Quantile regression of analysis of language and interpregnancy interval in Quebec, Canada

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Nathalie Auger, MD, FRCPC Endnote 1,Endnote 2; Lucien Lemieux, MSc Endnote 3; Marianne Bilodeau-Bertrand, MSc Endnote 1,Endnote 2; Amadou Diogo Barry, MSc Endnote 4; André Costopoulos, PhD Endnote 5

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.5.02

This original quantitative research article has been peer reviewed.

Correspondence: Nathalie Auger, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, 190 Cremazie E Blvd, Montréal, QC H2P 1E2; Tel: 514-864-1600, ext. 3717; Email: nathalie.auger@inspq.qc.ca

Abstract

Introduction: Short and long interpregnancy intervals are associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as miscarriage and preterm delivery, but cultural differences in interpregnancy intervals are understudied. Identifying cultural inequality in interpregnancy intervals is necessary to improve maternal-child outcomes. We assessed interpregnancy intervals for Anglophones and Francophones in Quebec.

Methods: We obtained birth records for all infants born in Quebec, 1989−2011. We identified 571 461 women with at least two births, and determined the interpregnancy interval. We defined short interpregnancy intervals (< 18 months) as the 20th percentile of the distribution, and long intervals (≥ 60 months) as the 80th percentile. Using quantile regression, we evaluated the association of language with short and long intervals, adjusted for maternal characteristics. We assessed differences over time and by maternal age for disadvantaged groups defined as no high school diploma, rural residence, and material deprivation.

Results: In adjusted regression models, Anglophones who had no high school diploma had intervals that were 1.0 month (95% CI: −1.5 to −0.4) shorter than Francophones at the 20th percentile of the distribution, and 1.9 months (−0.5 to 4.3) longer at the 80th percentile. Results were similar for Anglophones in rural and materially deprived areas. The trends persisted over time, but were stronger for women < 30 years. There were no differences between advantaged Anglophones and Francophones.

Conclusion: Disadvantaged Anglophones are more likely to have short and long interpregnancy intervals relative to Francophones in Quebec. Public health interventions to improve perinatal health should target suboptimal intervals among disadvantaged Anglophones.

Keywords: birth intervals, cultural deprivation, language, socioeconomic factors

Highlights

- We investigated differences in interpregnancy intervals between the Anglophone minority and Francophone majority in Quebec, Canada.

- Disadvantaged Anglophones had more suboptimal intervals than Francophones.

- Very short and long interpregnancy intervals were both more common in disadvantaged Anglophones.

- The trends persisted over time, and were stronger for young women.

- There were no differences between advantaged Anglophones and Francophones.

Introduction

A growing number of studies report ethnocultural differences in maternal-child health indicators, including preterm birth, delayed fetal growth and stillbirth.Footnote 1,Footnote 2,Footnote 3 However, ethnic or cultural differences in interpregnancy intervals are rarely studied. In the United States, ethnic minorities have interpregnancy intervals that are disproportionately more extreme on both ends of the distribution. Black women have a higher risk of short (< 18 months) and long (≥ 60 months) interpregnancy intervals compared with majority White women, and Hispanic women tend to have longer intervals.Footnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 6,Footnote 7 Short and long interpregnancy intervals are associated with miscarriage, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, maternal cardiovascular disease and mortality.Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 10,Footnote 11 Suboptimal intervals increase the risk of preterm delivery, small-for-gestational-age birth, congenital anomalies, autism disorder, and fetal and infant mortality.Footnote 9,Footnote 12,Footnote 13 It is thought that short interpregnancy intervals do not give women sufficient time to recover from the physical stress of the previous pregnancy, including nutritional depletion.Footnote 8,Footnote 11,Footnote 14 By contrast, long interpregnancy intervals do not benefit from adaptions in the genital and cardiovascular systems that recede naturally with time. It is thought that the physiological capacities of women become comparable to those of the first pregnancy, where the risk of diverse maternal-child outcomes is higher.Footnote 14 These effects are believed to be independent of maternal age.Footnote 8,Footnote 11,Footnote 14 Better documentation of ethnocultural differences in interpregnancy intervals is needed, since attempts to optimize interpregnancy intervals may improve maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Our objective was to determine if differences in interpregnancy intervals were present between Anglophones and Francophones in the province of Quebec, Canada. French is the official language in Quebec, where most of the population is Francophone (79.1% in 2016) and the minority is Anglophone (9.7%).Footnote 15 In Quebec, language is associated with cultural norms and access to health care, and is frequently used to measure health differences.Footnote 16 In recent decades, Anglophone socioeconomic status has decreased due to higher unemployment rates and larger proportions living below the low income cut-off compared with Francophones.Footnote 17 Several studies indicate that Anglophones, particularly socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones, have increasing rates of stillbirth, preterm birth and small-for-gestational-age birth.Footnote 18,Footnote 19 We investigated the possibility that lingo-cultural differences in interpregnancy intervals were present in Quebec, and assessed trends over time and socioeconomic status. Our hypothesis was that socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones are presently at greater risk of suboptimal interpregnancy intervals compared with Francophones.

Methods

Data

We obtained live birth and stillbirth files from the Ministry of Health and Social Services for all infants to women who gave birth in Quebec, Canada, 1989−2011.Footnote 20 The data covered the entire province, and contained maternal characteristics such as language and parity as well as information on the prior delivery. We selected women who had at least two births and focussed the analysis on the interpregnancy interval between the first and second child, as women in Quebec rarely have a third child. We excluded multiple births to rule out the contribution of pregnancy-specific disorders not found in singleton births. There were in total 622 812 women who delivered at least two times and had information on language and the timing of the first and second birth.

Language

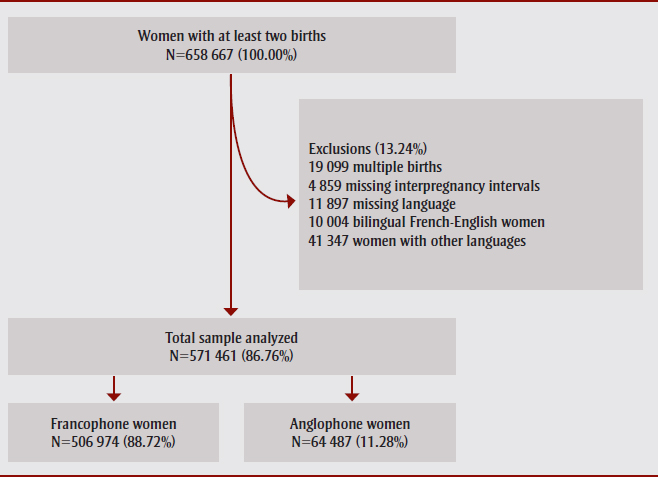

To determine the maternal language, we used the language spoken at home which was self-reported on birth certificates and reflects the language used by both parents in the home setting. We considered mothers who reported English with or without another non-French language as Anglophone, following previous research.Footnote 17,Footnote 18,Footnote 19,Footnote 21 We considered mothers who reported French with or without another non-English language as Francophone. Due to small numbers, we excluded 10 004 bilingual French-English women, as these were too few to analyze. Similarly, we excluded 41 347 women with other languages, a heterogeneous group that comprised a wide range of languages which was difficult to interpret. The final sample comprised 571 461 Anglophone and Francophone women (Figure 1). For simplicity, we used the terms language and language spoken at home interchangeably hereafter to describe the results.

Figure 1 - Text Description

This figure illustrates the process through which the study population was selected. 658 667 women who had at least two births were first selected. Exclusion criteria were as follows: multiple births (19 099), missing interpregnancy intervals (4 859), missing language (11 897), bilingual French-English women (10 004) and women with other languages (41 347). The final sample comprised 571 461 Anglophone and Francophone women. There were 506 974 Francophone women and 64 487 Anglophone women.

Interpregnancy interval

The interpregnancy interval was defined as the time between the first delivery and conception of the second pregnancy.Footnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 6,Footnote 7,Footnote 9,Footnote 22,Footnote 23 The World Health Organization encourages a minimum interval of 24 months between pregnancies,Footnote 9 following evidence that intervals shorter than 18 months, or longer than 60 months, increase the risk of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes.Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 10,Footnote 11,Footnote 12,Footnote 13 To calculate the interpregnancy interval, we subtracted the date of delivery of the first-born infant from the conception date of the second-born infant. We estimated the conception date by subtracting the gestational age from the delivery date, with a two-week correction for the average time of ovulation. We expressed the interpregnancy interval as a continuous variable in months, and for descriptive statistics categorized the interval as short (less than 18 months), optimal (18 to 59 months), or long (60 months or more) following previous literature.Footnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 7,Footnote 9,Footnote 22

Socioeconomic status

We selected three markers of socioeconomic status, including education (no high school diploma, high school diploma/postsecondary training, university, unknown), place of residence (urban, rural, unknown), and material area deprivation quintile based on a composite score of census data on neighbourhood income, employment and education (low, low-middle, middle, middle-high, high deprivation, unknown).Footnote 24 Education and place of residence were measured at an individual-level, while material deprivation was measured at an area level based on the 1991, 1996, 2001 and 2006 Censuses. We selected these indicators based on current literature of socioeconomic status. Education is a well-established marker of socioeconomic status shown to be associated with interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 6,Footnote 7,Footnote 22 Rurality is a marker of low socioeconomic status also associated with reproductive health, including short interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 23,Footnote 25 Material deprivation is an indicator of area socioeconomic status frequently used to investigate perinatal health differences.Footnote 21,Footnote 24

Covariates

We accounted for additional covariates possibly related to the interpregnancy interval, including maternal immigrant status (Canadian-born, foreign-born, unknown) and time period at second delivery (1989−1999, 2000−2011). Several studies report an association between foreign place of birth and interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 6,Footnote 7,Footnote 22 We included periods to evaluate trends over time, and limited the analysis to two time periods to make sure there were enough women in each period to enable comparisons. We did not adjust for maternal age in the primary analysis, as women who are older at their first pregnancy cannot have long interpregnancy intervals for physiological reasons. Adjustment for maternal age may cause over-adjustment bias in regression models because there are no older women with long interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 26

Data analysis

We computed the proportion of Anglophone and Francophone women with short (less than 18 months), optimal (18 to 59 months), and long (60 months or more) interpregnancy intervals, and plotted the distribution for each language group according to socioeconomic characteristics. In regression models, we analyzed the interpregnancy interval as a continuous variable. Linear regression is the traditional method used for continuous outcomes. Linear regression estimates the mean difference in interpregnancy intervals between Anglophones and Francophones, but provides no estimate of the difference at the tails of the distribution,Footnote 27 which is a disadvantage since very low and very high intervals are problematic for maternal-infant health, not mean intervals.

We instead used quantile regression, a method that overcomes the limitations of linear regression by analyzing the entire distribution of the interpregnancy interval. Quantile regression divides the distribution of the interpregnancy interval in quantiles of equal proportion.Footnote 28 The relationship with language is modelled at each quantile of the interpregnancy interval.Footnote 27 Thus, quantile regression can assess the association of language with short interpregnancy intervals, as well as with long interpregnancy intervals.

We used quantile regression models with the interpregnancy interval divided in 20 equal quantiles. We considered intervals at the 20th percentile of the distribution as short, and intervals at the 80th percentile as long, because these cut-off points approached the < 18 months and ≥ 60 months used in traditional analyses.Footnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 7,Footnote 9,Footnote 22 For both short and long intervals, we obtained the absolute difference in the interpregnancy interval between Anglophones and Francophones in months. We computed 95% CIs for all estimates, and adjusted for maternal education, rural residence, material deprivation, immigrant status, and time period at second delivery. We tested the interaction of language with socioeconomic characteristics, including maternal education, rural residence, and material deprivation. We assessed trends over time by comparing the association between language and interpregnancy intervals in 1989−1999 with the association in 2000−2011. Because maternal age may modify the associations, we ran regression models with the data stratified by age at first birth (< 30 vs. ≥ 30 years).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a range of sensitivity analyses. We estimated the association of language with interpregnancy intervals between the second and third birth for 210 631 women, and between the third and fourth birth for 60 972 women, to determine if linguistic differences persisted over the reproductive course of women. We examined models for Canadian-born and foreign-born mothers separately, to make sure that linguistic differences were not due to immigration. We examined the impact of excluding women who had stillbirth at first pregnancy, using the mother tongue of each parent instead of language spoken at home, and adjusting for maternal age. Finally, we assessed associations after excluding women from Aboriginal areas, since fertility is higher in these regions.

We performed the analysis in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We obtained an ethics waiver from the institutional review board of the University of Montréal Hospital Centre, as the study abided by ethical requirements for research on people in Canada.

Results

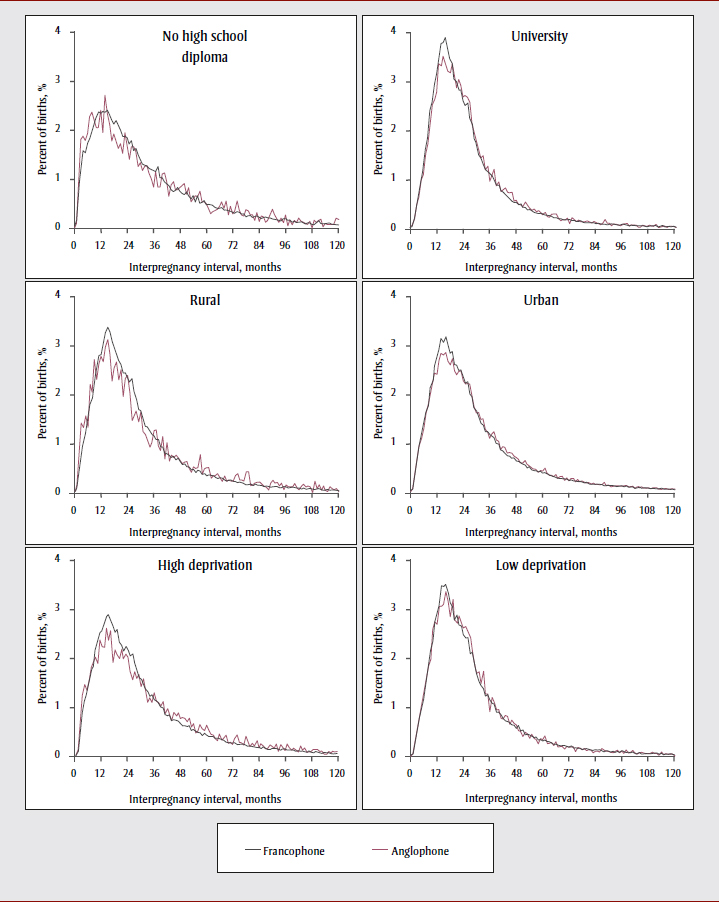

In this study, there were 506 974 Francophone and 64 487 Anglophone women (Table 1). 11.3% (95% CI: 11.2–11.4) of women were Anglophone. This proportion was slightly lower in women with interpregnancy intervals shorter than 18 months (10.6%; 95% CI: 10.5–10.8) and higher in women with intervals of 60 months or more (12.4%; 95% CI: 12.2–12.7). Interpregnancy intervals were generally longer for Anglophones than Francophones. Anglophones had a lower proportion of interpregnancy intervals shorter than 18 months (31.15% (20 089/64 487) vs. 33.35% (169 068/506 974) for Francophones, p < .001), and a greater proportion of intervals longer than 60 months or more (14.67% (9 458/64 487) vs. 13.14% (66 599/506 974) for Francophones, p < .001). Anglophones who had no high school diploma, lived in rural areas, or were materially deprived had a higher proportion of very short and long interpregnancy intervals than Francophones (Figure 2). The distribution of interpregnancy intervals was similar for Francophones and Anglophones who had university diplomas, lived in urban areas, or had low material deprivation.

| Characteristics | Total no. Francophone births | Francophone interpregnancy interval |

Total no. Anglophone births | Anglophone interpregnancy interval |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 18 months N (%) |

18‑59 months N (%) |

≥ 60 months N (%) |

< 18 months N (%) |

18‑59 months N (%) |

≥ 60 months N (%) |

|||

| Education | ||||||||

No high school diploma |

50 219 | 15 777 (31.4) | 24 635 (49.1) | 9 807 (19.5) | 4 673 | 1 521 (32.5) | 2 166 (46.4) | 986 (21.1) |

High school diploma |

294 582 | 94 821 (32.2) | 157 661 (53.5) | 42 100 (14.3) | 34 183 | 10 143 (29.7) | 18 276 (53.5) | 5 764 (16.9) |

University |

141 913 | 52 095 (36.7) | 78 124 (55.1) | 11 694 (8.2) | 21 651 | 7 250 (33.5) | 12 427 (57.4) | 1 974 (9.1) |

| Residence | ||||||||

Urban |

386 250 | 126 916 (32.9) | 207 695 (53.8) | 51 639 (13.4) | 58 875 | 18 145 (30.8) | 32 169 (54.6) | 8 561 (14.5) |

Rural |

116 957 | 40 758 (34.8) | 61 671 (52.7) | 14 528 (12.4) | 5 243 | 1 822 (34.8) | 2 575 (49.1) | 846 (16.1) |

| Material area deprivation | ||||||||

Low |

89 948 | 30 738 (34.2) | 49 539 (55.1) | 9 671 (10.8) | 20 086 | 6 575 (32.7) | 11 335 (56.4) | 2 176 (10.8) |

Low-middle |

104 191 | 34 437 (33.1) | 56 859 (54.6) | 12 895 (12.4) | 12 385 | 3 748 (30.3) | 6 897 (55.7) | 1 740 (14.0) |

Middle |

103 812 | 34 480 (33.2) | 55 638 (53.6) | 13 694 (13.2) | 9 604 | 2 888 (30.1) | 5 156 (53.7) | 1 560 (16.2) |

Middle-high |

100 086 | 33 508 (33.5) | 52 592 (52.5) | 13 986 (14.0) | 9 390 | 2 886 (30.7) | 4 914 (52.3) | 1 590 (16.9) |

High |

93 042 | 30 474 (32.8) | 48 356 (52.0) | 14 212 (15.3) | 10 695 | 3 269 (30.6) | 5 420 (50.7) | 2 006 (18.8) |

| Immigrant status | ||||||||

Canadian-born |

465 011 | 157 116 (33.8) | 249 058 (53.6) | 58 837 (12.7) | 43 028 | 13 819 (32.1) | 23 941 (55.6) | 5 268 (12.2) |

Foreign-born |

37 448 | 10 515 (28.1) | 19 860 (53.0) | 7 073 (18.9) | 19 567 | 5 683 (29.0) | 10 030 (51.3) | 3 854 (19.7) |

| Time period at second delivery | ||||||||

1989-1999 |

255 492 | 85 854 (33.6) | 136 808 (53.5) | 32 830 (12.8) | 30 604 | 9 783 (32.0) | 16 624 (54.3) | 4 197 (13.7) |

2000-2011 |

251 482 | 83 214 (33.1) | 134 499 (53.5) | 33 769 (13.4) | 33 883 | 10 306 (30.4) | 18 316 (54.1) | 5 261 (15.5) |

| Total | 506 974 | 169 068 (33.3) | 271 307 (53.5) | 66 599 (13.1) | 64 487 | 20 089 (31.2) | 34 940 (54.2) | 9 458 (14.7) |

Figure 2 - Text Description

In this figure, we see that Anglophones who had no high school diploma, lived in rural areas, or were materially deprived had a higher proportion of very short and long interpregnancy intervals than Francophones. The distribution of interpregnancy intervals was similar for Francophones and Anglophones who had university diplomas, lived in urban areas, or had low material deprivation.

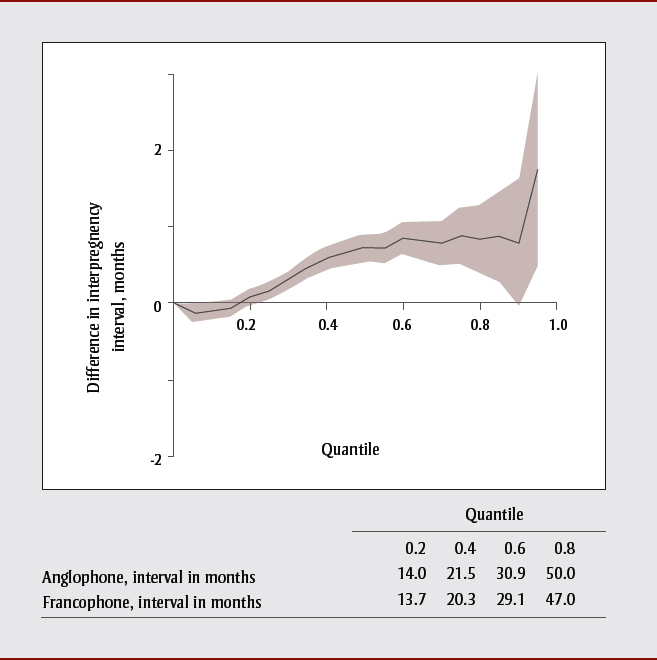

Quantile regression models adjusted for socioeconomic characteristics suggested that there was a linguistic difference in long (80th percentile) but not short (20th percentile) interpregnancy intervals (Figure 3). At the 80th percentile, Anglophones had intervals that were 0.8 months longer than Francophones (95% CI: 0.4−1.3). Interaction terms suggested that differences at the 80th percentile were greater for Anglophones who lived in rural areas (p < .001), or were materially deprived (p < .001). Although there was no difference at the 20th percentile between Anglophones and Francophones overall, interaction terms with socioeconomic characteristics suggested that intervals were shorter for Anglophones who had no high school diploma (p < .001), lived in rural areas (p < .001), or were materially deprived (p = .04).

Figure 3 - Text Description

This figure depicts quantile regression models adjusted for socioeconomic characteristics, which suggested that there was a linguistic difference in long (80th percentile) but not short (20th percentile) interpregnancy intervals. At the 80th percentile, Anglophones had intervals that were 0.8 months longer than Francophones (95% CI: 0.4−1.3).Interaction terms suggested that differences at the 80th percentile were greater for Anglophones who lived in rural areas (p < .001), or were materially deprived (p < .001). Although there was no difference at the 20th percentile between Anglophones and Francophones overall, interaction terms with socioeconomic characteristics suggested that intervals were shorter for Anglophones who had no high school diploma (p < .001), lived in rural areas (p < .001), or were materially deprived (p = .04).

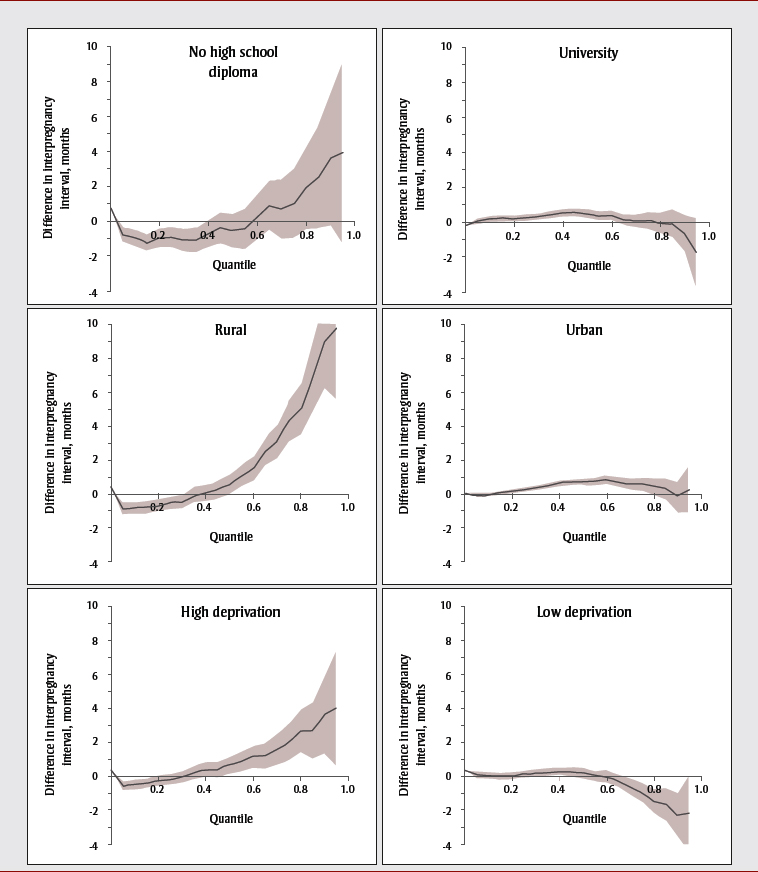

Short interpregnancy intervals

When we examined each socioeconomic group separately, results confirmed that disadvantaged Anglophones had shorter interpregnancy intervals than Francophones at the 20th percentile of the distribution (Figure 4). Anglophones with no high school diploma had intervals that were 1.0 months shorter than Francophones (95% CI: −1.5 to −0.4), and Anglophones in rural areas had intervals that were 0.7 months shorter (−1.0 to −0.3). However, intervals of materially deprived Anglophones were not statistically different relative to Francophones (0.2 months shorter; 95% CI: −0.6 to 0.1). Anglophones who had university diplomas, lived in urban areas, or had low material deprivation had interpregnancy intervals that were similar to Francophones.

Figure 4 - Text Description

This figure illustrates that disadvantaged Anglophones had shorter interpregnancy intervals than Francophones at the 20th percentile of the distribution. Anglophones with no high school diploma had intervals that were 1.0 months shorter than Francophones (95% CI: −1.5 to −0.4), and Anglophones in rural areas had intervals that were 0.7 months shorter (−1.0 to −0.3). However, intervals of materially deprived Anglophones were not statistically different relative to Francophones (0.2 months shorter; 95% CI: −0.6 to 0.1). Anglophones who had university diplomas, lived in urban areas, or had low material deprivation had interpregnancy intervals that were similar to Francophones.

In contrast, disadvantaged Anglophones had longer interpregnancy intervals at the 80th percentile of the distribution compared with Francophones. Anglophones in rural areas had intervals that were 5.0 months longer than Francophones (95% CI: 3.5 to 6.5), and materially deprived Anglophones had intervals that were 2.7 months longer (1.4 to 4.0). Anglophones with no high school diploma had intervals that were 1.9 months longer than Francophones, although the difference was not statistically significant (95% CI: −0.5 to 4.3). In contrast, Anglophones who had university diplomas or who lived in urban areas had interpregnancy intervals that were similar to Francophones, and Anglophones with low material deprivation had intervals that were 1.4 months shorter (95% CI: −2.1 to −0.7).

Long interpregnancy intervals

In contrast, disadvantaged Anglophones had longer interpregnancy intervals at the 80th percentile of the distribution compared with Francophones (Figure 4). Anglophones in rural areas had intervals that were 5.0 months longer than Francophones (95% CI: 3.5 to 6.5), and materially deprived Anglophones had intervals that were 2.7 months longer (1.4 to 4.0). Anglophones with no high school diploma had intervals that were 1.9 months longer than Francophones, although the difference was not statistically significant (95% CI: −0.5 to 4.3). In contrast, Anglophones who had university diplomas or who lived in urban areas had interpregnancy intervals that were similar to Francophones, and Anglophones with low material deprivation had intervals that were 1.4 months shorter (95% CI: −2.1 to −0.7).

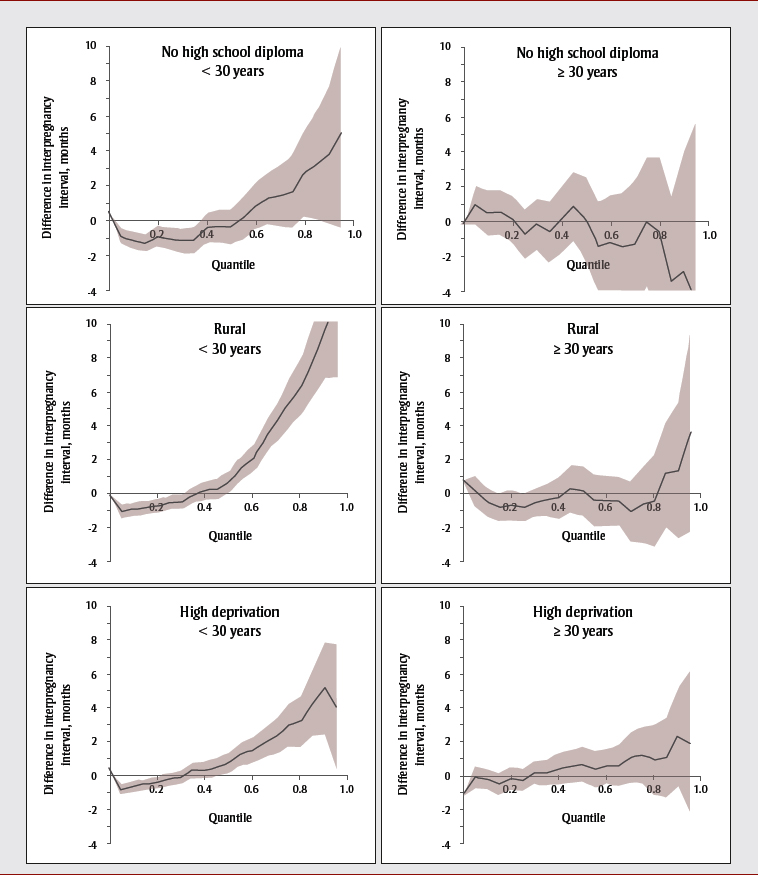

When we examined temporal trends over time, the difference between socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones and Francophones did not change over time. Differences between socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones and Francophones were, however, more prominent for women < 30 years compared with women ≥ 30 years (Figure 5). At the 20th percentile, Anglophones < 30 years with no high school diploma had intervals that were 0.9 months shorter than Francophones (95% CI: −1.5 to −0.3), and those in rural areas had intervals that were 0.7 months shorter (−1.1 to −0.3). At the 80th percentile, Anglophones < 30 years with no high school diploma had intervals that were 2.8 months longer than Francophones (95% CI: 0.2 to 5.3), those in rural areas had intervals that were 6.4 months longer (4.7 to 8.1), and those in materially deprived areas had intervals that were 3.3 months longer (1.8 to 4.7). In contrast, disadvantaged Anglophones ≥ 30 years had interpregnancy intervals that were similar to Francophones.

Figure 5 - Text Description

In this figure, we are able to see that differences between socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones and Francophones were more prominent for women < 30 years compared with women ≥ 30 years. At the 20th percentile, Anglophones < 30 years with no high school diploma had intervals that were 0.9 months shorter than Francophones, and those in rural areas had intervals that were 0.7 months shorter (−1.1 to −0.3). At the 80th percentile, Anglophones < 30 years with no high school diploma had intervals that were 2.8 months longer than Francophones (95% CI: 0.2 to 5.3), those in rural areas had intervals that were 6.4 months longer (4.7 to 8.1), and those in materially deprived areas had intervals that were 3.3 months longer (1.8 to 4.7). In contrast, disadvantaged Anglophones ≥ 30 years had interpregnancy intervals that were similar to Francophones.

In sensitivity analyses, linguistic differences in intervals between the second and third birth were similar to those between the first and second birth, however there was no difference in intervals between the third and fourth birth. Results were similar when data were stratified by maternal immigrant status, after excluding women with stillbirth at first pregnancy, and when we used the maternal or partner mother tongue as the exposure. Adjusting for maternal age had little impact on short intervals, and restricting to young women had no impact on long intervals. Excluding 2 923 women from Aboriginal areas did not change the results.

Discussion

In this study, we found differences in short and long interpregnancy intervals between Anglophones and Francophones of Quebec. Socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones had intervals that were less favourable than Francophones for both short and long intervals. At short intervals, Anglophones with no high school diploma, who lived in rural areas, or were materially deprived had interpregnancy intervals that were systematically shorter than Francophones. At long intervals, Anglophones with no high school diploma, who lived in rural areas, or were materially deprived had interpregnancy intervals that were systematically longer than Francophones. The differences persisted over time, and were stronger for younger women. In contrast there was no difference between socioeconomically advantaged Anglophones and Francophones. These findings add to the growing evidence that socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones may be a vulnerable population in Quebec, and are concerning as Anglophones have higher fertility,Footnote 21 and suboptimal interpregnancy intervals are associated with a wide range of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Few studies have attempted to measure cultural differences in interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 6,Footnote 7 These studies however do not investigate the entire distribution of interpregnancy intervals, and usually analyze the interval as a binary outcome. While the trends align with the results in our study, where minority Anglophones also had unfavourable interpregnancy intervals, it is difficult to know if the results are generalizable to minorities elsewhere.

Moreover, there are limited data on how lingo-cultural differences in interpregnancy intervals vary according to socioeconomic status. In some research, socioeconomically disadvantaged women have unfavourable interpregnancy intervals compared with advantaged women. Unemployment, low income, and rural residence are all associated with a higher risk of short interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 6,Footnote 23 Similarly, women with less education have a higher risk of long interpregnancy intervals compared with highly educated women.Footnote 6,Footnote 7 However, studies have not tested the possibility of interaction between ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Our results in fact suggest a strong interaction effect, as most of the difference between Anglophones and Francophones of Quebec was limited to disadvantaged women. There was no difference in interpregnancy intervals between advantaged Anglophones and Francophones. Breastfeeding may also affect interpregnancy intervals by delaying menstruation and the next pregnancy.Footnote 9 Breastfeeding initiation and duration differs according to ethnicity, and high education tends to be associated with longer duration of breastfeeding.Footnote 29

Family planning may also differ between linguistic and cultural subgroups. Some women may time their second pregnancies based on culture, age, career, or future income. For example, employed women, or women who are in school may choose to delay pregnancy.Footnote 4 However, researchers have shown that short interpregnancy intervals are frequently unplanned,Footnote 5 particularly for disadvantaged women,Footnote 23 while long intervals can be markers of fertility problems or change of partner.Footnote 30 Indeed, we found that disadvantaged Anglophones who were young were more likely to have very short or long intervals compared with Francophones, suggesting that effects of language are more prominent in young mothers. Family planning may be influenced by health care services, and we cannot exclude the possibility of language barriers in access to information on reproductive health. Disadvantaged Anglophones may be more affected, and have fewer opportunities to receive appropriate advice on contraception and optimal timing of a second pregnancy. French is the official language in Quebec and it is generally easier to receive Francophone health services in many parts of the province, especially in rural areas.Footnote 16

To our knowledge, temporal trends in interpregnancy intervals between ethnic, cultural or socioeconomic groups have not been studied in other countries. In Quebec, there is substantial evidence that disadvantaged Anglophones have increasing rates of stillbirth, preterm birth, and small-for-gestational-age birth.Footnote 18,Footnote 19 Anglophone fertility is also rising, particularly among materially deprived women.Footnote 21 These trends coincide with rising unemployment and low income among Anglophones.Footnote 16 The structure of language groups may also have changed over time due to disproportionate emigration of advantaged Anglophones to other Canadian provinces,Footnote 31and an increase and change in type of immigrants in Quebec. We found no evidence however that Anglophone-Francophone differences in interpregnancy intervals widened during the study.

Strengths and limitations

We had population-based data for more than 500 000 parous women in a large province of Canada, and used quantile regression, a method that estimated differences for both short and long interpregnancy intervals. There are nonetheless study limitations. The clinical impact of a few months difference in interpregnancy intervals is unknown, although effects at the population level may be significant. The results suggest that a change of only 1 month in the interpregnancy intervals of the Anglophone population could have a beneficial impact on maternal-infant health. Information on the delivery date for the first pregnancy was self-reported by the mother, and in some cases, may have been incorrectly recorded. Socioeconomic status and language were only available at the second delivery, and we do not know the extent to which these could have differed compared with the first birth. We could not adjust for maternal age, and cannot rule out residual confounding due to differences in maternal age between linguistic groups. We could not study bilingual or other language groups due to sample size limitations, or account for material deprivation as an area-level variable in a multilevel analysis. This study was limited by measures of socioeconomic status that were imperfect. We did not have information on household income, or any measure of socioeconomic status of the partner, and area deprivation is an ecological marker that may not reflect individual deprivation. We did not have information on abortion, immigration period, family planning, breastfeeding, contraception, or other characteristics potentially related to interpregnancy intervals.Footnote 5,Footnote 6,Footnote 22,Footnote 23 Finally, Quebec is a multicultural population where language does not necessarily reflect ethnicity, hence the results cannot be inferred to ethnic subgroups.

Conclusion

This study found evidence of differences in interpregnancy intervals between Anglophones and Francophones of Quebec. Disadvantaged minority Anglophones had unfavourable interpregnancy intervals compared with disadvantaged Francophones. These findings suggest that lingo-cultural differences in interpregnancy intervals may be present in Canada, and add to the growing evidence that socioeconomically disadvantaged Anglophones may be a vulnerable population in Quebec.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Health Canada via the McGill Training and Retention of Health Professionals Project; and a Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé career award (34695).

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

NA conceived and designed the study, and LL and MBB performed the statistical analysis with guidance from NA. ADB and AC helped interpret the results. NA, MBB and ADB drafted the manuscript, and LL and AC revised it for critical intellectual content. All authors approved the final version submitted.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.