Collective voice for non-unionized workers: Issue paper

On this page

- Issue

- Background

- Collective voice and the Canada Labour Code

- Situation in the federally regulated private sector

- Applicable research

- Collective voice models

- Stakeholder perspectives

- Issues for the panel’s consideration

- Selected bibliography

Alternate formats

Issue

Judicial rulings, continued decline in unionization, new types of work arrangements, employer efforts to boost retention and performance and new approaches to enforcement are shining the spotlight on the ability of workers to join together to express their views and have a say in decisions affecting their working conditions. To what extent are there gaps in opportunities for collective voice for non-unionized workers in the federally regulated private sector (FRPS)? How could they be addressed?

Background

In 1970, Albert O. Hirschman argued in a landmark bookFootnote 1 that people have three choices in the face of an objectionable state of affairs: leave, complain or stay. “Exit”, “voice” and “loyalty”, as he termed them, are interconnected. Voice is a way to change, rather than escape, the situation. The greater the availability of exit, he contended, the less likely voice will be used, either individually or collectively - but the choice between exit and voice is also influenced by loyalty.

In the labour policy context, the concept of collective voice typically refers to the ability of workers to join together to express their views and have a say in decisions affecting their working conditions, such as wages, leave entitlements, scheduling and health and safety.

Historically, union representation has been considered the most important vehicle for collective voice. Employees in standard work arrangements could join a union based on their craft or industry. This provided an important source of power to express discontent without fear of reprisal, establish more favourable working conditions through the bargaining process and challenge managerial decisions through a system of grievance arbitration (Luchak and Gellatly, 1996). Union representation was also associated with higher productivity, lower employee turnover, economic growth, industrial peace and other benefits.

In recent years, a number of developments have called into question the effectiveness of this model and generated debate about whether there is a need for new and/or enhanced mechanisms for collective voice. For example:

- according to Statistics Canada, more than 70% of Canadian employees now do not belong to a union, compared to 62% in 1981. The rise in the share of non-union members has been particularly pronounced amongst males and youth

- the ongoing decline in unionization, combined with the proliferation of non-standard work arrangements, has resulted in many workers relying on statutory labour standards for their basic protections (if they are an employee but not a union member), or not being covered by them at all (if they are an independent contractor). For these workers, non-union mechanisms for exercising collective voice are one route for reducing the risks of exploitation

- in today’s tight labour market, employers increasingly see the use of collective voice mechanisms such as focus groups, consultation committees and surveys as integral to their efforts to attract and retain talent and boost productivity, knowing that workers not only want a greater say in the workplace compared to the 1990s, but want it on more issues (Freeman, 2007)

- the role of worker voice in the enforcement of labour standards is being reconsidered. Whereas in the past the focus has been on individual worker voice and complaints-based enforcement, attention has now turned to the potential to improve enforcement and better protect workers through mechanisms that amplify collective voice (Slinn and Tucker, 2013)

In addition, the Supreme Court of Canada has re-animated the guarantee of freedom of association under section 2(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and FreedomsFootnote 2. In its 2015 decision Mounted Police Assn. of Ontario v. Canada (Attorney General), the Court concluded that “the right to join with others and form associations […] to meet on more equal terms the power and strength of other groups or entities” is constitutionally protected and encompasses, but is not limited to, the right to join a union and bargain collectively.

Collective voice and the Canada Labour Code

Mechanisms for collective voice are found to some extent in each of the three parts of the Canada Labour Code (the Code).

As Harry Arthurs (2006) recognized in Fairness at work: Federal labour standards for the 21st century, Part III (Labour Standards) of the Code has historically provided minimal mechanisms for workers to express their collective views on working conditions: employers are required to consult with workers on the development of sexual harassment policies; and joint planning committees must be established to deal with group terminationsFootnote 3.

Part I (Industrial Relations) of the Code is intrinsically about collective voice. Based on the Wagner model of industrial relationsFootnote 4, it sets out the key elements of the collective bargaining regime for employees and employers in the FRPS, including provisions regarding union certification, collective agreements, dispute resolution, strikes and lock-outs.

Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) of the Code requires employers in the federal jurisdiction (in other words, the FRPS and the federal public service) with 20 or more employees to establish joint Work Place Health and Safety Committees to implement and monitor hazard prevention programs, deal with complaints and investigations and participate in decision-making about changes that may impact health and safety when the employer has 20 or more employees. When the employer has 300 or more employees, the Committees must also develop health and safety policies and programs. At least two employees must sit on each Committee and employees must make up at least half of the total membership. In organizations where employees are not represented by a union, the employee committee members must be selected by the other employees. Employers with fewer than 20 employees must have a health and safety representative (rather than a Committee).

Situation in the federally regulated private sectorFootnote 5

It is challenging to paint a picture of what collective voice looks like in practice in the FRPS. This section provides some statistical data and other information about collective bargaining coverage, joint labour-management committees and other initiatives related to the potential workers have to collectively express their views on labour standards issues.

Unionization

The traditional proxy for measuring collective voice is unionization. Two main indicators are used: the unionization rate (in other words, the number of employed individuals who are union members as a proportion of the total number of employed individuals) and the coverage rate (in other words, the proportion of employed individuals, both union members and non-unionized employees, covered by a collective agreement). The focus here is on the coverage rate, which can be examined using the Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey (FJWS).

According to the 2015 FJWS, about 34% of employees in the FRPS are covered by a collective agreement. In contrast, analysis of the 2017 Labour Force Survey (LFS) shows that 16% of employees in the private sector in Canada and 30% of Canadian employees overall were covered by a collective agreement in 2017.

Analysis using the LFSsuggests that the coverage rate in the FRPS has declined since the late 1990s, when it may have been about 40% or higher.

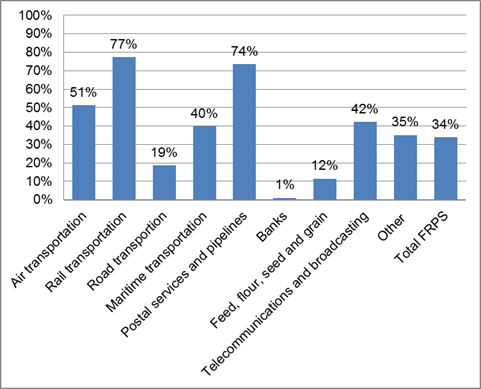

Based on the 2015 FJWS and as shown in Figure 1, the proportion of employees covered by a collective bargaining agreement in the FRPS varies significantly by sector. It ranges from a high of an estimated 77% of employees in the rail transportation sector to a low of an estimated 1% of employees in the banking sector.

Figure 1 - Text version: Rates of coverage by a collective bargaining agreement by industry in the FRPS, 2015

| Industry | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Air transportation | 51 |

| Rail transportation | 77 |

| Road transportation | 19 |

| Maritime transportation | 40 |

| Postal services and pipelines | 74 |

| Banks | 1 |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 12 |

| Telecommunications and broadcasting | 42 |

| Other | 35 |

| Total FRPS | 34 |

Source: 2015 FJWS.

The proportion also varies by company size. Again based on the 2015 FJWS, about 17% of companies in the FRPS have employees covered by collective bargaining agreements. Slightly less than half (43%) of the companies with 100 or more employees have some employees covered by collective bargaining agreements and, altogether, about 38% of the employees in these companies are covered by collective bargaining agreements and about 62% are not. In contrast, in companies with less than 100 employees, close to 10% of employees are covered and 90% are not.

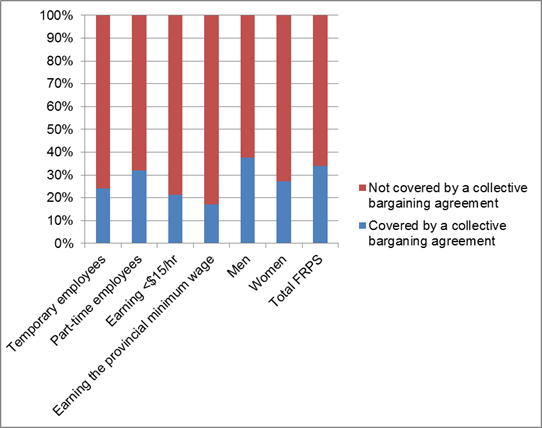

Analysis using data from 2017 LFS suggests that, as shown in Figure 2, coverage rates are much lower for temporary employees in the FRPS (about 24%), as well as for employees earning less than $15 per hour (about 21%) and earning exactly the minimum wage (about 17%), and that women have lower rates of coverage (around 27%) than men (around 38%).

Figure 2 - Text version: Rates of coverage/non-coverage by a collective bargaining agreement in the FRPS, 2017

| Covered or not covered | Temporary employees | Part-time employees | Earning <$15/hr | Earning the provincial minimum wage | Men | Women | Total FRPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covered by a collective bargaining agreement | 24% | 32% | 21% | 17% | 38% | 27% | 34% |

| Not covered by a collective bargaining agreement | 76% | 68% | 79% | 83% | 62% | 73% | 66% |

Source: Analysis of Labour Force Survey, 2017.

Looked at from a different perspective, in terms of the distribution of FRPS employees who are not covered by a collective agreement, the 2017 LFS suggests that roughly 58% of non-covered employees are men, 9% earn less than $15 per hour, 6% earn the minimum wage, 11% are part-time and 6% are temporary.

As reflected in the preceding analysis, some collective agreements in the FRPS cover temporary and specifically seasonal employees. These agreements may include provisions that, for example, establish time limits for temporary employees, grant temporary employees indeterminate status if their services exceed a maximum period of time and entitle seasonal employees to be recalled to temporary and casual positions when they receive an end of season noticeFootnote 6.

Only one collective agreement covering non-standard workers who are not considered employees was identified in the Labour Program’s August 2018 analysis of a representative sample of 231 agreements in the FRPS. The agreement, between the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Media Guild (CMG), was signed in November 2013. One of the principles in the agreement is that freelancers are to be “paid fairly for their work based on fiscal realities” and “shall have the right of protection afforded by a written contract and such contract shall be signed before the commencement of any assignment covered by this Agreement. Where standard forms are used, the format of such forms will be agreed upon by the Parties.”

Joint labour-management initiatives in unionized companies

The 2015 edition of the FJWS offers some limited insight into joint labour-management initiatives, specifically grievance mediation procedures and joint labour-management committees (for example, on labour relations, productivity, quality control, training and pensions), in companies in the FRPS with employees covered by collective bargaining agreements.

The 2015 FJWS found that about 85% of unionized companies with 100 or more employees had at least one joint labour-management initiative in place, as did about 72% of unionized companies with 20 to 99 employees and less than 20% of unionized companies with less than 20 employees.

The 2015 FJWS also found that road transport and postal services and pipelines were the industries in which the likelihood of having at least one joint labour-management initiative in place was the least common, at 23% and 33%, respectively. In other industries, at least 50% of companies had at least one in place.

In a sample of 231 collective agreements examined by the Labour Program in 2018, 40 included provisions related to joint labour-management initiatives. These were primarily joint labour-management committees on issues such as pensions and benefits, women, job sharing, learning and development, health and safety, and planning in cases of group termination. One agreement, between the Yukon Hospital Corporation and the Public Service Alliance of Canada, included a provision to continue a joint consultation committee with members from both parties and another union.

Other voice mechanisms

Employers in the banking sector, where the union coverage rate is the lowest, have established a variety of workplace consultation mechanisms for employees to collectively express their views. For example, TD Bank runs an employee engagement survey twice a year that allows employees to provide feedback on more than 30 aspects of their current work experience and solicits their views on how TD can foster a better workplace. Just under 90% of employees participated in 2017. The survey is managed by an independent third party.

The Canadian Freelance Union (CFU) represents self-employed media and communications workers, several hundred of whom work in the FRPS. The CFU is not a bargaining unit and does not negotiate directly on behalf of its members on labour standards or other issues. Instead, it provides grievance support to assist members in managing disputes with clients, provides contract advice and helps members interpret and understand both the contracts they are offered and those they enter in order to protect their rights.

Applicable research

This section provides an overview of some of the key themes and issues in recent research related to collective voice for non-union workers.

Declining unionization

Interest in mechanisms for collective voice has been spurred by the steady decline in unionization in Canada and across the industrialized world over the past half-century.

According to Statistics Canada data,Footnote 7 the proportion of employees in the Canadian workforce who are not unionized rose from 62% in 1981 to 70% in 2017, with most of the increase taking place in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s and amongst male workers and young workers. The non-unionization rate for women remained very stable over the period, hovering between 68% and 71%.

Why the overall decline in unionization has occurred has sparked considerable research interest. One important factor has clearly been structural changes in the Canadian economy and the labour force, such as the reduction in the share of employment accounted for by more highly unionized industries (for example, manufacturing and mining) and in the share of blue-collar occupations within industries. Another is globalization, at least in manufacturing, which has increased the credibility of employer threats of job loss in the event of employees unionizing.

Research also shows that the adoption of mandatory vote systems for union certification, as has occurred in some jurisdictions in Canada beginning with Nova Scotia in 1977, British Columbia in 1984 and Alberta in 1988, is associated with reductions in unionization rates (Riddell, 2004). However, it is not clear whether that is because mandatory vote systems allow employees to voice their preference more freely compared to card-check systems, or because employers are more able to interfere in employees’ choices.

Relatedly, employer resistance to unionization or use of suppression practices, such as interfering in certification drives, purposefully disrupting work schedules to make it more difficult for employees to participate in union activities and communicating anti-union sentiments, can impact unionization rates. In a 2002 study of eight Canadian jurisdictions, Bentham found that employer resistance to certification applications was the norm, with 80% of employers overtly and actively opposing union certification drives. She also concluded that, depending on its form, employer resistance can have an impact on both initial certification outcomes and on the probability that the parties will establish and sustain a positive collective bargaining relationship. She notes, however, that a handful of researchers have concluded that employer interference, such as shifting work to other facilities, “may, in some instances, cause a rebound effect and increase, as opposed to undermine, worker solidarity.”

Other studies have found that many workers today simply do not want to join a union. When asked in a 2013 Harris/Decima poll conducted for the Canadian Association of University Teachers, 43% of the 2,000 Canadians who responded agreed with the statement “If I had a choice, I’d never join a union” and 45% disagreed (CAUT Council, 2013). One of the key reasons why people hold negative views towards unions is that they see them as large, remote, bureaucratic organizations that foster adversarial rather than cooperative solutions (Gomez, 2016).

Union wage stagnation and the erosion of certain benefits may also reduce the appeal of unionization. Accounting for differences in occupation, education and age between unionized and non-unionized workers, the union wage premium between workers—the difference in wages between union and non-union workers—has been falling steadily in Canada, from about 20% in the 1980s to 8% in 2002 (Fang and Verma, 2002). In addition, wage increases settled through bargaining have barely exceeded inflation in recent years, in both the public and private sectors (Jackson, 2013).

Another key theme in the literature is the failure of unions themselves to respond to the “representation gap”, or unsatisfied demand for union membership. About one in three non-unionized workers in Canada consistently say that they would like to join a union if they had the opportunity (Gomez, 2016). The representation gap has been a common factor in calls for union renewal through “organizing the unorganized”, greater union democracy and other strategies, especially since the 2000s (Kumar, 2008; Rose, 2008).

On the other hand, the desire for alternative, non-union models of collective representation is high. Gomez (2016) has estimated, using 2014 data, that 73% of Canadian workers are either definitely or probably willing to participate in an employee organization other than a traditional union that discusses workplace issues with management (compared to just under 40% who would prefer to belong to a union). In addition, there are reasons to believe that support for non-union mechanisms for collective voice is higher amongst some groups, such as millennial workers who now make up the largest cohort in the Canadian workforce, have high expectations about being engaged in the workplace and are more likely to opt for “exit” when they are unhappy in the workplace (Hawkins et al., 2014).

Why collective voice matters

The research is clear that opportunities for workers to join together to express their views and have a say in decisions affecting their working conditions generally have positive impacts for workers and employers alike. For instance, access to collective voice mechanisms ranks high amongst the factors that encourage employee retention, along with good wages and access to training (Spencer, 1986; Batt et al., 2001). It has been shown to improve job quality for both vulnerable and non-vulnerable workers (Piasna et al., 2010) and reduce exit behaviours, including quit rates (Freeman and Medoff, 1984) but potentially not absenteeism (Luchak and Gellatly, 1996), and the significant costs they entail for employers who need to find, hire and train replacement workers. Various studies suggest that it can lead to improved compliance with labour laws (Vosko, 2013; Fine, 2013). Others emphasize it is intrinsically good, reflecting commitment to democracy in the workplace (Bryson et al, 2013).

In addition, worker voice has been linked to civic engagement. One study, which surveyed more than 18,000 Canadians, concluded that “Union members are 10 to 12 percentage points more likely to vote than non-union members across all three levels (federal, provincial, and municipal) of electoral activity. This overall union voting gap is replicated when broader measures of civic engagement - such as signing a public petition or volunteering to help in a political party - are employed” (Bryson et al., 2013).

In contrast, studies show that workers are less likely to speak out about problems in the workplace for fear of reprisal if they do not have access to collective voice mechanisms. This is particularly true for non-unionized workers and those in non-standard work, as well as women. For instance, using survey data collected in 2005, Lewchuk (2013) concludes that “the precariously employed were six to seven times more likely to report that raising health and safety issues would have negative employment consequences”. He also reports that “women were about 25% less likely than men to be concerned about using voice, while white workers were half as likely as workers from racialized minorities to be concerned about using voice”. Moreover, in an analysis of the fifth wave of the European Working Conditions Survey, Piasna et al. (2010) found that vulnerable workers (defined by their gender and low education levels) were less likely to have access to employee participation (or voice) methods, although they did not find a strong difference between low educated women and low educated men.

Further, lack of access to collective voice mechanisms tends to produce high-conflict/low-trust workplace relations and under-performing enterprises (Kochan, 2005) and is associated with workers having negative emotions like resentment and anger, which can stifle creativity and motivation and negatively impact productivity (Perlow, 2003). It can also lead to workers communicating their frustration and grievances with their employer on social media and other online public fora, which can negatively impact the employer’s brand. Overall, the research indicates that lack of access to collective voice—and the stable and cooperative workplace relations that it fosters—puts downward pressure on economic and social well-being.

Budd (2012) argues that meaningful worker participation in the decision-making process contributes to a variety of positive outcomes which culminate in enhanced productivity; and that voice is one of three mutually supportive pillars of a successful and enduring employment relations system (along with efficiency and equity). Budd also recommends a broader conceptualization of collective voice, one that connects voice with the terms and conditions of work, but also with input, expression, autonomy and self-determination.

Collective voice and non-standard workers

Workers in non-standard forms of employment are less likely to be represented by a union. They may be prohibited by law from joining a union, may fear employer retaliation for joining a union, or may not be able to afford to join a union because of the volatility in their income (ILO, 2016). They may simply have no time to participate in union activity as they struggle to make ends meet or may not see themselves as having sufficient shared interests with union members. They may also believe, especially if they have in-demand skills, that they have relatively more power to bargain with employers on their own.

Union strategies, structures and business models have also been singled out as barriers to effective union-based collective voice for non-standard workers. As Gumbrell-McCormick (2011) concludes in her analysis of a three-year project examining unions in 10 European countries, “unions will have to make substantial changes to their structures, thinking and way of operating in order to be fully able to respond to the challenge of this growing form of work”. The geographical diversity of non-standard workers also poses basic organizational challenges, as does their limited attachment to a single workplace or employer, both factors which take on even further importance in the context of the gig economy. The interests of non-standard and standard workers may also conflict, for example on issues related to the use of contingent workers. A 2016 ILO report on non-standard employment around the world calls for more efforts to build the capacity of unions to represent workers in non-standard jobs.

Some unions have recently put a priority on recruiting non-standard workers and launched targeted organizing drives (Gumbrell-McCormick, 2011). In the Netherlands, the Confederation of Dutch Trade Unions has identified sectors in which workers face particular risks as a result of being in non-standard work, including the postal services, construction and temporary help agency industries, and actively recruited members in these sectors. New unions or new branches of unions have been formed to represent the special interests of workers in non-standard work, for example in the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea and Nigeria (International Labour Office, 2015).

In Canada, the Canadian Media Guild (CMG) has taken deliberate steps over the past decade to establish itself as a collective voice for freelancers. Of the CMG’s 6,000 members, most of whom work in the FRPS in the broadcasting industry, about 800 are freelancers at any given time. Freelance members pay reduced dues and the CMG represents them with employers considered to be problematic, on public policy issues and in collective bargaining with the CBCFootnote 8.

At the same time, some non-standard workers, often helped by technology and often in the same or similar industries, have come together to establish non-union mechanisms for exercising their collective voice. In California, for example, the Warehouse Worker Resource Center is a non-profit organization that advocates on behalf of workers for higher wages and better working conditions in the logistics industry. The industry makes extensive use of staffing agencies and third-party logistics providers and workers are vulnerable because, in contrast to many in the trucking sector, they only supply their own labour, not assets.

While there appears to be little research on the extent to which employers may pose a barrier to collective voice for non-standard workers, it is reasonable to expect increased mobilization of non-standard workers to translate into more pressure on employers, especially individually or in specific industries, to offer improved working conditions. In addition, there are cases where associations of employers have shown openness to negotiating the terms and conditions of work performed by non-standard workers. For instance, in Germany, the Suedwestmetall employers' federation reached a pilot agreement in 2012 with IG Metall, which represents workers in the metal and electrical industry, that allows for negotiations to regulate the use of temporary agency workers, including provisions regarding equal pay and requirements to offer such workers permanent employment (Xhafa, 2015).

Non-union alternatives for collective voice

Driven primarily by the benefits of collective voice, debate about the future of unions and the challenges faced by non-standard workers seeking to exercise collective voice, considerable research has been conducted on non-union mechanisms.

Some of the main considerations addressed in the research include:

- whether mechanisms should be statutory or non-statutory

- whether they would operate in the workplace or be external to it

- whether they would apply generally or be sector- or workplace-specific

- the degree of independence mechanisms have from the employer

- whether there would be protections against reprisal for those who participate

- the capacity of workers to support or use different mechanisms

- the relationship of mechanisms to formal collective bargaining

- overall effectiveness (for example, whether voice heard and concerns resolved)

Collective voice models

A number of examples of mechanisms that permit workers to exercise collective voice have been provided throughout the preceding research synthesis. This section outlines some additional models for illustrative purposes.

Joint workplace committees

European Union (EU) member states are required, under European Council (EC) directive, to provide for the right to establish European Works Councils in multinational companies or groups of companies that have at least 1,000 employees in the EU or the European Economic Area. Through the works councils, workers are informed and consulted by management about the status of the company and European level-decisions that could affect employment or working conditions and, in some cases, worker representatives have a seat on the corporate board. A works council can be composed of employee representatives alone, as is the model in Germany, or both employee and employer representatives, as is the model in France. The latter model is the most common. Depending on the national legislation that transposes the EC directive and the works council agreement itself, the works council may or may not be empowered to participate in negotiating salaries, collective bargaining, hours of work, health and safety, or other workplace issues (De Spiegelaere, 2015).

For example, in the Netherlands, under the Works Council Act, it is mandatory for employers with more than 50 employees to have a works council in place consisting of elected employees which meets with the employer at least twice a year to discuss labour standards issues as well as occupational health and safety and employment equity issues. The role of the works council is to represent and protect the interests of employees vis-à-vis the employer. Works councils have rights, including the right to be consulted prior to major decisions and measures and the right of consent in the event of certain changes regarding terms of employment.

In Fairness at Work, Arthurs (2006) recommended legally sanctioning through the Code the creation of Workplace Consultative Committees (WCCs) that would facilitate consultation between employers and workers on labour standards issue in non-unionized workplaces. Arthurs stated that WCCs could be “formed by nomination, election or lottery, or volunteers or any other manner, so long as the employer does not attempt to control the outcome of the consultation through its selection of WCC members”.

Worker organizations

In 2013, Unifor, the largest private-sector union in Canada, launched an initiative called Community Chapters. Community chapters provide some (but not all) benefits of collective voice and power for workers who would not normally be able to certify traditional bargaining units in their workplaces, such as workers who are in hard-to-organize occupations, are geographically dispersed or do not have one workplace. Community chapters must adhere to Unifor’s constitution and are associated with a Unifor local. Members pay minimal dues and can opt-in to health care benefits. The first two community chapters were national in scope, the Canadian Freelance Union which represents self-employed media and communications workers (see above) and the Unifaith Community Chapter which represents clergy and other workers at the United Church. Local community chapters have also been established, such as the East Danforth Community Chapter.

In the United States, section 7 of the National Labour Relations Act provides non-supervisory employees, union and non-union, with the right to engage in, or to refrain from engaging in, “concerted activity for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection”. As defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, “mutual aid and protection” includes employees’ efforts to “improve current terms and conditions of employment or otherwise improve their lots as employees through channels outside the immediate employee/employer relationship”Footnote 9. The Act does not limit the manner, time or place in which employees engage in “concerted activity”. In recent years, conversations about workplace issues amongst employees on social media have been found to be protected against retaliation (Zemel, 2011).

Third-party advocates

The Workers’ Action Centre (WAC) is a member-based organization created in 2016 to advocate on behalf of workers in precarious jobs in Ontario. WAC’s members are workers directly impacted by low wages and poor working conditions. Located in Toronto, the organization is a key player in the Fight for $15 and Fairness campaign and, working closely with unions and community organizations, had significant impact on Bill 148 (Fair Workplaces, Better Jos Act, 2017) and the recent labour and employment standards reforms in Ontario. WAC also provides a hotline and clinics to help members understand their rights at work.

Workers’ advisor or advocate offices have been established under occupational health and safety legislation in all jurisdictions across Canada. These offices are typically independent agencies of the department responsible for health and safety, but in a few cases are associated with another department. They provide advice and representation to workers, in workplace injury cases and on occupational health and safety issues more generally, including issues related to reprisal.

In Ontario, for example, the Office of the Worker Adviser, an independent agency of the Ontario Ministry of Labour, provides advices, services and representation for non-unionized workers on workplace insurance matters and occupational health and safety reprisal (for example, with respect to mediation or appeals to the workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal). Unionized workers are not eligible for support. Established in 1985, the Office has 16 regional/district locations across the province and, in partnership with local organizations, delivers educational services in smaller communities.

In Manitoba, the Worker Advisor Office provides support and representation to injured workers, both non-union and union, who are dealing with the provincial Workplace Compensation Board. Since 2016, the Office has been part of the Labour and Regulatory Services Branch of the newly-formed Department of Growth, Enterprise and Trade.

Sector-based approaches

The federal Status of the Artist Act seeks to improve the economic, social and political status of professional artists. Under the Act, which came into effect in 1992, a group of artists in the FRPS who are independent contractors can be recognized and certified by the Canada Industrial Relations Board as an artists’ association with the exclusive right to represent its members in a specific sector for the purposes of collective bargaining with producers. Artists include authors, directors and other professionals who contribute to the creation of a production. An artists’ association is defined as "any organization, or a branch or local thereof, that has among its objectives the management or promotion of the professional and socio-economic interests of artists who are members of the organization." Artists’ associations and producers can enter into “scale agreements” that set out the minimum terms and conditions for the provision of the artists’ services and related matters (more favourable terms may be negotiated on an individual basis). About 25 artists’ associations are currently certified by the Board. The Act does not apply to artists in traditional employment relationships, who are covered by the Code. Similar status of the artist legislation has been adopted in Quebec (1987), Saskatchewan (2002) and Ontario (2007).

Quebec’s Act Respecting Collective Agreement Decrees provides that the Government “may order that a collective agreement respecting any trade, industry, commerce or occupation shall also bind all the employees and professional employers in Quebec or in a stated region of Quebec, within the scope determined in such decree”. The agreement then establishes the minimum standards for the employees that it covers. The Act was significantly amended in 1996 to specify detailed economic criteria that must be considered in decisions to issue, renew or amend a decree (for example, impacts on an industry’s competitiveness outside of Quebec) and to narrow the scope of the provisions and the types of collective agreements which can be extended by decree. In 2015, 14 decrees were in force in the province, covering 75,000 workers (for example, in the automotive services and building materials industries). Until 2000, Ontario’s Industrial Relations Act provided a similar mechanism for establishing a schedule of wages and working conditions that was binding on all employers and employees in a particular industry across a geographical zone.

Graduated freedom of association

Doorey (2012) has proposed legislating a set of “thin” or “thicker” rights already established by the courts in Canada. Thin rights would include the freedom to establish, join and maintain employee associations (union and non-union). Thicker rights would include the right to make collective representations to employers through employee associations and the right not to be punished, terminated or interfered with by the employer when exercising that right. The employer would also be obligated to receive collective employee representations and engage in meaningful dialogue and to consider representations in good faith.

Stakeholder perspectives

Based on stakeholders’ submissions to the recent labour policy reviews in Alberta and Ontario and the federal consultations held from May 2017 to March 2018 on modernizing federal labour standards (ESDC, 2018), the absence of mechanisms for collective voice is a growing issue in the new world of work.

A few of the personal stories submitted during the federal consultations described workers struggling to speak up in the workplace and lacking formal ways to do so as a group; experiencing retaliation for raising issues; and having fears about reprisal.

In its submission to the consultations, Federally Regulated Employers-Transportation and Communications (FETCO), whose members are predominantly unionized firms, emphasized that new and additional labour standards bring extra costs for employers and cited the administrative costs associated with “the establishment of mandatory committees” as an example.

Issues for the panel’s consideration

- To what extent is there a need to enhance opportunities for collective voice on labour standards issues for non-unionized workers in the federally regulated private sector?

- Are there gaps that should be addressed? How and by who? Who would benefit? Are there downsides that should be taken into account?

- Are there currently any barriers in the Code to enhancing collective voice for non-unionized workers? If there are, what should be done about them, if anything?

- What would successful implementation of improved or new non-union voice mechanisms look like? How could it be measured?

Selected bibliography

Arthurs, H.W. (2006). Fairness at work: Federal labour standards for the 21st century. Federal Labour Standards Review. (PDF, 1.5 MB)

Batt, R., Colvin, A., and Keefe, J. (2002). Employee voice, human resource practices, and quit rates: Evidence from the telecommunications industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55, 573 to 594.

Bentham, K.J. (2002). Employer resistance to union certification: A study of eight Canadian jurisdictions. Érudit, 57(1), 159 to 187.

Berg, J. (2017, January 4). Addressing the challenge of non-standard employment, World Bank Jobs Group [Blog post].

Boxall, P., and Purcell, J. (2003). Strategy and Human Resources Management. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bryson, A., Gomez, R., Kretschmer, T., and Willman, P. (2013). Workplace voice and civic engagement: What theory and data tell us about unions and their relationship to the democratic process. Osgoode Hall Law Journal 50(4), 965 to 998.

Budd, J.W. (2012) The future of employee voice. Center for Human Resources and Labor Studies, University of Minnesota. (PDF, 66 KB)

CAUT Council. (2013, November 29). CAUT Harris/Decima public opinion pol (PDF version 2.20 MB).

Chaykowski, R., Mazerolle, M., and Gomez, R. (2017, September 3). Is a 21st century model of labour relations emerging in Canada? The Globe and Mail.

Cobble, D.S., and Vosko, L.F. (2000). Historical perspectives on representing nonstandard workers. In F.J. Carré, M.A. Ferber, L. Golden & S.A. Herzenberg (Eds.), Nonstandard work: The nature and challenges of changing employment relationships, 291 to 312. Champaign, IL: Industrial Relations Research Association, University of Illinois.

De Spiegelaere, S., and Jagodzinski, R. (2015). European Works Councils and SE Works Councils in 2015. Facts and Figures. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute.

Doorey, D.J. (2012). Graduated freedom of association: Worker voice beyond the Wagner model. The Future of the Wagner Act Conference. London: Faculty of Law, University of Western Ontario. (PDF, 198 KB)

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC). (2018). Modernizing Federal Labour Standards—What We Heard.

Fang, T., & Verma, A. (2002). Union wage premium. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 14(4), 17 to 23.

Fine, J. (2013). Solving the problem from hell: Tripartism as a strategy for addressing labour standards non-compliance in the United States. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(4), 813 to 843.

Freeman, R.B. (2007, February 22). Do workers want unions? Yes more than ever! EPI Briefing Paper 182. Economic Policy Institute.

Freeman, R.B., and Medoff, J.L. (1984). What do unions do? New York: Basic Books.

Gomez, R. (2016). Employee voice and representation in the world of work: Issues and options for Ontario. Changing Workplaces Review 2015. (PDF, 1.56 MB)

Gumbrell-McCormick, R. (2011). European trade unions and ‘atypical’ workers. Industrial Relations Journal, 42(3), 293 to 310.

Hawkins, N., Vellone, J., and Wright, R. (2014). Workplace preferences of Millennials and Gen X: Attracting and retaining the 2020 workforce. The Conference Board of Canada.

Hirschman, A.O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2016). Non-standard employment around the world: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects. International Labour Office.

Jackson, A. (2013). Up against the wall: The political economy of the new attack on the Canadian labout movement. Just Labour: A Canadian Journal of Work and Society, 20, 50 to 63. (PDF, 135 KB)

Khullar, R., and Cosco, V. (2016). The SCC reimagines freedom of association in 2015. Constitutional Forum, 25(2), 27 to 38.

Kochan, T. (2005). Employee voice in the Anglo-American world: Contours and consequences. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA). Philadelphia, PA: LERA.

Kumar, P. (2008). Whither unionism: Current state and future prospects of union renewal in Canada. Discussion Paper #2008-04, IRC Research Program.

Lewchuk, W. (2013). The limits of voice: Are workers afraid to express their health and safety rights? Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(4), 789 to 812.

Luchak, A.A., and Gellatly, I.R. (1996). Exit-voice and employee absenteeism: A critique of the industrial relations literature. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 9(2), 91 to 102.

Perlow, L.A., and Williams, S. (2003). Is Silence Killing Your Company? Harvard Business Review.

Piasna, A., Smith, M., Janna, R., Rubery, J., Burchell, B., and Rafferty, A. (2013). Participatory HRM practices and job quality of vulnerable workers, The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 24(22), 4094 to 4115.

Riddell, C. (2004). Union certification success under voting versus card-check procedures: Evidence from British Columbia, 1978–1998, Industrial and Labour Relations Review, 57(4), 493 to 517.

Rose, J.B. (2008). The prospects for union renewal in Canada. In A.E. Eaton (Ed.), 60th Annual Proceedings of the Labour and Employment Relations Association, 101 to 107. Champaign, IL: LERA. (PDF, 94.53 Kb)

Slinn, S., and Tucker, E. (2013). Voices at work in North America: Introduction, Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(4), i–ix. (PDF, 218.17 Kb)

Spencer, D.G. (2017). Employee voice and employee retention, Academy of Management Journal 29(3), 488 to 502.

Tucker, E. (2014). Shall Wagnerism have no dominion?, Just Labour: A Canadian Journal of Work and Society 21. Osgoode Hall Law School Legal Studies Research Paper No. 30.

Unifor. (2015). Building balance, fairness, and opportunity in Ontario’s labour market, Submission by Unifor to the Ontario Changing Workplaces Consultation. (PDF, 2.59 Mb)

Vosko, L.F. (2013). Rights without remedies: Enforcing employment standards in Ontario by maximizing voice among workers in precarious jobs. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(4), 845 to 874. (PDF, 218.17 Kb)

Zemel, M. (2011). The Facebook firing cause—can it happen in Canada? First Reference. Inside Internal Controls [Blog post].

Xhafa, E. (2015). Collective bargaining and non-standard forms of employment: Practices that reduce vulnerability and ensure work is decent. International Labour Office, Issue Brief No. 3.

Page details

- Date modified: