Original quantitative research – Strength-training and balance activities in Canada: historical trends and current prevalence

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: May 2023

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Stephanie A. Prince, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2; Justin J. Lang, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 3; Rachel C. Colley, PhDAuthor reference footnote 4; Lora M. Giangregorio, PhDAuthor reference footnote 5Author reference footnote 6Author reference footnote 7; Rasha El-Kotob, PhDAuthor reference footnote 5Author reference footnote 7; Gregory P. Butler, MScAuthor reference footnote 1; Karen C. Roberts, MScAuthor reference footnote 1

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.5.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Stephanie A. Prince, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 613-324-7860; Email: stephanie.prince.ware@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Suggested citation

Prince SA, Lang JJ, Colley RC, Giangregorio LM, El-Kotob R, Butler GP, Roberts KC. Strength-training and balance activities in Canada: historical trends and current prevalence. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(5):209-21. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.5.01

Abstract

Introduction: Muscle-strengthening and balance activities are associated with the prevention of illness and injury. Age-specific Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines include recommendations for muscle/bone-strengthening and balance activities. From 2000–2014, the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) included a module that assessed frequency in 22 physical activities. In 2020, a healthy living rapid response module (HLV-RR) on the CCHS asked new questions on the frequency of muscle/bone-strengthening and balance activities. The objectives of the study were to (1) estimate and characterize adherence to meeting the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations; (2) examine associations between muscle/bone-strengthening and balance activities with physical and mental health; and (3) examine trends (2000–2014) in adherence to recommendations.

Methods: Using data from the 2020 CCHS HLV-RR, we estimated age-specific prevalence of meeting recommendations. Multivariate logistic regressions examined associations with physical and mental health. Using data from the 2000–2014 CCHS, sex-specific temporal trends in recommendation adherence were explored using logistic regression.

Results: Youth aged 12 to 17 years (56.6%, 95% CI: 52.4–60.8) and adults aged 18 to 64 years (54.9%, 95% CI: 53.1–56.8) had significantly greater adherence to the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendation than adults aged 65 years and older (41.7%, 95% CI: 38.9–44.5). Only 16% of older adults met the balance recommendation. Meeting the recommendations was associated with better physical and mental health. The proportion of Canadians who met the recommendations increased between 2000 and 2014.

Conclusion: Approximately half of Canadians met their age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening recommendations. Reporting on the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations elevates their importance alongside the already recognized aerobic recommendation.

Keywords: muscle, physical activity, recommendations, 24H Guidelines, physical health, mental health, youth, adults, older adults, adherence

Highlights

- About half (53%) of Canadians 12 years and older meet the age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening recommendations, but only 16% of older adults meet recommendations for activities that challenge balance.

- People who met the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations reported better mental and physical health than those who did not meet these recommendations.

- Temporal trends suggest an increase in adherence to muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations from 2000 to 2014.

Introduction

The benefits of regular aerobic physical activity (PA) are well established.Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3 Aerobic PA is often the centrepiece of health promotion initiatives targeting health behaviours,Footnote 4 with adherence to this recommendation the cornerstone of PA surveillance.Footnote 5 The recently released Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (“24H Guidelines”) recommend a minimum of 60 min/d of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) for children and youth (5–17 years old) and 150 min/wk for adults (18–64 years) and older adults (≥65 years).Footnote 6 The guidelines also recommend muscle and bone strengthening for children and youth (≥3 d/wk), muscle strengthening for adults aged 18 to 65 years (≥2 d/wk) and muscle-strengthening and balance activities for adults 65 years and older (strength: ≥2 d/wk; balance: no minimum frequency).Footnote 6

The recommendations for MVPA, muscle/bone and balance activities were also part of the Canadian Physical Activity GuidelinesFootnote 7 that were released a decade earlier, in 2011. (The 24H Guidelines no longer have the requirement for 10-minute bouts of MVPA.)

Muscle-strengthening exercise refers to resistance training using free or machine weights, elastic bands or one’s own body weight.Footnote 8 This type of exercise plays a unique and independent role in preventing disease and premature mortality.Footnote 8Footnote 9 Health benefits include increased skeletal muscle mass and strength and bone mineral density, improved cardiometabolic and physical functioning, reduced musculoskeletal symptoms and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression.Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13

Muscle-strengthening exercise has often been described as the “forgotten” PA guideline.Footnote 5Footnote 14Footnote 15 A 2018 review of international efforts identified only five surveys that included direct/explicit questions about muscle strengthening.Footnote 5 There is also evidence to suggest that the combined health benefits of aerobic PA and strength-training activities is greater than those of either activity alone.Footnote 16Footnote 17

Bone-strengthening and balance-training activities are also key components of a healthy PA profile. Bone strengthening, which increases resistance to fracture, includes “movements that create impact- and muscle-loading forces on the bone” such as jumping, skipping and hopping.Footnote 3 Balance-training activities include movements that challenge postural control; these activities help resist forces that can lead to fallsFootnote 18 and maintain physical functioning.Footnote 19 Some activities provide simultaneous muscle and bone strengthening and balance training, making it difficult to define them separately. The overlap between muscle- and bone-strengthening exercises is particularly challenging to assess independently. For the purpose of this paper, we use the expression “muscle/bone strengthening” to recognize that some activities may have benefits for both.

In Canada, the Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep (PASS) Indicators provide important surveillance information on the PA levels of children, youth and adults.Footnote 20Footnote 21 The proportion of Canadians meeting PA recommendations has traditionally been reported as the proportion meeting the aerobic component of the 24H Guidelines (i.e. 60 min/d for children and youth or 150 min/wk for adults),Footnote 20 consistent with the PASS surveillance recommendations released alongside the 24H Guidelines.Footnote 22Footnote 23 Until recently, there has been a lack of national data to assess adherence to the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance components of the 24H Guidelines (and the previous Canadian PA Guidelines). As a result, the PASS Indicators do not report on the proportion of Canadians meeting the age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening or balance recommendations.

In 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada funded the development of the healthy living rapid response module (HLV-RR) in the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). The HLV-RR module includes two questions to assess muscle/bone-strengthening and balance activities and allows the reporting of current prevalence of meeting the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance components of the 24H Guidelines, as well as meeting the combined PA recommendations (MVPA + muscle/bone strengthening + balance).

The PA module (PAC) in earlier cycles of the annual CCHS (2000–2014) asked participants to self-report frequency of 22 activities over the previous 3 months. Several of the activities could be considered to be muscle/bone-strengthening and/or balance exercises. While using a list of activities to establish adherence to muscle-strengthening exercise is possible,Footnote 5 there has been no known attempt to examine the PAC in this way.

Our study objectives were to:

- estimate the proportion of Canadian youth (12–17 years), adults (18–64 years) and older adults (≥65 years) currently meeting the age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening and balance-activity recommendations of the 24H Guidelines;

- compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of those categorized as meeting the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations with those meeting the combined recommendations (MVPA + muscle/bone strengthening + balance), the aerobic PA only recommendations (MVPA) and none of the recommendations;

- examine the association between meeting combinations of the recommendations and measures of physical and mental health; and

- examine age group–specific trends in muscle/bone-strengthening and balance activities among Canadians, using the CCHS (2000–2014).

Methods

Data source

To meet objectives 1, 2 and 3, we used the HLV-RR data from the 2020 CCHS, and to meet objective 4, we used annual data from older cycles of the CCHS (2000–2014). The CCHS is an ongoing, cross-sectional survey conducted by Statistics Canada. The survey collects self-reported health information from a representative sample of the Canadian household-dwelling population aged 12 years and older living in the provinces and territories. The CCHS excludes individuals living on reserves and Crown Lands, institutionalized residents, full-time members of the Canadian forces, youth aged 12 to 17 years living in foster care and residents in certain remote regions; this is approximately 2% of the Canadian population aged 12 years and older.

The HLV-RR data were collected between January and March 2020, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who completed the HLV-RR also participated in the 2020 CCHS during the data collection period, except that the HLV-RR excluded respondents living in the three territories and proxy respondents. In total, 11 105 non-proxy respondents completed the HLV-RR. At the national level, the HLV-RR had a household-level response rate of 57.0%.Footnote 24

Study population

The study population included those who completed the strength and balance questions of the 2020 CCHS HLV-RR (N = 10 775) or the annual CCHS (N = 57 070 to N = 124 685, depending on the year) for the years 2000 to 2014. The CCHS provided estimates for 2 years combined from 2000 to 2006, and annual estimates from 2007 onwards.

Study variables

Independent variables

Table 1 shows the variables used to explore current prevalence (2020 CCHS HLV-RR) and trends (2000–2014 CCHS PACs) in age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations.

| Derived variable | Questions used | Variable derivation |

|---|---|---|

Adherence to muscle or muscle/bone-strengthening recommendations To classify PA as strength training, we used the following definition: “contracting the muscles against a resistance to ‘overload’ and bring about a training effect in the muscular system. The resistance is an external force, which can be one’s own body placed in an unusual relationship to gravity (e.g. prone back extension) or an external resistance (e.g. free weight)”.Footnote 25 In addition to strength training, many PAs involve impact that benefits and strengthens muscle and bone. Impact exercise was considered any activity with a GRF ≥1 × body weight on the lower extremitiesFootnote 26Footnote 27 including low-impact exercise (GRF 1.1–1.5 × body weight), e.g. rollerblading and skateboarding; moderate impact exercise (GRF 1.51–3.10 × body weight), e.g. jogging, soccer and baseball; and high impact exercise (GRF ≥3.11 × body weight), e.g. jumping rope, ballet, volleyball. |

||

| Current prevalence (HLV-RR 2020) | In the past 7 days, on how many days did you do activities that increase bone or muscle strength? Examples of muscle/bone-strengthening activities included with the question: lifting weights; carrying heavy loads; shovelling [snow]; doing sit-ups; or running, jumping or doing sports that involve a quick change in direction. |

Youth (12–17 years) muscle/bone strengthening: ≥3 days Adults (18–64 years) muscle strengthening: ≥2 days Older adults (≥65 years): muscle strengthening: ≥3 days |

| Historical trends (CCHS 2000–2014) |

The PAC asked respondents to self-report the frequency of participating in 22 specific activities over the previous 3 months. It was hypothesized that impact, weight training or both combined are important for muscle/bone strengthening. The strategy was to look at weight training alone and then combined with moderate-to-high impact activities. A sensitivity analysis led to understanding how adding low-impact activities affects the actual proportion of Canadians meeting the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendation. Muscle/bone-strengthening activities were examined as strength training (i.e. weight training); moderate-to-high impact activities (i.e. jogging and running, tennis, volleyball, basketball, soccer) + weight training; and low-impact activities (i.e. walking for exercise, gardening or yard work, popular or social dance, ice hockey, ice skating, in-line skating or rollerblading, golfing, exercise class or aerobics, downhill skiing or snowboarding, baseball or softball) + moderate-to-high impact activities + weight training. |

The total 3-month frequency of each activity was divided by 12 to generate an average weekly frequency (assumed 4 weeks/month). Youth (12–17 years) muscle/bone-strengthening adherence: ≥3 days Adults (18–64 years) muscle-strengthening adherence: ≥2 days Older adults (≥65 years) muscle-strengthening adherence: ≥3 days |

Adherence to balance recommendation To classify the balance activities, we applied the following definition from the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE) Taxonomy: “…involv[ing] the efficient transfer of body weight from one part of the body to another or challenges specific aspects of the balance system (e.g. vestibular systems). Balance retraining activities range from re-education of basic functional movement patterns to a wide variety of dynamic activities that target more sophisticated aspects of balance”.Footnote 25 Examples include tai chi, static balance exercise (e.g. standing on one foot), dynamic balance exercise (e.g. tandem walking) or PAs with a reduced base of support or moving to the limits of stability (e.g. downhill skiing, golfing). |

||

| Current prevalence (HLV-RR 2020) |

In the past 7 days, on how many days did you do any activities that improve balance? Examples of activities included yoga, tai chi, dance, tennis, volleyball and balance training. |

Older adults (≥65 years): balance activities ≥2 days and 7 days. The 24H Guidelines for Adults 65 Years and Older do not explicitly state a minimum weekly frequency for balance activities. We explored adherence to twice-weekly and daily frequencies because clinical trials generally measure twice-weekly balance activities, but documentation supporting the 24H Guidelines suggests that older adults should engage daily in activities that routinely challenge balance.Footnote 28 |

| Historical trends (CCHS 2000–2014) |

The PAC module asked respondents to self-report the frequency of 22 specific activities over the previous 3 months. Balance activities were examined as: (1) sports-related activities that may challenge balance (i.e. popular or social dance, ice hockey, ice skating, in-line skating and rollerblading, jogging or running, golfing, downhill skiing or snowboarding, bowling, baseball or softball, tennis, volleyball, basketball, soccer); (2) sports or exercise or leisure activities that may challenge balance (i.e. sports-related + walking for exercise, gardening or yard work, bicycling, home exercises, exercise class or aerobics, weight training). |

The total 3-month frequency of each activity was divided by 12 to generate an average weekly frequency (assumed 4 weeks/month). Older adults (≥65 years): balance activities ≥2 days |

Dependent variables

Population characteristics

Characteristics examined included age (12–17, 18–64, ≥65 years); sex (male, female); immigration status (landed immigrant, non-immigrant); cultural/racial background (White, non-White; the category “White” does not include Indigenous people); household education (secondary or less, postsecondary graduate); distribution of household income quintile (relative measure of household income to household income of all other respondents); and marital status (married/common law, single [widowed/divorced/separated/never married]). Disaggregations for gender were calculated, but too few respondents identified as gender diverse to generate stable results.

Health behaviours

Self-reported health behaviours included smoking status; meeting the leisure screen time recommendation (≤2 hours per day for youth; ≤3 hours per day for adults); and meeting the sleep recommendations (youth 12–13 years, 9–11.99 hours/night; youth 14–17 years: 8–10.99 hours/night; adults 18–64 years: 7–9.99 hours/night; adults ≥65 years: 7–8.99 hours/night).

Physical and mental health

Measures of health included self-reported general health (“excellent/very good” vs. “good/fair/poor”); self-reported mental health (“excellent/very good” vs. “good/fair/poor”); self-reported body mass index (BMI; under/normal weight vs. overweight/obesity; youth: based on age- and sex-specific BMI cut-points as defined by the World Health Organization; adults: based on Health Canada and World Health Organization body weight classification systems, corrected using the methods of Connor Gorber et al.Footnote 29); and multimorbidity (self-reported diagnoses of ≥2 of asthma, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, chronic respiratory disease [in those ≥35 years] and mood disorders).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide v.7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US). For objective 1, we used proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) conducted with proc surveyfreq to describe adherence to the age-specific aerobic PA only (MVPA), muscle/bone strengthening only, balance only and combined (muscle/bone strengthening/balance + aerobic PA) recommendations, overall and by sex and age group (youth, adults and older adults).

For objective 2, we also present characteristics of those meeting the recommendations using proportions or means and 95% CIs. Comparisons between those meeting and those not meeting the various combinations of recommendations were assessed using independent sample t tests (proc surveyreg) for continuous outcomes or chi-square (proc surveyfreq) for categorical outcomes.

For objective 3, we assessed the association between meeting the recommendations or combinations of the recommendations and measures of physical and mental health using age-specific multivariate logistic regression models controlling for sex, household income and smoking status conducted using proc surveylogistic.

For objective 4, we present the historical prevalence (2000–2014) of those meeting the age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening/balance recommendations by age and sex using weighted proportions and 95% CIs (proc surveyfreq). The prevalence of meeting each recommendation was graphed against time in years. Age- and sex-specific temporal trends in prevalence were explored using logistic regression with time (CCHS cycle) as a continuous variable to assess if time was a significant predictor of meeting the recommendations conducted using proc surveylogistic.

All analyses were weighted using appropriate cycle survey weights. To account for survey design effects, 95% CIs were estimated using the bootstrap balanced repeated replication technique with 500 replicate weights for the 2000–2014 CCHS, and 1000 replicate weights for the 2020 CCHS. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Current adherence to recommendations (Objective 1)

In 2020, youth (56.6%, 95% CI: 52.4–60.8%) and adults aged 18–64 years (54.9%, 95% CI: 53.1–56.8%) had significantly greater adherence to the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendation than older adults aged 65 years and older (41.7%, 95% CI: 38.9–44.5%).

Characteristics of adherence to recommendations (Objective 2)

Across all age groups, males were significantly more likely than females to meet the muscle-strengthening recommendation (see Table 2). Males aged 12–17 years and 18–64 years were also more likely to meet the combined PA recommendations than their female counterparts.

| Recommendation met | Youth (12–17 years) | Adults (18–64 years) | Older adults (≥65 years) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||||||||||

| % | LCL | UCL | % | LCL | UCL | % | LCL | UCL | % | LCL | UCL | % | LCL | UCL | % | LCL | UCL | |

| Aerobic | 65.8 | 59.3 | 72.3 | 49.3Footnote * | 43.0 | 55.7 | 62.3 | 59.2 | 65.3 | 53.9Footnote * | 51.1 | 56.6 | 46.6 | 42.3 | 50.9 | 35.7Footnote * | 32.4 | 38.9 |

| Muscle and bone strength | 61.8 | 56.0 | 67.6 | 51.2Footnote * | 44.9 | 57.4 | 61.2 | 53.4 | 64.1 | 48.7Footnote * | 46.0 | 51.4 | 49.3 | 44.9 | 53.7 | 35.4Footnote * | 32.1 | 38.6 |

| Balance ≥2 d/wk | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13.8 | 11.1 | 16.6 | 18.1Footnote * | 15.2 | 21.1 |

| Balance 7 d/wk | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5.8Footnote E | 3.8 | 7.9 | 4.5Footnote E | 3.0 | 6.0 |

| Combined muscle/bone + aerobic (+ balance in older adults) | 50.3 | 43.2 | 57.3 | 32.9Footnote * | 26.9 | 39.0 | 46.6 | 43.6 | 49.9 | 34.9Footnote * | 32.3 | 37.5 | 8.6 | 6.5 | 10.8 | 9.2 | 6.8 | 11.5 |

Because very few older adults met the 7-day balance recommendation compared to the 2-day requirement, for all further analyses we applied the twice-weekly requirement. Older (≥65 years) females were more likely than older males to meet the balance recommendation.

The proportion of Canadians meeting the strength recommendation was lower among landed immigrants, non-White ethnicities, those with a lower household education and those with lower household income (see Table 3). The same differences were observed for the combined PA recommendations except for no difference by cultural/racial background. Among older adults, adherence to the balance recommendation (≥2 times per week) was significantly lower among those with lower household education than those with higher household education.

| Characteristics | Muscle/bone strength recommendation (total sample) | Balance recommendation (older adults) | Combined muscle/bone + aerobic (+ balance in older adults) (total sample) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %Footnote a | LCL | UCL | %Footnote a | LCL | UCL | %Footnote a | LCL | UCL | |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Age, years | |||||||||

| 12–17 | 56.6Footnote * | 52.4 | 60.8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 41.7Footnote * | 36.9 | 46.4 |

| 18–64 | 54.9Footnote * | 53.1 | 56.8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 40.7Footnote * | 38.8 | 42.7 |

| ≥65 | 41.7Footnote * | 38.9 | 44.5 | 16.2 | 14.1 | 18.3 | 8.9Footnote * | 7.3 | 10.5 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 59.1Footnote * | 56.8 | 61.5 | 13.8Footnote * | 11.1 | 16.6 | 40.0Footnote * | 37.7 | 42.4 |

| Female | 46.1Footnote * | 44.0 | 48.3 | 18.1Footnote * | 15.2 | 21.1 | 29.5Footnote * | 27.4 | 31.5 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married or common law | 52.8 | 50.6 | 55.0 | 16.4 | 13.6 | 19.2 | 33.7 | 31.6 | 35.7 |

| SingleFootnote b | 52.2 | 49.7 | 54.6 | 15.9 | 13.0 | 18.8 | 36.0 | 33.7 | 38.4 |

| Immigration status | |||||||||

| Landed immigrant | 45.4Footnote * | 41.4 | 49.5 | 18.0 | 12.8 | 23.2 | 26.3Footnote * | 22.7 | 30.0 |

| Non-immigrant | 54.9Footnote * | 53.1 | 56.6 | 15.8 | 13.5 | 18.1 | 37.3Footnote * | 35.6 | 38.9 |

| Cultural/racial background | |||||||||

| Non-White | 47.5Footnote * | 43.2 | 51.7 | 18.7Footnote E | 10.3 | 27.1 | 31.4 | 26.9 | 36.0 |

| White | 53.8Footnote * | 52.1 | 55.4 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 17.9 | 35.1 | 33.4 | 36.9 |

| Highest household education level | |||||||||

| Secondary or less | 42.4Footnote * | 38.9 | 45.8 | 12.2Footnote * | 8.9 | 15.6 | 20.6Footnote * | 17.8 | 23.4 |

| Postsecondary graduate | 54.6Footnote * | 52.8 | 56.3 | 18.0Footnote * | 15.4 | 20.6 | 37.7Footnote * | 35.9 | 39.5 |

| Distribution of household income quintile | |||||||||

| Q1 (Lowest) | 41.3Footnote * | 38.2 | 44.4 | 14.4 | 10.7 | 18.1 | 25.3Footnote * | 22.4 | 28.3 |

| Q2 | 51.1Footnote * | 47.6 | 54.7 | 14.6 | 10.9 | 18.3 | 30.8Footnote * | 27.4 | 34.2 |

| Q3 | 52.0Footnote * | 48.0 | 56.1 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 18.5 | 34.0Footnote * | 30.1 | 37.9 |

| Q4 | 59.9Footnote * | 56.1 | 63.7 | 22.8 | 17.2 | 28.4 | 41.0Footnote * | 36.8 | 45.1 |

| Q5 (Highest) | 58.6Footnote * | 54.9 | 62.3 | 17.9 | 12.5 | 23.4 | 42.1Footnote * | 38.6 | 45.7 |

| Health behaviours | |||||||||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Smoker | 52.4 | 47.8 | 56.9 | 8.0Footnote EFootnote * | 3.3 | 12.7 | 33.0 | 28.6 | 37.3 |

| Non-smoker | 52.6 | 50.8 | 54.3 | 17.1Footnote * | 14.8 | 19.5 | 34.9 | 33.3 | 36.6 |

| Leisure screen time recommendationFootnote c | |||||||||

| Met recommendation | 56.3Footnote * | 54.3 | 58.2 | 18.2Footnote * | 15.4 | 21.0 | 37.6Footnote * | 35.6 | 39.7 |

| Did not meet recommendation | 46.0Footnote * | 43.4 | 48.5 | 13.6Footnote * | 10.6 | 16.7 | 29.4Footnote * | 26.9 | 31.9 |

| Sleep time recommendationFootnote d | |||||||||

| Met recommendation | 55.4Footnote * | 53.5 | 57.4 | 18.8Footnote * | 15.4 | 22.1 | 38.2Footnote * | 36.2 | 40.2 |

| Did not meet recommendation | 46.9Footnote * | 43.8 | 50.1 | 12.7Footnote * | 10.2 | 15.2 | 27.2Footnote * | 24.2 | 30.1 |

| MVPAFootnote e | |||||||||

| Met recommendation | 68.2Footnote * | 66.3 | 70.2 | 28.6Footnote * | 26.4 | 30.9 | 100Footnote * | N/A | N/A |

| Did not meet recommendation | 33.2Footnote * | 30.9 | 35.4 | 9.6Footnote * | 8.3 | 10.9 | 0Footnote * | N/A | N/A |

Health behaviours and adherence to recommendations (Objective 2)

Among youth and adults, there was no statistically significant difference between smokers and non-smokers for meeting the muscle/bone-strengthening or combined PA recommendations (see Table 3). Those who met the screen time, sleep and aerobic PA recommendations were more likely to meet muscle/bone-strengthening combined recommendations than those who did not.

Among older adults, statistically significant differences were observed across all recommendations with non-smokers and those who met the screen, sleep and aerobic PA recommendations more likely to meet the balance recommendation.

Association between recommendation adherence and health (Objective 3)

Meeting the age-specific muscle/bone-strengthening, balance and combined PA recommendations was associated with a significantly reduced likelihood of multimorbidity and increased likelihood of excellent and very good perceived mental and general health (see Table 4). In addition, among older adults, meeting the balance recommendations was associated with a reduced likelihood of overweight and obesity.

| Health outcomes | Muscle/bone strength recommendation (total sample) | Balance recommendation (older adults) | Combined muscle/bone + aerobic (+ balance in older adults) (total sample) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %Footnote a | LCL | UCL | aORFootnote b | LCL | UCL | %Footnote a | LCL | UCL | aORFootnote c | LCL | UCL | %Footnote a | LCL | UCL | aORFootnote b | LCL | UCL | |

| BMI categoryFootnote d | ||||||||||||||||||

| Overweight and obese | 51.9 | 49.7 | 54.1 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 1.07 | 13.8Footnote * | 11.5 | 16.0 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.74 | 33.8 | 31.6 | 35.9 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 1.17 |

| Under and normal weight | 54.5 | 51.7 | 57.4 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 22.0Footnote * | 17.9 | 26.2 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 37.2 | 34.2 | 40.1 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A |

| Multimorbidity statusFootnote e | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2+ chronic conditions | 37.4Footnote * | 33.8 | 41.1 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.82 | 9.9Footnote * | 7.5 | 12.2 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 18.9Footnote * | 15.8 | 22.0 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 1.00 |

| <2 chronic conditions | 54.5Footnote * | 52.8 | 56.3 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 18.7Footnote * | 16.0 | 21.5 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 36.8Footnote * | 35.0 | 38.5 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A |

| Self-reported mental health | ||||||||||||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 55.5Footnote * | 53.6 | 57.4 | 1.36 | 1.18 | 1.56 | 17.5Footnote * | 14.9 | 20.2 | 1.43 | 1.01 | 2.02 | 36.7Footnote * | 34.9 | 38.6 | 1.32 | 1.12 | 1.57 |

| Good/fair/poor | 46.7Footnote * | 43.9 | 49.4 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 12.6Footnote * | 9.7 | 15.6 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 30.5Footnote * | 27.6 | 33.4 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A |

| Self-reported general health | ||||||||||||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 58.3Footnote * | 56.2 | 60.4 | 1.65 | 1.44 | 1.90 | 20.5Footnote * | 17.1 | 23.9 | 1.80 | 1.33 | 2.44 | 41.2Footnote * | 39.1 | 43.2 | 1.84 | 1.55 | 2.18 |

| Good/fair/poor | 43.2Footnote * | 40.7 | 45.6 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 11.9Footnote * | 9.7 | 14.1 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 24.2Footnote * | 21.7 | 26.7 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A |

Trends in adherence to recommendations (Objective 4)

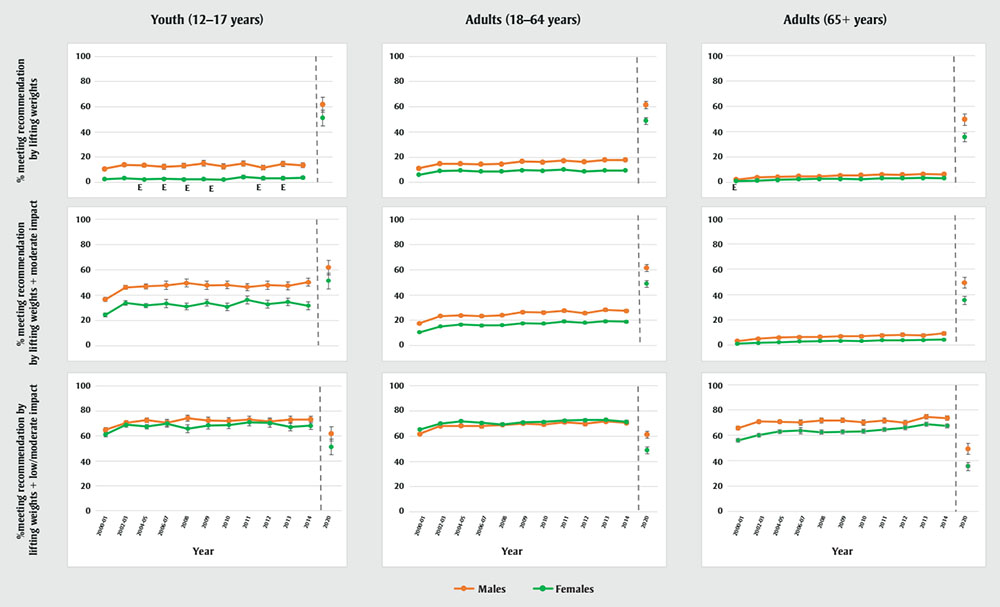

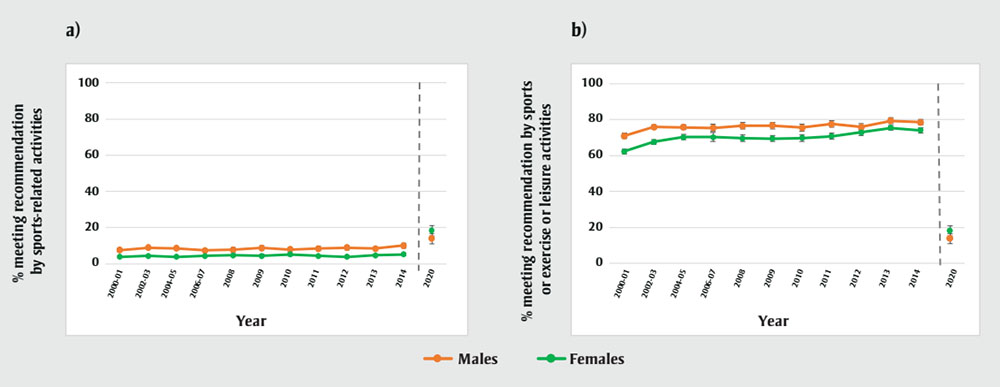

Figures 1 and 2 show age- and sex-specific trends in meeting the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations, respectively. The difference between Figures 2a and 2b are largely due to the addition of leisure activities; these can—but do not always—challenge balance. Walking, gardening/yard work and cycling are three of the most popular leisure activities, with 71% of older adults reporting walking, 49% reporting gardening/yard work and 24% reporting cycling in 2014. Removal of these activities to assess balance resulted in a decline in adherence to the balance recommendation from 76.1% to 46.9% (data not shown).

Figure 1 - Text description

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 10.74854 | 9.658143351 | 11.83894574 |

| Females | 2.596307 | 2.002758078 | 3.189855675 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 13.87895 | 12.45975907 | 15.29813965 |

| Females | 3.363153 | 2.711093925 | 4.015211796 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 13.66253 | 12.33481502 | 14.99025047 |

| Females | 2.29997 | 1.811258552 | 2.788680754 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 12.36218 | 10.43543968 | 14.28891401 |

| Females | 2.780633Footnote E | 1.787663926 | 3.773601522 | |

| 2008 | Males | 13.20677 | 11.31517245 | 15.09837546 |

| Females | 2.445849Footnote E | 1.532331745 | 3.35936545 | |

| 2009 | Males | 15.10212 | 12.88887426 | 17.31536823 |

| Females | 2.514115Footnote E | 1.655699765 | 3.372529653 | |

| 2010 | Males | 12.61818 | 10.59940939 | 14.63695574 |

| Females | 2.135786Footnote E | 1.350680215 | 2.92089129 | |

| 2011 | Males | 14.94864 | 12.84289062 | 17.05439196 |

| Females | 4.307524 | 3.017766352 | 5.597281041 | |

| 2012 | Males | 11.74511 | 9.819911762 | 13.6703014 |

| Females | 3.349675Footnote E | 1.951407667 | 4.747943002 | |

| 2013 | Males | 14.64639 | 12.45503648 | 16.83774371 |

| Females | 3.334147Footnote E | 1.996497574 | 4.671796349 | |

| 2014 | Males | 13.68332 | 11.74518314 | 15.62146139 |

| Females | 3.722934 | 2.544518804 | 4.901349091 | |

| 2020 | Males | 61.78177 | 55.97882271 | 67.5847267 |

| Females | 51.16955 | 44.89769028 | 57.44141399 | |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 11.32106 | 10.81814 | 11.82399 |

| Females | 6.186992 | 5.864525 | 6.50946 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 14.78706 | 14.23323 | 15.34088 |

| Females | 9.132783 | 8.689821 | 9.575744 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 14.79677 | 14.15049 | 15.44305 |

| Females | 9.518243 | 9.010415 | 10.02607 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 14.37782 | 13.57721 | 15.17842 |

| Females | 8.677797 | 8.046111 | 9.309483 | |

| 2008 | Males | 14.60139 | 13.83956 | 15.36321 |

| Females | 8.828437 | 8.199563 | 9.457312 | |

| 2009 | Males | 16.64767 | 15.70382 | 17.59153 |

| Females | 9.707218 | 9.022684 | 10.39175 | |

| 2010 | Males | 16.11195 | 15.17849 | 17.04542 |

| Females | 9.283709 | 8.619773 | 9.947645 | |

| 2011 | Males | 17.3763 | 16.33291 | 18.4197 |

| Females | 10.28864 | 9.539301 | 11.03797 | |

| 2012 | Males | 16.41054 | 15.3798 | 17.44127 |

| Females | 8.785843 | 8.040066 | 9.531621 | |

| 2013 | Males | 17.82385 | 16.75468 | 18.89302 |

| Females | 9.431802 | 8.741984 | 10.12162 | |

| 2014 | Males | 17.86699 | 16.88071 | 18.85326 |

| Females | 9.605791 | 8.864763 | 10.34682 | |

| 2020 | Males | 61.23258 | 58.39845 | 64.06672 |

| Females | 48.72198 | 46.00388 | 51.44008 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 2.069746 | 1.666703 | 2.472788 |

| Females | 0.829796Footnote E | 0.54186 | 1.117732 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 3.759292 | 3.136386 | 4.382199 |

| Females | 1.264979 | 1.025878 | 1.504079 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 4.039303 | 3.379674 | 4.698932 |

| Females | 1.884873 | 1.523563 | 2.246183 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 4.671785 | 3.902236 | 5.441335 |

| Females | 2.333324 | 1.793253 | 2.873394 | |

| 2008 | Males | 4.477515 | 3.642319 | 5.312711 |

| Females | 2.585797 | 1.976135 | 3.195459 | |

| 2009 | Males | 5.242921 | 4.309197 | 6.176645 |

| Females | 2.638782 | 2.072293 | 3.205271 | |

| 2010 | Males | 5.481843 | 4.401126 | 6.562561 |

| Females | 2.457883 | 1.972021 | 2.943744 | |

| 2011 | Males | 5.943533 | 4.767426 | 7.11964 |

| Females | 3.143817 | 2.514177 | 3.773456 | |

| 2012 | Males | 5.743785 | 4.669492 | 6.818078 |

| Females | 3.20853 | 2.611311 | 3.805749 | |

| 2013 | Males | 6.384513 | 5.384511 | 7.384515 |

| Females | 3.350926 | 2.753229 | 3.948624 | |

| 2014 | Males | 6.085631 | 5.18021 | 6.991051 |

| Females | 3.172021 | 2.663664 | 3.680379 | |

| 2020 | Males | 49.30484 | 44.93607 | 53.67362 |

| Females | 35.35068 | 32.08791 | 38.61345 | |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 36.61708 | 34.89752 | 38.33664 |

| Females | 24.40898 | 22.82668 | 25.99128 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 46.13715 | 44.42489 | 47.84941 |

| Females | 33.80704 | 32.04977 | 35.56432 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 46.88926 | 44.98115 | 48.79737 |

| Females | 31.74044 | 29.97998 | 33.50089 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 47.71262 | 44.50159 | 50.92365 |

| Females | 33.30038 | 30.06888 | 36.53189 | |

| 2008 | Males | 49.5751 | 46.60419 | 52.54601 |

| Females | 30.99351 | 28.36917 | 33.61786 | |

| 2009 | Males | 47.78705 | 44.62693 | 50.94717 |

| Females | 34.00423 | 31.24808 | 36.76039 | |

| 2010 | Males | 48.07891 | 45.18399 | 50.97384 |

| Females | 30.85795 | 27.89548 | 33.82041 | |

| 2011 | Males | 46.35302 | 43.47261 | 49.23344 |

| Females | 36.23855 | 33.12962 | 39.34748 | |

| 2012 | Males | 47.80503 | 44.50077 | 51.1093 |

| Females | 32.76515 | 29.69335 | 35.83695 | |

| 2013 | Males | 47.34908 | 44.23436 | 50.4638 |

| Females | 34.61367 | 31.66496 | 37.56238 | |

| 2014 | Males | 50.16394 | 47.12845 | 53.19943 |

| Females | 31.58395 | 28.51257 | 34.65533 | |

| 2020 | Males | 61.78177 | 55.97882 | 67.58473 |

| Females | 51.16955 | 44.89769 | 57.44141 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 17.67316 | 17.08029 | 18.26604 |

| Females | 10.49069 | 10.08478 | 10.8966 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 23.43494 | 22.78145 | 24.08844 |

| Females | 15.13441 | 14.5992 | 15.66962 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 23.77116 | 22.926 | 24.61632 |

| Females | 16.62756 | 15.85293 | 17.40219 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 23.32551 | 22.25685 | 24.39417 |

| Females | 15.94077 | 15.04342 | 16.83811 | |

| 2008 | Males | 23.9538 | 23.00933 | 24.89828 |

| Females | 16.22222 | 15.44606 | 16.99838 | |

| 2009 | Males | 26.43375 | 25.33692 | 27.53059 |

| Females | 17.54882 | 16.71742 | 18.38021 | |

| 2010 | Males | 26.17849 | 25.0894 | 27.26759 |

| Females | 17.43046 | 16.55488 | 18.30604 | |

| 2011 | Males | 27.55326 | 26.34407 | 28.76245 |

| Females | 19.1255 | 18.1918 | 20.0592 | |

| 2012 | Males | 25.6728 | 24.49691 | 26.84868 |

| Females | 18.02958 | 17.08631 | 18.97286 | |

| 2013 | Males | 28.25071 | 27.04697 | 29.45445 |

| Females | 19.25333 | 18.3349 | 20.17175 | |

| 2014 | Males | 27.52429 | 26.36445 | 28.68413 |

| Females | 18.97385 | 18.00708 | 19.94062 | |

| 2020 | Males | 61.23258 | 58.39845 | 64.06672 |

| Females | 48.72198 | 46.00388 | 51.44008 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 3.332451 | 2.751335 | 3.913567 |

| Females | 1.220842 | 0.898975 | 1.542709 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 5.093026 | 4.365199 | 5.820854 |

| Females | 1.844811 | 1.536401 | 2.153221 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 5.991236 | 5.217593 | 6.76488 |

| Females | 2.3027 | 1.897707 | 2.707694 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 6.382709 | 5.382906 | 7.382512 |

| Females | 2.957962 | 2.260896 | 3.655028 | |

| 2008 | Males | 6.573284 | 5.435002 | 7.711565 |

| Females | 3.291487 | 2.589688 | 3.993286 | |

| 2009 | Males | 6.99407 | 5.951793 | 8.036347 |

| Females | 3.429575 | 2.802393 | 4.056757 | |

| 2010 | Males | 6.983925 | 5.782162 | 8.185688 |

| Females | 3.32122 | 2.636971 | 4.005469 | |

| 2011 | Males | 7.698683 | 6.429034 | 8.968332 |

| Females | 3.884517 | 3.210272 | 4.558763 | |

| 2012 | Males | 8.184136 | 6.798596 | 9.569676 |

| Females | 3.879207 | 3.247466 | 4.510948 | |

| 2013 | Males | 7.721702 | 6.674637 | 8.768767 |

| Females | 4.091259 | 3.446125 | 4.736392 | |

| 2014 | Males | 9.338352 | 8.012573 | 10.66413 |

| Females | 4.391573 | 3.706441 | 5.076705 | |

| 2020 | Males | 49.30484 | 44.93607 | 53.67362 |

| Females | 35.35068 | 32.08791 | 38.61345 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 64.94651 | 63.06604 | 66.82697 |

| Females | 61.30891 | 59.44474 | 63.17308 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 70.59676 | 69.04116 | 72.15235 |

| Females | 69.10061 | 67.26475 | 70.93648 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 72.65523 | 70.88344 | 74.42702 |

| Females | 67.6134 | 65.76172 | 69.46508 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 70.59213 | 67.84376 | 73.3405 |

| Females | 69.99683 | 67.21115 | 72.78251 | |

| 2008 | Males | 74.2686 | 71.80117 | 76.73603 |

| Females | 65.86882 | 62.84063 | 68.89702 | |

| 2009 | Males | 72.42177 | 69.56558 | 75.27796 |

| Females | 68.45306 | 65.63099 | 71.27514 | |

| 2010 | Males | 72.14187 | 69.47357 | 74.81017 |

| Females | 68.78342 | 66.03888 | 71.52797 | |

| 2011 | Males | 73.01297 | 70.21597 | 75.80998 |

| Females | 70.99095 | 68.28889 | 73.69301 | |

| 2012 | Males | 71.77571 | 68.95201 | 74.5994 |

| Females | 70.39815 | 67.11127 | 73.68502 | |

| 2013 | Males | 73.06579 | 70.36549 | 75.76608 |

| Females | 67.18681 | 64.106 | 70.26761 | |

| 2014 | Males | 73.3168 | 70.54801 | 76.08559 |

| Females | 68.29786 | 65.24078 | 71.35494 | |

| 2020 | Males | 61.78177 | 55.97882 | 67.58473 |

| Females | 51.16955 | 44.89769 | 57.44141 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 61.79226 | 61.01996 | 62.56457 |

| Females | 65.34994 | 64.67741 | 66.02247 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 68.05041 | 67.25205 | 68.84876 |

| Females | 70.12242 | 69.32812 | 70.91671 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 68.31288 | 67.17845 | 69.44731 |

| Females | 71.97421 | 70.89123 | 73.0572 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 68.0141 | 66.62862 | 69.39957 |

| Females | 70.54401 | 69.51371 | 71.57431 | |

| 2008 | Males | 69.05573 | 67.90125 | 70.21022 |

| Females | 69.41958 | 68.25428 | 70.58488 | |

| 2009 | Males | 70.12362 | 68.97591 | 71.27134 |

| Females | 70.99268 | 69.88074 | 72.10462 | |

| 2010 | Males | 69.32637 | 67.99563 | 70.6571 |

| Females | 71.31274 | 70.13042 | 72.49506 | |

| 2011 | Males | 71.14256 | 69.86135 | 72.42377 |

| Females | 72.35521 | 71.22139 | 73.48902 | |

| 2012 | Males | 69.83532 | 68.49296 | 71.17768 |

| Females | 72.8163 | 71.74575 | 73.88686 | |

| 2013 | Males | 71.66757 | 70.36373 | 72.9714 |

| Females | 72.94384 | 71.65937 | 74.22831 | |

| 2014 | Males | 70.66234 | 69.38025 | 71.94444 |

| Females | 71.41359 | 70.16909 | 72.65809 | |

| 2020 | Males | 61.23258 | 58.39845 | 64.06672 |

| Females | 48.72198 | 46.00388 | 51.44008 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 65.72683 | 64.19546 | 67.25819 |

| Females | 56.07955 | 54.7606 | 57.3985 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 70.93138 | 69.5656 | 72.29716 |

| Females | 60.09043 | 58.7644 | 61.41647 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 70.74298 | 69.28986 | 72.1961 |

| Females | 63.10098 | 61.672 | 64.52995 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 70.20537 | 68.11109 | 72.29965 |

| Females | 63.73272 | 61.31009 | 66.15535 | |

| 2008 | Males | 71.80598 | 69.8967 | 73.71526 |

| Females | 62.49795 | 60.67592 | 64.31998 | |

| 2009 | Males | 71.78762 | 69.94077 | 73.63448 |

| Females | 62.86526 | 61.23496 | 64.49556 | |

| 2010 | Males | 70.12057 | 68.03036 | 72.21078 |

| Females | 63.26067 | 61.53543 | 64.98592 | |

| 2011 | Males | 71.67726 | 69.66856 | 73.68596 |

| Females | 64.56508 | 62.79714 | 66.33301 | |

| 2012 | Males | 69.8261 | 67.8548 | 71.79741 |

| Females | 66.05275 | 64.40187 | 67.70363 | |

| 2013 | Males | 74.70816 | 72.90159 | 76.51472 |

| Females | 68.80525 | 67.26541 | 70.34508 | |

| 2014 | Males | 73.61263 | 71.91619 | 75.30908 |

| Females | 67.45674 | 65.97362 | 68.93986 | |

| 2020 | Males | 49.30484 | 44.93607 | 53.67362 |

| Females | 35.35068 | 32.08791 | 38.61345 |

Figure 2 - Text description

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 7.623666 | 6.710987 | 8.536345 |

| Females | 3.916308 | 3.39889 | 4.433726 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 8.833507 | 7.978919 | 9.688095 |

| Females | 4.328802 | 3.719742 | 4.937861 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 8.505164 | 7.713251 | 9.297078 |

| Females | 3.851828 | 3.386737 | 4.316919 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 7.346709 | 6.220483 | 8.472935 |

| Females | 4.356598 | 3.628703 | 5.084492 | |

| 2008 | Males | 7.795129 | 6.553429 | 9.036829 |

| Females | 4.696012 | 3.892101 | 5.499922 | |

| 2009 | Males | 8.743208 | 7.577226 | 9.909189 |

| Females | 4.368939 | 3.622158 | 5.11572 | |

| 2010 | Males | 7.91528 | 6.733278 | 9.097282 |

| Females | 5.126436 | 4.28078 | 5.972093 | |

| 2011 | Males | 8.44725 | 7.3696 | 9.5249 |

| Females | 4.300374 | 3.670194 | 4.930554 | |

| 2012 | Males | 8.944861 | 7.750878 | 10.13884 |

| Females | 3.834343 | 3.214461 | 4.454225 | |

| 2013 | Males | 8.32129 | 7.27144 | 9.37114 |

| Females | 4.612948 | 3.930549 | 5.295347 | |

| 2014 | Males | 10.00534 | 8.631371 | 11.37931 |

| Females | 5.219159 | 4.513431 | 5.924888 | |

| 2020 | Males | 13.84019 | 11.07065 | 16.60973 |

| Females | 18.14565 | 15.23895 | 21.05234 |

| Year | Sex | % | 95% Lower Confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Males | 70.86536 | 69.39408 | 72.33663 |

| Females | 62.29354 | 61.00647 | 63.58061 | |

| 2002-03 | Males | 75.90169 | 74.64382 | 77.15957 |

| Females | 67.57667 | 66.30729 | 68.84605 | |

| 2004-05 | Males | 75.6806 | 74.3014 | 77.0598 |

| Females | 70.27939 | 68.90917 | 71.64961 | |

| 2006-07 | Males | 75.33169 | 73.30118 | 77.36219 |

| Females | 70.2749 | 67.91283 | 72.63697 | |

| 2008 | Males | 76.5777 | 74.8023 | 78.3531 |

| Females | 69.56805 | 67.82784 | 71.30826 | |

| 2009 | Males | 76.66226 | 74.88542 | 78.4391 |

| Females | 69.48032 | 67.9123 | 71.04833 | |

| 2010 | Males | 75.54502 | 73.5925 | 77.49753 |

| Females | 69.69547 | 67.98076 | 71.41017 | |

| 2011 | Males | 77.46299 | 75.65019 | 79.27579 |

| Females | 70.7867 | 69.09526 | 72.47814 | |

| 2012 | Males | 75.77338 | 73.91014 | 77.63663 |

| Females | 72.81493 | 71.21675 | 74.41311 | |

| 2013 | Males | 79.28882 | 77.65187 | 80.92576 |

| Females | 75.39324 | 73.98561 | 76.80087 | |

| 2014 | Males | 78.55255 | 76.92971 | 80.17539 |

| Females | 74.0049 | 72.58331 | 75.42649 | |

| 2020 | Males | 13.84019 | 11.07065 | 16.60973 |

| Females | 18.14565 | 15.23895 | 21.05234 |

At all ages, the odds of adhering to the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendations, regardless of the activities (i.e. weight lifting, moderate-to-high or low-to-high impact), increased over time, with the greatest increase observed among older adults. Among older adults, the odds of adhering to the balance recommendation using either sports or combined sports/exercise/leisure activities also increased over time. While results indicate a small, but linear association with cycle/year, Figures 1 and 2 show cycle-by-cycle differences are not necessarily linear.

Discussion

Our findings show that approximately 57% of youth aged 12–17 years, 55% of adults aged 18–64 years, and 42% of older adults aged ≥65 years currently (in 2020) meet the muscle/bone-strengthening PA recommendations from the 24H Guidelines. In addition, 16% of older adults engage in activities that challenge balance at least twice per week. Meeting either the muscle/bone-strengthening or balance recommendations alone or in combination with sufficient MVPA was associated with better physical and mental health. Results of the time trend analysis found that in all age groups, there was a small but significant increase in the proportion of Canadians who met the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations from 2000 to 2014.

Comparisons with the literature

Very few national surveillance systems include ways to assess participation in muscle- and bone-strengthening activities and almost none assess balance activities.Footnote 5 Internationally, the prevalence of meeting the strength-training recommendation ranges from 16% to 57% among youth (≥3 times per week)Footnote 14Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34 and from 3% to 70% among adults (most report between 10–30%; ≥2 times per week).Footnote 35 Prevalence of sufficient balance training among older adults ranges from 9% to 34%.Footnote 1Footnote 4Footnote 36Footnote 37 The Canadian prevalence estimates for muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations tend towards the higher end of this range. Comparing prevalence globally should be done with caution, however, given the variation in survey questions and methods.

Other studies have also shown that females,Footnote 14Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 34Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42 older adults,Footnote 14Footnote 30Footnote 34Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43 people living at or in households with lower education,Footnote 34Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 43 people at lower income,Footnote 34Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42 some non-White ethnicities,Footnote 31 those with poorer self-rated health,Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 42 current smokersFootnote 38Footnote 42 and those with overweight or obesityFootnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42 are less likely to meet the strength-training recommendation. In addition, among older adults, sufficient balance exercise is lower with increasing age,Footnote 14 among femalesFootnote 8Footnote 35Footnote 36 and among those with lower education,Footnote 36Footnote 37 lower income,Footnote 36 poor self-rated healthFootnote 37 or obesity.Footnote 36Footnote 37

Evidence gathered in Janssen and LeBlanc’s systematic review,Footnote 44 which informed the 24H Guidelines recommendations,Footnote 3 suggests that youth that engage in high impact activities (e.g. jumping) have better bone mass accrual or bone structure. Muscle-strength training has been consistently associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality and in cardiovascular disease incidence and better physical functioning among adults.Footnote 8 Similarly, older adults’ (≥65 years) engagement in balance and functional training is associated with better physical functioning.Footnote 19

Findings from the present study confirm associations between meeting the recommendation and multimorbidity and perceived physical and mental health. The findings also suggest that meeting either recommendation alone or in combination with sufficient MVPA is associated with better physical and mental health. This supports the concept that all activity is health promoting and provides people with choice for being active. While the effect of strength or balance training on adults’ health-related quality of life is uncertain,Footnote 8Footnote 19 our results for self-reported physical health suggest a cross-sectional association.

Results of the present study do not show a significant association between meeting the strength-training recommendation and self-reported overweight/obesity. While others have observed an association (with self-reported and objectively measured BMI),Footnote 45Footnote 46Footnote 47Footnote 48 BMI may not be an ideal health outcome in relation to strength training. Strength training may not result in substantial changes to a person’s BMI,Footnote 49 and conversely, BMI does not provide a complete picture of body composition.Footnote 50Footnote 51 Future work would benefit from looking at other measures of adiposity and health status.

A significant time trend (2000–2014) was observed for all age groups, suggesting small increases in adherence to the muscle-strengthening and balance recommendations. Bennie et al.,Footnote 31 using data from the COMPASS study, found that the prevalence of meeting the strength-training recommendation among secondary school students declined significantly, from 57.0% to 48.5%, between 2015 and 2019.

Other studies have observed increasing trends in muscle-strengthening exercise among adults. In Canada, using longitudinal data from the National Population Health Survey, which assessed PA using the same module from the 2000–2014 CCHS, PerksFootnote 52 found that weight training significantly increased from 1994 to 2011. Alongside increases in weight training, increases in total leisure PA were observed except among those aged 65 years and older.Footnote 52 Among Australian adults, the prevalence of sufficient muscle-strengthening activity increased from 6.4% to 12.0% (ptrend < 0.0001) between 2001 and 2010.Footnote 43 Using data from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys, Bennie et al.Footnote 53 found a small but statistically significant increase (29.1% to 30.3%, ptrend < 0.0001) in the prevalence of sufficient muscle-strengthening activity among adults in the United States between 2011 and 2017. There are no known studies that have looked at time trends in balance exercise.

Surveillance considerations

While using the 2000–2014 CCHS PAC provided a way to compare previous data with more recent data from the HLV-RR module, several differences between the modules limit the comparison. These differences include the sampling frame of the surveys; seasons of data collection; recall period (3 months for the older PAC vs. past 7 days for the new HLV-RR module); number of questions (22 activities in the older PAC vs. 2 items with broad examples in the new HLV-RR module); and activities/examples (activities in the older PAC grouped under “weight training,” “moderate-to-high impact” and “low-to-high impact,” based on assumptions of strength/balance contributions vs. activities in the new HLV-RR module presenting broad examples of muscle/bone-strengthening activities [lifting weights, carrying heavy loads, shovelling, sit-ups, running, jumping sports] and balance activities [yoga, tai chi, dance, tennis, volleyball and balance training]).

The new 2020 module may provide more room for interpretation of balance and muscle strengthening, whereas the old module may misclassify some activities based on the applied assumptions of the movements conducted. The new module question likely also captures activities beyond traditional weight lifting.

It is, however, important to acknowledge that the range of strength-training options/activities has evolved over time, with power yoga, Pilates and weight-based workouts, for example, becoming more popular. Therefore, what is defined as strength training, its promotion or marketing (including through the 24H Guidelines) and the equipment and resources available for this training may have influenced prevalence over time. While the prevalence of strength training in 2020 is provided alongside 2000–2014 trends as an exploratory exercise, it is not appropriate to directly compare the estimates.

Current Canadian estimates of adherence to the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendations using the new 2020 CCHS HLV-RR module exceed those observed internationally. Prevalence estimates are likely influenced by variation in the surveillance question(s) used.Footnote 35 Most population surveys ask specific questions about strength training, but several ask about a range of activities that could strengthen muscles or improve balance. International estimates are largely based on questions referencing traditional forms of strength training such as weight lifting or calisthenics. In fact, some surveys ask respondents to not include aerobic activities in their responses.Footnote 40Footnote 54 Many activities that would improve aerobic fitness could also strengthen muscles and improve balance. It is, however, not clear to what extent different strength-training activities influence health outcomes.

The new module used in the CCHS HLV-RR does not include a measure of intensity or duration. While current recommendations are based on minimum weekly frequencies, future work is needed to understand whether intensity and duration have important implications for health. In addition, the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendation in the 24H Guidelines was informed by resistance training studies. Therefore, it is recommended that future measures also assess resistance training separately. Future work is also needed to assess the reliability of the HLV-RR module to assess trends and to better understand how including different examples may change estimates, and whether the module requires further adjustment.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the use of large, nationally representative samples of Canadian youth and adults to examine historical trends and current prevalence of adherence to muscle/bone-strengthening and balance recommendations. Further, the HLV-RR module allowed for the examination of the sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics of those meeting recommendations. While it was not possible to assess the criterion validity of the new module, assessing associations with indicators of health provided a means to assess construct validity. Historically, the validity of muscle-strength training exercise questions has been rarely assessed,Footnote 35 largely due to a lack of comparison measures that require few resources to obtain.

All data used in this study are cross-sectional, making it impossible to examine causal associations with health or to ascertain within-person changes. However, repeated cross-sectional surveys account for the non-stationary nature of the Canadian population. It was also not possible to directly compare the older (2000–2014) and the newer (2020) results due to differences in methodology. Finally, in both modules, activities are self-reported and subject to recall and response biases.

Conclusions

Results of this study suggest that approximately half of Canadians meet the muscle/bone-strengthening recommendation but only 16% of older adults meet the balance recommendation from the 24H Guidelines. Temporal trends suggest that adherence to both recommendations increased between 2000 and 2014. Meeting either recommendation alone or in combination with sufficient MVPA is associated with better physical and mental health. Surveillance reporting on the muscle/bone-strengthening and balance components of the Canadian 24H Guidelines alongside the already recognized aerobic PA recommendation provides important information on another health behaviour associated with optimal health among Canadians.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study and interpretation of the data. SAP undertook the analysis with verification by JJL. SAP wrote the original draft. All authors critically revised and approved the final paper.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.