Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2014/2015 Chapter II - 2. Assisting Canadians during unemployment: Employment Insurance regular benefits

2. Assisting Canadians during unemployment: Employment Insurance regular benefits

Employment Insurance (EI) regular benefits provide temporary financial assistance to workers who have lost their job for reasons outside their control, while they look for work or upgrade their skills, Footnote 31 provided that, in the previous 52 weeks, or since the start of their last claim (whichever is shorter), they paid EI premiums and have accumulated the required number of hours of insurable employment. In most cases, to qualify for regular benefits, individuals require between 420 and 700 hours of insurable employment, depending on the unemployment rate of the EI economic region in which they reside at the time of making their claim. This feature of the EI program is referred to as the Variable Entrance Requirement (VER).

However, workers who have recently entered the labour market for the first time (new entrants) and those who have limited or no work experience in the last two years (re-entrants) require 910 hours of insurable employment regardless of where they reside. These two groups are collectively known as new-entrants/re-entrants (NEREs).

The amount paid in EI regular benefits is driven by three key indicators: the number of claims, the duration of benefits, and the average weekly benefit rate (level of benefits). In general, an increase in one of these three indicators will have a positive impact on the total amount paid. In the section 2.1, the number of claims and amount paid will be discussed, while the duration and level of regular benefits will be discussed in sections 2.3 and 2.4. For the purpose of these sections, EI regular claims refer to claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

2.1 Employment Insurance regular claims and amount paid Footnote 32

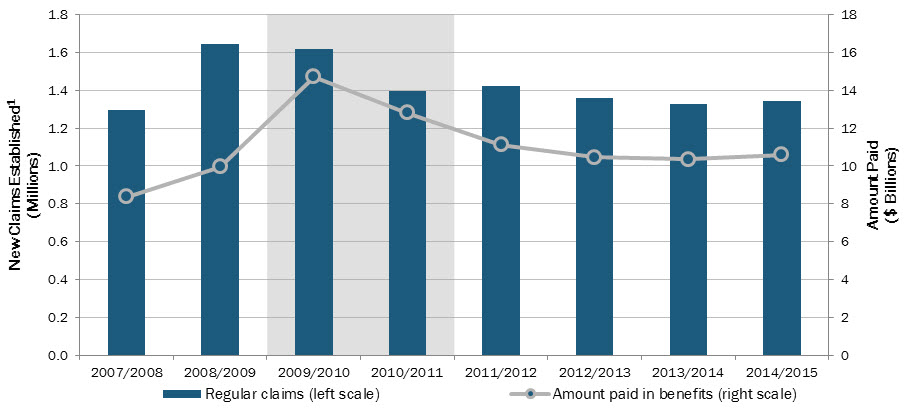

The number of regular claims established in 2014/2015 remained relatively stable at 1.34 million from 1.33 million in 2013/2014, representing a slight increase of 1.3%. Despite a downward trend since 2008/2009, the number of new EI regular claims remained 3.8% higher than the level (1.29 million) observed in 2007/2008, prior to the onset of the 2008 recession (see chart 8).

Show Data Table

| Regular Claims (Millions) | Amount Paid ($ Billions) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 1.3 | 8.4 |

| 2008/2009 | 1.6 | 10.0 |

| 2009/2010 | 1.6 | 14.7 |

| 2010/2011 | 1.4 | 12.8 |

| 2011/2012 | 1.4 | 11.1 |

| 2012/2013 | 1.4 | 10.5 |

| 2013/2014 | 1.3 | 10.4 |

| 2014/2015 | 1.3 | 10.6 |

- Note: Shaded area corresponds to a recessionary period for Canada's economy.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits were paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

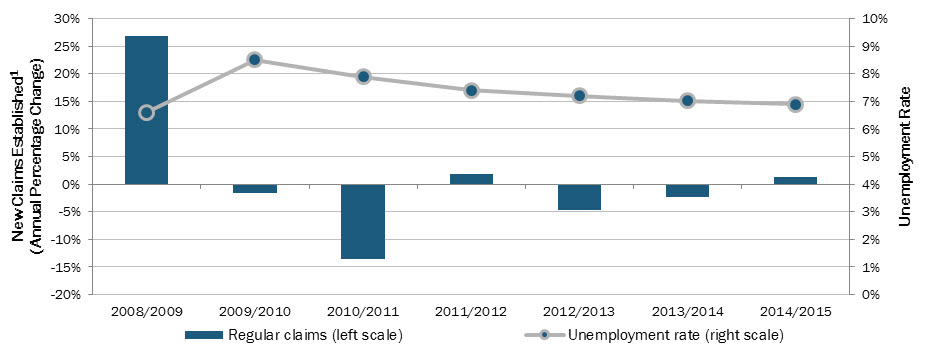

In addition, the unemployment rate attained a high of 8.5% in 2009/2010 and has since been decreasing, reaching 6.9% in 2014/2015 (see Chart 9). Generally, the number of EI regular claims tends to be sensitive to economic cycles and labour market conditions. Canadian economic activity fell in the Oil and Gas Extraction industry in the last quarter of 2014/2015, particularly in the Western provinces, following a sharp decline in the price of oil between June 2014 and January 2015. This ended the post-recession downward trend in the number of EI regular claims since 2008/2009 and began an upward trend.

Show Data Table

| New Regular Claims Established (Annual percentage change) |

Unemployment rate | |

|---|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 26.9% | 6.6% |

| 2009/2010 | -1.6% | 8.5% |

| 2010/2011 | -13.6% | 7.9% |

| 2011/2012 | 1.8% | 7.4% |

| 2012/2013 | -4.6% | 7.2% |

| 2013/2014 | -2.3% | 7.0% |

| 2014/2015 | 1.3% | 6.9% |

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data (for data on regular claims); and Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, CANSIM Table 282-0001 (for data on unemployment rate). ESDC data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Finally, as the number of EI regular claims stabilized, so did the amount of EI regular benefits paid to Canadians, which slightly increased to $10.6 billion in 2014/2015 from $10.4 billion in 2013/2014. This increase follows a four year downward trend in amount paid, decreasing since 2009/2010 when a high of $14.7 billion was reached. The amount paid in regular benefits is 26.6% higher than 2007/2008 levels, before the onset of the 2008 recession.

In 2014/2015, there was an average of 510,320 beneficiaries receiving EI regular benefits each month, a decrease of 1.5% from the average 518,080 regular beneficiaries in 2013/2014. The beneficiary count represents the number of EI claimants who received at least $1 of EI regular benefits during the reference period for the month (usually the week of the 15th day) and is affected by the inflow of new EI regular claimants and the outflow of EI regular claimants who have stopped receiving benefits, principally because they have exhausted their benefits entitlement or have returned to work.

Generally speaking, claims and beneficiaries tend to move together, except when there are changes in the average duration of benefits or a sudden, significant increase or decrease in new claims. When there is an economic shock, claim volumes will increase ahead of beneficiaries, due to the lag between when a new claim is received and when a benefit period is established and benefits are made payable. The beneficiary count will remain elevated after the volume of new claims have subsided as previous claims remain in pay, until benefits are exhausted or the claimants have returned to work.

2.1.1 Employment Insurance regular claims and amount paid, by province and territory, gender and age

As seen in Chart 10, while the number of new EI regular claims established remained relatively stable nationally (+1.3%), it fluctuated largely by province and territory. As such, while Alberta (+25.9%) and Saskatchewan (+15.0%) saw large increases in claims volume, the number of claims decreased noticeably in Ontario (-2.4%), as well as in Nunavut (-29.4%) and in Yukon (-6.9%). As indicated in section 2.1.2, changing economic conditions affecting the Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction industry in the Western provinces had a negative impact on the number of claims established in these regions. In addition, the increase in the number of EI claims in Alberta and Saskatchewan was observed for both men and women.

Show Data Table

| 2014/2015 New Regular Claims Established (Annual percentage change) |

|

|---|---|

| N.L. | 0.2% |

| P.E.I. | 3.2% |

| N.S. | 2.0% |

| N.B. | -0.7% |

| Que. | -0.1% |

| Ont. | -2.4% |

| Man. | 4.6% |

| Sask. | 15.0% |

| Alta. | 25.9% |

| B.C. | -1.3% |

| Y.T. | -6.9% |

| N.W.T. | 9.8% |

| Nvt. | -29.4% |

| Canada | 1.3% |

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

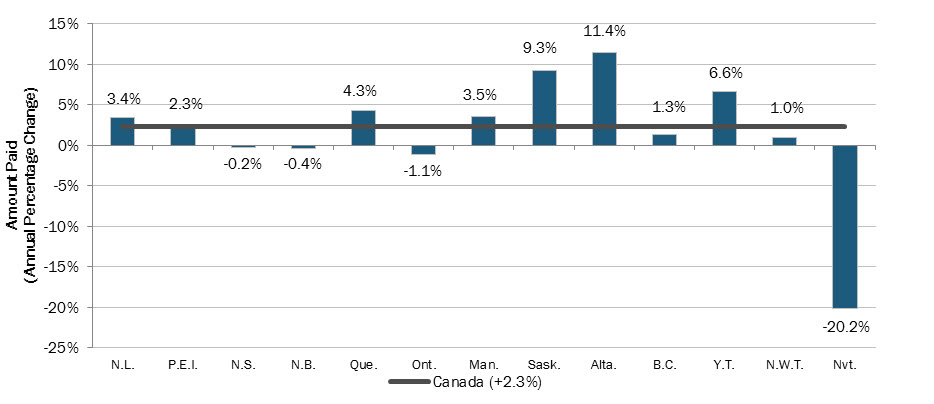

Similarly, the total amount of regular benefits paid also fluctuated significantly by province and territory (see Chart 11), with Alberta and Saskatchewan again seeing the largest increases from 2013/2014 to 2014/2015 at 11.4% and 9.3%, respectively, while Ontario and Nunavut decreased by 1.1% and 20.2%, in that order.

Show Data Table

| 2014/2015 Amount Paid (Annual percentage change) |

|

|---|---|

| N.L. | 3.4% |

| P.E.I. | 2.3% |

| N.S. | -0.2% |

| N.B. | -0.4% |

| Que. | 4.3% |

| Ont. | -1.1% |

| Man. | 3.5% |

| Sask. | 9.3% |

| Alta. | 11.4% |

| B.C. | 1.3% |

| Y.T. | 6.6% |

| N.W.T. | 1.0% |

| Nvt. | -20.2% |

| Canada | 2.3% |

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administatrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Table 8 depicts the percentage change in the number of new EI regular claims and amount paid by gender from 2013/2014 to 2014/2015. As can be seen, the number of regular EI claims established increased nationally for men (+2.3%) while it decreased slightly for women (-0.3%). Percentage changes by gender show big fluctuations by province: while the number of EI regular claims made by men increased by 35.6% in Alberta, it decreased by 7.2% in the Territories. Likewise, the number of EI regular claims established by women increased by 11.9% in Alberta while it decreased by 3.1% in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

| Province and Territory | New Claims Established1

(Annual Percentage Change) |

Amount Paid (Annual Percentage Change) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | Total | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.1% | -1.2% | 0.2% | 2.8% | 4.7% | 3.4% |

| Prince Edward Island | 4.5% | 1.3% | 3.2% | 2.5% | 1.8% | 2.2% |

| Nova Scotia | 5.1% | -3.1% | 2.0% | 0.9% | -2.7% | -0.2% |

| New Brunswick | 0.6% | -3.1% | -0.7% | 0.2% | -1.8% | -0.4% |

| Quebec | 0.2% | -0.6% | -0.1% | 5.1% | 2.4% | 4.3% |

| Ontario | -3.2% | -1.3% | -2.4% | -2.0% | 0.3% | -1.1% |

| Manitoba | 7.0% | 0.8% | 4.6% | 5.4% | -0.5% | 3.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 21.1% | 5.4% | 15.0% | 11.0% | 5.3% | 9.3% |

| Alberta | 35.6% | 11.9% | 25.9% | 14.4% | 6.1% | 11.4% |

| British Columbia | -0.3% | -2.4% | -1.3% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.4% |

| Yukon | -4.7% | -11.0% | -6.9% | 0.6% | 18.5% | 6.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 1.9% | 27.7% | 9.8% | -3.0% | 10.6% | 1.2% |

| Nunavut | -30.4% | -27.6% | -29.4% | -15.3% | -31.2% | -20.4% |

| Canada | 2.3% | -0.3% | 1.3% | 2.7% | 1.5% | 2.3% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Table 8 also shows that gender fluctuations by province and territory usually follow the same trend: the number of EI regular claims increases or decreases for both genders in a specific area. This is not the case however for the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Quebec, where while the number of claims increased for men, it decreased for women.

Similar to new claims established, the amount paid moved in the same direction for both men and women in 8 out of the 13 provinces and territories. The exceptions to this were the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Manitoba, as well as the Northwest Territories. Specifically, the Northwest Territories saw a gap of 13.6%, where amount paid to men modestly decreased by 3.0% but amount paid to women increased by 10.6%. Even more significant was Yukon, which witnessed the largest gender gap in the year-over-year percentage change at nearly 18%, although both men and women observed increases in amount paid.

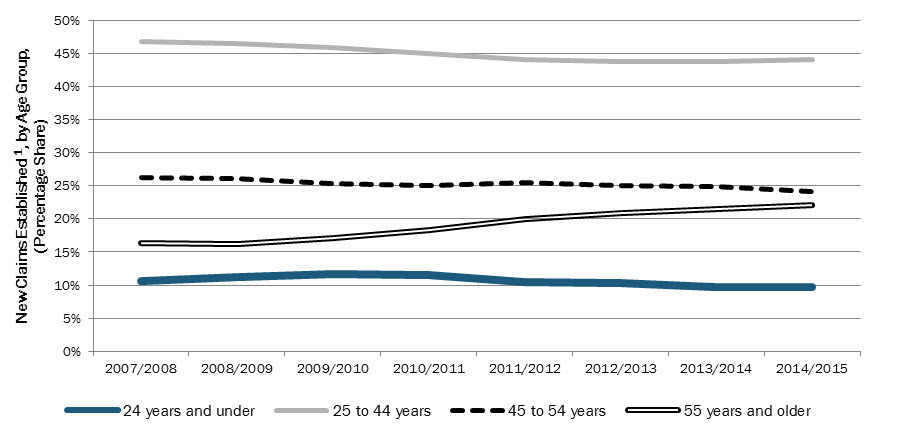

Chart 12 shows that the proportion of claims made by claimants aged between 25 and 44 years old has been decreasing slightly since 2007/2008. On the other hand, claims made by older workers (55 years and older) are trending upward from 16% in 2007/2008 to 22% in 2014/2015.

Show Data Table

| New Regular Claims Established (percentage share) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

| 24 years and under | 11% | 11% | 12% | 12% | 11% | 10% | 10% | 10% |

| 25 to 44 years | 47% | 47% | 46% | 45% | 44% | 44% | 44% | 44% |

| 45 to 54 years | 26% | 26% | 25% | 25% | 26% | 25% | 25% | 24% |

| 55 years and older | 16% | 16% | 17% | 18% | 20% | 21% | 22% | 22% |

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

There is a parallel movement among the age groups for the amount paid in regular benefits (see Chart 13). Specifically, the share of the total amount paid to those aged 55 years and older has been increasing since 2009/2010, when it had remained steady at around 17% for several years. In 2014/2015 the amount paid to this age group increased to 23%. In addition, those aged 25 to 44 have seen the largest decrease, falling from 48% in 2007/2008 to 43% in 2014/2015. The other age groups (those aged 24 and under, and 45 to 55 years) have seen very modest decline in their share of total amount paid.

Show Data Table

| Amount Paid (percentage share) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

| 24 years and under |

10% | 10% | 11% | 10% | 10% | 10% | 9% | 9% |

| 25 to 44 years |

48% | 47% | 47% | 44% | 44% | 44% | 44% | 43% |

| 45 to 54 years |

25% | 26% | 26% | 26% | 26% | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| 55 years and older |

17% | 17% | 17% | 20% | 21% | 22% | 22% | 23% |

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data

These trends may be attributed to the aging population. There is a positive correlation between the increase in the number of EI regular claims and amount paid among older workers and the increase in their share of the Canadian labour force. Older workers accounted for 19% of the labour force in 2014/2015, an increase from 15% in 2007/2008.

2.1.2 Employment Insurance Regular claims and amount paid, by industry and Employment Insurance claimant category

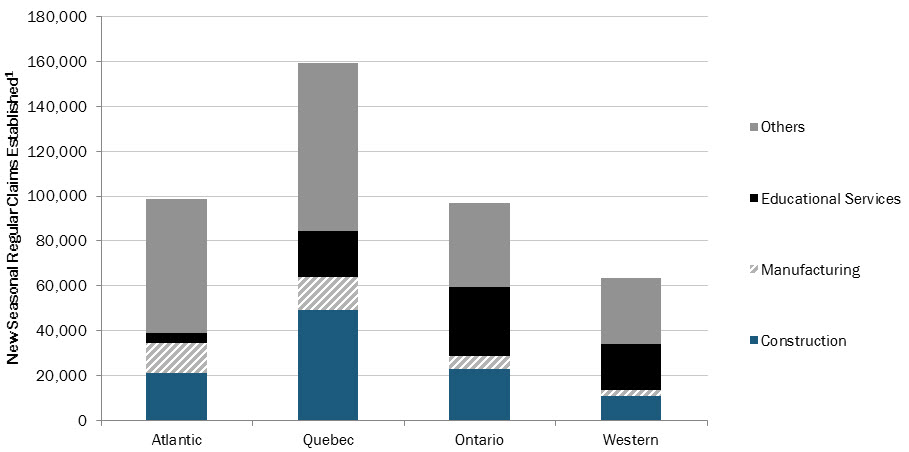

From 2013/2014 to 2014/2015, while the total number of EI regular claims remained stable, the number of EI regular claims in the Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction industry increased by 18.5%. This industry, which was impacted by the sharp decrease in the price of oil in 2014/2015, experienced the highest percentage increase in EI regular claims. Further analysis shows that the increase in EI regular claims in this industry was concentrated in three provinces: Alberta (+71.3%), British Columbia (+41.4%) and Nova Scotia (+31.3%). It has to be stated that, even with this increase in EI regular claims, the Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction industry only accounts for 2% of the overall EI regular claims.

Consistent with 2013/2014, the three industries that accounted for the highest number of claims in 2014/2015 were: the construction industry (20%), the manufacturing industry (11%) and the educational services industry (11%) (see Table 9). These three industries accounted for 42% of EI regular claims.

| Industry | New Claims Established1 | Amount Paid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Share) | ($ Million) | (Share) | ||||

| 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2014/2015 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2014/2015 | |

| Goods-Producing Industries | 512,200 | 511,030 | 38% | 4,349.4 | 4,379.8 | 41% |

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | 57,140 | 56,880 | 4% | 503.6 | 500.7 | 5% |

| Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction | 24,380 | 28,900 | 2% | 253.1 | 238.9 | 2% |

| Utilities | 4,680 | 4,420 | 0% | 40.0 | 41.1 | 0% |

| Construction | 274,730 | 274,140 | 20% | 2,324.7 | 2,376.8 | 22% |

| Manufacturing | 151,270 | 146,690 | 11% | 1,228.0 | 1,222.4 | 12% |

| Services-Producing Industries | 769,260 | 748,370 | 56% | 5,734.3 | 5,656.9 | 53% |

| Wholesale Trade | 43,940 | 44,050 | 3% | 435.7 | 421.0 | 4% |

| Retail Trade | 79,210 | 72,850 | 5% | 630.3 | 607.0 | 6% |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 56,690 | 56,270 | 4% | 412.9 | 400.3 | 4% |

| Finance and Insurance | 14,750 | 13,820 | 1% | 167.0 | 155.9 | 1% |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 18,050 | 18,030 | 1% | 155.3 | 163.7 | 2% |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 53,800 | 54,690 | 4% | 510.6 | 505.4 | 5% |

| Business, Building and Other Support Services2 | 96,850 | 93,310 | 7% | 784.5 | 787.0 | 7% |

| Educational Services | 145,810 | 146,040 | 11% | 605.8 | 634.6 | 6% |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 48,840 | 47,160 | 4% | 360.2 | 362.2 | 3% |

| Information, Cultural and Recreation3 | 41,960 | 39,470 | 3% | 332.8 | 318.3 | 3% |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 63,360 | 58,550 | 4% | 460.3 | 427.2 | 4% |

| Other Services (except Public Administration) | 40,700 | 40,730 | 3% | 336.6 | 334.4 | 3% |

| Public Administration | 65,300 | 63,400 | 5% | 542.3 | 539.9 | 5% |

| Unclassified | 44,350 | 83,210 | 6% | 283.9 | 565.3 | 5% |

| Canada | 1,325,810 | 1,342,610 | 100% | 10,367.6 | 10,602.1 | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- 2 This industry comprises the industries with codes 55 (management of companies and enterprises) and 56 (administrative and support, waste management and mediation services) from the North American Industry Classification System.

- 3 This industry comprises the industries with codes 51 (information and cultural industries) and 71 (arts, entertainment and recreation) from the North American Industry Classification System.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

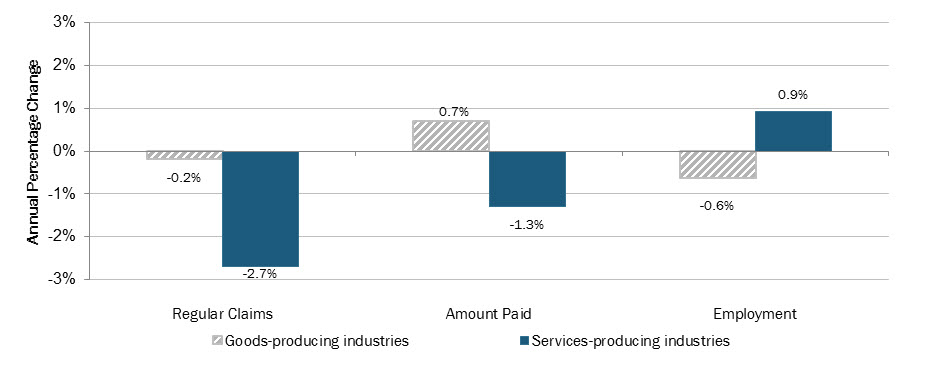

In 2014/2015, the number of new EI regular claims in the goods-producing industries remained fairly constant, decreasing by just 0.2%. The decrease in the number of claims in the goods industry was driven by a decrease in the Manufacturing industry, but was offset by the year-over-year increase of 18.5% in the Mining, Oil and Gas Extraction industry. As illustrated in Chart 14, the goods industry observed a modest employment loss of 0.6% in 2014/2015. Unlike the goods industry, the services industry showed a modest employment gain of 0.9%, while the number of EI regular claims decreased by 2.7%. The decline in EI regular claims in the service industry was driven by decreases in new claims in Retail Trade (-8.0%), Accommodation and Food Services (-7.6%), and Business, Building and Other Support Services (-3.7%).

Despite the decrease in the number of regular claims, 2014/2015 saw a modest 0.7% increase in the amount paid in the goods-producing industries (see Chart 14). This is attributable to the increase in amount paid to the construction sector, which made up 54% of the goods-producing industries’ new claims in 2014/2015. Unsurprisingly, the services-producing industries saw a 1.3% decline in the amount of regular benefits paid, driven primarily by the large overall decrease in the amount of regular claims in these industries.

Show Data Table

| 2014/2015 (Annual percentage change) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Claims | Amount Paid | Employment | |

| Goods-producing industries | -0.2% | 0.7% | -0.6% |

| Services-producing industries | -2.7% | -1.3% | 0.9% |

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data (for data on regular claims and amount paid); and Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, CANSIM Table 282-0007 (for data on employment). ESDC data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

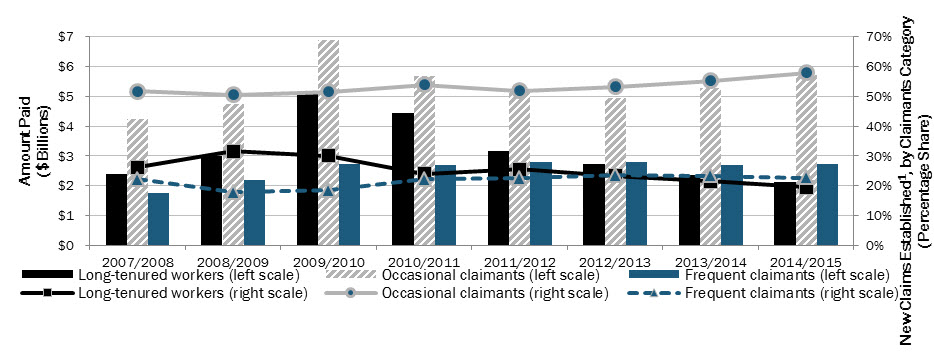

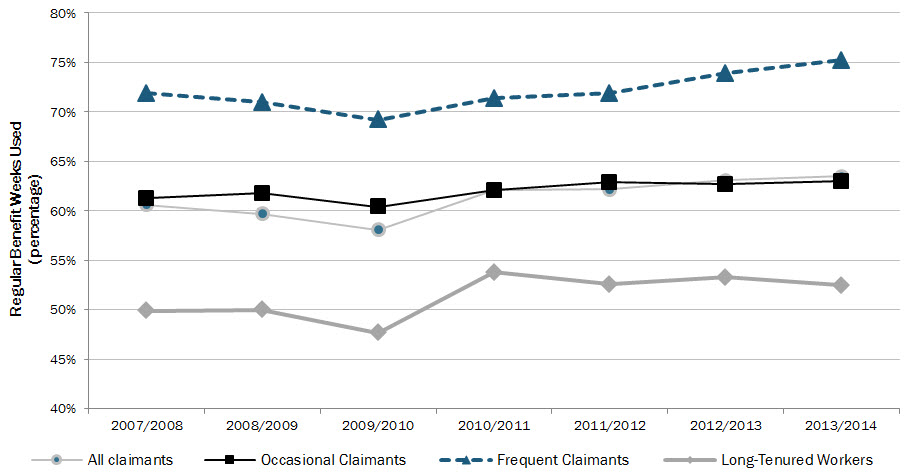

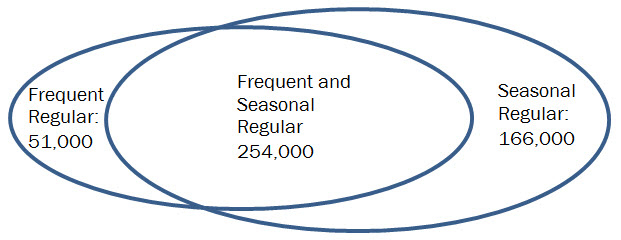

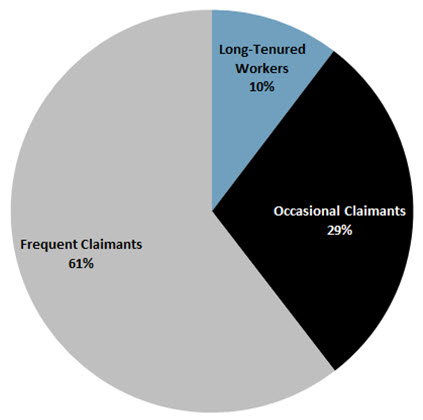

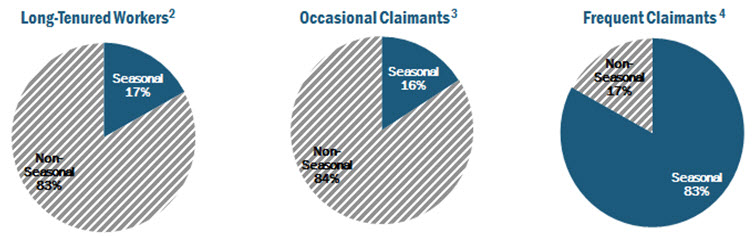

Similar to last year, the distribution of EI regular claims by EI claimant category shows that frequent claimants accounted for roughly 23% of new claims established. The proportion of long-tenured workers and occasional claimants however fluctuated slightly: while the percentage of long-tenured workers decreased by 2 percentage points, from 21% to 19%, occasional claimants’ share of EI claims increased by 3 percentage points, from 55% to 58% (see Table 10).

| Claimant Category2 | New Claims Established1 | Amount Paid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Share) | ($ Million) | (Share) | ||||

| 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2014/2015 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2014/2015 | |

| Long-tenured Workers | 285,000 | 261,760 | 20% | 2,377.2 | 2,136.9 | 20% |

| Occasional Claimants | 731,030 | 776,150 | 58% | 5,278.5 | 5,735.6 | 54% |

| Frequent Claimants | 309,780 | 304,700 | 23% | 2,712.0 | 2,729.6 | 26% |

| Canada | 1,325,810 | 1,342,610 | 100% | 10,367.6 | 10,602.1 | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- 2 Long-tenured workers are Employment Insurance (EI) claimants who have paid at least 30% of the maximum annual EI premiums for the past 7 of 10 years and who, over the last 5 years, have collected EI regular or fishing benefits for 35 weeks or less. Frequent claimants are EI claimants who have had three or more claims for EI regular or fishing benefits and have collected benefits for a total of more than 60 weeks in the past 5 years. Occasional claimants are EI claimants who do not meet the requirements for either long-tenured workers or frequent claimants.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

The total amount paid to the different EI claimant categories have also remained constant over the 2013/2014 and 2014/2015 years. While occasional claimants make up the bulk of the both new claims and amount paid, this claimant category is underrepresented as a share of amount paid, making up 4 percentage points less of the total new claims. Conversely, frequent claimants are overrepresented, making up 3 percentage points more of the total amount paid than total new claims. This indicates that frequent claimants have, on average, longer benefit durations and/or higher average weekly benefit rates than occasional claimants.

The number of long-tenured workers has been declining since the 2008 downturn. As such, the number of EI regular claims established for long-tenured workers in 2014/2015 is close to half of those in 2008/2009 (261,760 and 519,780, respectively). Not only did the number of EI regular claims for long-tenured workers decline since 2008/2009 but their share of claims also declined (from 32% to 20%) (see Chart 15). In addition, the amount paid to this claimant category has declined 57.8% since the recession, when it reached a high of $5.1 billion in 2009/2010.

Show Data Table

| Amount Paid ($ Billion) | New Regular Claims Established (Percentage share) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-tenured workers | Occasional claimants | Frequent claimants | Long-tenured workers | Occasional claimants | Frequent claimants | |

| 2007/2008 | $2.4 | $4.2 | $1.8 | 26% | 52% | 22% |

| 2008/2009 | $3.0 | $4.8 | $2.2 | 32% | 51% | 18% |

| 2009/2010 | $5.1 | $6.9 | $2.7 | 30% | 51% | 19% |

| 2010/2011 | $4.4 | $5.7 | $2.7 | 24% | 54% | 22% |

| 2011/2012 | $3.2 | $5.2 | $2.8 | 26% | 52% | 23% |

| 2012/2013 | $2.7 | $5.0 | $2.8 | 23% | 53% | 24% |

| 2013/2014 | $2.4 | $5.3 | $2.7 | 22% | 55% | 23% |

| 2014/2015 | $2.1 | $5.7 | $2.7 | 20% | 58% | 23% |

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- 2 Long-tenured workers are Employment Insurance (EI) claimants who have paid at least 30% of the maximum annual EI premiums for the past 7 of 10 years and who, over the last 5 years, have collected EI regular or fishing benefits for 35 weeks or less. Frequent claimants are EI claimants who have had three or more claims for EI regular or fishing benefits and have collected benefits for a total of more than 60 weeks in the past 5 years. Occasional claimants are EI claimants who do not meet the requirements for either long-tenured workers or frequent claimants.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Unlike long-tenured workers, occasional claimants’ share of EI regular claims has increased between 2008/2009 and 2014/2015 (from 51% to 58%). The number of EI claims made by occasional claimants has decreased between the years of 2008/2009 to 2012/2013 (from 830,660 to 720,810), but is trending upward since then (776,150 in 2014/2015). Consistent with this upward trend, this claimant category saw the highest increase in amount paid from 2013/2014 to 2014/2015, at 8.7% -- it is the second consecutive year where occasional claimants saw an increase in amount paid.

Finally, the proportion of EI regular claims established by frequent claimants has increased every year from 2008/2009 to 2012/2013 (18% to 24%) and has been stable since then at around 23% (see Chart 15). The number of claims made by frequent claimants has increased for the period from 2008/2009 to 2011/2012, but has since been trending downward. Amount paid to frequent claimants has also continued to be constant, remaining around $2.7 billion for six consecutive years.

2.1.3 Employment Insurance regular claims, by education level, hours of insurable employment, and unemployment rate in the Employment Insurance economic region

Analysis by educational level shows that most EI regular claims were made by claimants who worked in occupations that required college or apprenticeship training (34%) or secondary school and/or occupation specific training (33%). Data suggests that occupations that required a university degree or management studies tended to use less of the EI program. Table 11 also shows that the share of EI regular claims by education level has remained fairly stable over time.

| Education Level | New Claims Established1

(Share) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

| Management | 4% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| University | 7% | 7% | 7% | 8% | 8% | 8% | 8% | 8% |

| College or apprenticeship training | 31% | 32% | 33% | 32% | 33% | 33% | 34% | 34% |

| Secondary school and/or occupation specific training | 36% | 36% | 35% | 34% | 34% | 33% | 33% | 33% |

| On the job training | 22% | 21% | 19% | 22% | 21% | 21% | 20% | 20% |

| Canada | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

In 2014/2015, 39% of EI regular claims made by youth (24 years and under) were in positions that required either a college diploma or apprenticeship training, and 25% occupied positions that required secondary school or occupation specific training. In contrast, 38% of regular claims established by workers aged 45 years and older were in positions that required secondary school or occupation specific training, and 31% were in positions that required either a college diploma or apprenticeship training. This fact suggests that older workers who establish an EI claim tend to be less educated than younger workers.

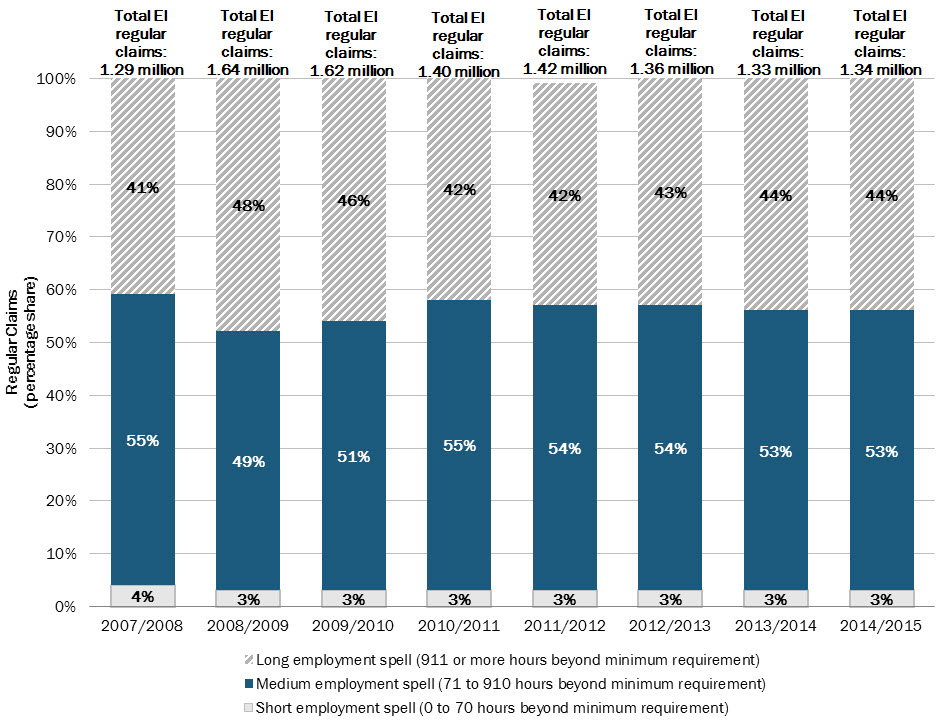

The unemployment rate in an EI economic region determines the number of hours of insurable employment needed to qualify for EI. The higher the unemployment rate, the lower is the number of hours needed to qualify. In 2014/2015, a high proportion of EI regular claims were made by claimants who had accumulated 1,820 hours or more of insurable employment during their qualifying period (26.4%), which was an increase of 0.8 percentage point compared to 2013/2014. Table 12 shows that this percentage has been increasing since 2011/2012. It also shows that this proportion was much higher in 2008/2009 (31.1%) when the last recession started. One of the reasons for this is that a higher proportion of long-tenured workers lost their jobs and started receiving EI benefits in 2008/2009, and that these claimants had accumulated several hours of employment in the qualifying period (generally 52 weeks prior to their claim).

| Hours of Insurable Employment | New Claims Established1

(Share) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

| Less than 700 hours | 5.4% | 4.6% | 6.9% | 6.9% | 6.1% | 5.5% | 5.2% | 4.8% |

| 700 to 979 hours | 15.9% | 13.8% | 15.6% | 16.9% | 16.3% | 15.5% | 15.2% | 15.2% |

| 980 to 1,259 hours | 19.8% | 17.7% | 18.6% | 19.6% | 19.5% | 19.3% | 19.1% | 19.1% |

| 1,260 to 1,539 hours | 17.7% | 16.5% | 16.6% | 17.3% | 17.9% | 18.4% | 18.4% | 18.3% |

| 1,540 to 1,819 hours | 15.8% | 16.3% | 15.6% | 15.7% | 16.2% | 16.5% | 16.6% | 16.3% |

| 1,820 hours and more | 25.3% | 31.1% | 26.7% | 23.5% | 24.1% | 24.8% | 25.6% | 26.4% |

| Canada | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

Statistics for the other increments of hours of insurable employment show that the proportion of claimants who accumulated less than 700 hours of insurable employment has been declining every year since 2010/2011. This is partially attributable to the gradual decrease of the unemployment rate in many EI economic regions, which consequently increases the number of hours needed to qualify for the program in these regions.

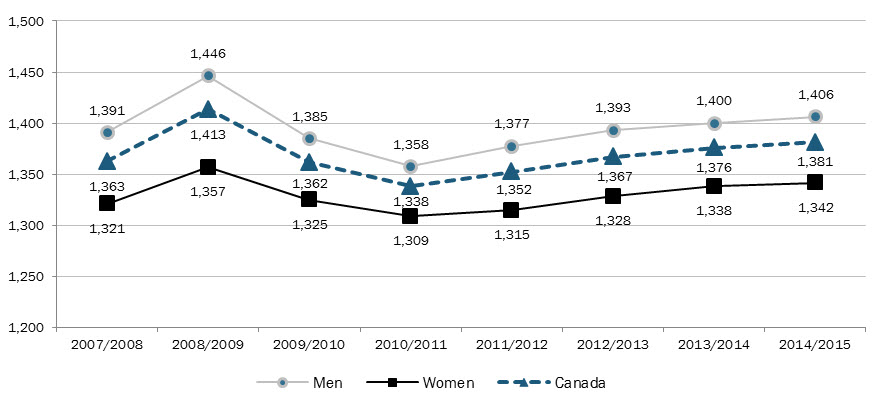

Chart 16 depicts the average number of hours of insurable employment per claim that qualified for EI benefits, which has been increasing every year since 2011/2012, from 1,338 to 1,381 hours. As expected, the number of hours of insurable employment per claim fluctuates by province. The number of hours in the Atlantic provinces tends to be lower than in other provinces. In 2014/2015, Newfoundland and Labrador showed the lowest average number of hours of insurable employment at 1,206, while claims established in Alberta had the highest average number of hours with 1,542 hours.

The average number of hours of insurable employment also fluctuates by sex and by age. Statistics show that claims made by men had, on average, 64 more hours of insurable employment than claims established for women in 2014/2015 (1,406 and 1,342 hours, respectively). This gap has remained constant over the last four years. Data by age show that claimants aged 55 years and over had accumulated the lowest number of hours of insurable employment in 2014/2015 (1,312), while those between 25 and 44 years of age had accumulated the highest number of hours (1,413).

Show Data Table

| Men | Women | Canada | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 1,391 | 1,321 | 1,363 |

| 2008/2009 | 1,446 | 1,357 | 1,413 |

| 2009/2010 | 1,385 | 1,325 | 1,362 |

| 2010/2011 | 1,358 | 1,309 | 1,338 |

| 2011/2012 | 1,377 | 1,315 | 1,352 |

| 2012/2013 | 1,393 | 1,328 | 1,367 |

| 2013/2014 | 1,400 | 1,338 | 1,376 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,406 | 1,342 | 1,381 |

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% of EI administrative data.

To conclude, Table 13 shows that the distribution of new EI regular claims by regional unemployment rates fluctuates on a yearly basis. While the percentage of new EI regular claims established in EI economic regions with an unemployment rate of 6.0% or lower was 14% in 2013/2014, it increased to 20% in 2014/2015. The increase in the number of EI regular claims established in Alberta is one reason for the increase in EI regular claims in the unemployment rate threshold of “less than or equal to 6.0%”, as more than 90% of claims established in Alberta (95,940 out of 105,780) were made in regions where the unemployment rate was under 6.1% in 2014/2015.

| Regional Unemployment Rate2 | New Claims Established1

(Share) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

| 0.1% to 6.0% | 26% | 8% | 8% | 13% | 15% | 14% | 20% |

| 6.1% to 7.0% | 18% | 9% | 9% | 12% | 12% | 15% | 12% |

| 7.1% to 8.0% | 24% | 11% | 16% | 12% | 13% | 20% | 25% |

| 8.1% to 9.0% | 8% | 14% | 24% | 33% | 33% | 25% | 18% |

| 9.1% to 10.0% | 3% | 28% | 15% | 10% | 7% | 4% | 6% |

| 10.1% to 11.0% | 6% | 8% | 8% | 5% | 4% | 6% | 4% |

| 11.1% to 12.0% | 2% | 6% | 6% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 3% |

| 12.1% to 13.0% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| 13.1% to 14.0% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 0% |

| 14.1% to 15.0% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| 15.1% to 16.0% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 4% | 2% |

| 16.1% or higher | 6% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 6% | 8% |

| Canada | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Includes claims for which at least $1 of regular benefits was paid.

- 2 Unemployment rates used for the Employment Insurance program are a moving average of seasonally adjusted rates of unemployment produced by Statistics Canada, as per section 17 of the Employment Insurance Regulations.

- Source: ESDC, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 10% sample of EI administrative data.

2.2 Coverage, eligibility and access to Employment Insurance regular benefits

As previously indicated, the Employment Insurance (EI) program provides temporary financial assistance to unemployed individuals who have recently lost employment for reasons outside their control (e.g., a valid job separation), contributed to the program and accumulated the required number of hours of insurable employment over the past year or since their last claim—whichever is shorter.

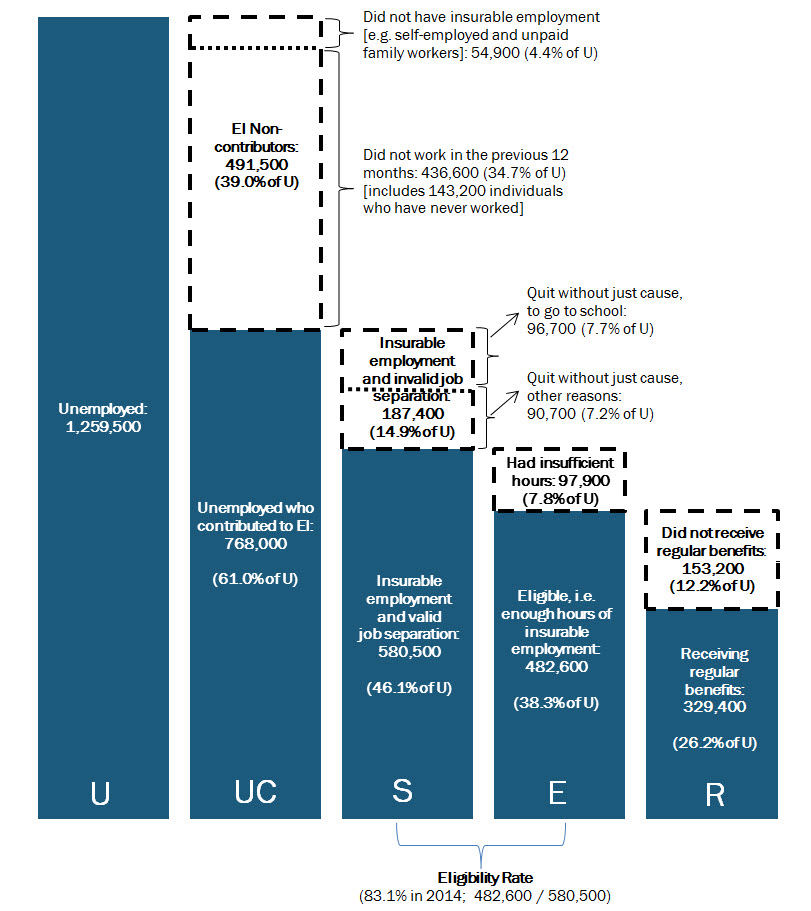

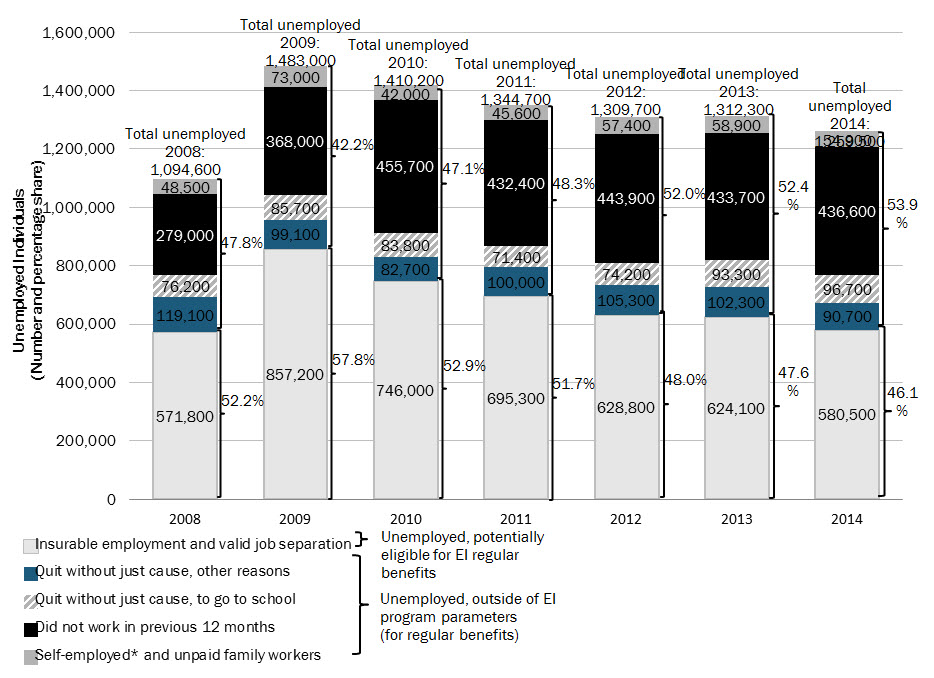

The following sections examine the unemployed population and various sub-populations of the unemployed population as they relate to the EI program. More specifically, the unemployed population is examined from the perspective of the core eligibility requirements (contribution to EI, valid job separation, and sufficient hours of insurable employment). As illustrated in Chart 17, in 2014 there were 1,259,500 unemployed individuals (bar U), of which 768,000 had contributed to the EI program (bar UC). Of those who had worked and contributed to EI, there were 580,500 individuals who had a valid job separation (bar S). The sub-populations include 482,600 individuals who were eligible for EI—meaning they also had accumulated enough hours of insurable employment to qualify for EI regular benefits (bar E); of that group, a total of 329,400 individuals received regular benefits (bar R).

The following section elaborates on the number of unemployed individuals in 2014 who were covered by the EI program (section 2.2.1), were eligible for EI regular benefits (section 2.2.2) and had access to EI regular benefits (section 2.2.3). The majority of the statistics in these sections are based on results from the 2014 Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (EICS) Footnote 33 conducted by Statistics Canada. The EICS was originally launched in 1997, primarily to better understand the relationship between the number of persons in receipt of EI benefits and the number of unemployed. The results allow users to draw a comprehensive profile of the unemployed and other persons who may have been entitled to EI benefits due to a recent break in employment.

Show Data Table

| 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number | Share of Unemployed | |

| Unemployed | 1,259,500 | Not applicable |

| Unemployed who contributed to EI | 768,000 | 61.0% |

| Insurable employment and valid job separation | 580,500 | 46.1% |

| Eligible: Enough insurable hours | 482,600 | 38.3% |

| Receiving regular benefits | 329,400 | 26.2% |

| EI non-contributors | 491,500 | 39.0% |

| Insurable employment and invalid job separation | 187,400 | 14.9% |

| Ineligible: Insufficient insurable hours | 97,900 | 7.8% |

| Did not receive regular benefits | 153,200 | 12.2% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

2.2.1 Coverage of Employment Insurance regular benefits

The EI program’s definition of coverage is similar to that of other insurance programs. As such, an individual is considered to be covered by the EI program if he or she has paid EI premiums at a given time in the previous 12 months.

This section analyzes the unemployed population who paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months leading up to their period of unemployment in 2014. Also examined is the population of unemployed individuals who had not paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months.

2.2.1.1 Coverage of Employment Insurance regular benefits, national statistics

According to the EICS, there were 1,259,500 unemployed individuals in Canada (shown as bar U in Chart 17) in 2014. Footnote 34 This represents a decrease of 4.0% from the 1,312,300 unemployed individuals reported in 2013.

The 2014 EICS estimated that, among the 1,259,500 unemployed individuals, 768,000 had paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months before becoming unemployed (referred to as contributors), representing 61.0% of all unemployed people (see Chart 17, blue bar UC), a small decline compared to 2013 (62.5%).

According to the 2014 EICS, there were 491,500 individuals who had not contributed to EI in the previous 12 months (referred to as non-contributors), representing 39.0% of the unemployed (see Chart 17, white bar above UC). Those who had not paid EI premiums include self-employed workers, Footnote 35 unpaid family workers, and individuals who have not worked in the previous 12 months including those who had never worked. As illustrated in Chart 17 (white bar above UC), in 2014, there were 54,900 self-employed and unpaid family workers representing 4.4% of the total unemployed population; in addition, there were 436,600 individuals who did not work in the previous 12 months including those who had never worked, representing 34.7% of the total unemployed population.

Table 14 provides a distribution of unemployed EI contributors and non-contributors. The EI coverage rate (proportion of the unemployed who had paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months) decreased from 70.0% to 61.0% between 2007 (just before the 2008 recession) and 2014. This decrease can be attributed to increases in the proportion of unemployed individuals who had not worked in the previous 12 months, which can be further broken down by i) individuals who had not worked in the previous 12 months, excluding those who had never worked (+5.7 percentage points), and ii) individuals who had never worked (+4.2 percentage points).

| Employment Insurance Contributors and Non-Contributors | Unemployed Population (Share) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Employment Insurance Contributors | 70.0% | 70.1% | 70.3% | 64.7% | 64.5% | 61.7% | 62.5% | 61.0% |

| Employment Insurance Non-contributors | 30.0% | 29.9% | 29.7% | 35.3% | 35.5% | 38.3% | 37.5% | 39.0% |

| Have No Recent Insurable Employment (e.g. Self-employed1 and Unpaid Family Workers) | 5.2% | 4.4% | 4.9% | 3.0% | 3.4% | 4.4% | 4.5% | 4.4% |

| Have Not Worked in the Previous 12 Months (Excluding Those Who Have Never Worked) | 17.6% | 18.3% | 18.3% | 24.1% | 25.0% | 24.6% | 24.3% | 23.3% |

| Have Never Worked | 7.2% | 7.2% | 6.5% | 8.3% | 7.1% | 9.3% | 8.8% | 11.4% |

| Canada | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Self-employed individuals can opt in and subsequently pay EI premiums for special benefits, but they are not eligible for regular benefits.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

2.2.1.2 Coverage of Employment Insurance regular benefits, by region

EI coverage rates vary by region, ranging from a high of 79.4% in the Atlantic provinces to lows of 54.7% in Ontario and 59.6% in the Western provinces. Regions with higher coverage rates are those that have a lower proportion of individuals who had not worked in the previous 12 months. As indicated in Table 15, 18.0% of the Atlantic provinces’ unemployed population did not work in the previous 12 months, which consists of those who i) had not worked in the previous 12 months (excluding those who had never worked) and ii) had never worked; the proportions were comparatively higher in Ontario (40.9%) and in the Western provinces (36.5%).

| Employment Insurance Contributors and Non-Contributors | Unemployed Population (Share) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic1 | Quebec | Ontario | Western2 | Canada | |

| Employment Insurance Contributors | 79.4% | 65.4% | 54.7% | 59.6% | 61.0% |

| Employment Insurance Non-contributors | 20.6% | 34.6% | 45.3% | 40.4% | 39.0% |

| Have No Recent Insurable Employment (e.g. Self-employed3 and Unpaid Family Workers) | 2.6% | 5.4% | 4.4% | 3.9% | 4.4% |

| Have Not Worked in the Previous 12 Months (Excluding Those Who Have Never Worked) | 13.0% | 20.7% | 27.2% | 23.4% | 23.3% |

| Have Never Worked | 5.0% | 8.5% | 13.7% | 13.1% | 11.4% |

| Canada | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 The Atlantic provinces comprise Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

- 2 The Western provinces comprise Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

- 3 Self-employed individuals can opt in and subsequently pay EI premiums for special benefits, but they are not eligible for regular benefits.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

2.2.1.3 Coverage of Employment Insurance regular benefits, by gender and age

In 2014, the male coverage rate was 69.0%, increasing from 64.3% in 2013, which can be attributed to decreases in the number of individuals who had no recent insurable employment and those who had not worked in the previous 12 months (excluding those who had never worked). Conversely, the female coverage rate was 50.1%, decreasing from 60.0% in 2013¬, which is primarily attributed to a significant increase in women who had never worked (+44.5% or +25,600). As a result, the gender gap in the coverage rate increased to 18.9 percentage points in 2014, an increase of 14.6 percentage points compared to 2013. The average gap over the previous five years was 6.2 percentage points.

In 2014, the youth (15 to 24 years) coverage rate decreased to 50.3%, from 54.0% in 2013. Adults (25 years and older) had a 65.3% coverage rate, decreasing slightly from 65.5% in 2013. Coverage rates among youth tend to be significantly lower than those of adults because youth are less likely to have insurable employment, and are more likely to have never worked. In 2014, among unemployed youth, 29.5% had never worked—almost double the proportion witnessed in 2008 (15.7%)—compared to 4.0% for those aged 25 and older.

2.2.2 Eligibility for Employment Insurance regular benefits

To be eligible for EI regular benefits, individuals must first be covered by the EI program—meaning they must have paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months before their period of unemployment. In addition, to be eligible, individuals must have had a valid job separation and have accumulated enough hours of insurable employment before their job separation.

This section examines the individuals with a valid job separation and who have accumulated enough hours of insurable employment to be eligible for EI regular benefits (see Chart 17, blue bar E).

2.2.2.1 Eligibility for Employment Insurance regular benefits, national statistics

The 2014 EICS estimated that 580,500 unemployed individuals had a valid job separation, making them potentially eligible for EI regular benefits (see Chart 17, blue bar S).

In 2014, there were also 187,400 (14.9%) individuals whose job separation did not meet the EI program’s requirements (see Chart 17, white bar above S). These include unemployed individuals who quit their job to go to school (96,700 or 7.7% of the unemployed population) and those who quit for other reasons without just cause Footnote 36 (90,700 or 7.2% of the unemployed population).

Among the 580,500 unemployed population in 2014 who were covered by the EI program and had a valid job separation, 482,600 had accumulated enough hours to qualify for EI regular benefits (see Chart 17, blue bar E), for an eligibility rate of 83.1% (482,600 / 580,500). The 2014 EI eligibility rate of 83.1% represents a decrease of 2.7 percentage points from 85.8% in 2013 but remains above pre-recession levels (i.e. 82.3% in 2007 and 82.7% in 2006).

The remaining 97,900 of the unemployed population who had contributed to EI in the previous 12 months and had a valid job separation did not accumulate sufficient hours of insurable employment to qualify for EI regular benefits in 2014.

2.2.2.2 Eligibility for Employment Insurance regular benefits, by province

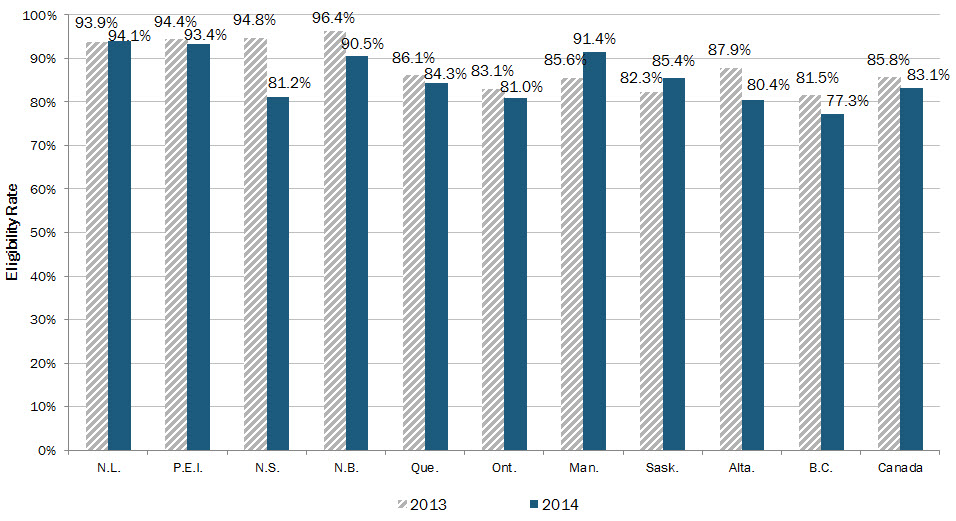

In 2014, eligibility rates ranged from a low of 77.3% in British Columbia to a high of 94.1% in Newfoundland and Labrador (see Chart 18). Compared with 2013 EICS figures, the EI eligibility rate decreased in 7 out of the 10 provinces. The largest decreases occurred in Nova Scotia (-13.6 percentage points) and Alberta (-7.5 percentage points). From 2013 to 2014, in both Nova Scotia and Alberta, a smaller proportion of the unemployed with insurable employment and a valid job separation had accumulated enough hours of insurable employment to qualify for EI. The drops in eligibility in both Nova Scotia and Alberta may be associated with differences in the composition of workers. Manitoba (+5.8 percentage points), Saskatchewan (+3.1 percentage points) and Newfoundland and Labrador (+0.2 percentage point) showed slight to moderate increases to their eligibility rate.

Show Data Table

| Eligibility rate | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | |

| N.L. | 93.9% | 94.1% |

| P.E.I. | 94.4% | 93.4% |

| N.S. | 94.8% | 81.2% |

| N.B. | 96.4% | 90.5% |

| Que. | 86.1% | 84.3% |

| Ont. | 83.1% | 81.0% |

| Man. | 85.6% | 91.4% |

| Sask. | 82.3% | 85.4% |

| Alta. | 87.9% | 80.4% |

| B.C. | 81.5% | 77.3% |

| Canada | 85.8% | 83.1% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

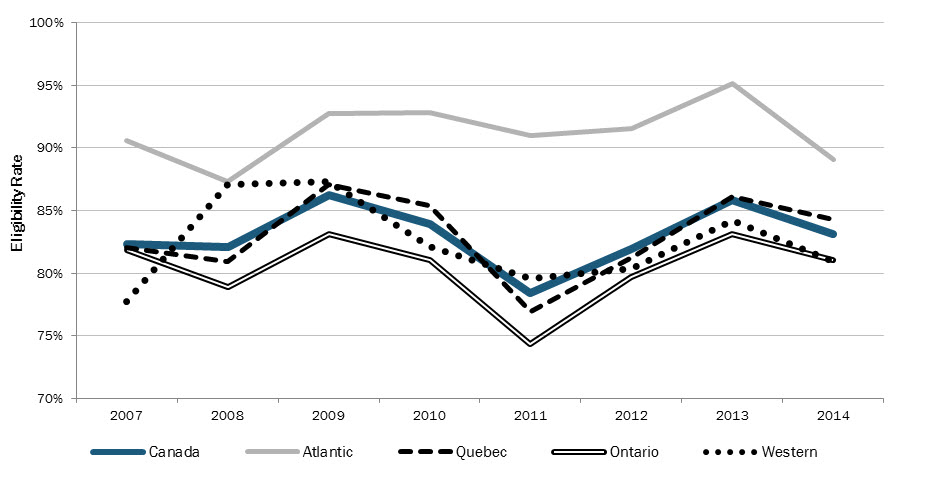

Eligibility rates may increase or decrease nationally, and by province and region, over the course of several years. Chart 19 shows that the national eligibility rate increased in 2009, after the 2008 recession. It has since decreased in 2010 and 2011, and increased in 2012 and 2013, before decreasing again in 2014. More information on eligibility trends can be found in section 2.2.2.4.

Show Data Table

| Eligibility rate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Canada | 82.3% | 82.1% | 86.2% | 83.9% | 78.4% | 81.9% | 85.8% | 83.1% |

| Atlantic | 90.6% | 87.3% | 92.7% | 92.8% | 91.0% | 91.5% | 95.1% | 89.1% |

| Quebec | 82.0% | 80.9% | 87.1% | 85.4% | 76.9% | 81.2% | 86.1% | 84.3% |

| Ontario | 81.8% | 78.9% | 83.1% | 81.0% | 74.3% | 79.7% | 83.1% | 81.0% |

| Western | 77.7% | 87.1% | 87.3% | 82.1% | 79.6% | 80.4% | 84.2% | 80.9% |

- Note 1: The Atlantic provinces comprise Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

- Note 2: The Western provinces comprise Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

Eligibility rates by province and region generally follow the national trends; however, the degree of eligibility varies. For example, from 2007 to 2014, the Atlantic provinces have consistently had higher eligibility rates than the rest of the country, averaging 91.3% during that time. Comparatively, Ontario’s eligibility rate averaged 80.4% during the past eight years, lowest among all regions depicted in Chart 19. Quebec and the Western provinces experienced eligibility rates which more closely resembled the national trends.

2.2.2.3 Eligibility for Employment Insurance regular benefits, by gender and age

In 2014, EI eligibility rates decreased for all demographic groups, except for women and adult women (25 years and older) (see Table 16). The EI eligibility rate for men decreased from 89.8% in 2013 to 84.0% in 2014, while eligibility for women increased from 80.0% to 81.3%. The 5.8 percentage point decrease in the male eligibility rate in 2014 is attributed to i) a decrease in the number of men who had enough hours to qualify for EI regular benefits (-2.0%), and ii) an increase in the pool of men who had insurable employment and a valid job separation (+4.7%).

| Gender and Age Group | Eligibility Rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Men | 84.6% | 87.3% | 83.6% | 79.4% | 81.9% | 89.8% | 84.0% |

| Women | 77.8% | 84.3% | 84.4% | 77.0% | 81.9% | 80.0% | 81.3% |

| Youth (15 to 24 Years) | 51.9% | 62.8% | 48.4% | 42.1% | 45.2% | 54.5% | 44.0% |

| Adults (25 Years and Older) | 89.1% | 90.5% | 89.6% | 85.1% | 87.9% | 90.4% | 87.9% |

| Adult Men (25 Years and Older) | 90.6% | 91.8% | 89.5% | 87.4% | 86.8% | 93.8% | 88.8% |

| Adult Women (25 Years and Older) | 86.4% | 88.3% | 89.6% | 82.0% | 88.9% | 85.5% | 86.3% |

| Canada | 82.2% | 86.2% | 83.9% | 78.4% | 81.9% | 85.8% | 83.1% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

As reported in previous EI Monitoring and Assessment Reports, gender differences in eligibility rates reflect different employment characteristics among men and women. A higher proportion of men than women hold full-time and/or permanent jobs; women tend to be over-represented among those working in part-time and/or temporary jobs.

The youth (15 to 24 years) eligibility rate has shown large fluctuations between 2012 and 2014, increasing from 45.2% in 2012 to 54.5% in 2013, before decreasing to 44.0% in 2014. The youth eligibility rate has historically been associated with a significantly higher coefficient of variation, Footnote 37 which contributes to the large variations witnessed in recent years, compared to the adult eligibility rate, which is more stable. The significant decrease in the youth eligibility rate in 2014 can be primarily attributed to a decrease in the number youth who had enough hours to qualify for EI regular benefits (-35.2%), among youth who had insurable employment and a valid job separation.

The youth eligibility rate (44.0%) is the lowest among all age groups, consistent with prior year data. A low eligibility rate for youth is associated with the type of work that this group usually performs, which is either part-time and/or temporary work. Therefore, they tend to accumulate fewer hours of work. The adult (25 years and older) eligibility rate was considerably higher (87.9%) than that of youth (15 to 24 years). Higher adult eligibility rates reflect more stable employment and more hours of insurable employment (e.g. permanent full-time work).

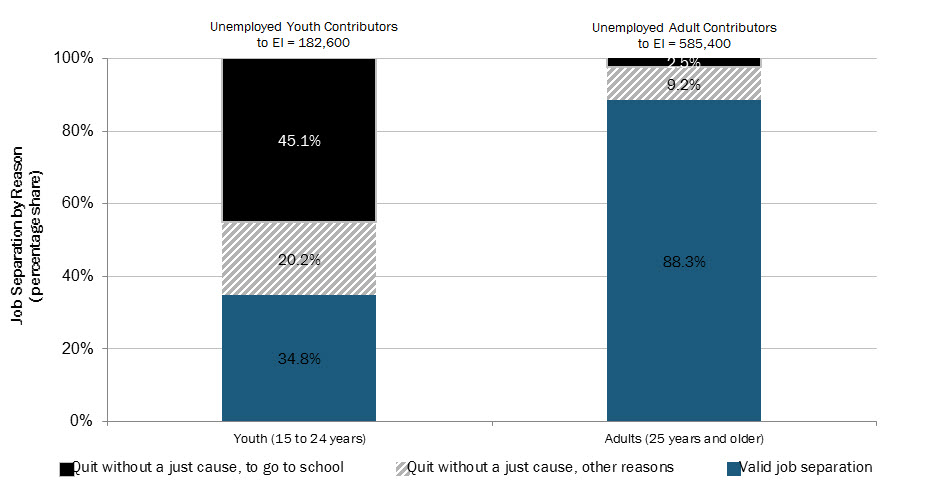

It is also important to note that among the 182,600 unemployed youth contributors to EI (who were potentially eligible for EI regular benefits), 65.3% quit without a just cause (45.1% to go to school, and 20.2% for other reasons), compared to 11.7% (2.5% to go to school, and 9.2% for other reasons) among adults (25 years and older) (see Chart 20). The high incidence of quits without a just cause among youth reduces the number of youth who could potentially be eligible for EI regular benefits. Only 34.8% of unemployed youth contributors had a valid job separation, compared to 88.3% for adults.

Show Data Table

| 2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24 years) | Adults (25 years and older) | ||

| Unemployed Contributors to EI | 182,600 | 585,400 | |

| Job separation by reason (percentage share) | Quit without a just cause, to go to school | 45.1% | 2.5% |

| Quit without a just cause, other reasons | 20.2% | 9.2% | |

| Valid job separation | 34.8% | 88.3% | |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

2.2.2.4 Eligibility trends over the economic cycle

In general, the eligibility rate increases at the beginning of an economic downturn as the unemployed pool is composed of a greater percentage of newly unemployed workers who had relatively long, uninterrupted periods of employment. These workers would have accumulated enough hours to qualify for EI regular benefits. The eligibility rate also changes if there are structural changes in the labour market. When total employment is composed of a higher proportion of full-time employment (and a lower proportion of part-time employment), the incidence of being eligible for EI is higher. This is because full-time workers are more likely to have accumulated enough hours of insurable employment, and as a result, are more likely to be eligible to receive regular benefits.

From 2008 to 2009, as the recession took hold, the national eligibility rate increased to a high of 86.2% in 2009, from 82.2% in 2008 (see Table 17). The increase was attributed to the change in the composition of unemployed EI contributors. A large number of individuals became unemployed with insurable employment, a valid job separation and enough hours of insurable employment, making them eligible to receive EI regular benefits.

Between 2010 and 2011, as the recovery began, the national eligibility rate decreased from 83.9% to a historical low of 78.4%. This was the result of a shift in the composition of unemployed workers, as the proportion of unemployed permanent full-time workers as a share of unemployed workers with insurable employment and a valid job separation, decreased from 50.9% in 2010 to 45.3% in 2011 (see Table 17). This group has historically had a high eligibility rate (90-95%). In contrast, the proportion of unemployed temporary non-seasonal workers as a share of unemployed workers with insurable employment and a valid job separation increased from 24.7% in 2010 to a high of 28.1% in 2011. This group has historically had a lower eligibility rate (60-70%).

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment Rate | 6.1% | 8.3% | 8.1% | 7.5% | 7.3% | 7.1% | 6.9% |

| Eligibility Rate | 82.2% | 86.2% | 83.9% | 78.4% | 81.9% | 85.8% | 83.1% |

| Permanent Workers | 87.6% | 92.2% | 92.4% | 87.2% | 89.9% | 91.4% | 87.7% |

| Permanent Full-time Workers | 92.7% | 94.3% | 94.5% | 91.2% | 94.6% | 95.0% | 90.1% |

| Permanent Part-time Workers | 47.7% | 68.8% | 74.4% | 54.9% | 65.2% | 71.4% | 66.2% |

| Permanent Workers, Work Hours Unknown | 100.0% | 71.5% | 91.7% | 100.0% | 96.4% | 69.2% | 80.6% |

| Temporary Workers | 73.5% | 75.3% | 72.3% | 68.3% | 72.5% | 79.0% | 77.7% |

| Temporary Seasonal Workers | 85.0% | 81.4% | 83.6% | 81.2% | 75.6% | 85.0% | 84.6% |

| Temporary Non-seasonal Workers | 63.8% | 70.5% | 64.7% | 60.0% | 70.4% | 74.5% | 73.0% |

| Uncategorized Workers | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 |

| Unemployed Who Have Insurable Employment and a Valid Job Separation | 571,781 | 857,186 | 746,009 | 695,331 | 628,836 | 624,123 | 580,546 |

| Permanent Workers |

340,145 (59.5%) |

546,357 (63.7%) |

432,479 (58.0%) |

362,126 (52.1%) |

340,982 (54.2%) |

336,637 (53.9%) |

285,668 (49.2%) |

| Permanent Full-time Workers | 291,875 (51.0%) |

500,683 (58.4%) |

379,353 (50.9%) |

315,310 (45.3%) |

283,644 (45.1%) |

285,670 (45.8%) |

252,351 (43.5%) |

| Permanent Part-time Workers | 40,245 (7.0%) |

39,258 (4.6%) |

45,333 (6.1%) |

41,389 (6.0%) |

54,532 (8.7%) |

47,979 (7.7%) |

27,169 (4.7%) |

| Permanent Workers, Work Hours Unknown | 8,025 (1.4%) |

6,416 (0.7%) |

7,793 (1.0%) |

5,427 (0.8%) |

2,806 (0.4%) |

2,988 (0.5%) |

6,148 (1.1%) |

| Temporary Workers |

224,874 (39.3%) |

305,501 (35.6%) |

309,077 (41.4%) |

322,551 (46.4%) |

287,099 (45.7%) |

283,634 (45.4%) |

281,376 (48.5%) |

| Temporary Seasonal Workers | 102,482 (17.9%) |

135,904 (15.9%) |

125,186 (16.8%) |

127,081 (18.3%) |

115,569 (18.4%) |

122,082 (19.6%) |

114,468 (19.7%) |

| Temporary Non-seasonal Workers | 122,392 (21.4%) |

169,597 (19.8%) |

183,891 (24.7%) |

195,471 (28.1%) |

171,529 (27.3%) |

161,552 (25.9%) |

166,908 (28.8%) |

| Uncategorized Workers | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 | Not available1 |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- 1 Too unreliable to be published.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

In 2013, the eligibility rate increased to 85.8% from 81.9% in 2012, due to a combination of factors. First, the proportion of unemployed permanent full-time workers—whose eligibility rate was 95.0% in 2013—as a share of unemployed workers with insurable employment and a valid job separation, increased by almost a percentage point (from 45.1% to 45.8%) between 2012 and 2013. Second, the number of unemployed who quit their job to go to school increased from 74,200 in 2012 to a recent high of 93,300 in 2013, representing an increase of 25.7%. As previously indicated, unemployed individuals with an invalid job separation are excluded when calculating eligibility rates and the exclusion of this group reduced the pool of unemployed workers who are less likely to have sufficient hours to be eligible for benefits. Finally, the proportion of unemployed temporary seasonal workers as a share of unemployed workers with insurable employment and a valid job separation increased from 18.4% in 2012 to 19.6% in 2013, while their eligibility rate increased from 75.6% to 85.0%. In 2012, the eligibility rate for temporary seasonal workers was lower than usual but returned to a normal level in 2013.

In 2014, the eligibility rate decreased to 83.1% from 85.8% in 2013, due to multiple reasons. First, the proportion of unemployed permanent full-time workers—whose eligibility rate was 90.1% in 2014—as a share of unemployed workers with insurable employment and a valid job separation, decreased from 45.8% in 2013 to 43.5% in 2014, while their eligibility rate decreased by almost 5 percentage points. Secondly, the proportion of unemployed temporary non-seasonal workers—whose eligibility rate was 74.5% in 2014—as a share of unemployed workers with insurable employment and a valid job separation, increased from 25.9% to 28.8% in 2014, while their eligibility rate decreased by 1.5 percentage points. This group has historically had a lower eligibility rate (60-75%), especially compared to permanent full-time workers (90-95%). Finally, there was a decline to the eligibility rate for permanent part-time workers (-5.2 percentage points, from 71.4% in 2013 to 66.2% in 2014).

As mentioned previously, poor economic conditions can result in a large pool of unemployed workers who have accumulated sufficient hours of insurable employment with a valid job separation, and are thus eligible for EI. As a result, higher eligibility rates tend to prevail during an economic slowdown or recession. However, during periods of economic recovery, the eligibility rates tend to decline, while during periods of more stable economic conditions, the eligibility may remain stable or even increase. This paradox highlights the fact that diverse compositions of the unemployed population accumulate varying degrees of hours of insurable employment from year-to-year, which contribute to fluctuations in eligibility rates, as witnessed over the past few years.

A recent study Footnote 38 using the Canada Out-of-Employment Panel (COEP) Survey showed that individuals’ work patterns influence their likelihood of being eligible for EI regular benefits. The study found that full-time permanent job separators had the highest eligibility rate, which can be attributed to having the highest average number of hours of insurable employment. Non-permanent job separators had the lowest eligibility rate, due to fewer hours worked, on average.

Another recent study Footnote 39 , Footnote 40 was conducted based on the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID), in part, to assess the impact of changing working hours on EI eligibility, from 1996 (prior to the January 1997 EI change in the eligibility criteria, from a weeks-based system to an hours-based system) to 2010. The results suggest that, from 1996 to 2010 and among all workers combined, average weekly hours have only changed minimally, fluctuating between 33.5 and 35 hours. The study concluded that the eligibility rate was relatively stable over the past two decades. Due to the differences in hours worked, from 1996 to 2010, full-time workers had a significantly higher eligibility rate compared to those who were not, while youth (aged 16-24) and less educated workers (less than a high school diploma) had lower eligibility rates compared to their older and more educated counterparts.

2.2.2.5 Eligibility for Employment Insurance regular benefits, from records of employment

In addition to the EICS, another source often used to examine the eligibility of individuals for EI regular benefits is the Record of Employments (ROE). A recent evaluation study Footnote 41 was conducted on ROE-Based Measures and EI Eligibility. Footnote 42 The population and methodology used to determine eligibility rates in this ROE study differ from other eligibility measures (e.g. EICS). For example, eligibility rates cited in the ROE study are based on individuals with one or multiple ROEs, regardless if the individuals are unemployed or currently working in another job. In contrast, the EICS eligibility rate is based on the unemployed population that has recently contributed to EI and had a valid job separation. In addition, while the ROE is a form that an employer must issue to an employee leaving a job, regardless of the reason, approximately 30% of job separations have missing ROE forms. As a result, ROE-based eligibility rates may be underestimated since an individual’s complete employment history (i.e. all hours of insurable of employment) is not always taken into consideration, and the rates should be interpreted with caution when compared to other eligibility results, such as the EICS.

In this ROE-based study, the sample was based on 10% of individuals with ROEs submitted between 2001 and 2014. The study examined the percentage of job separators who were laid off due to shortage of work in the previous 52 weeks and who had accumulated enough hours of insurable employment to qualify for EI regular benefits, based on the Variable Entrance Requirement (VER). Based on the VER, individuals living in EI economic regions with high unemployment rates require fewer hours of insurable employment to qualify for benefits than do people in regions with lower unemployment rates.

The study found that regions with high unemployment rates had a larger proportion of job separators with sufficient hours to meet the entrance requirements than did regions with low unemployment rates. In 2014, in regions with an unemployment rate of 13.1% or higher, 83% of job separators with a layoff due to shortage of work accumulated enough hours of work to qualify for EI regular benefits. Conversely, only around 65% of job separators accumulated enough hours of work to qualify for EI regular benefits in regions of lower unemployment (unemployment rate below 8.0%).

In addition, the study determined that 67.1% of all job separators who were laid off due to shortage of work, had enough hours from their combined ROEs to be eligible for EI regular benefits in 2014. From 2001 to 2014, the figure ranged between 67.1% and 72.1%.

2.2.2.6 Eligibility for Employment Insurance regular benefits, among the employed population

A study Footnote 43 , using the Labour Force Survey (LFS), Footnote 44 measured the proportion of employees in Canada who would have had sufficient hours of insurable employment over the qualifying period to meet variable entrance requirements—ranging from 420 to 700 hours Footnote 45 —if all workers had been laid off in the year studied (i.e., during the 12 months of the calendar year).

The LFS-based simulations suggest that 88.5% of individuals who were working as paid employees in 2014 would have been eligible for regular benefits had they lost their job. The LFS-based simulations suggest that the proportion of employed individuals with sufficient hours to claim regular benefits had they lost their job varied only slightly across the country in 2014, ranging from a high of 90.3% in New Brunswick to 86.4% in Alberta. Eligibility rates from the LFS-based simulation are generally higher than those of the EICS because the LFS-based simulation is based on the employed population, which includes participants who likely have more hours of insurable employment compared to the unemployed population.

Men would have had a slightly higher eligibility rate (89.7%) than women (87.2%) had they lost their job in 2014, due to the fact that part-time employment is more common among women. Employed full-time workers would have been eligible to receive regular benefits 93.6% of the time had they lost their job, compared to 61.0% for employed part-time workers. In addition, 91.8% of employed adults (25 to 69 years) would have been eligible to receive regular benefits had they lost their job, compared to 65.5% for youth (19 to 24 years). Employed part-time workers and youth are less likely to qualify for regular benefits because they are less likely to accumulate enough hours of insurable employment over the qualifying period (usually 52 weeks preceding a claim). In addition, employed youth are more likely to be in school, and since they are newer to the labour force, they may face higher entrance requirements (910 hours under the NERE provision Footnote 46 ) to qualify for EI regular benefits.

2.2.3 Accessibility to Employment Insurance regular benefits

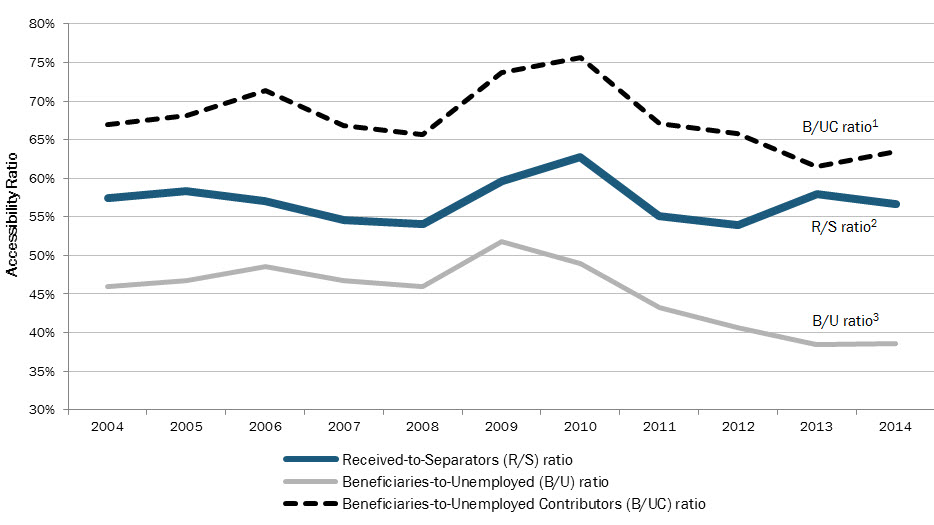

This section analyzes the level of access to EI regular benefits by unemployed individuals with valid job separations. Three measures of accessibility are discussed in this section. The first one is the R/S ratio (for receiving/separation), which is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed individuals who received regular benefits (see Chart 17, bar R) in the EICS reference week by the number of unemployed individuals with insurable employment and a valid job separation (see Chart 17, bar S). The second measure is the B/U ratio (for beneficiaries/unemployed) and is calculated by dividing regular beneficiaries in the LFS reference week by the number of the unemployed individuals (see Chart 17, bar U). The last measure is the B/UC ratio (for beneficiaries/unemployed contributors), calculated by dividing the number of regular beneficiaries in the LFS reference week by the number of unemployed EI contributors (see Chart 17, bar UC).

2.2.3.1 Accessibility to Employment Insurance regular benefits: the R/S ratio

The R/S ratio (see Chart 21, R/S) considers the unemployed population who previously worked and contributed to the EI program and had a valid job separation, while other measures of accessibility are based on a broader unemployed population. The 2014 EICS R/S access ratio was 56.7%, which represents a 1.3 percentage point decrease compared to 2013 (58.0%).

It is important to note that access to regular benefits (R/S) can differ from the eligibility rate (E/S) for a number of reasons: not all eligible persons opt to file a claim for benefits; monies paid on separation can delay immediate payment of benefits; claims that have not yet been established and put into pay; the individual worked while on claim Footnote 47 or returned to work full-time; and an individual’s claim was deemed ineligible due to other factors (e.g., on vacation, out of the country, failure to follow direction).

Similar to the eligibility rate, accessibility to EI regular benefits (R/S) varies by demographics, labour market characteristics and province. The R/S ratio ranged from 46.1% in Alberta to 80.6% in Newfoundland and Labrador in 2014. From 2013 to 2014, the largest increase occurred in Saskatchewan, +15.4 percentage points (from 54.2% to 69.6%), while the largest decreases were witnessed in Nova Scotia, -9.1 percentage points (from 72.0% to 62.9%) and Quebec, -8.2 percentage points (from 63.8% to 55.6%).

In 2014, the R/S ratio for women (57.1%) was slightly higher than that for men (56.6%). Adults (25 years and older) (60.5%), seasonal (65.6%) and permanent full-time workers (56.5%) had among the highest accessibility ratios in 2014. Youth (aged 15 to 24 years) and permanent part-time workers had the lowest accessibility ratios, at 26.5% and 31.1%, respectively.

2.2.3.2 Accessibility to Employment Insurance regular benefits: the B/U ratio Footnote 48

Another measure, the beneficiaries-to-unemployed (B/U) ratio, is often used as an indicator of accessibility to the EI program. The B/U ratio differs from the previously mentioned R/S ratio for a few reasons. First, its numerator (B, total regular beneficiaries in the LFS reference week) includes EI beneficiaries who are not unemployed, such as claimants who received both benefits and earnings in a given week. Footnote 49 Second, its denominator (U, all unemployed) includes many people who are outside of the EI program’s parameters for eligibility to regular benefits (e.g., self-employed Footnote 50 and unpaid family workers; individuals who did not pay EI premiums during the last 12 months; individuals who quit their job to go back to school or who quit their jobs for other reasons without just cause). Third, the B/U ratio is derived from two separate sources, as the numerator (B) comes from Statistics Canada’s monthly EI Statistics release, which is derived from EI administrative data and the denominator (U) comes from Statistics Canada’s Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

As shown in Chart 21, in 2014, the B/U ratio was 38.6%, increasing from 38.4% in 2013. The increase is attributable to the fact that the number of regular beneficiaries (B) decreased in 2014 at a slower rate (-3.4%) compared to the number of unemployed (-4.0%). The recent decline in the B/U ratio (from 51.8% in 2009 to 38.6% in 2014) can be attributed to improving labour market conditions, as the number of regular beneficiaries (B) decreased from 767,900 in 2009 to 486,700 in 2014, representing a decrease of 36.6%. The high number of beneficiaries in 2009 can likely be attributed to a higher number of workers who became unemployed during the recession.

Show Data Table

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received-to-Separators (R/S) ratio | 57.5% | 58.3% | 57.0% | 54.6% | 54.1% | 59.7% | 62.7% | 55.1% | 53.9% | 58.0% | 56.7% |

| Beneficiaries-to-Unemployed (B/U) ratio | 45.9% | 46.7% | 48.5% | 46.8% | 46.0% | 51.8% | 48.9% | 43.2% | 40.6% | 38.4% | 38.6% |

| Beneficiaries-to-Unemployed Contributors (B/UC) ratio | 67.0% | 68.1% | 71.4% | 66.9% | 65.6% | 73.7% | 75.6% | 67.1% | 65.8% | 61.5% | 63.4% |

- 1 The B/UC ratio is calculated as follows: [number regular beneficiaries ÷ number of unemployed who contributed to the Employment Insurance program].

- 2 The R/S ratio is calculated as follows: [number of individuals who received regular benefits ÷ number of unemployed contributors who had a valid job separation].

- 3 The B/U ratio is calculated as follows: [number of regular beneficiaries ÷ number of unemployed].

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (for data on those who received regular benefits (R), unemployed contributors who had a valid job separation (S), the unemployed (U), and unemployed contributors (UC)); and Statistics Canada, monthly Employment Insurance statistics release, CANSIM table 276-0020 (for data on regular beneficiaries (B)).

Other factors, including increases in the proportion of the unemployed who are outside of EI program parameters, can help explain the recent drop in the B/U ratio. As illustrated in Chart 22, 42.2% of the unemployed were outside of EI program parameters in 2009.

Since then, this proportion has increased each year, reaching a high of 53.9% in 2014. For example, the proportion of individuals who quit their job to go to school as a proportion of the total unemployed increased from 5.8% in 2009 to 7.7% in 2014, an increase of 11,000. More striking, the number of individuals who did not work in the previous 12 months as a proportion of the total unemployed population has increased from 24.8% in 2009 to 34.7% in 2014, an increase of 68,600 during this period. By definition, unemployed individuals who did not work in the previous 12 months have not paid EI premiums, and therefore, cannot become a regular beneficiary. It is therefore not surprising that the recent increases in the proportion of unemployed individuals who are outside of the EI program parameters (from 42.2% in 2009 to 53.9% in 2014), have had a large influence on the recent decreases to the B/U ratio.

Show Data Table

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Unemployed | 1,094,600 | 1,483,000 | 1,410,200 | 1,344,700 | 1,309,700 | 1,312,300 | 1,259,500 |

| Self-employed* and unpaid family workers | 48,500 | 73,000 | 42,000 | 45,600 | 57,400 | 58,900 | 54,900 |

| Did not work in previous 12 months | 279,000 | 368,000 | 455,700 | 432,400 | 443,900 | 433,700 | 436,600 |

| Quit without just cause, to go to school | 76,200 | 85,700 | 83,800 | 71,400 | 74,200 | 93,300 | 96,700 |

| Quit without just cause, other reasons | 119,100 | 99,100 | 82,700 | 100,000 | 105,300 | 102,300 | 90,700 |

| Insurable employment and valid job separation | 571,800 | 857,200 | 746,000 | 695,300 | 628,800 | 624,100 | 580,500 |

| Unemployed, outside of EI program parameters (for regular benefits) | 47.8% | 42.2% | 47.1% | 48.3% | 52.0% | 52.4% | 53.9% |

| Unemployed, potentially eligible for EI regular benefits | 52.2% | 57.8% | 52.9% | 51.7% | 48.0% | 47.6% | 46.1% |

- Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

- * Self-employed individuals can opt in and subsequently pay EI premiums for special benefits (see chapter II, section 4), but they are not eligible for regular benefits.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Employment Insurance Coverage Survey.

2.2.3.3 Accessibility to Employment Insurance regular benefits: the B/UC ratio Footnote 51

A third measure, the beneficiaries-to-unemployed contributors (B/UC) ratio, is a modification of the B/U ratio in which the total number of unemployed individuals is replaced by the number of unemployed individuals who had paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months. The B/UC ratio’s denominator includes all unemployed individuals who paid premiums, which comprises individuals who had either i) a valid job separation, or ii) an invalid job separation (e.g., those who quit their job to return to school or quit for other reasons without a just cause).

The B/UC ratio reached a recent high of 75.6% in 2010, then decreased each year until 2013 (61.5%), before increasing in 2014 (63.4%). The increase in the 2014 B/UC ratio (+1.9 percentage point) is attributed to the fact that the decrease in beneficiaries (-3.4%) was outpaced by the decrease in unemployed contributors (-4.0%).

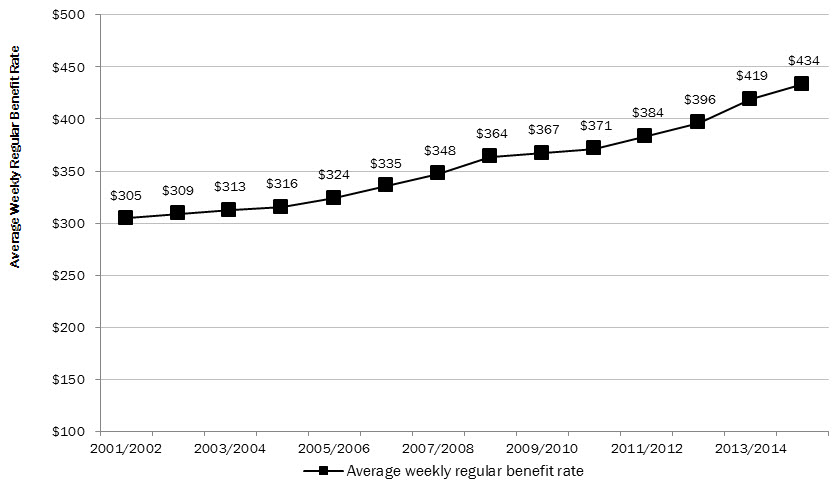

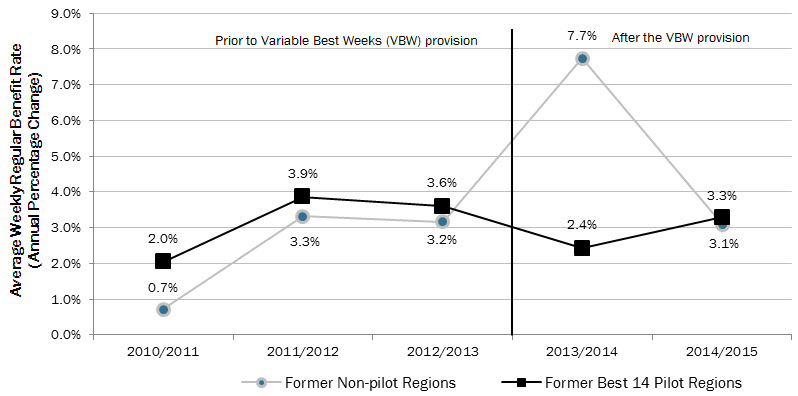

2.3 Level of Employment Insurance regular benefits

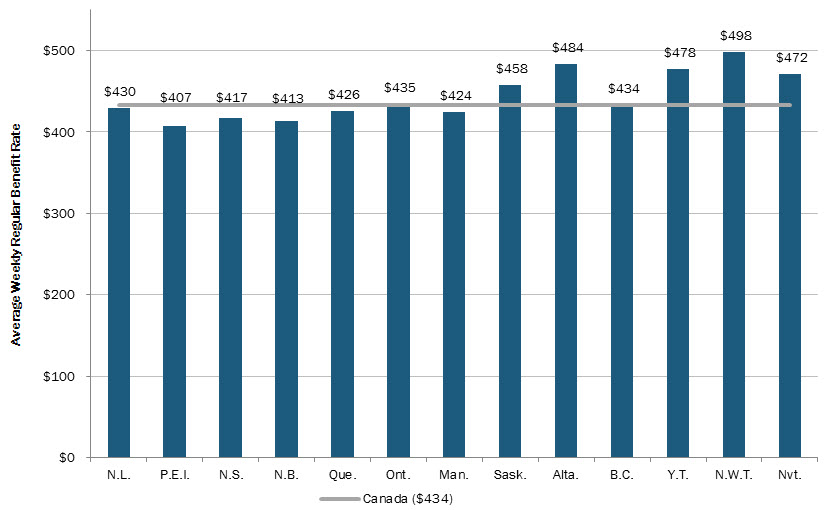

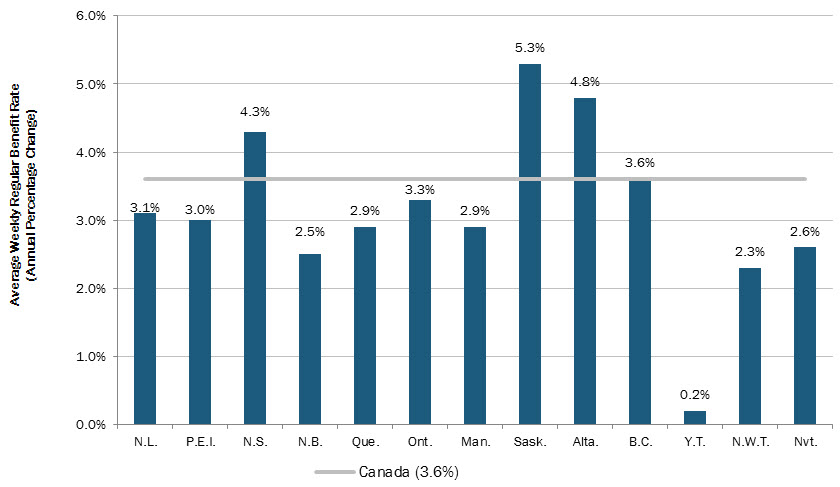

The level of EI regular benefits (i.e., the weekly regular benefit rate) that an EI claimant is entitled to receive is calculated by taking 55% of their highest (best) weeks of insurable earnings in the 52-week qualifying period before their claim is established (or the time since the start of their last claim, whichever is shorter) up to the maximum weekly benefit rate. Under the Employment Insurance Act, the maximum weekly benefit rate that an EI claimant is entitled to receive is directly linked to the maximum insurable earnings threshold (MIE). Footnote 52 The MIE is the income level up to which EI premiums are paid and reflects average weekly earnings from the year before (AWE). Footnote 53 The MIE was $47,400 in 2013, $48,600 in 2014, and $49,500 in 2015. Accordingly, the maximum weekly benefit was $501 in 2013, $514 in 2014 and $524 in 2015.