Part II – Leadership

On this page

- Introduction

- Recruitment

- Personnel generation and recruiting functions

- Recent recruiting shortfalls and the CAF Reconstitution

- The CAF recruitment process is cumbersome

- Efforts by the CAF to recruit women

- Additional concerns with recruitment

- Onboarding and early training

- The CAF should shorten its recruitment and onboarding processes

- CAF members must understand obligations with respect to sexual misconduct early on

- The CAF should reconsider the timing of the various recruitment screening tests

- Conclusion

- Military Training and Professional Military Education

- Military Colleges

- Human Resources

- Performance appraisal and promotions

- Career Management & Postings

- Succession planning

- Conclusion

- Input and Oversight

- The Somalia Commission’s proposed inspector general

- Recent proposals for an inspector general

- No inspector general is necessary

- Civilian courts and tribunals

- The Minister of National Defenc

- The integrated defence team and the DND

- The Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services)

- The Prime Minister and the Privy Council Office

- The Ombudsman

- Parliament and parliamentary committees

- The Auditor General of Canada

- Statistics Canada

- The media and external academics

- An external monitor is necessary

- Conclusion

Introduction

The profession of arms in Canada can only be exercised in a collective way, under government control, within a single entity: the CAF. For most of its members, the Canadian military is a lifetime career. Compared to other professions, it has a young workforce. Members enroll at an early age and hold senior positions relatively young, after approximately 20 years of service.

Their professional development is one of the CAF’s major investments. The military cannot recruit its leaders from the private sector, let alone from competitors. It is entirely dependent on itself to develop its future leaders in an environment that is at once hierarchical and competitive.

The development of leadership in the CAF is a vast enterprise that occupies a large part of its activities. It is an internally focused, detailed and sophisticated process that is heavily devoted to the management of its members’ careers. That process is responsible for ensuring professional competence as members progress in the organization. Importantly, for the purpose of my Review, it is also responsible for ensuring that it selects the right leaders, those who truly deserve the trust given to them to lead people into harm’s way.

Recruitment

Personnel generation and recruiting functions

The CAF recruitment system as it currently exists has ample room for improvement. To understand its challenges, it is helpful to know how it currently functions.

The CMP provides guidance and policies on all military human resources matters, monitors compliance within the system, and ensures personnel support is aligned and coordinated. The Military Personnel Generation (MILPERSGEN) Group has a more specific mission, which is to lead the CAF personnel generation to ensure a full complement of members in all the different environments and occupations of the CAF.

Meanwhile, the CFRG, which falls under MILPERSGEN, supports the operational capability of the CAF by attracting, processing, selecting and enrolling Canadian recruits into the Reg F, the Cadets Organizations Administration and Training Service, and Indigenous Summer Programs. The CFRG is also responsible for directing reserve applications to the appropriate reserve unit for processingEndnote 814. In addition, the Assistant Deputy Minister (Public Affairs) (ADM(PA)), and more specifically the Director of Marketing and Advertising, are responsible for recruitment advertisingEndnote 815 .

In June 2017, the Government of Canada issued its Defence Policy − Strong, Secure, Engaged. This policy document laid out the CAF’s general personnel goal of increasing its Reg F to 71,500 members and its Res F to 30,000 membersEndnote 816. This represented an increase of approximately 3,500 Reg F members and 1,500 Res F members, as well as 1,150 defence civilians, all over previously-approved levels.

The CAF’s Horizon-One Strategic Intake Plan (SIP) supports the 2017 Defence Policy, and governs the yearly targets for personnel recruitmentEndnote 817. The SIP is issued by MILPERSCOM and is a product of annual military occupational reviews. It identifies the optimal number of people to be recruited into the CAF in the specified yearEndnote 818, to ensure the necessary acquisition and maintenance of the suitable staffing levels in each military occupation for both officers and NCMs.

Additionally, the SIP takes into account the growth and contraction of occupations, size of the basic training list, attrition numbers, and occupational training capacity. As well, the SIP identifies “priority” occupations, which are defined as less than 90% of preferred staffing levels, and “threshold” occupations staffed at 90-95% levels.

Recruiting for the reserves involves a separate process. The reserve units are largely responsible for their own recruiting and basic training, which takes place either at a local unit location or a CAF training centreEndnote 819. The DAOD 5002-1, Enrolment, states that COs of primary reserve units are responsible for assessing their personnel requirements and enrolment vacancies, referring applicants to a recruiting centre to initiate the selection and enrolment process, conducting the prior learning assessment and recognition process, selecting eligible and suitable applicants, and conducting the enrolment ceremony and attestation of applicantsEndnote 820. Currently, the Canadian Army Reserve Endnote 821 conducts all its own recruiting, including processing and medicals. The Naval Reserve also conducts its own recruitment, although the medical screening is facilitated by CFRG. The CFRG processes the applications for candidates interested in the RCAF ReserveEndnote 822.

These various processes may seem well-established and smooth functioning on the surface, but in reality, they require an overhaul. I have been told that the CAF recruiting system is consistently not attracting the right people, for the right roles, at the right time. There are chronic shortages in the same occupations, and with respect to employment equity targetsEndnote 823. Due to shortfalls, particularly with respect to certain occupations, there remains considerable pressure to recruit, train and retain recruits.

Recent recruiting shortfalls and the CAF Reconstitution

Fiscal year 2019-2020 was a fairly typical year, with the CAF recruiting 5,171 new members. In 2020-2021, during the pandemic, the SIP target was 5,400, but only 2,023 recruits were onboarded. I understand that, for 2021-2022, the Reg F intake target was 6,769, but factors, including the pandemic, put a ceiling on the number of recruits that could be trainedEndnote 824. Meanwhile, according to a Canadian Army Today article, the total number of applicants grew significantly to 78,150 in 2020-2021 compared to 60,000 in 2019-2020. Total attrition was also lower than normal in 2020-2021Endnote 825. However, the CAF effectively decreased by 2,300 Reg F members in 2020-21, and currently has a “missing middle” of nearly 10,000 vacant CAF positions, many of which are at the junior officer and senior NCM and officer levels, according to CDS planning guidanceEndnote 826.

As stated by Canadian Army Today, making up for the recruiting shortfall of around 3,000 in 2020-2021 will take years. The CAF’s ability to deliver basic military training and early occupational training has an impact on its ability to onboard unusually high numbers of recruits compared to a normal year. This limits its capacity to adjust quickly when it might be possible or desirable to recruit larger numbers.

In view of the challenging personnel situation, the Acting CDS warned in July 2021 that the pandemic, attrition rates, international developments, and other changing demographics threaten to imperil the CAF’s ability to recruit, train, and retain talent. This threatens in turn the current readiness and long-term health of Canada’s military. As a result, the CDS initiated a “reconstitution” effort under which the CAF will build personnel capacity, readiness, and capabilities, to ensure its ability to protect Canadians and Canadian interestsEndnote 827.

The CAF Reconstitution Plan will form the foundation of the CAF’s activities and priorities over the next several years. It will focus on three areas:

- Prioritizing effort and resources on people – to rebuild military strength (i.e., number of personnel) while making much needed changes to aspects of CAF culture;

- Readiness – to ensure the CAF’s ability to continue to deliver on operations; and

- Modernization – to develop the capabilities and adapt CAF’s structure necessary to address the evolving character of conflict and operations

Key planning tasks for the CAF Reconstitution Plan were identified, including those directly related to the recruiting functionEndnote 829. All CAF Commands were tasked to ensure that GBA+ informs planning activities to enhance diversity and identify new measures or policies to mitigate medium to longer-term risk or negative impact on operations and members’ careers.

The MILPERSCOM was tasked to enhance recruiting capabilities, in order to fulfill both operational needs and diversity aspirations, and identify specific occupational gaps to inform prioritization of recruitment. The MILPERSCOM was also tasked to oversee streamlining component transfer, for example transferring from the Res F to the Reg FEndnote 830, and the reserve re-enrolment processes. In addition, the MILPERSCOM was tasked to lead the implementation and streamlining of decentralized basic military qualification training (this decentralization is an interim measure intended to last until basic training is recentralized within MILPERSCOM by 2022-23, with limited exceptions). The MILPERSCOM and the CPCC were jointly tasked with implementing the Women in Uniform Action Team and ensuring that all personnel generation efforts are shaped by meaningful culture change efforts.

The CAF recruitment process is cumbersome

The CAF recruits and trains candidates in their chosen occupation. Canadians can join the CAF as either officers or NCMs. Officers hold a “commission” and are responsible for planning, leading, and managing military operations and training activities in the CAF. They typically have university degrees, which are required for many officer occupations. Officers can join under the Regular Officer Training Plan (ROTP) and be selected to attend military college or a civilian university. They can also join through the Direct Entry Officer Plan (DEO)Endnote 831 if they already hold the appropriate university degree for their desired occupation. Officer occupations include, for example, pilot, aeronautical engineer, air combat systems officer, naval warfare officer, naval combat systems engineering officer, infantry/artillery/armoured officer, and logistics/legal/intelligence officer.

NCMs are subordinate in rank to officers and do not require a university education. NCM occupations can include marine technician, infantry soldier, sonar operator, cyber operator, aviation systems technician, and medical laboratory technologist, to name a few. NCMs who demonstrate the military experience and personal qualities required for service as officers can eventually be commissioned from the ranks and become officers under the Commissioning from the Ranks PlanEndnote 832. They may also become officers through the University Training Plan for NCMsEndnote 833 and be offered subsidized undergraduate education.

Candidates interested in joining the CAF may apply onlineEndnote 834, or attend one of the CAF recruiting centres across Canada. Certain steps in the application process such as the Canadian Forces Aptitude Test (CFAT) and required medical examination are done in personEndnote 835. CFRG personnel also travel to increase this outreach, and to conduct the CFAT, interviews and medical testing. In addition, the CAF covers certain expenses for applicants who have to travel a long distance to get to a detachment/recruiting center.

The recruitment process involves the following steps:

- Applicants submit an application onlineEndnote 836;

- Applicants submit required personal documentationEndnote 837;

- Reliability screening:

- Applicants fill out reliability screening forms.

- The CAF conducts reliability screening.

- This includes criminal record and background checks.

- The CFATEndnote 838:

- Applicants complete a series of three aptitude tests. Applicants are tested on verbal and problem-solving skills, and spatial ability.

- This test is conducted in person at a Canadian Forces Recruiting CentreEndnote 839.

- The CAF is working on implementing a virtual CFAT that can be administered remotely.

- The CFAT is a pass/fail test that screens out the lower 10% of applicants. The CFAT score is used to determine if an applicant is suitable for their occupation of choiceEndnote 840.

- Adaptive Personality Test:

- An Adaptive Personality Test is currently being developed and tested for use in future CAF selection proceduresEndnote 841.

- Applicants are asked to complete an online personality inventory, which provides information on personal characteristics and qualities.

- Medical examination:

- The Recruit Medical Office (RMO), part of the Director General Health Services, is responsible for the medical screening of applicants.

- CAF medical staff at a Canadian Forces Recruiting Centre will conduct a physical examEndnote 842, including measuring height and weight, evaluating vision and colour perception, and hearing. Applicants also complete a questionnaire on medical history, including specific information on medication.

- The medical file is then reviewed centrally by an RMO medical officer to determine the applicant’s medical eligibility and identify any limitations that could affect their training and career.

- In some cases, a follow-up with an outside specialist is required. This can take additional time.

- InterviewEndnote 843:

- An interview with a Military Career Counsellor (MCC) assesses the applicant’s personal qualities and life experiences.

- The interview is conducted either in person at a CFRG Detachment or virtually.

- During the interview portion of personal circumstances, the MCC covers eligibility and suitability criteria including discrimination and harassment policies, and the use of non-prescribed drugs, cannabis and alcohol use. Statements of Understanding on these policies are reviewed and signed by the applicant.

- The CAF will assess its needs and prepare a competition/merit list based on the applications and the CAF Recruiting Plan.

- Selected applicants receive an offer for engagement with the CAF.

- Prior to enrollment, applicants sign a Variable Initial Engagement (VIE) agreement.

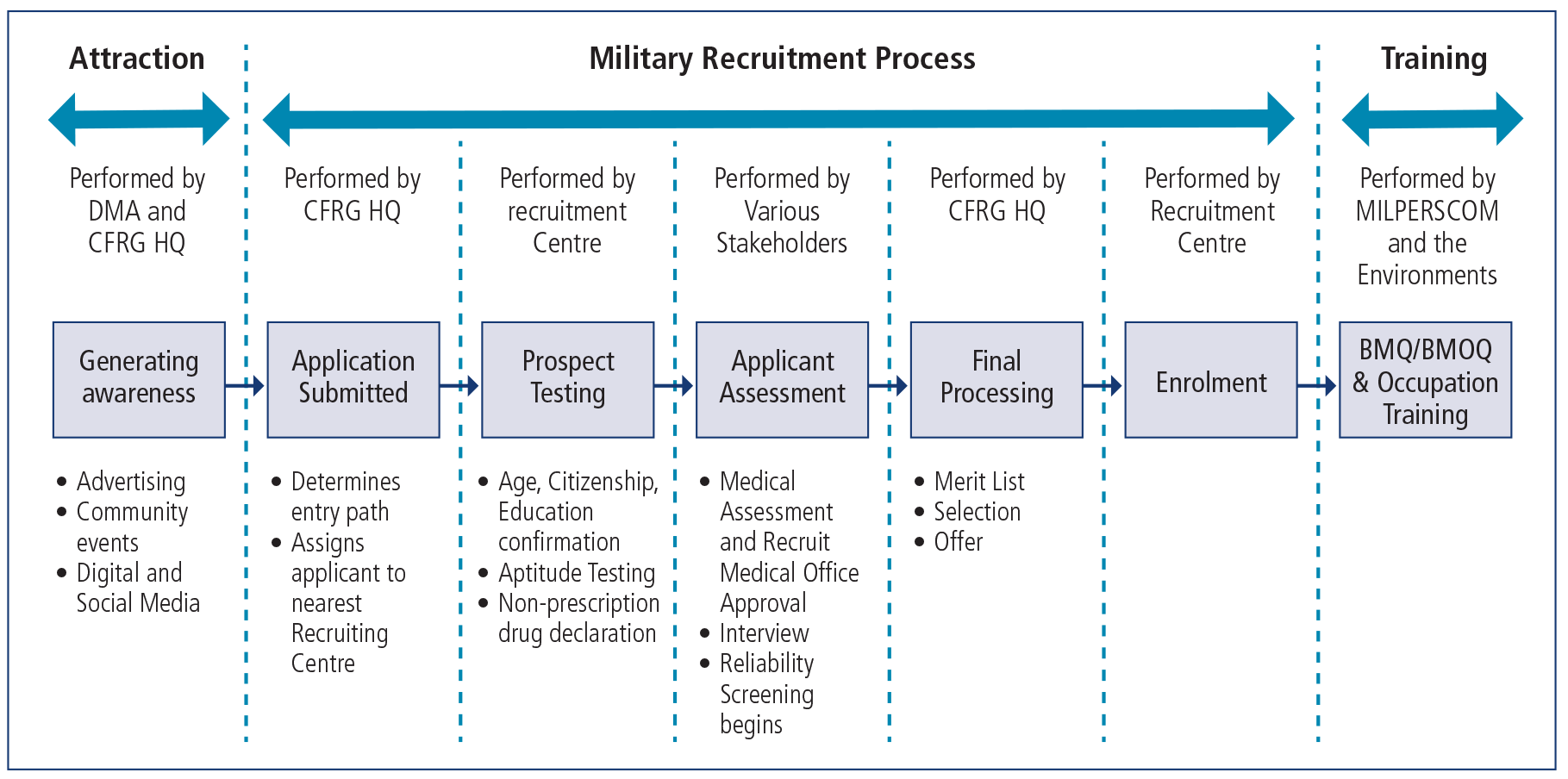

Figure 5 is a flowchart summarizing the military recruitment process, extracted from the 2019 Advisory of the Military Recruitment Process November ReportEndnote 844.

Figure 5 Long Description

- Attraction

- Performed by DMA and CFRG HQ

- Generating awareness

- Advertising

- Community events

- Digital and Social Media

- Generating awareness

- Performed by DMA and CFRG HQ

- Military Recruitment Process

- Performed by CFRG HQ

- Application Submitted

- Determines entry path

- Assigns applicant to nearest Recruitment Centre

- Application Submitted

- Performed by recruitment Centre

- Prospect Testing

- Age, Citizenship, Education confirmation

- Aptitude Testing

- Non-prescription drug declaration

- Prospect Testing

- Performed by Various Stakeholders

- Application Assessment

- Medical Assessment and Recruit Medical Office

- Interview

- Reliability Screening begins

- Application Assessment

- Performed by CFRG HQ

- Final Processing

- Merit List

- Selection

- Offer

- Final Processing

- Performed by Recruitment Centre

- Enrolment

- Performed by CFRG HQ

- Training

- Performed by MILPERSCOM and the Environments

- BMQ/BMOQ & Occupation Training

- Performed by MILPERSCOM and the Environments

- Attraction

*BMQ – Basic Military Qualification, BMOQ – Basic Military Officer Qualification

Applicants to the CAF must be “of good character.” This is determined in part by attaining an enhanced reliability status in accordance with the National Defence Security Policy. The DAOD 5002-1, Enrolment, also explicitly states that applicants must comply with CAF policies concerning sexual misconduct, alcohol-related misconduct, harassment, drugs and racism. In addition, applicants must not have outstanding obligations under the judicial systemEndnote 845.

After testing, medical exam and interview are complete, the CFRG prepares a competition/merit list based on the applications and the CAF Recruiting Plan. This list takes into account training availability, as the CAF cannot take on recruits who cannot be trained in a reasonable timeframe. Qualified applicants are selected for specific occupations and entry plans, and are then given an offer of employment within that occupation.

Enrolment, or onboarding, into the CAF involves three phasesEndnote 846. They include a pre-enrolment interview (separate from the application interview), an enrolment documentation briefing, and then finally an enrolment ceremonyEndnote 847.

An MCC or Witnessing Officer will conduct the one-on-one interview on the scheduled enrolment date and complete the CF 92 Pre-enrolment/Transfer Statement of Understanding and Update. This step confirms the applicant’s personal circumstances and ensures they fully understand CAF policies surrounding their employment. The Statements of Understanding previously signed by the applicant, including the Statement of Understanding of the summary of CAF policies on discrimination and harassment, are verified during pre-enrolment, and are confirmed by an MCC or Witnessing Officer during the interview. The CF 92 is then signed by both the MCC/Witnessing Officer and applicantEndnote 848. While the CF 92 form does not include any agreement to abide by the CAF sexual misconduct policy, applicants expressly agree in their Statement of Understanding that they will comply fully with the CAF’s policy on discrimination, harassment and professional conduct. They also acknowledge that failure to do so may lead to disciplinary and/ or administrative action, including release.

Finally, the enrolment ceremony involves taking an oath or making a solemn affirmation. It is a traditional, formal event, where candidates are encouraged to invite family and friends as witnesses.

It is widely recognized, even by the Commander of the MILPERSGEN GroupEndnote 849 , that the current recruitment process is cumbersome. Laden with steps and hoops to jump through, applicants experience significant delays throughout the process. The following observations make it clear that the system is flawed and unwieldy:

- Canada’s Defence Policy – Strong, Secure, Engaged highlights a recruiting system that is too slow to compete in Canada’s competitive labour market and does not effectively communicate the rewarding employment opportunities availableEndnote 850;

- Recruiting processes are suboptimal with delays at various points, in particular when conducting the CFAT, the medical exam and review, and the reliability status clearancesEndnote 851. The CFAT is normally completed before the applicant is scheduled for a medical or interviewEndnote 852, but some processes can take place concurrently if they are scheduled on the same day (for instance, for applicants who have travelled a far distance)Endnote 853;

- CFRG calculated that the average processing delay for enrolment in the CAF has increased in the last three years to well over 300 days from “ready for testing” to “enrolled”Endnote 854. The median processing days for the process from the completion of the CFAT to enrolment is 103 days;Endnote 855 and

- The medical screening is a particular bottleneck. I was informed that, currently, there is a four-month backlog, which represents the biggest delay in the recruitment process, as the medical file is suspended until a medical officer reviews it. In a 2019 Advisory of the Military Recruitment Process report, the RMO’s medical screening and review accounted for approximately 33% of the total delayEndnote 856. I was also told by some recruits that security clearances took considerable time, especially for those who have lived or were born outside Canada.

The CFAT has not been recently validated, and given the modern expectations of a newer generation and potential changes in CAF requirements, this test may be out of date and require re-evaluationEndnote 857.

The 2017 SSAV Report on RMC Kingston recommended that the CFAT be re-validated as soon as practicable and every five years thereafterEndnote 858. It is troubling that Indigenous applicants have been shown to score more poorly on the CFAT compared to non-Indigenous people, indicating potential test biasEndnote 859. Similarly, a concern was raised during my visit to the RMC Kingston that the CFAT may not be compliant with GBA+ and, specifically, that female varsity athletes enrol only to be screened out by the CFAT, despite having been assessed as academically suitable to attend the college by the Registrar’s office. Further, a 2020 DRDC study concluded the following:

- Male and female applicants demonstrated similar CFAT pass rates at the 10th percentile cut-off;

- There are larger differences in pass rates between male and female applicants at the higher percentile cut-off (i.e., 30th percentile); and

- Male applicants had higher total CFAT scores on average, compared to female applicants, which appears to be driven primarily by the “problem-solving” sub-test results, which are not inconsistent with mainstream findings showing gender differences in mathematical problem solvingEndnote 860.

This 2020 study recommended that the CAF conduct a differential item functioning analysis to scientifically prove or disprove gender bias of the CFAT.

Notably, current CAF recruiting processes do not formally screen candidates for issues and attitudes related to cultural diversity and sexual harassment/misconduct, although these issues are discussed during the interview.

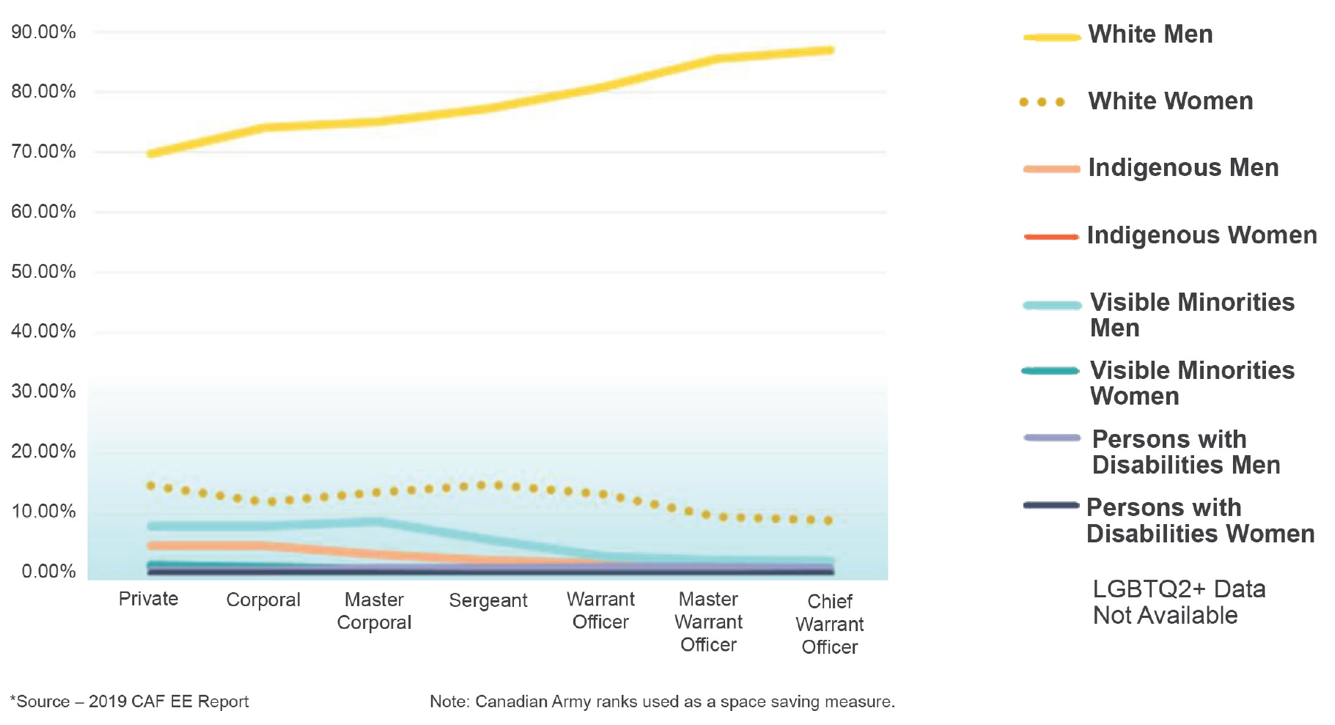

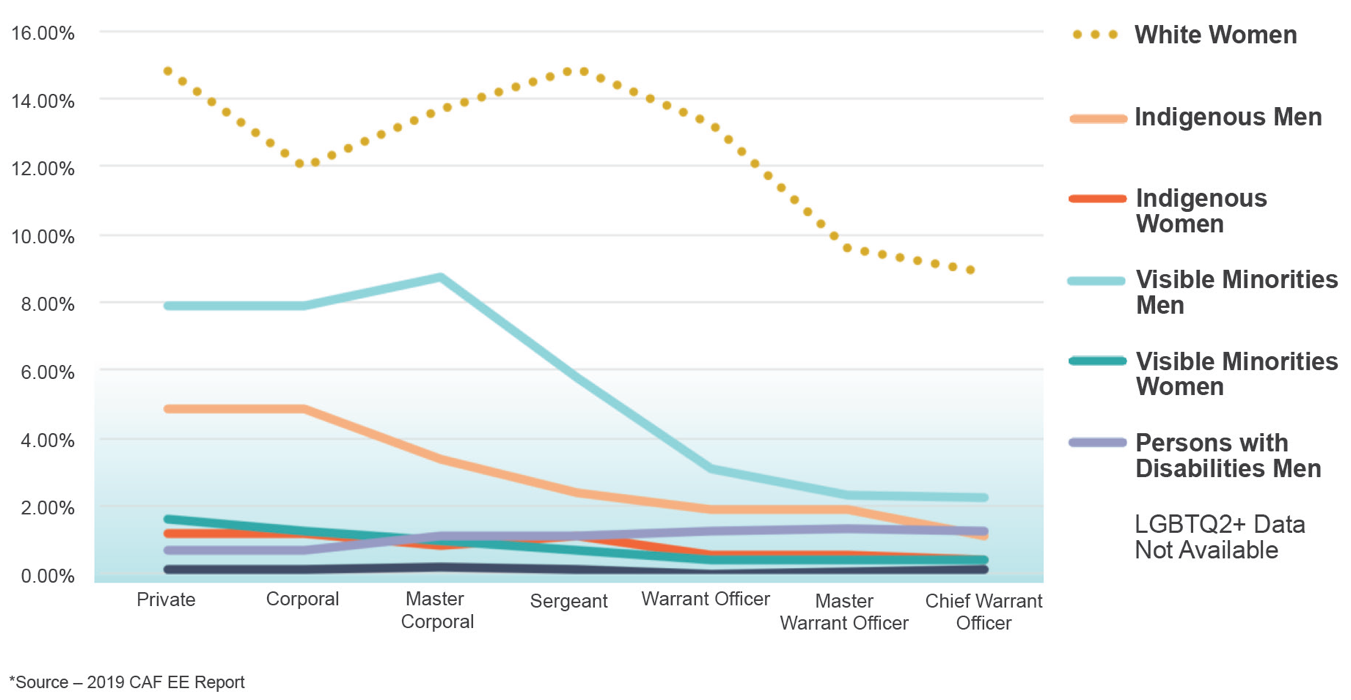

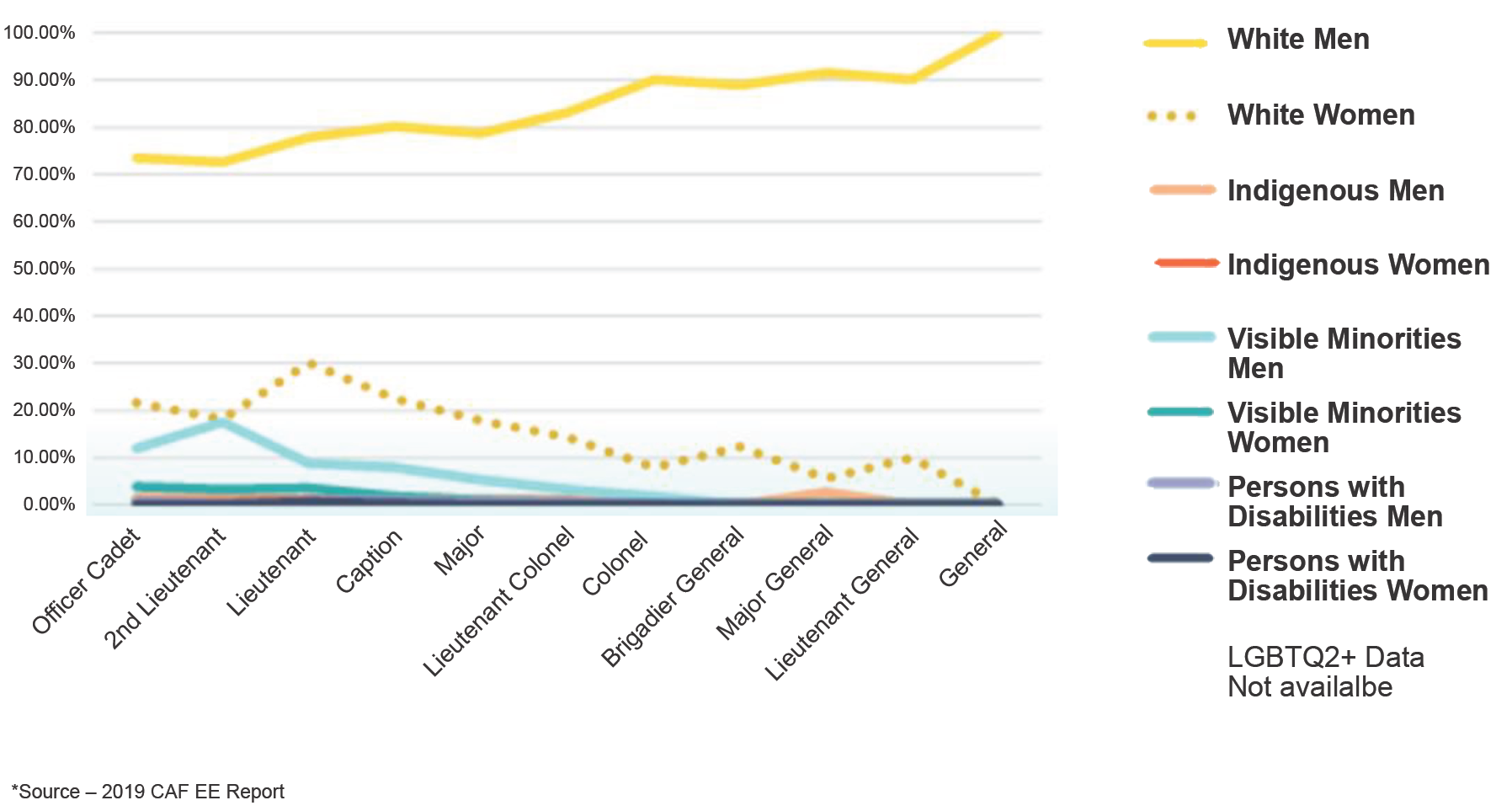

Efforts by the CAF to recruit women

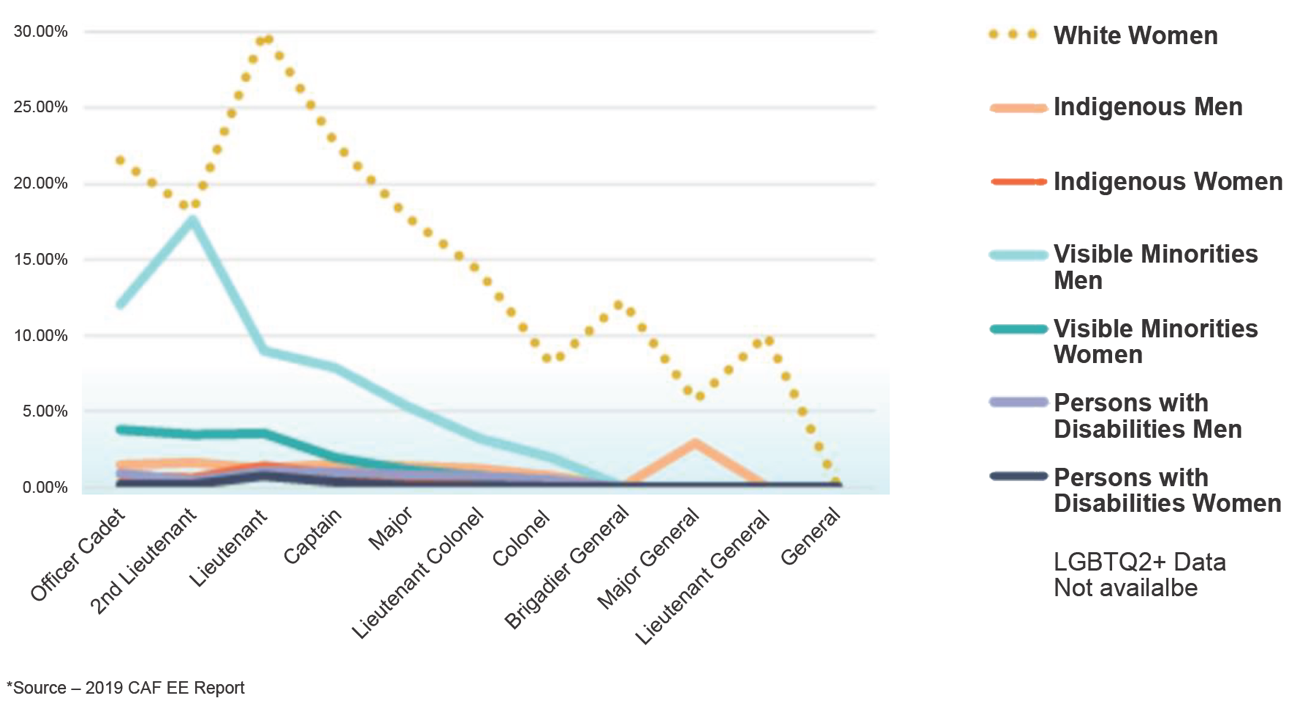

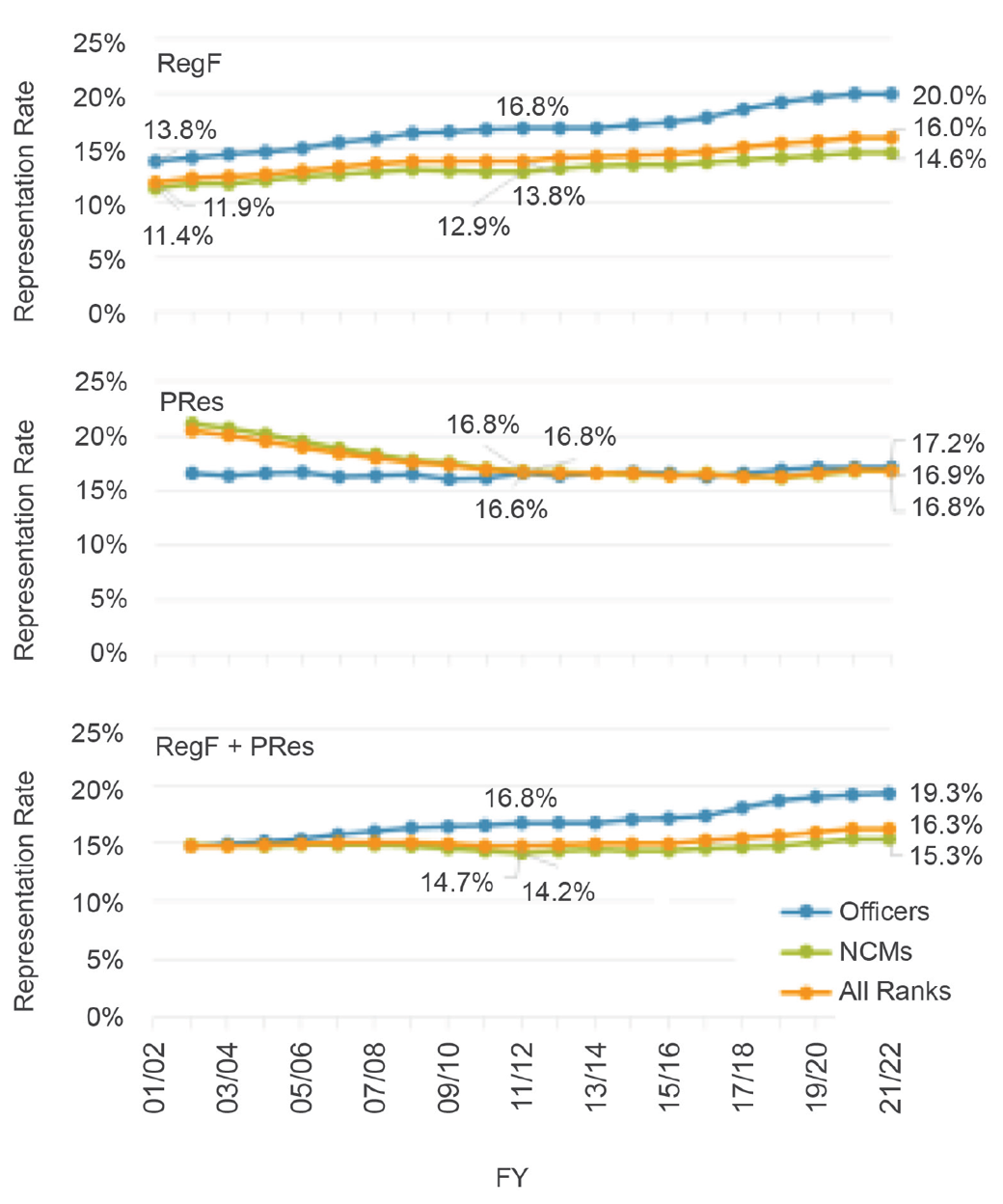

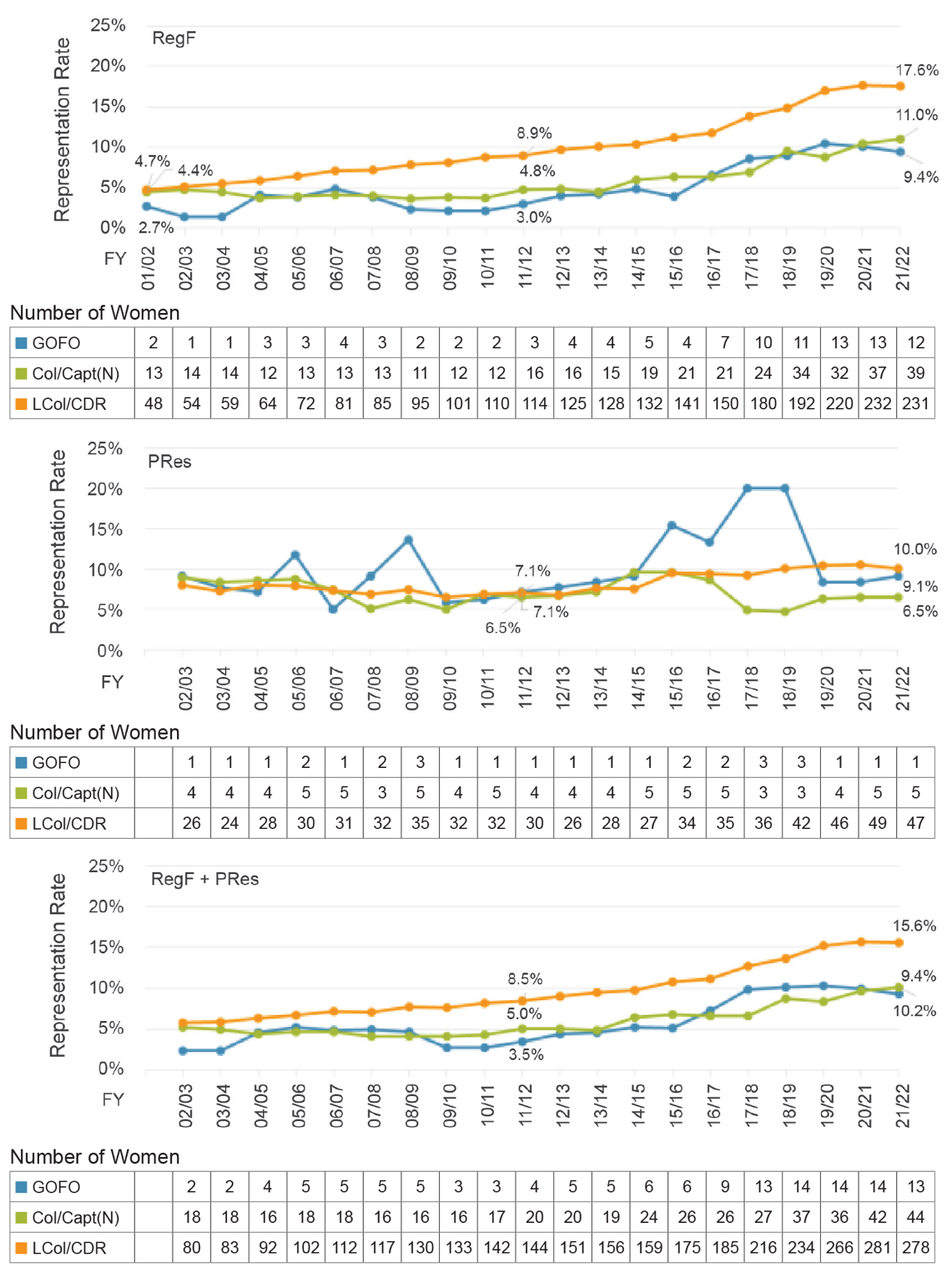

In 2016, the CDS directed the CAF to increase its population of women by 1% annually, towards a goal of 25% by 2026Endnote 861. However, according to the CAF Employment Equity Report for 2020-21, women currently represent 16% of the Reg F, 16.9% of the P Res, and 16.3% of the CAF togetherEndnote 862. Enrolment of women over the last five years has hovered at approximately 17%, according to CAF data, with the exception of 2020-21 (which may be due to the pandemic)Endnote 863. I understand that approximately 28% of applicants are women, but because 65% of women apply for the same support-related occupations, they cannot all be enrolledEndnote 864. The CAF is more successful in recruiting women for the military colleges and can meet the 25% goal for that demographic. It consistently attracts more women as officers, as a proportion of total officers, than as NCMs. For example, according to CAF data, in 2020-21, 25.9% of the officer intake were women. However, only 14.8% of the NCM intake were women. As a result, the total percentage intake in 2021-22 representing women was 17.4%Endnote 865.

In 2017, in an effort to move toward CAF’s overall 25% goal, a CFRG Tiger Team focus group produced a comprehensive list of issues and recommendations, including systemic and tactical, aimed at increasing the number of women enrolling in the CAFEndnote 866. For example:

- Redefine the “family unit” to ensure that CAF policies and allowances reflect contemporary realities and don’t discourage women with family concerns from considering the CAF as a career; and

- Ensure advertising to the Canadian public includes showcasing the CAF in humanitarian assistance roles, the restorative side of missions, and safe living conditions during deployments.

I understand that this Tiger Team report has had some influence, but was not adopted by the CAF and its recommendations were not formally tracked or implementedEndnote 867.

The Advisory of the Military Recruitment Process was subsequently set up as part of the ADM(RS) Risk-Based Audit Plan for fiscal years 2018-19 to 2020-21. The advisory extracted a representative sample of CAF application files for in-depth process tracking. It conducted interviews with key personnel to determine if attraction strategies and the recruitment process supported the CAF in achieving its targets. The advisory also examined whether enrolment processing times had been reduced. In its November 2019 report, confirming that the CAF is not meeting its priority occupation or gender diversity targets, the advisory made additional recommendationsEndnote 868. Among others, the advisory recommended that the MILPERSCOM and the ADM(PA) develop a joint national attraction agreement to document roles and responsibilities between the two organizations, as well as potential for collaboration. It also recommended developing and collecting metrics on attraction activities, to assist in more informed decision making. In addition, the advisory suggested that better tracking and understanding of applicant drop-off rates at key steps in the recruiting process would allow the CAF to better support gender diversity and broader inclusivity.

Most recently, Deloitte completed a comprehensive review of recruitment and how to implement necessary changes. It recommended the following:

- Shift to a proactive recruitment operating model focused on efficiency and candidate experience;

- Define the CAF’s talent value proposition and employer brand strategy;

- Move recruitment marketing and attraction strategy from “screening out” to “screening in” through personalization;

- Leverage leading marketing and attraction practices to increase applicants, as well as diversity in applicants by reducing the barriers to applying;

- Improve the performance measurement framework to measure the efficiency and effectiveness of recruiting activities and move towards data-driven decision-making for its recruitment function;

- Streamline the medical screening process; and

- Trial a medical screening process to demonstrate the opportunities and impediments to operating a fully digital recruitment processEndnote 869.

Additional concerns with recruitment

Talent identification and development is vital to successful culture change within an organizationEndnote 870. Ultimately, the recruitment arm of the CAF will continue to falter if bottlenecks in its multi-layered processes persist. Securing the best talent should be a top priority, and to do this the CAF must address the problematic complexity of its recruitment strategy, otherwise choice candidates will seek opportunities elsewhere. With the ongoing depletion of CAF personnel, an additional dilemma presents itself. The CAF can only recruit as many people as it can train. It is a vicious circle. With fewer trainers at hand, the recruitment process is bogged down. As part of the reconstitution effort, the CAF is currently exploring options for scaling up capacity, including instructor supply at the CFLRS, decentralizing recruit training, and enlisting the reserves in support of recruitment and/or trainingEndnote 871. However, if scarce personnel resources are redirected to the training function, this may also impact the availability of adequate personnel for domestic and international operations. It is a delicate balance, with decisions being made largely at the political level. Meanwhile, the future of female recruitment to the CAF is not encouraging. Both the CFRG and the Commander of MILPERSGEN have told me there is little to no chance that the CAF will reach 25% women representation by 2026Endnote 872. In fact, none of my interlocutors have suggested this target can realistically be met.

Both the CFRG and the Commander of MILPERSGEN have told me there is little to no chance that the CAF will reach 25% women representation by 2026. In fact, none of my interlocutors have suggested this target can realistically be met.

Female applicants to the CAF are largely drawn to support role positions (logistics officer, material management technician, human resources administrator, medical/dental technician, medical officer, nursing officer, intelligence officer, financial services administrator, steward, cook, etc.) and a limited number of Air Force occupations (aerospace engineering and aerospace control officers)Endnote 873. I understand that these positions account for only 33% of the total SIPEndnote 874.

A large contributing factor to women being drawn to these types of roles is that these are occupations which traditionally feature women. This reflects the wider trend in universities and the marketplace where women tend to congregate in, or are led into, traditionally female-dominated occupations.

Because the number of available support positions is outweighed by the number of female applicants, women are ultimately turned away. This scenario would be much different if more women were applying for roles traditionally dominated by men. This may be a difficult trend to reverse.

The dearth of female recruits, particularly in the male-dominated occupations, is not a result of poor effort on the part of recruitment centres. Quite the contrary. The centres strive to redirect women applicants to the occupations where they are most needed. We were told by several women recruits that they were advised to choose infantry or armour, as it was a sure-fire way to get accepted. Unfortunately, one senior officer said that even if the CFRG could recruit 25% women for combat arms occupations, the resistance of the combat arms community to those women recruits would make it difficult for that many women to be included in its ranks.

Women were admitted into the combat arms as a result of the Combat Related Employment of Women trials in 1987 and a CHRT order in 1989, as I set out in the section on the History of Women in the CAFEndnote 875. Since that time, their struggles have been exposed in many testimonies, including Out Standing in the Field: A Memoir by Canada’s First Female Infantry Officer, by Sandra Perron.

Not surprisingly, these entrenched barriers, combined with a history of sexual misconduct and a hostile, unwelcoming environment, can be a serious deterrent to women.

Antiquated stereotypes and sexist assumptions play a large part in the difficult integration of women into the combat arms community. Faced with scepticism about their physical capabilities or perceived difficulties with balancing work and family, many women may not even contemplate that type of work.

Not surprisingly, these entrenched barriers, combined with a history of sexual misconduct and a hostile, unwelcoming environment, can be a serious deterrent to women.

Several CAF members who reached out to me, including high-ranking officers, admitted they have doubts about staying with the CAF, and would advise their daughters not to join. Female Naval/Officer Cadets (N/OCdts) told us that they faced concern and opposition from friends and family about their intention to join an organization with such a toxic culture. On the other hand, many also said they wanted to join precisely in order to make a difference for other women – to play a small part in effecting change.

Onboarding and early training

The challenges of attracting more women to the CAF are not limited to recruitment alone. I have also learned that the way the CAF trains its new members, including BMQ and BMOQ as well as the initial occupation training, is not without its flaws. I have heard concerns about:

- the amount of pay and allowances received while on basic and other training;

- the length of time new members need to wait before, and in between, training courses;

- the fact that the CAF typically sends young recruits far away from where they were recruited without giving them adequate information, preparation or financial support (which is particularly problematic for young parents or young married persons); and

- the physical fitness standard required and whether it remains appropriate, particularly in the many occupations that do not require the same level of fitness as one would require and expect to maintain in a deployment.

These are all potential barriers to attracting otherwise good candidates to the CAF, especially women.

Recruiting the appropriate number of new members is only one dimension of the current reconstitution effortEndnote 876. The quality of recruits is arguably an even more important consideration todayEndnote 877. In the CAF’s current culture, and the culture to which it aspires, it is more important than ever to be able to attract, identify, and retain the right kind of people. This includes those with the potential to become good soldiers, aviators and sailors, but also those with the capacity to meet the moral and ethical expectations of the modern CAF. In order to properly capture these essential qualities, the recruiting and training experience needs to be reframed and adjusted, including through a screening strategy that weeds out those who do not meet expectationsEndnote 878.

There are opposing views with respect to early attrition. Some stakeholders believe the CAF should recruit the maximum number of recruits and then be ready to release recruits and junior members who do not meet the current ethical standards or display appropriate personality traits. Others believe that additional tools such as open source background verificationsEndnote 879 should be used prior to enrolment, as a way to ease the administrative burden of releasing a problem member later on.

Once new members sign the VIE during the recruitment process, they are bound to serve the CAF until lawfully released. The VIE contains a statement of the length of the initial engagement – usually three years – but can be longer for certain occupations and training plans. At the end of the VIE, members are usually offered a follow-on engagement, unless a formal administrative process is used to release the memberEndnote 880. The current CAF policy, as set out in Canadian Forces Military Personnel Instructions, does not permit the CAF to release a member who has demonstrated conduct failures, including those subject to a criminal conviction, simply by failing to offer new follow-on Terms of Service (TOS) upon expiry of their current TOS. The policy also requires the DMCA to conduct an administrative review if a member is not offered a follow-on TOS, to determine the reason, take corrective action, and direct whether TOS are to be offered to the memberEndnote 881.

The CAF should shorten its recruitment and onboarding processes

From the CAF reconstitution perspective, a holistic, system-wide effort is needed to increase the recruitment and long-term retention of properly-trained members with high morals, ethics, and potential. The CAF would benefit from re-adjusting its long-standing procedures in order to considerably shorten the onboarding process. This would create more leeway for observation and, if necessary, early release, through conditional offers of employment or a formal probation period.

A modernized recruitment process could establish a probationary period, which would permit the CAF to expedite the enrolment process, allow more in-depth evaluation during training, and also more flexibility to release members during or at the end of the probationary period.

This shift would require some structural adjustments. Presently, new recruits become full-fledged CAF members upon swearing-in, complete with full salary, benefits and computation towards pensionable public service. This includes the right to an administrative review and its promise of procedural fairness, prior to any final decision to release if a member’s TOS are not renewed. The current system relies heavily on the pre-enrolment process to make appropriate selections. The length of this process has become a disincentive for many strong candidates to join, and it is ill-adapted to the evaluation of character that is critical to a healthy organizational culture.

On releasing members, the DAOD 5019-4, Remedial Measures, already recognizes that a member awaiting or undergoing basic officer or recruit training can be released “immediately in accordance with QR&O Chapter 15, Release, for a conduct deficiency,” presumably without the same administrative burden and requirement for a progression of remedial measures to which a long-term member of the CAF might be entitledEndnote 882.

Considering the time it takes for the CAF to train its members, the end of the VIE could also be considered an appropriate point to determine whether to end a member’s service, within appropriate parameters and with procedural fairness safeguards in place.

Recommendation #20

The CAF should restructure and simplify its recruitment, enrolment and basic training processes in order to significantly shorten the recruitment phase and create a probationary period in which a more fulsome assessment of the candidates can be performed, and early release effected, if necessary.

The time required to recruit candidates using the existing cumbersome system is seriously problematic and out of step with modern human resources practices.

The CAF also needs to recognize they are in close competition with civilian employers who are vying for the same personnel. The time required to recruit candidates using the existing cumbersome system is seriously problematic and out of step with modern human resources practices. In addition, especially given the current and projected personnel shortages in the CAF, the recruitment function ties up hundreds of trained CAF members who are not experts in recruitingEndnote 883. As well, it can be argued that frontline CAF recruiters are not always the best role models to attract potential recruits. For example, some recruitment centres have no female recruitment staff or MCCsEndnote 884. With this, consideration should be given to outsourcing administrative recruitment functions to civilians in the DND or external competencies. This would have two potential advantages. It would reduce the drain of CAF personnel into the recruiting function, freeing those personnel for operational duties and helping to fill the shortages that currently exist elsewhere. And it could increase the competence level of the recruiters. Recruiters with existing experience could be hired, and the civilianization of the recruiting function would enable those employed to stay in their positions for longer and gain long-term experience in the role. Meanwhile, efforts should be concentrated on presenting a more modern and competent face of the CAF to potential candidates, in line with its more polished advertising.

Recommendation #21

The CAF should outsource some recruitment functions so as to reduce the burden on CAF recruiters, while also increasing the professional competence of recruiters.

CAF members must understand obligations with respect to sexual misconduct early on

In the CF 92 Pre-enrolment form, recruits agree to be bound by the drug policy and the physical fitness standards of the CAF, and acknowledge they could be released for breaching the drug policy or for failing to meet physical fitness standards. Prior to enrolment, they also sign a Statement of Understanding certifying they have read and understood a summary of the CAF Policy on Discrimination, Harassment, and Professional Conduct, and understand that they could be subject to disciplinary and/or administrative action, including release, for breach of the policyEndnote 885. This Statement of Understanding summarizes prohibited conduct, including the following:

Racism, personal or sexual harassment, sexual misconduct, and abuse of authority. This includes actions, language or jokes which perpetuate stereotypes or modes of thinking that devalue persons based on personal characteristics including race, colour, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, physical characteristic, or mannerisms.

Prohibited statements include those which express racism, sexism, misogyny, violence, xenophobia, homophobia, ableism and discriminatory views with respect to particular religions or faiths.

The CF 92 Pre-enrollment form should be amended to reflect the expectation that new members comply with the CAF policies on discrimination, harassment and professional conduct, as well as the DND and CF Code of Values and Ethics, and that failure to do so could result in immediate release. At the very least, it would signal that these issues are as important to the CAF as physical fitness standards. A process of expedited release should be put in place to address clear breaches of the policies during basic training or at the end of a probationary period, so as to reduce the CAF’s investment in unsuitable members. Expressions, by words or actions, of a racist, homophobic or misogynistic attitude, should be addressed early on. Taking a cue from their competence with instilling discipline, the CAF should apply similar efforts to detecting these unacceptable attitudes and behaviours. It should also reflect on whether these can as easily be corrected as deficiencies in technical skills or discipline.

The CAF should reconsider the timing of the various recruitment screening tests

During the first two weeks of basic training, recruits undertake a practice and then the formal FORCE Evaluation fitness test that includes a sandbag lift, intermittent loaded shuttles, a sandbag drag and 20-metre rushes. Recruits must pass this test in order to continue with basic training. They may be offered an additional 90 days of fitness training to pass the FORCE Evaluation, which, if they fail, signals immediate release from the CAF.

I believe the same stringent approach should be applied when evaluating other important qualifications and behaviours. Given the recruiting shortfalls and the desire to recruit the best, the CAF should consider the advantages of pushing the CFAT, required medical testing, and medical follow-up and/or reliability screening to after the onboarding point.

Failing that, adding additional vetting mechanisms to the existing process might be available, but would likely increase the complexity of the already inefficient recruitment procedures. It is not entirely clear what more could be done to effectively screen out undesirable candidates, although the CPCC is actively investigating such tools. A recent external review of sexual harassment in the RCMP concluded that the RCMP mustEndnote 886:

- Conduct effective and detailed background checks on applicants’ views on diversity and women;

- Eliminate those who are not able to function with women, Indigenous people, racialized minorities or LGBTQ2+ persons and are unwilling to accept the principles of equality and equal opportunity for all; and

- Screening must consider all incidents of harassment and domestic violence.

However, questions remain about ways to screen for inappropriate or dangerous beliefs, morals, and cultural views. In the absence of such tools, a probationary period offers a good alternative.

Recommendation #22

The CAF should put new processes in place to ensure that problematic attitudes on cultural and gender-based issues are both assessed and appropriately dealt with at an early stage, either pre- or post-recruitment.

Conclusion

These proposals are aimed at addressing the dual part of my mandate: sexual misconduct and leadership. I have focused here on attracting women and an effective and sustainable way to serve in the CAF. The solution to the problem of the inadequate recruitment of women is not simple. This is not something that mere re-branding can remedy. The problem is a systemic one that will require the concentrated efforts of the CAF as a whole. Until deep culture change takes place and the reputation of the CAF is repaired, recruiting women will continue to be a challenge.

Military Training and Professional Military Education

Current situation

The CAF training program is a substantive and well-developed system that delivers training to its members in all manner of trades and occupations. The CDA and the CAF training schools each have a role in developing and delivering this. The subjects of ethics, military ethos, harassment and sexual misconduct (including the Operation HONOUR-developed training) are now taught widely to existing and new members alike. These themes are regularly revisited as members continue training throughout their careers.

The CDA falls within MILPERSCOMEndnote 887. The CDA is the CAF training authority for common professional development training and education, such as leadership and ethical content. It is the organizational umbrella for the education group comprising the military colleges, the CFC and the Osside Institute.

The Canadian Forces Professional Development System program spans the careers of officers and NCMs in the CAF, and is a sequential development process of education, training and self-developmentEndnote 888. It provides a continuous learning environment to develop and enhance the capabilities and leadership of CAF members. This program of education is partially self-administered and based on materials produced by and for the CDA. There are five Developmental Periods (DP) in the careers of officers and NCMs alike, namely DP 1 – DP 5. For example, the BMOQ course for officers and the BMQ course for NCMs are both part of DP 1. Similarly, the syllabus for the Joint Command and Staff Programme (JCSP) given at the CFC in Toronto is drawn upon appropriate elements of the Officer Professional Military Education DP 3.

The Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School

The CFLRS is responsible for conducting basic military training for all Reg F officers and NCMs joining the CAF, as well as some Res F members. It is also responsible for some subsequent professional development programs for officers and NCMs. The CFLRS website indicates that it trains approximately 5,000 new members each year, and an additional 3,000 military members train with the CFLRS via distance learningEndnote 889. There is a ceiling to the school’s ability to conduct basic training in terms of numbers. This lack of capacity to train recruits is in part responsible for some of the current shortcomings in recruitment and limits the CAF’s ability to onboard a significantly greater number of new recruits in any given year. The pandemic has had a temporary impact on the school’s ability to conduct basic training, and the school trained only a portion of their typical numbers in 2020-21. As per its website, the CFLRS employs more than 600 military and civilian employees.

N/OCdts entering the CAF will all attend the BMOQ at the Saint-Jean Garrison, including ROTP and DEO N/OCdtsEndnote 890. The course lasts seven to 14 weeks, depending on whether cadets go to Military College, are in the Commissioning from the Ranks Plan, or are DEOs. The BMQ, the parallel basic course for non-commissioned recruits, lasts 10 weeks.

This basic military training teaches Canadian military ethos, including the Canadian military values of duty, integrity, loyalty, courage and the Canadian values of respecting the dignity of all persons, diversity, obeying and supporting lawful authorityEndnote 891. The training also covers the CAF diversity strategy, as well as harassment prevention and resolution. Classes involve ethical scenarios, guided discussions, and the consequences of non-compliance with directives and policies, such as disciplinary measures and administrative measures, including the release from the CAF. Training also discusses CAF tools available to all members, such as the RitCAF mobile application, the Defence Ethics Program websiteEndnote 892, the Member Assistance Program, and the availability of ethics and harassments counsellors.

With respect to sexual misconduct at the CFLRS, the then-CSRT-SM asked DGMPRA to administer the Survey on Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces (SSMCAF) to N/OCdts in BMOQ and recruits in BMQ, because they were not administered this survey by Statistics Canada. In 2018, DGMPRA analyzed the results of the BMQ survey, and in 2019 it analyzed the results of the BMOQ survey. DGMPRA concluded that approximately 1% of BMOQ respondents and 2.2% of BMQ respondents reported having experienced sexual assault. In total, 86.4% of N/OCdts at BMOQ and 91.2% of recruits at BMQ reported having witnessed or experienced sexualized behaviour. The most common type of behaviour reported by both groups was sexual jokes. While 37.8% of N/OCdts reported having experienced sexualized behaviour during BMOQ, 49% of BMQ recruits reported same. DGMPRA also concluded that both N/OCdts and recruits who had witnessed HISB did not always take action. The two most common reasons for not taking action included being unsure of whether the target of the behaviour was really at risk and being unsure of whether it was necessary to take actionEndnote 893.

In terms of continuing to capture this type of data at CFLRS and being able to assess progress in this area, I have been told that CFLRS currently distributes end of course questionnaires asking candidates about their overall experience. These questionnaires are called “training climate assessments” and are filled out anonymously. While there is room for complaints of any nature, they were not meant to specifically query reported or unreported sexual misconduct incidents. Given the high numbers in the SSMCAF survey, the CFLRS should be continuing to monitor for incidents of sexual misconduct, perhaps including the use of anonymous questionnairesEndnote 894.

The Canadian Forces College

CFC continues the leadership training for the CAF’s more senior officer cadre. CFC’s mission is to prepare “selected senior Canadian Armed Forces officers, international military, and public service and private sector leaders, for joint command and staff appointments or future strategic responsibilities within a complex global security environmentEndnote 895.” The CFC offers a number of intensive residential and distance learning programs directed at senior officer ranks and senior members of governments. These programs provide additional formal leadership training and more in-depth training on defence ethics, gender and diversity issues, as well as Operation HONOUR content related to sexual misconduct.

The programs include:

- Joint Staff Operations Programme for captains, naval lieutenants, majors, and lieutenant-commanders who are, or will be, employed for the first time at operational or strategic-level headquartersEndnote 896;

- JCSP designed to prepare selected senior officers of the Defence Team at the major and lieutenant-colonel rank levels and naval equivalents for command or staff appointments in the future operating environment. Students at JCSP may apply for the Master of Defence Studies program given by RMC KingstonEndnote 897 ; and

- National Security Programme for colonels, navy captains, officers of similar rank from allied nations, and senior public servants and internationals, a 10-month residential programEndnote 898.

In the JCSP, which is part of CAF’s Officer DP 3,Endnote 899 officers receive about 20 hours of formal training on leadership content related to the themes of ethics, military culture, and diversityEndnote 900. The CAF Ethos teachings include the Canadian Military values of duty, integrity, loyalty, courage (especially in the face of observing a wrongdoing), stewardship, excellence, serving Canada before self, and the Canadian values of respecting the dignity of all persons, diversity, obeying and supporting lawful authorityEndnote 901. Like the CFLRS, classes include discussion of ethical scenarios. In addition, the JCSP covers issues focused on aligning military culture with broader society, the linkages between different facets of diversity and military identity and culture, GBA+ perspectives, practical approaches for applying cultural awareness to ensure leadership effectiveness, and gender-based analysis in operational planning.

The Osside Institute

The Osside Institute is dedicated to the education of senior NCMs and runs a number of courses, which are currently given online, or via residential and/or distance learning (or a hybrid). Training programs such as the Intermediate Leadership Programme, Advanced Leadership Programme, Senior Leadership Programme, and Senior Appointment Programme,Endnote 902 are given depending on the member’s rank. For example, the Intermediate Leadership Programme is for members who are prospective Chief Petty Officers 1st class and Chief Warrant Officers, and is intended to prepare them for leadership, management and supervisory roles associated with that rank.

Military ethos and ethics

Military ethos and ethics training is a recurring part of foundational and leadership training for all CAF members. The CAF builds upon this training as officers evolve in their careers through their DPs. Duty with Honour was the foundational text that described Canada’s military ethos. The CAF is currently updating its military ethos and is finalizing a document titled The Canadian Armed Forces Ethos: Trusted to Serve.

The CAF recognizes that the military must be imbued with the Canadian values that animate a free, democratic and tolerant society. Military ethos comprises four essential Canadian military values namely duty, loyalty, integrity and courageEndnote 903. The newly updated military ethos, which I received in draft form, restates the vision as three ethical principles, six military values, and eight professional expectations. A matrix of acceptable and unacceptable behaviours will provide examples of behaviours related to each value, including the new values of inclusion and accountability.

The value of loyalty, especially to one’s comrades and the institution, appears to frequently come into conflict with the value of integrity, as evidenced by the fact that blatant and longstanding problematic behaviours have gone unreported and unaddressed over multiple decades.

These core military values are intended to guide CAF members at all times in their decisions. The value of integrity is arguably the military value that most aligns the ethical obligations of members, as set out in the DND and CAF Code of Values and EthicsEndnote 904, to the military ethos. It calls for honesty, the avoidance of deception, adherence to high ethical standards, and adherence to established codes of conduct and institutional valuesEndnote 905. Leaders and commanders, in particular, must demonstrate integrity because of the powerful effect personal example has on their peers and subordinates. The value of loyalty, especially to one’s comrades and the institution, appears to frequently come into conflict with the value of integrity, as evidenced by the fact that blatant and longstanding problematic behaviours have gone unreported and unaddressed over multiple decades. These issues only became fully and publicly apparent through disclosures in the media, class action lawsuits and formal external audits and reviews.

Sexual misconduct and related training

The Deschamps Report made the following findings regarding the CAF training related to sexual misconduct at that time:

Members of the CAF receive mandatory training at regular intervals, including on prohibited sexual conduct. As a practical matter, however, this training does not seem to have any significant impact. A large number of participants reported that the classes are not taken seriously: harassment training is laughed at, the course is too theoretical, and training on harassment gets lost among the other topics covered. Power-point training is dubbed “death by power-point”, and training on-line is severely criticized. A number of interviewees also expressed scepticism about unit-led training: there is a common view that in many cases the trainers were themselves complicit in the prohibited conduct. Participants reported that COs are insufficiently trained and that they are unable to appropriately define, assess and address sexual harassment.

Overall, the ERA found that the training currently being provided is failing to inform members about appropriate conduct, or to inculcate an ethical culture in the CAF. Rather, current training lacks credibility and further perpetuates the view that the CAF does not take sexual harassment and assault seriouslyEndnote 906.

The Deschamps Report made the following recommendations to address sexual misconducts:

Training on inappropriate sexual conduct should be a stand-alone topic and should be carried out by skilled professionals in small groups utilizing interactive techniques. Unit-led training should be limited, and on-line training should only be used for non-commissioned members when accompanied by interactive training. Leaders should also be required to undertake regular training on inappropriate sexual conduct and their responsibilities under the relevant policies. Training for military police should include a focus on victim support, interviewing techniques, and the concept of consent. Physicians, nurses, social workers and chaplains would also benefit from increased training on how to support victims of inappropriate sexual conductEndnote 907.

In response to the Deschamps Report, Operation HONOUR training, specifically content addressing the issue of sexual misconduct, was developed and communicated broadly across the CAF since the launch of Operation HONOUR in August 2015. As set out in the DAOD 9005-1, Sexual Misconduct Response, “COs or their delegates must provide Operation HONOUR training and education on an annual basis in accordance with their annual training planEndnote 908.” The CAF announced on 24 March 2021, that Operation HONOUR “has culminated and is being gradually closed out”Endnote 909. This content is to be incorporated into the CAF’s training plans going forward.

I note that the DAOD 9005-1 requires that sexual misconduct policy and related resources must be made known to:

- all applicants on enrolment in the CAF;

- CAF members during recruit and basic officer training;

- CAF members on military occupation qualification training;

- CAF members on leadership courses; and

- CAF members prior to and after deploymentEndnote 910.

Operation HONOUR, inclusion and diversity training is provided in the first three career DPs (DP1, DP2 and DP3) through the common professional development programs. Operation HONOUR training is included in the basic training courses at the CFLRS for NCM recruits and N/OCdtsEndnote 911 . The basic military training courses (BMQ and BMOQ) both cover harassment policies, case studies on harassment, and preventing HISB, as well as inclusion and diversity training. Recruits must also acknowledge in writing that they have read and will comply with CAF harassment policies. All candidates also receive a copy of the summary version of Duty with Honour.

This content is also given to N/OCdts at the military colleges in each academic year. In DP2, this content is again incorporated into the Primary Leadership QualificationEndnote 912 for NCMs and the Canadian Armed Forces Junior Officer Development officer trainingEndnote 913.

The CAF’s more recent adoption of the Path to DignityEndnote 914 is a change strategy intended to shift the focus of Operation HONOUR from an immediate response primarily concentrated on addressing incidents, to a long-term institutional culture change strategy designed to prevent and address sexual misconduct. The Path to Dignity is designed to align the behaviours and attitudes of CAF members with the principles and values of the profession of arms in Canada. Strategic Objective 1.1 is to “Enhance education and awareness programs throughout a career span.” The CPCC plans to work with the CDA to implement the objectives set out in the Path to Dignity, and improve existing programsEndnote 915.

Issues with the CAF Training Programs

Disconnect between CAF ethos and ethics doctrine and reality

The current doctrine upon which CAF leadership training is based is outlined in a number of manuals, many of which I have reviewedEndnote 916. Canadian military ethos, as well as CAF customs and practices, are described in Duty with Honour. The Defence Ethics ProgrammeEndnote 917 is considered a comprehensive, values-based ethics program that provides ethical guidance to both DND and the CAF. The DND and CF Code of Values and Ethics outlines the ethical principles and expected behaviours that apply to DND employees and CAF members. Similarly, the Canadian Armed Forces Ethos: Trusted to Serve will continue to set out the ethos and ethical standards expected of CAF members.

The training given to CAF members starts with the ethical principle, which is “to respect the dignity of all persons.” The “expected behaviours” related to respecting the dignity of all persons is that at all times and in all places, DND employees and CAF members shall respect human dignity and value of every person by:

1.1 Treating every person with respect and fairness.

1.2 Valuing diversity and the benefit of combining the unique qualities and strengths inherent in a diverse workforce.

1.3 Helping to create and maintain safe and healthy workplaces that are free from harassment and discrimination.

1.4 Working together in a spirit of openness, honesty and transparency that encourages engagement, collaboration and respectful communicationEndnote 918.

The DND and CF Code of Values and Ethics also states that CF members who are also in leadership roles have a particular responsibility to exemplify military values of the Canadian Forces and the common values and obligations of the Code of Values and Ethics. CAF leaders are expected to “create a healthy ethical culture that is free from reprisal, to ensure that all subordinates are given every opportunity to meet their legal and ethical obligations to act, and to proactively inculcate the values of the Code of Values and EthicsEndnote 919.”

Despite the abundance of doctrinal and training materials, events have demonstrated that ethical education in the CAF continues to fall short of its objectives. There is an obvious disconnect between rhetoric and reality.

Despite the abundance of doctrinal and training materials, events have demonstrated that ethical education in the CAF continues to fall short of its objectives. There is an obvious disconnect between rhetoric and reality. This was termed by the CFLRS as a misalignment between official values/ethos and practice – between what is taught and what is modelledEndnote 920. Put simply, the “ethical teaching” is often not taken seriously. There are a number of factors that contribute to this disconnect. Instructors who appear sceptical about the content they have to communicate, staid instruction techniques (“Death By PowerPoint”), and the contrast between “real military skills” and “soft issues” are just a few of these factors. Public exposure of leaders who have long fallen short of living by these ethical principles, and the actual composition of the classes where young white men dominate, all contribute to an entrenched culture that is at odds with the values being taught. I have heard from trainees that the attitudes and behaviours of some training school staff directly undermine the value of the ethical and cultural related content taught. One example is particularly startling. Several young women entering basic training were told that they should “get on the pill” or, worse, that they should get a prescription “for the pill that will stop their periods.” Not only is that an appalling suggestion, it also illustrates the extent to which commitment to diversity and inclusion is purely formal. Despite all the classroom training they receive about diversity, these new recruits, like most of their peers, will learn early on that what is truly expected, and rewarded, is conformity to a masculine “ethos” and elimination of the inconvenience of diversity. This is considerably at odds with Canadian values and expectations.

Training staff

In an organization like the CAF, where hierarchy and leadership are of the utmost importance, early indoctrination and cultural embrace are critical. It is not only the content of ethical training that will contribute to culture change in the CAF, but the method of delivery.

Above all, excellent teachers should provide the early phases of training, not just to the upper levels of continuing education programs. At the CFLRS, the average age of new recruits is 27. They are volunteers. They come to the CAF with preconceptions and expectations. Their first exposure to the organization is important, and there is no doubt they quickly understand the importance of discipline. At the CFLRS, they learn how to “live with their weapon,” which they carry around at all times. This is a striking example of effective messaging. In the development of what the CAF considers important, recruits should, at the outset of their training, be exposed to and taught by the very best, not by those who do not want to be there, do not believe in what they are asked to teach, and whose demeanour is completely at odds with the purported values of the organization.

Loyalty, integrity and courage are sometimes replaced by abuse of authority, pettiness, and lack of respect, conveyed to recruits by immediate superiors who are poor role models and mentors. Senior CAF members recognize that this is a serious problem. There are long-standing issues with the staffing of training schools and training positions within operational units, and using incremental (non-permanent) staff to take on these training roles. I have been told that postings to training units, instead of command positions, are seen as barriers to career progression in the combat arms community in particular. While many may understand the importance of training the next generation and are dedicated to serving in that fashion, they hesitate to take on a teaching role for fear of being denied other opportunities elsewhere.

Teaching talent should be recognized and rewarded, including by leading to greater access to and opportunities for leadership positions on par with operational postings.

This current approach needs to be reversed. Teaching talent should be recognized and rewarded, including by leading to greater access to and opportunities for leadership positions on par with operational postings. Additional incentives including a new allowance or automatic consideration for future promotion should also be weighed. In parallel, members under administrative review, or who have been the subject of disciplinary measures, should not be eligible to teach.

Recommendation #23

The CAF should equip all training schools with the best possible people and instructors. Specifically, the CAF should:

- prioritize postings to training units, especially training directed at new recruits and naval/officer cadets;

- incentivize and reward roles as CFLRS instructors, and other key instructor and training unit positions throughout the CAF, as well as the completion of instructor training, whether through pay incentives, accelerated promotions, agreement for future posting priority, or other effective means;

- address the current disincentives for these postings, such as penalties, whether real or perceived, for out-of-regiment postings during promotion and posting decisions; and

- ensure appropriate screening of qualified instructors, both for competence and character.

A potentially even more effective solution to many of these systemic problems and shortcomings would be the creation of a new trainer/educator occupation within the CAF, or a specialty within one of the support-related occupations. This would generate a permanent cadre of skilled professional trainers, who are well-suited, qualified and keen to take on this type of career and role.

When you consider the extent of the training function already present within the CAF, including the large number of training schools, training units and training positions, it is quite likely that a critical mass already exists for this idea to be seriously exploredEndnote 921. I believe that this type of change could also serve to attract a more diverse element into the CAF of the future. I understand that introducing a new occupation of trainers/educators could be perceived as a net loss for the CAF, as those trainers would seemingly be unavailable or unsuitable for deployments and military operations. However, this is an untested assumption, and it reflects the dismissive opposition towards, and lack of appreciation for, such an important role.

If given the chance, I believe the creation of this proposed new occupation could represent a ground-breaking new direction for the CAF, and those tasked with teaching would, in all likelihood, apply their knowledge and skills beyond the classroom in operations postings.

Recommendation #24

The CAF should assess the advantages and disadvantages of forming a new trainer/educator/instructor occupation within the CAF, or a specialty within one of the human resources-related occupations, in order to create a permanent cadre of skilled and professional educators and trainers.

Training for soft skills

We are often reminded that the role of the military is to fight and defend Canadians and allies in times of strife, and to support our communities during times of disaster. In reality, it is also true that the majority of CAF members do not spend their careers in combat situations. For many occupations and trades, members will be in combat zones for only a few months, if any, during their entire careers. And while it is important to train for combat, and be in a state of effective readiness, I believe soft skills are equally important. Members need communication skills, interpersonal skills, problem-solving and conflict management skills, creativity, flexibility, work ethic, mutual respect and empathy. This includes learning to speak up and communicate effectively around difficult issues (like sexual assault and misconduct), to resolve conflicts respectfully, and to help team members understand how to treat others fairly.

To the extent that these skills are considered feminine, and at odds with the warrior culture that is germane to the profession of arms, I believe this is an antiquated conception of what makes an effective modern warrior. In fact, many of the foundational documents of the CAF speak to that issue.

Operational effectiveness is often described as the overriding concern in the CAF. Interestingly, Leadership in the Canadian Forces: Leading People defines collective effectiveness as seeking five major outcomes, namely: Mission Success; Internal Integration; Member Well-Being and Commitment; External Adaptability; and Military Ethos.

Member Well-Being and Commitment is further defined as:

(...) taking care of people. This outcome is critical to mission success, in the first instance, and contributes significantly to internal integration and external adaptability. It signifies a concern for followers, the quality of their life and conditions of service, and the provision of all necessary means of force protection on operations. Commitment is both up and down, as in the member’s commitment to the CF and the CF’s commitment to its members. The Canadian Forces is its people. Demonstrating care and consideration is both a practical obligation and a moral obligation for effective CF leadersEndnote 922.

This speaks well about the necessity of further integrating interpersonal skills into the combatant culture.

Training methods

With respect to training materials, the CAF materials and outlines we have reviewed to date are largely traditional (PowerPoint slides, manuals, discussion topics, etc.). The CAF should consider new types of training on sexual misconduct, including interactive techniques. Additionally, they should look to leaders in the field with established best practices – particularly civilian institutions that are grappling with similar challenges. Finally, the CAF should consider integrating more real-world test scenarios for ethical breaches that are not flagged in advance to trainees.

I have also heard that related, specialized training is sometimes only available in English to members posted outside of Quebec. The lack of training in French could impact the effectiveness of the training and associated cultural attitudes.

Probationary period

It is the DND’s and the CAF’s ultimate responsibility as an employer to provide a safe and non-toxic work environment for its employeesEndnote 923. I am aware of the ongoing strains on the CAF’s ability to improve its training operations. Current and projected staffing shortages put pressure on the CAF and its training schools to mobilize the very best instructors. The same pressure may also lead to a willingness to retain trainees, even if they demonstrate toxic views and attitudes. Despite these challenges, when it comes to both trainees and instructors, the CAF needs to develop a better process for weeding out those individuals early.

The old “we break them and rebuild them” approach to military training still captures the confidence with which the CAF has traditionally approached its recruitment strategy. While this may serve narrow training skills .

This could be done by transforming basic training into a probationary period. I am conscious that this requires not only a change in the enlistment TOS arrangements, but a major change in leadership culture. The old “we break them and rebuild them” approach to military training still captures the confidence with which the CAF has traditionally approached its recruitment strategy. While this may serve narrow training skills objectives, it is not compatible with the more sophisticated education needed by modern members of the CAF, including at the point of entry. As such, and consistent with my recommendation above in respect of recruitment, the CAF should restructure its early training into a probationary period with provisions for early, expedited release in the event that trainees fail to show the desire or ability to meet the CAF’s ethical and cultural requirements.

Recommendation #25

The CAF should develop and implement a process for expedited, early release of probationary trainees at basic and early training schools, including the CFLRS and military colleges, who display a clear inability to meet the ethical and cultural expectations of the CAF.

External secondments

The CAF operates in an extremely self-reliant manner. While this is largely dictated by the nature of the organization, the result has implications, arguably both good and bad. In the areas of human resources management and cultural reform, the CAF, like some law enforcement agencies, is struggling to keep pace with the private sector and the civilian public service. This is evident from the time it took for the CAF to begin addressing its sexual misconduct and discrimination problem, and the relative ineffectiveness of the measures put in place so far. I believe this could be remedied, in part, by expanding opportunities for external secondments. The CAF does not have many such opportunities at the present time.

Of course, the CAF has a long history of establishing and managing military exchanges and cross postings with many international allies and other countries. I have heard from stakeholders that opportunities for such secondments are beneficial because they help members expand their first-hand knowledge and expertise. This is, however, still centered on military-related matters. The CAF should consider expanding this vision to include additional secondments to the private sector, and to other government departments, with a view to expanding leadership and management experience in fields other than strictly military.

For instance, the RCAF launched a secondment program, called the RCAF Fellowship Programme, in 2017 to develop RCAF leaders’ analytical skills and equip them with better understanding of international security and civil military affairs. Attendees are seconded outside the CAF. I understand that the Fellowship in 2022 is with Communitech, a key Canadian innovation hub collocated with the University of Waterloo. This type of external secondment provides fresh perspectives and ideas, not born within the DND, to help solve current RCAF challenges. I note that some allies have also developed secondment programs external to their militaryEndnote 924.

External secondments allow members to acquire skills and a deeper understanding of business or government, which are applied throughout the rest of their career, and which ultimately benefit the CAF. The member involved achieves a wider, more balanced perspective, gained from a new and different environmentEndnote 925.

The private corporate sector is worlds ahead of the CAF when it comes to the management of human resources, the career progression of women and minority groups, and dealing with the issue of sexual misconduct. For example, Catalyst is an international organization that deals with the promotion of women in the corporate world, and offers research and training tools and resourcesEndnote 926. Catalyst recognizes that male-dominated industries and occupations, defined as those with less than 25% women, are particularly vulnerable to reinforcing harmful stereotypes and creating unfavorable environments that make it even more difficult for women to succeedEndnote 927.