At-a-glance – Primary caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities or disorders in Canada: highlights from the 2018 General Social Survey – Caregiving and Care Receiving

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: May 2025

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Sarah Palmeter, MPH; Siobhan O’Donnell, MSc; Sienna Smith, MPH

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.45.5.04

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended Attribution

At-a-glance by Palmeter S et al. in the HPCDP Journal licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Author reference

Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence

Sarah Palmeter, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Email: sarah.palmeter@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Suggested citation

Palmeter S, O’Donnell S, Smith S. Primary caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities or disorders in Canada: highlights from the 2018 General Social Survey – Caregiving and Care Receiving. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2024;45(5):256-63. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.45.5.04

Abstract

Using data from the 2018 General Social Survey – Caregiving and Care Receiving, we examined the characteristics of caregivers of people with developmental disabilities or disorders (DD) and the impacts of caregiving on these caregivers. The proportion of DD caregivers with optimal general and mental health was smaller than the proportion of non-caregivers. About two-thirds of DD caregivers reported feeling worried or anxious, or tired and almost half reported unmet support needs. However, compared with caregivers of individuals with other conditions, a significantly higher proportion of DD caregivers described their caregiving experiences as rewarding.

Keywords: developmental disorders, developmental disabilities, General Social Survey, caregivers, neurodevelopmental disorders, population surveillance, surveys and questionnaires

Highlights

- Characteristics of caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities or disorders (“DD caregivers”) were compared with those of caregivers of individuals with other conditions and with those of non-caregivers.

- A smaller proportion of DD caregivers than non-caregivers reported optimal general and mental health.

- Many DD caregivers reported feeling worried or anxious, feeling tired and spending less time taking care of themselves due to their caregiving responsibilities.

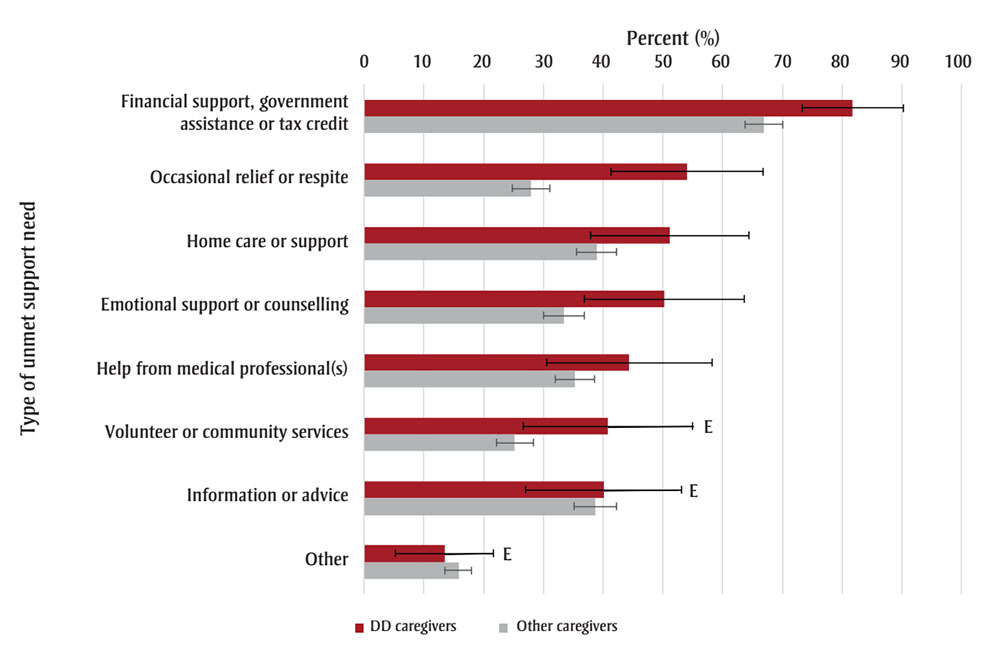

- Almost half of DD caregivers reported unmet support needs, particularly financial support, government assistance or tax credits, occasional relief or respite care, and home care or support.

- Despite these challenges, a significantly higher proportion of DD caregivers described their caregiving experiences as rewarding or very rewarding compared with other caregivers.

Introduction

Unpaid caregiving is increasingly common in Canada, driven by an aging population, the rising prevalence of disabilities and a growing emphasis on community- and home-based care.Footnote 1Footnote 2 In 2018, about one in four people aged 15 years and older provided unpaid care to a friend or family member with a long-term health condition, disability or age-related issue in Canada.Footnote 3

While all caregivers face unique challenges, those supporting individuals with developmental disabilities or disorders (DD) have distinct experiences. These caregivers (referred to as “DD caregivers”) often provide ongoing support that evolves throughout the care receiver’s lifespan.Footnote 4Footnote 5 Their roles are important and wide-ranging, impacting the lives of children, youth and adults with DD.Footnote 4Footnote 6Footnote 7

DD encompass a group of conditions characterized by differences in physical development, learning, language or behaviour, which can affect daily functioning.Footnote 8 DD become apparent early in life and last throughout a person’s life. Common examples include intellectual disabilities, autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Down syndrome and cerebral palsy.

Population-based studies in Canada have found that caregivers of children with DD report more health problems and poorer mental health than those caring for children without DD.Footnote 9Footnote 10 Population-based studies from other countries also report poorer health outcomes, mental health challenges, increased financial struggles and lower well-being among DD caregivers.Footnote 5Footnote 11

To better understand these aspects, we used data from the 2018 General Social Survey (GSS) – Caregiving and Care ReceivingFootnote 12 to examine the characteristics of caregivers of children, youth and adults with DD living in Canada and to describe the impacts of caregiving on caregivers.

Methods

Data source and study population

The GSS – Caregiving and Care Receiving is a national survey of people aged 15 years and older living in Canada’s 10 provinces.Footnote 12 The 2018 survey collected information on primary caregivers, that is, people who provided help or care to family members, friends or neighbours with a long-term health condition, physical or mental disability or aging-related problem in the past 12 months. Paid help or help provided on behalf of an organization were not within the scope of this survey.

Our study focus was on primary caregivers of people whose “main health condition or problem for which they have received help” was a “developmental disability or disorder.”Footnote 12

The full unweighted sample of the 2018 GSS was 20258, of whom 248 self-identified as DD caregivers, 7416 as caregivers of individuals with conditions other than DD (referred to as “other caregivers”) and 12594 as non-caregivers. About 1% of caregiver interviews and 2% of non-caregiver interviews were conducted by proxy when the respondent did not speak English or French or could not participate in the survey for health reasons.Footnote 12

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine DD caregivers’ and care receivers’ sociodemographic characteristics, the type of care provided, caregivers’ health status, the impacts of caregiving on caregivers, caregiver supports and unmet support needs.

All estimates were weighted to be representative of all non-institutionalized persons aged 15 years and older, living in the 10 provinces of Canada, using sample weights provided by Statistics Canada for this survey.Footnote 12 Bootstrap methods were used to calculate variance estimates, including 95% confidence intervals (CI) and coefficients of variation. The estimates for DD caregivers were compared with estimates for other caregivers or for GSS respondents who were not caregivers, where appropriate. The associated 95% CIs were also compared and non-overlapping 95% CIs were considered statistically significantly different.

Analyses were carried out using statistical package SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US).

Results

Based on data from the 2018 GSS, 4.5% (95% CI: 3.6%–5.3%) of caregivers provided care to a family member or friend with DD. DD were ranked as the seventh most common condition cared for, while aging or frailty (22.7%; 21.2%–24.3%), cancer (9.9%; 8.8%–10.9%) and mental illness (9.7%; 8.5%–11.0%) were the three most common in the survey (data not shown).

Sociodemographic characteristics

The mean age of DD caregivers at the time of the survey was 45.7 years, and 58.9% were female. About one-fifth identified as a visible minority, 55.7% had a postsecondary education and 59.1% were employed (Table 1).

| Variable | DD caregivers,Footnote a % (95% CI) |

Other caregivers,Footnote b % (95% CI) |

Non-caregivers,Footnote c % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Mean age, years | 45.7 (42.3–49.2) | 49.2 (48.4–49.9) | 46.1 (45.9–46.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 58.9 (48.6–69.2) | 53.8 (52.0–55.5) | 49.5 (48.9–50.1) |

| Male | 41.1 (30.8–51.4) | 46.2 (44.5–48.0) | 50.5 (49.9–51.1) |

| EthnicityFootnote d | |||

| Visible minority | 20.8 (12.3–29.2)Footnote E | 16.7 (15.0–18.4) | 25.0 (23.8–26.1) |

| Not visible minority | 79.2 (70.8–87.7) | 83.3 (81.6–85.0) | 75.0 (73.9–76.2) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| High school or less than high school | 44.3 (33.8–54.9) | 36.6 (34.7–38.5) | 42.2 (41.0–43.3) |

| Postsecondary | 55.7 (45.1–66.2) | 63.4 (61.5–65.3) | 57.8 (56.7–59.0) |

| Employment | |||

| Employed (worked or absent from a job in the previous week) | 59.1 (48.6–69.6) | 61.2 (59.5–63.0) | 61.3 (60.2–62.4) |

| Unemployed (did not have a job in the previous week) | 40.9 (30.4–51.4) | 38.8 (37.0–40.5) | 38.7 (37.6–39.8) |

| Mean age of care receiver, years | 22.5 (19.5–25.4) | 68.9 (68.0–69.8) | NA |

| Sex of care receiver | |||

| Female | 35.8 (26.0–45.6) | 63.3 (61.5–65.1) | NA |

| Male | 64.2 (54.4–74.0) | 36.7 (34.9–38.5) | NA |

| Relationship of care receiver to caregiver | |||

| Child of caregiver | 62.2 (52.8–71.7) | 5.5 (4.7–6.2) | NA |

| Sibling of caregiver | 20.8 (11.5–30.0)Footnote E | 4.7 (3.9–5.5) | NA |

| Grandchild of caregiver | 5.6 (2.4–8.8)Footnote E | Footnote F | NA |

| OtherFootnote e | 11.4 (6.4–16.4)Footnote E | 89.2 (88.1–90.4) | NA |

| Living situation | |||

| Caregiver living in same household as care receiver | 79.2 (72.3–86.1) | 33.6 (31.7–35.5) | NA |

| Caregiver and care receiver living in different households | 20.8 (13.9–27.7)Footnote E | 66.4 (64.5–68.3) | NA |

| Care provided | |||

| Care receiver has at least one other caregiver (paid or unpaid) | |||

| Yes | 83.9 (76.3–91.6) | 71.1 (69.3–73.0) | NA |

| No or don’t know | 16.1 (8.4–23.7)Footnote E | 28.9 (27.0–30.7) | NA |

| Mean hours of caregiving per week | 29.1 (22.7–35.5) | 13.4 (12.5–14.2) | NA |

| Help with transportation | |||

| Yes | 86.2 (79.1–93.3) | 72.7 (70.9–74.4) | NA |

| No | 13.8 (6.7–20.9)Footnote E | 27.3 (25.6–29.1) | NA |

| Help with meal preparation, meal clean-up, house cleaning, laundry or sewing | |||

| Yes | 80.0 (72.4–87.5) | 55.3 (53.5–57.1) | NA |

| No | 20.0 (12.5–27.6)Footnote E | 44.7 (42.9–46.5) | NA |

| Help with scheduling/coordinating care-related tasks | |||

| Yes | 60.5 (50.2–70.8) | 39.9 (38.2–41.7) | NA |

| No | 39.5 (29.2–49.8) | 60.1 (58.3–61.8) | NA |

| Help with personal care | |||

| Yes | 58.8 (49.0–68.6) | 27.7 (26.2–29.3) | NA |

| No | 41.2 (31.4–51.0) | 72.3 (70.7–73.8) | NA |

| Help with managing finances | |||

| Yes | 44.5 (34.9–54.2) | 32.0 (30.3–33.7) | NA |

| No | 55.5 (45.8–65.1) | 68.0 (66.3–69.7) | NA |

| Help with medical treatments/procedures | |||

| Yes | 37.5 (28.5–46.4) | 26.0 (24.5–27.5) | NA |

| No | 62.5 (53.6–71.5) | 74.0 (72.5–75.5) | NA |

| Health status | |||

| General health | |||

| Excellent/very good | 40.5 (30.7–50.4) | 48.5 (46.6–50.3) | 58.6 (57.3–59.9) |

| Good | 41.9 (32.0–51.8) | 34.4 (32.7–36.1) | 30.1 (28.9–31.3) |

| Fair/poor | 17.5 (11.1–24.0)Footnote E | 17.1 (15.8–18.5) | 11.3 (10.6–12.1) |

| Mental health | |||

| Excellent/very good | 45.7 (36.1–55.3) | 51.9 (50.1–53.7) | 64.1 (62.7–65.4) |

| Good | 32.8 (24.1–41.5) | 32.5 (30.8–34.2) | 26.5 (25.3–27.7) |

| Fair/poor | 21.5 (13.0–29.9)Footnote E | 15.6 (14.2–17.0) | 9.4 (8.6–10.2) |

| Stress | |||

| Most days not at all/not very stressful | 25.8 (16.1–35.5)Footnote E | 28.1 (26.5–29.6) | 37.4 (36.2–38.6) |

| Most days a bit stressful | 46.9 (37.2–56.5) | 47.2 (45.4–49.0) | 42.4 (41.2–43.6) |

| Most days quite a bit/extremely stressful | 27.3 (19.4–35.2) | 24.7 (23.2–26.3) | 20.1 (19.1–21.2) |

| Life satisfactionFootnote f | |||

| Satisfied/very satisfied | 77.2 (69.9–84.5) | 80.5 (79.0–82.0) | 86.9 (86.0–87.8) |

| Neither satisfied or dissatisfied | 15.0 (8.4–21.7)Footnote E | 10.2 (9.0–11.3) | 7.2 (6.6–7.9) |

| Very dissatisfied/dissatisfied | 7.8 (3.7–11.8)Footnote E | 9.3 (8.2–10.5) | 5.9 (5.2–6.5) |

| HappinessFootnote f | |||

| Happy and interested in life | 50.9 (40.6–61.1) | 58.4 (56.5–60.3) | 64.4 (63.2–65.7) |

| Somewhat happy | 42.1 (31.9–52.4) | 33.8 (31.9–35.7) | 29.9 (28.7–31.1) |

| Somewhat unhappy / unhappy with little interest in life / so unhappy life is not worthwhile | 7.0 (2.7–11.3)Footnote E | 7.8 (6.7–8.9) | 5.6 (5.1–6.2) |

| Impacts of caregivingFootnote g | |||

| Feel worried or anxiousFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 70.1 (59.0–81.2) | 62.5 (60.3–64.7) | NA |

| No | 29.9 (18.8–41.0)Footnote E | 37.5 (35.3–39.7) | NA |

| Feel tired | |||

| Yes | 68.0 (57.3–78.6) | 59.4 (57.2–61.7) | NA |

| No | 32.0 (21.4–42.7)Footnote E | 40.6 (38.3–42.8) | NA |

| Feel overwhelmedFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 57.8 (46.8–68.8) | 42.5 (40.3–44.7) | NA |

| No | 42.2 (31.2–53.2) | 57.5 (55.3–59.7) | NA |

| Experience disturbed sleepFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 48.6 (37.9–59.2) | 41.1 (38.8–43.3) | NA |

| No | 51.4 (40.8–62.1) | 58.9 (56.7–61.2) | NA |

| Feel short-tempered or irritableFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 45.3 (34.8–55.8) | 42.7 (40.5–44.9) | NA |

| No | 54.7 (44.2–65.2) | 57.3 (55.1–59.5) | NA |

| Feel depressedFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 28.7 (20.2–37.3) | 26.1 (24.3–28.0) | NA |

| No | 71.3 (62.7–79.8) | 73.9 (72.0–75.7) | NA |

| Feel lonely or isolatedFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 24.5 (16.3–32.7)Footnote E | 24.3 (22.5–26.2) | NA |

| No | 75.5 (67.3–83.7) | 75.7 (73.8–77.5) | NA |

| Experience loss of appetiteFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 15.6 (8.9–22.3)Footnote E | 13.8 (12.4–15.2) | NA |

| No | 84.4 (77.7–91.1) | 86.2 (84.8–87.6) | NA |

| Feel resentfulFootnote f | |||

| Yes | 15.1 (8.6–21.6)Footnote E | 25.2 (23.5–27.0) | NA |

| No | 84.9 (78.4–91.4) | 74.8 (73.0–76.5) | NA |

| How rewarding have caregiving experiences beenFootnote f | |||

| Very rewarding/rewarding | 68.3 (58.5–78.1) | 54.2 (52.0–56.5) | NA |

| Somewhat/not at all rewarding | 31.7 (21.9–41.5) | 45.8 (43.5–48.0) | NA |

| Spend less time relaxing or taking care of self due to caregiving | |||

| Yes | 67.0 (56.7–77.3) | 58.7 (56.4–61.0) | NA |

| No | 33.0 (22.7–43.3) | 41.3 (39.0–43.6) | NA |

| Supports and unmet support needs | |||

| Care receiver also received help from professionalsFootnote h | |||

| Yes | 73.9 (64.0–83.7) | 60.0 (58.0–62.1) | NA |

| No or don’t know | 26.1 (16.3–36.0)Footnote E | 40.0 (37.9–42.0) | NA |

| Caregiver received support in caregiving dutiesFootnote i | |||

| Yes | 87.4 (81.3–93.6) | 70.7 (69.1–72.2) | NA |

| No | 12.6 (6.4–18.7)Footnote E | 29.3 (27.8–30.9) | NA |

| Unmet support needsFootnote j | |||

| Yes | 46.8 (37.0–56.6) | 29.6 (27.8–31.5) | NA |

| No | 53.2 (43.4–63.0) | 70.4 (68.5–72.2) | NA |

The mean age of the care receivers with DD was 22.5 years (Table 1). Almost two-thirds were male (64.2%) and the children of the caregivers (62.2%) versus another relationship. More than three-quarters lived in the same household as the caregiver (79.2%) and had at least one other caregiver, paid or unpaid (83.9%). Compared with care receivers with other conditions, those with DD were significantly younger and significantly more likely to be male, children of the caregiver, living in the same household as the caregiver and have at least one other caregiver.

Care provided

DD caregivers provided an average of 29 hours of care per week (Table 1), most commonly help with transportation (86.2%); meal preparation, meal clean-up, house cleaning, laundry or sewing (80.0%); and scheduling or coordinating care-related tasks (60.5%). Compared with other caregivers, DD caregivers provided significantly more hours of care per week (29.1 vs. 13.4 hours) and were significantly more likely to provide each type of care.

Health status

Less than half of DD caregivers described their general health and mental health as excellent or very good (40.5% and 45.7%, respectively), and only one-quarter reported that most days were not at all or not very stressful (Table 1). However, more than three-quarters reported that they were satisfied or very satisfied with life (77.2%), and about half indicated that they were happy and interested in life (50.9%). Compared with non-caregivers, DD caregivers reported less optimal general and mental health, more stress, and less life satisfaction and happiness.

Impacts of caregiving

DD caregivers most commonly described feeling worried or anxious as a result of their caregiving responsibilities (70.1%); having rewarding or very rewarding caregiving experiences (68.3%); feeling tired as a result of their caregiving duties (68.0%); and spending less time relaxing or taking care of themselves due to their caregiving (67.0%) (Table 1). While other caregivers experienced similar impacts, a significantly higher proportion of DD caregivers reported feeling overwhelmed (57.8% vs. 42.5%). Conversely, a significantly smaller proportion of DD caregivers reported feeling resentful (15.1% vs. 25.2% for other caregivers), and a significantly higher proportion found caregiving to be very rewarding or rewarding (68.3% vs. 54.2% for other caregivers).

Supports and unmet support needs

Almost three-quarters (73.9%) of care receivers with DD who did not live in an institution also received help from professionals (i.e. paid workers or organizations), and most (87.4%) DD caregivers received some type of support to accommodate their caregiving duties (Table 1). Despite this, almost half (46.8%) of DD caregivers reported unmet support needs, with the most common being financial support, government assistance or tax credit, occasional relief or respite care, home care or support, and emotional support or counselling (Figure 1). Compared with other caregivers, a significantly higher proportion of DD caregivers received help from professionals and some type of support in their caregiving duties, yet still had unmet support needs (Table 1).

Figure 1 : Descriptive text

| Type of unmet support need | DD Caregivers – Percent (%) (95% confidence interval) | Non-DD Caregivers – Percent (%) (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial support, government assistance, or tax credit | 81.7 (73.3, 90.2) | 66.9 (63.7, 70.1) | |

| Occasional relief or respite | 54.1 (41.3, 66.8) | 28 (24.8, 31.1) | |

| Home care or support | 51.1 (37.9, 64.4) | 38.9 (35.6, 42.3) | |

| Emotional support or counselling | 50.2 (36.9, 63.6) | 33.5 (30, 36.9) | |

| Help from medical professional(s) | 44.4 (30.5, 58.3) | 35.3 (32, 38.6) | |

| Volunteer or community services | 40.8 (26.6, 55)Footnote E | 25.2 (22.1, 28.3) | |

| Information or advice | 40.1 (27, 53.1)Footnote E | 38.7 (35.1, 42.2) | |

| Other | 13.5 (5.3, 21.7)Footnote E | 15.8 (13.5, 18) | |

Source: 2018 General Social Survey – Caregiving and Care Receiving.Footnote 12

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DD, developmental disabilities or disorders.

Notes: Percentages and 95% CIs are based on weighted data. Error bars represent the associated 95% CIs, defined as an estimated range of values that is likely to include the true value 19 times out of 20. “DD caregivers” are caregivers of individuals with DD, and “other caregivers” are caregivers of individuals with conditions other than DD.

E Use with caution.

Discussion

This is the first study to use data from the GSS to report on the characteristics of DD caregivers in Canada and the impacts of their caregiving experiences. We found the proportion of DD caregivers with optimal health to be smaller than the proportion of non-caregivers with optimal health; more than two-thirds of DD caregivers felt worried or anxious and felt tired as a result of their caregiving roles. Almost half also reported various unmet support needs, with financial support, occasional relief or respite care, and home care or support the most common. Despite these challenges, many DD caregivers found their caregiving experiences rewarding.

Previous Canadian and international studies have also shown that caregiving for individuals with DD can negatively affect caregivers’ mental and physical health, with effects varying with the caregiver, care receiver, family characteristics and circumstances such as caregiver income, the care receiver’s age and the number of care receivers with disabilities being looked after by each caregiver, and barriers to accessing services and supports.Footnote 5Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 15Footnote 16 We found that DD caregivers were more likely than other caregivers to care for their own children and for younger individuals, to live in the same household as the care recipient and to have the support of at least one additional caregiver. DD caregivers also provided more hours of care per week than other caregivers. These differences in demographics and circumstances may have important implications on the experience and impacts of caregiving.Footnote 15 However, exploring the specific factors associated with the effects of caregiving was beyond the scope of this study.

Prior investigations have identified unmet support needs for both individuals with DD and their caregivers, with inadequate support partly explaining why families are often negatively affected as a result of their children’s disabilities.Footnote 17Footnote 18 A recent survey of caregivers found the most frequently reported support needs to be related to mental health and finances, with variations across sociodemographic groups.Footnote 1 Our study also found that financial support was the most commonly reported unmet need, followed by occasional relief or respite care, home care or support, as well as emotional support or counselling. Financial creditsFootnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21 and organizations that offer education and training, peer support, advocacy and counselling opportunities for caregivers are available in Canada, although eligibility and availability vary depending on the caregiver’s situation.

Although research often focuses on the burdens of caregiving, previous studies have shown that parents of children with DD report positive aspects of their caregiving experiences, seeing their child as a source of happiness, personal strength and growth, and family closeness.Footnote 22Footnote 23 These perceptions, which mirror our findings of more rewarding caregiving experiences among DD caregivers, have been linked to caregivers’ healthy coping strategies and access to caregiving supports.Footnote 23

Strengths and limitations

This study used data from the 2018 GSS, a large, population-based survey with weighted estimates representative of the target population; however, some limitations are worth noting. First, the survey did not include the territories, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study sample size prevented us from disaggregating some sociodemographic characteristics such as ethnicity and Indigeneity. Third, the survey did not capture specific types of DD; it was therefore not possible to examine the differential impacts of specific DD on caregivers’ experiences. Lastly, while non-overlapping CIs indicate significant differences, overlapping CIs do not necessarily imply a lack of difference. However, the use of this conservative approach minimizes drawing erroneous conclusions of significance. Further, the small sample of DD caregivers resulted in wider CIs, potentially limiting our ability to detect significant differences.

The findings from this study reflect the experiences of DD caregivers prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic, particularly early on, frequently exacerbated caregiving challenges through disruptions to routines, education, services or supports.Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28

Conclusion

Despite the negative impacts of caregiving, such as worse general and mental health, a higher proportion of DD caregivers than of other caregivers described their caregiving experiences as rewarding. Still, a large proportion of DD caregivers had unmet support needs. These findings underscore the importance of supports and services for DD caregivers to manage the challenges and enhance the positive aspects of caregiving.

Future cycles of the GSS will allow for monitoring of the burden of caregiving on this population over time. Additional research could examine the varied impacts on caregivers of individuals with different types of DD and explore differences in experiences by caregiver, care receiver and family demographics and circumstances.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

- SP: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

- SO: Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

- SS: Visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Download in PDF format (556 kB, 8 pages)

Download in PDF format (556 kB, 8 pages)