Evaluation of the Emergency Preparedness and Response Program (2019-2020 to 2023-2024)

Download in PDF format

(1.01 MB, 71 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2025-06-18

Cat.: HP5-262/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-77316-2

Pub.: 250055

October 2024

Prepared by the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Public Health Agency of Canada

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Overview and program description

- Evaluation scope and approach

- Findings

- Detection and reporting

- Emergency response and mobilization

- Collaboration, coordination and governance

- Sustained EPR system in Canada

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix A: Financial information

- Appendix B: Evaluation description

- Appendix C: Exercises by activation centre

- Appendix D: Emergency management maturity model

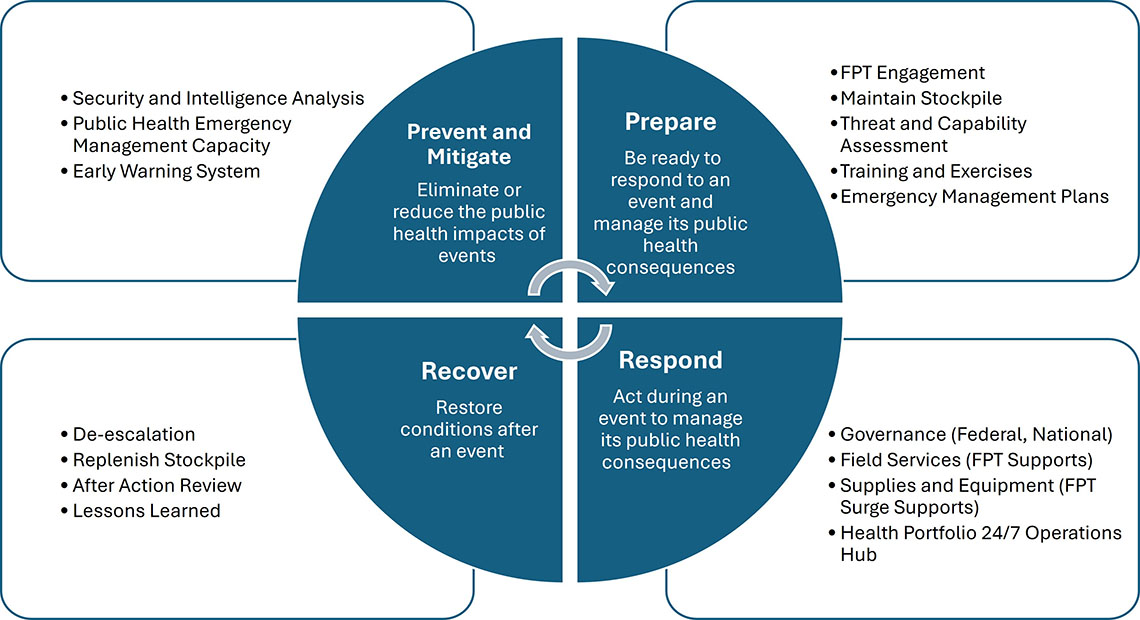

- Appendix E: The emergency management cycle

- Appendix F: Program performance measurement

- Endnotes

List of acronyms

- AERO

- All-Events Response Operations

- AARs

- After Action Reviews

- CEP

- Centre for Emergency Preparedness

- CER

- Centre for Emergency Response

- CFEP

- Canadian Field Epidemiologist Program

- CMP

- Comprehensive Management Plan

- CPHS

- Canadian Public Health Service

- DG

- Director General

- DUA

- Detect, Understand, Act

- EM

- emergency management

- EMEC

- Emergency Management Executive Committee

- EPR

- Emergency Preparedness and Response

- F/P/T

- federal, provincial, and territorial

- GOARN

- Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network

- GOC

- Government Operations Centre

- GPHIN

- Global Public Health Intelligence Network

- HC

- Health Canada

- HECO

- Health Emergency Coordination Office

- HP

- Health Portfolio

- HP EPC

- Health Portfolio Emergency Preparedness Committee

- HP ERP

- Health Portfolio Emergency Response Plan

- HPOC

- Health Portfolio Operation Centre

- IHR

- International Health Regulations

- IMS

- Incident Management System

- LAC

- Logistics Advisory Committee

- NESS

- National Emergency Strategic Stockpile

- NMLB

- National Microbiology Laboratory Branch

- NMLB-EOC

- National Microbiology Laboratory Branch's Emergency Operations Centre

- OAG

- Office of Auditor General

- OFMAR

- Operational Framework for Mutual Aid Requests

- OGD

- other government department

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PHEM

- Public Health Emergency Management

- PHEM-WG

- Public Health Emergency Management Working Group

- PHN

- Pan-Canadian Public Health Network

- P/T

- provincial and territorial

- P/Ts

- provinces and territories

- RECC

- Regional Emergency Coordination Centres

- RFA

- Requests for Assistance

- ROEMB

- Regulatory, Operations and Emergency Management Branch

- RSTA

- Response Support and Technical Assistance

- SAC

- Special Advisory Committee

- SGBA+

- Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis Plus

- SIIRA

- Surveillance, Integrated Insights and Risk Assessment

- SOPs

- Standard Operating Procedures

- SPAR

- State Parties Self-Assessment

- VP

- Vice-President

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Executive summary

Program description

The Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) program is responsible for strengthening Canada's capacity to prevent, mitigate, prepare for, and respond to public health events and emergencies, as well as mass gatherings and high-profile events.

The Regulatory, Operations and Emergency Management Branch (ROEMB) is PHAC's centre of expertise for emergency management functions, providing response coordination for unplanned or intentional emergency events, as well as planned mass gatherings and high-visibility events for PHAC and Health Canada (HC), referred to as the Health Portfolio (HP) in this report. ROEMB provides the HP with shared services in emergency management governance, emergency management plans, operations centres, field mobilizations, as well as continuous improvement through training, exercises, and identification of lessons learned. Not within of the shared services partnership, ROEMB also maintains programming key to event detection and information sharing through the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) and the International Health Regulations (IHR) as the national focal point for Canada. It also manage the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS) which provides medical assets to provinces and territories when requested. ROEMB is also responsible for the Regional Emergency Preparedness and Response Units, which are coordinating response to an event in a particular region.

The National Microbiology Laboratory Branch (NMLB) also contributes to PHAC's emergency preparedness and response activities by maintaining an Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). The NMLB-EOC is PHAC's scientific point of coordination for emergency response and day-to-day communications on infectious diseases from a laboratory perspective. The NMLB-EOC works with the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network to coordinate the national public health laboratory response. The NMLB also provides scientific and mobile laboratory support for field investigations aimed at controlling outbreaks and potential threats domestically and in support of international partners.

Evaluation scope

This evaluation assessed the EPR program's activities from 2019-2020 to 2023-2024. It examined the achievement of intended results, and the efficiency of the program. The evaluation focused on PHAC's EPR program activities, which are led by ROEMB. It also assessed NMLB-EOC activities.

Many other centres with technical expertise across PHAC and HC also have activities that relate to EPR. However, the technical expertise provided by these centres in support of EPR is not covered by this evaluation. Given the supporting roles of these partners, this evaluation focused on ROEMB's engagement, collaboration, and how it coordinates activities with these partners, rather than on specific partner activities.

Findings

The evaluation found that PHAC is better prepared to respond to public health events than it was five years ago. Plans and procedures have been updated, exercises have taken place, and PHAC-wide Public Health Emergency Management (PHEM) training was implemented, including one mandatory course. Time-limited funding has also improved public health intelligence capacity by enhancing the GPHIN and improving event detection through the widespread distribution of GPHIN Daily Reports. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic have also been integrated into PHAC's future pandemic preparedness, and many past audit and review recommendations have been implemented.

Collaboration and external governance with federal, provincial, and territorial (F/P/T) partners is also strong with respect to emergency response, though there could be more opportunities to engage in preparedness activities. At the same time, while emergency management (EM) governance at PHAC has improved, there are still challenges with information sharing across the HP at all levels, both during and outside of a response. This issue should be addressed in order to strengthen internal EM activity coordination, engage with the appropriate HP program areas, minimize duplication, cultivate an EM culture, and support business continuity. Collaboration with international partners was also strengthened during the evaluation period; however, challenges were reported with respect to the clarity of internal branch roles on international EM-related files.

Over the last five years, PHAC responded to many requests for supports and mobilized several Incident Management Systems (IMS) to coordinate the response to multiple public health events. However, given the length and breadth of the COVID-19 IMS, mobilizing staff for concurrent mobilizations and maintaining the surge capacity over time was challenging. Since the creation of HC's Health Emergency Coordination Office (HECO) in the fall of 2023, ROEMB has been working with it on a HP framework to help mobilize adequate personnel and sustain effective responses to more frequent and intense emergencies. This framework is essential to readiness and response, and its success hinges on PHAC's adoption of an EM culture highlighted by readiness, resilience, and commitment to collective response.

Funding associated with the COVID-19 response allowed the NESS to procure a substantial volume of medical assets, which has temporarily enhanced their capacity to deploy assets during public health emergencies or events so long as the assets remain within their usable life and do not expire. In a post-COVID-19 context, reviewing the NESS' mandate and its strategic priorities will also help prepare an efficient response in the future and improve alignment with F/P/T needs and holdings. Timely implementation of the NESS Comprehensive Management Plan, approved in May 2024, will be important in tracking that action items continue to address key findings and recommendations from past audits and evaluations.

As PHAC is moving towards stabilization of its resources through renewal, a prioritization of key areas in EM will have to occur to support continuous system improvement and sustainability, and align resources accordingly. The implementation of a cyclical approach to EM, which would include risk and capability assessments, training, regular exercises, a strong mobilization framework and recovery strategy, regular plan updates, and timely integration of lessons learned, is needed to support system sustainability.

Recommendations

The findings from this evaluation have resulted in the three recommendations listed below. There is no recommendation directed at the NESS given, that a comprehensive management plan was approved in May 2024, and is being implemented to address outstanding challenges, as recommended by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG)Footnote 1.

Recommendation 1: Implement the mobilization framework and improve the rostering system.

The over-reliance on the same individuals to be mobilized was identified as a significant challenge for mobilization and overall staff retention. Since March 2024, joint work has been underway with HC's HECO to update the mobilization framework, which has been a long-standing challenge identified in previous reviews. Given that the All-Events Response Operations (AERO) system is sunsetting, ROEMB should evaluate what data management and rostering IT tools are needed to be more efficient and effective.

Recommendation 2: Promote a mobilization culture and EM training within the Agency.

Mobilization culture, policies, and processes within the Agency are not sufficiently developed. Supporting emergency response mobilization is critical for the success of the mobilization framework, including providing time for training as well as a recovery period following mobilization. Also, while a Public Health Emergency Management course is now mandatory for all staff at PHAC, continuing education and training is also key to maintaining skills and an emergency management culture.

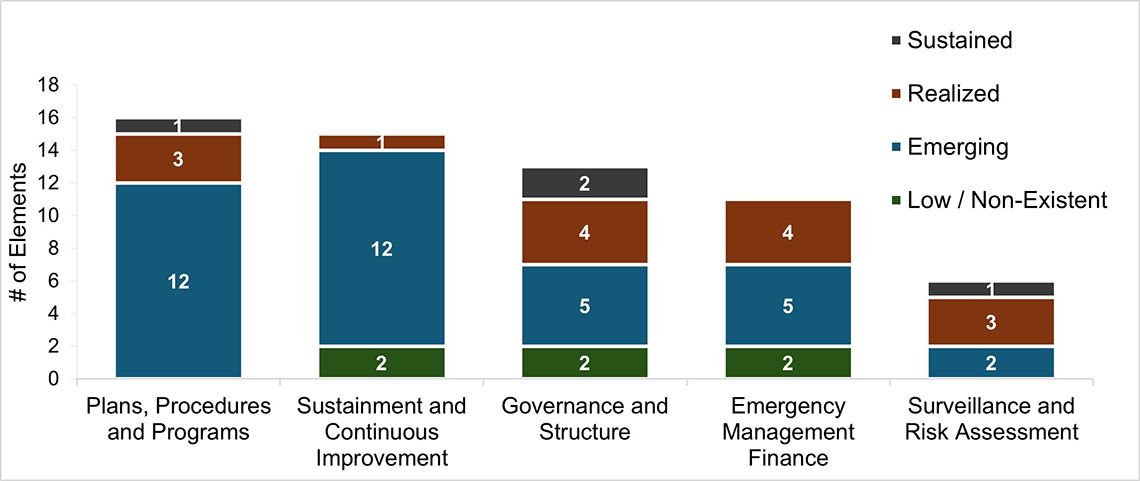

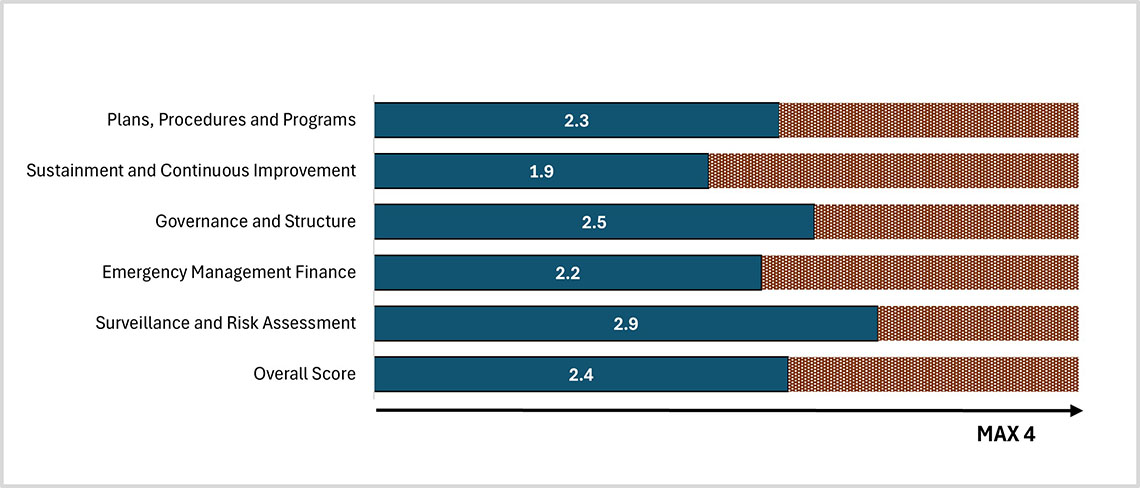

Recommendation 3: Ensure continued sustainability of the EM system by prioritizing and formalizing a cyclical approach to EM.

Significant investments have allowed the program to build an EM system that is stronger and more stable. It will be important to prioritize continued sustainability of this system through the full implementation of a cyclical approach to EM. Over the last five years, the flow of this cyclical approach to EM was slow moving, and at times stalled, due in part to an emphasis on emergency response activities. Going forward, the Agency should strive to implement all of the elements of the EM cycle, while ensuring these elements work together efficiently and coherently.

More specifically, ROEMB should work collaboratively with the various PHAC and HC centres of expertise towards sustaining emergency preparedness activities through the implementation of a robust risk and capability assessment program that would support exercise prioritization and decision making related to an all-hazards approach. Such a system should leverage existing risk assessment expertise across the HP and provide concrete direction on necessary revisions to EM plans, which, once implemented, could be re-tested via subsequent exercises and validated through lessons identified in event response After Action Reviews to address gaps. Since the winter of 2024, HECO has been engaging HC programs to support the risk and capability assessment work led by ROEMB.

Overview and program description

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of the Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) Activities.

Program profile

Preparing for and responding to emergencies is a shared responsibility among all three levels of government (federal, provincial and territorial, municipal), with contributions from non-governmental public health partners. The Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) program within PHAC is responsible for strengthening Canada's capacity to prevent, mitigate, prepare for, and respond to public health events and emergencies, as well as mass gatherings and high-profile events.

The Regulatory, Operations and Emergency Management Branch (ROEMB) is PHAC's centre of expertise for emergency management functions, providing response coordination for unplanned or intentional emergency events, as well as planned mass gatherings and high-visibility events for PHAC and Health Canada (HC), referred to as the Health Portfolio (HP) in this report. ROEMB provides the HP with shared services in emergency management governance, emergency management plans, operations centres, field mobilizations, as well as continuous improvement through training, exercises, and identification of lessons learned. In assuming its role, ROEMB works in collaboration with other PHAC and HC programs that have their own EPR responsibilities and activities, including HC's Health Emergency Coordination Office (HECO), which was established in the fall 2023.

ROEMB also fulfils Canada's domestic and international obligations to detect, prepare for, and respond to public health events, such as infectious and communicable disease outbreaks, pandemics, and bioterrorism, and coordinates responses to address the public health implications of natural hazards or human-caused disasters.

The National Microbiology Laboratory Branch (NMLB) contributes to PHAC's emergency preparedness and response activities by maintaining an Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). NMLB-EOC acts as the scientific point of coordination for emergency response and day-to-day communications in infectious diseases from a laboratory perspective.

Below is a description of activities undertaken by ROEMB and NMLB as part of this program.

Within ROEMB

- The Centre for Emergency Preparedness (CEP) applies an all-hazards, risk-based approach, in collaboration with HP partner programs, to establish resilient and adaptable emergency preparedness capabilities that aim to detect, mitigate, prepare for, and recover from domestic and global public health threats to protect the health and safety of Canadians.

- The Centre for Emergency Response (CER) is the HP lead for public health emergency response efforts. This includes providing a 24/7 single window for the HP, with an operations centre offering centralized reception and triage, and reporting and distribution of health information. CER is the HP link to emergency management (EM) partners, supports domestic and international mobilizations, and mobilizes the Incident Management System (IMS) to coordinate responses to specific public health emergencies.

- The Regional Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) Units are responsible for coordinating the HP response to an event in a particular region. This includes the following:

- providing situational awareness to the Health Portfolio Operations Centre (HPOC), program leads, and regional stakeholders;

- supporting HP programs in their regional response activities;

- tracking and supporting the needs of any HP resources that are deployed to the region; and

- briefing regional HP executives.

- When additional capacity is required to support the HP emergency response in the region, the Regional EPR Units use their respective Regional Emergency Coordination Centre(s) (RECCs), scaled to event needs, to respond as required.

- The National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS) program facilitates access to a range of medical countermeasures (MCMs), including life-saving drugs, medical supplies and equipment, and emergency social service supplies. It is intended to be leveraged as surge capacity to support provincial and territorial (P/T) responses to public health events and emergencies when their supplies are exhausted or not immediately available. It is also the sole provider of niche medical countermeasures required for rare public health emergencies, such as bioterrorism.

Within NMLB

- The NMLB-EOC works with the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network to coordinate the national public health laboratory response. The NMLB also provides scientific and mobile laboratory support for field investigations aimed at controlling outbreaks and potential threats domestically and in support of international partners.

Internal HP partners

While ROEMB is the centre of expertise for the HP's emergency management function, ROEMB will work with a range of HP centres of expertise, depending on the nature of the activities:

- Within PHAC, this includes the Infectious Diseases and Vaccination Programs Branch (IDVPB), the Data, Science and Foresight Branch (DSFB), and the Centre for Border and Travel Health and the Centre for Biosecurity within ROEMB.

- Within HC, this includes HECO and other programs within the Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch (HECSB), and the Health Products and Food Branch (HPFB).

- Within the shared services partnership this includes the Communications and Public Affairs Branch (CPAB), the Corporate Services Branch (CSB) and this Office of International Affairs (OIA).

Did you know? HECO was created in September 2023, within HC's Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch. HECO provides a departmental focal point, as well as strategic advice and coordination, for horizontal health emergency management policy, planning, integration, and governance across HC for all health emergency preparedness, response, and recovery activities. HECO works with HC programs, and with PHAC as the lead for emergency management for the HP, in order to fulfill its mandate.

This evaluation does not assess the activities performed by these various HP centres of expertise as they related to EPR activities. However, it does examine how ROEMB engages, collaborates, and coordinates activities with them.

Intended results

The EPR program plays an important role in PHAC's core responsibility of preparing for and responding to public health events and emergencies. In support of this responsibility, the EPR program aims to achieve the following:

Immediate outcomes

- Public health emergency preparedness is sustained;

- Public health events and emergencies are detected and reported on a timely basis; and

- Public health emergencies are responded to on a timely basis.

Intermediate outcome

- Public health emergency preparedness and response capacity is improved.

Ultimate outcome

- A sustained public health emergency preparedness and response system for Canada is in place.

Financial resources

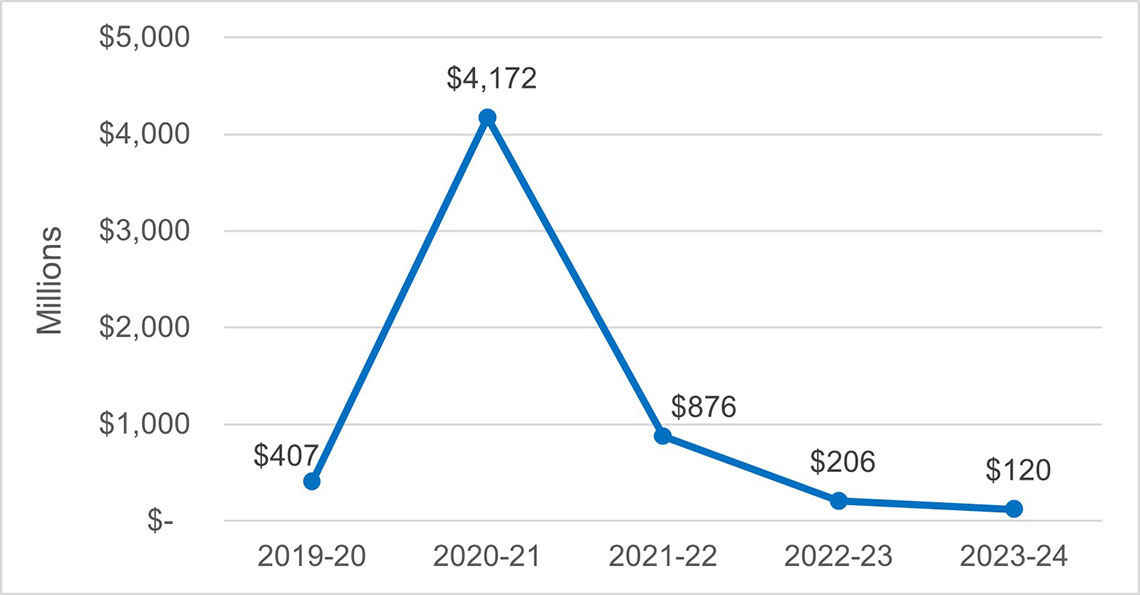

Table 1 presents the program's planned funding from 2019-20 to 2023-24. As the last quarter of 2019-20 marked the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the EPR program received time-limited COVID-19 funding, which is also identified in the table. Actual spending data is presented in Appendix A.

| Year | Planned funding for regular activities | Planned funding for COVID-19 response | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-2020 | $22,362,755 | n/a | $22,362,755 |

| 2020-2021 | $28,597,439 | $1,394,405,131 | $1,423,002,570 |

| 2021-2022 | $87,064,497 | $1,817,810,976 | $1,904,875,473 |

| 2022-2023 | $95,698,883 | $274,728,807 | $370,427,690 |

| 2023-2024 | $103,091,156 | $170,214,925 | $273,306,081 |

| Total | $336,814,030 | $3,657,159,839 | $3,993,974,869 |

|

Notes:

|

|||

Evaluation scope and approach

The purpose of this evaluation was to examine the EPR program's achievement of intended results, and the efficiency of its activities from 2019-2020 to 2023-2024.

Activities in scope

For ROEMB, the evaluation scope includes activities of the Centre for Emergency Preparedness (CEP), the Centre for Emergency Response (CER), the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS) and the Regional Emergency Preparedness and Response Units, as described in the previous section.

For NMLB, the scope includes activities of the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC), also as described in the previous section

Activities out of scope

Many other centres with technical expertise across HC and PHAC (and even within ROEMB, such as the Centre for Border and Travel Health and the Centre for Biosecurity), also have EPR activities that relate to public health. However, the technical expertise provided by these centres in support of the EPR program is not covered by this evaluation. The activities of these expert centres have been and will continue to be covered in separate evaluations.

Methodology

Data collection methods included a review of financial data, performance data and documents, as well as a comparative analysis, case studies, and key informant interviews with PHAC, other government departments (OGDs) and provincial and territorial (P/T) representatives. For more information on the evaluation methodology, including limitations, see Appendix B.

Findings

Evaluation findings are presented using the following themes: Emergency preparedness, Detection and reporting, Emergency response and mobilization, Sustained EPR system in Canada, and Collaboration, coordination, and governance.

Emergency preparedness

Key takeaways: Over the past five years, the EPR program has maintained and improved emergency preparedness within PHAC. Plans and procedures have been updated, exercises have taken place, and training has been enhanced and is easily accessible for all staff. Findings indicate that training and exercises need to remain a priority to support staff skills and overall readiness.

Plans and processes

PHAC relies on a series of emergency plans to guide roles, responsibilities and processes as they relate to emergency response. Recent emergencies such as COVID-19 underlined the need for clear roles and responsibilities, as well as regularly planned updates and exercises of these plans. Considerable progress has been made over the past three years on addressing recommendations from external and internal reviews, including those referenced in various Office of the Auditor General (OAG) reports. Most OAG recommendations related to PHAC's emergency response function have been substantially or fully implemented.

For example, ROEMB has updated and conducted exercises of the Health Portfolio Emergency Response Plan (HP ERP), is on track to meeting its commitment to update the Health Portfolio Strategic Emergency Management Plan, and has engaged with provinces and territories (P/Ts) on updating the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events.

Highlight: The updated HP ERP was implemented in September 2023. Key revisions to the Plan included enhanced process flexibility, integrating health equity considerations, clarifying roles and responsibilities as well as escalation and de-escalation criteria and steps. Updated criteria were applied successfully to support the de-escalation and deactivation decision for the 2023 Wildfires Activation. Other HP ERP updates were tested via several exercises. The next step is to develop a regular planning cycle to test and update plans on a continuous basis.

The updated HP ERP now provides a framework for applying health equity considerations before, during, and after an event response. Key elements of the framework include:

- enhancing health equity competencies for operational staff through training;

- considering population inequities in risk assessment and operational planning;

- advocating for event partners to assess and mitigate health equity impacts;

- integrating health equity considerations and principles as part of decision-making;

- embedding health equity perspectives in response processes; and

- incorporating health equity assessment in after action reports and recommendations.

As highlighted in a lessons learned review conducted by PHAC's Office of Audit and Evaluation, "(t)he COVID-19 pandemic and response illuminated and amplified existing social, economic, and health inequities in Canada and globally. Many of the lessons learned during the pandemic reflect the need to integrate equity considerations within future public health emergency planning and decision making to avoid unintended harm and consequences to populations already experiencing inequities and to support equitable outcomes for all people".Footnote 2 The updated HP ERP and integration of a health equity lens are expected to create more equitable outcomes and better support Canadians to sustain their wellness during the spectrum of public health emergencies in the years ahead, from infectious diseases to climate-related events.Footnote 3 Moreover, other HP ERP revisions, such as enhancing the flexibility given to activation levels, were also impactful on EPR performance following the implementation of the Plan.

Progress was also made on updating key operational documents in 2023-2024, including the CER's Concept of Operations and updated IMS job action sheets. CER also has an experienced Response Readiness team, with dedicated resources to continue updating the tools and operational guidance provided to staff that are mobilized during a response. Additional guidance may be needed on the steps and processes for those working in an IMS, including process maps, templates, critical paths, and SOPs as well as making continuous improvements an integral part of any activations.

Moreover, following best practices, each RECC has created a regional Annex to the HP ERP and customized the activation levels and regional response structures to reflect their appropriate P/T stakeholders and relationships. Revised activation levels provide clearer roles and responsibilities, as well as more flexibility and efficiency to address large scale or fast moving events, and better alignment with the HPOC, P/Ts, and the Government Operations Centre (GOC) activation levels and emergency management functions. New SOPs will also be prepared in line with the new HP ERP activation levels and processes. RECCs are also working on updating their Concept of Operations to include a hybrid response model comprised of physical and virtual presence. Lastly, the NMLB-EOC has updated eight of its SOPs since 2019, including the update to their operations centre SOP in January 2024, which provides clear mechanisms on how the NMLB-EOC functions, as well as updated response levels to align with HPOC and GOC.

Training

A lack of public health EM training was seen as an important gap in the early COVID-19 response at all levels of the Agency, including senior management. There have since been significant improvements in this area. For example, foundational Public Health Emergency Management (PHEM) training was mandated Agency-wide in 2022 and an Executive Committee Orientation on EM was implemented. A PHEM Portal was also launched in November 2023, which includes a full suite of more advanced EM training and resources. As of July 2024, nearly half (48.4%) of the target audience for the foundational emergency management and public health course had completed it, which is similar to the median completion rate for other PHAC mandatory courses. Targeted training sessions were also delivered to Directors General (DGs) and Vice-Presidents (VPs) to increase senior management knowledge and skills in EM principles.

As events and emergencies often require coordination between PHAC and HC centres of expertise, it would be a good practice to expand EM mandatory training to HC staff. This was a key area for consideration in the 2023 Wildfires Activation Case Study, as many of HC's staff had no prior experience or IMS training. While one EM course is mandatory at PHAC, none are mandatory at HC. However, in the winter of 2024, HECO developed a HC Emergency Management Training Strategy and has successfully promoted the training among HC employees.

Recognizing the progress to date, many internal interviewees identified training as an ongoing priority area for the EPR program, with some noting that continued regular training is needed to maintain skills, including practical training through mentoring, job shadowing, and participating in exercises. Moreover, EM training could be extended to the wider EM community, such as P/T partners, and the full set of training included on the PHEM portal could be better promoted to HP staff.

In addition to Agency-wide PHEM training, documents indicate that EM training for regional staff is ongoing, with many offices developing formal training plans and exercise calendars to build regional surge capacity. Documents shared by NMLB also showed ongoing commitments to train staff by combining practical and online training. Specifically, NMLB-EOC offers a 6-week practical training after the basic online training, including three 2-week rotations with shadowing, allowing for a more thorough experience and better preparedness for an efficient response.

Exercises

While the Agency participated in a broad range of partner-led exercises, given the COVID-19 context, CER and CEP were not in a position to lead regularly planned exercises and drive a strategic HP exercise agenda based on risk and capability assessments and lessons learned from previous activations over the last five years. As shown in Appendix C, throughout the evaluation scope period, CER and CEP were a part of five exercises, four of which were conducted in the last two years, including a tabletop exercise internal to PHAC related to H5N1, in collaboration with IDVPB. Interviews and documents indicate that there is a need to test plans and processes on a more regular basis in order to exercise different scenarios, as well as provide more opportunities to focus on the training of staff and senior management as part of the exercise cycle. In 2023-24, CEP developed an annual exercise calendar, as well as a service delivery model, that includes tools and templates to assist program areas with the development of exercises. Communication and promotion of this calendar will be imperative to raising awareness about upcoming exercises and opportunities to participate. The development and sharing of best practices for emergency preparedness, as well as more frequent exercises could also help to spread the responsibility for preparedness across the HP in a more coordinated way.

As shown in Appendix C, during the scope period, regional EPR units participated in 31 exercises with their respective external partners, including other government departments in the regions, P/Ts, and municipalities. NMLB also facilitated and participated in numerous internal and external training exercises to enhance outbreak preparedness. For example, Emergency Preparedness and Response Officers ran an internal and an external exercise in 2022-23, as well as 10 Incident Command System training sessions for 211 NMLB staff members. In total, NMLB-EOC participated in 12 internal and external exercises during the evaluation scope period, including a PHAC-led Canadian Polio Outbreak Simulation Exercise alongside federal, provincial, and territorial (F/P/T) partners to simulate a response to a laboratory-acquired polio infection in Canada.

Detection and reporting

Key takeaways: With investments over the last three years, detection has improved within the HP public health emergency preparedness and response system. Modernization of the GPHIN has enabled stronger collaboration with PHAC surveillance programs and external partners, strengthening and broadening GPHIN's reporting on potential public health threats. However, the establishment of the State-of-the-Art GPHIN Platform and Analytical System has been delayed.

Detection and risk assessment improvements

Various reviews conducted during the COVID-19 response identified weaknesses in terms of event detection. In response to the recommendations of OAG's 2021 Report 8 - Pandemic Preparedness, Surveillance, and Border Control Measures, the Agency committed to making further improvements to the GPHIN Program and its processes for issuing GPHIN alerts, now referred to as early-warning notifications, taking into account both the OAG recommendation as well as the final recommendations of the independent review of GPHIN.Footnote 4Footnote 5

Did you know? Established in 1997, GPHIN is an early-warning public health event-based surveillance (EBS) system, which relies on publicly available information sources and specialized staff with scientific and technical expertise. GPHIN provides increased situational awareness for all-hazards potential public health threats worldwide: including chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and infectious diseases and outbreaks.

A Management Response and Action Plan (MRAP) was developed to address the recommendations from the GPHIN Independent Review. These recommendations informed the work underway at PHAC to review its processes, to identify improvements, and to clarify and streamline the decision-making process for the issuance of GPHIN products, including alerts. The Detect, Understand, and Act (DUA) Framework complemented the GPHIN review's MRAP and supported broader efforts to optimize the Agency's ability to detect public health threats, understand the risks, and act as needed to prevent and mitigate those risks. Specifically, DUA funding supported the creation of the Public Health Security Intelligence Division, which houses both GPHIN and the Agency's classified intelligence teams, GPHIN Program modernization, and enhancement of PHAC's security and intelligence capabilities. DUA funding also allowed ROEMB to expand and enhance its surveillance and reporting activities, including for classified information, establish new ways of working with internal and external partners to support the sharing of information about public health threats, and increase its capacity to track events in 10 languages, taking into account cultural and contextual considerations. Key GPHIN achievements include:

- expanding networks by doubling the GPHIN user base to over 1,700, including international stakeholders and all P/T public health organizations across Canada;

- establishing the GPHIN Flags and Tags Initiative to effectively share GPHIN signals with other surveillance programs and risk assessment functions;

- improving the Agency's capabilities for global and domestic all-hazards event-based surveillance;

- introducing the GPHIN Emerging Issue Report to provide early situational awareness of potential public health threats to Canadian and international stakeholders; and

- increasing access to classified intelligence to enhance the situational awareness of public health decision makers.

With support from DUA funding, GPHIN also established new processes and products. Internal interviews indicate that there is appreciation of the GPHIN daily reports and the new GPHIN emerging issues report. Some interviewees identified that the usefulness of these products could be enhanced through timelier distribution and better integration with program needs and priorities.

As shown in Appendix F, for 2023-2024, ROEMB provided 100% of GPHIN notifications and alerts to stakeholders within the defined timelines, a 10% increase from 2022-23. For the same period, they also completed 80% of requests for information (RFIs) to support the specific information needs of internal and external partners and stakeholders, which is under their target of 100%. RFIs are specific information requests made by partners and stakeholders, whereas GPHIN notification alerts are proactively developed and communicated to partners and stakeholders.

| Year | Planned | Actual | Total variance | % of budget spent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022-23 | $1,792,709.00 | $1,318,007.17 | $474,701.83 | 74% |

| 2023-24 | $11,010,468.00 | $5,554,296.00 | $5,456,172.00 | 50% |

| Total | $12,803,177.00 | $6,872,303.17 | $5,930,873.83 | 54% |

Although several improvements to GPHIN have been made, 7 out of the 25 GPHIN deliverables under the DUA Framework were moderately off track as of April 2024. Progress on achievement of deliverables advanced shortly after; however, this was after the evaluation's scope period. The variance analysis presented in Table 2 also shows important underspending for GPHIN-DUA funding in the last two fiscal years, and a projected large surplus for 2024-2025, which is the last year of DUA funding. Reviewed documents indicate that most of the delays appear to be attributed to organizational and human resource challenges. For example, they experienced challenges with hiring staff with the needed skillset due to only being able to offer term positions, given the temporary nature of the funding. Moreover, lengthy HR recruitment processes meant a shorter time frame for staff to be at strength, while the funding was still available. This includes the significant time of approximately six months involved in obtaining a Top-Secret level security clearance, which is a requirement for many members of the classified intelligence team. In addition to HR challenges, expanded classified activities are new to the Agency and it required significant time to establish intelligence processes and build relationships with security and intelligence partners.

Moreover, the establishment of an updated GPHIN Platform and Analytical System to increase analytical capabilities could not be completed within the original planned timelines. This project was known as the GPHIN Next Generation Project and faced delays due to its complexity and the necessary careful planning and due diligence needed for an IT initiative of this nature. At the time this report was written, the project team was exploring options to determine the best approach going forward, in collaboration with project partners.

DUA funding also supported improvements to integrated threats and risk assessment with the establishment of the Centre for Surveillance, Integrated Insights and Risk Assessment (SIIRA) within the Data, Science and Foresight Branch (DSFB). SIIRA coordinates and oversees integrated threat and risk assessment in PHAC to anticipate, detect and assess public health risks. Although SIIRA operates outside of ROEMB, and its specific activities are out of scope for this evaluation, the coordination role it plays in risk and threat assessments is an important part of the EPR program, as per its inclusion in the Health Portfolio Emergency Response Plan (HP ERP).Footnote 6

Within SIIRA's threat assessment process, signals are detected and verified by PHAC's various centres of expertise. If a signal poses a potential public health risk, the responsible PHAC centre of expertise initiates a threat assessment. They enter key information and their initial threat assessment, using a standardized methodology, into the Integrated Threat Assessment Platform (ITAP). On a weekly basis, SIIRA compiles the ITAP submissions from the various PHAC centres of expertise into a draft Threat Report that is used to inform and support decision making. These reports support situational awareness of threats, their assessment status by the various PHAC program areas, the actions taken to address them, as well as next steps. Between SIIRA's inception in April 2022 until the end of March 2024, 93 weekly threat reports had been produced and 14 risk assessments had been completed.

SIIRA's risk assessments and threat reports are important lines of evidence to support decisions on EPR measures. PHAC's various centres of expertise are at the core of SIIRA's threat and risk assessment process; however, this did not originally include the integration of HC's expertise on risks and threats in its authorities. In an effort to integrate HC's input, HECO was added in September 2024 to SIIRA's threat assessment process. HECO now receives SIIRA's signal requests, attends the weekly meeting, and is looping in HC programs as needed.

Emergency response and mobilization

Key takeaways: Over the last five years, PHAC has successfully responded to multiple requests for support and mobilized the IMS when needed to coordinate responses to public health events. However, given the length and breadth of the COVID-19 IMS mobilization, the main challenge encountered by the program was related to rapidly mobilizing staff for concurrent IMS mobilizations and maintaining a surge capacity over time.

Health Portfolio activations

Activation levels during the evaluation period from April 2019 to September 2023 were described as follows in the 2013 HP ERP:

- Level 1 – Surveillance, detection and alerting: This level corresponds to normal operations. All-hazard information is monitored and recorded by HPOC.

- Level 2 – Increased vigilance and readiness: This level is adopted when an event or emergency occurs or may occur that impacts the responsibilities of HP program areas beyond their capacity, requiring increased coordination and planning.

- Level 3 – Partial escalation: This level is reached when the impact, or potential impact, of an event or emergency requires the greater use of HP assets and resources to adequately respond.

- Level 4 – Full escalation: This level is adopted when the impact, or potential impact, of an event and emergency requires the greatest use of HP assets and resources to adequately respond.

With the update of the HP ERP approved in September 2023, routine operations now correspond to Level 0, Level 1 is enhanced reporting and planning, Level 2 is mobilized response, and Level 3 is full-scale activation.Footnote 7

The initial decision on the appropriate activation level begins with an assessment of the risk level associated with an event and considers a variety of factors. These include the complexity, severity, speed, duration, and extent of the resources needed to respond to the event, as well as the processes needed to support them, both for HP support requirements and to address requests for assistance (RFAs) from external partners. These activation levels are generally sequential, though some events may require an immediate Level 2 or 3 response. Table 3 summarizes the number of activations by level for HPOC, RECCs and NMLB-EOC. The only Level 3 activation corresponds to the COVID-19 response.

| Level | HPOC | RECCs | NMLB-EOC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 2 events; 60 days | 4 events; 142 days | 1 event; 90 days |

| Level 2 | 5 events; 806 days | 2 events; 38 days | 6 events; 626 days |

| Level 3 | 1 event; 1,080 days | 1 event; 1,080 days | 1 event; 987 days |

| Level 4 | 0 event; 0 days | 0 event; 0 days | 0 event; 0 days |

IMS mobilization

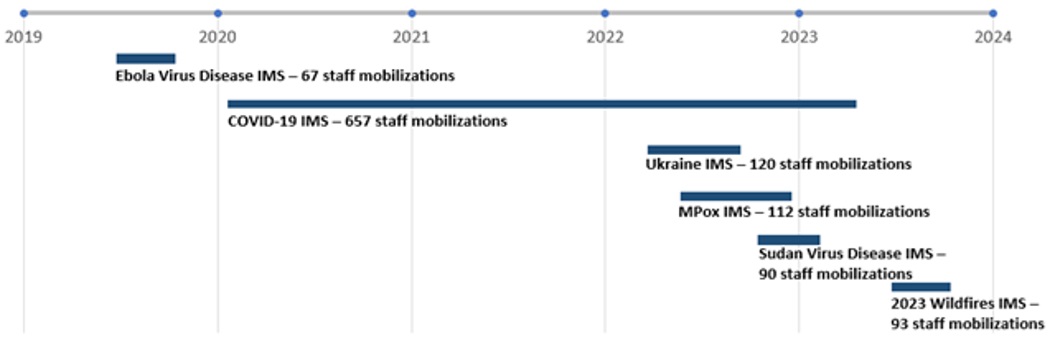

The IMS is a response tool that may be mobilized to support an event and then demobilized following the response. HP activations over the evaluation period have led to six IMS mobilizations, as identified in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Text description

Figure 1 is a timeline showing the IMS mobilizations between fiscal years 2019-20 to 2023-24. The events are depicted by a bar to show the length and number of individuals mobilized for each event. From 2019 to 2023, the events shown are as follows:

- A small bar towards the end of 2019 for the Ebola Virus Disease, resulting in 67 mobilizations;

- A long bar spanning from 2020 to early 2023 for the COVID-19 IMS, resulting in 657 mobilizations;

- A medium bar mid-2022 for the Russian Invasion of Ukraine IMS which resulted in 120 mobilizations;

- A medium bar mid to end of 2022 for the Mpox IMS which resulted in 112 mobilizations;

- A small bar at the end of 2022 and beginning of 2023 for the Sudan Virus Disease IMS which resulted in 90 mobilizations; and

- A small bar mid-2023 for the 2023 Wildfires IMS which resulted on 91 mobilizations.

These six IMS led to a total of 1,139 staff mobilizations, with COVID-19 representing close to 60% of those mobilized in the past five years. While these are unique staff mobilizations, some individuals were most likely counted twice if they participated in more than one IMS. As can be seen in Figure 1, four IMS mobilizations overlapped, adding to the challenge faced by the Program in maintaining continuous surge capacity to mobilize staff within these IMS.

IMS mobilizations were overall successful at addressing the goal of responding to all hazard public health events. As shown in Appendix F, for the last two fiscal years (2022-23 and 2023-24) 90% of response objectives were met, as captured in the Incident Action Plans during an activation, slightly below their target of 100%. Still, some challenges were encountered:

- At the beginning of a response, it was not always clear which centres of expertise should lead the response process.

- At the end of a response, in some cases, it was not always clear who should continue to address the public health event after de-escalation, as part of regular or mandated responsibilities.

- Mobilized staff were unclear about their roles and responsibilities as outdated documents, like job action sheets, did not provide a clear sense of requirements.

These questions should be addressed early in an activation to engage the appropriate centres of expertise, minimize duplication, and support business continuity. In some cases, the nature of the public health event and its impacts were complex, as they overlapped with other areas of expertise or were not always clear. For example, at the beginning of the 2023 Wildfires Activation, it was unclear who the response lead should be and which plan should be used, including associated processes and governance, as wildfires are considered both natural and chemical events, due to smoke. According to emergency plans, PHAC is the lead for natural events while HC is the lead for chemical events. Early and ongoing engagement with HP programs in a response will be important for improved activity coordination going forward, in order to clarify who should be the lead of an event, as well as how programs will support the response or not.

In early 2024, processes were changed to include a CEP emergency plan expert in the HP Situational Assessment Team (HP SAT) meetings. This should help ensure that activations are informed by the appropriate plans, including associated processes and governance. In addition, since September 2024, the increased collaboration with HECO is expected to better support the identification of which program should be included as part of a response when an event's potential health impacts may fall within HC's authority.

Moreover, mobilized staff joining the IMS should be offered a systematic orientation program beyond the mandatory training in order to set them up for success. As previously noted, many documents provided to mobilized staff were out of date, such as job action sheets, leading to challenges. For example, the lack of formalized processes and standardized onboarding and handover policies and practices led to inconsistencies within the Mpox IMS, and created additional obstacles for response personnel already working in a stressful environment. Key operational documents such as IMS job action sheets were updated in 2023-24 and are expected to improve the efficiency of IMS onboarding.

Staff mobilizations within PHAC

Given the length and breadth of the COVID-19 IMS mobilization, maintaining surge capacity within the Agency has been an important challenge for the program over the last five years. Mobilization challenges experienced over this time highlight the need to re-prioritize a mobilization framework to support various types of events, including large and prolonged responses. More specifically, the COVID-19 lessons learned exercise conducted by the Office of Audit and Evaluation identified that PHAC needs a robust mobilization framework that can support the quick deployment of a surge capacity and the appropriate support to sustain this capacity in the longer term. The lessons learned also identified that this strategy should provide a foundation to:

- Ensure that the HP has the right blend of operational capacity and science-based expertise built in and ready to address future challenges.

- Allow for the quick mobilization of additional capacity and expertise within the HP and the rest of the federal government that could include having an inventory of expertise in core areas.

- Support the well-being of mobilized employees throughout the response.

- Build the foundation to quickly ramp up support functions, including staffing, financial management, procurement, and IT systems.

The various IMS mobilizations that occurred during the scope period of this evaluation allowed the Agency to collect a wide range of real-time mobilization data. This data and the respective staffing challenges experienced in each IMS mobilization should help inform the development and implementation of the mobilization strategy. The importance of considering such data was also identified in the Evaluation of Emergency Preparedness and Response Activities 2012-13 to 2016-17.

There are still shortcomings with current processes and policies that support mobilization within the HP. For example, there are no agreements in place for the release of staff to the IMS, and mobilization tools such as the All-Events Response Operations (AERO), as well as other rostering processes, are outdated. CER, in collaboration with partners including the Human Resources Services Directorate and HC's HECO, since winter 2024, has been working towards implementing a mobilization framework, that will include references to internal staffing, including program support, the Emergency Response Cell and IMS, and rostering, among others. In the meantime, pre-identified staff are ready to respond in key roles. While an IMS readiness roster of pre-identified individuals available for key roles is being piloted, some internal interviewees indicated that this approach to call upon the same targeted individuals is not sustainable and is leading to mobilization fatigue. There is also evidence that managers are still reluctant to release staff for mobilizations due to competing workloads or the inability to backfill positions. Also, for those who are mobilized, recovery periods are not always possible, and they must catch up on work that accumulated during their absence. To address this issue, participation in the decompression program following mobilization should be encouraged as a way to support recovery, coupled with feasible rotations to avoid burnout, and backfilling positions when required.

The mobilization framework should also take a coordinated approach with program areas and consider, as much as possible, their resource planning. This would further support an emergency management culture across the HP. Mobilization best practices from other government departments could be considered as part of the framework. Consultations and workshops on the development of the approach to mobilization identified the following key areas to be addressed as part of the mobilization framework:

- Creating a response mobilization culture and an ability to prioritize work to free up resources to be mobilized as part of a response;

- Providing a clear and measurable definition of response readiness and the requirement for preparedness activities, including training, to be tied to those personnel on response rosters;

- Providing increased predictability to staff and management as to when mobilizations will take place and for how long;

- Building more streamlined and uniformed mobilization processes and improving process transparency;

- Streamlining predictable HR processes and plans regarding mobilization to support rapid response; and

- Developing clear financial processes for event response, including for costs associated with preparedness activities and cost recovery.

Each RECC has built their own regional surge capacity by training and exercising regional staff. Regional EPR staff also provide surge capacity to each others' regions, as needed. For short-term responses, RECCs indicated that existing mobilization process could be leveraged. However, for more significant events or longer-term activations, RECCs would continue to require long-term surge capacity. At the time of writing this report, a framework for a new hybrid reservist model for border operations was being developed to improve surge readiness to carry out functions under the Quarantine Act.

Domestic surge support within Canada

Staff mobilization

CER's Response Support and Technical Assistance (RSTA) team is responsible for receiving, assessing and triaging RFAs received from both domestic and international partners. Evidence shows that processes to mobilize staff to support partners' surge needs are in place and are used regularly. For example, 100% of P/T RFAs for deployment of Agency staff to P/T partners were responded to within negotiated timelines each year during the evaluation period, highlighting the Agency's response capacity.

The Canadian Field Epidemiologist Program (CFEP) and the Canadian Public Health Service (CPHS) are the Agency's field service programs. The CFEP builds Canada's public health capacity by training public health professionals in applied epidemiology with the specialized techniques and competencies required to respond to diverse public health issues in real-life settings. As of fiscal year 2024-25, the size of the CFEP cohort went from five participants to seven, which increases the total number of deployable staff.

The CFEP also mobilizes field epidemiologists anywhere they are needed within Canada or around the world, supporting public health organizations as they respond to urgent public health events. Specifically, the CFEP has a highly trained and competent workforce ready to be mobilized for three-to-four-week durations to support surge requests for epidemiological assistance. Between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2023, CFEP reported 78 domestic RFAs with a total of 93 epidemiologists mobilized within Canada.

CFEP mobilization can also occur within PHAC. For example, epidemiologists were mobilized to support PHAC program areas at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the repatriation quarantine sites operations in Trenton and Cornwall. However, CFEP stopped tracking these mobilizations in 2023, thus data on these internal mobilizations cannot be reported.

The CPHS also recruits and places field staff at partner organizations across Canada to augment local capacity around priority public health needs, such as substance-related harms surveillance. Their work plans can be rapidly pivoted and new teams of public health officers can be scaled up to respond to emerging issues or public health emergencies, like the Opioids crisis in 2018 and COVID-19 in 2020. However, there remains a need to identify mechanisms to engage other professional categories beyond epidemiologists in surge response, such as nurses, and health informatics supports, as well as to build surge capacity for epidemiologists for longer than the traditional three-to-four-week period provided for by the CFEP program.

Other field services programs at the agency include laboratory field support led by NMLB, as well as Field Surveillance Officers in the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control. These may also provide rapid surge capacity, but their deployment processes and training are not coordinated by ROEMB. Documents indicate that CEP plans to coordinate activities with other field services groups within the Agency.

External mobilizations within Canada are also facilitated through the Operational Framework for Mutual Aid Requests (OFMAR), a non-binding mechanism that can be activated by P/Ts to identify and share health care professionals and health assets across jurisdictions during events. Although originally created for physicians and nurses, the tool is flexible and can be expanded to identify other health care professionals.Footnote 8 As shown in Appendix F, 100% of provincial and territorial RFAs through OFMAR were responded to within negotiated timelines throughout the evaluation period.

Asset surge support

In terms of the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS) surge capacity readiness, RFA processes are in place and PHAC's capacity to deploy assets is strong. During the evaluation scope period, 100% of P/T RFAs for supply provision were addressed within negotiated timelines, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. The NESS also maintains a comprehensive suite of SOPs that govern its key materiel management activities. Ongoing development and use of the NESS warehouse management system is expected to continue improving inventory tracking and management.

Did you know? P/Ts are primarily responsible for the provision of medical equipment and supplies and other goods necessary to support health care and reasonable preparedness for most common emergencies. However, consistent with the principles of the Emergency Management Act and various federal and F/P/T emergency management plans, the federal government, through the NESS, plays a critical surge capacity role in supporting public health emergency management by facilitating access to critical goods when PT capacities are exhausted or not immediately available.

In response to unprecedented global demand for medical equipment and supplies at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and in order to address observed gaps in supply, the NESS made significant investments to adapt its approach and transform its capabilities. It also provided increased F/P/T surge support to respond to an unprecedented volume of RFAs and entered into bulk procurement on behalf of F/P/T partners.

NESS evolution

The NESS pre-COVID (2019):

- 31 employees

- 8 warehouses comprising 178K square feet

- Approximately 3 to 5 RFAs per year

- Priority focus on niche medical countermeasures (MCMs) for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats

- Limited holdings of routine MCMs

The NESS in 2023:

- 150 employees

- 20 warehouses comprising 1.7M square feet

- 600 RFAs from April 2020 to March 2023

- Capability to respond to multiple concurrent events with a wide range of MCMs

- Expanded focus on routine MCMs necessary to support pandemic response

Quick facts from March 2020 to December 2023:

- Over 300 contracts issued

- Over 4 billion units of medical supplies and equipment procured

- Over 2 billion units received, validated and deployed for emergency use

- Over 600 requests for assistance

- Over 14M units of medical supplies and equipment donated

- Scaled to approximately 3M square feet of warehousing space

NESS investments prior to the pandemic were supported by limited ongoing funding and time-limited investments for specific events. This resulted in prioritization of niche drug MCMs for high consequence and lower probability threats over PPE and other routine medical assets that were thought to be more readily available through the market.Footnote 9

According to the findings of the 2021 OAG Audit Report 10 – Securing Personal Protective Equipment and Medical Devices, PHAC, HC, and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) helped to meet the needs of P/Ts for medical devices during the pandemic, but PHAC was not as prepared as it could have been to respond to P/T requests as a result of long-standing funding gaps and unaddressed problems with the system and practices in place to manage the NESS. Therefore, the OAG recommended that PHAC "should develop and implement a comprehensive NESS management plan with clear timelines that responds to relevant federal stockpile recommendations made in previous internal audits and lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic".Footnote 10 In response, PHAC committed to developing and implementing a NESS Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP) to address the various recommendations made throughout the years. The CMP was approved in May 2024 and provides a roadmap for the systematic and scalable transformation of the NESS, with the aim of building upon gains already made with temporary funding to improve the management of the NESS and maintain an appropriate readiness posture in the face of an ever-evolving threat and risk landscape.

As outlined in the CMP, there is a need to establish national targets and clarify respective F/P/T expectations with regards to coverage of these targets for key commodities. As part of the CMP, the NESS intends to develop a data strategy that outlines requirements, sources, and mechanisms needed to support NESS decision making, including the development of national targets. This work is expected to leverage improved F/P/T information sharing on asset holdings, science assessments, risk assessments, modelling, and scenario planning to inform national targets for key MCMs. The NESS is collaborating across the Health Portfolio and with security and intelligence partners to identify and assess threats and potential supply chain issues, as well as to leverage their expertise in scenario planning and modelling to develop interim supply targets. Key partners and stakeholders are aware of health emergency material capabilities available in an emergency and how to access them; however, some gaps exist with respect to awareness of specialized assets such as pharmaceutical medical countermeasures, but these are being addressed.

Highlight: NESS has developed the CMP, which features a foundational analysis of key documents, including relevant findings from past audits, evaluations, and lessons learned. It also outlines a number of key action items that will help the NESS meet the strategic goals identified within the Plan. Some of these action items include clarifying F/P/T roles and responsibilities for medical supply readiness, securing additional policy and legal authorities, and strengthening NESS' capabilities for risk and capability assessments to better define medical supply targets.

While the CMP is expected to address many of the challenges raised in the context of past audits, evaluations and lessons learned, it will be important to prioritize timely implementation of the Plan. Given that many strategic goals are dependent on collaboration with P/Ts, OGDs, PHAC programs, and external partners and stakeholders, the CMP recognizes that early engagement to validate timelines and scope is required to implement the actions and to confirm the capacity of all partners involved to complete the work.

International mobilizations

PHAC's epidemiological and laboratory expertise is also required to support short-term, international responses. International efforts are undertaken to support outbreak investigations at the request of international organizations like the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN). Moreover, current processes allow the Agency to assess RFAs, identify qualified individuals, mobilize them internationally and bring them back to Canada safely. At the time of this report, the RSTA team was working on updating the 2012 policy on the mobilization of PHAC staff outside of Canadian borders. International RFAs have led to 19 mobilizations between 2019 to 2023.

Equity and official language considerations

The Mpox and 2023 Wildfires mobilizations were identified as recent examples where equity, diversity, and inclusion considerations were brought forward as key priorities during responses. Specifically, communications targeted to those who were disproportionately affected by the event, and the integration of differential risks for particular groups in risk assessments were highlighted as areas that have improved as a result of experience acquired during the COVID-19 response. Targeted engagement with stakeholders to reach key populations is another example. During the 2023 Wildfires response, in collaboration with P/Ts, NESS proactively distributed surplus N95 respirators to priority populations. In addition to PTs and OGD partners, NESS targeted alternative delivery channels, such as Indigenous Services Canada, northern and remote Indigenous networks, community organizations, and non-governmental organizations to distribute N95 respirators. NESS also leveraged the GCDonate platform to provide surplus N95 respirators to registered parties, including registered charities, non-profit organizations, and other levels of government.

Other challenges raised with respect to equity, diversity and inclusion during responses were related to balancing the need for urgent public health communications with accessibility requirements. In an emergency response, it is essential to provide information to the public as soon as possible. In some cases, for online content, this leads to publication delays and lower-quality translations. Interviews indicate that this is mainly due to quick reviews and fewer resources having the ability to work in both official languages.

Another challenge with respect to inclusive public health communication is presenting the information to the public in plain language. Often, CPAB receives content that is too technical and over the recommended reading level for the general public. CPAB must then work with subject matter experts to revise content into plain language, which takes time. Highly technical or jargon-heavy text can also be misinterpreted during translation, leading to errors or poorer quality. Interviewees identified a need for human resources that are proficient in both official languages, with the appropriate subject matter and public communications expertise to prioritize the quality and timeliness of products shared in both official languages.

Collaboration, coordination and governance

Key takeaways: Overall, the COVID-19 response strengthened PHAC's internal and external collaboration and coordination of activities. In addition, recent improvements have been made within the emergency management governance structure that already support and facilitate a more coordinated HP emergency preparedness and response system. However, improvements could be made with respect to information sharing across branches, as well as within ROEMB.

HP collaboration and governance

The HP emergency management governance structure has evolved over the course of the evaluation period. As a result of the COVID-19 response, key preparedness governance committees were put on hold as efforts were focused on response activities. As such, the HP governance structure for conducting strategic emergency management planning, known as the Health Portfolio Emergency Preparedness Committee (HP EPC), was halted, including the Risk and Capability Assessment Task Group, a HP EPC key working groups.

In 2022, the HP EPC was officially replaced by the VP Emergency Management Executive Committee (EMEC) and the DG EMEC. However, there was no replacement or reactivation of the Risk and Capability Assessment Task Group.

The Risk and Capability Assessment Task Group was responsible for leading the development of comprehensive risk and capability assessments for the HP. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the HP EPC would use the assessments generated by this Task Group to assess the provision and level of emergency management services and their state of readiness. CEP is currently working on building a new risk and capability assessment program, which is discussed in more detail in the "Sustained EPR system in Canada" section of this report.

Following the implementation of the VP and DG EMEC in 2022, the evaluation found that executive decision-making governance was back in place to oversee departmental emergency management functions. The VP EMEC was setting the strategic direction on emergency management functions across the HP and making decisions on the emergency management function, while the DG EMEC implemented the directions set by the VP EMEC.

The VP EMEC and DG EMEC included both PHAC and HC representation. Having consistent representation of both PHAC and HC at governance tables has helped to maintain situational awareness across the HP, while providing an opportunity to represent respective mandates and interests. Specifically, the evaluation found that collaboration with HC has improved with the establishment of HC's Health Emergency Coordination Office (HECO), in fall 2023. HECO was highlighted as a key function in facilitating effective governance and coordination of activities between both organizations.

The roles and functions of the VP and DG EMECs as planning and preparedness governance committees were well understood; however, several interviewees indicated that the governance transition from preparedness to response was not always clear. More specifically, when an IMS response governance structure is implemented, it is not always clear who should be the lead, who should sit on the Health Portfolio Executive Group (HPEG), which is the executive-level forum that provides strategic decision making during a response, and how the approval processes should proceed when associated health challenges touch several areas of expertise within the HP. While the IMS governance structure is clearly defined in the updated HP ERP and its various annexes, there is a lack of awareness of these defined structures that can create challenges with approvals and coordination with partners.

Aside from the difficulties that can be observed during responses, internal collaboration and coordination for the EPR program work well overall. Information sharing occurs at the senior management level, and CER and HPOC have networks for sharing information to branch single windows and working contacts, such as HPOC Daily and Flash Reports. However, internal interviews indicate that some information is not always flowing across branches, which can lead to missed opportunities for early collaboration and duplication. As previously noted, ongoing and early engagement with programs and partners are important for coordination, both during and outside of a response, including effective integration with the regions and NMLB.

Despite improvements noted by the evaluation to the preparedness governance structure, the VP EMEC was discontinued in August 2024. This was the result of an Agency-wide governance review where the need to streamline the governance at the VP level was identified. This resulted in the creation of a new VP table responsible not only for EM, but also for other corporate subjects. The potential impact of no longer having a dedicated EM VP governance table on HP coordination of EM is unknown. As this new governance model is being implemented, considerations should be given to maintaining an engagement with HC when EM questions are being presented to this new committee. ROEMB and HECO are working together to address potential governance gaps resulting from the discontinuation of the VP EMEC.

F/P/T collaboration and governance

The Pan-Canadian Public Health Network (PHN) is a formal governing body of F/P/T governments across Canada, working together to strengthen and enhance public health. The PHN supports horizontal linkages across public health policy issues through close collaboration with senior government decision makers and other key players in the public health system. As part of this network, PHAC engages and collaborates with F/P/T partners on cross-cutting emergency management issues through the Public Health Emergency Management Working Group (PHEM-WG), previously called the PHEM Task Group.

The PHEM-WG did not meet in the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic due to the emphasis on response; however, committees were formed to support the Special Advisory Committee (SAC) within the F/P/T COVID-19 governance structure. These committees included the Technical Advisory Committee, the Logistics Advisory Committee (LAC), PHN Communications Working Group, and the Public Health Working Group on Remote and Isolated Communities.

Did you know? The PHEM-WG updated its reporting structure in January 2024. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the PHEM WG reported through the Public Health Infrastructure Steering Committee (PHI-SC) whereas now it reports directly to the Public Health Network Council. The PHEM WG will support discussion on cross-cutting emergency management issues from a pan-Canadian perspective and help identify urgent and emerging issues.

A survey of LAC members showed that the LAC was useful and effective for F/P/T collaboration in the response to managing COVID-19; however, a need was identified to clarify the reporting relationship between LAC and other committees, including SAC, LAC Task Groups, and other ad-hoc committees, as well as the need to streamline all of the various information tools and resources into one place. Other suggestions included determining a set of guidelines on when the LAC could be activated on an ad-hoc basis to address other outbreaks, and a review of the LAC mandate to define appropriate membership and establish a clear distinction between the LAC and the PHEM-WG.

Coordination and collaboration between ROEMB and P/Ts were also strengthened during the COVID-19 pandemic period. F/P/T public health emergency management governance structures, primarily through the PHN, continue to work well. Internal documents and interviews indicate that clear structures, processes, and tools are in place to streamline information sharing, thus facilitating and supporting effective governance. However, external interviewees noted that they were less aware of PHAC's preparedness activities and welcomed the opportunity to engage more on the broader scope of preparedness activities.

Regional coordination and collaboration between Regional EPR Units, OGDs, and P/Ts were also highlighted by interviewees as very strong. Strong relationships are also observed between NMLB-EOC and its partners. HPOC has also developed strong relationships within the emergency operations community, including with the regions and F/P/T partners. Within CER, HPOC functions as a 24/7 all-hazard single window that triages public health events that require immediate attention, informs decision makers, and delivers regular and timely reporting to inform event-related situational awareness and decision making.

International collaboration and governance

International Health Regulations

The International Health Regulations (IHR) function as an international treaty requiring the World Health Organization (WHO) and signatory countries to build their capacity to detect, assess, report, and respond to public health events. As a signatory to the IHR, Canada is committed to help strengthen global health security and build capacities to detect, assess, report, and respond to public health events in Canada and abroad to minimize their spread or impact across borders.

IHR activities are a shared responsibility with OGDs and P/T governments. PHAC is the IHR National Focal Point (NFP) for Canada and acts as the single window for rapid communication between Canadian public health authorities, the WHO, the Pan-American Health Organization, and health authorities in other countries. The HPOC Watch Office serves as the operational arm of Canada's IHR NFP office by supporting 24/7 communications between Canada, the WHO and member states, as well as disseminating information with stakeholders.Footnote 11 Also within PHAC, the Office of International Affairs (OIA) leads the negotiations with other member states as part of the WHO process, while domestic implementation and guidance for negotiations resides with relevant HP and OGD programs, including ROEMB as the lead for Canada's NFP office. Despite some internal challenges, PHAC provided 100% of IHR-related communications to stakeholders within defined timelines for the last two fiscal years since this indicator was created (2022-23 and 2023-24).

Given the absence of dedicated governance tables at PHAC for EM related international issues, there are coordination challenges between both branches. As a result, key actions identified in internal documents included the need to define and distinguish ROEMB and OIA roles on EM-related international files, including how they work, and who leads what, as well as the need to clearly define governance and decision making on international files.

Collaboration with North American partners

Engagement between ROEMB and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) was formalized in 2018 with the establishment of a liaison program. As a result, collaboration has strengthened over the last five years with more frequent communication, including monthly calls between ROEMB and ASPR. There are two levels of regular liaison with ASPR, one is through the director or working level group and the second is through the HPOC and the ASPR's equivalent.