Government of Canada’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory

The Greening Government Strategy established climate and environmental commitments for the Government of Canada’s internal operations. These operations will be net-zero emissions by 2050 including:

- Government owned and leased real property

- Mobility: fleets, business travel and commuting

- Procurement of goods and services

- National safety and security operationsFootnote 1

Visit the Open Government portal for more information about GHG emissions from federal facilities and fleets.

To implement net-zero in real property and fleet operationsFootnote 2, the Government of Canada will reduce absolute Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions by 40% by 2025 and at least 90% below 2005 levels by 2050. On this emissions reduction pathway, the government will aspire to reduce emissions by an additional 10% each 5 years starting in 2025.

Scope 1 GHG emissions are produced by sources that are owned or controlled by the government. For example, the greenhouse gases emitted from the combustion of fuels in vehicles or in buildings. Scope 2 GHG emissions are those generated indirectly from the consumption of purchased energy (electricity, heating, and cooling). Scope 3 GHG emissions are indirect such as the emissions produced in the supply chain of the goods and services we buy.

Progress Summary

Progress on all reported sources of GHG emissions for facilities, fleets, and employee work-related air travel. Updated data for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 shows that GHG emissions continue a downward trend. Operational improvements (e.g. portfolio rationalization, increased energy efficiency) and clean electricity procurement contributed to a reduction of GHG emissions from the previous year (2023-24).

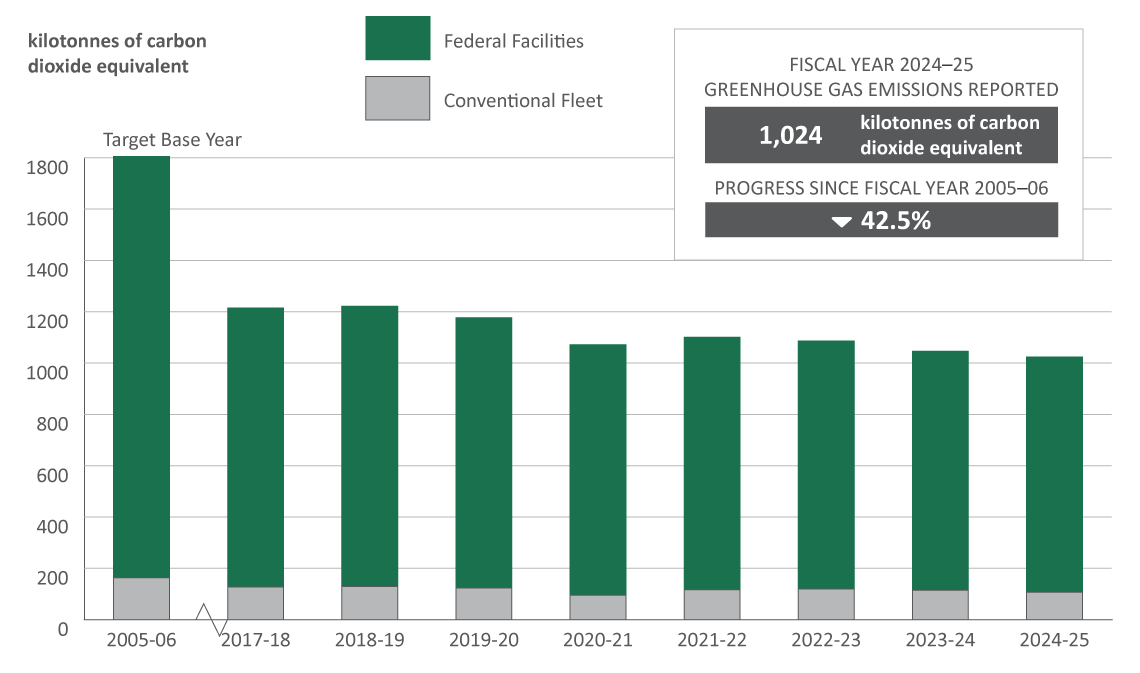

Figure 1 - Text version

The bar graph shows the total greenhouse gas emissions from facilities and conventional fleet operations in kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent reported from fiscal years 2005 to 2006 to 2024 to 2025. In fiscal year 2024 to 2025 the federal government reported 1,024 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, which represents a 42.5% reduction since fiscal year 2005 to 2006. Between fiscal years 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019, the GHG inventory was expanded to cover all core departments owning facilities and/or fleets with more than 50 vehicles, increasing the number of reporting organizations from 15 to 29. Therefore, when comparing data from between fiscal years 2010 to 2011 and 2016 to 2017 to post-2017 years, one must account for this change. Comparisons of the current year with the 2005 to 2006 base year are always valid, because as departments were added, their emissions were also added to the base year.

| Fiscal Year | Federal Facilities Emissions (kt CO2 eq) | Conventional Fleet Emissions (kt CO2 eq) | Total Emissions (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-06 | 1,616 | 165 | 1,781 | - |

| 2017-18 | 1,088 | 127 | 1,215 | -32.3% |

| 2018-19 | 1,092 | 129 | 1,221 | -31.9% |

| 2019-20 | 1,054 | 123 | 1,177 | -34.4% |

| 2020-21 | 976 | 95 | 1,071 | -40.3% |

| 2021-22 | 984 | 117 | 1,101 | -38.6% |

| 2022-23 | 966 | 120 | 1,086 | -39.8% |

| 2023-24 | 933 | 115 | 1,048 | -42.0% |

| 2024-25 | 917 | 107 | 1,024 | -42.5% |

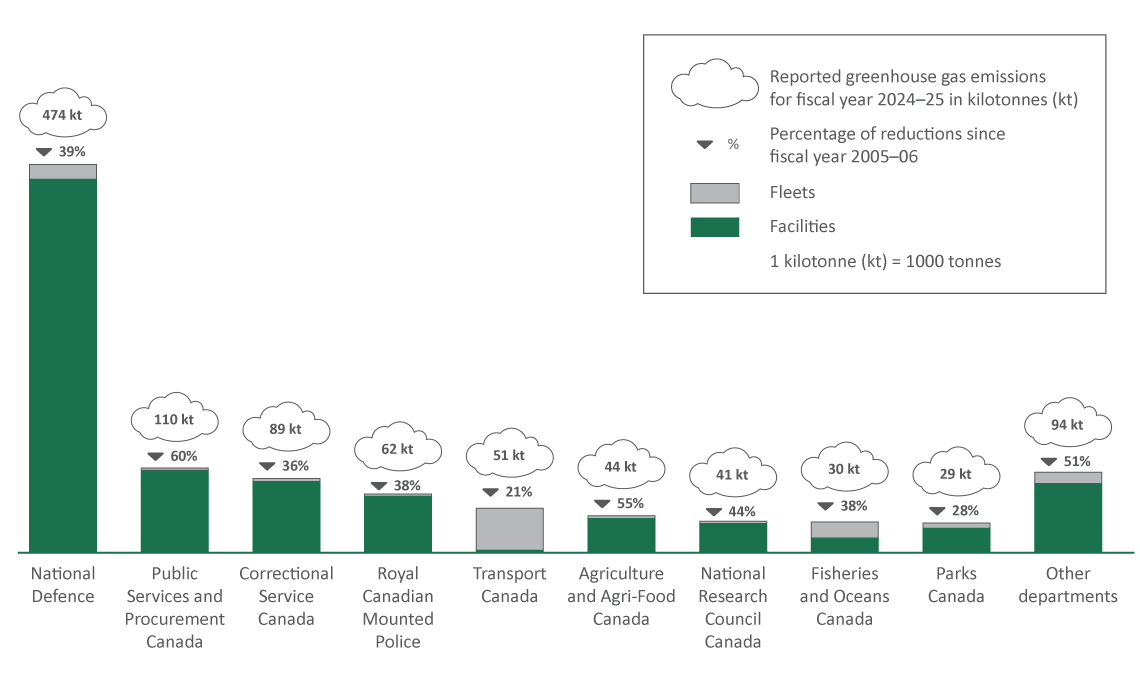

Figure 2 - Text version

The bar graph shows the total greenhouse gas emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon equivalent) reported in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, for facilities and conventional fleet operations by federal organization. The greenhouse gas emissions are separated by facilities or fleet. The percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 is also shown for each federal organization.

| Federal organization | Emissions from facilities for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions from fleets for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Total Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Total Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Defence | 455.9 | 18.5 | 474.4 | 778.8 | -39% |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 109.1 | 0.6 | 109.8 | 271.3 | -60% |

| Correctional Service Canada | 87.3 | 1.9 | 89.2 | 140.2 | -37% |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 61.2 | 0.9 | 62.1 | 99.8 | -38% |

| Transport Canada | 4.1 | 46.7 | 50.8 | 64.3 | -21% |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 41.1 | 3.3 | 44.4 | 99.3 | -55% |

| National Research Council Canada | 39.8 | 1.1 | 41.0 | 72.6 | -44% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 22.9 | 7.2 | 30.0 | 48.2 | -38% |

| Parks Canada | 14.6 | 13.9 | 28.5 | 39.8 | -28% |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 13.6 | 2.4 | 15.9 | 32.8 | -51% |

| Natural Resources Canada | 17.2 | 0.7 | 17.9 | 34.3 | -48% |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 9.9 | 2.4 | 12.4 | 22.0 | -43% |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 5.9 | 4.2 | 10.1 | 12.8 | -21% |

| Health Canada | 8.4 | 0.2 | 8.6 | 22.0 | -61% |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 6.7 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 7.1 | -5% |

| Public Safety Canada | 4.7 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 6.8 | -30% |

| Communications Security Establishment | 5.4 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 10.1 | -46% |

| Library and Archives Canada | 2.5 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | -38% |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.7 | -33% |

| Polar Knowledge Canada | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.9 | N/A | N/A |

| Canadian Space Agency | 1.3 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 2.4 | -43% |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.9 | -59% |

| Shared Services Canada | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 2.0 | -16% |

| Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.4 | -66% |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | -51% |

| National Battlefields Commission | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | -23% |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.4 | -88% |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | -70% |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.1 | -76% |

| Total | 917 | 107 | 1,024 | 1,781 | -42.5% |

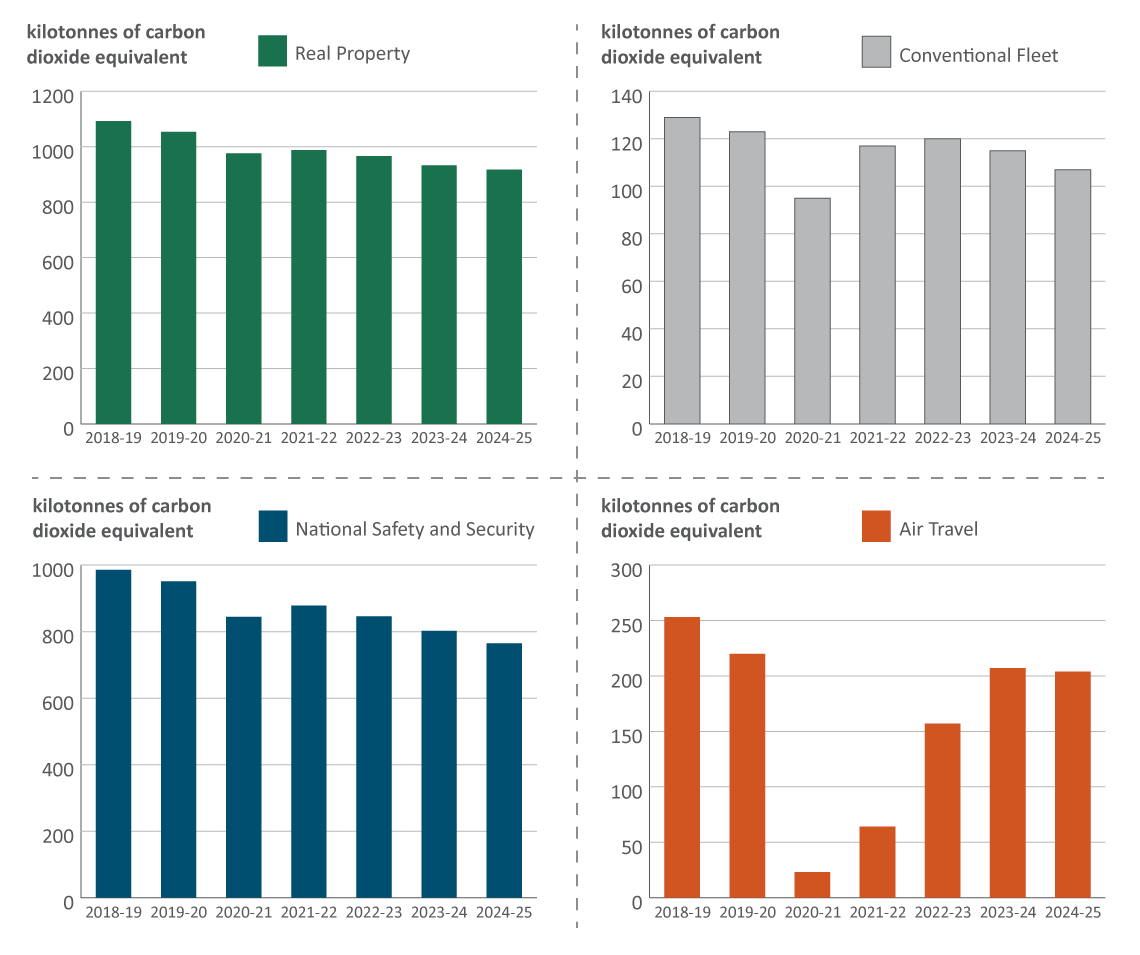

Figure 3 - Text version

The bar graphs show the GHG emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) reported between fiscal years 2018 to 2019 and 2024 to 2025, for federal facilities, conventional fleet, national safety and security fleet operations and employee work-related air travel.

| Fiscal Year | Federal Real Property Emissions (kt CO2 eq) | Conventional Fleet Emissions (kt CO2 eq) | National Safety and Security Fleet Emissions (kt CO2 eq) | Air Travel Emissions (kt CO2 eq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | 1,092 | 129 | 986 | 252 |

| 2019-20 | 1,054 | 123 | 951 | 220 |

| 2020-21 | 976 | 95 | 844 | 23 |

| 2021-22 | 988 | 117 | 878 | 64 |

| 2022-23 | 966 | 120 | 846 | 157 |

| 2023-24 | 933 | 115 | 802 | 206 |

| 2024-25 | 917 | 107 | 765 | 204 |

Key results

- 29 federal organizations reported GHG emissions between fiscal years 2018 to 2019 and 2024 to 2025

- The federal facilities and conventional fleet emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 totaled 1,024 kilotonnes (kt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq), which represents a decrease of 757 kt CO2 eq or 42.5% (excluding National Safety and Security emissions), compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- Emissions from facilities, fleets and air travel have all been trending downward in recent years, even as operations rebound from the lows of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- GHG emissions from federal facilities in fiscal year 2024 to 2025 totaled 917 kt CO2 eq, which is a reduction of 699 kt CO2 eq or 43.3% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the federal conventional fleet generated 107 kt CO2 eq, which is a reduction of 58 kt CO2 eq or 35% lower than fleet emissions in fiscal year 2005 to 2006

Facilities

Scope: 1,2

Greenhouse gas emissions from federal facilities

The federal government has one of the largest and most diverse portfolios of facilities in the country, including:

- the buildings on Parliament Hill

- aircraft hangars on military bases

- laboratories

- correctional institutions

- office buildings and warehouses

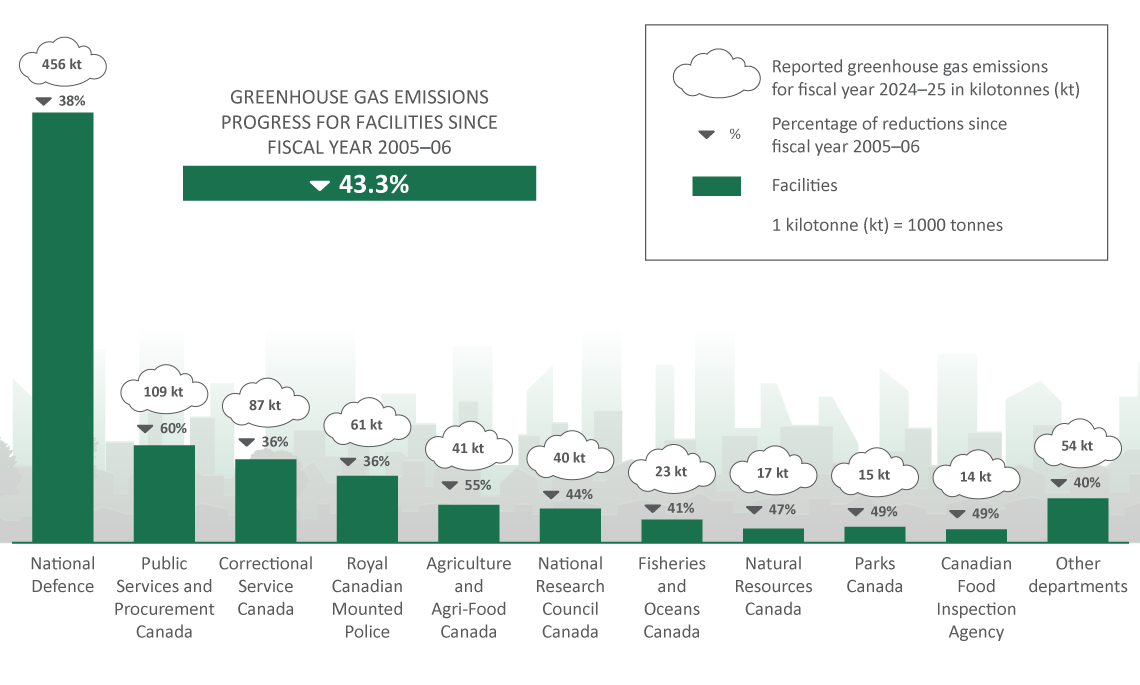

Figure 4 - Text version

The bar graph shows the total GHG emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon equivalent) reported in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, for facilities by federal organization. Above each bar is the organization’s emissions in 2024 to 2025, as well as the percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 for each federal organization.

| Federal organization | Emissions from facilities for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions from facilities for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Defence | 735.5 | 455.9 | -38% |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 269.8 | 109.2 | -60% |

| Correctional Service Canada | 137.4 | 87.3 | -36% |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 95.6 | 61.2 | -36% |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 91.2 | 41.1 | -55% |

| National Research Council Canada | 71.3 | 39.8 | -44% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 38.5 | 22.9 | -41% |

| Natural Resources Canada | 32.5 | 17.2 | -47% |

| Parks Canada | 28.5 | 14.6 | -49% |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 26.5 | 13.6 | -49% |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 17.4 | 9.9 | -43% |

| Health Canada | 20.4 | 8.3 | -59% |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 8.4 | 5.9 | -30% |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 7.1 | 6.7 | -5% |

| Transport Canada | 6.8 | 4.1 | -40% |

| Communications Security Establishment | 10.1 | 5.4 | -47% |

| Public Safety Canada | 6.8 | 4.7 | -30% |

| Library and Archives Canada | 4.0 | 2.4 | -38% |

| Polar Knowledge Canada | N/A | 1.9 | N/A |

| Canadian Space Agency | 2.4 | 1.3 | -44% |

| Shared Services Canada | 1.3 | 1.3 | 7% |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 1.1 | 0.5 | -51% |

| Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services | 2.4 | 0.8 | -66% |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 0.3 | 0.2 | -51% |

| National Battlefields Commission | 0.1 | 0.2 | 34% |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 0.5 | 0.04 | -92% |

| Total | 1,615 | 917 | -43.3% |

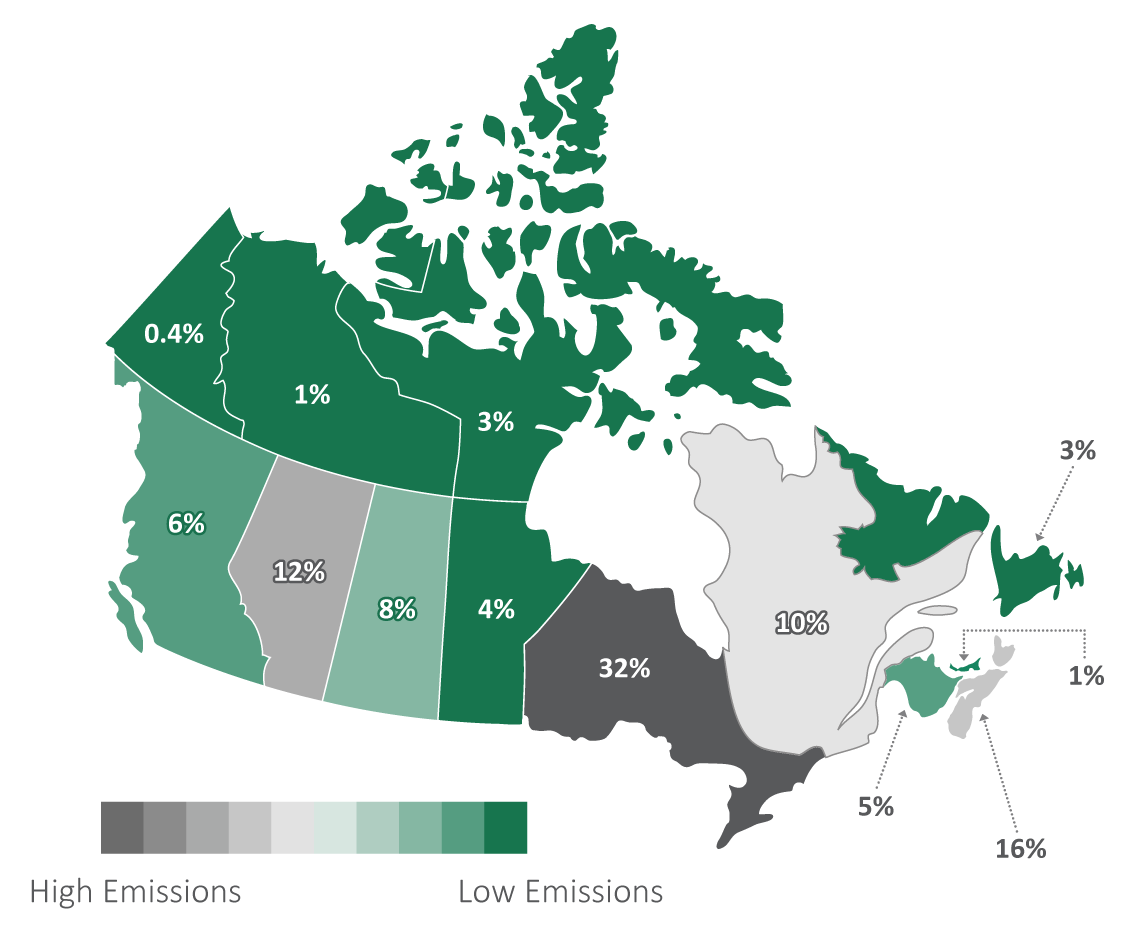

Figure 5 - Text version

The figure is a map of Canada that shows the regional distribution of GHG emissions from federal facilities in fiscal year 2024 to 2025.

| Region | Emissions from stationary combustion (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions from electricity (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions from district energy (kt CO2 eq) | Total from all sources (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage share of total GHG emissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 203.5 | 53.7 | 38.7 | 295.9 | 32% |

| Nova Scotia | 45.0 | 98.5 | 1.1 | 144.6 | 16% |

| Alberta | 101.9 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 106.5 | 12% |

| Quebec | 86.4 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 92.5 | 10% |

| Saskatchewan | 32.1 | 39.2 | 5.2 | 72.6 | 8% |

| British Columbia | 44.8 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 50.5 | 6% |

| New Brunswick | 25.4 | 20.8 | 0.5 | 46.7 | 5% |

| Manitoba | 31.0 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 32.5 | 4% |

| Nunavut | 22.8 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 3% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 25.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 26.7 | 3% |

| Northwest Territories | 6.0 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 9.0 | 1% |

| Prince Edward Island | 3.0 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 1% |

| Yukon | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.4% |

| Total | 630 | 234 | 51 | 917 | 100% |

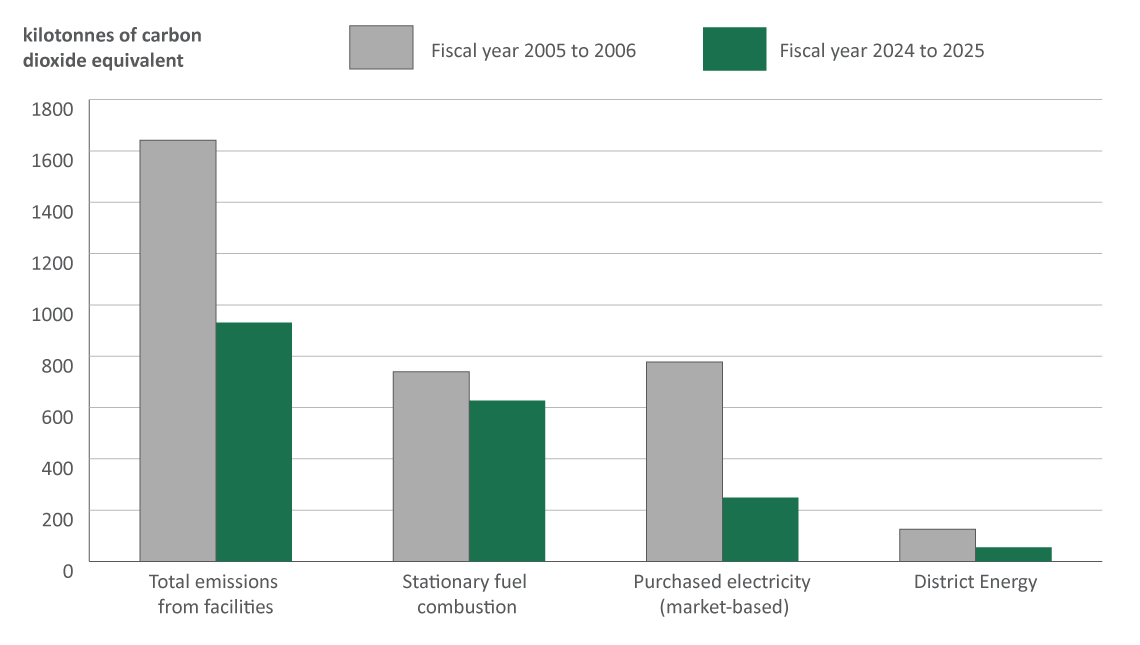

Figure 6 - Text version

The bar graph shows the GHG emissions generated by federal facilities in kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in total and by source for fiscal years 2005 to 2006 and 2024 to 2025.

| Source of Energy | Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions in for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary fuel combustion | |||

| Natural gas | 550.7 | 537.4 | -2.4% |

| Light fuel oil | 60.3 | 50.1 | -17% |

| Heavy fuel oil | 68.8 | 0.0 | -100% |

| Jet fuel | 26.8 | 20.9 | -22% |

| Diesel | 21.3 | 11.6 | -46% |

| Propane | 10.9 | 11.2 | 3% |

| Kerosene | 0.0 | 0.6 | N/A |

| Purchased electricity | |||

| Market-based | 750.9 | 234.4 | -69% |

| Location-based | 750.9 | 317.9 | -58% |

| District energy | |||

| Heating | 102.3 | 50.4 | -51% |

| Cooling | 23.7 | 0.8 | -97% |

| Facilities total (market) | 1,616 | 917 | -43% |

| Facilities total (location) | 1,616 | 1,000 | -38% |

Key results

- 26 federal organizations reported GHG emissions generated by federal facilities in fiscal year 2024 to 2025

- The emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 totaled 917 kilotonnes (kt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq) for facilities, which represents a decrease of 699 kt CO2 eq or 43.3% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the top 5 emitting organizations (National Defence, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Correctional Service Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) generated 82% of the Government of Canada’s facilities emissions

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, operations in the top 6 regions (Ontario, Nova Scotia, Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia) generated 83% of the Government of Canada’s facilities emissions

- A significant amount of emissions generated by purchased electricity comes from electricity use in regions that have high-carbon emitting electricity grids, including Nova Scotia (42%), Saskatchewan (17%), Alberta (1.1%) and New Brunswick (8.9%). Although 87% of electricity generated in Ontario is from non-emitting sources, the province still accounts for 23% of the government’s electricity emissions because it has the largest proportion of the facilities portfolio.

- Breakdown of emissions from natural gas used in federal facilities:

- 37% in Ontario

- 19% in Alberta

- 16% in Quebec

- 7% in British Columbia

- 46% of emissions from light fuel oil came from operations in Newfoundland and Labrador and an additional 35% of emissions from light fuel oil were generated in the other Atlantic provinces and Quebec

- 79% of GHG emissions from district energy came from plants located in the National Capital Region

- Stationary fuel combustion, primarily used to generate heat at facilities, was the source of a significant amount (69%) of GHG emissions in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, but has decreased by 15% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- Purchased electricity generated a significant amount (26%) of GHG emissions in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, but emissions from electricity use have decreased by 69% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006.

- The 699 kt CO2 eq reduction in emissions from federal facilities compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 can be attributed to:

- a reduction in the GHG intensity of electricity purchased across Canada, which accounted for a reduction of 350 kt CO2 eq

- contracting mechanisms, such as renewable energy certificates, which accounted for an additional reduction of 95 kt CO2 eq

- The reduction in GHG emissions from district heating (52kt CO2 eq) and cooling (23 kt CO2 eq) was significant, but it had a small impact on emission levels since district heating and cooling represents a smaller share of overall energy use

- The remaining 179 kt reduction in emissions can be attributed to the rationalization of the government’s portfolio of buildings, energy efficiency measures and fuel switching resulting in reductions of energy use in the form of:

- stationary fuel combustion (108 kt CO2 eq)

- purchased electricity (71 kt CO2 eq)

More information

Stationary fuel combustion generates heating, cooling, and electricity at federal facilities. Sources of stationary fuel combustion within facilities often include:

- boilers and furnaces to produce heat

- absorption chillers or gas-driven compression units used for cooling

- generators, turbines or co-generation equipment that produce electricity

- other equipment used in facilities, such as lab equipment and kitchen appliances

These GHG emissions are considered to be “direct” because they are generated at the facility.

Purchased electricity refers to the purchase of conventional, grid-tied electricity. GHG emissions from purchased electricity are considered to be “indirect” because the electricity is generated off-site.

Federal organizations use 2 accounting methods to calculate GHG emissions from purchased electricity:

- The location-based method considers the average GHG intensity of the electricity grids that provide electricity, regardless of any contractual arrangements that an organization has for clean electricity. To quantify indirect emissions using the location-based method, reporting organizations use emission factors that are based on the geographic location of each facility and that correspond to the grid-average emission factor of power-generating facilities that supply power to the grid.

- The market-based method reflects GHG emissions from sources of electricity that reporting organizations have chosen. For example, an organization may establish a contractual arrangement to procure clean electricity from specific sources through the use of clean power purchase agreements or renewable energy certificates. For all remaining electricity use at a facility that is not covered by a contractual arrangement, the appropriate grid-average emission factor based on the location of the facility will apply. Progress toward the federal GHG reduction target will be measured using the market-based methodology.

District energy represents the energy used for heating or cooling that is generated off-site. GHG emissions from district energy are also considered to be indirect because the emissions occur at the facility where heating or cooling is generated.

Visit the Open Government portal for more information on GHG emissions generated by federal facilities.

Fleets

Scope: 1,2

Greenhouse gas emissions generated by federal conventional fleets

Operating a fleet results in the combustion of fossil fuels and the emission of GHGs. The Government of Canada is transitioning to zero emission vehicles and has a large and diverse conventional fleet that includes:

- on-road vehicles and equipment, such as:

- cars

- vans

- trucks

- other vehicles

- off-road vehicles and equipment, such as:

- marine vessels (boats and ships)

- aircraft

- other mobile equipment (for example all-terrain vehicles, lawn mowers and generators)

Federal conventional fleets consist of vehicles and equipment primarily used to transport people and cargo in the conduct of government business, and excludes fleet used for National Safety and Security operations.

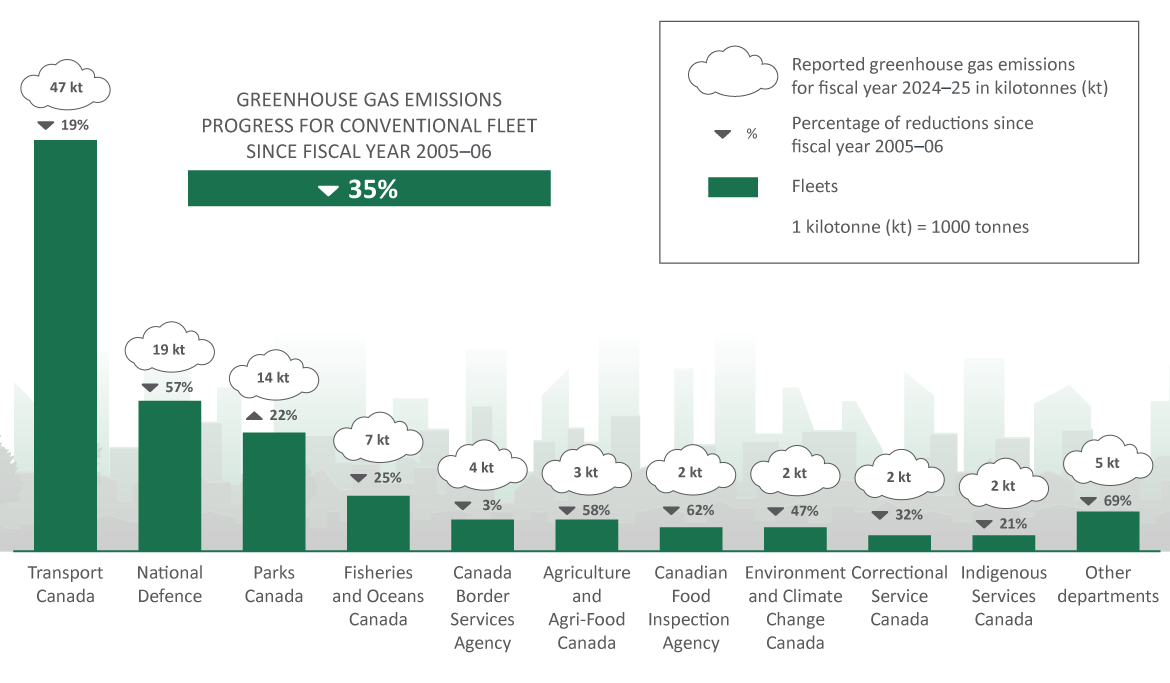

Figure 7 - Text version

The bar graph shows the total GHG emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon equivalent) reported in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, for conventional fleet by federal organization. Above each bar is the organization’s emissions in 2024 to 2025, as well as the percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 for each federal organization.

| Federal organization | Emissions from conventional fleet for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions from conventional fleet for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport Canada | 57.6 | 46.7 | -19% |

| National Defence | 43.3 | 18.5 | -57% |

| Parks Canada | 11.4 | 13.9 | 22% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 9.6 | 7.2 | -25% |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 4.4 | 4.3 | -3% |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 8.1 | 3.3 | -58% |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 6.3 | 2.4 | -62% |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 4.6 | 2.4 | -47% |

| Correctional Service Canada | 2.8 | 1.9 | -32% |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 2.2 | 1.8 | -21% |

| National Research Council Canada | 1.3 | 1.1 | -14% |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 4.2 | 0.9 | -78% |

| Natural Resources Canada | 1.7 | 0.7 | -60% |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 1.5 | 0.6 | -62% |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 1.8 | 0.6 | -64% |

| Shared Services Canada | 0.7 | 0.3 | -61% |

| Health Canada | 1.6 | 0.2 | -86% |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 1.4 | 0.2 | -88% |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 0.4 | 0.1 | -70% |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 0.08 | 0.04 | -49% |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 0.09 | 0.02 | -76% |

| Canadian Space Agency | 0.7 | 0.02 | N/A |

| Communications Security Establishment | N/A | 0.01 | N/A |

| Public Safety Canada | N/A | 0.01 | N/A |

| Total | 165 | 107 | -35% |

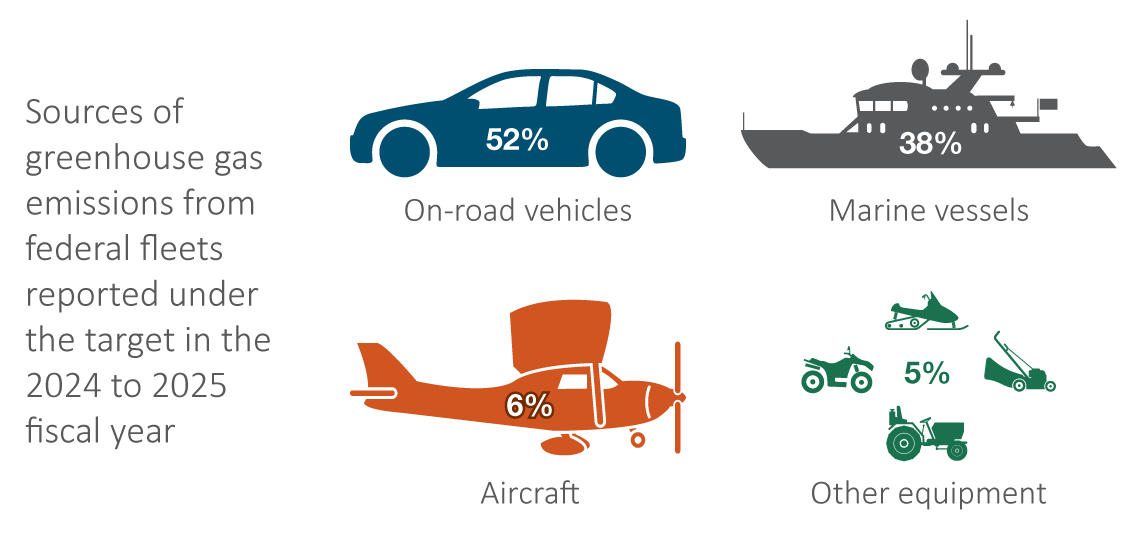

Figure 8 - Text version

The graphic shows the sources of GHG emissions from the federal fleet by vehicle type in fiscal year 2024 to 2025. From highest to lowest: on-road (50%), marine vessels (37%), aircraft (8%), and other mobile equipment (5%).

| Vehicle type | Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage of 2024 to 2025 total emissions |

|---|---|---|---|

| On road vehicles | 103 | 55 | 52% |

| Marine vessels | 36 | 41 | 38% |

| Aircraft | 16 | 6 | 6% |

| Other mobile equipment | 9 | 5 | 5% |

| Total | 165 | 107 | 100% |

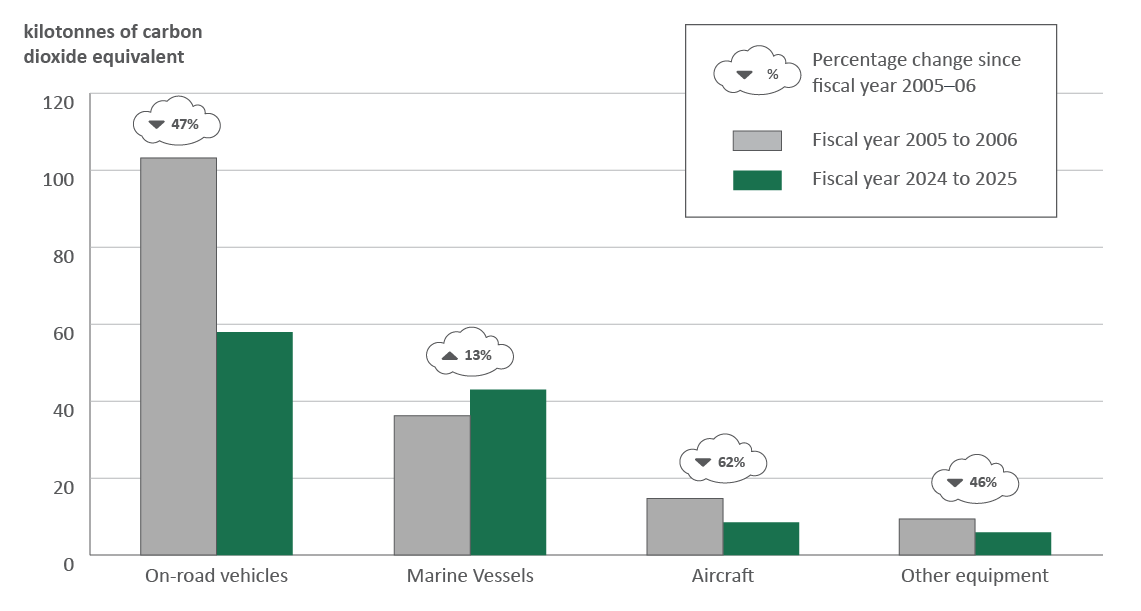

Figure 9 - Text version

The bar graph shows the GHG emissions generated by the federal conventional fleet in kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by vehicle type for fiscal years 2005 to 2006 and 2024 to 2025 and the percentage change in emissions compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006.

| Vehicle type | Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| On road vehicles | 103 | 55 | -47% |

| Marine vessels | 36 | 41 | 13% |

| Aircraft | 16 | 6 | -62% |

| Other mobile equipment | 9 | 5 | -46% |

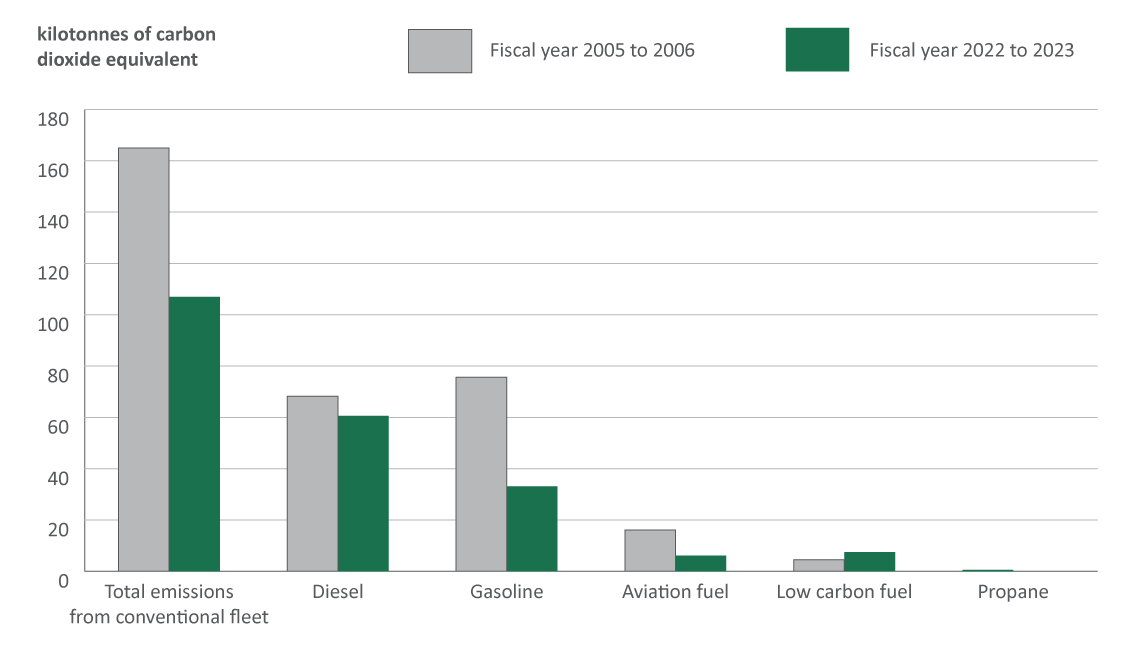

Figure 10 - Text version

The bar graph shows the GHG emissions generated by the federal conventional fleet in kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by fuel type for fiscal years 2005 to 2006 and 2024 to 2025.

| Fuel type | Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | 68.2 | 60.6 | -11% |

| Gasoline | 75.6 | 33.1 | -56% |

| Aviation fuel | 16.1 | 6.1 | -63% |

| Low carbon fuel | 4.5 | 7.5 | 66% |

| Propane | 0.56 | 0.04 | -92% |

| Total | 165 | 107 | -35% |

Key results

- 24 federal organizations reported GHG emissions generated by federal conventional fleets in fiscal year 2024 to 2025

- The emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 totaled 107 kilotonnes (kt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq) for conventional fleets, which represents a decrease of 58 kt CO2 eq or 35% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the top 5 emitting organizations (Transport Canada, National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Canada Border Service Agency) generated 85% of the Government of Canada’s conventional fleet GHG emissions

- The federal conventional fleet generated just under 11% of combined federal facilities and conventional fleet GHG emissions in fiscal year 2024 to 2025

- Half of the fleet’s GHG emissions (52%) were generated by on-road vehicles, while the balance was generated by marine vessels (38%), aircraft (6%) and other mobile equipment (5%) owned by federal organizations

- Since fiscal year 2005 to 2006, on-road vehicles have delivered both the largest absolute GHG reduction (48 kt CO2 eq) and percentage reduction (52%) within the conventional fleet. In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, GHG emissions from the federal fleet were influenced by:

- Vehicle right-sizing and the purchase of more efficient vehicles

- GHG emissions from gasoline, which were the largest source of the fleet’s emissions in 2005-06, decreasing by 43 kilotonnes (kt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq), or 56% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- GHG emissions from diesel, which were reduced by 7.6 kt of CO2 eq or 11% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006. The marine fleet accounted for 65% of emissions from diesel fuel, 30% from on-road vehicles and 5% from other mobile equipment

- GHG emissions from aviation fuel have decreased by 63% compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006

- GHG emissions from propane were reduced by 92%.

More information

Visit the Open Government portal for more information on GHG emissions generated by federal fleets.

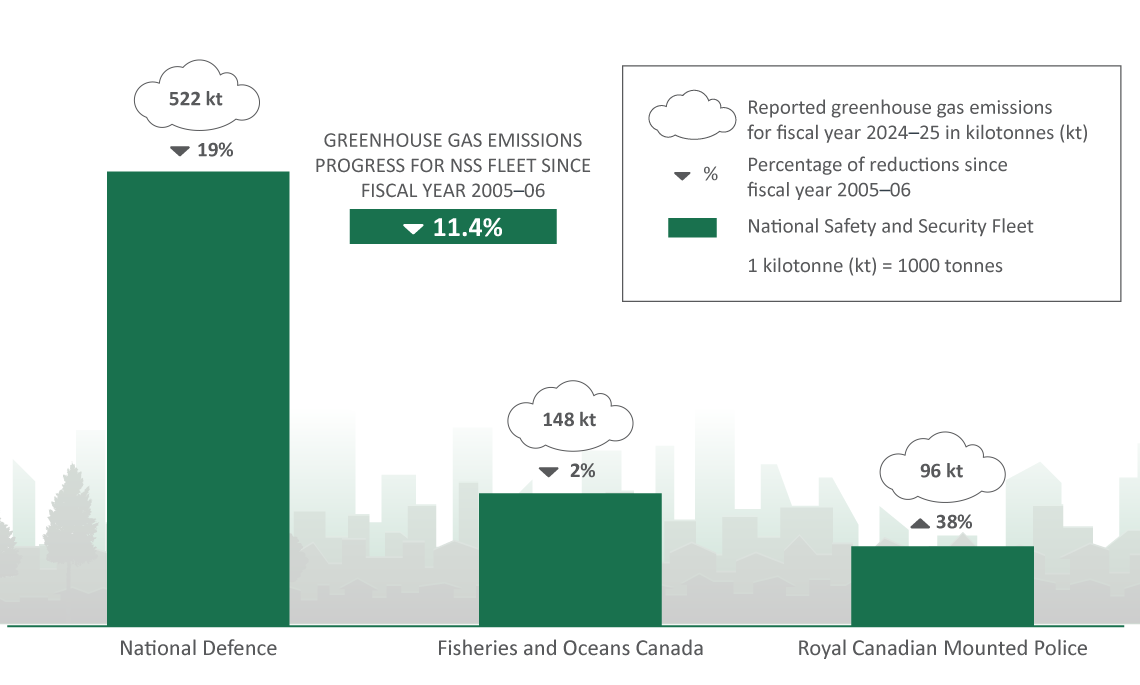

Security

Scope: 1,2

Greenhouse gas emissions from national safety and security fleet operations

National safety and security fleet (NSSF) operations include activities such as law enforcement by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, search and rescue by the Canadian Coast Guard, and the operation of military vehicles and equipment by the Department of National Defence. These emissions are included in the Government of Canada’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050Footnote 1.

Figure 11 - Text version

The bar graph shows GHG emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon equivalent) reported in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, for national safety and security fleet by federal organization. Above each bar is the organization’s emissions in 2024 to 2025, as well as the percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 for each federal organization.

| Federal organization | Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Defence | 644 | 522 | -19% |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 150 | 148 | -2% |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 69 | 96 | 38% |

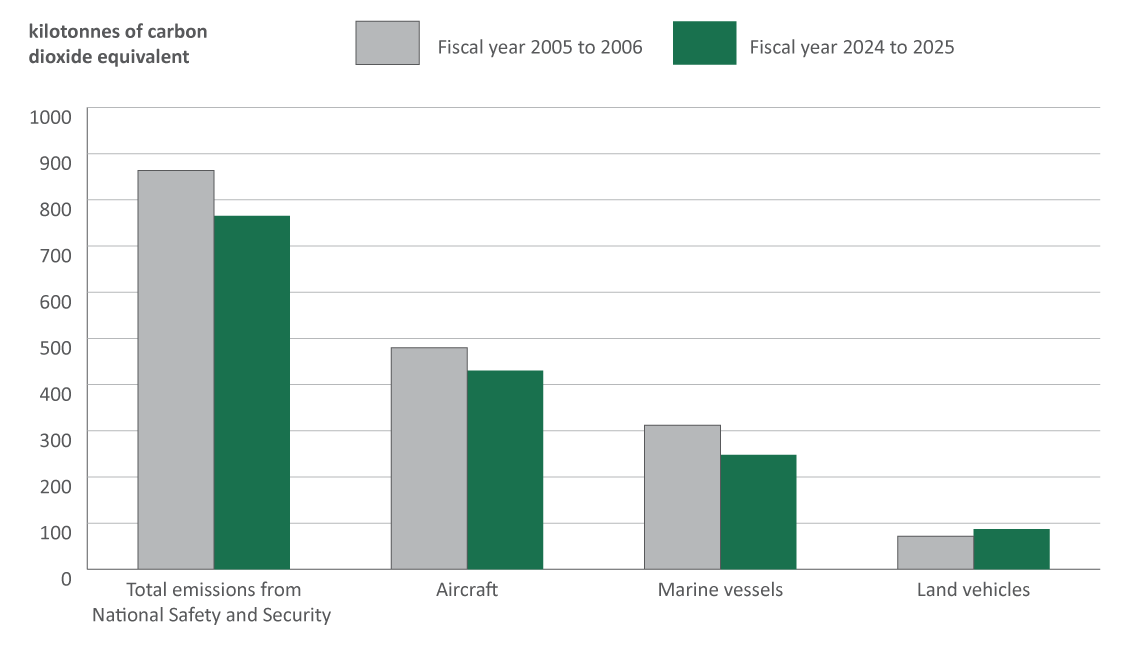

Figure 12 - Text version

The bar graph shows the GHG emissions generated by the national safety and security fleet in kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent as a total and by fleet type for fiscal years 2005 to 2006 and 2024 to 2025.

| National safety and security fleet type | Emissions for fiscal year 2005 to 2006 (kt CO2 eq) | Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) | Percentage change compared with fiscal year 2005 to 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft | 480 | 430 | -10.4% |

| Marine | 312 | 248 | -20.5% |

| Land vehicles | 72 | 87 | -21.8% |

| Total | 863 | 765 | -11.4% |

Key results

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the federal national safety and security fleet emitted 765 kilotonnes (kt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq)

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the Department of National Defence national safety and security fleet emitted 522 kt CO2 eq:

- 80% of the emissions came from aircraft

- 20% came from marine vessels

- 0.7% came from other land vehicles

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the Canadian Coast Guard national safety and security fleet emitted 147 kt CO2 eq:

- 97% of the emissions came from marine vessels

- 3% came from aircraft

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) national safety and security fleet emitted 96 kt CO2 eq:

- 88% of the emissions came from on-road vehicles. An overall 44% increase in GHG emissions since fiscal year 2005 to 2006 is attributed to a 31% increase in the number of RCMP on-road NSS vehicles. The adoption of purpose-built large SUV and pick-up trucks is required to meet operational requirements. The RCMP is currently assessing the feasibility of incorporating electric vehicles into its policing fleet to reduce the growth in GHG emissions;

- 10% came from aircraft

- 2% came from marine vessels

More information

National Safety and Security Fleet (NSSF) owning departments are developing Operational Fleet Decarbonization Plans that outline how they will reduce their emissions from operations in line with the overall 2050 target.

In addition, NSS departments will adopt best practices to improve efficiency and reduce emissions and environmental impacts in the areas of:

- fuel procurement, including low-carbon fuels

- fleet procurement, including purchasing energy -efficient platforms

- operational efficiency and net-zero research and innovation

The Government of Canada is putting itself on a 2050 net-zero pathway by committing to buy low-carbon fuels for use in the federal domestic air and marine fleets. To this end, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat is implementing a Low-Carbon Fuel Procurement Program (LCFPP) within the Greening Government Fund. The Low-Carbon Fuel Procurement Program within the Greening Government Fund provides $134.9 million in funding over eight years (fiscal years 2023–24 to 2030–31) to support this objective.

Air Travel

Scope 3

Greenhouse gas emissions from public service employee work-related air travel

Through the Greening Government Strategy, the Government of Canada made a commitment to track greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from air travel by public service employees starting in fiscal year 2018-19. These emissions are included in the federal GHG inventory and, the federal GHG reduction target for 2050.

We are also promoting lower-carbon alternatives to work-related air travel, including the use of teleconference technology or substituting air travel with other forms of travel such as rail, where feasible.

As a way to further incent departments to adopt lower-carbon alternatives to work-related travel the Greening Government Fund was established through Treasury Board Secretariat in 2018. Federal departments and agencies that generate GHG emissions in excess of 1 kilotonne per year from air travel initially contribute $50 per tonne annually (rising annually with the federal carbon pollution pricing system) to the Greening Government Fund. The fund supports projects that allow departments to explore innovative approaches and reduce GHG emissions.

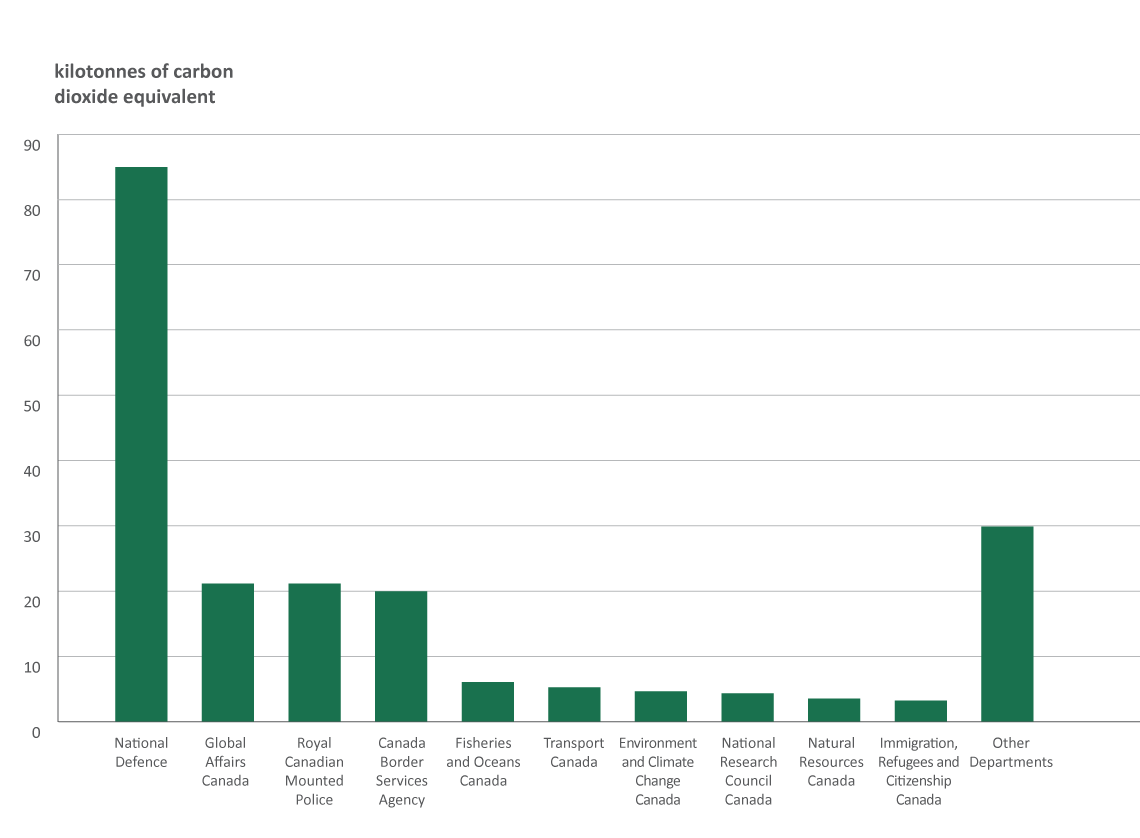

Figure 13 - Text version

The bar graph shows the total GHG emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon equivalent) for employee work-related air travel reported in fiscal year 2024 to 2025, by the top 11 emitting federal organizations. The remainder are grouped as “other”.

| Federal organization | Emissions for fiscal year 2024 to 2025 (kt CO2 eq) |

|---|---|

| National Defence | 85.3 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 21.1 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 21.1 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 19.9 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 6.0 |

| Transport Canada | 5.2 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 4.6 |

| National Research Council | 4.3 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 3.5 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 3.2 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 3.2 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 2.7 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 2.3 |

| Parks Canada | 2.0 |

| Health Canada | 1.9 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 1.9 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 1.8 |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 1.8 |

| Public Safety Canada | 1.6 |

| Justice Canada | 1.4 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 1.4 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 1.4 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 1.1 |

| Privy Council Office | 1.0 |

| Statistics Canada | 0.9 |

| Veterans Affairs Canada | 0.8 |

| Shared Services Canada | 0.8 |

| Canadian Space Agency | 0.7 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 0.6 |

| Canadian Heritage | 0.6 |

| Total | 204 |

Key results

- In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, total employee work-related air travel emissions were 204 kt and were 3% below the 2019-2020 pre-pandemic levels.

- The top 5 emitting organizations (National Defence, Global Affairs Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Border Services Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada) generated 75% of GHG emissions attributable to employee work-related air travel.

Procurement

Scope 3

Figure 13 - Text version

The graphic shows the 6 stages of the supply chain lifecycle of a good or service. Extraction is the harvesting of raw materials. Processing is the conversion of raw materials into useful materials. Manufacturing is the assembly of the product into its final form. Distribution is the transport of the product to the end user. Use refers to the use of the product by the end user. End of life refers to the fate of the product after the end user no longer needs it.

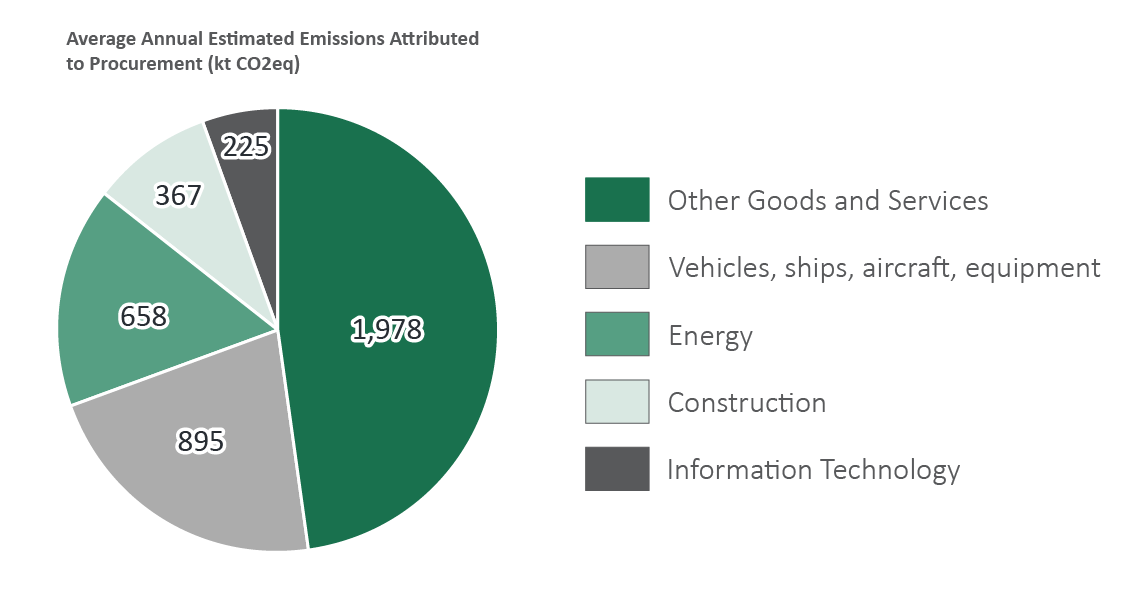

Figure 14 - Text version

The graph shows the 2016-2020 average annual estimated GHG emissions (in kilotonnes of carbon equivalent) attributable to each category of centralized procurement.

Data for the graph

| Procurement Category | Average Annual Estimated Emissions Attributable to Procurement (kt CO2 eq) |

|---|---|

| Other Goods and Services | 1,978 |

| Vehicles, ships, aircraft and equipment | 895 |

| Energy | 658 |

| Construction | 367 |

| Information Technology | 225 |

| Total | 4,124 |

More Information

CIRAIG’s analysis was captured in three reports. The first report estimated the embodied carbon footprint of goods and services procured by Public Services and Procurement Canada in Quebec. Subsequently, the same exercise was completed for the rest of Canada. As a third phase CIRAIG developed an estimate of the footprint of the government’s IT operations for Shared Services Canada.

This study evaluated the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions associated with procurement in the 5 Public Services and Procurement Canada regions, namely Pacific (British Columbia and the Yukon Territory), Western (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories), Ontario, the National Capital Region (Ottawa and Gatineau), and Atlantic (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador). It identified the procurement categories to prioritize for action based on those that generate the most greenhouse gas emissions.

Carbon footprint of purchases by Public Services and Procurement Canada – Quebec Region - CIRAIG

This study identified the procurement categories in the Public Services and Procurement Canada - Quebec region that generated the most greenhouse gas emissions.

Environmental footprint of procurement by Shared Services Canada - CIRAIG

This study builds on and extends the previous carbon footprint studies conducted in 2018 and 2019 by the CIRAIG for Public Services and Procurement Canada. The study used the same methodology to estimate the carbon footprint of Shared Services Canada’s procurement, but it was expanded to cover energy and water consumption.