At-a-glance – Supervised Injection Services: a community-based response to the opioid crisis in the City of Ottawa, Canada

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Sarah DelVillano, BAAuthor reference 1; Margaret de Groh, PhDAuthor reference 2; Howard Morrison, PhDAuthor reference 2; Minh T. Do, PhDAuthor reference 3Author reference 4Author reference 5

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.39.3.03

Author references:

- Author reference 1

-

Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 2

-

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 3

-

Health Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 4

-

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 5

-

Department of Health Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: Margaret de Groh, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1S 5H4; Tel: 613-614-2045; Email: Margaret.degroh@canada.ca

Abstract

In response to the current opioid crisis in Canada, establishing safe injection services (SIS) in high risk communities has become more prevalent. In November 2017, The Trailer opened in Ottawa, Canada and tracks client use, overdose treatment and overdoses reversed. We analyzed data collected between November 2017 and August 2018. During peak hours, demand for services consistently exceeded The Trailer’s capacity. Overdoses treated and reversed in this facility increased substantially during this period. Results suggest The Trailer provided an important though not optimal (due to space restrictions) harm reduction service to this high-risk community.

Keywords: supervised injection sites, supervised injection services, supervised consumption sites, harm reduction, addiction, opioids, naloxone

Highlights

- The Trailer (supervised injection service) was established as a response to the opioid crisis in Ottawa, Canada.

- The Trailer offers a 24-hour service to clients.

- Overdose reversals during the tracking period increased significantly.

- The demand for services has consistently exceeded capacity.

Introduction

Canada is currently in the midst of an opioid crisis.Footnote 1 From 2016 to 2017 apparent opioid-related deaths increased by 34% in Canada from 2978 to 3987.Footnote 2 This increase is largely attributed to the growing toxicity of the illegal drug supply.Footnote 2Footnote 3 Supervised injection services (SIS) represent one type of harm reduction method designed to mitigate the effects of opioid use.

According to recent systematic reviews,Footnote 4Footnote 5 community-based SIS have been found to reduce overdose mortality and morbidity among persons using SIS, increase harm reduction behaviours (decreased sharing and reuse of syringes), and increase initiation of substance use disorder treatment services. The SIS model has also been found to be cost-effective and to contribute to reducing pressure on community services, such as emergency medical services (EMS).Footnote 4Footnote 6 The establishment and operation of community-based SIS in Canada, however, remain a controversial harm reduction method.Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9

In November 2017, following a severe spike in deaths related to injection of opioids in the city of Ottawa, Canada, “The Trailer” was established; a SIS managed by Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc. (OICHI) and sanctioned by the Government of Canada. The Trailer is located in a high drug use area of Ottawa, with a catchment area that includes both shelters and treatment services for persons who use drugs in the community. This at-a-glance provides an overview of the clients and overdose treatments at The Trailer.Footnote 10

Methods

The Trailer is responsible for tracking services and providing quarterly results to the Ontario Provincial Government. The Trailer is also required to provide an Annual Report to Health Canada. Most results reported here are based on tracking results for November 2017 through August 2018 (August 2018 results are not available in the Annual Report).

The Trailer’s clients work with staff to establish an easy to remember unique identifier that is designed to maintain their anonymity, while also allowing their use of the SIS to be tracked.

The Trailer tracks several key data markers, including individual visits, types of drugs used (self-reported only), number of injections performed, overdoses, as well as observable health concerns (e.g., abscesses; wounds).

For overdoses, the type of treatment used is tracked. For clients showing signs of overdose and are breathing, oxygen/rescue breathing, and stimulation are used (“oxygen treatment”). If oxygen treatment only is used, then the overdose treatment is captured in this category. If the client is not breathing or is not responding to oxygen or stimulation, then naloxone is administered (“naloxone treatment”).

The experience of The Trailer is that many clients inject multiple (2-3 times) times per visit. While the number of injections is tracked, we have calculated the rate of overdose per 1000 visits, rather than per 1000 injections, as has been the approach in the past where most overdose events were linked to single injections.Footnote 11Footnote 12 This approach takes into consideration changing drug injection methods over time and therefore gives a better indication of overdose burden.

Results

Client profile

As of October 19, 2018, The Trailer had registered 1049 clients since its inception in November 2017 (OICHI personal communication, 2018). This number does not include clients who have died since November 2017 (six known deaths). Between November 2017 and August 2018, The Trailer provided services to an average of 226 different clients per month.Footnote 10 The OCIHI reported that their client base was relatively stable with an approximate 13% turnover per month.

Approximately three-quarters of clients identified as male and most (60%) were between 25 and 45 years old. 12% of clients reported they were between 18 to 25 years old.

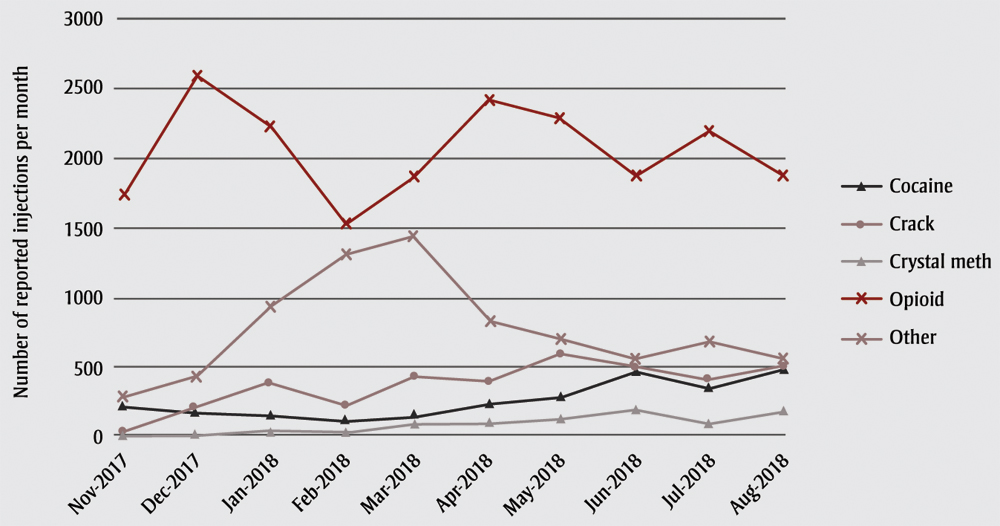

Opiates were by far the most common drug reported to be injected in The Trailer (Figure 1), though the reported use of opiates dropped from around 75% of all injections at the beginning of the tracking period to just over half by the end of the tracking period. The percentage who reported injecting cocaine or crack both increased slightly over time.

Figure 1. Injectable drugs reported used at The Trailer by month, November 2017–August 2018, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Data source: Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc. (OICHI), Report to Health Can SIS, November 2017-September 2018.10

Text Description

| Month | Number of reported injections per month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | Crack | Crystal meth | Opioid | Other | |

| Nov. 2017 | 234 | 20 | 1 | 1752 | 289 |

| Dec. 2017 | 184 | 216 | 19 | 2597 | 432 |

| Jan. 2018 | 155 | 381 | 39 | 2236 | 938 |

| Feb. 2018 | 110 | 229 | 27 | 1522 | 1310 |

| Mar. 2018 | 150 | 424 | 92 | 1869 | 1442 |

| Apr. 2018 | 232 | 401 | 102 | 2424 | 830 |

| May 2018 | 291 | 590 | 129 | 2298 | 698 |

| June 2018 | 477 | 505 | 190 | 1873 | 553 |

| July 2018 | 353 | 403 | 100 | 2208 | 683 |

| Aug. 2018 | 477 | 505 | 190 | 1873 | 553 |

Use of Supervised Injection Services

The Trailer provides a 24-hour service to clients. Table 1 provides the total number of individual visits per month to The Trailer and the average number of visits per day between November 2017 and August 2018. Originally expected to accommodate 60 to 80 visits per day, The Trailer actually averaged 121 visits per day. Demand was highest in the late afternoon and evening, and almost always exceeded injection booth availability. Therefore, during peak hours clients were required to wait outside for space to open inside the facility.

| Visits/treatments | Nov. 2017 | Dec. 2017 | Jan. 2018 | Feb. 2018 | March 2018 | April 2018 | May 2018 | June 2018 | July 2018 | Aug 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits per month | 3061 | 3171 | 4070 | 3435 | 3621 | 4129 | 3146 | 3626 | 3730 | 4192 |

| Average number of visits per day | 127.5Table 1 Footnote a | 102.3 | 131.3 | 122.8 | 116.8 | 138.0 | 101.5 | 120.9 | 120.3 | 135.2 |

| Overdoses treated with oxygen alone | 13 | 24 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 9 | 35 | 36 | 35 | 90 |

| Overdoses reversed with naloxone | 15 | 24 | 16 | 11 | 20 | 14 | 39 | 40 | 36 | 79 |

Data source: Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc. (OICHI), Report to Health Can SIS, November 2017-September 2018.10

|

||||||||||

Table 1 also provides the number of overdose treatments per month provided (either oxygen or naloxone) inside the facility. The number of overdoses that resulted in EMS calls were not included in these estimates. Approximately 0–2 overdoses per month resulted in EMS calls.

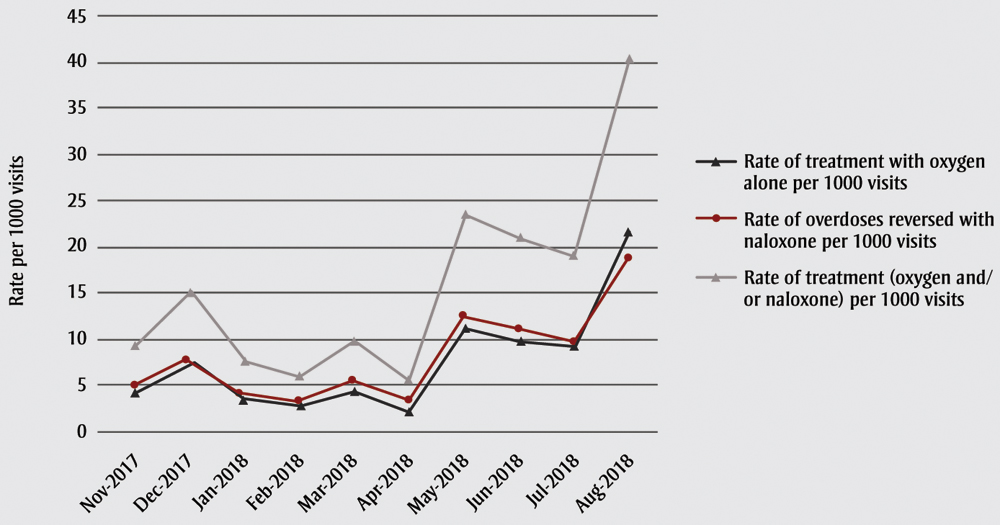

For most months, the type of treatment used was nearly equal with an overall monthly average of 29 oxygen and 28 naloxone treatments. Figure 2 provides the rate of overdose reversals per 1000 visits to The Trailer for each month for naloxone treatment, for oxygen treatment, and for both treatments combined. All trends are statistically significant. For naloxone treatment alone, the statistically significant (p < .05) linear trend indicates an increase of 5 naloxone reversals per month over the time period. OICHI reported (personal communication, 2018) that the overdose reversals during the tracking period (naloxone only) represented 112 unique clients.

Figure 2. Rates of overdose reversals by naloxone, treatment with oxygen alone and treatment with oxygen and/or naloxone, November 2017–August 2018, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Data source: Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc. (OICHI), Report to Health Can SIS, November 2017-September 2018.10

Note: The treatment with naloxone may be preceded by a treatment with oxygen that was insufficient to treat the overdose.

Text Description

| Month | Rate of treatment with oxygen alone per 1000 visits | Rate of overdoses reversed with naloxone per 1000 visits | Rate of treatment (oxygen and/or naloxone) per 1000 visits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nov. 2017 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 9.2 |

| Dec. 2017 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 15.2 |

| Jan. 2018 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 7.6 |

| Feb. 2018 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 6.1 |

| Mar. 2018 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 9.9 |

| Apr. 2018 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 5.6 |

| May 2018 | 11.1 | 12.4 | 23.5 |

| June 2018 | 9.9 | 11 | 21 |

| July 2018 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 19 |

| Aug. 2018 | 21.5 | 18.8 | 40.3 |

Discussion

The opioid crisis, fuelled by unpredictable and unprecedented toxic supplies of illegal street drugs, has led to an urgent need for supervised injection services. Location, accessibility and attitudes toward clients, however, can be critical to the success or failure of a SIS.Footnote 7Footnote 13 The Trailer has been able to meet the needs of many of its clients because it is located within the community in which it serves, is open 24-7, and has adopted a model that cultivates a safe space for its clients free of shame, thereby earning the trust necessary to introduce needed health and addiction services.Footnote 4Footnote 13Footnote 14 However, service needs at The Trailer during peak hours consistently exceeded capacity, which put clients who found it difficult to wait at risk of harm or death if they injected unsupervised. Although plans for a permanent site are on hold, a new trailer (The Trailer 1.5) opened in December 2018, which increased the number of injection booths from 8 to 12.

Safe injection services (SIS) help to ensure that, instead of potentially dying alone either at home or in public places, those who inject illegal drugs have a safe space in which unintended overdoses can be reversed. In some respect, a community SIS can be seen as the proverbial “canary in the coal mine”. It is an on the ground service that can signal the introduction of a toxic or “bad batch” of illegal street drugs in an area. Consequently, it is a spike in overdose reversals that alerts the community, instead of a spike in overdose deaths.

The growing toxicity of illegal drugs, driven by the introduction of ever-changing fentanyl analogues,Footnote 3Footnote 15 has complicated the way services are provided at The Trailer. For example, The Trailer staff has had to contend with increases in the number of overdoses treated. In addition, the spectrometer located at Ottawa’s Sandy Hill Centre has identified the presence of synthetic opioids in non-opiate drugs, such as crack cocaine and methamphetamines.Footnote 3 Consequently, the OICHI is now championing expanding their services to also provide a safe space for those who ingest drugs through inhalation (safe consumption services).Footnote 10

Strengths and limitations

The Trailer’s commitment to anonymity for its clients makes it very challenging to characterize this population in any detail. Locating The Trailer in a high drug use area, however, suggests that clients are likely similar to those who have utilized successful SIS in the past (e.g., long-term users; marginalized; lower contact with the health care system).Footnote 16Footnote 17 It was also not possible to assess the actual composition of drugs used, their impact on overdose events or the pattern of overdoses.

However, we were able to provide estimates of overdose burden, choosing to calculate overdose rates per 1000 visits. The changes in drug injection patterns, in our view, suggest that our approach provided a more comparable estimate with overdose burden estimates of the past, particularly for heroin where overdoses typically occur after one injection.Footnote 11Footnote 12 Although successful treatment with naloxone is often considered the formal definition of an “overdose reversed,” the burden associated with oxygen treatment has also been reported. It is not possible to determine how many of these cases would have resulted in an overdose requiring naloxone in the absence of oxygen treatment.

Finally, we were unable to determine whether clients used The Trailer for all their injections. Past studies have demonstrated that use of an established SIS is far from 100%.Footnote 16Footnote 18 This is likely the case for The Trailer’s clients, thereby leaving them at risk when they must wait for an injection booth and/or when they choose to inject in higher risk situations.

Conclusion

The number of opioid overdoses avoided or reversed due to oxygen or naloxone treatment has greatly increased over the short period since The Trailer was established. There is evidence that The Trailer during this period was unable to fully meet the needs of clients in the community.Footnote 10 Whether the new temporary trailer with an additional 4 booths can meet demand remains to be seen.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of XiaoHong Jiang to organizing the references for this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc. (OICHI) and Wendy Muckle, in particular for providing additional information for this manuscript and for giving permission to republish OICHI results.

Conflicts of interest

The first author (SDV) is a peer worker at The Trailer. The second author (MdG) was Acting Editor-in-Chief of this issue of the HPCDP Journal, but recused herself from taking any editorial decisions on this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions and statement

SDV, MdG and MTD conceived and outlined the paper and conducted the analyses. SDV, MdG and HM wrote the paper. All authors critically reviewed and provided revisions to all aspects of the paper.

Ethics approval: analyses were based on aggregate, publicly available data, and as such, REB approval was not required.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Orpana HM, Lang JJ, Baxi M, et al. Canadian trends in opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder from 110 to 2014 through the lens of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(6):234-43.

- Footnote 2

-

Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. National report: Apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (January 2016 to December 2017). Web-based Report. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/national-report-apparent-opioid-related-deaths-released-june-2018.html

- Footnote 3

-

Sandy Hill Community Health Centre. Drug Checking Results [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Sandy Hill Community Health Centre; 2018 [cited October 26, 2018]. Available from: https://www.shchc.ca/programs/oasis/drug-checking

- Footnote 4

-

Potier C, Laprevote V, Dubois-Arber F, et al. Supervised injection services: what has been demonstrated? A systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:48-68.

- Footnote 5

-

Kennedy MC, Karamouzian M, Kerr T. Public health and public order outcomes associated with supervised drug consumption facilities: a systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2017;14:161-83.

- Footnote 6

-

Madah-Amiri D, Skulberg AK, Braarud AC, et al. Ambulance-attended opioid overdoses: an examination into overdose locations and the role of a safe injection facility. Substance Abuse. 2018:1-6. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1485130.

- Footnote 7

-

Kerr T, Mitra S, Kennedy M C, and McNeil R. Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):28.

- Footnote 8

-

Thomson E, Lampkin H, Maynard R, et al. The lessons learned from the fentanyl overdose crises in British Columbia, Canada. Addiction. 2017;112:2068-9.

- Footnote 9

-

Bayoumi A, Strike C. Making the case for supervised injection services. The Lancet Commentary. 2016;387:1890-1.

- Footnote 10

-

Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc. Report to Health Can SIS [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Ottawa Inner City Health, Inc.; 2018 [cited October 1, 2018]. Available from: http://www.ottawainnercityhealth.ca/report-to-health-can-sis/

- Footnote 11

-

Roxburgh A, Darke S, Salmon AM, et al. Frequency and severity of non-fatal opioid overdoses among clients attending the Sydney Medically Supervised injection Centre. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;176:126-32.

- Footnote 12

-

Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Lai C, et al. Drug-related overdoses within a medically supervised safer injection facility. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17:436-41.

- Footnote 13

-

Collier R. Harm reduction is about providing safety for patients. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1154. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095489.

- Footnote 14

-

McNeil R, Small W. 'Safer environment interventions': a qualitative synthesis of the experiences and perceptions of people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:151-8.

- Footnote 15

-

Ontario HIV & Substance Use Training Program. Naloxone resistant fentanyl – caution needed about reports [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Ontario HIV & Substance Use Training Program; 2018. Available from: http://hklndrugstrategy.ca/wp-content/uploads/Naloxone-resistant-fentanyl-OHSUTP-Oct-2018.pdf

- Footnote 16

-

Health Canada. Vancouver's INSITE Service and Other Supervised Injection Sites: What Has Been Learned from Research? - Final Report of the Expert Advisory Committee on Supervised Injection Site Research. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2008. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/reports-publications/vancouver-insite-service-other-supervised-injection-sites-what-been-learned-research.html

- Footnote 17

-

KPMG. NSW Health: Further evaluation of the Medically Supervised Injecting Centre during its extended Trial period (2007-2011). Final report. Australia: KPMG; 2010. Available from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/aod/resources/Documents/msic-kpmg.pdf

- Footnote 18

-

Hadland SE, DeBeck K, Kerr T, et al. Use of a medically supervised injection facility among street youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:684-9.