Original quantitative research – The trends and determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination after cardiovascular events in Canada: a repeated, pan-Canadian, cross-sectional study

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: February 2023

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Hanna Cho, PharmD; Sherilyn K. D. Houle, PhD; Mhd. Wasem Alsabbagh, PhD

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.2.04

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

School of Pharmacy, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence

Mhd. Wasem Alsabbagh, School of Pharmacy, University of Waterloo, 10A Victoria St. S., Kitchener, ON N2G 1C5; Tel: 519-888-4567 ext. 21382; Fax: 519-883-7580; Email: wasem.alsabbagh@uwaterloo.ca

Suggested citation

Cho H, Houle SKD, Alsabbagh MW. The trends and determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination after cardiovascular events in Canada: a repeated, pan-Canadian, cross-sectional study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(2):87-97. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.2.04

Abstract

Introduction: Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for individuals with a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. We aimed to examine (1) the time trends for influenza vaccination among Canadians with a CVD event history between 2009 and 2018, and (2) the determinants of receiving the vaccination in this population over the same period.

Methods: We used data from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). The study sample included respondents from 2009 to 2018 who were 30 years of age or more with a CVD event (heart attack or stroke) and who indicated their flu vaccination status. Weighted analysis was used to determine the trend of vaccination rate. We used linear regression analysis to examine the trend and multivariate logistic regression analysis to examine determinants of influenza vaccination, including sociodemographic factors, clinical characteristics, health behaviour and health system variables.

Results: Over the study period, in our sample of 42 400, the influenza vaccination rate was overall stable around 58.9%. Several determinants for vaccination were identified, including older age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 4.28; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 4.24–4.32], having a regular health care provider (aOR = 2.39; 95% CI: 2.37–2.41), and being a nonsmoker (aOR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.47–1.49). Factors associated with decreased likelihood of vaccination included working full time (aOR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.72–0.72).

Conclusion: Influenza vaccination is still at less than the recommended level in patients with CVD. Future research should consider the impact of interventions to improve vaccination uptake in this population.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, influenza vaccines, utilization, secondary prevention, trend, determinants

Highlights

- Vaccine uptake in the post-CVD Canadian population from 2009 to 2018 was found to be suboptimal and is a potential area for optimization of health outcomes in these patients.

- Factors associated with increased likelihood of vaccination include older age, having a regular health care provider and being a nonsmoker.

Introduction

Annual vaccination against influenza is recommended for all individuals with a history of an ischemic cardiovascular disease (CVD) event.Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5 Seasonal influenza infection further elevates the already increased risk of recurrent CVD events and deaths in this particular population.Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9 Although the exact mechanism is unknown, this increased risk from influenza infection is believed to be the result of viral particles activating inflammatory pathways, which can contribute to dysfunctions in arterial endothelium and lipid metabolism and lead to coronary atherosclerotic events such as myocardial infarction and stroke.Footnote 6Footnote 10Footnote 11 Empirical evidence supports the efficacy of influenza vaccine in the secondary prevention context.Footnote 12Footnote 13 In a systematic review of randomized clinical trials, influenza vaccination was associated with a 36.0% reduction in future CVD events, with a relative risk of 0.6 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.5–0.9).Footnote 12

In Canada, annual influenza vaccines are widely available in pharmacies, physician offices and local public health units.Footnote 14 Public funding of the vaccine is also provided for those with chronic conditions, including CVD, in all 13 Canadian jurisdictions.Footnote 15 Despite this availability, the uptake of influenza vaccine among patients with CVD remains low.Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 17Footnote 18 Data from the 2019/20 influenza season revealed the proportion of vaccinated Canadian adults with one or more chronic conditions (including CVD) was 44.0%, well below the 80.0% target set by the National Advisory Committee on Immunizations (NACI).Footnote 18 However, time trends of vaccination rates in Canadians specifically with a previous CVD event history are unknown.Footnote 18

There is also inadequate evidence pertaining to the determinants of vaccine uptake in patients with CVD. Studies usually focus on determinants either in the general population or in patients suffering from chronic conditions as a whole, but not CVD specifically.Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23 Older age was found to be significantly associated with a higher rate of vaccine uptake in the general population of the United States, Canada, Italy and Portugal.Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 23 In countries such as the United States, where the cost of influenza vaccinations may not be covered by the government, individuals with higher occupational and educational status were more likely to be vaccinated than those with lower incomes.Footnote 22Footnote 24 Aside from cost, other factors such as systemic racism and a reduced degree of prioritization by clinicians and the health care system may hinder patients’ access to the influenza vaccine. Although these factors may also exist in Canada, findings from the United States are not directly applicable to the Canadian population, due to differences in demographics and health care coverage.Footnote 19

It is important to identify the time trend and determinants of influenza vaccination in Canadian patients after CVD events to inform effective strategies, to help determine whether current policies are sufficient and to what extent there is a need to further improve influenza vaccine uptake among these high-risk patients.Footnote 25Footnote 26 The aim of this study was to identify the trend for the period of 2009 to 2018, as well as the determinants of receiving influenza vaccine among Canadian patients with a previous CVD event. We hypothesized that influenza vaccine uptake is increasing in Canada.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the Public Use Microdata Files (PUMF) of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)Footnote 27 to conduct this study. We accessed the data through the Ontario Data Documentation, Extraction Service and Infrastructure (“odesi”) tool.Footnote 28 The CCHS is a voluntary, cross-sectional survey of noninstitutional Canadian residents aged 12 years and older, used to obtain health-related information representative of different health regions across Canada.Footnote 27 The data are collected year-round. Subject areas of interest include various health conditions, utilization of health care services, lifestyle factors and mental health.Footnote 27

The CCHS utilizes a complex, two-stage, stratified cluster design to sample those 18 years of age and over in the Labour Force Survey while using a simple, random sample to query children aged 12 to 17 years.Footnote 27 A letter from Statistics Canada inviting participation in the survey is mailed to respondents; those who agree are then directed to an online questionnaire.Footnote 27 Together, those excluded from the sample make up less than 3% of the Canadian population.Footnote 27 The PUMF from CCHS compiles responses from approximately 130 000 individuals over a two-year period, published as a microdata file biennially.Footnote 27Footnote 29

For this study, we included CCHS data from the 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016 and 2017–2018 cycles. The variables concerning influenza vaccination and all exposure variables used in this study were core content in the CCHS documentation, signifying that the variables were asked in all Canadian provinces and territories.Footnote 27 We applied weights provided in the Statistics Canada datasets to all data analyzed and presented in this study.Footnote 27 As per Statistics Canada, the survey weights are determined by a combination of modelling probabilities of response at the household and person levels, and correlates to the number of persons in the Canadian population represented by each respondent.Footnote 27

Study population

We included respondents from the 2009 to 2018 CCHS who indicated that they were 30 years of age or older, had experienced a CVD event and who answered questions pertaining to influenza vaccinations. CVD event history was assessed using the survey questions “Do you have heart disease?” and “Do you suffer from the effects of a stroke?” Respondents who answered “yes” to either one or both questions were included in the study. Although it was not established through hospitalization records that all respondents indicating presence of heart disease or stroke had in fact experienced an ischemic CVD event, it was considered a reasonable indicator to be used for this study. Individuals below 30 years of age were excluded from this study due to the extremely low prevalence of heart disease in this age group and differences in etiology compared to older adults (i.e. higher proportion of non-atherosclerotic causes of CVD).Footnote 30

Vaccination status

Respondents were considered vaccinated for the influenza season if they have indicated “yes” to the question “Have you ever had a flu shot?” and have also indicated “< 1 year ago” to the question “When did you last receive the vaccine?” As the influenza vaccine is recommended annually, respondents who had had the flu shot but indicated “1–2 years ago” or “2 or more years ago” as the last time they received the vaccine, as well as those who had indicated “no” to the question “Have you ever had a flu shot?”, were considered unvaccinated in this study. The remaining respondents who indicated “don’t know” or “unsure” to any of the above questions, or refused to answer, were all considered unvaccinated.

Measurement and confounding variables

Various independent variables were chosen to identify potential determinants of the outcome of interest (i.e. being vaccinated). We included sociodemographic factors related to age, sex, marital status, income, education level, immigrant status and employment status, based on previous findings for their correlation to vaccination among the general population.Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 23 In addition, we included the cycle year and chronic diseases variables. We also included variables pertaining to smoking status and body mass index (BMI)—calculated by Statistics Canada—to study the impact of various health-related factors, as well as a variable assessing self-perceived health, with responses ranging from “poor” to “excellent.”Footnote 31 Further, the variables of having a regular health care provider and requiring help with personal care were included to evaluate health care and external aid utilization. Whether or not respondents resided in provinces or territories allowing pharmacists to provide immunizations was also assessed, due to recent evidence showing that Canadian jurisdictions that had implemented this policy saw increased influenza vaccination rates.Footnote 32 Details about included variables are available in Appendix 1.

Data analysis

The weighted rate of respondents in the overall CVD population who received influenza vaccination (i.e. the proportion of respondents vaccinated) across the study period from 2009 to 2018 was first plotted, along with the confidence interval. The same procedure was then repeated to plot the vaccination rate of respondents in the overall CVD population over time stratified by province. These data plots were then analyzed utilizing the linear regression analysis test in Microsoft Excel version 16.43 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, US) to determine the significance of any trends in receiving vaccination over the study years.

Next, descriptive statistics were calculated for patients who were vaccinated versus those who were unvaccinated. The association between each independent variable and receipt of influenza vaccine was examined using the chi-square (χ2) test of independence. Similar to previous research, a weighted multivariable logistic regression model was then fitted using a stepwise forward-selection model.Footnote 33 The independent variables in the final model were included based on significance (p < 0.05) from the Wald statistic and goodness of fit using the Akaike information criterion. Selected variables—cycle year, age and sex—were included in the model regardless of statistical significance. Patients with missing data were dealt with first by listwise deletion approach (only respondents with complete data in all variables were kept in the analysis).Footnote 34 In a sensitivity analysis, we used the educated-guessing approach, in which variables with missing values are replaced with “no” in binary variables or by the lowest level (in ordinal variables).

Using weighted results, a second sensitivity analysis was performed in order to evaluate the robustness of the study definition for vaccination status. In the main model, respondents were considered vaccinated only if they had indicated having received the flu shot less than one year ago. This definition, however, excludes those who received the flu shot exactly one year ago or just over one year ago but who would still go on to be vaccinated for the upcoming influenza season. Therefore, in this sensitivity analysis, we considered respondents vaccinated as long as they had received the influenza vaccine less than two years before the survey date. This is because influenza vaccination is recommended annually during the influenza season to protect against new strains of the influenza virus. However, because the CCHS collects data annually, the questions pertaining to vaccination status may be referring to either year of a two-year cycle.

Several subgroup analyses were also performed to identify any differences in determinants for vaccination based on age group and type of CVD event (e.g. stroke only). The same independent variables and statistical procedure applied to the main model were used to perform the subgroup analyses.

SAS University Edition (SAS Studio version 3.8, SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US) was utilized to analyze the survey data. Due to the fact that the data are publicly available through Statistics Canada,Footnote 27 there was no need for research ethics board approval to conduct this study. All numbers presented are rounded to the closest 100, as per Statistics Canada rounding guidelines.Footnote 35

Results

Descriptive statistics

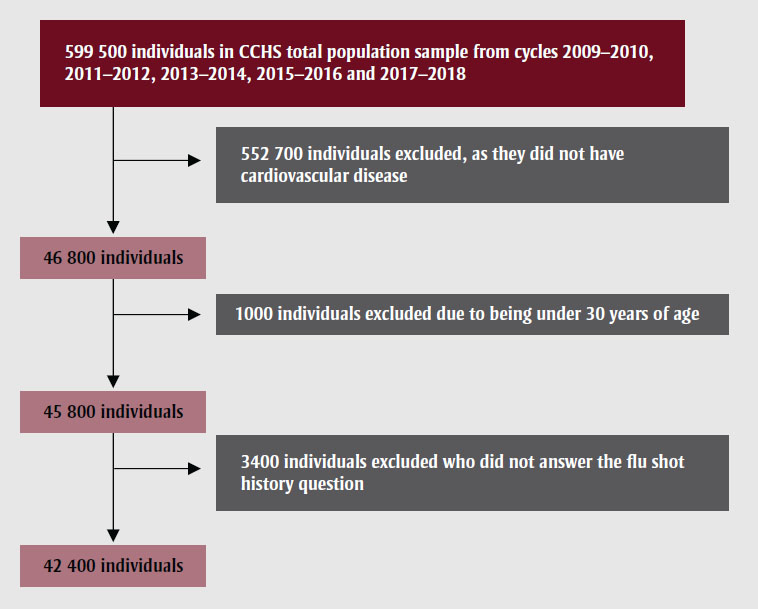

The study sample included a total of 42 400 respondents, representing a weighted population of 7 148 500 Canadians, from the CCHS cycles 2009–2010 to 2017–2018, residing in all 10 Canadian provinces and 3 territories. Figure 1 illustrates the process taken to determine the final study sample. Most respondents (81.0%) had heart disease only, 13.0% had a history of a stroke and the remaining 6.0% had both. In the total weighted sample of 42 400 respondents, 58.9% had received influenza vaccination. More than half of the sample population (58.0%) were aged 65 and older, and 56.0% were males. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the study weighted sample. Vaccinated individuals were generally older in age, were married and had other comorbidities. A low level of missingness was observed (Appendix 2) in all independent variables (< 3%) and most variables had less than 1% missingness.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure represents the selection process of study respondents, from the following starting sample:

599 500 individuals in CCHS total population sample from cycles 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016 and 2017–2018.

552 700 individuals were excluded, as they did not have cardiovascular disease, leaving 46 800 individuals.

Of those, 1000 individuals were excluded due to being under 30 years of age, leaving 45 800 individuals.

Of those, 3400 individuals were excluded because they did not answer the flu shot history question.

This led to a final sample of 42 400 individuals.

Data source: Canadian Community Health Study (CCHS), 2009–2010 to 2017–2018.

| Respondent characteristics | Vaccination statusFootnote a | P values from chi-square test of independence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated

n = 2 939 900 (column %) |

Vaccinated n = 4 208 600 (column %) | Total N = 7 148 400Footnote b (column %) | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 30–44 | 267 300 (9%) | 107 200 (3%) | 374 400 (5%) | < 0.0001 |

| 45–64 | 1 445 900 (49%) | 1 163 200 (28%) | 2 609 100 (36%) | |

| 65 and above | 1 226 700 (42%) | 2 938 200 (70%) | 4 164 900 (58%) | |

| Has heart disease only | ||||

| Yes | 2 327 200 (79%) | 3 475 800 (83%) | 5 803 000 (81%) | < 0.0001 |

| Suffers from effects of a stroke only | ||||

| Yes | 426 600 (15%) | 465 900 (11%) | 892 500 (13%) | < 0.0001 |

| Has heart disease and suffers from effects of a stroke | ||||

| Yes | 186 200 (6%) | 266 800 (6%) | 453 000 (6%) | 0.9829 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 239 700 (42%) | 1 922 000 (46%) | 3 161 700 (44%) | 0.0002 |

| Cycle year | ||||

| 2009–2010 | 576 000 (20%) | 837 700 (20%) | 1 413 600 (20%) | 0.0007 |

| 2011–2012 | 587 000 (20%) | 877 900 (21%) | 1 464 900 (20%) | |

| 2013–2014 | 567 900 (19%) | 906 800 (22%) | 1 474 700 (21%) | |

| 2015–2016 | 578 100 (20%) | 799 600 (19%) | 1 377 700 (19%) | |

| 2017–2018 | 631 000 (21%) | 786 600 (19%) | 1 417 600 (20%) | |

| Requires help with personal care | ||||

| Yes | 82 700 (3%) | 172 900 (4%) | 255 600 (4%) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Daily smoker | 562 000 (19%) | 441 500 (10%) | 1 003 500 (14%) | < 0.0001 |

| Occasional smoker | 109 800 (4%) | 95 000 (2%) | 204 800 (3%) | |

| Former smoker | 1 484 400 (50%) | 2 416 000 (57%) | 3 900 400 (55%) | |

| Never smoked | 454 400 (15%) | 756 000 (18%) | 1 210 300 (17%) | |

| Self-perceived health | ||||

| Not poor | 2 552 300 (87%) | 3 633 100 (86%) | 6 185 300 (87%) | 0.3403 |

| Poor | 377 000 (13%) | 565 200 (13%) | 942 200 (13%) | |

| Has diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 574 700 (20%) | 1 129 000 (27%) | 1 703 700 (24%) | < 0.0001 |

| Has asthma | ||||

| Yes | 287 100 (10%) | 523 700 (12%) | 810 700 (11%) | < 0.0001 |

| Has COPD | ||||

| Yes | 283 100 (10%) | 558 000 (13%) | 841 100 (12%) | < 0.0001 |

| Has a regular health care provider | ||||

| Yes | 2 663 300 (91%) | 4 068 100 (97%) | 6 731 500 (94%) | < 0.0001 |

| Low-income group | ||||

| Yes | 938 700 (32%) | 1 316 100 (31%) | 2 254 800 (32%) | 0.4614 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/widowed/divorced | 1 073 000 (36%) | 1 437 700 (34%) | 2 510 700 (35%) | 0.0048 |

| Married | 1 858 600 (63%) | 2 764 400 (66%) | 4 623 100 (65%) | |

| Highest educational attainment | ||||

| Secondary and lower | 1 278 400 (43%) | 1 916 600 (46%) | 3 195 000 (45%) | 0.0367 |

| Postsecondary and higher | 1 568 900 (53%) | 2 169 800 (52%) | 3 738 700 (52%) | |

| Pharmacist immunization in province of residence | ||||

| Yes | 1 552 500 (53%) | 2 497 400 (59%) | 4 049 900 (57%) | < 0.0001 |

| Province of residence | ||||

| British Columbia | 334 400 (11%) | 531 700 (13%) | 866 000 (12%) | < 0.0001 |

| Alberta | 247 400 (8%) | 346 300 (8%) | 593 800 (8%) | |

| Saskatchewan | 88 500 (3%) | 124 700 (3%) | 213 200 (3%) | |

| Manitoba | 96 600 (3%) | 125 500 (3%) | 222 300 (3%) | |

| Ontario | 1 024 800 (35%) | 1 761 000 (42%) | 2 785 800 (39%) | |

| Quebec | 916 800 (31%) | 901 800 (21%) | 1 818 700 (25%) | |

| Atlantic provinces | 223 700 (8%) | 409 100 (10%) | 632 800 (9%) | |

| Territories | 7 600 (0%) | 8 300 (0%) | 15 900 (0%) | |

| BMI | ||||

| < 25 | 996 400 (34%) | 1 429 800 (34%) | 2 426 200 (34%) | 0.9008 |

| ≥ 25 | 1 877 600 (64%) | 2 680 300 (64%) | 4 557 900 (64%) | |

| Immigrant status | ||||

| Yes | 639 700 (22%) | 925 200 (22%) | 1 564 900 (22%) | 0.8963 |

| Full-time worker | ||||

| Yes | 916 000 (31%) | 651 000 (15%) | 1 567 100 (22%) | < 0.0001 |

Trends in vaccination

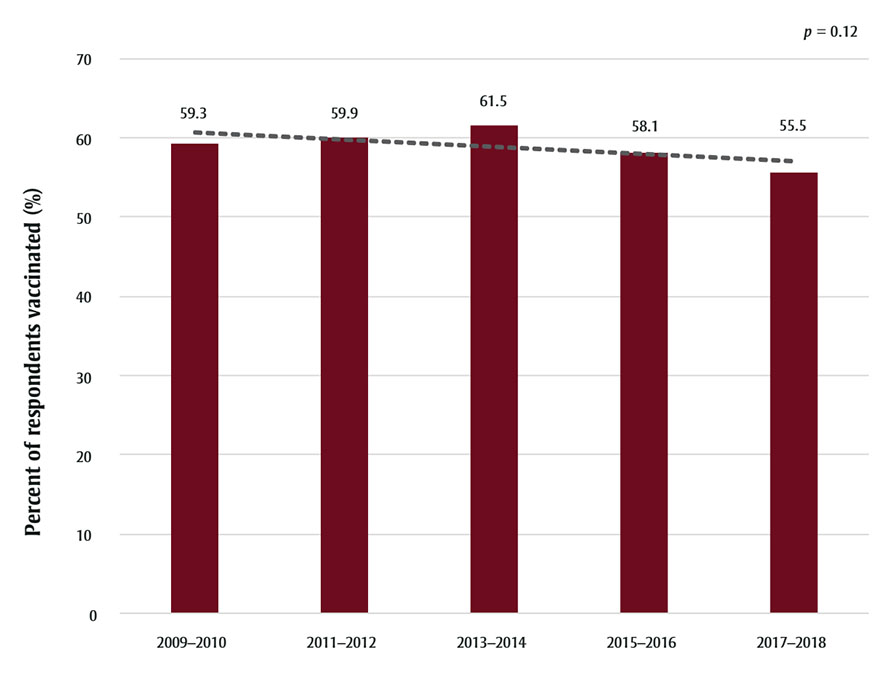

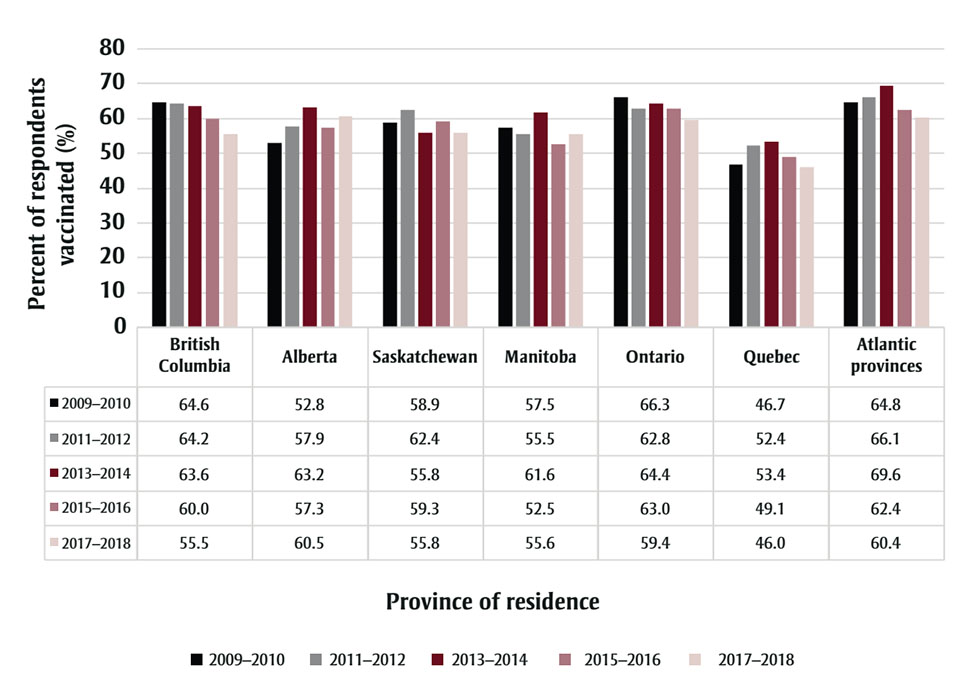

Figure 2 illustrates the weighted proportion of respondents with CVD events vaccinated against influenza from 2009 to 2018. Over the ten-year study period, there was a general downward trend in the proportion of vaccinated individuals with a history of a CVD event, from 59.3% (95% CI: 59.2–59.4) in the 2009–2010 cycle to 55.5% (95% CI: 55.4–55.6) in the 2017–2018 cycle. Vaccination rates peaked in the 2013–2014 cycle, with 61.5% (95% CI: 61.4–61.6) of respondents indicating vaccination against influenza. However, the trend line was not significant (p value = 0.12). Figure 3 illustrates the breakdown of vaccination trends within the Canadian provinces. Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia saw a general decrease in vaccination rates, while Alberta experienced an overall increase over the study period. Quebec consistently remained the province with the lowest percentage of respondents vaccinated.

Figure 2 - Text description

| Year | Percent of respondents vaccinated (%) |

|---|---|

| 2009–2010 | 59.3 |

| 2011–2012 | 59.9 |

| 2013–2014 | 61.5 |

| 2015–2016 | 58.1 |

| 2017–2018 | 55.5 |

Data source: Canadian Community Health Survey.

Abbreviation: CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Figure 3 - Text description

| Year | British Columbia | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Quebec | Atlantic provinces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009–2010 | 64.6 | 52.8 | 58.9 | 57.5 | 66.3 | 46.7 | 64.8 |

| 2011–2012 | 64.2 | 57.9 | 62.4 | 55.5 | 62.8 | 52.4 | 66.1 |

| 2013–2014 | 63.6 | 63.2 | 55.8 | 61.6 | 64.4 | 53.4 | 69.6 |

| 2015–2016 | 60.0 | 57.3 | 59.3 | 52.5 | 63.0 | 49.1 | 62.4 |

| 2017–2018 | 55.5 | 60.5 | 55.8 | 55.6 | 59.4 | 46.0 | 60.4 |

Determinants of receiving influenza vaccination

The variables that were retained in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, in addition to age, cycle year and sex, were smoking status, presence of comorbidities (diabetes, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), marital status, working status, highest educational attainment, requiring help for personal care and having a regular health care provider (Appendix 3). The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of the variables controlled for in the final main model are listed in Table 2. Age of 65 years or older was associated with the greatest odds of receiving influenza vaccination, with an aOR of 4.28 (95% CI: 4.24–4.32) and having a regular health care provider was also associated with increased odds (aOR = 2.39; 95% CI: 2.37–2.41).

| Effect | Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) estimation | 95% Wald confidence limits |

|---|---|---|

| 2011–2012 vs. 2009–2010 | 1.05 | 1.04–1.05 |

| 2013–2014 vs. 2009–2010 | 1.10 | 1.09–1.10 |

| 2015–2016 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.96 | 0.95–0.96 |

| 2017–2018 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.80 | 0.79–0.80 |

| Sex: female vs. male | 1.06 | 1.06–1.07 |

| Age: 45–64 vs. 30–44 | 1.73 | 1.72–1.75 |

| Age: 65 and older vs. 30–44 | 4.28 | 4.24–4.32 |

| Require help with personal care: yes vs. no | 1.11 | 1.10–1.11 |

| Smoking: no vs. yes | 1.48 | 1.47–1.49 |

| Diabetes: yes vs. no | 1.37 | 1.37–1.38 |

| Asthma: yes vs. no | 1.36 | 1.35–1.37 |

| COPD: yes vs. no | 1.32 | 1.31–1.32 |

| Marital status: married vs. single/widowed/divorced | 1.25 | 1.25–1.26 |

| Work full time: yes vs. no | 0.72 | 0.72–0.72 |

| Has a regular HCP: yes vs. no | 2.39 | 2.37–2.41 |

| Educational attainment: postsecondary and higher vs. secondary and lower | 1.10 | 1.09–1.10 |

Subgroup analysis

Results of the subgroup analyses stratified by age revealed some differences in the aORs for the following variables: COPD, requiring help with personal care and working status. Respondents in the youngest age group (aged 30–44) were approximately four times more likely to receive the influenza vaccination if they had COPD than those without COPD (aOR = 4.6; 95% CI: 4.4–4.8), while respondents aged 45 and above with COPD had similar odds of vaccination as in the main model (aOR = 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1–1.2). Respondents in the youngest age group requiring help with personal care had an aOR of 2.7 (95% CI: 2.6–2.9), while requiring help with personal care was not associated with vaccination in respondents aged 45 to 64. The odds of vaccination were also increased in respondents working full time between 30 and 44 years of age (aOR = 2.5; 95% CI: 2.5–2.6) while respondents working full time older than 45 years of age had a decreased likelihood of vaccination (aOR = 0.8; 95% CI: 0.8–0.8). The remaining variables remained consistent with the results of the main model across all age groups (Table 3). In a second subgroup analysis on respondents suffering from the effects of a stroke only, findings were similar to the results of the main model (Table 4).

| Effect | Ages 30–44 y | Ages 45–64 y | Ages 65 y and above | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio estimation | 95% Wald confidence limits | Adjusted odds ratio estimation | 95% Wald confidence limits | Adjusted odds ratio estimation | 95% Wald confidence limits | |

| 2011–2012 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.38 | 0.37–0.40 | 1.10 | 1.09–1.11 | 1.36 | 1.35–1.38 |

| 2013–2014 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.68 | 0.66–0.70 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 1.24 | 1.23–1.25 |

| 2015–2016 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.94 | 0.92–0.97 | 0.92 | 0.91–0.93 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 |

| 2017–2018 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.44 | 0.43–0.46 | 0.70 | 0.69–0.70 | 0.91 | 0.91–0.92 |

| Sex: female vs. male | 1.48 | 1.46–1.51 | 1.11 | 1.10–1.12 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.02 |

| Require help with personal care: yes vs. no | 2.34 | 2.22–2.45 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 1.13 | 1.11–1.14 |

| Smoking: no vs. yes | 1.35 | 1.32–1.39 | 1.25 | 1.24–1.25 | 1.78 | 1.76–1.79 |

| Diabetes: yes vs. no | 2.02 | 1.97–2.08 | 1.44 | 1.43–1.45 | 1.27 | 1.26–1.28 |

| Asthma: yes vs. no | 1.19 | 1.16–1.22 | 1.58 | 1.57–1.60 | 1.16 | 1.15–1.17 |

| COPD: yes vs. no | 3.16 | 3.04–3.28 | 1.18 | 1.17–1.20 | 1.36 | 1.35–1.37 |

| Has a regular HCP: yes vs. no | 3.00 | 2.91–3.11 | 2.55 | 2.52–2.58 | 2.36 | 2.33–2.39 |

| Marital status: married vs. single/widowed/divorced |

0.99 | 0.98–1.02 | 1.16 | 1.16–1.17 | 1.30 | 1.30–1.31 |

| Work full time: yes vs. no | 1.53 | 1.50–1.56 | 0.79 | 0.79–0.80 | 0.47 | 0.46–0.47 |

| Educational attainment: postsecondary and higher vs. secondary and lower |

1.12 | 1.10–1.15 | 1.15 | 1.15–1.16 | 1.09 | 1.09–1.10 |

| Effect | Adjusted odds ratio estimation | 95% Wald confidence limits |

|---|---|---|

| Ages (yr): 45–64 vs. 30–44 | 1.60 | 1.56–1.63 |

| Ages (yr): 65 and older vs. 30–44 | 3.68 | 3.60–3.77 |

| 2011–2012 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.67 | 0.66–0.69 |

| 2013–2014 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.79 | 0.78–0.80 |

| 2015–2016 vs. 2009–2010 | 1.06 | 1.05–1.08 |

| 2017–2018 vs. 2009–2010 | 0.68 | 0.67–0.69 |

| Sex: female vs. male | 1.20 | 1.19–1.21 |

| Require help with personal care: yes vs. no | 1.26 | 1.24–1.29 |

| Smoking: no vs. yes | 1.44 | 1.42–1.46 |

| Diabetes: yes vs. no | 1.55 | 1.53–1.57 |

| Asthma: yes vs. no | 1.64 | 1.61–1.66 |

| COPD: yes vs. no | 0.89 | 0.88–0.91 |

| Has a regular HCP: yes vs. no | 2.25 | 2.12–2.30 |

| Marital status: married vs. single/widowed |

1.28 | 1.27–1.29 |

| Work full time: yes vs. no | 0.52 | 0.51–0.53 |

| Educational attainment: postsecondary and higher vs. secondary and lower |

1.32 | 1.30–1.33 |

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis, in which respondents were considered vaccinated as long as they indicated vaccination less than 2 years ago, there were no extensive changes to the odds ratios compared to the main model (Appendix 4). Similarly, the educated-guessing approach for missing data yielded similar estimates (Appendix 5).

Discussion

We examined the trends and determinants of receiving influenza vaccination in individuals with a history of a CVD event in a representative sample from the Canadian population from 2009 to 2018. Over the study period, the percentage of respondents vaccinated each year remained generally stable (ranging from 55.5%–61.5%) and experienced no significant change (p = 0.12). Despite various attempts to improve vaccine uptake through national influenza vaccination campaigns and increased accessibility of vaccines through local pharmacies, vaccination rates remained below NACI’s 80% target for Canadians with chronic conditions.Footnote 18Footnote 32 This is a concerning finding, as annual influenza vaccinations are an easily accessible and cost-effective measure to reduce morbidity and mortality from CVD events.Footnote 25Footnote 32 The data demonstrate that, as in other jurisdictions, not enough post-CVD patients are utilizing this cardioprotective strategy in Canada.Footnote 23 Therefore, while national influenza vaccination campaigns distribute information for the general population, additional strategies to distribute information tailored to high-risk populations may be required.Footnote 36

Within the study period, vaccination rates peaked in 2013/14. A possible reason may be attributed to the implementation of funding and policy allowing pharmacists to administer influenza vaccines in Manitoba and Atlantic provinces that year.Footnote 19Footnote 32 This is also supported by the finding that Quebec had the lowest rates of vaccination throughout the study period, potentially explained by the absence of universal funding and pharmacist immunization policy for influenza vaccinations in this province.Footnote 32 However, there was no significant improvement in vaccine uptake from 2009, and in none of the study years was the target of 80% reached.Footnote 18

Consistent with previous studies, increasing age was associated with higher influenza vaccination rates.Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 23 Likewise, the presence of other comorbidities was another strong predictor for vaccination, and comorbidities also become more prevalent with age.Footnote 18 Older individuals and those with greater comorbidities are more readily perceived by health care providers to be at higher risk for complications from influenza, leading to greater frequency of recommendations and higher vaccination rates.Footnote 37 Increasing age may also be associated with increased self-perceived risk to complications of influenza infection, thereby influencing self-motivated vaccine uptake.Footnote 38

Individuals with a regular health care provider were more than twice as likely as those without one to receive vaccination. This supports findings that health care utilization is an important determinant for vaccination.Footnote 21Footnote 39 Yet, while 94% of individuals in our study reported having a regular health care provider, almost 40% were not vaccinated against influenza. This suggests a potential gap in communication between health care providers and patients regarding the cardioprotective benefits of the influenza vaccine.Footnote 25 Considering the significant impact of health care provider recommendations on vaccine uptake as demonstrated by numerous studies, a greater focus on patient education on vaccine benefits during all points of contact with the health care system (e.g. hospitalizations, follow-up visits) is warranted.Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42

We also found that nonsmokers across all age groups were more likely to receive influenza vaccination than smokers (OR = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.4–1.5). While there are some discrepancies in the literature,Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 37 57.0% of our vaccinated study population were noted to be former smokers. It is possible that former smokers who made the decision to quit smoking after a CVD event may be more inclined to take part in other preventative measures such as influenza vaccinations.Footnote 43 However, it is the current smokers who are at a higher risk for CVD events and have a higher incidence of CVD mortality than former smokers, and would therefore derive greater benefit from vaccination.Footnote 43

We found that Canadians with a CVD event aged 65 and older with higher educational attainment were more likely to be vaccinated. This supports the findings of several Canadian studies showing that higher educational status is a determinant for vaccination in the elderly.Footnote 37Footnote 44 On the other hand, higher educational attainment was linked to a decrease in odds of vaccination for those under 65 years of age, which is in line with the findings from previous studies in other countries.Footnote 20Footnote 45 This can be potentially explained by the association between higher education status and greater likelihood of working, rendering these individuals busier and potentially less able to conveniently access vaccination than those who are not working.Footnote 39 Lastly, our results suggest that future vaccination campaigns could benefit from directing efforts to the working population. Working full-time was associated with a decreased likelihood of vaccination among middle-aged respondents aged 45 to 64. Full-time workers may potentially be busier than their unemployed counterparts, contributing to greater difficulties with booking health care appointments or taking part in vaccination programs.Footnote 39

Strengths and limitations

Our study utilized representative data from the Canadian population collected over ten years. This enabled us to examine the trend determinants for vaccination and vaccine receipt in the past decade. However, some limitations should be noted.

First, CCHS relies on self-reporting, in which the responses may be subject to recall bias. Nevertheless, the CCHS questions pertaining to heart disease and stroke were validated and found to be robust. Lix et al. reported that these questions have very high specificity (> 96%) and negative predictive value (> 98%),Footnote 46 which would support the existence of heart disease in CCHS respondents who reported that they have heart disease. Regarding vaccination status, some respondents may have stated their last vaccination to be one to two years ago, when in actuality it was less than one year ago. This would have led them to be categorized as unvaccinated in the study, leading to an underestimation of the actual vaccination rate. It should be noted, however, that in the sensitivity analysis, expanding the window of vaccination to two years did not have an impact on the results.

Second, there were no specific questions asked in CCHS concerning history of CVD events. The question “Do you have heart disease?” encompasses many heart diseases, such as atrial fibrillation or heart failure, while the aim of this study was to look at only those with a history of an atherosclerotic cardiacvascular or cerebrovascular event.

Nevertheless, our results can be generalized to the Canadian public, as our sample was large, and the data collected over an extended period of time. In addition, sample weights provided by Statistics Canada provide a robust estimation of vaccination level among patients with heart disease.

Conclusion

In spite of the morbidity and mortality benefits of the annual influenza vaccination in patients with a history of a CVD event, influenza vaccination rates among Canadians are still suboptimal, and were found to be overall stable over the ten-year study period from 2009 to 2018.Footnote 18 Major determinants associated with vaccine uptake include increasing age, having a regular health care provider, having concurrent comorbidities, requiring help with personal care and being a nonsmoker. Future influenza vaccination campaigns should include messages directed at post-CVD patients, as well as groups associated with lower odds of vaccination, such as those employed full-time in the workforce and individuals under 65 years of age. The results of this study also re-emphasize the important role clinicians play in patient education and the recommendation of influenza vaccinations for improved vaccine uptake and health outcomes in the Canadian CVD population.Footnote 1

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributions and statement

HC: data acquisition, data analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. SH: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. WA: conceptualization, methodology, data acquisition, data analysis, writing—review and editing.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.