Defending Wellness: A Systemic Investigation of the Canadian Armed Forces’ Health Care Complaint Process

Mandate

The Office of the Department of National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman was created in 1998 by Order-in-Council to improve transparency in the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces, as well as to ensure the fair treatment of concerns raised by Canadian Armed Forces members, Departmental employees, and their families.

The Office is a direct source of information, referral, and education for the members of the Defence community. Its role is to help individuals access existing channels of assistance or redress when they have a complaint or concern. The Office is also responsible for reviewing and investigating complaints from constituents who believe they have been treated unfairly by the Department of National Defence or the Canadian Armed Forces. In addition, the Ombudsman may investigate and report publicly on matters affecting the welfare of Canadian Armed Forces members, Department of National Defence employees, and others falling within their jurisdiction. The ultimate goal is to contribute to substantial and long-lasting improvements to the Defence community.

Any of the following people may bring a complaint to the Ombudsman when the matter is directly related to the Department of National Defence or the Canadian Armed Forces:

- A current or former member of the Canadian Armed Forces

- A current or former member of the Cadets

- A current or former employee of the Department of National Defence

- An employee or former employee of the Staff of Non-Public Funds, CF

- A person applying to become a member

- A member of the immediate family of any of the above-mentioned

- An individual attached or seconded to the Canadian Armed Forces

The Ombudsman is independent of the military chain of command and senior civilian management and reports directly to the Minister of National Defence.

Abbreviation Guide

- CAF

- Canadian Armed Forces

- CFGA

- Canadian Forces Grievance Authority

- CFHS

- Canadian Forces Health Services

- DAOD

- Defence Administrative Orders and Directives

- DGHS

- Director General Health Services

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- DQ&P

- Directorate Health Services Quality and Performance

- D Med Pol

- Director of Medical Policy

- CF H Svcs Gp

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group

- MGERC

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- QR&O

- Queen's Regulations & Orders

Executive Summary

Our investigation focused on how the CAF handles health care complaints. Our objective was to identify instances of unfairness and inequity resulting from the lack of a formal health care (medical and dental) complaint process for members and to identify some of the impacts of this on CAF members.

We found that the lack of a formal process causes inconsistencies in addressing health care complaints across Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) centres. Although some CFHS centres developed their own Standard Operating Procedures, there is no overall CFHS Instruction that governs the administration of health care complaints.

CFHS has been working on formalizing a process for the past several years but has been unable to accomplish it due to workload demands.

Since no formal health care complaint instruction exists, members often resort to the grievance process. This causes delays, potential inequitable outcomes and moves away from Person-Partnered Care.Footnote 1 Additionally, the absence of a centralized tracking system for health care complaints prevents the CAF from identifying gaps and systemic issues, hindering them from making improvements.

Findings

This report presents three findings:

- Finding 1: Health care complaints are addressed inconsistently across Canadian Forces Health Services centres due to the lack of a formal health care complaint process.

- Finding 2: Members often use the Canadian Armed Forces grievance process due to the lack of a formal CAF health care complaint process.

- Finding 3: A centralized tracking system does not exist for health care complaints.

Recommendations

We make two recommendations:

- Recommendation 1: By January 2025 that the Canadian Armed Forces dedicate resources to implement a Canadian Forces Health Services Instruction on the administration of CAF health care complaints, and

- Recommendation 2: By May 2026 that the Canadian Armed Forces dedicate resources to develop a centralized tracking system for health care complaints submitted across Canadian Forces Health Services centres and to Canadian Forces Health Services Group directly.

Our recommendations, if implemented, will bring lasting improvements for the wellness of CAF members. Formalizing and communicating the process to address health care complaints is the basis for fair and more efficient resolution. This goes hand in hand with the Person-Partnered Care approach, which positively contributes to operational readiness and the wellbeing of CAF members.

Section I: Introduction

Our investigation focused on how the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) handles health care complaints. Our objective was to identify instances of unfairness and inequity resulting from the lack of a formal health care (medical and dental) complaint process for members and to identify some of the impacts of this on CAF members.

Since our office was established, we have monitored issues with health care complaints. For many years, Canadian Forces Health Services Group (CF H Svcs Gp) has been working to develop a policy and a standardized process to address health care complaints. However, this has not yet been formalized.

The provision of high-quality care is essential to the health and well-being of members and crucial to CAF operational readiness. The lack of a formal CAF health care complaint process may cause unnecessary and avoidable delays and inequitable outcomes among CAF members. Unresolved health care complaints can lead to health issues being untreated and increased frustration and stress for members. Retention may be impacted when members perceive that their health care concerns are unaddressed.

In August 2023, we launched an investigation to examine how the CAF addresses health care complaints, including complaints of the quality and type of care provided. This investigation did not examine how the CAF addresses complaints that dispute health care related policy, including concerns related to the Spectrum of CareFootnote 2 and entitlements to care. To better understand the issue, we interviewed individuals in CAF leadership roles responsible for addressing health care complaints. For more information, review Appendix III: Methodology.

Additionally, our investigation neither evaluated the effectiveness or quality of the health care provided to members, such as concerns of malpractice, nor did it assess the roles and responsibilities of Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) staff. Resources to address health concerns including professional conduct will be made available on our website's Educational information page. This investigation covers the period from July 2021, when Health Services Review and Investigation section was stood up under the Directorate Health Services Quality and Performance (DQ&P), to February 2024.

Section II: Context

"The Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) provides health care to Canada's 60,000 Regular Force personnel anytime, anywhere, and to 25,000 Reserve Force personnel whenever required."Footnote 3

The Surgeon General has two roles. First, as the Director General Health Services (DGHS), they are responsible for the CAF Health Programme and health policies, including oversight of quality and performance of the CAF health system. Second, as the Commander CF H Svcs Gp, they are responsible for the delivery of health effects through implementation of the Health Programme and policies thereby ensuring the provision of health services to CAF members. Footnote 4

The Canada Health Act and provincial health insurance legislation exclude CAF members from the category of "insured persons" eligible for health care coverage. The Constitution Act, 1867 provides the federal government with exclusive jurisdiction over the military, including the authority to provide health care to CAF members.Footnote 5 The National Defence Act and the Queen’s Regulations and Orders (QR&Os) elaborate the Federal Government's responsibility for providing this coverage to members.Footnote 6 Therefore, Regular Force members and Primary Reserve Force members on operations or on full-time periods of serviceFootnote 7 can only access health care through CFHS centres. Primary Reserve Force members who work short-term periods of serviceFootnote 8 and members who release from the CAFFootnote 9 receive health care through their provincial or territorial health care.Footnote 10

Members can submit health care complaints through different avenues: directly through their local Base/Wing CFHS centre or to the Health Services Review and Investigation section, the DND/CAF Ombudsman, Integrated Conflict and Complaint Management or the CAF Grievance process. As per the Defence Administrative Orders and Directives (DAOD) 2017-1, Military Grievance Process, "a complaint relating to the provision of CAF health care […] should be directed to the local CAF health care provider" before submitting a grievance.Footnote 11

Canadian Forces Health Services:

The Commander CF H Svcs Gp provides health care services to members through 33 medical centres and 29 dental detachment centres across Canada, and three medical and dental centres outside Canada.Footnote 12

At the strategic level, the DGHS oversees the CF H Svcs Gp.Footnote 13 This group includes DQ&P who reports directly to DGHS, the Director Medical Policy, the Commanding Officer of 1 Dental unit and the Chief Dental Officer.Footnote 14 Local CFHS medical centres are usually led by a Commanding Officer and Base/Wing Surgeon. CFHS dental centres are led by Dental Detachment Commanders. The Senior Medical Authority in CFHS centres is the Base/Wing Surgeon.Footnote 15 Members can make a health care complaint directly to medical or dental staff at their local CFHS centre.Footnote 16

CAF Grievance Process

The QR&O, Chapter 7 – Grievances states an officer or non-commissioned member may submit a grievance where they have been aggrieved by an administrative decision, act, or omission and where no other process for redress exists. The Initial Authority must consider and determine the grievance within four months of its receipt. The grievance can then be escalated to the Final Authority.Footnote 17 No time limit exists for the Final Authority to make their decision. According to the National Defence Act, the Chief of the Defence Staff is the Final Authority in the grievance process.Footnote 18 In certain instances—such as grievances related to the entitlement to medical care or dental treatment—grievances must be referred to the Military Grievances External Review Committee (MGERC) for analysis and recommendation before the Final Authority’s decision.Footnote 19

Figure 1: Canadian Armed Forces grievance process

Figure 1: Text version

The CAF grievance process consists of two levels and begins with the grievor's commanding officer (CO).

Level 1: Review by the Initial Authority (IA)

Step 1—The grievor submits a grievance in writing to their CO.

Step 2—The CO acts as the IA if they can grant the redress sought. Otherwise, the Canadian Forces Grievance Authority assigns an appropriate IA. Should the grievance relate to a personal action or decision of an officer who would otherwise be the IA, the grievance is forwarded directly to the next superior officer who is able to act as IA.

Step 3—The IA renders a decision and, if the grievor is satisfied, the grievance process ends.

Level 2: Review by the Final Authority (FA)

A grievor, who is dissatisfied with the IA's decision, is entitled to have their grievance reviewed by the FA, which is the Chief of the Defence (CDS) or their delegate.

Step 1—The grievor submits their grievance to the CDS (or their delegate) for FA-level consideration and determination.

Step 2—Depending on the subject matter of the grievance, the CDS may be obligated to, or may at their discretion, refer it to the Military Grievance External Review Committee (MGERC). If the grievance is referred for consideration, MGERC conducts a review and provides its Findings and Recommendations report to the CDS and the grievor. Ultimately, the FA makes the final decision on the grievance.

Section III: Findings

This section presents our findings, supporting evidence, and the impact on CAF members and the Defence community.

Our initial consultations with CAF health care authorities, preliminary research, and complaints to our office revealed that no formal policy or process exist to govern the administration of CAF health care complaints. The challenges we found include:

- inconsistencies in the administration of health care complaints across CFHS centres and by CF H Svcs Gp,

- CFHS staff and members lack awareness on how to submit or address health care complaints,

- the CAF grievance process may not always be the best mechanism to address a health care complaint, and

- the lack of a centralized tracking system for health care complaints prevents the CAF from doing trends analysis and ultimately improving the quality of the health care system.

Finding 1: Health care complaints are addressed inconsistently across Canadian Forces Health Services centres due to the lack of a formal health care complaint process.

Current Process

Without a formal health care complaint process governed by a policy, each CFHS centre across Canada follows their own process to address health care complaints.

The Base/Wing Surgeons and Dental Detachment Commanders we interviewed confirmed that CFHS centres have different avenues for members to submit a complaintFootnote 21 and each has different processes for addressing those complaints.Footnote 22 Consequently, the health care authorities who address complaints differ across CFHS centres. Some Base/Wing Surgeons appoint CFHS staff to analyse and investigate complaints, while some manage the complaints themselves.Footnote 23

Although some CFHS centres developed their own Standard Operating Procedures, there is no overall policy that governs the administration of health care complaints. This mirrors what all interviewed Base/Wing Surgeons reported; not all CFHS centres register or track complaints locally, nor do they have service standards to resolve members' complaints.

We interviewed eight Base/Wing Surgeons and Dental Detachment commanders in our investigation. Five of those were unaware of a formal complaint process other than the CAF grievance process. This may be because Base/Wing Surgeons, in their role of senior medical authority, receive complaints that have a high medical nexus and may require review or analysis of patient care procedures that need a medical opinion or review of medical decision. Not all complaints get to the Base/Wing Surgeon level. Primary Care Managers also receive complaints as a first point of contact for most patients.

Members can make a health care complaint directly to medical or dental staff at their local CFHS centre, the Commanding Officer of the clinic or the Primary Care Manager. Interviews with CF H Svcs Gp, Base/Wing Surgeons and Dental Detachment Commanders also identified the DND/CAF Ombudsman, the patient safety incident report, and the regulatory bodies for professional care providers (for example, the national and provincial Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons) as other avenues to submit a complaint.

Awareness of addressing health care complaints

Medical and dental staff

The DQ&P, under the Surgeon General's authority, has guidelinesFootnote 24 on addressing health care complaints for CFHS centres. They also provide a presentation on addressing health care complaints in the Basic and Advanced Medical Officers’ Course and information sessions to individuals who request it.Footnote 25 Medical Officers complete these courses once during their career. The Basic Medical Officers’ Course is completed out of residency, while the Advanced Medical Officers’ Course is completed if they become a Base/Wing Surgeon.Footnote 26 However, Medical Officers and Base/Wing Surgeons who completed these courses before the DQ&P Review and Investigation section was stood up in 2021, would not have attended these presentations. Therefore, they may have limited or no knowledge of the process, especially when there is no formal recurring training. None of the Base/Wing Surgeons or Dental Detachment Commanders interviewed were aware of DQ&P’s guidelines.Footnote 27 The manager of CFHS Investigation, within DQ&P, indicated that they provided their contact information to all CFHS centres for any questions or guidance related to health care complaints.Footnote 28

The Commander CF H Svcs Gp publishes weekly Communiques to promulgate formal communication to lower-level Commanders and Units and has bi-monthly meetings with sub-ordinate Commanders and National Level Units.Footnote 29 Despite this, there is a lack of communication between CF H Svcs Gp and CFHS centres about how to address health care complaints.Footnote 30 This is a barrier to improvements.

"We do so many things and it would be nice to have a mini booklet including this [process] because we do deal with complaints. And it’s probably not standardized across the country how we’re each dealing with things. I think our personalities, our experience, we just deal with things as we think."

—Base/Wing Surgeon

"It would be nice for us to have feedback and to know what we could do better or could have done better to appease the member at the lower level."

—Base/Wing Surgeon

Both the DQ&P and the CFHS J1 (the individual responsible for personnel policies, human resources and support) reported that Base/Wing Surgeons have a high turnover and typically remain in the position for a maximum of two years. DQ&P added that this can lead to barriers in communication between Base/Wing Surgeons and CF H Svcs Gp, including who within CF H Svcs Gp they can contact for guidance and complaints.

The Health Services Policy and Direction intranet page does not offer guidance to CFHS staff on how to address complaints, including when and how to escalate matters to DQ&P.Footnote 31

CAF members

Since February 2022, CAF members are encouraged to give feedback on the medical and dental care received through the Patient Care Feedback Tool. This is a quality improvement tool, informed by the direct input of patients. However, the survey clearly states that members should not use it to lodge a formal complaint. To submit a complaint, members must contact the staff at their CFHS centres.Footnote 32

CFHS centres communicate information on how to submit a complaint through pamphlets and posters displayed in the centres, and verbally from medical and dental staff. However, only 4 of the 33 CFHS centres also advertise it on their website.Footnote 33

As such, the information and the method to process health care complaints is different across Bases and Wings, making it difficult for members to navigate. Also, the Health Services Policy and Direction intranet page has no guidance on how to address medical and dental complaints. Five of 13 interviewed CFHS authorities mentioned that the lack of knowledge on how to submit a complaint could be a barrier for members.

Additionally, no information is available about what members need to include in their complaint such as, how much personal medical information to disclose, who will review it, how long it will take to resolve, and what resolution they can expect. This may deter members from submitting their complaint. As well, two interviewees expressed that due to the lack of information and experience, members do not always submit a well-articulated complaint. Therefore, it can be difficult for Base/Wing Surgeons to understand what the member wants as a resolution.Footnote 34

During our interviews, we heard about other possible barriers members may face: four Base/Wing Surgeon and Dental Detachment Commanders mentioned that members of lower ranks may feel more uncomfortable to submit a complaint and fear repercussions than those of a higher rank. Two others mentioned that members may perceive submitting a complaint as negative, may have concerns about confidentiality or worry that nothing will be done to resolve the issue. The following was also mentioned as possible barriers:

- the positional email boxes that receive complaints are not secure, and members cannot send encrypted emails;

- members may perceive that CFHS staff will protect each other from complaints;

- members do not advocate for themselves or come forward when they feel their concerns are not being heard; and

- members may hesitate to submit a complaint in their first official language if it is not widely spoken in their location, and they may also feel they cannot adequately express their concern in their second official language.

Addressing complaints at local CFHS centres is perceived as efficient and effective

Of the eight Base/Wing Surgeons and Dental Detachment Commanders we interviewed seven felt that addressing complaints at the local level is effective and efficient. When they become aware of the issue, they can quickly take action to find a resolution, and mitigate similar issues from re-occurring. They also stated that they can resolve most complaints in a timely manner, which is critical when a complaint is related to a member's health needs. Additionally, CFHS health staff involve the members in the discussion to find a resolution appropriate for their situation.

Of those seven, two added that having a more standardized process across CFHS centres would help ensure consistent handling of health care complaints throughout the CAF.

"When we go to a higher level, we rarely get feedback. The feedback comes one or two years later when they change a policy, but it doesn’t come quickly enough to help at the clinic level."

—Base/Wing Surgeon

According to our interviews with CF H Svcs Gp, Base/Wing Surgeons and Dental Detachment Commanders, CFHS centres do not typically have fully dedicated human resources to address health care complaints in CFHS centres. CFHS centre staff receive and address complaints as a secondary duty and sometimes without training or guidance on how to investigate a complaint.Footnote 35 As most health care complaints can be addressed by CFHS centres, this can cause an administrative burden on staff as they may not be equipped or supported to manage the workload.

"I get at least multiple complaints per week, and it takes time to do the review to make a proper decision, it takes time to answer. Just the burden it brings."

—Base/Wing Surgeon

Impacts

The combination of not having a standardized health care complaint process, the absence of information, and the high turnover of medical staff limits the CFHS staff's awareness of what they need to do when they receive complaints. This also exacerbates the inconsistency in which CFHS staff address health care complaints and raises concerns of inequity and fairness for members submitting a health care complaint. This may deter members from submitting a complaint.

In addition to facing resourcing challenges, the administrative burden on medical and dental staff to analyze and address health care complaints as a secondary duty and without clear guidance increases their workload and can negatively impact their wellbeing.

Ongoing CAF initiatives

The DQ&P staffed a position in January 2024 on a 90-day contract to develop a CFHS Instruction on health care complaints, which will also be applicable to the local level. The CFHS Instruction will detail which complaints should be escalated to a higher level or addressed locally and will include defined timelines for complaint management. The DQ&P noted that CFHS has been working on this instruction for the past several years but has been unable to accomplish it due to workload demand. Once the CFHS Instruction is approved and implemented, the DQ&P will develop aide-memoires as a resource guide for local CFHS centre personnel.

Once implemented, the CFHS instruction and aide-memoires should:

- address the lack of standardization of the health care complaint process,

- reduce inconsistences and unfairness with addressing members' health care complaints, and

- help increase awareness of the process for CFHS staff and members.Footnote 36

The DQ&P anticipates a draft of the CFHS Instruction ready for further approval by 1 May 2024. No target implementation date was provided.

Note: All policy development and updates undergo a Gender Based Analysis Plus analysis.Footnote 37

Observation 1: Resource shortage

As reported in our 2023 "Hidden Battles" report, CFHS is experiencing resource shortages that mirror the challenges faced by provincial/territorial health care systems. When confronted with time and resource constraints, the duty of care takes precedence over administrative processes, including processing health care complaints.Footnote 38

When CFHS staff promptly resolve a member's complaint, it can help maintain and increase the overall wellness and confidence members have in their health care system.

Finding 2: Members often use the Canadian Armed Forces grievance process due to the lack of a formal CAF health care complaint process.

According to DAOD 2017-1, Military Grievance Process, members can submit a grievance for their health care related concern after they tried to resolve the concern with their CAF health care provider. Members have a statutory right to submit a grievance. However, a grievance is not the most efficient process to remedy health care complaints.

Grievance process

When we conducted this investigation, this was the grievance process in place: members who want to grieve a health care related issue, like any other grievance, must submit it to their Commanding Officer (although this superior is not part of their medical health care team). The Commanding Officer then forwards the grievance to the Canadian Forces Grievance Authority (CFGA), which subsequently sends it to the Surgeon General as the Initial Authority. The analysis is done by the DQ&P Review and Investigation section and once it is reviewed and signed by the Surgeon General, it is forwarded through the Grievance Officer within CFHS to the CFGA. The Grievance Authority cannot respond directly to the member, they must adhere to the grievance process, whereby the response is routed back to the CFGA, the Commanding Officer, and finally to the member.Footnote 39 However, the CFHS J1 (individual responsible for personnel policies, human resources and support) noted that the analysts reviewing the grievance on behalf of the Surgeon General engages with the grievor. It is important to note that the current grievance process is undergoing a transformation that began with the 5 February 2024 introduction of the digital grievance form.Footnote 40 As a result, the grievance process may not remain the same going forward.Footnote 41

"There are often opportunities for informal resolution and education on what the policy states for members. Sometimes grievances are withdrawn based on provisions on information due to direct communication between the analyst and the grievor or through the synopsis letter. They are responsible for ensuring procedural fairness and that the process is fair and transparent until the decision reaches the grievor."

—CFHS J1 (the individual responsible for personnel policies, human resources and support)

As per the National Defence Act, "The Chief of the Defence Staff is the Final Authority in the grievance process and shall deal with all matters as informally and expeditiously as the circumstances and the considerations of fairness permit."Footnote 42 However, "no officer who is not a medical officer shall exercise command over a medical officer in respect of his treatment of a patient."Footnote 43 This means that if the Chief of the Defence Staff finds that a member was aggrieved and that a particular medical treatment is "warranted," for example, they do not have the authority to order a medical officer to provide that treatment. The Surgeon General, who is the Initial Authority for health-related grievances, stated that they face a particular challenge "if members are not happy with my response, it needs to go to the Chief of Defence Staff for FA, who has no background or authority to deliver the health care program […] I am a bit challenged from a governance perspective, to have somebody outside of the clinical world to make decisions on grievances that are health related."Footnote 44

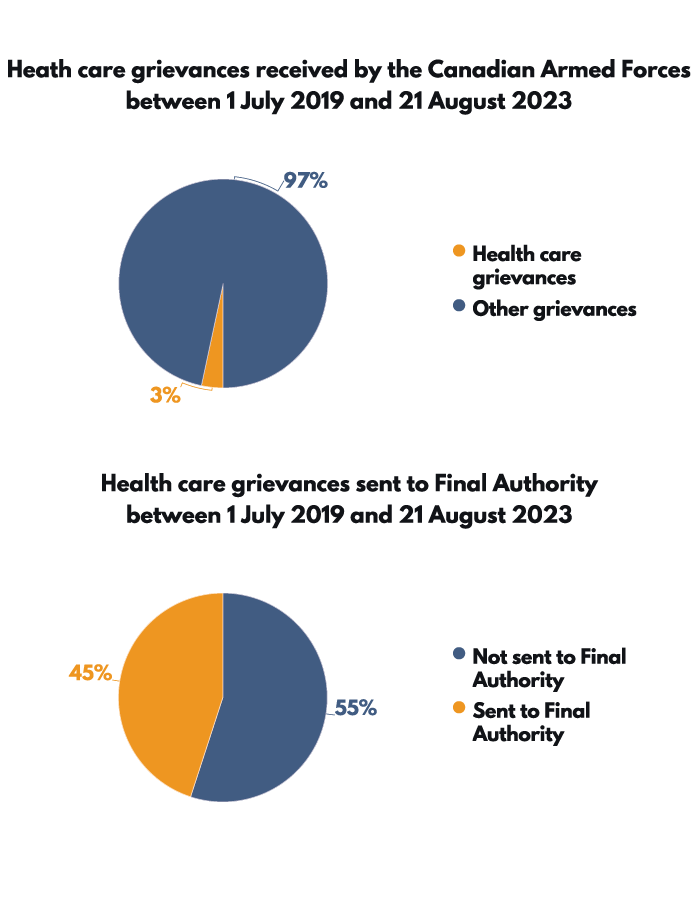

Figure 2: Health care grievances between 1 July 2019 and 21 August 2023

Between 1 July 2019 and 21 August 2023, the CAF received 160 (3 percent) grievances related to health care and of those files, 72 (45 percent) went to the Final Authority level. Footnote 45

Figure 2: Text version

Health care grievances received by the Canadian Armed Forces between 1 July 2019 and 21 August 2023

- Health care grievances: 3%

- Other grievances: 97%

Health care grievances sent to Final Authority between 1 July 2019 and 21 August 2023

- Sent to Final Authority: 45%

- Not sent to Final Authority: 55%

Eight of the 15 combined local CFHS and CF H Svcs Gp authorities interviewed identified the grievance process as the only formal CAF process to submit a health care complaint.Footnote 46 This means that members may be directed to submit their health care complaint formally through the grievance process. Additionally, members may submit a grievance because they are mostly only aware of the grievance process. It also fills the gap for the lack of a formal health care complaints process.Footnote 47 Members may also decide to submit a grievance because "[they] believe that the grievance process is their only option to voice their concerns."Footnote 48

Limits of the grievance process to address health care complaints

According to the Surgeon General and DQ&P, members who submit their health care complaint through the CAF grievance process do not benefit from being involved in the discussion to find a resolution, as would be the case if they submitted their complaint to CFHS staff.

If a member submits a complaint to CFHS staff, they will usually discuss the issue with the member to find a resolution that is personalized and to the member’s satisfaction, as much as possible.Footnote 49 If the member or medical/dental staff handling their complaint escalates the complaint to the CF H Svcs Gp , DQ&P will discuss the issue directly with the member to find a resolution.Footnote 50 The way CFHS address health care complaints is much less complex and has a more collaborative approach that focuses on the member’s issue and follows the Person-Partnered Care approach. Footnote 51 The Surgeon General and the Chief Dental Officer mentioned that the grievance process may not be easily accessible for all members, as some members may face greater difficulty navigating the grievance process. Occupations, workloads and work environment may also limit the time and computer access of members to submit a grievance.

Additionally, some health care complaints are not appropriate for the grievance process. Of the 66 health care complaints DQ&P received between August 2021 and October 2023, 12 percent were grievance submissions. However, according to DQ&P, most of these grievances should have been addressed through CFHS centres and not the grievance process. This is because most health care grievances are not related to a decision that has been made, which is one of the conditions of a grievance; that they are related to an administrative decision, act, or omission and where no other process for redress exists.Footnote 52

Both the Surgeon General and D Med Pol noted that CFHS is better suited to address health-related complaints outside the grievance process. In fact, the Surgeon General stated, "[when] I sign my [Initial Authority] letter for a response to a grievance, probably one [response] out of two, I refer a member back to the complaint management process because I strongly believe that this will better address their challenges than the black and white grievance process." As such, addressing health care complaints at the local level better aligns with the Person-Partnered Care framework, which "formally recognize[s] patients as being full partners in their care" and emphasizes collaboration with and involvement of the patients to improve health services.Footnote 53

Observation 2: Multiple avenues to submit a grievance

The lack of information about and standardization of how the CAF addresses health care complaints causes confusion and drives members to submit complaints through multiple or incorrect avenues.

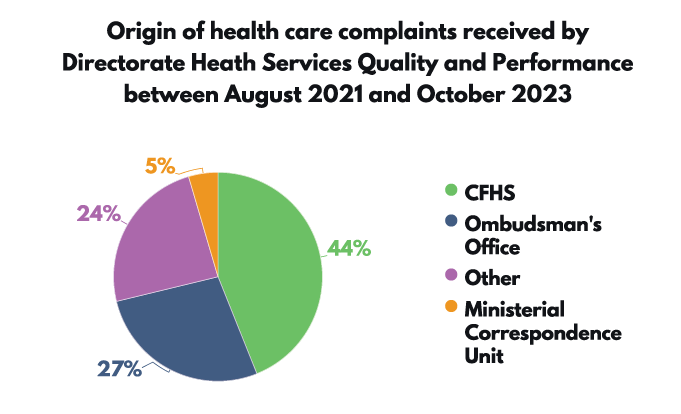

Figure 3: Origin of health care complaints between August 2021 and October 2023

Between August 2021 and October 2023, DQ&P received 66 complaint files.Footnote 54 Of those files, CFHS generated 42 percent, the Ombudsman’s office transferred 27 percent and five percent came from the Ministerial Correspondence Unit.Footnote 55

Figure 3: Text version

Health care grievances received by the Canadian Armed Forces between 1 July 2019 and 21 August 2023

- Health care grievances: 3%

- Other grievances: 97%

Health care grievances sent to Final Authority between 1 July 2019 and 21 August 2023

- Sent to Final Authority: 45%

- Not sent to Final Authority: 55%

Less than half of the complaints DQ&P received came through CFHS centres, which indicates that CFHS may not be sending most complaints to DQ&P, and members are directing their complaints through different channels. The CFHS staff we interviewed also shared these observations.

Observation 3: Personal medical information in grievances

D Med Pol indicated that most members and CAF leadership believe members' grievance submissions must include personal medical information. This unnecessarily exposes the members' personal and medical information to the multiple people involved in the process. D Med Pol stated, "there is an option to put minimal information saying, 'this is related to medical care' and then to provide that supplemental information later only to the medical side."

Impacts

Members submit health care grievances to their Commanding Officer, who is also their superior. This dynamic may deter members from submitting a grievance, especially when they believe they need to include personal medical information in their submission.

The lack of a formal CAF health care complaint process may lead to more grievance submissions related to health care. This increases the number of files that grievance authorities need to address in an already burdened process, when CFHS may be able to address their concerns more effectively outside the grievance process. Additionally, the CAF does not track the number of members with health care issues who choose not to submit a complaint because they assume that a grievance is their only option.

The grievance process does not have a Person-Partnered Care approach which focuses on the member’s issues and needs; it is an administrative process. This often results in longer resolution times compared to when members seek assistance from CFHS staff. This prolonged and stressful process can negatively affect members, especially those whose untreated or misdiagnosed conditions may worsen over time.

Duplication of effort can be a concern when the Initial Authority refers the member back to their local CFHS centre in their grievance response. Members unsatisfied with the answer from the Initial Authority would need to escalate the grievance to the Final Authority, causing more frustration and delays in resolving the issue.

Base/Wing Surgeons and Dental Detachment Commanders can improve the quality of CAF health care when members submit a complaint through health services at the local level.Footnote 56

Ongoing CAF initiatives

As mentioned in Finding 1, the implementation of a health care complaint instruction and a formal health care complaint process will help reduce CAF grievance submissions related to health care and direct members to their local CFHS centre.

Finding 3: A centralized tracking system does not exist for health care complaints.

Our interviews with local and national CFHS authorities noted a lack of a centralized tracking system to register and track complaints. While complaints are tracked at the national level, once received by the Review and Investigation section, the local centres may not be tracking the complaints they receive.

The DQ&P estimates that they only have visibility on five percent of all the health care complaints submitted throughout the CAF.

"We might not even be aware of a lot of the complaints because they might be addressed informally."

—Director of Quality and Performance

Impact

The lack of a tracking system for health care complaints prevents the CAF from identifying local and national gaps and systemic issues. CFHS may be unaware of issues that exist and that will continue to arise or worsen because they remain unaddressed.

Ongoing CAF initiatives

As stated in Finding 1, the DQ&P is developing a CFHS Instruction for a standardized health care complaint process at both the local and national level. The DQ&P is also developing an interim solution to fill the gap of a national complaints process utilizing currently available Information Technology platforms until a permanent solution can be identified and procured.

This interim solution may:

- help track complaints locally and communicate issues to CF H Svcs Gp,

- identify gaps and systemic issues at CFHS centres, and

- help CF H Svcs Gp identify gaps and systemic issues across Canada.

Implementing a centralized health care complaint system would ensure consistent and accurate tracking of complaints. It would also standardize complaint submissions and give better accessibility for members who do not reside close to a CFHS centre.

Finding 1: Health care complaints are addressed inconsistently across Canadian Forces Health Services centres due to the lack of a formal health care complaint process.

Finding 2: Members often use the Canadian Armed Forces grievance process due to the lack of a formal CAF health care complaint process.

Recommendation 1: By January 2025 that the Canadian Armed Forces dedicate resources to implement a Canadian Forces Health Services Instruction on the administration of Canadian Armed Forces health care complaints, and include:

- standard operating procedures to guide Canadian Forces Health Services centres in the implementation of the Instruction.

- a training plan for Canadian Forces Health Services Commanding Officers and others that engage in the complaints process once the Instruction is developed.

- a communication plan to ensure the new instructions are communicated to members and made available on the Internet and Intranet.

Finding 3: A centralized tracking system does not exist for health care complaints.

Recommendation 2: By May 2026 that the Canadian Armed Forces dedicate resources to develop a centralized tracking system for health care complaints submitted across Canadian Forces Health Services centres and to Canadian Forces Health Services Group directly. This would include implementing a formalized Lessons Learned Framework for continuous improvements, detailing trends in health care complaints and collecting disaggregated data.

Conclusion

Our investigation focused on how the CAF handles health care complaints. Our objective was to identify instances of unfairness and inequity resulting from the lack of a formal health care (medical and dental) complaint process for members and to identify some of the impacts of this on CAF members. We found that the lack of a formal process causes inconsistencies in addressing health care complaints across CFHS centres. Although some CFHS centres developed their own Standard Operating Procedures, there is no overall CFHS Instruction that governs the administration of health care complaints.

Our investigation also revealed that many barriers prevent the CFHS from creating an overall Instruction. For instance, CFHS is experiencing workload demands that mirror the challenges faced by the provincial and territorial health care systems.

Since no formal Instruction exists, members often resort to the grievance process. This can cause delays, inequitable outcomes and members do not benefit from Person-Partnered Care. Additionally, the absence of a centralized tracking system for health care complaints prevents the CAF from identifying gaps and systemic issues, hindering them from making improvements.

The investigation uncovered three findings:

- Health care complaints are addressed inconsistently across CFHS centres due to the lack of a formal health care complaint process. Each CFHS centre has different avenues for members to submit a complaint and has different processes for addressing complaints, raising concerns about fairness and equity.

- Members often use the CAF grievance process due to the lack of formal CAF health care complaint process. Eight of the 15 combined local CFHS and CF H Svcs Gp authorities interviewed identified the grievance process as the only formal CAF process to submit a health care complaint. However, the grievance process causes delays and does not follow the Person-Partnered Care approach.

- A centralized tracking system does not exist for health care complaints. The DQ&P only has visibility on approximately five percent of complaints. The inability to track complaints prevents the organization from identifying gaps, systemic issues, and general areas for improvement at CF H Svcs Gp and CFHS centres.

As stated in the Standing Committee on National Defence’s report on CAF health care and transition services, "The CAF’s Acting Chief of Military Personnel and Acting Commander of Military Personnel Command referred to the long-term health and wellness of CAF members, as well as the provision of high-quality health care to them, as priorities."Footnote 57 Consequently, the DND and the CAF should prioritize the resolution of health care complaints from members who express dissatisfaction with the quality or type of care they receive.

Our recommendations, if implemented, will bring lasting improvements for the wellness of CAF members. Formalizing and communicating the process to address health care complaints is the basis for fair and more efficient resolution. This goes hand in hand with the Person-Partnered Care approach, which positively contributes to operational readiness and the wellbeing of CAF members. Additionally, it will allow the CAF to implement improvements to their health care complaint process, which have been ongoing for several years.

Appendix I: Letter to the Minister of National Defence

02 May 2024

The Honourable Bill Blair, PC, COM, MP

Minister of National Defence

Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces

National Defence Headquarters

101 Colonel By Drive,

13th Floor, North Tower

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K2

Minister Blair:

Please find enclosed my report, Defending Wellness: A Systemic Investigation of the Canadian Armed Forces’ Health Care Complaint Process.

This report makes two evidence-based recommendations. If accepted and implemented, these recommendations will bring long-lasting and positive changes for CAF members. Additionally, I believe that the timely implementation of my recommendations will assist the CAF’s efforts to fulfill its commitment made to the Defence community in Strong, Secure, Engaged, Our North Strong and Free, and the Total Health and Wellness Strategy.

This report is submitted to you pursuant to paragraph 38(1)(b) of the Ministerial Directives in respect to the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. As is standard practice, my office will publish the report no sooner than 28 days from the date of this letter. We would appreciate your response before publication so that it may be included in the final report. As done in the past, I would be pleased to offer your staff a briefing on the report prior to its publication.

I look forward to your response to our recommendations.

Sincerely,

Gregory A. Lick

Ombudsman

Appendix II: Glossary

Base/Wing Surgeon: is the clinical authority (similar to a chief medical officer in civilian clinics) and is responsible for all things clinical and has authority to approve clinical spending. They work in collaboration with the Health Services Clinic's Commanding Officer to ensure patient care is delivered safely and efficiently.

CFHS centres: the CFHS centres encompass both medical and dental centres whose role is to provide health services to CAF members and eligible personnel to optimize their health.Footnote 58

CFHS staff: an individual or group directly involved with the provision of health care to members, whether through medical and dental care, or counselling. This includes personnel within Canadian Forces Health Services (medical and dental staff), as well personnel responsible for health care related policies.

Complaint: when the member believes there is an issue with the services received and formally submits a complaint.

Concern: when a member is dissatisfied with the services received, which can be resolved through early and informal discussions with the health care service provider to quickly address the issue.

Final Authority: the final level of review in the CAF grievance process. If the CAF member disagrees with the decision of the Initial Authority, they have the right to have the matter reviewed by the Chief of Defence Staff or delegate as the Final Authority.Footnote 59

Formal processes: have written policies or other guidance, which include service standards, standard operating procedures, tracking, and communication.

Grievance: complaint submitted by an officer or non-commissioned member who has been aggrieved by any decision, act, or omission in the administration of the affairs of the Canadian Forces as no other redress process under the National Defence Act can resolve it.Footnote 60

Impact: in the context of this investigation, impact refers to the negative effect of the lack of a formal health care complaint process.

Informal processes: have no written policies or guidance.

Initial Authority: the first level of review in the CAF redress of grievance process.Footnote 61

Standardization: is to conform with a standard, especially to assure consistency and regularity across the organization.

Surgeon General: has two roles, one as the Director General of Health Services and the second as Commander of the Canadian Forces Health Services Group.

Appendix III: Methodology

Our investigation focussed on concerns within the current Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) health care complaint process and subsequential impacts on members and the organization itself. This investigation covered the period from July 2021, when the Directorate Health Services Quality and Performance (DQ&P) Review and Investigation section was stood up, to February 2024. Our goal for this investigation was to understand the following:

- Barriers CAF members face with regards to the process to address health care complaints.

- Instances of unfairness and inequity that CAF members face with the current process to address health care complaints and its impact on CAF members and the organization.

- Gaps in the processing of health care complaint as observed by CAF leadership.

We examined the process of addressing health care complaints related to the quality and type of care received. This investigation did not examine how the CAF health care complaint process addresses complaints that dispute a policy, including concerns related to the Spectrum of CareFootnote 62 and entitlements to care. Additionally, it did not evaluate the effectiveness or quality of the health care provided to members, such as concerns of malpractice, and did not assess the roles and responsibilities of Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) staff. Resources to address health care concerns, including professional conduct, will be available on our website under Educational Information.

Investigative plan

This investigation used a mixed-method approach, which included qualitative and quantitative data, as well as analysis by multiple investigators.

Documentation research and literature review

- CAF Canada.ca websites

- CAF directives and presentations

- Canada’s Defence Policy—Strong, Secure, Engaged; Our North Strong and Free

- Canadian Forces Grievance Manual

- Canadian Forces Health Services Instructions

- Canadian Military Justice website

- Defence Administrative Orders and Directives

- Emails, presentations, transcripts, data, and other formal/informal and internal written directives provided by DND/CAF authorities

- Health care complaint data from Director Quality and Performance

- Health Services Policy and Direction intranet site

- Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health website

- Military Grievance External Review Committee website and case studies

- National Defence Act

- Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces

- Related grievances data breakdown from Chief Professional Conduct Culture

- Reports, guides, and policy manuals

- Standard Operating Procedures

- The Assisting Member Military Grievance Course

- Total Health and Wellness Strategy

Ombudsman Office

- Complaint files from internal protected B database

- Education and Research Products

- Ombudsman letters

- Past studies and reports

Interviews and Consultations:

Initial consultations with DND/CAF authorities took place in the spring of 2023.

DND/CAF authorities were invited via email to participate in our interviews. Everyone that was contacted agreed to participate. We recognize that the experiences and opinions expressed may not necessarily represent the views of all CAF authorities.

We consulted with various groups between October 2023 and February 2024, and conducted a total of 15 interviews between October and November 2023, including 7 individuals occupying senior CAF leadership roles.

- Chief of Defence Staff (CDS)

- Military Grievances External Review Committee (MGERC)

- Chief of Professional Conduct and Culture/Associate ADM (CPCC)

- Chief of Military Personnel (CMP)

- Surgeon General, as DGHS and Commander CF H Svcs Gp

- Director Quality and Performance (DQ&P)

- Director Medical Policy (D Med Pol)

- Chief Dental Officer

- CO 1 Dental Unit

We also interviewed 5 Base/Wing Surgeons and 3 Dental Detachment Commanders, taking into consideration the different centres’ size, language, geographical location, and element of most patients CFHS Centres provide care to.

Potential bias

We recognize that biases may exist when investigating the health care complaint processes. Some of those biases may include selection/sampling bias, cognitive bias, information bias, and interviewer bias. Our investigative team used mitigation strategies to ensure that the information presented is evidence-based. This included:

- Employing a mixed method approach systematically in the collection and analysis of qualitative and quantitative data

- Acquiring quantitative data from various sources, using multiple investigators to collect and analyze qualitative data and conduct interviews;

- In written correspondence and interviews with CAF key leadership interviewed, we asked "If you feel we should also speak with others in your organization, please provide their contact details."

- Selection and sampling expanded to acquire information from various perspectives on the subject, irrespective of rank. This included various DND/CAF authorities and care providers (policy, administrative and medical).

- Employing multiple multi-level revisions and validation measures to test for evidentiary rigour in the collection, analysis, and reporting of information; and acquiring bias awareness training for the investigative team.

Note: The complaints brought forward to our office by CAF members from July 2021 to February 2024 provided the information on the issues and their impacts reported in this investigation.

Figure 4: Text Version

Organizational Structure – UIC 2203

Chief of Health Services / Surgeon General

(Currently Director General Health Services)

Major-General

Reporting to Chief of Health Services / Surgeon General

- UIC 3304

Canadian Forces Health Services Group Commander

Brigadier-General

- Director General Health Services (Clinical)

Brigadier-General

- Health Services Secretariat

Colonel

- Director Health Services Strategy

Colonel

- Executive Director Health Services (Corporate)

EX 02

- Director Quality and Performance

MD MOF 04

- Group Chief Warrant Officer

Reporting to Director General Health Services (Clinical)

- Royal Canadian Navy Surgeon

Colonel

- Royal Canadian Air Force Surgeon

Colonel

- Canadian Army Surgeon

Colonel

- Chief Dental Officer

Assignment

- Public Affairs

MD MOF 04

- Director Mental Health

Colonel

- Director Force Health Protection

Colonel

- Director Women & Diversity Health

- Director Medical Policy

Colonel

- Director Dental Services

Colonel

- Chief Of Staff Health Services (Clinical)

Colonel- Senior Staff Officer Director General Health Services (Clinical)

Lieutenant-Colonel - Royal Canadian Dental Corps

Chief Warrant Officer - Royal Canadian Medical Services

Chief Warrant Officer

- Senior Staff Officer Director General Health Services (Clinical)

Reporting to Executive Director Health Services (Corporate)

- Chief of Staff Health Services (Corporate)

Colonel- Strategic Human Resources Programs & Plans

AS 07 - Senior Staff Officer Executive Director Health Services (Corporate)

Lieutenant-Colonel

- Strategic Human Resources Programs & Plans

- Canadian Forces Health Services Comptroller

FI 04

Reporting to Director Quality and Performance

- Clinical Audit and Utilization

- Quality & Patient Safety

- Evaluation

- Investigation

- Performance Measurement

- Knowledge Transfer