Evidence synthesis – Indigenous people’s experiences of primary health care in Canada: a qualitative systematic review

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: April 2024

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Geneveave Barbo, RN, MN, MClScAuthor reference footnote 1; Sharmin Alam, MAAuthor reference footnote 2

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.4.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended Attribution

Research article by Barbo G et al. in the HPCDP Journal licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Author references

Correspondence

Geneveave Barbo, College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan, Health Science Building - 1A10, Box 6, 107 Wiggins Road, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E5; Tel: 306-966-6221; Email: g.barbo@usask.ca

Suggested citation

Barbo G, Alam S. Indigenous people’s experiences of primary health care in Canada: a qualitative systematic review. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2024;44(4):131-51. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.4.01

Abstract

Introduction: Indigenous people in Canada encounter negative treatment when accessing primary health care (PHC). Despite several qualitative accounts of these experiences, there still has not been a qualitative review conducted on this topic. In this qualitative systematic review, we aimed to explore Indigenous people’s experiences in Canada with PHC services, determine urban versus rural or remote differences and identify recommendations for quality improvement.

Methods: This review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute’s methodology for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and Web of Science as well as grey literature and ancestry sources were used to identify relevant articles. Ancestry sources were obtained through reviewing the reference lists of all included articles and determining the ones that potentially met the eligibility criteria. Two independent reviewers conducted the initial and full text screening, data extraction and quality assessment. Once all data were gathered, they were synthesized following the meta-aggregation approach (PROSPERO CRD42020192353).

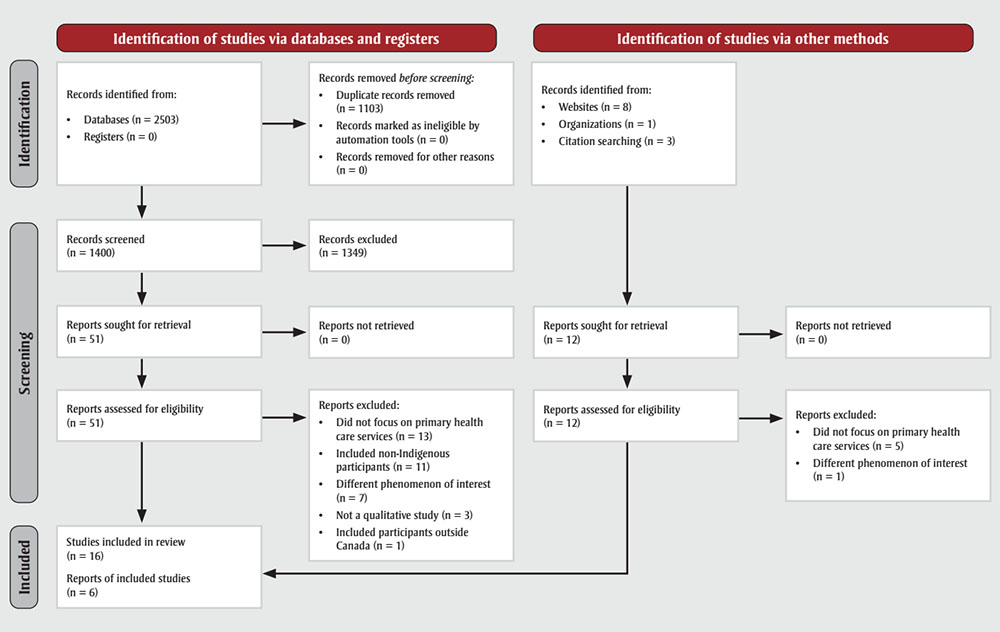

Results: The search yielded a total of 2503 articles from the academic databases and 12 articles from the grey literature and ancestry sources. Overall, 22 articles were included in this review. Three major synthesized findings were revealed—satisfactory experiences, discriminatory attitudes and systemic challenges faced by Indigenous patients—along with one synthesized finding on their specific recommendations.

Conclusion: Indigenous people value safe, accessible and respectful care. The discrimination and racism they face negatively affect their overall health and well-being. Hence, it is crucial that changes in health care practice, structures and policy development as well as systemic transformation be implemented immediately.

Keywords: Indigenous people, primary health care, health services accessibility, systematic review, Canada

Highlights

- This is the first qualitative systematic review to explore the experiences of Indigenous people with primary health care services across Canada.

- Following Joanna Briggs Institute’s systematic reviews of qualitative evidence methodology, this review included six academic databases as well as grey literature and ancestry sources.

- The experiences of Indigenous people accessing primary health care in Canada have been described as supportive and respectful in some cases, but also heavily included discriminatory attitudes and systemic challenges.

- Indigenous people living in rural or remote communities reported greater concern about privacy, confidentiality and accessibility compared to those residing in urban locations.

Introduction

The 1946 Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) established that every human being has the fundamental right to the highest attainable standard of health.Footnote 1 Nevertheless, to this day, health inequities continue to exist worldwide.Footnote 2 Health inequities are systematic differences in the health status of various population groups caused by unequal distribution of social determinants of health that further disadvantage those who are already socially vulnerable.Footnote 2Footnote 3 The WHO and other public health advocates assert the importance of investing in primary health care (PHC) as a means of addressing health inequities within countries.Footnote 4Footnote 5

In Canada, PHC services have been offered to all eligible residents through the universal public health coverage, also known as Medicare.Footnote 6 Medicare is governed by the 1984 Canada Health Act, which ensures the delivery of health care services (including PHC) and adherence to the five core principles of public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability and accessibility.Footnote 7 In 2000, a PHC reform was agreed upon and launched by the federal, provincial and territorial governments, with the primary goal of improving service access, service quality and health equity as well as responsiveness to patients’ and communities’ needs.Footnote 6Footnote 8 Yet, PHC access and quality issues continue to persist, particularly for socially marginalized populations, such as in the case of Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 9Footnote 10 Social marginalization is often defined as social exclusion due to a lack of power, resources and status that leads to limited opportunity or accessibility.Footnote 11

Numerous studies have highlighted barriers faced by Indigenous people who reside in urban and rural or remote locations when accessing PHC services, such as discrimination, racism, lack of culturally safe care and inaccessible care.Footnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15 Despite several qualitative accounts of these negative experiences, a deep search of the literature indicates that there still has not been a qualitative review conducted on this topic. Addressing this literature gap may assist policy makers, health care managers and professionals, and researchers in identifying key areas for improving PHC access and quality across Canada.

Accordingly, we aimed to explore the following research questions:

- What are the experiences and perspectives of Indigenous people with PHC services in Canada?

- How do these experiences and perspectives differ when comparing PHC services provided in urban versus rural or remote settings?

- What are the recommendations of Indigenous people to improve the quality of PHC services delivered in Canada?

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42020192353).

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

Our review was guided by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence;Footnote 16 the detailed protocol has been described elsewhere.Footnote 17 English and French qualitative and mixed-methods articles were considered for inclusion if they focussed on first- or second-hand experiences of Indigenous people in Canada when receiving PHC services. There were no restrictions with respect to publication year or research participants’ age, gender, medical condition or geographical location.

A preliminary search of CINAHL and PubMed was conducted to identify keywords and terms relevant to the research questions. A complete search strategy was then developed and tailored to each selected database: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and Web of Science (Table 1). Grey literature was also searched on Google Scholar, Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses and other relevant websites (e.g. Native Health Database and National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health). Furthermore, the reference list of each included article was examined to identify any additional studies for the review in order to obtain ancestry sources.

| MEDLINE | CINAHL | PUBMED | PSYCINFO | EMBASE | WEB OF SCIENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovid MEDLINE ALL 1946 to 21 December 2021 |

CINAHL Plus with full text | N/A | APA PsycInfo 1806 to December week 2, 2021 |

Embase 1996 to December week 2, 2021 |

Web of Science Core Collection (all indexes: SCI‑EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‑S, CPCI‑SSH, BKCI‑S, BKCI‑SSH, ESCI, CCR‑EXPANDED) |

| 1. content analysis.mp. | S1. TI content analysis* OR AB content analysis* | #1. content analysis[Title/Abstract] | 1. content analysis.mp. | 1. content analysis.mp. | 1. TI=content analysis* OR AB=content analysis* |

| 2. descriptive.mp. | S2. TI descriptive OR AB descriptive | #2. descriptive[Title/Abstract] | 2. descriptive.mp. | 2. descriptive.mp. | 2. TI=descriptive OR AB=descriptive |

| 3. discourse.mp. | S3. TI discourse OR AB discourse | #3. discourse[Title/Abstract] | 3. discourse.mp. | 3. discourse.mp. | 3. TI=discourse OR AB=discourse |

| 4. ethno*.mp. | S4. TI ethno* OR AB ethno* | #4. ethno*[Title/Abstract] | 4. ethno*.mp. | 4. ethno*.mp. | 4. TI=ethno* OR AB=ethno* |

| 5. exploratory.mp. | S5. TI exploratory OR AB exploratory | #5. exploratory[Title/Abstract] | 5. exploratory.mp. | 5. exploratory.mp. | 5. TI=exploratory OR AB=exploratory |

| 6. grounded theory.mp. | S6. TI grounded theory OR AB grounded theory | #6. grounded theory[Title/Abstract] | 6. grounded theory.mp. | 6. grounded theory.mp. | 6. TI=grounded theory OR AB=grounded theory |

| 7. interpretive.mp. | S7. TI interpretive OR AB interpretive | #7. interpretive[Title/Abstract] | 7. interpretive.mp. | 7. interpretive.mp. | 7. TI=interpretive OR AB=interpretive |

| 8. interview*.mp. | S8. TI interview OR AB interview | #8. interview*[Title/Abstract] | 8. interview*.mp. | 8. interview*.mp. | 8. TI=interview OR AB=interview |

| 9. mixed method*.mp. | S9. TI mixed method* OR AB mixed method* | #9. mixed method*[Title/Abstract] | 9. mixed method*.mp. | 9. mixed method*.mp. | 9. TI=mixed method* OR AB=mixed method* |

| 10. multi* method*.mp. | S10. TI multi* method* OR AB multi* method* | #10. multi* method*[Title/Abstract] | 10. multi* method*.mp. | 10. multi* method*.mp. | 10. TI=multi* method* OR AB=multi* method* |

| 11. narrative.mp. | S11. TI narrative OR AB narrative | #11. narrative[Title/Abstract] | 11. narrative.mp. | 11. narrative.mp. | 11. TI=narrative OR AB=narrative |

| 12. phenomenolog*.mp. | S12. TI phenomenolog* OR AB phenomenolog* | #12. phenomenolog* [Title/Abstract] | 12. phenomenolog*.mp. | 12. phenomenolog*.mp. | 12. TI=phenomenolog* OR AB=phenomenolog* |

| 13. qualitative.mp. | S13. TI qualitative OR AB qualitative | #13. qualitative[Title/Abstract] | 13. qualitative.mp. | 13. qualitative.mp. | 13. TI=qualitative OR AB=qualitative |

| 14. thematic*.mp. | S14. TI thematic* OR AB thematic* | #14. thematic*[Title/Abstract] | 14. thematic*.mp. | 14. thematic*.mp. | 14. TI=thematic* OR AB=thematic* |

| 15. theme*.mp. | S15. TI theme* OR AB theme* | #15. theme*[Title/Abstract] | 15. theme*.mp. | 15. theme*.mp. | 15. TI=theme* OR AB=theme* |

| 16. case studies.mp. | S16. TI case studies OR AB case studies | #16. case studies[Title/Abstract] | 16. case studies.mp. | 16. case studies.mp. | 16. TI=case studies OR AB=case studies |

| 17. focused group discussions.mp. | S17. TI focused group discussions OR AB focused group discussions | #17. focused group discussions[Title/Abstract] | 17. focused group discussions.mp. | 17. focused group discussions.mp. | 17. TI=focused group discussions OR AB=focused group discussions |

| 18. Empirical Research/ | N/A | N/A | 18. Empirical Research/ | 18. Empirical Research/ | N/A |

| 19. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 | S18. S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 | #18. #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 | 19. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 | 19. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 | 18. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 |

| 20. attitude*.mp. | S19. TI attitude* OR AB attitude* | #19. attitude*[Title/Abstract] | 20. attitude*.mp. | 20. attitude*.mp. | 19. TI=attitude* OR AB=attitude* |

| 21. belief*.mp. | S20. TI belief* OR AB belief* | #20. belief*[Title/Abstract] | 21. belief*.mp. | 21. belief*.mp. | 20. TI=belief* OR AB=belief* |

| 22. experience*.mp. | S21. TI experience* OR AB experience* | #21. experience*[Title/Abstract] | 22. experience*.mp. | 22. experience*.mp. | 21. TI=experience* OR AB=experience* |

| 23. opinion*.mp. | S22. TI opinion* OR AB opinion* | #22. opinion*[Title/Abstract] | 23. opinion*.mp. | 23. opinion*.mp. | 22. TI=opinion* OR AB=opinion* |

| 24. perception*.mp. | S23. TI perception* OR AB perception* | #23. perception*[Title/Abstract] | 24. perception*.mp. | 24. perception*.mp. | 23. TI=perception* OR AB=perception* |

| 25. perspective*.mp. | S24. TI perspective* OR AB perspective* | #24. perspective*[Title/Abstract] | 25. perspective*.mp. | 25. perspective*.mp. | 24. TI=perspective* OR AB=perspective* |

| 26. satisfaction.mp. | S25. TI satisfaction OR AB satisfaction | #25. satisfaction[Title/Abstract] | 26. satisfaction.mp. | 26. satisfaction.mp. | 25. TI=satisfaction OR AB=satisfaction |

| 27. value*.mp. | S26. TI value* OR AB value* | #26. value*[Title/Abstract] | 27. value*.mp. | 27. value*.mp. | 26. TI=value* OR AB=value* |

| 28. view*.mp. | S27. TI view* OR AB view* | #27. view*[Title/Abstract] | 28. view*.mp. | 28. view*.mp. | 27. TI=view* OR AB=view* |

| 29. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 | S28. S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 | #28. #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 | 29. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 | 29. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 | 28. 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 |

| 30. aborigin*.mp. | S29. TI aborigin* OR AB aborigin* | #29. aborigin*[Title/Abstract] | 30. aborigin*.mp. | 30. aborigin*.mp. | 29. TI=aborigin* OR AB=aborigin* |

| 31. First Nation*.mp. | S30. TI First Nation* OR AB First Nation* | #30. First Nation*[Title/Abstract] | 31. First Nation*.mp. | 31. First Nation*.mp. | 30. TI=First Nation* OR AB=First Nation* |

| 32. indigen*.mp. | S31. TI indigen* OR AB indigen* | #31. indigen*[Title/Abstract] | 32. indigen*.mp. | 32. indigen*.mp. | 31. TI=indigen* OR AB=indigen* |

| 33. Inuit*.mp. | S32. TI Inuit* OR AB Inuit* | #32. Inuit*[Title/Abstract] | 33. Inuit*.mp. | 33. Inuit*.mp. | 32. TI=Inuit* OR AB=Inuit* |

| 34. Metis.mp. | S33. TI Metis OR AB Metis | #33. Metis[Title/Abstract] | 34. Metis.mp. | 34. Metis.mp. | 33. TI=Metis OR AB=Metis |

| 35. native*.mp. | S34. TI native* OR AB native* | #34. native*[Title/Abstract] | 35. native*.mp. | 35. native*.mp. | 34. TI=native* OR AB=native* |

| 36. Indian*.mp. | S35. TI Indian* OR AB Indian* | #35. Indian*[Title/Abstract] | 36. Indian*.mp. | 36. Indian*.mp. | 35. TI=Indian* OR AB=Indian* |

| 37. 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 | S36. S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33 or S34 or S35 | #36. #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 | 37. 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 | 37. 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 | 36. 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 |

| 38. Canad*.mp. | S37. TI Canad* OR AB Canad* | #37. Canad*[Title/Abstract] | 38. Canad*.mp. | 38. Canad*.mp. | 37. TI=Canad* OR AB=Canad* |

| 39. Alberta*.mp. | S38. TI Alberta* OR AB Alberta* | #38. Alberta*[Title/Abstract] | 39. Alberta*.mp. | 39. Alberta*.mp. | 38. TI=Alberta* OR AB=Alberta* |

| 40. British Columbia.mp. | S39. TI British Columbia OR AB British Columbia | #39. British Columbia[Title/Abstract] | 40. British Columbia.mp. | 40. British Columbia.mp. | 39. TI=British Columbia OR AB=British Columbia |

| 41. Manitoba*.mp. | S40. TI Manitoba* OR AB Manitoba* | #40. Manitoba*[Title/Abstract] | 41. Manitoba*.mp. | 41. Manitoba*.mp. | 40. TI=Manitoba* OR AB=Manitoba* |

| 42. New Brunswick.mp. | S41. TI New Brunswick OR AB New Brunswick | #41. New Brunswick[Title/Abstract] | 42. New Brunswick.mp. | 42. New Brunswick.mp. | 41. TI=New Brunswick OR AB=New Brunswick |

| 43. Newfoundland and Labrador.mp. | S42. TI Newfoundland and Labrador OR AB Newfoundland and Labrador | #42. Newfoundland and Labrador[Title/Abstract] | 43. Newfoundland and Labrador.mp. | 43. Newfoundland and Labrador.mp. | 42. TI=Newfoundland Labrador OR AB=Newfoundland Labrador |

| 44. Nova Scotia.mp. | S43. TI Nova Scotia OR AB Nova Scotia | #43. Nova Scotia[Title/Abstract] | 44. Nova Scotia.mp. | 44. Nova Scotia.mp. | 43. TI=Nova Scotia OR AB=Nova Scotia |

| 45. Ontario.mp. | S44. TI Ontario OR AB Ontario | #44. Ontario[Title/Abstract] | 45. Ontario.mp. | 45. Ontario.mp. | 44. TI=Ontario OR AB=Ontario |

| 46. Prince Edward Island.mp. | S45. TI Prince Edward Island OR AB Prince Edward Island | #45. Prince Edward Island[Title/Abstract] | 46. Prince Edward Island.mp. | 46. Prince Edward Island.mp. | 45. TI=Prince Edward Island OR AB=Prince Edward Island |

| 47. Quebec*.mp. | S46. TI Quebec* OR AB Quebec* | #46. Quebec*[Title/Abstract] | 47. Quebec*.mp. | 47. Quebec*.mp. | 46. TI=Quebec* OR AB=Quebec* |

| 48. Saskatchewan.mp. | S47. TI Saskatchewan OR AB Saskatchewan | #47. Saskatchewan[Title/Abstract] | 48. Saskatchewan.mp. | 48. Saskatchewan.mp. | 47. TI=Saskatchewan OR AB=Saskatchewan |

| 49. Northwest Territories.mp. | S48. TI Northwest Territories OR AB Northwest Territories | #48. Northwest Territories[Title/Abstract] | 49. Northwest Territories.mp. | 49. Northwest Territories.mp. | 48. TI=Northwest Territories OR AB=Northwest Territories |

| 50. Nunavut.mp. | S49. TI Nunavut OR AB Nunavut | #49. Nunavut[Title/Abstract] | 50. Nunavut.mp. | 50. Nunavut.mp. | 49. TI=Nunavut OR AB=Nunavut |

| 51. Yukon.mp. | S50. TI Yukon OR AB Yukon | #50. Yukon[Title/Abstract] | 51. Yukon.mp. | 51. Yukon.mp. | 50. TI=Yukon OR AB=Yukon |

| 52. 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 | S51. S37 or S38 or S39 or S40 or S41 or S42 or S43 or S44 or S45 or S46 or S47 or S48 or S49 or S50 | #51. #37 or #38 or #39 or #40 or #41 or #42 or #43 or #44 or #45 or #46 or #47 or #48 or #49 or #50 | 52. 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 | 52. 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 | 51. 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 |

| 53. primary care.mp. | S52. TI primary care OR AB primary care | #52. primary care[Title/Abstract] | 53. primary care.mp. | 53. primary care.mp. | 52. TI=primary care OR AB=primary care |

| 54. primary health care.mp. | S53. TI primary health care OR AB primary health care | #53. primary health care[Title/Abstract] | 54. primary health care.mp. | 54. primary health care.mp. | 53. TI=primary health care OR AB=primary health care |

| 55. primary healthcare.mp. | S54. TI primary healthcare OR AB primary healthcare | #54. primary healthcare[Title/Abstract] | 55. primary healthcare.mp. | 55. primary healthcare.mp. | 54. TI=primary healthcare OR AB=primary healthcare |

| 56. clinic*.mp. | S55. TI clinic* OR AB clinic* | #55. clinic*[Title/Abstract] | 56. clinic*.mp. | 56. clinic*.mp. | 55. TI=clinic* OR AB=clinic* |

| 57. outpatient*.mp. | S56. TI outpatient* OR AB outpatient* | #56. outpatient*[Title/Abstract] | 57. outpatient*.mp. | 57. outpatient*.mp. | 56. TI=outpatient* OR AB=outpatient* |

| 58. ambulatory.mp. | S57. TI ambulatory OR AB ambulatory | #57. ambulatory[Title/Abstract] | 58. ambulatory.mp. | 58. ambulatory.mp. | 57. TI=ambulatory OR AB=ambulatory |

| 59. community care.mp. | S58. TI community care OR AB community care | #58. community care[Title/Abstract] | 59. community care.mp. | 59. community care.mp. | 58. TI=community care OR AB=community care |

| 60. community health care.mp. | S59. TI community health care OR AB community health care | #59. community health care[Title/Abstract] | 60. community health care.mp. | 60. community health care.mp. | 59. TI=community health care OR AB=community health care |

| 61. community health services.mp. | S60. TI community health services OR AB community health services | #60. community health services[Title/Abstract] | 61. community health services.mp. | 61. community health services.mp. | 60. TI=community health services OR AB=community health services |

| 62. general practi*.mp. | S61. TI general practi* OR AB general practi* | #61. general practi*[Title/Abstract] | 62. general practi*.mp. | 62. general practi*.mp. | 61. TI =general practi* OR AB=general practi* |

| 63. family physician*.mp. | S62. TI family physician* OR AB family physician* | #62. family physician*[Title/Abstract] | 63. family physician*.mp. | 63. family physician*.mp. | 62. TI=family physician* OR AB=family physician* |

| 64. family doctor*.mp. | S63. TI family doctor* OR AB family doctor* | #63. family doctor*[Title/Abstract] | 64. family doctor*.mp. | 64. family doctor*.mp. | 63. TI=family doctor* OR AB=family doctor* |

| 65. Health Services, Indigenous/ | S64. TI nurse practi* OR AB nurse practi* | #64. Primary Health Care/ | 65. Health Care Services/ | 65. health service/ | 64. TI=nurse practi* OR AB=nurse practi* |

| 66. Preventive Health Services/ | S65. TI midwives OR AB midwives | #65. Community Health Services/ | 66. primary health care/ | 66. primary health care/ | 65. TI=midwives OR AB=midwives |

| 67. nurse practi*.mp. | S66. TI midwife* OR TI midwife* | #66. Health Services, Indigenous/ | 67. nurse practi*.mp. | 67. nurse practi*.mp. | 66. TI=midwife* OR TI=midwife* |

| 68. midwives.mp. | S67. TI pharmacist* OR AB pharmacist* | #67. Preventive Health Services/ | 68. midwives.mp. | 68. midwives.mp. | 67. TI=pharmacist* OR AB=pharmacist* |

| 69. midwife*.mp. | S68. TI nurse OR AB nurse | #68. nurse practi*[Title/Abstract] | 69. midwife*.mp. | 69. midwife*.mp. | 68. TI=nurse OR AB=nurse |

| 70. pharmacist*.mp. | S69. TI nurses OR AB nurses | #69. midwives [Title/Abstract] | 70. pharmacist*.mp. | 70. pharmacist*.mp. | 69. TI=nurses OR AB=nurses |

| 71. nurse.mp. | S70. TI physiotherapist* OR AB physiotherapist* | #70. midwife*[Title/Abstract] | 71. nurse.mp. | 71. nurse.mp. | 70. TI=physiotherapist* OR AB=physiotherapist* |

| 72. nurses.mp. | S71. TI social worker* OR AB social worker* | #71. pharmacist*[Title/Abstract] | 72. nurses.mp. | 72. nurses.mp. | 71. TI=social worker* OR AB=social worker* |

| 73. physiotherapist*.mp. | S72. TI dietician* OR AB dietician* | #72. nurse[Title/Abstract] | 73. physiotherapist*.mp. | 73. physiotherapist*.mp. | 72. TI=dietician* OR AB=dietician* |

| 74. social worker*.mp. | N/A | #73. nurses[Title/Abstract] | 74. social worker*.mp. | 74. social worker*.mp. | N/A |

| 75. dietician*.mp. | N/A | #74. physiotherapist*[Title/Abstract] | 75. dietician*.mp. | 75. dietician*.mp. | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | #75. social worker*[Title/Abstract] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | #76. dietician*[Title/Abstract] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 76. 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 | S73. S52 or S53 or S54 or S55 or S56 or S57 or S58 or S59 or S60 or S61 or S62 or S63 or S64 or S65 or S66 or S67 or S68 or S69 or S70 or S71 or S72 | #77. #52 or #53 or #54 or #55 or #56 or #57 or #58 or #59 or #60 or #61 or #62 or #63 or #64 or #65 or #66 or #67 or #68 or #69 or #70 or #71 or #72 or #73 or #74 or #75 or #76 | 76. 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 | 76. 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 | 73. 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 |

| 77. 19 and 29 and 37 and 52 and 76 | S74. S18 and S28 and S36 and S51 and S73 | #78. #18 and #28 and #36 and #51 and #77 | 77. 19 and 29 and 37 and 52 and 76 | 77. 19 and 29 and 37 and 52 and 76 | 74. 18 and 28 and 36 and 51 and 73 |

| 78. Filter: English and French | S75. Filter: English and French | #79. Filter: English and French | 78. Filter: English and French | 78. Filter: English and French | 75. Filter: English and French |

Study selection

Following the search, all identified citations were uploaded on Rayyan.Footnote 18 Next, two authors (GB and SA) independently screened the articles’ titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. They then independently examined selected articles in full. Reasons for excluding certain articles were noted, and no major discrepancy arose between the two reviewers; hence, the assistance of a third reviewer was not needed. Once all included articles were identified, they performed an independent quality assessment using JBI’s Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research.Footnote 19

Data extraction and synthesis

All pertinent data from the included studies were then retrieved using the JBI data extraction tool.Footnote 16 The extracted data included information on the studies’ methodology, approach to analysis, phenomena of interest, geographical location, participant characteristics, findings and illustrations. These data were then synthesized following JBI’s meta-aggregation approach; the findings and illustrations were aggregated into categories and further grouped together to create a comprehensive set of synthesized findings. Finally, consistent with Munn et al.,Footnote 20 these synthesized findings were assigned a ConQual score to demonstrate their dependability and credibility.

Results

The search yielded a total of 2503 articles from the academic databases and 12 articles from the grey literature and ancestry searches. Overall, 22 articles were included in this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram of the search results and study selection process.Footnote 21 The methodological quality of all included articles was moderate to high; therefore, no studies were excluded following their appraisal (Table 2).

Figure 1 - Text description

| Step | Identification of studies via databases and registers | Identification of studies via other methods | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | Records identified from:

|

Records removed before screening:

|

Records identified from:

|

|

| Screening | Records screened (n = 1400) | Records excluded (n = 1349) | N/A | |

| Reports sought for retrieval (n = 51) | Reports not retrieved (n = 0) | Reports sought for retrieval (n = 12) | Reports not retrieved (n = 0) | |

| Reports assessed for eligibility (n = 51) | Reports excluded:

|

Reports assessed for eligibility (n = 12) | Reports excluded:

|

|

| Included | Studies included in review (n = 16) Reports of included studies (n = 6) |

|||

| Reference | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnabe et al.Footnote 38 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Bird et al.Footnote 36 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Browne and FiskeFootnote 32 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bucharski et al.Footnote 37 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Burns et al.Footnote 12 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Corosky and BlystadFootnote 22 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Fontaine et al.Footnote 13 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fraser and NadeauFootnote 14 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| GhoshFootnote 23 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Goodman et al.Footnote 15 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| GormanFootnote 34 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| HaydenFootnote 33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Howard et al.Footnote 39 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Howell-JonesFootnote 28 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jacklin et al.Footnote 35 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| MacDonald et al.Footnote 24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Monchalin et al.Footnote 30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| MonchalinFootnote 29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| OelkeFootnote 25 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Russell and de LeeuwFootnote 26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Tait NeufeldFootnote 31 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Varcoe et al.Footnote 27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| % Yes | 68 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 64 | 50 | 100 | 95 | 100 |

Characteristics of included studies

The detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 3. Articles were published between 2001 and 2020. Various qualitative approaches were used in these studies. These approaches included participatory research design,Footnote 12Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27 Indigenous methodologies,Footnote 13Footnote 15Footnote 24Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31 ethnography,Footnote 25Footnote 27Footnote 32Footnote 33 phenomenology,Footnote 34Footnote 35 case study,Footnote 14Footnote 36 qualitative description,Footnote 12Footnote 37 grounded theoryFootnote 38 and mixed methods.Footnote 39 Eleven out of 22 studies represented experiences from major Canadian metropolitan areas, including Calgary,Footnote 25Footnote 38 Edmonton,Footnote 37 Ottawa,Footnote 23 Toronto,Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 34 VancouverFootnote 15Footnote 28 and Winnipeg,Footnote 13Footnote 31 while 10 studies were conducted in rural or remote communities within the provinces of British Columbia,Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 39 Manitoba,Footnote 33 Nova Scotia,Footnote 12Footnote 24 OntarioFootnote 24 and QuebecFootnote 14 and within the Canadian territories of NunavutFootnote 22 and Northwest Territories.Footnote 32 Finally, one article included findings from multiple provinces and locations, with participants from urban southern and rural Alberta, urban northern and remote northern Ontario, and rural British Columbia.Footnote 35 The categorization of urban versus rural or remote settings was based on the study setting as defined by the authors as well as by the population density; urban areas are characterized as having at least 400 people per square kilometre, and the opposite is true (< 400/km2) for rural or remote regions.Footnote 40

Research participants of included studies were from First Nations, Métis and Inuit background, and overall were between the ages of 16 and 79 years. Their reasons for seeking PHC and their pre-existing medical conditions also varied (e.g. cancer, arthritis, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, human immunodeficiency virus and mental health disorders).

| Author(s) | Purpose of study | Approach | Method | Participants (n) | Context | Author conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnabe et al.Footnote 38 | To understand the experiences of urban First Nations and Métis patients accessing and navigating the health system for inflammatory arthritis care | Patient and Community Engagement Research and grounded theory | Focus groups, semistructured interviews, participant observations and questionnaires | First Nations and Métis women (11) | Urban, Calgary, Alberta | Greater decision-making support regarding pharmacotherapy is required to optimize the management of inflammatory arthritis. |

| Bird et al.Footnote 36 | To explore the experiences with diabetes of Inuit participants living in a small rural community | Multi–case study approach | Semistructured interviews and participant observations | Inuit men (3) and woman (1) | Remote, Baffin Island, Nunavut | Accessibility was a concern with respect to foods, health knowledge, language interpretation and health services |

| Browne and FiskeFootnote 32 | To gain an understanding of First Nations women’s encounters with mainstream health care services | Critical and feminist ethnographic approaches | Semistructured interviews and field notes | First Nations women (10) | Remote, Northwestern Canada | Influences of racial and gender stereotypes were revealed in the participants’ experiences |

| Bucharski et al.Footnote 37 | To identify Indigenous women’s perspectives on the characteristics of culturally appropriate HIV counselling and testing | Exploratory descriptive qualitative research design | Semistructured interviews and focus groups | First Nations and Métis women (7) | Urban, Edmonton, Alberta | Major themes included life experiences, barriers to testing, the ideal HIV testing situation and dimensions of culturally appropriate HIV counselling and testing |

| Burns et al.Footnote 12 | To explore the experiences of Mi’kmaq women accessing prenatal care in rural Nova Scotia | Qualitative description and participatory action research | Semistructured interviews | First Nations women (4) | Rural, Nova Scotia | Issues related to access to prenatal care included difficulties organizing transportation and inequitable services among Mi’kmaq communities |

| Corosky and BlystadFootnote 22 | To generate youth-focussed evidence on experiences of sexual and reproductive health and rights relating to access to care | Piliriqatigiinniq Partnership Community Health Research Model | Semistructured interviews | Inuit community leaders (6), male youth (9) and female youth (10) | Remote, Arviat, Nunavut | Sexual and reproductive health and rights access barriers include distrust of support workers in the community, stigma/taboos and feelings of powerlessness |

| Fontaine et al.Footnote 13 | To investigate First Nations women’s experience with heart health | Decolonizing approach | Digital stories and storytelling | First Nations women (25) | Urban, Winnipeg, Manitoba | First Nations women’s heart health issues are linked to historical and social roots |

| Fraser and NadeauFootnote 14 | To explore Inuit experience with health and social services in a community of Nunavik | Case study (explanatory) | Semistructured interviews and field notes | Inuit elders (3), women (10) and man (1) | Remote, Nunavik, Quebec | Experiences with health and social services involved themes of trust, privacy and fear of the consequences of divulging information |

| GhoshFootnote 23 | To investigate the narratives of Indigenous people, providers and policy makers to inform existing Type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention strategies | Community participatory research | Narrative interviews | First Nations and Métis service users (27), providers (6) and policy makers (7) | Urban, Ottawa, Ontario | Urban Indigenous people’s diabetes prevention and management strategies must include the diversities in their historical, socioeconomic, spatial and legal contexts as well as their related entitlement to health services |

| Goodman et al.Footnote 15 | To explore how multiple forms of discrimination and oppression shape the health care experiences of Indigenous people living in a marginalized community | Indigenous research method | Talking circles and field notes | Indigenous men (18) and women (12) (did not specify participants’ Indigenous groups) | Urban, Vancouver, British Columbia | Health care professionals must allocate more time in understanding structural and historical factors that impact Indigenous patients’ disparities and personal attitudes |

| GormanFootnote 34 | To explore Indigenous women’s experiences with HIV/ AIDS | Exploratory phenomenology | Semistructured interviews | First Nations women (16) | Urban, Toronto, Ontario | Participants demonstrated resilience despite the insurmountable challenges they faced living with HIV/AIDS |

| HaydenFootnote 33 | To explore how people with diabetes in a small, isolated First Nations community and their health care providers regard the care they receive | Ethnographic collaborative research framework | Semistructured interviews and participant observations | First Nations women (6) and men (3) as well as key informants (8), including family members of participants, health care providers, and health care administrators | Remote and urban, Manitoba | Sharing patient knowledge of diabetes care with health care providers and removing institutional barriers to care may improve diabetes care and have a positive effect on diabetes outcomes |

| Howard et al.Footnote 39 | To describe rural cancer survivor experiences accessing medical and supportive care postcancer treatment | Mixed methods | Focus groups and questionnaires | First Nations women (7) and men (4) as well as non-Indigenous women (34) and men (7) | Rural and remote, British Columbia | Inaccessibility of supportive postcancer care can be attributed to financial constraint and geographical location |

| Howell-JonesFootnote 28 | To elicit descriptions of successful counselling partnerships between Indigenous clients and non-Indigenous mainstream mental health workers | Indigenous research method and narrative research | Semistructured interviews and field notes | First Nations women (4) and men (3) | Urban, Vancouver, British Columbia | A major defining factor for good counselling encounters is the counselling relationship’s ability to assist each client in understanding their aboriginality |

| Jacklin et al.Footnote 35 | To examine the health care experiences of Indigenous people with type 2 diabetes. | Phenomenology | Semistructured sequential focus groups | First Nations and Métis women (20) and men (12) | Urban and rural Alberta, urban and remote Ontario and rural British Columbia | Findings categorized Indigenous experience into 4 themes: the colonial legacy of health care, the perpetuation of inequities, structural barriers to care, and the role of health care relationships in mitigating harm |

| MacDonald et al.Footnote 24 | To explore women’s experiences with Pap screening in two rural Mi’kmaq communities | Community-based participatory action research design and Indigenous principles | Talking circles, semistructured interviews and field notes | First Nations women (16) | Remote, eastern Canada | Results outlined the need for health care providers to understand the uniqueness of each woman’s experiences with Pap screening. Additional emphasis was made to understand the impact of historical trauma, interpersonal violence and trauma-informed care for Indigenous people |

| Monchalin et al.Footnote 30 | To investigate Métis women’s perspectives on identity and their experiences with health services in Toronto | Indigenous methodology | Semistructured interviews | Métis women (11) | Urban, Toronto, Ontario | Findings show multitude of barriers for Métis women when accessing health and social services in Toronto. Practical solutions to develop culturally specific care were also explored |

| MonchalinFootnote 29 | To explore Métis women’s experiences of racism and discrimination when accessing and working within health and social services | Indigenous methodology and feminist theory | Semistructured interviews and field notes | Métis women (11) | Urban, Toronto, Ontario | Métis women experienced racial discrimination, e.g. witnessing, absorbing and facing racism, as well as lateral violence when accessing Indigenous-specific services |

| OelkeFootnote 25 | To understand the processes and structures required to support primary health care services for the urban Indigenous population | Ethnography, complex adaptive systems, participatory action research and case study | Meeting notes, individual and group interviews, and participant observation | First Nations and Métis service users (158) | Urban, Calgary, Alberta | Findings outlined key gaps: lack of access, collaboration amongst organizations coordination, and service gaps (e.g. prevention, promotion, mental health, children, and youth) |

| Russell and de LeeuwFootnote 26 | To identify challenges and barriers to Indigenous women accessing sexual health care services related to human papillomavirus and cervical cancer screening | Community-based participatory research, and feminist and antiracist methodologies | Interviews, open-ended questionnaires, and arts-based expressions | Métis women (22) | Remote, British Columbia | Experiences of gendered victimization, feelings of (dis)empowerment, life circumstances and lack of awareness were the four major themes that impacted Indigenous women’s access to sexual health care services |

| Tait NeufeldFootnote 31 | To explore Indigenous women’s experience; understanding the causes, course, treatment, onset, pathophysiology and prevention of gestational diabetes | Indigenous research exploratory | Semistructured interviews | First Nations and Métis women (29) and health care provider and community representatives (25) | Urban, Winnipeg, Canada | Limited access and quality of prenatal care as well as diabetes education were emphasized by the participants |

| Varcoe et al.Footnote 27 | To understand rural Indigenous women’s experiences of maternity care and factors shaping those experiences | Critical ethnographic approach and participatory framework | Participant observations, interviews and focus groups | First Nations women (125) and community leaders (9) | Remote, British Columbia | Participants explained their experiences with maternity care was linked with diminishing local maternity care choices, racism, and challenging economic circumstances |

Synthesized findings

Table 4 presents an overview of the individual findings of our review. Three major synthesized findings emerged from these, pertaining to our first and second research questions, and another one arose for the third research question. Table 5 is a summary of findings containing each synthesized finding’s level of dependability and credibility, as well as ConQual score (which rates confidence in the quality of evidence from reviews of qualitative research) to help their evaluation and integration into education, practice and policy.

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized findings |

|---|---|---|

| Receiving exceptional care (U) | Felt safe and secure, similar to being treated as family | Certain experiences of Indigenous people when receiving primary health care services were considered supportive and respectful |

| Relationship (C) | ||

| Dealing with diabetes (U) | ||

| Not all women had concerns about confidentiality or privacy (U) | ||

| The role of the health care relationship in mitigating harm (U) | Felt listened to and able to express themselves freely without judgment | |

| Collaborative and continuous care (U) | ||

| Importance of taking the time to engage (U) | ||

| Actively participating in health care decisions (U) | Health care providers were supportive, always accessible and provided as much time as needed to address all concerns | |

| Professional support (U) | ||

| Positive comments to local doctor (U) | ||

| Affirmation of personal and cultural identity (U) | Health care providers demonstrated respect to the client and their family and cultural identity | |

| Providing culturally safe care (U) | ||

| Engagement (C) | ||

| “I thought the world was a bad place” (C) | ||

| Positive relations (U) | ||

| Reluctance to seek care (U) | Did not receive adequate and quality primary health care due to negative stereotypes towards Indigenous people | Indigenous people experienced various forms of discrimination and maltreatment that most often resulted in them not receiving adequate and quality primary health care; thus, many adopted coping strategies to face such challenges |

| Discrimination as a threat to ongoing medication access (C) | ||

| Dismissal by health care providers (U) | ||

| Racist stereotypes (U) | ||

| Dissatisfaction with services (U) | ||

| Consequences of multiple stigmatized identities (U) | ||

| Additional beliefs swayed decisions to prescribe analgesics (U) | ||

| Lack of empathy (U) | ||

| Equitable care (U) | ||

| Prejudicial and judgmental views (U) | ||

| Examples of racism from participants (U) | ||

| Experiences with racism (U) | Subjected to discriminatory behaviours | |

| Questioned on two occasions in a row regarding her NativeFootnote a identity (U) | ||

| Passing as White (U) | ||

| Marginalization from the mainstream (U) | ||

| Situations of vulnerability (U) | ||

| Racist comments (U) | ||

| Notions of racial superiority (U) | ||

| Perpetuation of inequities (U) | ||

| Importance of building meaningful, trusting and respectful relationships (U) | ||

| Not welcoming (U) | ||

| Racism (U) | ||

| Looked down their noses at people (U) | ||

| Insensitivity (U) | Health care providers demonstrated judgmental attitudes and lack of compassion | |

| Being judged (U) | ||

| Compassion missing in action (U) | ||

| Being told in an inhumane manner about her diagnosis (U) | ||

| Presence of the physician’s religious values (U) | ||

| Short clinical interactions (U) | ||

| Victimization and discomfort (U) | ||

| Felt her needs were not being met or her voice heard (U) | Felt ignored and needs disregarded | |

| Felt being forced to leave her community (U) | ||

| What they wanted and needed was overridden (U) | ||

| Disregard for personal circumstances (U) | ||

| Delays in accessing care (U) | Health care providers have inadequate knowledge and/or expertise | |

| Knowing a client’s background (U) | ||

| Unknowledgeable physician (U) | ||

| Ought to consider the context of the individuals, families and communities (U) | ||

| Negative experiences with Indigenous-specific services (U) | Adopted some coping strategies to face discriminatory and negative treatment | |

| Transforming oneself to gain credibility (U) | ||

| Fear in divulging (U) | ||

| Fear of discrimination (U) | ||

| Feeling of unfairness (U) | ||

| Benefits of not having to identify herself as an AboriginalFootnote a person (U) | ||

| Mitigating of discriminatory health care practices (U) | ||

| Overmedication (U) | ||

| Issues with trusting health care providers (U) | ||

| Had waited so long that their symptoms were severe (U) | ||

| Lack of trust and female doctors (U) | ||

| Discomfort with her physician (U) | ||

| Reluctant to seek specialist-level help (U) | ||

| Distrust of the local health care provider (U) | ||

| Lack of confidentiality (U) | ||

| Perceived lack of anonymity (U) | ||

| Invasion of privacy (U) | ||

| Lack of confidentiality (U) | ||

| Confidentiality and privacy issues (U) | ||

| Trust in fly-in health care provider (U) | ||

| Lack of communication between health care providers on- and off-reserve (U) | Limited to absent continuity of care | Issues related to the primary health care system’s structure and practices led Indigenous people to experience inaccessible and incomplete care |

| Attending a walk-in clinic impacted the continuity of care received (U) | ||

| Transient nature of the population and the ability to have a need addressed immediately (U) | ||

| Development of a positive, long-term relationship with a health provider (U) | ||

| Transiency of support personnel (U) | ||

| Structural barriers to care (U) | ||

| Threatened continuity of care (U) | ||

| Physician shortages (U) | ||

| Revolving door (U) | ||

| Travelling the distance (U) | Experienced inaccessible care | |

| Lack of health care services (U) | ||

| Lack of appropriate resources (U) | ||

| Could not depend on medical care (U) | ||

| Gaps in primary health care services for children and youth (U) | ||

| Lack of mental health services (U) | ||

| The work required by AboriginalFootnote a people to find and attend AboriginalFootnote a-specific services (U) | ||

| More AboriginalFootnote a health service providers (U) | Constant time constraints | |

| Short physician visits (U) | ||

| Race to fit as many patients (U) | ||

| Time constraints of physicians (U) | ||

| Long waiting times (U) | ||

| Not fully understanding (U) | Health care providers exhibit lack of communication and health teaching | |

| Gaps between expectation and offered services (U) | ||

| Feeling lost (U) | ||

| Very little understanding (U) | ||

| Lack of support (U) | ||

| Lack of time to educate (U) | ||

| Limited number of services in health promotion (U) | ||

| Health promotion services (U) | ||

| Gaps in health promotion services (U) | ||

| Funding and services were linked to White problems (U) | ||

| Skepticism towards health care and outsiders (U) | ||

| Relationship building (U) | Health care providers need to demonstrate more empathy | Indigenous patients recommended that greater emphasis be placed on culturally sensitive empathic care, recruitment of Indigenous health care providers, accessibility and health teaching and promotion |

| Appropriate disclosure (U) | ||

| Need to develop good relationship (U) | ||

| Providing choices (U) | ||

| HIV testing process (U) | ||

| Lack of confidentiality (U) | ||

| HIV testing (U) | Integration of culturally sensitive care is paramount | |

| General lack of respect (U) | ||

| Community engagement (U) | ||

| Be aware of the history (U) | ||

| Community mobilization (U) | ||

| More visible spaces (U) | ||

| Importance of the interior design (U) | ||

| Métis-specific and/or -informed service space (U) | ||

| Skepticism towards health care and outsiders (U) | Advocating for more recruitment of Indigenous health care providers and staff | |

| Lack of cultural knowledge and awareness (U) | ||

| Need for NativeFootnote a staff (U) | ||

| More AboriginalFootnote a doctors (U) | ||

| Travelling the distance (U) | High need for accessible primary health care |

|

| Physician shortage (U) | ||

| Importance of having a family physician (U) | ||

| Gaps between expectation and offered services (U) | More emphasis on health teaching and promotion | |

| Assistance from nurse practitioners (U) | ||

| Gaps in health promotion services (U) | ||

| Feeling lost (U) | ||

| Total findings = 130 | Total categories = 19 | |

| Synthesized finding | Type of research | Dependability | Credibility | ConQual score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Certain experiences of Indigenous people when receiving primary health care services were considered supportive and respectful | Qualitative | High | High | High |

| 2. | Indigenous people experienced various forms of discrimination and maltreatment that most often resulted in them not receiving adequate and quality primary health care; thus, many adopted coping strategies to face such challenges | Qualitative | High | High | High |

| 3. | Issues related to the primary health care system’s structure and practices led Indigenous people to experience inaccessible and incomplete care | Qualitative | High | High | High |

| 4. | Indigenous patients recommended that greater emphasis must be placed on culturally sensitive empathic care, recruitment of Indigenous health care providers, accessibility and health teaching and promotion | Qualitative | High | High | High |

Synthesized finding one: supportive and respectful experiences

Synthesized finding one demonstrates that certain experiences of Indigenous people when receiving PHC were considered supportive and respectful. This metasynthesis was developed from four categories that included 15 findings. Some First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants expressed that they had supportive and respectful encounters with PHC providers, as they felt safe, secure, listened to and freely able to express themselves without judgment. This finding was affirmed by one of the First Nations and Métis participants living in an urban location as she described her prenatal care: “My G.P. is just a fantastic doctor because he sits there and actually listens to his patients. He respects that they know as much about what’s going on with their body as he probably does, if not more.”Footnote 31,p 165 Another First Nations woman residing in a remote community echoed this positive experience:

When my husband died, my [family] doctor phoned me to tell me to come in to talk with him and see if I was okay and talk about things that happened … and he explained it to me really softly; things like this happen. He was really caring. And that was the best thing that ever happened to me was him phoning me on his own to tell me that.Footnote 32,p.140

Participants also greatly appreciated when PHC providers were supportive, accessible and offered as much time as needed to address all of their concerns; similar experiences were described by those residing in urban, rural and remote areas. Having access to dependable information and providers made a significant difference for many of the participants. Many First Nations women in rural communities said that their community health nurses were “always there” to assist them with their health needs.Footnote 12

Moreover, Indigenous participants from urban, rural and remote locations valued health care providers demonstrating respect towards them, their family and their cultural identity. Providers were expected to exhibit culturally sensitive care and to have had training and to possess knowledge about Indigenous history, traditions, customs and challenges. When these qualities were present, PHC providers were perceived to be more helpful and genuine. Overall, across all settings—urban, remote and rural—instances of supportive and respectful PHC were experienced by First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants.

Synthesized finding two: discriminatory attitudes and maltreatment

Synthesized finding two reveals that Indigenous people experienced various forms of discrimination and maltreatment that most often resulted in them not receiving adequate and quality primary health care; thus, many adopted strategies to cope with such challenges. Six categories and 58 findings were represented in this metasynthesis.

There were numerous accounts in which participants shared their experiences of health care providers making comments or exhibiting behaviours based on discrimination. First Nations, Métis and Inuit patients in urban and rural or remote areas were immediately assumed to have tobacco and drug addiction, to be intoxicated by alcohol, to have abusive partners, to mistreat their children, or any combination of these, without any actual justification or evidence of such claims.Footnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 25Footnote 34Footnote 38 As reported by an aggravated Inuit participant from a remote community, “I arrived at the clinic and the first thing the doctor asked me is if I’m a smoker. Is that normal? It’s as if she assumed that because I’m Inuit I’m a smoker. I don’t think that is fair.”Footnote 14,p.293 A First Nations woman in an urban setting also commented, “Oh I wouldn’t get the proper care if I needed it, like if I was in pain. They thought I’d be there just to get high.”Footnote 34,p.122

These negative stereotypes automatically formed the basis of the care that Indigenous people received even though they did not necessarily apply to the specific situation of each patient. Consequently, these patients were generally dismissed, turned away and unable to receive the proper medical care they required, leading to severe complications or even death.Footnote 32

Such situations were experienced in urban, rural and remote locations. As reported by a participant in Goodman et al.:

I reached out on my right side and it really hurt. I went to a DTES [Downtown Eastside] clinic to the doctor and she told me to walk it off. I went to sleep and woke up and thought I was dying—big pain in my chest. I collapsed a lung. I think she thought I wanted painkillers, but I was really hurt.Footnote 15,p.90

Another First Nations participant reported in Fontaine et al.:

I lost [a family member]. He did drink a lot. And anyway, he got sick and every time he went to the Nursing Station, the nurse in charge there told him, he said, “Oh, you have a severe hangover,” without checking him. And he went about three, I know three times for sure, whether the fourth time, I can’t remember. But anyway, they kept chasing him home, “There’s nothing wrong with you. You’re just ... quit drinking, get, you’re ... hung over,” you know. Anyway, he died one night in ... his home.Footnote 13,p.5

Besides the deliberate omission of quality care, some Indigenous patients also sensed that certain PHC providers had discriminatory attitudes towards Indigenous people. In some cases, as soon as First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants from both urban and rural or remote locations entered a clinic, they instantly felt unwelcomed and judged, based on how the health providers and staff looked at and talked to them. This was further extended in their subsequent interactions, as explained by one frustrated participant in Goodman et al.:

So [the nurse] showed me how to [inject], but she was so mean about it. She was not accommodating. She said I should know how to do it myself. They treated me like crap, and I know it was because I was Native. We all know because of the look—there’s a look. When you need the medical care, we put up with it. We shouldn’t have to. We bleed the same way, we birth the same way. We have no choice …Footnote 15,p.89

Some participants in urban as well as rural or remote areas thought that the negative attitudes and judgments of PHC providers may have stemmed from their lack of understanding or disregard for Indigenous life experiences, history, background and socioeconomic and political circumstances,Footnote 23Footnote 25Footnote 37 but this was particularly emphasized by individuals living in rural or remote communities. There were instances in which First Nations women living on-reserve, who were required to travel to the city due to the unavailability of specialized services or diagnostic tools in their communities, were constantly fined for being late or missing their appointments in the city, even though the primary reasons for missing the appointments were that they were not able to afford a phone, or that there were traffic delays resulting from travelling a long distance.Footnote 32 As Browne and Fiske reported, “The embarrassment associated with being late or with being asked to pay the cancellation fine when they lacked the money shaped women’s experiences and left women with the sense that they were being blamed for circumstances beyond their control.”Footnote 32,p.138

As a result of these various negative interactions with PHC providers and the health care system, numerous Indigenous patients learned to cope by deciding not to disclose their cultural identity and medical history, presenting themselves to look more credible, or simply avoiding seeking care. Certain participants in Goodman et al.,Footnote 15 Monchalin et al.Footnote 30 and OelkeFootnote 25 divulged having omitted sharing their Indigenous background and certain aspects of their medical history to PHC providers, as they believed that this information would not be beneficial for their care, and worse, might only lead to discriminatory acts. Others chose to dress or behave differently in front of PHC providers to gain respect.Footnote 32 Indeed, one First Nations participant living in a remote community elaborated in Browne and Fiske:

It seemed like any time I go to a doctor I would have to be well dressed. I have to be on my best behaviour and talking and I have to sound educated to get any kind of respect…. If I was sicker than a dog and if I didn’t want to talk and I didn’t care how I sounded or whatever, I’d get treated … like lower than low. But if I was dressed appropriately and spoke really well, like I usually do, then I’d get treated differently…. But why do I have to try harder to get any kind of respect? You know, why do I have to explain?Footnote 32,p.135

In certain cases, Indigenous patients delayed seeking care as long as possible to prevent being subjected to traumatic and discriminatory experiences.Footnote 15Footnote 25 They sought health care only when their illness or symptoms had become serious, and they were left with no choice.Footnote 15Footnote 25 Many participants from both urban and rural or remote regions admitted to distrusting PHC providers.Footnote 13Footnote 24Footnote 26Footnote 34 However, Inuit and First Nations patients residing in rural or remote communities expressed significant concerns about whether providers were adequately protecting their privacy and confidentiality.Footnote 14Footnote 22Footnote 24

When comparing the PHC experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants in urban and rural or remote settings, we found very limited differences. As demonstrated above, similar to Indigenous patients living in urban areas, rural or remote participants also faced discriminatory attitudes and dismissive and judgmental care, forcing them to develop strategies for coping with such maltreatment. One particular geographical difference, however, was the fear of privacy and confidentiality breach. Although one participant in the study by Bucharski et al.,Footnote 37 which included First Nations and Métis women in an urban setting, expressed their concern about privacy and confidentiality, multiple First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants in rural or remote locations highlighted this fear. This concern may be more significant for residents of close-knit, small communities, as are often found in rural or remote locations. For these participants, PHC providers who were not considered “locals” were at times preferred, since they did not know anyone from the community and/or they would only be temporarily working in the community.Footnote 14

Synthesized finding three: structural and practice issues

Synthesized finding three highlights issues related to the PHC system’s structure and practices that led Indigenous people to experience inaccessible and incomplete care. Four categories and 32 findings formed the basis of this metasynthesis.

Our review found that major shortages of PHC providers existed across Canada. As a result, the Indigenous patients in the studies we reviewed who lived in both urban and rural or remote settings experienced lack of continuity of care, inaccessibility, short visits and inadequate health teaching and promotion. Many First Nations and Métis people who lived in cities did not have a family doctor; hence, they most often opted to visit walk-in clinics where various physicians rotate to cover the hours, and patients did not necessarily see the same physician during all their visits.Footnote 25Footnote 35 Establishing a therapeutic physician–patient relationship may be impossible in such brief encounters. This issue was even more problematic in rural and remote communities, where the transiency of PHC providers is prominent, and their recruitment and retention are challenging.Footnote 22Footnote 27Footnote 32Footnote 35 Some First Nations and Métis participants in Jacklin et al. “felt that once doctors gain experience, ‘they want more money here, and if they don’t get it, they quit and move on.’”Footnote 35,pp.109-110

Additionally, Inuit and First Nations patients who lived in rural or remote regions could not easily access certain medical care and preventive services.Footnote 12Footnote 14Footnote 34Footnote 39 Minimal or no time was dedicated to health teaching or promotion, especially in a manner that was culturally appropriate.Footnote 14 Indeed, as one of the Inuit participants in Fraser and Nadeau confirmed,

If I was diabetic, for example, I would need information, what can I eat and what can I not. My Grandmother, they did not give her any ideas what she can eat and what she cannot do…. They need to have examples, recipes, and take less salt and sugar. And, how to make bannock. Like when you make spaghetti, use the whole wheat spaghetti. All those nutrition information. People need encouragement.Footnote 14,p.292

Though health promotion materials, such as brochures and videos, may be available, First Nations and Métis participants in OekleFootnote 25 further highlighted the absence of culturally adapted verbal and visual teachings. One participant reported, “The prevention services that are available for First Nations are what’s ever in the hype for the White crowd. So if it’s a White problem, a White prevention problem, those are what’s available.”Footnote 25,p.147 Also, visits of First Nations and Métis patients with PHC providers in metropolitan, rural and remote areas were commonly described as “rushed,” there being “never enough time,” “a race to fit as much patients as possible” and “similar to an assembly line.”Footnote 23Footnote 31Footnote 33Footnote 35 For this reason, many felt that their needs and concerns were not entirely addressed.Footnote 33Footnote 35

In regard to other geographical considerations, despite the differences of PHC services offered in urban and rural or remote settings, PHC structure and practices in all three settings similarly affected the accessibility of care experienced by Indigenous people. For instance, in rural or remote locations, hospitals and specialized care did not necessarily exist. PHC providers within these settings therefore generally assumed an expanded role to offer additional services to community; however, this had its limits, as certain diagnostic tools and specialists were only available in the major cities.Footnote 12Footnote 14 In urban areas, First Nations and Métis people encountered comparable accessibility challenges, including the lack of PHC services for children and youth, and mental health support.Footnote 25

Synthesized finding four: recommendations

Synthesized finding four focussed on Indigenous patients’ recommendations for greater emphasis on culturally sensitive empathic care, recruitment of Indigenous PHC providers, accessibility and health teaching and promotion. This last metasynthesis was created from five categories and 25 findings.

Numerous First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants emphasized the importance of cultural sensitivity and empathy, indicating that it is paramount that all PHC providers and staff are familiar with Indigenous history and practices.Footnote 34Footnote 33Footnote 37 They expressed the idea that only through education would providers and staff start to be empathic and respectful towards Indigenous peoples.Footnote 13Footnote 37 Besides provider–patient interactions, cultural sensitivity could also be conveyed in the design of the physical spaces where PHC services are delivered. Participants suggested that incorporating Indigenous symbols or art onto the walls of the clinic could provide a more welcoming environment for patients.Footnote 29

Participants also suggested that greater funding should be allocated to recruiting PHC providers and staff, particularly those with an Indigenous background.Footnote 12Footnote 23Footnote 25Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36 As one participant explained, “I just think they need to have more Native doctors and nurses ... for Aboriginal peoples to feel comfortable ... or people that are experienced in Aboriginal culture. It would be nice to have our own Aboriginal people running it.”Footnote 23,p.83

Furthermore, there is a great need to enhance health teaching and promotion in all PHC settings.Footnote 14Footnote 25Footnote 33Footnote 35Health teaching and promotion must also appropriately consider the cultural context and challenges of Indigenous peoples for these to be perceived as beneficial.Footnote 25

Lastly, when geographical differences between urban and rural or remote settings were examined, minor nuances were noticed. Although recommendations for culturally sensitive empathic care, recruitment of Indigenous PHC providers, improved accessibility and health education were common across First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants from urban and rural or remote regions, certain recommendations were given more emphasis within one particular setting. For example, the need for culturally sensitive empathic care and recruitment of Indigenous PHC providers was pointed out more by First Nations and Métis participants residing in the urban areas than those in rural or remote communities, who mostly emphasized suggestions for accessibility and health teaching and promotion.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative systematic review was to explore Indigenous people’s experiences in Canada with PHC services, determine urban versus rural or remote differences and identify recommendations for quality improvement. Three major synthesized findings were revealed—supportive and respectful experiences, discriminatory attitudes and systemic challenges faced by Indigenous patients—along with one synthesized finding on their specific recommendations.

The conflicting PHC experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants, wherein instances of supportive and respectful interactions were revealed while discriminatory attitudes and systemic barriers simultaneously exist, attest to the multifaceted complexity of the situation. The interplay between systemic, institutional and interpersonal factors may have influenced these conflicting PHC experiences. The historical and intergenerational traumas of colonization, forced assimilation and residential schools continue to leave a lasting effect on the health care system, contributing to systemic discrimination that is ingrained within Canada’s health care policies and structures. The policies and structures of the health care system often reflect historical biases and stereotypes rooted in the colonial era and the legacy of residential schools. These biases manifest in policies that fail to adequately address the unique health challenges faced by Indigenous populations, resulting in unequal access to health care resources and services.

Additionally, there is limited Indigenous representation in health care policy making and leadership. This absence of perspective leads to a health care system that often does not fully understand or prioritize the health needs of Indigenous communities, further alienating them from the system. Although at the institutional level some organizations have invested in cultural sensitivity and antiracism training for health care providers, which can result in more positive experiences for Indigenous patients, individual health care providers within these organizations may still hold conscious or unconscious biases against Indigenous peoples, which can negatively affect the quality of care received.

In sum, the disparity in PHC experiences among Indigenous communities arises from a multifaceted set of conditions that operate at various levels. While systemic issues such as discrimination and racism can lead to negative experiences, targeted interventions and personal relationships can sometimes result in positive interactions. Therefore, efforts to improve PHC health care for Indigenous people in Canada need to be comprehensive, multipronged and culturally sensitive to effectively address this complex situation.

Indigenous people in this review valued safe, accessible and respectful care, aligning with their basic human rights as outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 41 and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s calls to action.Footnote 42 Canadian governments and other sectors are nowhere near fulfilling these calls to action,Footnote 43 particularly in the domain of health. At the current pace, completing all the calls to action will take until 2065.Footnote 43 This shortcoming is particularly evident in our review; significant findings from most of the included articles illustrated considerable discrimination, racism and maltreatment of Indigenous peoples. Synthesized findings two and three echoed these unjust experiences that Indigenous patients had to face (and potentially continue to face).

The discrimination and racism faced by the Indigenous people in this review negatively affected their overall health and well-being. While accessing PHC, they often felt uncomfortable and judged due to providers’ negative stereotypes of Indigenous people. These attitudes, along with dismissive care and maltreatment, caused Indigenous people in the studies reviewed to avoid seeking care, exacerbating medical symptoms and potentially leading to severe complications or death.

Similar findings in other studies show that past experiences of discrimination and racism made Indigenous people more likely to avoid medical assistance, contributing to unfavourable health outcomes.Footnote 3Footnote 44 The life expectancy of Indigenous people is five years less than that of the general population.Footnote 3 Additionally, the prevalence of infectious diseases, chronic conditions and mental health disorders as well as infant mortality rates among Indigenous populations in Canada are significantly higher compared to non-Indigenous Canadians.Footnote 3 These disparities were further exacerbated during the pandemic, particularly for Indigenous people in rural and remote communities, who contracted COVID-19 at rates three to four times the national average—rising to seven and eight times in some weeks.Footnote 45

In this review, First Nations, Métis and Inuit participants living in rural or remote locations were also more likely to experience maltreatment and dismissive care as well as issues with privacy, confidentiality and accessibility.Footnote 1Footnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 22Footnote 24Footnote 34 These particular issues could be attributed to the close-knit nature of small communities and the structural barriers associated with the lack of health care infrastructure within these areas. Even though we identified 10 studies of rural and remote regions, there were still limited findings on Indigenous people’s PHC experiences in such regions, which prevented a deeper analysis of geographical considerations. The inclusion of participants from diverse geographical settings, however, adds another layer of complexity and richness to the findings, as it allows for a more nuanced understanding of how location may impact health care experiences. Hence, more research on PHC experiences of Indigenous peoples living in rural or remote communities is required to comprehensively understand the challenges they encounter.

Overall, the synthesized findings of this review emphasize the urgent need to address longstanding discrimination and racism, while also advocating for the implementation of sustainable changes to prevent further endangerment of Indigenous lives in Canada.

Recommendations

Indigenous patients have highlighted numerous problems with PHC services, leading to calls for changes in health care practice, structures and policy development. This includes emphasizing Indigenous culture in training, improving cross-cultural communication and prioritizing education to reduce negative experiences, all of which are in line with the TRC calls to action numbers 23 and 24.Footnote 42Footnote 46 Despite an increase in cultural competency and antiracism training,Footnote 47 there is still a need to increase the methodological rigour and standardization of such training, as well as to examine their long-term effects while stressing Indigenous community partnerships.Footnote 46Footnote 48 Health care providers should also practise some form of self-reflection, such as journalling or meditation, to examine personal biases.Footnote 49 This approach, aligned with cultural humility principles, teaches providers to defer to clients as experts in their own culture, creating a safer, nonjudgmental environment with the voices of Indigenous patients at its forefront.Footnote 49

However, the focus of change should not be solely on health care practice and providers. Systemic transformation, including more funding and support for Indigenous communities, must happen concurrently in order to establish meaningful traction towards better patient care. There is a nationwide shortage of Indigenous PHC providers and staff that requires immediate attention. As emphasized in the TRC calls to action, “We call upon all levels of government to increase the number of Aboriginal professionals working in the health-care field [and to] ensure the retention of Aboriginal health care providers in Aboriginal communities…”Footnote 42,p.164 These key actors are critical in all sectors of society, from frontline and academia to research and policy development.Footnote 49 At this point, the inclusion of Indigenous people across all sectors should be the norm, and not merely an afterthought.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first qualitative review exploring Indigenous people’s experiences with PHC services across Canada, serving as a valuable guide for policy makers and health care providers to identify target areas for improvement. Only by incorporating the voices of service users into health policies and interventions will the PHC and health care system as a whole deliver services that truly and meaningfully meet patients’ and communities’ needs. However, a limitation of qualitative review stems from the pooling of findings that are context-dependent, thus potentially reducing the emphasis on important contextual factors. Nevertheless, through our use of the chosen methodology (i.e. meta-aggregation), the traditions of qualitative research were maintained, preserving the context of each study and aggregating findings into a combined whole.Footnote 16 This strengthens the review’s findings, making them more appropriate for guiding policy makers and health care providers.

Conclusion