Original qualitative research – Exploring the contextual risk factors and characteristics of individuals who died from the acute toxic effects of opioids and other illegal substances: listening to the coroner and medical examiner voice

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: February 2023

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Tamara Thompson,Footnote * PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Jenny Rotondo,Footnote * MHScAuthor reference footnote 2; Aganeta Enns, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2; Jennifer Leason, PhDAuthor reference footnote 3; Jessica Halverson, MPH, MSWAuthor reference footnote 2; Dirk Huyer, MDAuthor reference footnote 4; Margot Kuo, MPHAuthor reference footnote 2; Lisa Lapointe, BA, LLBAuthor reference footnote 5; Jennifer May-Hadford, MPHAuthor reference footnote 2; Heather Orpana, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2Author reference footnote 6

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.2.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Aganeta Enns, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Ave., Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 343-551-4367; Email: aganeta.enns@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Suggested citation

Thompson T, Rotondo J, Enns A, Leason J, Halverson J, Huyer D, Kuo M, Lapointe L, May-Hadford J, Orpana H. Exploring the contextual risk factors and characteristics of individuals who died from the acute toxic effects of opioids and other illegal substances: listening to the coroner and medical examiner voice. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(2):51-61. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.2.01

Abstract

Introduction: Substance-related acute toxicity deaths continue to be a serious public health concern in Canada. This study explored coroner and medical examiner (C/ME) perspectives of contextual risk factors and characteristics associated with deaths from acute toxic effects of opioids and other illegal substances in Canada.

Methods: In-depth interviews were conducted with 36 C/MEs in eight provinces and territories between December 2017 and February 2018. Interview audio recordings were transcribed and coded for key themes using thematic analysis.

Results: Four themes described the perspectives of C/MEs: (1) Who is experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?; (2) Who is present at the time of death?; (3) Why are people experiencing an acute toxicity death?; (4) What are the social contextual factors contributing to deaths? Deaths crossed demographic and socioeconomic groups and included people who used substances on occasion, chronically, or for the first time. Using alone presents risk, while using in the presence of others can also contribute to risk if others are unable or unprepared to respond. People who died from a substance-related acute toxicity often had one or more contextual risk factors: contaminated substances, history of substance use, history of chronic pain and decreased tolerance. Social contextual factors contributing to deaths included diagnosed or undiagnosed mental illness, stigma, lack of support and lack of follow-up from health care.

Conclusion: Findings revealed contextual factors and characteristics associated with substance-related acute toxicity deaths that contribute to a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding these deaths across Canada and that can inform targeted prevention and intervention efforts.

Keywords: opioids, illegal drugs, substance-related harms, drug overdose, death, coroners and medical examiners, qualitative research

Highlights

- People dying from substance-related acute toxicity came from all demographic and socioeconomic groups and had different histories of substance use, including first-time and occasional use, long-term use and management of chronic pain.

- Using substances alone and using in the presence of somebody who does not recognize the signs of an acute toxicity event or is unable to respond were identified as risks for substance-related acute toxicity death.

- People who died from a substance-related acute toxicity often had one or more of these contextual risk factors or characteristics: they consumed substances of unexpected potency or composition (e.g. contaminated substances); they had diagnosed or undiagnosed mental illness, history of trauma, history of substance use, history of chronic pain, decreased substance tolerance or experiences of stigma; and there was a lack of support or health care follow-up.

- Coroners and medical examiners are an underutilized source of expert information and can contribute to our understanding of opioid and other substance-related acute toxicity deaths.

Introduction

Deaths from the acute toxic effects of opioids and other substances continue to be a significant public health concern in Canada and have largely been driven by “an interaction between prescribed, diverted and illegal opioids (such as fentanyl) and the recent entry into the illegal drug market of newer, more powerful synthetic opioids.”Footnote 1,p.3 In April of 2016, British Columbia declared a public health emergency due to increasing rates of substance-related acute toxicity deaths. This increase had mainly been driven by illegal opioids, namely fentanyl and its analogues.Footnote 1

Since April of 2016, the emergency has worsened and other Canadian provinces and territories have also reported an increase in deaths resulting from opioids and illegal substances.Footnote 2Footnote 3 Between January 2016 and March 2022, there were over 30 000 apparent opioid-related deaths (AORD) in Canada.Footnote 4 Since national surveillance began in 2016, the highest rate of AORDs was observed in 2021. The areas most impacted by AORDs continue to be Western Canada and Ontario, but other provinces have shown an increase.Footnote 4 There is also concern for the number of deaths that involve other substances; for example, stimulants were detected in approximately 60% of accidental opioid-related deaths in 2021.Footnote 5

A number of studies have used coroner and medical examiner (C/ME) data or reports to shed light on acute toxicity deaths related to opioid and other substances. Contextual risk factors for substance-related acute toxicity death commonly identified in these studies included history of mental illness,Footnote 6Footnote 7 previous suicide attempts,Footnote 7 discharge from a treatment centre or health care facility,Footnote 8 recent nonfatal overdose,Footnote 9 recent release from jail,Footnote 10 use of multiple substances,Footnote 11 history of chronic painFootnote 6 and a history of substance use.Footnote 6 However, these studies often focussed on a single province or territory, included only limited circumstances surrounding substance-related acute toxicity death and relied on the information recorded by the C/MEs in charts and reports.

Researchers have previously sought to understand the perspectives of people who experienced nonfatal overdose eventsFootnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16 and friends and family of people who have died from overdose.Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19 However, the perspectives of the C/MEs have not, to our knowledge, been published, with the exception of a preliminary, unreviewed report that was published onlineFootnote 20 based on data that were collected for the present study.

The high number of substance-related acute toxicity deaths in Canada represents a complex and multifaceted public health crisis, and national evidence on the contexts surrounding the deaths is needed to elucidate contributing factors and inform targeted responses. Investigating the perspectives of C/MEs on the contextual factors surrounding substance-related acute toxicity deaths may contribute novel evidence to enhance understanding of the circumstances and characteristics common across Canada, due to the C/MEs’ experience with cases over time and the breadth and complexity of the information that they obtain from multiple sources during death investigations.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to obtain the perspectives of C/MEs on the deaths they investigated from the acute toxic effects of opioids and illegal substances, and to obtain in-depth evidence on common characteristics and contextual factors across Canada.

Methods

Ethical considerations and quality assurance

The Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada Research Ethics Board approved this study (certificate #REB 2017-0016). To ensure the trustworthiness of this study, its methodology contained steps to establish its credibility, confirmability and transferability.Footnote 21 Credibility was established by sharing the findings with all participants for review and feedback, which was then incorporated into the findings. The qualitative researchers (QRs) exchanged a selection of coded transcripts with the co-investigators to confirm the assigned coding and thematic analysis to corroborate findings and establish confirmability. To increase transferability, we have provided thick descriptions, wherever possible, of the participants’ context and of the data collection procedure to facilitate evaluations of how the findings may transfer to other settings.

Study design

This qualitative study was conducted with C/MEs in eight provinces and territories across Canada. Through semistructured interviews, C/MEs were asked to reflect on the interplay of the common characteristics, contextual risk factors and opportunities for interventions in the investigations in which they had been involved.

This methodology values the experiences and perceptions of C/MEs, beyond what is documented in individual case files, and enables C/MEs to aggregate details across cases to provide insight into common characteristics and contextual factors. Practically, this methodology allows for the aggregation of national knowledge into a contextual, meaningful summary.

Recruitment

C/MEs were selected because of the breadth and complexity of information they obtain from numerous sources during their death investigations, and their mandated role in understanding deaths.

Provincial and territorial chief C/MEs were contacted to participate and assess interest in engaging in this study. Interested chief C/MEs prepared a letter of support and provided a list of potential regional and local C/MEs with consideration to achieving a broad geographic representation. Participant sampling was stratified by province or territory. Participating provinces and territories were allocated interviews based on their proportion of the Canadian population and their proportion of apparent opioid-related deaths at the national level.

Potential participants nominated by their chief C/ME received an email from Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) study coordinators inviting them to participate in the study. The email included a description of the study, a support letter from their chief C/ME, a short questionnaire and a consent form. The questionnaire contained questions about demographic information, the location where the majority of their cases occur (e.g. urban, rural, remote) and years of experience investigating deaths. Chief C/MEs were not informed which of their nominated staff participated in the study.

Interviews

A semistructured interview format was used to allow participants to share their own perspectives, while ensuring that answers informed the study purpose and enabled comparisons across respondents. The interview guide was pilot-tested with two C/MEs, and revisions were made to the interview questions as required.

Participants were anonymous to the interviewer with the exception of their province/territory. Interviews followed the semistructured interview guide (Table 1) and were conducted by telephone in the participant’s preferred language (English or French). The interviews were audio recorded on a secure PHAC telephone line. Interviews ranged from 40 minutes to two hours. Each participant engaged in a single interview with one interviewer.Footnote † Only the participant and the researcher were present for the telephone interviews. There were no withdrawals from the study once participants were recruited. Participants were asked to reflect on the deaths from the effects of opioids and other illegal substances that they had investigated in the past two years. C/MEs were asked to describe characteristics and trends, rather than information on specific cases. The two QRs took field notes after each of the interviews was completed.

| Main interview questions | Probes/follow-up questions |

|---|---|

| What position do you currently hold with the coroner’s/medical examiner’s office and what experiences and education led you to this position? | What degrees or training do you have for your position? Can you describe your experience investigating deaths in vulnerable populations? |

| Can you give a short overview of the processes your office uses to investigate acute toxicity deaths? | Have there been any changes in the investigation, testing or reporting process that your office uses that may be influencing the rates or details of deaths reported from your jurisdiction? Are there any steps or tests that are missed or excluded that may influence your determination of the circumstances of death? |

| Can you tell me about the acute toxicity deaths that you have investigated over the last two years? | What interplay between social, demographic and economic factors have you observed? Do these differ depending on the substances involved? What are the most problematic substances or combinations of substances among the deaths that you have investigated? Can you describe any patterns of polysubstance use in the days leading up to death or any other problematic combinations that you have seen? Were there any differences in the individuals or circumstances depending on if they were personal pharmaceutical drugs, diverted pharmaceutical drugs, or illegal substances? |

| Based on your investigations, what do you feel are the key risk factors that lead to acute toxicity deaths and who is most impacted by these factors? | Have you noticed that risk factors are changing? Are you able to attribute the risk factors to populations you mentioned previously or do these risk factors cross all populations? |

| Have you noticed any changes in who is dying or the substances involved, particularly over the last two years? | You mentioned that [describe a group or drug that was mentioned in the last question] earlier. Have you noticed a change in the proportion of deaths with this characteristic or using this drug? What changes to the substances involved do you anticipate for the future? |

| In your investigations, have you noted any opportunities to prevent these deaths that may have been missed or underutilized? | Are there any overdose or acute toxicity prevention activities that you believe should be considered or prioritized for your jurisdiction? Now considering individuals that are at high risk of overdose or acute toxicities, are there more upstream interventions that you believe should be prioritized or implemented? |

| I will now ask you to review the provided opioid-related death statistics reported by your province/territory. What context do you feel is helpful to understand this data in order to compare to other jurisdictions? | Are there any differences with illegal vs. non-illegal drugs? |

| Is there anything else that you would like to share when considering how to address this issue? | Are there any other “takeaways” you think are important? |

Data management

Study data were protected in accordance with PHAC’s Directive for the collection, use and dissemination of information relating to public health (2013, unpublished document). The interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. French transcripts were translated to English by a professional translator, and a bilingual research team member (HO) compared the translated versions with the originals to ensure that meaning was not lost in translation.

To ensure confidentiality, all identifying information was removed from the interview transcripts and all interviews were assigned an identification number. The interview data were checked for accuracy, imported and managed with NVivo11.Footnote 22

Data analysis

Braun and Clarke’sFootnote 23 six-phase process for thematic analysis was utilized in this study, with a focus on the coding reliability approach to ensure accurate and reliable data coding and analysis.

Analysis of the data began with the QRs individually reading and re-reading the interview transcripts to become familiar with the depth and breadth of the data and develop a codebook with a list of codes. Codes are concepts that are used to provide a name to describe what the participant is saying. A code can be a word, phrase, sentence or paragraph that describes the phenomenon under study.Footnote 24 Following the initial coding of the interview data, the QRs began a process of iterative consensus building of the identified codes.

The QRs then categorized the codes into basic, organizing and global themes.Footnote 25 A theme is a broader constellation or category used to capture the more general phenomenon to which a code refers.Footnote 25 “Basic themes” are the simplest themes that come from the interview data and contribute to higher order themes.Footnote 25 When taken together, the basic themes constitute “organizing themes,” which are middle-order themes that organize the basic themes into clusters of similar issues. A group of organizing themes, when taken together, then make up a “global theme,” which is the highest order of themes and encapsulates the essential organizational concepts that work to provide a core interpretation or explanation of the text.Footnote 25

Similarities and divergences detected in the coding and thematic process were discussed between the two QRs, and consensus was attained to validate the story of the data. Once the themes were finalized, a thematic map was developed and the story of the data was written by the QRs. A visual representation of global, organizing and basic themes is illustrated as a thematic network map in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure depicts a generic thematic network map. In a web-like fashion, the middle (and largest) bubble contains the “Global theme.” Four slightly smaller bubbles stem from this central bubble, all of which contain an “Organizing theme.” Finally, to each of the “Organizing theme” bubbles are attached a variable number of smaller bubbles containing a “Basic theme.”

Results

Thirty-six participants from eight provinces and territories were interviewed in the study. Table 2 provides the participant characteristics as well as the provinces and territories represented in this study.

| Characteristic | Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Women | 23 (64%) |

| Men | 13 (36%) |

| Age in years [median (range)] | 49 (26–74) |

| Profession | |

| Coroner | 31 (86%) |

| Medical examiner | 2 (6%) |

| Chief coroner, medical examiner, or toxicologist |

3 (8%) |

| Years participating in death investigations [median (range)] | 9 (1–35) |

| Geographic region of deaths investigatedFootnote a | |

| Urban | 32 (89%) |

| Suburban | 25 (69%) |

| Rural | 25 (69%) |

| Remote | 16 (44%) |

| Province or territory | |

| British Columbia | 8 (22%) |

| Saskatchewan | 4 (11%) |

| Ontario | 10 (28%) |

| Quebec | 8 (22%) |

| Nova Scotia | 3 (8%) |

| Other provinces and territories | 3 (8%) |

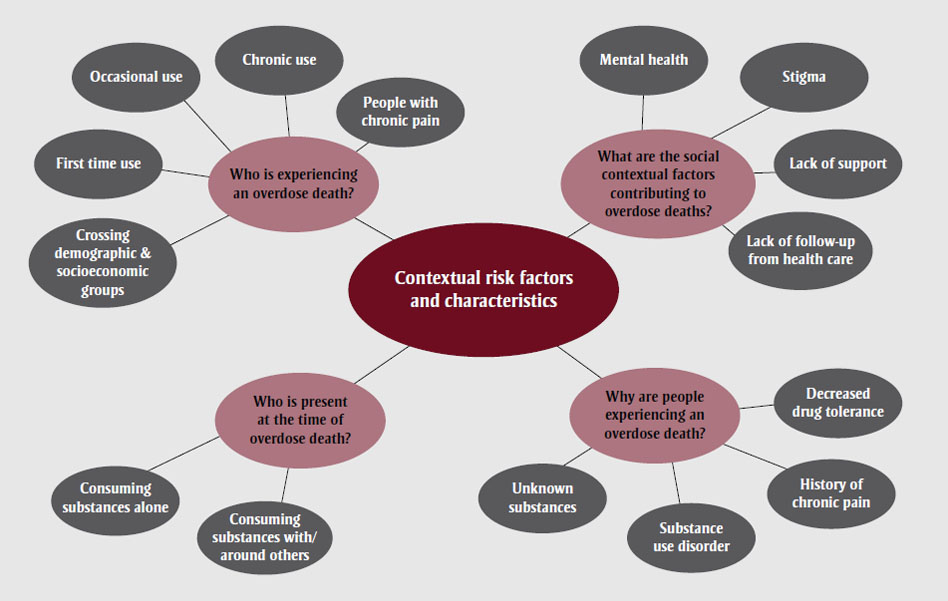

The findings focus on the global theme “contextual risk factors and characteristics of substance-related acute toxicity death”. Four organizing themes were identified from the global theme: (1) Who is experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?; (2) Who is present at the time of death?; (3) Why are people experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?; and (4) What are the social contextual factors contributing to deaths? The global, organizing and basic themes are shown in Figure 2 as a thematic map.

Figure 2 - Text description

This figure depicts the thematic map of the findings.

The largest bubble, presenting the global theme, contains the text “Contextual risk factors and characteristics.”

The four slightly smaller bubbles connected to this large bubble present the organizing themes, each of which has a number of even smaller bubbles presenting the basic themes, in the following fashion:

- Organizing theme: “Who is experiencing an overdose death?”

- Basic theme: “Crossing demographic & socioeconomic groups”

- Basic theme: “First time use”

- Basic theme: “Occasional use”

- Basic theme: “Chronic use”

- Basic theme: “People with chronic pain”

- Organizing theme: “What are the social contextual factors contributing to overdose deaths?”

- Basic theme: “Mental health”

- Basic theme: “Stigma”

- Basic theme: “Lack of support”

- Basic theme: “Lack of follow-up from health care”

- Organizing theme: “Who is present at the time of overdose death?”

- Basic theme: “Consuming substances alone”

- Basic theme: “Consuming substances with/around others”

- Organizing theme: “Why are people experiencing an overdose death?”

- Basic theme: “Unknown substances”

- Basic theme: “Substance use disorder”

- Basic theme: “History of chronic pain”

- Basic theme: “Decreased drug tolerance”

Organizing theme 1: Who is experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?

Five themes for “Who is experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?” were identified: crossing demographic and socioeconomic groups, first time use, occasional use, chronic use and people with chronic pain.

C/MEs highlighted that the deaths they investigated were crossing all demographic and socioeconomic groups. For the most part, substance-related acute toxicity deaths have occurred historically among people with lower socioeconomic status; however, over the last two years of the study period, C/MEs across Canada noticed a change in the profile of acute toxicity deaths. Increasingly, they observed deaths involving individuals from a range of socioeconomic statuses and employment/occupations as well as a wider range of substance use histories, including first time substance use, occasional use and chronic use, as well as individuals who had a history of taking medications to treat chronic pain.

People consuming substances were noted as being at risk for an acute toxicity death if it was their first time use or they engaged in occasional use, potentially because they may have lacked awareness of the substances they were taking, including the source of the substances and the potential for them to be contaminated with undisclosed substances (e.g. fentanyl). First time or occasional use could also elevate risk due to low biological tolerance. Occasional use and first time use are illustrated by C/MEs here:

From the cases that I’ve heard some of my colleagues having, it’s the teenager who it’s the first time s/he is using drugs, it’s the rave, the more common parties that people are using drugs, and I think fentanyl is getting mixed with more and more common drugs that are not felt to be major drugs of [use] and stereotypically the drugs that people who are major [substance consumers] are using. (S019 ON)

I had some cases involving young people who are always in party mode ... they don’t know what they’re buying because they’re getting them on the street. ... They think they know what they’re buying. But they really don’t know. (S062 QC)

C/MEs talked about still seeing people who had a history of chronic use of opioids and illegal substances experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death, as illustrated here:

Not all of the cases that I’ve gone to are [people who had a history of] chronic long-term [substance use] ... I’d say many are but not all of them. There are some where they manage to hold down jobs or they’re kind of, you know, the [people who use occasionally] on the weekends ... but most of them have got a history where—and when I say history it’s not like, you know, they just have started using but it can go—depending on the age of the person, it goes back a few years. (S026 BC)

People with chronic pain as a result of surgery or work-related injuries were also noted as at risk of an acute toxicity death. One participant stated:

Some of them are trades workers, I think there was construction workers ... in some of the cases I’d say some of them were suffering from pain and they transitioned from painkillers possibly to more illegal substances. (S079 ON)

C/MEs noted some of the cases they investigated were among people who began taking medications because of a history of chronic pain but then became addicted and may not have been provided with or had access to alternatives for treatment.

Organizing theme 2: Who is present at the time of death?

The organizing theme “Who is present at the time of death?” consisted of two interrelated themes: consuming substances alone and consuming substances with/around others.

C/MEs talked about people consuming substances alone, including people who lived alone and may have been isolated or marginalized. One participant talked about people consuming substances alone with no one to respond or intervene in an acute toxicity event or death:

Most of the people that I go to have died alone. They die in their bedroom or in their living room or in their bathroom, and the majority of them, there’s no one there to call 9-1-1 and sound the alarm. (S026 BC)

The theme “people consuming substances with/around others” in medically supervised places or with other people they know was also identified frequently among the participants. Participants talked about the enhanced safety of people consuming substances in safe injection sites or supervised consumption facilities; however, they also expressed concern that these sites may not be nearby or accessible to all people who use substances. Participants also discussed instances of people consuming substances with or around other people who may be unaware of the signs of a substance-related acute toxicity event and therefore unable to identify and respond to those signs.

Organizing theme 3: Why are people experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?

Four themes were identified in “Why are people experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death?”—unknown substances, substance use disorder, history of chronic pain and decreased drug tolerance.

C/MEs talked about people dying because they consumed unknown substances, and the substances consumed were contaminated with undisclosed components (e.g. fentanyl or carfentanil). One participant noted that no one was safe from substance-related acute toxicity deaths:

My subjective feeling actually is that even the [people using substances] sometimes don’t know what they are using because it is clear sometimes in the history that they certainly expected to be doing one kind of drug and they seemed to have others in their system that really ought not to have been there based on the expectation of the user. (S055 NS)

The theme “substance use disorder” focussed on cases that involved chronic use or a history of substance use. Some deaths had been preceded by one or more nonfatal substance-related acute toxicity events. A participant noted

In all the cases that I’ve investigated either chronic drug use or drug use in their history is a contributing factor. Another risk factor ... alcohol use ... sometimes it’s not found in the toxicology, we hear that in their history, we hear that from their families. ... We also see ... simultaneous use of the illicit drugs or the opiates, it may be fluctuating, so when they’re not using the alcohol they’re using the drugs, but I do see that in a lot of the cases, in their history, is alcohol use, and usually it’s chronic. (S041 SK)

Acute toxicity deaths were also attributed to a history of chronic pain, with people who began taking medications because of an injury or previous surgery then struggling with chronic pain and pain management, or not being provided with alternatives when medications were discontinued, as illustrated below:

You know for the chronic pain it has been ... in the ones that you know had been prescribed medication prior for chronic pain, injuries, but then were taken off the medication. ... And as the investigators we look in the records; it doesn’t appear that they were offered another solution or another assistance, you know. (S023 NWT)

Decreased tolerance was identified as a significant theme associated with substance-related acute toxicity death. C/MEs talked about people experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death after a recent release from a correctional facility, a treatment centre or health care facility because their drug tolerance was reduced from not using substances for a period of time. Some participants described decreased tolerance following a recent release from jail or not using for a while and then “testing the waters”:

The problem of a person getting out of [a correctional facility] ... then using is kind of a consistent one. We don’t get a huge number but we get ... a half dozen a year pretty consistently which suggests to me at least a point of intervention. ... And I think that the issue is that in [correctional facilities] access to their preferred drugs may have been somewhat limited. ... But then they get out ... the types and the numbers of drugs that they have access to obviously changes and that change in access is something lethal. ... I don’t think it is very numerous but it sort of sticks out in my head. (S055 NS)

Organizing theme 4: What are the social contextual factors contributing to deaths?

Four themes were identified in the organizing theme “What are the social contextual factors contributing to deaths?” including: mental health, stigma, lack of support and lack of coordinated health care follow-up. C/MEs across the country also noted that some of the deaths they investigated were of individuals who were experiencing more than one of these factors concurrently.

Within the theme “mental health,” mental ill-health was a significant focus of discussion regarding the contextual risk factors and characteristics of people who experienced a substance-related acute toxicity death. These factors included diagnosed, undiagnosed and untreated mental illness.

With respect to mental health problems, from what I can see ... are the problems that are known and diagnosed ... the person is seeing a psychiatrist or a psychologist or a family doctor ... receives medication. ... It can be depression. It can be psychosis. It can be a personality disorder. ... It usually involves one of those things. ... Or it’s someone who obviously has a mental health problem, but who hasn’t been diagnosed. Because the person hasn’t seen anyone. (S062 QC)

Other participants talked about patterns of complex and interrelated factors, including the connections between mental ill-health, pain and medications, prescribed and not prescribed:

People who are in pain ... fibromyalgia, depression ... there’s like a pattern there ... living all alone ... often addicted to alcohol ... have chronic pain ... back pain or suffer from fibromyalgia ... have had episodes of depression ... you usually find them with medications that were not prescribed. (S090 QC)

I had another death ... a man who ... was a truck driver ... he got into an accident ... went to emergency ... he was taking antidepressants and had symptoms of depression. ... But he wasn’t taking narcotics, he didn’t have substance [use] problems ... the doctor prescribed him ... he had never seen him, it was in emergency ... enough narcotic pills for him to commit suicide. And that is what happened. That very night, he took them all. (S084 QC)

Mental ill-health was also linked, for some, to previous sexual or physical trauma and thoughts of suicide or previous suicide attempts. Feelings of hopelessness and feelings of loss were illustrated in this quote:

Well, I think those that are struggling with hopelessness and sadness, and that’s where the mental health picture comes in ... many of these folks that have been struggling with drug use ... alienated from their families either by choice or by their family members’ choice because they’re tired of having things stolen and jewelry pawned. ... They’ve had their children removed ... lost jobs, partners ... they’ve just lost ... so with that comes a sense of hopelessness. When you’re struggling with perhaps some childhood trauma issues on top of that, what’s the easiest thing to do? It’s just to keep using because it’s so overwhelming for that person to see a light. (S026 BC)

Within the theme “stigma,” C/MEs described how people were struggling with multiple stressors and may have been at a higher risk of experiencing a substance-related acute toxicity death. One participant talked about the stress that people deal with when they are struggling and trying to navigate the stigma associated with substance use and accessing care:

So now they are out on the street and they are trying to find the drugs they need because of the addiction and it is a complicated ... there’s no harm reduction and there’s so much stigma in health, and I still see it today ... it is one of the things that really concerns me. (S023 NWT)

Lack of support was highlighted as a risk for an acute toxicity death because the deaths the C/MEs investigated were often of people who were estranged from their families or did not have access to programs or services, which increased their risk of experiencing death. One participant stated:

For some of these folks who want to access trauma counselling, do you have any idea what the waits are like? They are ridiculous, and these folks, many are on income assistance, don’t have means of paying for counselling services, so they go on these ridiculous waits, like months of waiting. (S026 BC)

C/MEs identified a lack of follow-up from health care as a contextual risk factor for a substance-related acute toxicity death. Participants described cases in which people had not received or been able to access coordinated follow-up care after having contact with the health care system, such as emergency room visits, repeated visits for pain control to their physician or another physician and requests to refill medications early. As noted by one participant:

I think there’s been a number of cases where they had psychiatric involvement and there perhaps was a loss of follow-up or maybe ... the patient didn’t attend or they lost contact with their psychiatrist and so were not on their usual medications. (S079 ON)

Other participants noted repeated emergency room visits were a possible pattern in substance-related acute toxicity death, such as in this quotation referring to emergency room release:

They’re brought in by ambulance and there is no one there for them. What do they do? ... You’re putting a small band-aid on somebody coming in, making sure that they’re still breathing, giving them their naloxone injection, then away you go. Well, what have you done to prevent that person from coming back in tomorrow? (S026 BC)

C/MEs also stated that lack of coordination between social and health services and barriers related to fees could be contextual risk factors for substance-related toxicity death.

Discussion

C/MEs observed increases in the numbers of people experiencing acute toxicity deaths and identified that deaths occurred across a wider range of profiles compared to prior years, including among people who used substances on occasion, on a regular or chronic basis, for the first time or to manage chronic pain. These changes were largely attributed, by C/MEs, to changes in the composition and potency of the substances consumed. C/MEs described how substances may have been contaminated with fentanyl, fentanyl analogues and other novel synthetic opioids that were not disclosed, which aligns with the literature from the US contextFootnote 26 and from drug-checking services’ analyses in Vancouver, Canada.Footnote 27

Consistent with analyses from provincial and international data sources, which have shown that many cases of acute toxicity deaths involved people using alone,Footnote 19Footnote 28 these findings also tell us that people consuming substances alone are at risk of death because there may be no one to respond or call for help. C/MEs discussed how people who consumed substances alone often lived alone and may have been isolated or marginalized. These themes align with studies conducted in British Columbia that have reported that common factors associated with using alone include having no one to use with or no other choice; comfort and convenience; safety; material or resource constraints; lack of secure housing; and experiencing stigma or not wanting others to know about drug use.Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31 However, most studies on this topic have focussed on people who access harm reduction or supervised injection services and may not generalize to people who are not connected with these services and who may be more likely to use alone.

In addition to using alone, participants mentioned that using with others may also contribute to risk, if they are not able to respond or to recognize the signs of overdose. A study of peer witnesses to substance-related acute toxicity events in Wales described how peers had the capacity to respond, but that contextually specific factors could prevent or delay a response; such factors would include, for example, signs going unnoticed (e.g. a peer mistakenly assuming an unconscious person was asleep).Footnote 32

Our findings illustrated several interrelated themes concerning the contextual factors that may have contributed to deaths, including contaminated substances, diagnosed or undiagnosed mental illness, history of substance use, history of chronic pain, decreased substance tolerance, lack of support from family or friends or inability to access programs or support services, and stigma associated with substance use.

The theme of stigma, which emerged from the complex and broad range of information obtained across C/MEs’ death investigations, further corroborates previous research that has highlighted stigma as an important factor in the context surrounding acute toxicity deaths.Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35 There are multiple dimensions of stigma associated with substance use (internalized, enacted, structural, public and anticipated) that can contribute to negative outcomes, including increased stress, concealing substance use, isolation and decreased access to or engagement with health services.Footnote 35Footnote 36 C/MEs discussed how people may have experienced isolation, stress, limited support (e.g. from friends, family or targeted programs and services), and may have lacked access to coordinated health services and follow-up after repeated contacts (e.g. multiple emergency room visits).

Several of the circumstances and contextual factors identified by C/MEs are also consistent with previous qualitative studies conducted with family or friends of people who died from the acute toxic effects of opioids or other substances in the United States and in the United Kingdom, including history of substance use,Footnote 18Footnote 1 diagnosed or undiagnosed mental illness,Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19 lack of support,Footnote 18 history of chronic pain,Footnote 17Footnote 18 repeated visits for pain control to physiciansFootnote 17 and decreased substance tolerance.Footnote 19 Many of these factors may occur in combination; for example, Yarborough et al.Footnote 18 found that mental illness, unstable social support, history of chronic pain and lack of adequate pain management were common factors among people who experienced an acute toxicity event. Quantitative research has demonstrated that many of these factors (e.g. decreased tolerance after release from a correctional, health care or treatment facility,Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39 mental illness and substance use disordersFootnote 40) are associated with the risk of acute toxicity events; however, these analyses have typically been limited to one or two of these factors. Our findings illustrate that there are often multiple contextual factors and how these may intersect, which highlights the need for a better understanding of patterns of factors that may increase risk of fatal acute toxicity events.

Strengths and limitations

Previous literature that has characterized substance-related acute toxicity deaths in Canada has largely been limited to quantitative analyses with limited data on contextual factors or analyses involving a single province or region. This study builds upon previous literature by providing an in-depth exploration of the multifaceted contextual factors that are common across the country from an underutilized source of expert information. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study including most provinces and territories in Canada that explores the perspectives of C/MEs to enhance understanding of the circumstances surrounding deaths from the acute toxic effects of opioids or illegal substances.

There are several limitations to this research. Not all C/MEs were interviewed in each participating province or territory, and not all Canadian provinces and territories were represented in this study. Thus, the views presented here represent only a small subset of the Canadian death investigation community. It is acknowledged that the perceptions of participating C/MEs may differ from those of nonparticipating C/MEs.

Because C/MEs were asked to informally aggregate information from multiple cases together, recall bias may have been a result, since the most acute, proximal or disturbing cases may be more memorable than others. Similarly, responses may be biased regarding changes over time, as opioid information has recently become plentiful and highly publicized, potentially influencing responses. Personal bias related to interventions and risk factors may have influenced the responses offered; however, professionalism may have mitigated this limitation. Finally, this study is a snapshot of the risk factors and characteristics of those who died at the time when the interviews took place, between December 2017 and February 2018. As circumstances evolve, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the context surrounding drug toxicity deaths, more research will be needed to shed light on how these contextual risk factors and characteristics may change.

Conclusion

Our study provides the perspectives of C/MEs across Canada on the contextual risk factors and characteristics surrounding deaths from the acute toxic effects of opioids or illegal substances. There is limited pan-Canadian evidence on these factors, and the use of C/MEs to describe this context is not well documented in the literature. C/MEs highlighted the changing epidemic and identified a range of interrelated characteristics and circumstances that appear to be associated with substance-related acute toxicity deaths. These findings offer a national snapshot of the multifaceted factors that surround such deaths, which allows for triangulation with previous analyses that have focussed on a single province or quantitative analyses that included limited factors and contextual description. The themes presented in this study offer a more in-depth understanding of the complex circumstances that contribute to substance-related acute toxicity deaths and can provide insight into targeted prevention and intervention efforts designed to mitigate these events and deaths.

Future research should focus on further collaboration and investigations with C/MEs to advance our understanding of substance-related acute toxicity deaths and inform action in this area. Moreover, further studies should examine the lived and living experiences and perspectives of those most affected by or involved with people who consume opioids or illegal substances. Understanding their experiences and perceptions of what actions could be taken may help to provide a broader picture of the context surrounding an individual’s life and address priority information needed to help inform education, awareness and interventions to prevent substance-related acute toxicity events and deaths.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants from the British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Northwest Territories coroner and medical examiner offices for taking the time to share their knowledge and thoughtful reflections on their experiences. We also thank all members of the Opioid Overdose Surveillance Task Group and the National Forum of Chief Coroners and Chief Medical Examiners for their input and feedback.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada and completed as a project of the Epi-Study Working Group of the Public Health Network Council’s Special Advisory Committee’s (SAC) Opioid Overdose Surveillance Task Group (OOSTG), which includes representation from all provinces and territories.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

JR and JH designed and conceptualized the study and critically revised the paper.

TT conducted interviews, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted and revised the paper.

JL conducted interviews, analyzed and interpreted the data and critically revised the paper.

JMH, DH, LL and MK were involved in the study design and critically revised the paper.

HO and AE analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised the paper.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.