Part I – Sexual Misconduct

On this page

- Introduction

- Focus on the system

- History of women in the CAF and prevalence of sexual misconduct

- Brief history of women in the CAF

- Number of women in the CAF

- Reporting on sexual misconduct in the CAF begins

- The Deschamps Report and initial steps taken by the CAF

- The 2016 Statistics Canada Report and next steps by the CAF

- Class actions

- The 2018 Statistics Canada reports

- The 2018 OAG Report

- Surveys of the military colleges

- Conclusion

- History of Operation HONOUR

- Chief Professional Conduct and Culture

- Data

- Focus On The Offender

- Definitions of Sexual Misconduct and Sexual Harassment

- Military Justice

- Criminal jurisdiction over sexual offences

- Rights of the accused

- Disciplinary jurisdiction over sexual misconduct

- Summary trials under the current system

- Bill C-77 and the new system of service infractions

- Administrative Action

- Complaints

- Military Grievance System

- Grievances related to sexual misconduct, sexual harassment and discrimination on the basis of sex

- Current delays in processing grievances

- Exhausting remedies under the grievance system

- Concerns with the military grievance system

- Grievances related to a complaint or situation of sexual misconduct, harassment or discrimination

- Focus On The Victim

- Duty to Report and Barriers to Reporting

- Victim Support and the SMRC

- History of the SMRC

- The creation of the SMRC and the evolution of its mandate

- PGoing forward – the SMRC’s name and mandate

- The SMRC’s beneficiaries

- History of the SMRC

- Local initiatives

- Defence Advisory Groups

Introduction

The profession of arms is unique in many ways. No other self-regulated profession has the same monopoly over the conduct of its members. Lawyers, doctors, architects, all professionals are subject to two, often three, levels of accountability: the criminal courts, like all other citizens; the code of discipline of their professional body, which protects the public and oversees the profession at large; and possibly their employer, who is entitled, under certain rules, to protect its own interests and those of its employees. A lawyer may be dismissed by their employer, disbarred and sent to jail, all through separate independent, often parallel, processes.

In the military, all these processes are handled internally by way of criminal, disciplinary and employment standards. The fact that they are administered by a single entity should produce some efficiencies. Unfortunately, it has not. This is particularly evident in how the CAF addresses the issue of sexual misconduct in its ranks.

The CAF discharges these interrelated tasks through a maze of processes, the details of which are exposed throughout this Report. To paraphrase one stakeholder, the CAF has put the “activities cart” before the “conceptual horse.” They have collapsed crime and discipline, which in my view is an error when it comes to serious sexual misconduct; and yet they have kept separate disciplinary measures, said to be punitive, from administrative ones, said to be remedial, when the two are often indistinguishable, particularly given the intersection between punishment and rehabilitation.

The devil, here, is not in the details. Each stream, each silo, may function relatively well and is the subject of periodic attempts at improvement. The real problem rests on the overall structure, which produces unnecessary complexities, inefficiencies, and delays. All of this has led to mounting frustration and an erosion of trust among members, stakeholders and Canadians at large.

Important reforms can still take place under the present structure. I make recommendations to that effect. But the incremental changes of the past, and the ones that seem about to take place may not yield the optimal result that conceptual clarity from the outset would bring.

Deficient as it has been in dealing appropriately with offenders, the CAF has been even more neglectful in addressing the plight and needs of victims and survivors, who eventually had to turn to an external party, the courts, through a class action, to obtain some form of recognition and redress. Until recently, few efforts were made to address their legitimate concerns and claims.

The changes I propose in how the CAF addresses offenders will also serve to empower survivors, as they will be less at the mercy of a chain of command in which they have largely lost confidence.

Focus on the System

History of women in the CAF and prevalence of sexual misconduct

Sexual misconduct is not new in the CAF, nor is it unique to the Canadian military; it exists within many defence forces around the world and in society at large. This is not an excuse for the sorry state of affairs in which the CAF finds itself, but it does call for an understanding of the specific circumstances in the CAF that make it a “wicked problemEndnote 49.”

Despite being an endemic problem in the CAF for decades, the issue of sexual misconduct, its root causes and its prevalence throughout the ranks, was largely undocumented until relatively recently.

Brief history of women in the CAF

Women have a long history in the Canadian military, with their first integration occurring in 1885, during the North-West Rebellion. During the First and Second World Wars, women once again lined up to serve. According to a 2019 Canadian Military journal article, over 2,800 women joined the Royal Canadian Medical Corps during the First World War and, during the war years, approximately 50,000 women enlisted to serveEndnote 50. Women were prohibited from taking on a combat role, and most were employed in traditional fields where they received less pay, fewer benefits and, in some cases, operated within a separate system of rank and rules. After the war, women were dismissed from service, with the exception of nurses who continued to care for injured veteransEndnote 51.

The Cold War and the Korean War reignited the demand for servicewomen, but the CAF imposed a ceiling on the number of women permitted into the Regular Force (Reg F) and restricted them to occupations with fewer than 16 weeks’ worth of training, and in a lower pay scale than traditionally male-dominated areasEndnote 52.

In 1967, amid calls for greater gender equality in Canadian society, the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada was created. The Commission was mandated to “inquire into and report upon the status of women in Canada, and to recommend what steps might be taken by the Federal Government to ensure for women equal opportunities with men in all aspects of the Canadian societyEndnote 53.”

The Commission tabled its report in 1970. Regarding military service, the Commission noted that women had fewer opportunities to enter the CAF than men and were generally required to be older and have higher levels of education. Married women were not allowed to enter the Forces, because they were considered less free to move to new postings. Women who married after joining were generally allowed to remain in the Forces, but not if they had children. Unmarried mothers were released but may have been permitted to re-enlistEndnote 54. To resolve these inequalities, the Commission recommended that:

- women be admitted to the military collegesEndnote 55;

- all trades in the CAF be open to womenEndnote 56;

- the prohibition on married women in the CAF be eliminatedEndnote 57;

- the length of the initial engagement for which personnel are required to enlist in the CAF be the same for women and menEndnote 58; and

- release of a woman from the CAF because she has a child be prohibitedEndnote 59.

The government adopted most of the Commission’s recommendations but refused to open all military occupations to women in the belief that, for operational reasons, specific positions should only be filled by menEndnote 60.

In 1978, the Canadian Human Rights Act came into effect, which prohibited discrimination based on gender, unless for a bona fide occupational requirementEndnote 61. A year later, the government finally permitted women to attend military colleges, opening military education and increasing opportunities for womenEndnote 62.

The 1980s saw more improvements to the integration of women in the CAF, and it appeared as though the CAF were making a real effort to be more inclusive through the launch of the Service Women in Non-traditional Environment and Roles trials. These trials were conducted over five years (1979-1984) and evaluated women’s ability to function in “near combat” unitsEndnote 63. By 1987, all Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) occupations opened to women, and the CAF promoted the first women to the rank of brigadier-generalEndnote 64, the fourth highest rank in the organizationEndnote 65.

From 1987 to 1989, in response to the equality rights that came into effect pursuant to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the CAF ran the Combat Related Employment of Women trials, to evaluate the operational effectiveness of mixed gender units engaged in direct combatEndnote 66.

However, comprehensive integration remained elusive as the government continued to prohibit women from occupations and units preparing for direct involvement in combatEndnote 67. This prohibition, however, was met with opposition from women in the Defence Team, including a complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) claiming discrimination on the basis of sex, which led to a 1989 CHRT ruling that required the CAF to:

- integrate women into all aspects of the Reg F and Reserve Forces (Res F), except submarines;

- remove all employment restrictions and implement new occupational personnel selection standards; and

- devise a plan to steadily, regularly, and consistently achieve complete integration within ten yearsEndnote 68.

In 1989, the CAF opened all military occupations to women except submarine serviceEndnote 69 and improvements to female integration continued through much of the next decade. The 1990s saw the first mixed-gender warship participate in NATO exercises, the first women to serve in combat arms, the first female major-general, and the first air force squadron commanded by a woman. Additionally, in 1990, the Minister created an Advisory Board on Women in the CAF to monitor the progress of gender integration and employmentequityEndnote 70.

Number of women in the CAF

The CAF finally permitted women into all areas of the organization in 2001. Women have now reached more senior positions in the organization, with the first woman promoted to rear-admiral in 2011, and the first woman promoted to lieutenant-general in 2015Endnote 71. Since 1997, the CAF has endeavoured to have women represent 25% of membersEndnote 72, a goal that has not been reached to date. In 1989, when the government finally permitted women to serve in all occupations except on submarinesEndnote 73, women hovered at 10%, according to the DGMPRAEndnote 74. Thirty years later, this has only increased marginally. As of October 2021, women represented 17.4% of intakes and 15.8% of releases, according to CAF data and made up 16.3% of the combined Reg F and Primary Reserve (P Res), as per the 2020-2021 CAF Employment Equity ReportEndnote 75.

I do not think that the low representation of women in the CAF is due to a lack of interest on their part in wearing the uniform and serving Canada. It is evident to me that, despite legislation mandating equality, life for women in the CAF is anything but equal. Many women experience harassment and discrimination on a daily basis with one stakeholder noting, “a man can be seen as stoic and forceful and a woman is a bitch. I was told early in my career that I had three choices: to be a slut, bitch or dyke.” This uneven treatment of women, coupled with other forms of systemic discrimination and widespread sexual misconduct, feeds into poor recruitmentEndnote 76 and retention, as well as underrepresentation at all ranksEndnote 77.

Reporting on sexual misconduct in the CAF begins

In 1998, Canadians received their first real glimpse at what military life was like for women. In a series of three articles, Maclean’s exposed the existence of military sexual misconduct through the experiences of 13 victims of sexual assault. While not an exhaustive review, the articles noted that these cases could represent a larger pattern of sexual harassment and assault in the Forces. Further, these interviews revealed a systemic mishandling of sexual assault cases by noting that the “investigations were perfunctory, the victims were not believed and often they – not the perpetrators – were punished by senior officers who either looked the other way or actively tried to impede investigationsEndnote 78.”

The victims pointed to the toxic and sexist culture of the CAF as the root cause of sexual misconduct. A culture that promoted heavy drinking and the humiliation of women through degradation and violence created an environment in which women, who, at the time, accounted for 11% of members, were often little more than pawns for predators according to Maclean’sEndnote 79.

In the spring of 2014, L’actualité and Maclean’s published articles that revealed sexual assault in the CAF as rampant as it had been in 1998, and that the number of reported assaults only scratched the surfaceEndnote 80. The authors estimated that incidents of sexual assault in the CAF could be as high as five per dayEndnote 81. While this rate of sexual violence may have shocked civilians, women in the CAF had grown accustomed to being mistreated and abused. One stakeholder told me: “You wake up every day wondering if you are going to make it through the day, what name you will be called and if they will find something you cannot do.”

On the basis of these articles it was clear that the barriers to reporting, first raised in 1998, remained in place, revealing that senior leadership had taken no serious steps to resolve them. Victims of sexual misconduct feared reprisal, lacked access to proper support services, and experienced poor investigative responses. Further, the culture of the CAF had not evolved significantly, even as more women signed up to serve; the culture of excessive drinking and toxic masculinity still promoted an environment in which female colleagues were sexually harassed and abused as part of bets, rituals and the assertion of power.

Responding to public pressure, the government appointed Justice Deschamps to conduct an external review into sexual misconduct in the CAFEndnote 82.

Justice Deschamps was mandated to consider and make recommendations concerning the definition of “sexual misconduct”; the adequacy of CAF policies, procedures, programs and training around sexual misconduct and harassment; resources dedicated to the implementation of said policies, procedures and programs; rates of reporting and reasons why reporting may not occur; and any other matter relevant to the prevention of sexual misconduct and harassmentEndnote 83. However, her mandate prohibited her from addressing any matter relating to the military or criminal justice system. This denied Justice Deschamps the ability to address two fundamental pillars of sexual misconduct: how it is investigated and how perpetrators are punished.

During her review, Justice Deschamps consulted with over 700 individuals at various military bases and heard numerous accounts of sexual misconduct in the CAFEndnote 84. She also visited the military colleges, where participants reported sexual harassment as being a “passage obligé” and that sexual assault was an ever-present riskEndnote 85.

The Deschamps Report and initial steps taken by the CAF

On 27 March 2015, the Deschamps Report was published and confirmed many of the conclusions drawn in both the 1998 and 2014 media articles. In particular, Justice Deschamps found that there was a sexualized culture in the CAF, particularly among recruits and NCMs, “characterized by the frequent use of swear words and highly degrading expressions that reference women’s bodies, sexual jokes, innuendos, discriminatory comments about the abilities of women, and unwelcome sexual touchingEndnote 86.”

Justice Deschamps also found that certain cultural behaviours and expectations within the CAF were directly related to the prevalence of inappropriate sexual conductEndnote 87. While the CAF as an organization has established codes of conduct, she found there was “a significant disjunction between the aspiration of the CAF to embody a professional military ethos which embraces the principle of respect for the dignity of all persons, and the reality experienced by many CAF members day-to-dayEndnote 88.” Although Justice Deschamps heard fewer reports of sexual assault, she noted, “it was clear that the occurrence of sexual harassment and sexual assault are integrally related, and that to some extent both are rooted in cultural norms that permit a degree of discriminatory and harassing conduct within the organizationEndnote 89.”

She concluded that there was chronic underreporting of sexual misconduct and harassment, attributable to fears of reprisal, removal from one’s unit, concern about not being believed, stigmatization as being weak or a troublemaker, and a lack of confidentiality. Finally, she highlighted that the emphasis on low-level resolution stifled complaints, intimidated victims, or resulted in meaningless sanctions – the proverbial “slap on the wristEndnote 90.” None of this encouraged victims to come forward nor dissuaded perpetrators from predatory behaviour.

The Deschamps Report provided an authoritative assessment of sexual misconduct in the CAF. She provided 10 recommendations to address the problem.

In July 2015, General Vance was appointed as CDS. In his inaugural speech he stated: “Any harmful sexual behaviour undermines who we are, is a threat to morale, is a threat to operational readiness, and is a threat to this institutionEndnote 91.” He launched Operation HONOUR with the mission to “eliminate harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour within the CAFEndnote 92.”

From the outside, there was a perception that senior leadership was finally taking the problem of sexual misconduct seriously. However, within the ranks, many victims, past and present, were considerably more sceptical about the sincerity of the leadership on that issue. That scepticism was validated when Operation HONOUR quickly became referred to as “Hop on her.”

In April 2016, the CAF started to collect statistics on sexual misconduct reporting and responses. According to the CAF’s Second Progress Report, from April through July 2016, 148 incidents were investigatedEndnote 93. Ninety seven of these were still under investigation at the time of the report. Of the 51 investigated, 19 resulted in administrative action in the form of remedial measures, and seven led to laying of chargesEndnote 94.

The 2016 Statistics Canada Report and next steps by the CAF

To gain a fuller understanding of the issue, in 2016, the CAF asked Statistics Canada to conduct a survey on sexual misconduct. The survey received over 43,000 responses from active members of the CAF. The results of the survey indicated that 27.3% of women and 3.8% of men reported having been victims of sexual assault at least once since joining the CAFEndnote 95. Half of the female respondents identified the perpetrator as a superior. In contrast, for men, it was more likely to be a peerEndnote 96. Further, the likelihood of sexual assault was highest among younger female CAF members who were five times more likely to be sexually assaulted than their male counterpartsEndnote 97.

The results of the survey also revealed that 79% of CAF members saw, heard or were the victims of sexualized behaviour, including sexual jokes and discriminatory behaviour. Women were twice as likely as men to be the target, with 31% of women identified as the victim versus 15% of menEndnote 98.

Despite the startling prevalence of sexual misconduct, it was apparent from the survey results that CAF members still had significant trust in the system, with 81% of survey respondents believing that the organization, or at the very least their unit, would take complaints of inappropriate sexual behaviour seriously. Moreover, 36% of men and 51% of women thought that inappropriate sexual behaviour was a problem within the CAFEndnote 99.

Unsurprisingly, the survey revealed that women were less likely to report sexual assault to someone in authority for fear of negative consequences, 35% of women versus 14% of men who were victims, or due to concerns about the complaint process, 18% of women versus 7% of menEndnote 100.

Most CAF members reported being “very aware” or “somewhat aware” of Operation HONOUR. However, 30% of respondents believed that Operation HONOUR would be ineffective or only slightly effective. The most junior officers and NCMs, the largest victim groups, were the most pessimistic about its effectivenessEndnote 101.

I understand that, shortly thereafter, new policies were released and subject matter training was developed. On the surface, victims were being encouraged to come forward, and bystanders were reminded of their obligation to do so. However, the day-to-day reality in the CAF differed significantly from the policies created in Ottawa. Stakeholders reported that after Operation HONOUR was launched, there was a significant change in attitude in their male counterparts, not to one of acceptance, awareness, or altruism but to one of fear, fury, and frustration. Stakeholders also reported that many men did not take Operation HONOUR seriously and would share their stories of being “Op Honoured.”

By April 2016, the CAF had implemented a monthly tracking system to track incidents of harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour (HISB), and assist with analyzing the progress of Operation HONOUREndnote 102. This included monthly reporting on HISB at the unit level. Between April 2016 and March 2017, 504 incidents of HISB were reported at the unit level, of which 47 were sexual assaultsEndnote 103. By far, the largest category, with 281 reports, was “inappropriate sexual behaviour,” covering frequent sexual language or jokes, displaying pornography, pressuring for sexual activity, taking photos during sex without consent, and “other.” Women filed 75.8% of the reports during this period, and 180 incidents resulted in administrative action being taken by the chain of command.

On the other hand, within the military justice system and during that same time period, 288 offences were reported, of which 235 were sexual assaultsEndnote 104. While 267 were ultimately declared “founded,” only 64 charges had been laidEndnote 105.

Class actions

In 2016 and 2017, seven former CAF members initiated class action lawsuits against the Government of Canada. The plaintiffs of these class action lawsuits alleged sexual harassment, sexual assault, or discrimination based on sex, gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in connection with their military service and/or employment with the DND and/or Staff of the Non-Public FundsEndnote 106. The Government of Canada agreed to a $900 million settlement for the Heyder and Beattie class actionsEndnote 107. I return to the Heyder and Beattie class actions below, in the section on Data.

The 2018 Statistics Canada reports

In May 2018, Statistics Canada published reports on both the Reg F and P Res of the CAF. The Reg F survey was a follow-up to the 2016 survey and found that there was no significant statistical change from the prevalence of sexual assault Endnote 108. However, there was a change in demographics, with young NCMs making up a larger proportion of victims, while senior NCMs and white able-bodied women reported a decline in the prevalence of sexual assaultEndnote 109.

On the perpetrator side, women reported fewer assaults committed by superiors than in 2016 with 38% of sexual assaults carried out by a superior or higher ranked individualEndnote 110. There could be a number of factors, other than an absolute reduction in assaults, to explain this decrease. The survey did not include members who had left the CAF for any reason, potentially not capturing victims who released because of the assaultEndnote 111. Further, women may not have reported an assault by a superior even on a survey for fear of reprisal. This, the survey noted, posed a significant barrier to reporting any type of sexual assault, with 37% of all women citing it as a reason to not reportEndnote 112.

When it came to sexualized and discriminatory behaviours, there was some evidence that Operation HONOUR was working. According to the survey, the number of CAF members who witnessed or experienced sexualized or discriminatory behaviours decreased, from 80% in 2016 to 70% in 2018Endnote 113. Reporting of sexualized and discriminatory behaviour increased slightly, from 26% in 2016 to 28% in 2018Endnote 114.

In the P Res, the results were largely the same as in the Reg F. Overall, 2.2% of reservists were victims of sexual assault in 2018Endnote 115. Among the victims, one in six used CAF support services and one in 10 used civilian support servicesEndnote 116. When it came to sexualized and discriminatory behaviours, the P Res saw a decline from 82% in 2016 to 71% in 2018, which was almost identical to the Reg F, which went from 80% in 2016 to 70% in 2018Endnote 117. Women were more likely than men to witness or experience such behavioursEndnote 118, and found the behaviours offensiveEndnote 119.

The 2018 OAG Report

In September 2018, the OAG conducted an audit of the CAF on its implementation of Justice Deschamps’ recommendations and its efforts to address sexual misconduct. It made the following findings, among others:

- 5.17 We found that Operation HONOUR increased awareness of inappropriate sexual behaviour within the Canadian Armed Forces. However, the Operation had a fragmented approach to victim support as well as unintended consequences that slowed its progress and left some members wondering if it would achieve the expectations set for it.

- 5.18 We found that, after the implementation of the Operation, the number of reported complaints increased from about 40 in 2015 to about 300 in 2017. The Forces believed that the increase was an indication that members trusted that the organization would effectively respond to inappropriate sexual behaviour.

- 5.19 However, we found that some members still did not feel safe and supported. For example, the duty to report all incidents of inappropriate sexual behaviour increased the number of cases reported by a third party, even if the victim was not ready to come forward at that time. Moreover, the Military Police had to conduct an initial investigation of all reports, regardless of a victim’s preference to resolve the issue informally. This discouraged some victims from coming forward. Many victims also did not understand or have confidence in the complaint systems.

- 5.20 Information gathered by Statistics Canada during a 2016 survey indicated that there were many unreported incidents of inappropriate sexual behaviour in the Canadian Armed Forces. In mid-2018, the Forces acknowledged that inappropriate sexual behaviour remained a serious problem and that a significant focus on victim support and the use of external, independent advice were requiredEndnote 120.

Surveys of the military colleges

In 2019, Statistics Canada focused on the military colleges, replicating its earlier surveys on the Reg F and P ResEndnote 121. The primary point of comparison in the survey was the non-military civilian student population. It found that 28% of female students at a military college experienced some form of sexual assault as opposed to 15% of women in the general student populationEndnote 122. One in seven women at a military college had been sexually assaulted in the past 12 monthsEndnote 123. When it came to unwanted sexualized behaviour, the survey found that 68% of students witnessed or experienced such behaviour, which was in line with the proportion in the broader CAF in 2018Endnote 124. Most unwanted behaviours occurred when others were present and were generally committed by fellow studentsEndnote 125.

Overall, most students were aware of the procedures for dealing with sexual assault and harassment (85% of men and 70% of women), but women students and those who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours held more negative attitudes regarding school-related support and servicesEndnote 126.

Conclusion

The Deschamps Report as well as the work of Statistics Canada, exposed the prevalence of sexual misconduct in the CAF. What could have been dismissed as a series of isolated, anecdotal incidents is now recognized as a deeply-rooted organizational problem that requires a real culture change throughout the CAF. These studies have enabled academics and subject matter experts to provide input and improve collective knowledge on the subject, and it has provided a solid foundation for the Defence Team to take the steps necessary to recognize and acknowledge the magnitude of the problem.

History of Operation HONOUR

Before the Deschamps Report was released, the CAF stood up the CSRT-SM under the authority of the CDSEndnote 127. The CSRT-SM “was tasked to serve as the focal point for the development and implementation of a comprehensive strategy and associated action plan to address the recommendations of [Justice Deschamps] in order to modify and improve behaviour throughout the [CAF]Endnote 128.”

In August 2015, in response to the Deschamps Report, then CDS Vance officially launched Operation HONOUR with a mission to “eliminate harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour” within the CAF. Operation HONOUR’s preliminary aims were: to understand harmful behaviour; respond to harmful behaviour through cultural change; support victims (including establishing the SMRC) and prevent HISB through a unified policy approachEndnote 129.

Initially, Operation HONOUR was divided into four phases:

- Phase One, Initiation: Complete a comprehensive strategy and action plan and set up the SMRC;

- Phase Two, Preparation: Roll out discipline, leadership doctrine, orders and policies throughout the chain of command; the CSRT-SM begins operations;

- Phase Three, Deployment: Deliver, train, and transition the SMRC to full operational capability; and

- Phase Four, Maintain and Hold: Reabsorb the CSRT-SM while commanders continue to “personally oversee the maintenance of values and the application of administrative and/or disciplinary measuresEndnote 130.”

Preparatory steps and Phase One, Initiation

In June 2015, the CSRT-SM focused on setting up the new centre for accountability for sexual assault and harassment based on the recommendation made by Justice Deschamps.

As part of its approach to understanding the problem, during Phase One, the CSRT-SM conducted a series of domestic and international visits to learn from allied militaries and civilian organizations. In particular, it visited the relevant military authorities in the USA, Australia, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden, and various Canadian police forces, crisis response centres, and victim support institutionsEndnote 131.

Building on the work of the CSRT-SM over the summer, the SMRC became operational on 15 September 2015Endnote 132. It was independent from the chain of commandEndnote 133, while supporting both victims and the chain of command. The intention was that victim support services would ramp up with each successive phase of Operation HONOUR, and the SMRC would reach its “final operational capability” in 2018.

Following the launch of the SMRC, the first phase of Operation HONOUR was declared officially complete as of 30 September 2015Endnote 134.

Phase Two, Preparation

In the second phase of Operation HONOUR, the CAF focused on increasing awareness and implementing Operation HONOUR activities among L1 organizations. This included encouraging participation in training and Operation HONOUR-related initiatives. All L1 commanders were required to provide periodic reports on all Operation HONOUR‑related activities undertaken by their organizations and all incidents of HISB within their organizations. Further, certain L1 organizations were given additional responsibilities relating to the implementation of Operation HONOUR. For example, the VCDS was tasked with supporting and coordinating an integrated approach to developing the mandate, governance and operational model of the SMRC, providing resources to the CSRT-SM, and working with the JAG and the CFPM to develop victim reporting protocols. The CMP was ordered to assume responsibility for the CSRT-SM and tasked with identifying future resource requirements, training development, facilitating chaplain support, and developing common terminology and definitions. The JAG was asked to review the military justice system from an Operation HONOUR perspective, alongside the CFPMEndnote 135.

In the spring of 2016, the CAF claimed it had started collecting statistics on sexual misconduct reporting and responsesEndnote 136. Before Operation HONOUR, no dedicated central database to track incidents of sexual misconduct existed. However, in April 2016, the CDS ordered that all “Level 1 organizations report incidents of sexual misconduct to the [CSRT-SM]Endnote 137.” In addition, the CAF asked Statistics Canada to conduct a survey on sexual misconductEndnote 138. Aside from statistics, the CAF updated its harassment prevention policy, the Defence Administration Order and Directive (DAOD) 5012-0Endnote 139, and the JAG committed to ensuring that his comprehensive review of the court martial system would include Operation HONOUREndnote 140.

Phase Three, Deployment

Phase Three commenced on 1 July 2016Endnote 141. According to the CAF, the SMRC’s operating hours had increased, and additional training had been provided to military health care professionals. The CFPM had introduced new training on data collection and victim interviewing techniques for the MPEndnote 142. The MP also added 18 positions to the CFNIS to create a “Sexual Offences Response Team” with three members in each regional office for additional support to complex filesEndnote 143.

By August 2016, the CMP was charged with overseeing the coordination of Operation HONOUR, supported by the Director General of the CSRT-SM. However, the CDS remained responsible for the overall execution of Operation HONOUR, and accountable for its successEndnote 144.

The CAF determined that two entities were necessary to achieve institutional culture change: a strategic-level steering committee, mandated to provide direction and harmonize the overall response to sexual misconduct in the CAF, and an advisory council with external subject matter experts to develop victim support services, training, education, and policyEndnote 145.

To evaluate the success of Operation HONOUR’s implementation, the CAF planned to conduct internal and external research and update its “Unit Climate SurveysEndnote 146.”

Phase Three saw the continuation of many tasks started in Phase Two, but with a shift “from developing awareness and understanding the problem to implementing a comprehensive training, education and prevention approach across the CAFEndnote 147.” The dissemination of training and educational materials began shifting down the chain of command. Commanders were directed to ensure that instructors were appropriately trained and that all personnel in supervisory roles were provided information about available trainingEndnote 148.

In addition to other Operation HONOUR-related tasks, the VCDS was responsible for supporting the CFPM and the CSRT-SM in creating victim support mechanisms, and facilitating the alignment of the new ICCM program with the SMRC and the CSRT-SM initiativesEndnote 149. Although the initiating directive for the ICCM was first issued in 2014Endnote 150, full implementation of the ICCM was only scheduled for 2019Endnote 151. The CMP also gained additional responsibilities, including coordinating efforts between the CSRT-SM and the SMRC regarding a new national subject-matter expert group on sexual harassment within the SMRC, developing a Victim Assistance Program, and developing a national peer support program under the supervision of the Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services (CFMWS)Endnote 152.

November 2016 saw the publication of the results of the first Statistics Canada surveyEndnote 153. The survey’s results were alarming, with a majority having witnessed sexualized behaviour, and 27.3% of women and 3.8% of men reported being a victim of sexual assault since joining the CAFEndnote 154.

In April 2017, the Third Progress Report on Operation HONOUR was released. It again claimed a number of achievements during the reporting period. The CFHSG, the CFPM, the DMP, the CFMWS, and the Chaplain General had all instituted new victim support initiatives. The SMRC was poised to roll out 24/7 access to support services. Plans were in the works for a peer support network, a Victim Assistance Program to help victims better navigate the system. Also planned was the introduction of a “third option reporting” which would safeguard crucial evidence without pressuring a victim to first press chargesEndnote 155. However, I was not provided with any documents to show that this reporting option was ever implemented.

The report also noted that the JAG and Department of Justice were drafting regulations to implement the victims’ rights provisions of Bill C-15Endnote 156. Although certain provisions of Bill C-15 came into force in 2013, the victims’ rights elements had still not been implemented four years later. In particular, Bill C-15 sought to “provide victims of service offences with specific procedural rights, such as their right to make victim impact statementsEndnote 157.”

The SMRC introduced a modified case management system and the CAF implemented the HISB tracking and analysis system to track the occurrence of sexual misconduct. A variety of training programs were also rolled out during this period, including unit-level training on addressing sexual misconduct, bystander intervention training, and a “Respect in the CAF” (RitCAF) workshop. A RitCAF mobile app was in development and meant to roll out on 17 June 2017Endnote 158.

On 24 July 2017, the SMRC launched a “one-year pilot of 24/7 service delivery [...] to ensure that all CAF members would have access to support on a 24/7 basis, whether deployed internationally or domesticallyEndnote 159.” According to the 2017-18 SMRC Annual Report, in the fall of 2017, the Your Say survey was sent out to 9,000 Reg F and P Res members; the SMRC also launched new web content that was audience-orientedEndnote 160.

In January 2018, the Operation HONOUR Tracking and Analysis System (OPHTAS) was “created for use by the chain of command as a dedicated means of recording, tracking and conducting trend analysis of incidents of sexual misconductEndnote 161.” At the same time, the JAG also brought an end to the internal Court Martial Comprehensive Review, which was supposed to examine courts martial from an Operation HONOUR perspective, and downgraded the draft report to a discussion paperEndnote 162.

In 2018, the External Advisory Council (EAC) on sexual misconduct was established namely to “provide advice and recommendations to the DM and the CDS on Operation HONOUR activities,” including the implementation of Justice Deschamps’ recommendationsEndnote 163.

The institutionalization of Operation HONOUR

On 5 March 2018, Operation HONOUR was changed from a limited operation to a permanent institutional initiative and the previous four-phase approach was abandoned. The CSRT-SM was moved back to the VCDS and placed on a permanent footing that would eventually become the DPMC-OpH. The new objective was to establish an institutional framework across the CAF to effect culture change and measure performanceEndnote 164.

In March 2018, the SMRC also “refined the training framework to specify the mandatory training that Counsellors and Senior Counsellors must complete to become and remain proficientEndnote 165.”

In the fall of 2018, the OAG released a report that focused on whether the CAF “adequately responded to inappropriate sexual behaviour through actions to respond to and support victims and to understand and prevent such behaviour.Endnote 166” The OAG found that, despite Operation HONOUR being in its third year, several of the problems identified by the Deschamps Report remained. In particular, victim support services were patchy, difficult to access, and under-resourced; the duty to report presented a barrier to reporting; education and training around inappropriate sexual behavior failed to address the root causes of such behavior; and there was inadequate monitoring of the CAF’s effortsEndnote 167.

In February 2019, a Fourth Progress Report was released. It was considerably more subdued than the previous progress reports. The report did, however, note various actions taken over the preceding 21 months. For example, the OPHTAS reached its initial operating capability on 1 October 2018. The CAF also claimed it had improved response to complaints through the ICCM, introduced a more victim-centred approach to investigations and prosecutions, improved research around sexual misconduct in the CAF, and benefited from external collaboration through the EACEndnote 168.

However, the Fourth Progress Report acknowledged that a comprehensive strategy of culture change had yet to be developed. It considered the following to be areas in which the CAF’s response to sexual misconduct was “significantly less successful”:

- Delayed development and implementation of a unified updated policy on sexual misconduct;

- Failure to produce strategic direction and a campaign plan to guide the necessary culture shift;

- Absence of a plan against which to assess performance, creating an emphasis on statistics on performance measures;

- Establishment of an optimal governance structure between the SMRC and the CAF, which protects the independence of the SMRC while allowing enough integration to meet the institutional needs of the CAF;

- Implementation of a consolidated CAF-wide tracking capability to provide a comprehensive institutional picture of sexual misconduct in the CAF;

- Effective strategic communications with CAF members to avoid subject matter fatigue and ensure the continued relevance of Operation HONOUR;

- Sufficient interaction with external entities and stakeholders; and

- Capturing the experiences and lessons learned during the implementation of Operation HONOUREndnote 169.

The terms of reference for the Operation HONOUR Steering Committee were issued on 28 June 2019, some two-and-a-half years after this part of the governance structure was first identified as a requirementEndnote 170. They directed the Steering Committee to “provide a forum for the chain of command to inform, provide input, and discuss Operation HONOUR and the CSRT-SM’s efforts to meet the CDS’ intent from the immediate requirements through to the long term goalsEndnote 171.” The Steering Committee met semi-annually to ensure “CAF‑wide situational awareness, information sharing, and leadership, focused on the elimination of sexual misconduct from the CAFEndnote 172.” Members of the Steering Committee included L1 deputy commanders, select chief warrant officers/chief petty officers 1st class, the Executive Director of the SMRC, the Surgeon General, the DND/CF Legal Advisor, the CFPM, the Chaplain General, the DGICCM, the DGMPRA, and the JAG. The Steering Committee was overseen by and accountable to the VCDSEndnote 173.

In May 2019, Statistics Canada released the results of its 2018 survey on sexual misconduct in the CAFEndnote 174. Following this, the SMRC’s mandate was expanded beyond the provision of support to CAF members, to include provision of expert advice and guidance to the CAF, and monitoring of the CAF’s progressEndnote 175. Further, it was noted that despite significant attention given to Operation HONOUR in Ottawa, “low awareness of the resources continues to be a problem. Finding strategies to simplify the content and improv[e] its intelligibility should be a priority. Working with different communities within the CAF through a [Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+)] lens would be helpful to identify the best information dissemination strategies for each of themEndnote 176.”

In July 2019, the CSRT-SM was renamed the DPMC-OpH. As noted below, this name change was in response to criticism that CSRT-SM was too similar in name to SMRC and was causing confusion. New mandates were issued for the DPMC-OpH and the SMRC. On 15 July 2019, the operating agreement between the SMRC and the DPMC-OpH was approved by the VCDSEndnote 177.

According to its mandate, the DPMC-OpH was “the strategic level planning and coordination staff leading the [CAF]’s institutional change efforts to address sexual misconduct and promote a focus on the dignity and respect of the individualEndnote 178.” Its responsibilities included developing policy and direction, implementing expert guidance from the SMRC, including training, and monitoring the application of policy, administration and training regarding sexual misconductEndnote 179.

At the same time as the DPMC-OpH’s new mandate was issued, the interim version of the Operation HONOUR Manual was released. This version was developed in cooperation with the SMRC in consultation with the EAC, and issued on the authority of the CDS. It provided an overview of Operation HONOUR, its governance and key training packages and initiatives. It also introduced readers to critical concepts and definitions of sexual misconduct, sexual harassment, and victim-blaming. It provided information about support services, tools and resources and an overview of prevention measures and guides for reporting and responding to incidents of sexual misconductEndnote 180.

Further, on 25 July 2019, the CAF issued a direction that permitted commanding officers to “provide victims with information about the outcomes and conclusions of administrative reviews related to their complaint, as well as administrative actions imposed by the chain of command on the person who caused them harmEndnote 181.” This directive sought to close “a critical information gap identified by complainants in cases of sexual misconduct and victim advocates” while complying with the Privacy ActEndnote 182.

In August 2019, the CAF released its first report based on statistics collected from tracking tools such as the OPHTAS during Operation HONOUR. The CAF noted that “work is underway to fully integrate [the] OPHTAS with all other key personnel-related and sexual misconduct incident-related databases,” including select MP data, the Justice Administration and Information Management System (JAIMS) for military justice outcomes, and the Integrated Complaint Registration and Tracking System (ICRTS) for sexual harassment outcomesEndnote 183. In September 2019, the CDS issued a directive to institutionalize and improve the OPHTASEndnote 184.

At the same time that the CAF released its first Sexual Misconduct Incident Tracking Report, the Operation HONOUR Steering Committee met and discussed changing the Operation HONOUR communications strategy. It was noted that the media, in particular, had a hard time distinguishing between CAF programs and “there was […] never any over-arching goal in the messagingEndnote 185.” As a result, the Steering Committee produced a “strategic narrative” to provide essential information on sexual misconduct in the CAFEndnote 186.

In December 2019, the Operation HONOUR Manual was updated, and the CDS issued a final version in January 2020Endnote 187. However, despite this advancement, many of the initial problems highlighted by Justice Deschamps still existed. For example, “despite the CAF claiming to have achieved progress on many of Deschamps’ recommendations, victims and survivors continue to report dissatisfaction with the process, and service members in general have been exhibiting signs of fatigue, even resistance, when it comes to Operation HONOUREndnote 188.”

In 2020, the CAF released the Path to DignityEndnote 189, intended to be the CAF’s long-term campaign and strategy to bring about cultural change and address sexual misconduct permanently. The strategy consisted of four elements:

- Part 1: Strategic Approach to Cultural Alignment, intended to identify the elements that constitute and influence CAF culture and provide a cultural alignment model that can be applied to a broad range of issues;

- Part 2: Strategic Framework to Address Sexual Misconduct in the CAF. It applies the model in Part 1 and sets out the objectives and desired outcomes of the strategy;

- Part 3: Operation HONOUR Strategic Campaign Plan 2025 sets out a five-year plan for implementation; and

- Part 4: Operation HONOUR Performance Measurement Framework is a system for monitoring the progress of Operation HONOUR over time.

With the creation of the DPMC-OpH and other governance structures, the intention of the strategy appeared to be to embed Operation HONOUR for the long term. Even the EAC noted the evolution of Operation HONOUR from an “incident based, transactional approach to longer-term holistic view towards changing the CAF culture. The key message for The Path is that Op[eration] HONOUR is never going away; it is a steady state, there is no end stateEndnote 190.”

The end of Operation HONOUR

However, Operation HONOUR did not survive the new reporting on sexual misconduct that arose in 2021. As Justice Fish summarized:

- The third period of the CAF’s struggle with sexual misconduct since 1998 began on February 2, 2021, when Global News reported allegations of inappropriate behaviour between a retired CDS and two female subordinates. Three weeks later, another CDS stepped aside after several news outlets had contacted the DND to confirm that he was the subject of a sexual misconduct investigation. And on March 31, 2021, the Chief of Military Personnel stepped aside as well, this time amid allegations of sexual assault on a subordinate female memberEndnote 191.

On 24 March 2021, then Lieutenant-General Eyre, Acting CDS, announced the end to Operation HONOUR. In his words:

- Operation HONOUR has culminated, and thus we will close it out, harvest what has worked, learn from what hasn’t, and develop a deliberate plan to go forward. We will better align the organizations and processes focused on culture change to achieve better effectEndnote 192.

Lieutenant-General Eyre stated that he remained committed to learning from the exercise and improving the processes, and in his letter to CAF members, he pledged to:

- identify and take the steps necessary to create a workplace where individuals feel safe to come forward when they experience sexual misconduct;

- finalize and publish our Code of Professional Military Conduct, including a new focus on power dynamics in our system;

- add new rigour and science to leader selection, starting at the highest levels;

- implement the Restorative Engagement aspect of the Final Settlement Agreement of the Heyder and Beattie class actions; and

- improve mechanisms to listen and learn from the experiences of those who have been harmed.

Having heard from numerous stakeholders, the scepticism that marked Operation HONOUR is not surprising. The documentary record shows a top-down, Ottawa-led process marked by sporadic flurries of activity and long periods of apparent inaction. I heard numerous stories of cancelled, poorly attended, poorly implemented, or poorly taught training. Many initiatives lacked resources. I heard accounts of Operation HONOUR fatigue and how “Operation HONOUR” quickly became “Hop on Her” and was not taken seriously by large parts of the organization.

Some of this is confirmed by the CAF’s internal documents, but mostly the flaws in Operation HONOUR were exposed by external reports such as the Statistics Canada surveys and the AG’s report. In particular, I am struck by the change in tone between the early progress reports and the Fourth Progress Report. This report followed the 2018 OAG Report, which criticized the CAF’s implementation of the Deschamps Report over the preceding three years. Until that point, there seems to have been an assumption by the CAF that Operation HONOUR was being effectively implemented only because Ottawa mandated it. The CAF’s internal audit processes do not appear to have been focused on this issue, or if they were, their reports went unread.

Rather than focus on the clear recommendations of the Deschamps Report, the CAF leadership developed a plan with no measurable key performance indicators – oblivious to its own limitations as it attempted to manage and transform issues on which it had no expertise.

Chief Professional Conduct and Culture

At the end of March 2021, then Lieutenant-General Eyre, Acting CDS, announced that the CAF would welcome an external review of the institution and its culture. As set out above, he also announced the closeout of Operation HONOUR and indicated that a plan was underway to develop a “deliberate” approach to culture in the futureEndnote 193.

The DND and the CAF subsequently released a directive on culture concluding that change could not be achieved by merely establishing a named operation, and announced instead the immediate stand up of the CPCC as part of National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ), to “develop a detailed plan to align Defence culture and professional conduct with the core values and ethical principles we aspire to uphold as a National InstitutionEndnote 194.”

The CPCC’s aim is to become the single functional authority on aligning defence culture with the standards expected of the profession of arms and the Defence TeamEndnote 195. It is to become the principal advisor to the DM and the CDS for all matters related to professional conduct and culture, including sexual misconduct and hateful conduct.

I learned of the existence of the CPCC on the same day as my appointment to conduct this Review was announced. I was not made aware until then that the CPCC – the new functional authority for culture change, including in relation to sexual misconduct – was in the process of being stood up. This is symptomatic of a broader issue. For example, while little was done to implement some relatively straightforward recommendations made in the Deschamps Report, big initiatives were launched that may have benefited from a more considered, comprehensive and unified approach. The parallel launch of the CPCC and this Review has likely created some duplication of effort, such as consultations on bases and wings and other inefficiencies.

This is not a comment on the CPCC’s mandate or staffing. The CPCC and the VCDS have been in communication with me and readily accessible throughout my Review. I have benefited from their insight and work and appreciate their efforts.

Generally, the CPCC has focused its effort on four main areas: supports for survivors, justice and accountability, culture change and consultation and communicationEndnote 196. The CPCC describes these four “pathways to progress” as its action plan to “capture and consolidate some of the key efforts planned or underway” to address harm to members of the Defence Team. I have received updates on these pathways over the course of my Review which are generally consistent with the “change progress tracker” that the CPCC has made available online to publish its current and future plans for changeEndnote 197.

Each of the “pathways to progress” is addressed in the CPCC’s work. For instance, with respect to “supports for survivors,” the CPCC is working with the SMRC to expand the SMRC’s services to DND employees and former CAF members and is working to increase the SMRC’s regional footprint. The CPCC is also supporting the SMRC in its launch of the Restorative Engagement Program required under the final settlement of the Heyder and Beattie class actions, and is establishing a joint veteran and DND peer support programEndnote 198.

Further to “justice and accountability,” the CPCC has reviewed the complaints management process to better understand the existing complaints framework. With respect to “culture change,” the CPCC has taken on several initiatives, including the review of culture and professional conduct training delivered by the CFLRS.

The CPCC has also, further to its consultation mandate, been engaged in a multi-month consultation tour of the CAF, holding town hall presentations and focus group discussions. At each stop, in-person and virtual, the command team for the CPCC engaged in a discussion of organization’s culture problem, how to define success in addressing this problem, what could be done better, and the strategy to improveEndnote 199.

I understand that the CPCC comprises four Directorates: Policy, Engagement and Research; Culture Change; Professional Conduct and Development; and Conflict Prevention and Resolution. There are currently 425 approved positions, not all filled. The ICCM program has been moved under the CPCC, as has DPMC-OpH, which is winding up Operation HONOUR. Overall, the CPCC initiative appears well-resourced and supported and is taking on a wide range of mandates relevant to this ReviewEndnote 200.

Data

I turn to the way the CAF has collected and made use of data regarding sexual misconduct in its ranks. My examination of that issue reveals, once again, a series of initiatives unconnected to the global needs of the organization, including the need to capture what it knows and maximize the usefulness of that knowledge in decision-making. Fortunately, the CAF and the DND have recently begun to take steps to address these issues.

Data analysis will be a vital component in effecting meaningful, sustainable change in the CAF and the DND. Without data, organizations are ill-equipped to make informed policy decisions and measure the impact and effectiveness of those decisions. As well, data can be especially powerful in determining the root causes of particular events and identifying risks before they become serious issues.

Background

Many organizations within the DND and the CAF already gather a significant amount of information – related to complaints, charges and cases – for their own purpose. But the information is disjointed and misses links to other parts of the Defence Team.

Ideally, a more thoughtful approach would ensure that the sum of each organization’s data represents the whole picture of sexual misconduct in the DND and the CAF. With the current silo model focused on achieving individual organizational mandates, this is simply not possible.

The following table provides examples of sexual misconduct incidents and related actions reported to, and recorded by, various organizations within the DND and the CAF.

Table 1. Number of sexual misconduct incidents and related actionsEndnote 201.

Organization |

Description of what is collected |

2020–21 |

2019–20 |

2018–19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

CCPC, DGPMCEndnote 202 |

Number of incidents reported to the chain of command and recorded in the OPHTAS, renamed the Sexual Misconduct Incident Tracking System (SMITS). |

444 (Not published) |

497 (Not published) |

344 (Not published) |

| SMRCEndnote 203 | Number of new cases opened by SMRC. |

654 |

649 |

484 |

DMCAEndnote 204 |

Releases due to inappropriate sexual behaviour. |

25 |

36 |

33 |

| JAGEndnote 205 | Court martials related to sexual misconduct. |

Not yet tabled |

25 |

20 |

Table 2. Number of sexual misconduct incidents and related actionsEndnote 206.

Organization |

Description of what is collected |

2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

CFPMEndnote 207 |

Number of sexual related incidents by calendar year. |

234 |

334 |

358 |

DMCAEndnote 208 |

Victims released via Medical Employment Limitation due to inappropriate sexual behavior (number of MELs opened in the year/number of releases in the year). |

36/13 |

34/1 |

14/0 |

ICCMEndnote 209 |

Number of sexual harassment complaints by year recorded in ICRTS. The 2018 data is as of July 2018. |

8 |

13 |

3 |

Statistics CanadaEndnote 210 (External to the CAF and the DND) |

Number of Reg F members who stated that they were victims of sexual assault in the military workplace or involving military members. |

n/a |

n/a |

900 |

One question that bears asking is what is actually happening in a given year. For example, a member’s release may not be for incidents perpetrated in that year, in the same way that reporting date and date of incident cannot be assumed to coincide. Without question, there is a missed opportunity here. If the CAF and the DND make a concerted effort to coordinate data findings among their various organizations, a detailed analysis could produce useful insights.

I am not the only one to have noticed these data weaknesses. Over the last seven years, a number of people have observed and expressed concern about these issues. They include:

- Justice Deschamps – 2015;

- the AG – 2018;

- the Senate Standing Committee on National Security and Defence – 2019;

- Executive Director of the SMRC – 2020;

- the ADM(RS) – 2021; and

- the Public Service Alliance – 2022.

Coordination

Clearly, CAF leadership is well aware of the issues.

In 2019, the DND and the CAF released the DND/CAF Data Strategy, a document that sets out a vision for the DND and the CAF where “data are leveraged in all aspects of Defence programs, enhancing our defence capabilities and decision-making, and providing an information advantage during military operationsEndnote 211.” The Strategy does not specifically mention sexual misconduct data; however, it presents an opportunity to use data for sexual misconduct prevention efforts, and to focus resources, improve culture and minimize risk.

In addition, the Operation HONOUR Performance Measurement Framework outlined how progress towards cultural alignment would be measured over time. Using this framework, the CAF intended to “move beyond the short-term measurement of self-reported experience and behaviours and attempt to address the less tangible dimensions of culture that will influence and sustain desired patterns of behaviour over the longer termEndnote 212.”

In April 2021, the Initiating Directive for Professional Conduct and Culture stated that the “ability to understand the scope and seriousness of [the CAF and the DND’s] challenges is limited. Multiple databases collect and track misconduct-related information making analysis difficultEndnote 213.” Its terms directed the Assistant Deputy Minister (Data, Innovation and Analytics) (ADM(DIA)) and the Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management) (ADM(IM)) to co-lead an effort to “inventory and consolidate data assets and IT systems currently used across [the DND and the CAF] to capture and manage misconduct-related files in accordance with the Access to Information and Privacy Act and information security provisionsEndnote 214.”

In late spring of 2021, ADM(DIA) and ADM(IM) “were mandated to identify existing data assets related to systemic misconductEndnote 215.” They found that there were “31 unique data assets” across the DND and the CAF that “enable service delivery, tracking and reporting on systemic misconduct across [the DND and the CAF]Endnote 216.” The report proposes options to improve data governance, data integration and data analytics. Key findings of the data exploration efforts include:

- lack of mechanisms for integration or interoperability between data assets with unique mandates;

- low level of data quality;

- lack of overarching data governance for conduct-related data (including lack of standard definitions for types of conduct across CAF and DND approaches and policies); and

- limited automated reporting capabilitiesEndnote 217.

In August 2021, ADM(DIA) requested funding to build capacity and accelerate the collective efforts to improve conduct-related tracking, reporting and analytics. In his briefing note, he emphasized the data weaknesses:

- “Complaints, reporting, and tracking systems related to misconduct are fragmented and complex. They are made to or through multiple organizations and the associated investigations are registered and tracked across multiple disparate systems. Many of these systems were not designed for analytics and reporting and the lack of interoperability makes aggregate analysis difficult. They also face significant data challenges including a lack of data governance, data standardization, and other data quality issues resulting in system and data redundancy issues. The A/CDS and DM have identified the lack of integration and centralization of data in IT systems, as well as limited data accessibility and reporting as key issues that must be addressedEndnote 218.”

Operation HONOUR Tracking and Analysis System

When I asked how the highest-ranking CAF officers are assured that the policy and process set out in DAOD 9005-1 are implemented, the commanders who responded pointed to their use of the OPHTASEndnote 219.

For example, the OPHTAS is used not only to “ensure compliance to all reporting requirements but also ensures that [the environment] follows up on the application of [administrative]/disciplinary actions being takenEndnote 220.” Moreover, the OPHTAS is “the primary means by which the [environment] oversees sexual misconduct response and the application of DAOD 9005-1.Endnote 221” According to a presentation on the OPHTAS, “[f]or the purposes of reporting, if incidents are not in OPHTAS, they don’t existEndnote 222.”

Prior to the introduction of Operation HONOUR in 2015, the CAF did not use a dedicated central database to record all cases of sexual misconductEndnote 223. As of 1 April 2016, all L1s were directed to report sexual misconduct incidents to the CSRT-SM (changed to the DPMC‑OpH).

In January 2018, the OPHTAS was launched for use by the chain of command as a dedicated means to record, track and conduct trend analysis of incidents of sexual misconductEndnote 224. Once an incident is reported to the chain of command, the OPHTAS user has 48 hours to enter the case in OPHTASEndnote 225.

While the OPHTAS was implemented in 2018, a CDS directive to institutionalize and improve the system was issued in September 2019 because “not all L1s [were] fully aware of their responsibilities and not all CAF units [were] aware of the requirement to record and update sexual misconduct cases in OPHTASEndnote 226.”

On 24 March 2021, the Acting CDS announced the termination of Operation HONOUR. However, the CAF continues to record and track sexual misconduct incidents in the established database, now called the SMITS, and this data will continue to be published regularlyEndnote 227. There was also an attempt to extend OPHTAS to DND employees, although this was never finalizedEndnote 228. This was unfortunate, as it missed an opportunity to track sexual misconduct across the wider Defence Team.

Four Operation HONOUR annual reports have been produced to provide a summary of what the CAF has accomplished to date, including areas of success and areas where more work is required. Information reported includes number of incident reports, types of sexual misconduct, profile of who reported incidents, location/circumstance profile, disciplinary action, and administrative review. These annual reports were published prior to the launch of the OPHTAS.

The first report using the OPHTAS database was released in August 2019, in the Sexual Misconduct Incident Tracking Report. This report provides incident trends by date, sexual misconduct incident statistics, and actions taken for reported incidents. The report also claimed that “work [was] underway to fully integrate [the] OPHTAS with all other key personnel-related and sexual misconduct incident-related databases” such as “select information on Military Police investigations.” In addition, the report stated that the “OPHTAS will also be integrated with other systems, such as the Justice Administration and Information Management System (JAIMS) for military justice outcomes and the Integrated Complaint Registration and Tracking System (ICRTS) for sexual harassment outcomesEndnote 229.”

In a March 2022 technical briefing on modernizing the military justice system, the Office of the Judge Advocate General (OJAG) stated that it has been “working in partnership with ADM(IM) to modernize how cases within in [sic] the military justice system are managed and related information is gathered and maintainedEndnote 230.” The Justice Administration and Information Management Systems (JAIMS 2.0) is supposed to roll out in winter 2023. While already integrated with Guardian (the military HR system), the intent is that JAIMS 2.0 will also integrate with the DMP’s Case Management System. According to the OJAG, this integration is meant to reduce the number of times a victim will need to repeat their story.

In a January 2020 report, the SMRC pointed out that “the information contained within the [2019 Sexual Misconduct Incident Tracking Report] report demonstrates its potential as a critical tool for organizational awareness, program development, and centralized reporting.” However, it also noted that “its utility is limited by a number of factors, including compliance with and consistency in reportingEndnote 231.” To exemplify this lack of consistency, we reviewed the 13 Q2 2021 report cards that OPHTAS officials provide to L1s with a snapshot of the quality and completeness of data in the OPHTAS. On average, according to the report cards, 40% of all cases lacked critical information, with administrative and disciplinary actions representing the most incomplete data.

In addition, while the OPHTAS is intended to be a centralized database for all cases of sexual misconduct and includes comprehensive case-specific information, the system only records incidents reported by or to the chain of commandEndnote 232. As a result, “not all incidents of sexual misconduct are included, namely those that are reported to police or [the] ICCM, or disclosed to the… [SMRC] or [the CFHSG]Endnote 233.”

The 2020 Sexual Misconduct Incident Tracking Report was finalized but not released to the public. Typically, it would have been ready for publication in March 2021, but the impact of COVID-19 and an impending federal election delayed the preparation of the report.

Privacy concerns

I received data downloads from the OPHTAS system, but information was removed due to concerns about identifying individuals. Privacy proved to be a common concern and consequent deadlock during my Review. I appreciate the need to protect privacy; however, it is important to ease the tension between using data for analysis and decision-making, and privacy concerns.

In the same vein, in October 2021, the ADM(DIA) pointed out that the OPHTAS “clearly prohibits the use of its information ‘for any purpose other than sexual misconduct incident recording, tracking and updatingEndnote 234.’” Such restricted use is unfortunate as the large amount of information captured in the system provides an opportunity to analyze trends and support evidence-based decision-making. This means that “it is possible for [the] OPHTAS to leverage other data sources but not for other systems to integrate OPHTAS dataEndnote 235.” While the OPHTAS has “effectively connected to the Guardian military personnel administration systemEndnote 236” to “automatically [populate] the service number when cases are built (…), it has not been possible for [the] SMRC to gain direct access to OPHTAS data for its own reporting for legal reasons, including the Privacy Act, the Privacy Impact Assessment for [the] OPHTAS, and need-to-know requirements for accessEndnote 237.” The SMRC “has formally requested direct access to [the] OPHTAS on many occasions, without successEndnote 238.” As an alternative, the “SMRC is working with [the] CAF to receive reports to enable them to exercise their mandate to the extent possible, while continuing to pursue direct accessEndnote 239.”

The ADM(DIA) recognized the need to strike the right balance. It stated that “[i]mproving organizational situational awareness across the spectrum of conduct requires clearly defined roles and responsibilities that centre the sensitivity of the information but enable it to be harmonized effectively to support enterprise-level, strategic decision-making.” I encourage them to continue the exploration of how “making data related to professional conduct as open and accessible as possible, including to the Canadian publicEndnote 240” and researchers.

We have heard that, in addition to entering data into the OPHTAS, at least one base tracks its own sexual misconduct cases, as they believe their system is more effective. We have also heard that much time is spent adding information into the OPHTAS because new fields are introduced and/or users need to change data that has already been inputted to reflect changes in the system. This has at least two impacts – the practical problem of double data entry, and the lack of trust in the system. It also begs the question of how many other secondary databases are being maintained.

Other weaknesses that I heard during my Review are worth mentioning. First, over 250 pieces of information per incident are potentially collected in the OPHTAS. Some of this information could be useful for data analysis; however, no effort on this front appears to have been made. One example brought to my attention of how this data could be useful is the field to input a member’s obligatory service end date. This information could test the hypothesis that members are more likely to report an incident close to the time of their release.

Second, we were told that missing information in the database could be due to uncertainty/fear/resistance by members to provide the information.

Third, there is a risk that information in the database may not be reliable, as members may choose not share all information including, for example, the identity of some of the persons involved in the incident.

Fourth, it is not possible to include information about civilians, which means that repeat victims cannot be identified for risk mitigation. And offenders who leave the CAF, but enter DND employment as veterans, similarly cannot be tracked if they reoffend. The lack of a consolidated system for tracking incidents across the Defence Team is therefore problematic. In short, there are many shortcomings in the OPTHAS that must be addressed.

Overall, the work underway to collect sexual misconduct data is ambitious but by no means unachievable. There is a lot of information to be streamlined and integrated across organizations. The end reward for these efforts will be a data collection system that is invaluable to organizational knowledge and decision-making, and will represent ground-breaking change for understanding the issue of sexual misconduct in the CAF.

I can only repeat recommendations made in the past that data collection should aim at usefulness to support evidence-based decision-making and not simply as a ways of counting events or accounting for action.

Final Settlement Agreement – Heyder and Beattie class actions

The CAF and the DND have acknowledged “the harmful impact that sexual misconduct and discrimination has had on members of the Defence TeamEndnote 241.” In July 2019, the parties involved in the Heyder and Beattie class actions entered into a Final Settlement Agreement, approved by the Federal Court on 25 November 2019. As a result, the DND and the CAF will “compensate members of the Canadian military who experienced sexual misconduct.” In March 2020, class members began submitting claims to seek financial compensationEndnote 242.

As the period for filing claims expired in November 2021, the class action administrator received 19,516 claims of sexual misconduct, according to data received from the DND/CF Legal Advisor. Class action claimants reported 4,709 incidents of sexual misconduct that occurred in the decade between 2000 and 2010Endnote 243. According to Canadian Military Prosecution Service data, 106 sexual misconduct cases were brought to court martial during that timeEndnote 244. From 2010 to 2020, class action claimants reported 7,714 incidents of sexual misconductEndnote 245 and only 140 cases were brought to court martialEndnote 246.

Breaking the total number of claims down by type, 14,123 claims were made by CAF members. While current or former DND employees and Staff of the Non-Public Funds were also eligible to make a claim and receive compensation, only 847 claims were made by DND employees, and only 142 claims were made by Staff of Non-Public FundsEndnote 247.

Although several factors could explain this disparity, such as informal resolution or an incident not being severe enough to warrant a court martial, it is clear that the structure of the class action enabled victims of sexual misconduct to obtain a form of redressEndnote 248.

As part of this process, a variety of information was collected. However, in structuring the Final Settlement Agreement, confidentiality concerns seem to have prevented any effort to ensure that information collected as part of the claims could be used for research purposes – without in any way compromising privacy and confidentiality imperatives. This is incredibly unfortunate.

Had this information been gleaned, we could have achieved deeper insight into the history of sexual misconduct in the CAF up to 2019. For instance, I requested data points such as ranks of claimants and alleged perpetrators, types of allegations, and whether incidents had been previously reported. Even though it is possible to present aggregated data without compromising the identity of individuals, I was unfortunately only provided with high-level claims statistics, and was told it would not be possible to go back into the claims database to extract anything else.

Focus on the Offender

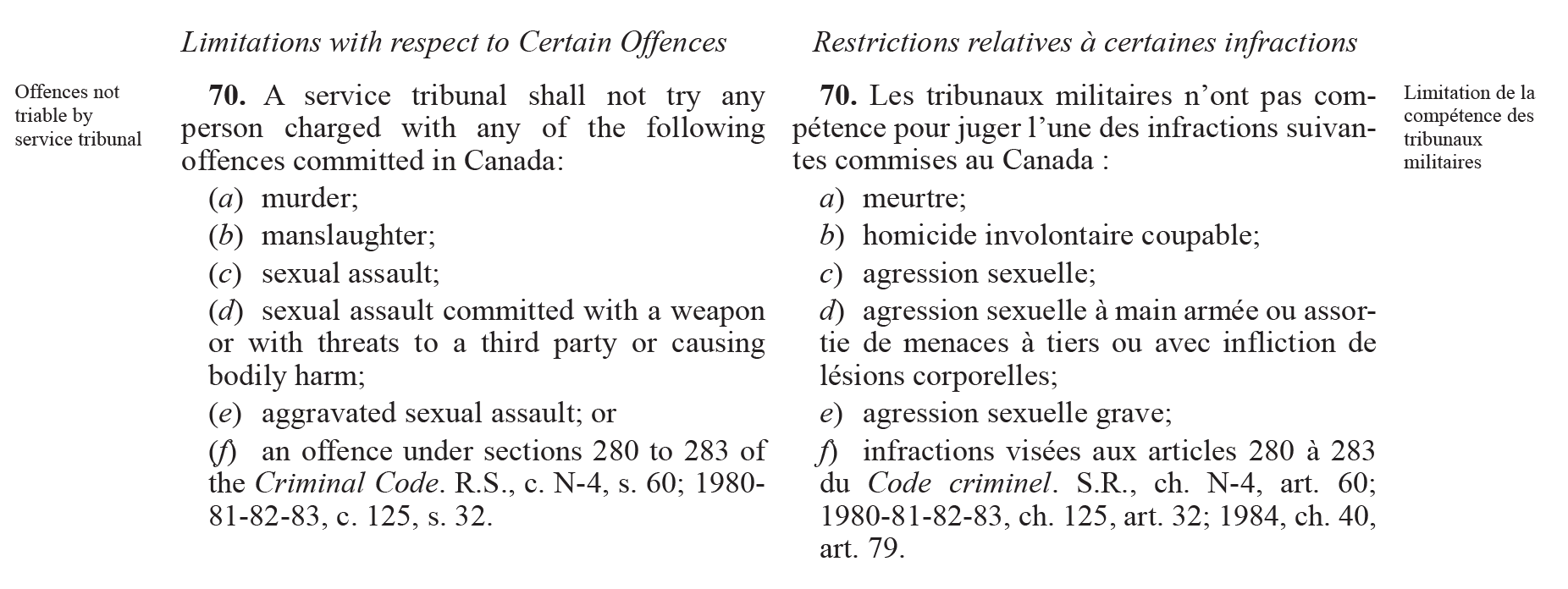

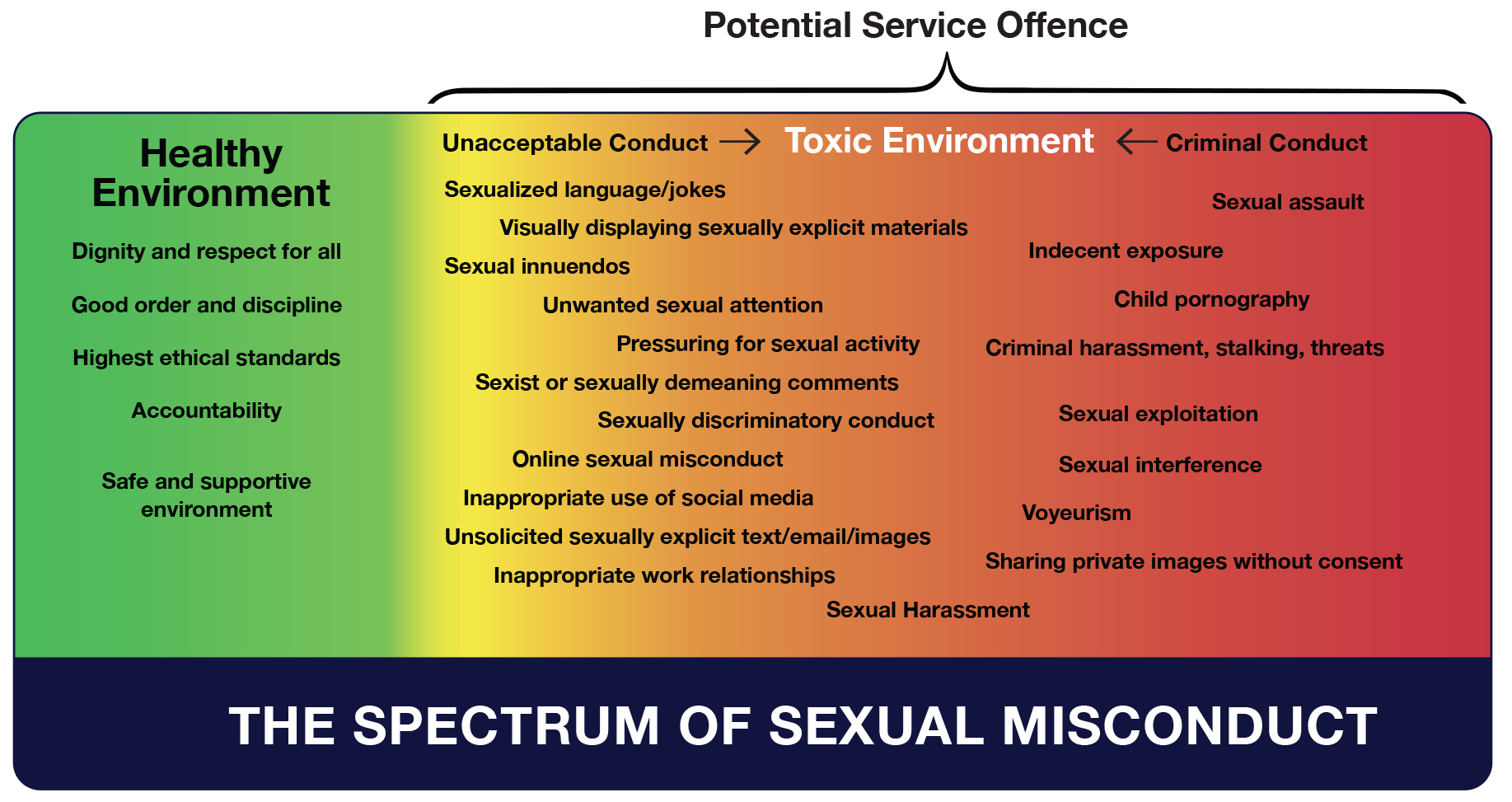

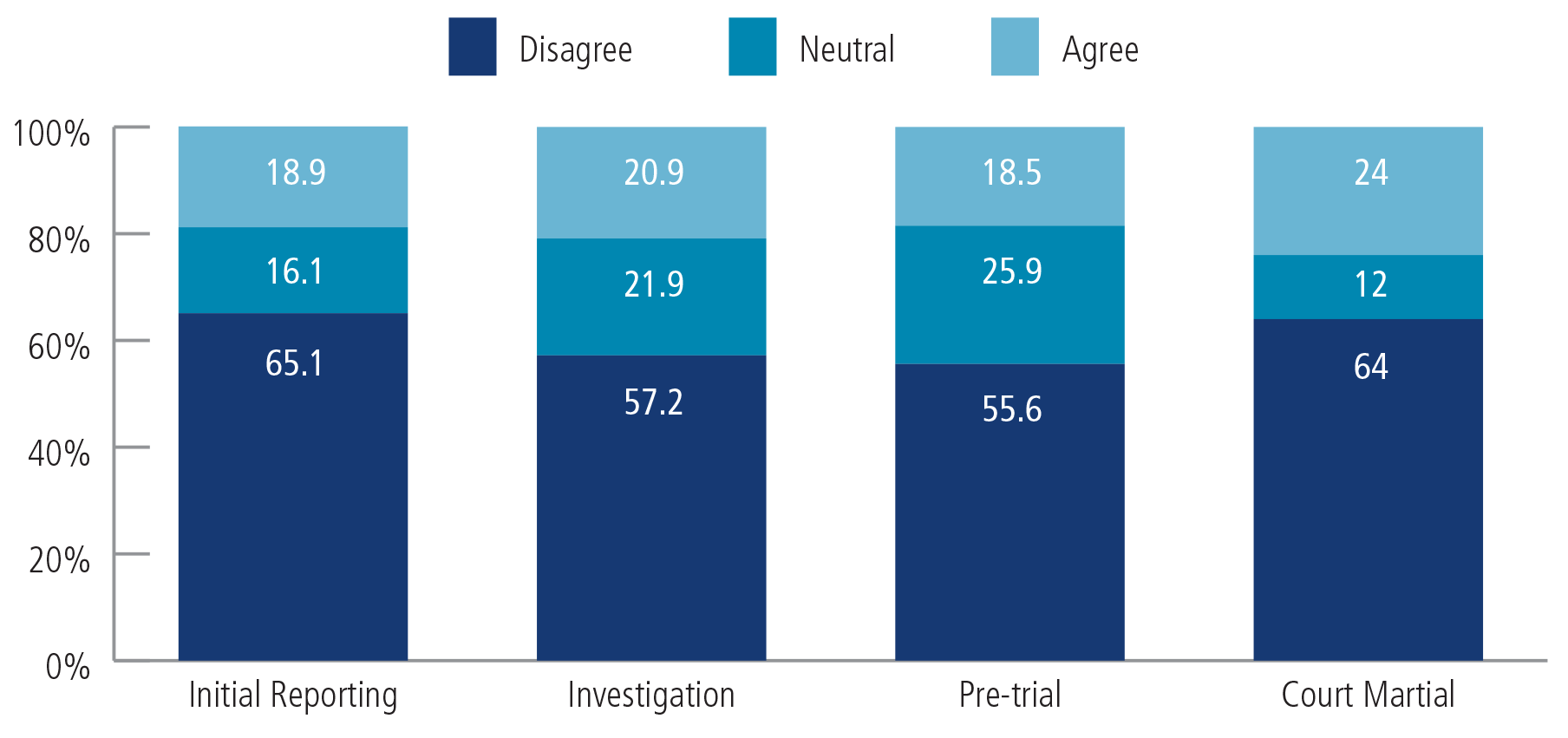

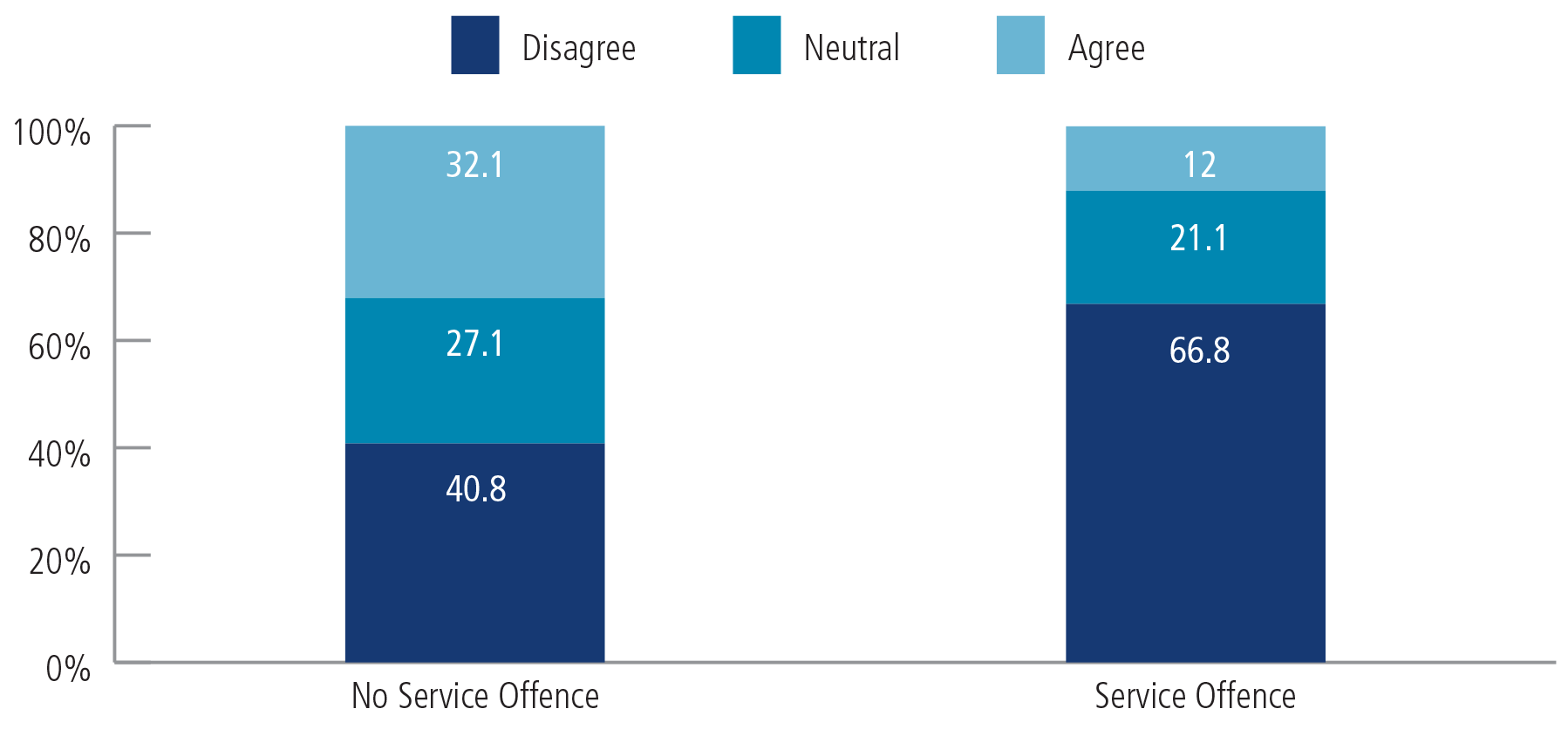

Definitions of Sexual Misconduct and Sexual Harassment