Many Voices One Mind: a Pathway to Reconciliation

Welcome, Respect, Support and Act to Fully Include Indigenous Peoples in the Federal Public Service

Final Report of the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation

December 4, 2017

Summary Report of Departmental Progress Scorecard Findings

The Summary Report of Departmental Progress Scorecard Findings is a summary of the implementation of the Many Voices One Mind Action Plan that highlights the accomplishment and promising practices reported by departments and agencies. This report also shines a light on the areas that require additional focus and efforts moving forward.

In 2017, Gina Wilson, Canada’s federal Deputy Minister Champion for Indigenous Federal Employees, led the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation. Through consultations with current and past federal public servants, they sought to better understand the challenges and barriers faced by Indigenous Peoples within the Public Service.

The Circles received over 2,100 responses from Indigenous employees across the country, who shared their experiences and advice on how to improve the Public Service work experience for Indigenous employees.

As a result, the Circles developed a strategy—outlined in this report. The five main objectives are to:

- Encourage and support Indigenous Peoples to join the Public Service

- Address bias, racism, discrimination and harassment, and improve cultural competence in the Public Service

- Address learning, development and career advancement concerns expressed by Indigenous employees

- Recognize Indigenous Peoples’ talents and promote advancement to and within the executive group

- Support, engage and communicate with Indigenous employees and partners

While there is still much work to be done to ensure all Indigenous public servants feel supported and included, this report is an important step on our path to supporting the incredible potential Indigenous public servants bring to our workplace. Now is the right time to address barriers that limit diversity and inclusion, which have no place in the Public Service.

If you would like to join the conversation, please use #ManyVoices on Twitter.

Executive Summary

Indigenous Peoples face real barriers at each stage of the Public Service employment process. Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation is a whole-of-government strategy that seeks to reduce and remove barriers to Public Service employment encountered by Indigenous Peoples; and capitalize on the diversity of experience and ideas that Indigenous Peoples bring to the Public Service.

The Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation was launched as a platform for action on September 15, 2016, with the support of Deputy Heads and the Clerk of the Privy Council. This innovative interdepartmental team was mandated to devise a strategy to address the barriers encountered by Indigenous people seeking and living a Public Service career. Three bodies make up the team: A Steering Circle of Deputy Heads; a Collaboration Circle made up of a mix of senior executives from a variety of departments; and a Support Circle: a small multi-disciplinary team that provides support to the other two Circles.

The Strategy to Welcome, Respect, Support and Act to Fully Include Indigenous Peoples in the Federal Public Service is designed to provide tangible actions that individuals and organizations can implement, taking into consideration the unique context, operating environment and prior knowledge in each different situation.

Barriers to employment were identified in consultation with Indigenous employees and stakeholders. A third-party quantitative survey of approximately 2,200 current and former Indigenous employees was conducted. The results were validated and supplemented using qualitative Dialogue Circles, encouraging Indigenous employees to tell the stories that shape their Public Service employment experience.

The overall findings from both the survey and the Dialogue Circles indicate that appropriate cultural awareness training is essential to building a workplace that is supportive, respectful and inclusive. As well, the responses indicate that Indigenous employees are looking for three types of learning and development supports: more training and development opportunities; feeling and being part of a network of Indigenous employees, and mentorship opportunities. All participants said that the key factor that attracted them to the Public Service was an opportunity to make a difference for Indigenous Peoples and their own communities.

The survey represents the first time that current and former Indigenous public servants from across Canada, at all different levels, have been engaged from within the Public Service on the issues of Indigenous recruitment and retention. The perspectives in this report were gathered through both quantitative and qualitative research. They provide a strong baseline of evidence for individuals and organizations to use in support of taking actions to make their workplaces more inclusive of Indigenous employees.

The strategy outlines four main objectives:

- Encourage and support Indigenous people to join the Public Service

- Address bias, racism, discrimination and harassment, and improve cultural competence in the Public Service

- Address learning, development and career advancement concerns expressed by Indigenous employees

- Manage Indigenous talent and promote advancement to and within the Executive Cadre

A fifth objective—Support, engage and communicate with Indigenous employees and partners—is an important principle for advancing each of the four objectives. Taken together, the objectives of the Strategy are designed to improve workplace satisfaction for Indigenous employees, increase the awareness of the workplace climate and improve championing of Indigenous employees.

Each objective offers options for action to enhance current practices, offer opportunities for immediate improvements, and effect a transformational change. The full list of actions can be found in Section 5 of the final report.

We aspire to a federal public service that is…..

Text version

Nonjudgmental representation enjoyable reconciliation discrimination compassion unbiased teamwork formation calm non-discriminatory patient considerate nonjudgemental empathetic dignity honesty knowledgeable leadership harmonious good recognition accepting valued holistic interested sensitive equality safe caring language elder communication diversity flexible diversité advancement positive inclusivity equitable empathy sincere listen developmental tolerant fair honour équité kind respectful team growth relaxed growth humility helpful network balanced intégrité work trust supportive honest adaptive free aboriginal awareness cultures encouraging openess receptive history equity openness mentoring family know friendly opportunity reconnaissance cooperative patience healthy productive openminded less respectueux professional accessible management ouverture mentorship confiance rewarding compassionate ouvert curious spiritual accountability barrierfree multicultural

Message from Gina Wilson, DM Champion for Indigenous Federal Employees

I am always grateful to my people and the Algonquin Nation, on whose traditional territory we are able to do good work.

Over the last year, I have had the honour to lead the work of the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation. In doing so, I have had the privilege of listening to Indigenous Peoples, bargaining agent representatives, public servants at all levels, and former public servants who still care about the Public Service workplace. By listening, I have learned how passionate and committed so many are to make the Public Service of Canada a workplace where Indigenous Peoples feel welcomed, respected, and supported, and where action is taken to ensure they are fully included in the workplace. This report brings together the views shared by many voices, with a single-minded purpose of achieving a better Public Service workplace for Indigenous Peoples. The actions and outcomes outlined in this report are a pathway to reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. I look forward to walking that pathway.

Successfully completing a project of this kind requires the leadership, commitment and effort of many people. I extend appreciation to everyone who had a hand in the success of this project. Special thanks are extended to:

The Steering Circle for their leadership on this important file: Anne Marie Smart (CHRO), Wilma Vreeswijk (CSPS), Christine Donoghue and Patrick Borbey (PSC), Carolina Giliberti (CFIA), Don Head (CSC), Hélène Laurendeau (INAC) and Janine Sherman (PCO).

The Collaboration Circle under the leadership of Patrick Boucher (Chair) for their commitment and perseverance in staying focussed on action and achieving results: Keith Conn (HC), Luc Dumont (INAC), Brian T. Gray (AAFC), Peter Hill (CBSA), Michelle Langan (CSC), Catherine MacQuarrie (IPAC), Frances McRae (PCO), Rob Prosper (Parks), Sean Ross, Camille Bouchard and Karine Renoux (INAC), Manon Tremblay (PSC), Margaret Van Amelsvoort-Thoms (OCHRO), Shirley Anne Off (Justice) and Danielle White (INAC).

The Support Circle under the leadership of Nadine S. Huggins, Director and Executive Secretary to the Circles, for creatively and thoroughly meeting multiple demands to get the work of this project done collaboratively, with analytical rigour and within the expected timeframe: Heather Mousseau (CBSA), Karol Gajewski (Free Agent).

Finally, thank you to Lee Seto-Thomas for sharing the Many Voices One Mind teaching, which stems from Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) philosophy.

Gina

Why a Strategy on Indigenous Representation Now?

Achieving a Public Service where Indigenous Peoples feel included is timely. It is in line with the Government’s broad Reconciliation agenda, defined by renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government, and Inuit-Crown relationships with Indigenous Peoples.

The Public Service is ripe for transformation. Canada enjoys a strong and evolving human rights legislative foundation. It includes the Employment Equity Act, the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Public Service Employment Act, which requires that the Public Service be representative of the populations it serves.

We operate in a climate where Deputy Heads are able and encouraged to exercise flexibility and creativity to attract, develop and retain human resources to meet the current and future needs of their organizations. All of this can be achieved within existing delegated authorities.

- Diversity: The array of identities, abilities, backgrounds, skills, perspectives and experiences that are representative of Canada’s current and evolving population.

- Inclusive workplace: An inclusive workplace is fair, equitable, supportive, welcoming and respectful. It recognizes, values and leverages differences in identities, abilities, cultures, backgrounds, skills, experiences and perspectives that support and reinforce the evolving human rights framework.

- Indigenous: First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples living in the country known as Canada.

Canada’s Public Service is recognized as a world leader. It is celebrated for its professionalism, efficiency and stability. Canada’s diversity is a recognized strength. It is time to take bold, strategic and deliberate actions to enhance and capitalize on that strength. Fully including Indigenous Peoples in Canada’s Public Service will enhance Canada’s ability to identify itself as a fully inclusive workplace.

Indigenous people face real barriers at each stage of the Public Service employment process. Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation is a whole-of-government strategy that seeks to:

Reduce and remove barriers to Public Service employment encountered by Indigenous People; and

Capitalize on the diversity of experience and ideas that Indigenous Peoples bring to the Public Service.

Many Voices One Mind – Developing the Strategy

Gina Wilson, Deputy Minister Champion for Indigenous Federal Employees, launched work to develop a strategy for Indigenous representation in the Public Service in September 2016. The Clerk of the Privy Council, the Public Service Commission of Canada (PSC), the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO), the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS) and Deputy Heads from across the system collaborated to design an innovative approach to identify and analyze barriers to employment. The aim was to deliver actionable solutions to address why Indigenous employees continue to express dissatisfaction with their Public Service employment experience.

The Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation was launched as a platform for action. Three bodies make up this innovative interdepartmental team:

- A steering Circle of Deputy Heads;

- A Collaboration Circle made up of a mix of executives from a variety of departments; and

- A Support Circle which is a small multi-disciplinary team that provides analysis, coordination, integration across activities, and report writing support to the Steering and Collaboration Circles.

Together, the Interdepartmental Circles defined a unifying vision: to achieve a Public Service that welcomes, respects, supports and acts to fully include Indigenous people seeking and living a Public Service career.

The work of the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation is grounded by an integrated evidence base as well as Indigenous employee input and engagement. A partial list of activities pursued to establish a solid foundation for the Strategy includes:

- Advice from internal and external experts;

- Data about the current state of Indigenous representation across the largest occupational categories and within the Executive Group of the Public Service, compiled by the Public Service Commission of Canada, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Statistics Canada;

- External professional research on best practices in recruiting and retaining Indigenous Peoples;

- Outreach to employees and employee networks across a number of departments for input and feedback at each stage of the Strategy development process;

- Interventions by Indigenous public servants and other stakeholder groups;

- Input from bargaining agent representatives;

- An inventory of current Public Service initiatives that align with proven best practices; and

- A survey of current and former Indigenous employees.

This final report and Strategy is based on qualitative and quantitative information.

Specifically, this final report:

- Outlines projections that will impact the Public Service context;

- Summarizes what we know about Indigenous representation in the non-executive and executive ranks;

- Outlines research into best practices to address the unique situation of the Inuit;

- Reports on promising action currently underway in organizations; and finally,

- Presents Many Voices One Mind: a Pathway to Reconciliation—a whole-of-government strategy on Indigenous representation.

1. The Public Service Context – Projections

Statistics Canada demographic and labour market projections to 2031 suggest that:

- The Canadian population is aging but when analysis is done by region, important variations in this trend are observed. In the Prairie provinces and Territories—where high numbers of Indigenous Peoples reside, individuals aged 0-14 are projected to continue to outnumber those who are 65+.

- By 2031, the percentage of the population who self-report an Indigenous identity will increase from 5% to 6%. This represents an increase of approximately 778,000 people.

- The share of people reporting an Indigenous identity in Central Metropolitan Areas located in the Prairies and Territories is expected to rise and, in places like Brantford, Sudbury and Thunder Bay, Indigenous Peoples will continue to outnumber members of visible minority groups.

- The size of the Canadian labour force is shrinking. In the face of an increase in the share of the population aged 25-64 declaring an Indigenous identity, Indigenous Peoples are expected to make up a larger share of the future labour force.

- The percentage of Indigenous Peoples completing a university education will increase, but is expected to remain below the Canadian average rate of 64% (2011 Statistics Canada data).

- Immigration will continue to redefine Canada’s population.

- To be effective, public servants require competencies in the areas of social interaction, collaboration, managing diversity and maintaining an inclusive workplace.

Conclusions:

- The demographic composition of Canadian society is changing and these changes may influence social norms and perceptions.

- Regardless of the context in which it operates the Public Service is expected to consistently reflect and promote fairness, professionalism, non-partisanship and representativeness.

- Respect, support and full inclusion of Indigenous Peoples are and will remain, aligned with core Public Service ideals.

2. Representation of Indigenous Peoples in the Public Service of Canada

Barriers to employment

Indigenous Peoples encounter various barriers that affect their ability to access and successfully navigate employment within the Public Service. The barriers outlined in Annex 1 were identified, further defined and validated with Indigenous employees and other stakeholders. Consultations were held and input was received from:

- The Aboriginal Executive Network;

- The Champions and Chairs Circle for Aboriginal Peoples (CCCAP);

- Indigenous employees at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canada Border Services Agency, Correctional Service Canada, and the former Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; and

- Indigenous employees who responded to a whole-of-government survey on Indigenous retention.

Indigenous Employees’ Views and Experiences– Results of the Indigenous Workforce Retention Survey

To ensure Indigenous employees were directly engaged in developing the Strategy, a research consulting firm was hired to survey current and former Indigenous employees about:

- Issues related to recruitment, professional development and long-term retention;

- Opportunities and challenges faced by Indigenous employees in the Public Service workplace; and

- Former Indigenous public servants’ reasons for leaving the Public Service.

The Indigenous Workforce Retention Survey had a quantitative online phase—approximately 2,200 current and former Indigenous public servants from across the country responded. Online survey results were validated and supplemented using a qualitative Dialogue Circle approach. Current and former public servants from across the country shared their experiences and views. Annex 2 outlines the methodology and approach used for the survey, and includes a summary of key findings.

“As an Indigenous employee I do not want to feel called upon or feel personally responsible to educate, demystify inaccuracies, counter stereotypes and defend Indigenous Peoples, their histories and cultures”

“I was required to take an IQ test as part of an assessment process I participated in. I found out later that non-Indigenous applicants were not required to do this”.

Through the survey research, Indigenous public servants provided a window into the impacts of the barriers they face. They also shared their views about which policies, programs and supports are needed to improve their workplace experiences.

Dialogue Circle discussions were particularly rich as they encouraged current and former Indigenous employees to tell the stories that shape their Public Service employment experience. The following observations are drawn from Dialogue Circle discussions:

- Most participants seem to have entered the Public Service through a student program (Federal Student Work Experience Program or the former Native Internship Program) or through Public Service work fairs.

- All participants said that the key factor that attracted them to the Public Service was an opportunity to make a difference for Indigenous Peoples and their own communities. Job stability, good pay and benefits were other key factors.

- The issue of self-identification was discussed as an important and difficult issue to resolve. Specific issues included questions about whether everyone who self-identifies is truly an Indigenous person and how identity should be assessed; whether self-identification creates barriers as an individual seeks to move up the ranks and into the Executive Group; whether self-identification results in an employee being pigeonholed in work related to Indigenous issues; and whether non-Indigenous Peoples falsely self-identify, thus denying Indigenous employees career progression opportunities.

- Participants frequently spoke about the challenges faced in trying to advance their careers. Processes are seen as neither transparent nor considerate of Indigenous cultural values. A number of participants stated that they failed the “personal suitability” section. Two noted that they ranked a zero on personal suitability and said how emotionally harmful that was.

- Participants view the hiring process as bureaucratic and burdensome, particularly as they feel they lack knowledge of “how to play the game.” Participants also gave examples of how they have been required to meet different expectations than non-Indigenous applicants in hiring processes.

- Participants said that there was a serious lack of training and development opportunities available to them, often due to limited time or money allotted. They highlighted poor support from managers to pursue further education, language training and leadership development. One participant noted “my manager told me –you know the rest of us have to pay for our own degrees.”

- Many participants suggested establishing separate training platforms for Indigenous employees so that they benefit from having the support, comfort and network of fellow Indigenous employees. Participants also believe that separate training would be more culturally sensitive.

- The majority of participants welcomed the possibility of more structured mentorship opportunities where both the mentor and mentee have set clear outcomes for the relationship.

- All groups expressed gratitude for the opportunity to work for the federal government and recognize that they have been part of interesting and important work. While participants are hopeful that recent commitments and the increased focus on Indigenous Peoples will translate into concrete and meaningful actions, they also remain skeptical about this.

- Participants recommended a reduction in the requirements for French as a second language, particularly when working with English-speaking Indigenous communities. They advocate recognizing their Indigenous language and offering an equivalent of a bilingual bonus to those who use an Indigenous language in positions that deal with Indigenous communities.

- Participants expressed a sense of being “tokenized.” They felt that they must constantly defend or explain Indigenous histories and cultures to non-Indigenous colleagues. Indigenous employees mentioned that senior leaders seek them out for photo opportunities. However, they did not feel they were called upon to share their Indigenous experience and knowledge when it really matters, for example, when designing a policy or program intended for Indigenous communities and peoples.

- Finally, participants discussed the need for more leadership and effective Champions for Indigenous employees. Participants emphasized that this is particularly needed when workplace reductions are in play. Many participants noted that they feel that Indigenous employees were disproportionately terminated during the last round of Public Service staff reductions.

“I feel taken advantage of by senior government officials and ministers, who want a ‘token’ photo with an Indigenous person”

Indigenous employees who have worked for the Public Service between 5 to 10 years have critical workplace needs. They feel emphasis is exclusively on recruitment when they face a lack of career advancement and mobility. They also feel that there is an inconsistent application of policies—particularly those related to staffing.

“I have had many good experiences over the years that have had big impacts but those windows for going in and making a change or having an impact have become increasingly more difficult to do as the years went by—it is starting to get harder to have an influence on decisions that impact Indigenous people”

The survey results conclude:

- More can be done to support Indigenous employees through the recruitment process. Approximately half of current and former Indigenous employee respondents indicated an understanding of how the recruitment process works. Further, just over half of current Indigenous employee respondents strongly agree / agree that they have a high level of satisfaction with the recruitment process (less than 50% of former employees felt this way). Most noteworthy is that 56% of current and 43% of former employees strongly agreed / agreed that their first position in the Public Service was what they expected.

- Indigenous employees seek a workplace that is supportive, respectful and inclusive. They do not wish to be required, in the absence of appropriate cultural awareness training, to educate their colleagues about Indigenous histories and cultures. Nor do they want to feel responsible for dispelling stereotypes that should be addressed using a systemic approach.

- Indigenous employees are looking for three types of learning and development supports: more training and development opportunities (especially in the areas of leadership development); feeling and being part of a network of Indigenous employees; and mentorship opportunities.

- Lack of access to (mainly French) language training and challenges associated with the language requirements of most positions frequently become a barrier to advancement for Indigenous employees.

- The satisfaction among Indigenous employees is low—56% of Indigenous employees reported being very satisfied / satisfied with their employment. Forty percent of current employee respondents indicated they were planning to leave their current position. Current employees’ top reason for thinking about leaving is to gain further experience. The second main reason, however, is a lack of career progression opportunities and the view that some recruitment and promotion processes in their current organization are neither fair nor transparent. How “right fit” is used and and how pre-qualified pools are established and used were specifically cited as areas where employees feel they are subjected to bias and discrimination.

- PSES results indicate that Indigenous employees repeatedly report that they have been victims of discrimination and harassment at almost twice the rate of non-Indigenous employees.

- Indigenous employees who have worked for the Public Service for 5 to 10 years have critical workplace needs.

The Indigenous Workforce Retention Survey results paint a clear picture of how Indigenous public servants experience and view the barriers that impact their work life and career. It is vital to address these issues and prevent adverse experiences.

The current statistical representation of Indigenous public servants serves as an important backdrop. This is described in the next several sections, based on data ending March 2016.

“I completed all the hoops I was told I must get through but then you hit the Indigenous ceiling and get pushed back. There is a point at which being labelled as an Indigenous employee becomes a barrier”.

Statistical Representation of Non-Executive Indigenous Public Servants

Current Indigenous representation in the Public Service is based on the analysis of data from PSC internal administrative systems. The data reflect activity by organizations under the authority of the Public Service Employment Act. The data analysis provides an understanding of hiring and staffing trends; statistical representation rates overall and by occupational group; and mobility and career progression.

There are gaps in Public Service hiring of Indigenous students. Analysis of student recruitment rates over a three-year period (from 2013-14 to 2015-16) shows that the proportion of Indigenous students hired via student programs for summer and/or part-time work fell below the representation rate of Indigenous Peoples across the Public Service. This occurred in spite of a sharp increase in the overall numbers of students hired into the Public Service between 2014-15 and 2015-16. Specifically, of the 19,783 students hired through the Federal Student Work Experience Program between 2013-14 and 2015-16, a total of 570 (2.9%) self-identified as an Indigenous person. During the same period, of the 12, 375 students hired through the CO-OP program, a total of 48 (0.38%) self-identified as an Indigenous person. Finally, of the 1222 students hired through the Research Affiliate Program (RAP), 14 (1.4%) self-identified as an Indigenous person.

There are currently no overall statistical representation gaps for Indigenous Peoples in the Public Service as a whole. This may change when new workforce availability data are released. Over the last 15 years, the statistical representation of Indigenous Peoples in the Public Service has increased, from 3.6% in 2001 to 5.1% in 2015, exceeding their workforce availability. Further, data show that overall hiring rates for Indigenous Peoples into the Public Service have followed the same ebbs and flows as other employment equity designated groups. It should be noted, however, that whole-of-government Indigenous representation rates are largely bolstered by five departments. It should also be noted that about a dozen departments have not achieved full Indigenous representation.

Statistical representation rates for Indigenous Peoples within the largest occupational groups in the Public Service have been stable over the last three years. Moreover, Indigenous Peoples are well represented when compared to population representation (4.3%) and workforce availability (3.4%) rates.

Data as of March 2016 show the following statistical representation of Indigenous employees in the 10 largest occupational groups:

- Administrative Services (AS) – 5.6%

- Border Services (FB) – 3.8%

- Clerical and Regulatory (CR) – 6.7%

- Computer Systems (CS) – 2.9%

- Correctional Services (CX) – 11.4%

- Economics and Social Science Services (EC) – 3.2%

- Engineering and Scientific Support (EG) – 3.7%

- Nursing (NU) – 8.9%

- Program Administration (PM) – 7.1%

- Welfare Programs (WP) – 12.7%

Internal data show that the Public Service is largely statistically representative of Indigenous Peoples at all levels within the largest occupational groups. As will be seen below, a PSC cohort analysis showed a lower rate of promotions for Indigenous employees. However, an analysis of statistical representation by level provides little evidence that Indigenous employees are stagnating at the lower levels within occupational groups. There is some evidence of career progression through lower into intermediate levels within occupational groups.

There are statistical representation gaps in science-based occupational groups, and in the more senior levels of the EC category.

In terms of mobility and career progression:

- The appointment rate of Indigenous employees into non-Executive Public Service positions through external indeterminate appointments is steady at approximately 5%.

- Term to indeterminate appointments for Indigenous employees are steady at approximately 6% each year. There was a slight decline in the rate of recruitment for external term appointments greater than three months, from 4.4% in 2013-14 to 3.4% in 2014-15.

- Acting opportunities are regarded as preparation and as a precursor of promotion. Indigenous employees attained acting opportunities at a rate of approximately 4.6% and acquired approximately 4.2% of promotions.

- The PSC conducted a mobility cohort analysis of individuals who were appointed to their first indeterminate position in 2011-12 and followed them through the system from 2012-13 to 2015-16. The mobility of 493 Indigenous employees and 7,631 non-Indigenous employees was analyzed.

- Analysis revealed that Indigenous employees in the cohort were promoted at a lower rate (19.9%) than employees not self-identifying as an Indigenous person (25.4%). Further, Indigenous employees within the cohort had a slightly higher rate of lateral transfers (25.2%) than employees not self-identifying as an Indigenous person (24.7%).

Access to Public Service employment may not be seen as an immediate challenge for Indigenous Peoples. However, the experiences of discrimination, harassment, exclusion, and career stagnation expressed by Indigenous employees provide some insight into why there is a general malaise among Indigenous public servants. To keep pace with population growth projected by Statistics Canada and to maximize the economic inclusion of all populations, innovating to enhance representation of Indigenous Peoples in the Public Service will help generate important results for all people living in Canada. It is essential that efforts to recruit Indigenous talent be maintained and enhanced.

Statistical Representation of Indigenous Executives

Current Indigenous representation in the in the Executive Group is based on the analysis of data provided by the PSC administrative systems. The data reflect activity within organizations that fall under the authority of the Public Service Employment Act. The data analysis provides an understanding of hiring and staffing trends; statistical representation rates; and mobility and career progression for Indigenous executives.

Indigenous representation in the Executive Group is explored in terms of a number of variables including:

- Size and composition

- Regional representation

- First official language

- Staffing and appointments, including through external hires, acting opportunities and promotions

A comparison of the representation of Indigenous with non-Indigenous employees in the Executive Group over a five-year period (March 2012-March 2016) is shown in Annex 3.

Between 2012 and 2016 the size of the Executive Group decreased by 10%—from 5,079 to 4,589 employees. Despite this overall reduction, representation of Indigenous employees in the Executive Group remained fairly stable.

Indigenous employees make up approximately 3.7% of the Executive Group. The number of Indigenous people at the most senior levels of the Executive Group (EX 03-05) has remained stable at approximately 25 employees since 2012. There were 145 Indigenous EX 01 and EX 02 employees in 2015-2016.

Indigenous women are consistently represented at higher rates in the Executive Group than Indigenous men. That said, representation of Indigenous female executives declined slightly, from 2.1% in 2011 to 1.9% in 2016. In comparison, representation of Indigenous men among executives remained relatively constant at 1.6% and saw a small increase to approximately 1.8% in 2016.

Summary:

- Indigenous executives have a 3.7% representation in the executive ranks

- Indigenous executives are concentrated in the EX 01, EX 02 and EX 03 levels

- Indigenous executives participated in less than 2% of formal acting opportunities.

- Years at level before promotion are not significantly different compared to all executives

- Rates of promotion for Indigenous employees through the executive ranks is low

- Identified barriers and early recommendations for action were supported and validated through broad consultations.

Regional Representation

The majority of Indigenous employees work outside the National Capital Region (NCR). Between 2011 and 2015, the number of executive positions in non-NCR regions declined from 1,245 to 1,064 (a reduction of approximately 1%). Similarly, the number of Indigenous executives in these regions declined from approximately 63 individuals (5% of the non-NCR Executive Group) in 2011 to 49 individuals (4.6%of the non-NCR Executive Group) in 2015.

Official Languages

The percentage of Indigenous employees hired into the EX 01 category who identify English as their first official language increased slightly, from approximately 69% in 2012 to 71% in 2016. During the same period, there was a corresponding decline in the percentage of Indigenous executives who identify French as their first official language, from 30.7% to 28.8%. Almost without exception, Executive Group positions have official bilingual requirements.

Access to language training and its relation to career progression are issues that need to be addressed.

Staffing and Appointments

External Appointments

Most executives in the Public Service are promoted from within. External hires are infrequent. A total of 287 external hires were made between 2011 and 2016. Of that number, 110 were women and 177 were men. The number for external hires of Indigenous Peoples into the Executive Group is very low. It cannot be reported because the group is so small and anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Acting Opportunities

Acting opportunities provide important opportunities for development and promotion. When compared to other employment equity groups, Indigenous executives participate in the fewest formal acting opportunities. Indigenous executives participated in approximately 23 (1.7%) of the 1293 formal acting opportunities within the Executive Group (EX 02-05) between 2011 and 2016.

Promotional Appointments

Between 2011 and 2016, 47 (3.7%) of the employees promoted to the EX 01 level were Indigenous employees. Within the same period, 19 (1.2%) of the 1,562 employees promoted to the EX 02 level or higher were Indigenous employees.

No substantial differences were observed between Indigenous and non-Indigenous employees in the average time it takes them to progress through the executive ranks.

3. Research on Best Practices in Recruitment and Retention of Indigenous Peoples

To build on the evidence base and help develop the Strategy, the Circles commissioned a literature review to identify best practices in Indigenous recruitment and retention.

The review uncovered some 50 sources of information. It was concluded that the Public Service is already implementing certain best practices, but with varying degrees of consistency. Best practices in recruitment and retention of Indigenous Peoples include:

- Establishing a representative workforce policy

- Encouraging voluntary self-identification and reporting

- Establishing partnerships with Indigenous organizations

- Establishing specialized recruitment programs

- Pursuing outreach at Indigenous educational and employment events

- Encouraging Indigenous employee networks

- Acknowledging and including Indigenous cultural practices

The literature review also explored the unique circumstances, as well as the recruitment and retention needs of Inuit.

The Unique Characteristics and Needs of Inuit

Recognized in the Canadian Constitution as one of three distinct Indigenous groups in Canada, Inuit are historically, culturally and linguistically distinct from other Indigenous groups. They are also the most recently colonized Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Inuit are disproportionately represented among survivors of residential schools, and many face both intergenerational and ongoing trauma. They are closer to traditional economies than most Indigenous Peoples. On average, Inuit have the lowest education and employment rates, and the highest fertility rate of any Indigenous group.

Inuit also offer strengths and expertise in terms of their knowledge of the land and its ecosystems, but this is often not adequately recognized within the Public Service. It is currently difficult to draw firm conclusions about how Inuit are faring in the Public Service, as their responses to surveys are generally included in the broader “Indigenous Peoples” category.

Just under half of Inuit in Canada live in Nunavut. The Government of Canada has particular obligations under Article 23 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement to bring its Nunavut-based workforce up to a “representative level” of Inuit. Inuit make up 85% of the Nunavut population; this is the workforce target accepted by the Government of Nunavut.

Inuit face the following unique barriers to employment within the Public Service:

- English is the dominant language for employment. Less value is placed on Inuit languages, including Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, even though these are often the languages used to provide services in Nunavut.

- Inuit have to learn a foreign way of doing things and are faced with situations where less value is placed on traditional knowledge or values (Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit).

- Inuit are sensitive to people from the South—who have different ethnic backgrounds, speak a different language and hold different cultural beliefs—telling them what to do in their own territory. Most decision makers in Nunavut are not Inuit.

- Inuit experience bullying and discrimination in the workplace that lead to poor mental health.

- There is an expectation that Inuit should assimilate to work styles and cultures prevalent in the South.

“They do very little to change themselves to accommodate to you. The basic assumption is one of assimilation, and that it is Inuit who need to change and adapt, not the Government of Canada or its policies”

Government of Canada offices in Nunavut offer an opportunity to take action towards achieving reconciliation and to recognize the value and strengths of Inuit partners. The best practices analysis offers some promising options for using Article 23 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement as an opportunity to experiment with structural change.

The analysis concludes with suggestions to address some of the employment-related barriers facing Inuit. Efforts should be made to:

- Simplify the bureaucratic application process for Nunavut positions wherever possible and find ways to focus on the ability to do the job rather than meet all the qualifications on paper;

- In addition to the existing housing and travel allowances for employees in Nunavut, which recognize the particular circumstances and difficulties they face, provide greater education and training allowances for employees who have not had the opportunities most southern Canadians have had to further their education and training. Work with partners to develop creative solutions to support employees with child care responsibilities; and

- Work with partners to build on the best practices that will be identified by Employment and Social Development Canada’s Nunavut Inuit Labour Force Analysis (NILFA) team in its current research, and to increase accountability, make public all documents pertaining to NILFA and the Government of Canada’s Inuit Employment Plan, performance measures and evaluations.

See Annex 4 for a summary of the literature review on best practices.

4. Highlighting Promising Practices

Building on current practices that support Indigenous employees contributes to establishing an inclusive and diverse workplace.

Departmental Champions for Indigenous employees were asked to complete a short questionnaire on the Indigenous-specific programs and supports in place within their organization. Several departments are moving in the right direction and a few are well on their way to implementing practices that will have a positive effect on the workplace experience of Indigenous employees. The following are examples of noteworthy and promising practices:

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada established and staffed a full-time Elder position in 2016 to support and engage Indigenous employees.

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency hired an Elder and former Public Service executive on a part-time basis to help with outreach and recruitment.

- The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission sponsored 45 summer science camps for children in First Nations communities across the country.

- Since 2012, Shared Services Canada has awarded 1,021 contracts for an approximate value of $125 million to Indigenous businesses.

- National Film Board shared applications from self-identified Indigenous candidates with other departments that would be a good fit for the candidate.

- Health Canada provides an annual budget of approximately $2,500 to the Aboriginal Employee Network.

See Annex 5 for an inventory of noteworthy and promising practices.

5. Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation and Indigenous Representation

A Strategy to Welcome, Respect, Support and Act to fully Include Indigenous Peoples in the Public Service

Indigenous People face real barriers when seeking and living a Public Service career. Strong evidence of these barriers comes from the testimony, input and advice received from Indigenous employees and internal stakeholders; quantitative and qualitative research; and data and survey analysis. Similarly, the Circle’s early recommendations for action were validated and supplemented through employee consultation and engagement, research, data and survey analysis.

This Strategy seeks to influence the culture of the Public Service and the behaviours of individual public servants, to achieve a workplace where Indigenous people seeking and living a Public Service career are welcomed, respected, supported, and fully included in all facets of Public Service life. The Strategy has four primary objectives that are underpinned by actions to support, engage and communicate with Indigenous employees and partners.

The current Public Service culture affords the opportunity to extend existing best practices so that they are more consistently and broadly implemented. Where possible, the Public Service should move to the next level of best practices – involving transformation.

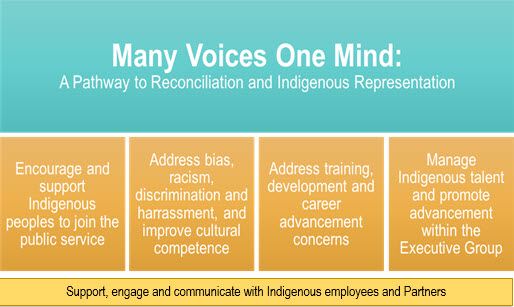

Text version

Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation and Indigenous Representation:

- Encourage and support Indigenous peoples to join the public service.

- Address bias, racism, discrimination and harrassment, and improve cultural competence.

- Address training development and career advancement concerns

- Manage Indigenous talent and promote advancement within the Executive Group.

Support, engage and communicate with Indegenous employees and Partners.

This Strategy challenges public servants at all levels to act to remove barriers that prevent the full inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in the Public Service. The Strategy identifies tools, mechanisms and new processes to nurture a Public Service culture where employee engagement, satisfaction, morale and confidence are improved and where Indigenous Peoples are more likely to regard the Public Service as a workplace of choice.

Strategy Objectives

- Encourage and support Indigenous People to join the Public Service

- Address bias, racism, discrimination and harassment, and improve cultural competence in the Public Service

- Address training, development and career advancement concerns expressed by Indigenous employees

- Manage Indigenous talent and promote advancement to and within the Executive Group

- Support, engage and communicate with Indigenous employees and partners

Outcomes and Actions

Encourage and support Indigenous Peoples to join the Public Service

Outcomes:

- Reduced barriers to Indigenous Peoples’ access to Public Service employment.

- Increased hiring and retention of Indigenous Peoples at entry-level and mid-career to address future Public Service employment needs.

- Improved opportunities for Indigenous employees to network within departments and across government—creating a sense of community.

Actions:

Opportunities to Enhance Current Practices:

- Extend outreach networks used by the staffing managers to include Indigenous communities, Indigenous post-secondary institutions, colleges and polytechnic institutes, and campus-based institutions mandated to provide services and supports to Indigenous students.

- Expand outreach to target Indigenous high school students and where possible encourage them to consider and pursue occupations where the Public Service anticipates future gaps (e.g. science-based occupations).

- Strengthen recruitment processes and approaches by collaborating and partnering with Indigenous institutions to reduce barriers to accessing and applying for Public Service positions (e.g. the need for Internet access to be notified about employment opportunities and/or apply from remote communities).

- Partner with Indigenous organizations and employees to develop targeted COOP and internship opportunities to attract Indigenous students to the full spectrum of Public Service jobs (e.g. trades, administrative support, etc.).

- Include Indigenous public servants on external facing recruitment teams.

- Support, promote, expand, replicate and measure the impacts of innovative current initiatives like iHireAboriginal (INAC), Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity—IYSEO (TBS) and the Elders support program (AAFC).

- Expand IYSEO into the regions.

Opportunities for Immediate Improvements:

- Review practices and tools used by the Personnel Psychology Centre of the Public Service Commission to address systemic and cultural biases in assessment; review their work on customized assessment tools (e.g. those used in hiring Inuit ADMs) so that it can be expanded.

- Review staffing processes across the system to ensure that hiring and interview boards are culturally appropriate and culturally sensitive, and that action is taken to remove barriers to the appointment and promotion of Indigenous Peoples.

- Establish and support interdepartmental Indigenous employee networks as a mechanism for new recruits to connect with other Indigenous employees and access potential mentors.

- Engage and collaborate with Indigenous employees to plan organizational initiatives, including onboarding programs, celebration, and respectful incorporation of Indigenous histories and cultures into the workplace.

Opportunity for Transformational Change:

- Develop a mid-career employment opportunity program to encourage Indigenous Peoples at mid-career to join the Public Service.

Address bias, racism, discrimination and harassment, and improve cultural competence in the Public Service

Outcomes:

- Improved departmental readiness to respectfully welcome and support Indigenous employees at each career transition.

- Integrated and robust cultural awareness components across the suite of programs offered by the Canada School of Public Service.

- Improved employee perceptions and fewer complaints about transparency and fairness in staffing processes, prequalified pools and low rankings of Indigenous Peoples because of “poor fit”.

- Addressing unconscious bias, anti-racism, anti-discrimination and harassment awareness as an integral measure of employee performance.

Actions:

Opportunities to Enhance Current Practices:

- Challenge and incentivize Public Service leaders and managers to develop collaborative and inclusive leadership styles that promote employees’ participation in decision making

- Design, develop and deliver a rigorous, defined, structured approach to implementing Call to Action #57 from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) (PDF format). Training should focus on improving awareness and respect for Indigenous histories, cultures, community realities and life circumstances.

- Inspect current onboarding, leadership, supervisory and management courses to ensure they incorporate Indigenous historical and cultural awareness components throughout.

- Collaborate with Indigenous employees and other stakeholders to deliver priority cultural competence training to staff, supervisors, managers and leaders in departments, agencies and programs who develop policies or run programs that impact Indigenous communities.

- Review recruitment, development and promotion policies and processes through the lenses of diversity and inclusion, and reconciliation, to root out biases that discriminate against IndigenousPeoples.

Opportunities for Immediate Improvements:

- Integrate anti-racism, anti-discrimination, harassment- and bias-free expectations of conduct into competency profiles for all public servants.

- Institute ongoing annual performance expectations for leaders that hold them accountable to address unconscious bias, racism, discrimination and harassment in their organization.

- Partner and collaborate with Indigenous Peoples and other stakeholders to develop a robust suite of courses and other education materials that address unconscious bias, anti-racism, anti-discrimination and harassment awareness among public servants.

- Make unconscious bias, anti-racism, anti-discrimination and harassment awareness training an essential component of Public Service onboarding training.

- Implement an exit interview process that includes questions about employee experiences with bias, racism, discrimination, harassment and cultural insensitivity and where Indigenous employees have the option to complete their exit interview with an Indigenous person who is not directly linked to their work environment.

- Undertake a system-wide review of how “right fit” is assessed and how associated justifications are being applied.

Opportunities for Transformational Change:

- Establish an Ombudsperson for Indigenous Reconciliation to provide a trusted, safe space and whose mandate is to resolve the widest possible range of issues pertaining to bias, racism, discrimination and harassment faced by Indigenous federal employees. The office of the Ombudsperson for Indigenous Reconciliation would provide managers and employees with a confidential environment where informal conversations and conflict resolution improve workplace understanding, support and relationships.

Address training, development and career advancement concerns expressed by Indigenous employees

Outcomes:

- Improved workplace satisfaction and retention of Indigenous public servants as demonstrated through departmental Public Service Employee Survey results.

- Mid-career Indigenous federal employees and new Indigenous recruits are viewed as a new pipeline of Indigenous leaders.

- Demonstrated fairness and transparency in training and development decisions.

- Improved Indigenous representation in the upper executive ranks.

Actions:

Opportunities to Enhance Current Practices:

- Clarify how Indigenous employees can access coaching, mentoring and sponsorship opportunities.

- Offer Indigenous employees deliberate career management to clarify routes to success and promotion and to help them be proactive in their career and skills development.

- Assign departments within a shared portfolio to identify and promote the use of assignments, secondments and cross-training to encourage mobility and development for Indigenous employees.

Opportunities for Immediate Improvements:

- Implement culturally sensitive employee supports across government organizations (e.g. expand the Elders program in place at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada).

- Examine opportunities and programs to increase Indigenous employees’ access to culturally appropriate French language training and support during the language training process.

- Create opportunities for staff to use and be valued for using their Indigenous language in the workplace.

- Identify positions where use of an Indigenous language is recognized and valued as the “second required language of work.”

Opportunities for Transformational Change:

- Compensate Indigenous language users in positions where an Indigenous language use is required or an asset.

- Establish and resource a centralized Center of Expertise for Indigenous Inclusion to provide advice, guidance and support to Public Service managers to effectively integrate Indigenous Peoples into their workplace.

Manage Indigenous talent and promote advancement to and within the Executive Group

Outcomes:

- Diverse senior leadership resulting in better decision-making and better outcomes for people living in Canada.

- Improved employee satisfaction and retention.

- Rejuvenated mid-career Indigenous public servants.

Actions:

Opportunities to Enhance Current Practices:

- Improve communication about management and leadership development opportunities so that Indigenous participants are aware of them and have time to prepare and to apply.

Opportunities for Immediate Improvements:

- Design, develop and implement career counselling opportunities for mid-level Indigenous employees (with 5-10 years of service) to determine their readiness for leadership development.

- Design, develop and implement deliberate and transparent approaches to identifying leadership potential and developing Indigenous managers into leaders.

Opportunities for Transformational Change:

- Assign Deputy Ministers as Champions for Indigenous executives to support their progression through the Executive Group.

- Establish an Indigenous Executive Development Program.

- Establish the requirement for experience working with and/or knowledge of Indigenous communities, histories and cultures for any position that involves providing service to Indigenous communities or impacts Indigenous communities.

Support, engage and communicate with Indigenous employees and partners

Outcomes:

- Improved workplace satisfaction for Indigenous employees.

- Increased awareness of workplace climate.

- Improved Championing of Indigenous employees.

Actions:

Opportunities to Enhance Current Practices:

- Take the “pulse” of Indigenous employees regularly and with greater frequency when relevant (notably during periods of workforce adjustment).

- Explore options for surveying Indigenous employees in line with the survey as a baseline, conducted as a regular check-in to support the Many Voices one Mind Strategy.

- Support the coordination and advancement of an interdepartmental Indigenous employee network that includes a youth-specific component for new recruits and young professionals.

- Support the coordination and advancement of a formal Indigenous Executive Network.

Opportunities for Immediate Improvements:

- Establish an accountability framework for Departmental Champions for Indigenous employees that includes:

- Mandatory diversity and inclusion training

- Mandatory unconscious bias training

- Mandatory training to develop cultural competencies in regard to Indigenous Peoples

- Providing Champions with financial resources to achieve results

Opportunities for Transformational Change:

- Review and realign the current infrastructure that is intended to support and promote equity and diversity in the Public Service so that it focuses more deliberately on effecting culture change within the organization.

6. Implementation and Measuring Progress

Developing the Many Voices One Mind Strategy is a first step toward transforming the Public Service and making it a workplace where Indigenous people seeking and living a Public Service career are welcomed, respected and supported, and where action is taken to see them fully included. The next critical step is to develop a robust, multi-pronged implementation plan with specific timelines and methods to measure progress.

The research, survey, data analysis and reporting completed by Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation as the foundation for the Many Voices One Mind Strategy establishes a clear baseline. Individual departments and the Public Service as a whole can use this foundation to benchmark and plan for improvement.

Deputy Heads are encouraged to work in partnership and to use the flexibilities already available through their delegated authorities to develop change management plans and methods to measure progress suited to their organization.

7. Conclusion

Opportunities for further research and analysis abound and there is great value in continuing the analysis started here. There remains much to uncover about regional differences, the unique needs of various Indigenous populations including, for example, the Métis, and urban compared to on-reserve First Nations. For all that the Interdepartmental Circles learned and shared through the work completed over the last year, there is room for more detailed and stratified analysis.

This report clearly identifies the barriers faced by Indigenous people seeking and living a Public Service career; shares the views and perspectives of Indigenous Peoples on their Public Service work experience; summarizes research into best practices to recruit and retain Indigenous Peoples as members of the Public Service; and presents a whole of government strategy to improve Indigenous representation.

The outcomes and actions outlined in Many Voices One Mind: a Pathway to Reconciliation provide a starting point. Now the work to develop an implementation approach, transform resources and measure progress begins.

Annex 1 - Barriers to indigenous employment

| Labour Market | Recruitment | Onboarding | Retention and Career Management | Exit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Annex 2 - Indigenous workforce retention survey findings

Overview of methodology

Quantitative phase

The research team worked with representatives of the Deputy Champion for Indigenous federal public servants and the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation to conduct outreach to current and former Indigenous employees of their respective departments. Below is an outline of the sample and responses.

| Email status | Sample |

|---|---|

| Total links opened | 3,872 |

| No responses entered | 355 |

| Unfinished/invalid questionnaires | 624 |

| Not qualifying respondents (Self-qualifies as Not-Indigenous) | 704 |

| Completed surveys | 2,189 |

Over three quarters (76%) of the individuals who opened the link after receiving an invitation to participate in the survey qualified to participate based on self-selection criteria, and 56% completed the survey.

Of the completed surveys, a total of 2,138 were from current employees, and 51 from former employees. It is not surprising that the response rate was lower from former employees given the greater challenge of reaching employees who were no longer in the employment of the federal public service.

Qualitative Phase

Dialogue Circles Approach

Two variables were used in the formation of the groups – employment status within the federal public service (current vs. former employees), their current place of work, and their official language preference. Four Dialogue Circles were organized during the week of April 17-21, 2017 and were led by an experienced facilitator and supported by a note taker. The Dialogue Circles comprised the following groups and organized as per the table below:

| Group | Language | Number of participants | Date and Time | Participation | Setting/Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Regional and NCR | English | 11 | April 18, 2017 @ 10:00 am | 9 – in person 2 – by phone |

Non-focus group room in Ottawa, ON |

| Current NCR | English | 12 | April 18, 2017 @ 1:00 pm | 12 – in person | Non-focus group room in Ottawa, ON |

| Current Regional and NCR | French | 8 | April 21, 2017 @ 10:00 am | 1 – in person 7 – by phone |

Non-focus group room in Ottawa, ON |

| Former Regional and NCR | English | 6 | April 21, 2017 @ 1:00 pm | 2 – in person 4 – by phone |

Non-focus group room in Gatineau, QC |

Section I: Analysis and results

Figure 1

Text version

Word Cloud containing the following words:

Nonjudgmental representation enjoyable reconciliation discrimination compassion unbiased teamwork formation calm non-discriminatory patient considerate nonjudgemental empathetic dignity honesty knowledgeable leadership harmonious good recognition accepting valued holistic interested sensitive equality safe caring language elder communication diversity flexible diversité advancement positive inclusivity equitable empathy sincere listen developmental tolerant fair honour équité kind respectful team growth relaxed growth humility helpful network balanced intégrité work trust supportive honest adaptive free aboriginal awareness cultures encouraging openess receptive history equity openness mentoring family know friendly opportunity reconnaissance cooperative patience healthy productive openminded less respectueux professional accessible management ouverture mentorship confiance rewarding compassionate ouvert curious spiritual accountability barrierfree multicultural

Figure 2

Text version

Word Cloud containing the following words:

Nonprejudice work vibrant open empowerment approachable transparency healthy inclusive accountable challenging acceptance engaged equitable value welcoming mentorship informed competent safe fair rewarding equity culturally equal holistic training integrity diversity enjoy flexible inclusive empathetic caring ethics implication respectful qualify harmony fluid balance considerate understanding clear positive genuine advancing supportive friendly growth discrimination history leadership tolerant cooperation knowledge learning mentoring share creating honesty belonging trust openminded appartenance employment partage decolonized mindful indigenous teamwork opportunity

Word Clouds Analysis

The top three words chosen to describe a supportive work environment were, to a great extent, the same between both current and former employee respondents and they included:

- Respectful

- Inclusivity

- Supportive

Additional words that were of shared importance to both current and former Indigenous federal public servants included: “diversity”, “equality”, “fair”, and “flexible”. Both cohorts used these words in high quantity. When the word culture was used, it was often accompanied by “awareness”, “sensitivity”, and “training” which provides insight into what types of training might benefit non-Indigenous federal public servants.

Former federal public servants used “understanding” more than current federal public servants. The words that were used the fewest times by current Indigenous federal public servants included: “autonomie” (autonomy), “availability”, “career”, and “coaching”. The words that were used the fewest times by former federal public servants included: “transparency”, “trust” and “vibrant”.

Survey Findings – Current Indigenous Public Servants

Recruitment

Text version

- Job Security: 44%

- Good benefits: 42%

- Good pay: 31%

- Opportunities for career development/promotion: 27%

- Ability to make a difference for Indigenous people of Canada: 25%

- Doing Challenging/interesting work: 25%

- Ability to use my education: 19%

- Ability to make a difference for Canadians: 16%

- Predictable Work Schedule: 10%

- Learning or acquiring new skills on the job: 9%

- Flexible work arrangements: 8%

- Train/Learning opportunities: 7%

- Ability to work in a diverse work environment: 6%

- Working in an office/ at desk: 4%

- Only available employment opportunity in my area: 4%

- Transportation, travel or moving allowance: 1%

- Access to day care at work or in the community: less than 1%

- Other: 5%

Table 1: Question 1 - Base: All respondents - current public servants; n=2,138.

The majority of current employee respondents selected “Job Security” (44%) and “Good Benefits” (42%) when asked to identify their primary attraction to working in the federal public service while “Transportation, travel, or moving allowance” (1%) and “Access to day care at work or in the community” (<1%) were ranked the lowest.

Text version

- First statement: My first Federal public service job was what I expected

- To the first statement, 5% strongly disagree, 13% disagree, 27% are neutral, 46% agree and 10% strongly agree.

- Second statement: I had a good understanding of how the recruitment process worked and what was expected of me.

- To the second statement, 8% strongly disagree, 19% disagree, 22% are neutral, 39% agree and 12% strongly agree.

- Third statement: I was satisfied with the recruitment process.

- To the third statement: 6% strongly disagree, 14% disagree, 23% are neutral, 43% agree and 13% strongly agree.

Table 2: Question 2 - Base: All respondents - current public servants; n=2,138.

Over half of all the current employee respondents (56%) strongly agree/agree that their “First job in the federal public service was what they expected”, and 18% of respondents strongly disagree/disagree. A total of 51% of respondents indicated they “Understood how the recruitment process worked and what was required of them throughout the process” (strongly agree/agree) and a total of 56% of respondents were satisfied with the overall recruitment process (strongly agree/ agree).

Respondents with 5 years of service or less (56%) were slightly more likely than those with 6 years of service or more (50%) to strongly agree/agree that they “Understood the recruitment process”. This level of agreement is also true for Inuit (64%) and Métis (53%) respondents. First Nations (49%) respondents reported slightly lower levels of understanding of how the recruitment process worked. Respondents from the QC region indicated the highest level of agreement (72% strongly agree/agree).

The QC region indicated the highest levels of satisfaction with the recruitment process (71% strongly agree/agree). Respondents with 10 years of service or less were less satisfied 25% (disagree/strongly disagree) with the recruitment process compared to those with 11 years of service or more (17%).

Text version

- Collaboration with Indigenous institutions to expand: 40%

- More indigenous co-op and internship opportunities: 39%

- Indigenous recruiters: 34%

- Better explanation of what to expect in the recruitment: 30%

- Increase external posting: 29%

- Shorter application process: 27%

- Provide personalized support to Indigenous applicants: 23%

- Cultural considerations in the assessment of interview: 19%

- Less paperwork: 10%

- More culturally relevant interview question: 10%

- Greater use of social media usage (e.g. Linked-in, Twitter…): 8%

- Other: 11%

Table 3: Question 3 - Base: All respondents - current public servants; n=2,138.

A majority of respondents identified the following as being the most important ways of improving the recruitment process: “Collaboration with Indigenous institutions to expand recruitment of Indigenous employees” (40%), “More Indigenous co-op and internship opportunities” (39%), and “Indigenous recruiters” (34%). The selection of “Better explanation of the recruitment process” (30%) reaffirms findings that more support is needed to navigate the federal public service recruitment process. Of the 11% who indicated “Other” three main themes emerged:

- Fair assessment including reducing stereotypes and racism and building trust

- i.e., cultural considerations in marking rubric; PSC tests; and interview questions.

- Assessment should be based on merit rather than affirmative action policies

- i.e., targeted recruitment number would make me feel like I was being singled out; that the only reason they received the job was because they are Indigenous; disagree with targeted quota hiring; everyone should be treated equally/fairly.

- Reduce accessibility barriers in the application and interview process to potential Indigenous recruits

- i.e., poor Internet connectivity; remoteness and lack of awareness in communities; increase ability to work in community; workshops led by Indigenous recruiters / bridging programs; Indigenous recruitment office / ombudsman; offer interview in Indigenous languages and value Indigenous languages; reduce requirements for fluency in the French language; increase non-competitive hiring postings; streamlined/shorter/more clear application processes.

Learning and Development

Text version

- Leadership development: 1% said unimportant, 3% said somewhat unimportant, 24% said somewhat important, 72% said important.

- Better understanding of my development needs: 1% said unimportant, 4% said somewhat unimportant, 30% said somewhat important and 65% said important.

- Better understanding of competencies required to become a leader: 2% said unimportant, 4% said somewhat important, 35% said somewhat important and 59% said important.

- Cultural competency training: 3% said unimportant, 8% said somewhat unimportant, 32% said somewhat important and 57% said important.

- Understanding how government operates: 2% said unimportant, 8% said somewhat unimportant, 39% said somewhat important and 51% said important.

- Language training: 10% said unimportant, 12% said somewhat unimportant, 35% said somewhat important and 43% said important.

- Financial management: 3% said unimportant, 10% said somewhat unimportant, 45% said somewhat important and 42% said important.

- Other: 16% said unimportant, 3% said somewhat unimportant, 11% said somewhat important and 55% said important.

Table 4: Question 12 - Base: All respondents - current public servants; n=2,138.

Current employee respondents were asked to rate the importance of various areas of learning and development. Those areas ranked as important include:

- Leadership development (72%)

- Better understanding of my development needs (65%)

- Better understanding of competencies to become a leader as being (59%)

For those who indicated “Other”, the issue of language requirements was emphasized. Respondents made suggestions, such as Indigenous language training as well as reducing French language requirements. Respondents also emphasized the importance of supporting health and wellness and cultural awareness and training for all staff, including all levels of management and executive positions.

Analysis of Differences: Important Areas of Learning and Development

“Leadership development” was less often identified as an “Important” area by QC (59%), MB (69%) and NCR (69%) compared to other regions.

Women more frequently identified “Better understanding of [their] development needs” as important (70%) when compared to men (56%).

“Better understanding of competencies required to become a leader” was identified as “Important” most often by AB (69%), SK (66%) and ATL (62%) compared to other regions.

“Cultural competency training” was identified as “Important” considerably more often in all regions (60%) except the QC region (39%), as well as amongst First Nations (63%) respondents compared to Métis (49%) and Inuit (52%) respondents.

“Financial management” was most often identified as “Important” by the NU/NWT/YK regions (58%) compared to other regions.

Finally, “Language training” was identified as an important area of learning and development by the NCR (62%) and QC regions (51%) compared to other regions, and Inuit respondents (57%) compared to other Métis (41%) and First Nations (44%) respondents.

Text version

- 52% responded yes

- 37 responded no

- 11% responded don’t know.

Table 5: Question 13 - Base: All respondents - current public servants; n=2,138.

A little over half (52%) of the respondents identified that they had access to the type of learning and development opportunities that they identified as important or somewhat important in the preceding section.

Text version

- Budget constraints mean access is limited: 67%

- Work pressures mean there is no time for learning & development: 66%

- Don’t feel there is equal access to learning & development opportunities: 42%

- As far as I know, it is not available: 17%

- Working in a remote location means travel costs to learning & development are prohibitive: 14%

- My supervisor does not support learning and development: 11%

- Other: 20%

Table 6: Question 14 - Base: All respondents - current public servants; n=2,138.

When current employee respondents were asked to select the top three main challenges that they faced when trying to access learning and development opportunities, “Budget Constraints”, “Work Pressures” and “I don’t feel there is equal access” came out as the predominant top three challenges. The 20% of respondents who selected “other” indicated reasons such as:

- Accessibility i.e. training not seen as a priority for casual employees; less opportunities in regions /smaller cities; limited opportunities in general; only available to managers/executives

- There is limited support from leadership / lack of recognition of non-GoC courses

- Training doesn’t meet needs, or is too general

- Time consuming / feel overwhelmed knowing where to access opportunities i.e. online paperwork; searching for opportunities; prioritize family time

- Dislike online learning or limited computer access

- No challenges i.e. due to supportive management

Workplace Challenges

Text version

- Lack of career advancement opportunities: 36%

- I feel stuck in my current job/ Limited for opportunities for mobility: 26%

- Vacancies requires coverage of the responsibilities of 2 positions: 23%

- Lack of coaching and mentoring: 20%

- Lack of respect for Indigenous culture & values: 18%

- Too many rules and procedures: 17%

- Feelings of discrimination: 17%

- Language skills requirements too high: 13%

- Lack of supervisory support: 12%

- Lack of flexible work arrangements: 8%