Good Label and Package Practices Guide for Prescription Drugs

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.34 MB, 79 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: 2019-06-21

Preamble

The utmost care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information presented in this guide. The guide reflects the information available during its development and is meant to provide initial considerations when preparing the content and design of labels and packages. It is anticipated that new research on various topics addressed in this guide will become available in the future, and revisions may be warranted to integrate such new information.

This document should be read in conjunction with the relevant sections of other applicable Health Canada regulations, guidance documents, and policies.

Organization of the Guide

The guide is divided into three parts:

Part 1 presents the objective, introduction, and scope. It also provides an overview of the process used in developing the guide.

Part 2 highlights the importance of the user's perspective. It emphasizes the need to consider the environment in which health products are selected and used. This is intended to provide a reference point for all other sections of the guide.

Part 3 addresses the specific components applicable to the design of labels and packages from a safety perspective. The section for each component presents background information followed by recommendations.

The appendices contain supplementary information to the guide as follows:

Appendix 1: Glossary

Appendix 2: Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging

Appendix 3: Product-Use Process Maps

Appendix 4: Acknowledgements

All parts of the guide and its sections should be considered together, i.e., no topic is to be considered in isolation.

Table of contents

- 1 Overview of the Guide

- 2 Considering Users and Their Environments

- 3 Designing Labels and Packages for Safety

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 Planning the design of labels and packages

- 3.3 Design and layout

- 3.3.1 Type style and size

- 3.3.2 TALLman lettering

- 3.3.3 Proximity and compatibility of information on the principal display panel

- 3.3.4 White space

- 3.3.5 Colour and contrast

- 3.3.6 Use of abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations

- 3.3.7 Bilingual labelling

- 3.3.8 Logo, branding, and trade dress

- 3.3.9 Permanence

- 3.4 Label information

- 3.5 Packaging

- Appendix 1 - Glossary

- Appendix 2 - Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging

- Appendix 3 - Product-Use Process Maps

- Appendix 4 - Acknowledgements

- References

1 Overview of the Guide

1.1 Objective

The objective of the Good Label and Package Practices Guide for Prescription Drugs is to provide direction to sponsors, manufacturers and license holders (to be referred to as 'sponsors' within this guide) in designing safe and clear labels and packages.

It is essential that all labelling and packaging regulatory requirements be met.

The recommendations provided in this guide will aid sponsors in the organization of (a) information required by the regulations, and (b) other complementary information important to the proper identification, selection, and use of the product. The information is presented to support the design and development of labels and packages that are clear, effective, and minimize the risk of errors causing harm.

1.2 Introduction

The label and package are the first points of interaction between a health product and a healthcare professional or patient. They communicate key information about the safe and proper use of health products, and are important aids in product identification, selection and administration. The ability to perform product identification, selection and administration safely is dependent on the user being able to read and understand the information on the label.

Through the Plain Language Labelling Initiative, new Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Labelling, Packaging and Brand Names of Drugs for Human Use)Footnote 1 have been introduced with the intention of improving the safe use of drugs by making drug labels easier to read and understand. These amendments include a requirement for the addition of contact information on the label and the submission of label and package mock-ups. The content presented in this guide will provide information that supports the objectives of the Plain Language Labelling Initiative.

1.3 Scope

This guide focuses on the inner and outer labels and packages across the following health products for human use:

- prescription pharmaceuticals;

- biologics and radiopharmaceuticals; and

- drugs that are permitted to be sold without a prescription but that are obtained or administered only under the direction of a healthcare professional (e.g., nitroglycerin, insulin, injectable epinephrine for anti-allergic purposes).

Any of these may be referred to as a "product" or "health product" in the context of this guide.

This guide is not applicable to whole blood and its components under the Blood RegulationsFootnote 2; cells, tissues and organs under the Safety of Human Cells, Tissues and Organs for Transplantation RegulationsFootnote 3; consumer health products for self-selection; disinfectant drugs; drug products used in clinical trials; active pharmaceutical ingredients; and drug products for veterinary use.

The guide complements Health Canada's Guidance Document: Labelling of Pharmaceutical Drugs for Human UseFootnote 4 and complies with the Food and Drugs Act, Food and Drug RegulationsFootnote 5.

Aspects of product labelling that are not covered include the naming of health products (refer to Guidance Document for Industry - Review of Drug Brand NamesFootnote 6), user-applied labels, product monographs, package inserts (e.g., prescribing information), and Patient Medication Information.

1.4 Content contributing to guide development

A large volume of information has been published providing direction to optimize the design and content of health product labels and packages to support safe use. This body of knowledge, along with additional research and consultation on the topic, has been reviewed and adapted to produce this guide and is inclusive of the following:

- Applicable Canadian regulations, standards, policies, and guidelines

- Health Canada risk communications applicable to inner and outer labels and packages

- Package and label changes and relevant learning from published reports of safety incidents with labels and packages identified as a contributing factor

- Aggregate analysis of error reports voluntarily submitted to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada in which sponsor's labels or packages were explicitly identified as a concern or a contributing factorFootnote 7Footnote 8

- Consideration of human factors issues and principles (refer to Appendix 2, "Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging")

- Applicable international regulations, standards, policies, and guidelines

- Concepts applied to labelling and packaging of health products by safety organizations (e.g., the United Kingdom's National Patient Safety Agency - now part of the National Health Service)

- Engagement of an international, multidisciplinary expert advisory panel and other relevant stakeholders and experts (refer to Appendix 4, "Acknowledgements")

2 Considering Users and Their Environments

The design of a health product should meet the user's needs within the environment of use, rather than there being an expectation that the user or the environment of use will change to fit the intended use of the health product.Footnote 9 Design the glove to fit the hand, instead of expecting the hand to fit a particular glove.

The environment of use can influence how users interact with a health product, so consideration of the environment should be incorporated into the design and evaluation of health product labels and packages.Footnote 9 From a prescription drug perspective, the environment of use can include where the product will be used (e.g., hospitals, long-term care facilities, healthcare professionals' offices, emergency transport settings), where the product will be stored, types of supporting tools and technologies (e.g., dose organizers and dispensers, medication administration records, bar-coding technology), and lighting level.

It is important that product labels and packages be designed with the user in mind and with consideration of the environment and processes in which the product will be used (stocked, selected, and administered). A recent aggregate analysis of labelling and packaging incidents involving health products offered an overview of some of the issues that users of health products have experienced.Footnote 8 The following are some of the potential contributing factors identified in that analysis:

- look-alike labelling and packaging

- prominence of trade dress and brand name

- lack of prominence of proper or common (non-proprietary) name

- lack of prominence (and lack of clarity) of expression of strength

- legibility and readability of information (e.g., type size, contrast of print against background)

- confusing layout of label

- lack of coordination between display of information and perforations on blister packs

- use of dangerous or misleading abbreviations

3 Designing Labels and Packages for Safety

3.1 Introduction

Part 3 of this guide presents information on current good practices in the design and layout of a health product label, the information contained on the label, and the design or choice of package. The topics and principles cover various contributing factors in reported medication incidents and issues identified by environmental scans of sponsors and users.

Although the various topics are presented separately within Part 3, they must be considered together to achieve a balance between standardization and differentiation (e.g., within a sponsor's product line). Standardization of product labels and choice of packages can reduce errors by reinforcing the pattern recognition on which humans rely when processing information.Footnote 10 However, the more label or package characteristics that products have in common (e.g., type style, size and colour of type, size and shape of container or package, layout of information), the more likely that products will look alike. The cumulative effect of individual label and package characteristics can result in look-alike issues that make it difficult for users to distinguish one product from another. The potential for look-alike issues should be considered during the design phase of a product's labelling and packaging. Similarly, changes to existing product labels and packages should strike a balance to prevent introduction of new look-alike issues. Achieving a balance between standardization and differentiation is particularly important to prevent (or resolve) look-alike issues that involve high-alert medications or a sponsor's higher-risk products.

In addition to all the topics discussed in the guide, sponsors are strongly encouraged to consider human factors aspects of product selection, use, and handling, as well as user testing with a risk- based approach (refer to Appendix 2, "Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging"), in the design of labels and packages.

3.2 Planning the design of labels and packages

When designing product labels and packages, sponsors are strongly encouraged to undertake a number of steps. The following is an overview of the steps that sponsors can incorporate into existing product development and marketing processes:

- Consider the design of health product labelling and packaging as early as possible in the development process.

- Development of the package should begin early. Factors influencing the choice of a package should go beyond maintenance of stability, ease of manufacturing, or marketing considerations. The package design will also affect the size of both inner and outer labels.

- For products gaining approval in Canada, the sponsor may already have experience in other markets. Carefully review complaint and incident data to determine if changes are needed for the planned label or package of the health product for the Canadian market.

- Identify the users of the product and their environments of use.

- Designing a label and package for safe use requires keeping the users and the environments of use at top of mind throughout product development.

- At a minimum, review the questions in Appendix 2, "Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging", to identify the users and environments of use. These questions are intended to elicit a wide range of considerations, and their answers can provide opportunities to understand factors important to safe design.

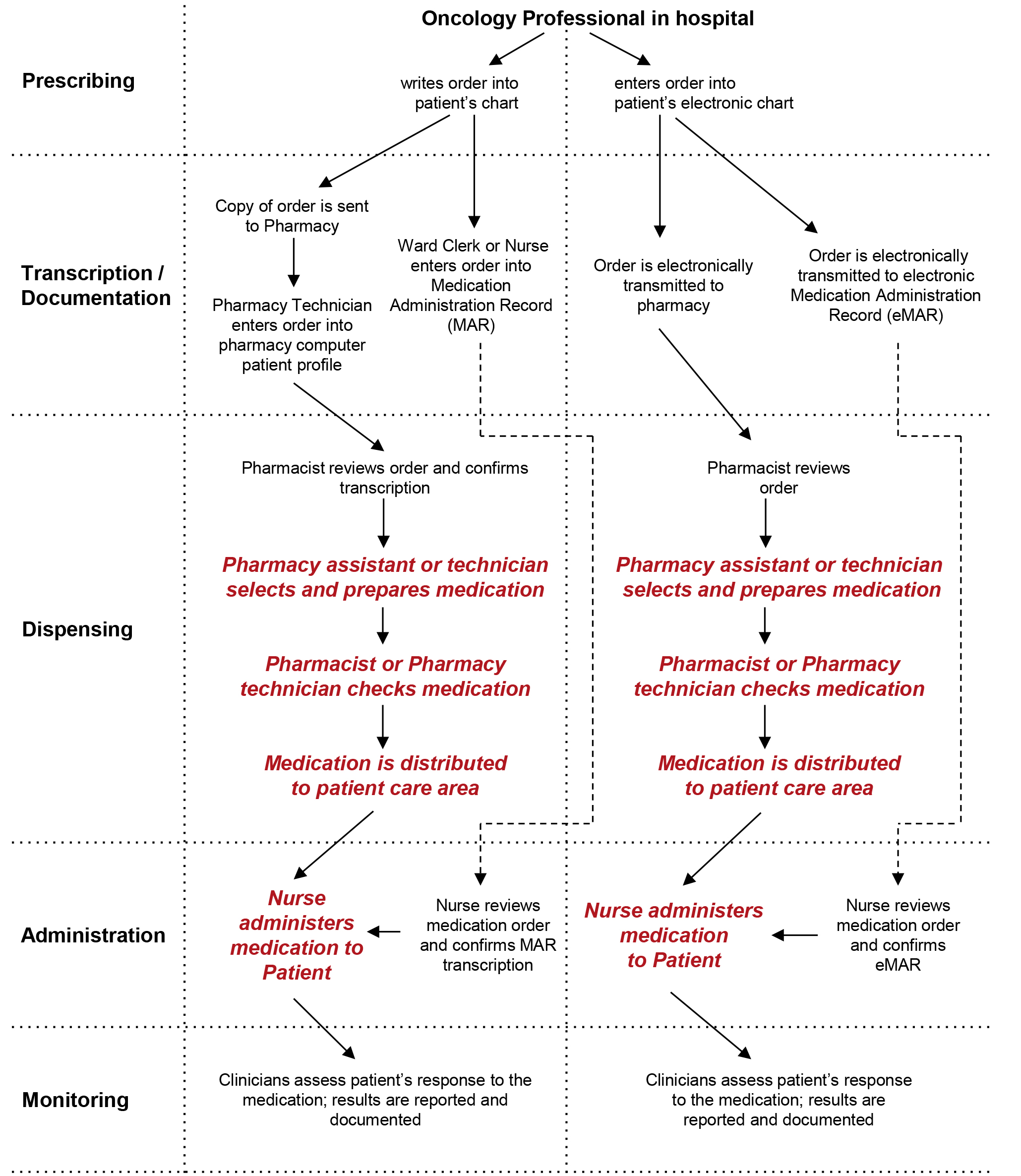

- Product-use process maps can be helpful when human factors-based user testing is planned, in that such maps will help in identifying the scope of use and the primary users. (Refer to Appendix 3, "Product-Use Process Maps" for an example.)

- Consider other products that might be used simultaneously with the product of interest, as products are rarely used in isolation.

- Consider user testing. A variety of user testing and other methods have been applied to the design and redesign of labels. (Refer to Appendix 2, "Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging".)

- Prepare mock-ups of the label and package, including the outer packaging. Mock-ups can have multiple uses (e.g., user testing, focus groups).

- Use a continuous improvement approach. Review complaint and incident data to identify challenges and unanticipated label or package problems early in the design process and following marketing. Manufacturers should monitor trends and implement risk-mitigation measures to improve labels and packages. Gathering information throughout the product life-cycle is a proactive approach and can assist with package and label design.

3.3 Design and layout

3.3.1 Type style and size

Background

Illegibility of printed information is a contributing factor in health product errors.Footnote 8Footnote 11 Interactions between or changes to typographic elements on a label (e.g., type style, size, spacing, use of bold or italic, colour, contrast) can affect both legibility and comprehension.Footnote 12 Label information must be legible to users in the real-world environments or situations in which products will be used.

Recommendations

The following recommendations do not apply to trademarks, copyrighted text, and logos.

Type Style (Typeface)

- When choosing a type style, consider that different styles of the same point size do not appear the same in size.Footnote 12

(insert image fig1-eng.jpg)

Figure 1 - Text description

This image shows the name of the font in the size specified; the fonts are Calibri 9 point, Arial 9 point, Arial Black 9 point, Univers 9 point, and Verdana 9 point.

- Use of a sans serif type style (e.g., Univers, Helvetica), that is not compressed, expanded, or decorative is preferred for key information.Footnote 13 A sans serif type style has no decorative extensions, is crisper and cleaner, and typically appears larger than a serif style of the same point size.Footnote 14 Compressed or condensed fonts may be more difficult to read, even with a larger point size.Footnote 12

- Choose a type style with adequate spacing between letters (to enhance legibility) and between words (to enhance readability).Footnote 12 Narrow letter and word spacing can cause apparent merging of words, whereas extremely wide spacing can be disruptive to the reader.Footnote 12 Adequate spacing can also reduce possible illegibility if ink were to bleed.

- Avoid using all capital lettersFootnote 12 Footnote 13 Footnote 15 Footnote 16 (exceptions: brand names, headings, and warnings that are brief may be fully capitalized). (Refer to section 3.4.3, "Critical Warnings".) The use of all capital letters reduces legibility and adversely affects readability to a greater extent than any other factor. Lowercase characters have more variation (e.g., letter shapes) in their features, which results in better legibility.Footnote 12

- Avoid the use of italic type except to emphasize a particular portion of text.Footnote 12

Type Size

- Use a type size that can be read easily by a variety of users (e.g., elderly people, those with visual impairment) in environments where products will be used (e.g., in a hospital room with low lighting). The following examples show one type style in various point sizes to illustrate that small changes in point size can affect readability:

Figure 2 - Text description

This image shows the phrase "this is Verdana 4.5 point" using Verdana font at an actual 4.5 point size; there are 5 other phrases showing different type sizes of Verdana font: 6 point, 8 point, 9 point, 10 point and 12 point.

- The largest type size possible is recommended. However, a point size less than 6 should not be used for key information.Footnote 13 Footnote 17 Key information includes the key elements (refer to section 3.4.1, "Key Elements on the Principal Display Panel") and label information required by regulations.

- For very small prescription products, such as ampoules and vials of 2 mL or less, the type should be at least 1.5 mm high.Footnote 15

- To enhance legibility when using smaller type sizes (e.g., on small containers), consider using a background colour that is significantly different from the type colour.Footnote 12 (Refer to section 3.3.5, "Colour and Contrast" for further information.)

- Type of very small size may be made more easily readable in combination with other characteristics, e.g., font, colour, white space, bolding, etc.

- The Food and Drug Regulations require that the type of the proper or common name be, at a minimum, half the size used for the brand name.Footnote 18

General Formatting

- To enhance readability, use flush left, ragged right alignment of multiple lines of text (as in this document). This form of alignment provides visual points of reference that guide the reader's eye smoothly from line to line. Since each line is either shorter or longer than the next, the eye is cued from one to the next.Footnote 12

- To enhance the readability of information, use bullet lists, with items in point form instead of complete sentences, if possible.Footnote 13

- When providing stepwise directions, use numbered lists and keep all text for each individual step on one line, if possible. This makes it easier for users to follow the instructions and enables them to find their place again if interrupted.Footnote 13

- Use contrasting characteristics (e.g., type size, weight, bolding, colour, and spacing) to help users distinguish one product from another, and to highlight important information (e.g., warnings in the directions for use) to facilitate safe use of the product, and enable the user to quickly find the information needed.Footnote 13 For example, if it is necessary to present information in paragraph form, use of bold type for key words or phrases or use of subheadings can make it easier and quicker for users to find the information they need.Footnote 13 The following example shows how bold type or subheadings might be used on a product label:

Usual Adult Dose: 75 mg (1 tablet) once daily.

Product monograph available upon request. Store tablets between 15o and 30o C. Protect from moisture.

Pharmacist: Dispense with enclosed Patient Information leaflet. - Consider the information provided in the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) standard Labelling of Drug Ampoules, Vials and Prefilled Syringes,Footnote 15 which may be helpful for selecting aspects such as type style (including character width and height), stroke ratios, and spacing between characters, words, and lines.

3.3.2 TALLman lettering

Background

TALLman lettering is a method used to assist in the differentiation of look-alike, sound-alike non-proprietary (proper or common) drug names through the application of UPPER CASE lettering to certain syllables or groups of letters within names.Footnote 9Footnote 19 TALLman lettering has typically been applied to drug names to bring attention to the points of dissimilarity between confusable names.Footnote 19 TALLman lettering may be effective because it draws attention to drug names presented in this format and can act as a warning.Footnote 20 Overuse of the technique may reduce its effectiveness as names may no longer appear novel.Footnote 21

TALLman lettering is only one of many risk mitigation strategies that can be implemented to minimize errors between confusable product names. This technique does not rely on type style, point size, or colour and can be accommodated in electronic systems; for these reasons, it has become a widely accepted method of distinguishing among drug names within healthcare practice settings.Footnote 22

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada),Footnote 23 the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (US),Footnote 24 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),Footnote 9Footnote 24 and various other organizations around the world have supported the application of TALLman lettering for potentially confusable drug names. Footnote 22 Footnote 25-30

Recommendations

- Use TALLman lettering on product labels only if it is intended as a risk mitigation strategy for an identified safety concern, i.e., if there is an identified risk of confusion between two or more drug names with potential for serious consequences.

- Use TALLman lettering as a safety strategy, not a marketing strategy.

- To ensure that the effectiveness of TALLman lettering is not diluted and that it has the greatest possible impact, limit its use to those names associated with the potential for high risk to patient safety. These names should be identified through a risk assessment process.Footnote 29 Footnote 30

- The potential root causes for drug name confusion should be understood before TALLman lettering is considered as a potential solution. If the confusion arises from look-alike labelling or packaging, alternative differentiation strategies should be applied.

- Ensure that TALLman lettering is consistent with the ISMP Canada list of TALLman Lettering for Look-Alike/Sound-Alike Drug Names in Canada.Footnote 23

- If used, TALLman lettering should be applied only within the non-proprietary name or within the non-proprietary portion of the brand name on product labels.

- Whenever TALLman lettering is used, apply it to both the inner and outer labels, for consistency.

3.3.3 Proximity and compatibility of information on the principal display panel

Background

The Proximity Compatibility Principle specifies that all information relevant to a common task or mental operation should be displayed close together.Footnote 31Footnote 32 For example, the name, strength and dosage form are distinct but closely related elements used to identify and administer a health product and would be placed in close proximity on a product label. Conversely, the net quantity in the package is not related to this information or needed to identify and administer the product and would therefore be placed in a separate location. Confusion errors have been reported when the product strength (a numeric value) and the unit or pack size (another numeric value) were placed in close proximity.

Proximity and compatibility can be affected by other label and type attributes, such as colour, type style, and type size and weight. Use of the same colour(s), type style, point size, and markings or graphics can inadvertently link pieces of information (e.g., numeric values) even when there is physical distance between them on the label.

Recommendations

- Place items that are relevant to a common task or mental operation (e.g., health product name, strength, dosage form, route of administration) close to one another on a product label.Footnote 32Footnote 33

- Consider how the various elements of the label are presented as a whole. In addition to grouping closely related information together on the principal display panel, consider how the colour, type style, and type size and weight visually separate or connect different pieces of information. For example, if the number of tablets in a package (unit pack size) is presented in the same colour as the product strength, but has a more prominent appearance (e.g., in bold type or larger type size); the number of tablets may be misinterpreted as the strength or dose.

- When listing more than one strength on a single panel, ensure that the strength per unit is placed in close proximity to the strength per total volume.Footnote 16Footnote 33 When the total quantity per total volume is present on the principal display panel, ensure that this information is more prominent than any other expression of strength.Footnote 26Footnote 34

- List the net quantity in the package separately from, and less prominently than, the product strength. Displaying this information together (e.g., 10 mg / 7 tablets) has been a contributing factor in medication errors.Footnote 8 The number of units can remain on the principal display panel but should be separated either physically or through design features so to reduce the chance for it to be misread as the product strength.

- Avoid separating unrelated information with marks that could be misinterpreted. For example, if a point or a dash is positioned between the dose and the total volume in the container, the volume might be misinterpreted as part of the dose (e.g., "1000 units · 25 mL", where "25 mL" refers to the total volume in the container, not the strength per total volume, and might be interpreted as "1000 units per 25 mL").

- When possible, avoid placing unrelated information (including graphics) between the product name and its strength.Footnote 9Footnote 26

- To ensure that key information is legible and not subject to misinterpretation, avoid superimposing text and images (or logos).Footnote 35

- List the standard of manufacture, as applicable (e.g., United States Pharmacopeia [USP], British Pharmacopoeia [BP]), in close proximity to a product's proper name.Footnote 4

3.3.4 White space

Background

White space is an important aspect of design and requires careful consideration during the design phase. It should be used as liberally as possible to enhance the readability of health product labels,Footnote 36 so that healthcare professionals and patients can quickly find the information they need to facilitate safe product use.Footnote 13

The term "white space" does not necessarily refer to space on a label that appears white. Depending on the background colour, it may be more accurate to use another term, such as "blank space". Such white space on a health product label or package refers to any space not covered by print, markings, coloured graphics, watermarks, or other elements of the label.

White space surrounding text can create a feeling of openness.Footnote 37 It can also help readers to focus on what they are reading.Footnote 14 Importantly, it may improve readers' willingness to read and their ability to find and process the information presented, because it helps to reduce the concentration and mental workload required. Footnote 37 Footnote 38

Recommendations

- Incorporate white space as part of the design and layout of information on health product labels as early as possible in the design process. White space should be used for the following purposes:

- to frame a particular grouping of text (e.g., bulleted lists) and to separate unrelated information

- to separate one sentence from another

- to separate paragraphs (to help distinguish one idea from another)

- around headings and key information (e.g., warnings) to emphasize their importance

- Maximize the use of white space to avoid crowding information on the label when smaller type size is used. Increasing the space between lines may be especially helpful for elderly users.Footnote 14

- Avoid using a condensed type style, which reduces white space between letters and words and which can reduce legibility by causing words to merge together visually.Footnote 12

- For the labelling of drug ampoules, vials, and prefilled syringes, particularly for spacing between characters, words, and lines, refer to the CSA standard, Labelling of Drug Ampoules, Vials, and Prefilled Syringes.Footnote 15

3.3.5 Colour and contrast

Background

Colour on the inner and outer labels of health products must be carefully applied to help, and not hinder, the selection of appropriate products by users. The application of colour is just one of many factors to be taken into account in the design of health product labels and should not be considered in isolation.

People with normal colour vision are able to detect differences between similar colours only when the colours are placed side by side. Without side-by-side comparison, similar colours cannot be easily distinguished, and errors can be made if colour is the only variable used on a health product label. For example, problems may arise if different strengths of the same product are differentiated by using variations of one specific colour.Footnote 12

In addition, under less-than-optimal conditions, the ability to discern colours can be further reduced, for example, when print appears on small containers or labels, when viewing time is short (e.g., urgent situations, distractions), when a lower level of lighting is used (e.g., in a patient's hospital room at nightFootnote 39), and when colours of similar products are physically separated (i.e., not viewed together).Footnote 40

The effect of colour in label design can be affected by colour-blindness.Footnote 41-44 Certain types of colour-blindness are more common than others. Colour-blind users may have limitations in their perception of specific coloursFootnote 35Footnote 39 (e.g., red-green) or may have difficulty in reading text in particular colour combinations or on particular colour backgroundsFootnote 40.

Contrast

Contrast is a fundamental design principle that is used to help the user detect differences in what is seen.Footnote 45 It is an important factor for the readability of text, particularly on packages with a coloured background.Footnote 1Footnote 9Footnote 10 Footnote 16 Footnote 33 Footnote 35 Footnote 42-44 Footnote 46-49 For example, it has been recommended that text of a dark colour be used on pale backgrounds to ensure sufficient contrast for optimum visibility.Footnote 9 Footnote 10 Footnote 15 Footnote 16 Footnote 35 Footnote 48 Footnote 50

Colour Differentiation and Colour-Coding

Colour differentiation is generally used to highlight particular features on a product label or to help distinguish one product from another.Footnote 10Footnote 34 However, repeated use of this particular technique can lead to look-alike product labels,Footnote 10Footnote 35Footnote 46Footnote 50 which can in turn predispose users to confirmation bias (i.e., users see what they expect to see). Colour differentiation can also reduce the prominence of key information if it is not used skilfully.Footnote 15Footnote 46

"Color coding is the systematic application of color to aid in classification and identification. A color-coding system enables users to associate a color with a function."Footnote 10 Colour-coding relates to the use of consistent colours for specific products or product strengths by all manufacturers. For various reasons, many safety experts do not support the use of colour-coding:Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 16Footnote 35Footnote 42Footnote 51Footnote 52

- the lack of supporting evidence that it is an effective means to prevent errors,Footnote 16Footnote 51

- the known problems that have resulted from colour-coding,Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 51Footnote 52

- the inherent limitations of selecting identifiable colours,Footnote 35Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 51-53 and

- the limitations of human memory.Footnote 10Footnote 39Footnote 51

Colour-coding appears to have some benefits for user-applied labels and in specific practice areas, such as by anesthesiologists in the operating room setting,Footnote 54 but these benefits are not necessarily applicable to other users or other environments. Users should not be expected to remember and attribute meaning to particular colours, especially given the large number of different product strengths and concentrations, the thousands of drug classes and products, and the limited number of visually distinct colours.

By convention, some colours are typically recognized as conveying certain meanings (e.g., red may convey danger, orange may convey a warning, yellow may convey the need for caution).Footnote 40 Such conventions are commonly used for signage in dangerous or hazard-prone environments, e.g., for traffic signs or for containers holding hazardous chemicals.Footnote 55 Aside from these examples, subjective meanings for colour may also exist in specific populations of users.Footnote 56

Recommendations

Use of Colour

- The application of colour is just one of many factors to be taken into account in the design of health product labels and should not be considered in isolation.

- Consider the users' environments, because a given colour may appear different under different lighting conditions.Footnote 9Footnote 35Footnote 39Footnote 42Footnote 43

- Colour choices should take into account the following general principles:

- Hue: Colours opposite each other on the colour wheel (e.g., blue and orange, yellow and violet) are considered to have more contrast than colours closer together on the wheel (e.g., violet and blue, orange and red) and therefore provide greater differentiation in hue.Footnote 53Footnote 57-59

- Saturation: Fully saturated (bright) colours combined with low-saturation (dull) colours provide greater contrast than combinations of colours of a similar saturation level.Footnote 57

- Value: Colours with a low value (dark colours) placed beside or against colours of a high value (light colours) have greater contrast than colours with similar values.Footnote 53

- Use colour for the following purposes:

- to draw attention to important label information,Footnote 10 such as the name of a health product and its strengthFootnote 33

- to bring attention to or enhance the prominence of warning statementsFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 59

- to differentiate one product from anotherFootnote 42 or to differentiate between strengths within a product lineFootnote 42Footnote 46Footnote 51Footnote 60

- While trade dress and logos can assist in the selection process, care must be taken to appropriately differentiate products within a product line to decrease the potential for confusion.Footnote 8

- To enhance differentiation among product strengths, use a colour with a different hue, rather than a different intensity or value of the same colour.Footnote 16 For example, avoid using different shades of blue for various strengths, and instead use distinctly different colours.

- As a general principle, colour-coding of health products is not recommended.Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 16Footnote 35Footnote 42Footnote 51Footnote 52

- Consider using more than just colour to distinguish between products.Footnote 9 Other techniques for differentiation include colour bands, frames or key lines (i.e., boxes around text).Footnote 33

- When selecting colours for labelling and packaging, consider the potential implications of colour-blindness (e.g., avoid using both red and green together,Footnote 41 because they may not be easily distinguished by those with red-green colour-blindness). Computer simulation programs, such as Vischeck,Footnote 61 may be used to determine how colours will be perceived by individuals with different forms of colour-blindness.

- Match the styles of inner and outer package labels so that the visual appearance, including use of colour, is identical or related.Footnote 35Footnote 46This approach can help to ensure that users (re)place an inner container into the correct outer package as needed. It can also help users to identify the corresponding outer (secondary) packaging when they need information that may be available only on that outer package (e.g., directions related to a health product in a small-volume container). Such matching between a container label and its outer package or box label reduces the amount of information that needs to be processed simultaneously by the user.Footnote 62

Contrast

- Maximize the legibility of text by ensuring good contrast between text and backgroundFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 33Footnote 43Footnote 46Footnote 63 (e.g., apply dark text on a pale backgroundFootnote 16Footnote 42Footnote 48Footnote 49). Avoid the use of type and background colour combinations that are known to be very difficult to read (e.g., black or yellow type on a red backgroundFootnote 48).

- Use opaque labels on clear or translucent containers to ensure that type is legible and does not show through the container.Footnote 35 Ensure that sufficient clear area remains after application of the label to allow the user to view the contents of the container.Footnote 35

- If a paper label is not an option, use contrasting type ink on an opaque background on the translucent container to maintain readability.Footnote 35

- Engraving (i.e., embossing and debossing) of type onto a container may not provide sufficient contrast on its own; therefore, if such methods are used, highlight the type with ink.Footnote 16

- Ensure that any symbols required by regulations have sufficient contrast against the background colour.Footnote 18

Containers

- Graduation scales on prefilled syringes (i.e., "ready-to-use" clear containers) or oral dosing devices (e.g., oral syringes) should be easily legible. For example, use black ink on a white field of view.Footnote 15

- For blister packs, use a non-reflective material for the backing, so that information is legible.Footnote 9Footnote 26Footnote 46

- For liquids in clear containers, affix labels with colourless glues to prevent misperception of container contents as being discoloured.Footnote 15

3.3.6 Use of abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations

Background

The use of certain abbreviations (e.g., OD), symbols (e.g., μ), and dose designations (e.g., 1.0 mg) to convey health product-related information has been identified as an underlying cause of serious, even fatal errors.Footnote 64 An abbreviation may have more than one meaning and may therefore be susceptible to misinterpretation,Footnote 9 particularly if users are unfamiliar with the intended meaning. Practices and terminology may vary among different healthcare professionals and groups (e.g., pharmacists, nurses, physicians), as well as between clinical specialties, or even between patients and healthcare professionals.

Recommendations

General

- Minimize use of abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations in health product packaging and labelling.Footnote 9Footnote 64

- Avoid the use of error-prone abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations.Footnote 9Footnote 64 Refer to ISMP Canada's "Do Not Use" listFootnote 64 for further details. This list (adapted from a list prepared by ISMP USFootnote 65) takes into account medication errors voluntarily reported to ISMP Canada for which the reporter identified an abbreviation, symbol, or dose designation as a potential contributing factor in incidents causing harm or having the potential to cause harm.

- Ensure that any abbreviations used provide information that is useful and easily identifiable to the users (i.e., healthcare professionals, patients).Footnote 6

- An abbreviation should not be ambiguous or otherwise have the potential to be misinterpreted by the user. In particular, avoid abbreviations that indicate dosing schedules. (For example, "QD" may be read or misinterpreted as "QID", and "OD" may be interpreted as either "oculus dexter" [Latin, meaning "right eye"] or "once daily").Footnote 6

- Use international or national standards for abbreviations (e.g., abbreviate "milliliters" as "mL"Footnote 64).

Note: The symbol "µg" (meaning "microgram") conforms to the International System of Units (SI) and is often used in scientific literature. However, for labelling purposes, the abbreviation "mcg" should be used instead.Footnote 4 The Greek letter "µ" may be difficult to see in some print and size formats and may be misread as the letter "m" (i.e., "mg" for "milligrams", rather than the intended "µg" for "micrograms"). - The proper or common names of health products and any medicinal ingredients in the product should not be abbreviated.Footnote 4Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 64 Product confusion errors can result when similar abbreviations are used for multiple products (e.g., MSO4 [morphine sulfate] and MgSO4 [magnesium sulfate]).

- Whenever possible, avoid the use of abbreviations on vaccines (e.g., Tdap and DTap). Abbreviations have been identified as contributing factors in vaccine selection errors.Footnote 66

- Define abbreviations used on any product dose delivery devices provided. Ensure that abbreviations used on such devices are consistent with abbreviations used on product labels and packaging, such as label directions, outside packaging (carton labelling), containers, and any accompanying written materials.

- Comprehension testing for any new abbreviation is highly recommended. (Refer to Appendix 2, "Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging".)

Route of Administration

- Express in full any uncommon route of administration (e.g., intrathecal), as it may be unfamiliar to users and use of an abbreviation may result in confusion.Footnote 26 Other abbreviated routes of administration should be explained in full at least once if used elsewhere in the labelling.Footnote 4

3.3.7 Bilingual labelling

Background

Bilingual labelling may pose challenges for the readability of inner and outer labels because of the possibility of crowding of information. Healthcare professional, patient, and consumer feedback gathered in the development of the guide highlighted the following concerns:

- ensuring adequate space for both English and French text, while preserving white space especially when space is restricted (e.g., small containers). French text tends to be slightly longer than the corresponding English

- ensuring accuracy and meaning of health product information is preserved in both languages

- ensuring standardization and consistency of formatting for bilingual text on health product labels (e.g., product name, salt forms of the drug, placement of certain pieces of information, prominence of specific information)

- recognizing subtle differences between English and French in how information is presented and interpreted (e.g., use of a period [English] or a comma [French] to denote the decimal)

Recommendations

General Principles

- Consider bilingual labelling early in the label and package development process, to accurately determine the amount of label space needed to accommodate required product information.

- Inclusion of both languages on the label (and within a technology, e.g., automated voice instructions) is preferred.

- If including English and French on the same panel where space is limited, consider how best to display key information in a consistent manner, within and across product lines. (Refer to Appendix 1, "Glossary" for definition of key information.)

Organization of Information

- For product packages or containers with multiple panels or sides (e.g., an outer box), it is preferable to dedicate an entire label panel for information in English and another for information in French.

- Where packages have only one or two panels available or packages have limited space, consider using different types of labels or innovative labels (e.g., peel-back labels) to accommodate information in both languages. Novel label formats should comply with applicable regulations and guidance documents.Footnote 1Footnote 4 (Refer to section 3.5.2, "Small Containers and Small-Volume Containers".)

- Identify commonalities in English and French for the key information, and determine if the information can be combined to save space. When information (i.e., the drug name) is the same in English and French, consider combining this, instead of repeating all details in both languages.

Expression of Strength or Concentration

- For large numbers (greater than 9999), use a thin space, rather than a comma, to separate digits into groups of three (e.g., 10 000). (Refer to section 3.4.2, "Expression of Strength".)

- Although in English a comma is frequently used to separate groups of digits in large numbers (e.g., 10,000), in French a comma may be used to denote the decimal point. The meaning of a comma may therefore be unclear for some users.Footnote 67

- According to the SI system of units, a decimal or decimal marker "shall be either the point on the line or the comma on the line" and "for numbers with many digits, the digits may be divided into groups of three by a thin space, in order to facilitate reading. Neither dots nor commas are inserted in the spaces between groups of three."Footnote 67

- Ensure that the gap between numbers is large enough to indicate that the numbers are grouped in threes, but not too large, so that the groupings will still be interpreted as representing one number.

- Consider how to standardize the display of product concentration when the unit of measure differs in the two languages (e.g., "units" in English, "unités" in French). Considering the commonalities of key information may help for combining information.

- For product packages with no distinct panels or sides (e.g., ampoules, vials), take into account the field of view available for the key information. (Refer to section 3.4.2, "Expressions of Strength", for more than one expression of strength on a label.)

- The CSA standard, Labelling of Drug Ampoules, Vials and Prefilled Syringes, also provides direction on how French and English may be applied to ampoules, vials, and prefilled syringes.Footnote 15

3.3.8 Logo, branding, and trade dress

Background

Whereas logos, trade dress and branding can assist in differentiating products from different manufacturers, incident reports have indicated that they have the potential to contribute to errors and impede the safe use of health products.Footnote 8 The following issues, among others, have been identified:

- Trade dress may be a factor in look-alike labelling and packaging, particularly for

- products from the same sponsor

- items across a product lineFootnote 8

- generic products, where there appears to be a tendency to create or standardize a look across all product linesFootnote 8Footnote 68-70

- A brand (proprietary) name may be given more prominence than the proper or common name on drug labelsFootnote 42 (i.e., beyond what is stipulated within the Food and Drug Regulations [C.01.004]Footnote 18).

- Graphic elements and "branding" text may interfere with the clear presentation of information that is important to the user.Footnote 71 In particular, these aspects of labelling may prevent differences in important information (e.g., strengths, ingredients, indications) from being clearly evident and noted at the time of selection or administration.

Issues can also arise after redesign of a well-known product label. Reasons for a redesign may include standardizing the look of products nationally or internationally,Footnote 72 fulfilling marketing purposes, or revising certain aspects of the label to help ensure that errors do not recur. Label redesign requires a balance, such that any existing positive design aspects are maintained for the benefit of users. It has been noted that "while not always feasible, it is important to retest the label designs as they are modified for various purposes, to ensure the changes cause no disruption to the system and user performance."Footnote 73

Recommendations

- Logos and trade dress on product labels should not distract the user or impede the effective communication of key information to the user.Footnote 4Footnote 8Footnote 17Footnote 42

- Strive for balance between the use of corporate trade dress and the presentation of key information on labels. While prominence of trade dress and branding may assist in locating a specific product within the retail environment, it may make it difficult for users to distinguish between different products or different strengths of the same product.Footnote 8

- Consider the amount of space required for a logo and how much space will be available for product information on the remainder of the label.

- Ensure that key information within a product line is clearly differentiated among products to avoid look-alike confusion and the potential for selection error.

- Clearly distinguish different strengths of the same health product or the presentations of different health products by the same manufacturer. Consider the use of colour, together with other elements of the label and package, such as size, shape, or features of the container closure.Footnote 8Footnote 74

- When making changes to the label or package, consider user testing before release on the market, to help reduce the potential for unintended consequences (e.g., when rebranding or adding to a product line).Footnote 33

3.3.9 Permanence

Background

The safe labelling of health products ensures that all information is readable for the duration of the shelf-life of the product.Footnote 41 It has been noted that important information on product labels may be inadvertently removed with handling and use.Footnote 75

Recommendations

- Ensure that print on products will remain legible for the entire life of the product, taking into consideration transportation and storage conditions, as well as environments of use.Footnote 41

- Consider special technologies, such as smudge-resistant paper stockFootnote 76 and inks containing adhesives, which will bond to a variety of surfaces, including plastics.

- Use inks that are resistant to isopropyl or ethyl alcohol and that will be durable enough to withstand normal handling, particularly for injectable products (e.g., ampoules, vials, prefilled syringes).Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 35

3.4 Label information

3.4.1 Key elements on the principal display panel

The principal display panel of a label is the first interface between the user and a health product. It is an important factor in product identification and selection. Health Canada regulations specify information that is required to appear on the principal display panel of a product (Food and Drug Regulations C.01.004).Footnote 18

Sponsors are expected to be familiar with the regulatory requirements for their particular product.

In addition to the information required by regulations, eight key elements were identified by the expert advisory panel of healthcare professionals, consumers, and regulators providing input during the development of this guide. These elements assist the user to correctly select a product and use it appropriately. These were noted to be the key pieces of information for inclusion on the principal display panel of health product inner and outer labels (see note below). They align with national and international standards and safety literature, but do not incorporate all of the information required by regulation or guidance for each type of health product. For example, the drug identification number (DIN) is required by regulation, yet is not listed among the eight key elements.

The eight key elements are:

- brand name of health product

- non-proprietary name (proper or common name) of health product

- strength, with or without total amount per total volume

- dosage form

- route of administration (other than for oral solids, such as tablets)

- critical warnings, as relevant

- population, as relevant (e.g., pediatric)

- storage instructions, as relevant

Note: It is vital to consider each specific product, its users, the environment(s) of use, and the regulatory requirements to determine which of the eight key elements may be needed to ensure safe use. (Refer to section 3.5.2, "Small Containers and Small-Volume Containers".) For example, oral liquid products may be used in environments such as hospitals or even homes where intravenous access may exist. Because it is possible for any liquid product to be injected,Footnote 77 or a suppository to be ingested, it is critical to state the intended route of administration (oral for the liquid, rectal or vaginal for the suppository) on the principal display panel of the label on such products.

For very small containers, the inner label may not have the space to include all of the identified key elements. The nature of the product will then suggest which elements are most critical for safe selection and use and should be included on the inner label taking into consideration the regulatory requirements.

Storage instructions are one of the key elements that are not addressed in a separate section of this guide. It may be relevant to include such instructions on the principal display panel if the typical storage requirement for the product is other than room temperature. For example, products that require refrigeration are less typical, and refrigeration instructions for products requiring low storage temperatures should therefore appear on the principal display panel as an alert to users. This is especially important for vaccines that require refrigeration.

3.4.2 Expression of strength

Background

Expression of strength is a key piece of information on a health product label. Unclear expression of strength, or a missing expression of strength, can impede correct selection and use of products. Individual products may be available in multiple strengths, and strength may be expressed in a variety of units; as a result, product strengths can be easily misinterpreted.Footnote 10

The following list presents examples of labelling practices that may introduce confusion because of the way in which the strength of a health product is expressed:

- presenting strength in more than one formFootnote 10 (e.g., as both a concentration and a percentage)

- using different units of measure on the same labelFootnote 9 (e.g., millimoles [mmol] and milligrams [mg])

- using different units for volumesFootnote 78 (e.g., "per mL", "per mm3", "per cc")

- presenting a variety of numbers on the principal display panel, such as the strength (in one or more expressions) and the total number of units in the packageFootnote 8

- placing the drug strength (a numeric value) and the unit or pack size (another numeric value) in close proximityFootnote 9 (refer to section 3.3.3, "Proximity and Compatibility of Information on the Principal Display Panel".)

- mismatching the volume of health product in the container with the expression of strength (e.g., where the entire content of a vial is less than 1 mL, but the strength expression on the label gives the amount of product per millilitre)Footnote 8

- placing more solution in the container than is needed to reconstitute a productFootnote 10 or more that is needed to deliver the required dose of a productFootnote 79 (i.e., overfilling the container, such that manipulation may be required to withdraw a smaller amount or to remove excess product to prepare the dose to be delivered)

- using trailing zeros (e.g., "2.0", "2.50") or naked decimals (e.g., ".2"); if the decimal point is not correctly perceived, a 10-fold over- or under-dosing error could occurFootnote 8Footnote 64

- using certain SI unit abbreviations that are prone to being misread (e.g., for "microgram", the use of "μg" rather than "mcg" may be difficult to discern in some print and size formats and could be misread as "mg"Footnote 4)

- inconsistency between the labelled product strength and the "Dosage and Administration" section of the product monograph or the prescribing information.

Other important issues related to the expression of a product's strength may increase the possibility of confusion and error. With regard to health products in the form of a salt, potencies and content of the active component can differ significantly among various salt forms. Therefore, there may be inconsistency in how information is presented and how users refer to (or understand) the strength. Users may find it difficult to distinguish between the dose of an active ingredient's salt form and the dose of the active moiety itself.Footnote 80 For example, flupenthixol is available in three salt forms, hydrochloride, acetate, and decanoate. Oral tablets are in the form of the hydrochloride salt. Injectable products are in the form of the acetate salt, where 50 mg provide 42.25 mg of flupenthixol, and the decanoate salt, where 200 mg provide 144.4 mg of flupenthixol. Thus, confusing a dose of 100 mg between the two salts would provide either 72.2 mg or 95.5 mg of the active drug, as well as having a dramatic difference in absorption rates. It is also important to differentiate between two or more formulations of the same active ingredient, especially when the doses differ significantly. Incorrect dosing due to confusion over which formulation was being used (e.g., liposomal vs. conventional amphotericin B) has resulted in serious adverse events, including death.Footnote 81

For health products requiring dilution to achieve a final concentration for use, the strength expressed on the label may differ from what is required for the final product. Unclear dilution instructions have caused medication incidents.Footnote 82 The following issues have been observed:

- Product concentration relative to the amount of diluent required for reconstitution can cause confusion, in that the final volume to be administered to a patient may differ from the volume of diluent used.

- Complexity can be added by requiring use of a specific or proprietary diluent or by requiring more than one step-such as reconstitution, followed by dilution-before the product is suitable for administration.

- Dilutions required for pediatric use of a product may differ from those required for adults. Expressions of strength that will aid the user to make appropriate calculations for the more vulnerable pediatric population are therefore important. It is ideal to have commercially available pediatric-specific formulations and concentrations available for administration to children.Footnote 83

Fractional strengths can be more error-prone and confusable, a situation that must be considered when new strengths are added to existing product lines. An example is transdermal fentanyl, which was made available as both 12.5 mcg / h and 125 mcg / h; 10-fold dosing errors have occurred because the decimal point was overlooked.Footnote 84 This problem has now been remedied by changing the displayed strength of the 12.5 mcg / h product to read "12 mcg / h". In cases like this one, the decimal point and matching digits can cause confusion; when the drug involved is a high-alert medication, such as an opioid, the effects could be significant.

Dosage forms that release or deliver an amount of product different from the total amount in the container may need careful consideration. An example is a nicotine inhaler, which contains 10 mg per cartridge but delivers only 4 mg. Such a discrepancy may cause confusion for both the prescriber and the user, because of a mismatch between how the prescribed dose is communicated and how the strength is presented on the label. Furthermore, if the available drug is interpreted as 10 mg of nicotine per cartridge, this could also result in a higher dose and an unnecessary step-up of nicotine therapy when converting from the inhaler to a longer acting transdermal nicotine patch.

Recommendations

General Principles

- Express the dose strength of a health product in an appropriate metric system unit,Footnote 15Footnote 16 except in situations where other units of measure are accepted and required, such as units of potency for biological medicinal productsFootnote 33 and percentage strength for topical preparations. Numbers without units of measure should not be used to express product strength.

- Use "mcg" rather than "μg" for "micrograms".Footnote 64

- Health Canada recommends that the abbreviation "mcg" be used.Footnote 4 The use of "µg" may be difficult to see in some print and size formats and the Greek letter "μ" might be misread as "m",Footnote 4 which can be a contributing factor to dose errors. (Refer to section 3.3.6, "Use of Abbreviations, Symbols and Dose Designations".)

- For numbers with five digits or more, separate the digits into groups of three by a thin space to help prevent misreading (e.g., 1000 mg but 10 000 mg).Footnote 67 This format is compatible with both official languages (unlike use of the comma or period) and is the format recommended by the SI systemFootnote 67 and by Public Works and Government Services Canada.Footnote 85

- Consider spacing between text characters to enhance clarity. For example, leave sufficient space around the slash character ("/") to optimize legibility, given that this character could be misinterpreted as the number "1" (one) or the letter "l" (L).

- Do not use the slash character ("/") to denote the word "or", and avoid its use for separating different pieces of information. Misinterpretation resulting in error has been reported with such uses of this character.Footnote 86

- Avoid the use of trailing zeros (e.g., "2.0", "2.50") and naked decimals (e.g., ".2").Footnote 64

- To the extent possible, ensure consistency between the units expressing the product strength and the units used for dosing instructions.Footnote 9

- Avoid placing expressions of strength near other numeric information, such as the number of units in the package.Footnote 8(Refer to section 3.3.3, "Proximity and Compatibility of Information on the Principal Display Panel".)

- Take older expressions of strength into consideration when comparable products or products of the same class are prepared for market.

- Changes to expressions of strength, particularly for critical and specialty products, may be problematic. Before changing the expression of strength of a product to different units or a different format, it is recommended to have the new label and package undergo user testing. (Refer to Appendix 2, "Human Factors Principles and Assessment Methods Relevant to Labelling and Packaging".)

Expressing Strength

- Avoid using both metric (SI) units and other units (e.g., milligrams combined with international units)Footnote 87 to express the strength of a given ingredient on the principal display panel of the label. Equivalencies may be better expressed and presented on a side or back panel.

- For dosage forms such as transdermal patches, implants, and inhalers or inhalators include the total quantity of the medicinal ingredients (per patch, implant, or inhaler) and the dose delivered per unit of time and the duration of use on both the inner and outer labels.Footnote 4

- Label the dosage form or delivery unit itself (e.g., patch, implant, cartridge) with the delivery rate of the drug (e.g., "x mg / day").Footnote 4

- Where the total quantity in the delivery unit does not correspond to the delivered dose, the total amount of drug in the unit may be presented on a side or back panel of the package, rather than on the principal display panel. This is intended to reduce confusion about dosing and to make the information readily available in the event of misuse. (Refer to section 3.5.5, "Transdermal Patches".)

Expressing Concentration

- For liquids intended for oral administration, declare the quantity of each medicinal ingredient per millilitre (e.g., 5 mg / mL)Footnote 4Footnote 33 or per usual volume to be takenFootnote 4Footnote 88 (e.g., 25 mg / 5 mL). Products that are intended for use by patients of different ages may best be labelled with the quantity of medicinal ingredient per millilitre. This allows the user to calculate the needed dose across a range of ages, with specific instructions to be provided in the product monograph. Oral dosing devices are important tools to assist in correct dosing. (Refer to subsection "Dosing Devices" in section 2.5.1, "General Packaging Considerations".)

- For small-volume parenteral products (100 mL or less),Footnote 89 declare the quantity of each medicinal ingredient per millilitre (e.g., 5 mg / mL), as well as the total amount per total volume (e.g., 20 mg / 4 mL).Footnote 4

- If the unit volume is 1 mL, there should be only one expression of strengthFootnote 89 (e.g., 5 mg / mL or 5 mg per mL).

- When the total quantity per total volume is present on the principal display panel of a label, ensure that this information is more prominent than other expressions of strength.Footnote 26Footnote 89 The total amount per total volume should be the primary expression followed by the strength per mL presented in close proximity.Footnote 34Footnote 89

- Use one or more of the techniques described in sections 3.3.1, "Type Style and Size", and 3.3.5, "Colour and Contrast", of this guide (e.g., display the information first, print the information in a larger type size, use bold type, display the information with greater contrast). For example, display "400 mg / 4 mL" more prominently than "100 mg / mL", presenting the less prominent expression within parentheses or in smaller type.

- For products intended as a single dose, in a ready-to-use format (e.g., prefilled syringes), express the strength as the quantity of active ingredient in the volume provided (e.g., 6 mg / 1.2 mL, 4 mg / 0.8 mL). The concentration per mL can be included in the product prescribing information.

- For containers with less than 1 mL total volume, express the strength as the quantity of active ingredient in the volume provided (e.g., 3 mg / 0.5 mL).Footnote 89

- Avoid using percentages to express concentration or strength when usual dosing is based on a weight or volume calculation of the amount to be administered.Footnote 9Footnote 33 The expression of strength should match the units of measure described in the prescribing information to avoid error.Footnote 9

- Avoid indicating strength in terms of a percentage or a ratio (e.g., 1:1000)Footnote 10Footnote 90 to minimize additional calculations that may be required of the user. Exceptions may be health products for which the ingredient strength is included as part of the name (e.g., local anesthetics).Footnote 33

- Epinephrine is one health product for which multiple strength expressions have been used with concentration presented in milligrams per millilitre (mg / mL) or as a ratio (e.g., 1:100 000). For local anesthetics in which epinephrine is a secondary ingredient, the epinephrine component may be expressed as a ratio (e.g., lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100 000). If epinephrine is the only ingredient, the strength should be expressed as "mg / mL"Footnote 91 (e.g., 1 mg / mL) and as the total amount in the total volume (e.g., 10 mg / 10mL), as noted in a previous bullet.

- For large-volume parenteral products, including dialysis solutions, declarations in percentages or in weight per 100 mL (e.g., 1% w/v or 1 g / 100 mL) are considered acceptable, as is the total amount per total volume (e.g., 2.5 g / 250 mL).Footnote 4 The total volume in the container should also be stated somewhere on the principal display panel.

Reconstitution and Dilution

- For health products in a liquid form that require dilution before use, include a relevant warning statement (such as "Dilute Before Use") on the principal display panel of both inner and outer labels. Potassium chloride concentrate for parenteral use is one product that requires this warning on the container closure. (Refer to section 3.4.3, "Critical Warnings".)

- For products to be reconstituted or otherwise manipulated (e.g., powders requiring reconstitution for oral or parenteral administration), show the total amount of powder or dry product in the primary container on the principal display panel of both the inner and outer labels. Ensure that this number is most prominent and that it is not placed close to the expression of final strength. (Refer to section 3.3.3, "Proximity and Compatibility of Information on the Principal Display Panel".)

- For health products in a powder form that require reconstitution followed by dilution before use, include a relevant warning statement (e.g., "Acetazolamide for Injection. Dilute Before Use") on the principal display panel of both inner and outer labels.

Expressions of Strength for Pediatric Products

- For products intended for either adult or pediatric use, present the expression of strength on the principal display panel in a format that simplifies calculation of pediatric doses. Bear in mind that expressions of concentration may need to be applicable to both populations. For example, a product that is normally administered to an adult as a 1 g dose may be administered to a child as a weight-based dose (e.g., milligrams per kilogram [mg / kg]). Thus, if a vial contains 1000 mg in 10 mL (100 mg / mL), it may be better to state the primary strength expression as "1 g / 10 mL" to aid in adult dosing, with the secondary strength expression, 100 mg / mL, facilitating calculation of doses smaller than 1 g.

- For products that require different dilutions for adult and pediatric administration, a warning may be needed on a side panel to indicate the specific dilutions required to produce a ready-to-administer dose for the intended patient population.

Other

- Where different formulations, salts, drug delivery systems, or special conjugates (e.g., antibody-drug conjugates) of the same drug have significantly different dosing regimens, clearly indicate the product type on the label, in close proximity to the strength of the product (e.g., amphotericin B vs. amphotericin B liposome vs. amphotericin B lipid complex, trastuzumab vs. trastuzumab emtansineFootnote 92.)

3.4.3 Critical warnings

Background

A critical warning is one that must be highlighted and conveyed to every user before product administration, to facilitate correct product use and to prevent an error that may result in serious harm or death. Critical warnings must attract the attention of users and must create a balance between being explicit yet concise.Footnote 55Footnote 93Their goal is to ensure that users notice, read, understand, and comply with the warning message.Footnote 94 Critical warning statements are often presented framed or boxed in both the product monograph and patient information leaflets, and are commonly shown on the principal display panel of the inner and outer labels.

The design of the label and package should not convey a conflicting message to users. For example, if a topical medication is provided in a vial similar to that used for injectable products, or an inhalation medication is provided in a capsule format, a warning may not be enough to overcome the user's experience and customary handling and use of similar packages or formats.Footnote 95-98 Additional safeguards that consider human limitations, the ways in which users will interact with the product, and the environment in which this interaction occurs will likely need to be incorporated into the product design to help minimize human error.Footnote 99Footnote 100 A warning added to a label may not be sufficient to alert the user to a critical situation.Footnote 101 Ideally, the label and package will align and together will convey the product's intended use.Footnote 100 (Refer to section 3.5.1, "General Packaging Considerations".)

Recommendations

General Principles

- Refer to pertinent Health Canada regulations and policies for warning statements and symbol requirements applicable to specific products.

- Ideally, a critical warning should have the following features:

- It should appear on the principal display panel,Footnote 26Footnote 46 on both the inner and outer labels. All other warnings should appear on a side or back panel, or a reference should be made to a package insert or patient information leaflet distributed with the product.

- It should be located in an area where users will have to interact with it in the course of using the product. For multiple-use products, critical warnings should not be located in an area that would be discarded after an initial interaction.Footnote 94Footnote 102 The most noticeable and effective warnings are placed in such a way that the task is temporarily interrupted and the user must physically interact with the warning before continuing.Footnote 55Footnote 59

- It should be suitable for the intended users, taking into account the knowledge, training, and experience of those who may encounter the warning. Footnote 55Footnote 59

- Critical warnings should not be

- broken up by other information (e.g., logos, background text-graphics)Footnote 37

- placed only on the inside panel of the outer package (e.g., printed on the inside of the box)

Critical Warning Statements

- Use statements that are as brief as possible, with words that are as explicit as possible.Footnote 4Footnote 93Footnote 102-104 Critical warnings provided in this manner are effective in holding the attention of users, align with the principles of plain language, accommodate the requirements of bilingual labelling, and can assist in avoiding clutter on a label.

- Use of a signal word (e.g., "WARNING" or "ALERT") is one component of an effective warning that can help to draw attention to important information.Footnote 55Footnote 59Footnote 102Footnote 104

- If space allows (e.g., on the outer label), consider the following additional components that can help to effectively communicate the warning:

- a description of the hazard (e.g., "paralyzing agent")

- the consequence of non-compliance (e.g., "may cause respiratory arrest")

- the required or desired behaviour (e.g., "patient must be ventilated")Footnote 105

- Use affirmative statements,Footnote 33Footnote 94 such as "For Intravenous Use Only-Fatal if Given by Any Other Route." Affirmative statements are less prone to confusion than are non-affirmative statements (such as "Not for intrathecal use"), in which the word "not" may be overlooked.Footnote 9

Prominence

- Avoid presenting entire sentences in capital letters or italic type, as these formats are difficult to read.Footnote 42Footnote 46Footnote 59Footnote 106

- Use white space around a critical warning to help emphasize the information.Footnote 42Footnote 59Footnote 93Footnote 103

- Consider a combination of the following features to draw attention to a warning, as the combination may be more effective than any one attribute on its own:Footnote 55Footnote 94

- upper case letters to emphasize signal wordsFootnote 42Footnote 46Footnote 106

- large, bold printFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 20Footnote 106Footnote 107

- high contrast

- colourFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 106

- bordersFootnote 102

- box frames or keylinesFootnote 10Footnote 103

- pictorial symbolsFootnote 108

- Use colour prudently to bring attention to warnings and to differentiate warnings from other text.Footnote 9Footnote 42

- Particular colour combinations for words and background are associated with each of the three signal words: red background with white lettering for "DANGER", orange background with black lettering for "WARNING", and yellow background with black lettering for "CAUTION".Footnote 94Footnote 109 Red is typically used to communicate the highest level of hazard, followed by orange and yellow.

- Consider using red or orange, as these colours have higher hazard-association and may be associated with higher compliance by users. However, there is some controversy about the significance of the colour red, and concerns have been raised that the increased frequency of its use may dilute its effect (e.g., red text has been used on solution bags to warn about the route of administration or other aspects of product use, to highlight medication contents, and to highlight specific electrolyte contents for intravenous replacement and maintenance fluids).Footnote 8

Symbols

- Limit the use of symbols to warnings required by Health Canada and those that have demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing user understanding and product use.Footnote 65Footnote 104Footnote 110 Warning statements can be identified more quickly if they include symbols or pictures that are bold, have high contrast, are simple in form, and closely represent the intended message.Footnote 59Footnote 105

- To ensure that these criteria are met, consider user testing of new or unfamiliar symbols, particularly if the product label and package are to be used across cultural groups.Footnote 55

Labels, Caps, and Ferrules

- Critical warnings should be the only information that appears on the top (circle) surface of the ferrule or cap overseal of an injectable product.Footnote 89 If information is placed on the side of the ferrule (e.g., numbers or letters representing a lot number or a code number), it must not detract from the warning on the ferrule.Footnote 111

- Other than the critical cautionary statement(s), no other information of any type should appear on the top surface of any ferrule or cap overseal of an injectable product.Footnote 111

Product-Specific Critical Warnings