Acting on ATIP

Archived information

Archived information is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Publication Date: March 2012

Service issues in the Canada Revenue Agency's Access to Information and Privacy processes

Our reports and publications are available in alternate and accessible formats

Office of the Taxpayers' Ombudsman

600-150 Slater Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1K3

Telephone: 613-946-2310 | Toll-free: 1-866-586-3839

Fax: 613-941-6319 | Toll-free fax: 1-866-586-3855

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2012

Cat. No.: Rv10-6/2012

ISBN: 978-1-100-54346-8

Taxpayer Bill of Rights

- You have the right to receive entitlements and to pay no more and no less than what is required by law.

- You have the right to service in both official languages.

- You have the right to privacy and confidentiality.

- You have the right to a formal review and a subsequent appeal.

- You have the right to be treated professionally, courteously, and fairly.*

- You have the right to complete, accurate, clear, and timely information.*

- You have the right, as an individual, not to pay income tax amounts in dispute before you have had an impartial review.

- You have the right to have the law applied consistently.

- You have the right to lodge a service complaint and to be provided with an explanation of the Canada Revenue Agency's findings.*

- You have the right to have the costs of compliance taken into account when administering tax legislation.*

- You have the right to expect the Canada Revenue Agency to be accountable.*

- You have the right to relief from penalties and interest under tax legislation because of extraordinary circumstances.

- You have the right to expect the Canada Revenue Agency to publish its service standards and report annually.*

- You have the right to expect the Canada Revenue Agency to warn you about questionable tax schemes in a timely manner.*

- You have the right to be represented by a person of your choice.*

*Service rights upheld by the Taxpayers' Ombudsman

Report Summary

Our report contains recommendations aimed at making it easier for taxpayers to request and obtain information from the CRA.

The Office of the Taxpayers' Ombudsman has received complaints from taxpayers that they face difficulties obtaining information from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) through requests made pusuant to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. These are commonly referred to as Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) requests. Complaints about the CRA's service with respect to ATIP requests include not responding promptly, not providing enough information about how to file ATIP requests, not explaining the reasons for delays in providing the requested information, and requiring taxpayers to make requests pursuant to the Access to Information Act or Privacy Act (referred to as ‘formal' requests which are processed by the CRA's ATIP Directorate) rather than allowing taxpayers to request the information ‘informally' by simply asking a CRA employee to provide it.

The world's first legislation granting access to government documents was enacted in Sweden in 1766. Today, over 85 countries around the world have implemented some form of access to information legislation. In Canada, the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act came into effect on July 1, 1983. These Acts offer Canadian citizens, permanent residents or any person present in Canada, the legal right to obtain information which is under the control of the federal government, subject to limited and specific exemptions and exclusions. In addition to the exemptions and exclusions of the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act, certain information may be exempted or excluded from release due to the confidentiality provisions of the Income Tax Act, the Excise Tax Act, and the Canada Pension Plan.

Federal government departments and agencies, like the CRA, are bound by the law as set out in these Acts, specifying the time limits within which they must respond to a request for information. The Access to Information Act sets a 30 day limit with the possibility of an extension for a reasonable period of time if, for example, the request encompasses a large number of records or the institution must consult with another department or agency. The Privacy Act sets a 30 day limit with the possibility of an additional 30 day extension to respond to the request. Under both the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act, the reasons for applying the extension must be communicated to the requestor.

Canadians have experienced a decline in the CRA's compliance with the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act since 2005. The number of new requests between the years 2005 and 2010 remained relatively constant. However, the number of pages that needed to be reviewed in responding to a request more than tripled during that time. Since the number of employees assigned to this task has only increased moderately, it is no surprise that the CRA's rate of deemed refusal Footnote 1 increased drastically. To compound the problem, the backlog of requests also grew rapidly. Not surprisingly, there has been an increase in the number of complaints to the Office of the Information Commissioner about the CRA's delays in replying to requests for information. The Office of the Information Commissioner report for 2009-2010 stated that the CRA had the most new complaints among all government entities. We note that 32.5% of these complaints were from one requestor. The CRA received a rating of below standard compliance from the Office of the Information Commissioner for 2008-2009.

The issues described above are consistent with the complaints our Office has received. Our investigation into these complaints revealed that, in several instances, even though the CRA had invoked an extended deadline, it failed to provide a completed response to the request before the extended deadline had been reached. Some complainants were left not knowing when they could expect to receive the information they had requested or whether anyone was working on their request. Our investigation concluded that this situation is unfair to taxpayers and contrary to Article 6 of the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, which states: “You have the right to complete, accurate, clear, and timely information.”

As well, these delays can have a negative impact on taxpayers wanting to know the reasons for the CRA's decision on an objection or appeal prior to making a decision to file an appeal with the Tax Court of Canada. Without the proper information, taxpayers are left not knowing whether or not filing to the Court is advisable.

During the course of this investigation, the CRA provided our Office with its ATIP Directorate 2010 Business Plan, which identified similar issues and established steps to address them. The CRA has developed a business case for the provision of resources to the ATIP Directorate to ensure compliance with the requirements of the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act. Additionally, the CRA launched its new ATIP Web pages on its Web site in May 2011. These pages offer information to the public on how to submit a request, what type of information is available for request, and how to contact the CRA's ATIP Directorate. In accordance with the Government of Canada's open government commitment, the CRA has now established a Web site where it will proactively disclose summaries of released Access to Information (ATI) requests.

Notwithstanding the CRA's efforts in this regard, our report contains recommendations for further improvements that are aimed at making it easier for taxpayers to request and obtain information from the CRA. The Ombudsman recommends that the CRA ensure that efficient processes and adequate resources are put in place within the ATIP Directorate to address the processing of information requests and reduce the backlog in a timely manner. Footnote 2 The Ombudsman also recommends that the CRA develop clear policies and procedures regarding informal disclosure and provide enhanced training to its personnel. Additionally, the Ombudsman recommends that the CRA provide the public with clear information on how to make informal requests for information and advise the public when extended requests will not be met. Finally, the Ombudsman recommends that the CRA continue and enhance the public disclosure of completed ATI requests, and update its communication products in order to promote the availability of this service.

This report contains links to a number of other Web sites. The Office of the Taxpayers' Ombudsman is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

Background

The right to information

“The right to access government information is the necessary prerequisite to transparency, accountability and public engagement.”

Suzanne Legault, Information Commissioner

The world’s first legislation granting access to government documents was enacted in Sweden in 1766. It is known as the Principle of Public Access and has become an integral part of the Swedish constitution. Today, over 85 countries around the world have enacted some form of access to information legislation.

The principles of democracy and human rights are very closely intertwined. Both come from a fundamental belief in the equality of all people who therefore have the right to make an equal contribution to their own governance and be equally protected under the law. Access to information is essential for transparency, accountability, and participation, which are hallmarks of democratic governance. The right to information is embedded in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as Article 19:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

The practice of routinely withholding information from the public creates the perception that the public are ‘subjects’ rather than ‘citizens’ and is a violation of their rights. This was recognized by the United Nations at its very inception in 1946, when the General Assembly resolved that “Freedom of Information is a fundamental human right and the touchstone for all freedoms to which the United Nations is consecrated.”Footnote 3

In a democracy like Canada, the quasi-constitutional right enshrined in the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act allows citizens to access records and information from the federal government. These Acts came into force in 1983, one year following the patriation in Canada of the Constitution and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. They permit Canadians to access information from their government, establish what information could be accessed, and mandate timelines for response. The Access to Information Act is enforced by the Information Commissioner of Canada, and the Privacy Act is enforced by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

In October 2011, representatives at the International Conference of Information CommissionersFootnote 4 declared the following:

The International Conference of Information Commissioners is in favour of enshrining the right of information in national laws and of further developing existing rights of access to information. All states should above all have strong freedom of information laws which really and truly enable citizens to exercise the right to know. An effective appeal mechanism and its enforcement is of significant importance. The states and the international organizations should provide more information than before about their activities. The technical means are available for achieving this!

The Conference encourages states and international agencies to make greater use of the Internet for this purpose and to make information available in a proactive, structured and user-friendly way (Open Data). The conference supports the Open Government Declaration15 published in September 2011 in New York.Footnote 5

In her November 10, 2011 report titled Transparency in Canada: A Time for Great Expectations, Canada’s Information Commissioner stated

“The right to information is a fundamental human right; the right to information in [the] 21st century has broad implications for the well being of Canadian society… [and] for the well being of society as a whole. Canadians should have high standards, they should have great expectations, [the] international community should have high standards for Canada. [We] should reclaim our leadership role in transparency because it has the power to transform lives at home and abroad.”

While we recognize there are confidentiality provisions and security classification rules within the Income Tax Act, the Excise Tax Act, and the Canada Pension Plan that must be respected, our Office believes that access to information should be a strong priority for the CRA and that taxpayers should therefore have access to the information they are requesting in a timely manner.

Introduction

The Office of the Taxpayers' Ombudsman has received complaints from taxpayers stating that they face difficulties in obtaining information from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) through requests made pursuant to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. These are commonly referred to as Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) requests.

Complaints about the CRA's service with respect to ATIP requests include not responding promptly, not providing enough information about how to file ATIP requests, not explaining the reasons for delays in providing the requested information, and requiring taxpayers to make requests pursuant to the Access to Information Act or Privacy Act (referred to as ‘formal' requests which are processed by the CRA's ATIP Directorate), rather than allowing taxpayers to request the information ‘informally' by simply asking a CRA employee to provide it. Footnote 6

The scope of our review

Pursuant to the Acts referred to above, departments and agencies have a legal obligation to provide timely access to information. Whether or not the CRA is meeting the legislated requirements for timely access falls within the purview of the Information and Privacy Commissioners. However, by failing to provide complete, accurate, clear, and timely information to taxpayers making ATIP requests, the CRA is neglecting to comply with the Taxpayer Bill of Rights and this matter falls within the purview of our Office.

The Taxpayer Bill of Rights informs taxpayers of what they can expect from the CRA in regard to service and fairness:

- Clear, complete, accurate, and timely information (Taxpayer Bill of Rights, Article 6). In other words, taxpayers should get all their requested information in understandable language and within the legislated timeframes.

- Fair and professional treatment (Taxpayer Bill of Rights, Article 5). Taxpayers should expect that the CRA meet its responsibilities under the law.

- Accountability (Taxpayer Bill of Rights, Article 11). Taxpayers have the right to know the status of their requests for information and to be updated on progress.

Requests, whether through the Access to Information Act or the Privacy Act, are all processed by the CRA's ATIP Directorate. Many people are unaware of the Privacy Act and submit Privacy Act requests on Access to Information Act forms; the CRA processes them nonetheless. Most of the complaints our Office received were regarding Privacy Act requests that were submitted on Access to Information Act forms. Access to Information Act requests include requests for policies and procedures or copies of internal memoranda or other communications.

Some of the complaints received in our Office involved situations in which the taxpayer waited for over a year to obtain the information requested from the CRA. If a request is not completed within the legislated timeframe, there is no legal obligation for a government agency to provide requestors with status updates on their requests.

Our investigation focused on the following issues:

- The impact on taxpayers of delays in receiving the requested information from the CRA;

- The challenges the CRA faces in meeting informal requests for information; and

- The benefits of proactive disclosure.

Understanding the Rules

The Mandate of the Taxpayers' Ombudsman

The Office of the Taxpayers' Ombudsman was created to support the government priorities of stronger democratic institutions, increased transparency within institutions, and the fair treatment of all Canadians.

The Taxpayers' Ombudsman is mandated to provide advice to the Minister of National Revenue on service issues within the CRA. This is why the Ombudsman makes recommendations on systemic issues directly to the Minister.

The Taxpayers' Ombudsman fulfills this mandate by reviewing service complaints from taxpayers about the CRA, informing Canadians about their rights as taxpayers, upholding the eight service rights within the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, and identifying and reviewing systemic issues and emerging trends related to service matters.

An ombudsman is an independent and impartial officer who deals with complaints about an organization. After reviewing a complaint impartially, an ombudsman determines whether or not the complaint has merit and advises the parties of the conclusion. Where a complaint is found to have merit or be indicative of a systemic problem that may negatively affect stakeholders, an ombudsman typically makes recommendations to correct the problem with a view to preventing recurrence.

What is ‘ATIP'?

The Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act came into effect on July 1, 1983. These Acts (commonly referred to as ATIP legislation) provide to Canadian citizens, permanent residents, or any person present in Canada, the legal right to obtain information in any form which is under the control of the federal government. They are enforced by the Information Commissioner and the Privacy Commissioner respectively.

The President of the Treasury Board of Canada is responsible for the government-wide administration of the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. The Minister of National Revenue is responsible for the administration of these Acts within the CRA. The Minister in turn has authorized the ATIP Director to exercise, within the CRA, all powers, duties, and functions granted to the Head of the Institution under these Acts.

The Access to Information Act provides a right of access to all information held by the government (except personal information). This right of access is subject to limited and specific exemptions (such as information that could reasonably be expected to facilitate the commission of a criminal offence or threaten the safety of individuals), and is subject to some exclusions (such as confidential Cabinet documents). Under this legislation, the CRA has 30 days to either provide the documents requested through the ATI request or provide notification that access is refused, or advise the requestor that the CRA will require additional time (an extension) to respond. Extensions may be justified when there is a need to consult with other government departments or agencies, when the request encompasses a large number of documents, and/or when the response would unreasonably interfere with normal operations of CRA.

The Privacy Act provides Canadians with access to their personal information held by a government institution, again subject to limited and specific exemptions and exclusions. An institution has 30 days to provide the information requested, or provide notification that access is refused. The Privacy Act, however, states that institutions can request an extension of an additional 30 days:

- if meeting the original time limit would unreasonably interfere with the operations of the government institution;

- if consultations are necessary to comply with the request that cannot reasonably be completed within the original time limit, or such period of time as is reasonable; or

- if additional time is necessary for translation purposes or for the purpose of converting the personal information into an alternative format.

Subsection 4(2.1) of the Access to Information Act, also known as the ‘duty to assist' section, which came into force in 2007, sets out the general expectations for government departments and agencies, including the CRA, for helping requestors obtain the information they are seeking. It states:

The head of a government institution shall, without regard to the identity of a person making a request for access to a record under the control of the institution, make every reasonable effort to assist the person in connection with the request, respond to the request accurately and completely and, subject to the regulations, provide timely access to the record in the format requested.

In other words, institutions have a legislated duty to make every reasonable effort to help requestors with their access requests. New subsection 4(2.1) codifies best practices that were always intended to apply.

The Role of the CRA's ATIP Directorate

The Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) Directorate of the CRA is responsible for fulfilling the CRA's legislative requirements relating to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. The ATIP Directorate, which is part of the CRA's Public Affairs Branch, is responsible for the following tasks:

- Responding to formal requests made under the legislation.

- Providing advice and awareness training to CRA employees and management – on handling personal information within the Agency, as well as on responsibilities and obligations under the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act.

- Conducting interdepartmental consultations.

- Collaborating with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Responding to complaints or audits from the offices of the Information and Privacy Commissioners of Canada.

When an ATIP request is received by the CRA, it is assigned to an analyst in the ATIP Directorate. The analyst then sends a request to the applicable branches, program areas, or employees of the CRA to provide the required requested information. Once the information has been gathered, it is returned to the analyst who then reviews it to ensure that the release of the information, and any exemptions from the release, comply with the legislation.

Taxpayer Complaints

Deemed refusal is defined as not having received the requested information after the time limits as set out in the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act legislations.

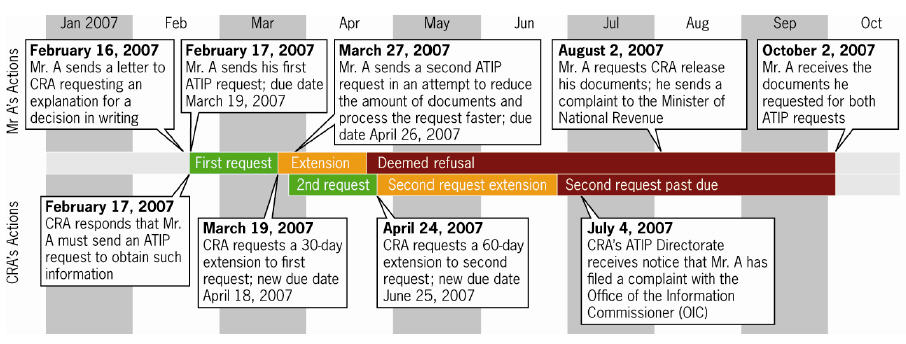

Mr. A's story – Access delayed eight months

Mr. A was not satisfied with the CRA's ruling on his employment status. Footnote 7 The CRA had determined that he was not an employee of the company that he worked for and his earnings were therefore not insurable for the purposes of Employment Insurance or pensionable for the purposes of the Canada Pension Plan. Mr. A disagreed with this decision, as he felt he worked under the same conditions of employment as others within the company who were considered employees. He felt that this ruling affected his working relationship with the other employees. Additionally, not being an employee meant he did not receive the benefits of being an employee, such as participation in the health and dental plans.

Mr. A filed an appeal with the Appeals Branch of the CRA, which confirmed the original decision. Mr. A believed his reasoning was sound and wanted to take his case to the Tax Court of Canada, but before committing to the time and expense required to go to court, Mr. A wanted to understand the CRA's rationale for its decision. Mr. A requested information from the CRA about the reasons for the decision by the Appeals Branch so he could make an informed decision of his own.

Mr. A originally requested the documents informally, by contacting the agent assigned to his file and simply asking for a copy of the documents, however, the CRA would not provide them, nor would it provide a written explanation of the decision. The CRA advised Mr. A that he had to request the documents formally by filing an ATIP request, and sent him an ATIP request form.

Mr. A submitted a formal ATIP request for all documents relating to the ruling and subsequent appeal on February 17, 2007. The CRA sent a letter to Mr. A on March 19, 2007, advising that it required a 30 day extension. Mr. A then submitted a modified request on March 27, 2007, this time asking just for copies of the draft and final reports, in the hope that a smaller request could be dealt with more quickly. Again, on April 24, 2007, the CRA advised Mr. A that it required an extension, this time for 60 days. The law requires that appeals to the Tax Court of Canada be filed within 90 days of receiving a decision on an objection. Mr. A had to file his appeal with the Tax Court of Canada by May 15, 2007. Because he did not receive the requested documents, Mr. A stated that he, “filed for Tax Court without any appreciation or understanding of why the appeal to the CRA's Appeals Branch had been found against [him].”

Mr. A subsequently submitted a complaint to the Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC). The OIC review found that at the time the extension was invoked, the CRA's ATIP Directorate was experiencing a shortage of resources and a heavy workload. However, given the nature of Mr. A's request and the volume of records involved, the OIC was of the view that a 30-day extension should have been sufficient for the CRA to provide a timely response. Nonetheless, the CRA failed to meet the extended due date and fell into a deemed refusal situation pursuant to subsection 10(3) of the Access to Information Act.

Mr. A wrote to the CRA again in August 2007 requesting that the CRA release his documents. He did not receive a response to his letter. In fact, our investigation confirmed that from the time he received the letter in April 2007 advising him that the CRA required a second extension until the time he finally received the documents on October 2, 2007 (almost eight months after his original request), the CRA did not contact him at all.

In March 2008, shortly after our Office opened, Mr. A submitted a complaint expressing his overall dissatisfaction with the ATIP request process and timelines. Our investigation determined that the CRA could have provided a better level of service to Mr. A, and we recommended that the CRA offer Mr. A an apology. The CRA concurred and issued a letter to Mr. A expressing regret for the delays in providing him with the information he had sought through his ATIP request and for neglecting to respond to his requests for an explanation of the ongoing delays.

Figure 1. A timeline of Mr A's story

Mr. B's story – Access delayed fourteen months

On April 21, 2009, Mr. B submitted his ATIP request for copies of the information the CRA had on file regarding an audit of his business account. The business had 90 days to file an objection to the audit assessment. He wanted to understand the reasons for the audit outcome. After seeking clarification on Mr. B's request, the CRA formally acknowledged receipt with an official ATIP date of May 12, 2009. On June 12, 2009, 30 days after the official receipt of the request, the CRA asked for a 90 day extension.

Mr. B complained to our Office on March 22, 2010, almost a year after he had first submitted his request, that he still had not received the documents. The CRA had fallen into deemed refusal when they failed to respond after the 90 day extension.

Our Office contacted the CRA to determine the status of the request and reasons for the delay. The CRA advised that Mr. B would receive the documents by May 28, 2010. On June 11, 2010, Mr. B informed us he still had not received them. Our Office followed up with the CRA until Mr. B received the documents on July 13, 2010, fourteen months after the CRA acknowledged receipt of his request.

In addition to these complaints, our Office has received complaints from other taxpayers that they faced unreasonable delays in obtaining information from the CRA through ATIP requests. Often taxpayers need the information they requested in order to decide whether they should take the next course of action, for example, going to the Appeals Branch or to the Tax Court. These complaints indicated that we were dealing with a systemic issue that merited an investigation.

Figure 2. A timeline of Mr. B's story

Impact of Delays

A common complaint we have heard from taxpayers is that they are not informed when the CRA is unable to meet the extended deadline (when the file falls into deemed refusal status). Taxpayers have complained to us that the CRA does not advise them when the deadline is not met. The taxpayer is then forced to initiate any follow-up contact to determine the status of their request. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has provided direction to the CRA on how to handle cases in which an extension is necessary:

“If access cannot be given within the deadline, advise the requestor that the time limit cannot be met, indicate when access will be given, and advise of the right to complain to the Information Commissioner. Provide access to whatever records have been processed by the end of the original extension period in accordance with that deadline.” Footnote 8

In her 2010 special report to Parliament, entitled Out of Time, the Information Commissioner, Suzanne Legault, noted that the CRA received optimal compliance ratings from 2003 through 2005. However, in 2008-2009, the CRA's deemed refusal rate was 15.1% and the backlog of requests was growing rapidly. In 2009-2010, the CRA came highest among all federal government departments in the number of new complaints made about it. With a high number of deemed refusals, a growing backlog, and an increasing number of complaints, the CRA was given a rating of ‘below standard' compliance by the Information Commissioner for 2008-2009.

The following Figures 3, 4, and 5, are statistics provided in the CRA's 2010-2011 Annual Report to Parliament on the administration of the Access to Information Act.

Figure 3. The number of ATI requests received by the CRA

| Fiscal year | New requests | Requests completed | Pages reviewed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 1,604 | 2,060 | 403,334 |

| 2007-2008 | 1,903 | 1,636 | 426,750 |

| 2008-2009 | 1,770 | 1,540 | 568,090 |

| 2009-2010 | 1,798 | 1,651 | 1,068,810 |

| 2010-2011 | 2,589 | 2,605 | 1,116,838 |

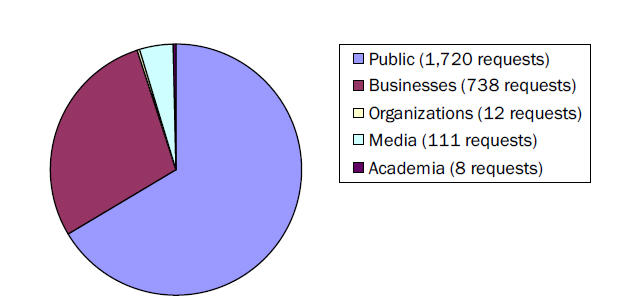

Figure 4. The sources of ATI requests 2010-2011

Figure 4 - List

- Public (1,720 requests)

- Businesses (738 requests)

- Organizations (12 requests)

- Media (111 requests)

- Academia (8 requests)

Figure 5. Time elapsed to complete the ATI requests

| Completion time | Number of requests | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 30 days or less | 556 | 21.34 |

| 31 to 60 days | 519 | 19.92 |

| 61 to 120 days | 672 | 25.80 |

| 121 days or more | 858 | 32.94 |

Privacy Act requests

Individuals have a right of access, subject to exemptions and exclusions, in order to find out what personal information government institutions collect and to ensure that such information is accurate and complete. Under the Privacy Act, individuals have the right to access their personal information and the right to request correction or have a notation added to any recorded personal information that is under the control of a government institution.

The CRA collects extensive volumes of personal information under the Income Tax Act, the Excise Tax Act, and various federal and provincial economic and social benefit programs.

The number of Privacy Act requests the CRA receives, already rising steadily, increased sharply during 2009-2010. Figures 6 and 7 are taken from the CRA's 2010-2011 Annual Report to Parliament on the administration of the Privacy Act.

Figure 6. The number of Privacy Act requests received by the CRA

| Fiscal year | Requests received | Requests completed | Pages reviewed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2007 | 1,912 | 1,971 | 314,374 |

| 2007–2008 | 1,406 | 1,355 | 340,217 |

| 2008–2009 | 1,553 | 1,447 | 392,173 |

| 2009–2010 | 2,083 | 1,973 | 371,766 |

| 2010–2011 | 2,600 | 2,767 | 725,741 |

Figure 7. Time elapsed to complete Privacy Act requests, 2010-2011

| Completion time | Number of requests | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 30 days or less | 584 | 21.11 |

| 31 to 60 days | 869 | 31.41 |

| 61 to 120 days | 978 | 35.35 |

| 121 days or more | 336 | 12.14 |

The ATIP Directorate recently completed a diagnostic of the backlog (prior to April 1, 2010) by reviewing the status of each file and developing a proposed approach to processing each request. Based on this analysis, the ATIP Directorate proposes to significantly reduce the backlog by the end of 2011-2012.

Difficulties in completing requests in a timely manner

The CRA is a large government agency. It recently ranked third in all Government of Canada departments and agencies in volume of ATI requests received. Over the past few years, the CRA's volume of ATIP requests has increased appreciably while resources have increased only moderately, causing a backlog. The compliance rating given to the CRA by the Office of the Information Commissioner has been lower each year. Footnote 9

While the number of new requests sent to the CRA has stayed fairly constant from 2005 to 2010, the backlog of requests in the ATIP Directorate has risen from 25.5% of total requests received in 2005-2006 to 39.8% in 2009-2010.

According to the CRA, a significant number of requests can be attributed to a relatively small number of frequent requestors.

Another cause of the increasing backlog is the number of ‘large requests'–that is, single requests that involve many documents. The retrieval and review of these large requests places a high demand on resources and has a direct impact on the time required for the CRA to complete all its requests. Footnote 10 As stated previously, the ATIP Directorate has a ‘duty to assist' requestors. Large requests are often the result of a requestor knowing they need information, but not knowing what to ask for. Consequently, the requestor casts the widest net possible, hoping that what they get back will answer their questions. Common large requests are for, “my entire file with the CRA” or “all documents relating to the audit on my account.”

Under the legislation, the CRA has a duty to assist and ATIP analysts are required to offer reasonable assistance to the requestor throughout the request process. This includes providing the requestor the opportunity to clarify the request where necessary or appropriate. Therefore, when a large request is received, the ATIP analyst is required to contact the requestor and assist them in understanding what they are requesting to determine whether the request can be made more precise.

The number of employees directly involved in processing requests only moderately increased from 2005 to 2010. In comparison, during the same period, the backlog and the number of pages per request that had to be reviewed grew considerably. As a result, the number of complaints to the Office of the Information Commissioner increased by 300 percent over the past four years.

According to its 2010 business plan, the ATIP Directorate felt it was evident that without new resources, the gap between capacity and workload would quickly rise to unmanageable levels, which would mean more delays and inadequate service for taxpayers submitting a request under the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. In 2010, the CRA began to implement changes and hire new employees. The ATIP Directorate also created a new team solely dedicated to reducing the backlog. The CRA stated that the backlog accumulated prior to April 2010 was expected to be eliminated by March 2012.

Making an ATIP request to the CRA

Until May 2011, the CRA did not have information on how to make ATIP requests available on its Web site or in its publications. This caused considerable frustration for taxpayers, as taxpayers wanting to submit a request had to call the CRA Enquiries lines Footnote 11 to either be redirected to the Government of Canada's Info Source Web site (Sources of Federal Government and Employee Information), which contains information about ATIP as well as the forms and instructions on how to file a request, or to the CRA's own ATIP General Enquiry line.

As a result of directions from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to all government departments to facilitate access to the ATIP process, in May 2011 the CRA launched its new ATIP Web pages. The CRA now posts the following on its Web site:

- The description of taxpayers' rights under the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act.

- The description of the institution classes of records.

- The list of manuals.

- The locations of the reading rooms.

- The CRA's ATIP Directorate contacts.

We note that these new Web pages offer improved service to Canadians and bring the CRA in line with Government of Canada guidelines.

Informal Requests for Information

Obtaining information by submitting an ATIP request under the Access to Information Act or Privacy Act is a formal, legislated process requiring a level of documentation and oversight that aims to ensure a rigorous response. It can, however, lead to delays. In addition to invoking their legislated right to information, taxpayers can also request information informally.

What is an informal request?

Taxpayers can make an informal request in writing or verbally to a CRA employee. It is not necessary to use a form and the request can be made to any CRA official without referring to the Access to Information Act or the Privacy Act. Exemptions and exclusions to the right of access do not apply to informal requests. However, limitations under other acts such as the Income Tax Act, the Excise Tax Act, and the Canada Pension Plan do apply. It should be noted that taxpayers who make an informal request have no rights of appeal under the Access to Information Act or Privacy Act, say for example, if the requestor did not receive all of the records that were requested.

Internal reference documents state that, “The ATIP Directorate will…give advice regarding the release of records for an informal request.” Additionally, in its 2009-2010 Annual Report to Parliament, the CRA stated that, “The Access to Information Act's formal processes do not replace other procedures for obtaining government information. In accordance with this principle, the CRA encourages individuals, businesses and other groups to explore the informal methods of access at their disposal.” The CRA's ATIP Directorate provides guidance to CRA employees on processing ATIP requests, including informal requests. The CRA ATIP Directorate Reference Manual states: “The informal method of asking for access is considered to be the ‘preferred method' of access, and a response should be provided if possible.”

The CRA does not have any published information about informal disclosure. On its Web page, “How to access information at the CRA” under the heading “Tips for submitting a request,” there is only the statement, “Ask if there are other methods of requesting the information you require without having to submit a formal request.”

What kind of information can be released informally?

Generally, information should be released informally when it is the taxpayer's own personal information or it pertains to the CRA's research, opinions, or evaluation of the taxpayer's file, and when it relates to CRA's policies and procedures. Information that may be released informally to a taxpayer or an authorized representative includes:

- copies of income tax (T1) returns;

- auditor's Report;

- audit working papers (excluding third-party information, leads, disclosure of audit techniques and information from informants);

- correspondence and internal memoranda, appropriately severed where necessary;

- related correspondence with Headquarters (e.g., technical interpretation requests or opinions and referrals to specialized sections relating to a specific person);

- related reports from CRA valuators, appraisers, Electronic Commerce Audit Specialists, science advisors, external consultants' appraisals and reports; and

- severed versions of operational manuals available to the public in the Tax Service Offices Reading Rooms.

What is severing?

It is the act of removing (or blocking) information in a document that could cause jeopardy to the organization or because it contains another taxpayer's confidential information. Information is severed according to the exemptions for release provided in the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act.

However, the complaints received by our Office reveal that it is not always easy to obtain documents that should be released informally. One taxpayer told us that when she asked for a copy of the Auditor's report and working papers (in December 2010), she was told to submit an ATIP request. According to the CRA's policies and procedures, the documents requested by the taxpayer should have been released informally.

Training for CRA employees

Between 2009 and 2011, a total of 1,986 CRA employees (e.g. auditors, appeals officers, team leaders, directors, directors general, etc.) and an additional 718 managers participating in the Management Learning Program attended ATIP training sessions. These training sessions provide employees with training on the ATIP legislation, what information should be released, and what should be exempted. The sessions also emphasize that informal access is the CRA's preferred method of access and remind managers that they should ensure their employees provide requested information informally whenever possible.

Additionally, the ATIP Directorate hired a full-time training facilitator in December 2010 to develop and provide training and awareness products geared towards the program areas that receive the most ATIP requests.

We note that the ATIP Directorate has updated its intranet Web site to provide more direction to all CRA branches when responding to ATIP requests, as well as revising a document used to request information from CRA employees. The CRA informs us that the ATIP Directorate will continue to provide all CRA branches with tools and training to help reduce out-of-scope records sent to the ATIP Directorate for processing. A record is ‘out of scope' when it contains information that is not relevant to the request.

Proactive Disclosure

“Any material available to me in a Public Reading Room…is located over 700 kms from me.”

Complainant

As stated in the Information Commissioner's Annual Report 2009-2010, “Proactive disclosure is a fundamental aspect of freedom of information and open government, and we strongly encourage institutions to consider its value.”

For many years the CRA has had reading rooms located in major cities across the country, where the public could go to view copies of manuals, information circulars, and interpretation bulletins. Taxpayers wishing to review these documents were required to either travel to the nearest reading room location, or submit a request for the information to be mailed to them.

To make information more readily accessible, other government departments such as Health Canada, the Department of National Defence, and the Office of the Information Commissioner, have created virtual reading rooms. These virtual reading rooms, which are accessible on the Internet via the department's Web site, constitute the proactive release of documents such as manuals and ATI requests that were previously requested and disclosed. They do not contain the entire copy of the document, but rather a summary of the information provided in response to a prior request. The requestor can then ask for a copy of the previously released information. This allows the department to release the information in a timely manner, as it has already been gathered and reviewed. It is less time consuming and labour intensive, allowing for a request to be released promptly.

On March 18, 2011, the Government of Canada announced its continuing commitment to enhancing transparency and accountability to Canadians in a statement about the expansion of open government. Following that announcement, many institutions started posting the summaries of completed ATI requests on their Web sites. Institutions were expected to begin posting summaries of completed ATI requests as of January 2012.

Accordingly, the CRA has developed a Web page dedicated to proactive disclosure of ATI requests. This page is easily accessible from the CRA's main page under “Completed access to information requests.” While the entire document will not be available for viewing on the Web site, the list will indicate which documents are available to be released informally. The first available documents, from ATI requests received in December 2011, are available as of January 31, 2012.

We recognize that this new service provided by the CRA brings the CRA in line with the Government of Canada's commitment to open government.

Conclusion

The CRA has a daunting task in complying with the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act when legislated requirements are combined with the CRA's obligation to provide good service. Responding to requests is costly for an organization. However, the service is funded by taxpayers and should accordingly be available to all taxpayers. Nevertheless, due to the lack of resources and insufficient emphasis on informal disclosure, it has been difficult for the ATIP Directorate to effectively manage its workload and be compliant with the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act requirements.

The CRA began hiring additional personnel in mid-2010. A team was created to specifically address the backlog of requests. There will also be additional resources in the coming year, which means that the workload should become more manageable, the backlog should be addressed in a timely manner, and there should be fewer delays for requestors. With this new team, the CRA is making an effort to improve service delivery to taxpayers. Our Office is of the opinion, however, that more needs to be done. Nevertheless, it is recognized that the CRA must maintain reasonable flexibility in the allocation of its resources. For example, if the CRA were to reduce the number of formal requests for information it may not require additional resources to process such requests.

Keeping requestors informed

Our analysis suggests that the CRA should do more to inform requestors when it is unable to meet the extended deadline, as well as to provide an estimated timeframe for completion. It would likely minimize complaints if a requestor were kept informed of the status of their file after it had fallen into deemed refusal status.

Requestors should know what to ask for and how to ask for it

The current system places the onus on requestors to know what documents they want and this has frequently led to requestors making the widest possible request to ensure they will receive all the information they are looking for. The focus on clarifying the scope of the request early is one step towards remedying this issue. A request that is specific and precise before being sent to the CRA's program areas would assist in shortening turnaround time for initial preparation. Early discussion and clarification with a requestor can serve to narrow the scope of a request and make it more precise. Greater involvement of the ATIP Directorate at these early stages would increase the likelihood of the request being forwarded to the appropriate section.

In its 2009-2010 Annual Report to Parliament, the CRA advised that the ATIP Directorate will implement a plan to update its Web site to ensure that it, “provides the public with general information about formal Access to Information Act and Privacy Act request processes” and “highlights how to request information formally and informally.” We find that the CRA could provide better service by informing taxpayers about what type of information can be released informally. As stated previously, the CRA Web site only mentions general advice under, “Ask if there are other methods of requesting the information you require without having to submit a formal request.”

Releasing information

Although the CRA states that informal requests are the preferred method for information requests, there is insufficient direction to both the public and CRA employees to encourage informal requests. The CRA should make personnel in the various program areas more aware of what can be responsibly released informally.

It is important that employees dealing with taxpayers know what an ATIP (or formal) information request is, what an informal request is, and how to differentiate between them and address each. Since informal requests are the CRA's preferred method of providing information, we find that the CRA should specifically improve and make readily available information about informal requests so that its employees are able to address such requests in a timely manner. Promoting the informal release of information would avoid having to advise the requestor to submit a formal request, which can take more than three months to address and unnecessarily increase the ATIP Directorate's workload.

A more proactive approach in releasing information could lead to narrower requests, avoid delays in responding to requests, and increase the CRA's ability to meet the Access to Information Act legislation and the Office of the Information Commissioner ratings of compliance. Increasing information on how to release documents informally, and promoting proactive disclosure of information, by such means as the new Web page for completed Access to Information Act, will all work towards decreasing the number of formal information requests that need to be processed by the ATIP Directorate.

Recommendations

Based on the foregoing, the Taxpayers' Ombudsman recommends that the CRA:

- Ensure that the ATIP Directorate has efficient processes and adequate resources to reduce the backlog and process information requests in a timely manner;

- Promote the use of informal disclosure internally;

- Develop and communicate to its personnel clear policies and procedures for informal disclosure;

- Provide enhanced training to its personnel with regard to informal requests for information, particularly in the program areas that receive the most requests;

- Provide more complete information publicly to taxpayers about informal requests for information through its Web site, publications, and telephone enquiry lines;

- Advise requestors when the extended deadline will not be met for their request and it will fall into deemed-refusal status; and

- Continue and enhance the release of completed access to information requests through its virtual reading room, and update its communication products in order to raise awareness of this service.