Evidence synthesis – Benchmarking unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada: a scoping review

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: August 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Monique Potvin Kent, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Farah Hatoum, MPHAuthor reference footnote 2; David Wu, BMScAuthor reference footnote 3; Lauren Remedios, BScAuthor reference footnote 1; Mariangela Bagnato, BHScAuthor reference footnote 1

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.8.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Monique Potvin Kent, School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, 600 Peter Morand, Room 301J, Ottawa, ON K1G 5Z3; Tel: 613-562-5800 ext. 7447; Email: monique.potvinkent@uottawa.ca

Suggested citation

Potvin Kent M, Hatoum F, Wu D, Remedios L, Bagnato M. Benchmarking unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada: a scoping review. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(8):307-18. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.8.01

Abstract

Introduction: Unhealthy food and beverage marketing in various media and settings contributes to children’s poor dietary intake. In 2019, the Canadian federal government recommended the introduction of new restrictions on food marketing to children. This scoping review aimed to provide an up-to-date assessment of the frequency of food marketing to children and youth in Canada as well as children’s exposure to this marketing in various media and settings in order to determine where gaps exist in the research.

Methods: For this scoping review, detailed search strategies were used to identify relevant peer-reviewed and grey literature published between October 2016 and November 2021. Two reviewers screened all results.

Results: A total of 32 relevant and unique articles were identified; 28 were peer reviewed and 4 were from the grey literature. The majority of the studies (n = 26) examined the frequency of food marketing while 6 examined actual exposure to food marketing. Most research focussed on children from Ontario and Quebec and television and digital media. There was little research exploring food marketing to children by age, geographical location, sex/gender, race/ethnicity and/or socioeconomic status.

Conclusion: Our synthesis suggests that unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents is extensive and that current self-regulatory policies are insufficient at reducing the presence of such marketing. Research assessing the frequency of food marketing and preschooler, child and adolescent exposure to this marketing is needed across a variety of media and settings to inform future government policies.

Keywords: obesity, children, adolescents, food marketing, food environment, Canada, policy, self-regulation

Highlights

- The frequency of food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada is ubiquitous. Although children’s actual exposure to unhealthy food marketing exists in different media, the evidence base is limited.

- Most research focusses on frequency of exposure, children from Ontario and Quebec, and television and digital media.

- Research is needed to examine the frequency of food marketing and pre-schoolers’, children’s and adolescents’ exposure to the marketing by geographical location, media and target population.

Introduction

Child obesity in Canada has increased significantly over the last four decades, with approximately 14% of Canadian children living with obesity.Footnote 1 This trend is mirrored globally, with the prevalence of child obesity increasing more than eight-fold over the last 40 years.Footnote 2 Poor dietary quality is a contributing factor to obesity, and Canadian children are struggling to meet the dietary recommendations set by Canada’s food guide.Footnote 3 Recent studies have found that Canadian children’s dietary intake is low in fruits and vegetables and high in sugar, sodium and saturated fats.Footnote 3Footnote 4

Children’s poor dietary intake is associated with unhealthy food and beverage marketing (hereafter referred to as food marketing).Footnote 5 Marketing is defined by the World Health Organization as “any form of commercial communication or message that is designed to, or has the effect of, increasing the recognition, appeal and/or consumption of particular products and services.”Footnote 6 Children are exposed to food marketing in a variety of media, such as television, digital media and product packaging, and in schools and other spaces where they gather.Footnote 7

The impact of food marketing is recognized as a function of both the exposure and power of the advertisements.Footnote 6 Exposure refers to the reach, frequency (also known as potential exposure) and impact of the message, while power refers to the content, design and execution of the message.Footnote 6 Frequency, or potential exposure, includes all advertisements on a specific medium that an individual may view, while actual exposure covers all advertisements actually viewed by an individual, as measured through self-reported methods or, more accurately, using measured media data or eye-tracking technology.Footnote 8

Children are especially vulnerable to the persuasive marketing techniques used in food marketing because they often lack the cognitive skills needed to understand the intent of marketing.Footnote 9 Furthermore, the products marketed to children are typically nutrient poor and energy dense.Footnote 10

In Canada, food marketing is primarily self-regulated by Ad Standards and the food and beverage industry through the Canadian Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CAI).Footnote 11 In the province of Quebec, food marketing to children less than 13 years old has been prohibited since 1980 under the Consumer Protection Act (CPA).Footnote 12 Previous scoping review evidence describing the impact of these food marketing regulations noted minimal improvement associated with the CPA in the power and frequency of food marketing to children in Quebec, and that loopholes in the CPA remain.Footnote 7 Elsewhere in Canada, no positive changes to food marketing were observed as a result of the CAI.Footnote 7

As a result of the ineffectiveness of current regulations in Canada, Bill S-228, designed to prohibit food marketing targeting children under 13 years old, was introduced into the Senate of Canada in 2016.Footnote 13 Although this bill was passed by the House of Commons and the Senate, it did not receive final approval by the Senate before the dissolution of Parliament in 2019. In December 2019, the Prime Minister’s Mandate Letter to the Minister of Health once again recommended the introduction of new restrictions on food marketing to children in Canada.Footnote 7 Given that food marketing regulations are forthcoming, it is necessary to benchmark current levels of children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing in a variety of media and settings. Such research can serve as essential baseline data for any future policy evaluations.

The most recent review of the evidence regarding food marketing to children in Canada assessed English language research published between January 2000 and September 2016.Footnote 7 ProwseFootnote 7 found the evidence base for children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing to be limited to television and product packaging. Moreover, the review concluded that Canadian regulations did not reduce children’s exposure to or the power of food marketing.Footnote 7 Although traditional media platforms such as television remain popular,Footnote 14 the growth of digital media usageFootnote 15 raises concerns over the various ways children may be exposed to food marketing.Footnote 7 The observed increases in screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic also contribute to children’s risk of exposure.Footnote 16 As such, examining food marketing to children on digital media and other nontraditional settings, in addition to traditional media, has become a point of research focus.

The purpose of our review was to provide an up-to-date assessment of the English and French language research on Canadian children’s exposure to food marketing in various media to determine where future research is needed. The objectives of this review are to explore the frequency (potential exposure) and actual exposure to food and beverage marketing by target population and its diversity, media and geographical distribution.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature published between October 2016 and November 2021. As described by Arksey and O’Malley,Footnote 17 the use of scoping reviews was determined to be the most appropriate approach to collate a wide range of evidence and identify research gaps in the literature. A detailed search strategy for both peer-reviewed and grey literature was developed prior to conducting any searches. The review protocol was designed and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelinesFootnote 18 and was pre-registered with Open Science Framework (registration https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EG2CP) to increase research transparency and prevent any duplication efforts.

Eligibility criteria

All peer-reviewed journal articles and grey literature related to food marketing to children aged 0 to 17 years and published in either English or French were included. This age group was selected as the development of food marketing restrictions aimed at protecting children originally applied to those under 18 years old in Canada and current Health Canada food marketing monitoring efforts focus on this age group.Footnote 12Footnote 19

We considered only grey literature reports that included primary research; compliance reports were excluded. A complete list of the eligibility criteria is shown in Table 1.

| Eligibility criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Published between October 2016 and November 2021 | Newspaper articles, working papers, conference papers or book chapters |

| Canadian data | Published outside of Canada |

| Original research | Did not describe original research |

| Evidence on the frequency (potential exposure) of food marketing or child/adolescent exposure to and power of food marketing to children (aged 0–17 years) | Compliance reports (e.g. Ad Standards’ report evaluating the enforcement of the CAI among participating companies) |

| Available in English or French | In languages other than French or English |

Abbreviation: CAI, Canadian Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative. |

|

Information sources and search strategy

A systematic search of the following eight academic databases was conducted to identify relevant peer-reviewed results: Ovid MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest ABI/INFORM, ProQuest Canadian Business & Current Affairs (CBCA), Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycINFO and EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search strings used for the academic databases (available on request from the authors) were developed with guidance from a university librarian with expertise in the health sciences. This search of electronic databases was conducted using only English search terms. All results retrieved by the search were imported into COVIDence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, AU),Footnote 20 a web-based software for systematic reviews, and duplicates were automatically removed.

To identify relevant grey literature, a plan consisting of four different search strategies was developed: (1) grey literature databases; (2) Google searches; (3) targeted websites; and (4) consultation with experts. Grey literature strategies were adapted from those used by Godin et al.Footnote 21 The first strategy encompassed a search of English and French grey literature databases (names of databases available on request from the authors). Neither English nor French language searches yielded any results that met the eligibility criteria.

The second search strategy for grey literature consisted of two advanced Google searches (“pdf only” and “any file format” filters). The specific English and French search terms used are outlined in Table 2. Only the first 10 pages of results were pre-screened for relevancy. We used the app Bookmark Manager to document any potentially relevant documents. The same process was repeated for the second Google search, this time using the “any file format” filter. The third grey literature search strategy involved searching the targeted websites that had been identified in the previous Google searches.

Next, we contacted experts in the topic area to identify any relevant documents that were missing and to confirm the comprehensiveness of our grey literature search results; this did not yield any other results.

| Topic | English search terms | French search terms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Food and beverages | “food,” “nutrition,” “beverage,” “drink” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OR’ | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘AND’ | “alimentaire,” “nutrition,” “boisson” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OU’ | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘ET’ |

| 2: Marketing | “marketing,” “advertisement,” “advertising” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OR’ | “marketing,” “publicité” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OU’ | ||

| 3: Children | “child,” “children,” “adolescent,” “teen,” “youth” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OR’ | “enfant” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OU’ | ||

| 4: Canada | “Canada” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OR’ | “Canada” | Search terms combined with the operator: ‘OU’ | ||

Study selection

Two reviewers (FH and DW) screened all peer-reviewed results using COVIDence. The screening of search results from the electronic academic databases occurred in two phases. First, the title and abstract of each article was screened independently by the two reviewers (FH and DW) using the predefined eligibility criteria; any disagreements were resolved via consensus. Next, the full texts of potential articles were screened for eligibility by both reviewers. Disagreements were also resolved by discussion and/or consultation with a third reviewer (LR) when necessary. All articles that remained after full text screening were included in the study.

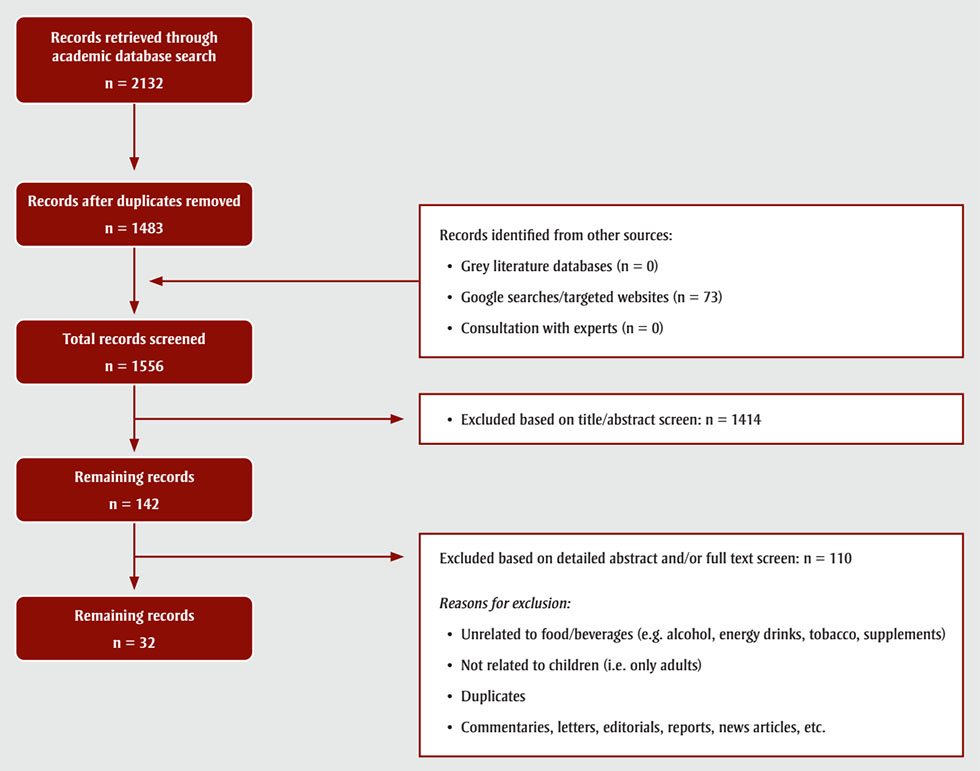

All English and French grey literature search results were screened by two independent reviewers (LR and MB) and any duplicates were removed. Figure 1 summarizes the study selection process for peer-reviewed and grey literature, based on the PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines.Footnote 18

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure presents the PRISMA flow diagram of systematic search of peer-reviewed and grey literature.

2132 records were retrieved through the academic database search. Of those, 1483 records remained after removal of duplicates. Other sources were searched to identify records: grey literature databases (n = 0), Google search/targeted websites (n = 73) and consultation with experts (n = 0). This brought the total of records to be screened to n = 1556. 1414 records were excluded based on title/abstract screen, resulting in n = 142 remaining records. These records were examined, and n = 110 were excluded based on detailed abstract and/or full text screen, for the following reasons:

- Unrelated to food/beverages (e.g. alcohol, energy drinks, tobacco, supplements)

- Not related to children (i.e. only adults)

- Duplicates

- Commentaries, letters, editorials, reports, news articles, etc.

This resulted in n = 32 remaining records.

Data extraction and synthesis of results

Following the screening of results, data were extracted from each article by one reviewer (FH). The extracted data included author and publication year, publication type, location, data collection period, population (preschoolers [0–5 years], children [6–12 years] and adolescents [13–17 years]) and key results related to the frequency of children and youth’s exposure to food marketing. Validation of the extracted data was completed by a second reviewer (DW). The results were subsequently grouped by outcome measure, either the frequency of advertising or actual advertising exposure.

Results

A total of 32 relevant and unique articles were identified. Table 3 summarizes 35 studies extracted from the 32 unique publications by outcome measure (frequency or exposure to food marketing) and categorizes the studies by media and setting. Over half of the unique articles (n = 28) were peer reviewed and 4 were from the grey literature. Almost all articles described (n = 30) were cross-sectional studies, including one repeat cross-sectional study. A total of 27 studies examined the frequency of food marketing, while 8 examined actual exposure to food marketing in Canada.

| Media and settings | Frequency (potential exposure) | Exposure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Location | Population | Data collection period | No. of studies | Location | Population | Data collection period | |

| Television | 3 | CanadaFootnote 22 | Preschoolers, children, adolescents | 12 months (2018) | 4 | Montréal, QCFootnote 25 | Preschoolers and children | 1 month in 2011, 1 month in 2016 and 1 month in 2019 |

| CanadaFootnote 23 | Preschoolers, children, adolescents | 12 months (2018) | Toronto, ONFootnote 24 | Preschoolers and children | 1 month in 2011, 1 month in 2013, 1 month in 2016 and 1 month in 2019 |

|||

| CanadaFootnote 10 | Children | 12 days (2017) | Toronto, ONFootnote 26 | Adolescents | 1 month in 2011, 1 month in 2013 and 1 month in 2016 |

|||

| CanadaFootnote 27 | Adolescents | 12 months (2014) | ||||||

| Digital | 4 | Canadian websitesFootnote 30 | Children | 12 months (2015) | 3 | Ottawa, ONFootnote 32 | Children and adolescents | 2017 |

| Canadian websitesFootnote 28 | Preschoolers and children | 12 months (2015–2016) | Ottawa, ONFootnote 33 | Children and adolescents | 2017 | |||

| Canadian websitesFootnote 31 | Children | 6 months (2017) | CanadaFootnote 27 | Adolescents | 12 months (2014) | |||

| Canadian websitesFootnote 29 | Children | 12 months (2015–2016) | ||||||

| Packaging | 8 | Québec City and Montréal, QCFootnote 34 | Children | 2016, 2018, 2019 | 0 | – | – | – |

| CanadaFootnote 35 | Children | 2013 | ||||||

| Canadian websitesFootnote 36 | Children | 2 months (2018) | ||||||

| Nova ScotiaFootnote 37 | Children | 2 months (2015–2016) | ||||||

| Toronto, ONFootnote 38 | Children | 2013 | ||||||

| Calgary, ABFootnote 39 | Children | 2009 and 2017 | ||||||

| Ottawa, ON and Gatineau, QCFootnote 40 | Children | 2015 | ||||||

| QuebecFootnote 41 | Children | 6 months (2018–2019) | ||||||

| Schools and school settings | 2 | British Colombia, Ontario and Nova ScotiaFootnote 42 | Primary and secondary school-aged | 3 months (2016) | 0 | – | – | – |

| Vancouver, BCFootnote 43 | Elementary and secondary school-aged children | 1 day in June (2015) | ||||||

| 1 day in Sept. (2015) | ||||||||

| Movie theatres | 2 | Ottawa, ONFootnote 44 | Preschoolers, children and adolescents | 4 months (2019) | 0 | – | – | – |

| QuebecFootnote 45 | Children | 9 months (2018–2019) | ||||||

| Sports clubs and recreational sports settings | 3 | Ottawa, ONFootnote 48 | Preschoolers, children and adolescents | 4 months (2018) | 0 | – | – | – |

| British Colombia, Alberta, Ontario and Nova ScotiaFootnote 47 | Children | 6 months (2015–2016), 4 months (2017) |

||||||

| British Colombia, Alberta, Ontario and Nova ScotiaFootnote 46 | Children | 6 months (2015–2016) | ||||||

| Restaurants | 2 | QuebecFootnote 50 | Children | 2 months (2019) | 0 | – | – | – |

| Southwestern OntarioFootnote 49 | Children | 3 months | ||||||

| Festivals/events | 2 | QuebecFootnote 45 | Children | 6 months (2018–2019) | 0 | – | – | – |

| Ottawa, ONFootnote 51 | Children and adolescents | 1 month (2019) | 0 | – | – | – | ||

| Outdoor | 1 | London, ONFootnote 52 | Adolescents | 3 months (2020) | 0 | – | – | – |

| 0 | – | – | – | 1 | CanadaFootnote 27 | Adolescents | 12 months (2014) | |

| Total number of studies | 27 | – | – | – | 8 | – | – | – |

Notes: The total number of studies is greater than 32 as some publications included multiple studies in the same publication. “–“ indicates that the data are not available or do not apply. |

||||||||

The included literature examined the frequency or exposure to food marketing on television,Footnote 10Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27 in digital mediaFootnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33 and on packaging;Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41 in schools,Footnote 42Footnote 43 movie theatres,Footnote 44Footnote 45 sports settings,Footnote 46Footnote 47Footnote 48 restaurantsFootnote 49Footnote 50 and family-related festivals/events;Footnote 45Footnote 51 outdoors (e.g. billboards, bus shelters, etc.)Footnote 52 and in print.Footnote 27 Of all included studies, only 5 were conducted outside of Ontario or Quebec.

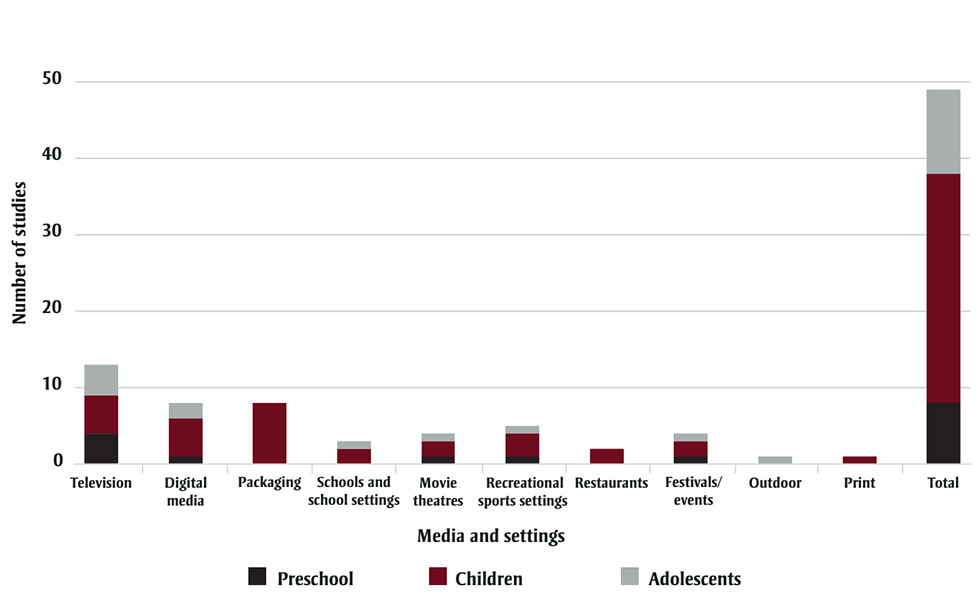

Figure 2 displays the number of included studies by target population and media/setting.

Figure 2 - Text description

| Group | Number of studies | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Television | Digital media | Packaging | Schools and school settings | Movie theatres | Recreational sports settings | Restaurants | Festivals/ events |

Outhoor | Total | ||

| Preschool | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Children | 5 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 30 |

| Adolescents | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

Frequency and exposure to food and beverage marketing in various media

Television

Three studies examined the frequency of television food marketing directed at youth, but differences in the methodology and data collection periods make it challenging to compare the rates of advertising across these studies. Annual data drawn from television stations in 2018 revealed that the rate of food advertisements differed significantly between preschooler (0–5 years), child (6–12 years) and youth (13–17 years) age groups, from 0.6 to 3.3 advertisements/hour.Footnote 23 The same research team determined that more than half of the advertisements during children’s programming was produced by CAI-participating companies.Footnote 22

An international study establishing children’s potential exposure to television food advertising determined that 25% of advertisements sampled over a 12-day period on the top three children’s stations in Canada were for food and beverages, and that the rate of 10.9 food advertisements/hour on child-specific channels were among the highest globally.Footnote 10

Child and adolescent actual exposure to television food marketing in Canada has been measured both objectively, through television viewership data (n = 3), and through self-report (n = 1). In Toronto (Ontario), children (2–11 years) and adolescents’ (13–17 years) exposure decreased over time despite increases in the frequency of food marketing on television.Footnote 24Footnote 26 Similar exposure trends were also observed among children (2–11 years) in Montréal (Quebec).Footnote 25 Children and adolescents in Toronto and children in Montréal appear to be exposed to similar, unhealthy food categories such as fast food and sugary drinks and snacks.Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26

Hammond and ReidFootnote 27 conducted an online survey to assess self-reported exposure to energy drink advertisements on television. Of youth aged 12 to 14 years and 15 to 17 years, 59% (233/393) and 56.2% (348/620), respectively, reported ever having seen an energy drink advertisement on television.

Digital media

The frequency of food marketing on digital media has only been documented on websites. Two studies compared the presence of child-directed online content in companies participating in the CAI with companies that did not.Footnote 30Footnote 31 Both studies found that participation in the CAI did not deter the companies from marketing child-directed products (as defined by the presence of child-oriented features) nor the inclusion and promotion of corporate social responsibility initiatives designed to target children through support of school food programs or children’s sports programs on company sites.Footnote 30Footnote 31

Other studies have documented varying levels of frequency of online food marketing. Two studies found that food marketing frequently appears on children’s (2–11 years) and adolescents’ (12–17 years) top 10 preferred websites, with an estimated 54 million and 14.4 million food and beverage advertisements reported on children’s preferred and adolescent’s preferred websites respectively, from June 2015 to May 2016 alone.Footnote 28Footnote 29 Most advertisements on both types of websites were for foods and beverages classified as excessive in fat, sodium or free sugars.Footnote 28Footnote 29

Three studies captured actual exposure to digital food marketing by youth.Footnote 27Footnote 32Footnote 33 Two studies by Potvin Kent et al.Footnote 32Footnote 33 measured child and adolescent exposure to food marketing over 10-minute periods on gaming applications (93 participants; aged 6–16 years) and on social media (101 participants; aged 7–16 years). Children and adolescents who used social media were exposed to food advertisements more frequently than those who used gaming apps (on average, 111 times/week versus 2.8 times/week, respectively).Footnote 32Footnote 33 In both types of applications, children and adolescents were most exposed to marketing of fast food, sugary drinks and candy/chocolate.Footnote 32Footnote 33

Hammond and ReidFootnote 27 measured adolescent’s self-reported exposure to energy drink advertisements and found that more than one-third of youth aged 12 to 17 years viewed energy drink advertisements on social media. Between 35.6% (140/393) of youth aged 12 to 14 years and 39.3% (244/620) of youth aged 15 to 17 years reported seeing energy drink advertisements online.Footnote 27

Packaging

Eight studies assessed the proportion and types of food and beverage products commonly promoted in retail environments. Across most studies, the marketing of child-targeted products was apparent.Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41 For instance, in the University of Toronto’s Food Label Information Program 2013 (FLIP 2013) database, almost 5% of the 15 200 packaged supermarket products captured displayed at least one marketing technique considered to be directed to children.Footnote 35

Three studies identified breakfast cereals as a product that is frequently advertised to children.Footnote 34Footnote 39Footnote 41 ElliottFootnote 39 noted an increase in volume of child-targeted cereal products in two supermarkets over an 8-year span (31/354 to 59/374). The prominence of marketing breakfast cereal over other food categories is supported by research specifically characterizing child-directed marketing of breakfast cereals. Findings from one study revealed that almost one-fifth of 262 breakfast cereals sold in Ottawa (Ontario) and Gatineau (Quebec) supermarkets were considered child targeted.Footnote 40 These cereals were also three times more likely to be classified as “less healthy” than non-child-targeted cereals and were considerably higher in sodium and free sugar.Footnote 40

Similar findings on the healthfulness of frequently advertised child-targeted food and beverages are echoed elsewhere in Canada,Footnote 36Footnote 38 including in Montréal and Québec City (Quebec).Footnote 34 Of the products featuring child-directed marketing techniques in FLIP 2013, Mulligan et al.Footnote 35 determined that the majority (727/747) were classified as restricted from marketing to children based on Health Canada’s nutrient criteria. In contrast, Kholina et al.Footnote 37 found that “less healthy” products, including snack foods and sugary drinks, but not breakfast cereals, were heavily promoted to children and more prominently displayed in 47 grocery stores and 59 convenience stores in Nova Scotia.

Frequency and exposure to food and beverage marketing in various settings

Schools

Evidence on food marketing both within and around schools in Canada is lacking. Only one recent study assessed the frequency of food marketing in schools, documenting that at least one type of food marketing was reported in 83.7% (129/154) of primary and secondary schools (n = 154) across British Colombia, Ontario and Nova Scotia.Footnote 42 Primary schools were more likely to report selling branded food items such as pizza, chocolate and fast food compared to secondary schools. However, secondary schools were more likely to report food marketing on school property, food product displays and exclusive marketing agreements with food companies.

One study examined the food marketing environment in schools. Findings from the Velazquez et al.Footnote 43 study support the prevalence of food marketing for minimally nutritious foods around schools in Vancouver (British Colombia). Almost all (22/26) of the schools participating in the study had at least one food and/or beverage advertisement within 400 metres, and 5 of the 26 schools had 50 or more advertisements in their immediate vicinity.Footnote 43 The majority of the food marketing promoted products that failed to fall within provincial school food guidelines.Footnote 43

Movie theatres

Two studies reported food marketing from multiple sources within movie theatres, including advertisements in the movie theatre environment and those screened prior to children’s movies.Footnote 44Footnote 45 The results of these two studies indicate that a large volume of food advertisements, particularly for traditionally unhealthy movie theatre foods such as popcorn, soft drinks and candy/chocolate, are promoted both in the common spaces of movie theatres and before the start of children’s movies.Footnote 44Footnote 45 For example, a total of 1999 food advertisements were identified in movie theatre environments across seven movie theatres in Ottawa (Ontario) and 241 advertisements were observed prior to the screening of 28 children’s movies over a 4-month period.Footnote 44 All of these advertisements were considered to be restricted from marketing to children based on the World Health Organization’s Nutrient Profile Model.Footnote 44 Product placements in movies may also account for a small share of children’s potential exposure to food advertising.Footnote 45

Sports clubs

This review identified three studies that focussed on food marketing in sports clubs and recreational sports settings. Two studies confirmed that food and beverage marketing is frequent in sports and recreational facilities, most commonly occurring in sites with food concessions, sports areas and other areas.Footnote 46Footnote 47 The median number of food advertisements across 16 recreational facilities in Ontario over 6 months was about 29.Footnote 47 In such settings, food marketing takes many forms including posters, signs and product placement.Footnote 46 Out of 51 recreational sports settings in Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia, food marketing was present in 98% (49/50) of all sites and over half of all food marketing instances were considered “least healthy.”Footnote 46

Children’s sports clubs also present opportunity for food marketing to children. One study found that 40% (27/67) of 67 children’s sports clubs in Ottawa (Ontario) obtained some form of food company sponsorship, with fast food restaurants accounting for 41% of these sponsorships.Footnote 48

Restaurants

Two articles reviewed food marketing in restaurants. Findings from these studies indicate a mix of strategies used to market to children in restaurants; one study of 20 restaurants in Quebec noted the frequent use of meal and food packaging as well as in-restaurant promotions (e.g. posters, toy displays, etc.) as a marketing tool among fast food restaurants.Footnote 50 Food marketing in family restaurants was predominantly present on children’s menus and included the use of branded marketing.Footnote 49Footnote 50 Neither study was designed to measure children’s actual exposure to these types of food marketing.

Festivals/Events

Of all the studies included in this review, only two described food marketing at family events. The Quebec Coalition on Weight-Related Problems examined marketing across 18 family festivals, amusement parks and ski facilities over 6 months; while findings suggested an overall improvement in the frequency of food advertising at family festivals, unhealthy foods were heavily promoted at amusement parks and child-directed advertising remained apparent at all three types of family venues.Footnote 45 One study examined the extent of food marketing-related content associated with social media; individual users were responsible for most marketing-related instances associated with a family-event compared to corporate or other post sources, and children were frequently featured in these types of social media posts.Footnote 51

Outdoor

One study used Global Positioning System (GPS) points collected from a mobile application to monitor 154 adolescents’ (13–18 years old) proximity to outdoor advertising, such as in bus shelters, street-level posters and billboards (n = 97) over 3 months. The data collected revealed that most adolescents were exposed to at least one advertisement during this period.Footnote 52

There is a paucity of literature investigating print media food marketing. Hammond and Reid’sFootnote 27 online survey revealed that 22.4% (88/393) and 28.6% (177/620) of adolescents aged 12 to 14 years and 15 to 17 years, respectively, reported having ever seen a food or beverage advertisement in magazines or newspapers.

Discussion

This scoping review reveals that food marketing to children and adolescents is prevalent in Canada across a wide variety of media and settings. While the studies included in this review suggest digital media and television to be important sources of children’s actual exposure to unhealthy advertisements, the evidence base is limited. The results of this review also highlight that less healthy food products, such as snack foods, sugary drinks and fast food, are commonly promoted in the array of settings and media, consistent with previous Canadian research.Footnote 7 Despite these findings, this review emphasizes the dearth of research exploring food marketing to children by age, geographical location, sex/gender, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Media examined

Television, digital media and packaging collectively dominated the food marketing research focus, with over half of the identified studies focussing exclusively on these types of media. The levels of food marketing observed on television and in digital media are of particular concern given the high levels of screen time youth in Canada report, with 47% of youth aged 5 to 17 years spend over 2 hours per day on screens.Footnote 53 This is compounded by an exponential increase in social media and Internet usage among youth, providing even greater opportunity for the food industry to target children and adolescents.Footnote 15 Research also suggests that social media influencers are an increasingly popular promotional source for food products targeting youth.Footnote 15Footnote 53 Despite these findings, no research has examined children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing through digital media influencers.

This review also highlights a lack of exploration beyond traditional and digital media. This is consistent with the previous scoping review conducted by ProwseFootnote 7; this review also cited a need for evidence of food marketing in other media frequently used by children to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of sources of youth exposure to food and beverage marketing. Though one study in this review documented exposure to food marketing in gaming apps, exposure on other child and adolescent gaming platforms, such as computer games or arcade games, is less understood. This is an important area given that Canadian youth, on average, spend 0.75 hours per day playing video games.Footnote 15

This review found some evidence on print and outdoor food marketing. While the inclusion of such media in the recent literature differs to that prior to 2016,Footnote 7 the limited evidence base precludes interpretations on the extent of food marketing in these categories. Research from New Zealand also identified public spaces, including street signs and shop fronts, as a substantial source of children’s exposure to unhealthy food advertising.Footnote 54Footnote 55 Future research should also address print, out-of-home (e.g. billboards, street furniture ads, bus “wraps”) and radio marketing—platforms that may promote child-targeted products.

Settings examined

The settings-based evidence presented in this review demonstrate that unhealthy foods and beverages are often promoted in settings frequented by children, such as schools and movie theatres. The emphasis on these settings is valuable and warrants further research to document children’s actual exposure to food marketing in these environments. The paucity of literature on food marketing in other settings that impact children, including recreational centres, sports clubs or convenience stores, highlights a considerable knowledge gap that needs to be filled to inform policy design in this area.

Target population examined

Children were assessed in all of the settings as part of this review (television, digital media, packaging, schools, movie theatres, sports clubs, restaurants and festivals/events). However, settings-based evidence is lacking for preschoolers and adolescents in schools, restaurants and festivals/events.

The research presented in this review focussed on children, with adolescents included in only 25% (9/32) of all publications. Preschoolers were rarely included (<15% of all studies), and almost no studies examined food marketing to either of these age groups. The majority of recent television studies examined adolescents while most digital marketing and food packaging research centred around children. The lack of emphasis on child populations outside the 6- to 12-year age range has been noted in the Canadian food marketing literature; ProwseFootnote 7 found a notable absence of preschooler- and adolescent-specific research prior to 2016. Younger children and adolescents represent critical stages in the development of dietary habits.Footnote 5 Adolescents are frequently excluded from regulatory action against food marketing to children. A recent scoping review specifically on food marketing to adolescents also emphasized the dearth of studies focussing exclusively on adolescent populations and an existing focus on television advertising to youth.Footnote 56 Research benchmarking adolescent exposure to food marketing in a variety of media and settings will help justify their protection and inclusion in future marketing restrictions.

Geographical distribution examined

Research on food marketing to children in Canada has primarily been conducted in Ontario and Quebec. Of the studies included, only four focussed on the province of Quebec. More research estimating the frequency and actual exposure to this marketing is needed in Quebec, particularly in digital media, in out-of-home marketing and in settings such as schools. Such research is especially important as the Consumer Protection Act (CPA) is being considered as a regulatory model for unhealthy food marketing restrictions nationally and internationally.

It is essential to benchmark food marketing to children and adolescents across many different provinces, given Canada’s unique regulatory landscape. Previous evidence indicates that food marketing varies across regions in Canada, particularly television marketing.Footnote 7 To date, no studies have assessed food marketing to children in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island or Newfoundland and Labrador or in any of the three Canadian territories.

Diversity in food marketing research

Despite a growing evidence base of food marketing to children in Canada, there is a strong need to produce more nuanced research that considers exposure by language, sex/gender, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status to enable the development of policies to protect these groups. Similarly, food marketing to Indigenous children in Canada remains an area severely underrepresented in the literature. While no studies in this review focussed on diversity in any of these aforementioned capacities, international research suggests that boys, as well as Black and Hispanic youth, may be disproportionately exposed to food marketing.Footnote 57Footnote 58

Research directions and policy implications

The evidence synthesized in this review elucidates several critical gaps in the food marketing literature in Canada. Food marketing to children is a complex issue, shaped by a myriad of sociological and physical factors. However, other than media and settings, the current literature lacks recognition and exploration of underlying sociodemographic factors, such as age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographical location and language spoken in the home, which may contribute to differences in the type and frequency of food advertisements viewed by Canadian children. The results of several studies across multiple media platforms and settings between 2016 to 2021 illustrate the extensive state of food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada. The advent of new media, such as television streaming or online gaming platforms, as well as the impact of COVID-19 on the frequency and children’s exposure to food marketing also necessitates further inquiry. Other settings contributing to unhealthy food marketing in children’s daily lives, including recreational centres and convenience stores, should also be explored. Further research is needed to fully quantify children and adolescent’s actual exposure across all research gaps identified in this review. With regard to policy, funding to support continued monitoring of food marketing to children and adolescents across a variety of media and settings needs to be provided by government. Such monitoring will inform future policy action that would aim to protect all youth in Canada from the harms of unhealthy food and beverage marketing.

Strengths and limitations

This review captures the breadth of English and French peer-reviewed and grey literature examining the frequency of and children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing in Canada. This range highlights multiple potential research avenues for future research. However, this study did not evaluate the risk of bias or methodological quality of the research included. Furthermore, although data collection periods used to determine the frequency of food marketing or exposure to food marketing ranged from 1 day to 12 months, few studies examined marketing to children over a full yearFootnote 23 and only four studies compared data over multiple different years.Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 39 Marketing is a field that is constantly changing and evolving; the current research studies in Canada may not capture these changes.Footnote 23

Conclusion

This scoping review benchmarks current levels of food marketing to youth in Canada by media, target population and geographical location. The findings of this review demonstrate that unhealthy food marketing is prevalent in an increasing range of media platforms and settings frequented by children and adolescents. Although more nuanced research is needed to address food marketing in specific youth demographic segments, our evidence synthesis suggests that food and beverage marketing persists despite current self-regulatory and statutory policies within Canada. Further monitoring guided by the research gaps identified in this review may help inform future food marketing policies to protect children in Canada.

Acknowledgements

Ottawa Public Health funded this research. We would also like to acknowledge Marie-Cécile Domecq’s help in developing our search strategy.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

MPK conceived this study, developed the methodology, interpreted the results and revised the final manuscript.

FH collected data and wrote the draft manuscript.

DW collected the data and helped write the draft manuscript.

LR collected the data and revised the manuscript.

MB collected the data and helped interpret the results.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.