Original quantitative research – Do demographic and socioeconomic characteristics underpin differences in youth smoking initiation across Canadian provinces? Evidence from the Canadian Community Health Survey (2015–2018)

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: November 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Thierry Gagné, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2; Annie Pelekanakis, MScAuthor reference footnote 3Author reference footnote 4; Jennifer L. O’Loughlin, PhDAuthor reference footnote 3Author reference footnote 4

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.11/12.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Jennifer O’Loughlin, Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Montréal, 7101 Avenue du Parc, Montréal, QC H3N 1X9; Tel: 514 890-8000 ext. 15858; Email: jennifer.oloughlin@umontreal.ca

Suggested citation

Gagné T, Pelekanakis A, O’Loughlin JL. Do demographic and socioeconomic characteristics underpin differences in youth smoking initiation across Canadian provinces? Evidence from the Canadian Community Health Survey (2015–2018). Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;42(11/12):457-65. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.11/12.01

Abstract

Introduction: Youth initiation may drive differences in smoking prevalence across Canadian provinces. Provincial differences in initiation relate to tobacco control strategies and public health funding, but have also been attributed to population characteristics. We test this hypothesis by examining the extent to which seven characteristics—immigration, language, family structure, education, income, home ownership and at-school status—explain differences in initiation across provinces.

Methods: We used data from 16 897 youth aged 12 to 17 years in the Canadian Community Health Survey collected from 2015 to 2018. To examine the proportion of provincial differences explained by population characteristics, we compared average marginal effects (AMEs) from partially and fully adjusted models regressing “having ever initiated” on province and other characteristics. We also tested interactions to examine differences in the association between population characteristics and initiation across provinces.

Results: Initiation varied from 4% in British Columbia to 10% in Quebec. Being born in Canada, speaking French, not living in a two-parent household, being in the lowest household income quintile, having parents without postsecondary education, living in rented accommodation and not being in school were each associated with initiation. Taking these results into consideration, the AME of residing in another province compared with Quebec was attenuated by between 3% and 9%. Family structure and household income were more strongly associated with initiation in the Atlantic region and Manitoba, but not in Quebec.

Conclusion: Differences in initiation between Quebec and other provinces are unlikely to be substantially explained by their demographic or socioeconomic composition. Reprioritizing tobacco control and public health funding are likely key in attaining the “tobacco endgame” across provinces.

Keywords: Canada, youth, smoking initiation, socioeconomic factors, Canadian Community Health Survey

Highlights

- Smoking initiation rates vary substantially across Canadian provinces and are highest in Quebec.

- Initiation is strongly associated with demographic (e.g. immigration) and socioeconomic (e.g.

household income) characteristics. - Differences in these characteristics, however, explained less than 10% of differences in initiation between Quebec and other provinces.

- The lack of an explanation based on demographic and socioeconomic composition highlights the need of a coordinated national strategy.

Introduction

In most countries, smoking is strongly geographically distributed, with differences potentially attributable to context (i.e. tobacco control legislation and enforcement) and composition (i.e. inhabitants’ characteristics). In Canada, Quebec has consistently had among the highest levels of smoking prevalence across the 10 Canadian provinces. Between 2001 and 2019, the prevalence declined from 30% to 17% in Quebec, but remained higher than in most other Canadian provinces (e.g. British Columbia: 21% to 11%; Ontario: 25% to 14%).Footnote 1 More Canadians who initiate their first cigarette do so after reaching the age of 18.Footnote 2 However, a study examining initiation and cessation rates in different age groups since the mid-2000s suggested that Quebec’s higher prevalence may be driven in part by a higher initiation rate among youth aged 12 to 17 years. While initiation to a first cigarette in this age group decreased at a similar pace across provinces over the past decade, it has remained consistently higher in Quebec (e.g. for past-year initiation: 5% in Quebec vs. 3% in the rest of Canada in 2017–2018).Footnote 3

Several mechanisms could underpin persistent differences in initiation across provinces. Tobacco control policies, including minimum age for legal access, tobacco tax rates and adequate enforcement of legislation, are likely key. According to federal regulations, the minimum legal age to purchase tobacco across Canada (including in Quebec) is 18, although Ontario, British Columbia and several of the Atlantic provinces have raised their minimum age to 19, and Prince Edward Island raised it to 21 in 2020.Footnote 4 This is relevant to youth initiation because increasing the minimum age to above 18 limits the number of young adults that minors can reach to access cigarettes.Footnote 5 Tobacco tax rates have been lowest in Quebec for decades, in part due to a tax reduction in the 1990s in response to anti-taxation lobbying and fears about increasing contraband activities.Footnote 6 While taxation increases have been relatively small across provinces over the past 15 years, persistent differences in taxation are likely to contribute to higher initiation rates, as cheaper cigarettes are more accessible to youth.Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9 For enforcement, although it is prohibited to sell or supply cigarettes to minors across Canada, the proportion of adolescents in Quebec who buy cigarettes in stores is higher than in other provinces. In 2010–2011, 36% of high school students who smoked reported buying cigarettes from stores in Quebec compared to 16% in British Columbia and 20% in Ontario.Footnote 10 Other relevant policy differences include smoke-free policies in public and private spaces, regulation of electronic cigarettes, and overall public health expenditure. In 2019, Quebec was second-last in the proportion of health expenditure spent on public health across provinces.Footnote 11

Differences in initiation rates across provinces may also relate to underlying population characteristics. In 1997, Wharry alluded to differences in language and culture, highlighting the failure of public health to adapt its tobacco control efforts to the francophones who are the majority in this province.Footnote 12 The extent to which these explanations are relevant in more recent years is unclear. In a study using 2016 data, adult smokers in Quebec were found to be more supportive of “endgame” tobacco legislation measures than in other provinces.Footnote 13

A second historical explanation considers socioeconomic factors. In 1998, Aubin and Caouette suggested that Quebec’s higher smoking prevalence related to its lower levels of income compared to other provinces.Footnote 14 Similar to many Western countries, inequalities in smoking by educational attainment, occupation and income have been identified among Canadians.Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 17 Supporting inequalities in initiation, one study found that between 1999 and 2011, lifetime initiation in those aged 20 to 24 was consistently more prevalent among those with less than a high school diploma.Footnote 17 Supporting this hypothesis in more recent years, Quebec has had the second-lowest median household income across provinces and the highest high school dropout rate among males.Footnote 18Footnote 19

Beyond differences in tobacco control policies, risk factors of initiation that may explain differences across provinces therefore can include cultural factors (e.g. immigration, language), parents’ circumstances (e.g. two-parent family, parental employment) and adolescents’ educational trajectory.Footnote 20

Although previous studies have investigated the role of population characteristics in explaining differences in adult smoking across jurisdictions in Canada and other countries, no study to date has done so regarding youth initiation across Canadian provinces. Chahine et al., exploring variation in adult smoking at different geographical levels in the United States, found that nine characteristics—age, sex, education, household income, employment and occupation, immigration, ethnicity, marital status, and household size—explained 41% of the variation in smoking at the state level.Footnote 21 Using a similar approach, Corsi et al. found that a similar set of characteristics explained 21% of the variation in smoking across Canadian provinces.Footnote 22 Beard et al. examined the contribution of age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status to differences across government office regions in England, and found that the magnitude of differences in smoking explained by these factors varied across comparison pairs: differences between the “South West” region and the three most Northern regions (North West, North East, and Yorkshire and the Humber) were completely attenuated when considering these characteristics, whereas differences between the South West and the Greater London region were not attenuated at all.Footnote 23 They also found that the association between these characteristics and smoking varied significantly across regions (e.g. socioeconomic inequalities in smoking were larger in the North of England than the rest of the country), suggesting that the role of differences in both prevalence and the association between population characteristics and smoking should be considered across jurisdictions.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to quantify the contribution of population characteristics to differences in youth initiation between the Canadian province with the highest prevalence of initiation—Quebec—and other provinces, using data from a nationally representative dataset of youth aged 12 to 17 collected between 2015 and 2018. The specific objectives were to: (1) describe the distribution of population characteristics (i.e. immigration, language, two-parent family, household income, household education, home ownership and at-school status) associated with initiation across provinces; (2) examine the extent to which differences in initiation between Quebec and other provinces vary as a function of differences in the prevalence of these characteristics; and (3) examine whether associations between population characteristics and initiation vary across Quebec and other provinces (i.e. to assess whether effect modification in these associations also contributes to explaining differences in initiation).

Methods

Data

We used data from four annual cycles (2015–2018) of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) public use microdata files (PUMF). CCHS is the largest repeat cross-sectional health survey in Canada. It collects data on health status, health care utilization and health determinants in the Canadian population annually. It incorporates a large sample designed to include 10 000 youth aged 12 to 17 every year and provide reliable estimates at the health region level (i.e. geographical units within provinces) every two years. The two-year national response proportion was 60% in 2015–2016 and 61% in 2017–2018. In total, 16 897 youth aged 12 to 17 were recruited across the 10 provinces between 2015 and 2018.

Statistics Canada releases survey weights and bootstrap replicate weights to ensure representative estimates of the Canadian population that consider the CCHS sampling design. A detailed description of the sampling methodology is available elsewhere.Footnote 24

In keeping with the 2014 Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement, this study did not require ethical review since the data are legally accessible to the public and appropriately protected by law.

Variables

We used “having ever smoked a whole cigarette” (yes, no) as a proxy for initiation. This was defined as: (1) self-identification as a smoker in the item “At the present time, do you smoke cigarettes daily, occasionally or not at all?”; (2) if not at all, agreeing with the item “Have you smoked more than 100 cigarettes (about 4 packs) in your life?” (yes, no); and (3) if not, agreeing with the item “Have you ever smoked a whole cigarette?” (yes, no).

Population characteristics were defined in seven variables: (1) immigration, (2) language, (3) family structure, (4) household income, (5) household education, (6) home ownership and (7) at-school status. “Immigration status” was coded by Statistics Canada based on the country of birth (born in Canada, not born in Canada). “Language” was coded based on the language most often spoken at home (English, French, other). To increase cell sizes across provinces, we included those reporting both French and English in the household in the French category. “Family structure” was based on data describing the nature of the relationship between respondents and other household members in a household grid questionnaire (living with two parents, living with one parent, other). The large majority (88%) of those in the “other” category represent youth living with one or two parents and other household members that are not siblings. These may include grandparents and other family members, nonfamily members, or participants’ own partner and/or children.

“Household education” was based on the highest level of education completed among household members (secondary education or less, postsecondary education completed). Notably, education systems vary across provinces, and Quebec has a unique postsecondary degree between high school and university (Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel; CEGEP). CCHS does not release data on the educational attainment of other household members, precluding us from distinguishing between parents with a university degree or lower postsecondary qualifications. “Household income” was coded by Statistics Canada using data on income, household size and community size into a decile ranking which represents a relative measure of household income compared to other households at the national level (living in a household in the bottom income quintile, not living in a household in the bottom income quintile). “Home ownership” was measured by asking whether the dwelling was owned by a household member (even if it was still being paid for) or rented (even if no cash rent was being paid) (owner, renter).

“At-school status” was based on the items “Last week, was your main activity working at a paid job or business, looking for paid work, going to school, caring for children, household work, retired or something else?” and “Are you currently attending school, college, CEGEP or university?” (attending school, not attending school). CCHS public-use files code all respondents aged 12 to 14 years to be attending school as a form of disclosure control. Missingness across variables is detailed in the supplementary material.

Models also controlled for age group (12–14, 15–17), sex (male, female) and cycle (2015–2016, 2017–2018).

Statistical analysis

To examine the extent to which initiation and population characteristics varied among youth aged 12 to 17 across provinces, we first described prevalence estimates in the full sample and in the provinces. To ensure sufficient cell sizes, we pooled the four provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador into a single “Atlantic” category (see sample sizes in the supplementary material).

To examine the extent to which population characteristics were related to initiation, we reported initiation across categories of population characteristics and unadjusted prevalence ratios (PR) using Poisson regression in the full sample.Footnote 25 To examine the extent to which population characteristics associated with initiation could explain differences in initiation across provinces, we then produced two models: a first “base model” regressing initiation on province of residence controlling for survey cycle only, and a second “fully adjusted model” also including age, sex and the seven population characteristics. We reported both the prevalence ratio and the average marginal effect (AME) in these models (i.e. the absolute difference between the average marginal probabilities estimated from these models).Footnote 26Footnote 27

Since regression estimates from logistic models may vary between models even when the added covariates are not associated with the predictor of interest (i.e. province of residence), we compared the PRs and AMEs between the partially and fully adjusted models to derive the proportion of differences in initiation between provinces that could be attributed to differences in population characteristics.Footnote 28Footnote 29

Finally, to test differences in the association of population characteristics with initiation across provinces, we added separate sets of interaction terms for each population characteristic after the fully adjusted model (see results in the supplementary material). We did not test the interaction for the language variable because too few youth spoke French at home in some provinces to reliably examine this. To better interpret models with significant interactions, we reported average marginal probabilities of initiation across the categories of population characteristics in each province.

Regression analyses were done in the complete-case sample of 15 252 participants (90.3% of full sample). All estimates were systematically adjusted for the CCHS survey weight and 1000 bootstrap replicate weights provided by Statistics Canada. All estimates were produced in Stata 16.Footnote 30 All supplementary files are uploaded on the Open Science Framework.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents the distribution of initiation and selected characteristics in the full sample and across Canadian provinces. Initiation of a first cigarette among youth averaged 6.9% (95% CI: 6.3–7.5) and varied significantly across provinces: it was highest in Quebec (10.2%; 95% CI: 8.8–11.6) and lowest in British Columbia (4.2%; 95% CI: 3.2–5.2). Population characteristics each varied across provinces except for at-school status (p = 0.130). Immigration status was highest in Alberta (17%) and lowest in the Atlantic region (3%). The prevalence of French as the language most spoken at home varied from 86% in Quebec to 2% in Alberta, whereas the prevalence of the “other” language category varied from 11% in Manitoba to 2% in the Atlantic region. The proportion living with two parents varied from 73% in Alberta to 67% in Ontario and British Columbia. The proportion with parents who completed postsecondary education varied from 87% in Quebec to 78% in Manitoba. The proportion of youth in the bottom household income quintile varied from 38% in Ontario to 17% in Saskatchewan. The proportion of youth out of school averaged 4% across provinces. While the global test for differences in at-school status was not significant, its proportion in Ontario (2.9%) was significantly lower compared with Quebec (4.5%) in post-hoc tests (p = 0.007).

| Characteristics | Full sample | British Columbia | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Quebec | AtlanticFootnote a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | W%Footnote b | |

| Sample size | 16 897 | 2275 | 2055 | 814 | 911 | 5117 | 3470 | 2255 |

| Initiation of a first cigarette | ||||||||

| Yes | 6.9 | 4.2 | 6.9 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 5.7 | 10.2 | 7.5 |

| Never | 93.1 | 95.8 | 93.1 | 90.1 | 93.4 | 94.3 | 89.8 | 92.5 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 12–14 | 50.6 | 50.8 | 50.4 | 51.2 | 49.0 | 51.0 | 50.2 | 50.4 |

| 15–17 | 49.4 | 49.2 | 49.6 | 48.8 | 51.0 | 49.0 | 49.8 | 49.6 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 51.3 | 51.4 | 51.3 | 51.6 | 51.5 | 51.3 | 51.2 | 51.4 |

| Female | 48.7 | 48.6 | 48.7 | 48.4 | 48.5 | 48.7 | 48.8 | 48.6 |

| Immigration status | ||||||||

| Not born in Canada | 13.4 | 14.6 | 16.8 | 10.4 | 20.9 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 2.9 |

| Born in Canada | 86.6 | 85.4 | 83.2 | 89.6 | 79.1 | 85.3 | 89.5 | 97.1 |

| Language most spoken at home | ||||||||

| English | 70.6 | 86.9 | 88.2 | 91.4 | 86.3 | 86.0 | 9.5 | 87.6 |

| French | 21.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 85.5 | 10.7 |

| Other | 8.0 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 6.2 | 11.0 | 9.1 | 5.0 | 1.7 |

| Family structure | ||||||||

| Living with both parents | 69.1 | 67.0 | 72.5 | 72.3 | 70.1 | 67.3 | 70.6 | 70.6 |

| Living with one parent | 20.4 | 20.5 | 17.8 | 20.0 | 18.8 | 20.5 | 22.0 | 20.5 |

| Other living arrangements | 10.5 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 11.1 | 12.1 | 7.4 | 8.8 |

| Household education | ||||||||

| Postsecondary not completed | 15.5 | 15.6 | 18.6 | 19.7 | 22.4 | 15.2 | 12.6 | 14.1 |

| Postsecondary completed | 84.5 | 84.4 | 81.4 | 80.3 | 77.6 | 84.8 | 87.4 | 85.9 |

| Household income | ||||||||

| In the bottom income quintile | 25.0 | 24.4 | 17.4 | 16.6 | 22.6 | 38.1 | 27.6 | 18.0 |

| Not in the bottom income quintile | 75.0 | 75.6 | 82.6 | 83.4 | 77.4 | 71.9 | 72.4 | 82.0 |

| Home ownership | ||||||||

| Owner | 79.1 | 76.6 | 82.2 | 80.4 | 83.9 | 79.6 | 74.7 | 86.6 |

| Renter | 20.9 | 23.4 | 17.8 | 19.6 | 16.1 | 20.4 | 25.3 | 13.4 |

| At-school status | ||||||||

| In school | 96.4 | 96.5 | 96.0 | 95.3 | 95.9 | 97.1 | 95.5 | 96.1 |

| Not in school | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

Explaining differences in youth initiation across Canadian provinces

Table 2 presents the prevalence of initiation and unadjusted PRs across population characteristics in the full sample. These were each associated with the risk of initiation. Being born in Canada was associated with a 126% higher risk of initiation. Compared to English, speaking French at home was associated with a 48% higher risk of initiation, whereas speaking another language at home was associated with a 51% lower risk of initiation. Compared with living with both parents, living with one parent was associated with a 76% higher risk of initiation. Having parents who did not complete postsecondary education was associated with a 54% higher risk of initiation. Living in a household in the bottom income quintile was associated with a 28% higher risk of initiation and living in a rented dwelling was associated with a 54% higher risk of initiation. Finally, not being at school was associated with a 266% higher risk of initiation.

| Sample characteristics | Initiation W% |

Unadjusted PR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| National prevalence | 6.9 | n/a | n/a |

| Immigration status | |||

| Not born in Canada (ref) | 3.3 | n/a | n/a |

| Born in Canada | 7.5 | 2.26 | 1.50–3.41 |

| Language most spoken at home | |||

| English (ref) | 6.5 | n/a | n/a |

| French | 9.6 | 1.48 | 1.23–1.77 |

| Other | 3.2 | 0.49 | 0.30–0.80 |

| Family structure | |||

| Living with both parents (ref) | 5.9 | n/a | n/a |

| Living with one parent | 10.3 | 1.76 | 1.44–2.15 |

| Other living arrangements | 6.8 | 1.16 | 0.89–1.51 |

| Household education | |||

| Postsecondary completed (ref) | 6.4 | n/a | n/a |

| Postsecondary not completed | 9.9 | 1.54 | 1.28–1.86 |

| Household income | |||

| Not in the bottom income quintile (ref) | 6.4 | n/a | n/a |

| In the bottom income quintile | 8.2 | 1.28 | 1.06–1.55 |

| Home ownership | |||

| Owner (ref) | 6.2 | n/a | n/a |

| Renter | 9.6 | 1.54 | 1.27–1.86 |

| At-school status | |||

| In school (ref) | 6.2 | n/a | n/a |

| Not in school | 22.8 | 3.66 | 2.76–4.84 |

Table 3 presents the PRs of the association between province of residence and initiation in the complete-case sample, using Quebec as the reference category. In the base model, Saskatchewan was the only province with a nonsignificant lower risk of initiation (PR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.67–1.28). Comparing AMEs across models, the absolute differences across provinces increased by 2% for the Atlantic region (i.e. 3.44/3.36) and decreased by between 3% and 9% for Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia when including the population characteristics. The increase in the Atlantic region may be attributable to differences in demographic characteristics less common in this region compared with Quebec (i.e. being born outside Canada, speaking another language at home). The decrease in differences with other provinces may include both differences in (1) demographic variables (i.e. Quebec had relatively fewer immigrants, more French-speaking youth and fewer speaking another language at home) and (2) socioeconomic variables (i.e. Quebec had relatively more youth living in low-income households and in rented accommodation, and more who were not in school).

| Variables | Model 1 Base model |

Model 2 Full model |

Relative change in AMEs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | AME | PR | 95% CI | AME | % | |

| Province (ref: Quebec) | |||||||

| British Columbia | 0.39 | 0.29–0.52 | −6.48 | 0.40 | 0.26–0.61 | −6.25 | 3.5 |

| Alberta | 0.66 | 0.51–0.85 | −3.61 | 0.68 | 0.45–1.04 | −3.28 | 9.1 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.92 | 0.67–1.28 | −0.81 | 0.88 | 0.56–1.39 | −1.24 | −53.1 |

| Manitoba | 0.60 | 0.40–0.88 | −4.25 | 0.62 | 0.38–1.02 | −3.98 | 6.4 |

| Ontario | 0.54 | 0.42–0.87 | −4.80 | 0.55 | 0.38–0.80 | −4.65 | 3.1 |

| AtlanticFootnote a | 0.68 | 0.54–0.87 | −3.36 | 0.67 | 0.46–0.98 | −3.44 | −2.4 |

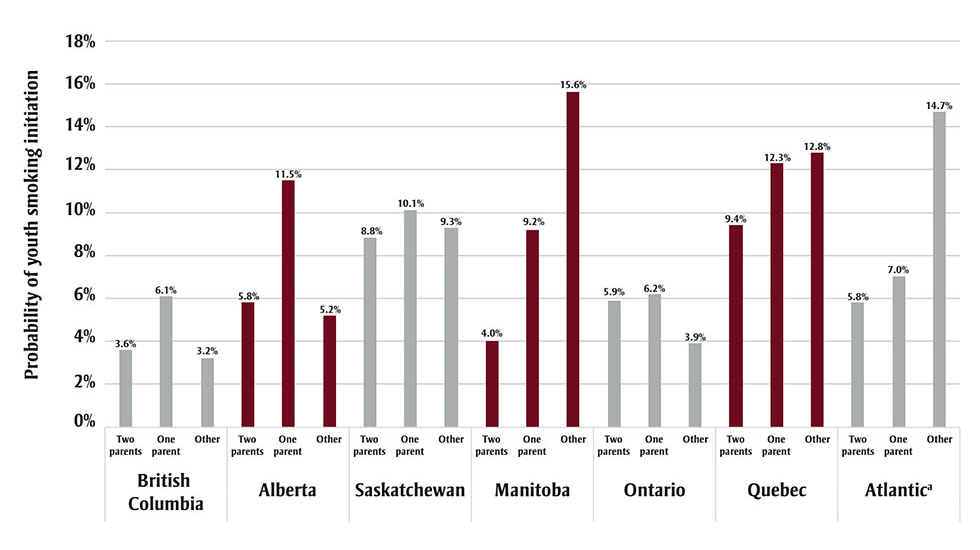

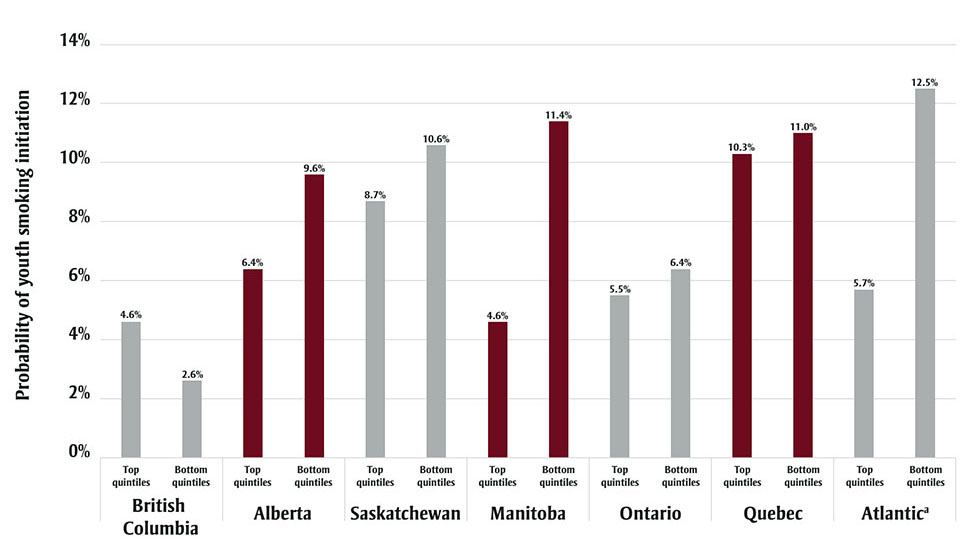

Testing differences in the association of population characteristics with initiation across provinces, we found that the strength of the association with initiation differed across provinces for two characteristics: family structure (p = 0.022) and household income (p = 0.028). Figures 1 and 2 report the average marginal probabilities (i.e. adjusted for other covariates) of initiation across family structure categories and across household income categories, respectively. Compared with living with two parents, the association of living with one parent with initiation was higher in Manitoba (relative difference = 2.30), Alberta (1.98) and British Columbia (1.68), and the association of living in other arrangements with initiation was higher in the Atlantic region (2.53) and Manitoba (3.90). Compared with those in the four highest income quintiles, the association between living in the bottom income quintile and initiation was higher in the Atlantic region (rel. diff. = 2.19), Manitoba (2.48) and Alberta (1.50).

Figure 1 - Text description

| Provinces | Full model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Two parents % | One parent % | Other % | |

| Quebec | 9.4 | 12.3 | 12.8 |

| Atlantic | 5.8 | 7.0 | 14.7 |

| Ontario | 5.9 | 6.2 | 3.9 |

| Manitoba | 4.0 | 9.2 | 15.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 8.8 | 10.1 | 9.3 |

| Alberta | 5.8 | 11.5 | 5.2 |

| British Columbia | 3.6 | 6.1 | 3.2 |

Abbreviations: CCHS, Canadian Community Health Survey; PUMF, public use microdata file.

a Atlantic region: New Brunswick, Nova

Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Figure 2 - Text description

| Provinces | Full model | |

|---|---|---|

| Top four quintiles % | Bottom quintile % | |

| Quebec | 10.3 | 11.0 |

| Atlantic | 5.7 | 12.5 |

| Ontario | 5.5 | 6.4 |

| Manitoba | 4.6 | 11.4 |

| Saskatchewan | 8.7 | 10.6 |

| Alberta | 6.4 | 9.6 |

| British Columbia | 4.6 | 2.6 |

Abbreviations: CCHS, Canadian Community Health

Survey; PUMF, public use microdata file.

a Atlantic region: New Brunswick, Nova

Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Discussion

The prevalence of smoking has consistently been higher in Quebec than in the rest of Canada, with differences driven in part by higher youth initiation rates in Quebec.Footnote 3 In our study, initiation of a first cigarette among adolescents varied substantially across Canadian provinces, with Quebec’s estimate being 79% higher than that of Ontario and 143% higher than that of British Columbia. We examined the extent to which demographic and socioeconomic factors underpinned these differences and observed two key findings.

First, whereas each population characteristic studied varied across provinces, collectively these differences did not explain a large proportion of the variability in initiation between Quebec and the other provinces. This contrasts with previous work in adult populations, which suggests that a meaningful proportion of regional differences in smoking prevalence was explained by these characteristics.Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23 It may be that the role of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics becomes more important in adulthood, as inequalities in smoking increase across the stages of progression to established smoking.Footnote 31 Beyond what was available in the CCHS, other measures such as food insecurity might have yielded a stronger portrait of adolescents’ socioeconomic circumstances across provinces.Footnote 32

Alternatively, some of the variability in youth initiation could also be explained by other social and cultural characteristics, such as self-imposed smoking bans in the household and antismoking social norms, that were not captured by the population characteristics studied.Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 33 These mechanisms may be assessed by exploring provincial differences in smoking permissiveness and exposure to second-hand smoke at home and in public spaces, perceived stigma and other smoking-related social norms and general dispositions towards risk-taking behaviour.

Second, whereas we found differences in the associations between initiation and each of family structure and household income across provinces, the effect-modification hypothesis also did not contribute to explaining the higher prevalence of smoking initiation in Quebec compared to other provinces. However, we warn that our sample size precluded us from reliably testing differences in the role of language spoken at home in initiation across provinces, despite it being a potentially meaningful factor for understanding Quebec’s higher initiation rate.

Specifically, our findings indicated that adolescents who were not living with two parents or were living in a household in the bottom income quintile were more likely to initiate a first cigarette if they lived in the Atlantic region and Manitoba (compared to Quebec or other provinces). In England, Beard et al. found that among adults, the association between socioeconomic status and smoking was stronger in more deprived regions.Footnote 23 Possible explanations included that more deprived areas had: (1) fewer public health services, necessitating that smokers use their own resources to quit smoking; (2) more positive smoking-related social norms that promote the modelling of other smokers’ behaviour; and (3) a higher prevalence of other behaviours associated with smoking, such as alcohol consumption.

Supporting this in Canada, we found that inequalities were larger in the four provinces with the lowest gross domestic product (GDP) value per capita, that is, three Atlantic provinces (Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) and Manitoba (comparatively, Quebec is the fifth-poorest province based on this indicator). While this may not explain Quebec’s disadvantage, the findings do suggest that the association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with initiation varies across jurisdictions and may be stronger in the poorest regions. These regions may therefore benefit particularly from prioritizing the reduction of inequalities in youth initiation.

Strengths and limitations

This study builds on the large sample and methodological strengths of the Canadian Community Health Survey to provide representative estimates of youth initiation across Canadian provinces. The cross-sectional design precludes establishing the temporality of associations, preventing causal inference statements. It is also possible that the measure of lifetime initiation captured cohort effects that differed across provinces over the previous two decades. Statistics Canada public use files limit release of data on residential information, so characteristics such as urbanicity and area deprivation could not be investigated. Other variables that could not be investigated include alcohol consumption, illicit drug use and e-cigarette use, since data on these variables were not systematically collected from all minors in the CCHS 2015–2016 and 2017–2018 cycles.

Conclusion

Although smoking prevalence has decreased over time, continued efforts are needed to sustain this decline. An under-investigated realm is identifying factors underpinning variability in smoking prevalence across Canadian provinces, which could guide or redirect tobacco control efforts. Our findings are among the first to suggest that, although youth differ across provinces in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, these differences are unlikely to be a key reason why youth in the province with the highest smoking initiation rate are more likely to initiate a first cigarette compared to other provinces. New research directions include replicating these findings using a longitudinal design, corroborating whether the predictors of initiation across provinces are also predictors of the transition from initiation to the sustained use of cigarettes, and exploring the contextual factors that actually drive these provincial differences using techniques such as multilevel modelling. Although our results cannot lead directly to intervention, they offer clear direction for future research (i.e. to confirm the benefits of new tobacco strategies to be implemented) and tobacco control action (i.e. to coordinate advocacy around stronger tobacco control strategies) in provinces with higher smoking initiation rates, at least in the Canadian context.

Acknowledgements

TG is a Banting Postdoctoral Fellow and was funded by fellowship awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQS) during this project. JOL holds a Canada Research Chair in the early determinants of adult chronic disease.

Conflicts of interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

TG designed the study, prepared the data, performed the analyses, interpreted the results, drafted the first version of the manuscript and contributed to the final version; AP and JOL each contributed to the first draft and final version of the manuscript. All authors have significantly contributed to the manuscript and agreed to its submission.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.