Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act 2024 to 2025

Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

I am pleased to present the 18th Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act to the President of the Treasury Board for tabling in Parliament. This report provides an overview of disclosure-related activities in federal public sector organizations for the 2024-25 fiscal year.

Under the Act, every public sector organization must maintain a code of conduct aligned with the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector and establish clear mechanisms for reporting and managing disclosures of wrongdoing. Coming forward to make a disclosure of wrongdoing requires courage. The Act provides vital protections from reprisal for public servants who disclose wrongdoing in good faith.

This year’s data shows an increase in disclosures—more individual disclosures, more allegations included in these disclosures, and more cases of founded wrongdoing.

During the reporting period, the federal public service continued to emphasize values and ethics, with a range of initiatives across the federal public service and within individual departments to foster a culture grounded in ethical principles.

One of these initiatives was a two-day Values and Ethics Symposium for all federal public servants in , which resulted in a number of actions. For example, organizations reviewed their codes of conduct, implemented methods for employees to submit annual attestations on conflict of interest and added public reporting on the outcomes of other recourse mechanisms to improve transparency.

My office also continues to develop and disseminate policies, guidelines, and advice in the areas of integrity and ethics, such as the Guidance for Public Servants on their Personal Use of Social Media, which aims to balance public servants’ right to freedom of expression and the duty of loyalty of all public servants. We have also worked with the Canada School of Public Service to revise training and continue to facilitate government-wide communities of practice on internal disclosure and values and ethics. These efforts have no doubt contributed to increased awareness of values and ethics, as well as the recourse mechanisms available to public servants, including the Act.

My office is committed to promoting a positive and respectful public sector culture grounded in values and ethics. I encourage you to read this report to learn more about ongoing efforts to address wrongdoing and to advance values and ethics.

About this report

The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) provides federal public sector employees with:

- a secure and confidential process for disclosing wrongdoing in the workplace

- protection from acts of reprisal

This annual report on the Act covers the period from , to . The report contains information on disclosure activities in the federal public sector, which includes departments, agencies and Crown corporations, as defined in section 2 of the Act.

The chief executive of every organization subject to the Act is required by section 10 to:

- establish internal procedures to manage disclosures

- designate a senior officer who is responsible for addressing disclosures made by employees of the organization under the Act

Alternatively, organizations that are too small to designate a senior officer or establish their own internal procedures can have disclosures handled by the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada.

Section 38.1 of the Act requires chief executives of federal organizations to submit a report at the end of the fiscal year to the chief human resources officer on disclosures made under the Act within their organization. This report compiles the information on disclosures that organizations received. It does not contain information about:

- disclosures or reprisal complaints made to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada, which are published in the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada’s annual report

- other recourse mechanisms

- anonymous disclosures

Part 1: Organizational enquiries and disclosures

Organizations in the public sectorFootnote 1 have an internal disclosure mechanism that gives public servants three choices for making a protected disclosure. They can disclose issues to any of the following:

- their supervisor

- their organization’s senior officer for internal disclosure

- the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

An organization’s senior officer for internal disclosure helps create a positive environment for disclosing wrongdoing and handles disclosures of wrongdoing made by public servants of their organization.

It is a best practice for the senior officer for internal disclosure to regularly provide information, advice and guidance to employees about the organization’s internal disclosure procedures, including:

- how to contact the senior officer to make enquiries and make disclosures

- how investigations are handled

- how disclosures made to a supervisor should be brought to the senior officer’s attention

The senior officer should also provide information on how the identity of an employee making a disclosure and others involved will be protected.

Enquiries

Public servants are encouraged to contact the senior officer for internal disclosure in their organization when they need information about the disclosure process or have questions. They can do this without officially reporting a disclosure or allegation.

In the 2024–25 fiscal year, public sector organizations reported that 398 enquiries were made about the Act. This is an increase from the 279 enquiries reported in 2023–24.

Disclosures and allegations of wrongdoing

When a public servant or a group of public servants gives information to their supervisor or senior officer for internal disclosure about possible wrongdoing in the public sector, they are making an internal protected disclosure.Footnote 2

A single disclosure may contain one or more allegations. An allegation refers to the communication of a possible instance of wrongdoing as defined in section 8 of the Act. An allegation must be made in good faith, and the person making it must have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true.

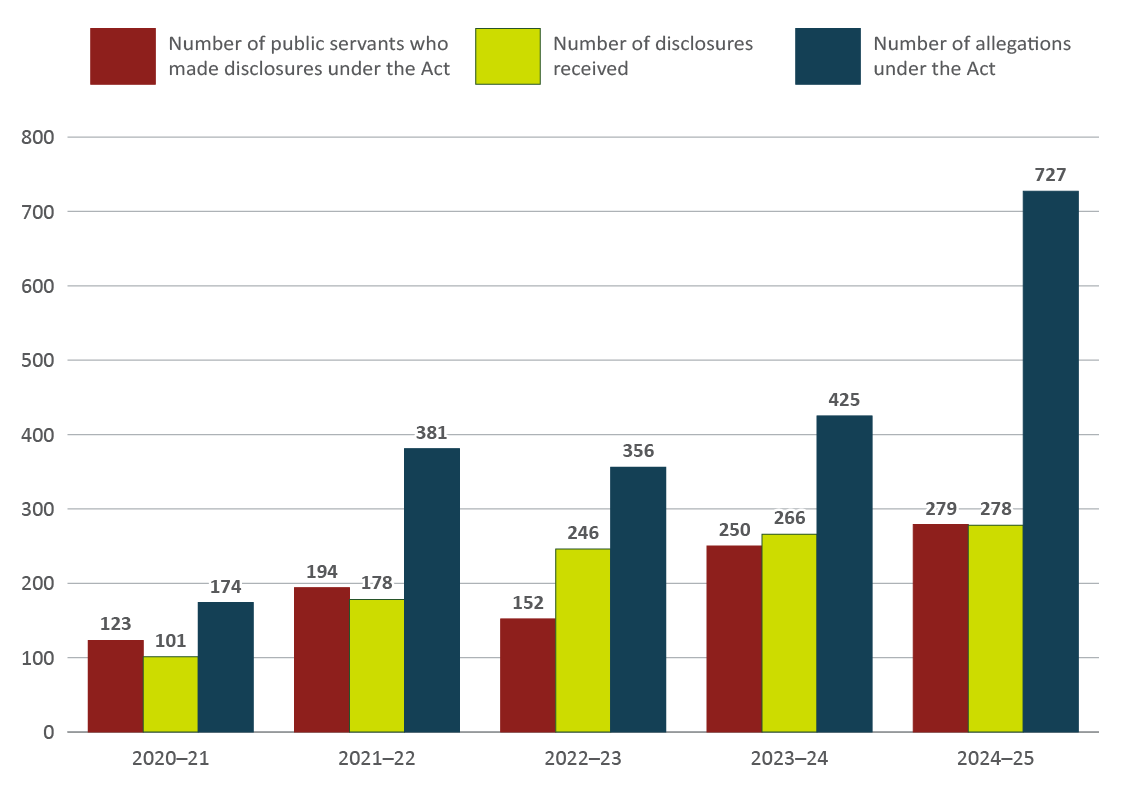

The following chart (Figure 1) depicts five years of data on the number of public servants who have come forward with a protected disclosure of wrongdoing, the resulting number of disclosures, and the number of allegations received in these disclosures.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Type | 2020-21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of public servants who made disclosures under the Act | 123 | 194 | 152 | 250 | 279 |

| Number of disclosures received | 101 | 178 | 246 | 266 | 278 |

| Number of allegations under the Act | 174 | 381 | 356 | 425 | 727 |

In 2024–25, 279 public servants made 278 internal disclosures that encompassed 727 allegations of wrongdoing. In the previous year, 250 public servants made 266 internal disclosures concerning 425 allegations of wrongdoing. Although allegations of wrongdoing have increased from the previous year, the number of public servants who have come forward with a protected disclosure of wrongdoing increased by a little more than 10%. The significant increase in allegations of wrongdoing could point to more allegations being made within disclosures but could also be related to enhanced record keeping or reassessment of disclosures.

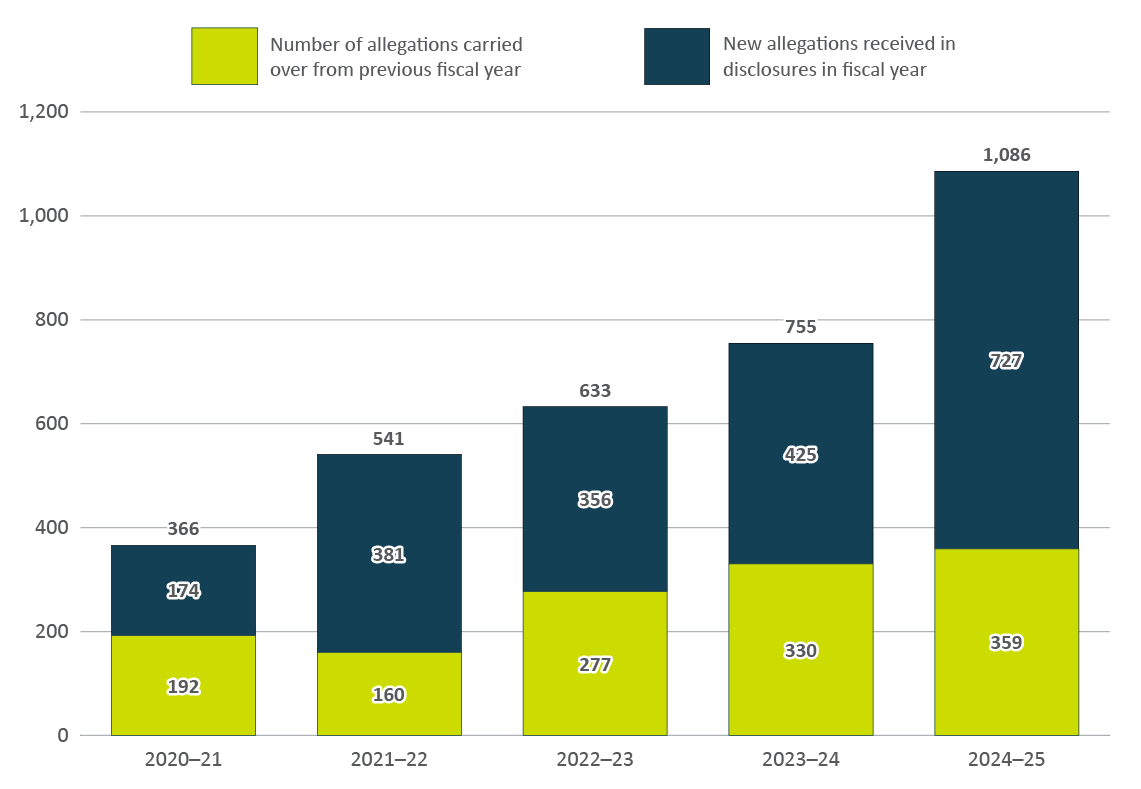

Allegations carried forward from previous years

Depending on the complexity and volume of allegations received in any given year, organizations may carry forward some allegations into the next years before they are resolved. Allegations that do not reach a conclusion by are not considered as “acted on” and are reported as being carried forward into the next fiscal year.Footnote 3

Figure 2 - Text version

| Type | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of allegations carried over from previous fiscal year | 192 | 160 | 277 | 330 | 359 |

| New allegations received in disclosures in fiscal year | 174 | 381 | 356 | 425 | 727 |

| Total | 366 | 541 | 633 | 755 | 1086 |

As shown in Figure 2, in 2024–25, there was an increase in the number of allegations carried over from the previous fiscal year, from 330 in 2023–24 to 359 allegations in 2024–25, which is in keeping with the increase in disclosures.

Federal organizations reported that delays in handling allegations (assessing, investigating and reporting) are often associated with:

- difficulties in finding a qualified investigator

- having to postpone interviews with disclosers or witnesses due to extended leave or other factors

These circumstances result in longer process times and allegations being carried over to the next fiscal year.

Preliminary analysis of allegations

Of the 1,086 total allegations that were active in 2024–25, which include allegations carried over from previous fiscal years and those newly received during 2024–25, 727 (67%) were assessed in 2024–25. The 2024–25 rate of assessment is higher than that of the previous year, during which 56% (425 of 755 total allegations) were assessed.

The total number of allegations assessed in a fiscal year continues to rise year over year.Footnote 4.

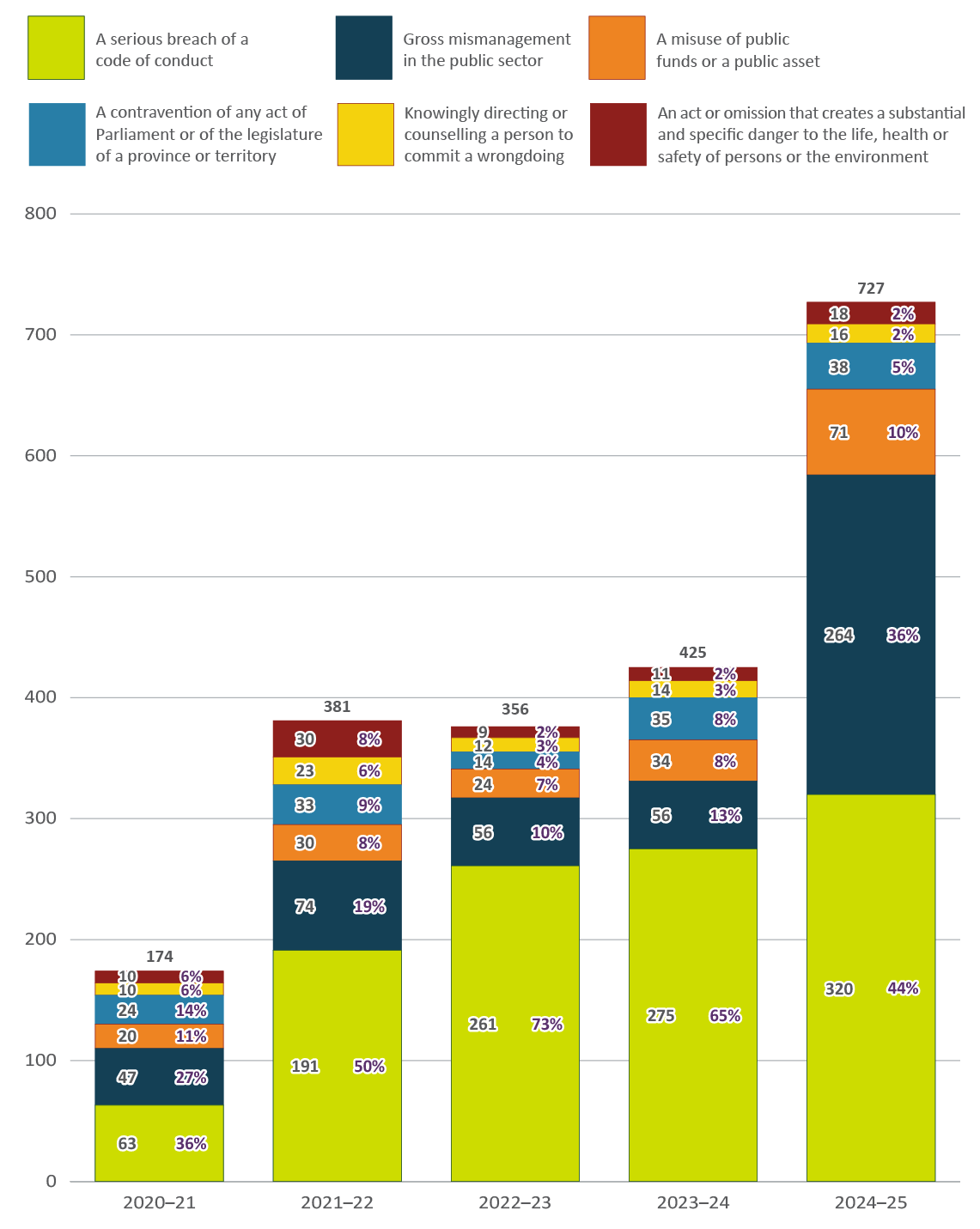

Breakdown of allegations assessed in 2024–25

When a disclosure of wrongdoing is received, the organization’s senior officer for internal disclosure conducts a preliminary analysis to determine whether the allegation or allegations meet the Act’s definition of wrongdoing and categorizes the allegation by type of wrongdoing.

Each allegation is categorized under one of the six types of wrongdoing specified in section 8 of the Act (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Text version

| Type | 2020-21 | 2020-21 (%) |

2021-22 | 2021-22 (%) |

2022-23 | 2022-23 (%) |

2023-24 | 2023-24 (%) |

2024-25 | 2024-25 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A serious breach of a code of conduct | 63 | 36 | 191 | 50 | 261 | 73 | 275 | 65 | 320 | 44 |

| Gross mismanagement in the public sector | 47 | 27 | 74 | 19 | 56 | 10 | 56 | 13 | 264 | 36 |

| A misuse of public funds or a public asset | 20 | 11 | 30 | 8 | 24 | 7 | 34 | 8 | 71 | 10 |

| A contravention of any act of Parliament or of the legislature of a province or territory | 24 | 14 | 33 | 9 | 14 | 4 | 35 | 8 | 38 | 5 |

| Knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing | 10 | 6 | 23 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 16 | 2 |

| An act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons or the environment | 10 | 6 | 30 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 18 | 2 |

| Total | 174 | 100 | 381 | 100 | 356 | 100 | 425 | 100 | 727 | 100 |

Of the 727 allegations assessed in 2024–25, 320 were categorized as a serious breach of a code of conduct. This represents an increase of 16% when compared to 2023–24 (275 allegations). However, in 2023–24, a serious breach of a code of conduct represented 65% of total allegations, whereas in 2024–25, it represented only 44%.

In 2024–25, the number of allegations categorized as gross mismanagement (264) in the public sector increased by 370% when compared to 2023–2024 (56). The number of allegations categorized as a contravention of any act of Parliament or of a provincial or territorial legislature increased by 9% in 2024–25.

Part 2: Allegations active in 2024–25

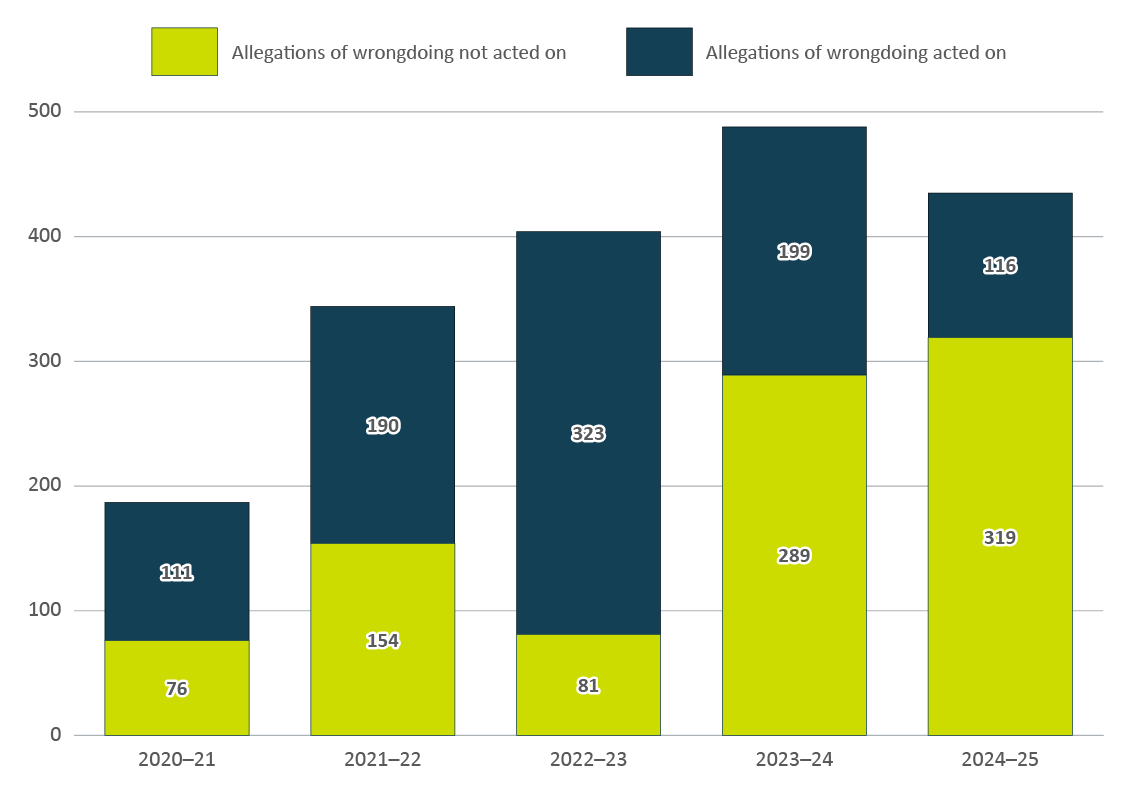

Organizations determine whether to “act on” or “not act on” an allegation based on criteria set out in section 8 of the Act.

“Acted on” means taking any steps to determine whether wrongdoing has occurred, including preliminary analysis (fact-finding) or investigation. It also means that a conclusion of the disclosure (whether the wrongdoing occurred or not) was made during the reporting period (, to ).

Figure 4 illustrates the number of allegations that were acted on or not acted on from 2020–21 to 2024–25.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Type | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations of wrongdoing not acted on | 76 | 154 | 81 | 289 | 319 |

| Allegations of wrongdoing acted on | 111 | 190 | 323 | 199 | 116 |

Of the 1,086 allegations received and carried forward from 2023–24, in 2024–25, 116 were acted on under the Act. Of these allegations:

- 30 were received in 2024–25

- 39 were received in 2023–24

- 47 were received in 2022–23 or earlier

“Not acted on” refers to any decision not to proceed with allegations of wrongdoing after the disclosure is received because of one of the following:

- it was determined that the allegations should be dealt with under a more appropriate recourse mechanism

- the allegations did not meet the definition of “wrongdoing” in the Act

- another reason

Of the 1,086 allegations received and carried forward from 2023–24, in 2024–25, 319 (73%) were not acted on under the Act. Of these allegations:

- 276 were received in 2024–2025

- 41 were received in 2023–24

- 2 were received in 2022–23 or earlier

Reasons allegations were not acted on

In 2024–25, 319 allegations were not acted on under the Act. Figure 5 illustrates how they were handled.

Figure 5 - Text version

| Type | 2020-21 | 2020-21 (%) |

2021-22 | 2021-22 (%) |

2022-23 | 2022-23 (%) |

2023-24 | 2023-24 (%) |

2024-25 | 2024-25 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred to the harassment and violence complaint process provided for under the Canada Labour Code | 17 | 22 | 35 | 23 | 30 | 37 | 37 | 13 | 36 | 11 |

| Not referred to an official recourse process | 21 | 27 | 28 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 101 | 34 | 172 | 54 |

| Referred to the grievance process provided for under the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act | 3 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 5 | 36 | 11 |

| Referred to the staffing complaint process provided for under the Public Service Employment Act | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Referred to the official languages complaint process provided for under the Official Languages Act | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Referred to the human rights complaint process provided for under the Canadian Human Rights Act | 9 | 12 | 28 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 13 | 4 |

| Referred to the privacy complaint process provided for under the Privacy Act | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Other action taken | 24 | 30 | 49 | 32 | 15 | 18 | 126 | 43 | 56 | 18 |

| Total | 76 | 100 | 154 | 100 | 81 | 100 | 294 | 100 | 319 | 100 |

A total of 29% of the 319 allegations were referred to a legislative recourse mechanism, as listed in Figure 5.Footnote 5 There was a 125% increase in referrals to the grievance process in 2024–25 compared to the previous year. However, the total number of referrals remained stable from the previous year.

There are many other recourse mechanisms available to organizations for referral outside of those that are legislated, and organizations have increased their use of these by 70%. They categorize many of the allegations as follows:

- not meeting the definition of wrongdoing and not referred to a recourse process as listed above (172, or 54%)

- other action taken such as a recommendation to speak with their manager, the Ombuds, a values and ethics advisor and/or referred to the Employee Assistance Program (56, or 18%)

Organizations indicated that they put allegations in the category of “not meeting the definition of wrongdoing and not referred to a listed recourse process” when:

- not enough information was received, and no additional information was provided by the discloser

- too much time had passed since the alleged wrongdoing had taken place

- there were misunderstandings and miscommunications that could be better handled by informal conflict management systems and management

- possible ethical or conflict of interest issues were involved that could be better handled by their manager and a values and ethics advisor

- an issue could be better resolved through the organization’s Ombuds office

- the discloser required support through the Employee Assistance Program

- the subject matter was found to be frivolous, malicious or vexatious

Organizations reported that “other action was taken” for reasons such as:

- the issue was resolved informally

- the discloser was referred to security or a financial authority or the Public Sector Integrity CommissionerFootnote 6

Allegations carried forward to the next year

Allegations are carried forward to the next year when the conclusion (i.e., to act on or not and subsequent outcomes, including a finding of wrongdoing) is not made before . Organizations reported that they carried forward 651 allegations into 2025–26. Given the increase in allegations received in 2024–25 (727) vs. the previous year (425), it is reasonable that a higher volume of allegations would be carried forward.

Part 3: Investigations, findings and corrective measures

The senior officer for internal disclosure is responsible for managing investigations into allegations of wrongdoing, including deciding whether to:

- handle an allegation under the Act

- start or stop an investigation

Senior officers must also report the following directly to their chief executive:

- any findings of investigations or systemic problems that could lead to wrongdoing

- any recommendations for corrective action

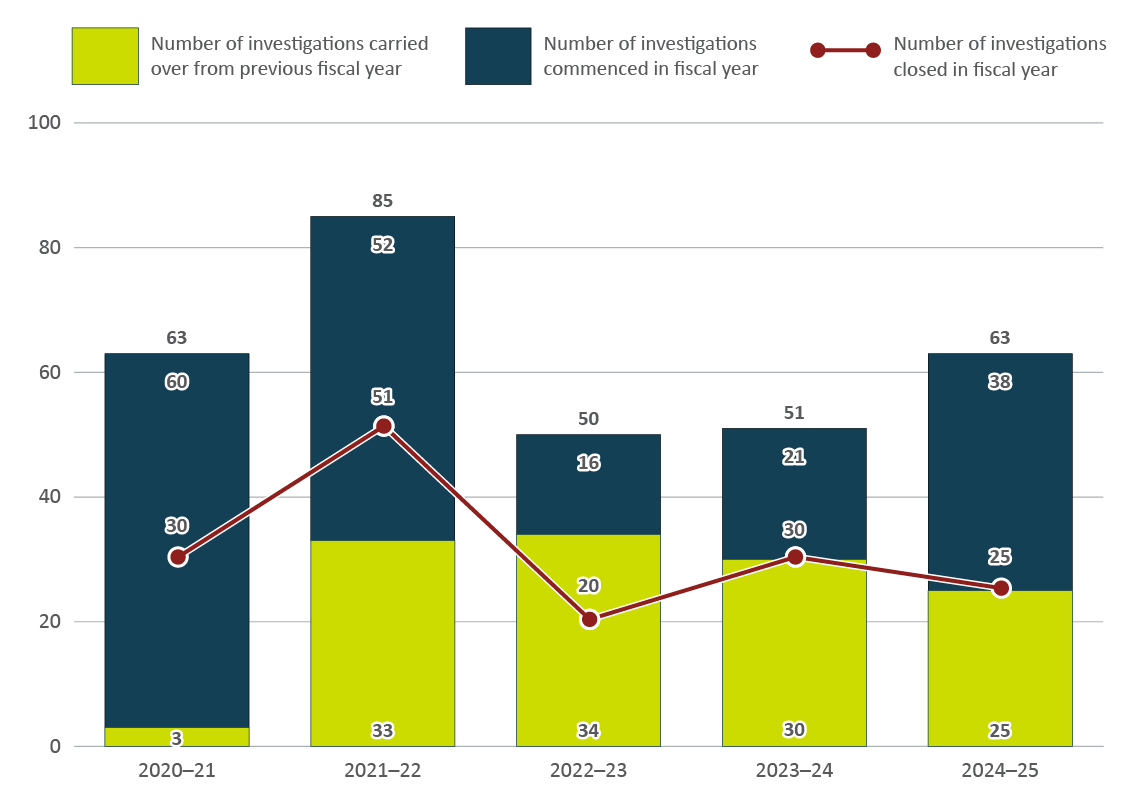

Investigations

An investigation looks at all relevant evidence and witness testimony to decide whether a disclosure is founded, based on a balance of probabilities. An investigation can examine one or more allegations. If the preliminary analysis does not lead to a formal investigation, it is not counted as an investigation; however, preliminary analyses can still lead to a finding of wrongdoing and/or corrective measures (view Figure 6).

Organizational investigations can be handled by investigators on staff or hired through a National Master Standing Offer (NMSO).

Figure 6 - Text version

| Type | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of investigations carried over from previous fiscal year | 3 | 33 | 34 | 30 | 25 |

| Number of investigations commenced in fiscal year | 60 | 52 | 16 | 21 | 38 |

| Total investigations | 63 | 85 | 50 | 51 | 63 |

| Number of investigations closed in fiscal year | 30 | 51 | 20 | 30 | 25 |

In 2024-25, 63 investigations were launched or underway, which is an increase compared to the 51 investigations that were launched or underway in 2023-24. By , 25 investigations were closed. This is five fewer than were closed in the previous year.

There were 38 investigations still ongoing at the end of 2024-25, which will continue into 2025-26.

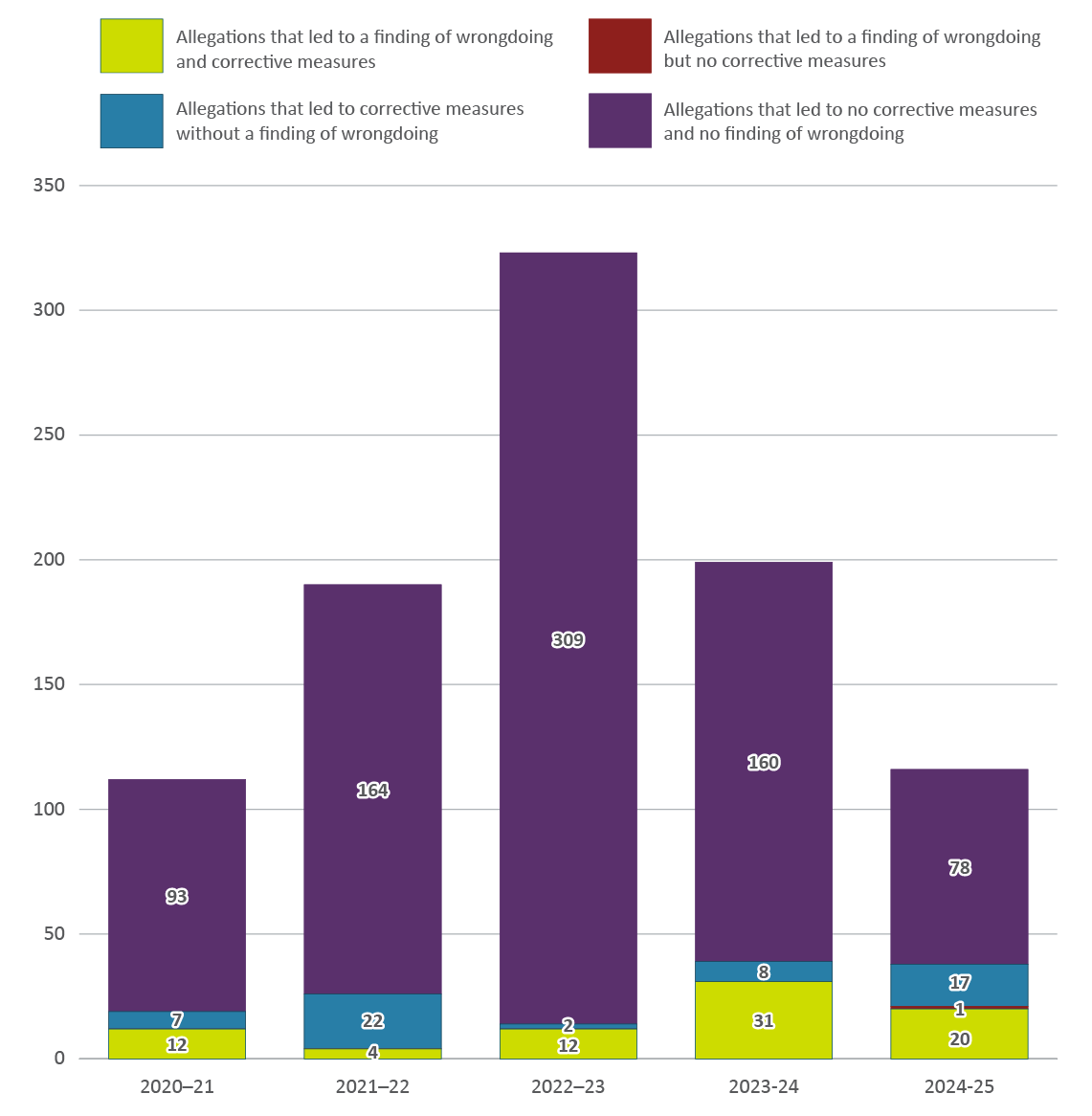

Findings of wrongdoing and corrective measures

Investigations can lead to findings of wrongdoing and corrective measures, corrective measures without a finding of wrongdoing, a finding of wrongdoing without corrective measures, or no finding of wrongdoing and no corrective measures.

Figure 7 - Text version

| Type | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | 12 | 4 | 12 | 31 | 20 |

| Allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing but no corrective measures | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 0 | 1 |

| Allegations that led to corrective measures without a finding of wrongdoing | 7 | 22 | 2 | 8 | 17 |

| Allegations that led to no corrective measures and no finding of wrongdoing | 93 | 164 | 309 | 160 | 78 |

In 2024-25, the 25 investigations that were closed by , examined 38 allegations that resulted in the following:

- 20 allegations led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measuresFootnote 7

- 17 allegations led to corrective measures without a finding of wrongdoing

- 1 allegation led to a finding of wrongdoing but no corrective measures

Of the 116 allegations acted on, 78 led to no finding of wrongdoing and no corrective measures.

On average, investigations took 191 workdays to complete.

Part 4: Education and awareness activities

This year, with the Clerk of the Privy Council’s continued focus on values and ethics, various activities have been undertaken across the federal public service and within individual government organizations to promote a values-based, ethical culture. These activities have likely had an impact on general awareness of the Act among public servants.

In collaboration with Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS), the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS) and the Privy Council Office (PCO) hosted a Values and Ethics symposiumFootnote 8 on and 16, inviting public servants to explore how the public service has been:

- reinvigorating the commitment to public service values and ethics

- how it links to the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service

- what it means in our day-to-day work

- how to position for the future

The Values and Ethics Learning Path was expanded to showcase recordings from the symposium and useful tools such as:

- webcasts and job aids

- a values and ethics discussion toolkit for scenario-based team conversations

- links to foundational and complementary training

- links to the updated Values Alive: Discussion Guide to the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector

In 2024–2025, federal public sector organizations worked in response to the Clerk’s requests by:

- updating their code of conduct

- producing a report on misconduct and wrongdoing within their organization

- developing methods for their employees to submit annual attestations on conflict of interest

- embedding consequential accountability for progress in advancing the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service through the year’s performance cycle

In addition to producing the report on misconduct and wrongdoing by spring 2025, organizations used various methods to raise awareness of the role of their senior officer for internal disclosure, the Act, and the protections it affords public servants. Common methods in order of frequency included:Footnote 9

- Videos, presentations and town hall meetings

- Posters, training and information sessions

- Emails, newsletters, workshops

- Brochures, intranet articles, and social media posts

- Bulletins and frequently answered questions (FAQs)

Part 5: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities to support ethical workplaces

Integrity and ethics

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) acts as the focal point for driving people management excellence across the federal public service. As part of this mandate, it develops and disseminates policies, guidelines, and guidance in the areas of integrity and ethics in order to promote an ethical and healthy workplace. As it pertains to this report, the policies, programs and initiatives of OCHRO that are described below contribute to fostering a workplace environment where public servants are aware of the resources available for addressing workplace issues and feel comfortable coming forward with enquiries or allegations of possible wrongdoing.

It is also OCHRO’s role to support the implementation and administration of the Act, the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector and the Directive on Conflict of Interest, and to support the President of the Treasury Board in their responsibility under the Act to promote ethical practices across the public sector.

Senior officers and communities of practice

OCHRO’s policy centre engages with the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner, the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal, public sector organizations, senior officers for internal disclosure, international organizations, bargaining agents and other stakeholders with an interest in integrity and ethics in the federal public sector workplace.

In particular, OCHRO facilitates government-wide communities of practice by disseminating information and hosting meetings of the Interdepartmental Network on Internal Disclosure (INID) and the Interdepartmental Network on Values and Ethics (INVE). These meetings allow for discussion and collaboration on values and ethics, ethical leadership, fostering a healthy workplace culture, managing ethical risks such as conflict of interest, and promoting integrity within the public sector. The INID meetings provide an opportunity for sharing strategies and recent developments in the disclosure of wrongdoing, reprisal protection and related topics.

Other activities

Working with the CSPS, OCHRO’s policy centre is updating the mandatory “Values and Ethics Foundations” courses for employees and managers. The centre also developed Guidance for Public Servants on their Personal Use of Social Media, which contains values-based guidance for public servants on balancing their freedom of expression and the duty of loyalty of public servants.

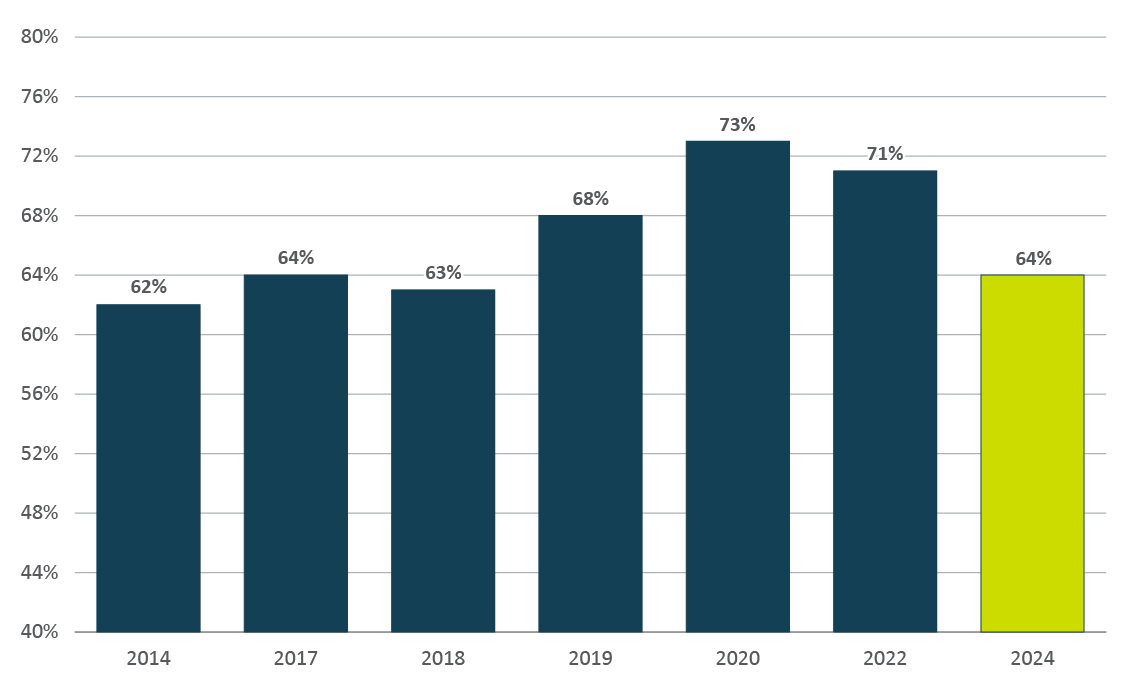

Public Service Employee Survey: ethics in the workplace

To inform, support and strengthen people management in the federal public service and other practices in government, OCHRO conducts the Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) every two years. A total of 186,635 employees in 93 federal departments and agencies responded to the most recent PSES, which gathered responses from , to .

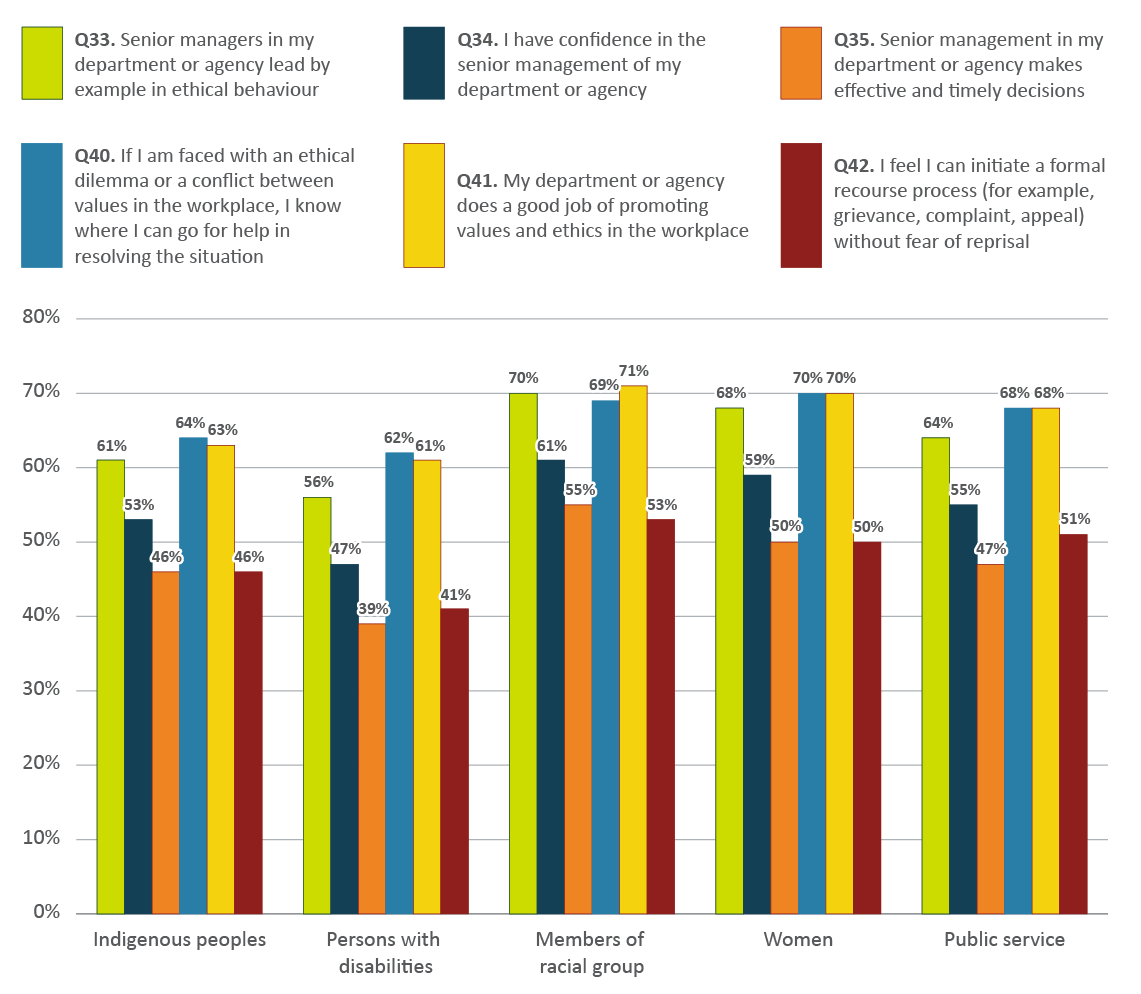

The PSES includes questions that gauge public servants’ perceptions of the ethical environment in their workplace, and its results provide insights into how equipped public servants feel to address values and ethical dilemmas. Results of the questions on ethics were analyzed by disaggregating the data by:

- employment equity group

- racial group

- province and territory

- employment community

- organizational mandate

Key results related to values and ethics in the workplace from the 2024 PSES:

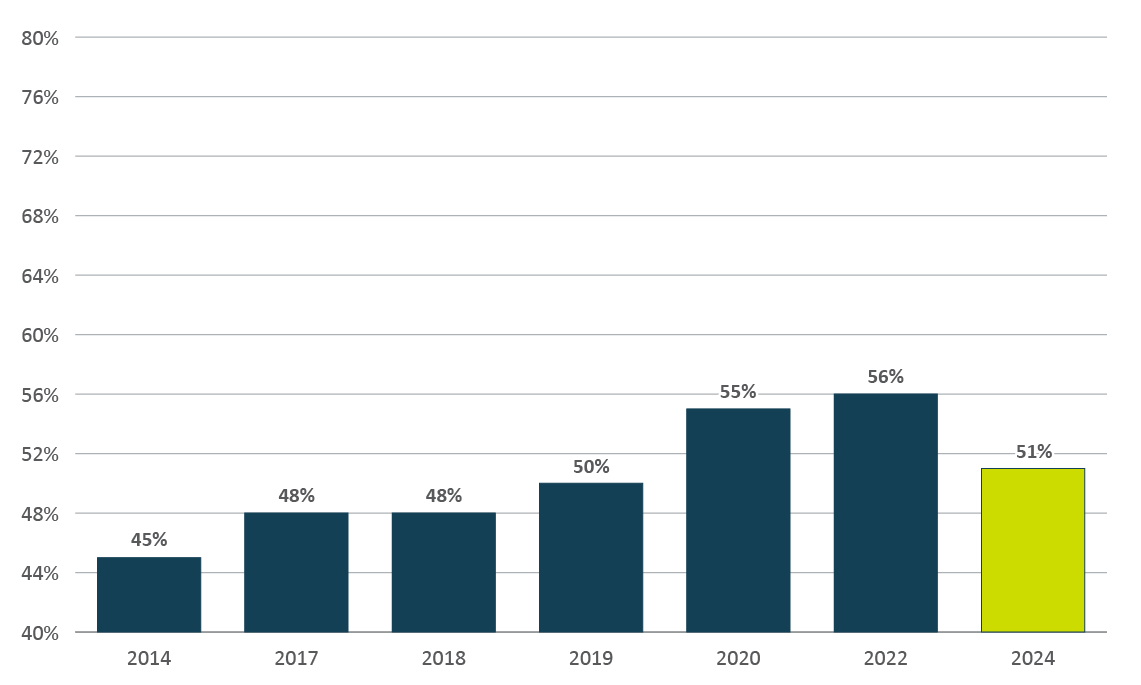

- Five of the six questions relating to values and ethics in the workplace have seen declines since 2019. For the remaining question, in 2019, 50% of respondents felt they could initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. Positive responses increased to 55% in 2020 and 56% in 2022 before declining to 51% in 2024.

- Persons with disabilities consistently reported the lowest results on all six questions in comparison to other employment equity groups

- 68% of public servants indicated that they would know where to go for help in resolving a situation if faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace. The security employment community is an outlier here, with 51% responding positively to this question

- 68% of public servants indicated that they felt that their department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. Some of the highest results are found in the Atlantic provinces (New Brunswick (74%), Nova Scotia (68%), Prince Edward Island (74%), and Newfoundland and Labrador (76%))

- 51% of public servants indicated that they felt they could initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint or appeal) without fear of reprisal. This indicator has declined after reaching a 10-year high of 56% in 2022. Some of the employment demographic groups reporting higher scores include Information Technology at 59%, Access to Information and Privacy and Client Contact Centre at 58%. As much as 58% of employees in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island also responded positively to this question

Appendix B provides further details on PSES results on ethics in the workplace.

Diversity and inclusion in the workplace

A public service that is diverse, equitable and inclusive is essential for a workplace culture where all public servants, including employees from equity-seeking groups, can feel comfortable disclosing wrongdoing. To improve workplace culture and support culturally safe workplaces where employees feel comfortable disclosing wrongdoing, OCHRO advanced efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in 2024–25. Initiatives and activities included:

- collecting and disseminating disaggregated enterprise data on the composition and experience of employment equity groups and subgroups while continuing to develop a modernized self-identification approach to provide data on the representation of employment equity groups and to foster an inclusive workplace

- conducting a TBS-Public Service Alliance of Canada Joint Review of diversity and inclusion training programs and informal conflict resolution systems

- promoting the Maturity Model on Diversity and Inclusion as an optional self-assessment tool informing organizations on progress in five dimensions of diversity and inclusion

Some notable projects include the development of guidance on:

- assessing inclusive and anti-racist behaviours in performance management

- consequential accountability

- establishing performance indicators to measure and report on inclusion outcomes

OCHRO also continued to engage with enterprise-wide equity-seeking networks and manage enterprise-wide initiatives to raise awareness and address barriers faced by equity-seeking employees such as

- the Mosaic Development Program

- the Mentorship Plus Program

- the Federal Speakers’ Forum on Lived Experience

The Action Plan for Black Public Servants

The Action Plan for Black Public Servants (Action Plan) initiatives aim at establishing career development initiatives and mental health supports for Black public servants. The Task Force for Black Public Servants oversees the development and implementation of the Action Plan. In 2024–2025, the Task Force for Black Public Servants made significant progress implementing the Action Plan including:

- The Black-centric enhancements to the Employee Assistance Program, delivered by Health Canada, has increased the number of mental health professionals in its network who self-identify as Black from 43 to 103, as of

- The first 2 cohorts of the Executive Leadership Development Program, led by the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS), started the program in and graduated in

- Following the success of the career counselling and coaching for Black public servants’ initiative, led by the Public Service Commission of Canada, the initiative was expanded in winter 2025 to enable more Black public servants to access these services

- The Second Official Language Training Initiative for Black Public Servants, led by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), launched in winter 2025

Preventing and resolving harassment and violence in the workplace

Creating a workplace free from harassment and violence is essential for public servants to report concerns or allegations of wrongdoing without fear of retaliation. The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) is dedicated to supporting public service organizations in preventing and addressing workplace harassment and violence. This is achieved through the implementation of Part II of the Canada Labour Code (CLC), the Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations (the Regulations) and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s (TBS Directive on the Prevention and Resolution of Workplace Harassment and Violence (the Directive).

The Occupational Health and Safety Centre of Expertise (OHS CoE) at OCHRO actively engages with the OHS Community of Practice (CoP) and the Designated Recipients (DR) CoP. To support these communities, the OHS CoE:

- responds to hundreds of inquiries

- offers advice and guidance on the application of the Regulations and the Directive

- organizes knowledge transfer discussions

- participates in public service–wide learning events

- leads the development of related training and tools

Key initiatives include:

- Quality Assurance Guide: Developed to establish high standards in managing harassment and violence investigations, while safeguarding employees’ rights and fostering a healthy, respectful work environment

- GCXchange platform: Established to facilitate information sharing and enhance collaboration within both CoPs

The OHS CoE also collaborates with the mental health team. For example, it co-developed the Pathways to Success tool, which aims to:

- update and clarify existing guidance

- provide additional support where required

- improve the user-friendliness of the guide: Building Success: A Guide to Establishing and Maintaining a Psychological Health and Safety Management System in the Federal Public Service

The OHS CoE leverages various monitoring tools to track progress, identify trends and pinpoint areas requiring support. It compiles each organization’s annual harassment and violence occurrence report, produced annually since 2021.

OCHRO also works closely with key stakeholders, including bargaining agents through the National Joint Council, to prevent workplace harassment and violence. Recently developed and published resources include:

- the Employee Guide

- the Employer Guide

- a FAQ providing clarification on appointing investigators and conducting investigations in alignment with the Regulations

Mental health in the workplace

Workplace environments that prioritize psychological health and safety help prevent harm, build trust and create conditions for employees to feel supported and heard. This, in turn, leads to higher levels of employee engagement and enhances public servants’ confidence in coming forward with concerns about wrongdoing. To foster positive mental health in the workplace, OCHRO co-leads the joint Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace with the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). The centre works to support departments in aligning with the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace and implementing the objectives of the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy.

In 2024–25, key resources developed or updated and promoted by the centre included:

- PSAC and TBS’ Joint Study on Mental Health Support Mechanisms for Employees who are exposed to risks of trauma as part of their duties at work

- enhancements to the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Dashboard, a statistically validated tool that assists organizations in measuring psychological health and safety strengths and gaps

- resources on the centre’s site, including those available to support employees, managers and executives

- a promising practices repository available to federal public service organizations

International engagement

In 2024–25, OCHRO continued to collaborate with international bodies and organizations to promote global integrity and address corruption. Through these international engagements, OCHRO stays updated and involved in global activities, research and sharing of knowledge on integrity, accountability, anti-corruption, and best practices on disclosure regimes around the world. OCHRO’s involvement also allows for promoting Canada’s practices, approaches and strategies. International engagements that occurred during the 2024–25 fiscal year included Canada’s participation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Working Party on Public Integrity and Anti-Corruption (PIAC), through which OCHRO contributes to strengthening public sector governance and safeguarding the integrity of public policymaking.

Appendix A: Summary of Disclosure-Related Organizational Activities

Subsection 38.1(1) of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) requires chief executives to prepare a report on the activities related to disclosures made in their organizations and to submit it to the Chief Human Resources Officer within 60 days of the end of each fiscal year. The information and statistics presented here are based on those reports.

Statistics from the previous four fiscal years are also provided below for the purpose of comparison. Although these statistics provide a snapshot of internal disclosure activities under the Act, it is difficult to draw conclusions because of the variety of organizational cultures within the public sector. For example, employee concerns or issues may be referred through different recourse mechanisms and processes in different organizations.

Although the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) and Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) are excluded from the Act by virtue of section 52, they were required to establish their own procedures for managing internal disclosures and protecting disclosers from reprisal. The Treasury Board was responsible for approving these procedures as being similar to those set out in the Act. CSIS’s procedures were approved in , CSEC’s procedures were approved in , and the CAF’s procedures were approved in .

A.1 Disclosure activity from 2020–21 to 2024–25

| General enquiries | 2024–25 | 2023–24 | 2022–23 | 2021–22 | 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of general enquiries related to the Act | 398 | 279 | 315 | 384 | 172 |

| Disclosure activity | 2024–25 | 2023–24 | 2022–23 | 2021–22 | 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of public servants who made disclosures | 279 | 250 | 152 | 194 | 123 |

| Number of disclosures received | 278 | 266 | 246 | 178 | 101 |

| Number of allegations received in disclosures under the Act | 727 | 425 | 356 | 378 | 169 |

| Number of allegations carried over from previous fiscal years | 359 | 330 | 277 | 160 | 192 |

| Total number of allegations handled (allegations received, including those resulting from a disclosure made in another public sector organization and carried over) | 1086 | 755 | 633 | 541 | 366 |

| Number of allegations that were acted on | 116 | 199 | 323 | 190 | 111 |

| Number of allegations that were not acted on | 319 | 289 | 81 | 154 | 76 |

| Number of investigations commenced as a result of disclosures received | 38 | 51 | 50 | 85 | 63 |

| Number of allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing but no corrective measures | 1 | 0 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Number of allegations that led to corrective measures but no finding of wrongdoing | 17 | 8 | 2 | 22 | 7 |

| Number of allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | 20 | 31 | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| Number of allegations that led to no corrective measures and no find of wrongdoing | 78 | 160 | 309 | 164 | 93 |

| Organizations reporting | 2024–25 | 2023–24 | 2022–23 | 2021–22 | 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of organizations | 140 | 138 | 135 | 136 | 137 |

| Number of organizations that reported enquiries | 44 | 40 | 38 | 35 | 30 |

| Number of organizations that reported allegations received in disclosures | 46 | 36 | 29 | 29 | 27 |

| Number of organizations that reported findings of wrongdoing | 5 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Number of organizations that reported corrective measures | 8 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Number of organizations that reported finding systemic problems that gave rise to wrongdoing | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Number of organizations that did not disclose information about findings of wrongdoing within 60 days | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

A.2 Organizations reporting activity under the Act in 2024–25Footnote 10

| Organizations reporting activity under the Act in 2024–25 | General enquiries | Allegations received in disclosures | Investiga-tions commenced | Allegations received in disclosures that led to: | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations received | Carried over from the 2023–24 fiscal year | Acted on | NOT acted on | Referred to another recourse mechanism | Did not meet the definition of wrongdoing and not referred to a recourse process | Other action was taken | Carried over into the 2025–26 fiscal year | Finding of wrongdoing but no corrective measures | Finding of corrective measures without a finding of wrongdoing | Finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | |||

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Business Development Bank of Canada | 0 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 7 | 38 | 45 | 39 | 31 | 10 | 1 | 20 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Canada Energy Regulator | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Post Corporation | 1 | 71 | 7 | 4 | 72 | 0 | 72 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada School of Public Service | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Grain Commission | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Heritage | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Museum of History and Canadian War Museum | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Museum of Nature | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Space Agency | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 22 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Courts Administration Service | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 1 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Justice Canada | 8 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada (including Service Canada, Labour Program, and Canada Employment Insurance Commission) | 64 | 22 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Export Development Canada | 2 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Farm Credit Canada | 51 | 29 | 2 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 5 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 28 | 39 | 31 | 9 | 38 | 17 | 12 | 9 | 23 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Health Canada | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 30 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Impact Assessment Agency of Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 15 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 27 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International Development Research Centre | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marine Atlantic Inc. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Capital Commission | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Defence | 13 | 20 | 13 | 0 | 16 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Research Council Canada | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Office of the Chief Electoral Officer | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parks Canada | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parole Board of Canada | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Safety Canada | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Service Commission of Canada | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 2 | 12 | 20 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mint | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 12 | 259 | 184 | 0 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 419 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shared Services Canada | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Staff of the Non-Public Funds, Canadian Armed Forces | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistics Canada | 10 | 19 | 0 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| The Jacques-Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc. | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Transport Canada | 0 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veterans Affairs Canada | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIA Rail Canada Inc. | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grand Total | 398 | 727 | 359 | 116 | 319 | 91 | 172 | 56 | 651 | 38 | 1 | 17 | 20 |

A.3 Organizations that reported a finding of wrongdoing under the Act, 2024–25

| Organization | Link to published report |

|---|---|

| Business Development Bank of Canada | Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: BDC |

| Global Affairs Canada | Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference number - PSDPA2023-0001 |

| Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference number - PSDPA2020-0007 | |

| Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference number - PSDPA2022-0041 | |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference number - DS2024-001 |

| Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference number - DS2024-002 | |

| Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference number - DS2024-003 | |

| Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges | Acts of Founded Wrongdoing : JCCB |

| Transport Canada | Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: TC |

A.4 Organizations that reported no disclosure activities in 2024–25

- Accessibility Standards Canada

- Administrative Tribunals Support Services of Canada

- Atlantic Pilotage Authority Canada

- Atomic Energy of Canada Limited

- Canada Council for the Arts

- Canada Development Investment Corporation

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions

- Canada Infrastructure Bank

- Canada Lands Company Limited

- Canada Science and Technology Museum

- Canada Water Agency

- Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) / Radio-Canada

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Copyright Board Canada

- Correctional Investigator Canada, The

- Defence Construction Canada

- Destination Canada

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Farm Products Council of Canada

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Northern Ontario

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation

- Great Lakes Pilotage Authority

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada

- International Joint Commission (Canadian Section)

- Invest in Canada

- Laurentian Pilotage Authority

- Law Commission of Canada

- Library and Archives Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- National Arts Centre

- National Film Board

- National Gallery of Canada

- National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Canada Elections

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

- Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Intelligence Commissioner

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Secretary of the Governor General

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada

- Pacific Economic Development Canada

- Pacific Pilotage Authority Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- Prairies Economic Development Canada

- Privy Council Office

- Public Sector Pension Investment Board

- RCMP External Review Committee

- Secretariat of the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- Standards Council of Canada

- Supreme Court of Canada

- Telefilm Canada

- The Federal Bridge Corporation Limited

- The National Battlefields Commission

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada

- Veterans Review and Appeal Board

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

A.5 Organizations that do not have a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing that declared an exception under subsection 10.4 of the Act

- Administrative Tribunals Support Services of Canada

- Canada Lands Company Limited

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation

- Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation

- Law Commission of Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- National Film Board

- Office of the Commissioner of Canada Elections

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Intelligence Commissioner

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- RCMP External Review Committee

- Telefilm Canada

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Appendix B: Public Service Employee Survey

The data presented in this appendix is sourced from the 2024 Public Service Employee Survey Results for the Public Service.

Figure B1 - Text version

| Survey years | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2014 | 62% |

| 2017 | 64% |

| 2018 | 63% |

| 2019 | 68% |

| 2020 | 73% |

| 2022 | 71% |

| 2024 | 64% |

Figure B2 - Text version

| Survey years | Positive answers |

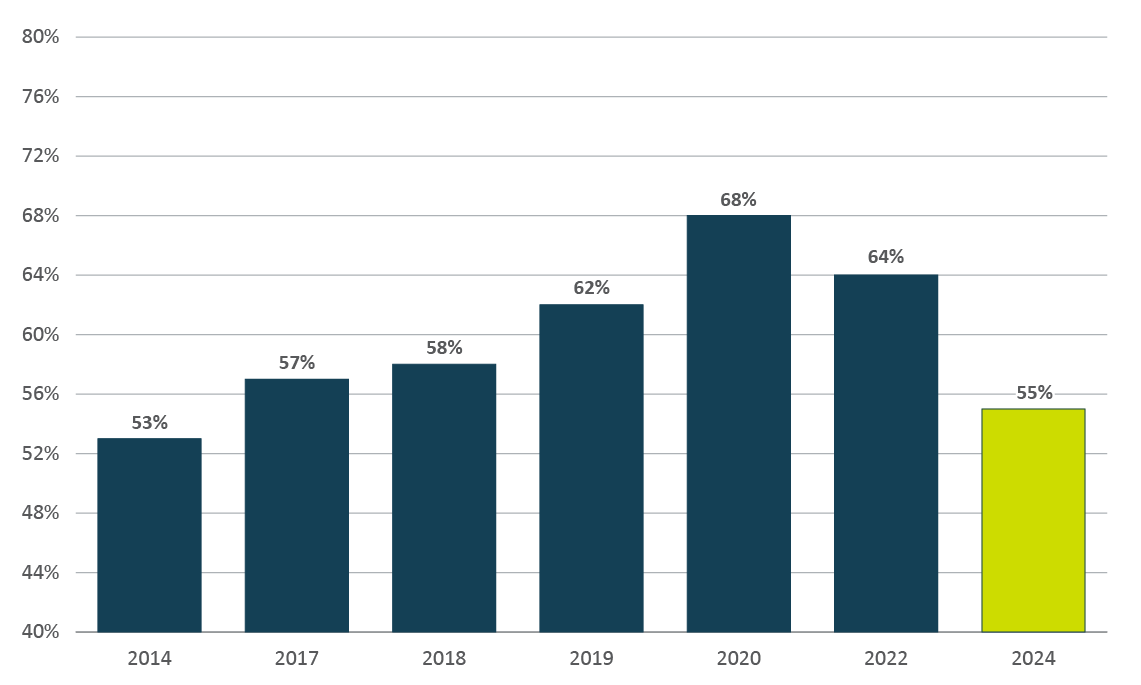

|---|---|

| 2014 | 53% |

| 2017 | 57% |

| 2018 | 58% |

| 2019 | 62% |

| 2020 | 68% |

| 2022 | 64% |

| 2024 | 55% |

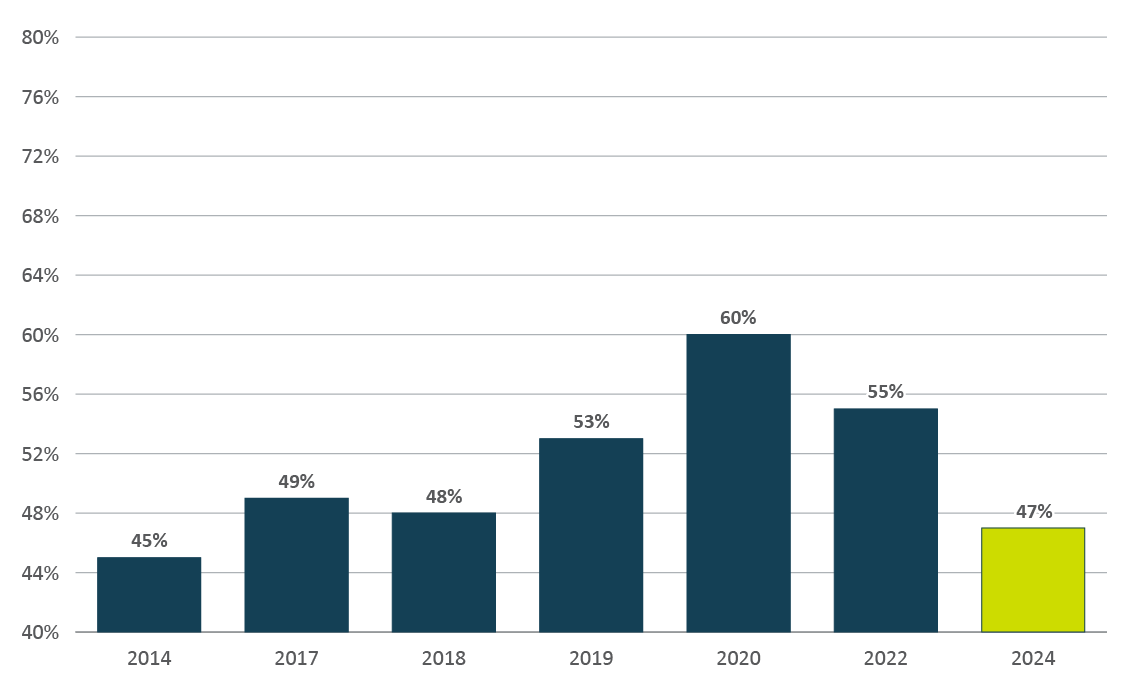

Figure B3 - Text version

| Survey years | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2014 | 45% |

| 2017 | 49% |

| 2018 | 48% |

| 2019 | 53% |

| 2020 | 60% |

| 2022 | 55% |

| 2024 | 47% |

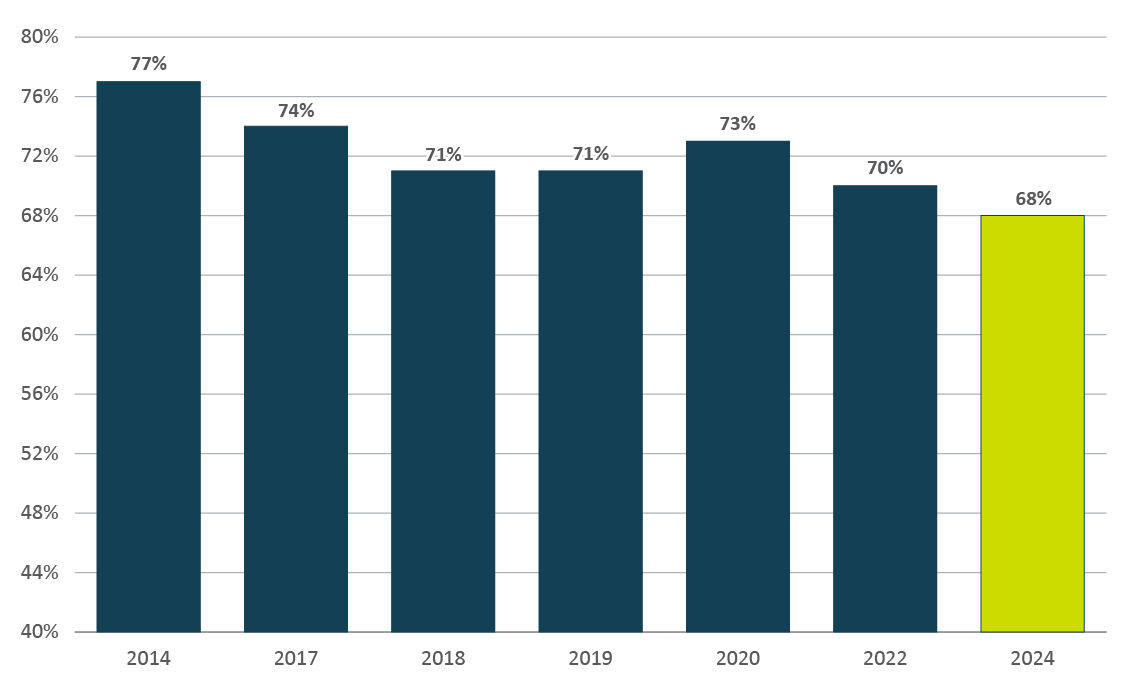

Figure B4 - Text version

| Survey years | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2014 | 77% |

| 2017 | 74% |

| 2018 | 71% |

| 2019 | 71% |

| 2020 | 73% |

| 2022 | 70% |

| 2024 | 68% |

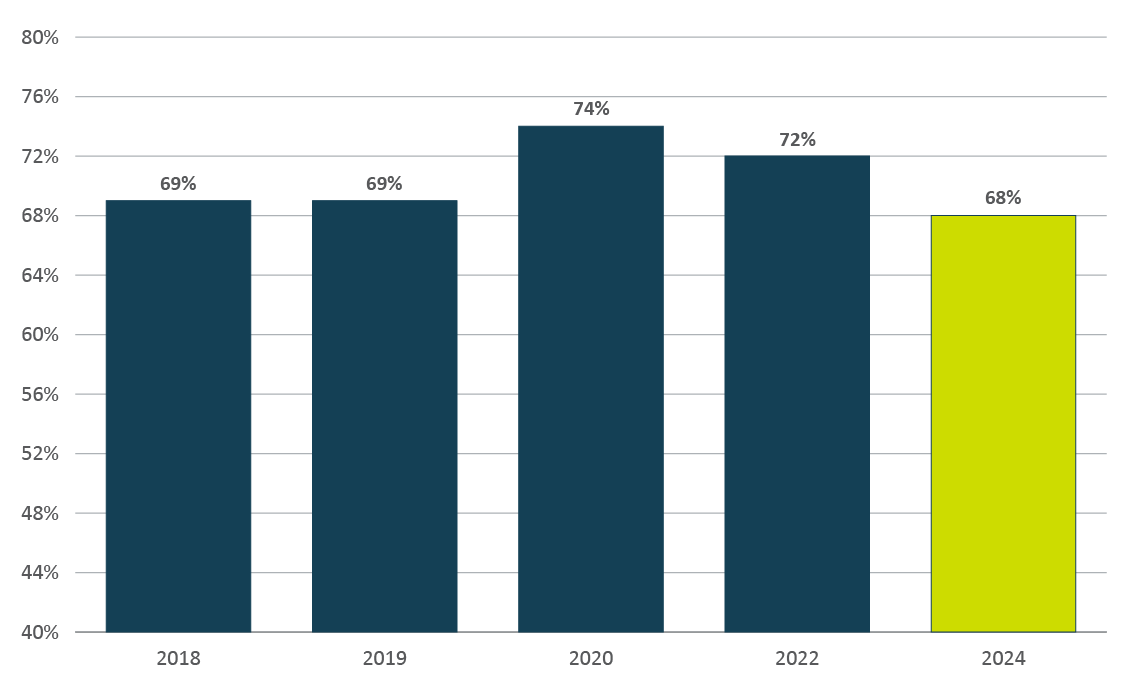

Figure B5 - Text version

| Survey years | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 69% |

| 2019 | 69% |

| 2020 | 74% |

| 2022 | 72% |

| 2024 | 68% |

Figure B6 - Text version

| Survey years | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2014 | 45% |

| 2017 | 48% |

| 2018 | 48% |

| 2019 | 50% |

| 2020 | 55% |

| 2022 | 56% |

| 2024 | 51% |

Figure B7 - Text version

- Q33. Senior managers in my department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour.

- Q34. I have confidence in the senior management of my department or agency.

- Q35. Senior management in my department or agency makes effective and timely decisions.

- Q40. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation.

- Q41. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace.

- Q42. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal.

| Question | Indigenous people | Persons with disabilities | Members of racial group | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q33 | 61% | 56% | 70% | 68% | 64% |

| Q34 | 53% | 47% | 61% | 59% | 55% |

| Q35 | 46% | 39% | 55% | 50% | 47% |

| Q40 | 64% | 62% | 69% | 70% | 68% |

| Q41 | 63% | 61% | 71% | 70% | 68% |

| Q42 | 46% | 41% | 53% | 50% | 51% |

| Province, territory or National Capital Region | Q33. Senior managers in my department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour | Q34. I have confidence in the senior management of my department or agency | Q35. Senior management in my department or agency makes effective and timely decisions | Q40. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation | Q41. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace | Q42. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outside of Canada | 58% | 49% | 36% | 75% | 66% | 40% |

| Northwest Territories | 68% | 58% | 52% | 73% | 72% | 57% |

| Saskatchewan | 63% | 56% | 49% | 68% | 66% | 51% |

| British Columbia | 60% | 51% | 43% | 66% | 63% | 49% |

| Alberta | 60% | 52% | 46% | 65% | 64% | 49% |

| Yukon | 71% | 62% | 54% | 71% | 66% | 53% |

| Nova Scotia | 64% | 56% | 48% | 69% | 68% | 54% |

| Ontario (excluding National Capital Region) | 63% | 55% | 48% | 67% | 66% | 51% |

| Nunavut | 70% | 66% | 61% | 59% | 67% | 54% |

| Quebec (excluding National Capital Region) | 62% | 48% | 38% | 63% | 66% | 50% |

| Manitoba | 64% | 56% | 49% | 70% | 69% | 54% |

| National Capital Region | 66% | 56% | 47% | 68% | 69% | 50% |

| New Brunswick | 72% | 64% | 56% | 73% | 74% | 58% |

| Prince Edward Island | 72% | 65% | 57% | 73% | 74% | 58% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 73% | 66% | 56% | 76% | 77% | 57% |

| Organizational mandate | Q33. Senior managers in my department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour | Q34. I have confidence in the senior management of my department or agency | Q35. Senior management in my department or agency makes effective and timely decisions | Q40. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation | Q41. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace | Q42. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other mandate | 60% | 51% | 41% | 69% | 63% | 39% |

| Security and military | 56% | 48% | 41% | 62% | 58% | 48% |

| Business and economic development | 66% | 58% | 49% | 67% | 68% | 48% |

| Science-based | 65% | 55% | 45% | 67% | 68% | 50% |

| Justice, courts and tribunals | 69% | 59% | 51% | 71% | 70% | 48% |

| Central agency and government operations | 69% | 59% | 51% | 72% | 72% | 54% |

| Social and culture | 69% | 59% | 50% | 70% | 72% | 53% |

| Agents of Parliament | 72% | 61% | 51% | 74% | 74% | 56% |

| Enforcement and regulatory | 67% | 56% | 49% | 69% | 71% | 54% |

| Public service | 64% | 55% | 47% | 68% | 68% | 51% |

| Employment community | Q33. Senior managers in my department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour | Q34. I have confidence in the senior management of my department or agency | Q35. Senior management in my department or agency makes effective and timely decisions | Q40. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation | Q41. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace | Q42. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security | 40% | 34% | 28% | 51% | 44% | 37% |

| Health care practitioners | 53% | 44% | 36% | 62% | 57% | 43% |

| Policy | 63% | 54% | 45% | 66% | 63% | 42% |

| Legal services | 70% | 60% | 52% | 70% | 70% | 44% |

| Federal regulators | 62% | 51% | 42% | 70% | 67% | 49% |

| None of the above | 59% | 51% | 43% | 64% | 62% | 48% |

| Project management | 66% | 55% | 45% | 67% | 67% | 47% |

| Communications or public affairs | 68% | 58% | 48% | 69% | 70% | 50% |

| Compliance, inspection and enforcement | 57% | 47% | 40% | 65% | 63% | 47% |

| Science and technology | 65% | 51% | 41% | 66% | 69% | 54% |

| Real property | 62% | 53% | 43% | 67% | 67% | 50% |

| Evaluation | 62% | 52% | 42% | 67% | 66% | 48% |

| Other services to the public | 65% | 57% | 49% | 68% | 68% | 52% |

| Administration and operations | 69% | 61% | 53% | 71% | 71% | 52% |

| Financial management | 70% | 62% | 54% | 69% | 71% | 52% |

| Procurement | 70% | 60% | 52% | 70% | 72% | 53% |

| Data sciences | 68% | 55% | 47% | 65% | 69% | 54% |

| Information management | 69% | 59% | 51% | 71% | 71% | 57% |

| Materiel management | 67% | 60% | 51% | 68% | 70% | 58% |

| Human resources | 65% | 56% | 46% | 74% | 72% | 53% |

| Library services | 56% | 44% | 35% | 66% | 64% | 51% |

| Internal audit | 70% | 57% | 47% | 73% | 75% | 55% |

| Information technology | 68% | 57% | 50% | 70% | 72% | 59% |

| Access to information and privacy | 71% | 65% | 59% | 72% | 75% | 58% |

| Client contact centre | 72% | 62% | 53% | 71% | 75% | 58% |

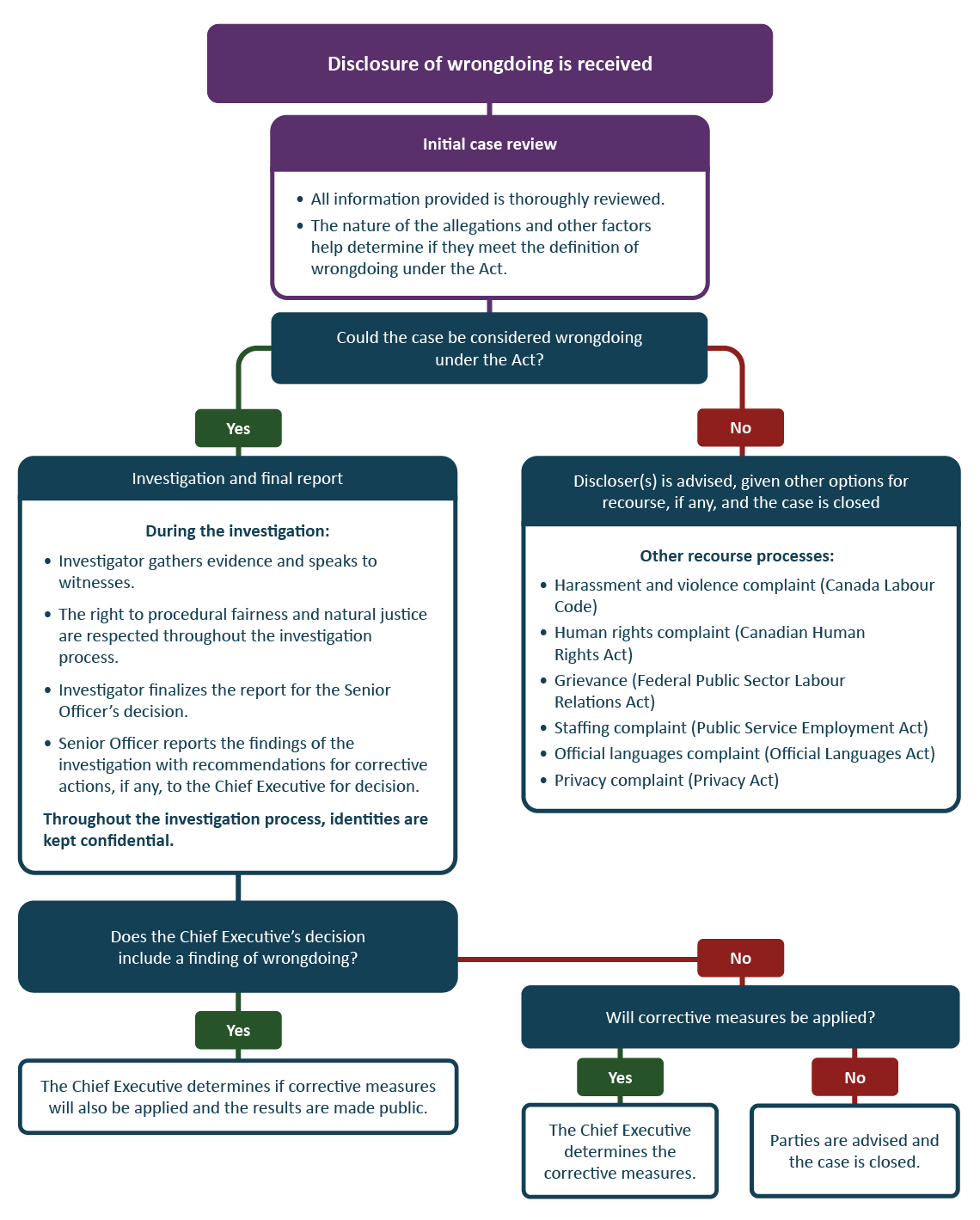

Appendix C: Disclosure Process Under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

Figure C1 - Text version

Disclosure of wrongdoing is received

Initial case review

- All information provided is thoroughly reviewed

- The nature of the allegations and other factors help determine if they meet the definition of wrongdoing under the Act

Could the case be considered wrongdoing under the Act?

Yes

Investigation and final report

During the investigation

- Investigator gathers evidence and speaks to witnesses

- The right to procedural fairness and natural justice are respected throughout the investigation process

- Investigator finalizes the report for the Senior Officer’s decision

- Senior Officer reports the findings of the investigation with recommendations for corrective actions, if any, to the Chief Executive for decision

Throughout the investigation process, identities are kept confidential.

Does the Chief Executive’s decision include a finding of wrongdoing?

Yes

- The Chief Executive determines if corrective measures will also be applied and the results are made public

No

- Will corrective measures be applied?

Yes

- The Chief Executive determines the corrective measures

No

- Parties are advised and the case is closed

Could the case be considered wrongdoing under the Act?

No

Discloser(s) is advised, given other options for recourse, if any, and the case is closed

Other recourse processes

- Harassment and violence complaint (Canada Labour Code)

- Human rights complaint (Canadian Human Rights Act)

- Grievance (Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act)

- Staffing complaint (Public Service Employment Act)

- Official languages complaint (Official Languages Act)

- Privacy complaint (Privacy Act)

Appendix D: Key Terms

For the purposes of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) and this report, “public servant” means every person employed in the public sector. The term includes the deputy heads and chief executives of public sector organizations, but it does not include other Governor in Council appointees (for example, judges or board members of Crown corporations) or parliamentarians and their staff.

The Act defines wrongdoing as any of the following actions in, or relating to, the public sector:

- a violation of a federal or provincial law or regulation

- misuse of public funds or assets

- a gross mismanagement in the public sector

- a serious breach of a code of conduct established under the Act

- an act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons or to the environment

- knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing

A protected disclosure is a disclosure that is made in good faith by a public servant under any of the following conditions:

- in accordance with the Act, to the public servant’s immediate supervisor or senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing, or to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- in the course of a parliamentary proceeding

- in the course of a procedure established under any other act of Parliament

- when lawfully required to do so

The Act defines reprisal as any of the following measures taken against a public servant who has made a protected disclosure or who has, in good faith, cooperated in an investigation into a disclosure:

- a disciplinary measure

- demotion of the public servant

- termination of the employment of the public servant

- a measure that adversely affects the employment or working conditions of the public servant

- a threat to do any of the above or to direct a person to do them

Every organization subject to the Act is required to establish internal procedures to manage disclosures made in the organization. Organizations that are too small to establish their own internal procedures can declare an exception under subsection 10(4) of the Act. In addition, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Communications Security Establishment Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces, which are excluded from the Act by virtue of section 52 of the Act, are required to establish their own procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoing, including for protecting persons who disclose wrongdoing.

In organizations that have declared an exception, disclosures under the Act may be made to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada.

The senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing is the person designated in each organization to receive and address disclosures made under the Act. Senior officers have the following key leadership roles for implementing the Act in their organizations:

- providing information, advice and guidance to public servants regarding the organization’s internal disclosure procedures, including the making of disclosures, the conduct of investigations into disclosures, and the handling of disclosures made to supervisors

- receiving and recording disclosures and reviewing them to establish whether there are sufficient grounds for further action under the Act

- managing investigations into disclosures, including determining whether to deal with a disclosure under the Act, initiate an investigation or cease an investigation

- coordinating the handling of a disclosure with the senior officer of another federal public sector organization, if a disclosure or an investigation into a disclosure involves that other organization

- notifying, in writing, the person or persons who made a disclosure of the outcome of any review or investigation into the disclosure and of the status of actions taken on the disclosure, as appropriate

- reporting the findings of investigations, as well as any systemic problems that may give rise to wrongdoing, directly to their chief executive with any recommendations for corrective action

Other relevant terms

- allegation of wrongdoing

- The communication of a potential instance of wrongdoing as defined in section 8 of the Act. The allegation must be made in good faith, and the person making it must have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true.

- disclosure

- The provision of information by a public servant to their immediate supervisor or to a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing that is made in good faith and includes one or more allegations of possible wrongdoing in the public sector, in accordance with section 12 of the Act.

- disclosure that was acted upon (admissible disclosure)

- An allegation received in a disclosure where action, including preliminary analysis, fact-finding and investigation, was taken to determine whether wrongdoing occurred and whether that determination was made during the reporting period.

- disclosure that was not acted upon (inadmissible disclosure)

- An allegation received in a disclosure for which the designated senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing determined that the definition of wrongdoing under the Act was not met, or should be referred to another process, or required no further action.

- general enquiry

- An enquiry about procedures established under the Act or about possible wrongdoings, not including actual disclosures.

- investigation

- A formal investigation triggered by a disclosure. An investigation may look into one or more allegations that result from a disclosure of possible wrongdoing.

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2025,

ISSN: 2292-048X