Consultation on Strengthening Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime

Process

The Government of Canada has launched this public consultation to examine ways to improve Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime. We invite you to submit comments or feedback in response to specific questions and issues identified in the consultation paper, as well as any further comments or feedback relevant to the scope of this consultation.

Submissions to this consultation will close on August 1, 2023.

Contact Us

Email us your comments and feedback at fcs-scf@fin.gc.ca with "Consultation Submission" as the subject line.

Comments and feedback may also be sent by mail to:

Director General

Financial Crimes and Security Division

Financial Sector Policy Branch

Department of Finance Canada

90 Elgin Street

Ottawa ON K1A 0G5

Confidentiality

In order to respect privacy and confidentiality, please advise when providing your comments whether you:

- consent to the public disclosure of your comments in whole or in part;

- request that your identity and any personal identifiers be removed prior to publication; or

- wish that any portions of your comments not be publicly disclosed (if so, clearly identify the portions in question).

Information received through this comment process is subject to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. Should you indicate that your comments, or any portions thereof, be considered confidential, all reasonable efforts will be made to protect this information.

Table of Contents

Part I - Overview and Government Efforts to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

Chapter 1 – Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime

Combatting Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

Overview of the Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime

Protecting Privacy and Charter Rights

Canada's Contribution to International Efforts

Canada's Mutual Evaluation Report by the FATF

Chapter 2 – Key Developments Since the 2018 Parliamentary Review

The 2018 Parliamentary Review: Report and Recommendations

Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia

Enhancing the Legislative and Regulatory Framework

Combatting Trade Fraud and Trade-Based Money Laundering

Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada

Regime Strategy and Performance Measurement Framework

Chapter 3 – Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Collaboration

3.1 – Beneficial Ownership Transparency

Part II - Operational Effectiveness

Chapter 4 – Criminal Justice Measures to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

4.1 – Investigation and Prosecution of the Offence of Laundering Proceeds of Crime

4.2 – Offences for other Economically-Motivated Crime

4.3 – Sentencing for Laundering Proceeds of Crime

4.4 – Access to Subscriber Information under the Criminal Code

4.6 – Digital Assets and Related Challenges

4.7 – Pre-Trial Seizure and Restraint of Property Associated with Crime

4.9 – Intelligence and Evidence

4.11 – Keep Open Accounts Under Investigation

Chapter 5 – Canada Financial Crimes Agency

5.1 – The Mandate and Structure of the Canada Financial Crimes Agency

5.2 – Core Elements of Effective Financial Crime Enforcement

Chapter 6 – Information Sharing

6.1 – Private-to-Private Information Sharing

6.2 – Public-to-Private Information Sharing

Sharing Information Between FINTRAC and Reporting Entities

Database of Politically Exposed Persons and Heads of International Organizations

Modernizing Data Collection Authorities

Naming Foreign Entities in Strategic Intelligence

6.3 – Public-to-Public Information Sharing

Targeted Information Sharing Between Operational Regime Partners and Law Enforcement

Enhancing Financial Intelligence Disclosures

Sharing Information Between FINTRAC and Canada's Environmental Enforcement Organizations

Sharing Information Between FINTRAC and Other Regulators

Part III - PCMLTFA Legislative and Regulatory Framework

Chapter 7 – Scope and Obligations of AML/ATF Framework

7.1 – Review Existing Reporting Entities

Dealers in Precious Metals and Stones

Virtual Currency, Digital Assets, and Technology-Enabled Finance

7.2 – Expanding AML/ATF Coverage in the Real Estate Sector

Real Estate Sales by Owner and Auction

Unrepresented Parties in a Real Estate Transaction

Building Supply and Renovation Companies

Title Insurers and Mortgage Insurers

7.3 – Expanding Regime Scope to Other New Sectors

White Label Automated Teller Machines

7.4 – Streamlining Regulatory Requirements

End Period for Business Relationships

Opportunities to Streamline Other AML/ATF Obligations

Chapter 8 – Regulatory Compliance Framework

8.1 – Modernizing Compliance Tools

Publicizing Violations and Penalties

Issuing Administrative Penalties Against Individuals

8.2 – Effective Oversight and Reporting Framework

Money Services Businesses (MSB) and Foreign MSB Registration Framework

Universal Registration for All Reporting Entities

Exemptive Relief for Testing New Technologies

8.3 – Additional Preventive and Risk Mitigation Measures

Geographic and Sectoral Targeting Orders

Source of Wealth/Funds Determinations

Restricting Third-party Cash Deposits

Part IV - National and Economic Security

Chapter 9 – National and Economic Security

9.1 – Threats to the Security of Canada

9.4 – Ministerial and Emergency Powers

Annex 2 – List of Consultation Questions

Executive Summary

Money laundering and terrorist financing support, reward, and perpetuate criminal activities that threaten the safety and security of Canadians and the integrity of our economy. Canada faces continually evolving risks and threats from money laundering and terrorist financing as criminals adopt new strategies to exploit economic sectors and emerging financial technologies. A strong legislative and regulatory framework and consistent and effective enforcement are required to detect, disrupt, and deter these financial crimes.

In an increasingly interconnected world, Canada is also exposed to transnational criminal elements and corrupt actors seeking to use Canada's economy and financial system as a vehicle for money laundering and terrorist financing. Maintaining international best practices and ensuring a robust sanctions framework assist Canada in fulfilling our international obligations and commitments to combat transnational crime and international security concerns and protect Canadians.

The Government of Canada is committed to a strong Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing (AML/ATF) Regime to combat financial crime, while respecting citizens' rights, including privacy rights. Canada's AML/ATF Regime is established under several statutes, including the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA), its associated Regulations, and the Criminal Code.

This year, a Committee of Parliament will conduct a Parliamentary Review of the PCMLTFA, as required every five years under section 72(1) of the Act. This requirement provides the opportunity to keep the AML/ATF Regime current in response to market developments, as well as new and evolving risks. The Parliamentary Committee will release a report of its review that will inform future policy measures to strengthen Canada's AML/ATF Regime. To support the 2023 Parliamentary Review of the PCMLTFA, the government has released this consultation paper to review Canada's AML/ATF statutory framework and seek feedback to support the development of policy measures to strengthen the AML/ATF Regime.

Since the last Parliamentary Review in 2018, the government has made important enhancements to the AML/ATF Regime, including strengthening and modernizing laws and regulations, and investing in operational partners. The Department of Finance has published Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime Strategy 2023-2026 outlining its national strategic vision and federal priorities for combatting money laundering and terrorist financing, as well as a Report on Performance Measurement Framework detailing the results achieved by Canada's Regime. This paper aligns with the Regime Strategy and is informed by the findings of the Report on Performance Measurement Framework.

As the money laundering and terrorist financing environment has continued to evolve, the Department of Finance has released an Updated Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada to help policy makers and the public understand the main inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks faced by key sectors and products in Canada. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic changed the way people interact with the financial sector and accelerated the trend towards financial sector digitization, which can pose new money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

The government has also responded to new money laundering and terrorist financing risks posed by virtual asset service providers, foreign money services businesses (MSBs), crowdfunding platforms, payment service providers, mortgage lending entities, and armoured car companies. In the two decades since the PCMLTFA was enacted, the global threat landscape has changed in ways that may compromise Canada's national and economic security. Additionally, the government continues to adapt to international security concerns posed by Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine, including by implementing sanctions against Russian individuals and entities. These raise questions over whether and how the AML/ATF Regime should respond and adapt to these threats.

Despite continued improvements to the legislative and regulatory AML/ATF framework, achieving operational effectiveness remains a persistent challenge. This can cause negative perceptions of Canada as a jurisdiction that is not hostile to money laundering or other financial and profit-motivated crime despite the significant efforts that have been made to crack down on these crimes. Over the years, domestic and international expert reports have highlighted challenges in the ability of Canada's AML/ATF Regime to use financial intelligence, ensure transparency of legal persons and arrangements, successfully investigate and prosecute money laundering, and deprive criminals of the proceeds of crime.

For instance, in its 2016 Mutual Evaluation of Canada, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental AML/ATF standard-setting body, found that Canada generally has strong AML/ATF legislation and regulations. However, it pointed to a need for increased efforts to detect, investigate, and prosecute cases across a broader range of the high-risk areas consistent with Canada's risk profile, including various forms of money laundering, pursuing asset recovery more consistently, and use of financial intelligence. The FATF also noted certain gaps in meeting technical standards, many of which were addressed in Canada's 2021 follow-up report. Canada's next Mutual Evaluation by the FATF is scheduled to occur in 2025 for publication in 2026.

Domestically, the provincial government of British Columbia launched the Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia (also known as the Cullen Commission). The Cullen Commission's final report, issued in June 2022, was critical of the federal AML/ATF Regime and raised questions about its effectiveness. The final report contained findings and recommendations specific to British Columbia, some of which are relevant to the federal AML/ATF Regime. The Government of Canada welcomed the Commission's final report and has committed to responding to all recommendations within its jurisdiction.

Objectives and Structure of This Paper

The overall objectives of this paper are to support the 2023 Parliamentary Review of the PCMLTFA and consult on potential policy measures, some of which may be considered for future legislative and regulatory amendments, including to the PCMLTFA and the Criminal Code. Feedback provided to this consultation will be valuable to policy makers within the AML/ATF Regime, such as the Departments of Finance and Justice, and the Parliamentary Committee conducting the review. Using feedback from this paper and the findings of the upcoming Parliamentary Review, the government will take further actions to:

- Improve the operational results of the AML/ATF Regime regarding the detection and disruption of money laundering and terrorist financing activities;

- Strengthen the overall Regime, in alignment with the AML/ATF Regime Strategy and Performance Measurement Framework Report;

- Address risks and vulnerabilities, including those of higher risk identified in the updated risk assessment and those related to national and economic security;

- Position Canada for its next FATF evaluation and uphold international commitments; and

- Respond to findings from the Cullen Commission.

This paper is organized into four main parts. Part I (Chapters 1-3) provides an overview of Canada's AML/ATF Regime and government efforts to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. Part I provides background information and context on Canada's AML/ATF Regime and contributions to international efforts. It also outlines key developments since the 2018 Parliamentary Review, such as legislative and regulatory changes, investments in operations, and efforts to combat new risks stemming from trade-based money laundering. Part 1 also explores priorities for greater federal, provincial, and territorial collaboration and engagement, including advancing a pan-Canadian beneficial ownership registry, exploring risks in the legal profession, and depriving criminals of their property, including reviewing civil forfeiture powers and the potential need for new tools, such as unexplained wealth orders.

Part II of this paper (Chapters 4-6) explores ways to enhance the operational effectiveness of the AML/ATF Regime to investigate and prosecute money laundering and terrorist financing and deprive criminals of the proceeds of crime. Chapter 4 explores areas for possible criminal law reforms under the Criminal Code for which the Department of Justice seeks input, including the seizure and forfeiture of proceeds of crime and digital assets, and on the offence and sentencing of money laundering. Chapter 5 considers the creation of a new Canada Financial Crimes Agency that would become the lead enforcement agency against financial crimes. Chapter 6 explores enhancing information sharing to better facilitate the detection and disruption of money laundering and terrorist financing, while protecting privacy rights. Chapter 6 also considers a framework for private sector organizations to share information among themselves for AML/ATF purposes, as well as enhancing information sharing between the private sector and federal AML/ATF entities, and among government departments and agencies.

Part III of this paper (Chapters 7 and 8) considers the legislative and regulatory framework of the PCMLTFA. Chapter 7 explores the scope and obligations of the PCMLTFA to help ensure that current obligations effectively target risks, and whether it should expand to cover new sectors, such as luxury goods, white label automated teller machines, horse racing betting, title and mortgage insurers, real estate sales by owner or auction, crypto and digital assets technology, as well as financial crown corporations. Chapter 7 also explores whether regulatory requirements can be streamlined in keeping with a risk-based approach. Chapter 8 reviews the regulatory compliance framework to ensure that the Financial Reports and Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), Canada's AML/ATF regulator and financial intelligence unit, can effectively supervise persons and entities subject to the PCMLTFA. This includes exploring new compliance and oversight tools for FINTRAC, such as allowing FINTRAC to record compliance examinations, provide exemptive relief for testing new technologies, and requiring all regulated persons and entities under the PCMLTFA to register with FINTRAC. It also considers additional measures to target and mitigate risks on a sectoral and geographic basis and strengthen existing requirements around verifying the source of funds used in transactions to ensure they are legitimate.

Part IV of this paper (Chapter 8) discusses national and economic security. The global threat landscape has changed considerably since the PCMLTFA was first introduced and may require an update to consider broader threats to the security of Canada. Holding Russia accountable for its illegal invasion of Ukraine has made economic sanctions an important foreign policy tool. This makes sanctions evasion an even more pressing and concerning economic threat, as it undermines the efforts of Canada and international allies to isolate Russia economically. Budget 2023 announced the government's intent to review the mandate of FINTRAC to determine whether it should be expanded to counter sanctions evasion and the financing of threats to national and economic security. Chapter 8 considers these issues in greater detail.

The paper also contains an annex of further technical proposals to modernize and enhance the AML/ATF legislative and regulatory framework.

Other policy measures and issues for consideration that are not explored in this paper may be raised or proposed in the future, potentially stemming from findings from the Parliamentary Review.

This paper was developed by the Department of Finance in collaboration with the federal government departments and agencies that form Canada's AML/ATF Regime (see next section for a list of organizations), and with input from private sector members of the Advisory Committee on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing. As part of this consultation process, submissions will be shared with the appropriate federal department or agency.

Through this consultation, the government has taken a broad and comprehensive look at Canada's AML/ATF Regime and considered many potential measures for its improvement. As noted above, this includes improving operational effectiveness and enforcement outcomes, facilitating greater information sharing, modernizing legislative and regulatory obligations while balancing burden on the private sector, and responding to national and economic security risks. The government invites feedback and views on ways to improve Canada's AML/ATF regime, including on the main policy themes, as well as on the specific questions and issues raised in this consultation. Submissions can choose to cover any and all of the topics raised in this consultation.

Part I - Overview and Government Efforts to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

Chapter 1 – Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime

Combatting Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

Money laundering is the process used to convert or conceal the origin of criminal proceeds to make them appear as if they originated from legitimate sources. Money laundering benefits domestic and international criminals and organized crime groups. Terrorist financing is the collection and provision of funds from legitimate or illegitimate sources for terrorist activity. It supports and sustains the activities of domestic and international terrorists that can result in terrorist attacks in Canada or abroad, causing loss of life and destruction.

Most Canadians have no direct exposure to money laundering or terrorist financing activities; however, these crimes affect our society by supporting, rewarding, and perpetuating broader criminal and terrorist activities. Money laundering is not a victimless crime. The proceeds of crime being laundered in Canada are often generated at the direct expense of and harm to innocent Canadians, through crimes such as fraud, theft, drug trafficking, human trafficking for sexual exploitation, and online child sexual exploitation. As long as criminals can continue laundering the proceeds from their crimes, they have a strong incentive to continue the criminal activities and enterprises that harm Canadians and our society.

Measures to counter money laundering and terrorist financing have long been recognized as powerful means to combat crime and protect the safety and security of Canadians, as well as the integrity of our economy and financial system.

Internationally, Canada is recognized as a multicultural and multiethnic country with a stable and open economy, accessible financial system, well-developed international trading system, and strong democratic institutions. Although these features are among Canada's strengths, some can be subject to criminal exploitation. Transnational criminals, organized crime groups, and terrorist financiers may seek to use Canada's stable economy and financial system as a vector for money laundering and terrorist financing, exploiting Canadians, including diaspora communities, in the process. Measures taken by the government to mitigate risks related to money laundering and terrorist financing should be considered within this context. Many Canadians have ties to communities around the world which they maintain, and while there are international risks, these relationships are not, in and of themselves, a vector for money laundering, terrorist financing or other criminality.

Overview of the Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime

Several federal statutes and regulations establish Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing (AML/ATF) Regime and set out the roles and responsibilities of the 13 federal partners that contribute to and share responsibility for the Regime's outcomes. Principal among these laws are the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA) and its associated Regulations, and the Criminal Code.

The following 13 federal partners contribute to Canada's AML/ATF regime:

- Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)

- Canada Revenue Agency (CRA)

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS)

- Department of Finance Canada

- Department of Justice Canada

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC)

- Global Affairs Canada

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI)

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

Provincial and municipal law enforcement bodies, provincial Crown Attorneys' offices or prosecution services, and provincial regulators (including those with a role in the oversight of the financial sector) also play important roles in combating money laundering and terrorist financing and may work in partnership with federal Regime partners.

The PCMLTFA stipulates the persons and entities subject to its legislative framework, such as financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions. These persons and businesses, known as reporting entities, must fulfill reporting, record-keeping, and client due diligence obligations under the PCMLTFA. There are over 24,000 reporting entities that play a critical, frontline role in efforts to prevent and detect money laundering and terrorist financing.

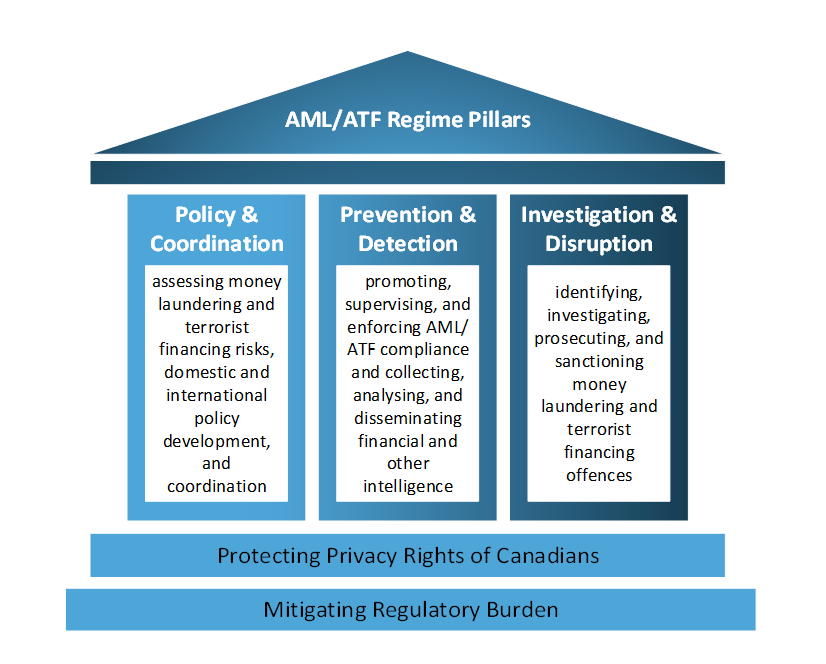

Canada's AML/ATF Regime operates on the basis of three interdependent pillars: (i) policy and coordination; (ii) prevention and detection; and (iii) investigation and disruption.

- policy and coordination – assessing money laundering and terrorist financing risks, domestic and international policy development, and coordination;

- prevention and detection – promoting, supervising, and enforcing AML/ATF compliance and collecting, analyzing, and disseminating financial and other intelligence; and

- investigation and disruption – identifying, investigating, prosecuting, and sanctioning money laundering and terrorist financing offences.

AML/ATF Regime Pilars

Protecting Privacy and Charter Rights

The potential policy measures in this paper seek to combat money laundering and terrorist financing while respecting the Constitutional division of powers, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms(Charter) and the privacy rights of Canadians.

Section 8 of the Charter enshrines privacy rights as an implicit extension of the individual's right to protection from unreasonable search or seizure by the state. Privacy rights are further established in Canada's two federal privacy laws: the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. Privacy rights and protections are detailed further in Chapter 6 on Information Sharing.

The PCMLTFA requires reporting entities to disclose designated financial information to FINTRAC and allows FINTRAC to disclose certain designated information to law enforcement and intelligence agencies for investigation once certain legislative thresholds are met. FINTRAC is independent and arm's length from law enforcement agencies and does not conduct criminal investigations. The PCMLTFA has safeguards in place to ensure that privacy rights are protected in the course of FINTRAC's activities. First, the PCMLTFA prescribes the specific information that FINTRAC can receive and disclose, in addition to the law enforcement and intelligence agencies to which FINTRAC may disclose. The PCMLTFA also limits the circumstances in which FINTRAC can disclose information to these agencies. To disclose information, FINTRAC must have reasonable grounds to suspect that the information would be relevant to the investigation or prosecution of a money laundering or a terrorist financing offence, or relevant to the investigation of threats to the security of Canada.

Further, the PCMLTFA requires the Privacy Commissioner of Canada to conduct reviews of the measures taken by FINTRAC to protect information it receives or collects under the PCMLTFA. This is to ensure that FINTRAC protects the information it receives as part of its operations. The Privacy Commissioner reports the findings of each review to Parliament.

Canada's Contribution to International Efforts

In an interconnected global financial system, the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing requires international efforts and cooperation. Canada's AML/ATF Regime protects the integrity and stability not only of our own financial system, but also contributes to protecting the global financial system. Maintaining a strong AML/ATF Regime helps ensure Canada's financial system and economy remain secure and trustworthy in the eyes of our international allies and trading partners and allows Canada to meet its international commitments.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an inter-governmental body that sets standards for combating money laundering and terrorist financing and ensures that all members' AML/ATF regimes are held to the same standards. The FATF monitors the implementation of these standards among its own 39 members and the more than 200 countries and jurisdictions in the global network of FATF-style regional bodies through peer reviews and public reporting. Canada is a founding member of the FATF and continues to be an active contributor to the FATF global network.

Canada will have the opportunity to exercise global leadership and influence in combatting money laundering and terrorist financing. Canada has been chosen to serve for two years, effective July 2023, as Vice President of the FATF. Additionally, from July 2022 to July 2024, Canada serves as the Co-Chair of the Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG), one of the FATF-style regional bodies. During its time as APG Co-Chair, Canada will advance key priorities in the Asia-Pacific region related to beneficial ownership transparency, combatting grand corruption, countering terrorist financing and digital transformation.

Canada also works with international partners through fora such as the United Nations, the G7/G20, and the Counter-ISIL Finance Group. Canada implements all relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions to freeze and seize the assets of persons and entities engaged in terrorism.

Canada's Mutual Evaluation Report by the FATF

In September 2016, the FATF released its peer reviewed Mutual Evaluation Report of Canada's AML/ATF Regime. The report found that Canada has a good understanding of its money laundering and terrorist financing risks and that AML/ATF cooperation and coordination are generally good at the policy and operational levels. In addition, Canada was found to have strong AML/ATF legislation and regulations.

The FATF did highlight areas for improvement. With respect to Canada's framework, the limited availability of accurate beneficial ownership information for use by competent authorities, and the fact that the legal profession is not covered by the PCMLTFA, were identified as weaknesses. Regarding operational results, the FATF found that financial intelligence could be used to a greater extent by investigators, money laundering investigation and prosecution results were not commensurate with Canada's risk profile, and that asset recovery was low.

In October 2021, the FATF released its follow-up report, in which Canada was upgraded on several technical compliance standards. The FATF found that Canada had made progress in addressing technical compliance deficiencies related to politically exposed persons, wire transfers, reliance on third parties, reporting of suspicious transactions, and designated non-financial businesses and professions. However, Canada was also downgraded from compliant to partially compliant on the recommendation regarding non-profit organizations, which was revised after Canada's 2016 evaluation.

Canada's next mutual evaluation by the FATF will be adopted in June 2026 and will consider improvements made up to October 2025. This next review will focus to a greater extent on Canada's ability to demonstrate the effectiveness of its AML/ATF Regime, including Canada's ability to investigate and prosecute financial crime and deprive criminals of offence-related property and the proceeds of crime.

Several of the potential policy measures discussed in this paper are aimed at strengthening Canada's AML/ATF Regime, which would help position Canada for its next FATF assessment.

Chapter 2 – Key Developments Since the 2018 Parliamentary Review

The 2018 Parliamentary Review: Report and Recommendations

The 2018 Parliamentary Review of the PCMLTFA was undertaken by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance. The Committee's report, Confronting Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing: Moving Canada Forward, released in November 2018, contained 32 recommendations aimed at improving Canada's AML/ATF Regime.

The government published a response to the Committee' report. The government substantively agreed with most of the Committee's recommendations, which were aligned with the government's direction on AML/ATF.

Since 2018, the government has taken significant actions to strengthen the AML/ATF Regime and address the Committee's recommendations. Many of the recommendations have been addressed, while some are subject to further policy analysis, such as enabling the private sector to share AML/ATF-related information, covering luxury goods and white-label automated teller machines under the PCMLTFA, and creating a framework for geographic and sectoral targeting orders. These proposals are considered in this consultation paper.

Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia

On May 15, 2019, the province of British Columbia announced the establishment of the Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia, also referred to as the Cullen Commission. Broadly speaking, the Cullen Commission had a mandate to inquire into and report on money laundering in British Columbia, and to make recommendations relevant to its findings.

On June 15, 2022, the Cullen Commission released its final report. The Cullen Commission did not make recommendations directly to the federal government, as the inquiry was circumscribed to provincial affairs only. Nevertheless, the findings of the Cullen Commission are valuable for exploring ways to improve Canada's AML/ATF Regime, and some of the report's recommendations have implications for the federal Regime.

The government welcomed the Cullen Commission's final report and has committed to respond to all recommendations within its jurisdiction. Many of the proposals in this consultation paper respond to findings of the Cullen Commission.

Enhancing the Legislative and Regulatory Framework

The government has continued to strengthen and modernize the AML/ATF legislative and regulatory framework to keep pace with new risks, market developments, and international standards.

Based on assessments of risk, additional businesses have been added to the AML/ATF Regime, such as virtual asset service providers, foreign money services businesses (MSBs), crowdfunding platforms, payment service providers, mortgage lending entities, and armoured car companies.

In every Budget since 2019, the government has announced measures to combat money laundering and terrorist financing, including legislative amendments to strengthen the AML/ATF Regime. These changes include amendments to the Criminal Code to add the fault element of recklessness to the money laundering offence, as well as amendments to the PCMLTFA to enhance FINTRAC's ability to share financial intelligence with federal partners, increase criminal penalties, and strengthen MSB registration requirements.

Most recently, in Budget 2023, the government announced its intent to introduce legislative amendments to the Criminal Code and the PCMLTFA to strengthen the investigative, enforcement, and information sharing tools of Canada's AML/ATF Regime.

These legislative changes would:

- Give law enforcement the ability, based on prior judicial authorization, to seize digital assets that may be confiscated as the proceeds of crime;

- Enhance the ability of Attorneys General to obtain, with prior judicial authorization, tax information for the purposes of investigating offences that give rise to proceeds of crime, by expanding the number of serious offences for which this measure would be available;

- Improve financial intelligence information sharing between law enforcement and FINTRAC;

- Introduce a new offence for structuring financial transactions to avoid FINTRAC reporting;

- Strengthen the registration framework for MSBs to prevent their abuse and criminalize the operation of unregistered MSBs;

- Establish powers for FINTRAC to disseminate strategic analysis related to the financing of threats to the safety of Canada;

- Provide whistleblowing protections for employees who report information to FINTRAC;

- Broaden the use of non-compliance reports by FINTRAC in criminal investigations; and

- Set up obligations for the financial sector to report sanctions-related information to FINTRAC.

Budget 2023 also announced the government's intent to make legislative changes to ensure it has the tools to protect the integrity and security of the Canadian financial sector in response to evolving threats, such as foreign interference. This includes changes to the PCMLTFA that would:

- Provide new powers under the PCMLTFA to allow the Minister of Finance to impose enhanced due diligence requirements to protect Canada's financial system from the financing of national security threats, and allow the Director of FINTRAC to share intelligence analysis with the Minister of Finance to help assess national security or financial integrity risks posed by financial entities;

- Improve the sharing of compliance information between FINTRAC, OSFI, and the Minister of Finance; and

- Designate OSFI as a recipient of FINTRAC disclosures pertaining to threats to the security of Canada, where relevant to OSFI's responsibilities.

The government has also modernized and strengthened Regulations made under the PCMLTFA on a regular basis. In 2020 and 2021, significant regulatory amendments came into force that re-organized the main Regulations under the PCMLTFA and updated and modernized many obligations. This included requirements related to performing client due diligence, verifying beneficial ownership, and identifying politically exposed persons.

Consultations on the latest round of proposed regulatory changes recently concluded on March 20, 2023. The draft regulations, once in force, would:

- Impose AML/ATF obligations on mortgage lending entities and the armoured car sector;

- Enhance the MSB registration framework;

- Improve due diligence and ongoing monitoring with regards to correspondent banking relationships;

- Increase cross-border currency reporting penalties;

- Streamline requirements for sending documents related to Administrative Monetary Penalties to reporting entities, and

- Prescribe a formula for FINTRAC to assess the expenses it incurs in the administration of the PCMLTFA against reporting entities.

Investments in Operations

Since 2019, the government has made investments of $319.9 million, with $48.8 million ongoing, to strengthen data resources, financial intelligence, information sharing and investigative capacity to support money laundering investigations in Canada.

Significant funding has gone to FINTRAC, including $89.9 million over five years and $8.8 million ongoing as part of Budget 2022. This investment will enable FINTRAC to implement new AML/ATF requirements for crowdfunding platforms and payment service providers; support the supervision of federally regulated financial institutions; continue to build expertise related to virtual currency; modernize its compliance functions; and update its financial management, human resources, intelligence, and disaster recovery systems.

As Canada's financial intelligence unit and AML/ATF regulator, FINTRAC plays a key role in helping to combat money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada and internationally. In 2021-22, FINTRAC provided 2,292 unique disclosures of actionable financial intelligence to law enforcement and national security agencies in support of money laundering and terrorist financing investigations across Canada and around the world. This included 757 financial intelligence disclosures related to Canada's public-private partnerships created to combat money laundering in British Columbia, human trafficking for sexual exploitation, online child sexual exploitation, the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, and romance fraud. FINTRAC intelligence disclosures can contain information from hundreds or thousands of reports received from reporting entities. In 2021-22, FINTRAC contributed to 335 major, resource-intensive investigations in Canada, and many hundreds of other investigations at municipal, provincial and federal levels, as well as internationally. Significantly, 97 per cent of the feedback that FINTRAC received from law enforcement and national security agencies in 2021-22 indicated that its financial intelligence was both valuable and actionable.

Project Collector: Dismantling a money laundering organization

In November 2022, FINTRAC's financial intelligence was recognized by the Alberta Law Enforcement Response Team (ALERT) in relation to Project Collector, a three-year investigation that resulted in the dismantling of a third-party money laundering organization that was working in support of some of Canada's largest crime groups. Seventy-one charges were laid against 7 suspects, including participation in a criminal organization and laundering proceeds of crime. Charges were also laid under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act. In announcing the charges, police said that they "relied heavily on intelligence from FINTRAC."In 2020, the government announced $19.8 million over five years for the RCMP to create new Integrated Money Laundering Investigative Teams (IMLITs) in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec. As the IMLITs began to ramp up in 2021, the teams integrated specialized investigative resources from partners across Canada's AML/ATF Regime to undertake money laundering investigations and reduce the capacity of, and increase the costs to, organized criminals and crime groups through the removal of their assets.

The RCMP also leads Integrated Market Enforcement Teams (IMETs). These special units detect, investigate, and deter capital markets fraud, which is a form of financial crime that can be associated with money laundering. The IMETs promote compliance with the law in the corporate community and assure investors that Canada's markets are safe and secure. The IMET Initiative is a partnership with the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, provincial and municipal police forces, securities commissions, and market regulators. IMETs are composed of police officers, lawyers, and other investigative experts. They are deployed in the major markets of Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and Calgary to respond swiftly to major capital markets fraud.

Combatting Trade Fraud and Trade-Based Money Laundering

Until recently, customs-based commercial trade fraud was mostly understood as a series of techniques used to evade duties and taxes at the border. However, in recent years, it has become increasingly evident that trade fraud techniques can be used to manipulate global trade to conceal and move proceeds of crime across borders. This is known as trade-based money laundering.

In response to these growing concerns, in April 2020, the government created the Trade Fraud and Trade-Based Money Laundering Centre of Expertise ("the Centre of Expertise") within the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). The Centre of Expertise identifies suspected non-compliant trade and produces intelligence that CBSA officers across Canada use to confirm non-compliance and take appropriate action. This can include seizing goods and issuing monetary penalties, or referring the most serious forms of trade fraud, such as trade-based money laundering, for both customs and police criminal investigations in Canada and internationally.

The CBSA is best positioned to identify most trade-based money laundering attempts using its customs authorities and its knowledge and expertise of international trade. AML/ATF Regime partners are exploring how best to leverage the CBSA's position as Canada's trade "gatekeeper" and enable it to proactively share intelligence with law enforcement for criminal investigations, while respecting privacy laws and Charter rights.

Advanced data analytics tools to improve the CBSA's ability to detect trade non-compliance will play an important role in combatting trade-based money laundering in the future. Embracing analytics by onboarding modern tools and technology would vastly expand the CBSA's ability to proactively identify trade non-compliance and reduce dependency on external tips and leads. The CBSA has been collaborating with enforcement partners internationally to identify best practices for identifying complex trade fraud and trade-based money laundering schemes in Canada. This includes exploring the viability of establishing a "Trade Transparency Unit" in Canada (see box below). The final report of the Cullen Commission highlighted trade transparency units as a promising way to better address trade-based money laundering.

Trade Transparency Units

The United States Department of Homeland Security established the concept of trade transparency in 2004 as a tool to identify complex trade fraud and trade-based money laundering schemes through bilateral collaboration between customs services. Trade transparency is achieved through an exchange of corresponding import and export data between the United States and the trading partner's trade transparency unit. Anomalies can be detected when import declarations do not match the equivalent export declarations from the trading partner, and vice versa. These anomalies serve as investigative leads for both countries to confirm through investigative collaboration. Since 2004, the United States has signed 18 bilateral trade transparency unit agreements.

Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada

In March 2023, the government published the Updated Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada, which updates the first version from 2015.

The 2023 risk assessment assessed the money laundering threat posed by 22 profit-oriented crimes, as well as the threat posed by third-party money launderers (i.e., third parties who launder money as a service to criminals). The assessment found that transnational organized crime groups and third-party money launderers remain the key money laundering threat actors in the Canadian context. Canada's largest money laundering risks come from illicit drug trafficking, various types of fraud, especially mass-marketing fraud, and third-party money laundering. Illegal gambling, corruption, collusion, and bribery are also significant concerns. AML/ATF Regime partners are also carefully monitoring the financing risks linked to ideologically motivated violent extremist (IMVE) threat actors, including white-supremacist groups recently listed as terrorist organizations in Canada.

Understanding money laundering and terrorist financing risks contributes to the government's ability to effectively combat these illicit activities. It supports the policy-making process to identify and address vulnerabilities and potential gaps in the AML/ATF Regime. It informs operational decisions about priority setting and resource allocation, helping to focus on those threats with the greatest economic, social, and political consequences. It also helps the private sector, especially reporting entities, apply risk-based approaches and mitigate their risks.

Regime Strategy and Performance Measurement Framework

In March 2023, the Department of Finance published Canada's Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime Strategy 2023-2026, which sets out the government's plan to combat money laundering and terrorist financing over the medium term, including actions to improve performance and outcomes. This consultation paper aligns with the priorities of the Regime Strategy.

The government also published the Report on Performance Measurement Framework for Canada's AML/ATF Regime. Findings from this report have helped to inform priority areas of focus for this consultation paper to improve the results of the AML/ATF Regime.

The report found that, as of 2019-20, the AML/ATF policy framework continues to be improved on a regular basis but identified gaps in corporate beneficial ownership transparency and the mitigation of money laundering risks in the legal profession. The report noted the AML/ATF Regime's increased efforts to promote preventive measures among reporting entities, which has led to FINTRAC receiving more transaction reporting, particularly suspicious transaction reporting. This provided FINTRAC with more information that could be turned into actionable tactical and strategic intelligence, although available resources and the quality of the reporting can affect intelligence output.

The report also noted that results for investigations, prosecutions and forfeitures declined over the past decade. Law enforcement laid few money laundering charges; most money laundering court cases ended with charges being stayed or withdrawn; and the number of convictions and guilty pleas declined. Further, there were very few forfeiture orders in connection with money laundering charges.

Chapter 3 – Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Collaboration

Combating financial and profit-motivated crimes is a shared responsibility between federal, provincial, and territorial governments. Coordinated actions across all levels of government help prevent criminals from exploiting gaps and vulnerabilities across jurisdictions.

Notably, the federal government continues to engage on advancing a pan-Canadian approach to corporate beneficial ownership transparency and has tabled Bill C-42 to finalize its commitment to establish a federal publicly accessible beneficial ownership registry.

To ensure Canada does not become a haven for financial criminals, all levels of government must intensify efforts to deter, investigate, and prosecute money laundering and terrorist financing, as well as efforts to recover proceeds of crime using criminal and civil processes. The federal government wishes to explore how differing levels of governments can better use existing tools to seize and forfeit the proceeds of crime, and the potential need for new measures, such as unexplained wealth orders, while respecting the Charter and the constitutional division of powers. Operational partnerships, joint enforcement efforts, and information sharing also play important roles.

Certain economic sectors and businesses vulnerable to money laundering, including money services businesses, provincial financial entities, the legal profession, real estate, casinos, and car dealers and other high-value goods vendors, are subject to different levels and types of provincial and territorial oversight, including self-regulation according to standards set out in provincial legislation or direct regulation by a provincial government authority. Holistic regulatory efforts across levels of government can help ensure that these sectors and businesses effectively understand and mitigate money laundering risks.

The federal government seeks to collaborate more closely with provinces and territories on cross-governmental issues related to money laundering and terrorist financing, including on the priority areas below.

3.1 – Beneficial Ownership Transparency

The use of anonymous Canadian shell companies can conceal the true ownership of property, businesses, and other valuable assets. With authorities unable to ascertain their true ownership, these shell companies can become tools of those seeking to launder money, avoid taxes, or evade sanctions.

To address this, the federal government committed in Budget 2022 to implementing a public, searchable beneficial ownership registry of federal corporations by the end of 2023. This registry will cover corporations governed under the Canada Business Corporations Act, and will be scalable to allow access to the beneficial ownership data held by provinces and territories that agree to participate in a pan-Canadian registry.

Building on previous amendments, in March 2023, the government tabled Bill C-42 to amend the Canada Business Corporations Act and other laws, including the PCMLTFA and the Income Tax Act, to implement a publicly accessible beneficial ownership registry.

Recognizing the shared responsibility of federal, provincial, and territorial governments for incorporation law, a federal-provincial-territorial working group has collaborated since 2016 on measures to increase beneficial ownership transparency. As a result of this work, most provinces and territories have amended their legislation to require corporations to maintain records about their beneficial owners. The working group continues to meet regularly to advance beneficial ownership transparency objectives, notably the means and mechanisms through which provinces and territories who choose to participate in a pan-Canadian registry could do so.

The federal government will continue calling upon provincial and territorial governments to advance a pan-Canadian approach to beneficial ownership transparency. The government remains committed to a collaborative, harmonized approach to the collection and reporting of beneficial ownership information, while respecting our provincial and territorial responsibilities for corporations.

The Cullen Commission's final report states that governments should not focus their efforts solely on improving the transparency of corporations and notes the largely unmitigated money laundering risks associated with trusts and limited partnerships. Unlike corporations, the responsibility for partnerships falls exclusively under provincial and territorial legislation. Quebec's public beneficial ownership registry, launched, on March 31, 2023, covers not only corporations incorporated in Quebec but also all other legal entities registered to do business there, including partnerships. As progress is made on the transparency of corporations in Canada, criminals may shift their activities towards entities such as partnerships. The federal government will therefore consult with provinces and territories on approaches to access beneficial ownership information for partnerships.

The government passed Bill C-32, which received Royal Assent on December 15, 2022, to require trusts to file additional beneficial ownership information as part of their annual income tax return. Starting in taxation years ending after December 30, 2023, trusts will have to report the identity of all trustees, beneficiaries, and settlors of the trust, along with each person who has the ability (through the trust terms or a related agreement) to exert control or override trustee decisions over the appointment of income or capital of the trust (e.g., a protector). This change improves the collection of beneficial ownership information with respect to trusts and helps the CRA assess the tax liability for trusts and its beneficiaries.

Given the money laundering risks associated with real estate, the lack of access by authorities to beneficial ownership information in this sector is a potential gap in the AML/ATF Regime. Canada does not have a pan-Canadian land registration system. Registration of private residential property ownership falls under provincial and territorial jurisdiction, and land registration systems generally do not contain beneficial ownership information. However, British Columbia launched its Land Owner Transparency Registry on November 30, 2020. It requires all corporations, trustees and partners who purchase land in British Columbia to disclose their interest holders by registering a transparency report with the searchable registry. In Budget 2022, the federal government announced its intention to work with provincial and territorial partners to advance a pan-Canadian approach to a beneficial ownership registry of real property.

3.2 – The Legal Profession

The potential money laundering risks within the legal profession have been well-documented in Canada, including in Dirty Money – Part 2 by Peter German and Associates, the Cullen Commission's final report, and the Updated Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada. These findings are consistent with results from other countries and international reports, such as the FATF's report titled Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Vulnerabilities of Legal Professionals.

In 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada rendered a decision stating that the regulatory requirements of the AML/ATF framework, as they applied to the legal profession, violated the Charter. The Court acknowledged the important public purpose of Canada's AML/ATF Regime, and that Parliament could impose obligations on the legal profession that are within constitutional boundaries.

The lack of inclusion of the legal profession in Canada's AML/ATF framework was considered a major deficiency in the FATF's 2016 evaluation of Canada.

Provincial and territorial law societies regulate the legal profession in the public interest, including for AML/ATF purposes. Since June 2019, the government has worked closely with the Federation of Law Societies of Canada (the Federation) to explore issues related to money laundering and terrorist financing in the legal profession and strengthen information sharing between law societies and the Government of Canada. The government will continue working with the Federation on this collaborative approach.

As the legal profession and law societies fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction, the federal government will also consult with the governments of provinces and territories on AML/ATF issues in the legal profession. Additionally, the Departments of Finance and Justice will monitor the ongoing efforts of the province of British Columbia to modernize their framework for legal service providers and consult with the province and stakeholders if necessary for any matters related to the AML/ATF regulation of British Columbia notaries under the PCMLTFA.

3.3 – Civil Asset Forfeiture

The FATF calls for countries to adopt measures that allow authorities to seize or restrain laundered property, proceeds of crime, and funds used or intended for terrorist activities. The FATF also calls for measures authorizing forfeiture absent a criminal conviction to the extent that this approach to forfeiture is consistent with fundamental principles of domestic law, such as human rights or other constitutional obligations.

While the federal government is responsible for criminal forfeiture, provincial and territorial governments have jurisdiction over civil forfeiture in most cases. Both criminal and civil forfeiture regimes can act as powerful means to disrupt and deter crime. They can also serve to compensate crime victims and fund anti-crime initiatives.

Although Canada has criminal and civil forfeiture laws in place, the AML/ATF Regime has been criticized for giving insufficient priority to the forfeiture of proceeds of crime and offence-related property and failing to demonstrate results in this area. The federal government seeks to explore how governments can better use existing tools to seize and forfeit the proceeds of crime, and the potential need for new measures, such as unexplained wealth orders, while respecting the Charter and the constitutional division of powers.

Unexplained Wealth Orders

Unexplained wealth orders are court orders that compel a person to provide information about their interest in specific property, such as the nature and extent of their interest and the provenance of the property, where a designated government authority has established a suspicion that the property is associated with unlawful activity. If the person does not respond or does not account for the provenance of the property, this failure to account for the property could support an application for a civil forfeiture proceeding. It could establish a presumption that the property is associated with unlawful activity and eligible for forfeiture, which could be rebutted by the owner or a person with an interest in the property. Such measures have been adopted in the context of civil recovery schemes in other jurisdictions, including the United Kingdom and Australia.

The Cullen Commission's final report recommended the Government of British Columbia develop and integrate unexplained wealth order powers into its provincial civil forfeiture regime. The Government of British Columbia has passed legislative amendments to introduce an unexplained wealth order regime. Manitoba is currently the only other province in Canada whose civil forfeiture regime provides for a form of unexplained wealth order.

The federal government will hold further exchanges with provinces and territories on establishing unexplained wealth orders as part of their civil forfeiture regimes, and how to make better use of existing tools with the objective of increasing the forfeiture of proceeds of crime and other unlawful activity. The government also welcomes views on whether and how unexplained wealth order measures could be incorporated into the federal legislative framework, taking into consideration constitutional considerations.

Chapter 3 Discussion Questions

The government is seeking views on:

- How can different orders of government work together better to address money laundering and terrorist financing?

- How can different orders of government better collaborate and prioritize AML/ATF issues related to beneficial ownership, the legal profession, and civil forfeiture?

- Are there examples of successes in other jurisdictions that Canada should consider? Are there examples of approaches in other jurisdictions that Canada should avoid?

- Are there other areas or issues related to money laundering and terrorist financing that could benefit from greater federal, provincial, and territorial engagement?

- The government is seeking views on whether unexplained wealth order measures could be incorporated into the federal legislative framework. What could be the options? What would be the benefits? What would be the drawbacks?

Part II - Operational Effectiveness

The hallmark of an effective AML/ATF Regime is one that mitigates risks to which the country is exposed and delivers results commensurate to the risk level. A strong, comprehensive legislative and regulatory framework is foundational to this effort, but it must also be backed up by effective operational actions that target areas of greatest risk.

By certain metrics, Canada's AML/ATF Regime struggles to be effective. For instance, federal money laundering and terrorist financing charges, convictions, and forfeiture of proceeds of crime have all decreased over the past decade, which is not in line with Canada's risk profile. Both the FATF and the Cullen Commission criticized the AML/ATF Regime for its lack of operational effectiveness in these areas.

This section explores potential policy measures and changes to legislation to better support operational actions, including facilitating investigations and prosecutions into money laundering, terrorist financing, and associated criminal activity. Chapter 4 considers areas for possible criminal law reforms under the Criminal Code for which the Department of Justice seeks input including the seizure and forfeiture of proceeds of crime and digital assets and on the offence and sentencing for money laundering. Chapter 5 outlines considerations for a new Canada Financial Crimes Agency that would be Canada's lead enforcement agency in financial crimes. Chapters 6 considers enhancing information sharing to better facilitate the detection and disruption of money laundering and terrorist financing, while protecting privacy rights.

Chapter 4 – Criminal Justice Measures to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

In addition to the issues highlighted elsewhere in this report where the Department of Justice is seeking input in coordination with other federal regime partners, the Department of Justice is seeking views on possible reforms to the Criminal Code, the Canada Evidence Act, and related measures that fall under the mandate of the Minister of Justice in this chapter.

4.1 – Investigation and Prosecution of the Offence of Laundering Proceeds of Crime

The offence of laundering proceeds of crime is set out at section 462.31 of the Criminal Code, which makes it an offence to deal with property or proceeds of property with the intent to convert or conceal the property, and knowing, believing or being reckless to the fact that the property was obtained through the commission of a designated offence in Canada or an act or omission outside of Canada, that if it had occurred in Canada, would have constituted a designated offence. A designated offence is any offence that may be prosecuted as an indictable offence and includes hybrid offences, with the exception of a small number of offences from eight federal statutes which have forfeiture provisions tailored to the subject matter of the statutes.

"Third party money laundering" (or launderer) (TPML) is the term used to describe the laundering of proceeds of crime as a service and for a fee, and where the launderer is generally not involved in the commission of the predicate offence. The TPML provides expertise to convert money or other form of property, or to conceal the nature, source, location, ownership, or control of property. They can rely on techniques including complex webs of transactions through various corporate vehicles and financial instruments, involvement in money service businesses (MSBs) or trade-based money laundering, engaging 'money mules' to structure financial transactions, or moving money through various cryptocurrencies and related applications. TPMLs may draw on the skills or influence of professionals, who may be unwittingly involved or complicit, or may belong themselves to a regulated sector or profession, or specialized area of business.

The FATF has found that many countries are not investigating and prosecuting third party or complex laundering of proceeds to the extent that it considers necessary in light of the ability of TPML to move large amounts of proceeds of crime through the international financial system, and the risks that this entails. However, while TPMLs may not be involved in the commission of the predicate offence, they are generally aware that the property that they move is not legitimate. Hence, prosecutions have demonstrated that the TPML was willfully blind to the fact that the property was proceeds of a specific predicate offence or had knowledge that the property was obtained from a type of predicate offence based on their clients' activities.

Investigations into laundering of proceeds of crime, particularly by TPMLs, can be complex and require specialized expertise. These factors can strain resources and budgets. Prosecutions also frequently require specialized skills and experience. In recent years, the Government of Canada has taken multiple actions to mitigate the risks of TPML. These include: new regulations targeting foreign MSBs and virtual asset service providers under the PCMLTFA; amendments to the Criminal Code to include a lower mental element of recklessness for the money laundering offence; the establishment of Integrated Money Laundering Investigative Teams under the RCMP; and the establishment of a Trade Fraud and Trade-Based Money Laundering Centre of Expertise at the CBSA. Budget 2023 also announced proposed legislative amendments to establish new offences in the PCMLTFA for structuring financial transactions to avoid triggering FINTRAC reporting and operating an unregistered MSB.

The Cullen Commission observed that the 2019 amendment to the laundering of proceeds offence in the Criminal Code, and the clarification by courts that the mental element of "belief" does not require establishing that the property was in fact derived from the commission of a designated offenceFootnote 1 will be useful in prosecutions of TPMLs. The Cullen Commission also pointed to resourcing and prioritization challenges with law enforcement and prosecutors as the main challenge underlying the low rate of investigations and prosecutions of money laundering and made recommendations in this regard.

Nevertheless, some have called for additional reforms to address TPML, such as altering the requirement to establish a nexus between the predicate offence and the laundering or focusing only on particular typologies of money laundering.

The government is seeking views on approaches to the offence of laundering proceeds of crime:

- Should the offence of laundering proceeds of crime be amended to better address third-party money laundering, such as by altering the nexus required between the predicate offence and the laundering activity?

- What would such a reform look like from your perspective?

- What would be the benefits to such reforms?

- What would be the drawbacks to such reforms?

- Could operational approaches enhance outcomes? What would such approaches entail?

- Are efforts needed to enhance education, awareness, and reporting to authorities among at-risk groups and sectors to better address third-party money laundering?

- Is enhanced capacity building for criminal justice system participants needed to better address third-party money laundering? What could this look like?

4.2 – Offences for other Economically-Motivated Crime

Frauds of varying kinds have become a concern for Canadians, particularly in recent years. When perpetrators of fraudulent schemes are located in Canada, law enforcement may be able to pursue criminal charges. In other instances, perpetrators are difficult to trace or located outside Canada, often in jurisdictions where effective legal cooperation is difficult or impossible. In some instances, funds may be recovered and returned to victims; in others, the courts may order restitution or forfeiture following a conviction. However, losses are not always recoverable.

The Criminal Code contains a number of offences that can address fraudulent conduct. For example, section 342 applies to credit card theft, including possession, use or trafficking in credit card data. Section 342.1 applies to unauthorized uses of a computer, including use of a computer with intent to commit an offence, and criminalizes activities associated with computer "hacking", as does the criminal offence under section 430 (1.1). Section 345 applies to stopping a mail conveyance, which may be relevant to schemes relying on mail. There are also the offences of false pretence or false statement (section 362), obtaining execution of valuable security by fraud (section 363), as well as forgery and false information offences. There is the general fraud offence (section 380) which applies to a broad range of circumstances where an actor has perpetrated a dishonesty and a loss, or a risk of loss, and fraud affecting a public market (section 380(2)). Canada also criminalizes identity theft (section 402.2) and identity fraud (section 403).

The government has also put in place a number of targeted responses to activities that can be associated with telephone and online frauds. The Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) regulates unsolicited telecommunications pursuant to section 41 of the Telecommunications Act. It has established Unsolicited Telecommunications Rules, including rules relating to "spoofing" caller identification by displaying inaccurate, false, or misleading information in an attempt to induce individuals to answer such calls. The CRTC can conduct compliance and enforcement actions and can issue administrative monetary penalties for violations of the Rules.

Separately, Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation (CASL)Footnote 2 contains prohibitions in relation to unsolicited commercial electronic messages (spam), computer programs installed without consent (e.g., unwanted software and malware) and unsolicited redirections (e.g., malicious interception of internet traffic). These elements of the CASL are also enforced by the CRTC through compliance and enforcement actions including administrative monetary penalties. Canada's Anti-Spam legislation also provided for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner to play a role in investigating email harvesting and spyware that collects personal information.Footnote 3

While activities associated with activities such as "phishing" and "spoofing" are illegal in Canada under existing law, some have questioned whether there might be a benefit from enacting additional criminal offences relating to these activities. The scenario of concern is where fraudsters aim to obtain personal information from individuals through telephone, text, or online means to defraud their victims.

The government is seeking views on approaches to combating fraud:

- Would additional offences in the Criminal Code effectively contribute to combating fraud, notably through "phishing" or "spoofing"?

- What would be the benefits?

- What would be the shortcomings?

4.3 – Sentencing for Laundering Proceeds of Crime

The penalty for laundering proceeds of crime is a maximum of 10 years' imprisonment when prosecuted on indictment, and up to two years' imprisonment on summary conviction. Some have called for reforms to sentencing for money laundering, suggesting that there is little deterrence and little perceived incentive to investigate and prosecute money laundering. This is due to sentencing decisions that frequently impose short incarceration periods to be served concurrently with the sentence for other offences and is particularly the case when an offender is convicted of both a predicate offence and the laundering of proceeds.

However, others point to the totality principle of sentencing, which requires that a sentence not be excessive or exceed the overall culpability of the offender, and express concern that reliance on consecutive sentencing could result in lower sentences for individual offences to respect the totality principle. In addition, research shows that the likelihood of being caught and facing prosecution may be more effective deterrents of crime than longer sentences.

An option could be to add aggravating factors to the offence of laundering proceeds of crime, for instance where the value of the proceeds is particularly high, where the offender failed to comply with professional standards, or in other circumstances. Some have called for amendments to the Criminal Code to add laundering of proceeds of crime as an aggravating factor in sentencing in cases where the accused is successfully prosecuted for another designated offence but where laundering of proceeds of crime charges were not pressed or had to be dropped.

The government is seeking views on approaches to sentencing relating to the laundering of proceeds of crime:

- Should the government consider sentencing reforms for the offence of laundering proceeds of crime?

- What could this look like?

- What would be the benefits to such reforms?

- What would be the drawbacks to such reforms?

4.4 – Access to Subscriber Information under the Criminal Code

The 2014 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. SpencerFootnote 4 significantly exacerbated the problems for police in obtaining access to information about subscribers such as name, address, phone number, and related account identifiers, such as an IP address. What constitutes "subscriber information" varies.

A tool similar to the targeted production orders in the Criminal Code that are available for transmission data, financial data, tracking data (associated with an object but not a person) and tracing information, all of which can be obtained when there are reasonable grounds to suspect, would be useful to investigators seeking subscriber information. As there is currently no tool to seek subscriber information, police must default to the general production order, at reasonable grounds to believe, which can be a challenging standard to meet at an early stage of an investigation. A related issue is that law enforcement has reported concern with the length of time provided in these orders for third parties to respond. The response time is usually set at 30 days to align with the timeframe provided in subsection 487.0193(2) for notice of an application for review of an order. In some circumstances, a 30-day wait time for a response to a narrow request, such as a request for subscriber information, can severely compromise the usefulness of the information. This delay can be compounded where several requests are submitted as an investigation proceeds and 30-day timelines multiply. Law enforcement have indicated the 30-day timeframe is common, even where consultation with the relevant entity has indicated an ability to respond in a relatively short timeline.

Although the current Canadian legal landscape is closely similar to European Union countries, Canada's practices for access to subscriber information are somewhat out of step with those of many other allied countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, which permit access to subscriber information without prior judicial approval and in short time frames.Footnote 5

Previous governments have engaged in public consultations on this issue on several occasions. Prior to the Supreme Court decision in R. v. Spencer, successive governments brought forward, in multiple legislative proposals,Footnote 6 schemes for administrative oversight frameworks for access to subscriber information consistent with how such access is authorized in many other jurisdictions. These prior legislative proposals for access to subscriber information were criticized due to privacy concerns. Many commented their concerns arose from the administrative nature of the schemes and criticized the proposals for the lack of judicial oversight. These proposals were not ultimately enacted.

The government is seeking views on:

- Should the Criminal Code be amended to include an order for subscriber information?

- What should be the extent of information available through such an order?

- Should legislative solutions be explored to address the issues raised by law enforcement regarding turnaround times?

- What would be the benefits?

- What would be the challenges?

4.5 – Electronic Devices

Electronic devices such as mobile phones can present particular challenges in the investigation of serious offences. Issues arise from the reliance on authorities such as search warrants under section 487 of the Criminal Code for searches of mobile devices, as these provisions were not developed for the digital age or for the context of modern investigative search requirements. One area that gives rise to many issues is that mobile devices may contain a significant volume of information that is useful to law enforcement, including key evidence related to the criminal activity under investigation, making effective and timely access to the content of such devices a key tool for investigators to respond to criminal activity in a timely manner. At the same time, the extent of information contained in a mobile device raises important legal considerations, including privacy rights under section 8 of the Charter. Individuals frequently carry such a device on their person, which raises distinct questions in the execution of a search. For example, in R. v. Vu, the Supreme Court of Canada indicated that a warrant that specifically anticipates that the device will be examined for its data is needed to provide the necessary authority to examine the device for data.