Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2016 and ending March 31, 2017

Chapter III: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and Support Measures

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

On this page

- 1. National overview

- 2. Provincial and territorial EBSM activities

- 3. Evaluation of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSM)

- 4. Pan-Canadian activities and the national employment service

Activities delivered under Part II of the Employment Insurance (EI) Act help unemployed individuals in Canada prepare for, find and maintain suitable employment. Under the umbrella of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs), these activities include programs delivered by provinces and territories under Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), as well as the Government of Canada's pan-Canadian programming and functions of the National Employment Service (NES).

This chapter presents EBSM program results achieved under Part II of the EI Act during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2016 and ending on March 31, 2017 (FY1617). A national overview of EBSM-similar programming delivered under the LMDAs and by Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS) agreement holders is provided in Section I, entitled “National Overview.” Provincial and territorial employment programming activities are presented in Section II, “Provincial and Territorial Summaries,” with a description of each jurisdiction's labour market and employment priorities. Section III presents consolidated findings and conclusions as part of the 2012-2017 second cycle of LMDA evaluations and an overview of effects of LMDAs on the well-being of active EI claimants in Part II programming. Section IV discusses the results of Employment and Social Development Canada's (ESDC) delivery of pan-Canadian activities, and the administration of certain NES functions.

Notes to readers

- The data used to analyze EBSM activities were collected from provinces, territories and ASETS agreement holders. Governments continue to improve data quality and collection to ensure accurate, reliable and consistent information. While all data sets are verified before publication, systems and operational changes may affect the comparability of data from year to year.

- Throughout this chapter, references to average levels of activity and to highs and lows generally use the 10-year period from FY0607 to FY1617 as a frame of reference.

- Statistics Canada's Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the source of labour market data reported. Data for Canada and the provinces are fiscal-year averages, calculated using seasonally unadjusted monthly data, while monthly references are seasonally adjusted. Data for the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut are calculated using unadjusted three-month moving averages of monthly data. In discussions of employment trends by industry, standard industry titles are taken from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

- Real GDP data and other non LFS macroeconomic indicators are from Statistics Canada's Economic accounts. Forecasts are based on published analysis from the Bank of Canada, the Conference Board of Canada, Canadian banks, OECD and Statistics Canada, as well as on internal analysis, using information available as of February 2018.

1. National overview

1.1 Economic and labour market context

In FY1617, Canada's labour force grew by 0.8% to a total of 19.6 million, compared to FY1516. Over the same period, total employment grew at a faster pace (+1.0%), with 174,000 additional workers year over year, to a total of 18.2 million. Women accounted for nearly two-thirds of the employment increases, mostly in full-time work. Among men, part-time jobs grew by 6.6%, whereas their full-time employment edged down by 0.2%.

2016/2017 Employment Benefits and Support Measures

| EI active & former clients (LMDA) | Non-insured clients (LMDA) | Pan-Canadian1 |

|---|---|---|

429,382 |

304,927 |

17,563 |

| Active | Former | Non-insured |

46.7% |

12.7% |

40.6% |

| Youth (15–24)2 |

Core Age (25–54)2 |

Older Workers (55+)2 |

20.4% |

66.7% |

12.9% |

| FY1617 | Year-over-year change | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 147,054 | +0.4% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 999,844 | +1.0% |

| Pan-Canadian | 31,744 | +0.8% |

| FY1617 | Year-over-year change (p.p.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 12.8% | 0.1 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 87.1% | 0.1 |

| FY1617 ($ million) |

Year-over-year change | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $1,071 | -4.9 |

| Support Measures: EAS | $714.5 | +22.3% |

| LMPs and R&I | $282.4 | +21.9% |

| Pan-Canadian | $114.1 | +1.4% |

| Total expenditures | $2,181.7 | +6.2% |

| Indicator | Total | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Active claimants served | 351,362 | -1.5% |

| Returns to employment | 187,172 | +4.8% |

| Estimated unpaid benefits ($ million) |

$1,345.00 | +16.6% |

- 1 EI Part II Pan-Canadian services to individuals are through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy.

- 2 Age distribution does not equal 100%, as the “unknown” category is not reported here. Date of birth is not collected for clients in SD-Apprentices and Group Services.

- 3 Totals may not add up exactly due to rounding; accounting adjustments are not included.

In FY1617, Canada's unemployment rate was 6.9%, sliding down by 0.1 percentage points over the previous year. The unemployment rate for youth (aged 15-24 years old) was 13%, which was considerably higher than among core-age workers (25 to 54 years old) and workers aged 55 and older, whose unemployment rates were 5.8% and 6.0%, respectively.

Canada's labour market participation rate in FY1617 was 65.7%, a decline of 0.2 percentage points compared to FY1516. In the context of an aging population, Canada's labour market participation rate steadily declined over the last decade, with proportionally fewer new workers to replace retirees.

According to Statistics Canada's Business Payroll Survey, Canadian businesses reported an average of 218,000 job vacancies in FY1617, a 2.6% drop compared to the previous yearFootnote 1. The number of unemployed workers across Canada dropped to 1.35 million (-0.3%) in the current year, compared to 1.36 million in FY1516Footnote 2. Labour market tightness is often assessed using the unemployment-to-job vacancies (U/V) ratio (number of unemployed people for every vacant position). In FY1617, for every job vacancy, 6.2 individuals sought employment, compared to 6.1 a year earlier. This suggests labour market tightness in FY1617 remained unchanged year-over-year.

In 2016, Canada's real GDP expanded by 1.4%, with growth in most regions of the country. Strong growth in Yukon (+8.0%), British Columbia (+3.5%), Ontario (+2.6%), Prince Edward Island (+2.3%), and Manitoba (+2.2%) were offset by real GDP declines in Alberta (-3.7%) and Saskatchewan (-0.5%), where low oil and commodity prices continued to negatively impact the economy of the two provinces.

In 2017, Canada's real GDP is estimated to have grown by 3.0%, largely driven by increased consumption and business fixed investmentsFootnote 3. The OECD estimates that Canada's real GDP growth in 2017 was the strongest among G-7 countries for the year.

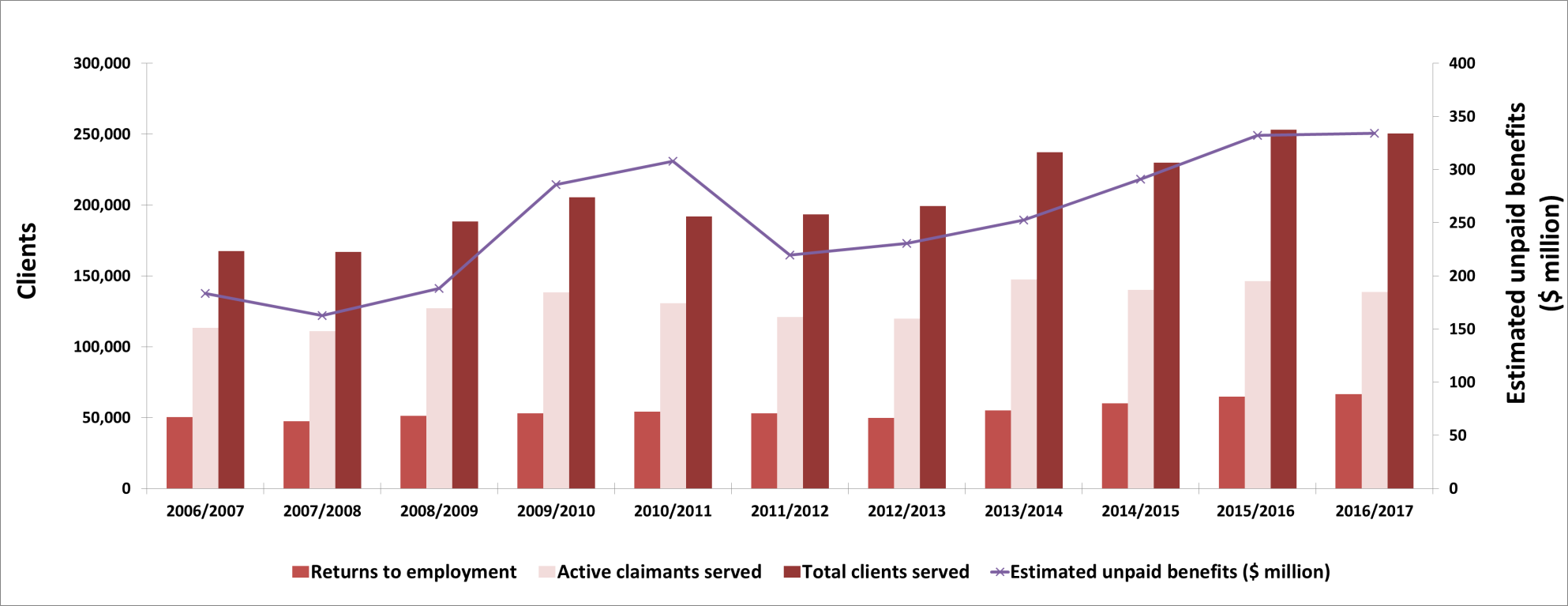

1.2 Main resultsFootnote 4

Increase in the number of clients and interventionsFootnote 5

Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories served 734,309 clients, increasing by 2.3% compared to the previous year. Corresponding with the increase in clients served, LMDA interventions totalled 1,146,898, edging up by 0.9% year-over-year. Overall, Employment Benefit interventions remained stable (+0.4%), while Support Measures interventions, jumped by 1.0% year-over-year. In the context of improving economic and labour market conditions, the additional $125 million in LMDA funding in FY1617 (see Section 3.1.6 for expenditures details), enabled provinces and territories to deliver more programming to clients.

Terminology guide

A client is a person who has participated in programs or services that are funded by the LMDAs or by Indigenous organizations. See section 3.1.3 for details for client types.

An intervention is a discrete program or service that a client participates in. See Section 3.1.4 for the type of interventions available to clients.

Any reference to participants in this chapter is equal to the number of interventions, particularly in Section 3.1.3 where information on designated groups is only collected at the intervention level.

With the extra funding for LMDAs and strong growth of the national economy, provinces and territories were able to improve their outcomes for clients, as the number of EI clientsFootnote 6 returning to employment after participation (187,172), increased by 4.8%, year-over-year. Stronger returns to work contributed to higher unpaid EI Part I benefits ($1.345 billion), which increased by 16.6%, year-over-year.

Combined with labour market programming delivered by Indigenous organizations (details below), a total of 751,872 clients were served (+2.4%), and 1,178,642 EBSM interventions (+0.9%) were delivered in FY1617.

Programming for Indigenous clients continues to grow

In FY1617, Indigenous organizations served 17,563 clients under Pan-Canadian programming, compared to 16,228 clients in the previous year, increasing by 8.2%. The number of interventions increased as well; edging up slightly by 0.8% year-over-year, to a total of 31,744.

Over the last ten years, the number of clients served by Indigenous organizations rose by 9.5%, and the number of interventions being delivered jumped significantly, by 74.1%. The increase in the number of interventions, coupled with the slower increase in the number of clients, suggests that Indigenous clients receive longer-term interventions, usually through training services and various interventions, compared to FY0607. For every client in FY1617, there were 1.80 interventions, compared to 1.1 interventions ten years ago.

Expenditures and length of interventions (2016/2017)

Show Data Table

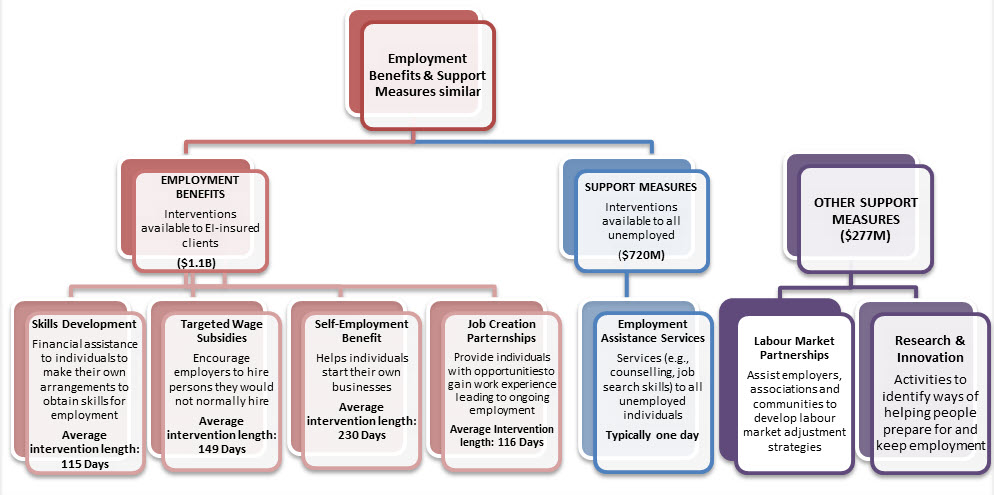

- Employment Benefits & Support Measures similar

- Employment Benefits

Interventions available to EI-insured clients ($1.1B)- Skills Development

Financial assistance to individuals to make their own arrangements to obtain skills for employment

Average intervention length: 115 Days - Targeted Wage Subsidies

Encourage employers to hire persons they would not normally hire

Average intervention length: 149 Days - Self-Employment Benefit

Helps individuals start their own businesses

Average intervention length: 230 Days - Job Creation Parternships

Provide individuals with opportunities to gain work experience leading to ongoing employment

Average Intervention length: 116 Days

- Skills Development

- Support Measures

Interventions available to all unemployed ($720M)- Employment Assistance Services

Services (e.g., counselling, job search skills) to all unemployed individuals. Typically one day

- Employment Assistance Services

- Employment Benefits

- Other Support Measures ($277M)

- Labour Market Partnerships

Assist employers, associations and communities to develop labour market adjustment strategies - Research & Innovation

Activities to identify ways of helping people prepare for and keep employment

- Labour Market Partnerships

1.3 Client profile and participation

Client types

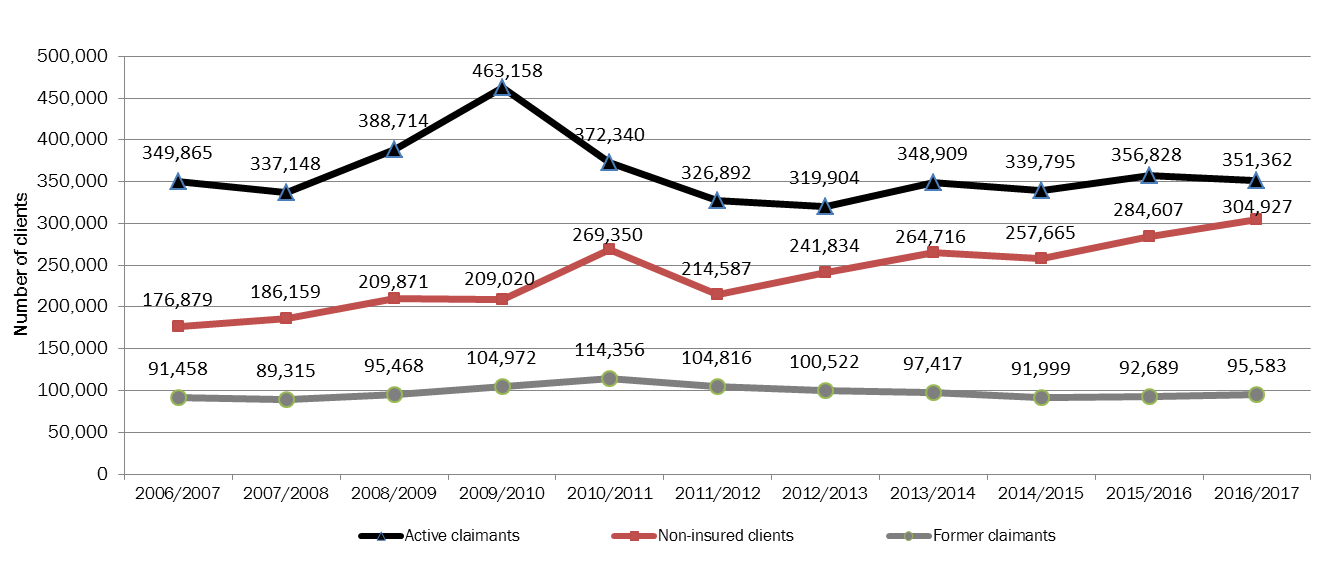

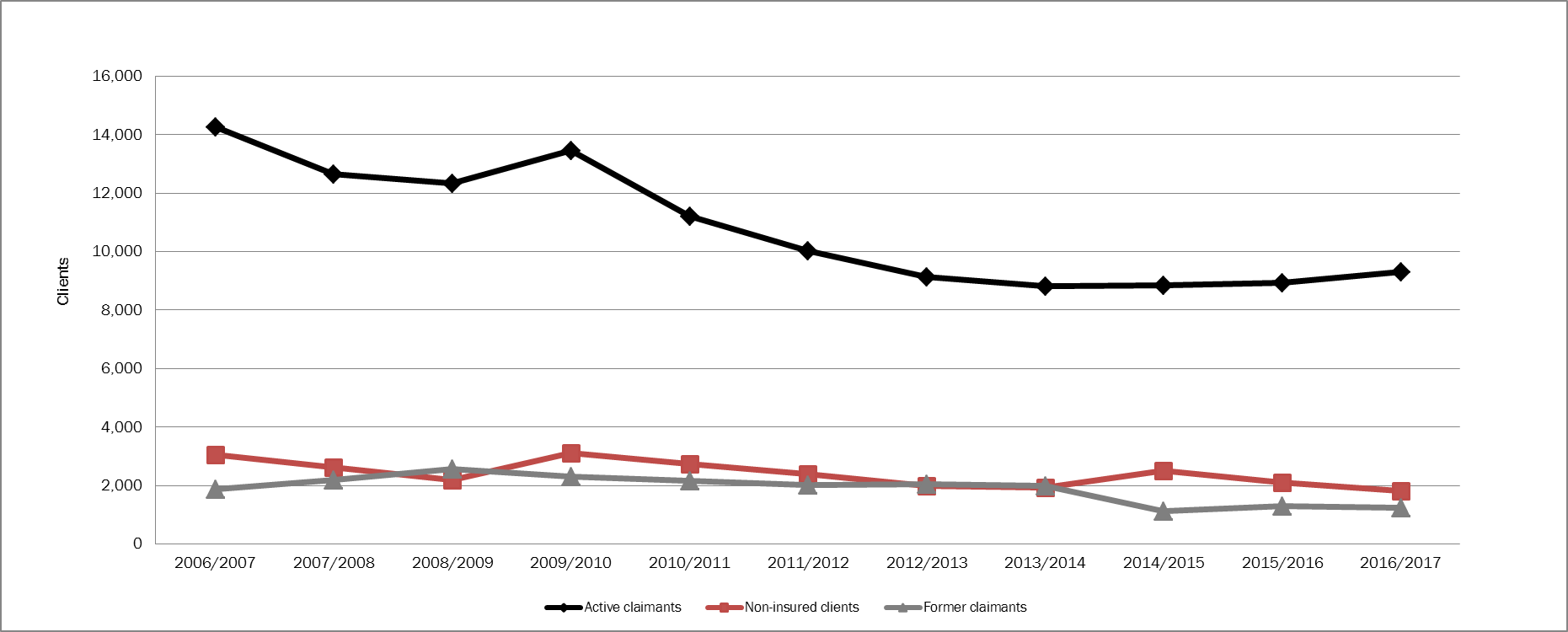

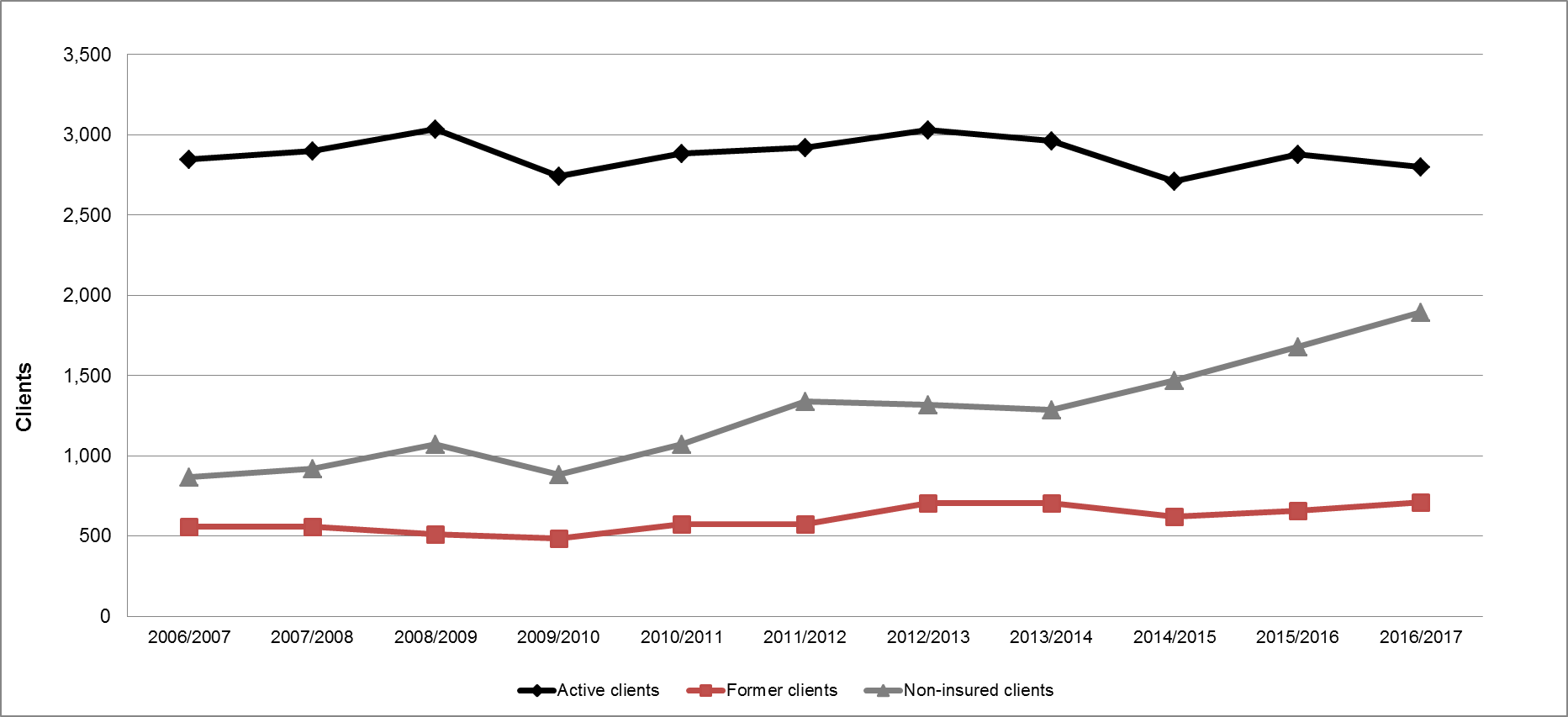

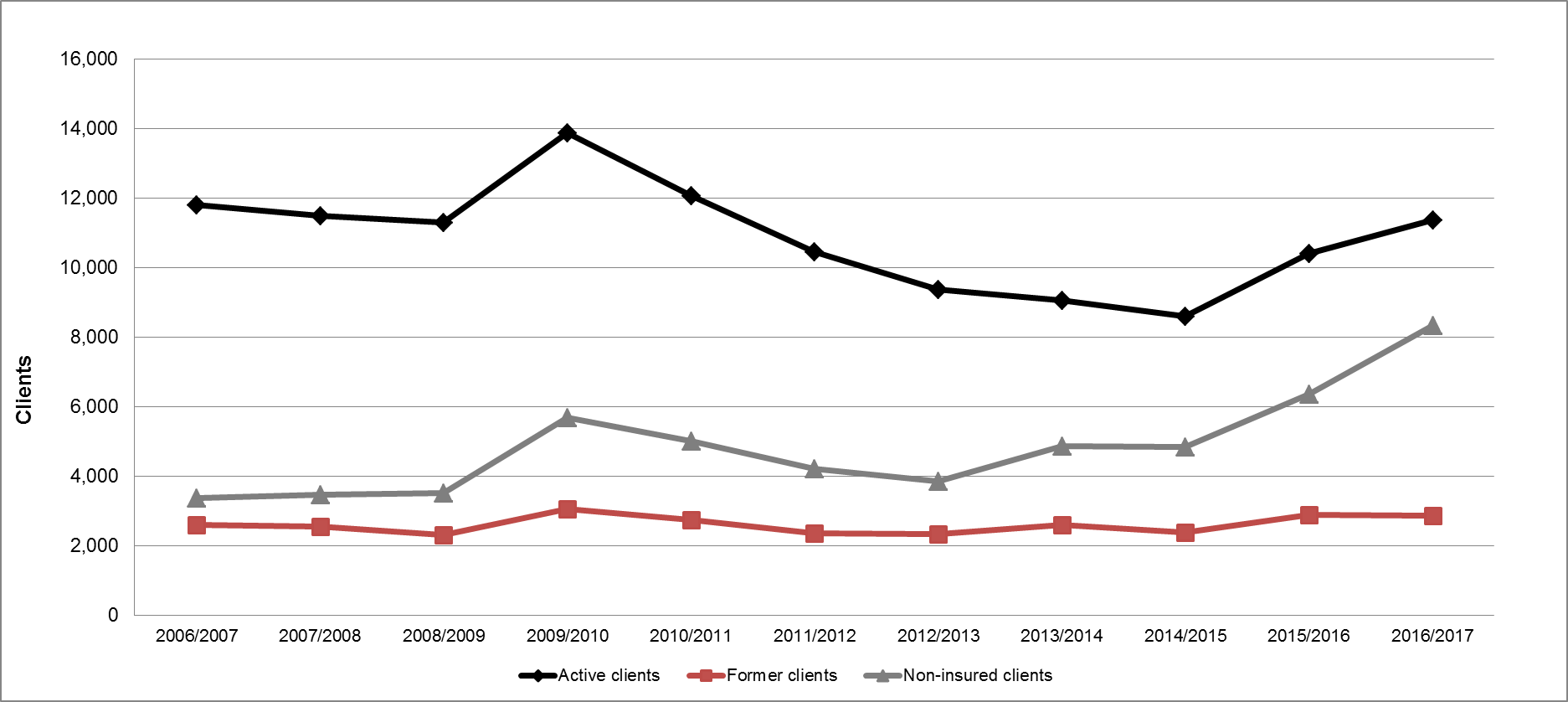

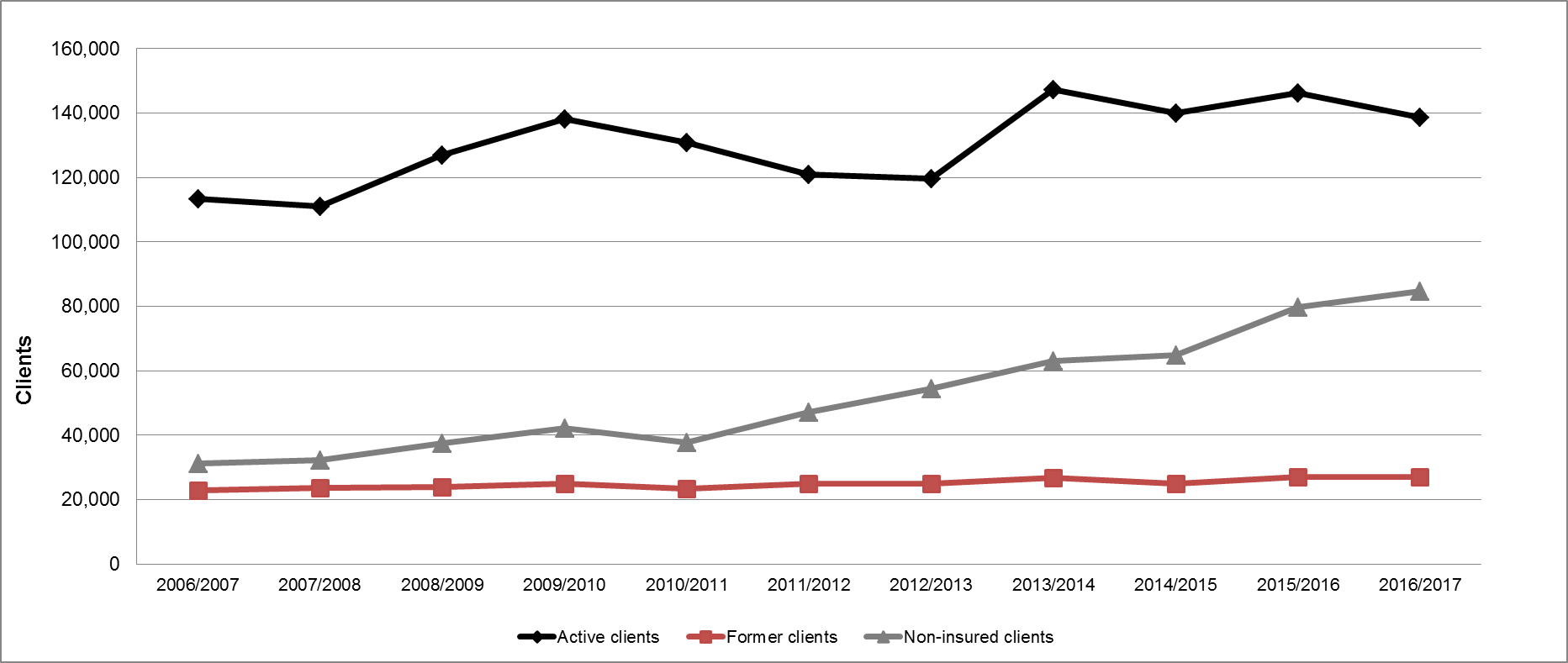

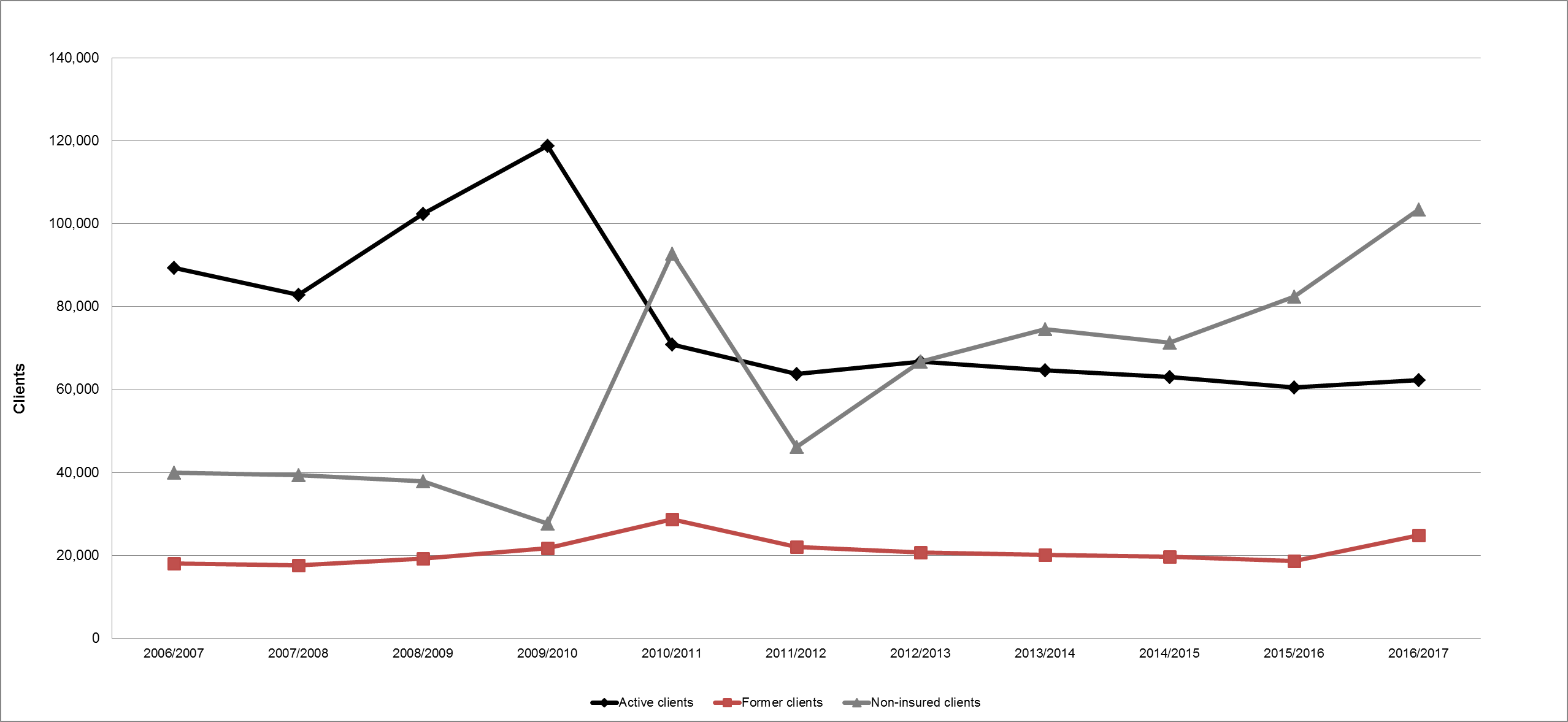

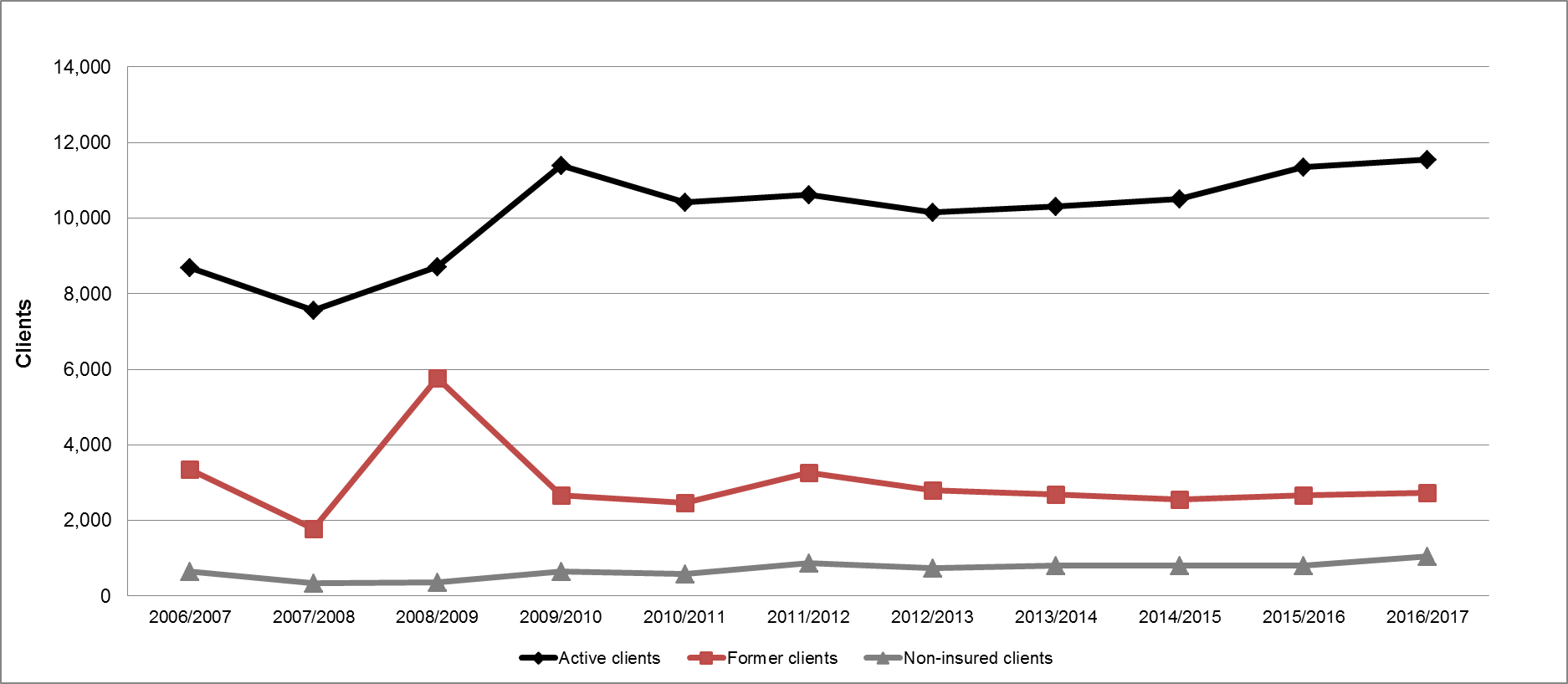

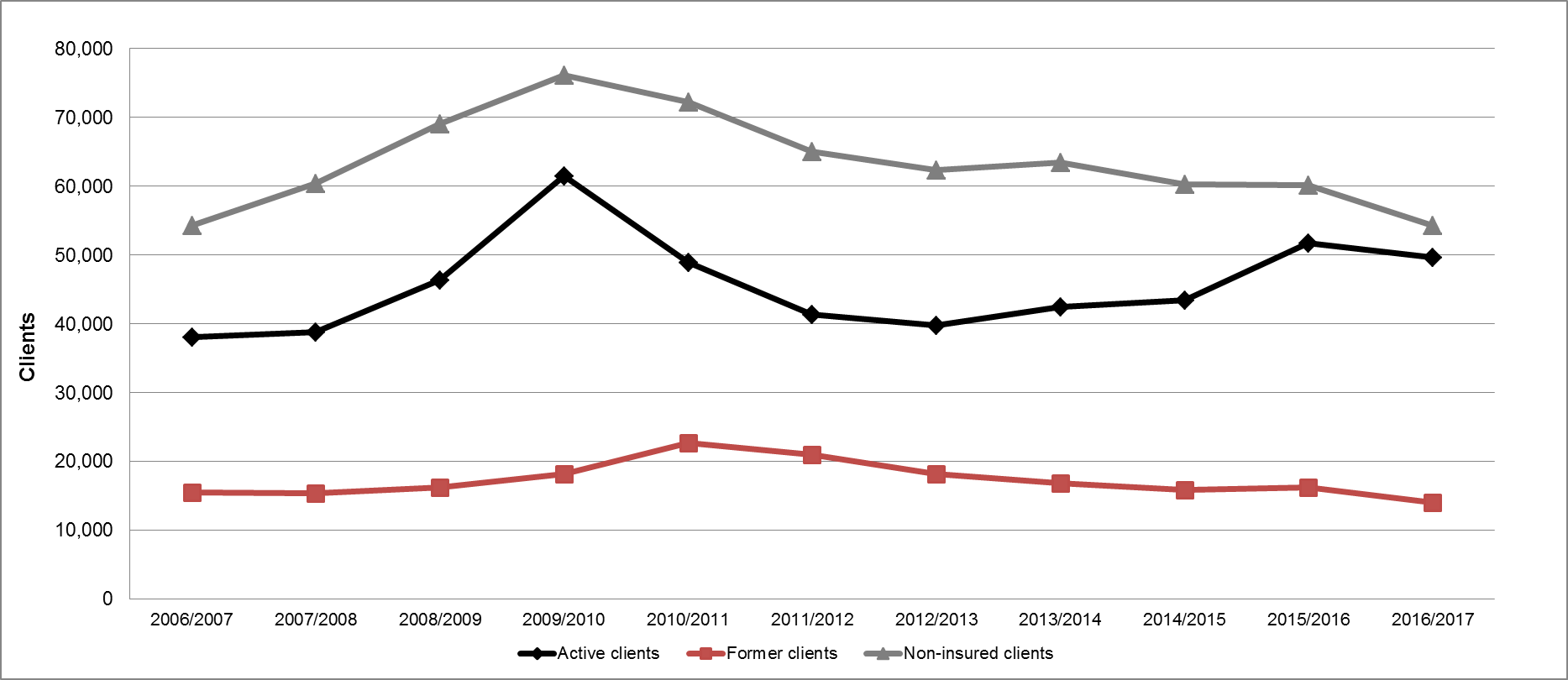

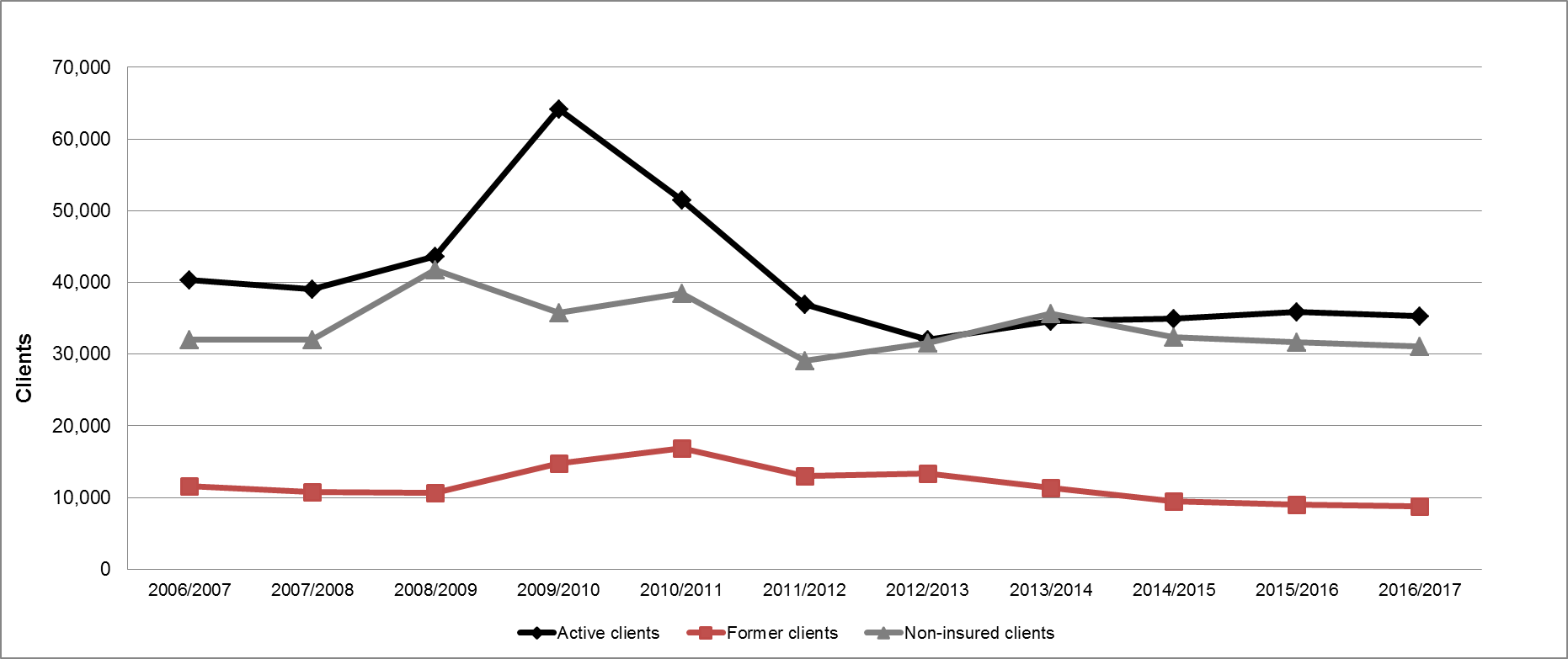

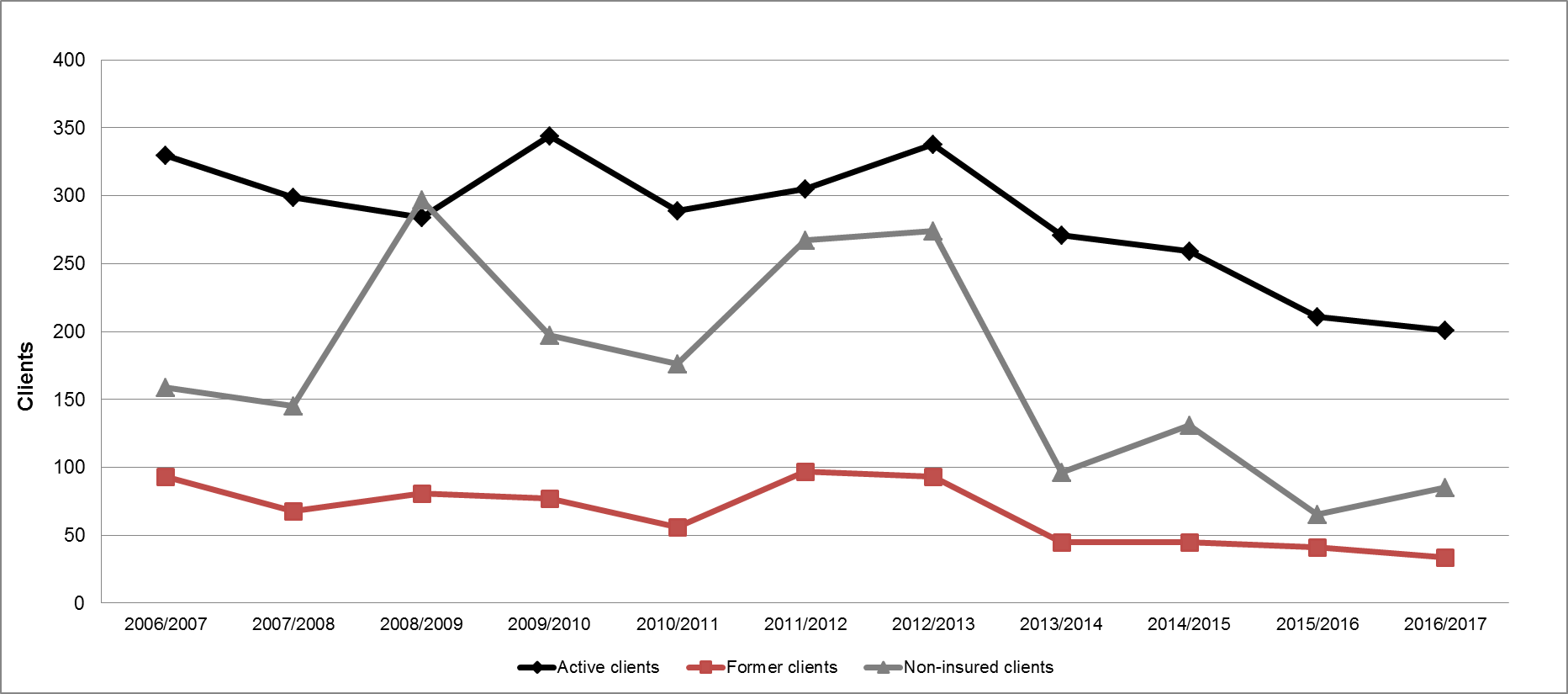

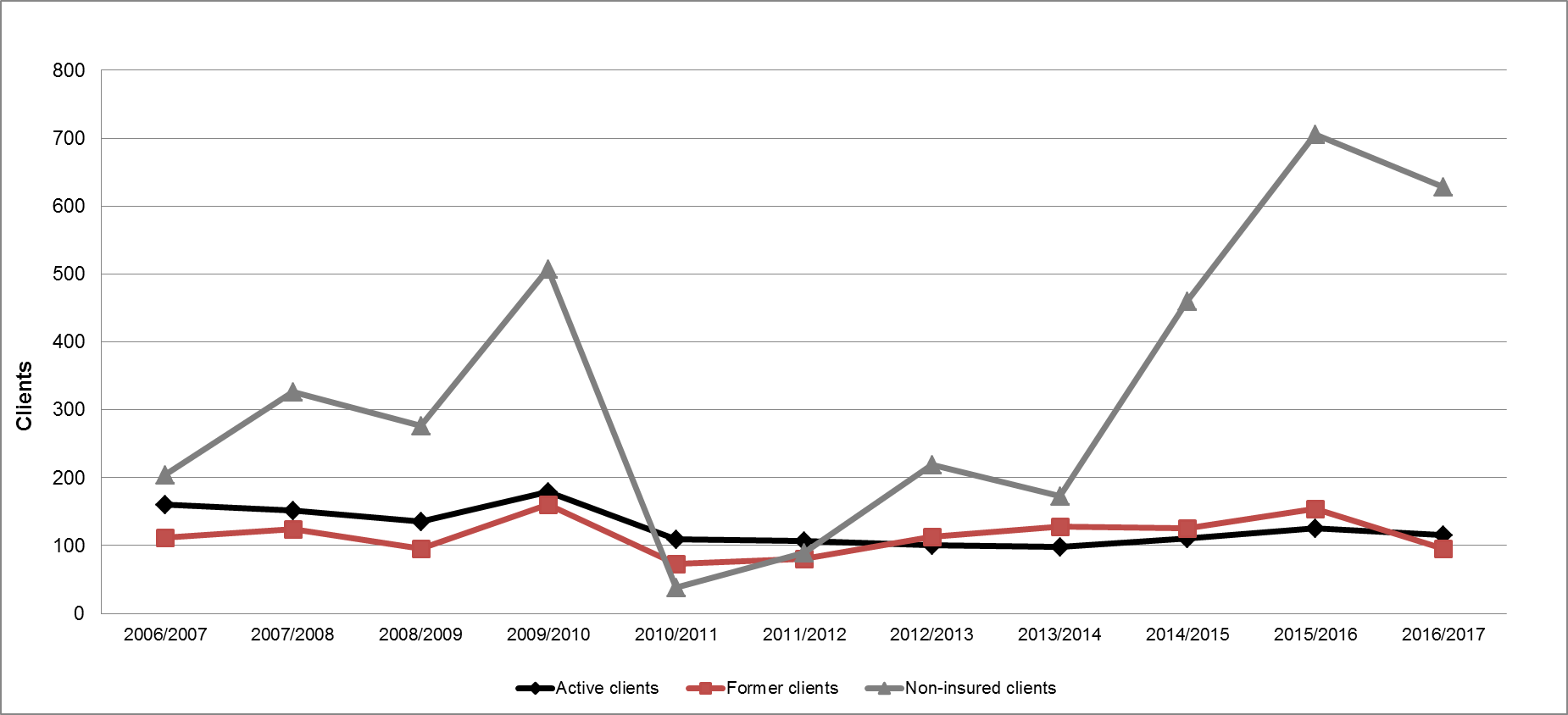

EI active claimants declined and former claimants and non-insured clients increased in FY1617

The overall number of clients increased in FY1617, with former claimants and non-insured clients edging up by 3.1% and 7.1%, respectively. At the same time, active claimants dropped by 1.5%.

Active claimants are those who had an active EI Part I regular claim when they requested assistance under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. Typically, they have stronger and more recent job attachment. They tend to be able to return to work more quickly than those with weaker ties to employment. Active claimants who are considered job-ready from an analytical point of view often seek out short-term interventions under EI Part II to find their next employment opportunity. Others require longer-term Employment Benefits to upgrade their skills, establish certification or refine their job search strategies.

In FY1617, the number of active claimants served by provinces, territories and Indigenous organizations dropped by 1.5%, to a total of 351,362. Active claimants represented 46.7% of all clients, compared to 48.6% of all clients in FY1516.

Former claimants are those who completed an EI claim in the previous three yearsFootnote 7, or who began a parental or maternity claim in the last five years when they requested assistance under Part II. They are no longer eligible for EI Part I; however, they remain eligible for EI Part II under certain criteria.Footnote 8 Former claimants do not receive income support under Part I of the Employment Insurance Act while they complete an Employment Benefit intervention; however, they may receive Part II support while completing their return-to-work action plan.

In FY1617, the number of former claimants increased to a total of 95,583 clients (+3.1%). Coinciding with this increase, the share of former claimants edged up to 12.7%, compared to 12.6% in the previous year.

Non-insured clients are unemployed individuals who are neither active nor former EI clients. Non-insured clients usually have little substantive or recent job attachment. They include new labour force participants and individuals who were formerly self-employed without paid employment earnings. While these clients are not eligible for Employment Benefits under EI Part II, they may access interventions similar to Employment Assistance Services.

In FY1617, the numbers of non-insured clients increased sharply by 7.1%, to a total 304,927 from 284,607 a year earlier. In turn, the share of non-insured clients edged down from 38.8% to 40.6% in the current year.

Total non-insured clients increased in the last decade

Overall, provinces, territories and Indigenous organizations have been serving more clients (+21.6%) since FY0607, with a pronounced growth in the number of non-insured clients (+72.4%), while active (+0.4%) and former EI claimant counts (+4.5%) increased at a slower pace.

Show Data Table

| Active claimants | Non-insured clients | Former claimants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 349,865 | 176,879 | 91,458 |

| 2007-2008 | 337,148 | 186,159 | 89,315 |

| 2008-2009 | 388,714 | 209,871 | 95,468 |

| 2009-2010 | 463,158 | 209,020 | 104,972 |

| 2010-2011 | 372,340 | 269,350 | 114,356 |

| 2011-2012 | 326,892 | 214,587 | 104,816 |

| 2012-2013 | 319,904 | 241,834 | 100,522 |

| 2013-2014 | 348,909 | 264,716 | 97,417 |

| 2014/2015 | 339,795 | 257,665 | 91,999 |

| 2015-2016 | 356,828 | 284,607 | 92,689 |

| 2016-2017 | 351,362 | 304,927 | 95,583 |

In turn, the growing number of total non-insured clients served by provinces, territories, and Indigenous organizations means their share among all EBSM client-types has jumped from 28.6% in FY0607, to 40.6% in the current year. Active claimants, who represented 56.6% of all clients a decade ago, now represent 46.7% of all clients in FY1617.

Patterns of working Canadians evolving alongside social and economic changes

According to the 2016 Census results, the period from 2005 to 2015 saw a shift from full-time, full-year employment toward part-time or part-year work. The shift is related to a combination of social and economic changes, such as the 2008 to 2009 financial crisis and automation technologies.

From 2006 to 2016, the employment rate fell from 62.6% to 60.2%.

Fewer men aged 25 to 54 are now working full-time all year. In 2015, 56.2% of men aged 25 to 54 years old worked full-time all year, down from 63.3% a decade earlier. The 2015 proportion is the lowest since 1980. The proportion of women in this age group who worked full-time all year has also declined: 43.7% in 2015 compared to 46.4% in 2005.

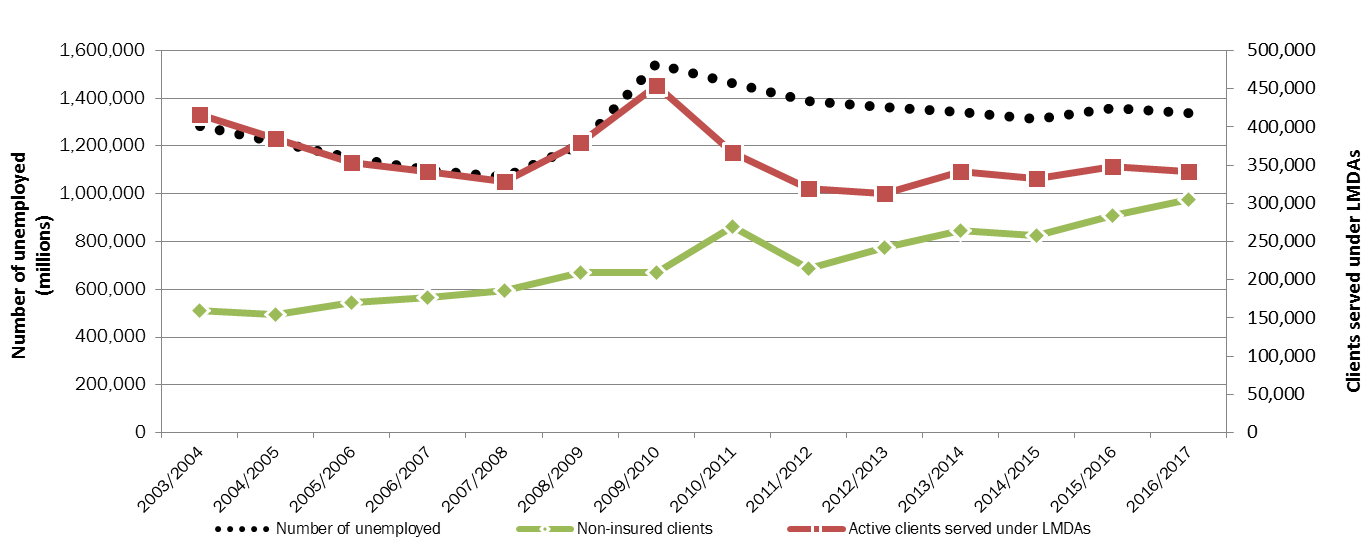

In the years prior to the 2008 to 2009 recession, the number of unemployed Canadians and active EI clients served by provinces and territories moved in similar patterns. Following the recession, provinces and territories increasingly reached out to all unemployed individuals, resulting in a spike of non-insured clients (see chart 2). Coming out of the recession, these individuals were probably less likely to qualify for EI regular benefits and entered LMDA programming as non-insured clients. Since then, the number of non-insured clients continues to steadily increase, while active clients have dropped. In the context of static LMDA funding over the years, up until 2015 to 2016, provinces and territories shifted towards serving non-insured clients, a group that is eligible only for Employment Assistance Services. These interventions are less expensive and focus on maximizing returns to work.

The growing number of non-insured clients reflects changing labour market conditions, where temporary, non-standard, and part-time employment is more prevalent (see box for details). These changing employment patterns impact the types of clients that provinces and territories serve, as evidenced by the growth in non-insured clients.

Show Data Table

| Non-insured clients | Active clients served under LMDAs | Number of unemployed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003/2004 | 159,112 | 416,426 | 1,283,400 |

| 2004/2005 | 153,987 | 385,213 | 1,217,300 |

| 2005/2006 | 170,714 | 353,542 | 1,149,100 |

| 2006-2007 | 176,879 | 342,145 | 1,099,400 |

| 2007-2008 | 186,159 | 329,127 | 1,071,000 |

| 2008-2009 | 209,871 | 380,181 | 1,205,400 |

| 2009-2010 | 209,020 | 453,781 | 1,544,400 |

| 2010-2011 | 269,350 | 365,978 | 1,463,000 |

| 2011-2012 | 214,587 | 320,006 | 1,387,400 |

| 2012-2013 | 241,834 | 312,553 | 1,362,400 |

| 2013-2014 | 264,716 | 341,358 | 1,343,300 |

| 2014/2015 | 257,665 | 332,099 | 1,312,700 |

| 2015-2016 | 284,607 | 348,392 | 1,357,300 |

| 2016-2017 | 304,927 | 341,262 | 1,338,500 |

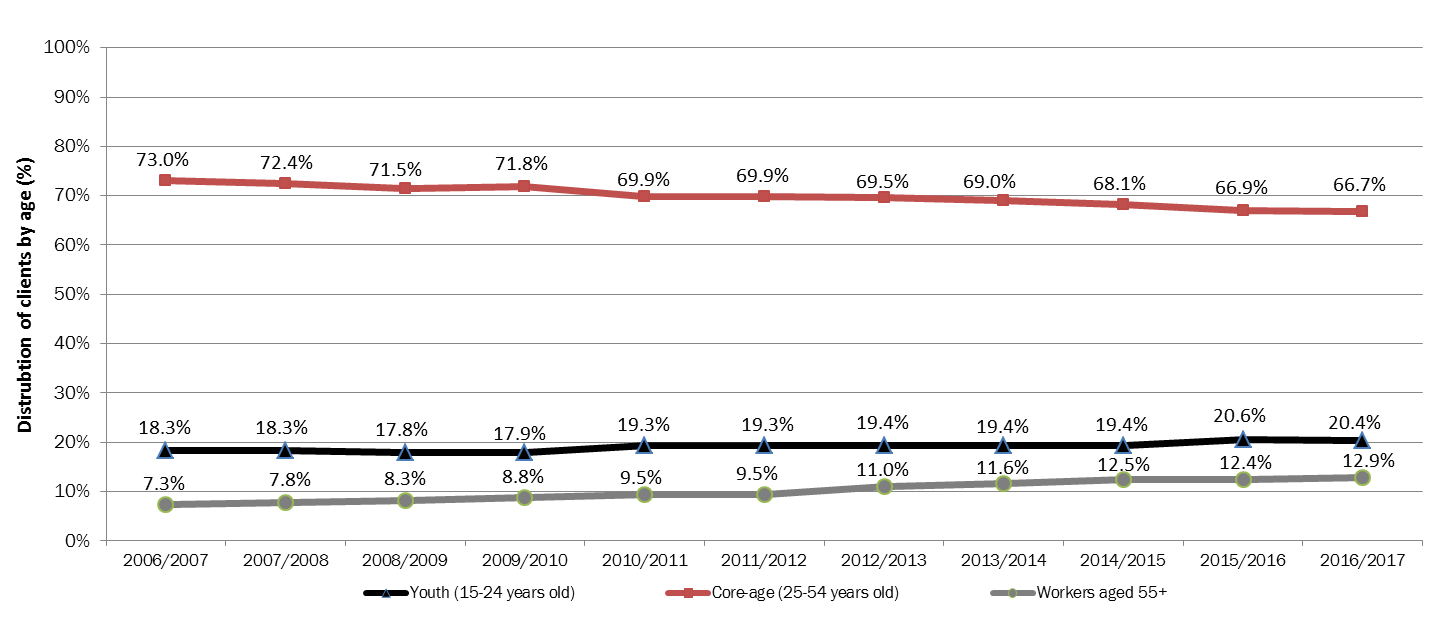

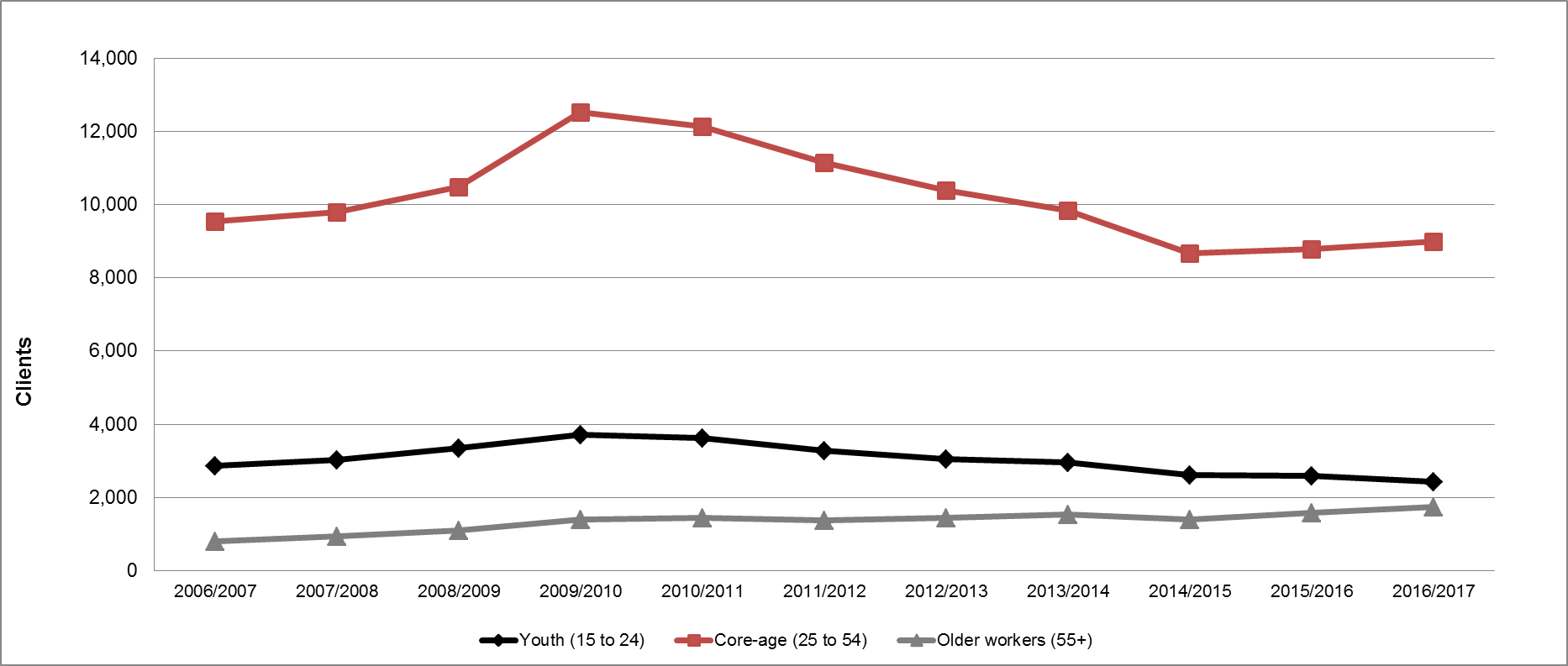

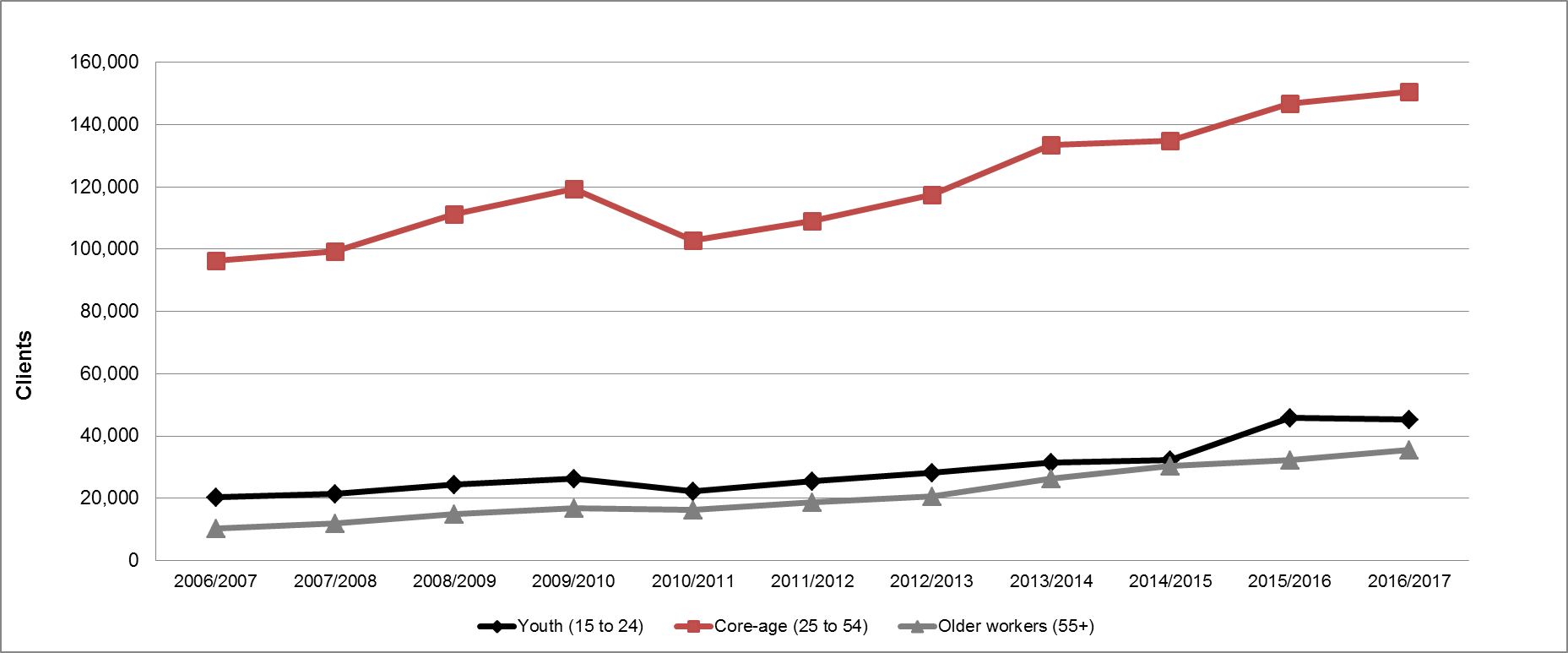

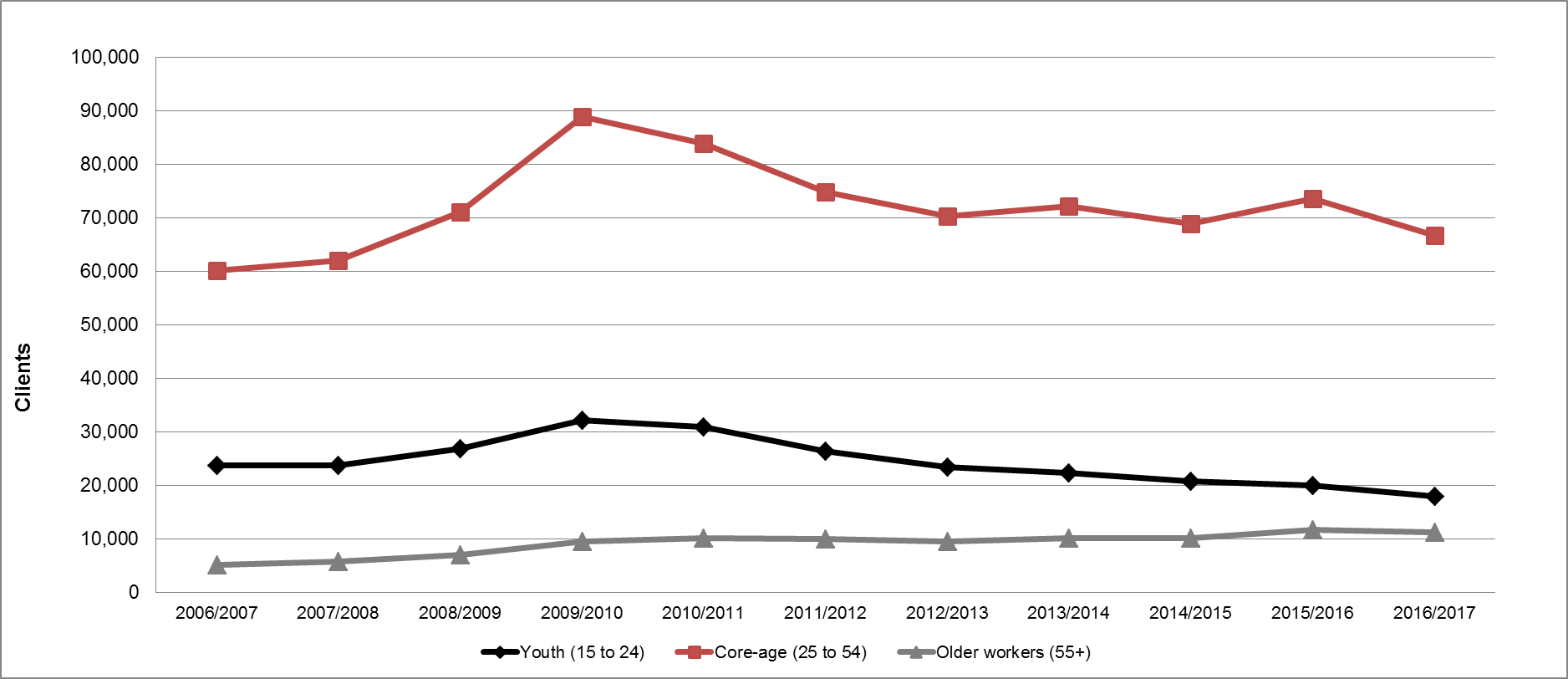

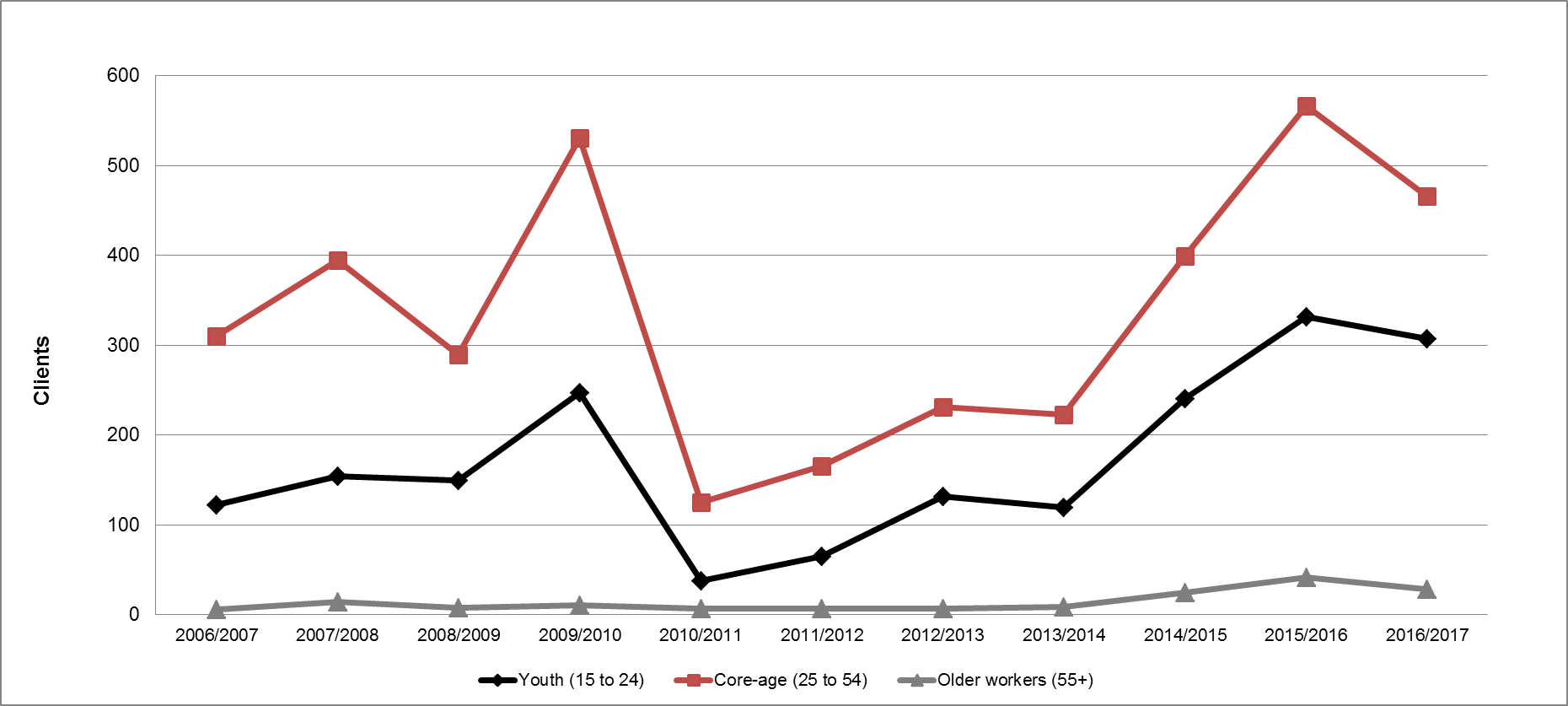

Age distributionFootnote 9

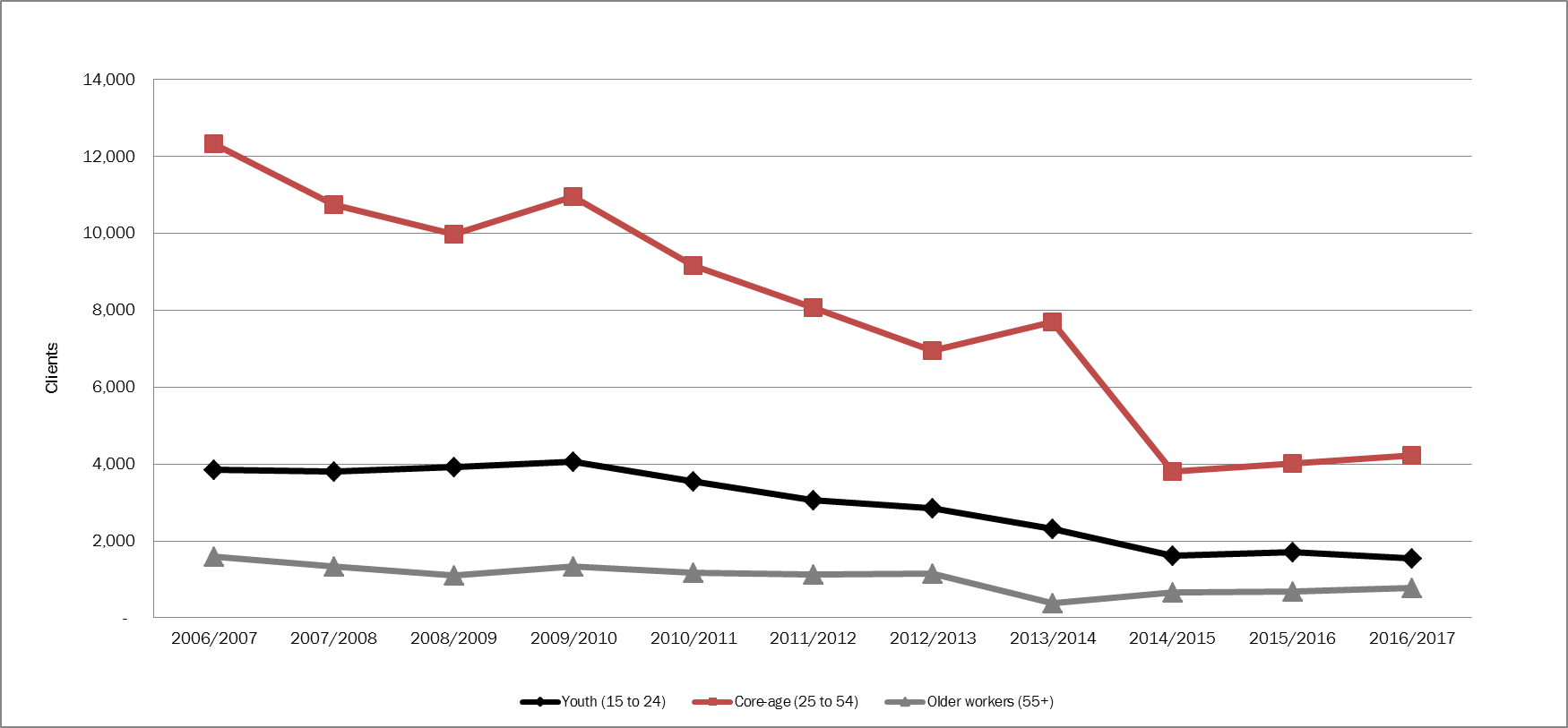

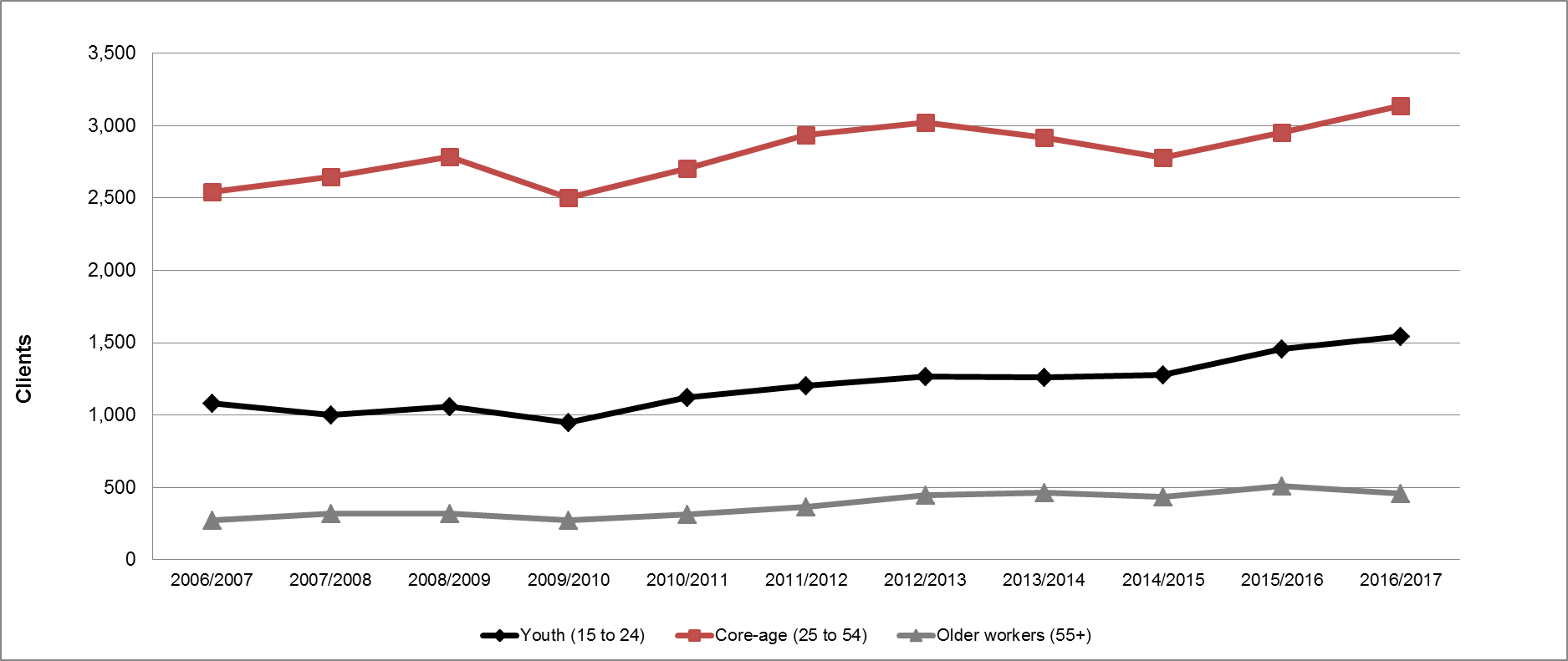

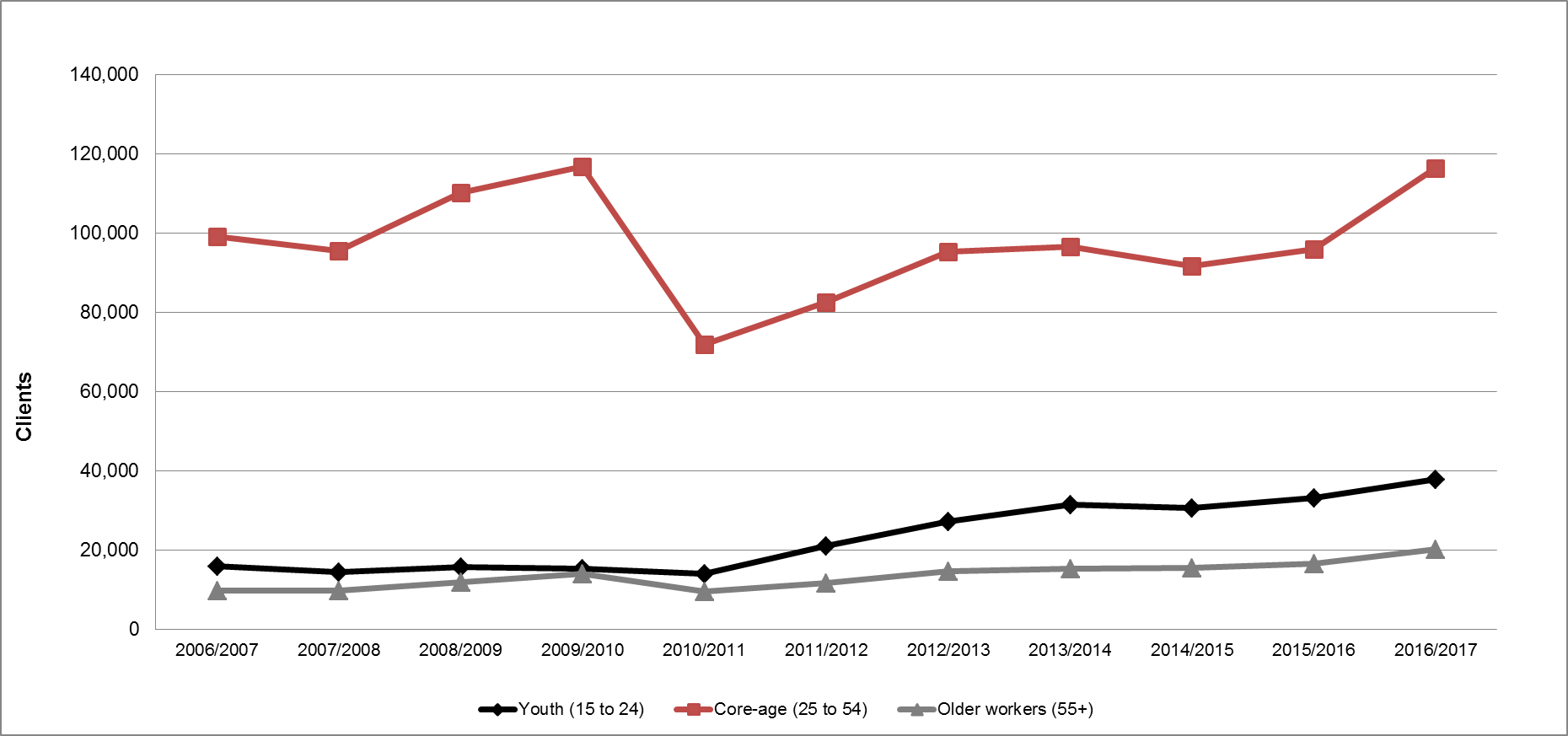

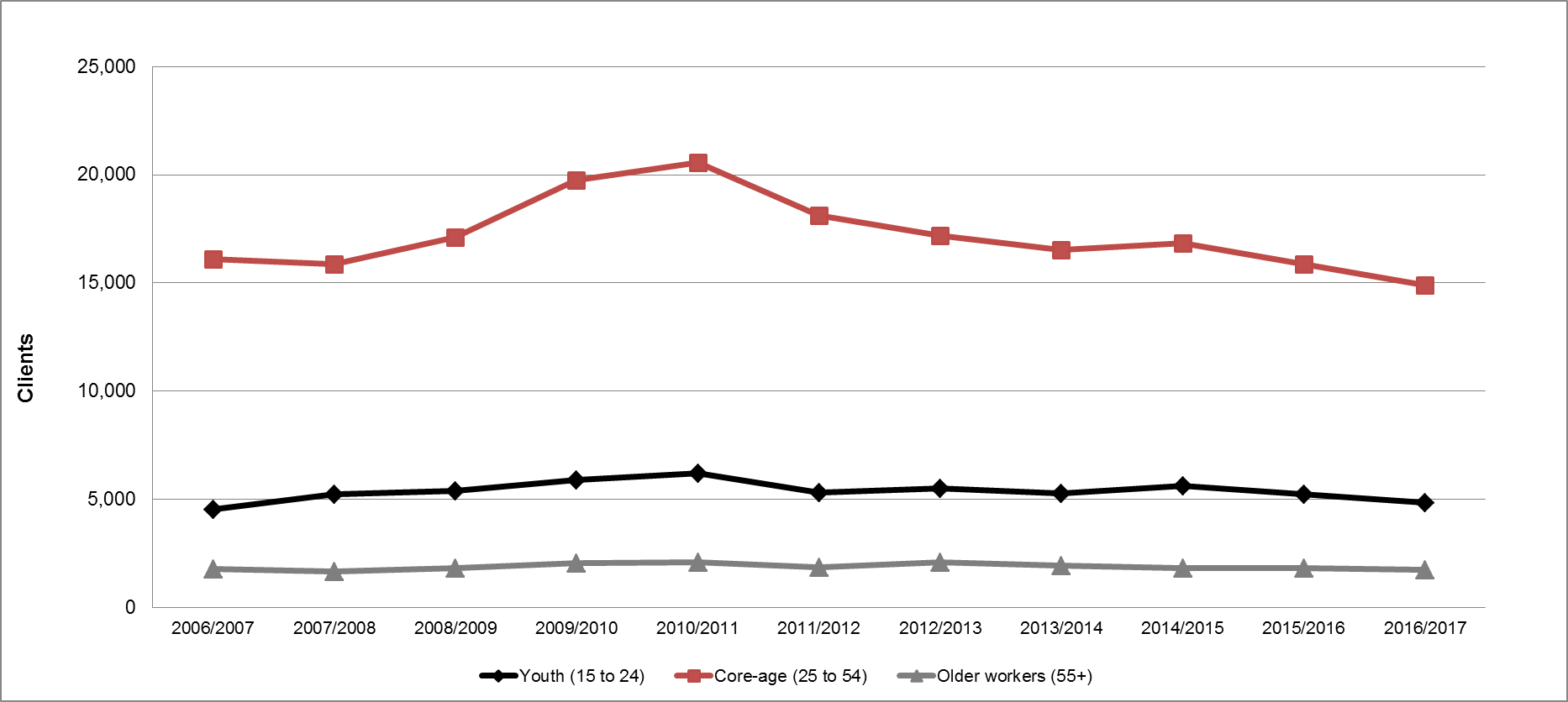

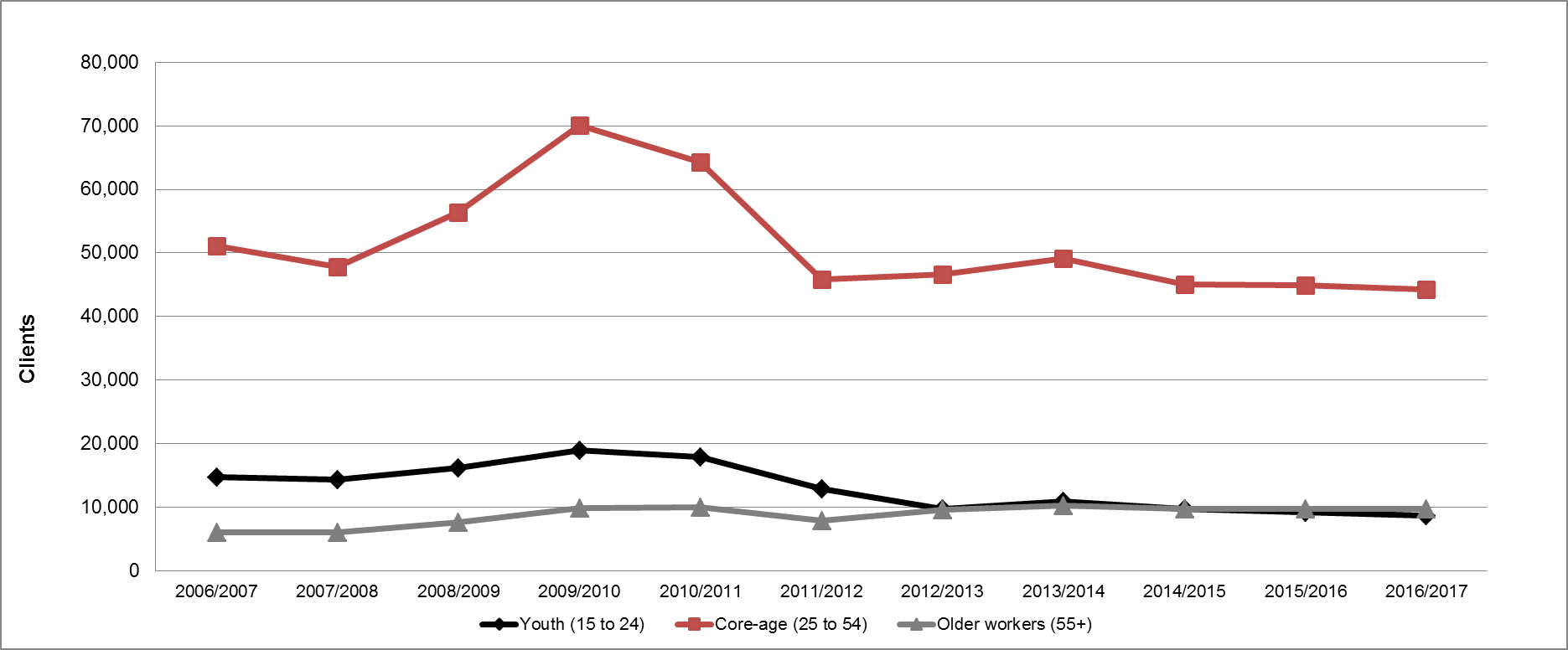

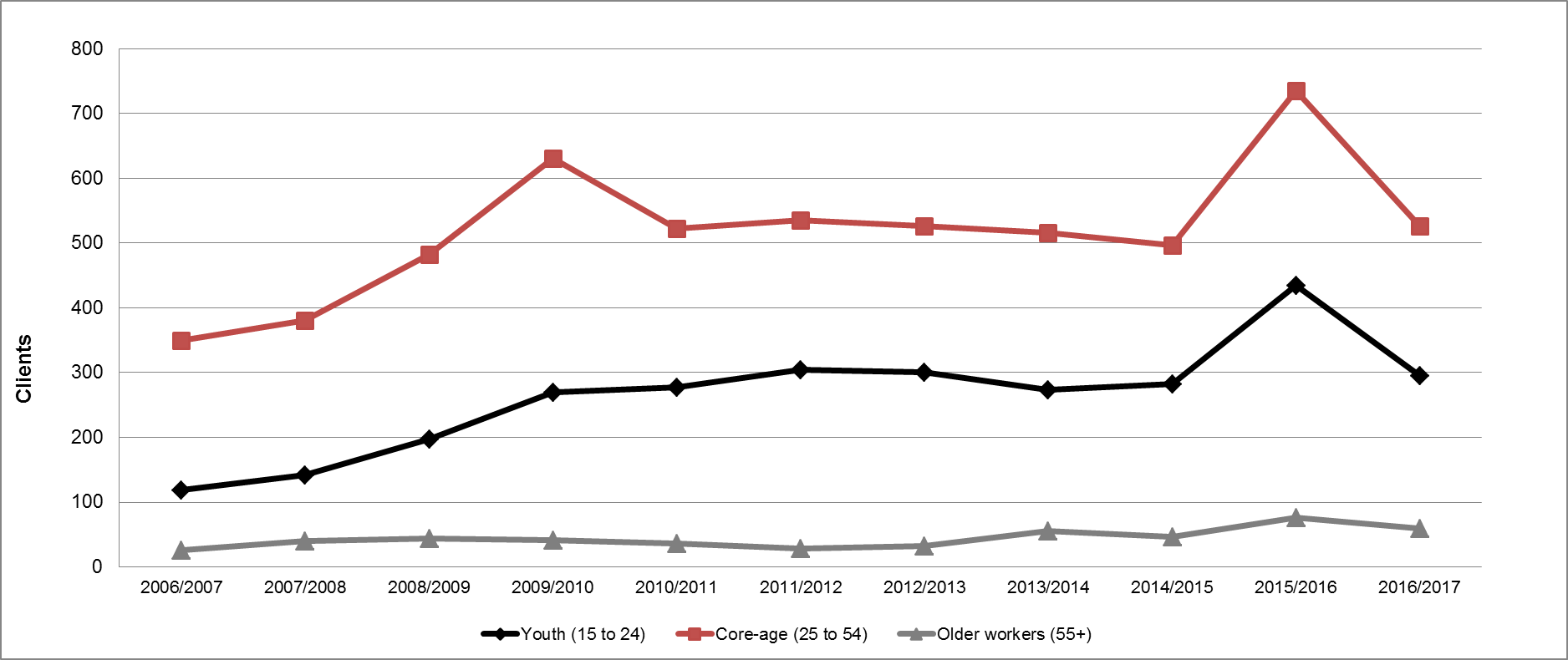

The majority (66.7%) of EBSM clients in FY1617 were core age workers (aged 25 to 54 years old) for a total of 440,176 individuals in this age group. The share of core age workers among all age groups dropped slightly, despite the number of core age workers increasing by 17,127 clients (+4.0%), from FY1516 results. Over ten years, the proportion of core age workers fell by 6.3 percentage points, as their growth has slowed down, especially after FY1213.

About one in five (20.4%) of EBSM clients in FY1617 were youth (aged 15 to 24), or a total of 134,465, increasing by 3.0% compared to FY1516. Their use of EBSM programming grew by 42.4% over the last ten years. Historically, youth have higher unemployment rates than core age workers and older workers. Youth were more impacted by the 2008 to 2009 recession and experienced slower recovery afterwards. This increase in EBSM usage could be attributed to provinces and territories increasingly focussing on labour market programming for youth.

In FY1617, the number of EBSM clients over the age of 55 increased by 8.1%, to a total of 85,056, compared to the previous year. This group represented 12.9% of all EBSM participants. Similar to young Canadians, more older workers have been participating in active labour market programs and services in the last ten years, spiking by 124.8%. This corresponds with the growing number of older workers in the labour force, which increased by 60.6% since FY0607. In turn, this growth fuelled the demand for labour market services for this age group.

Show Data Table

| Youth (15-24 years old) | Core-age (25-54 years old) | Workers aged 55+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 18.3% | 73.0% | 7.3% |

| 2007-2008 | 18.3% | 72.4% | 7.8% |

| 2008-2009 | 17.8% | 71.5% | 8.3% |

| 2009-2010 | 17.9% | 71.8% | 8.8% |

| 2010-2011 | 19.3% | 69.9% | 9.5% |

| 2011-2012 | 19.3% | 69.9% | 9.5% |

| 2012-2013 | 19.4% | 69.5% | 11.0% |

| 2013-2014 | 19.4% | 69.0% | 11.6% |

| 2014/2015 | 19.4% | 68.1% | 12.5% |

| 2015-2016 | 20.6% | 66.9% | 12.4% |

| 2016-2017 | 20.4% | 66.7% | 12.9% |

- Note: 'Unknown' age group is not displayed.

Designated groupsFootnote 10

ESDC collects information on the EBSM participation of women, Indigenous peoples, members of visible minorities and persons with disabilities, in support of employment equity principles. ParticipantsFootnote 11 voluntarily self-identify, as such, fluctuations from year to year may be due to changes in self-identification.

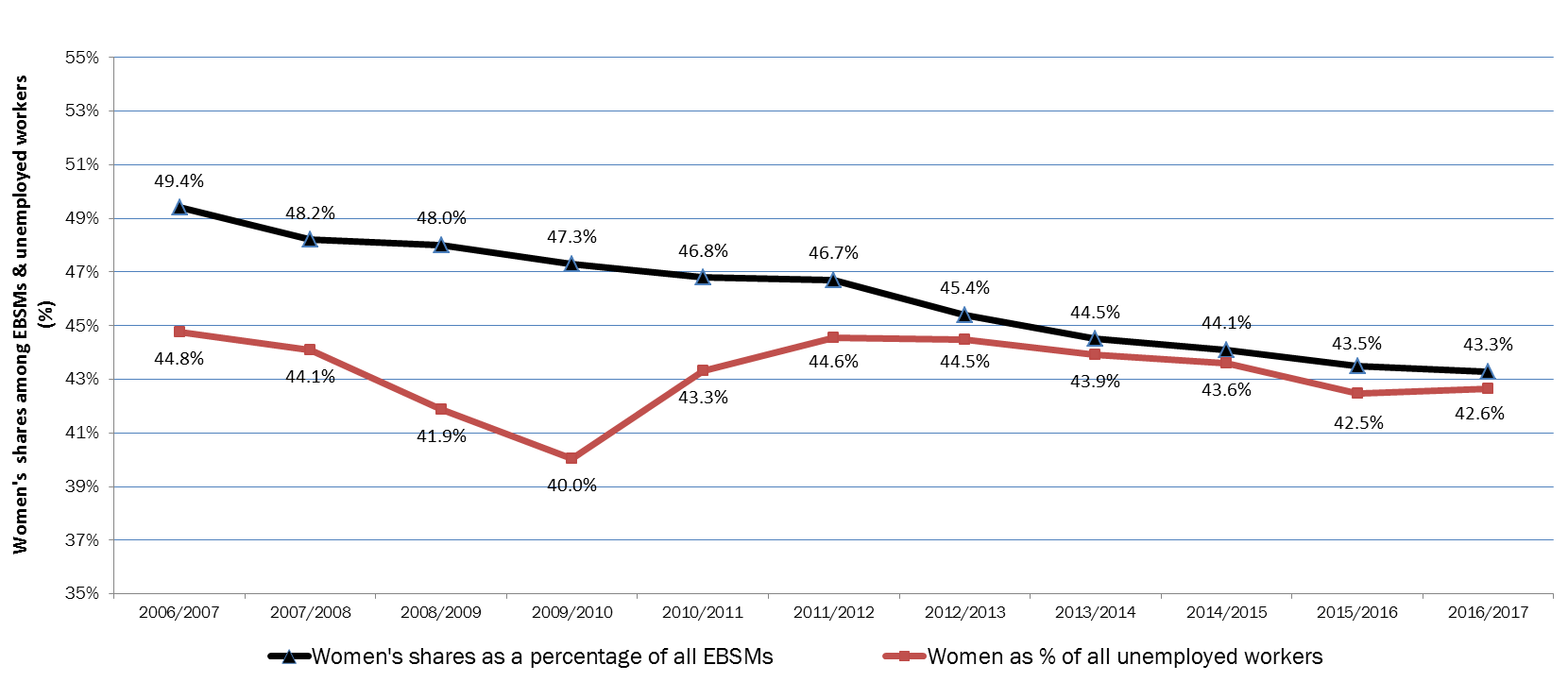

- Women participated in a total of 494,054 EBSM interventions in FY1617, a 1.3% increase year over year (43.3% of all interventions delivered to Canadians). By way of context, women represented 42.6% of the unemployed workers in FY1617. Women accessed EAS interventions (92.1%) at a higher rate than men (82.7%). Overall, 50.5% of women clients were non-insured, compared to 38.8% for men. (See box for details on women's EBSM participation).

- A total of 138,969 participants self-identified as persons with a disability in FY1617, an increase of 9.4% year-over-year. Over ten years, the proportion of participants with a disability has increased by 191.5%. Among several factors, this can be attributed to workers ageing into disabilityFootnote 12. Persons with disabilities participated in 12.2% of all interventions delivered in FY1617. The vast majority (94.2%) participated in an EAS-only intervention, compared to 5.8% who participated in Employment Benefits. The majority were non-insured (55.6%), a slight drop of 0.1 percentage points, compared to FY1516.

- Indigenous peoples participated in 86,726 interventions in FY1617, a slight decrease of 2.1% year over year. Indigenous people participated in 7.6% of all EBSM interventions, including programming delivered through ASETS. Employment Benefits delivered to Indigenous peoples, decreased from 4.1% to 3.9% year-over-year, while EAS-only represented the remaining 96.1% of interventions. In the last ten years, EAS use among Indigenous peoples has increased by 30.9%, whereas Employment Benefit use has dropped by 42.9%.

- Members of visible minority groups participated in 70,649 interventions in FY1617, an increase of 35.4% from last year. As a result, visible minorities' share of total interventions increased from 4.6% to 6.2% compared to FY1516 results. The majority of interventions (95.3%) were EAS-only, compared to 4.7% for Employment Benefits. In the last ten years, the number of interventions delivered to members of visible minority groups have declined by 0.8%.

Women's participation in EBSMs

The number of EBSM interventions delivered to women increased from 446,824 in FY0607 to 494,054 in FY1617, an increase of 10.6%. Over this ten year period, women's share among all interventions decreased from 49.4% to 43.3%.

In the last ten years, women have fared relatively better than men on several labour market indicators. For example, employment growth among women has been higher (+11.4%) than that of men (+8.9%). In addition, women's share of unemployed Canadians has steadily declined, from 44.8% in FY0607, to 42.6% in FY1617. In particular, the 2008 to 2009 recession and the subsequent recovery period, was less severe for women than for men, as the industries that were the hardest hit by employment losses at that time were male-dominated. Women, however, are more likely to work in service industries such as health care, education and social assistance, where employment has continued to rise. As a result, the demand for active labour market programming among women in recent years has been less pronounced than for men.

Show Data Table

| Women's shares as a percentage of all EBSMs | Women as % of all unemployed workers | |

|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 49.4% | 44.8% |

| 2007-2008 | 48.2% | 44.1% |

| 2008-2009 | 48.0% | 41.9% |

| 2009-2010 | 47.3% | 40.0% |

| 2010-2011 | 46.8% | 43.3% |

| 2011-2012 | 46.7% | 44.6% |

| 2012-2013 | 45.4% | 44.5% |

| 2013-2014 | 44.5% | 43.9% |

| 2014/2015 | 44.1% | 43.6% |

| 2015-2016 | 43.5% | 42.5% |

| 2016-2017 | 43.3% | 42.6% |

Official languages

ESDC furthers the commitment of the Government of Canada to foster the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society, by ensuring that labour market programs and services are delivered in both official languages. In this context, all LMDAs contain commitments by provinces and territories to have programs and services delivered in both official languages where there is sufficient demand.

1.4 Interventions: Employment Benefits

Historically, Employment Benefits have consisted of longer-term interventions focused on providing skills or work experience required to regain employment. Under LMDAs, provinces and territories provide employment benefits similar to the following six benefits types: Skills Development-Regular (SD-R); Skills Development-Apprentices (SD-A); Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS); Self-Employment (SE); Job Creation Partnerships (JCPs); and Targeted Earnings Supplements (TES)Footnote 13.

Decline in Employment Benefits interventions and expenditures in FY1617

In FY1617, Employment Benefits interventions totalled 147,054 and remained relatively stable (+0.4%) year-over-year. The stability of Employment Benefits in FY1617 can be largely attributed to the decreasing number of active claimants, usually the main beneficiaries of these types of interventions. The average of length of an Employment Benefit intervention increased from 111 days in FY1516, to 117 days in the current year, suggesting provinces and territories provided longer and more intensive supports, facilitated through the additional funding under Budget 2016 (see section 1.6 for expenditure details). In the context of tightening labour market and fewer individuals relying on provincial and territorial supports and services, investments focussed on retraining and upskilling existing clients for improved employment outcomes. In FY1617, this was evident through increased returns to work among Employment Benefits, which increased from 72,788 to 76,593 (+5.3%) year over year. However, total spending shrank by almost $56 million year-over-year (-4.9%), to a total $1.07 billion.

| Employment Benefits | Interventions | Share of Employment Benefits | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($000s) |

Estimated cost per intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Development-Regular | 52,627 |

35.8% |

+1.0% |

855,300 |

$7,053 |

|

| Skills Development-Apprentice | 68,633 |

46.7% |

-3.1% |

|||

| Targeted Wage Subsidies | 16,404 |

11.2% |

+11.6% |

120,768 |

$7,281 |

|

| Self-Employment | 6,137 |

4.2% |

-2.2% |

59,752 |

$9,736 |

|

| Job Creation Partnerships | 3,253 |

2.2% |

+26.2% |

34,827 |

$10,706 |

|

| Canada | 147,054 |

100% |

+0.4% |

1,070,647 |

$7,281 |

|

SD-R interventions edged up (+1.0%) to a total of 52,627, while SD-A interventions dropped by 3.1%, to a total of 68,633 in FY1617. Combined, Skills Development interventions made up 82.5% of all Employment Benefits. Expenditures on Skills Development programming totalled $855.3 million, lower than the $887.8 million spent in FY1516. This is mainly attributable to the decline in apprentice training in FY1617, despite the addition of $125 million in LMDA funding for FY1617.

In FY1617, TWS interventions increased by 11.6% year-over-year, to 16,404. This type of intervention represented 11.6% of all Employment Benefit interventions. Expenditures on TWS programming totalled $120.8 million, an increase of $9 million in spending compared to the previous fiscal year. Atlantic Provinces and Quebec are the main jurisdictions delivering TWS programming accounting for almost 90% of total spending in Canada.

The number of SE interventions delivered decreased by 2.2%, to 6,137, with their shares among all Employment Benefits reaching 4.2%. Coinciding with this drop in interventions, SE expenditures contracted significantly in FY1617; going from $99 million in FY1516, to $59.8 million in the current reporting year. This sharp drop is mainly attributable to Ontario winding down its SE benefit in FY1516, resulting in an overall decline at the national level.

Among Employment Benefits, delivery of JCP interventions surged to a total of 3,253 interventions across Canada, increasing by 26.2%, compared to FY1516 results. In turn, JCPs' share among Employment Benefits edged up, from 1.8% to 2.2%, year-over-year. Reflecting this increase, JCP expenditures jumped to $34.8 million, compared to $28 million in the previous year. The increase was mainly driven by British Columbia, where JCP programming expanded significantly (+63% in the number of interventions), while spending increased by $4.6 million year-over-year.

Overall, Employment Benefits interventions have declined in the last decade, while apprentice training has grown

Since FY0607, total Employment Benefits delivered by provinces and territories has dropped by over 21%. However, SD-A programming is the only Employment Benefit that grew; increasing by 25.8% over this period. In many provinces and territories, apprentice training is used to address skills shortages and provides training for in-demand occupations. Over the last decade, provinces and territories delivered more than 700,000 apprentice training interventions to Canadians, while all other intervention types have dropped: SD-R (-40.1%); TWS (-13.6%), SE (-45.9%), and JCP (-50.2%). This contributes to an overall decline in the number of Employment Benefits interventions delivered throughout Canada.

1.5 Interventions: Support Measures

Part II of the Employment Insurance Act authorizes three support measures: Employment Assistance Services (EAS), Labour Market Partnerships (LMPs), and Research and Innovation (R&I). Through LMDAs, provinces and territories deliver these measures at regional and local levels, while ESDC retains responsibility for pan-Canadian delivery of LMPs and R&I (see section 4: Pan-Canadian Activities and the National Employment Services). Support Measures are available to all unemployed individuals in Canada, including non-insured clients. However, LMPs and R&I are generally not associated with direct client services and, therefore, counts on participants or interventions are not available. Delivered by the provinces and territories, the EAS component of the Support Measures provides a full range of self-help and assisted services, such as support in determining career objectives through employment counselling; improving job search techniques; completing a return-to-work action plan; and accessing labour market information in support of career choices.

Employment Assistance Services

Employment Assistance Services interventions declined in FY1617

Provinces and territories design and deliver interventions similar to Employment Assistance Services (EAS), which are available to all unemployed people in Canada. In addition to helping EI-insured clients, EAS interventions provide crucial support to those who have been absent from the labour market for an extensive period or who have low job attachment. They may also support new immigrants or young people who are entering the Canadian labour market for the first time. These interventions are reported in one of the three following categories: Employment Services, Group Services, and Individual Counselling. In FY1617, a total of 999,884 EAS interventions were delivered, increasing by 1.0% year-over-year. The rise in EAS usage coincided with the increase of non-insured clients. With additional LMDA funding, the average cost of an EAS intervention increased from $590 in FY1516 to $715 in the current reporting period.

Interventions similar to Employment Services continued to be the most common EAS intervention type, accounting for 60.1% of all EAS interventions in FY1617. A total of 601,159 Employment Services interventions were provided to unemployed individuals in Canada, a decrease of 3.6% year-over-year. Since FY0607, these interventions increased by 42.6%, attributable to a greater focus on delivering short-term interventions for quicker returns to work among unemployed Canadians.

Group Services dropped by 29.9%, for a total of 25,279 interventions delivered in FY1617. In turn, the share of Group Services among all EAS-type interventions dropped to 2.5%, compared to 3.6% in the previous year.

| Employment Assistance Services* | Interventions | Share of Support Measures | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($000s) |

Estimated cost per intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Services | 601,159 |

60.1% |

-3.6% |

|

|

|

| Group Services | 25,279 |

2.5% |

-29.9% |

|

|

|

| Individual Counselling | 373,406 |

37.3% |

+12.9% |

|

|

|

| Total Employment Assistance Services | 999,884 |

100% |

-1.0% |

$714,544 |

$715 |

|

| Other Support Measures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Labour Market Partnerships | - |

- |

- |

165,886 |

- |

|

| Research & Innovation | - |

- |

- |

116,533 |

- |

|

| Canada | 999,884 |

100% |

+1.0% |

$996,963 |

$715 |

|

In addition to being the initial intervention for establishing action plans and potential access to Employment Benefits, Individual Counselling is particularly important when supporting clients who face multiple barriers to employment. A total of 373,406 interventions were delivered in FY1617 (an increase of 12.9% year-over-year). This accounted for 37.3% of all EAS interventions.

Other Support Measures

The Labour Market Partnership (LMP) initiative facilitates collaboration between employers, employees and employer associations, community groups and communities to develop solutions to labour force imbalances, such as persistent high unemployment or skill shortages. In FY1617, LMP expenditures totalled $165.9 million, an increase of 8.3% year-over-year.

Research and Innovation in British Columbia

Since launching its R&I in 2014, British Columbia (BC) recently reshaped and enhanced delivery of its funding stream with greater focus on client opportunities to gain experience and attach to in-demand jobs. BC also introduced the Social Innovation stream under its R&I program to expand the scope of Community and Employer Partnerships program, and support innovative projects that address social challenges beyond employment.

With R&I funding, BC also invested in The Centre for Employment Excellence (CfEE). The CfEE acts as a coordination point for research, communication, training and employment in British Columbia; the first of its kind for employment services in Canada. The Centre's online resources, along with its popular webinar series are loaded with information and ideas for practitioners, employers and policy-makers to draw upon to improve employment outcomes for job seekers in the province.

For more information, visit the Centre for Employment Excellence Web site

Research and Innovation (R&I) initiatives identify better ways of helping people prepare for, return to or maintain employment and participate productively in the labour force. In FY1617, R&I expenditures increased to $116.5 million, which is 48.5% higher than in the previous year.

1.6 Expenditures

Increased spending on Employment Assistance Services, Labour Market Partnerships, and Research & Innovation

Show Data Table

| 2016/17 spending chart | Value |

|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 1,070,647 |

| Employment Assistance Services | 714,544 |

| LMP & R&I | 282,419 |

| Pan-Canadian | 114,063 |

- Note: As per budget 2016, an additional $125 million in LMDA funding pushed overall spending to $2.07 billion.

Total expenditures under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act were $2.18 billion in FY1617, which included EBSM programming, LMPs and R&I, as well as the pan-Canadian activities. As per Budget 2016, an additional $125 million in LMDA funding pushed overall spending by provinces and territories upwards by 6.2% (see box for examples of investments under the new funding).

Under the LMDAs, Employment Benefits remained the largest investment, at $1.071 billion, representing about half total expenditures by provinces and territories. Compared to FY1516, spending on Employment Benefits declined by nearly $56 million (-4.9%). This is attributable to decreasing interventions due to an improving economy, and fewer active claimants being served by provinces and territories. Employment Assistance Services expenditures jumped by 22.3% year-over-year, as spending increased from $584.3 million in FY1516 to $714.5 million in FY1617. EAS spending accounted for 35% of all expenditures under the LMDAs. Expenditures towards LMPs and R&I measures jumped as well, going from $231.7 million in FY1516, to $282.4 million in FY1617 (+21.9%). Ontario's $44 million in new R&I spending was largely responsible for the increase. In Alberta, as well as in Newfoundland and Labrador, LMPs and R&I expenditures jumped by almost 300%, and 154%, respectively, which also contributed to significant rise in Canada's overall LMP and R&I investments.

Pan-Canadian expenditures edged up by 1.4%, increasing from $112.5 million in FY1516 to $114.1 million to FY1617. See Section 4 of this chapter for details on Pan-Canadian activities.

Additional LMDA funding for FY1617 from Budget 2016

Under Budget 2016, an additional $125 million went towards the LMDAs for FY1617, giving provinces and territories additional flexibility to support Canadians access training and employment services. For example:

- Alberta increased its capacity to deliver Career and Employment Information Services to individuals negatively impacted by the economic downturn. This included events to connect Albertans with prospective employers, and regular information sessions for job seekers related to job search strategies, career planning, and networking. To enable greater success for individuals re-entering the labour market, the delivery of Job Placement services was expanded to rural Albertans, with a focus on one-to-one support. The province also increased investment in 25 communities across the Province in its Self-Employment and Workplace Training (TWS) programs. New Integrated Training (JCP) programs were also introduced to address local labour market demand for skills training, including agriculture, trades, truck driving, and child care development, among others.

- New Brunswick invested in its Training and Skills Development Program and the Experiential Learning Employment (ELE) Continuum initiative. This helps social assistance clients acquire classroom and on-the-job training through employment placement.

- British Columbia focused on supporting new clients as a result of changes to the EI program (elimination of new entrant and re-entering provisions and expanded ‘reachback' eligibility for former claimants). The province also directed funding in support of Skills Development participants with associated training costs. Community and Employer Partnership projects were also expanded to focus on priority clients, like persons with disabilities, Indigenous, youth and immigrants.

- Prince Edward Island expanded its eligibility criteria for its employer sponsored training programming, like EmployPEI and the Graduate Mentorship Program, to include non-profit organization, municipalities and educational institutions. The province assisted more unemployed Islanders find jobs, and provided employers with workers with the right set of skills.

- Manitoba made policy changes to its Skills Development Program to increase financial supports for Manitobans living in rural and remote regions. In addition, Labour Market Partnerships were used to facilitate labour adjustments following business closures.

- Newfoundland and Labrador utilized the additional funding to meet the increased demand for Skills Development programming. This supported more individuals under the province's Self-Employment Assistance benefit. The province implemented a Research & Innovation support measure to test new ways of helping people find jobs.

- Saskatchewan supported increased demand for services offered through Rapid Response Teams, providing services to businesses and individuals impacted by layoffs and/or slowdowns.

- The Northwest Territories focused on developing tools to identify EI clients earlier in their claim to offer them relevant programming. The NWT government worked with regional partners to identify ways of improving employment opportunities for EI eligible clients.

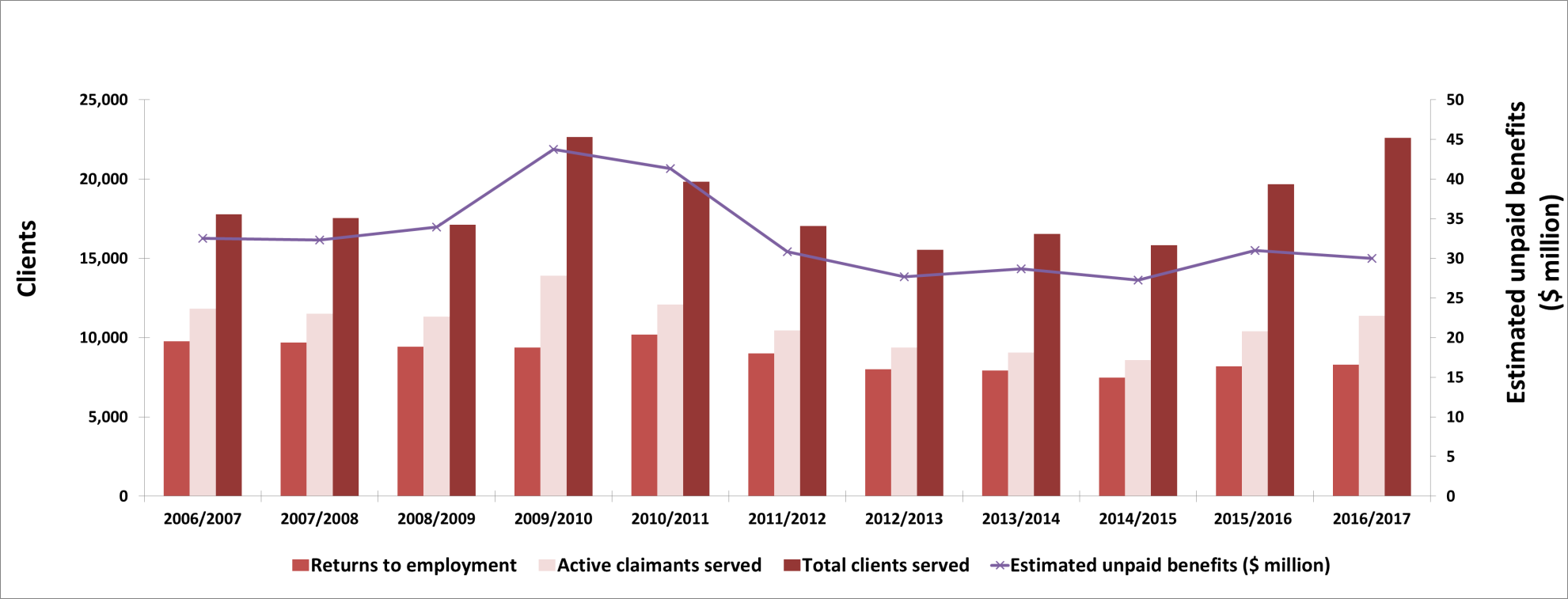

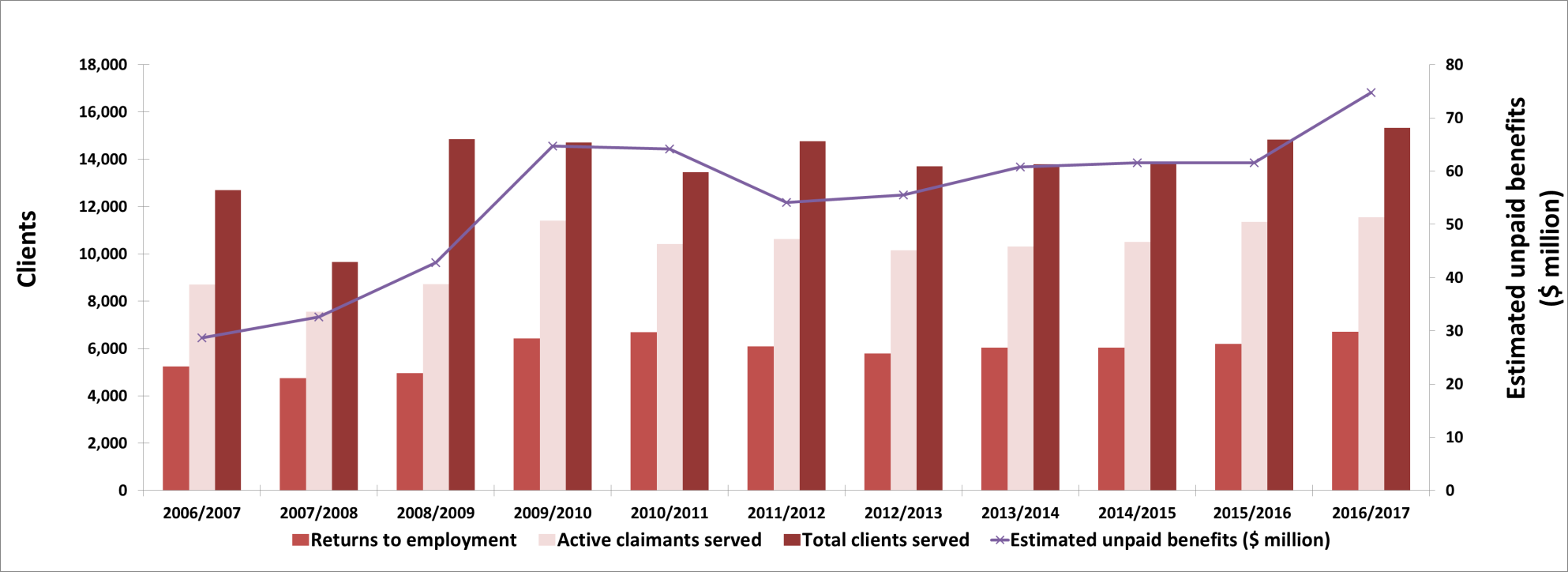

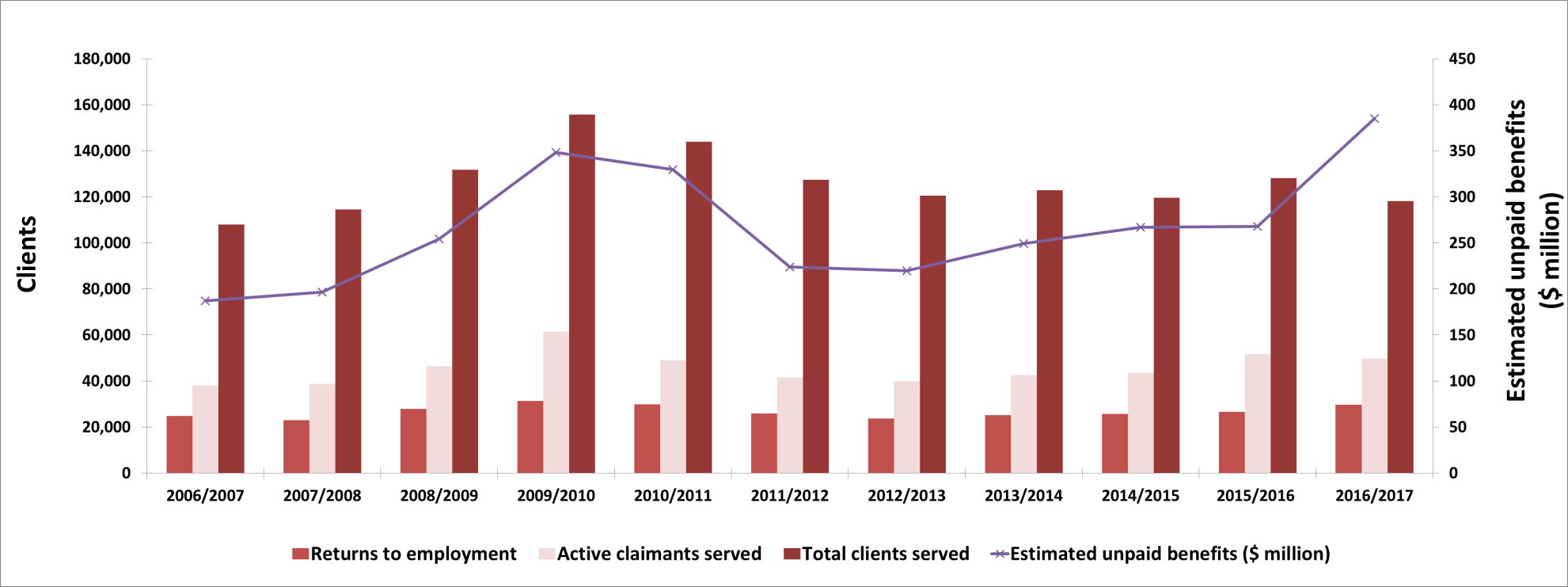

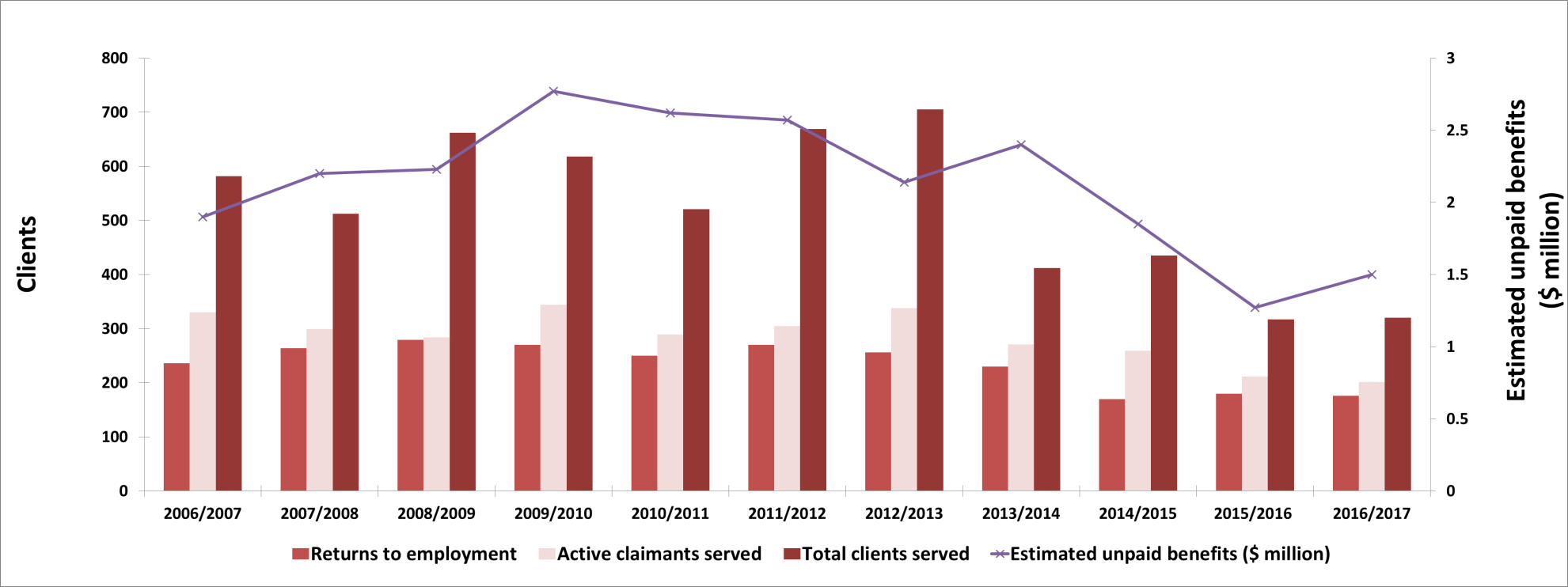

1.7 Key performance indicatorsFootnote 14

ESDC monitors the results of EBSM-similar programming delivered by provinces and territories through three key performance indicators:

- the number of active EI claimants served;Footnote 15

- the number of EI clients who return to employment following an intervention;Footnote 16 and

- the amount of unpaid EI Part I benefits resulting from the returns to employment.

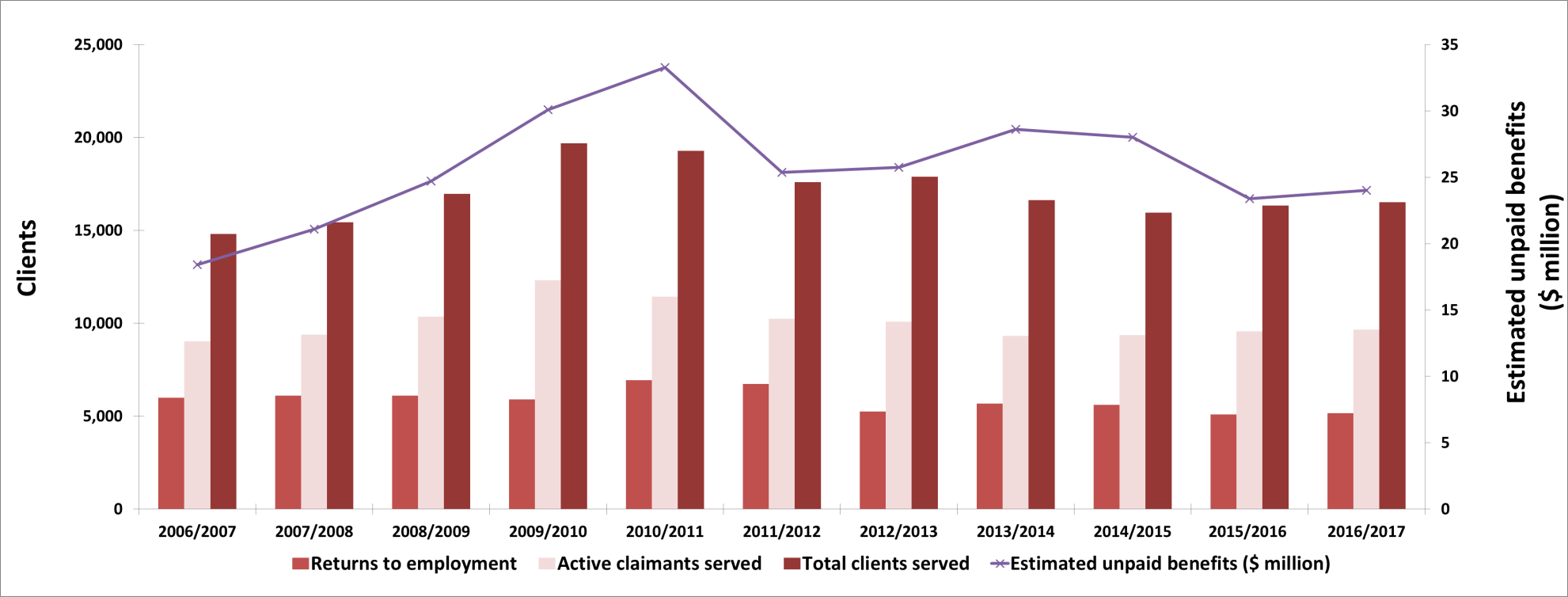

Show Data Table

| Returns to employment | Active claimants served | Total clients served | Estimated unpaid benefits ($ Million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 203,692 | 342,145 | 602,157 | $856.30 |

| 2007-2008 | 196,498 | 329,127 | 595,910 | $866.90 |

| 2008-2009 | 207,927 | 380,181 | 676,842 | $1,056.74 |

| 2009-2010 | 222,524 | 453,781 | 758,761 | $1,540.25 |

| 2010-2011 | 243,452 | 365,978 | 742,907 | $1,430.35 |

| 2011-2012 | 185,029 | 320,006 | 631,522 | $1,002.86 |

| 2012-2013 | 161,992 | 312,553 | 647,127 | $985.44 |

| 2013-2014 | 171,956 | 341,358 | 695,745 | $1,061.50 |

| 2014/2015 | 173,593 | 332,099 | 674,081 | $1,121.98 |

| 2015-2016 | 178,556 | 348,392 | 717,896 | $1,153.37 |

| 2016-2017 | 187,172 | 341,262 | 734,309 | $1,344.97 |

- Important: in response to the 2008-2009 recession, the Government of Canada invested a total of $1.0 billion over two years—2009/10 and 2010/11—in the delivery of EI Part II programming through Canada's EAP.

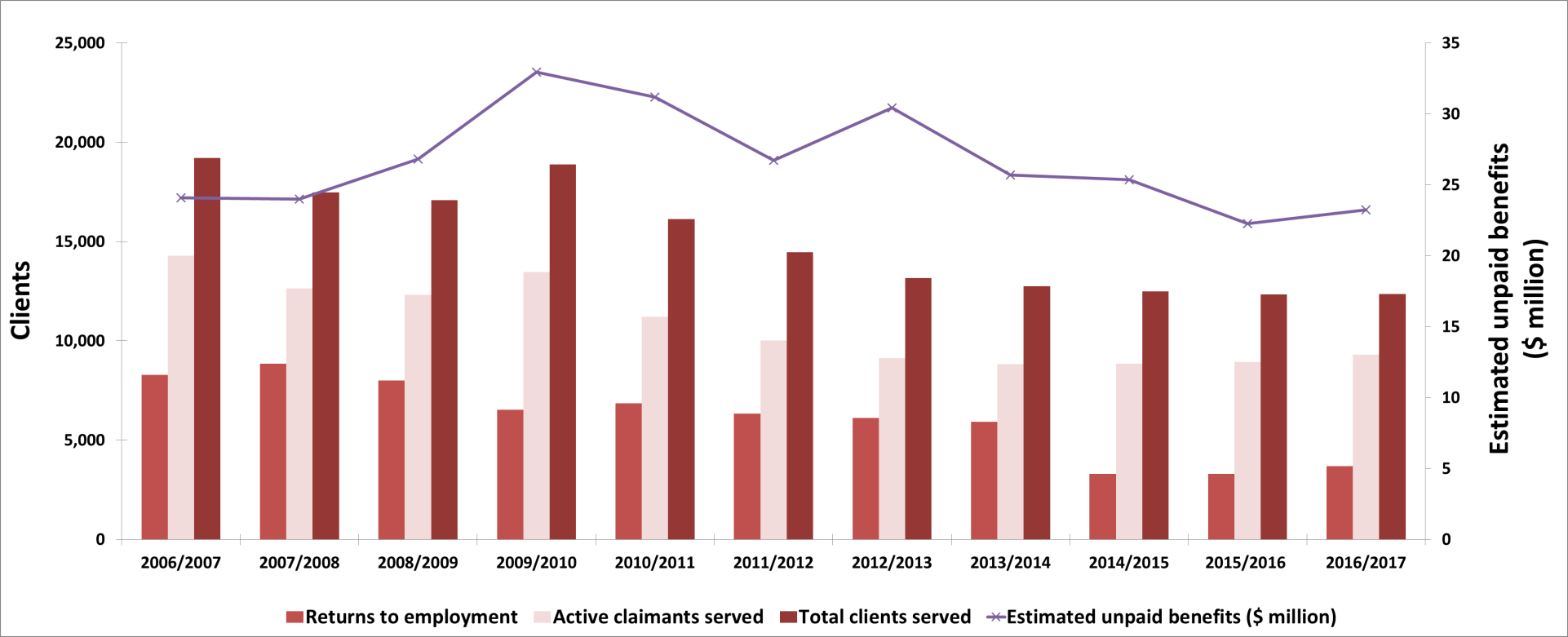

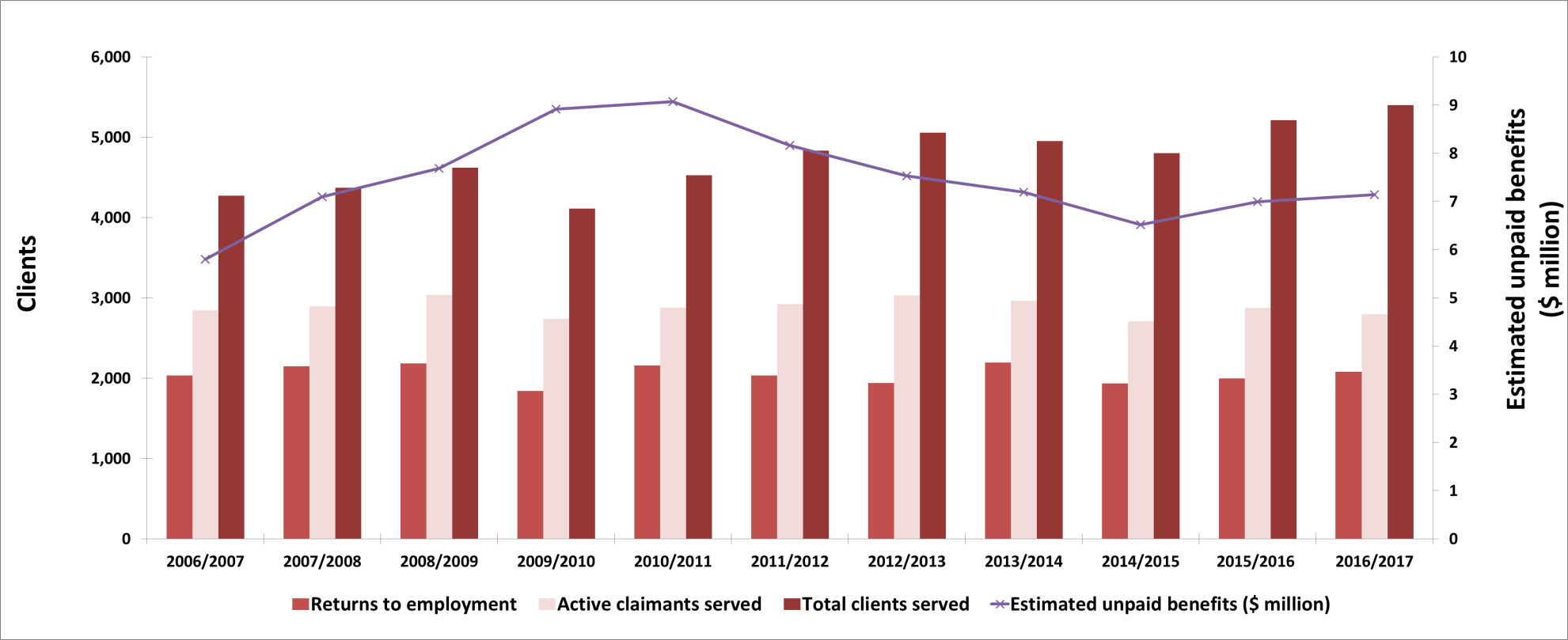

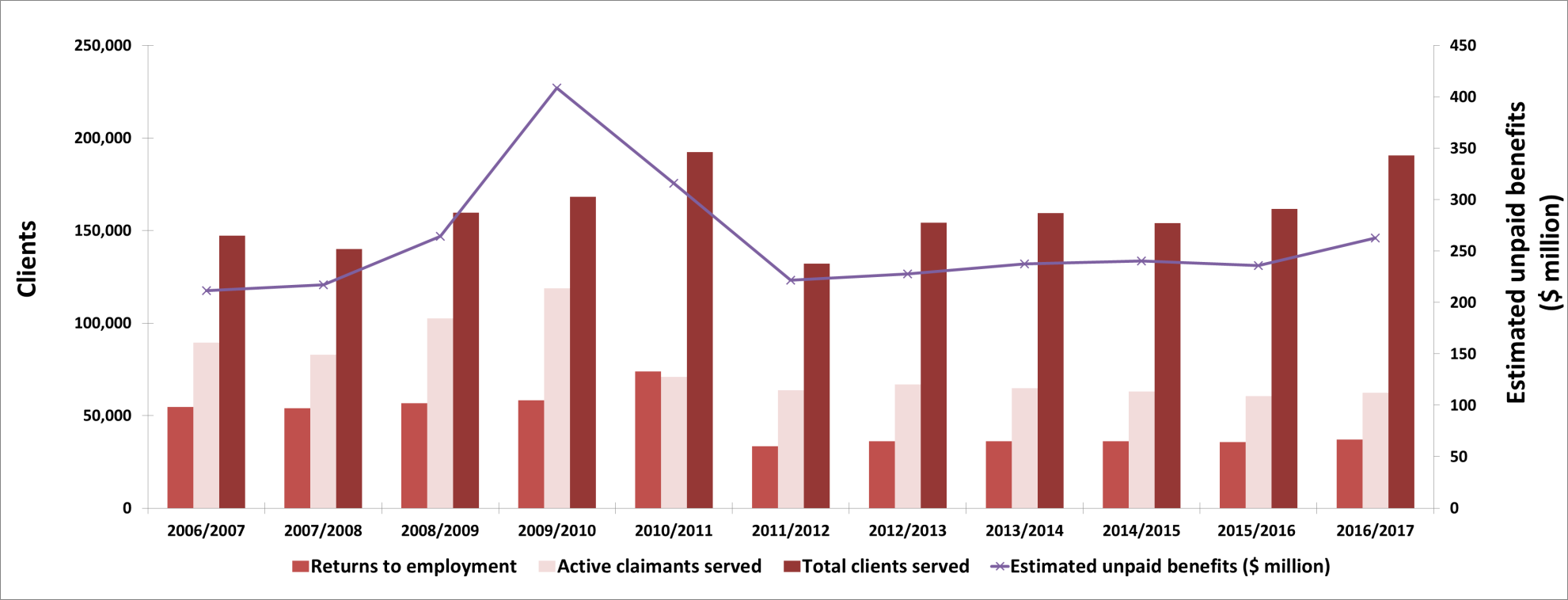

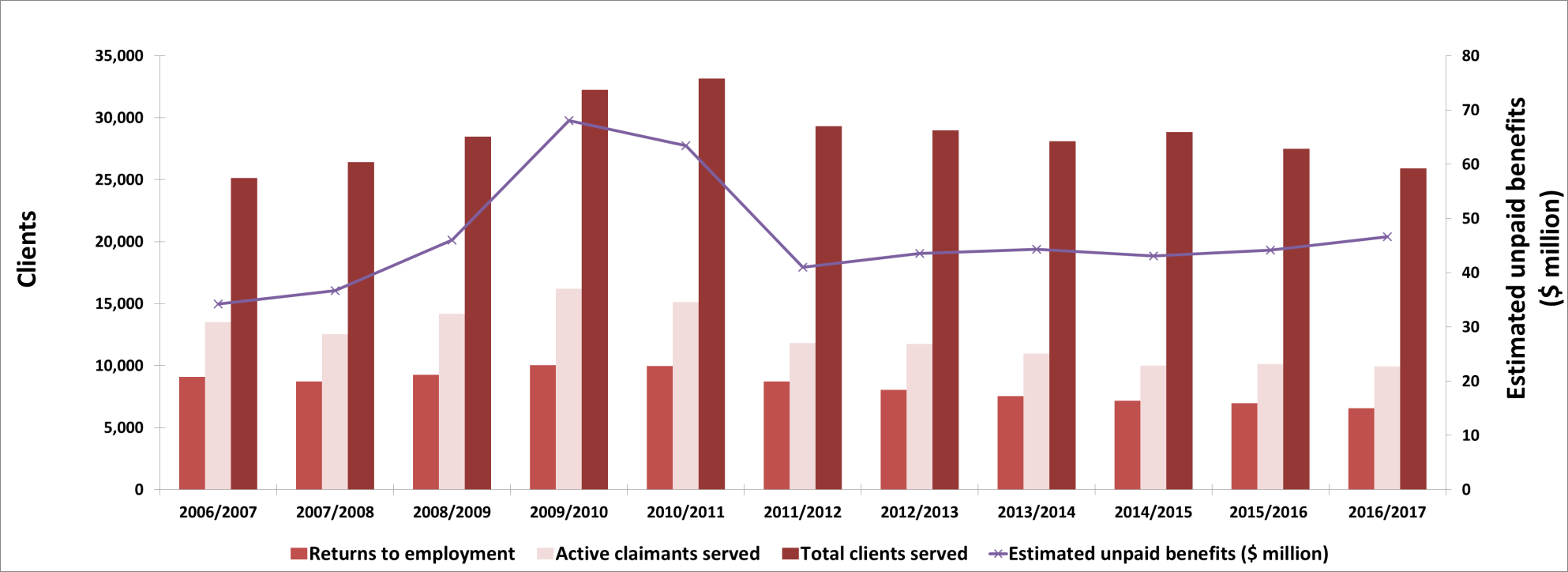

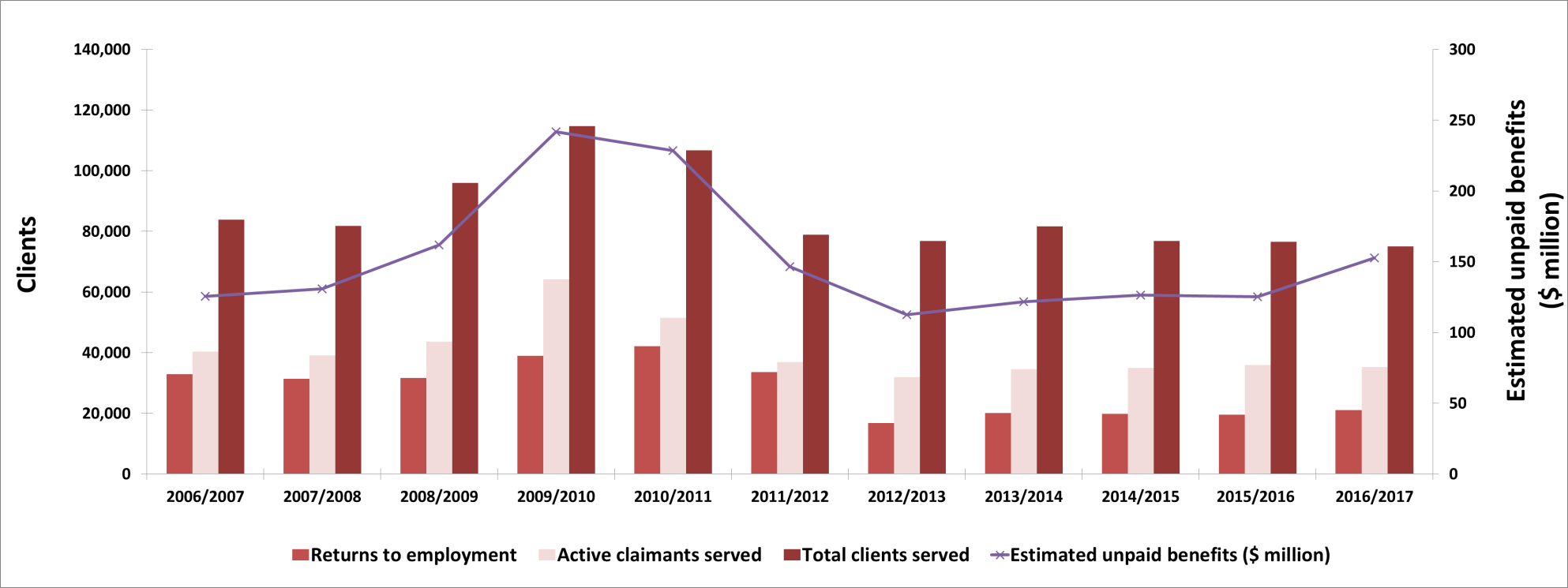

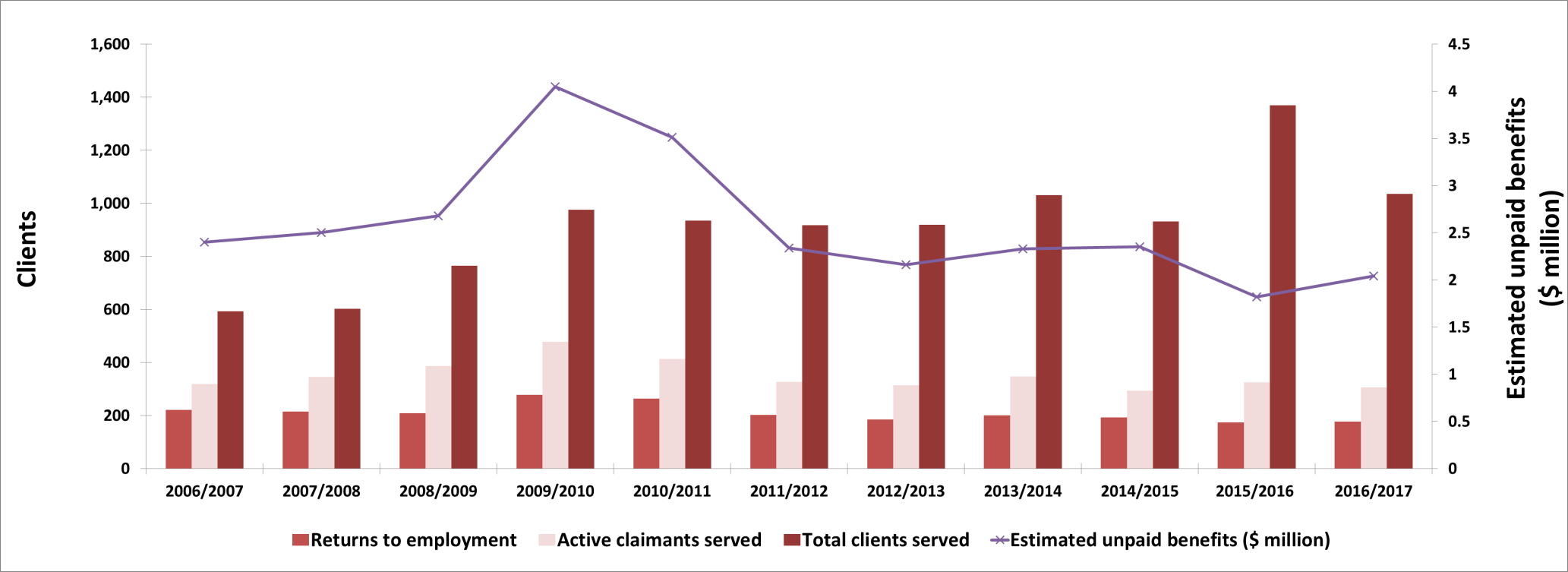

Lower number of active EI claimants with returns to work and unpaid EI benefits increasing

In the context of improving labour market and economic conditions in FY1617 throughout most parts of Canada, the number of active EI claimants served (351,362) dropped by 1.5% year-over-year. Improving labour market and economic conditions pushed up the returns to employment by 4.8% year-over-year, with a total of 187,172 clients finding work after their interventions. In turn, unpaid EI Part I benefits ($1.34 billion) jumped by 16.6%.

Compared to FY0607, unpaid EI Part I benefits increased by nearly $500 million (+57.1%). While several factors can influence the EI Part I benefits unpaid amount, a number of provinces and territories are reaching out to EI claimants earlier in their benefit period, to increase awareness of how LMDA programs and services can support their training and job search needs. By targeting clients earlier, which in turn contribute to speedier returns to work, LMDA participants are exiting the EI program sooner than they otherwise would have.

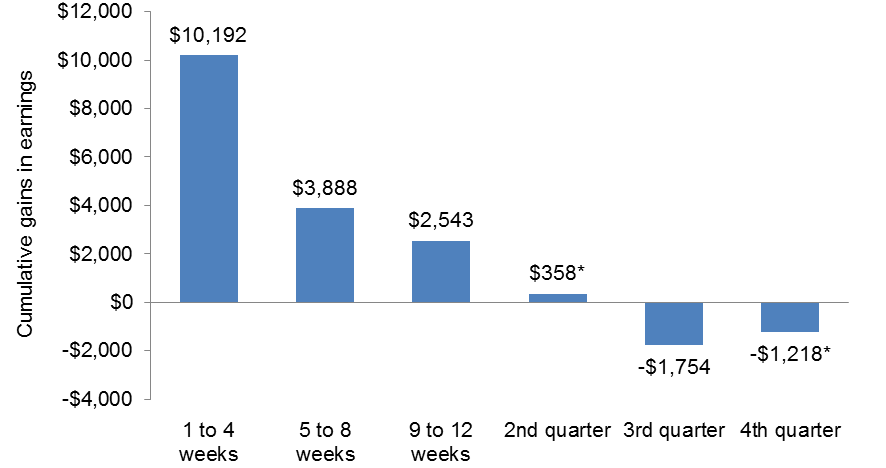

Recent LMDA evaluations demonstrate that providing EAS within the first four weeks of an EI claim facilitates faster returns to employment, and leads to increases in earnings after participation.Footnote 17 This evidence is encouraging a number of jurisdictions to target EI claimants with LMDA programs earlier. For example, a number of jurisdictions are already using the Targeting, Referral and Feedback (TRF) system to target EI applicants in order to direct them to relevant job opportunities or programs and services. Under the amended LMDA, the federal government will work with provinces and territories to implement a TRF system by March 2020 in all jurisdictions that do not already have a system in place.

Table 3 (see next page) presents supplementary performance indicators at the national and provincial/territorial level, contextualized with labour market indicators. Since multiple factors can influence results at the individual, jurisdictional, and national level, these indicators cannot be unequivocally attributed to LMDAs.

At the national level, close to 57% of active LMDA participants began their first LMDA-funded intervention within 12 weeks after their Benefit Commencement Period (BPC). Quebec exceeded the national average (72.6%), where the province's long-established TRF system helps Emploi-Québec to identify EI claimants at risk of prolonged unemployment for active employment supports. All other provinces and territories were below the national average, ranging from roughly 19% to 50% of active LMDA participants beginning EI Part II programming within 12 weeks of their BPC.

In terms of returns to work as a proportion of LMDA clients served, the national average was 25.5% in FY1617. Eight provinces and territories exceeded the national average, ranging from 26.6% in Quebec to 55% in Yukon. Whereas Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut were below the national average.

In FY1617, Canada's returns to work from ESBM interventions among active clients, expressed as a proportion of Canada's labour force was 1.0%, with 8 provinces and territories exceeding the national average. Secondly, unpaid EI regular benefits stemming from returns to work, expressed as proportion of total EI regular benefits paid, was 10.6%. Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia and Northwest Territories posted higher proportions than the national figure.

In addition, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta are above the national average for both ratios. This suggests an effective and efficient balance between returning clients to work as soon as possible, while ensuring they are provided with the necessary active employment services to succeed in the job market over a mid to long-term horizon.

| Employment change & unemployment rate (FY1617) |

Job vacancy rate (FY1617) | Percentage of EI active participants beginning EI Part II within 12 weeks following their Part I benefit period commencement * (2016-2017) |

Returns to work as a proportions of LMDA clients served (FY1617) |

Returns to work among active EI clients from EBSM interventions, as a proportion of the labour force (FY1617) |

Estimated unpaid EI regular benefits resulting EBSM interventions, as a proportion of Part I regular benefits paid (FY1617) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland & Labrador | -3,500 (-1.5%) 13.7% |

0.8 | 19.2% | 29.9% | 1.4% | 2.8% |

| Prince Edward Island |

-800 (-1.1%) 8.4% |

1.4 | 41.2% | 38.5% | 2.6% | 4.4% |

| Nova Scotia | -300 (-0.1%) 8.1% |

1.2 | 33.7% | 31.2% | 1.1% | 4.0% |

| New Brunswick | +2,600 (+0.7%) 9.2% |

1.3 | 49.4% | 36.7% | 2.1% | 4.2% |

| Quebec | +55,100 (+1.3%) 6.8% |

1.3 | 72.6% | 26.5% | 1.5% | 11.0% |

| Ontario | +79,200 (+1.1%) 6.4% |

1.4 | 42.5% | 19.4% | 0.5% | 8.6% |

| Manitoba | +400 (+0.1%) 6.1% |

1.4 | 47.4% | 25.3% | 1.0% | 13.7% |

| Saskatchewan | -4,400 (-0.8%) 6.4% |

1.4 | 35.9% | 43.8% | 1.1% | 17.0% |

| Alberta | -32,600 (-1.4%) 8.3% |

1.4 | 39.5% | 25.1% | 1.2% | 17.2% |

| British Columbia | +78,500 (+3.4%) 5.7% |

1.9 | 36.0% | 28.0% | 0.8% | 12.6% |

| Northwest Territories |

Unchanged 7.1% |

1.8 | 38.0% | 17.1% | 0.8% | 10.8% |

| Yukon | +1,000 (+5.5%) 5.4% |

1.6 | 31.1% | 55.0% | 0.6% | 7.9% |

| Nunavut | +1,000 (+6.6%) 14.5% |

1.3 | 28.9% | 8.9% | 0.5% | 10.1% |

| Canada | +174,300 (+1.0%) 6.9% |

1.4 | 56.7% | 25.5% | 1.0% | 10.6% |

- Source: Labour Force Survey, Business Payroll Survey, and EI Administrative Data.

- * This includes a small percentage of clients who began EI Part II programming up to 2 weeks prior to their Part I Benefit Period Commencement. SD-A participants and those who were non-insured participants were excluded, if they had taken EAS in the previous year.

1.8 Additional LMDA funding and expanded eligibility to programs and services

Budget 2017 invested an additional $1.8 billion to support programs funded through LMDAs, and amended the EI Act to broaden worker eligibility for programs and services under the LMDAs. This allows even more Canadians, including underrepresented groups, to access EI-funded skills training and employment supports, including:

- Broaden current eligibility to Employment Benefits for unemployed individuals who have made minimum EI premium contributions (that is, above the premium rebate threshold) in five of the previous ten years;

- Expand eligibility for Employment Assistance Services under Support Measures (e.g., employment counselling, job search assistance), currently available to unemployed Canadians, to also include employed Canadians; and

- Expand current eligibility for support measures, particularly to increase flexibility to support employer sponsored training under Labour Market Partnerships. This includes employers who need to upskill or retrain their employees to maintain their current employment (for example, to adjust to technological or structural changes in the economy).

These changes are effective as of April 1, 2018.

2. Provincial and territorial EBSM activities

This section analyzes the provincial and territorial economic environment and EBSM-similar activities in FY1617; linking trends in clients served, interventions, and expenditures to local labour market conditions, and employment programming priorities.

2.1 Context

Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories received funding to support the delivery of programs and services, similar to the EBSMs established under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act.Footnote 18 To address unique labour market challenges, provinces and territories delivered employment programming under LMDAs, which were individually negotiated with the Government of Canada. Provinces and territories designed and delivered all EI-funded active employment programming, except for pan-Canadian activities, discussed in Section 4 of this chapter.

Expenditures for EBSM-similar activities increased in all provinces and one territory between FY1516 and FY1617, supported by the additional $125 million investment announced in Budget 2016. This additional funding further supports unemployed Canadians to access employment benefits and services that develop skills and workplace experience. Compared to the previous year, most provinces and territories served more clients, and delivered more EBSM-Similar interventions, while the number of clients who returned to work increased in all but two jurisdictions.

Overall, Canada's economy and labour market strengthened in FY1617. On average, regions, such as central Canada, the Territories, and British Columbia enjoyed comparatively healthier economic and labour market conditions, than the Prairies and eastern Canada. Despite varying economic and labour market outcomes, all jurisdictions prioritized improving the labour market attachment of underrepresented groups, such as persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, recent immigrants, youth, and older workers; as well as ensuring that employers can readily access a skilled workforce. To meet these objectives, and to address the impacts of new technologies on job types and skills, provinces and territories engaged with numerous stakeholders, including employers, to ensure that training programs remained relevant in a context of an aging workforce and a shifting labour market landscape.

Successful outcomes from the provinces and territories are highlighted in the Managing for Results section. These approaches include:

- Employer engagement in program priorities and design;

- Strategies to deliver active employment supports earlier for EI claimants; and,

- Approaches in the use of the Research and Innovation support measure in some jurisdictions.

2.2 Newfoundland and LabradorFootnote 19

In 2016, Newfoundland and Labrador's real GDP growth expanded by 1.9%, after two years of decline due to weakened oil prices. The province benefitted from increased oil output and exports from 2015 to 2016. Real GDP growth is expected to contract again in 2017, as household spending eases due to weaker labour market conditions, and constrained government spending.

Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM key facts

| EI clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

11,120 |

1,232 |

| Interventions type | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 8,512 | 6.1% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 17,926 | 4.4% |

| Interventions type | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change ( pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 32.2% | 0.4 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 67.8% | 0.4 |

| Total expenditures | 2016-2017 ($ million) | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $117.0 | 3.4% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $6.3 | 18.8% |

| LMPs and R&I | $3.2 | 153.5% |

| Total expenditures1 | $126.4 | 5.6% |

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $22.25 | $23.23 | 4.4% |

- 1 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

In line with the weak economic environment the province has been facing over the past few years, labour market conditions continued to soften in Newfoundland and Labrador in FY1617. Total employment declined for a fourth consecutive year by 3,500 (-1.5%). This loss was entirely in full-time work. As a result, the unemployment rate increased to 13.7%, the second highest in the country after Nunavut (14.3%). There were employment losses in:

- Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas (-2,000; -12.8%);

- Manufacturing (-2,000; -17.4%); and

- Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (-1,100; -12.4%).

These losses were partially offset by gains in health care and social assistance (+1,600; +4.3%).

Newfoundland and Labrador's main labour market challenges are demographic; an aging population, declining working-age population, and youth out-migration. Consequently, the province set forth a number of labour market priorities for FY1617 to ensure a sufficient labour supply for employers, and to enhance their economic competitiveness. This included providing responsive, relevant, and flexible labour market programming by assisting individuals impacted by changes in the local labour market landscape; especially underrepresented groups, such as youth, persons with disabilities, as well as older workers. In addition, the province will develop an adaptive workforce by investing in employment and skills training. In partnership with employers and other stakeholders workforce needs will be identified by building an informed and productive focus on human resource needs.

Managing for results

In FY1617, the Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour organized seven Provincial Roundtables on Labour Market Transfer Agreements across the province, with over 130 participants. The provincial roundtables provided an opportunity for individual residents, employers, academics, researchers, labour groups, and non-profit, community organizations to share their input on the four labour market transfer agreements. In particular, the roundtables served as a channel for members of the public to provide ideas on how employment and skills training programs can be more relevant, flexible and responsive.

Some key themes arising from the roundtables included:

- Requirements for accurate and timely labour market information to assist governments in their short and long-term planning;

- Engagement with stakeholders to improve information-sharing;

- Greater program flexibility for both Employment Insurance (EI) and non-EI eligible individuals;

- Increased research funding focused on finding opportunities for work creation and researching promising practices to improve labour market outcomes; and

- Increased supports to individuals transitioning to employment, especially for those in under-represented groups.

Clients, interventions and expenditures

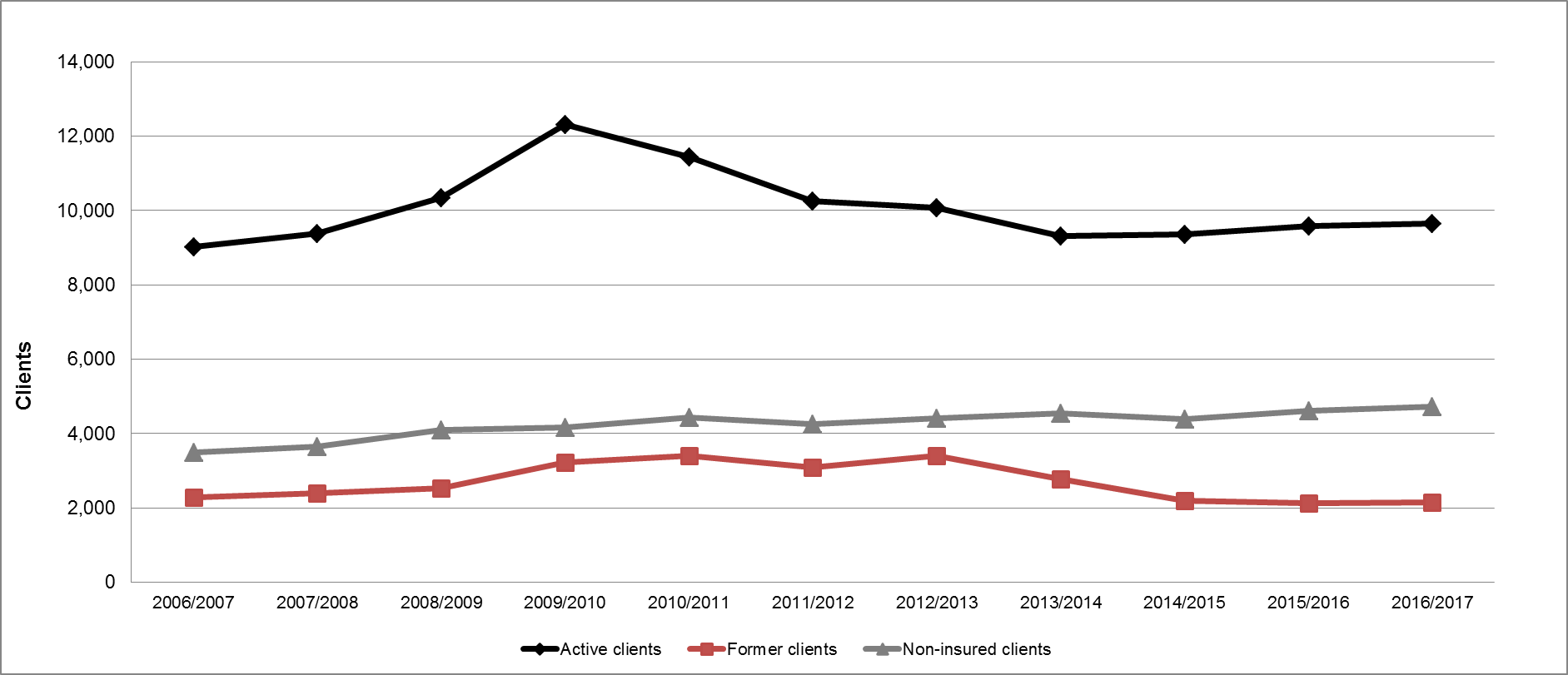

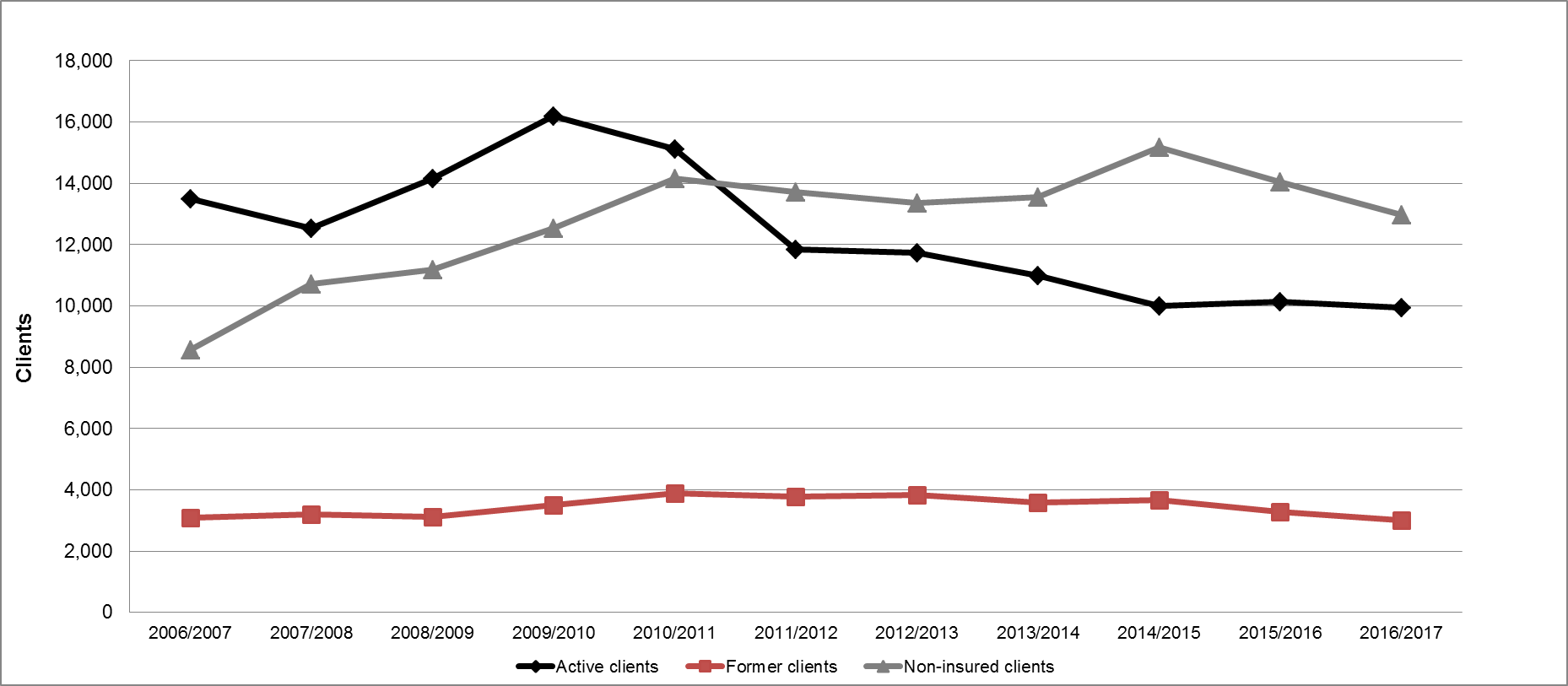

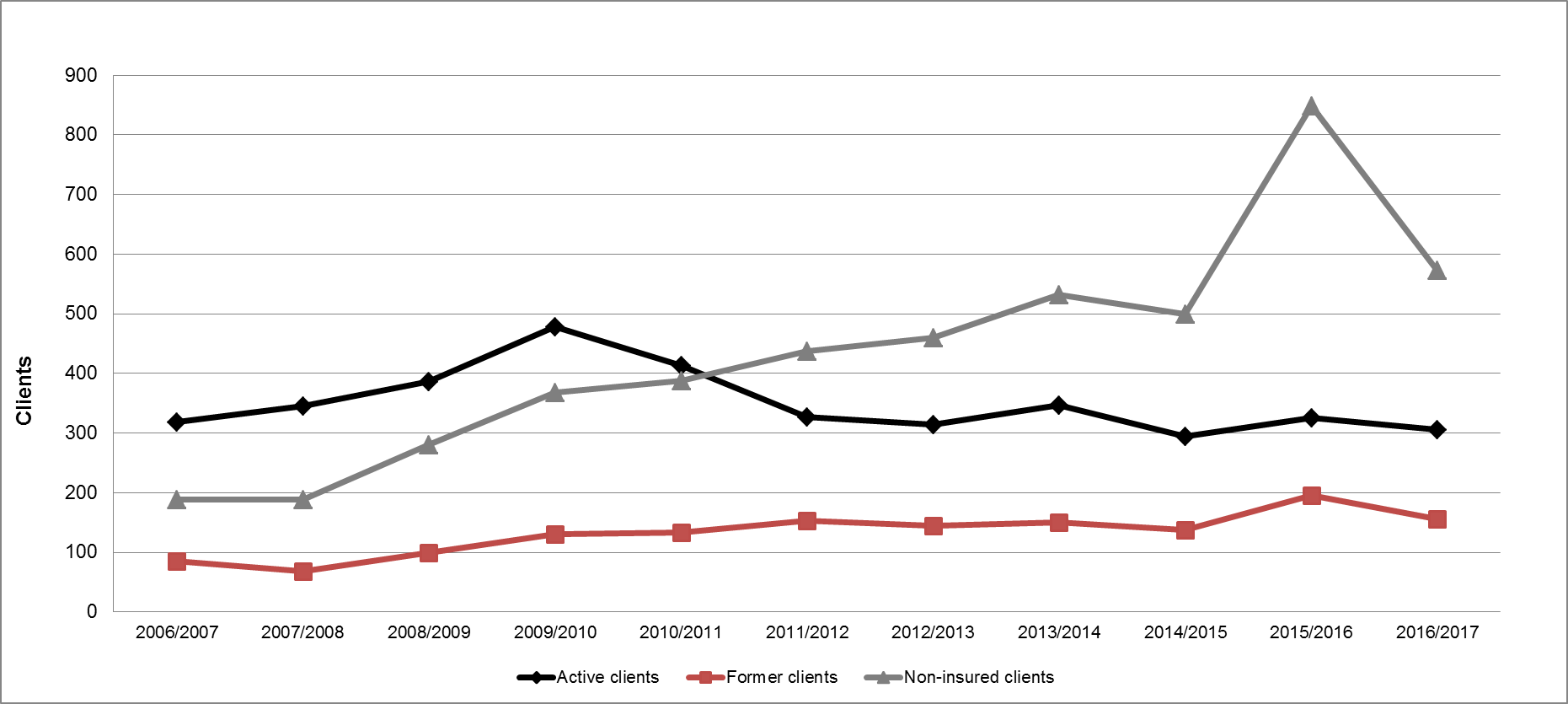

In FY1617, the total number of clients served by Newfoundland and Labrador remained stable at 12,352 (+0.2%). Client types grew in opposite directions this fiscal:

- Active claimants grew by 4.1% to 9,308;

- Former claimants shrank by 13.5% to 1,812; and

- Non-insured clients shrank by 5.0% to 1,232.

Reflecting this variance, client shares mirrored changes in client types:

- Active clients' share accounted for the highest proportion of total clients served at 75.4%. This represented a year-over-year increase of 2.9 percentage points;

- Former clients' share declined by 2.3 percentage points, from 17.0% to 14.7%; and

- Non-insured clients' share edged down by 0.5 percentage point, from 10.5% to 10.0%.

Newfoundland and Labrador delivered 26,438 interventions in FY1617, a 5.0% growth compared to the previous year. The total number of interventions delivered in the province remained relatively stable, with Employment Benefits taking 32.2% of shares, while shares of EAS continued at 67.8%. Unpaid Benefits grew by 4.4% to $23.23 million. Total expenditures for EBSM reached $126.4 million, a 5.6% increase year-over-year. Of the extra $6.8 million expended on EBSMs in FY1617, $4.5 million came from the province's share of the additional $125 million LMDA investment announced in Budget 2016.

Show Data Table

| Active claimants | Non-insured clients | Former claimants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 14,279 | 3,060 | 1,871 |

| 2007-2008 | 12,648 | 2,616 | 2,200 |

| 2008-2009 | 12,325 | 2,204 | 2,561 |

| 2009-2010 | 13,466 | 3,114 | 2,302 |

| 2010-2011 | 11,215 | 2,748 | 2,171 |

| 2011-2012 | 10,027 | 2,405 | 2,031 |

| 2012-2013 | 9,124 | 1,992 | 2,046 |

| 2013-2014 | 8,831 | 1,928 | 1,980 |

| 2014/2015 | 8,850 | 2,513 | 1,126 |

| 2015-2016 | 8,941 | 2,095 | 1,297 |

| 2016-2017 | 9,308 | 1,812 | 1,232 |

Show Data Table

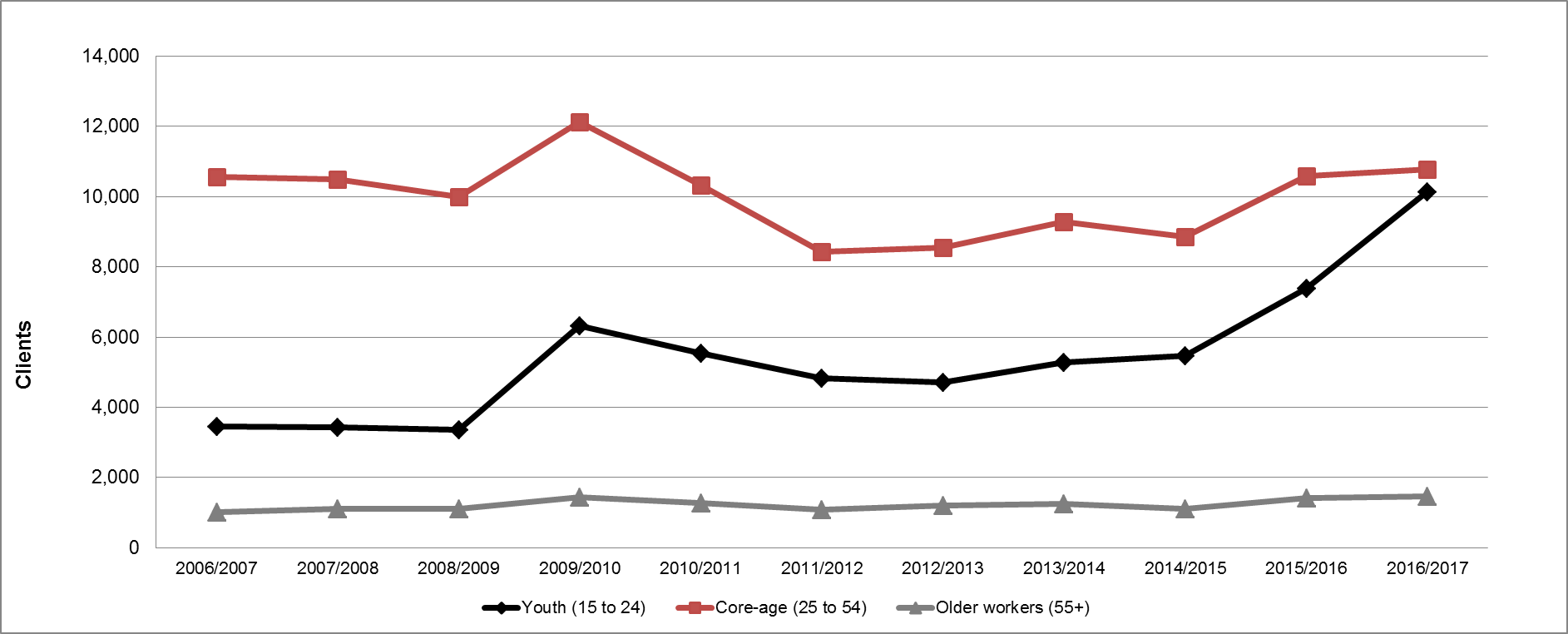

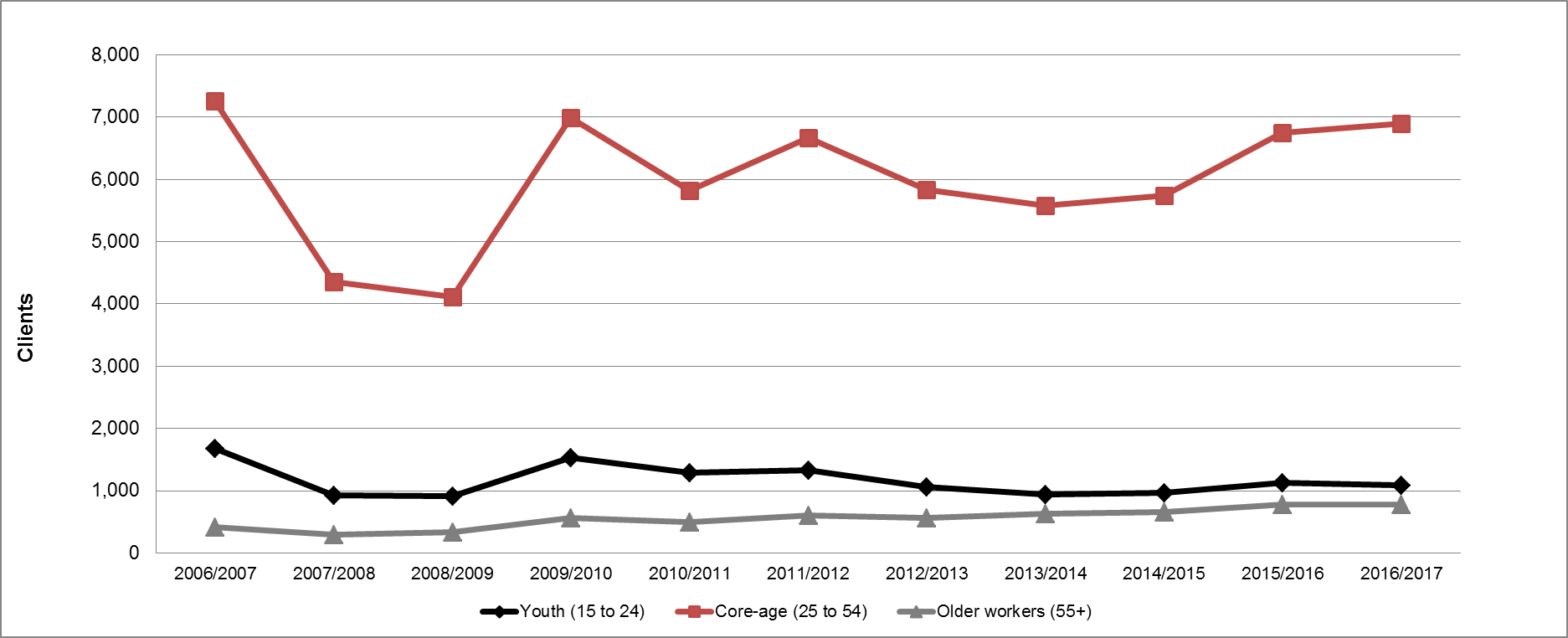

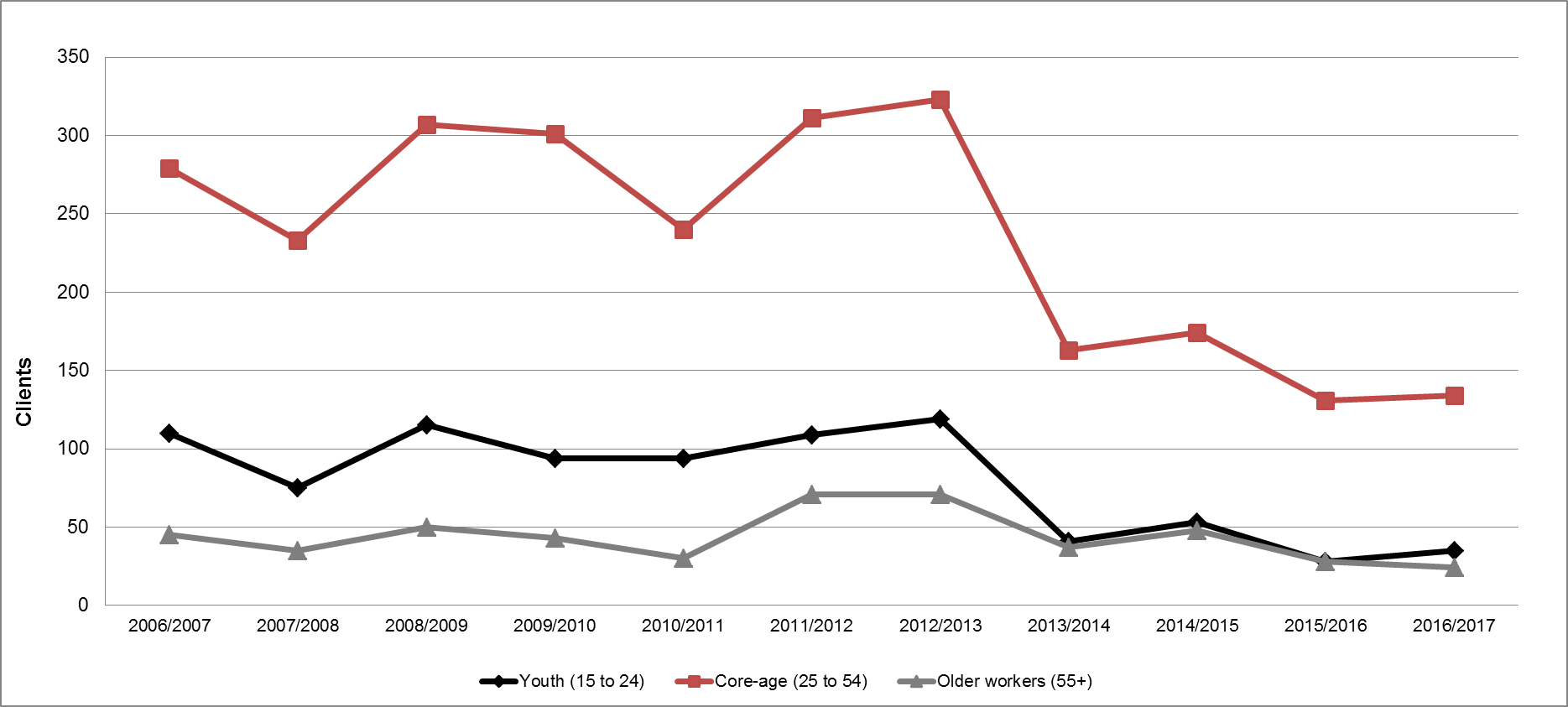

| Youth (15 to 24) | Core-age (25 to 54) | Older workers (55+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 3,853 | 12,320 | 1,602 |

| 2007-2008 | 3,796 | 10,751 | 1,348 |

| 2008-2009 | 3,927 | 9,970 | 1,116 |

| 2009-2010 | 4,061 | 10,957 | 1,341 |

| 2010-2011 | 3,541 | 9,154 | 1,178 |

| 2011-2012 | 3,055 | 8,066 | 1,124 |

| 2012-2013 | 2,846 | 6,942 | 1,145 |

| 2013-2014 | 2,325 | 7,699 | 376 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,627 | 3,814 | 665 |

| 2015-2016 | 1,700 | 4,021 | 676 |

| 2016-2017 | 1,545 | 4,217 | 769 |

Show Data Table

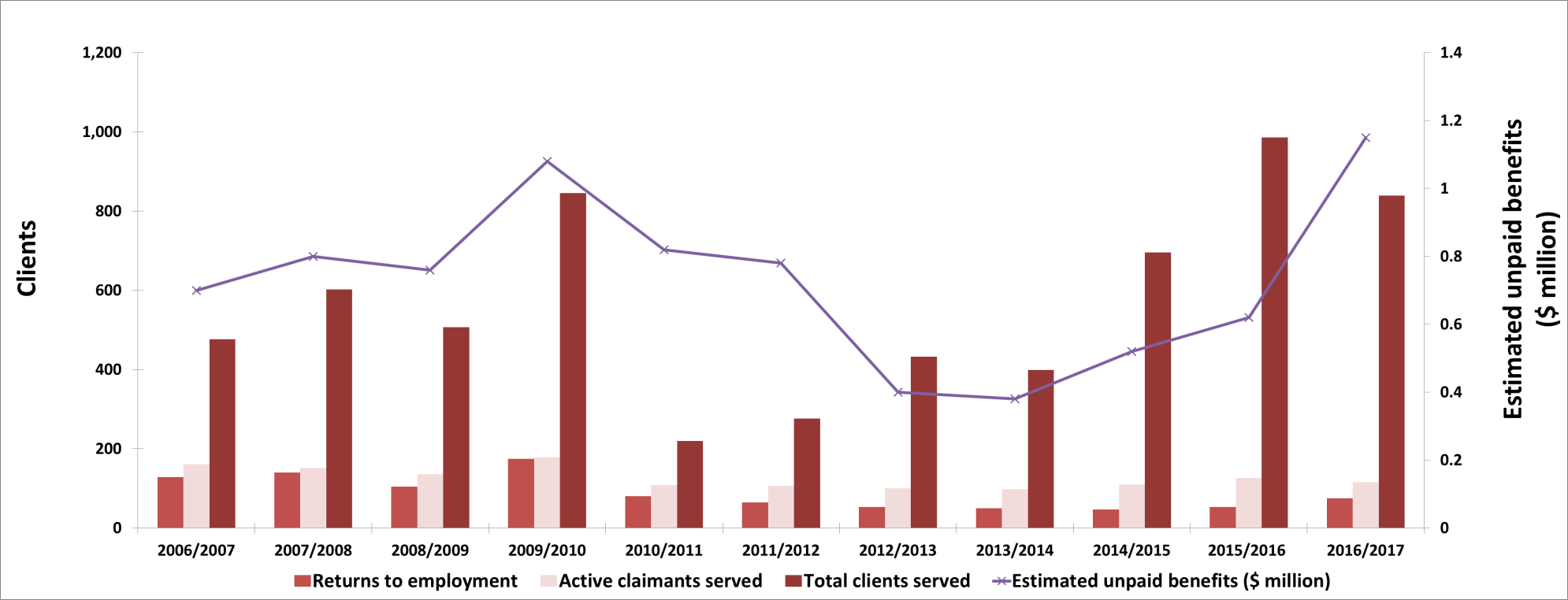

| Returns to employment | Active claimants served | Total clients served | Estimated unpaid benefits ($ million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 8,275 | 14,279 | 19,210 | $24.10 |

| 2007-2008 | 8,856 | 12,648 | 17,464 | $24.00 |

| 2008-2009 | 7,995 | 12,325 | 17,090 | $26.83 |

| 2009-2010 | 6,526 | 13,466 | 18,882 | $32.94 |

| 2010-2011 | 6,857 | 11,215 | 16,134 | $31.20 |

| 2011-2012 | 6,335 | 10,027 | 14,463 | $26.71 |

| 2012-2013 | 6,114 | 9,124 | 13,162 | $30.42 |

| 2013-2014 | 5,918 | 8,831 | 12,739 | $25.69 |

| 2014/2015 | 3,298 | 8,850 | 12,489 | $25.35 |

| 2015-2016 | 3,306 | 8,941 | 12,333 | $22.25 |

| 2016-2017 | 3,696 | 9,308 | 12,352 | $23.23 |

| Interventions | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($ 000s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | ||||

| SD-R | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 3,206 | -2.4% | 95,211 |

| SD-A | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 2,734 | 14.2% | |

| TWS | Newfoundland and Labrador Wage Subsidies | 812 | -9.4% | 5,804 |

| SE | Newfoundland and Labrador Self-Employment Assistance | 236 | -2.9% | 6,186 |

| JCPs | Newfoundland and Labrador Job Creation Partnerships | 1,524 | +26.8% | 9,734 |

| Support Measures | ||||

| EAS | Newfoundland and Labrador Employment Assistance Services | 17,926 | +4.4% | 6,252 |

| LMPs | Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | 2,924 |

| R&I | Research and Innovation | n/a | n/a | 298 |

Job Creation Partnership participation leads to seasonal employment for Tina

Tina lives in a small, rural community in Newfoundland and Labrador with high unemployment and limited employment prospects. A community organization in the area was approved under the JCP program to hire a Program Coordinator/Recreation Director to develop, coordinate and implement a community recreation plan with structured programming for children and youth in the community. The sponsor hired Tina and, during the 20 week program, Tina gained valuable skills with the organization. The project was so successful that Tina was employed for 20 weeks following the end of the JCP program and the organization now intends to rehire Tina for full-time seasonal employment.

Employment Benefits

Newfoundland and Labrador implemented a total of 8,512 Employment Benefit interventions in FY1617, representing a year-over-year increase of 6.1%.

- JCP grew by 26.8% to 1,524 interventions;

- SD-A grew by 14.2% to 2,734 interventions;

- SE declined by 2.9% to 236 interventions;

- TWS declined by 9.4% to 812 interventions; and

- SD-R declined by 2.4% to 3,206 interventions.

Employment Benefits expenditures reached $117.0 million (+3.4%). The province utilized some of its supplemental investment in LMDA funding from Budget 2016 to increase SD and SE expenditures to support growing demand for individuals participating in these two benefit types.

Support Measures: EAS

In FY1617, EAS interventions rose by 4.4% to 17,926 in Newfoundland and Labrador. While Individual Counselling grew considerably by 70.1% to 6,006; Employment Service dropped by 2.3% to 8,014; and Group Services declined by 28.1% to 3,906. Total EAS expenditures rose for a third consecutive year, increasing by 18.8% in FY1617 to $6.3 million.

Other Support Measures

Compared to FY1516, LMPs expenditures increased significantly in FY1617 by 130.1% to $2.9 million. This was attributable to an increased effort in Newfoundland and Labrador to develop partnerships in implementing labour market strategies and activities for labour force adjustment and human resource requirements.

R&I was delivered for the first time in Newfoundland and Labrador, through start-up funding of $300,000 to establish a new Workforce Innovation Centre at the College of the North Atlantic's Corner Brook campus. The Centre will support and fund activities, research, designs and innovative projects to identify methods to better assist individuals prepare for, find, return to, or maintain sustainable employment.

2.3 Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island's real GDP expanded by 2.3% in 2016, supported by gains in construction, manufacturing, real estate, health care and social assistance, as well as retail trade. The province's real GDP is expected to advance at a similar pace in 2017.

Prince Edward Island : EBSM key facts

| EI clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

3,507 |

1,893 |

| Interventions type | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 2,435 | 14.3%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 6,059 | 3.4%  |

| Interventions type | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 28.7% | 3.3  |

| Support Measures: EAS | 71.3% | 3.3  |

| Total expenditures | 2016-2017 ($ million) | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $21.1 | 12.4%  |

| Support Measures: EAS | $3.5 | 19.8%  |

| LMPs and R&I | $1.5 | 32.0% |

| Total expenditures1 | $26.1 | 3.1% |

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $6.99 | $7.14 | 2.1%  |

- 1 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

In contrast to its resilient economy, Prince Edward Island's labour market conditions have been relatively soft over the past few years. In FY1617, the province's employment level declined by 800 (-1.1%), mostly in full-time work. The unemployment rate remained unchanged at 10.5%, the second highest among all provinces.

Prince Edward Island is addressing its growing population of ageing workers, to ensure that residents have the skills to meet the needs of an increasingly knowledge-based economy. Therefore, the province is providing relevant educational and work experience programs to prepare its workforce for the new opportunities brought on by the changing labour market landscape. As well, the province is developing strategies to retain its youth, and integrate highly skilled immigrants. The province will continue to promote entrepreneurship through investment supports for unemployed individuals who wish to launch a business.

Managing for results

Prince Edward Island engages and consults with employers, industry associations, educational institutions and other key partners on an ongoing basis to solicit input on matters related to active labour market programming. This engagement process ensures alignment between strategic priorities and the workforce development needs of the province. In July 2016, Prince Edward Island held a Stakeholder Roundtable Consultation on the Labour Market Transfer Agreements with approximately 50 stakeholders. In addition, through the Atlantic Workforce Partnership, the four Atlantic Provinces convened and hosted 10 sessions, primarily in the form of roundtable discussion workshops, with 275 individuals from 198 organizations across Atlantic Canada.

Clients, interventions and expenditures

In FY1617, Prince Edward Island served 5,400 clients (+3.6%), compared to 5,214 in FY1516.

- Active claimants declined by 2.7% to 2,798 clients;

- Former claimants rose by 7.9% to 709 clients; and

- Non-insured clients rose by 12.6% to 1,893 clients.

The shares also shifted in the same direction as the absolute numbers,

- Active claimants' proportion declined by 3.3 percentage points to 51.8%;

- Former claimants edged up by 0.5 percentage points to 13.1%; and

- Non-insured clients climbed by 2.8 percentage points to 35.0%.

For a third consecutive year, the province delivered a growing number of interventions, reaching 8,494 (+1.1% year-over-year) in FY1617. Employment Benefits interventions accounted for 28.7% of all EBSM-similar interventions and EAS interventions reached 71.3%. Unpaid benefits jumped by 2.1% to $7.14 million. A total of 2,081 (+4.2%) clients were employed after participation in the program. Total expenditures for EBSM-similar programming jumped from $25.3 million in the previous year to $26.1 million in FY1617, this represented an increase of 3.1% year-over-year. About $1.2 million of total expenditures represented Prince Edward Island's share of the $125 million additional LMDA funding announced in Budget 2016. Most of this additional funding was invested in Employment Benefits.

Show Data Table

| Active clients | Former clients | Non-insured clients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 2,846 | 560 | 868 |

| 2007-2008 | 2,898 | 557 | 918 |

| 2008-2009 | 3,035 | 512 | 1,072 |

| 2009-2010 | 2,740 | 487 | 885 |

| 2010-2011 | 2,882 | 572 | 1,071 |

| 2011-2012 | 2,921 | 574 | 1,340 |

| 2012-2013 | 3,032 | 708 | 1,316 |

| 2013-2014 | 2,963 | 703 | 1,285 |

| 2014/2015 | 2,709 | 621 | 1,470 |

| 2015-2016 | 2,876 | 657 | 1,681 |

| 2016-2017 | 2,799 | 709 | 1,893 |

Show Data Table

| Youth (15 to 24) | Core-age (25 to 54) | Older workers (55+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 1,080 | 2,543 | 274 |

| 2007-2008 | 1,003 | 2,645 | 323 |

| 2008-2009 | 1,060 | 2,784 | 323 |

| 2009-2010 | 950 | 2,504 | 275 |

| 2010-2011 | 1,124 | 2,705 | 312 |

| 2011-2012 | 1,202 | 2,937 | 364 |

| 2012-2013 | 1,265 | 3,023 | 446 |

| 2013-2014 | 1,259 | 2,920 | 463 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,276 | 2,776 | 438 |

| 2015-2016 | 1,456 | 2,954 | 508 |

| 2016-2017 | 1,542 | 3,138 | 458 |

Show Data Table

| Returns to employment | Active claimants served | Total clients served | Estimated unpaid benefits ($ million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2007 | 2,033 | 2,846 | 4,274 | $5.80 |

| 2007-2008 | 2,148 | 2,898 | 4,373 | $7.10 |

| 2008-2009 | 2,186 | 3,035 | 4,619 | $7.69 |

| 2009-2010 | 1,839 | 2,740 | 4,112 | $8.92 |

| 2010-2011 | 2,159 | 2,882 | 4,525 | $9.07 |

| 2011-2012 | 2,034 | 2,921 | 4,835 | $8.16 |

| 2012-2013 | 1,939 | 3,032 | 5,056 | $7.53 |

| 2013-2014 | 2,194 | 2,963 | 4,951 | $7.19 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,934 | 2,709 | 4,800 | $6.52 |

| 2015-2016 | 1,997 | 2,876 | 5,214 | $6.99 |

| 2016-2017 | 2,081 | 2,799 | 5,401 | $7.14 |

| Interventions | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($ 000s) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | ||||

| SD-R | Training PEI—Individual | 1,070 | -3.2% | 14,479 |

| SD-A | Training PEI—Apprentice | 295 | -4.8% | |

| TWS | Employ PEI | 832 | +49.6% | 4,060 |

| SE | Self-Employ PEI | 170 | +23.2% | 2,008 |

| JCPs | Work Experience PEI | 68 | +209.1% | 601 |

| Support Measures | ||||

| EAS | Employment Assistance Services | 6,059 | -3.4% | 3,461 |

| LMPs | Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | 1,344 |

| R and I | Research & Innovation | n/a | n/a | 124 |

Employment Benefits

Compared to the previous reporting period, Employment Benefits expanded by 14.3% to 2,435 interventions in FY1617. Participation in all types of interventions changed including,

- SD-R which slowed down by 3.2% to 1,070 interventions;

- SD-A which dropped by 4.8% to 295 interventions;

- TWS which increased by 49.6% to 832 interventions;

- SE which rose by 23.2% to 170; and

- JCP which climbed by 209.1% to 68.

Prince Edward Island spent a total of $21.1 million (+12.4%) on Employment Benefits, where TWS received the majority of the province's share of additional LMDA funding from Budget 2016. The rise of TWS interventions and expenditures fulfills the increased demand for employer-sponsored training, such as EmployPEI and the Graduate Mentorship Program.

Jenna's journey to sustainable employment

Jenna was interested in exploring new career options in trades and increasing her employability skills. She was able to find her dream job by progressing along a path to sustainable employment which included:

- Career exploration via a program offered by the Women's Network PEI;

- Training to develop skills needed to succeed in the workforce by enrolling in and graduating from the Heritage Retrofit Carpentry program; and

- An opportunity to bridge education with work experience through the Graduate Mentorship program.

With a lot of perseverance and support from the province, Jenna developed new skills and abilities that will contribute to the success of the renovations at the historic Province House in Charlottetown.

Support Measures: EAS

Total EAS interventions fell from 6,271 in FY1516 to 6,059 in FY1617, a 3.4% year-over-year drop. This was a result of the 23.6% decrease in Individual Counselling interventions. On the other hand, Employment Services edged up by 3.1% to 4,897, while EAS expenditures reached $3.5 million, a decrease of 19.8%.

Other Support Measures: LMPs and R&I

In FY1617, LMPs and R&I funding dropped for a second consecutive year, by 32.0%, to $1.5 million. Both LMPs ($1.3 million) and R&I ($124,000) funding declined by 31.3% and 39.2%, respectively.

2.4 Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia's real GDP grew by 0.8% in 2016, slower than the 1.4% increase in 2015. This continued growth is supported by gains in real estate, construction, and manufacturing. Real GDP growth is projected to moderately strengthen in 2017, backed by increases in home starts, tourism and non-energy exports. However, this projected growth remains considerably below the expected national average of 3.0%.

Compared to FY1516, overall employment in FY1617 remained relatively unchanged (-300; -0.1%), the decline in full-time work (-5,600; -1.5%) was the largest recorded by the province since FY9293. A gain in the services-producing sector (+2,500; +0.7%), was more than offset by a loss in the goods-producing sector (-2,700; -3.3%). Employment growth was led by the following industries:

- Trade increased by 4.0% (+2,800); and

- Health care and social assistance increased by 2.8% (+2,100).

The 0.5 percentage points decrease (from 8.6% in FY1516 to 8.1% in FY1617)in Nova Scotia's unemployment rate was due largely to an increased number of people exiting the labour force. The participation rate dropped from 62.3% in FY1516, to 61.6% in FY1617, the second lowest among Canadian provinces.

Nova Scotia : EBSM key facts

| EI clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

11,792 |

4,717 |

| Interventions type | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 4,450 | 7.8% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 28,618 | 2.1% |

| Interventions type | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 13.5% | 0.6 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 86.5% | 0.6 |

| Total expenditures | 2016-2017 ($million) | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $48.3 | 2.7% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $32.1 | 19.2% |

| LMPs and R&I | $2.9 | 44.0% |

| Total expenditures1 | $83.3 | 6.0% |

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $23.39 | $24.02 | 2.7% |

- 1 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

With an ageing workforce and changing economic environment, a well-trained and flexible labour force is increasingly in demand. Nova Scotia's labour market priorities ensure that both the current workforce and new entrants have the right skills to meet employers' expectations. To mitigate the ongoing shrinking labour force and to increase workplace productivity, the province will focus on raising the workforce participation of priority groups facing significant barriers; including older workers, Indigenous peoples, African Nova Scotians, persons with disabilities, and Acadian Nova Scotians. The province will also introduce the Nova Scotia Research and Innovation Measure, to identify new and innovative ways to deliver labour market programs and services to Nova Scotians. In July 2016, the province implemented the Nova Scotia Works program, transforming the previous Careers Nova Scotia (Employment Assistance Services) program to better meet program administration cost savings and service delivery reach goals.

Managing for results

In an effort to standardize employment services offered to Nova Scotians throughout the province, and increase the share of funding allocated to direct clients supports, the province adopted the Nova Scotia Works service system. Replacing Careers Nova Scotia Centres, the Nova Scotia Works platform was launched in FY1617 to provide consistent EAS employment services to Nova Scotians, in an innovative and efficient manner. With input from service providers, a more structured approach was developed for assessing client service needs and directing them to the proper service plan. The Client Pathway process utilizes common assessment tools to determine job readiness, by identifying employment barriers, and moving clients into the most relevant service stream. Preliminary performance results of this new service delivery platform, show an increase in clients served, clients employed, clients employed full-time, and clients employed in their preferred field. Nova Scotia Works also improves the collaboration with the employer community, through the new Employer Engagement Specialist located in each Nova Scotia Works service provider.

Clients, interventions and expenditures

The number of clients served in Nova Scotia rose from 16,329 in FY1516 to 16,509 in FY1617. This represented a year-over-year increase of 1.1%. All three client-types changed,

- Active clients grew by 0.8% to 9,651 claimants;

- Former clients grew by 0.3% to 2,141 claimants; while

- Non-insured clients shrank by 2.1% to 4,717 claimants.

The share of each client type remained relatively stable compared to the previous year.

- Active claimants' share decreased by 0.2 percentage points to 58.5%;

- Former claimants' share decreased by 0.1 percentage points to 13.0%, while

- Non-insured clients rose by 0.3 percentage points to 28.6%.

Nova Scotia delivered 33,068 EBSM-similar interventions in FY1617, a 2.9% increase from FY1516. Employment Benefits reached 13.5% of all interventions, while EAS declined to 86.5%. A total of 5,133 clients returned to employment after participating in an EBSM-similar programming, compared to 5,100 clients from the previous period. Unpaid benefits amounted to $24.02 million (+2.7%), while total EBSM expenditures reached $83.3 million (+6.0%). This included Nova Scotia's $4.9 million share of the $125 million LMDA additional funding announced in Budget 2016.

Show Data Table

| Active clients | Former clients | Non-insured clients | |

|---|---|---|---|