Evaluation of the Skills and Partnership Fund

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Executive summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Introduction

- The Skills and Partnership Fund

- Evaluation approach

- Socio-economic profile and labour market context of Indigenous Peoples in Canada

- Evaluation findings

- Program relevance

- Program design and delivery

- Partnerships, collaboration and labour market integration

- Profile of SPF participants

- Outcomes of participation

- Broader impact of participation

- COVID-19 disruptions and responses

- Challenges and promising practices

- Performance measurement and data collection

- Conclusions, observations and recommendations

- Appendix A: Types of interventions funded through the SPF

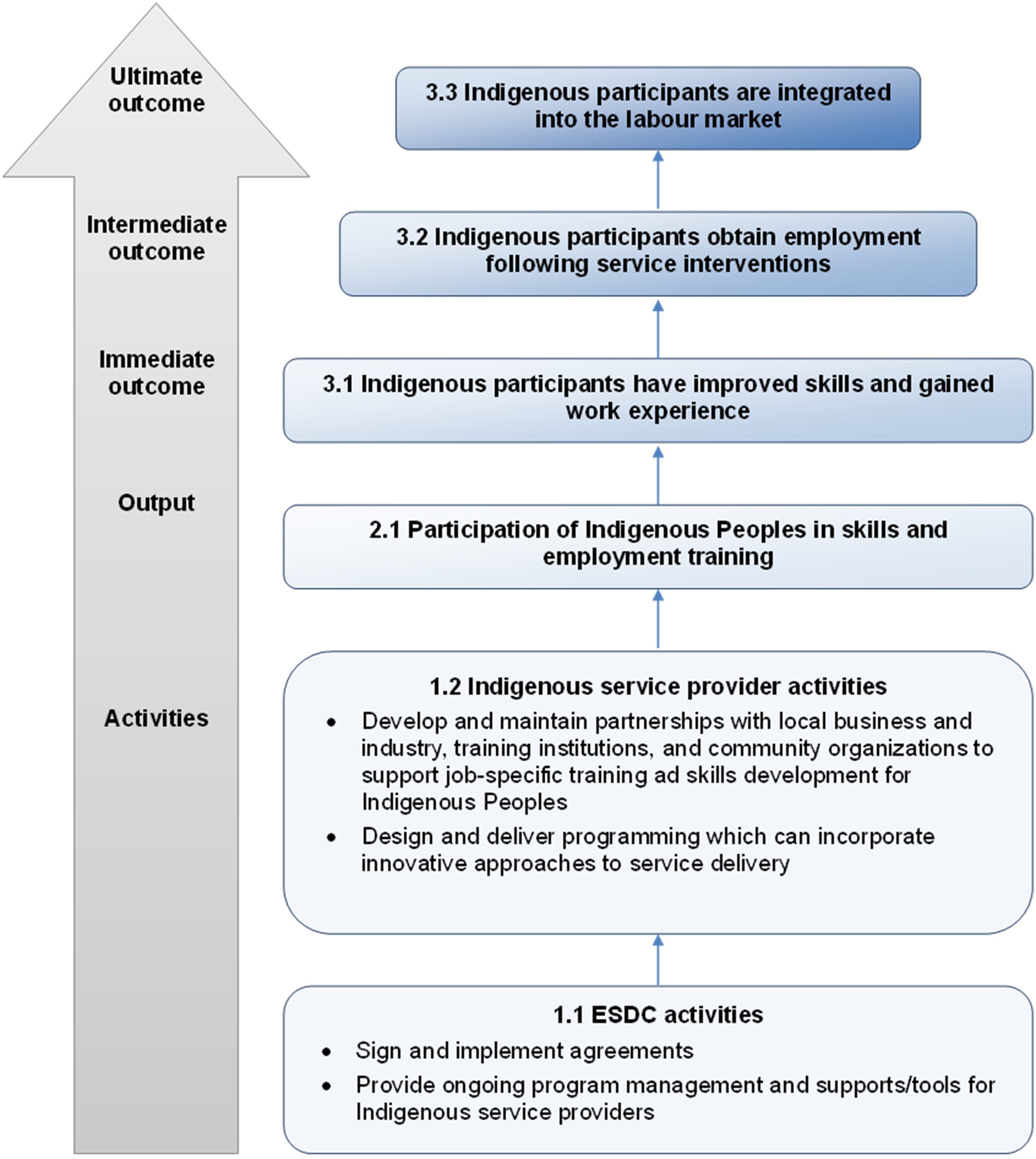

- Appendix B: SPF logic model, key outcomes and performance indicators

- Appendix C: Characteristics of case study projects

Alternate formats

Evaluation of the Skills and Partnership Fund [PDF - 985 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training program

- SA

- Social assistance

- SPF

- Skills and Partnership Fund

List of figures

- Figure 1: Highest educational attainment rate (25-64 years) by Indigenous identity, 2021

- Figure 2: Adults aged 25 to 64 years with a postsecondary qualification, by Indigenous identity and level of remoteness, 2021

- Figure 3: Median annual income in 2020 among adults aged 25 to 64, by Indigenous identity and by gender

- Figure 4: Location of SPF projects

- Figure 5: Socio-demographic profile of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants

- Figure 6: Types of barriers experienced by SPF participants

- Figure B. 1.: SPF logic model

List of tables

- Table 1: Annual and total expenditures by province and territory (in millions)

- Table 2: Labour force employment rates among adults aged 25 to 64 years, by Indigenous identity and highest level of education, 2021

- Table 3: Employment rates among adults aged 25 to 64 years by Indigenous identity and level of remoteness, 2021

- Table 4: Unemployment rates among adults aged 25 to 64 years by Indigenous identity and level of education, 2021

- Table 5: Unemployment rates among adults aged 25 to 64 years by Indigenous identity and level of remoteness, 2021

- Table 6: Annual averages of labour market outcomes for 2017 and 2018 SPF participants

- Table 7: Proportion and change in percentage of participants by average annual earnings ranges

- Table 8: Pre-participation labour market characteristics of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants from by intervention type

- Table 9: Labour market outcomes by type of SPF intervention for 2017 and 2018 participants

- Table 10: Labour market outcomes of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants by participant type

- Table 11: Labour market attachment and outcomes of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants by Indigenous population group

- Table 12: Labour market attachment and outcomes of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants by gender

- Table 13: Labour market attachment and outcomes of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants by age group

- Table 14: Labour market attachment and outcomes of 2017 and 2018 SPF participants by type of location (rural/remote and urban)

Executive summary

The Skills and Partnership Fund (SPF) supports short-term, demand driven, partnership-based projects aiming to support First Nations, Inuit and Métis participants along the path to employment. Led by Indigenous agreement holders, the projects are designed and delivered in partnership with new or existing public, private, and non-profit sector partners.

The 2016 call for proposals funded a broad range of projects through 2 funding streams:

- the Innovation stream supported projects that explored the use of diverse approaches to enhancing the employability of Indigenous individuals experiencing barriers to employment, and

- the Training-to-Employment stream supported projects that provided training to help participants fill existing or emerging jobs

The SPF funds projects in all provinces and territories, on and off reserve, and in urban, rural and remote areas.

The SPF investment

In the 5 fiscal years between April 2016 and March 2021, the total expenditures of the program were approximately $224.5 million.Footnote 1

Evaluation scope and objectives

The evaluation focuses on the 52 SPF projects that were funded through the 2016 call for proposals and implemented over the 5 fiscal years from April 2017 to March 2022.

The evaluation seeks to:

- provide timely information on challenges, opportunities and best practices relating to program design and delivery

- describe how the SPF is meeting the needs of individuals and communities and clarify the contribution of project partnerships to participants' labour market outcomes

- contextualise findings relating to program performance and provide insight into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the projects and their participants

- assess the data being collected and identify participants' labour market outcomes

Evaluation methodology

The evaluation draws from multiple lines of qualitative and quantitative evidence, including:

- a literature review

- a document review

- key informant interviews

- case studies

- labour market outcome analysis, and

- a data assessment

Where possible, given the data and methodological limitations, a Gender-Based Analysis plus lens is applied.

Key findings

Indigenous Peoples face persistent economic and systemic barriers. Relative to non-Indigenous Canadians, they have lower educational attainment, employment rates and income, and a higher unemployment rate.

By helping participants to improve their labour market attachment and supporting Indigenous communities to benefit from emerging economic opportunities, the SPF:

- addresses key government priorities relating to labour market development and economic reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, and

- responds to the educational, employment, and economic needs of Indigenous individuals, and

- is designed in way that reflects lessons learned about project-based funding and input provided by Indigenous partners

Project design and delivery

Partnerships: SPF agreement holders worked with public, private, and non-profit sector partners to design and deliver interventions, and to connect participants to work experience and employment opportunities. Partners generally also committed cash and in-kind contributions to the projects. In fact, half of the projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals indicated that a quarter or more of project resources would be provided by partners.

Objectives: while the ultimate objective of most projects was to help participants to obtain and maintain employment, most also sought to support pre-employment outcomes for a large portion of their participants. In other words, the immediate outcome sought for many participants was increased employability.Footnote 2

Sectors targeted by SPF projects: the most common sectors targeted for training and employment were trades (60%), construction (38%), and mining (30%).

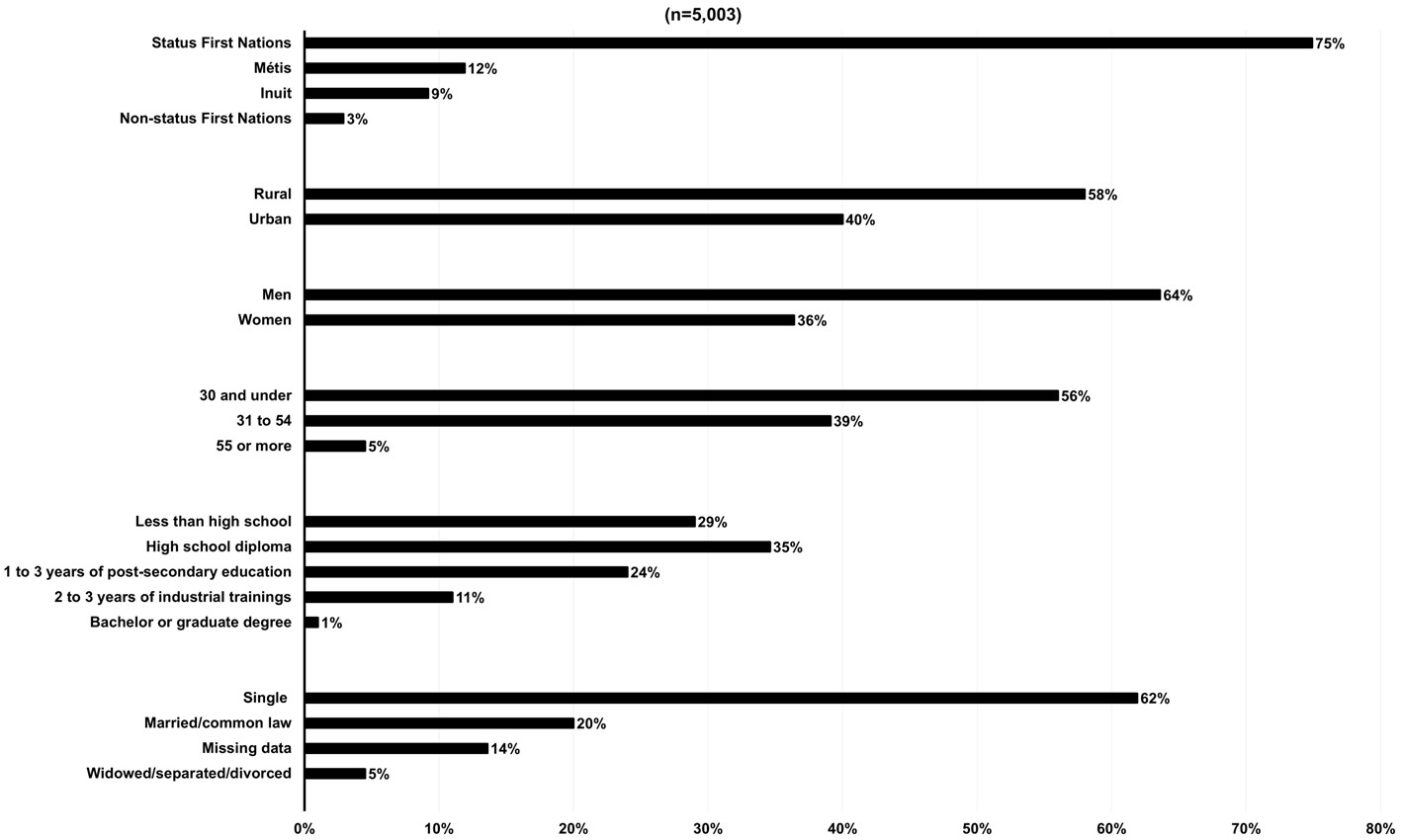

Participants: The program reached individuals in rural or remote areas (58%), and in urban areas (40%). Most participants in SPF interventions were status First Nations (75%), male (64%), and single (62%). Participants had relatively low educational attainment; over a quarter (29%) had not completed high school and only 1% had obtained a university degree.

Post-participation labour market outcomes

The outcome analysis focused on the post-participation labour market outcomes of the 5,003 participants who started an SPF-funded intervention in 2017 and 2018.Footnote 3

Outcomes should be interpreted with caution as they may be influenced by broader trends and shifts in the labour market and economy. Because participant outcomes were not compared to those of non-participants, they cannot be attributed solely to program participation. The post-participation period overlapped with COVID-19 disruptions to the economy and labour market, and with pandemic response measures that may have influenced participants' employment decisions and use of income supports. Moreover, the analysis captures the outcomes of the first cohorts of participants following the launch of the projects; the outcomes of these first cohorts may not be representative of overall participant outcomes

Overall participant outcomes

Participants improved their labour market attachment after participating in SPF-funded interventions:

- they increased their earnings by $4,150 per year

- the proportion of participants earning less than $10,000 decreased by 7.4 percentage points while the proportion earning more than $30,000 increased by 6 percentage points

- they increased their incidence of employment by 4 percentage points

Outcomes by intervention type

Participant outcomes varied across different types of interventions:

- Skills Development Apprentices had the strongest increase in incidence of employment (+12 percentage points), while Targeted Wage Subsidies had the highest increase in earnings (+$10,494)

- of the 2 types of interventions taken by participants with weaker labour market attachment (Essential Skills Training and Job Creation Partnerships), only Essential Skills Training had stronger than average earnings outcomes

Outcomes by type of participant

Of the 3 participant types (active EI claimants, former EI claimants, and non-EI claimants), non-EI claimants, who accounted for 62% of participants, had the strongest outcomes; they increased their incidence of employment by 14 percentage points and their earnings by $7,089.

Outcomes by Indigenous group

Non-status First Nations, Inuit, and Métis participants had relatively strong outcomes, while those of status First Nations were much lower.Footnote 4 Prior to participation, status and non-status First Nations had similar levels of labour market attachment, but their post-participation outcomes differed:

- the earnings of non-status First Nations increased by $10,860 while those of status First Nations increase by $1,692

- the incidence of employment of non-status First Nations increased by 24 percentage points while that of status First Nations decreased by 0.5 percentage point

Outcomes by gender

Women had much weaker outcomes than men:

- women increased their earnings by $2,253 while that of men increased by $5,455

- the incidence of employment of women decreased by 0.5 percentage points while that of men increased by 7 percentage points

Outcomes by age

The earnings and incidence of employment of older participants decreased, while those of younger participants increased. Participants who were aged 30 or younger increased their earnings by $9,430 and increased their incidence of employment by 15 percentage points.

Outcomes by type of location

The outcomes of participants in rural and remote areas were positive but much lower than those of participants living in urban areas:Footnote 5

- participants in rural and remote areas increased their earnings by $2,667, compared to $6,110 for those living in urban areas

- the incidence of employment of participants in rural and remote areas decreased their 2 percentage points, while that of participants in urban areas increased by 12 percentage points

Broader project impacts

The evaluation identified several impacts that extended beyond program participants to their communities. Broadly, these included:

- supporting communities' economic, human resources, social and cultural development

- helping participants to access employment opportunities without having to move away from the community

- creating a sense of opportunity and possibility for community members, and

- strengthening families and households

Challenges and promising practices

The evaluation identified a variety of challenges that hindered project delivery and outcomes:

- project proposal and administrative processes can be difficult to manage for organizations that are not well-established or that have limited human resources capacity; providing support prior to calls for proposals and support throughout the duration of the project can be helpful

- many projects were forced to rethink their training or service delivery approach in response to COVID-19 related disruptions and response measures, such as lockdowns, social distancing, or closing communities to travel; the move to online delivery disadvantaged those who did not have access to highspeed internet, sufficient bandwidth, or computers

- staff turnover was a common challenge; for those in northern and remote communities, where it is often necessary to recruit individuals who do not live in the area, the loss of an employee or instructor can have severe impacts on project delivery and outcomes

- while working in partnership allows many projects to achieve positive outcomes, when partnerships do not proceed as planned or dissolve, the impacts on project delivery and outcomes can be severe; for agreement holders in rural and remote areas where there are fewer partnership opportunities, finding new partners can be challenging

The evaluation also identified a number of promising practices:

- the most common response to COVID-19 related disruptions was to move service delivery and training online; while this approach was not appropriate for all context and types of interventions, it provided many projects with the opportunity to reach more participantsFootnote 6

- in some cases, agreement holders were able to provide internet access and computers to participants

- a common thread among projects that had positive outcomes working with multi-barriered participants was the provisions of ongoing support throughout their path to employment; the agreement holders leading these projects emphasised that paths to employment are often not linear and that participants may need help to overcome a broad range of barriers

Performance measurement and data assessment

The program follows the best practice of collecting information at the individual level in a manner that enables the integration of program data with other administrative data sources and, potentially, with survey data. This approach supports the validation of short and medium-term post-participation employment outcomes while mitigating the administrative burden on agreement holders.

Agreement holders' ability to collect and report data were, at time, hindered by pandemic related disruptions, such as office closures. Despite these challenges, collected administrative data was found to be of sufficient quality and integrity to support the creation of participant profiles and post-participation labour market outcome analysis. Moreover, the data is of sufficient quality and integrity to support incremental impact analysis based on a 5-year post-participation period when the required taxation data becomes available in the 2027 to 2028 fiscal year.

Observations

The evaluation issues 4 observations that may benefit future SPF evaluations, call for proposals, and ongoing program implementation. These observations take into consideration that an SPF call for proposal was concluded in 2022 and that this limits ESDC's ability to make changes to program design.

Observation 1: For SPF projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals, it will be possible to carry out incremental impact analyses based on a 5-year post-participation period when the required taxation data becomes available in the 2027 to 2028 fiscal year.

Observation 2: Key informant interviews, the case studies, and previous engagement exercises with Indigenous partners identified challenges relating to SPF administrative processes for funding applicants that are not well established or that have limited human resources capacity. In particular, agreement holders noted that the investment of time and effort required to submit a competitive proposal can present a considerable challenge for smaller organizations.

Program officials noted that providing support prior to release of call for proposals can help to alleviate these challenges. It may also be relevant to explore additional options to simplify or facilitate the proposal submission process.

Observation 3: The post-participation outcome analysis of incidence of employment and employment earnings for different participant subgroups found that status First Nations and women benefited less from the interventions they received than other Indigenous groups and men. In general, participants with weaker pre-participation labour market attachment had stronger outcomes relative to participants who had stronger pre-participation labour market attachment. The outcomes of status First Nations and women did not follow this pattern; both had weaker pre-participation labour market attachment and weaker post-participation outcome relative to other Indigenous groups and men.

With respect to women, from a GBA+ perspective, it may be relevant to consider that few projects were designed specifically to support the labour market integration of women. Moreover, most of the projects were in male dominated fields and sectors, such as resource extraction related trades. Projects that included training in fields where women are well represented and that aligned with identified needs in Indigenous communities, such as nursing, education, and early childhood education attracted more women.

In future SPF calls for proposals, it may be relevant to explore options to solicit projects that are specifically designed to improve the labour market outcomes of women and status First Nations.

Observation 4: The average cost per participant was within the range expected for these types of programs. Evaluation found significant variation in the average cost per participants across projects. This variation reflects, in part, the higher costs associated with delivering programs in northern, rural, and remote areas, and with serving individuals facing persistent barriers to employment who may require multiple interventions. Nevertheless, ESDC may wish to closely examine projects with relatively high average cost per participants with a view to ensure that projects approved support the greatest number of Indigenous workers or jobseekers and represent the most effective avenue to provide employment support and services.

Recommendations

Northern and remote agreement holders and projects

The data assessment and document review identified contextual challenges and vulnerabilities relating to the organizational capacity of agreement holders located in northern and remote regions and to the limited partnership opportunities present in northern and remote areas.

Recommendation 1: ESDC is encouraged to explore options and take actions to offer further support to SPF agreement holders in rural and remote areas through each stage of the projects.

Data collection and performance measurement

The program is following the best practice of collecting individual-level data. The data collected and reported for projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals was of good quality and integrity overall. The document review and the literature review, which included reports summarising Indigenous partner engagement findings, found that the data collection and reporting requirements continue to be challenging for some agreement holders.

Moreover, some projects reported on the cash and in-kind contributions they received from their project partners throughout the project. Some also reported on their experience of working with their partners, including the challenges and benefits. This information, particularly when collected across all projects, can be valuable for program and project design and delivery, program management, program evaluation, and performance measurement.

Recommendation 2: ESDC is encouraged to explore options and take actions to:

- continue to prioritize data integrity, including validating data uploads, and providing support to projects experiencing data collection and reporting challenges; and

- collect consistent partner contribution data across all projects

Management Response and Action Plan

Overall Management Response

Employment and Social Development Canada's Skills and Employment Branch (SEB) and Program Operations Branch (POB) would like to thank the Evaluation Directorate and the Skills and Partnership Fund project recipients and their project partners who participated in the case studies included in the evaluation.

The evaluation findings are generally positive, despite many projects being impacted by the pandemic. The evaluation shows that the Skills and Partnership Fund is helping participants improve their connection to the labour market and is supporting Indigenous communities in benefiting from new economic opportunities. This fund addresses the educational, employment, and financial needs of Indigenous People, aligns with key government priorities related to labour market development and economic reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, and has been designed with input from Indigenous partners. The evaluation also found that participants improved their labour market attachment after taking part in Skills and Partnership Fund interventions, leading to increased employment rates and earnings.

The evaluation also identified several important holistic impacts that extended beyond program participants to their communities, such as:

- supporting communities' economic, human resources, social, and cultural development

- helping participants to access employment opportunities without having to move away from their community

- strengthening families and households

These findings illustrate how the Skills and Partnership Fund supported the labour market integration of Indigenous Peoples by addressing persistent economic and systemic barriers, contributing to the Department's objectives of facilitating and promoting labour market inclusion. The findings also highlight how the Skills and Partnership Fund supports the Government of Canada's commitments to advance Reconciliation and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDA) and the Inuit Nunangat Policy.

The evaluation provided valuable insights into the challenges that affected project delivery and outcomes, as well as successful practices. For instance, many projects had to adjust their training or service delivery due to disruptions caused by COVID-19, such as lockdowns, social distancing, and restricted travel. Moving to online delivery posed challenges for those lacking high-speed internet, sufficient bandwidth, or computers.

However, it did allow some projects to reach more participants, and in certain cases, agreement holders provided internet access and computers to participants. ESDC played a crucial role in helping organizations overcome pandemic-related setbacks by allowing for a 1-year extension of project completion without additional funding, recognizing the impact of the pandemic on training delivery and participant engagement. Nonetheless, it's important to acknowledge that the pandemic may have hindered the achievement of all anticipated outcomes. Regarding successful practices, it is worth noting that projects with positive outcomes for multi-barrier participants consistently provided ongoing support throughout their employment journey. This underscores the need for flexible support to address various obstacles and achieve positive outcomes.

Since the 2016 Call for Proposals, an extensive engagement process was conducted from January to July 2021 to inform the future of the Skills and Partnership Fund (SPF). Nearly 200 organizations, including over 100 Indigenous organizations, participated. This engagement guided the identification of priority sectors for the 2022 Call for Proposals, which encompassed a broader range of sectors compared to 2016. These sectors include the Indigenous Public Sector, Green Economy, Information and Communications Technology, Infrastructure, and Blue Economy. Additional work is ongoing to support the renewal of the SPF program, considering the evaluation findings and recommendations. As part of this initiative, the Department will enhance the proposal process and facilitate regional Indigenous investment and priority setting. This effort aims to bring together relevant partners, including Indigenous organizations, governmental funding partners, Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program service providers, and industry representatives, to collaboratively identify and respond to economic opportunities.

Recommendation 1

The program is encouraged to explore options and take actions to offer further support to SPF agreement holders in rural and remote areas through each stage of the projects.

Management Response

Management agrees with this recommendation. Employment and Social Development Canada recognizes that some organizations, particularly in more rural and remote communities, may have additional barriers to applying for funding through Call for Proposals (CFP) processes and in implementing projects. The program and officials will continue to explore how to better support potential project applicants and recipients throughout the project life cycle as part of the ongoing SPF renewal process.

Management Action Plan 1.1.

The Department will engage agreement holders in rural and remote areas to confirm the challenges they are facing and identify how to support them throughout the project life cycle.

Planned completion date: September 2025

Action status: Yet to commence

Accountable lead: Director General, Social Programs Directorate Program Operations Branch

Management Action Plan 1.2.

Streamline the proposal process to increase responsiveness to emerging economic opportunities identified by Indigenous organizations.

Planned completion date: September 2025

Action status: Yet to commence

Accountable lead: Director General, Indigenous Affairs Directorate Skills and Employment Branch

Management Action Plan 1.3.

Establish Regional Investment Coordination Tables to engage Indigenous governments, other funders, and the private sector in priority setting and project identification.

Planned completion date: September 2025 (to be implemented for next intake in 2027)

Action status: In progress

Accountable lead: Director General, Indigenous Affairs Directorate Skills and Employment Branch

Recommendation 2

The program is encouraged to explore options and take actions to:

Continue to prioritize data integrity, including validating data uploads, and providing support to projects experiencing data collection and reporting challenges; and

Collect consistent partner contribution data across all projects.

Management Response

Management agrees with this recommendation. Employment and Social Development Canada is committed to collecting and maintaining quality program data to support practical outcomes analysis for program participants. The report indicates that the program is following the best practice of collecting individual-level data and that the data collected was deemed of good quality and integrity overall. The program intends to continue to ensure data integrity and will seek to work proactively with organizations experiencing data collection and reporting challenges.

Management Action Plan 2.1.

Conduct a comprehensive review of data provided by current SPF project recipients to identify areas needing additional support.

Planned completion date: September 2025

Action status: Yet to commence

Accountable lead: Director General, Social Programs Directorate Program Operations Branch

Management Action Plan 2.2.

Organize regional training sessions to enhance the technical capacity of project recipients and Service Canada officers.

Planned completion date: December 2025

Action status: In progress

Accountable lead: Director General, Social Programs Directorate Program Operations Branch

Management Action Plan 2.3.

Develop a new performance measurement strategy with Indigenous partners to reflect the impacts of partnerships in achieving broader program objectives.

Planned completion date: March 2027 (For next intake in 2027)

Action status: Yet to commence

Accountable lead: Director General, Indigenous Affairs Directorate Skills and Employment Branch

Introduction

The present evaluation report builds on and complements the findings from previous evaluations of the Skills and Partnership Fund (SPF). The evaluation was conducted in compliance with the Federal Administrative Act and the Policy on Results.

The evaluation focuses on projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals and focuses on the 5 fiscal years between April 2017 and March 2022.Footnote 7

The evaluation's qualitative lines of evidence complement the incremental impact analysis presented in the 2020 evaluation. The key informant interviews with Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) officials, SPF agreement holders, and project partners along with 5 case studies, a literature review, and a document review of 52 SPF projects provide contextual insight into the SPF's design and delivery. In particular, the evaluation seeks to clarify the contribution of project partnerships to participants' labour market outcomes.

The report includes a quantitative analysis using linked administrative data for participants who began an SPF intervention in 2017 and 2018. The analysis provides the socio-demographic profile of participants who began an intervention during that period and findings on their post-participation labour market outcomes.

The Skills and Partnership Fund

Program description

The SPF was launched in 2010 alongside the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy, the predecessor of the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training (ISET) program. It is a project-based program that funds partnerships led by Indigenous organizations to increase the labour market participation of Indigenous Peoples.

The SPF complements the ISET program, which funds and supports a network of Indigenous service providers across Canada. The ISET Program provides Indigenous individuals with opportunities to develop and improve their skills and attain employment via a full suite of measures. Complementing the on-going activities of these service providers, the SPF funds short-term projects to connect Indigenous individuals to job opportunities by training participants and working in partnership with employers to meet their existing or anticipated labour needs.

The 2016 call for proposals included 2 funding streams: Innovation and Training to Employment.

The Innovation stream funded projects that aimed to test innovative approaches to enhance the employability of Indigenous individuals by addressing a broad range of employment barriers within Indigenous communities, such as lower educational attainment, homelessness, and addictions.

The Training-to-Employment stream funded projects that aimed to enhance participants' skills and access to employment through the provision of targeted training to fill in-demand jobs. Preference was given to projects that aimed to help at least 50 participants to secure long-term employment and projects that secured at least 50% of their total project resources from partners.Footnote 8

Indigenous agreement holders could develop partnerships with a range of educational, non-profit, private and public sector partners to provide skills training to improve the labour market outcomes of Indigenous participants.Footnote 9

Projects could support a broad range of activities from targeted training to help Indigenous individuals to fill existing or emerging job opportunities, to piloting new approaches to community-based work readiness and skills training. The interventions provided through the projects could range from light-touch job search activities to intensive pre-employment development with wraparound supports, to academic skills upgrading. More detailed information on intervention types is provided in Appendix A.

The SPF agreement holders were expected to leverage funding and in-kind resources from their partners in order to maximise the program's investments.

Program funding

In the 5 fiscal years between April 2016 and March 2021, the total expenditures of the program were approximately $224.5 million. Table 1 provides an overview of the annual and total expenditures by province and territory.

To give agreement holders more flexibility to respond to COVID-19 related disruptions, 42 of the 52 projects funded under the 2016 call for proposals were extended into the 2021 to 2022 fiscal year with no additional funding. Accordingly, while some projects ended in March 2022, funding ended in the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year.

| Province/territory | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | $3.4 | $12.8 | $20.6 | $18.4 | $10.6 | $65.8 |

| British Columbia | $1.3 | $3.6 | $7.8 | $10.1 | $8.4 | $31.2 |

| Northwest Territories | $1.1 | $3.3 | $8.1 | $8.1 | $4.5 | $25.1 |

| Saskatchewan | $1.9 | $3.7 | $4.0 | $4.1 | $4.1 | $17.8 |

| Quebec | $1.5 | $1.7 | $4.1 | $3.1 | $4.3 | $14.7 |

| Newfoundland | $1.4 | $3.9 | $2.8 | $2.7 | $3.4 | $14.2 |

| Alberta | $1.3 | $2.1 | $2.8 | $3.1 | $2.8 | $12.1 |

| Nunavut | $1.6 | $2.1 | $2.5 | $3.4 | $2.2 | $11.8 |

| Manitoba | $0.0 | $1.0 | $2.9 | $4.0 | $2.4 | $10.3 |

| Yukon | $0.4 | $1.5 | $1.9 | $2.0 | $1.9 | $7.7 |

| New Brunswick | $1.2 | $1.5 | $0.8 | $0.8 | $0.8 | $5.1 |

| Nova Scotia | $1.2 | $0.0 | $0.8 | $1.1 | $1.4 | $4.5 |

| Prince Edward Island | n/a | $0.6 | $0.9 | $1.0 | $1.2 | $3.7 |

| National Capital Region | $0.0 | $0.2 | $0.3 | n/a | n/a | $0.5 |

| Total | $16.3 | $38.0 | $60.3 | $61.9 | $48.0 | $224.5 |

- * The figures in this table have been rounded to the nearest decimal point meaning that the totals may not be exact.

Monitoring and reporting

SPF agreement holders are required to report on their project's activities and results on a quarterly basis. The specific data elements to be collected and shared are specified in the projects' funding agreements. These include data relating to the socio-demographic characteristics of participants, the interventions provided, and post-participation outcomes. In addition to this quarterly reporting, agreement holders are expected to submit a final report summarising the project's achieved results and progress toward targeted outcomes.

ESDC uses the information provided to track, assess and report on the program's outcomes and performance. Appendix B provides further details on the SPF's logic model and key performance indicators.

Evaluation approach

Evaluation objectives and scope

This evaluation focuses on SPF projects stemming from the 2016 call for proposals and covers the 5 fiscal years from April 2017 to March 2022. It is designed to build on and complement the findings from previous evaluations of project-based funding delivered by Indigenous organizations.

Specifically, the evaluation seeks to:

- provide timely information on challenges, opportunities and best practices relating to program design and delivery

- describe how the SPF is meeting the needs of individuals and communities and clarify the contribution of project partnerships to participants' labour market outcomes

- contextualise findings relating to program performance and provide insight into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the projects and their participants

- assess the data being collected and identify participants' labour market outcomes

Overall, the evaluation aims to help inform future cycles of program and policy development, and to support the evolution of the programs' performance measurement strategy and data collection.

Evaluation issues and questions

The evaluation addresses issues relating to program relevance, design and delivery, impact, reporting and data collection. Specifically, the evaluation addresses the following questions:

- To what extent and how is the SPF meeting a need (such as the current economic reality and unique needs of Indigenous individuals and communities)?

- To what extent and how is the SPF facilitating partnerships and collaboration among Indigenous organizations and other stakeholders (such as federal-provincial/territorial governments, industry, training institutions, and community organizations)?

- How and to what extent are these partnerships contributing to the labour market integration of Indigenous individuals?

- What are the challenges and opportunities affecting the SPF's capacity to achieve its objectives and expected results?

- How can the administration of the program and service delivery be improved?

- Are the Programs' performance measurement tools collecting and utilizing sufficient, valid and reliable data that support ongoing results reporting and decision-making?

Evaluation methods

The evaluation draws from multiple lines of qualitative and quantitative evidence, including a literature review, a document review, key informant interviews, case studies, administrative data analysis and assessment, and labour market outcome analysis. Where feasible and relevant, data from multiple lines of evidence are triangulated to validate and deepen evaluation findings.

Where possible, given the data and methodological limitations, a Gender-Based Analysis plus lens is applied.

Lines of evidence

Literature review

A literature review synthesises findings from relevant literature, program Indigenous partner engagement reports, and previous evaluations on the labour market context of Indigenous Peoples. The review provides an overview of Indigenous Peoples' educational attainment, employment and unemployment rates, and economies. It also includes a summary of labour market barriers and challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples and communities.

Document review

A document review covering 52 projects funded as part of the 2016 call for proposals provides a thorough overview of the design and delivery, partnerships and funding, targeted outcomes, and reported results of SPF projects. Reviewed documents included funding agreements, close-out summary reports, final project reports, and other reports and evaluations provided by SPF agreement holders.

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews with ESDC program officials and SPF agreement holders provide insight into the SPF's design and delivery, administration, impacts on participants and communities, partnerships, and barriers to employment. The interviews also capture interviewees' knowledge and perspective relating to challenges, opportunities and lessons learned.

Thirty-seven key informant interviews were completed, including 15 with ESDC program officials, and 22 with SPF agreement holders and their project partners. Twelve (12) of the 37 interviews were completed as part of the case studies.

Case studies

Five (5) project-based case studies were conducted, including 4 from the Training-to-Employment stream and 1 from the Innovation stream. Case studies were located in the Western, Central and Atlantic provinces.

Each case study is based on multiple lines of evidence, including key informant interviews, a document review, administrative data analysis and participant labour market outcome analysis.

The case studies provide insight into the relevance of the program, project design and delivery, program administration, the nature of the partnerships and their contribution to capacity building and participant labour market outcomes. The case studies also provide insight relating to challenges, opportunities and areas for improvement, successes, lessons learned and promising practices.

Administrative data analysis

Administrative data covering all participants and interventions in 2017 and 2018 were used to:

- create socio-demographic participant profiles

- identify the labour market barriers being addressed by projects

- identify the number and types of interventions being provided

- assess action plan results reported by service providers

Labour market outcome analysis

Labour market outcome analysis was completed using administrative data from EI Part I (EI claim data) linked to T1 and T4 taxation files from the Canada Revenue Agency. The analysis focused on the 5,003 individuals who began an SPF-funded intervention in 2017 and 2018. Participants' labour market outcomes were observed over a 9 year period, including 5 years pre-participation, a 1 year participation period, and 3 years post-participation.Footnote 10

The outcome analysis provides descriptive statistics on participants' incidence of employment, average annual earning, and use of government income supports over time. Labour market outcomes were produced for 3 types of participants:

- active EI claimants are participants who started an SPF-funded intervention while collecting EI benefits

- former EI claimants are participants who started an SPF-funded intervention up to 5 years after they completed an EI claim

- non-EI claimants are participant who are neither active nor former EI claimants

Data assessment

The quality and integrity of SPF administrative data on projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals was assessed. The purpose of the assessment was to determine the extent to which it could be used to meet the programs' performance measurement and evaluation requirements.

Methodological strengths and limitations

Outcome analysis

The outcome analysis captures the post-participation outcomes of participants who began an SPF intervention in 2017 and 2018. These participants include the first cohorts of participants following the launch of the projects.Footnote 11,Footnote 12 The outcomes of the first participant cohorts may not be representative of overall participant outcomes.

Outcome analysis provides an assessment of changes in participants' labour market outcomes over time. However, outcome analysis does not use comparison groups to compare the outcomes of participants to those of similar non-participants. Accordingly, it does not measure to what extent changes in participants labour market outcomes can be attributed to the intervention they received.

Labour market outcomes are influenced by changes in the economy, inflation, and the labour market. Several contextual factors should be taken into account when interpreting participants' labour market outcomes. The post-program participation period overlaps with the COVID-19 pandemic and its disruptive impact on the labour market. Moreover, several temporary income support measures were introduced during the pandemic that may have influenced participants' use of income supports and employment related decisions. These measures included, but were not limited to:

- the Canada Emergency Response Benefit from March 2020 to September 2020

- the Canada Recovery Benefit from September 2020 to October 2021

Moreover, available administrative data does not include income supports provided by Indigenous Services Canada through the On-reserve Income Assistance Program.

Accordingly, outcomes relating to the use of EI, use of SA, and the proportion of participants' incomes from government income supports should be interpreted with caution.

To mitigate these limitations, a follow-up study on impacts should be undertaken for this cohort of projects when the data required becomes available.Footnote 13

Assessing partner contributions

Some, but not all, projects reported on the cash and in-kind contributions they received from their project partners, and some also reported on their experience of working with their partners. For these projects, the reported data enabled:

- the tracking of partner contributions

- the identification of reliable and committed partners, and

- the identification of challenges and benefits of working with partners

Because partner contribution data was not consistently available in the project reporting documents, it was not possible to confirm the full extent of partner contributions across all projects.

Key informant interviews and case studies

The evaluation took place 1 to 4 years after the end of projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals. During this interim, agreement holder and project partner staff who had worked on SPF projects had begun working on other projects or had left the organization. This increased the challenge of scheduling interviews with SPF agreement holder staff who recalled the projects in detail. As a result, fewer interviews were completed than originally planned.

Engaging the partners of SPF agreement holders in evaluation activities proved to be challenging. While agreement holders are expected to participate in evaluation activities, project partners are not and have little incentive to do so. As a result, most of the key informant interviews conducted were with agreement holders, meaning that the perspectives of project partners are less well represented.

While the case studies provide valuable insight, they are not representative of the projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals. Overall, they include projects that:

- targeted participants who were further along in the employment integration continuum

- had private sector partners and received a large share of their project resources from partners

- had lower costs per participants, and

- had stronger employment outcomes

More information on the characteristic of the 5 case study projects and on how these compare to the average across the 52 SPF projects are provided in Appendix C.

Due to the challenges encountered in collecting qualitative data directly from agreement holders, the evaluation included more information collected by ESDC from agreement holders as part of program administration activities. In particular, the evaluation incorporated findings drawn from a review of the funding agreements and reporting documents of the 52 funded projects.

Socio-economic profile and labour market context of Indigenous Peoples in Canada

Approximately 1.81 million people self-identified as Indigenous in the 2021 Census, representing around 5% of the Canadian population. Of those who identified as Indigenous, approximately 1.35 million were of working age, that is 15 years of age or older.Footnote 14

Compared with non-Indigenous Canadians, the Indigenous population is younger, growing faster and more likely to live in rural or remote areas:Footnote 15

- the average age of Indigenous Peoples was 8.2 years younger than that of non-Indigenous Canadians

- the Indigenous population grew by 9.4% from 2016 to 2021, compared to 5.3% for the non-Indigenous Canadian population

- the proportion of the Canadian population that identified as Indigenous grew from 4.9% in 2016 to 5% in 2021

- about 60% of Indigenous Peoples live in rural areas, compared to about a third of non-Indigenous Canadians; approximately a quarter of Indigenous Peoples live in a remote area, compared to 3% of non-Indigenous Canadians

Indigenous Peoples face large and persistent economic and systemic barriers relative to non-Indigenous Canadians. On average, compared to non-Indigenous Canadians, they have lower educational attainment, employment rates, unemployment rates and income. Relative to non-Indigenous Canadians, Indigenous Peoples have inequitable access to health care, education, housing, and potable water.Footnote 16

Educational attainment and graduation rates

Between 2011 and 2021, post-secondary education completion among Indigenous Peoples aged between 25 to 64 grew slightly from 48.4% to 49.2%. As can be seen in Figure 1, the 2021 Census found a gap of 20 percentage points between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians' completion of bachelor's or graduate degrees. Indigenous Peoples are also less likely to have graduated from high school. Nine percent (9%) of non-Indigenous Canadians had not graduated from high school compared to 22% of Indigenous Peoples overall, and to 40% or more of First Nations who live on reserve and Inuit.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census, 2023.

- Note: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit categories include persons who identify as only 1 Indigenous group.

Text description: Figure 1

| Indigenous identity | Less than high school | High school | Post-secondary education - below bachelor's degree | Post-secondary Education - bachelor's degree or higher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Nation (on-reserve) | 40.0% | 26.1% | 27.9% | 6.1% |

| First Nation (off-reserve) | 20.6% | 29.6% | 36.4% | 13.3% |

| Métis | 14.8% | 28.9% | 40.6% | 15.7% |

| Inuit | 43.7% | 22.7% | 27.4% | 6.2% |

| Indigenous | 22.3% | 28.5% | 36.3% | 12.9% |

| Non-Indigenous | 9.3% | 22.7% | 34.2% | 33.8% |

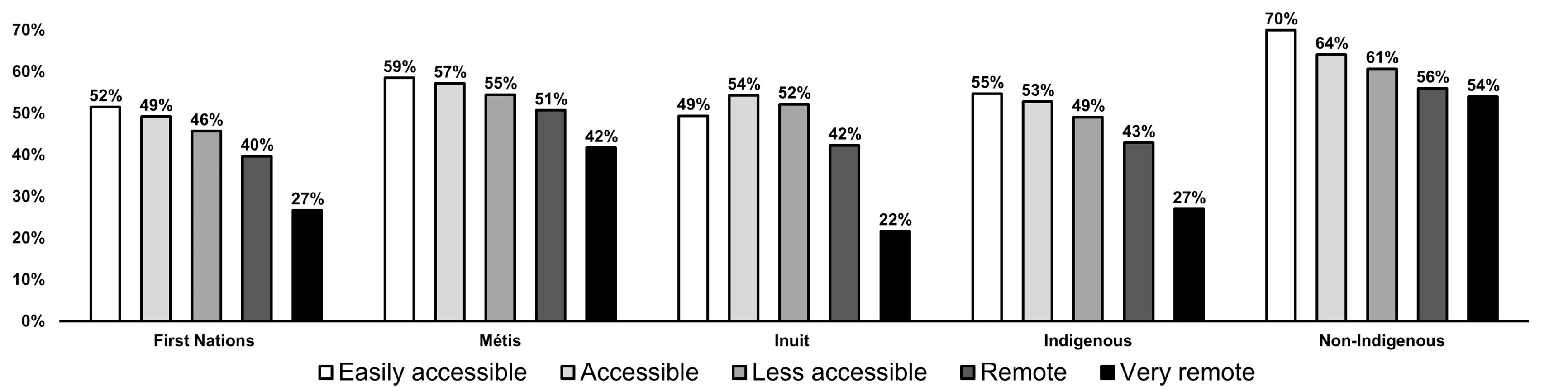

Nearly 60% of the Indigenous population lives in rural and remote areas. Geographic remoteness presents a barrier to educational attainment for Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 17,Footnote 18 As can be seen in Figure 2, the obtention of postsecondary qualifications decreases as remoteness increases. The correlation is more pronounced for Indigenous Peoples than for non-Indigenous Canadians.Footnote 19 Relative to individuals who live closer to post-secondary education institutions, the post-secondary completion rate of those who live in very remote areas is 16 percentage points (70% to 54%) lower for non-Indigenous Canadians compared to 22 percentage points (55% to 27%) lower for Indigenous Peoples.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census, 2023.

- Note: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit categories include persons who identify as only 1 Indigenous group.

Text description: Figure 2

| Indigenous identity | Easily accessible | Accessible | Less accessible | Remote | Very remote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Nations | 52% | 49% | 46% | 40% | 27% |

| Métis | 59% | 57% | 55% | 51% | 42% |

| Inuit | 49% | 54% | 52% | 42% | 22% |

| Indigenous | 55% | 53% | 49% | 43% | 27% |

| Non-Indigenous | 70% | 64% | 61% | 56% | 54% |

Employment ratesFootnote 20,Footnote 21

The 2021 Census found that Indigenous People between the ages of 25 and 64 had an employment rate of 61% compared to an employment rate of 74% for non-Indigenous Canadians. As presented in Table 2, employment rates rose with increasing levels of education. For those with a bachelor's degree or higher, there was no employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

| Level of education | First Nations* | Métis | Inuit | Indigenous Peoples | Non-Indigenous Canadians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No certificate, diploma or degree | 35% | 45% | 41% | 38% | 53% |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 54% | 65% | 61% | 58% | 66% |

| Post secondary certificate or diploma below bachelor level | 68% | 74% | 67% | 70% | 77% |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 81% | 85% | 85% | 83% | 83% |

| Population average | 57% | 69% | 55% | 61% | 74% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census, 2023.

- Note: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit categories include persons who identify as only 1 Indigenous group.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the employment rates of Indigenous Peoples were slower to recover than those of non-Indigenous Canadians.Footnote 22

Like low educational attainment, geographic remoteness presents a barrier to employment for Indigenous Peoples. As shown in Table 3, employment rates decrease as remoteness increases. The correlation is more pronounced for Indigenous Peoples than for non-Indigenous Canadians. Relative to individuals who live in easily accessible areas, the employment rate of those who live in very remote areas was 15 percentage points (65% to 50%) lower for Indigenous Peoples compared to 7 percentage points (75% to 68%) lower for non-Indigenous Canadians.

| Level of remoteness | First Nations* | Métis | Inuit | Indigenous Peoples | Non-Indigenous Canadians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easily accessible | 62% | 70% | 59% | 65% | 75% |

| Accessible | 56% | 69% | 61% | 62% | 74% |

| Less accessible | 55% | 68% | 65% | 60% | 72% |

| Remote | 53% | 67% | 61% | 57% | 71% |

| Very remote | 49% | 59% | 50% | 50% | 68% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census, 2023.

- Note: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit categories include persons who identify as only 1 Indigenous group.

Median annual incomeFootnote 23

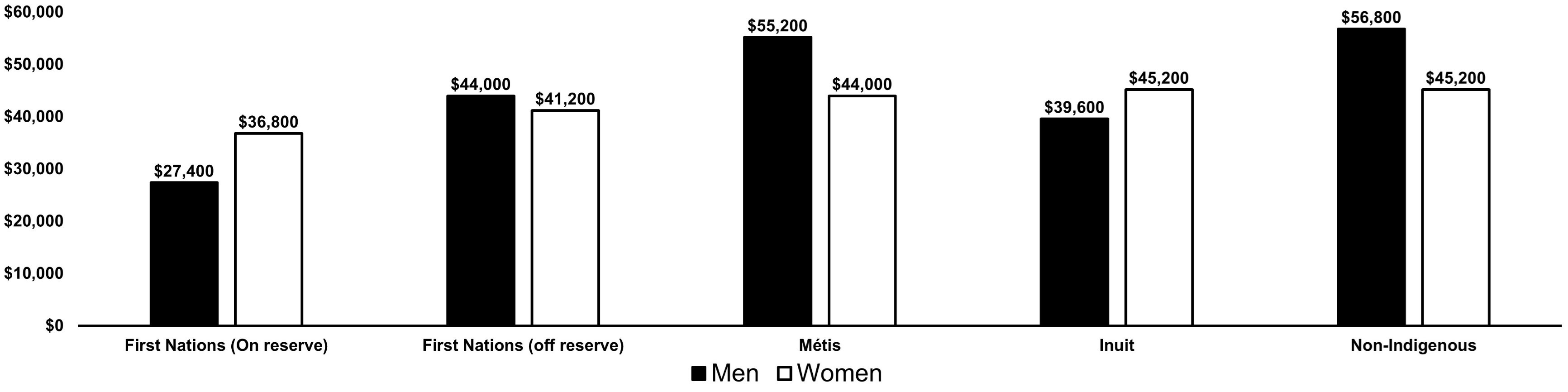

The 2021 Census found that Indigenous men earned less annually than non-Indigenous men. As shown in Figure 3, relative to non-Indigenous men who earned a median annual income of $56,800, the difference ranged from $29,400 less for First Nations men who live on reserve, to $1,600 less for Métis men.

The annual income differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women were less pronounced. These ranged from $0 for Inuit women, who had the same annual income as non-Indigenous women ($45,200) to $8,400 less for First Nations women who lived on reserve.

- Source: Indigenous Services Canada, An update on the socio-economic gaps between Indigenous Peoples and the non-Indigenous population in Canada: Highlights from the 2021 Census.

Text description: Figure 3

| Gender | First Nations (On reserve) | First Nations (off reserve) | Métis | Inuit | Non-Indigenous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | $27,400 | $44,000 | $55,200 | $39,600 | $56,800 |

| Women | $36,800 | $41,200 | $44,000 | $45,200 | $45,200 |

Unemployment ratesFootnote 24,Footnote 25

As shown in Table 4, the 2021 Census found that the unemployment rate of Indigenous Peoples (13%) was 5 percentage points higher than that of non-Indigenous Canadians (8%). The gap decreases as education increases. The unemployment rate of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who had a bachelor’s degree was the same (6%).

| Level of education | First Nations* | Métis | Inuit | Indigenous Peoples | Non-Indigenous Canadians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No certificate, diploma or degree | 23% | 20% | 23% | 22% | 15% |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 17% | 13% | 16% | 15% | 11% |

| Post secondary certificate or diploma below bachelor level | 13% | 10% | 14% | 11% | 8% |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 7% | 5% | 5% | 6% | 6% |

| Population average | 15% | 11% | 17% | 13% | 8% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census, 2023.

- *Note: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit categories include persons who identify as only 1 Indigenous group.

As presented in Table 5, the 2021 Census found that the unemployment rate of Indigenous People who lived in easily accessible areas was 12% compared to 16% for those who lived in very remote areas.

| Level of remoteness |

First Nations |

Métis |

Inuit |

Indigenous Peoples |

Non-Indigenous Canadians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Easily accessible |

13.3% |

10.7% |

15.3% |

12% |

8.5% |

Accessible |

15.7% |

10.7% |

14.9% |

13.2% |

7.9% |

Less accessible |

15.4% |

10.6% |

14.4% |

13.4% |

8.1% |

Remote |

16.3% |

11.5% |

14.2% |

14.8% |

9% |

Very remote |

15.6% |

16.3% |

18.8% |

16.4% |

11.7% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census, 2023.

- Note: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit categories include persons who identify as only 1 Indigenous group.

The Indigenous economy

The economic activities of Indigenous Peoples accounted for an estimated 2.2% of Canadian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2020. Public services, construction and finance, insurance and real-estate make up over 50% of total Indigenous GDP. Indigenous GDP is also more concentrated in Western provinces which accounts for over half the Indigenous GDP, compared to only 34% of the Canadian GDP.Footnote 26 It should be noted however that census data does not fully capture the economic activity in Indigenous communities.

In 2017, 85% of working age Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat participated in at least 1 traditional land-based activity or craft, such as hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering wild plants, and making clothing, footwear, handicrafts and artwork. Over a quarter of those reported they did so to earn money or supplement their income.Footnote 27 For First Nations living off reserve and Métis, almost 60% indicated they participated in traditional land-based activities and crafts.

Evaluation findings

Program relevance

The SPF addresses key government priorities, responds to demonstrable needs, and is designed in way that reflects lessons learned about project-based funding and input provided by Indigenous partners.Footnote 28

Labour market development and economic reconciliation

In addition to ongoing labour market development priorities, the federal government has identified several priorities intended to support economic reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 29 These include working with Indigenous communities and organizations to:

- support Indigenous Peoples to increase their educational attainment

- support Indigenous Peoples' participation in the economy, and

- increase the benefits that Indigenous communities derive from major projects in their territories

The SPF supports these government priorities by helping Indigenous individuals to:

- improve their educational attainment and labour market attachment, and

- build partnerships that enable them to benefit from emerging economic opportunities and major projects

Labour market development needs and barriers to employment

The program responds to the labour market needs of Indigenous Peoples and to some of the barriers to employment that they face.

The socio-economic profile section of this report identifies inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians with respect to their educational attainment, employment rates, unemployment rates, and average annual income. Moreover, while the educational and labour market outcomes of all Canadians worsen as remoteness from urban areas increases, the impact of remoteness is more pronounced among Indigenous Peoples.

With respect to barriers to employment, the most common barriers identified by participants were lack of work experience, low educational attainment, and lack of marketable skills.Footnote 30 Other common barriers included lack of transportation and living in a rural area with few job opportunities. For women in particular, lack of access to dependent care was a common barrier to employment.

The SPF responds directly to these needs and barriers by supporting Indigenous-led projects that:

- support participants in their efforts to increase their level of education and training

- support participants to increase their employability and work experience

- help connect participants to existing and emerging job opportunities and to increase their employment income

- help communities and Indigenous service providers to build and maintain working relationships with employers, and

- reach Indigenous individuals who live on-reserve, in rural areas, and in remote communities

Finally, the SPF seeks to respond to the needs of multi-barriered individuals by providing the flexibility to design programs and services that:

- respond to a broad range of barriers, such as access to childcare and transportation, resources to buy basic equipment, and access to mental health supports, and

- allow projects to support participants who are further from the labour market as they progress along the path to employment

Relevant and informed program design

In their complementarity, the SPF and the ISET Program reflect lessons learned from previous evaluations of ESDC labour market integration programs for Indigenous Peoples and input provided by Indigenous partners.

A previous evaluation of Indigenous labour market programs funded through ESDC yielded important lessons relating to project-based funding for employment programs:Footnote 31

- projects focusing on specific industrial developments, such as a particular mining project, yield stronger employment results than projects with a broader focus, such as the mining sector in general

- partnering with employers and tailoring training to their needs creates a training-to-employment path for project participants yielding stronger outcomes for participants and employers

- partnerships with greater employer engagement, particularly those including formal agreements for in-kind or cash contributions, yield stronger employment results, as employer partners are more invested in the outcomes

Engagement with Indigenous partners also yielded valuable insight relating to the design and delivery of labour market training programs for stronger, broader, and longer lasting impact:Footnote 32

- longer-term funding supports the maintenance and development of experienced service providers with knowledgeable staff who produce strong results

- stronger connections are needed between Indigenous service providers and potential employers in local industries to:

- better align training opportunities with in-demand skills and long-term employment opportunities

- help develop the local economy and help participants to stay in their communities with their families

- greater flexibility is needed for service providers to design programming to meet the complex needs of their people and communities, such as:

- pre-employment interventions to increase employability, such as life and essentials skills training

- wraparound services and individualised supports

- supports to complete and skills up-grading to move beyond entry-level positions

Overall, with ISET supporting a stable network of experienced service providers across the country, the SPF aims to respond to these lessons learned and insights by providing timely funding to develop strategic partnerships with employers for training-to-employment projects and to test flexible approaches to addressing complex issues through community-based service delivery.

Key informants interviewed as part of the evaluation added that the SPF is part of a broader ecosystem of programs aiming to improve the labour market integration of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. While these programs have similar objectives and offer similar types of interventions, they differ in their approach. Key informants specified that the SPF contributes to the broader effort by supporting the development and maintenance of cross-sectoral partnerships, including employers, training institutes, and post-secondary education institutions to take advantage of existing and emerging employment opportunities; these findings were further confirmed through the document review.

Program design and delivery

SPF agreement holders

Most of the projects were led by Indigenous bands, councils, and governments (42%), Indigenous led non-profit organizations (33%); 15% were led by Indigenous education institutes, and 10% were led by Friendship Centres.

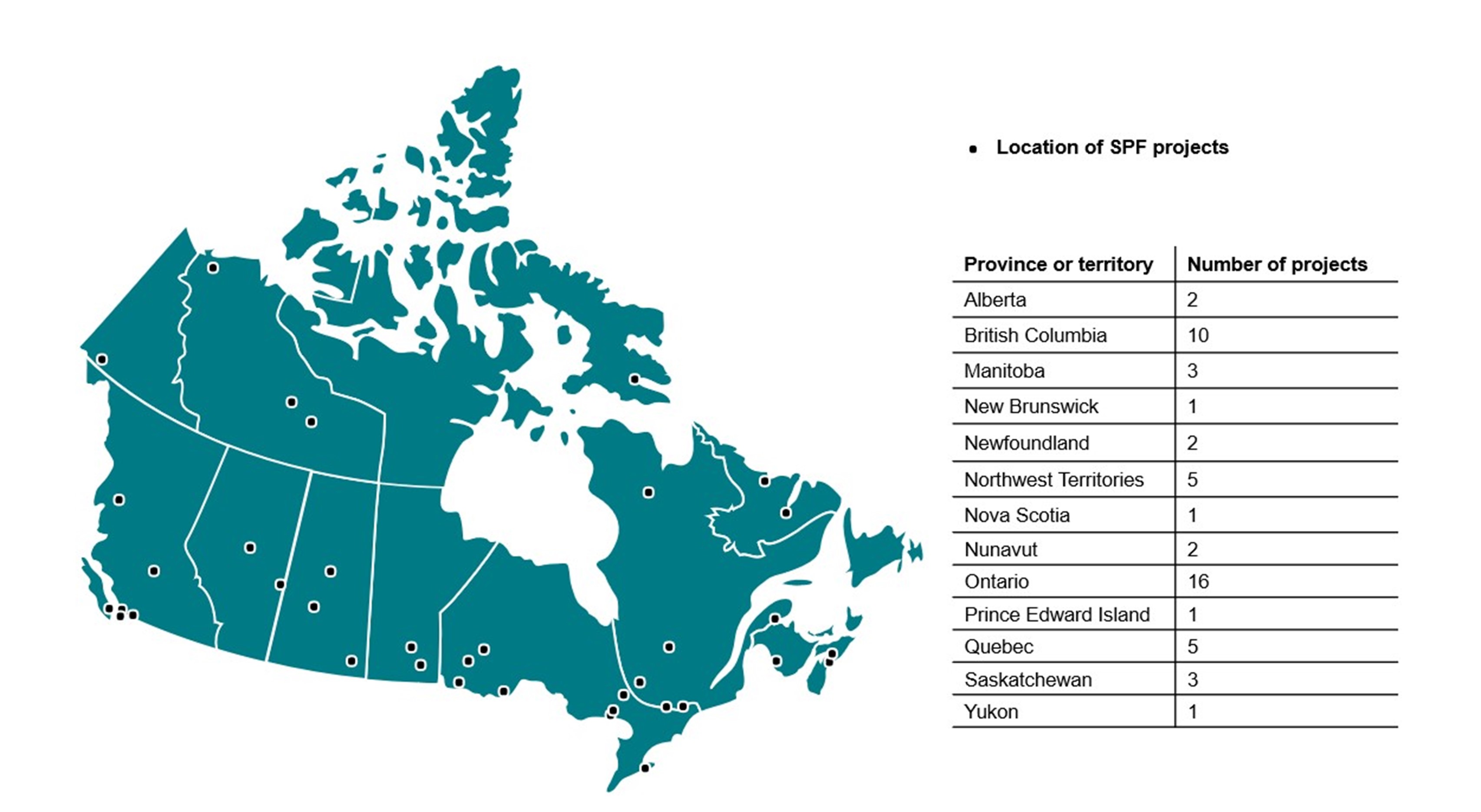

Agreement holders were located in each of the 13 provinces and territories. However, 70% were located in 4 provinces and territories: Ontario (31%), BC (19%), the Northwest Territories and Quebec (10% each).

Text description: Figure 4

Map of Canada showing the location of SPF projects and table showing the number of projects per province and territory.

| Province or territory | Number of projects |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 2 |

| British Columbia | 10 |

| Manitoba | 3 |

| New Brunswick | 1 |

| Newfoundland | 2 |

| Northwest Territories | 5 |

| Nova Scotia | 1 |

| Nunavut | 2 |

| Ontario | 16 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 |

| Quebec | 5 |

| Saskatchewan | 3 |

| Yukon | 1 |

SPF funding streams

Of the 52 projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals, 60% were funded through the Innovation Stream and 40% through the Training to Employment Stream.

Innovation stream

Projects in the Innovation stream generally aimed to support individuals who were further from the labour market and who were facing multiple intersecting barriers to employment. For the most part, these projects were not developing new program and service delivery approaches. However, most were experimenting with practices and approaches that were new to their organizations and communities in order to improve the labour market outcomes for their participants. In general, the stream supported experimentation and iterative service delivery improvement.

Training-to-Employment stream

Projects in the Training-to-Employment stream generally supported individuals who were somewhat more work-ready. In keeping with the stream description, projects funded through this stream generally focused on in-demand skills training and working with employers to connect participants to employment opportunities.

Scope and objectives

The objectives and intended outcomes of each project were identified in their funding agreements. While all were ultimately aimed at improving participants' labour market participation, most projects included progress along the pre-employment continuum as an immediate project outcome for a large portion of their participants.

Overall, the most common immediate outcomes sought by projects were:

- participants find employment (98%)

- participants complete occupational skills training (80%)

- participants reach the pre-employment outcome of increased employability (76%)

- participants complete pre-employment training (64%)

Populations targeted by SPF projects

Indigenous Peoples

SPF-funded interventions are intended for Indigenous Peoples, including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Most SPF projects (65%) were targeted toward a specific First Nation, Inuit, or Métis community or group of communities, while the rest were intended to serve more than 1 of the 3 Indigenous population groups. Overall, based on the documents reviewed:Footnote 33

- 81% of the projects aimed to serve First Nations individuals

- 21% of the projects aimed to serve Inuit individuals

- 15% of the projects aimed to serve Métis individuals

Location of targeted participants

SPF projects aimed to serve Indigenous individuals throughout Canada, both on and off reserve, and in urban, rural, and remote areas. Overall, based on the reviewed documents:Footnote 34

- 63% aimed to serve individuals who live on reserve or in an Inuit community

- 56% aimed to serve individuals who live in or near an urban area

- 46% aimed to serve individuals who live in rural areas that are not close to an urban areaFootnote 35

- 17% aimed to serve individuals who live in a remote community

Targeted population sub-groups

Each SPF project identified whether it had provisions aimed at increasing the participation of women and youth. They also identified what targets, if any, had been set with respect to the number of women and youth served. While fewer than 3 projects were intended exclusively for women or youth, most projects had provisions to increase the participation of 1 or both groups. Seventy-nine percent (79%) of projects had provisions for women, 77% for youth, and 71% for both women and youth.

Fewer than 3 projects expressly identified older adults or persons with disabilities as targeted participants.

Economic sectors targeted

SPF projects provided training aimed at helping participants to secure employment in a wide variety of sectors. The most common sectors were:

- trades (non-specific) (60%)

- construction (38%)

- mining (30%)

- hospitality and tourism (28%)

- healthcare (22%)

- carpentry (22%)

Programs and services provided

SPF projects provided a broad variety of services, ranging from light-touch employment assistance services to intensive pre-employment training and support to complete university degrees:

- 96% of projects provided interventions aiming to improve participants' general employability; for example:

- 69% provided essential skills training

- 62% provided pre-employment development interventions aimed at improving participants employability, and

- 60% provided various work experience programs

- 87% of projects provided various types of occupational skills training, including certificates, diplomas, and degrees from recognised post-secondary institutions, apprenticeships, and industry recognised certificates

- 63% of projects offered some type of employment assistance services, such as:

- employment counselling (52% of projects)

- career research and exploration (40% of projects), and

- job search supports (22% of projects)

- 23% of projects provided ongoing wrap-around supports for participants facing multiple barriers to employment

Many projects incorporated Indigenous approaches, methods, and practices into their training programs. Agreement holders noted that this practice increased participant engagement, created a supportive learning environment, and helped to support participants' wellbeing.

Average cost per participant

Contextual factors should be taken into account when considering the cost per participant of interventions. For the SPF, the document review found that projects with higher costs per participant were affected by the following factors:

- the higher cost of delivering labour market programs in rural, remote, and northern areas (compared to urban areas), and

- the higher cost of supporting individuals who face persistent barriers to employment, as they may require interventions over a longer period of time, broader and more intensive support, and may not have a linear path to employment

For all projects funded through the 2016 call for proposals, the anticipated average cost per participant prior to program delivery was $11,263. The actual cost per participant once the program had been delivered was $14,437.Footnote 36

Taking the contextual factors into account, the anticipated cost per participant was relatively low, and the actual cost per participant was within the range expected for these types of programs. It is expected that some projects will encounter unforeseen challenges that will increase their cost per participant. The impacts of the pandemic on participant numbers, project delivery, the labour market and the economy may also have influenced costs.

Evaluation found significant variation in the average cost per participants across projects. This variation reflects, in part, the higher costs associated with delivering programs in northern, rural, and remote areas, and with serving individuals facing persistent barriers to employment who may require multiple interventions. Nevertheless, ESDC may wish to closely examine projects with relatively high average cost per participants with a view to ensure that projects approved support the greatest number of Indigenous workers or jobseekers and represent the most effective avenue to provide employment support and services.

Partnerships, collaboration and labour market integration

According to key informants and project documents, the SPF supported the delivery of projects with long-established partners as well as with the development of new partnerships. Some of the most successful projects harnessed their relationships with existing partners to engage new partners.

Types of partners

SPF agreement holders worked with a variety of partners in the public, non-profit, and private sectors. The number of partners per project ranged from 1 to over 20. Overall:

- 71% of projects partnered with Indigenous bands, councils, and governments

- 62% of projects partnered with private sector firms, corporations, and businesses

- 56% of projects partnered with post-secondary education institutions

- 56% of projects partnered with Indigenous-led non-profit organizations

Nearly 60% of the projects that identified private sector partners worked with partners in the mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction sector.

Partner contributions

Partner contributions took many forms, including:

- supporting project design

- delivering training

- providing work placements

- commitments to hiring trained participants, and

- providing cash and in-kind resources

Funding agreements identified the planned sources of funding for each project, including the anticipated cash and in-kind resources to be provided by partnering organizations. Overall:

- 54% of the funding across all projects was to be provided by the SPF

- partners were to contribute 13% of project resources as cash contributions, amounting to over $50 million across all projects

- partners were to provide 33% of project resources as in-kind contributions, amounting to an estimated value of over $126 million across all projects

Funding and in-kind resources to be provided by partners ranged from 0% to 89% of total resources per project. A quarter (25%) of the projects were to receive at least 50% of their project's resources from their partners. Another quarter (25%) were to receive 25% to 49% of their project resources from their partners.

Although many partnerships evolved as planned, the document review reveals that some agreement holders experienced challenges in securing anticipated contributions from their partners. It was not possible to confirm the actual amount of cash and in-kind resources provided by partners, nor to confirm to what extent partners had honoured their initial commitments across all projects.Footnote 37

Benefits and challenges of working with partners

Benefits

The case studies, key informant interviews, and document review revealed numerous examples of successful partnerships. These led to many of the benefits associated with the partnership approach, namely:

- improving employer cultural awareness and willingness to work with Indigenous communities and service providers to meet their labour force needs

- building relationships between employers and Indigenous service providers and communities

- aligning training to prepare participants to meet the existing or upcoming labour force needs of employers

- enabling participants to move beyond entry level positions

- developing local opportunities thereby enabling participants to stay in their communities and with their families

- enabling communities to benefit from major projects on their territories or in other locations, and

- enabling projects holders to support individuals who face multiple barriers to employment

Two projects that exemplify successful partnerships were taken from the case study projects.

Case study example 1

A well-established agreement holder partnered with industrial training providers, trade certification bodies and employers. They leveraged their extensive network of industry partners to identify small and medium enterprises willing to provide work experience and on the job training, and to hire participants.

Unemployed and underemployed participants received occupational skills training and were then matched with employers so that they could complete mandatory on the job components of their training, apprenticeship, or certification process.

The organization recognises that participants often face multiple barriers. To be responsive to participant needs, the service provider maintains flexibility to support participants through setbacks and to change action plans to support participants growth in a way that is best suited to their needs, interests, and objectives. The organization commits to supporting participants as long as necessary to achieve a successful outcome.

By the end of the project, 499 participants were employed, which was 260 more than the targeted outcome.

Case study example 2

A well-established agreement holder saw an emerging opportunity as a major shipbuilding contract had been secured by a corporation operating in their region. The corporation had worked with the agreement holder before and enough confidence had been built that the partner chose to invest in the program.