At-a-glance – Conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Op LASER study

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: February 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Deniz Fikretoglu, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Megan Thompson, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Tonya Hendriks, MAAuthor reference footnote 1; Anthony Nazarov, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2Author reference footnote 3; Kathy Michaud, PhDAuthor reference footnote 4; Jennifer Born, MScAuthor reference footnote 4; Kerry A. Sudom, PhDAuthor reference footnote 4; Stéphanie Bélanger, PhDAuthor reference footnote 5; Rakesh Jetly, MDAuthor reference footnote 6

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.3.03

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Health and Department of National Defence, 2022

Author references

Correspondence

Deniz Fikretoglu, Defence Research and Development Canada, Toronto Research Centre, 1133 Sheppard Ave. West, Toronto, ON M3K 2C9; Tel: 416-635-2049; Email: Deniz.Fikretoglu@drdc-rddc.gc.ca

Suggested citation

Fikretoglu D, Thompson M, Hendriks T, Nazarov A, Michaud K, Born J, Sudom KA, Bélanger S, Jetly R. Conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Op LASER study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(3):100-3. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.3.03

Abstract

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) deployed 2595 regular and reserve force personnel on Operation (Op) LASER, the CAF’s mission to provide support to civilian staff at long-term care facilities in Ontario and in the Centres d’hébergement de soins de longue durée in Quebec. An online longitudinal survey and in-depth virtual discussions were conducted by a multidisciplinary team of researchers with complementary expertise. This paper highlights the challenges encountered in conducting this research and their impact on the design and implementation of the study, and provides lessons learned that may be useful to researchers responding to similar public health crises in the future.

Keywords: military personnel, mental health, moral injury

Highlights

- There are a number of challenges involved in conducting longitudinal research in an applied military setting during a global public health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

- These challenges include but are not limited to a sudden transition to a distributed remote work environment, tight timelines, the need to obtain approvals from different agencies and departments, having to prioritize multiple study objectives, and survey fatigue.

- To overcome these challenges in future public health crises, it is important to (1) develop and maintain collaborative networks across government, academia and industry; (2) develop a standard set of pre-deployment demographic and health indicators to establish a baseline; and (3) use mixed methods approaches for a richer understanding of mental health trajectories following stressful events.

Introduction

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) deployed 2595 regular and reserve force personnel to support civilian staff at long-term care facilities (LTCF) and Centres d’hébergement de soins de longue durée (CHSLD) in Ontario and Quebec as one component of Operation (Op) LASER. The Op LASER deployment involved noncombat deployment experiences that can be associated with decreases in psychological well-being,Footnote 1 including short-notice deployment, quickly developed training, uncertain deployment roles and end dates, working extremely long hours over multiple days and, for some, being away from family, which past CAF research has shown accounted for most of the burden of mental illness.Footnote 2 Op LASER to LTCF and CHSLD also involved novel stressors, including the risk of exposure to a largely unknown, highly contagious virus (i.e. COVID-19), and for many personnel, working with vulnerable and ill elderly populations.Footnote 3Footnote 4 Indeed, CAF Op LASER reportsFootnote 5Footnote 6 documented military personnel witnessing some residents being handled roughly, being denied food or not being fed properly, as well as extensive staffing shortages and problems and significant infection control issues.

Given the extraordinary nature of this operation, the CAF Surgeon General and Chief of Military Personnel requested research support to (1) understand the impact of this mission on the mental health and well-being of Op LASER personnel; (2) assess operational recovery; and (3) identify the risk and resilience factors that may affect the impact of this mission on mental health and well-being. Findings would inform preparation, training and support for similar missions—especially important as public health and infectious disease experts predict future pandemics.Footnote 7

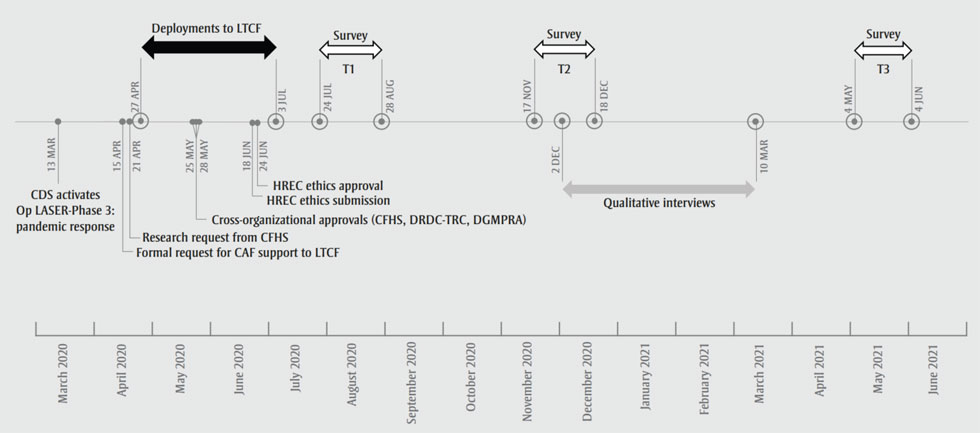

This research request was addressed via an online longitudinal survey and in-depth virtual discussions (Figure 1) conducted by a multidisciplinary team of researchers from Defence Research and Development Canada—Toronto Research Centre, Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (DGMPRA), Canadian Forces Health Services Group, Royal Military College of Canada, and HumanSystems Inc., with complementary expertise in mental health, including moral injury, and organizational psychology. This paper briefly highlights the challenges we encountered and the impact of these challenges on the design and implementation of our study, and provides lessons learned that may be useful to researchers responding to similar missions in the future.

Figure 1 - Text description

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| March 13, 2020 | CDS activates Op LASER-Phase 3: Pandemic response |

| April 15, 2020 | Formal request for CAF support to LTCF |

| April 21, 2020 | Research request from CFHS |

| April 27, 2020 – July 3, 2020 | Deployments to LTCF |

| May 25, 2020 & May 28, 2020 | Cross organizational approvals (CFHS, DRDC-TRC, DGMPRA) |

| June 18, 2020 | HREC Ethics submission |

| June 24, 2020 | HREC Ethics approval |

| July 24, 2020 – August 28, 2020 | Survey T1 |

| November 17, 2020 – December 18, 2020 | Survey T2 |

| December 2 , 2020 – March 10, 2021 | Qualitative Interviews |

| May 4, 2021 – June 4, 2021 | Survey T3 |

Abbreviations: CAF, Canadian Armed Forces; CDS, Chief

of Defence Staff; CFHS, Canadian Forces Health Services; DGMPRA, Director

General Military Personnel Research and Analysis; DRDC-TRC, Defence Research

and Development Canada — Toronto Research Centre; HREC, Human Research Ethics

Committee; LTCF, long-term care facility.

Notes: Survey data were collected over multiple points

(T1–T3) to allow for longitudinal analysis. Positive and negative mental health

outcomes, moral distress, moral injury, moral injury outcomes, coping and

social support were repeated at all three timepoints to assess long-term

impacts of Op LASER, while demographic and military characteristics and

help-seeking for mental health concerns were included only in one or two time-point(s),

as appropriate.

Challenges

1. Sudden transition to a distributed, remote work environment to comply with recommended public health measures

The key challenge was designing and implementing our study during a pandemic, while transitioning to a distributed, remote work environment. Initially, access to infrastructure, software and hardware, and other tools for sharing information across multiple organizations was not ideal, with limited guidance around best practices, although Department of National Defence (DND) Information Technology Support services worked very hard to facilitate this transition. Team members also had to juggle care of their dependents, overseeing virtual learning of their school-aged children, and other responsibilities while supporting the study requirements.

2. Tight timelines

The short span of time between the provincial requests for military support to LTCFs and the start of Op LASER meant that the study had to be designed and implemented very quickly (Figure 1). Indeed, as the research team was still working to obtain organizational approvals, the military client informed the research team that the first wave of Op LASER personnel sent to the LTCFs would be completing their deployment within a week or two. The fact that the information requested on the mental health and well-being of Op LASER personnel had to be collected right away contributed to additional time pressures.

3. Levels of approval across organizations

Our team members belong to multiple organizations, each with its own process of project approval and funding and resource allocation. Usually, during program formulation and project planning, sufficient time, i.e. up to a few months, is set aside to obtain all organizational approvals (i.e. client, organizational, funding, ethics review and public opinion researchFootnote *). For the Op LASER study, these approvals had to be obtained within a matter of weeks.

4. Need for virtual platform

Given the active community transmission of a new infectious disease, both the survey and the discussions had to be implemented virtually. Virtual platforms meeting or exceeding government and DND security directives to protect sensitive personal and health data had to be quickly identified and implemented. This particularly delayed the development of the discussion methodology by several weeks.

5. Prioritizing multiple study objectives

The request from the Surgeon General and the Chief of Military Personnel had several components, encompassing multiple outcomes and numerous risk and resilience factors operating at multiple (individual, team and organizational) levels. Research suggests there may be greater response burden (and higher dropout towards the end) for longer surveys.Footnote 8 Hence, measuring multiple constructs within a reasonable survey length posed challenges.

6. Operational demands that may necessitate less than optimal study design

High operational tempo related to the mission delayed the obtaining of demographic information for the full cohort from administrative databases to inform a probability sampling strategy. This delay necessitated the use of poststratification weighting methods that may be less robust in controlling for nonresponse bias.

7. Baseline indicators

Ideally, to obtain a measure of the positive or negative mental health impact of Op LASER, our team would have measured and controlled for baseline mental health prior to the start of the mission. Unfortunately, the short timelines made this impossible. The lack of baseline measures prevented us from linking observed negative health outcomes to the stressors of Op LASER in a more definitive manner and limited our ability to identify different trajectories of health and ill-health that may require different supports.Footnote 9

8. Survey dissemination and reach

While the list of names and email addresses of military personnel provided to us was close to complete, 13% of the e-mail addresses were organizational (Defence Wide Area Network) email addresses that are less accessible to part-time (Class A) military members. After Op LASER, many military members who participated in the mission took leave, went on training or deployed to other missions; many reservists returned to civilian life, which may have limited our ability to reach them or their willingness or availability to respond.

9. Survey fatigue/low response rates/respondent retention

Several factors may have further impacted survey response and retention rates. Our first survey was launched soon after another DND-wide survey (the COVID-19 Defence Team Survey) concluded; survey fatigue potentially reduced response rates. Military personnel may have been too fatigued or emotional to revisit their experiences by participating in our first survey soon after their deployment ended. Repetition of key measures across three assessment points may have reduced retention rates. Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) surveys had response rates of approximately 42% and 23%, respectively. T1 and T2 samples were representative of deployment province but not military rank, with junior non-commissioned members (NCMs) underrepresented. Ongoing analyses are exploring representativeness based on additional demographic and military variables using administrative data. These analyses will culminate in poststratification weighting to correct for sampling bias. At T1 and T2, participants were mostly male, mostly of junior NCM rank and evenly split between regular forces and reservists. Twice as many participants had deployed to Quebec as had deployed to Ontario.

Of note, response rates for the discussions exceeded expectations: we received expressions of interest from 200 personnel. We invited 52 of these to participate in a 60-minute, semi-structured discussion. Discussion participants were selected to be representative on key characteristics (i.e. Op LASER role, gender, rank, province). On average, discussions lasted 90 minutes.

Lessons learned

During the course of this study, we learned three important lessons that can be applied to future research.

1. Existing capability and established collaborative networks facilitate timely design and implementation of research

Our research organizations have a history of collaborative projects, which greatly facilitated the formation of a multidisciplinary study team with complementary areas of expertise. A strong capability in online survey programming and implementation in one of our organizations (DGMPRA) facilitated the online survey’s timely launch. Still, institutionalizing ways to minimize organizational approvals would facilitate timely study design and implementation in similar missions in future.

2. Developing a standard set of pre-deployment demographic and health indicators facilitates timely research design, data collection, interpretation and generalization

It may also be useful to explore developing a standard set of pre-deployment demographic and health indicators that could be collected in parallel to, or as part of, standard deployment readiness verification processes (e.g. Deployment Assistance Group screening). These indicators could then be accessed as a baseline for short-fuse research such as Op LASER.

3. Using mixed methods approaches facilitates gathering richer information and developing more robust recommendations

Quantitative data obtained with surveys give an indication of how individuals are doing, and are usually very appealing to senior military leadership. One-on-one discussions provide additional depth and context, although they take longer, as does transcription, translation, coding and analysis.

Conclusion

In this paper, we briefly summarized the challenges we encountered in designing and implementing the Op LASER research project in the midst of a pandemic. Some of these challenges were common to research in applied military settings whereas others were unique to the COVID-19 context.

Our experience in trying to overcome these challenges under very tight time constraints while respecting public health measures highlights several key recommendations, including the importance of (1) developing and maintaining robust collaborative networks across government, academia and industry; (2) having simplified and streamlined and harmonized processes for organizational approvals of research requiring quick implementation; and (3) using mixed methods approaches for a richer understanding of trajectories of good health and ill-health following stressful events. Investing in improvements in these key areas will benefit future research efforts to support the mental health and well-being of military personnel.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Bryan Garber for his support and contributions to the development of the Op LASER research project. Funding for this research was provided by the Department of National Defence (DND).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

DF: drafting and revising paper; MMT: drafting and revising paper; KM: editing and revising paper; TH: editing and revising paper; AN: editing and revising paper; JB: editing and revising paper; KS: editing and revising paper; SB: editing and revising paper; RJ: review of paper.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.