, which allowed automatic referral of participants to appropriate authorities.Footnote 50,Footnote 75,Footnote 81 This strategy did not negatively affect response rate.Footnote 75,Footnote 81

This review suggests that youth are generally comfortable in answering questions about their experience with child maltreatment.Footnote 12,Footnote 14,Footnote 71,Footnote 116 One study showed that 4.6% of youth reported being upset when answering a child maltreatment survey, but of these, 95.3% said they would nonetheless participate in a similar survey.Footnote 116 Interestingly, from the 17.3% of participants who had reported experiences classified as high-risk, only 2% were referred for counselling services.Footnote 116 In addition, one article mentioned that sexual abuse questions were not answered by 11% of respondents, but did not offer adequate information to assess if non-responses were higher for sexual abuse questions than for others.Footnote 2 However, several researchers concluded that the potential benefits from the information obtained from child maltreatment questions exceed the potential respondent distress.Footnote 7,Footnote 116,Footnote 117 An earlier study in adolescents comparing stress produced by child maltreatment questions with that arising from questions about school marks found no differences.Footnote 118

Limitations

Several limitations affect this review. First, inconsistencies in child maltreatment measures across surveys—and sometimes even within different cycles of the same survey—made classification challenging. Second, some articles that otherwise met the criteria for inclusion in the review were excluded on the basis of insufficient methodological information. For instance, papers failing to identify the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim or to distinguish between exposure to family violence and community violence were not included. Third, prevalence estimates were not provided in a standardised way. Fourth, steps taken to increase the response rate could often not be distinguished from those taken to increase the comfort of the respondent, so they were considered in combination. Fifth, measures had often been modified from their original version, and results of validity and reliability testing of the modified versions were not usually provided. Sixth, certain segments of the population were excluded either because they do not attend school or were absent the day of data collection. Seventh, the exclusion of articles in languages other than English limited the international scope of the review. Eighth, only peer-reviewed articles have been included in the review, which may introduce publication bias. Finally, limiting the review to the articles without examining the underlying surveys likely resulted in the exclusion of some relevant information.

Implications

This review shows that child maltreatment is a common concern across a range of societies and cultures although Canadian national data were missing. As evidenced by the large number of self-report surveys and studies asking youth about their level of comfort, data on child maltreatment can be collected responsibly and ethically from youth in a way that protects their health and well-being.Footnote 14,Footnote 116 Surveillance and research on child maltreatment would benefit greatly from the routine inclusion of questions on the subject in population-based self-report health surveys. Hovdestad and TonmyrFootnote 119 stressed the importance of setting the stage for inclusion of child maltreatment questions in surveys by a) preparing for early resistance, b) building a broad base of support, c) having knowledge of the current literature (including issues addressed in this article), and d) being willing to compromise and showing determination. Data collected on a regular basis would provide the opportunity for enhancing our understanding of the burden and the factors that are correlated with child maltreatment.Footnote 120 Schools could be an excellent venue for data collection due to high participation in these surveys and high enrolment among youth. After required discussions and agreements with the appropriate school authorities, it is easy to have procedures in place to obtain youth consent to participate and parents/caregivers passive consent. To maximize the quality of the data, measures used in collection should undergo reliability and validity testing, and all aspects of the survey methodology should be sound. Behaviour-based questions with response options capturing severity and frequency are also recommended.

Protocols to address potential participant distress should be established, and interviewers should be trained to conduct research sensitively and appropriately. Effective means of evaluating participant distress should be refined and applied, and the results of such evaluations should inform questionnaire design and language. Surveys should be conducted according to a strict code of ethics, the overarching goals of which should be the protection of privacy and confidentiality, and respect for respondents.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge assistance with the preparation of this manuscript from Kathryn Wilkins, Tanya Pires, Tanya Lary and Jaskiran Kaur, who provided useful comments on earlier drafts.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict to declare.

Authors' contributions and statement

L.T. conceived and designed the study. C.W., L.T., and J.L. wrote the paper: L.T. wrote the protocol, with input from the others. J.L., L.T., C.W., J.D., and S.A. extracted and categorized the data. L.T. led the evaluative component.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Saewyc EM, Tonkin R. Surveying adolescents: focusing on positive development. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13(1):43-7.

- Footnote 2

-

Asgeirsdottir BB, Sigfusdottir ID, Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF. Associations between sexual abuse and family conflict/violence, self-injurious behavior, and substance use: the mediating role of depressed mood and anger. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(3):210-19. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.003.

- Footnote 3

-

Basile KC, Black MC, Simon TR, et al. The association between self-reported lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse and recent health-risk behaviors: findings from the 2003 national youth risk behavior survey. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(5):752.e1-7.

- Footnote 4

-

Begle AM, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, McCart MR, Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, et al. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency: findings from the national survey of adolescents. Addict Behav. 2011;36(7):682-9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026.

- Footnote 5

-

Rhodes AE, Boyle MH, Bethell J, Wekerle C, Goodman D, Tonmyr L, et al. Child maltreatment and onset of emergency department presentations for suicide-related behaviours. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(6):542-51.

- Footnote 6

-

Hovdestad W, Campeau A, Potter D, Tonmyr L. A systematic review of childhood maltreatment assessments in population-representative surveys since 1990. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123366. eCollection 2015.

- Footnote 7

-

Tonmyr L, Hovdestad WE, Draca J. Commentary on Canadian child maltreatment data. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(1):186-97.

- Footnote 8

-

Elliott K, Urquiza A. Ethnicity, culture, and child maltreatment. J Soc Issues. 2006;62(4):787-809.

- Footnote 9

-

Garbarino J, Ebata A. The significance of ethnic and cultural differences in child maltreatment. J Marriage Fam. 1983;45:773-83. doi: 10.2307/351790.

- Footnote 10

-

Smith C. Ethical considerations for the collection, analysis and publication of child maltreatment data. International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. 2016.

- Footnote 11

-

Riley AW. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4(4):371-6. doi 10.1367/A03-178R.1

- Footnote 12

-

Finkelhor D, Omrod R, Turner H, Hamby S. The victimization of children and youth: a comprehensive national survey. Child Maltreat. 2005;10(1):5-25.

- Footnote 13

-

Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: an update. JAMA Paediatr. 2013;167(7):614-21. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42.

- Footnote 14

-

Helweg-Larsen K, Boving-Larsen H. Ethical issues in youth surveys: potentials for conducting a national questionnaire study on adolescent schoolchildren's sexual experiences with adults. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(11);1878-82.

- Footnote 15

-

Helweg-Larsen K, Sundaram V, Curtis T, Boving Larsen H. The Danish Youth Survey 2002: Asking young people about sensitive issues. Int J Circumpol Heal. 2004;63(S2):147-152

- Footnote 16

-

Colin-Vézina D, De La Sablonniere-Griffin M, Palmer AM, Milne L. A preliminary mapping of individual, relational and social factors that impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;43:123-34. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.010.

- Footnote 17

-

Amaya-Jackson L, Socolar RRS, Hunter W, Runyan DK, Colindres, R. Directly questioning children and adolescent about maltreatment: a review of surveys measures used. J Interpers Violence. 2000;15(7):725-59.

- Footnote 18

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Footnote 19

-

Fergusson DM, McLeod GF, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(9):664-74.

- Footnote 20

-

MacMillan HL, Tanaka M, Duku E, Vaillancourt T, Boyle MH. Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: results from the Ontario Child Health Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(1):14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005.

- Footnote 21

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect: Major Findings. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2010.

- Footnote 22

-

Saewyc EM, Chen W. To what extent can adolescent suicide attempts be attributed to violence exposure? A population-based study from western Canada. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2013;32(1):79-94.

- Footnote 23

-

Wong WCW, Leung PWS, Tang CSK, et al. To unfold a hidden epidemic: prevalence of child maltreatment and its health implications among high school students in Guangzhou, China. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(7):441-50. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.010.

- Footnote 24

-

Helweg-Larsen K, Larsen, HB. The prevalence of unwanted and unlawful sexual experiences reported by Danish adolescents: results from a national youth survey in 2002. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1270-6. doi: 10.1080/08035250600589033.

- Footnote 25

-

Borges G, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, Orozco R, Molnar BE, Nock MK. Traumatic events and suicide-related outcomes among Mexico City adolescents. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2008;49(6):654-66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01868.x.

- Footnote 26

-

Priebe G, Svedin CG. Online or off-line victimisation and psychological well-being: a comparison of sexual-minority and heterosexual youth. Eur Child Adoles Psyc. 2012;21(10):569-82. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0294-5.

- Footnote 27

-

Pineda-Lucatero AG, Trujillo-Hernández B, Millán-Guerrero RO, Vásquez C. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among Mexican adolescents. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(2):184-9.

- Footnote 28

-

Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1411-23.

- Footnote 29

-

Chan KL, Yan E, Brownridge DA, Ip P. Associating child sexual abuse with child victimization in China. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1028-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.054.

- Footnote 30

-

Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, Steffenson AE, MacPhail C, Hlongwa-Madikizela L, et al. Young people's sexual health in south Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2005;19:1525-34.

- Footnote 31

-

Leung PWS, Wong WCW, Chen WQ, Tang CSK. Prevalence and determinants of child maltreatment among high school students in southern China: a large scale school based survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-27.

- Footnote 32

-

Aberle N, Ratković-Blažević V, Mitrović-Dittrich D, Coha R, Stoić A, Bublić J, et al. Emotional and physical abuse in family: survey among high school adolescents. Croat Med J. 2007;48(2):240-8.

- Footnote 33

-

Ellonen N, Kääriäinen J, Sariola H, Helweg-Larsen K, Larsen HB. Adolescents' experiences of parental violence in Danish and Finnish families: a comparative perspective. J Scand Stud Criminol Crime Prev. 2011;12(2):173-97. doi: 10.1080/14043858.2011.622076.

- Footnote 34

-

Chan KL. Children exposed to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence: a study of co-occurrence among Hong Kong Chinese families. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:532-42. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.03.006.

- Footnote 35

-

Seedat S, Nyamai C, Njenga F, Vythilingum, B, Stein DJ. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress symptoms in urban African schools: survey in Cape Town and Nairobi. Brit J Psychiat. 2004;184:169-75.

- Footnote 36

-

Breiding MJ, Mercy JA, Gulaid J, Reza A, Hleta-Nkambule N. A national survey of childhood physical abuse among females in Swaziland. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013;3(2):73-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.02.006.

- Footnote 37

-

Cyr K, Chamberland C, Clement M, Lessard G, Wemmers J, Collin-Vézina D, et al. Polyvictimization and victimization of children and youth: results from a population survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:814-20. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.009.

- Footnote 38

-

Lepistö S, Åstedt-Kurki P, Joronen K, Luukkaala T, Paavilainen E. Adolescents' experiences of coping with domestic violence. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1232-45. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.009.

- Footnote 39

-

Bussmann K. Evaluating the subtle impact of a ban on corporal punishment of children in Germany. Child Abuse Rev. 2004;13(5):292-311. doi: 10.1002/car.866.

- Footnote 40

-

McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1151-60. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277.

- Footnote 41

-

Kassis W, Artz S, Scambor C, Scambor E, Moldenhauer S. Finding the way out: a non-dichotomous understanding of violence and depression resilience of adolescents who are exposed to family violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(2):181-9. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.001.

- Footnote 42

-

Horta RL, Horta BL, Costa AWN, et al. Lifetime use of illicit drugs and associated factors among Brazilian schoolchildren, National Adolescent School-based Health Survey (PeNSE 2012). Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2014;17:s31-45. doi: 10.1590/1809-4503201400050004.

- Footnote 43

-

Malta DC, Mascarenhas MDM, Dias AR, Prado RRd, Lima CM, Silva, MM.A da, et al. Situations of violence experienced by students in the state capitals and the Federal District: results from the National Adolescent School-based Health Survey (PeNSE 2012). Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2014;17:s158-71.

- Footnote 44

-

Tonkin RS, Murphy A, Chittenden M, et al. Health Youth Development: Highlights from the 2003 Adolescent Health Survey. [Internet]. Vancouver (BC): McCreary Centre Society; 2004. [cited 2016 January 14] Available from: http://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/AHS-3_provincial.pdf

- Footnote 45

-

Tonkin RS. British Columbia Youth Health Trends: A Retrospective, 1992-2003. [Internet]. Vancouver (BC): McCreary Centre Society; 2005. [cited 2016 January 14] Available from: http://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/AHS-Trends-2005-report.pdf

- Footnote 46

-

Saewyc E, Wang N, Chittenden M, Murphy A. Building resilience in vulnerable youth. [Internet]. Vancouver (BC): McCreary Center Society; 2006. [cited 2016 Jan 14]. Available from: http://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/vulnerable_youth_report.pdf

- Footnote 47

-

Saewyc E, Green R. Survey Methodology for the 2008 BC Adolescent Health Survey IV. Vancouver (BC): McCreary Center Society; 2009.

- Footnote 48

-

Lau JTF, Kim JH, Tsui HY, Phil M, Cheung A, Lau M et al. The relationship between physical maltreatment and substance use among adolescents: a survey of 95, 788 adolescents in Hong Kong. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:110-9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.141970.

- Footnote 49

-

Tang CS. Corporal punishment and physical maltreatment against children: a community study on Chinese parents in Hong Kong. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:893-907.

- Footnote 50

-

Ajdukovic M, Susac, N, Rajter M. Gender and age differences in prevalence and incidence of child abuse in Croatia. Croat Med J. 2013;53:469-79. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2013.54.469.

- Footnote 51

-

Helweg-Larsen K, Frederiksen ML, Larsen HB. Violence, a risk factor for poor mental health in adolescence: a Danish nationally representative youth survey. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(8):849-56. doi: 10.1177/1403494811421638.

- Footnote 52

-

Frederiksen ML, Helweg-Larsen K, Larsen HB. Self-reported violence amongst adolescents in Denmark: is alcohol a serious risk factor? Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(5):636-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00735.x.

- Footnote 53

-

Van Gastel WA, Tempelaar W, Bun C, Schubart CD, Kahn RS, Plevier C, et al. Cannabis use as an indicator of risk for mental health problems in adolescents: a population-based study at secondary schools. Psychol Med. 2013;43(9):1849-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00735.x.

- Footnote 54

-

Sariola H, Uutela A. The prevalence and context of family violence against children in Finland. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16(6):823-32.

- Footnote 55

-

Ohene SA, Johnson K, AtunahJay S, Owusu A, Borowsky IW. Sexual and physical violence victimization among senior high school students in Ghana: risk and protective factors. Soc Sci Med. 2015;146:266-75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.019.

- Footnote 56

-

World Health Organization. Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS) Purpose and Methodology. [cited 2017 oct 22] Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/gshs/methodology/en/

- Footnote 57

-

Fotiou A, Kanavou E, Richardson C, Ploumpidis D, Kokkevi A. Misuse of prescription opioid analgesics among adolescents in Greece: the importance of peer use and past prescriptions. Drugs: Educ Prev Polic. 2014;21(5):357-69. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2014.899989.

- Footnote 58

-

Flynn-O'Brien KT, Rivara FP, Weiss NS, et al. Prevalence of physical violence against children in Haiti: a national population-based cross sectional survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:154-62. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.021.

- Footnote 59

-

Patel V, Andrew G. Gender, sexual abuse and risk behaviours in adolescents: a cross-sectional survey in schools in Goa. Natl Med J India. 2001;14(5):263-7.

- Footnote 60

-

Mahram M, Hosseinkhani Z, Nedjat S, Aflatouni A. Epidemiologic evaluation of child abuse and neglect in school-aged children of Qazvin province, Iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23(2):159-64.

- Footnote 61

-

Okech JEA. A multidimensional assessment of children in conflictual contexts: the case of Kenya. Int J Adv Couns. 2012;34(4):331-48.

- Footnote 62

-

Frias SM, Erviti J. Gendered experiences of sexual abuse of teenagers and children in Mexico. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(4):776-87. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.12.001.

- Footnote 63

-