Original qualitative research – People with lived and living experience of methamphetamine use and admission to hospital: what harm reduction do they suggest needs to be addressed?

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: July 2023

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Cheryl Forchuk, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2; Jonathan Serrato, MScAuthor reference footnote 1; Leanne Scott, BScNAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.7.04

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Jonathan Serrato, Mental Health Nursing Research Alliance MHNRA – B3-110, P.O. Box 5777 STN B, 550 Wellington Road, London, ON N6C 0A7; Tel: 519-685-8500 ext. 75802; Email: jonathan.serrato@lhsc.on.ca

Suggested citation

Forchuk C, Serrato J, Scott L. People with lived and living experience of methamphetamine use and admission to hospital: What harm reduction do they suggest needs to be addressed? Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(7):338-47. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.7.04

Abstract

Introduction: People who use substances may access hospital services for treatment of infections and injuries, substance use disorder, mental health issues and other reasons. Our aim was to identify the experiences, issues and recommendations of people who use methamphetamine and have accessed hospital services.

Methods: Of the 114 people with lived and living experience of methamphetamine use recruited for a mixed-methods study conducted in southwestern Ontario, Canada, 104 completed the qualitative component. Interviews were conducted from October 2020 to April 2021. Participants were asked open-ended questions and the responses were analyzed using an ethnographic thematic approach.

Results: Negative patient–staff interactions included stigma and a lack of understanding of addiction and methamphetamine use, leading to distrust, avoidance of hospital care and reduced help-seeking and health care engagement. The consequences can be infections, unsafe needle use, discharge against medical advice and withdrawal. Almost all participants were in favour of in-hospital harm reduction strategies including safe consumption services, provision of sterile equipment and sharps containers, and withdrawal support. Clinical implications include education to reduce knowledge gaps about methamphetamine use and addiction and address stigma, which could facilitate the introduction of harm reduction strategies.

Conclusion: Although the strategies identified by participants could promote a safer care environment, improving therapeutic relationships through education of health care providers and hospital staff is an essential first step. The addition of in-hospital harm reduction strategies requires attention as the approach remains uncommon in hospitals in Canada.

Keywords: harm reduction, methamphetamine, hospitals, substance-related disorders, illicit drugs, stigma

Highlights

- Using open-ended questions, we interviewed 104 people with lived experience of methamphetamine use.

- Interviewees reported stigma and a lack of knowledge about addiction and substance use among health care providers and other hospital staff.

- Stigma and lack of trust can result in avoiding hospitals, reduced help-seeking and health care engagement, and, potentially, infections, discharge against medical advice and withdrawal.

- Safe consumption services, provision of sterile equipment and sharps containers, and withdrawal support were some of the recommended harm reduction strategies.

- Clinical implications include further education for health care providers to enhance therapeutic relationships, which could help introduce harm reduction strategies into hospitals.

Introduction

Methamphetamine use is associated with various negative health effects that have implications for chronic illnesses—dehydration and malnourishment,Footnote 1 bloodborne diseases,Footnote 2 respiratory diseases and increased hospitalizations,Footnote 3 dental issues,Footnote 4 seizures,Footnote 5 heart failure,Footnote 6 overdoses and mortality.Footnote 7

There is a growing call for harm reduction services to be provided in hospitals, particularly as this is the first point of care for many people.Footnote 8 Footnote 9 Footnote 10 But hospitals usually require that patients maintain abstinence,Footnote 11 which results in a conflict of interest when providing care to individuals who use substances. Safety for this particular patient population, as well as those around them, can be compromised if their needs are not addressed. Safety issues include discharge against medical advice, improper discarding of substance use equipment, pain and withdrawal.Footnote 8 Footnote 11

The mandate of security services for the safety of hospital staff and patients can be a further challenge because of the high frequency of interactions and searches of personal belongings, which can reinforce distrust and stigma.Footnote 8 People who use substances often describe negative experiences with law enforcement or security, both inside and outside the hospital.Footnote 12 These negative experiences range from criminalization due to substance use, to being asked to leave the hospital regardless of medical needs.Footnote 12

People hospitalized for substance-related issues have been found to be at greater risk for discharge from hospital against medical advice in CanadaFootnote 12 Footnote 13 Footnote 14 and in the United States,Footnote 13 Footnote 15 Footnote 16 particularly when there was no substance use intervention or service.Footnote 17 In one Canadian study, just over half of the participants who reported daily methamphetamine use discharged themselves against medical advice.Footnote 13 Comorbid substance use and mental illness have also been linked with shorter lengths of hospital stay in Canada,Footnote 18 the United StatesFootnote 19 and the United KingdomFootnote 20 than for the general patient population. On the other hand, people referred to psychiatric services demonstrated longer lengths of stay in CanadaFootnote 21 and Australia.Footnote 22 One study in Switzerland revealed that length of stay decreases with increases in number of hospitalizations, indicating difficulties transitioning to outpatient care.Footnote 23

Stigma persistently discourages people who use substances from seeking care. Perceived judgment or negative attitudesFootnote 24 and lack of attentionFootnote 25 have been reported and exemplify stigma. Stigma can also perpetuate the desire to use substances secretly and/or avoid accessing health servicesFootnote 26 Footnote 27 or result in discharges against medical advice, which can lead to poor quality practice and follow-up.Footnote 10 Stigma can also create barriers to care and inhibit help-seeking and self-reporting of substance use, especially among femalesFootnote 28 Footnote 29 Footnote 30 and transgender individuals.Footnote 31 Women and women who are pregnant have also reported these barriers to care as a result of heightened fears of the involvement of the child welfare service.Footnote 30 Footnote 32

Unlike in hospitals, harm reduction is well established in community agencies such as safe consumption sites. Without access to harm reduction approaches, people may reuse or share needlesFootnote 33 or reuse pipes.Footnote 34 Harm reduction in the hospital is warranted to provide safer access options: a key study conducted in London, Ontario, found that people who inject substances have a significantly higher incidence of new bloodstream infections when receiving inpatient treatment than outpatient treatment.Footnote 35 Tan et al.Footnote 35 also noted that people receiving outpatient treatment likely have lower risk behaviours or comorbidities, although a possible explanation is the lack of harm reduction supports in hospitals compared with the community. Furthermore, overdoses at a hospital-based overdose prevention site have been found to be significantly more likely to occur among people admitted as inpatients than among community-based clients.Footnote 36

Harm reduction practices seek to reduce the risks and harms associated with substance use through the provision of tools and services.Footnote 37 Supervised consumption facilities that provide designated spaces for people to use substances while supervised by trained staff are associated with reduced equipment sharing,Footnote 38 Footnote 39 public usageFootnote 38 and syringe litter.Footnote 39 Reductions in syringe littering have also been reported in cities with needle exchange programs that provide sterile supplies to people in exchange for used supplies.Footnote 40

It is also important for individuals who use substances to accept and want to use these harm reduction services. Previous studies have reported that harm reduction strategies have enhanced understandings of safety and have been positively viewed by people who use substances.Footnote 9 Footnote 41 Furthermore, except for in Toronto,Footnote 42 EdmontonFootnote 43 and Vancouver,Footnote 36 Footnote 44 harm reduction services in Canada are utilized and evaluated in community settings rather than in hospital settings. ScotlandFootnote 45 and AustraliaFootnote 46 allow the provision of harm reduction services such as needle exchange programs on hospital grounds, but this is not commonplace internationally. When supervised consumption services are successfully implemented in hospital settings, patients are supervised by trained staff (often with lived experience) in a personal injecting booth and are offered sterile supplies as well as education for safe use.Footnote 36 Footnote 42 Footnote 43 Footnote 44

The current literature on harm reduction in hospitals is limited. Understanding what is needed and what needs to be addressed in order to fill this research gap is a key aim of this study. We seek to record the experiences of people who use methamphetamine and learn what can be done to improve the hospital care they receive, the methamphetamine-specific harm reduction strategies they suggest for hospitals, and other issues that need to be resolved. In this article, we focus on the findings from the qualitative component of a mixed-methods study.

Methods

Design

This study was conducted in a large city in southwestern Ontario, Canada. Interviews commenced in October 2020 and were completed in April 2021. A qualitative component consisted of open-ended questions.

Data were collected once from a purposive sample of individuals with past or current experience of methamphetamine use and of hospital service use. The study developed a purposive sampling frame in order to maximize diversity by age, gender and service agencies accessed. Service agencies included hospitals, those serving people experiencing homelessness, primary care health services, and community mental health and addiction services.

We used a sampling frame to recruit a similar number of participants from the various agencies as well as similar numbers identifying as male and female. People who identified as nonbinary or other genders could also participate. Age groups were constructed (16–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and 80–85 years) in order to track participants' ages and inform recruitment as the study progressed (with the goal of recruiting at least one participant in each age group). Participants identifying as marginalized were prioritized in order to provide sufficient access to these groups to participate and be represented in the sample. Marginalized populations targeted were Indigenous people, Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, plus (2SLGBTQI+) people, and members of ethnic minority groups.

As this qualitative study was part of a mixed-methods study, our aim was to recruit at least 104 participants (with a maximum of 180) with past or current lived experience of methamphetamine use, including those in recovery. This minimum is in keeping with the sample size calculation set out by Bartlett et al.Footnote 47 A maximum of 180 participants was determined by the study's funding. This also meant the study would surpass the number of participants for qualitative saturation as detailed by Morse.Footnote 48

To be included, participants had to be between 16 and 85 years old; to have received services at a hospital; and to speak English sufficiently well to participate in the interview. Participants were excluded if they did not report any current or prior use of methamphetamine, even if they had used other substances. All participants provided informed consent.

Ethics approval was obtained from Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University's Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (Reference number: #115779).

Recruitment

The research team reached out to many programs across four hospitals in southwestern Ontario and community agencies. Research staff provided agency staff with the research protocol and recruitment posters to help them promote the project among clients. Prospective participants could call or email the research coordinator (JS) to arrange a time and place for the interview to be conducted. The research team also arranged specific days to visit drop-in services sites (e.g. shelters for people experiencing homelessness and a safe consumption site) to conduct outreach with potential participants.

To recruit as diverse a sample as possible, we relayed information about shortfalls in the purposive sampling frame to the hospital programs and community agencies to try to recruit participants who were lacking representation, and contacted agencies that served underrepresented populations such as youth, older adults, 2SLGBTQI+ and Indigenous people. Hospital personnel spoke to patients in their care about the project if they knew that they had a current or lived experience of methamphetamine use.

Procedure

As part of a larger mixed-methods study, interviewees participated in a qualitative discussion consisting of open-ended questions. Interviews were conducted by the three authors as well as three research coordinators (SH, SM, AP) and seven research assistants (SA, TA, NF, EG, CH, AJ, AY), all of whom had received training in qualitative methods and interviewing techniques. Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes.

Interview questions were designed to elicit participants' accounts of their experiences in hospital settings, issues regarding harm reduction (or lack thereof), suggestions for changes and what aspects of care should not be changed, recommendations and goals. The aim was to record a variety of viewpoints in order to capture unexpected and contrasting responses for inclusion in the analyses:

- What is your experience with the way things are currently within the hospitals for harm reduction and methamphetamine use?

- What are some of the issues with the current approach within the hospitals for harm reduction and methamphetamine use?

- What do you think should be changed regarding the current approaches to harm reduction?

- What are some aspects you would not change regarding the current approaches to harm reduction?

- How should a new approach help you with your goals?

- Do you have any other recommendations that may be useful to you or others who use methamphetamine?

Interviewers kept notes during the interview to help them follow up and elicit further information on a particular experience or opinion or ask for clarification. The qualitative component of the interview was audio-recorded and then transcribed by research staff for subsequent analyses (SA, NF, EG, CH, AJ, AL, ML).

Interviews were conducted via telephone or in-person. In-person interviews only occurred if both interviewer and interviewee could follow COVID-19 protocols and procedures. These in-person interviews were conducted in a spare meeting room at the service agencies. Interviewees who were inpatients at the time of the interview were interviewed over the telephone in accordance with hospital pandemic protocols. All participants received an honorarium of CAD 20 upon completion of the interview.

Data analysis

We used a thematic ethnographic method of analysisFootnote 49 to examine the broader cultural and social contexts surrounding participants with lived experience of methamphetamine use. The three authors conducted and reviewed the initial open coding and axial coding. We grouped the interview responses thematically and identified the themes, subthemes and suggestions for future considerations expressed by the participants. We colour-coded quotes based on the type of response and copied these into a document specified for that particular theme. The identified themes were then reviewed and critically appraised by all three authors working as a group.

All 104 transcripts were analyzed. Further analyses explored the influence of themes on one another to identify the sequence of issues that participants have experienced. The three authors collaborated to identify the themes and to then develop a model of the current state of care versus a preferred state. Quotes were reviewed and placed into a theme after the three authors had discussed and reached consensus as to the most appropriate fit for each; this ensured credibility and trustworthiness. Reflexivity activities included routine updates and discussions of the findings to date with the study's Advisory Group and Research Subcommittee, a team consisting of other researchers and analysts, to reduce any researcher bias.

Results

Demographics

Of the 114 participants recruited for this study, 104 completed the qualitative component of the study. The majority of the sample identified as male (n = 67) (see Table 1). Although the researchers targeted an equal number of males and females, fewer females reported substance use. A total of 13 participants identified as 2SLGBTQI+. The mean age of the sample was 35.5 years (range: 17–66), but no one aged over 70 years was identified for recruitment. A total of 52 participants reported that they were currently experiencing homelessness, and almost all (n = 102) reported experiencing homelessness in their lifetime.

| Characteristic | No. of participants, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 35.5 (12.5) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 67 (64) | |||

| Female | 36 (35) | |||

| Nonbinary | 1 (1) | |||

| Identified as 2SLGBTQI+ | 13 (13) | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 61 (59) | |||

| Indigenous | 24 (23) | |||

| Indigenous + White | 8 (8) | |||

| Black | 3 (3) | |||

| Latin American | 2 (2) | |||

| Other | 6 (6) | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 75 (72) | |||

| Married/common law/engaged | 16 (15) | |||

| Separated/divorced | 11 (11) | |||

| Widowed | 2 (2) | |||

| Education completed | ||||

| High school | 45 (43) | |||

| Elementary/primary school | 41 (39) | |||

| College/university | 18 (17) | |||

| Housing status | ||||

| Homeless | 52 (50) | |||

| Live alone | 25 (24) | |||

| Live with other relative or parents | 8 (8) | |||

| Inpatient | 7 (7) | |||

| Live with spouse/partner | 6 (6) | |||

| Live with unrelated person | 6 (6) | |||

Thematic analysis findings

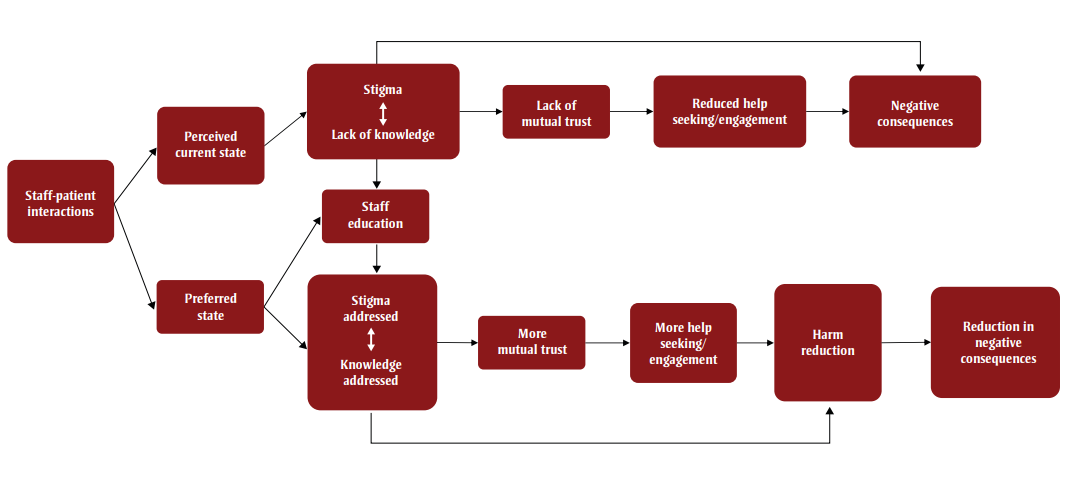

We identified a number of themes during the course of the interviews including stigma and a lack of knowledge, lack of trust and help-seeking, harm reduction strategies and negative consequences. Figure 1 illustrates the sequences and relationships between these themes.

Figure 1 - Text description

Figure 1 illustrates a model of perceived current state versus preferred state of hospital care. This figure contains the following nodes.

| Name of Theme (Node Label) | Distance from Root Node | Outward Connections to Other Nodes |

|---|---|---|

| "Staff-patient interactions" | 0 (Root Node) | "Perceived current state" "Preferred state" |

| "Perceived current state" | 1 | "Stigma <-> Lack of knowledge" |

| "Preferred state" | 1 | "Staff education", "Stigma addressed <-> Knowledge addressed" |

| "Stigma <-> Lack of knowledge" | 2 | "Lack of mutual trust" "Staff education" "Negative consequences" |

| "Staff education" | 2 | "Stigma addressed <-> Knowledge addressed" |

| "Stigma addressed <-> Knowledge addressed" | 2 | "More mutual trust", "Harm reduction" |

| "Lack of mutual trust" | 3 | "Reduced help seeing/engagement" |

| "More mutual trust" | 3 | "More help seeing/engagement" |

| "Reduced help seeing/engagement" | 4 | "Negative Consequences" |

| "More help seeing/engagement" | 4 | "Harm Reduction" |

| "Negative Consequences" | 5 | N/A |

| "Harm Reduction" | 5 | "Reduction in negative consequences" |

| "Reduction in negative consequences" | 6 | N/A |

Staff–patient interactions: stigma and lack of knowledge

Stigma was the issue most frequently mentioned during the interviews. Participants said that they felt they were less respected than the general patient population; were made to feel that their addiction was a "bad choice"; and had been shunned as a result. One participant said: "Where to start, who to ask and then I, and I try to ask or I try to approach it and I just get treated like, like just a piece of dirt, you know?"

The perceived stigma may be the result of a lack of knowledge about addiction and substance use, particularly methamphetamine use, on the part of health care providers and hospital staff. Many participants explained that there seemed to be a disconnect between themselves and the health care staff treating them, often citing differences in language. For example, people with lived experience may describe unregulated substances in terms of "points," while health care providers would ask about milligrams of usage.

Participants also described the lack of understanding of the lived experience. Some said that the broader understanding of addiction, such as traumatic events, are sometimes unacknowledged as a precursor for substance use. This lack of understanding can lead to their methamphetamine use being perceived as a morally "bad choice." Others noted that distinguishing between the clinical manifestation of methamphetamine use and a mental health crisis is problematic, leading to incorrect assumptions about them as a person.

So I just feel like, um, yeah, it's just, I don't know if they don't understand or if they don't want to understand, or if they just, 'cause there's a difference between someone who's suffering from psychosis, from drugs as per psychosis, mental health.

This lack of understanding of the clinical manifestations of methamphetamine use can lead to undertreatment of withdrawal symptoms. Participants found that health care providers either ignored their withdrawal symptoms or seemed unaware of symptoms and treatment. Regardless, participants considered that "…more focus needs to be put into withdrawal management."

Lack of trust and reduced help-seeking or health care engagement

The perceptions of stigma and lack of knowledge and understanding of substance use result in a lack of mutual trust between patient and health care provider. Participants expressed their general dissatisfaction with the health care they received, saying that they avoided disclosing their methamphetamine use. A large number were unwilling to seek help or engage with their health care.

Participants said that they did not seek health care in hospitals because of this combination of stigma, lack of understanding and trust, and medical needs (e.g. withdrawal) not being met. Some participants reported discharging themselves against medical advice. This could then lead to a worsening of symptoms and likely readmission. One participant explained: "Because a lot of us don't like hospitals. We won't, we won't go to the hospital for anything, because we get treated differently. We get like red flagged."

The presence of an individual with lived experience of methamphetamine use, such as a peer supporter, could be the necessary bridge in the therapeutic relationship between the patient and the health care team: "As a recovering addict, I know the importance of an addict speaking to an addict."

Negative consequences

Not engaging in health care can result in poorer health, infections, unsafe use of needles, discharge against medical advice and even death. Withdrawal was discussed in many different contexts, including the various effects of not using methamphetamine in hospital or not receiving medication to stave off adverse reactions. Participants described the physical and mental health consequences of withdrawal without any harm reduction strategies:

Withdrawal, there's been the possibility of people going violent, no self-awareness, you come down from the high and you're going like, I gotta get high again. They're forcing us to subdue to nothingness. It's like, how can you do that to us? It's like we're going through this addiction. They make you go through the withdrawal. They say, you should just toughen up.

Others recounted how lack of harm reduction can increase pain and risk of death and overdose:

Because, like, if they don't have harm reduction and, like, safety plans and stuff like that in the hospitals in the hospitals and stuff … I feel like a lot more people could be … in a lot more pain and have a lot more happen to them…. Like, a lot more people could die, overdose, stuff like that.

Recommended harm reduction strategies to reduce negative consequences

Safe consumption

The participants frequently discussed the concept of a safe consumption service. Many talked about a monitored service with hospital personnel assisting individuals. Opinions differed as to how much control supervising staff would have (i.e. administering the injection, monitoring effects or supporting after use). This could indicate a difference in beliefs to do with autonomy and attitudes towards support personnel.

They should have rooms like this [private consumption space] there in the hospital … paramedics have been through here 'cause like, people don't die here. A lot of people frown on this place and stuff, but you know, this place saves a lot of lives.

Many participants preferred the idea of a "safe space" where individuals could use methamphetamine privately, for their own safety and apart from the general patient population: "Just like make a little room for people who do, do stuff like that … just so that you feel safe, you know what I mean?"

Sterile equipment

Many participants described the need for sterile equipment to help prevent the spread of infection. Needle exchange programs at hospitals could be a way to prevent the reuse of needles and syringes:

… we have like a needle exchange and shit, and we need to have something similar [in] our half of the hospital … maybe there could be a worker from rehab or something like that, they can provide clean needles or whatever drugs… like utensils and things like that.

Some participants also suggested offering clean pipes to individuals who smoke methamphetamine in an effort to prevent reuse of pipes and the spread of infections: "If you have people [who smoke] make sure they have clean pipes all the time … So, they're not constantly, constantly using the old paraphernalia … Cause it's a bad way of … catching disease and things."

Using damaged or self-made pipes can also result in injury that requires medical assistance. One participant suggested: "Probably they should give us … safe injection tools like needles, and [needle] dropboxes, and also … clean pipes so that we're not using … broken glass pieces and straws to inhale."

Sharps waste containers

Some participants pointed out the need for sharps containers for discarding needles, thereby reducing the risk of accidental infection. Having easily accessible sharps containers in hospitals could also decrease the risk of individuals going outside and injecting methamphetamine on hospital property and discarding their needles where members of the public could be put at risk. Alternatively, hospitals could "have maybe a needle bin in the washroom."

Support for withdrawal

Many participants reported using in hospitals or leaving the hospital (often against medical advice) to use because they needed to stave off the effects of withdrawal. Medications to reduce the effects of withdrawal and induce calmness can prevent agitation and adverse health reactions. When prescribed such medications, people may be more willing to receive care and mitigate negative health consequences. With improved therapeutic relationships and greater trust, people receiving hospital care may have more positive interactions and be less averse to seeking help in the future.

'Cause, I don't know, I've never [had] withdrawal [symptoms], like I've never had [withdrawal symptoms coming] off crystal, but I guess some people do, like they get antsy or you know what I mean. So everyone's different in a way. But yeah, maybe medication that could help make someone obviously not as [antsy]. 'Cause an addict is an addict right. If they want to use, they're going to want to use. So … if you want them to stay in the hospital and get their treatment you're going to have to do something to take that edge off.

Discussion

People with lived and living experience of methamphetamine use perceived the current state of hospital care as rooted in a lack of knowledge of addiction and methamphetamine use. This negative basis for interaction results in a lack of mutual trust and reduced help-seeking or health care engagement, with patients either discharging themselves against medical advice or avoiding hospitals altogether. This, in turn, leads to negative health consequences with people not receiving the care they need and not receiving harm reduction interventions that can also prevent further consequences.

Based on qualitative findings and analyses, a preferred state of care would address stigma and lack of knowledge by educating hospital staff about addiction. Key to establishing therapeutic relationships is mutual trust building. Harm reduction strategies would then be provided as an additional solution to the immediate negative consequences of methamphetamine use.

Addressing stigma and lack of knowledge

This study revealed a large number of issues related to the provision of care for people who use methamphetamine; these issues need to be addressed before harm reduction strategies can be considered. Stigma and health care providers' lack of knowledge frustrated study participants and led to communication difficulties and a sense of discontent. Service providers have reported that it is difficult to assist individuals who use methamphetamine because they lack the knowledge about their specific needs,Footnote 1 an issue that would have to be addressed to implement harm reduction strategies with staff understanding and support. Lived experience support could also remedy this situation.Footnote 8

The lack of trust that results from these negative interactions, particularly when stigma was perceived, meant that individuals had to either hide their substance use or leave the hospital. Abstinence,Footnote 12 withdrawal symptoms including cravings, stigma, discrimination, hospital rules such as not leaving the hospital floor,Footnote 15 and recent intravenous substance useFootnote 13 have been given as reasons for discharge against medical advice; many of these reasons were brought up by study participants. Inevitably, not receiving or completing a course of treatment means that many people are at risk of worsening symptoms, readmission and even death. Risk of experiencing an overdose is heightened if using alone.Footnote 7 Footnote 38

Harm reduction strategies

Determining which harm reduction strategies to utilize can be challenging, particularly when they seem to contradict hospital policy and philosophy. Safe consumption and ways in which individuals can use safely in hospitals away from the general patient population were commonly discussed. Some participants liked the idea of monitored use with varying degrees of support, while others preferred full autonomy and the private use of a quiet room. In a 2019 qualitative study, Foreman-Mackey et al.Footnote 50 found the that use of a supervised consumption facility decreased the number of fatal overdoses.

Participants in the current study seemed to be aware of harm reduction strategies but collectively discussed a lack of access and availability. Many brought up the need for new equipment to prevent the spread of infection through sharing and/or reusing paraphernalia. A needle exchange program alone may not be appropriate as clients would have to leave the building and inject elsewhere.Footnote 9 Although a safe consumption site is a large step for a hospital to take, it may be necessary if there are concerns around unsupervised use in the vicinity. Previous research has revealed a number of benefits for safe consumption: an increase in referrals to addiction treatment services,Footnote 38 Footnote 39 Footnote 43 Footnote 44 reductions in public injection use,Footnote 38 Footnote 39 no fatalitiesFootnote 36 Footnote 38 Footnote 39 Footnote 43 and no increases in substance-related crime.Footnote 39 Footnote 43

Participants stated that sharps containers should be available in washrooms, as this is where individuals who use methamphetamine often inject.Footnote 51 It was also suggested that clean pipes be offered to individuals who do not use intravenously, which would prevent the reuse of pipes or the use of makeshift pipes from aluminum cans, light bulbsFootnote 34 and plastic straws, which can produce toxic vapours when lit.Footnote 52

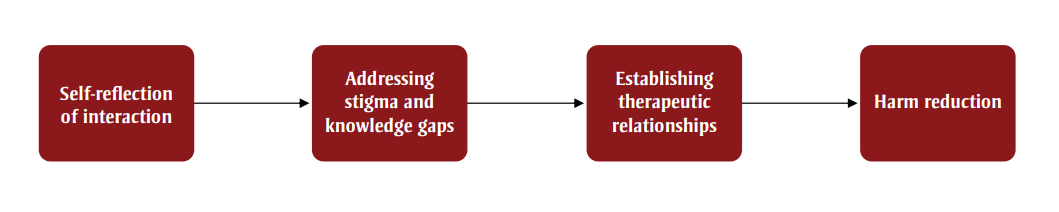

Clinical implications

Taking these issues into account, a preferred state of care would have clinical implications. Addressing negative interactions, stigma and knowledge gaps through self-reflection and education may help begin establishing positive therapeutic relationships. Educational interventions have been found to reduce stigma pertaining to substance use disorder.Footnote 53 Footnote 54 A greater understanding of addiction and harm reduction can enhance acceptance of strategies among staff and allow for a smoother introduction into practice. Previous research has indicated that further education on substance use and harm reduction can improve positive attitudesFootnote 55 and role adequacy in providing careFootnote 56 towards people with substance use disorder. Once trust has developed, people who use methamphetamine may gain the confidence to access harm reduction services.

Figure 2 illustrates the clinical implications of facilitating the introduction and utilization of harm reduction strategies in the hospital setting. Implementing harm reduction without addressing the previous steps could result in these practices not being fully understood, being provided ineffectively or being underutilized.

Figure 2 - Text description

Figure 2 illustrates the clinical implications of facilitating the introduction utilization of harm reduction strategies in a hospital setting. The figure contains a set of nodes in sequential order, where node 1 has an arrow pointing towards node 2.

| Node Number | Node Label |

|---|---|

| 1 | "Self-reflection of interaction" |

| 2 | "Addressing stigma and knowledge gaps" |

| 3 | "Establishing therapeutic relationships" |

| 4 | "Harm reduction" |

Philosophy and culture of care

The switch from the perceived state to the preferred state would involve a shift in the philosophy and culture of care from abstinence.Footnote 12 A change in current training would need to be augmented to reduce the effects of stigma and provide health care providers and hospital staff with the knowledge required to support people who use methamphetamine.Footnote 53 Footnote 54 The therapeutic relationship would need to change to encourage people to disclose their substance use, which many are afraid of doing in case they receive substandard care or even denial of services.Footnote 26 Suboptimal care has also been reported significantly more frequently among people who avoid care than those who do not,Footnote 57 and stigma has been found to be associated with both care avoidance and substandard care.Footnote 27 This reiterates the importance of engaging people with lived or living experience of methamphetamine use in care. In turn, the patient and health care provider can together develop a treatment plan that does not result in interpersonal or medical conflicts (e.g. medications interacting with consumed substances).

As highlighted in Figure 2, addressing stigma and enhancing therapeutic relationships must be addressed first so that people receiving hospital care want to access, and are able to access, available strategies. To advance straight to harm reduction implementation prior to addressing underlying issues in the health care system would likely lead to failure through lack of utilization and distrust.

Strengths and limitations

Analyzing the qualitative data of 104 people with lived experience, far exceeding saturation for a qualitative study, was a key strength of this study. This allowed for sharing a broad range of opinions, experiences and perspectives, all of which contributed to the findings of the study. Using an ethnographic lens also allows for the reporting of the collective experience of these 104 participants as opposed to individual accounts. This study comprehensively situates itself within the gap in the literature by highlighting the needs and difficulties faced by people with lived experience in the hospital setting. These findings oversee the overall experience rather than singular or individual issues.

This study also set out to recruit a diverse sample of participants in order to obtain representation from underrepresented populations. A total of 31% of the sample identified as Indigenous, which was larger than anticipated. Although the sample largely identified as male and White, the purposive sampling design of the study focussed on providing a voice to individuals who may not otherwise have had the chance to do so.

In terms of limitations, the study recruited largely from one city in Ontario, Canada, with five participants recruited from small towns outside of the city. There may be different experiences and issues to address in more rural locations as well as in larger cities. Other regions may have more resources and more accessible harm reduction services and sites, which would likely affect observations and experiences of study participants. It is therefore recommended that other regions within Canada explore issues prevalent in their communities.

We focussed specifically on people with lived and living experience of methamphetamine use. Although participants reported polysubstance use, the findings could be different for people who use substances other than methamphetamine.

We had few female participants in our study, which may have been due to stigma around disclosure. Future studies that focus primarily on underrepresented or marginalized groups are recommended.

Conclusion

To improve the quality of care for people who use methamphetamine, there needs to be an emphasis on the interactions between patient and health care provider and hospital staff before any progress can be made. It is important that individuals need to feel heard and respected before they seek treatment and access harm reduction interventions. Once therapeutic relationships built through trust are strengthened, the health care system can begin to provide treatment and harm reduction in an effective and accessible way. Further research is required to explore the feasibility of harm reduction provided in hospital as the approach is still in its infancy.

Acknowledgements

Health Canada's Substance Use and Addictions Program provided a funding grant for this study. We thank the following research coordinators and research assistants for their contributions to this study: Sara Husni, Shona Macpherson, Anne Peters, Sarah Adam, Tania Al-Jilawi, Niko Fragis, Emily Guarasci, Courtney Hillier, Ashraf Janmohammad, Amy Lewis, Mark Lynch and Annie Yang.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' contributions and statement

CF – Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS – Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LS – Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The content and views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.