Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy: Overview

Our approach to substance use related harms and the overdose crisis

About the strategy

About

The Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy guides how we work to save lives and minimize substance use related harms for:

- people who use drugs and alcohol

- their families

- communities

The substances covered by the strategy are:

- alcohol

- tobacco

- cannabis

- vaping products

- precursor chemicals

- controlled substances

The strategy focuses on:

- federal legislation and regulation

- national surveillance and research

- services and supports for populations served by the federal government

- funding for projects that help address substance use and prevent related harms

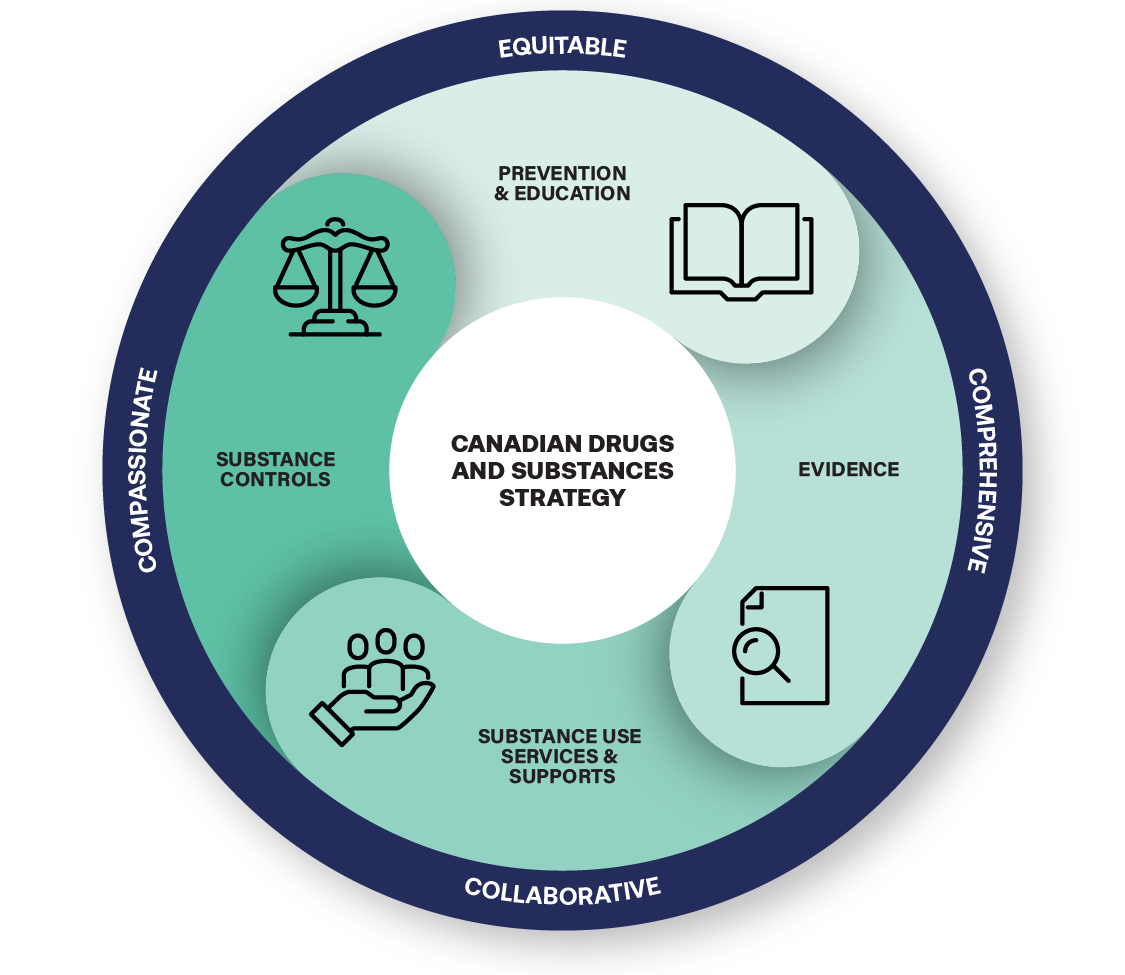

Foundational elements

This strategy focuses on 4 integrated action areas related to substance use.

Prevention and education

Prevention and education initiatives act to prevent, reduce or delay substance use related harms. They also increase awareness and knowledge about the effects and risks of substances.

Evidence

Supporting research and gathering data to help inform substance related policies and decisions.

Substance use services and supports

Services that support a continuum of care, like treatment, harm reduction and recovery options for people who use drugs and alcohol. These services can help people reduce their substance use and the likelihood of related harms.

Substance controls

Giving health inspectors, law enforcement and border control authorities the tools, like laws and regulations, to address public health and safety risks associated with the use of substances. These risks include the harms of the illegal drug market. Substance controls also allow for legitimate uses of controlled substances, like prescription drugs or in research.

Guiding principles

The strategy has 4 guiding principles. The strategy is:

Compassionate

The strategy treats substance use as a health issue and people who use substances with compassion and respect. It recognizes stigma as a barrier to health and other services.

Equitable

The strategy recognizes the distinct ways that substance use policies and interventions can affect:

- Indigenous Peoples

- African, Caribbean and Black populations

- other racialized populations

- other marginalized populations

Collaborative

The strategy engages:

- communities

- stakeholders

- Indigenous Peoples

- international partners

- all levels of government

- law and border enforcement partners

- people with lived and living experience

Comprehensive

The strategy recognizes that substance use is different for everyone, and requires a range of policies, services and supports to promote overall wellbeing. The strategy also recognizes that many substance use related harms arise from:

- illegal drug trade

- the toxic illegal drug supply

Why we need a strategy

The Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy is important for several reasons. High rates of substance use harms negatively impact people's:

- health

- livelihoods

- relationships

The current overdose crisis and an increasingly toxic illegal drug supply are also causing deaths and other substance use related harms.

In addition, people seeking services and supports face barriers in accessing:

- treatment

- harm reduction

- recovery-oriented services

Some of these barriers include a lack of integration of mental health and substance use services and supports.

The strategy also aims to address intersecting social issues that cause further harm, like:

- stigma

- housing

- systemic racism

- unequal access to care

- mental health and trauma

The strategy will also guide our efforts to address complex challenges like:

- rising societal costs related to substance use

- drug trafficking profits that fuel community violence and fund other crimes, like human trafficking

Substance use is complex and there is no one-size-fits-all solution to preventing or reducing its harms. This is because substance use exists across a spectrum with varying stages of benefits and harms. Substance use is different from one person to another and a person's pattern of use can change over time.

The strategy brings together partners across:

- health and social systems

- the criminal justice system

- law and border enforcement

This contributes to providing a range of services and supports that address the unique needs of people in Canada.

Learn more:

Funding opportunities

We offer funding to programs and initiatives for a range of services and supports that:

- help people who use drugs and alcohol

- reduce substance use harms in Canada

This includes:

- not-for-profit organizations

- community-led organizations

- other levels of government, like:

- municipal

- provincial

- territorial

Funding is provided through these programs:

- Youth Justice Fund

- Harm Reduction Fund

- Substance Use and Addictions Program

- Drug Treatment Court Funding Program

- Indigenous Services Canada's Mental Wellness Program

- Youth Substance Use Prevention Program

- Contribution Program to Combat Serious and Organized Crime

Funding through the National Crime Prevention Strategy is also available, including the:

- Youth Gang Prevention Fund

- Crime Prevention Action Fund

- Northern and Indigenous Crime Prevention Fund

Funding is also available through the Reaching Home: Canada's Homelessness Strategy program. This community-based program:

- aims to prevent and reduce homelessness in Canada

- supports the delivery of various services and integrated supports for individuals and families experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness

Funding for the Strategy is primarily delivered through community entities.

Performance measurement and results

Our shared goal is to reduce overall rates of substance use related harms and overdose deaths in Canada. Our success will depend on working closely with our partners and stakeholders.

We're committed to publicly reporting on our progress towards the long-term outcomes of this strategy. Over the next 5 years, we'll measure the strategy's impact through these expected outcomes:

- People living in Canada have more knowledge, skills and resources related to substance use and its harms

- More equitable access to services and supports to reduce substance use related harms

- Population-specific research, data and intelligence on substance use related harms and the illegal drug market are available to support evidence-based decision-making

- Better support for enforcement and regulatory activities related to controlled substances and precursor chemicals used to make controlled substances

In the medium term, the strategy will contribute to these outcomes:

- People living in Canada change their behaviours to reduce substance use related harms

- Legislation, regulations, and government activities to:

- disrupt illegal activities

- support legitimate uses of controlled substances and the precursor chemicals used to make these substances

We're committed to publicly reporting our on progress towards the outcomes of this strategy. Follow our progress and see our impacts in our 2023 to 2024 Departmental Plan and reports.

Consultations

To help develop the strategy, we:

- consulted with people across Canada on how to strengthen our approach to substance use issues

- reviewed the Expert Task Force on Substance Use's findings on how to strengthen our public health approach to substance use

Learn more:

Substance use related harms affect us all

At least 200 lives are lost per day due to substance-related harms linked to drugs, tobacco and alcohol

Over 38,000 opioid related deaths in Canada from 2016 to March 2023

Substance-related harms contribute to over 270,000 hospitalizations per year